Abstract

The inflammatory response plays an important role in host defense and maintenance of homeostasis, while imbalances in these responses can also lead to pathologic disease processes. Emerging data show that RKIP interacts with multiple signaling molecules which may potentiate multiple functions during inflammatory processes. This chapter will review the interaction of RKIP with both the MAPK and NF-κB pathways in relation to chronic inflammatory diseases. In these settings, it can both inhibit inflammatory pathways as well contribute to pro-inflammatory signaling, often depending on the interactions with multiple proteins and perhaps lipids. The interactions of RKIP with proteins, phospholipids, fatty acids and their enzymes, thus, could play a substantial role in diseases like asthma and diabetes. Targeting interactions of RKP with these pathways could lead to novel approaches to treatment.

Keywords: 15-Lipoxygensae-1, MUC5AC, RKIP, NF-kB, Asthma

I. INTRODUCTION

The inflammatory response plays an important role in host defense and maintenance of homeostasis, while also contributing to disease development. Normally these responses are tightly controlled, often involving multiple regulatory checkpoints along their pathways. Imbalances in these responses can lead to pathologic disease processes. Emerging data show that RKIP [also known as phosphotidylethanolamine binding protein-1 (PEBP1)] can interact with multiple signaling molecules to serve as one of these inflammatory checkpoints, the discussion of which will be the focus of this chapter. For consistency, RKIP will be the term used to identify this protein throughout this chapter, although in many cases the original papers utilized the alternate term PEBP1.

II. INTERACTIONS OF RKIP WITH THE MITOGEN ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE (MAPK) AND THE NF-κB PATHWAY TO INHIBIT THE INFLAMMATORY PATHWAY (TABLE 1)

Table 1.

Molecules known to interact with RKIP under basal/unstimulated conditions

RKIP belongs to a class of proteins originally identified to specifically bind with the phospholipid, phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)1,2 and termed PEBPs, two of which are known to exist in humans (PEBP1/RKIP and PEBP4). Early on, PEBP-1 was shown to bind to and inhibit the function of Raf-1, leading to the term RKIP. As has been made clear in numerous other chapters, RKIP binds to Raf-1, one of the few known endogenous inhibitors of the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and inhibits Raf-1-mediated activation of the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) by preventing phosphorylation of Raf-1.3–5 Thus, under homeostatic/basal conditions, RKIP appears to have anti-inflammatory effects through inhibition of these ERK/MAPK pathways.

Like MAPK/ERK, the Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway is also considered to be one of the most important pro-inflammatory signaling pathways. Upon activation, prototypically in response to tumor-necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) stimulation, NF-κB functions as a dimeric transcription factor controlling many pro-inflammatory genes (Review).6 A study utilizing a COS-1 cell line and overexpression of FLAG-tagged RKIP and Hemaggluinin (HA)-tagged kinases, showed that RKIP co-immunoprecipitated with both inhibitors of κB kinase α and β (IKKα and IKKβ), upstream activating kinases of NF-κB, as well as NF-κB inducing kinase (NIK) and transforming growth factor-β activated kinase (TAK1).7 These results suggested that RKIP functions as an inhibitor of NF-kB signaling, a suggestion supported by results from co-transfection of an RKIP expression vector and NF-κB luciferase reporter assay in 293 cells. These experiments showed that transfection of RKIP reduced NF-κB activity in response to TNF-α and IL-1β.7 Thus, in addition to inhibition of MAPK, basal levels of RKIP could negatively regulate NF-κB through binding of upstream activators of NF-κB. Interestingly, RKIP appears to be induced with monocyte/macrophage differentiation and could impact basal responses to TNF-α signaling.7,8

Because of the clear importance of the NF-κB pathway in inflammatory processes, interactions of RKIP with NF-κB are likely to have an impact on NF-κB-associated inflammatory processes. In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), an NF-κB-associated chronic systemic inflammatory disease, over expression of RKIP in primary rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocyte (FLS) culture significantly decreased TNF-α-stimulated matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-1 and -3, IL-6 and -8, and FLS invasiveness. These effects are consistent with an enhanced ability of RKIP to inhibit NF-kB signaling which could then alter both inflammatory and remodeling effects in rheumatoid arthritis.9 Similarly, an interaction of RKIP with NF-κB has been suggested to occur in primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS), an autoimmune disorder characterized by an epithelial injury surrounded by dense lymphocytic infiltrates.10 Using the human salivary gland epithelial cells (SGEC) from pSS patients and a co-culture system with pSS lymphocytes, results from this study showed that up-regulation of RKIP decreased NF-kB activity. This up-regulation likely contributed to decreases in a group of inflammatory cytokines (e.g IL-1α/β, IL-13, TNF-α, IFN-γ, etc) and chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL6, CCL2, CCL13, etc). In contrast, RKIP silencing significantly activated NF-κB signaling and increased pro-inflammatory mediator expression and release. Intriguingly, RKIP protein expression in SGEC from pSS patients was reported to be significantly lower than that of healthy SGEC, further supporting a role for RKIP in the suppression of NF-κB activation (and overall disease outcomes) in pSS SGEC. To date, this is the only inflammatory disease reported with low RKIP levels.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is increasingly recognized as an inflammatory condition. Results from a rat DM model observed a decreased RKIP expression and increased NF-κB activation in DM renal tissues, again supporting an inhibitory role for RKIP in NF-kB mediated inflammatory responses. When the rats were treated with Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody which selectively depletes B lymphocytes, the expression of RKIP increased in renal tissues, in association with decreased NF-κB activation. Although no data presented in this study evaluated the direct interactions of RKIP with NF-κB, the negative correlation of RKIP expression with NF-κB activation observed in this DM model support an important role for RKIP in the inflammatory processes related to diabetic nephropathy.11 Detailed studies are needed to further identify the mechanism underlying how Rituximab with its anti-B-cell effects, induces RKIP expression. These results together suggest that RKIP modulation might be a therapeutic target for NF-κB-associated inflammatory diseases.

In addition to the studies which suggest RKIP inhibits NF-κB to inhibit inflammatory pathways, another study suggests RKIP may play a biphasic effect on NF-κB signaling since both gain-of-function (over-expression) and loss-of-function (down-regulation) of RKIP) appear to have the same effect on IκB phosphorylation.12 In this study, knockdown of RKIP by siRNA transfection in a 239mycIL1R cell line (human embryonic kidney cells line 293 over-expressing IL-1RI) significantly deceased IκB phosphorylation following IL-1β stimulation. To explain the potential mechanisms for this, it was proposed that RKIP may function as a scaffolding protein by interacting with upstream of NF-κB pathway modulators and kinases TRAF6 and TAK1 to facilitate assembly of the IKK complex leading to IκB phosphorylation and NF-κB activation.12 These complex interactions appear to be ligand dependent, as IL-1β stimulation was necessary for RKIP to associate with TRAF6 and TAK1. As a decrease in IκB phosphorylation should inhibit NF-κB activation and decrease associated gene expression, the results of decreased IκB phosphorylation in RKIP knockdown cells following IL-1β stimulation seems at odds with the observation that RKIP knockdown also increases NF-κB activation and associated gene expression.12 A negative regulation mechanism was proposed in this study to explain this biphasic effect of RKIP on NF-κB signal pathway. After IL-1β stimulation, RKIP interacts with TRAF6 and TAK1 to facilitate the assembly IKK complex and increases IκB phosphorylation and degradation. However, this subsequent degradation may also activate an auto-regulatory feedback loop and enhance IκB gene expression, which would then off-set the IκB degradation due to RKIP/TRAF6. This RKIP-mediated loss-gain of IκB function feedback loop supports an overall inhibitory role of RKIP in the NF-κB signal pathway.12 It is not clear, however, whether the auto-regulatory feedback loop is RKIP/TRAF6 interaction dependent. Thus, these results add additional complexities to the impact of RKIP on NF-κB activation and associated gene expression.

III. RKIP CONTRIBUTION TO PRO-INFLAMMATORY SIGNALING (TABLE 2)

Table 2.

Molecules interacting with RKIP under inflammatory stimuli

Under certain inflammatory conditions, including chronic pancreatitis13 and metabolic disorders,14 phosphorylation of RKIP occurs through protein kinase C (PKC), phosphatidyl inositol-3 kinase (PI3K) or other pathways. When induced by protein PKC, phosphorylation occurs at the Ser153 residue, inducing a conformational change in the ligand binding pocket. This contributes to the dissociation of RKIP from Raf-1 and leads to activation of ERK/MAPK pathways.15 When activated by pathogens or tissue damage through a variety of receptors including receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), integrins and ion channels,16 ERK induces multiple genes that regulate the inflammatory response. While ERK does not directly stimulate gene expression by itself, it modulates other signaling pathways including NF-κB, PI3K and interferon-regulatory factor (IRF) transcription factors. Thus, the MEK/ERK pathway is a recognized as a critical, typically pro-inflammatory pathway.17, 18

As mentioned previously, RKIP is one of the few endogenous inhibitors of the ERK pathway. However, upon phosphorylation of RKIP, RKIP dissociates from Raf-1 and subsequently serves as an activator of MEK/ERK. Phosphorlylation induced disassociation of Raf-1 from RKIP leads to a conformational change in RKIP, which allows its ligand binding pocket to bind with chemically distinct ligands, including phospholipids, particularly PE and AA,19 as well as certain proteins.20 It is not yet clear whether this ligand binding is independent to phosphorylation. However, the flexibility of RKIP’s binding pocket may contribute to its ability to tightly control MAPK dependent pathways, through balances/imbalances in phosphorylation and ligand binding.20, 21

Under activated/phosphorylated conditions, RKIP appears to release Raf-1 and activates ERK. Thus, under phosphorylated conditions, gene expression downstream of MEK/ERK is likely to be augmented, including mucin genes of relevance to asthma, such as MUC5AC.22,23 However, in addition to augmentation of MEK/ERK in response to release of Raf-1, phosphorylation of RKIP appears to change its conformation allowing it to interact with other proteins and lipids. In its phosphorylated state, RKIP binds several proteins, including GRK224 and 15-lipoxygenase-1 (15LO1).23 Interestingly, phosphorylation of RKIP has not yet been investigated in regards to its relationship with NF-κB components, with and without IL-1β/TNF-α stimulatory conditions.

The prototypical protein which binds to activated RKIP is G-protein coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2).24 GRK2 is an important protein involved in the desensitization of many G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), but particularly the β2 adrenergic receptor (AR) of critical importance in inflammatory diseases such asthma. When GRK2 is free and phosphorylated, it phosphorylates the β2AR leading to its inactivation and internalization. However, when GRK2 is bound to activated/phosphorylated RKIP, it promotes sustained activation of the β2AR, while the release of Raf-1 leads to sustained activation of ERK.4,25–27 Thus, β2AR activation and subsequent PKC activation can lead to serine-153 phosphorylation of RKIP and binding to GRK2. This binding promotes sustained β2AR signaling, which might promote prolonged smooth muscle relaxation in the airways and blood vessels, enhanced ciliary beating to clear pathogens and promote mucin production and secrection.28, 29 However, repeated β2 stimulation leads to loss of GRK2/RKIP binding, GRK2 phosphorylation and β2AR desensitization, perhaps through a negative feedback loop which decreases GRK2/RKIP associations.20 Thus, this RKIP/GRK2 binding is likely to, be self-limited in the presence of prolonged β2AR stimulation. In any case, this GRK2/RKIP activation/inhibition axis is likely to have implications for asthma and other diseases treated with βAR agonists such as isoproterenol and albuterol.

Results from a T cell–dependent mouse model of Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) also support a pro-inflammatory role of RKIP. SIRS results from the general release of large quantities of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, TNF-α and interferon-γ (IFN-γ).30 This cytokine storm can lead to an overwhelming clinical collapse. In this model, RKIP contributed to exaggerated production of IFN-γ from stimulated splenocytes, with suggestion that RKIP expression actually drives IFN-γ production.30 In further support of this, the IFN-γ response in SIRS was significantly diminished using a small molecule inhibitor of RKIP (locostatin) to block RKIP in wild-type splenocytes. Locostatin alkylates a conserved histidine residue (His86) within the RKIP ligand-binding pocket,31 preventing RKIP from binding to its ligands and inhibiting RKIP functions. The inhibitory effect of locostatin on RKIP associated with a decrease in IFN-γ suggested that RKIP binding pocket inhibitors may be therapeutic targets in certain diseases.30 However, much remains to be understood regarding the mechanism for these effects, including the impact of locostatin on the NF-κB and ERK/MAPK pathways.

IV. INTERACTION OF RKIP WITH PHOSPHOLIPIDS, FATTY ACIDS AND THEIR ENZYMES: IMPLICATIONS IN ASTHMA AND OTHER INFLAMMATORY DISEASES

15LO1 belongs to the lipoxygenase family of enzymes that oxidizes unsaturated fatty acids, such as arachidonic acid (AA), at the 15 position to generate active hydroperoxy and epoxy metabolites. 15LO1 is expressed by macrophages, eosinophils and epithelial cells. 15LO1 and its eicosanoid product, 15 hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (15s-HETE) are increased in asthma in relation to eosinophilic inflammation and Type-2 (IL-4/-13) immune processes.32–35 In fact, 15LO1 is recognized as one of the genes most strongly induced by IL-13 which contributes to the regulation of MUC5AC expression in human airway epithelial cells,22 and substantiated by studies of 12/15 LO1 (−/−) mice model.36, 37

Unlike other eicosanoid generating enzymes, 15LO1 binds directly to phospholipids [phosphatidylinositol (PIs), and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)], stimulating enzyme activity to generate 15-HETEs and 13-HODEs.38 Exogenous 15HETE was also shown to incorporate into cellular phospholipids in epithelial cells.39 A previous study in monocytes showed that endogenously generated 15-HETEs directly conjugate with intracellular PE (15HETE-PE).40 In that study, human peripheral blood monocytes were stimulated with IL-4 and then activated with calcium Ionophore A23187. Using HPLC/MS, 15HETE-PE was the predominant 15LO1 product as compared to free 15HETE. This suggested that PE-esterified HETEs may contribute to 15LO1 signaling in inflammatory diseases such as asthma which appear to have a strong Type-2 (IL-4/-13) background.

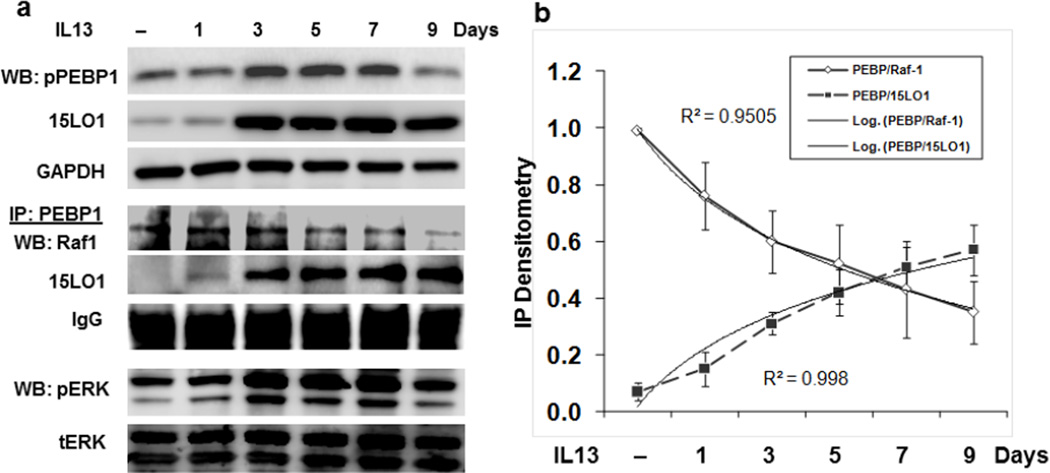

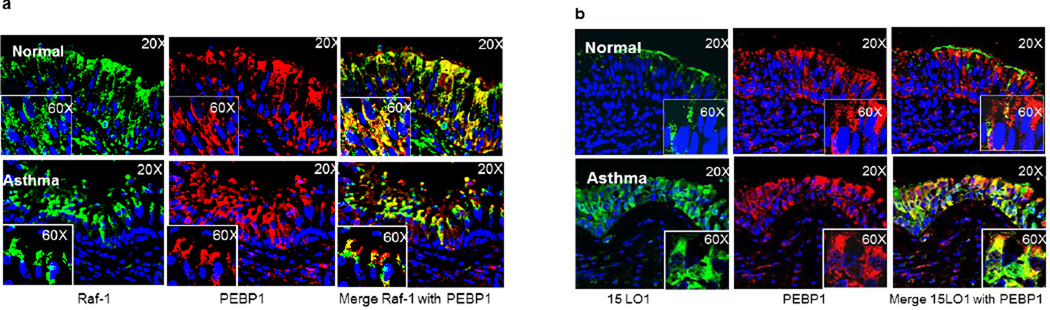

Similarly, a recent study of cultured human airway epithelial cells supported the production of esterified 15HETE-PE. In fact, in cultured airway epithelial cells stimulated with IL-13, 15HETE almost exclusively esterified to PE and was retained intracellularly.22 In addition, there was movement of 15LO1 to the cytoplasmic membrane in response to IL-13 where it could participate in cell signaling pathways. Finally, the results showed that IL-13 increased ERK activation, which decreased following siRNA knockdown of 15LO1. These findings led to the hypothesis that 15LO1, likely in conjunction with its product 15-HETE-PE, might contribute to ERK activation through its interactions with RKIP.23 To evaluate this, airway epithelial cells were treated with IL-13 to induce 15LO1/15 HETE-PE. IL-13 also led to phosphorylation of RKIP. Additionally, in a time dependent manner, in the face of increasing concentrations of 15LO1, the 15LO1 binding to RKIP increased concurrent with a reduction in Raf-1 binding. This increase in 15LO1 binding to RKIP was paralleled by increasing activation of ERK (Figure 1). While 15LO1 binding to RKIP initially was associated with phosphorylation of RKIP, prolonged dissociation of Raf-1 from RKIP and enhanced binding to 15LO1 occurred without further increases (and even decreases in) in RKIP phosphorylation. This may suggest that 15 LO1 (and perhaps its product 15 HETE-PE) induced a stable conformational change in RKIP which is self-perpetuating. This relationship is reversed by 15LO1 siRNA knockdown, confirming that IL-13 induced 15LO1 competitively binds to RKIP, releases Raf-1 and activates ERK. Increased binding of 15LO1 with RKIP was also observed in endobronchial tissue from asthmatics as compared to normal subject control (Figure 2). At least in the setting of Type-2 stimulated airway epithelial cells, as is seen in asthma, this binding of 15LO1 to RKIP appears to be critical to activation of ERK and induction of MUC5AC expression, and perhaps other signal pathways as well.

Figure 1. IL-13 induced-15LO1 amplifies MEK/ERK pathways through interaction with PEBP1/Raf-1.

ALI cultured primary human bronchial epithelial cells were stimulated with IL-13 for different time period. Total protein was harvested for IP/Western Blot. (a) IL-13 stimulation induced-15LO1 interacts with PEBP1/Raf-1 to activate ERK. (b) Regression analysis of the IP densitometry data demonstrates the increased PEBP1 binding to 15LO1 and the decreased Raf-1 binding over time.

Figure 2.

Confocal images of endobronchial tissue demonstrate that 15LO1 competes with Raf-1 to bind with PEBP1 in asthmatic tissue. (a) Markedly less co-localization of Raf-1 to PEBP1 in severe asthmatic as compared to normal control tissue. (b) High expression levels and colocalization of 15LO1 with PEBP1 in severe asthmatic as compared to normal control tissue.

The 15LO1 product, 15HETE-PE also appears to enhance dissociation of Raf-1 from RKIP.23 Although the mechanism of this interaction needs to be further defined, the interactions of 15HETE-PE with RKIP observed in human airway epithelial cells are consistent with a previous study which showed phospholipid binding in the RKIP binding pocket inhibited both Raf-1 binding to RKIP and its phosphorylation.20 Thus, it is conceivable that 15HETE-PE represents a naturally occurring PE-containing phospholipid capable of displacing Raf-1 from RKIP. Since the binding pocket of RKIP has been reported to bind to chemically distinct ligands, including phospholipids, proteins and lipoproteins,20 this binding pocket is the most likely region where RKIP could interact with both 15LO1 protein and its phospholipid product 15HETE-PE. Like 15LO1, RKIP is a membrane-associated protein which also likely enhances its regulation of signaling activities.41 Whether RKIP binds directly with 15HETE-PE or arachidonic acid, or just positions them close to 15LO1 is not yet clear. It is conceivable that, like its binding with TAK1 and TRAF6, RKIP serves as a scaffolding protein, enhancing 15 LO1 metabolic activity.42–44

Beside its high expression level in asthma, 15LO1 has been implicated in mediating the pathogenic lipid peroxidation associated with inflammatory vascular diseases including atherosclerosis, diabetes and hypertension (reviews45–48). It may also be involved in the oxidative modification of low-density lipoproteins and foam cell formation in atherosclerotic plaques. Interestingly, as noted above, the conjugated 15LO1 product, 15HETE-PE, has also been detected in monocytes and,40 macrophages.49 Although the direct evidence is lacking to indicate that 15LO1 and/or 15HETE-PE in these cell types interact with RKIP in a similar way to that observed in human epithelial cells, interactions with RKIP in a variety of inflammatory cells and diseases is clearly plausible.

V. MODIFICATION OF INFLAMMATORY DISEASE RESPONSES THROUGH TARGETING RKIP BINDING

Dysregulation of RKIP has been suggested to contribute to many human diseases (review4). However, its role in modulating inflammation in more traditional inflammatory processes remains less clear. The interactions of RKIP with Raf-1/ERK, NF-κB and inflammatory fatty acids/phospholipids strongly support a role in inflammatory processes. It is also not yet clear whether other proteins/lipids will bind with RKIP either under phosphorylated conditions or, in the case of some lipids, bind without phosphorylation. But given the long list of interactions already identified, this would appear to be likely. These interactions could then change the “inhibitory” nature of RKIP towards a pro-inflammatory molecule. Given the important role of RKIP function in human diseases, strategies to modulate its function are logical but complex, as RKIP appears to have both anti- and pro-inflammatory properties depending on its phosphorylation/conformation as well as stimulation. As these modifications appear to be highly regulated, ligand-dependent and variable in different inflammatory diseases, approaches modulating RKIP function will need to be condition dependent, as merely removing RKIP may have adverse effects by activating ERK and NF-κB pathways. However, a better understanding of the mechanism for the interaction of 15LO1 (and/or 15HETE-PE) with RKIP could lead to novel anti-inflammatory approaches in asthma, diabetes and autoimmune diseases, as well as inflammatory processes associated with cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH AI-40600-15(SEW); CTSI UL1-RR024153 (SEW), American Heart Association grant 0825556D (JZ), American Lung Association RG-231468-N (JZ).

ABBREVIATIONS

- 15LO1

15-Lipoxygensae-1

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- NF-κB

Nuclear Factor-κB

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- PEBP1

phosphotidylethanolamine binding protein

- RKIP

Raf kinase inhibitor protein

References

- 1.Banfield MJ, Barker JJ, Perry AC, Brady RL. Function from structure? The crystal structure of human phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein suggests a role in membrane signal transduction. Structure. 1998;6(10):1245–1254. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serre L, Vallee B, Bureaud N, Schoentgen F, Zelwer C. Crystal structure of the phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein from bovine brain: a novel structural class of phospholipid-binding proteins. Structure. 1998;6(10):1255–1265. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeung K, Seitz T, Li S, Janosch P, McFerran B, Kaiser C. Suppression of Raf-1 kinase activity and MAP kinase signalling by RKIP. Nature. 1999;401(6749):173–177. doi: 10.1038/43686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller ET, Fu Z, Brennan M. The role of Raf kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP) in health and disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68(6):1049–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trakul N, Rosner MR. Modulation of the MAP kinase signaling cascade by Raf kinase inhibitory protein. Cell Research. 2005;15(1):19–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Z, Andersson R. NF-kappaB activation and inhibition: a review. Shock. 2002;18(2):99–106. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeung KC, Rose DW, Dhillon AS, Yaros D, Gustafsson M, Chatterjee D. Raf kinase inhibitor protein interacts with NF-kappaB-inducing kinase and TAK1 and inhibits NF-kappaB activation. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2001;21(21):7207–7217. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7207-7217.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuierer MM, Heilmeier U, Boettcher A, Ugocsai P, Bosserhoff AK, Schmitz G. Induction of Raf kinase inhibitor protein contributes to macrophage differentiation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;342(4):1083–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn JK, Hwang JW, Bae EK, Lee J, Jeon CH, Koh EM. The role of Raf kinase inhibitor protein in rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocytes invasiveness and cytokine and matrix metalloproteinase expression. Inflammation. 2012;35(2):474–483. doi: 10.1007/s10753-011-9336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sisto M, Lisi S, D'Amore M, Lofrumento DD. Rituximab-mediated Raf kinase inhibitor protein induction modulates NF-kappaB in Sjogren's syndrome. Immunology. 2014;143:42–51. doi: 10.1111/imm.12288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li L, Zhao YW, Zeng JS, Fan F, Wang X, Zhou Y. Rituximab regulates the expression of the Raf kinase inhibitor protein via NF-kappaB in renal tissue of rats with diabetic nephropathy. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2013;12(3):2973–2981. doi: 10.4238/2013.August.16.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang H, Park S, Sun SC, Trumbly R, Ren G, Tsung E. RKIP inhibits NF-kappaB in cancer cells by regulating upstream signaling components of the IkappaB kinase complex. FEBS Letters. 2010;584(4):662–668. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SO, Ives KL, Wang X, Davey RA, Chao C, Hellmich MR. Raf-1 kinase inhibitory protein (RKIP) mediates ethanol-induced sensitization of secretagogue signaling in pancreatic acinar cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287(40):33377–33388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.367656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macrae K, Stretton C, Lipina C, Blachnio-Zabielska A, Baranowski M, Gorski J. Defining the role of DAG, mitochondrial function, and lipid deposition in palmitate-induced proinflammatory signaling and its counter-modulation by palmitoleate. Journal of Lipid Research. 2013;54(9):2366–2378. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M036996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corbit KC, Trakul N, Eves EM, Diaz B, Marshall M, Rosner MR. Activation of Raf-1 signaling by protein kinase C through a mechanism involving Raf kinase inhibitory protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(15):13061–13038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocrine Reviews. 2001;22(2):153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arthur JS, Ley SC. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in innate immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2013;13(9):679–692. doi: 10.1038/nri3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown J, Wang H, Hajishengallis GN, Martin M. TLR-signaling networks: an integration of adaptor molecules, kinases, and cross-talk. Journal of Dental Research. 2011;90(4):417–427. doi: 10.1177/0022034510381264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brock TG. Capturing proteins that bind polyunsaturated fatty acids: demonstration using arachidonic acid and eicosanoids. Lipids. 2008;43(2):161–169. doi: 10.1007/s11745-007-3136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Granovsky AE, Clark MC, McElheny D, Heil G, Hong J, Liu X. Raf kinase inhibitory protein function is regulated via a flexible pocket and novel phosphorylation-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(5):1306–1320. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01271-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shemon AN, Heil GL, Granovsky AE, Clark MM, McElheny D, Chimon A. Characterization of the Raf kinase inhibitory protein (RKIP) binding pocket: NMR-based screening identifies small-molecule ligands. PloS One. 2010;5(5):e10479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao J, Maskrey B, Balzar S, Chibana K, Mustovich A, Hu H, Wenzel SE. Interleukin-13-induced MUC5AC is regulated by 15-lipoxygenase 1 pathway in human bronchial epithelial cells. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2009;179(9):782–790. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200811-1744OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao J, O'Donnell VB, Balzar S, St Croix CM, Trudeau JB, Wenzel SE. 15-Lipoxygenase 1 interacts with phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein to regulate MAPK signaling in human airway epithelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(34):14246–14251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018075108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorenz K, Lohse MJ, Quitterer U. Protein kinase C switches the Raf kinase inhibitor from Raf-1 to GRK-2. Nature. 2003;426(6966):574–579. doi: 10.1038/nature02158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer CN, Lipworth BJ, Lee S, Ismail T, Macgregor DF, Mukhopadhyay S. Arginine-16 beta2 adrenoceptor genotype predisposes to exacerbations in young asthmatics taking regular salmeterol. Thorax. 2006;61(11):940–944. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.059386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weir TD, Mallek N, Sandford AJ, Bai TR, Awadh N, Fitzgerald JM. beta2-Adrenergic receptor haplotypes in mild, moderate and fatal/near fatal asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(3):787–791. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9801035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reihsaus E, Innis M, MacIntyre N, Liggett SB. Mutations in the gene encoding for the beta 2-adrenergic receptor in normal and asthmatic subjects. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1993;8(3):334–339. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/8.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker JK, DeFea KA. Role for beta-arrestin in mediating paradoxical betaAR and PAR signaling in asthma. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2014;16C:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nichols HL, Saffeddine M, Theriot BS, Hegde A, Polley D, El-Mays T. beta-Arrestin-2 mediates the proinflammatory effects of proteinase-activated receptor-2 in the airway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(41):16660–16665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208881109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright KT, Vella AT. RKIP contributes to IFN-gamma synthesis by CD8+ T cells after serial TCR triggering in systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J Immunol. 2013;191(2):708–716. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beshir AB, Argueta CE, Menikarachchi LC, Gascon JA, Fenteany G. Locostatin Disrupts Association of Raf Kinase Inhibitor Protein With Binding Proteins by Modifying a Conserved Histidine Residue in the Ligand-Binding Pocket. Forum on Immunopathological Diseases and Therapeutics. 2011;2(1):47–58. doi: 10.1615/forumimmundisther.v2.i1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu HW, Balzar S, Westcott JY, Trudeau JB, Sun Y, Conrad DJ. Expression and activation of 15-lipoxygenase pathway in severe asthma: relationship to eosinophilic phenotype and collagen deposition. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32(11):1558–1565. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradding P, Redington AE, Djukanovic R, Conrad DJ, Holgate ST. 15-lipoxygenase immunoreactivity in normal and in asthmatic airways. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1995;151(4):1201–1204. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.4.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim KS, Chun HS, Yoon JH, Lee JG, Lee JH, Yoo JB. Expression of 15-lipoxygenase-1 in human nasal epithelium: its implication in mucociliary differentiation. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, and Essential Fatty Acids. 2005;73(2):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Profita M, Sala A, Riccobono L, Paterno A, Mirabella A, Bonanno A. 15-Lipoxygenase expression and 15(S)-hydroxyeicoisatetraenoic acid release and reincorporation in induced sputum of asthmatic subjects. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2000;105(4):711–716. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.105122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andersson CK, Claesson HE, Rydell-Tormanen K, Swedmark S, Hallgren A, Erjefalt JS. Mice lacking 12/15-lipoxygenase have attenuated airway allergic inflammation and remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39(6):648–656. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0443OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hajek AR, Lindley AR, Favoreto S, Jr, Carter R, Schleimer RP, Kuperman DA. 12/15-Lipoxygenase deficiency protects mice from allergic airways inflammation and increases secretory IgA levels. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(3):633–639. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dobrian AD, Lieb DC, Cole BK, Taylor-Fishwick DA, Chakrabarti SK, Nadler JL. Functional and pathological roles of the 12- and 15-lipoxygenases. Progress in Lipid Research. 2011;50:115–131. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Profita M, Vignola AM, Sala A, Mirabella A, Siena L, Pace E. Interleukin-4 enhances 15-lipoxygenase activity and incorporation of 15(S)-HETE into cellular phospholipids in cultured pulmonary epithelial cells. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 1999;20(1):61–68. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.1.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maskrey BH, Bermudez-Fajardo A, Morgan AH, Stewart-Jones E, Dioszeghy V, Taylor GW. Activated platelets and monocytes generate four hydroxyphosphatidylethanolamines via lipoxygenase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(28):20151–20163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Overbye A, Fengsrud M, Seglen PO. Proteomic analysis of membrane-associated proteins from rat liver autophagosomes. Autophagy. 2007;3(4):300–322. doi: 10.4161/auto.3910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balboa MA, Shirai Y, Gaietta G, Ellisman MH, Balsinde J, Dennis EA. Localization of group V phospholipase A2 in caveolin-enriched granules in activated P388D1 macrophage-like cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(48):48059–48065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mounier CM, Ghomashchi F, Lindsay MR, James S, Singer AG, Parton RG. Arachidonic acid release from mammalian cells transfected with human groups IIA and X secreted phospholipase A2 occurs predominantly during the secretory process and with the involvement of cytosolic phospholipase A2-α. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(24):25024–25038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Satake Y, Diaz BL, Balestrieri B, Lam BK, Kanaoka Y, Grusby MJ. Role of group V phospholipase A2 in zymosan-induced eicosanoid generation and vascular permeability revealed by targeted gene disruption. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(16):16488–16494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313748200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Funk CD, Cyrus T. 12/15-lipoxygenase, oxidative modification of LDL and atherogenesis. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2001;11(3–4):116–124. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hersberger M. Potential role of the lipoxygenase derived lipid mediators in atherosclerosis: leukotrienes, lipoxins and resolvins. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2010;48(8):1063–1073. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2010.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aldrovandi M, O'Donnell VB. Oxidized PLs and vascular inflammation. Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 2013;15(5):323. doi: 10.1007/s11883-013-0323-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schiffrin EL. T lymphocytes: a role in hypertension? Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 2010;19(2):181–186. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283360a2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morgan AH, Dioszeghy V, Maskrey BH, Thomas CP, Clark SR, Mathie SA. Phosphatidylethanolamine-esterified eicosanoids in the mouse: tissue localization and inflammation-dependent formation in Th-2 disease. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(32):21185–21191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]