Abstract

Purpose

Patients with cancer experience acute and chronic symptoms caused by their underlying disease or by the treatment. While numerous studies have examined the impact of various treatments on symptoms experienced by cancer patients, there are inconsistencies regarding the symptoms measured and reported in treatment trials. This article presents a systematic review of the research literature of the prevalence and severity of symptoms in patients undergoing cancer treatment.

Methods

A systematic search for studies of persons receiving active cancer treatment was performed with the search terms of “multiple symptoms” and “cancer” for studies involving patients over the age of 18 years and published in English during the years 2001 to 2011. Search outputs were reviewed independently by seven authors, resulting in the synthesis of 21 studies meeting criteria for generation of an Evidence Table reporting symptom prevalence and severity ratings.

Results

Data were extracted from 21 multi-national studies to develop a pooled sample of 4067 cancer patients in whom the prevalence and severity of individual symptoms was reported. In total, the pooled sample across the 21 studies was comprised of 62% female, with a mean age of 58 years (range: 18 to 97 years). A majority (62%) of these studies assessed symptoms in homogeneous samples with respect to tumor site (predominantly breast and lung cancer), while 38% of the included studies utilized samples with mixed diagnoses and treatment regimens. Eighteen instruments and structured interviews were including those measuring single symptoms, multi-symptom inventories, and single symptom items drawn from HRQOL or health status measures. The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) was the most commonly used instrument in the studies analyzed (n=9 studies; 43%), while the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Subscale (HADS-D), Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form-36 (SF-36), and Symptom Distress Scale (SDS) were each employed in two studies. Forty-seven symptoms were identified across the 21 studies which were then categorized into 17 logical groupings. Symptom prevalence and severity were calculated across the entire cohort and also based upon sample sizes in which the symptoms were measured providing the ability to rank symptoms.

Conclusions

Symptoms are prevalent and severe among patients with cancer. Therefore, any clinical study seeking to evaluate the impact of treatment on patients should consider including measurement of symptoms. This study demonstrates that a discrete set of symptoms is common across cancer types. This set may serve as the basis for defining a “core” set of symptoms to be recommended for elicitation across cancer clinical trials, particularly among patients with advanced disease.

Keywords: Cancer, symptoms, systematic review

Introduction

Patients with cancer experience acute and chronic symptoms caused both by their underlying disease and by the often toxic treatments employed in oncology care.[1,2] Clinical investigators, regulators, and healthcare providers often focus on the prevention or cure of illness, whereas relief of symptoms is a paramount goal for patients. [3,4] Symptoms are a common reason healthcare is sought and an impetus for testing to definitively diagnose an illness or injury. Once treatment is implemented, symptomatic treatment toxicities frequently develop. [5]

While numerous studies have examined the impact of various treatments and medications on symptoms in patients receiving cancer treatment, a limitation in comparing these outcomes is the lack of a common or “core” set of patient-reported symptoms, consistently measured across studies. For example, one study may report an improvement in nausea with a specified treatment, another study may report worsening fatigue, leaving the clinician and patient comparing treatment efficacies and weighing side effects based upon disparate outcomes.

These differences in symptom outcomes between studies to some extent can be attributed to the use of varying symptom assessment questionnaires and strategies. While there is value to focusing on specific symptoms in particular clinical contexts (e.g., pain in patients with metastatic prostate cancer to bone), there is also value in administration of a common set of symptoms both in order to characterize the broader impact of disease and treatment on the patient experience, and to enable cross-trial comparisons and aggregation of data. Therefore, in 2011, the National Cancer Institute sponsored a scientific meeting to identify a standard core set of patient-reported symptoms to be recommended across cancer clinical trials as well as existing questionnaires that are appropriate for assessing these symptoms. As a component of this initiative, a multidisciplinary team conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify studies that measure the prevalence and severity of symptoms in patients undergoing cancer treatment.

Search Methods

A systematic electronic search of PubMed was performed with the search terms of “multiple symptoms” and “cancer” (Figure 1). The search was limited to adults over the age of 18 years, English language articles, and the years 2001 to 2011. Search outputs including the abstract were reviewed independently by seven authors, and full-text of papers deemed to be potentially relevant based on a priori criteria (i.e., containing evidence characterizing symptoms in patients being treated for cancer) for inclusion were examined. Hand searches of papers in reference lists were also performed. Studies were included if they evaluated multiple symptoms in persons receiving active cancer treatment regardless of cancer site, stage, treatment, or geographic location. The initial search retrieved 55 publications of which 19 were excluded as case studies,[6-8] studies of single symptoms,[9-12] symptoms at the end of life,[13,] presenting symptoms at the time of cancer diagnosis,[15,16] or were otherwise not research reports focused of multiple symptoms in persons with cancer.[17-24]

Figure 1. Search Methodology.

In 2009, Esther Kim et al[25] published a literature synthesis of cancer symptomotology in 18 studies. This paper and four additional literature reviews[26-29] identified in our systematic search were excluded from this analysis. Instead, the findings by Esther Kim et al. (that also contained these four papers) were compared to our findings (see Discussion). Unlike the Esther Kim et. al. synthesis which only included studies that used the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI), Memorial Symptom Assessment Scales (MSAS), or the Symptom Distress Scale (SDS), this present analysis intentionally did not limit to any specific assessment instrument so that a wide array of symptoms could be collated and analyzed across a broader range of studies.

Nine publications that failed to report symptom statistics[30-38] and one publication that was a secondary study of a sample already included in this analysis[39] were excluded, resulting in 21 studies included in this analysis.[40-60] Potentially relevant data were abstracted for the review including disease/treatment, sample, instrument used to measure symptoms, and symptom prevalence and severity. Where information about prevalence and severity was not presented, the authors were contacted by e-mail to obtain the necessary detail. Data were managed using Excel.

Analysis and Synthesis Methodology

Table 1 provides a summary of the 21 studies that evaluated multiple symptoms in adult oncology patients receiving active treatment. Twelve of these studies used a cross-sectional design and 9 employed a longitudinal approach that included randomized clinical trials, a cross-over design, or structured interviews. The length of follow-up in the longitudinal studies ranged from 7 days to 18 months, with assessment time points typically concurrent with important milestones such as treatment cycles or return to the home community following allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT).

Table 1. Evidence table.

| Evidence Source/Citation | Sample Characteristics (n, age, stage, treatment type, phase of care, special population) | Outcome Measure(s) of Symptoms, Functioning and/or HRQL | Study Design/Analytic Approach | Symptoms and Symptom Dimensions (provide %s or #s as they relate to prevalence, severity, duration, and/or interference) | Comments and Caveats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson (2007) | 100 patients during the acute phase of autologous PBSC transplantation with multiple myeloma or non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI-BMT) and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) were completed at baseline, 3-4 days into conditioning, day of transplant, day of nadir, and 30days post transplant. The Profile of Mood States (POMS) and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT) at BL and 30 days. | Longitudinal, descriptive | The time point associated with the most reported disturbances was Nadir: The top five symptoms at each time point rated by patients as moderate to severe were: BL 29% fatigue, 21% pain, 17% distress, 14% weakness, 13% sadness; Conditioning: 34% disturbed sleep, 22% fatigue, 22% loss appetite, 14% nausea, 13% weakness.; Transplant:34% loss appetite, 32% fatigue, 26% disturbed sleep, 25% nausea, 23% weakness. Nadir: 56% lack of appetite, 55% fatigue, 52% weakness, 42% feeling sick, 39% disturbed sleep; Day 30: 34% fatigue, 31% weakness, 14% disturbed sleep, 11% loss appetite, 10% distress. | Cancer diagnosis was a significant predictor of changes in symptoms over time. The patterns of fatigue, pain, sleep disturbance and lack of appetite were significantly different for patients with multiple myeloma as compared with patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. |

| Bevans, Mitchell, Marden (2008) | 76 adults undergoing allogenic HSCT from a single institution. Mean age of 40 years (SD 13.5 years). 67% of the sample was male; 30% of the sample was Hispanic; two thirds were undergoing transplant for acute or chronic leukemia, lymphoma or multiple myeloma. 66% were in a complete remission at the time of transplant, while 34% had progressive disease. | Symptom Distress Scale (SDS) | Longitudinal study with data about the symptom experience collected pre-transplant, day 0 (after HSCT conditioning), and days 30 and 100 post-transplant | The most prevalent symptoms at baseline were fatigue and worry (both 68%), at day 0, the most prevalent symptom was appetite change (88%), and fatigue was most prevalent at days 30 (90%) and 100 (81%). Symptoms that were severely distressing including worry (16% severely distress at baseline), insomnia (32% severely distressed at day 0), appetite change 22% severely distressed at day 30) and fatigue (11% severely distressed at day 100). The SDS was highest at day 0 (mean 26.6 SD 7.6), when the highest number of symptoms were reported. Symptoms formed clusters comprised of fatigue, appearance change and worry at baseline, and fatigue, insomnia, and bowel changes at days 0 and 30. Examining the symptom experience over time, it is apparent that HSCT patients tend to present for transplantation with low symptom distress, and experience multiple symptoms and high symptom distress after conditioning. | Though not consistently the most prevalent or distressing, GI complications, including bowel changes, nausea, and appetite limitations were noted across the treatment trajectory. |

| Chen ML, Chang HK (2004) | 121 patients with breast (40%), head and neck (33%), or esophageal cancer (27%) that were hospitalized in Northern Taiwan for chemotherapy (76%), symptom management (20%) and follow-up or surgery (4.1%). Male=55%. Mean Age=52.19 (SD 10.44) Range=26-81. Cancer stage= II (15 %), III (17%), IV (33%), missing (36%). | Patient Disease Symptom/Sign Assessment Scale (PDSA), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Subscale (HADS-D) | Cross-sectional, descriptive | Insomnia was the most prevalent symptom (67%), followed by pain (62%), anorexia (47%), fatigue/weakness (40%), nausea/vomiting (24%), wound/pressure sore (17%), dyspnea (14%), edema (8.3%), elimination problems (2.5%), and change in consciousness (0%). The average number of symptoms for total sample was 2.83 (median 3.0, range: 0/7). 55% reported 3 or more. 25% were classified as depressed (HADS-D cutoff of 11). The average number of symptoms observed total sample was 3.77 (median 3.5), depressed patients had average number of 3.77 (median=3.5) and non-depressed had 2.52 (median/2.0). Depressed patients showed a significantly higher occurrence rate than that of non-depressed patients in insomnia, pain anorexia fatigue, wound/pressure sore. Patients simultaneously experiencing insomnia, pain, anorexia, and fatigue had a higher risk of depression (odds ratio 5.03) | Using HADS-D to measure depression decreases the likelihood of confounding the assessment of depression with physical symptoms caused by cancer and its treatment since HADS-D does not use physical symptoms to measure depression. |

| Chen (2007) | 329 multi-disease site pts. Study from Taiwan 29% breast; 25% GI; 76% local disease without mets; time since dx 1-311mos with median of 14 mos; 53% had chemo; 73% had RT | MDASI-Taiwanese- 13 common ca related symptoms measured on scale 1-10 assessed in primary study but only 9 symptoms used in this secondary CFA analysis based on previous EFA (Chen & Tseng 2006) | Secondary analysis of Cross sectional study; Confirmatory factor analysis | mean # of symptoms per pt = 6.6 (range 0-13); prevalence 72% dry mouth; 70% fatigue 63% sleep disturbance 3 clusters: sickness including pain, fatigue, disturbed sleep & drowsiness; GI including N&V & lack of appetite; Emotional including distress & sadness | |

| Ferreira (2008) | 115 outpatients with cancer, who had not received cancer treatment in the last 30 days who reported at least 2 symptoms. Female=61%, Mean age= 57.2(SD 13.5). Type of cancer-Breast=38.9%, Lung=23.9%, Prostate=10.6%, Genitourinary=13.3%, Head and neck=7.1%, Gastrointestinal=5.3%, and other=0.9%. Presence of metastases=67.6%. Previous treatment-Chemotherapy=51.4%, Radiation therapy=55.0%, Hormonal therapy=19.8% and Surgery=66.7%. Country of study=Brazil | Karnofsky Performance Status scale (KPS),Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30). | Cross-sectional, descriptive study | Prevalence and mean of symptoms as follows: pain 100%, 7.36; fatigue 87%, 41.50; Insomnia 73%, 57.39; constipation 51%, 36.52; lack of appetite 50%, 37.97; dyspnea 44%, 24.19; depression 44%, 14.43; nausea and vomiting 28%, 11.65; diarrhea 11%, 5.01. Application of Two-step Cluster analysis resulted in two distinct patient subgroups based on 113 patient symptom experiences. One group had multiple and severe symptom subgroup and another had less symptoms and with lower severity. (Pain scale 0-10, depression 0-63, other symptoms 0-100). | |

| Gift (2004) | n = 220, with newly diagnosed lung; sample from 24 community oncology sites in Michigan; 91% white; 65-89 years (mean 72); Stages 0-II - 38%, stages III - IV -62%; Treatment - Surgery -42%, Chem - 43%, Rad -63% | Given (lead author) Physical Symptom Experience tool (37 symptoms; occurrence, severity, interference). | secondary data analysis of NIH panel study; data collected at diagnosis | Most Frequent(%): Fatigue 79; Up at night urinate 68; cough 65; pain 60; diff breathing 58; weakness 57; app loss 50; dry mouth 49; wt loss 45; altered taste 35; nausea 34; lack of sex interest 31; diff swallow 30; dizziness 23 diff concentrating 20; problems coordination 16 vomiting 15 hot flashes 7 arms swelling 2; Most Severe (mean, scale 1-3): Arm swell 2.33, lack sex interest 2.07, vomit 2; hot flash 1.94; trouble sleep 1.89; fatigue 1.84; pain 1.84; diff breath 1.82; diff swallow 1.82; alter taste 1.76; app loss 1.74; weakness 1.69; wt loss 1.67; problems coordination 1.61; dry mouth 1.56; cough 1.54; diff concentrating 1.44; dizziness 1.43; up at night urinate 1.39 | |

| Harding (2007) | 31 adult Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC) patients: Average age 55 years; 55% of patients were male, 74% had attended college, and 97% were Caucasian. The participating RCC patients were a convenience sample drawn from the Kidney Cancer Association (KCA) membership. | A brief, self-administered RCC Symptom Index was created that captures the relevant signs and symptoms of both localized and metastatic patients. Pending additional content validation, the Index can be used to assess the signs and symptoms of RCC and the clinical benefit resulting from RCC treatment. | National cross-sectional study was conducted to define patient-reported RCC symptomology. | The five most frequent symptoms among localized stage patients (n = 14) were irritability (79%), pain (71%), fatigue (71%), worry (71%), and sleep disturbance (64%). Among metastatic patients (n = 17), the five most frequent symptoms were fatigue (82%), weakness (65%), worry (65%), shortness of breath (53%), and irritability (53%). More than 50% of localized and metastatic-stage patients reported pain, weakness, fatigue, sleep disturbance, urinary frequency, worry, and mood disorders as being moderately to highly relevant. | The RCC Symptom Index was developed through a structured, iterative process that drew upon several information sources to identify the appropriate signs and symptoms. A broad range of physiological and psychological disease manifestations were identified and found relevant by a national, US cohort of RCC patients who were undoubtedly treated at different cancer centers. |

| Hayes (2010) | N=287, Australian women age 74 or younger (mean 54), early stage, all post surgery (PS) by 4 mo+, 87% had one or more LNs dissected w median of 12 LNs examined | PRO: FACT-B+4 (arm subscale), Disability of Arm, Shoulder, Hand (DASH) collected at 6 mo and q3 mo ×4. Objective measures: ROM, Exercise protocol, Bio-impedance Spectroscopy (BIS) to measure LE | Descriptive study, prospective, longitudinal, population-based sample through cancer registry in Queensland, Australia | Numbness (19-29%) & swelling(13-23%) most common symptoms. Multiple symptoms were 1.7× more common in LE pts and by 18mo PS, having LE doubled chance of 1 or more symptoms. By 18 mo the differences were minimal, except those w LE reported more tingling, swelling, numbness | 1 in 2 women reported moderate to extreme pain, tingling, weakness, stiffness, poor ROM, swelling, and/or numbness at 6 mo PS, but 51% reported at least 1 complaint 12 mo later |

| Hoffman (2007) | n = 80 newly diagnosed with lung cancer; 2 CCOPs and 2 Comprehensive CA centers; age range 41-83, mean 63; Caucasion 95%; Early stage - 10%; Late Stage 90%; | Given (co-author) Cancer Sympton Experience Inventory (15 symptoms; occurrence, severity, interference). | secondary data analysis from baseline of randomized clinical trial; explore relationship among pain, fatigue, insomnia, and gender. | Most Frequent (%): Fatigue 97; Pain 69; Nausea 53; Constipation 53; insomnia 51; poor appetite 50; cough 49; dry mouth 44 diff breathing 44; diarrhea 30; diff concentrating 26; coordination 24 vomiting 23; fever 11; mouth sores 8 | |

| Karabulu (2010) | 287 Turkish pts from a university hospital. 56% male, 66% had Stage II disease; mean duration since tx was 3 yrs +/- 2.5 yrs; 39% GI, 17% lung, 14% AML/ALL, 13% H&N, 12% breast. 72% had chemo only, 2% RT only & 8% chemoRT | MDASI- Turkish | cross-sectional design using hierarchical cluster analysis to identify symptom clusters and regression analysis to assess predictors of clusters | prevalence: fatigue 95.5%, difficulty remembering 91%, sadness 90%, loss of appetite 88%, enjoyment of life 89%, pain 88%, distress 87%, difficulty walking 87,5%, dry mouth 87%. Overall 37.5% had moderate and 12.5% had severe symptoms. Mean MDASI scores for 13 symptom items were 5 and 4.4 for the 6 interference items. 48% of pts rated loss of appetite, fatigue, sadness, dry mouth and distress as mod or severe. Loss of appetite was most prevalent symptom. The 6 interference symptoms formed a cluster (gen activity, mood, work relations with others, walking, enjoyment with life); a second cluster was formed with sleep disturbance, difficulty remembering, pain, distress, sadness, fatigue, dry mouth and appetite loss. A third cluster was formed with nausea, vomiting, SOB, numbness, drowsiness. | |

| Kenefick (2006) | N=55, age 60 or older (mean 68), 61%white, 37% AA, stage I or II BCA, | Symptom Distress Scale (SDS) Longitudinal data collection at hospital discharge and 3 & 6 mo post discharge. | Secondary, descriptive analysis from larger study of a home care nursing intervention on QOL of older pts newly diagnosed with several types of cancer. | SDS scores range from 13 to 65 and mean total SDS were 23.81 at discharge from hospital and 20.52 at 3 mo, and 18.6 at 6 mo. Most frequent sx were fatigue, frequency of pain, outlook and insomnia. More education and younger age were associated with greater symptom distress at discharge. | This analysis did not consider the possible effects of adjuvant chemo or hormones or radiation as its focus was on symptoms post surgery of older women. |

| Keene Sarenmalm (2007) | N=56, age 55 & older (mean 65), newly diagnosed w local, regional or distant recurrent BCA (29 had loco-regional recurrence) (1/3 had past hx of anxiety and/or depression) | MSAS, MSAS-PHYS, MSAS-PSYCH, TMSAS (total symptom burden), MSAS-GDI, HADS, Sense of Coherence (soc) measures coping capacity, PACIS, QLQ-C30, IBCSG-QOL | Descriptive study, pts recruited prospectively from 2 oncology centers, correlation analyses with multiple regressions for developing prediction model | 65% reported 10-23 symptoms (avg 14), Prevalent sx >50%: lack of energy (67%), difficulty sleeping (61%), pain (59%), worrying (59%), problems w sexual interest/activity (59%) feeling sad (57%), dry mouth (52%) | Stat sig correlations among highly related symptoms were worrying and feeling nervous, worrying and feeling sad, nausea & lack of appetite, difficulty swallowing & feeling bloated. |

| Kim (2008) | N=282, women w BCA all stages, age >30, (mean 55), 92% white, initiating rx of at least 3 cycles of chemo (44%) or 6 wks of XRT (56%) | General fatigue scale, POMS, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Side Effect Checklist. Time points-baseline pre-rx and 48 hours post rx 2 and 3. | Secondary analysis of data from RCT of cognitive behavioral rx on fatigue (1999-2002 at 2 ca ctrs), factor analysis for symptom clusters | Common factoring identified a psychoneurological symptom cluster at 1st time point: depressed mood, cognitive disturbance, fatigue, insomnia, and pain and was generalizable to all subgroups. Symptom cluster at 2nd time point included upper-GI symptoms (nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite) | Confounding variables on symptom clustering included varying CTX regimens, XRT dose, hormonal rx, surgery type and time lapse since surgery were not controlled for |

| Kiteley (2006) | n = 16 at lung cancer clinic in Toronto mean age 67; 9 men, 7 women; chemo before 1st interview - 4; btwn interviews - radiation -9, rad and chemo 2, surgery and rad 1, surgery only 1, chemo alone 1 | spontaneous reports and probes on symptoms (21 in total were identified) | semi-structured interview to describe their symptom experiences; interview at time of diagnosis and second interview 2 months later. | Out of N = 16, symptoms with greater than 25% include (#s are reported at Baseline & 2 Months later: fatigue = 14, 15; pain = 10, 9; shortness of breath = 9, 7; loss of appetite = 8, 11; cough = 8, 8; insomnia = 8, 9; mucous = 8, 9; weight loss = 8, 8; wheeze = 7, 4 | fatigue and pain most troublesome symptoms; most often cited combo of symptoms was respiratory symptoms (wheeze, cough, mucus, shortness of breath) |

| Nejmi (2010) | 165 cancer patients in Morocco (Arabic-speaking); mean age 48.7; 56% female; 8% receiving chemotherapy/14% receiving radiotherapy; 32% Stage II-III/68% Stage IV; 95% ECOG PS 2-4 (39% ECOG PS 4); 21% gastrointestinal/19% breast/15% gynecological/12% lung/8% unknown/7% genitourinary/7% head and neck/10% other | MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Arabic version (MDASI-A); Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) | Cross-sectional, descriptive, mixed methods | Mean score (0-10 scale, in order of mean severity high to low): pain (9.62); fatigue (7.05); lack of appetite (6.07); disturbed sleep (5.35); dry mouth (5.07); sadness (4.85); distress (4.33); shortness of breath (3.89); numbness (3.76); drowsiness (3.28); nausea (3.03); difficulty remembering (2.85); vomiting (2.43). % with score >/= 5 (moderate or severe; in order of incidence high to low): pain (100%); fatigue (86%); lack of appetite (79%); disturbed sleep (69%); dry mouth (68%); sadness (62%); distress (54%); shortness of breath (47%); numbness (46%); drowsiness (43%); nausea (35%); difficulty remembering (35%); vomiting (25%). % with score >/=7 (severe; in order of incidence high to low): pain (96%); fatigue (65%); lack of appetite (48%); dry mouth (30%); sadness (31%); shortness of breath (29%); distress (28%); disturbed sleep (24%); numbness (22%); drowsiness (16%); nausea (16%); difficulty remembering (16%); vomiting (15%). | Interview format; very poor performance status overall |

| Reyes-Gibby (2007) | 48 patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer receiving chemoradiation 5040 cGY in 28 fractions, capecitabine and bevacizumab) on a phase I protocol. Median of 58 years of age 9range 41-80), 92% Caucasian, equally divided between males and females. KPS was preserved (100% of teh sample with KPS>80%), however 74% had one or more comorbidities. | MDASI | Longitudinal, descriptive, with symptoms and their interference with usual function measured at baseline, weekly during treatment, and at the time of the first clinical assessment after chemoradiation | 95% of the patients reported at least one of the 13 symptoms at initial presentation. The highest mean score was observed for fatigue, followed by lack of appetite and pain. The mostly commonly reported symptoms at moderate to severe intensity over the course from presentation, during treatment and after treatment were fatigue, lack of appetite, pain, nausea and sleep disturbance. At entry to the study, 51% of the sample reported multiple symptoms that were of moderate to severe intensity, with the proportion reporting symptoms of moderate to severe intensity decreasing to 20% at the time chemoradiotherapy was concluded. Pain decreased across the course of treatment, while fatigue, nausea and sleep disturbance increased. Fatigue and appetite changes formed a distinct grouping. | |

| Shi (2010) | Forty-two patients with breast, head and neck, lung, gynecological, gastrointestinal, prostate, or brain cancer in their third to eighth week of chemoradiation. Majority female, white, >55yrs, breast cancer; 50% metastatic cancer. | To examine the effects of recall on symptom severity ratings by comparing ratings made using 24-hour and seven-day recall periods of the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI). Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS)9 was also recorded at both T1 and T2. | Cross-over design | The five most severe symptoms from both recall periods were fatigue, sleep disturbance, drowsiness, lack of appetite, and pain. Paired t-tests did not find any significant difference between the 24-hour and seven-day recall periods. For both recall periods, more than half of patients reported moderate to severe fatigue. Percentages did not differ significantly between the 24-hour and seven-day recall periods. | Comparing the 24-hour and seven-day recall periods, the correlation coefficient for total symptom severity was 0.888. All correlation coefficients for symptom severity items were >0.7 except for distress (r = 0.67). The percentages of moderate to severe symptoms (rated >5) were consistent for both recall periods, with no significant difference between recall periods in the prevalence of moderate to severe symptoms. |

| Sun (2008) | 45 patients actively receiving treatment for either hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or pancreatic cancer. The mean age was 59 years, and 64% were male. 51% Caucasian, 22% Asian, 18% Hispanic, and 4% African American participants. >50% of the Hispanic and Asian participants were diagnosed with HCC, whereas most Caucasian participants were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Tthe study sample included 22 patients with HCC and 23 patients with pancreatic cancer. The majority of participants had stage III (26%) or IV (61%) disease at the time of accrual; 82% had been diagnosed recently, and 13% had recurrent disease. | Patients were followed from baseline for three months, with outcome measures repeated monthly. Outcome measures included the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy– Hepatobiliary (FACT-Hep) and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy– Spirituality Subscale (FACIT-Sp-12). | Descriptive, longitudinal study. Descriptive analysis of demographic, treatment, and symptom data was conducted, followed by two-way repeated measures analysis of variance of FACT-Hep and FACIT-Sp-12 scale scores by diagnosis and treatment type. | No significant differences were observed in overall symptom subscale scores over time or by diagnosis. In the HCC group, the overall symptom subscale score decreased over time from baseline, one-, and two-month evaluations, but was increased at three months. For the pancreatic cancer group, overall scores stabilized between one month and two months and then decreased by the three-month evaluation. These changes were not statistically significant. Overall, symptom scores were high for weight loss, appetite, fatigue, ability to perform usual activities, and abdominal pain and tended to worsen over time. | Pearson's correlations between the disease-specific symptom subscale and each of the QOL subscale scores were computed for all four evaluations, including baseline. Results at baseline suggest that symptoms were highly correlated with physical well-being (0.72), functional well-being (0.73), and overall FACT-Hep scores (0.93). |

| Wang SY, Tsai CM, Chen BC, Lin CH, Lin CC (2008) | n - 108 lung cancer in Taiwan; oncology in and outpatient units (3 sites); mean age 68; radiation -81%; localized cancer 74% | Taiwanese version of MDASI | cross-sectional | Most Severe (mean score, range 0 -10): fatigue 6.68, sleep disturbance 6.04; lack of app 5.83; short breath 5.59; distress 5.27; drowsiness 5.19; dry mouth 5.11; pain 5.10; sadness 4.87; diff remembering 4.65; numbness 4.01; nausea 2.48; vomiting 1.35 | |

| Wang (2010) | 1433 patients were included in analyses: 524 patients from the United States, 249 from China, 256 from Japan, 226 from Russia, and 178 from Korea. Percent female: US-55, China-54, Japan-42, Russia-62, Korea-40. Mean age(SD) US-55(15.0), China-51(12.8), Japan-62(12.1), Russia-61(14.3), Korea-51(11.3). Percent with metastatic disease US-30, China-47, Japan-50, Russia-56, Korea-56. Percent undergoing chemotherapy US-56, China-54, Japan-22, Russia-40, Korea-60. | M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI), ECOG | Cross sectional, descriptive | Cross-nationally, fatigue was consistently the most prevalent moderate to severe symptom (rated ≥5 on the MDASI 0-10 scale). Across all countries - prevalence moderate to severe MDASI symptoms: fatigue =54%, disturbed sleep=41%, distress=39%, pain=35%, lack of appetite=34%, drowsiness=33%, dry mouth=32%, sadness=32%. Treatment-induced symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and numbness were consistently rated as the least severe of the 13 MDASI symptoms. MDASI symptoms severity mean(SD): fatigue =4.75 (2.95), disturbed sleep=3.73 (3.16), distress=3.60 (3.17), pain=3.16 (3.16), lack of appetite=3.25 (3.23), drowsiness=3.25 (2.92), dry mouth=3.11 (3.16), sadness=3.15 (3.13), shortness of breath=2.51 (2.92), Difficulty remembering=2.39(2.69), Numbness and tingling=2.38 (2.97), nausea=1.95 (2.86), and vomiting=1.34 (2.97). | The results of this study indicate that national and linguistic (country) variations in patient responses to the MDASI are small relative to individual patient-related factors. Analysis of MDASI symptom and interference ratings from cancer patients in five countries revealed that the variance of the random effects for country was between 20% and 50% of the inter-subject variance. |

| Wang XS, Williams LA, Eng C, Mendoza TR, Shah NA, Kirkendoll KJ, Shah PK, Trask PC, Palos GR, Cleeland CS (2010) | 184 gastrointestinal cancer patients (English-speaking in the US); median age 60; 53% female; 61% currently receiving chemotherapy/33% receiving no treatment; 34% local or regional disease/54% metastatic disease; 12% ECOG PS 2-4; 28% colon/25% pancreas/19% rectum/15% hepatobilliary/13% gastric/1% esophageal | MD Anderson Symptom Inventory plus 5 Gastrointestinal-specific symptom items (MDASI-GI); Medical Outcomes Survey 12-item Short-Form Survey (SF-12); Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) | Cross-sectional, descriptive, mixed methods | Mean score (0-10 scale, in order of mean severity high to low): fatigue (2.57); drowsiness (1.97); pain (1.87); disturbed sleep (1.66); lack of appetite (1.62); diarrhea* (1.51); numbness (1.43); distress (1.42); dry mouth (1.32); difficulty remembering (1.15); bloating* (0.98); sadness (0.95); constipation* (0.93); change in taste* (0.77); nausea (0.70); shortness of breath (0.50); vomiting (0.36); difficulty swallowing* (0.19). *=GI module | Percentage of patients experiencing each symptom not provided. |

An aggregation of the demographics for the studies is presented in Table 2 and then prevalence and severity of symptoms by paper is presented in Table 3. To allow for comparisons between the cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, where possible, mean prevalence was computed by averaging the reported values across the available time points in the longitudinal studies. When this was not possible due to missing data, the baseline values were entered into the analysis as noted on this table.

Table 2. Characteristics of papers included in synthesis.

| Study design | Race | Gender | Cancer Locations/ Types |

Cancer Stage | Treatment | Age | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Location | Cross-sectional | Longitudinal | Sample size | White | Non-White | Male | Female | Number specified when provided |

I-II | III-IV | Mets | Surgery | Chemotherapy | Radiation | Biologic agents | HSCT | min | max | mean |

| Anderson (2007) | US | 1 | 100 | 81 | 20 | 60 | 40 | H | 100 | 100 | 24 | 75 | 54 | |||||||

| Bevans, Mitchell, Marden (2008) | US | 1 | 76 | 35 | 41 | 51 | 25 | H | 76 | 76 | 18 | 71 | 40 | |||||||

| Chen ML, Chang HK (2004) | Taiwan | 1 | 121 | 66 | 55 | B= 48; D= 33; E= 40 | 18 | 60 | 43 | 26 | 81 | 52 | ||||||||

| Chen (2007) | Taiwan | 1 | 329 | 146 | 175 | A= 6; B= 93; C= 79; E= 57; H= 55; I= 24; L=7 | 77 | 197 | 173 | 233 | 22 | 97 | 61 | |||||||

| Ferreira (2008) | Brazil | 1 | 115 | 46 | 69 | B= 44; C= 6; E= 8; G= 15; I= 27; J= 12; L= 1 | 73 | 74 | 57 | 61 | 57 | |||||||||

| Gift (2004) | US | 1 | 220 | 200 | 20 | 130 | 90 | I | 84 | 136 | 92 | 95 | 139 | 65 | 89 | 72 | ||||

| Harding (2007) | US | 1 | 31 | 30 | 1 | 17 | 14 | G | 14 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 1 | 8 | 55 | |||||

| Hayes (2010) | Australia | 1 | 285 | 285 | B | 287 | 114 | 200 | 171 | 74 | 54 | |||||||||

| Hoffman (2007) | US | 1 | 80 | 76 | 4 | 44 | 36 | I | 1 | 67 | 41 | 83 | 63 | |||||||

| Karabulu (2010) | Turkey | 1 | 287 | 160 | 127 | B= 34; C= 113; E= 37; F= 15; H= 39; I= 49 | 197 | 90 | 51 | 274 | 73 | |||||||||

| Kenefick (2006) | US | 1 | 57 | 35 | 22 | 0 | 57 | B | 54 | 3 | 58 | |||||||||

| Keene Sarenmalm (2007) | Sweden | 1 | 54 | 0 | 54 | recurrent B | 32 | 24 | 10 | 7 | 42 | 55 | 79 | 65 | ||||||

| Kim (2008) | US | 1 | 282 | 258 | 24 | 0 | 282 | B | 220 | 31 | 125 | 157 | 30 | 83 | 50 | |||||

| Kiteley (2006) | Canada | 1 | 16 | 9 | 7 | I | 2 | 7 | 12 | 50 | 89 | 66 | ||||||||

| Nejmi (2010) | Moracco | 1 | 165 | 72 | 93 | B= 32; C= 35; E= 12; F= 25; G= 12; H= 4; I= 20; K= 6; L= 19 | 53 | 112 | 6 | 13 | 23 | 18 | 84 | 49 | ||||||

| Reyes-Gibby (2007) | US | 1 | 37 | 44 | 4 | 25 | 23 | C | 41 | 80 | 58 | |||||||||

| Shi (2010) | US | 1 | 42 | 25 | 17 | 10 | 32 | A, B, C, E, F, J | 19 | 23 | 19 | 60 | ||||||||

| Sun (2008) | US | 1 | 45 | 23 | 22 | 29 | 16 | C | 6 | 39 | 10 | 29 | 6 | 59 | ||||||

| Wang SY, et. al (2008) | Taiwan | 1 | 108 | 69 | 39 | I | 16 | 21 | 28 | 10 | 25 | 30 | 41 | 90 | 68 | |||||

| Wang (2010) | US, China, Japan, Russia, Korea | 1 | 1433 | 513 | 920 | Multicancer, not defined | 754 | 736 | ||||||||||||

| Wang XS, et. al (2010) | US | 1 | 184 | 146 | 38 | 87 | 97 | C&D | 31 | 85 | 10 | 112 | 25 | 20 | 84 | 60 | ||||

Cancer Type/Location: A= Brain/CNS ; B= Breast; C= Digestive/Gastrointestinal; D= Esophageal; E= Head & Neck; F= Gynecologic; G= Genitourinary/Renal; H= Hematologic; I= Lung; J= Prostate; K= stem; L= Other/Unknown

Table 3. Prevalence and severity of symptoms by paper.

|

A similar procedure was used for tabulating severity, although mean severity by symptom was often not reported. In addition, many of the studies only reported those symptoms in which the severity was classified as moderate to severe. Because there was variation in the range of the severity scales among the instruments used in the studies, mean values were linearly transformed to a 0-10 scale to facilitate comparisons. Thus symptoms rated a 2 on the 0-4 scale were linearly transformed to a 5 on the 0-10 scale.

Lastly, to assess if the most commonly used instruments asked about the most compelling symptoms to patients, thresholds by number of patients queried for the symptom were constructed. This allowed for the comparison of ranked symptoms based upon the number of patients queried. Thus symptoms that were assessed in 100 or more people were ranked by frequency and severity, symptoms assessed in 500 or more people, and then a final threshold of 1000 or more people. The lowest threshold of 100 people had the most symptoms ranked while creating the threshold of 1000 people limited the number of symptoms. Some symptoms found in this synthesis did not include query by at least 100 patients and were therefore not included in this rank ordering of symptoms by threshold level.

Characteristics of These Studies

Data were extracted from the reported studies to develop a pooled sample of 4067 cancer patients in whom the prevalence and severity of individual symptoms was reported. Individual studies contributed from 16 to 1433 participants; nine (43%) studies included a sample size less than 100. All of the investigations employed convenience samples. Eleven (52%) of the studies were conducted in the United States while the remainder were multinational as listed in the Table 2. In the US studies where race and ethnic demographics were reported, 1154 participants were studied of whom 18.5% of the samples were non-white. Studies from other nations failed to distinguish race/ethnicity. In total, the pooled sample across the 21 studies was comprised of 38% male and 62% female, with a mean age of 58 years (range: 18 to 97 years).

A majority (62%) of these studies assessed symptoms in homogeneous samples with respect to tumor site (predominantly breast and lung cancer), while 38% of the included studies utilized samples with mixed diagnoses and treatment regimens. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of participants in the included studies by cancer disease site, stage, and treatment type. Persons with breast cancer were the single largest group by cancer site (approximately 25% of patients) followed by lung (approximately 20%). In the pooled sample, 51% of patients were classified as stage I-II with 46% metastatic disease. The largest majority of study participants were treated with chemotherapy, radiation, and/or surgery. Approximately 5% additionally of the participants additionally received Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT), with symptom assessment before and after this treatment. For these two longitudinal studies, the frequency and severity of symptoms was averaged across the various assessment times for this synthesis.

Symptom Assessment Instruments

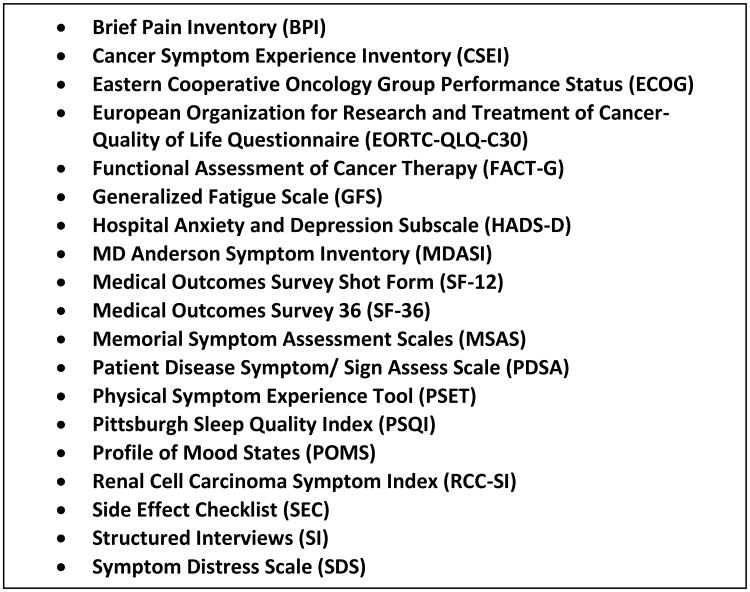

Eighteen instruments listed in Figure 2 and structured interviews were used in the 21 studies included in this synthesis. Instruments included those measuring single symptoms, multi-symptom inventories, and single symptom items drawn from HRQOL or health status measures. The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) was the most commonly used instrument in the studies analyzed (n=9 studies; 43%), while the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Subscale (HADS-D), Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form-36 (SF-36), and Symptom Distress Scale (SDS) were each employed in two studies. The remaining instruments were represented just once.

Figure 2. Instrument List.

Symptom Summary

Forty-seven symptoms were identified across the 21 studies which were then categorized into 17 logical groupings. While many studies only reported the most prevalent or severe symptoms, some reported every symptom acknowledged by patients. In an attempt to be as inclusive as possible, all symptoms reported were included in this synthesis.

A summary of the prevalence and mean severity rates (when available) for these various symptoms are provided in Table 4. This table is organized in descending order according to the prevalence of the measurement of symptom groupings as highlighted in blue. Thus, all of the studies in this synthesis measured and reported frequency and/or severity of the symptoms of fatigue and pain, 91% of the studies similarly reported symptoms of sleep issues, while only 4.5% reported on symptoms of hair loss or other appearance issues.

Table 4. Summary of pooled prevalence and pooled mean severity rates (when available).

| Number of Patients Reporting Symptom | Total sample of Patients Queried | Pooled Prevalence (%) | Mean Severity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue & Weakness (100% of studies) | ||||

| Generalized Fatigue | 2177 | 3651 | 59.63 | 4.62 |

| Tiredness/Drowsiness | 999 | 2310 | 43.25 | 3.37 |

| Lack Of Energy | 36 | 54 | 66.67 | |

| Weakness | 222 | 636 | 34.91 | 5.00 |

| Pain (100% of studies) | ||||

| Generalized/unspecified pain | 1880 | 3914 | 48.03 | 3.44 |

| Headache | 7 | 31 | 22.58 | |

| Abdominal Pain | 5.44 | |||

| Sleep Issues (91% of studies) | ||||

| Insomnia/Disturbed Sleep | 1792 | 3675 | 48.76 | 4.15 |

| Anorexia & Weight loss (91% of studies) | ||||

| Weight Loss | 129 | 321 | 40.19 | 5.94 |

| Anorexia/Appetite changes | 1539 | 3388 | 45.43 | 3.89 |

| GI Issues (81% of studies) | ||||

| Bloating | 9 | 54 | 16.67 | 0.98 |

| Bowel Changes | 108 | 260 | 41.54 | 2.13 |

| Constipation | 117 | 349 | 33.52 | 2.25 |

| Feeling Sick | 18 | 100 | 18.00 | 2.20 |

| N&V | 61 | 236 | 25.85 | 1.20 |

| Nausea | 670 | 1672 | 40.07 | 2.50 |

| Vomiting | 392 | 1459 | 26.87 | 2.09 |

| Diarrhea | 52 | 349 | 14.90 | 1.15 |

| Affect (76% of studies) | ||||

| Depression/Sadness | 983 | 2856 | 34.42 | 2.70 |

| Irritability | 44 | 85 | 51.76 | |

| Worry | 58 | 161 | 36.02 | 7.75 |

| Feeling Nervous | 23 | 54 | 42.59 | |

| Distress | 887 | 2149 | 41.28 | 2.36 |

| Outlook | 35 | 57 | 61.40 | 2.00 |

| Respiratory Issues (76% of studies) | ||||

| Cough | 208 | 401 | 51.87 | 5.13 |

| Wheezing | 5 | 16 | 31.25 | |

| Difficulty breathing/Dyspnea | 681 | 1560 | 43.65 | 2.78 |

| Impaired Cognition (67% of studies) | ||||

| Difficulty Concentrating/Remembering | 693 | 1590 | 43.58 | 3.05 |

| Oral & Swallowing Issues (62% of studies) | ||||

| Altered Taste | 87 | 274 | 31.75 | 3.50 |

| Dry Mouth | 1248 | 2610 | 47.82 | 3.49 |

| Oral Lesions | 12 | 234 | 5.13 | 0.45 |

| Dysphagia | 69 | 274 | 25.18 | 3.13 |

| Neurologic Issues (57% of studies) | ||||

| Poor Coordination | 55 | 300 | 18.33 | 5.37 |

| Mobility | 29 | 285 | 10.18 | |

| Dizziness | 80 | 305 | 26.23 | 4.68 |

| Numbness/Tingling | 364 | 875 | 41.60 | 2.21 |

| Unspecified Neurologic | 4 | 184 | 2.17 | |

| Edema (29% of studies) | ||||

| Edema | 102 | 711 | 14.35 | 6.57 |

| Urinary Elimination Issues (19% of studies) | ||||

| Urinary problems | 14 | 85 | 16.47 | 4.25 |

| Nocturia | 379 | 507 | 74.75 | 4.07 |

| Skin and Wound Issues (19% of studies) | ||||

| Skin changes | 7 | 54 | 12.96 | |

| Wound/Pressure Sore | 21 | 121 | 17.36 | |

| Itching | 13 | 134 | 9.70 | 4.15 |

| Hot Flashes/sweating (14% of studies) | ||||

| Hot Flashes/sweating | 156 | 556 | 28.06 | 6.47 |

| Fever (14% of studies) | ||||

| Fever | 19 | 111 | 17.12 | 2.81 |

| Sexual Dysfunction (10% of studies) | ||||

| Sexual Dysfunction | 101 | 274 | 36.86 | 6.90 |

| Hair Loss/Appearance (5% of studies) | ||||

| Hair Loss/Appearance | 34 | 161 | 21.12 |

The pooled prevalence and mean severities reported in Table 4 were calculated by aggregating all queries for that specific symptom across studies to provide a pooled prevalence per symptom. Where possible, symptoms of the same nature but labeled differently such as anorexia and decreased appetite were combined into one symptom. This was possible when only one term was used in a study providing one statistic; however, some symptom terms which could be synonymous for each other were often reported as separate items in the same study. Examples include the terms “fatigue”, “lack of energy”, and “weakness”. Each is listed separately in this synthesis to assure the capture of constructs that may be related but distinct. Of note, while all of studies measured and thus reported the symptom of fatigue, 59.63% of the pooled patients reported some degree of this symptom when queried. Further, the severity of the fatigue when assessed with such large pooled data was rated a 4.62 on a 0-10 scale.

Symptom Prevalence

Given the large spread of sample sizes, the variety of instruments utilized and the identification of 47 separate symptoms presented in Table 3, it was determined that the most appropriate method to rank symptoms in a systematic, unbiased, and interpretable fashion was to compare the symptom prevalence by aggregated sample size thresholds. Three thresholds were constructed for combined samples of greater than 100 patients, greater than 500 patients and greater than 1000 patients who were queried for the symptom. Thus the most inclusive threshold was 100 taking into account all symptoms in which at least 100 patients across studies were queried. Not included in this analysis then were symptoms such as irritability which was only assessed in a total of 85 patients in 2 studies or headache included in only one study of 31 patients.

As depicted in Table 5 depending upon the threshold level selected, the rank order of the prevalence changed. For a threshold of 100 patients, Nocturia was the most frequently reported symptom followed by Fatigue and Cough. When the threshold was raised to a minimum of 500 patients assessed for the symptom, Cough was replaced by Insomnia/Disturbed Sleep. Finally, when raised to a sample threshold of 1000 patients, Fatigue, Insomnia/Disturbed Sleep, and Pain are the top three most reported symptoms. Thus as will be discussed later, while nocturia was the most prevalent symptom with 74.8% of patients reporting, it was only queried in 507 patients in 2 studies.[45,49]

Table 5. Rank ordering of symptom prevalence by sample threshold.

| Number of Patients Reporting Symptom | Total sample of Patients Queried | Prevalence ordering of symptoms in Sample >1000 | Prevalence ordering of symptoms in Sample >500 | Prevalence ordering of symptoms in Sample >100 | Pooled Prevalence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Fatigue | 2177 | 3651 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 59.6 |

| Insomnia/Disturbed Sleep | 1792 | 3675 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 48.8 |

| Pain | 1880 | 3914 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 48.0 |

| Dry Mouth | 1248 | 2610 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 47.8 |

| Anorexia/Appetite changes | 1539 | 3388 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 45.4 |

| Difficulty breathing/Dyspnea | 681 | 1560 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 43.7 |

| Difficulty Concentrating/Remembering | 693 | 1590 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 43.6 |

| Tiredness/Drowsiness | 999 | 2310 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 43.2 |

| Distress | 887 | 2149 | 9 | 41.3 | ||

| Nausea | 670 | 1672 | 10 | 40.1 | ||

| Nocturia | 379 | 507 | 1 | 1 | 74.8 | |

| Cough | 208 | 401 | 3 | 51.9 | ||

| Numbness/Tingling | 364 | 875 | 10 | 41.6 |

Symptom Severity

A similar approach was taken in evaluating the symptom severity, and is presented in Table 6. In studies with a sample threshold of 100 patients, Worry had the highest mean severity followed by Sexual Dysfunction and Edema. By comparison, when the higher threshold of 500 patients was selected, most of the symptoms in the lower threshold of 100 patients were removed and by the 1000 patient threshold, all but one symptom was replaced with the top three being Fatigue, Insomnia/Disturbed Sleep, and Anorexia/Appetite changes. As with the symptom prevalence, fewer studies assessed worry (three studies)[41,46,51] and sexual dysfunction (two studies)[45,51] resulting in a smaller patient pool, yet the compelling severity reported may indicate the need for further assessment as a routine symptom measure.

Table 6. Rank ordering of symptom severity by sample threshold.

| Number of Patients Reporting Symptom | Total sample of Patients Queried | Prevalence ordering of symptoms in Sample >1000 | Prevalence ordering of symptoms in Sample >500 | Prevalence ordering of symptoms in Sample ≥100 | Mean Severity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Fatigue | 2177 | 3651 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 4.62 |

| Insomnia/Disturbed Sleep | 1792 | 3675 | 2 | 5 | 4.15 | |

| Anorexia/Appetite Changes | 1539 | 3388 | 3 | 7 | 3.89 | |

| Dry Mouth | 1248 | 2610 | 4 | 8 | 3.49 | |

| Pain | 1880 | 3914 | 5 | 9 | 3.44 | |

| Tiredness/Drowsiness | 999 | 2310 | 6 | 10 | 3.37 | |

| Difficulty Concentrating/Remembering | 693 | 1590 | 7 | 3.05 | ||

| Difficulty breathing/Dyspnea | 681 | 1560 | 8 | 2.78 | ||

| Depression/Sadness | 983 | 2856 | 9 | 2.70 | ||

| Nausea | 670 | 1672 | 10 | 2.50 | ||

| Edema | 102 | 711 | 1 | 3 | 6.57 | |

| Weakness | 222 | 636 | 3 | 8 | 5.00 | |

| Hot Flashes/Sweating | 156 | 556 | 2 | 4 | 6.47 | |

| Nocturia | 379 | 507 | 6 | 4.07 | ||

| Cough | 208 | 401 | 7 | 5.13 | ||

| Weight Loss | 129 | 321 | 5 | 5.94 | ||

| Dizziness | 80 | 305 | 9 | 4.68 | ||

| Poor Coordination | 55 | 300 | 6 | 5.37 | ||

| Sexual Dysfunction | 101 | 274 | 2 | 6.90 | ||

| Worry | 58 | 161 | 1 | 7.75 |

Discussion

Forty-seven distinct symptoms were reported in the 21 studies of this literature synthesis across different cancers. Most studies employed instruments that assessed for symptoms of Fatigue & Weakness (100% of studies), Pain (100% of studies), Sleep Issues (91% of studies), Anorexia & Weight loss (91% of studies), GI Issues such as nausea and vomiting (81% of studies), Affect issues such as depression and irritability (76% of studies), and Respiratory Issues such as cough and dyspnea (76% of studies). Fewer studies assessed symptoms related to Urinary Elimination Issues (19% of studies), Skin and Wound Issues (19% of studies), Hot Flashes/sweating (14% of studies), Sexual Dysfunction (10% of studies), Fever (14% of studies), and Hair Loss/Appearance (5% of studies), yet the prevalence and severity of some of these symptoms was greater than the more commonly assessed symptoms.

This disparity is most obvious when evaluating the prevalence and severity by threshold levels. Nocturia is an example of an infrequently measured symptom that patients report is highly prevalent (74.8%) and moderately severe (4.07 on scaled of 0-10). Further analysis of the two studies that assessed for nocturia reveals that one study was completed in the US and the other in Turkey, that adequate sample sizes of 220 and 287 were included, and that various cancer sites were involved with lung being the predominant cancer.[45,49] Given the heterogeneous nature of the studies, this finding suggests that nocturia is a symptom that has been infrequently assessed, but which necessitates further systematic evaluation and consideration as a symptom to assess in a broad range of cancers. Similar arguments can be made for sexual dysfunction[45,51] and cough[45,46,48,51,53] which each were reported by patients in disparate studies (nation, cancer site, sample sizes) as highly prevalent and of moderate to high severity.

Findings from this literature synthesis are most useful when compared with the research synthesis by Esther Kim et. al.[25] Many similarities between the two syntheses exist including the similar mean age of 58 and 59 years, a predominance of heterogeneous cancer diagnoses (62% and 50%), and when reported for US studies, an approximate 18% non-Caucasian sample. Differences include a greater range of sample sizes in this present analysis (16- 1433 compared to 26-527) and a greater proportion of females in this analysis (62% vs. 48%). Whereas Esther Kim et. al. limited their review to only studies that employed the MDASI, MSAS, or the SDS, this present analysis included studies employing any symptom assessment tools.

Table 7 presents a comparison of the most prevalent symptoms in this synthesis to the top 10 identified by Esther Kim et. al. These are presented in descending prevalence for this current synthesis. All but three of the symptoms (nocturia, outlook, and weakness) included in this synthesis were also included in the Esther Kim et. al. synthesis. Unfortunately, the synthesis by Esther Kim et. al. only published the aggregation of the top 10 symptoms. As presented in this table, while the vast majority of symptoms were assessed (as indicated by the instrument used), comparisons cannot be drawn because the pooled prevalence numbers for all but the top 10 symptoms were not published. In comparing our findings to those of Esther Kim et.al., similarities in the prevalence of fatigue, insomnia, dry mouth, tiredness, feeling nervous, distress, and depression were noted, however differences are observed between the rates of irritability, pain, and worry are evident. Further, highly prevalent symptoms such as nocturia, lack of energy, outlook, cough, anorexia, dyspnea, and difficulty concentrating did not make Esther Kim et. al.'s list of the most prevalent symptoms. The Kim study did not aggregate severity data.

Table 7.

Comparison of Prevalence statistics between this literature synthesis and Esther Kim et. al.

| Pooled Prevalence | Mean Severity | Esther Kim et. al. Prevalence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nocturia | 74.75 | 4.07 | * |

| Lack Of Energy | 66.67 | MSAS | |

| Outlook | 61.4 | 2 | * |

| Generalized Fatigue | 59.63 | 4.62 | 62% |

| Cough | 51.87 | 5.13 | MSAS |

| Irritability | 51.76 | 37% | |

| Insomnia/Disturbed Sleep | 48.76 | 4.15 | 41% |

| Generalized/unspecified pain | 48.03 | 3.44 | 36% |

| Dry Mouth | 47.82 | 3.49 | 42% |

| Anorexia/Appetite changes | 45.43 | 3.89 | MDASI, MSAS, SDS |

| Difficulty breathing/Dyspnea | 43.65 | 2.78 | MDASI, MSAS, SDS |

| Difficulty Concentrating/Remembering | 43.58 | 3.05 | MDASI, MSAS, SDS |

| Tiredness/Drowsiness | 43.25 | 3.37 | 36% |

| Feeling Nervous | 42.59 | 45% | |

| Numbness/Tingling | 41.6 | 2.21 | MDASI & MSAS |

| Bowel Changes | 41.54 | 2.13 | MSAS & SDS |

| Distress | 41.28 | 2.36 | 34% |

| Weight Loss | 40.19 | 5.94 | MSAS |

| Nausea | 40.07 | 2.5 | MDASI, MSAS, SDS |

| Sexual Dysfunction | 36.86 | 6.9 | MSAS |

| Worry | 36.02 | 7.75 | 54% |

| Weakness | 34.91 | 5 | * |

| Depression/Sadness | 34.42 | 2.7 | 39% |

Key for symptom assessment in the Esther Kim et. al. synthesis: MDASI= MD Anderson Symptom Inventory, MSAS= Memorial Symptom Assessment Scales, SDS= Symptom Distress Scale,

=not assessed

Limitations and Future Directions

As with any literature synthesis, findings must be tempered by acknowledging publication bias as only published manuscripts were included in this literature synthesis. Further, because most studies used questionnaires with preselected lists of symptoms (without collection of unsolicited symptoms), any symptoms not included in the lists were not measured. Therefore, systematic under-reporting of symptoms which could be prevalent and severe in a population is possible in the included studies. An example of this is nocturia, which when elicited was prevalent and severe, but was infrequently systematically elicited in studies. Future studies should included a two-step methodology, starting with qualitative work in which patients in a given population are interviewed in groups or individually to determine likely prevalent and severe symptoms, followed by questionnaire administration in a larger sample. Over-representation of studies in breast, colorectal and lung cancer may have yielded a disproportionate influence on the results, and work parallel to this paper supported by the NCI is evaluating prevalence and severity of symptoms by cancer type and stage.

It is unclear if symptoms reported in this analysis are attributable to the morbidity of cancer, to side effects of treatment, to accumulated toxicities of prior treatment, or to comorbidities. As previously noted, this is a synthesis of cross-sectional studies and longitudinal studies whereby symptoms in the longitudinal studies were average across the measurement times, and no control was made for cross-sectional sampling related to the time of symptom measurement (i.e.: at diagnosis, following treatment, or at another arbitrary point in time). In addition, attribution is beyond the scope of this paper, but is a salient consideration because the impetus for measuring symptoms in a given clinical trial may be contingent on the cause of the symptom. For example, a trial seeking to evaluate whether a cancer-related symptom improves with active treatment may yield a negative result if the principal driver of measured symptoms is toxicity or comorbidity. Therefore, any given clinical trial aiming to measure symptoms should provide a rationale specific to the population and interventions regarding why particular symptoms were selected, and their suspected cause and hypothesized direction of change.

This synthesis is focused on the prevalence and severity of symptoms and did not assess measures of health-related quality of life domains such as enjoyment of life or physical functioning. Future work will evaluate these areas.

Conclusion

Symptoms are prevalent and severe among patients with cancer. Therefore, any clinical study seeking to evaluate the impact of treatment on patients should consider including measurement of symptoms. Without such an assessment, the picture of the patient experience is incomplete.[61] Symptoms may be due to various etiologies, and understanding their trajectories in a given context is essential to profiling both the benefits and harms of treatment. This study demonstrates that a discrete set of symptoms is common across cancer types. This set may serve as the basis for defining a “core” set of symptoms to be recommended for elicitation across cancer clinical trials, particularly among patients with advanced disease. Indeed, the NCI is currently engaged in such an activity, which serves as the impetus for this review. It is notable that a number of existing multi-symptom questionnaires already include a set of pre-specified of symptoms. It is the authors' hope that the data included in this review will assist in the design of future studies and questionnaires, and in improved methods for assessing the prevalence and severity of symptoms in cancer populations.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest: This research was sponsored in part through program funding of the National Institute of Health/National Cancer Institute. Some of the authors currently receive grant funding from the NIH/NCI and others work directly for NIH/NCI. This manuscript has been cleared by NHI/NCI for publication. The authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review the data if requested.

Contributor Information

Carolyn Miller Reilly, Emory University, Atlanta GA.

Deborah Watkins Bruner, Emory University, Atlanta GA.

Sandra A. Mitchell, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda MD.

Lori M. Minasian, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda MD.

Ethan Basch, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY.

Amylou C. Dueck, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ.

David Cella, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL.

Bryce B. Reeve, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC.

References

- 1.Fisch MJ, Lee JW, Weiss M, Wagner LI, Chang VT, Cella D, Manola JB, Minasian LM, McCaskill-Stevens W, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Prospective, observational study of pain and analgesic prescribing in medical oncology outpatients with breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(16):1980–1988. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):865–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kozminski MA, Neumann PJ, Nadler ES, Jankovic A, Ubel PA. How long and how well: oncologists' attitudes toward the relative value of life-prolonging v. quality of life-enhancing treatments. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(3):380–385. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10385847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirkbride P, Tannock IF. Trials in palliative treatment--have the goal posts been moved? Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(3):186–187. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70041-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basch E, Jia X, Heller G, Barz A, Sit L, Fruscione M, Appawu M, Iasonos A, Atkinson T, Goldfarb S, Culkin A, Kris MG, Schrag D. Adverse symptom event reporting by patients vs clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(23):1624–1632. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kagan KO, Schmidt M, Kuhn U, Kimmig R. Ventricular outflow obstruction, valve aplasia, bradyarrhythmia, pulmonary hypoplasia and non-immune fetal hydrops because of a large rhabdomyoma in a case of unknown tuberous sclerosis: a prenatal diagnosed cardiac rhabdomyoma with multiple symptoms. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004;111(12):1478–1480. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SQ, Zou SQ, Dai QB, Li H. Clinical analysis of solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: report of 15 cases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7(2):196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen KW, Turner FD. A case study of simultaneous recovery from multiple physical symptoms with medical qigong therapy. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(1):159–162. doi: 10.1089/107555304322849075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarwal M, Hamilton JB, Moore CE, Crandell JL. Predictors of depression among older African American cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(2):156–163. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181bdef76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dirksen SR, Belyea MJ, Epstein DR. Fatigue-based subgroups of breast cancer survivors with insomnia. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(5):404–411. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181a5d05e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu MR, Rosedale M. Breast Cancer Survivors' Experiences of Lymphedema-Related Symptoms. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;38(6):849–859. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rischer J, Scherwath A, Zander AR, Koch U, Schulz-Kindermann F. Sleep disturbances and emotional distress in the acute course of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2009;44(2):121–128. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Given B, Wyatt G, Given C, Sherwood P, Gift A, DeVoss D, Rahbar M. Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(6):1105–1117. doi: 10.1188/04.onf.1105-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh D, Rybicki L. Symptom clustering in advanced cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2006;14(8):831–836. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0899-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton W, Round A, Sharp D, Peters TJ. Clinical features of colorectal cancer before diagnosis: a population-based case–control study. British Journal of Cancer. 2005;93(4):399–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh Y, Vaidya P, Hemandas AK, Singh KP, Khakurel M. Colorectal carcinoma in Nepalese young adults:presentation and outcome. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2002;29(Suppl 1):223–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruera E. Patient-Controlled Methylphenidate for the Management of Fatigue in Patients With Advanced Cancer: A Preliminary Report. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(23):4439–4443. doi: 10.1200/jco.2003.06.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delaunoit T, Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Morton RF, Fuchs CS, Findlay BP, Thomas SP, Salim M, Schaefer PL, Stella PJ, Green E, Mailliard JA. Mortality associated with daily bolus 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin administered in combination with either irinotecan or oxaliplatin. Cancer. 2004;101(10):2170–2176. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engstrom CA. Hot flashes in prostate cancer: state of the science. Am J Mens Health. 2008;2(2):122–132. doi: 10.1177/1557988306298802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenhoff S, Hjorth M, Turesson I, Westin J, Gimsing P, Wisloff F, Ahlberg L, Carlson K, Christiansen I, Dahl IM, Forsberg K, Brinch L, Hammerstrom J, Johnsen HE, Knudsen LM, Linder O, Mellqvist UH, Nesthus I, Nielsen JL. Intensive therapy for multiple myeloma in patients younger than 60 years. Long-term results focusing on the effect of the degree of response on survival and relapse pattern after transplantation. Haematologica. 2006;91(9):1228–1233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Obed JY, Bako B, Usman JD, Moruppa JY, Kadas S. Uterine fibroids: risk of recurrence after myomectomy in a Nigerian population. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2010;283(2):311–315. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1355-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schumacher KL, Koresawa S, West C, Hawkins C, Johnson C, Wais E, Dodd M, Paul SM, Tripathy D, Koo P, Miaskowski C. Putting cancer pain management regimens into practice at home. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23(5):369–382. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taskila T, Wilson S, Damery S, Roalfe A, Redman V, Ismail T, Hobbs R. Factors affecting attitudes toward colorectal cancer screening in the primary care population. British Journal of Cancer. 2009;101(2):250–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theobald DE, Kirsh KL, Holtsclaw E, Donaghy K, Passik SD. An open-label, crossover trial of mirtazapine (15 and 30 mg) in cancer patients with pain and other distressing symptoms. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23(5):442–447. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esther Kim JE, Dodd MJ, Aouizerat BE, Jahan T, Miaskowski C. A Review of the Prevalence and Impact of Multiple Symptoms in Oncology Patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;37(4):715–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen ML, Tseng HC. Symptom clusters in cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2006;14(8):825–830. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donovan HS, Hartenbach EM, Method MW. Patient–provider communication and perceived control for women experiencing multiple symptoms associated with ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2005;99(2):404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okuyama T, Wang XS, Akechi T, Mendoza TR, Hosaka T, Cleeland CS, Uchitomi Y. Japanese version of the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory: A validation study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;26(6):1093–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang XS. Longitudinal Study of the Relationship Between Chemoradiation Therapy for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer and Patient Symptoms. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(27):4485–4491. doi: 10.1200/jco.2006.07.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avery KNL, Metcalfe C, Barham CP, Alderson D, Falk SJ, Blazeby JM. Quality of life during potentially curative treatment for locally advanced oesophageal cancer. British Journal of Surgery. 2007;94(11):1369–1376. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhavnani SK, Bellala G, Ganesan A, Krishna R, Saxman P, Scott C, Silveira M, Given C. The nested structure of cancer symptoms. Implications for analyzing co-occurrence and managing symptoms. Methods Inf Med. 2010;49(6):581–591. doi: 10.3414/me09-01-0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown CG, McGuire DB, Peterson DE, Beck SL, Dudley WN, Mooney KH. The experience of a sore mouth and associated symptoms in patients with cancer receiving outpatient chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(4):259–270. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181a38fc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miaskowski C, Cooper BA, Paul SM, Dodd M, Lee K, Aouizerat BE, West C, Cho M, Bank A. Subgroups of patients with cancer with different symptom experiences and quality-of-life outcomes: a cluster analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33(5):E79–89. doi: 10.1188/06.onf.e79-e89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saitoh E, Yokomizo Y, Chang CH, Eremenco S, Kaneko H, Kobayashi K. Cross-cultural validation of the Japanese version of the lung cancer subscale on the functional assessment of cancer therapy-lung. J Nihon Med Sch. 2007;74(6):402–408. doi: 10.1272/jnms.74.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sikorskii A, Given CW, You M, Jeon S, Given BA. Response analysis for multiple symptoms revealed differences between arms of a symptom management trial. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(7):716–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walke LM, Byers AL, Gallo WT, Endrass J, Fried TR. The Association of Symptoms with Health Outcomes in Chronically Ill Adults. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;33(1):58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang XS, Shi Q, Williams LA, Cleeland CS, Mobley GM, Reuben JM, Lee BN, Giralt SA. Serum interleukin-6 predicts the development of multiple symptoms at nadir of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2008;113(8):2102–2109. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yun YH, Mendoza TR, Kang IO, You CH, Roh JW, Lee CG, Lee WS, Lee KS, Bang SM, Park SM, Cleeland CS, Wang XS. Validation Study of the Korean Version of the M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2006;31(4):345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gift AG, Stommel M, Jablonski A, Given W. A cluster of symptoms over time in patients with lung cancer. Nurs Res. 2003;52(6):393–400. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson KO, Giralt SA, Mendoza TR, Brown JO, Neumann JL, Mobley GM, Wang XS, Cleeland CS. Symptom burden in patients undergoing autologous stem-cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2007;39(12):759–766. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bevans MF, Mitchell SA, Marden S. The symptom experience in the first 100 days following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) Supportive Care in Cancer. 2008;16(11):1243–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0420-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen ML, Chang HK. Physical symptom profiles of depressed and nondepressed patients with cancer. Palliat Med. 2004;18(8):712–718. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm950oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen ML, Lin CC. Cancer Symptom Clusters: A Validation Study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;34(6):590–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferreira KASL, Kimura M, Teixeira MJ, Mendoza TR, da Nóbrega JCM, Graziani SR, Takagaki TY. Impact of Cancer-Related Symptom Synergisms on Health-Related Quality of Life and Performance Status. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;35(6):604–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gift AG, Jablonski A, Stommel M, Given CW. Symptom clusters in elderly patients with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(2):202–212. doi: 10.1188/04.onf.202-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harding G, Cella D, Robinson D, Mahadevia PJ, Clark J, Revicki DA. Symptom burden among patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC): content for a symptom index. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2007;5(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayes SC, Rye S, Battistutta D, Newman B. Prevalence of upper-body symptoms following breast cancer and its relationship with upper-body function and lymphedema. Lymphology. 2010;43(4):178–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffman AJ, Given BA, von Eye A, Gift AG, Given CW. Relationships among pain, fatigue, insomnia, and gender in persons with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(4):785–792. doi: 10.1188/07.onf.785-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karabulu N, Erci B, Özer N, Özdemir S. Symptom clusters and experiences of patients with cancer. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010;66(5):1011–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kenefick AL. Patterns of symptom distress in older women after surgical treatment for breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33(2):327–335. doi: 10.1188/06.onf.327-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kenne Sarenmalm E, Öhlén J, Jonsson T, Gaston-Johansson F. Coping with Recurrent Breast Cancer: Predictors of Distressing Symptoms and Health-Related Quality of Life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;34(1):24–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim HJ, Barsevick AM, Tulman L, McDermott PA. Treatment-Related Symptom Clusters in Breast Cancer: A Secondary Analysis. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;36(5):468–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kiteley CA, Fitch MI. Understanding the symptoms experienced by individuals with lung cancer. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2006;16(1):25–36. doi: 10.5737/1181912x1612530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nejmi M, Wang XS, Mendoza TR, Gning I, Cleeland CS. Validation and Application of the Arabic Version of the M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory in Moroccan Patients With Cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2010;40(1):75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reyes-Gibby CC, Chan W, Abbruzzese JL, Xiong HQ, Ho L, Evans DB, Varadhachary G, Bhat S, Wolff RA, Crane C. Patterns of Self-Reported Symptoms in Pancreatic Cancer Patients Receiving Chemoradiation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;34(3):244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi Q, Trask PC, Wang XS, Mendoza TR, Apraku WA, Malekifar M, Cleeland CS. Does Recall Period Have an Effect on Cancer Patients' Ratings of the Severity of Multiple Symptoms? Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2010;40(2):191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun V, Ferrell B, Juarez G, Wagman LD, Yen Y, Chung V. Symptom concerns and quality of life in hepatobiliary cancers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(3):E45–52. doi: 10.1188/08.onf.e45-e52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang SY, Tsai CM, Chen BC, Lin CH, Lin CC. Symptom Clusters and Relationships to SymptomI nterference with Daily Life in Taiwanese Lung Cancer Patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;35(3):258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang XS, Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Yun YH, Wang Y, Okuyama T, Johnson VE. Impact of Cultural and Linguistic Factors on Symptom Reporting by Patients With Cancer. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102(10):732–738. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang XS, Williams LA, Eng C, Mendoza TR, Shah NA, Kirkendoll KJ, Shah PK, Trask PC, Palos GR, Cleel CS. Validation and application of a module of the M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory for measuring multiple symptoms in patients with gastrointestinal cancer (the MDASI-GI) Cancer. 2010;116(8):2053–2063. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Basch E. Beyond the FDA PRO Guidance: Steps toward Integrating Meaningful Patient-Reported Outcomes into Regulatory Trials and US Drug Labels. Value in Health. 2012;15(3):401–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.03.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]