Abstract

Context:

Very few women have leadership positions in athletic training (ie, head athletic training positions) in intercollegiate athletics. Research exists on the barriers to attaining the role; however, our understanding about the experiences of those currently engaged in the role is limited.

Objective:

To examine the experiences of female head athletic trainers as they worked toward and attained the position of head athletic trainer.

Design:

Qualitative study.

Setting:

National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting.

Patients or Other Participants:

Eight female athletic trainers serving in the role of head athletic trainer participated in our study. The mean age of the participants was 45 ± 12 years, with 5 ± 1.5 years of experience in the role of head athletic trainer and 21 ± 10 years of experience as athletic trainers.

Data Collection and Analysis:

We conducted phone interviews with the 8 participants following a semistructured format. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed following a general inductive approach as described by Thomas. To establish credibility, we used a peer reviewer, member checks, and multiple-analyst triangulation.

Results:

Six major themes emerged from our analysis regarding the experiences of female head athletic trainers. Opportunities to become a head athletic trainer, leadership qualities, and unique personal characteristics were discussed as factors leading to the assumption of the role of the head athletic trainer. Where women hold back, family challenges, and organizational barriers speak to the potential obstacles to assuming the role of head athletic trainer.

Conclusions:

Female head athletic trainers did not seek the role, but through persistence and encouragement, they find themselves assuming the role. Leadership skills were discussed as important for success in the role of head athletic trainer. Life balancing and parenting were identified as barriers to women seeking the role of head athletic trainer.

Key Words: gender, leadership, socialization, career advancement

Key Points

Female athletic trainers who assumed the role of the head athletic trainer did so because of persistence and strong leadership skills. Many were promoted to the rank of head athletic trainer within their own organizations due to strong job performance.

Reluctance and life-balancing concerns emerged as barriers to female athletic trainers assuming the role of the head athletic trainer position. The increase in administrative responsibilities and resulting additional demands on their time were potential problems for female athletic trainers.

Since the passage of Title IX legislation, more women have assumed positions within athletic training at the intercollegiate level. Women represented 46.4% of graduate assistant athletic trainers and 47% of assistant or associate athletic trainers in 2010.1 However, the number of women advancing in the field, specifically to head athletic trainer positions within Division I of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, has not increased significantly. Women held the fewest head and assistant athletic training positions at the Division I level,2 only 17.5% of the head athletic trainer positions in 2012.1 Scant research is available to address why so few women are in head athletic trainer positions. To date, only 1 author3 has examined the experiences of women in head athletic trainer positions at the Division I level.

Outside the athletic training literature, gender stereotyping and factors limiting the advancement of women in administrative or leadership roles have been described.4–8 Within the athletic training literature, scholars have examined how gender-role stereotyping and concerns about power have negatively influenced female athletic trainers, particularly when they are providing athletic training services to male sports or interacting with male coaches while providing athletic training services at the Division I level.9 Moreover, additional researchers have suggested that many women transition away from the Division I level to less demanding positions and careers as a result of kinship responsibilities,10 parenthood,11 and life balancing,12 which may preclude them from eventually assuming the role of head athletic trainer. Also, Gorant3 noted that female athletic trainers expressed an aversion to the role of head athletic trainer, as that person often assumes the position of lead athletic trainer in charge of football. Providing athletic training services at the Division I level is considered a daunting task requiring long hours; coupling those with the additional administrative responsibilities that accompany the role of the head athletic trainer and the responsibilities of a football sport assignment may deter an athletic trainer from pursuing the role. Gorant3 found that female athletic trainers were reluctant to assume leadership roles as a result of lack of confidence or self-identified lack of skill sets necessary to lead.3 Our purpose was to build upon the work of Gorant,3 as she was the first to examine the barriers female athletic trainers perceived to assuming the role of the head athletic trainer.

Challenges to Advancement to Head Athletic Trainer

Career advancement for female athletic trainers has been described as limited or difficult to achieve.3 Gender stereotyping has been anecdotally and empirically cited as a barrier to career advancement for female athletic trainers in the Division I setting.3,9,13 Other barriers that have been examined within the athletic training literature include work-family conflict,6,14,15 kinship responsibility,7 parenthood,3 incongruent role perceptions8 in collegiate athletic settings, and gender stereotyping of young female athletic trainers early in their careers.9 However, many women have been able to persist in athletic training despite these barriers.3 Specifically, a female athletic trainer is more likely to remain in a position that allows her to adequately and efficiently assume all her roles, which may include mother, caretaker, and spouse.15 Although data are limited on female athletic trainers and their decisions regarding leadership positions, the existing literature indicates some women report higher levels of job satisfaction in lower-ranking positions,16,17 notably because of the ability to balance work and family obligations.18,19 Work as an athletic trainer at the collegiate level is time intensive, which limits the ability to fulfill other roles and responsibilities, such as those of caregiver, spouse, or mom.20

Gender-role stereotypes are at times applied to women working in male-dominated areas,21–23 especially in collegiate athletics. Ohkubo13 found that gender stereotypes existed within the Division I setting for the female athletic trainer, as student-athletes perceived them to serve in the role of nurturer or “mom.” Burton et al9 reported that young female athletic trainers were subject to informal work practices that prevented them from covering the higher-profile sports of men's basketball and football. In addition, male coaches stereotyped young, female athletic trainers as potential sexual distractions to their athletes, which also served to minimize their professional competence and ability to work with high-profile men's sports.9

Mentorship Support for Female Advancement in Athletic Training

Socialization is a process whereby individuals learn their professional roles and responsibilities through formal and informal training.24,25 Mentorship has been identified as a necessary facilitator for professional development because the mentor provides guidance, context, and understanding regarding professional expectations, behaviors, and skills. In a recent study examining sex discrimination in the Division I setting, Burton and colleagues9 found that female athletic trainers were able to manage situations of sex discrimination because of professional role modeling or mentorship by a peer or supervising athletic trainer. Based on findings of recent investigations,26,27 examining the balance between motherhood and the role of a Division I athletic trainer, mentorship has been viewed as a critical factor to help retain more women in the workplace. Also, role models and mentors can both assist athletic trainers in the Division I setting to navigate the bureaucratic and political environment of intercollegiate athletics26 and advise young professionals on career advancement and how to improve job satisfaction.27

Given the low percentage of women working in head athletic training positions in Division I intercollegiate athletics (15.2%), the purpose of our study was to examine the experiences of women working in those positions. We hoped that by examining their experiences, we could develop a better understanding of what opportunities have led them to those positions, what personal characteristics and organizational contexts have supported their advancement, and what challenges and barriers they have overcome to reach the leadership level in athletic training.

METHODS

Maxwell28 suggested qualitative methods are best used when attention to lay knowledge is a primary research purpose, as was the case with our investigation; we were concerned with the experiences of female athletic trainers in the role of head athletic trainer. Interviewing allowed the participants to recount their work experiences and perceptions of their roles as head athletic trainers.28 Open-ended interview questions permitted us to uncover and understand what lay behind any phenomena about which little was known.29 This type of methodologic design supported our research, as few analyses regarding the underrepresentation of women in head athletic trainer positions in Division I intercollegiate athletics have been conducted.

Participants

We used a criterion-sampling strategy30 to recruit 8 female participants for our study; criteria consisted of employment in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting, being a woman, and having a full-time position as the head athletic trainer. All participants met our criteria, which were purposeful, as the aim of the study was to better understand the career path of the female athletic trainer to becoming a head athletic trainer. The mean age of the participants was 45 ± 12 years, with 5 ± 1.5 years of experience in the role of head athletic trainer and 21 ± 10 years of experience as an athletic trainer. Only 1 female head athletic trainer was married with children, and all identified as white. The Table presents individual data for each participant.

Table.

Individual Head Female Athletic Trainer Demographic Information

| Participant |

Age, y |

Experience, y |

Marital Status |

| Carrie | 30 | 7 | Single |

| Calli | 56 | 32 | Partner, no children |

| Joslyn | 58 | 34 | Single |

| Jackie | 57 | 25 | Single |

| Kathy | 47 | 20 | Married, with children |

| Nikki | 33 | 10 | Married, no children |

| Riley | 51 | 25 | Single |

| Sarah | 31 | 12 | Single |

Procedure

We solicited the names and contact information from the NATA membership database of those members who were employed at the collegiate level, women, and identified as head athletic trainers (N = 216). The database did not distinguish among divisions; therefore, we sent an e-mail containing a link to a demographic survey via Survey Monkey (www.SurveyMonkey.com, LLC, Palo Alto, CA) to the contact list. Two weeks after our initial e-mail request, we sent a follow-up e-mail request to the contact list. Of the 216 e-mails sent, 140 head athletic trainers responded. Of those, 18 indicated they worked at the Division I level (Football Bowl Subdivision, Football Championship Subdivision, or non-football Division I). We then sent individual e-mails to those volunteers who identified working at the Division I level and had provided contact information for a follow-up interview. This e-mail explained the study purpose and asked for their participation. Those individuals who expressed an interest in participating were sent an informed consent form in a follow-up e-mail. Upon receipt of the form, a phone interview was scheduled and conducted by 1 of the first 2 authors (S.M.M., L.B.).

Ten women were contacted, and although initially all agreed to participate, only 8 were able to complete the interview process, for a final sample of 8. Data analysis was ongoing; thus, after completion of the eighth interview, data saturation was determined and solicitation of the remaining 2 participants was not necessary.31 For each interview, we followed a semistructured interview guide that we had drafted for our study. Interviews lasted approximately 45 minutes each and offered rich textual data regarding participants' professional experiences as athletic trainers and eventually as head athletic trainers. The researchers developed the interview guide based on existing literature specific to gender-role stereotyping and the experiences of women working within the collegiate setting (Appendix 1). Before data collection, a sport management educator and researcher, who was not an author but was knowledgeable on the topic of gender, reviewed the interview guide for content and clarity. We digitally recorded all interviews and had them transcribed verbatim immediately upon completion. All the participants were asked to select pseudonyms to ensure confidentiality. Participants were contacted to review the accuracy of their transcripts; those who were interested were e-mailed the transcript and allowed to make edits or corrections if necessary. Upon completion of the member check, data analysis was initiated.

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

Our analysis of the interview data followed 2 specific strategies: open-coding procedures32 and inductive analysis.33 Before analysis, 2 researchers met to discuss the coding strategy and then independently completed the process. Open coding took place in several stages.29 During the initial coding process, the researchers read the transcripts thoroughly to gain a holistic impression of the data. The second reading of the data included note taking in the margins of the transcripts. This preliminary coding consisted of segmenting information by assigning tags and labels to units of information in the transcripts. This process was guided by the use of NVivo software (version 10; QSR International Inc, Burlington, MA) to help manage the emerging themes generated by the open coding. We developed the open codes using the specific aim of the study, and once apparent themes materialized, we selected direct quotes from the participants' interviews to support each theme.

We established trustworthiness and credibility of the data through peer review, member checks, and multiple-analyst triangulation.34 As previously mentioned, our participants were afforded the chance to review their interview transcripts for accuracy. We also identified a colleague with knowledge of both qualitative methodology and gender-role stereotyping to serve as a peer reviewer for the development of the methods and interview guide. A second peer, not involved with the methods review but trained in qualitative analysis, helped verify the findings of the analysis. The peer reviewers challenged the data analysis to uncover any potential biases in data interpretation.34 The first peer reviewer also separately analyzed data and shared the findings with the researchers, who had completed independent reviews. After discussions with the peer reviewers, we finalized the results and themes.

RESULTS

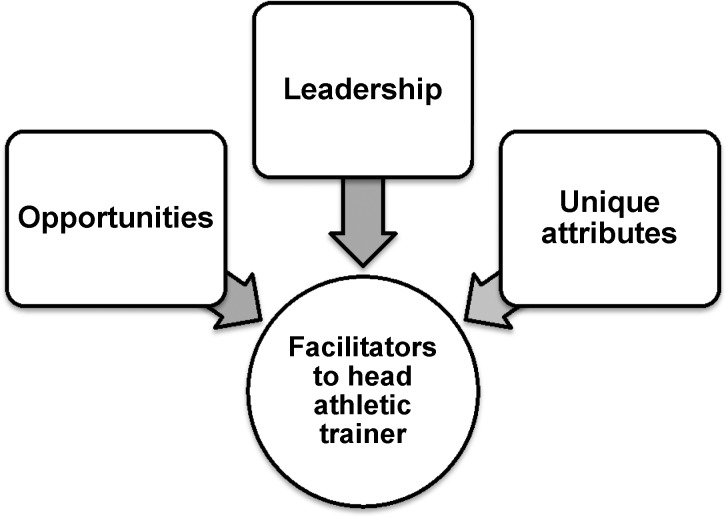

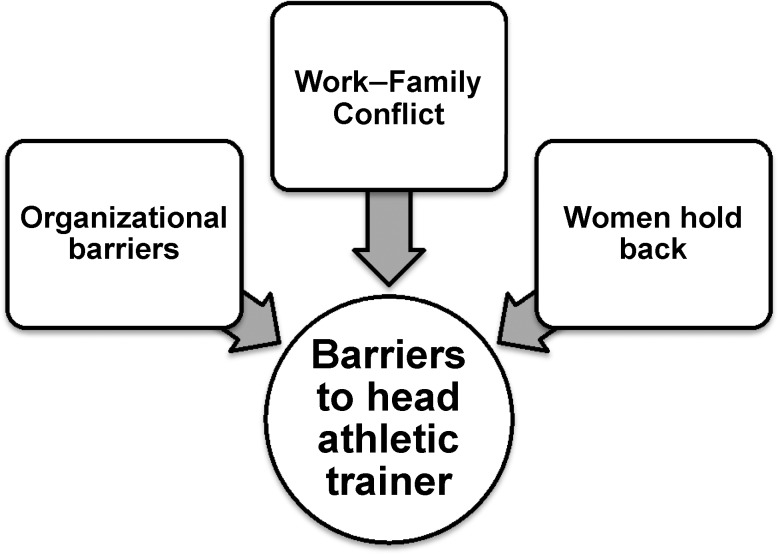

Our general inductive analysis revealed facilitators and barriers to becoming a head athletic trainer (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Facilitators for female athletic trainers (ATs) in becoming head ATs.

Figure 2.

Barriers for female athletic trainers (ATs) in becoming head ATs.

Opportunities to Become a Head Athletic Trainer

Many of our participants discussed beginning their careers as assistant athletic trainers for their respective institutions and through departure and promotion eventually attaining the role of head athletic trainer. For example, Riley shared her career progression, beginning with an assistantship:

I was able to go to grad[uate] school at [school name] and so I've been here since grad[uate] school. And so then I [graduated] from grad[uate] school, I was promoted to a 10-month assistant AT [athletic trainer], then to assistant women's [head]…the athletic department was divided then so it was a men's athletics and women's athletics. And so I was an assistant women's athletic trainer and then at, 2 years after that, I was the head women's athletic trainer and then when we got a new athletic director several years later. The AD [athletic director] combined [the departments] and at that point I was named Associate Director of Sports Medicine. So, I sat in that position for about 15 years. And then the director retired last year and then I was promoted to director.

Several participants were promoted to the position of head athletic trainer. Sarah described:

I was hired as an athletic trainer and then it just spawned from that position into the head athletic trainer. We had a head men's and head women's athletic trainer with 2 separate facilities. When [the male head athletic trainer] retired, I slid into the position and conjoined [sic] both facilities.

Networking was part of the dynamic for our participants as well as for those women investigated by Gorant3 for securing the role of head athletic trainer.

For our participants, opportunities to become a head athletic trainer also were manifested by their being in the right place at the right time. When the head athletic trainer position became available, the circumstances were favorable for them to transition into that new role. For example, Carrie was able to become the head athletic trainer when the existing head athletic trainer vacated the position; his departure allowed her to assume the position she currently holds. Carrie commented:

When I got here [school name], the head [athletic] trainer that was there before me, he had never been licensed in the state for 10 years. He had been practicing and never had been licensed. And somehow the state just got involved. So the university and this happened [approximately] in August, late August, so the university, they needed a 30-day interim position. I did the 30-day interim position and at [school name]…So I went through the 30-day interim position and in the meantime, they opened up the position.

Jackie experienced a similar role transition to that described by Carrie. Jackie was able to become the head athletic trainer at her current institution after succeeding the previous head athletic trainer, a man. Jackie described her transition as “being at the right place, at the right time.” She further described how she began as head athletic trainer:

I interviewed to be an assistant and when I got to [school name], I interviewed under a guy that was doing all the administrative work and was an athletic trainer for men's basketball. There were only 2 of us and we were not as competitive. So, we went on and I worked under the guy. He did everything: administrative, head trainer, etc. But we found out [through the change to] state licensure that … he didn't complete the necessary steps, and then we found out that he was not certified [to practice as an athletic trainer].

None of our participants acknowledged using a network of colleagues or mentors to obtain their positions. However, 2 participants noted that male administrators served as strong advocates for their placement in head athletic trainer positions within their current institutions. Both credited their male administrators with overcoming perceived stereotypes regarding women's abilities to serve in a leadership capacity. Sarah described this support: “My associate AD was telling the AD, ‘she can handle it. You are going to think that she's just the quiet white girl but believe me, she can handle it.'” Carrie noted the support of a senior male administrator:

I applied for it [head athletic trainer position], and the vice president for student affairs was also our director of athletics and he worked on the other side of campus. And I look at him as someone that kind of had the vision of the role of women not only in athletics, but our past 2 presidents of our university have been females and when it came to interviewing, the men's basketball coach and the baseball coach had said that we don't want a female. So I was lucky that I had a vice president that had the vision where gender was not an issue.

Having to rely on the support of male administrators to advocate for women in head athletic trainer positions can put female athletic trainers aspiring to those positions at a disadvantage. Kathy describes her role as a head athletic trainer:

I still think that there's that stereotype out there that…I don't know if [her university] would have hired me if we had a football team? I don't know…You sometimes wonder, those really male-dominated, testosterone-driven type of sports, would they be okay with a woman in charge?

Sarah stated that before she assumed her role as head athletic trainer, “I was told I was not allowed to do football because I was a female, but I was allowed to do men's soccer. Shrug your shoulders. Who knows what the difference is?”

Leadership

Most of our participants indicated that leadership was the most important characteristic contributing to their opportunities to be head athletic trainers. Jackie discussed her realization of her potential as a leader through her professional relationships:

What you will find out from me is that people are drawn to me. I worked with 1 person who was my head coach. She at one point looked at me and she goes, “You're a leader. Whether you choose to lead in a positive or negative way—that is up to you.” So, I had to figure out what she was saying to me. And it started the wheels turning, and I really had to embrace that, and I thought, “You know what, whether or not you see yourself as a leader, if people are drawn to you and they are looking to be led, you better lead them.”

Many of our participants identified themselves as leaders. As Nikki indicated, “I am a leader. I kind of have that leadership quality where I always want to do more and get more done and help people out.” She continued, “I grew up always playing sports, so I feel like I was a leader and mentor. So really there is that leadership piece, and I have always been a problem solver.”

The role of head athletic trainer also requires attention to detail, organization, and decision making. Kathy enjoyed those aspects of the role. “I liked the leadership power. I liked being in charge of the administrative stuff, setting the policies, and all of those kinds of things.” Like Kathy, Riley described herself as a leader and mentor and someone who “could implement change” in the role of the head athletic trainer.

Uniqueness

Our participants noted that something unique about them helped propel them to their head athletic trainer positions. For some, it was support from a mentor that identified this uniqueness. As Riley noted, “I had people tell me…like honestly, I really had no confidence, but then I had people telling me how great I would be [in the head athletic trainer position].” Riley's experiences illustrate the importance of encouragement and support from colleagues.

For others, an innate understanding of their perceived strengths allowed them to be undeterred from the head position, especially during times of challenge. Sarah described this persistence: “Just kept pushing, didn't know how to take ‘no.' You know, and I still don't take ‘no' well.” Sarah also explained the importance of being able to handle the administrative tasks that come with the head athletic trainer position (eg, negotiating with insurance companies, dealing with coaching concerns, solving problems) and how that was to her benefit, as she believed she was quite capable of fulfilling those tasks. While discussing her success in her head athletic trainer role, Sarah said: “I love being an athletic trainer and one of my strengths, I love paperwork. So I love like the administration side of it.”

Communication was also viewed as a key attribute that helped participants distinguish themselves from others and helped them navigate their roles successfully. Calli shared:

I think that I do a great job of …communicating with all of my coaches and administration so they always know what's going on, and I need to know what's going on, so communication with my athletic training staff.

Several other participants, including Kathy, Riley, and Joslyn, discussed the importance of communication in the role. Kathy articulated:

The other thing is the communication piece: the fact that there's open communication between you, the sports medicine staff, and the coaching staff… . There's obviously always the normal communication with your staff that you have, like staff meetings and that kind of stuff. I have one-on-one meetings with my staff quite regularly, and then it's just more of the nonwork stuff, just checking in, and that whole emotional intelligence thing.

Women Hold Back

Our participants perceived other female athletic trainers as hesitant to aspire to head athletic trainer positions. Joslyn noted:

I do think it's more and more women that are deciding not to pursue the position of head athletic trainer because they certainly don't want to do what it takes to be in that role. I think that a lot of times we get distracted because we are females and in this profession that we think we can't attain that. I think that women just lose focus and think that they're not ever going to have the chance.

Nikki mentioned the importance of mentoring young female athletic trainers so they do not hesitate to seek head athletic trainer positions at appropriate times in their careers: “I also think that we need to make sure women know that we can be strong, you know, strong females in a leadership position and do the right thing.”

Other participants commented that perhaps more insidious forces, including gender-role stereotyping, influenced the perception of why women held back from seeking head athletic trainer positions. Kathy described the perceptions of male administrators when considering women in leadership positions: “So people have these…whether a woman can handle it, ‘What is she going to be like?' ‘What's that time of the month?' thing, and all that kind of stuff.” As Riley stated, “Like, women aren't fighting it, you know. Because we all know the dirty little secret. If we cause any kind of ripples, we're not going to get a job.”

Perceived Work-Family Challenges

Many participants believed they were able to handle the demands of the head athletic trainer position because they did not have children. Sarah explained:

I think the fact that I'm still single is probably why I'm still pursuing some of what I do, because it, you know, some of it is my makeup, but some of it is also…it's, you know, I don't have a family that I have to go home to. I don't have to have dinners done at 6 or 7 o'clock. You know, I don't have anybody to pick up from daycare. I don't…you know, I just don't have those responsibilities.

Jackie discussed being “married” to her job and the need to have a partner who is supportive to help manage the demands faced by the athletic trainer and the head athletic trainer. She shared her perspective on women and the role of the head athletic trainer and the sacrifices she felt she had to make within her position as head athletic trainer:

Well, it is difficult to be married and have kids and I'm not one to ask because I haven't had kids and you can say I haven't been married. But all my assistants are and I watch them and we try to do life balance for them because I know that I've had failure in my life, even without kids, or a traditional marriage, that it is something that gets some of the best people out of the business.

Others discussed how the current structure of the position made it much more challenging for women and men with children to have a satisfying career and family life. As Nikki noted:

I probably once I start having kids and have a family I probably see myself going down to maybe the high school level as a head athletic trainer there or, as an assistant somewhere where the workload isn't quite as much.

Nikki's comments reflect the perception that some women may favor a more family-centered lifestyle that allows them to spend equal or more time with their families and children.19

Jackie also perceived that having a family was a significant reason many female athletic trainers did not pursue head athletic trainer positions: “It's a balancing act and they may decide to walk away from being a head athletic trainer because their family's more important and supporting their husband is more important.” Nikki also highlighted the role that family can play in an athletic trainer's career planning because of the demands and time required of a head athletic trainer. Nikki, who is married without children, said as she was reflecting on the future:

That was a concern of mine [having children]. I feel like as women, sometimes, we feel that pull of having a family, wanting to start a family, you know, taking care of a family, kids versus sometimes the hours that you want to put into the job.

Joslyn discussed the influence of family obligations on climbing the administrative ladder, specifically the additional challenges of balancing those family obligations women face when deciding to take on the role of the head athletic trainer. She shared:

Just for example, I have a full staff of 9 certified athletic trainers that work for me. None of them want my chair. Not one. If I were to leave, which will happen, none of them are in a position that they want to sit at that seat. I think they're smart. They are women that have a—they want something different in their life. They want a better balance. They want to accomplish a balance in life, and I think many of them look at those that are in these positions and think that they cannot accomplish that. So they themselves leave.

Other participants felt that women were passed over for head athletic trainer positions because male administrators believed that family and motherhood would hinder their ability to handle the duties of the position. The 1 participant in our study who was a mother noted that her situation was unique, as her husband was able to take on the role of primary caregiver, which she believed allowed her the opportunity to fulfill the role of head athletic trainer. As Kathy noted,

Our roles are a bit reversed in that sense, that he [her husband] is able to be there and be that stable caregiver for our children when mom is away. Unfortunately, I think there are some people that don't have that situation.

Organizational Barriers

Speaking to the issue of the “good ol' boys' club,” Calli explained, “The number of females [in head athletic trainer roles] might be low just because in some ways it seems to be like a good ol' boys' network, and it might be hard for women to break into that role.” Riley also stated, “Administrators were men. Men, they just keep promoting men in all athletics. As the money and salaries go up, the men were getting those position[s], and they just kept helping each other.” Riley commented that changes were occurring at the organizational level, saying, “But now, I do think society and culture [has] changed. Now it is the best person for the job, and it is not gender specific.” Calli had a different perspective, that with men in the majority of senior athletic administration positions (ADs), there was reluctance to place women in leadership positions in athletic training:

But I feel like sometimes they [male ADs] just aren't willing to break out of what they already know. Sometimes…like I found it was, “Well, this is what we've always done, this is what we've always known,” you know?”

Our participants were frustrated when considering why so few women were in head athletic trainer positions, as Joslyn described:

I certainly do not feel that it's not because women are not qualified to be in these positions. I don't really know that I know the answer. I mean it's frustrating for me—the statistics are clearly inequitable. They are clearly unfair and there would be no reason with the qualified, female athletic trainers that there are not a greater percentage of women in these positions.

Calli noted: “Just when you look at anybody, especially in the college level. You look at the females, and it seems like the men here have a little easier go at things than we do.”

Some of our participants noted their struggles to gain the respect of peers and administrators, indicating they thought they had to fight harder than their male colleagues to receive the resources needed to perform their jobs. For instance, Carrie expressed:

You can get some of these funny stories. We hire a new swim coach, and I walk into the swim coach's office to welcome him to the university, and on his desk, I see a computer, a brand-new computer. And I'm like, “Did you just get that?” And he goes, “Yeah.” And I had been asking for a computer, not a new one, a computer, for a long time.

Sarah was blunter in her assessment of the organizational constraints women face:

I still think that there's a good ol' boys' club, and being a female, you will never get invited to that club. It doesn't matter how good you are, your pedigree, how great a job performance you have. You're never going to be one of the guys.

These social barriers were significant in that they prevented our participants from gaining the social capital necessary to gain respect from coworkers, as well as access to needed resources from their departments.35 Sarah continued:

I have to make sure I speak to that person, you know, after being in front of their face and between that 7 am to 6 pm window, or whenever that athletic trainer is available, and everything that I do has to, I feel like, has to be documented. Whereas, if I'm one of the boys, oh yeah man, we talked about that last night. You're good, no problem, don't worry about it. I got you. I don't have that relationship.

However, Jackie and Joslyn had different perspectives regarding the constraints women face in obtaining positions as head athletic trainers. Years earlier, those constraints might have been related to gender, but there has been a transition away from organizational barriers to more personal barriers. Joslyn said, “The emphasis is that we are not successful as women because we are not given the chance. That was just never my case.”

DISCUSSION

Opportunities to Become a Head Athletic Trainer

Opportunities for our participants to become head athletic trainers were gained through persistence within their roles in the athletic and sports medicine departments. Our findings contrast with those of previous researchers,36 who found that women departed the clinical setting at an early age, before they were able to gain enough experience to be prepared and trained to handle the responsibilities of the head athletic trainer. Our results support those of Gorant,3 who also observed that many of the female head athletic trainers in her study were promoted from within or hired because of a previous connection to the institution.

Only 1 of our participants intentionally applied and interviewed for her position at an institution where she was not currently employed. This demonstrates that women seeking leadership positions in athletic training may not follow the more traditional route of serving as assistants at different universities and subsequently applying for head athletic trainer positions at other institutions. The majority of our participants, though clearly deserving of their positions, seemed to have been in the right place at the right time, in addition to persisting in their positions. This route to a leadership position can be disadvantageous for large numbers of women who seek to lead intercollegiate sports medicine departments. The career path for the female head athletic trainer is more opportunistic, with limited strategizing on the part of women to reach a leadership position.3 Similar to women advancing in leadership positions within education, most of our participants were provided opportunities to advance from within their current positions.21,37 Though no data are available to fully describe how men are reaching head athletic trainer positions, it is noteworthy that only 1 of our 8 participants applied for and was hired for the head athletic trainer position while working as an assistant at another university. In addition, none of our participants acknowledged using a network of colleagues or mentors to obtain their positions. Our finding is similar to findings within athletic administration, as men appear to have an advantage with regard to using social capital (ie, networks, supportive mentors) to advance to leadership positions when compared with women.38

Having to rely on the support of male administrators to advocate for head athletic trainer positions can put female athletic trainers aspiring to those positions at a disadvantage. As our participants discussed, negative perceptions regarding women's abilities to lead (eg, being strong enough to lead) athletic training programs and hold such positions are pervasive in intercollegiate athletics and within sports medicine departments.6,9 Only 2 participants in our study were head athletic trainers at Football Bowl Subdivision universities. Moreover, none of our participants provided athletic training services directly to the football student-athletes at their respective institutions. Several participants noted the challenge of leading athletic training departments with football teams, despite not providing athletic training services for the football team. Gorant3 cited balancing the roles of football coverage and head athletic trainer as a barrier for women seeking the position of head athletic trainer. Interestingly, neither our cohort nor those women in the Gorant3 study were currently providing athletic training services to the football team or had the sport of football at their universities. This is a consideration that should be investigated in the future, as male head athletic trainers typically provide athletic training services to their institutions' football teams.

Leadership

The possession of a strong work ethic and self-confidence are characteristics associated with women who hold the position of head athletic trainer.3 Dually important for the head athletic trainer is the demonstration of leadership behaviors (eg, being encouraging, enabling, communicative, proactive).3,39 Consistent with previous research on administrative and leadership roles in athletic training,3,40 our participants discussed many qualities and attributes they perceive to have helped them obtain and succeed in their role as a head athletic trainer. Athletic training leaders are often promoted to their positions because of their demonstration of practiced leadership skills and behaviors.39 Our findings contrast with those of Gorant,3 whose participants indicated a reluctance to lead primarily due to a lack of confidence in leadership and decision-making skills. Our participants believed they possessed the leadership qualities that provided them with the confidence to assume the role and make the decisions that are necessary of the head athletic trainer.

The role of head athletic trainer also requires attention to detail, organization, and making decisions. Many of our participants self-identified as leaders, individuals who liked to be in charge, complete the administrative tasks associated with the role of the head athletic trainer, and make decisions. Our results vary to some degree from those reported by Gorant3: her participants were reluctant to assume leadership roles but were convinced to assume those roles based on external support provided by mentors and senior administrators.

Uniqueness

Several of our participants' experiences illustrate the importance of encouragement and support from others. Gorant3 found that her participants did not actively pursue the position of head athletic trainer, but when someone within the organization encouraged them to pursue it, they became interested and motivated to transition. Moreover, Eddy and Cox21 showed that mentors were crucial for women to climb the administrative ladder. Receiving and accepting encouragement and support from others has been recognized as important in assisting women to climb the administrative ladder21,41 and helps to explain how some of our participants were able to transition to the role of head athletic trainer.

Several of our female head athletic trainers demonstrated similar characteristics to those participants in Gorant's study,3 such as a strong work ethic, communication skills, and ability to multitask. Interestingly, communication skills were reported as helpful in reducing possible experiences of gender bias or discrimination for female athletic trainers navigating the Division I work setting.9 For our participants, communication skills also helped them to manage and lead others in their sports medicine departments.

Women Hold Back

Our participants also discussed their concerns with the self-imposed limitations demonstrated by other female athletic trainers.3 They perceived other female athletic trainers as hesitant to aspire to head athletic trainer positions. Some participants did not believe there were barriers to women's ascension to head athletic trainer positions. This finding supports previous work41 indicating that women's career aspirations can be negatively influenced by implicit stereotypes they may hold about nontraditional female careers (eg, head athletic trainer).

In addition, young women reported reduced aspirations for leadership positions when exposed to gender stereotypes.42 Considering the gender stereotypes female athletic trainers are exposed to early in their careers,9 these stereotypes may lead to decreased aspirations for head athletic trainer positions later in their careers. Ohkubo13 noted that gender-role stereotyping can contribute to fewer female athletic trainers assuming leadership roles, which is likely influenced by the perception that male athletic trainers are able to work in and navigate the expectations and bureaucracy of the collegiate setting more easily than female athletic trainers. Our participants acknowledged that stereotypes of women as leaders can lead to perceptions that female athletic trainers do not have the competence and skills necessary to be head athletic trainers.9

Perceived Work-Family Challenges

Work-life imbalance is a major concern for athletic trainers, especially those working in the Division I setting.43 In fact, life-balancing concerns have been cited as a departure factor for female athletic trainers working in this setting, chiefly because of the demands that limit the time to be a parent.10,36 Balancing a career and a family was perceived as a barrier to more women assuming the role of the head athletic trainer. It is important to note that only 1 of our participants had children, in contrast to the study by Gorant,3 who interviewed 7 head female athletic trainers, of whom 3 were married with children.

Nikki's comments reflect the perception that some women may favor a more family-centered lifestyle that allows them to spend equal or more time with their families and children.19 In a recent study conducted by Mazerolle and Gavin,15 female athletic training students discussed wanting an employment setting that was considered family friendly, which many believed was not possible at the Division I setting. The perception that women favor a home- or family-oriented lifestyle was supported by several of our participants, who indicated that women would have a stronger desire to want to be with children, which would result in fewer women seeking head athletic trainer positions. In addition, our participants believed that gendered norms (ie, what is expected of women) would contribute to feelings of guilt if women did not devote the majority of their time to their children and to family obligations.

Our findings suggest that some female athletic trainers may prefer an adaptive lifestyle, described by Hakim19 as one that values both work and home and having a balance between them. The inability to achieve this adaptive lifestyle can also help to explain why many female athletic trainers may not aspire to the role of head athletic trainer. It may also be the result of seeing so few women who were married with children obtain positions of leadership within athletic training. Given this lack of role models, younger female athletic trainers may not perceive that it is possible to fulfill the roles of parent and head athletic trainer.

The role of the spouse has often been cited as instrumental in allowing the athletic trainer to find work-life balance43,44; however, it is often the wife who is mentioned as the spousal support and not the husband. Female athletic trainers who are succeeding at the Division I level, however, have attributed support and understanding from their spouses as helpful and necessary for retention in the workplace as athletic trainers.20

Organizational Barriers

Several participants identified the good ol' boys' network as a factor limiting the number of women in the role of the head athletic trainer in the Division I setting.39,46,47 Similar findings regarding barriers to leadership in intercollegiate athletic administration have indicated that homologous reproduction, the tendency for individuals to advance similar individuals to leadership positions (eg, male athletic directors hiring male athletic trainers), may partially account for the lack of women in senior leadership positions.47 The limited number of women in leadership roles was troubling for our participants. Ohkubo13 reported concerns about gender equity and the ease with which male athletic trainers are able to work in and navigate the expectations and bureaucracy of the collegiate setting.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study is not without limitations. With only 2 exceptions, our female head athletic trainers were employed by universities that did not have football teams, which could limit the transferability of the findings to female athletic trainers at universities with football teams. Although our findings are similar to those of Gorant,3 who interviewed 8 female athletic trainers at schools with football teams, we cannot assume that those female head athletic trainers had similar experiences or perceptions. Future researchers should secure an equal representation of female head athletic trainers at both Football Championship Subdivision and Football Bowl Subdivision schools and schools without football teams. The challenges of working long hours and spending time away from family appeared to be concerns for several participants and were also perceived as a reason why more women do not seek head athletic trainer positions in the Division I setting. Future investigators can assess if more women pursue head athletic trainer positions at Division II or III universities over Division I. Also, future authors should explore the application of the Hakim19 preference theory to examine the experiences of female athletic trainers in the collegiate setting and whether this theoretical framework can assist in providing a greater understanding of why so few women are in head athletic trainer positions at the Division I level. We recognize that the majority of the participants in our study did not have children. Thus, future studies should address the experiences of women who have children while navigating the role of the head athletic trainer. Future researchers should also make efforts to understand the experiences of women who are married and married with children and are currently in the role of the head athletic trainer or who have aspirations to become head athletic trainers.

CONCLUSIONS

Female athletic trainers have made great strides in career advancements, yet only a limited number have assumed leadership and administrative positions, including the position of head athletic trainer. Our findings suggest that strong job performance and persistence in the role of an athletic trainer at one's institution can lead to promotion to the head athletic trainer position for a woman. Our participants did not seek head athletic trainer positions outside their current institutions, nor were they asked to apply for head athletic trainer positions at other institutions. More opportunities were available for our participants to rise to the position of head athletic trainer when athletic administrators (ie, athletic directors) were familiar with their work. This finding has potentially negative implications for female athletic trainers, as they may be limited in their potential opportunities. Within the hiring process for head athletic training positions, college and university hiring committees should recruit female athletic trainers at the assistant level from other institutions. Leadership, dedication, communication, and time-management skills are necessary to be successful in the position of head athletic trainer; leadership training should be emphasized in athletic training education programs, and mentors working with young female athletic trainers should also emphasize the importance of leadership skills. Organizational barriers do appear to exist for female athletic trainers who aspire to assume administrative or leadership roles. Our participants discussed the good ol' boys' club and gender stereotyping as primary organizational constraints for women seeking head athletic trainer positions. Again, an emphasis on recruiting more women for head athletic trainer positions and educating athletic trainers at all levels of the profession about the impact of stereotypes on women's advancement in the field of athletic training is of critical importance. Finally, the balance between work, home, and personal obligations influenced our participants' decisions to assume the role of the head athletic trainer. Those working in leadership positions in athletic training must continue to recognize how to develop work environments that support balancing work and family responsibilities for all athletic trainers. As Pitney28 indicated, having strong mentors can help the athletic trainer navigate the bureaucracy associated with intercollegiate athletics.

Appendix

Interview Guide: Female Head Athletic Trainers

1. Can you explain and describe how you got to your current position, starting with your education and all the jobs you have held since then until now?

- 2. Why did you pursue the position of head athletic trainer?

- a. Before you became a head athletic trainer, did you envision yourself as a head athletic trainer? If yes, why? If not, why not?

- b. What experiences prepared you for your role of head athletic trainer?

- c. Have there been people in your life that have helped you reach the position of head athletic trainer? (can ask how, inquire about mentorship)

3. What challenges have you faced in the pursuit of your career goals?

4. What challenges have you faced in your position as a head athletic trainer?

5. Why do you think the numbers are low? Or why do you think the percentages are not more equitable concerning male vs female?

6. What advice would you give to female athletic trainers who have aspirations to pursue the head athletic trainer position?

7. What factors do you believe influence an athletic trainer's pursuit of the role of head athletic trainer? Do you think these factors are different based on gender?

8. In your opinion why are there a limited a number of female athletic trainers in the position of head athletic trainer at the Division I level?

- 9. What changes do you think need to be made to increase the number of women in head athletic trainer positions at the Division I level?

- a. If they put the blame on individual motivation to not go after these positions: What changes need to be made on an organizational level to encourage more women to pursue these jobs?

- b. If the head athletic trainer seems to think that the head athletic trainer is a gendered position: How can athletic administrators influence this gendering practice?

REFERENCES

- 1.Acosta RV, Carpenter LJ. A longitudinal, national study: thirty-five year update—1977–2012. Women in Intercollegiate Sport Web site. http://www.acostacarpenter.org. Updated January 28, 2012. Accessed January 7, 2014.

- 2.Irick E. 2009–2010 race and gender demographics—member institutions report. NCAA Publications Web site. 2014. http://ncaapublications.com/p-4220-2009-2010-race-and-gender-demographics-member-institutions-report.aspx. Accessed January 7.

- 3.Gorant J. Kalamazoo: Western Michigan University;; 2012. Female Head Athletic Trainers in NCAA Division I (IA Football) Athletics: How They Made it to the Top. dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burton LJ, Grappendorf H, Henderson A. Perceptions of gender in athletic administration: utilizing role congruity to examine (potential) prejudice against women. J Sport Manag. 2011;25(1):36–45. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claringbould I, Knoppers A. Paradoxical practices of gender in sport-related organizations. J Sport Manag. 2012;26(5):404–416. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schull V, Shaw S, Kihl LA. “If a woman came in… she would have been eaten up alive”: analyzing gendered political processes in the search for an athletic director. Gend Soc. 2013;27(1):56–81. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramarae C. The Third Shift: Women Learning Online. Washington, DC: American Association of University Women Educational Foundation;; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharratt G, Derrington ML. Female superintendents: attributes that attract and barriers that discourage their successful applications. Manag Inf. 1993;13(1):6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton LJ, Mazerolle SM, Borland JF. They cannot seem to get past the gender issue: experiences of young female athletic trainers in NCAA division I intercollegiate athletics. Sport Manag Rev. 2012;15(3):304–317. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodman A, Mensch JM, Jay M, French KE, Mitchell MF, Fritz SL. Retention and attrition factors for female certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Football Bowl Subdivision setting. J Athl Train. 2010;45(3):287–298. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahanov L, Loebsack AR, Masucci MA, Roberts J. Perspectives on parenthood and working of female athletic trainers in the secondary school and collegiate settings. J Athl Train. 2010;45(5):459–466. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.5.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ. Work-family conflict, part I: antecedents of work-family conflict in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):505–512. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohkubo M. Female Intercollegiate Athletic Trainers' Experiences with Gender Stereotypes [master's thesis] San Jose, CA: San Jose State University;; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. Athletic trainers with children: finding balance in the collegiate practice setting. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2011;16(3):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazerolle SM, Gavin K. Female athletic training students' perceptions of motherhood and retention in athletic training. J Athl Train. 2013;48(5):678–684. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.3.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barron LA. Ask and you shall receive? Gender differences in negotiators' beliefs about requests for a higher salary. Hum Relat. 2003;56(6):635–662. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Compton SS. Salary Negotiation Strategies of Female Administrators in Higher Education [dissertation] Kalamazoo: Western Michigan University;; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tannen D. You Just Don't Understand: Women and Men in Communication. New York, NY: William Morrow;; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hakim C. Work-Lifestyle Choices in the 21st Century: Preference Theory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press;; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. Fulfillment of work–life balance from the organizational perspective: a case study. J Athl Train. 2013;48(5):668–677. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.3.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eddy PL, Cox EM. Gendered leadership: an organizational perspective. New Dir Community Coll. 2008;2008(142):69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eagly AH, Carli LL. The female leadership advantage: an evaluation of the evidence. Leadership Q. 2003;14(6):807–834. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stubbe AF. The Community College Presidency in the New Millennium: Gender Differences in Leadership Preparation [dissertation] Ames: Iowa State University;; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pitney WA. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in high school settings: a grounded theory investigation. J Athl Train. 2002;37(3):286–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pitney WA, Ilsley P, Rintala J. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I context. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazerolle SM, Dawson A, Lazar R. Career intentions of female athletic training students. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2012;17(6):19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eason CM, Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. Motherhood and work–life balance in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting: mentors and the female athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2014;49(4):532–539. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitney WA. Organizational influences and quality-of-life issues during the professional socialization of certified athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):189–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson DR. The importance of mentoring programs to women's career advancement in biotechnology. J Career Dev. 2005;32(1):60–73. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maxwell JA. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications;; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Straus AC, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications;; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications;; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitney WA, Parker J. Qualitative Research in Physical Activity and the Health Professions. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics;; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications;; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amis J. The art of interviewing for case study research. In: Andrews DL, DS Mason, Silk ML, editors. Qualitative Methods in Sports Studies. New York, NY: Berg Publishers;; 2005. pp. 104–138. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ely R, Padavic I. A feminist analysis of organizational research on sex differences. Acad Manage Rev. 2007;32(4):1121–1143. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kahanov L, Eberman LE. Age, sex, and setting factors and labor force in athletic training. J Athl Train. 2011;46(4):424–430. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.4.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doherty L, Manfredi S. Women's progression to senior positions in English universities. Employee Relat. 2006;28(6):553–572. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sagas M, Cunningham GB. Does having “the right stuff” matter? Gender differences in the determinants of career success among intercollegiate athletic administrators. Sex Roles. 2004;50(5–6):411–421. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laurent TG, Bradney DA. Leadership behaviors of athletic training leaders compared with leaders in other fields. J Athl Train. 2007;42(1):120–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malasarn R, Bloom GA, Crumpton R. The development of expert male National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eagly AH, Carli LL. Through the Labyrinth: The Truth About How Women Become Leaders. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press;; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davies PG, Spencer SJ, Steele CM. Clearing the air: identity safety moderates the effects of stereotype threat on women's leadership aspirations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88(2):276–287. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Casa DJ, Pagnotta KD. Assessing strategies to manage work and life balance of athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):194–205. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Goodman A. Strategies for athletic trainers to find a balanced lifestyle across clinical settings. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2012;17(3):7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoffman JL. The old boys' network: women candidates and the athletic director search among NCAA Division I programs. J Study Sports Athletes Educ. 2011;5(1):9–28. [Google Scholar]