Abstract

Patient: Male, 47

Final Diagnosis: Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

Symptoms: Nephrotic syndrome

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Renal biopsy

Specialty: Nephrology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Visceral leishmaniasis is an important opportunistic disease in HIV-positive patients. The information available on the effects of such co-infection in the kidney is limited. We describe a patient with HIV/leishmania coinfection who developed nephrotic syndrome and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. As far as we know, only 2 cases of this nephropathy in HIV/leishmania coinfection have been reported.

Case Report:

A 47-year-old man developed nephrotic syndrome. He had been diagnosed with HIV infection and visceral leishmaniasis and was treated with antiretroviral therapy, antimonial compounds, liposomal amphotericin B and miltefosine, but the leishmania followed a relapsing course.

Renal biopsy disclosed membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis and leishmania amastigotes were seen within glomerular capillary lumens. He was given miltefosine and liposomal amphotericin B but the leishmaniasis persisted. Stage 3B chronic renal disease and nephrotic range proteinuria tend to become stable by 15-month follow-up.

Conclusions:

Our case illustrated some aspects of leishmaniasis in HIV patients: its relapsing course, the difficulties in therapy, and the renal involvement.

MeSH Keywords: Glomerulonephritis, Membranoproliferative, HIV, Leishmania, Nephrotic Syndrome

Background

Many types of glomerulonephritis may appear in HIV patients, such as collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, immune-complex glomerulonephritides, and thrombotic microangiopathy. Immune-complex glomerulonephritides include those associated with HIV (HIV RNA usually over 400 copies/mL), and other types of infectious glomerulonephritis [1].

Leishmaniasis is an important opportunistic infection in HIV, and visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is the most common clinical form.

Renal involvement by leishmania has been well documented in immunocompetent subjects, but in HIV patients the information available is limited [2–9]. We describe an HIV patient with nephrotic syndrome and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) associated with VL.

Case Report

A 47-year-old man was admitted for lower-extremity edema of about 3–4 weeks evolution and proteinuria. He had presented hypertension for the previous 18 months, which had been treated with a thiazide and an angiotensin receptor blocker.

He had been diagnosed with HIV infection Stage C3 at another hospital in October 1999 and received antiretroviral treatment. In November 2002 he was diagnosed with VL and treated with antimonials. He was referred to our hospital in October 2004; the patient had ceased receiving the antiretroviral treatment and was asymptomatic, except for nodular skin lesions on the trunk and extremities. A skin biopsy and bone marrow aspiration revealed leishmania, which was treated with antiretrovirals and antimonials. There were several recurrences of leishmaniasis (cutaneous lesions and cytopenias) in the following years, and the patient received liposomal amphotericin B and miltefosine as treatment and prophylaxis.

Physical examination on the current admission to hospital (June 2012) revealed blood pressure 130/80 mm Hg, no fever, edema in the legs up to the knees; other results were normal. The laboratory examinations showed fibrinogen 7.88 g/L, hemoglobin 85 g/L, leukocytes 1.78×109/L, CD4 count 93/μL, platelets 110×109/L, urea 12.5 mmol/L, creatinine 123.76 μmol/L, albumin 19 g/L, GGT 83 U/L, and C-reactive protein 16.7 mg/L; electrolytes, other coagulation parameters, and routine biochemistry results were normal. The following results were normal/negative: immunoglobulins, RF, C3, C4, ANA, anti-DNA, anti-GBM, ANCA, cryoglobulins, and anti-TPO. The blood/urine study for monoclonal proteins was negative. The 24-hour proteinuria was 8 g (high-resolution electrophoresis: non-selective glomerular pattern) and the urine sediment analysis showed 40–60 RBC/HPF. The result of a urine culture was negative. Serology for hepatitis B and C, and HIV RNA PCR and RPR results were negative.

The chest x-ray and ECG findings were normal. Abdominal ultrasound revealed mild splenomegaly and normal kidney size, with increased cortical echogenicity. Bone marrow aspiration showed abundant intra- and extracellular leishmania.

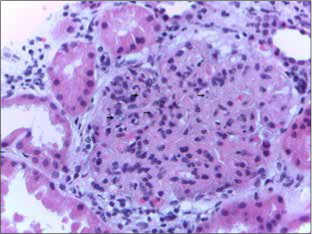

RBCs were transfused, desmopressin was administered, and percutaneous renal biopsy was performed with no technical difficulties (3 needle passes with 3 tissue cores). The glomeruli (9) were of lobular appearance, with diffuse mesangial proliferation and thickened capillary walls with double contours. Leishmania amastigotes were identified in the glomeruli (Figure 1), there were calcium deposits in the interstitium, and the vessels were normal. Immunofluorescence showed mesangial deposits of C3 (+++) and C1q (++); IgG, IgA, IgM, C4, kappa and lambda were negative. These findings were consistent with MPGN.

Figure 1.

Glomerulus showing lobulation of the capillary tuft, mesangial hypercellularity, and thickening of the capillary walls. Leishmania amastigotes are seen within capillary lumens (arrows). HE ×400.

After the biopsy, the patient presented severe pain in the left lumbar fossa. The CT showed a large left perirenal hematoma; the angiography revealed no bleeding point. RBCs were transfused, tranexamic acid was administered, and the subsequent evolution was positive. The patient was discharged with symptomatic treatment, antiretroviral therapy, interferon-gamma, and Glucantime. He was readmitted a week later with multi-organ dysfunction with involvement of the kidneys (creatinine 654.16 μmol/L), liver, and pancreas; blood cultures and urine culture were negative. Interferon-gamma and/or Glucantime toxicity was considered probable, and was treated with supportive measures and hemodialysis; evolution was satisfactory and renal function improved to a creatinine level of 143.20 μmol/L.

During the subsequent 15 months of follow-up, creatinine remained at 167.96–176.8 μmol/L, proteinuria at 4–6 g/24 hours with normal albumin, CD4 count at 100/μL, HIV RNA at <50 copies/mL, and PCR for leishmania in the blood was positive. The patient was treated with angiotensin receptor blocker, nifedipine GITS, darbepoetin, allopurinol, omeprazole, oral iron and vitamins, antiretroviral therapy, miltefosine, and liposomal amphotericin B every 15 days.

Discussion

VL in HIV patients is a relapsing disorder characterized by a low cure rate, increased toxicity of anti-leishmania drugs, and the parasite’s location in unusual places such as the kidney [5,9]; these characteristics were apparent in this patient.

Leishmania and HIV affect similar immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells and have a synergistic effect. Leishmania facilitates the replication and progression of HIV and the virus contributes to the development of VL [10,11]. Both leishmania and HIV alter the Th1/Th2 balance in favor of Th2, and this response facilitates the progression of the parasite [11]. Moreover, leishmania induces chronic activation of the immune system, despite the simultaneous immunosuppression against its antigens, which causes chronic depletion of CD4 T cells and progression of the virus [11,12]. Even in patients like ours, who are receiving antiretroviral treatment and have a low HIV RNA load, there is immune failure that prevents the elimination of leishmania [13].

Glomerulopathy in VL has been associated with immune complex deposition, dependent on the polyclonal activation of B lymphocytes by the parasite. However, studies in animals and humans suggest that other components of the immune system – macrophages, T cells, and cytokines – in some cases play a greater role than immune complexes [12]. Leishmania may also be found in the kidney and cause direct local damage [3]. Besides, secondary bacterial skin infection is a frequent complication of cutaneous leishmaniasis. In such cases, the contribution of the bacterial superinfection in the pathogenesis of the glomerulopathy is unclear [14].

Table 1 shows the cases reported, with details of nephropathy, VL, and HIV. The common findings are CD4 count under 200/μL and an undetectable or positive low-titer HIV RNA. In this patient, the VL was apparent long before the diagnosis of MPGN, but the nephropathy may also be the first manifestation of VL in the HIV infection [2].

Table 1.

Nephropathy in patients with VL/HIV coinfection.

| Authors | Gender/age | CD4 μL | HIV RNA c/ml | Pathology | Clinical manifestations | Leishmania in renal biopsy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clevenbergh et al. | M/45 | 60 | < 200 | mesangial hypertrophy, segmental sclerohyalinosis | ARF, subnephrotic proteinuria | No | Normalization of renal function |

| Rollino et al. | F/28 | n.a. | n.a. | focal segmental sclerosis, acute tubulitis, tubular necrosis, vasculitis | ARF | Yes | death |

| Navarro et al. | M/28 | 62 | <80 | AA amyloidosis | ARF, NS | No | HD |

| Alexandru et al. | F/42 | 344 | Undetectable | mesangial hyperplasia | NS | Yes | Death |

| de Vallière et al. | M/32 | 160–170 | Undetectable | AA amyloidosis | ARF, NS | No | CRF; NS |

| Rybniker et al. | M/49 | 180–200 | Undetectable | extracapillary glomerulonephritis | ARF | No | HD |

| Suankratay et al. | M/37 | 129 | Undetectable | membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, focal segmental sclerosis | ARF, NS | No | Improvement |

| Amann et al. | M/45 | 174 | 790 | membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis | ARF, NS | Yes | CRF; NS |

| Present case | M/47 | 93 | Undetectable | membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis | NS | Yes | CRF; NP |

M – male; F – female; n.a. – not avalaible; ARF – acute renal failure; NS – nephrotic syndrome; HD – hemodialysis; CRF – chronic renal failure; NP – nephrotic proteinuria.

In this case, the renal biopsy showed MPGN with mesangial deposits of C3 and C1q. In our patient, negativity for HIV RNA and other parameters (cryoglobulins, hepatitis C and B viruses, monoclonal proteins) and the existence of VL suggest that the latter was linked to the glomerulopathy. The predominance of C3 would suggest a C3 glomerulopathy. However, the presence of dominant or codominant C3 is not uncommon in infectious glomerulonephritis and C1q was also present only in 1 order of magnitude less than C3 [15]. Electron microscopy study would have been helpful, but could not be performed. Moreover, MPGN has been shown to be capable of evolving from a predominance of IgG to a predominance of C3 [16]. However, there remains the possibility that leishmania triggers C3 glomerulopathy in subjects with genetic alterations in the alternative complement pathway.

Two other cases of MPGN, VL, and HIV, in addition to the present one, have been reported. One of them was also affected with the hepatitis C virus, although neither the cryoglobulins nor the immunofluorescence were specified [8]; in the other, hepatitis C and cryoglobulins were negative and the immunofluorescence showed IgG and C3 [9].

The treatment of nephropathy associated with VL in HIV infection is the same as for leishmania. Even if the leishmania is counteracted, the evolution of the nephropathy may be negative [4]. Corticosteroids have been used in immunocompetent patients [17], but to the best of our knowledge, not in cases with HIV coinfection.

Renal biopsy is important for establishing a diagnosis but is of limited therapeutic use in patients with glomerulopathy and HIV/leishmania coinfection. Furthermore, there is an increased risk of hemorrhagic complications in VL, as we found in this case.

Conclusions

In conclusion, VL in HIV infection is a relapsing disease, with difficult therapeutic approach; renal involvement increases the morbidity and mortality of this condition. This case report stresses these important aspects of great relevance in clinical practice.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests concerning the publication of this paper.

References:

- 1.Atta MG, Stokes MB. ASN clinical pathological conference. Tenofovir-related ATN (severe) Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:882–90. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11781112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clevenbergh P, Okome MN, Benoit S, et al. Acute renal failure as initial presentation of visceral leishmaniasis in an HIV-1-infected patient. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34:546–47. doi: 10.1080/003655402320208857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rollino C, Bellis D, Beltrame G, et al. Acute renal failure in leishmaniasis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1950–51. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navarro M, Bonet J, Bonal J, Romero R. [Secondary amyloidosis with irreversible acute renal failure caused by visceral leishmaniasis in a patient with AIDS] Nefrologia. 2006;26:745–46. [in Spanish] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexandru S, Criado C, Fernández-Guerrero ML, et al. Nephrotic syndrome complicating chronic visceral leishmaniasis: re-emergence in patients with AIDS. Clin Nephrol. 2008;70:65–68. doi: 10.5414/cnp70065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Vallière S, Mary C, Joneberg JE, et al. AA-amyloidosis caused by visceral leishmaniasis in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:209–12. Erratum in: Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2009; 81: 732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rybniker J, Goede V, Mertens J, et al. Treatment of visceral leishmaniasis with intravenous pentamidine and oral fluconazole in an HIV-positive patient with chronic renal failure – a case report and brief review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e522–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suankratay C, Suwanpimolkul G, Wilde H, Siriyasatien P. Autochthonous visceral leishmaniasis in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patient: the first in thailand and review of the literature. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:4–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amann K, Bogdan C, Harrer T, Rech J. Renal leishmaniasis as unusual cause of nephrotic syndrome in an HIV patient. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:586–90. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011050472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Standaert D, Laurent F, Jonckheere S, et al. Relapsing visceral leishmaniasis in a HIV-1 infected patient with advanced disease. Acta Clin Belg. 2013;68:124–27. doi: 10.2143/ACB.3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolday D, Berhe N, Akuffo H, Britton S. Leishmania-HIV interaction: immunopathogenic mechanisms. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:182–87. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goto H, Prianti Md. Immunoactivation and immunopathogeny during active visceral leishmaniasis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2009;51:241–46. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652009000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourgeois N, Bastien P, Reynes J, et al. ‘Active chronic visceral leishmaniasis’ in HIV-1-infected patients demonstrated by biological and clinical long-term follow-up of 10 patients. HIV Med. 2010;11:670–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doudi M, Setorki M, Narimani M. Bacterial superinfection in zoonotic cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(9):BR356–61. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickering MC, D’Agati VD, Nester CM, et al. C3 glomerulopathy: consensus report. Kidney Int. 2013;84:1079–89. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerns E, Rozansky D, Troxell ML. Evolution of immunoglobulin deposition in C3-dominant membranoproliferative glomerulopathy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:2227–31. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2565-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaigne V, Knefati Y, Lafarge R, et al. [A patient with visceral leishmaniasis and acute renal failure in necrotizing glomerulonephritis] Néphrologie. 2004;25:179–83. [in French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]