Abstract

Distinct subsets of sensory nerve fibres are involved in mediating mechanical and thermal pain hypersensitivity. They may also differentially respond to analgesics. Heat-sensitive C-fibres, for example, are thought to respond to µ-opioid receptor (MOR) activation while mechanoreceptive fibres are supposedly sensitive to δ-opioid receptor (DOR) or GABAB receptor (GABABR) activation. The suggested differential distribution of inhibitory neurotransmitter receptors on different subsets of sensory fibres is, however, heavily debated. We now quantitatively compared the degree of presynaptic inhibition exerted by opioids and the GABABR agonist baclofen on 1) vesicular glutamate transporter subtype 3 positive (VGluT3+) non-nociceptive primary afferent fibres and 2) putative nociceptive C-fibres. To investigate VGluT3+ sensory fibres, we evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents with blue light at the level of the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) in spinal cord slices of mice, expressing channelrhodopsin-2. Putative nociceptive C-fibres were explored in VGluT3-knockout mice via electrical stimulation. The MOR agonist DAMGO strongly inhibited both VGluT3+ and VGluT3− C-fibres innervating lamina I neurons but generally had less influence on fibres innervating lamina II neurons. The DOR agonist SNC80 did not have any pronounced effect on synaptic transmission in any fibre type tested. Baclofen, in striking contrast, powerfully inhibited all fibre populations investigated. In summary, we report optogenetic stimulation of DRG neurons in spinal slices as capable approach for the subtype-selective investigation of primary afferent nerve fibres. Overall, the pharmacological accessibility of different subtypes of sensory fibres considerably overlaps, indicating that MOR, DOR and GABABR expression is not substantially segregated between heat and mechanosensitive fibres.

Introduction

Pain is frequently associated with enhanced or ongoing input from sensory nerve fibres to spinal dorsal horn neurons [19;35;41]. Depending on the subtypes of sensory fibres involved, this can lead to diverse symptoms such as mechanical and thermal pain hypersensitivity [24]. For example, vesicular glutamate transporter 3 positive (VGluT3+) sensory fibres do not mediate pain in naïve animals or heat hypersensitivity after injury, but are involved in mechanical and cold hypersensitivity in some animal models of neuropathic and inflammatory pain [13;44]. It has been suggested that different populations of sensory fibres, and consequently, different modalities of pain, are differentially targeted by pharmaceuticals. While μ-opioid receptor (MOR) agonists are suggested to inhibit heat pain, δ-opioid receptor (DOR) agonists, and GABAB receptor (GABABR) agonists supposedly inhibit acute mechanical pain, as well as mechanical hypersensitivity post tissue or nerve injury [11;42]. There is, however, a considerable controversy regarding the modality-specific distribution of presynaptic neurotransmitter receptors on primary afferent nerve terminals [6;9;46;48]. While some investigators report a clear segregation of MORs and DORs on peptidergic and non-peptidergic DRG neurons [42], others find that MOR and DOR mRNAs are co-localized in the same neurons [48]. Similarly, the distribution of GABABRs on synaptic terminals of sensory nerve fibres is unclear. Despite having been proposed to preferentially inhibit high-threshold C-fibres [32], GABABR agonists have been implicated in alleviating mechanical allodynia mediated by low-mechanical threshold afferents [28]. In any case, it would be advantageous for pharmacological therapies if drugs differentially influenced neurotransmitter release from non-nociceptive versus nociceptive fibres.

However, evidence for the presence of functional opioid or GABABRs at synaptic terminals of distinct fibre populations is scarce, as most studies to date have focused on somatic receptor expression in dissociated dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons [33;48]. In electrophysiological recordings, an approachwell-suited to study synaptic transmission, subpopulations of A- and C-fibres cannot readily be distinguished, unless genetic modifications are introduced [10;47]. Here we employed an optogenetic approach to specifically investigate subpopulations of VGluT3+ sensory fibres. Mice that express Cre recombinase in VGluT3+ neurons (VGluT3-cre) were crossed to cre-dependent channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) mice, Ai27 or Ai32, and blue light was applied to specifically activate VGluT3+ sensory fibres. The degree of presynaptic inhibition exerted by the MOR agonist DAMGO, the DOR agonist SNC80, and the GABABR agonist baclofen on VGluT3+ A- and C-fibres innervating spinal lamina I and II neurons was compared to the presynaptic inhibition of putative nociceptive C-fibres activated by electrical stimulation in VGluT3−/− mice. MOR agonists more strongly depressed synaptic transmission of C-fibres innervating lamina I than lamina II neurons. DOR activation had only minor effects, while GABABR activation powerfully depressed synaptic transmission of VGluT3+ as well as VGluT3− fibres.

Materials and Methods

Animals and genotyping

Experiments were performed in male Ai27 or Ai32 mice [31] crossed to VGluT3-cre mice [20], as well as VGluT3-knockout (VGluT3−/−) mice [44]. Genotyping was performed for hChop in Ai27 mice and for eYFP in Ai32 mice. Genotyping in VGluT3-cre mice was performed on an irregular basis as homozygous mice were used for breeding. Primers used were as follows: 1a) hChop forward: GTC CGT CCT GGT CCC TGA GGA T; 1b) hChop reverse: TGT GTT CGC GCC ATA GCA CAA T; 2a) eYFP forward: AGC TGA CCC TGA AGT TCA TCT G; 2b) eYFP reverse: ACT CCA GCA GGA CCA TGT GAT; 3a) iCre forward: CAT CAG AAA CCT GGA CTC TG; 3b) Mvglut3 sq 2A reverse: AGG CTC CAG AAA CAG TCT AAC G. All procedures were performed in accordance with European directives on the use of animals for scientific purposes and adhered to the guidelines of the Committee for Research and Ethical Issues of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).

Dissection procedure

For pharmacological recordings, acute spinal cord slices with dorsal roots and dorsal root ganglia attached were obtained from 3 to 4 week old male mice after a dorsal laminectomy. As axonal photo-stimulations were reported to be more difficult in younger mice [36], 5 to 7 week old mice were used for stimulating axons at the level of the spinal dorsal horn. Dissection, in either case, was performed in chilled artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF, 310–320 mOsm kg−1) consisting of the following (in mM): 95 NaCl, 1.8 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, 15 glucose, and 50 sucrose, oxygenated with 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2, resulting in a pH of 7.4. Slices (~ 600 μm thick) were cut from the lumbar spinal cord with a vibrating microslicer (DTK-1000, Dosaka, Kyoto, Japan) at an angle of 30 – 40 degrees to the transverse plane and were kept at 34 °C for 20 – 30 minutes, before they were allowed to rest at room temperature until use. DRG patch-clamp recordings were performed after coarsely removing the meninges and incubating DRGs in ACSF supplemented with 10 mg/ml Collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 – 120 minutes at 36 °C [25].

Patch-clamp recordings

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed at room temperature with an Axopatch 200B amplifier coupled to a Digidata 1322A interface (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Signals were amplified 2 to 5-fold and recorded at 10 kHz using the pClamp 9 software package (Molecular Devices). To visualize neurons under the 20x objective (Leica HCX APO, N.A. 1.0) of a Leica DM6000CFS microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), infrared illumination was carried out from above the tissue with a 860 nm light-emitting diode (LED; Thorlabs, Munich, Germany) coupled to an optical fibre (BFL37-300, Thorlabs, Munich, Germany). In slice patch-clamp recordings, neurons whose somata were within 25 μm of the dorsal white matter border, or those situated clearly within the dorsal eYFP band in VGluT3-cre x Ai32 mice, were considered lamina I neurons. Neurons with somata at a distance of 25 to 125 μm to the dorsal white matter border were considered lamina II neurons [17; see also 26]. During recordings, ACSF was identical to that during incubation with the exception of (in mM): 127 NaCl, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4, and 0 sucrose. Pipettes were pulled on a horizontal puller (P-87, Sutter Instruments), and resistances were 2–5 MΩ with an intracellular solution consisting of the following (in mM): 120 K-MeSO3, 20 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 20 HEPES, 0.5 EGTA, 2 Na2ATP, as well as 100 μM AlexaFluor 568 or 594, and 0.5 mM GDPβS during all pharmacological recordings; pH 7.28 with KOH. Drugs were washed in no earlier than 15 minutes after breaking in, or 15 minutes after wash-out of the first drug, when cells were probed with more than 1 drug consecutively. Cells were held at holding potentials of −70 mV, and liquid junction potentials were not corrected. Series resistances were monitored by a 50 ms 5 mV hyperpolarizing pulse at the beginning of each recording. Recordings were discarded if the series resistance during application of the drug deviated more than 30 % from control. Enhanced YFP and tdTomato fluorescence were assessed in DRGs and slices on the same microscope via laser scanning microscopy. TdTomato was assessed with confocal microscopy at an excitation wavelength of 543 nm while eYFP was assessed via multiphoton-microscopy in order not to activate ChR2. To this end a Ti-sapphire laser (Chameleon-XR, Coherent, Germany) at 960 nm was used.

Primary afferent stimulation

Channelrhodopsin-2 activation was performed at the level of the DRG with an optical fibre (BFL48-400 or BFL48-1000) coupled to a 470 nm LED (Thorlabs, Munich, Germany), unless stated otherwise. Light-intensities, measured with a hand-held power meter (Lasercheck; Coherent, Dieburg, Germany), were 60–80 mW/mm2. In VGluT3−/− mice, dorsal root stimulation was performed by a square current pulse of 0.1 ms duration and at least twice the response threshold, delivered with a suction electrode coupled to a constant current stimulator (A320, WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA), as described previously [27]. Paired-pulse stimulation was performed every 30 s at paired-pulse intervals of 300 to 500 ms.

Data analysis

Electrophysiological data were analysed off-line using Clampfit (Molecular Devices), IGORPro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA), and Microsoft Excel. For illustrations, data were filtered at 1 kHz. In box and whisker plots, boxes range from the 25th to 75th percentile, and the median is indicated. Whiskers correspond to minimum and maximum values. In addition to the 95% confidence interval of the population median (C.I.), means ± S.E.M. are given in the text. Statistical analyses were performed with SigmaPlot 12.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Student’s t-test was used for comparing two unpaired groups which were normally distributed. For paired groups, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was used, as the Shapiro-Wilk test for normal distribution failed for some groups. Repeated measures ANOVA plus Dunnett’s method for multiple comparisons was used if more than two paired groups were to be compared. The level of statistical significance was set to 0.05.

Chemicals

Chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Invitrogen, and Tocris. SNC80 ((+)-4-[(αR)-α-((2S,5R)-4-Allyl-2,5-di-methyl-1-piperazinyl)-3-methoxybenzyl]-N, N-diethyl-benzamide), DAMGO ([D-Ala2, NMe-Phe4, Gly-ol5]-enkephalin), and baclofen were prepared in stock solutions, stored at −20 °C, and diluted to final concentration in ACSF prior to use.

Results

Validation of the animal model

We used a BAC transgenic VGluT3-cre mouse line [20] to target ChR2 to a particular subset of primary sensory neurons. Our previous immunohistochemical analysis revealed cre expression in 19 % of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons dividing into the following subpopulations [13]: 1) neurofilament 200 (NF200) positive A-fibres most likely transiently expressing VGluT3 and innervating Merkel cells, 2) NF200− / tyrosine hydroxylase positive (TH+) low-threshold mechanoreceptive C-fibers (C-LTMRs), and 3) NF200−/TH− C-fibres, largely co-expressing transient receptors potential cation channel, subfamily M, member 8 (TRPM8) mRNAs. In our initial electrophysiological recordings in spinal cord slices VGluT3-cre mice were crossed to the cre-dependent ChR2 mouse line Ai27. This mouse line contains ChR2 in frame with the red fluorescent tdTomato downstream of a floxed STOP codon (Madisen et al., 2012). In VGluT3-cre x Ai27 mice, we observed red fluorescence in small and large diameter DRG neurons (Figure 1A), corresponding to VGluT3+ C- and A-fibres, respectively. In the spinal dorsal horn, we detected tdTomato fluorescence in lamina I and lamina II inner, consistent with the termination pattern of VGluT3+ C-fibres [44], as well as in deeper laminae of the spinal dorsal horn, the latter likely reflecting ChR2 expressing A-fibres (Figure 1B). We did not observe neuronal profiles expressing the ChR2-tdTomato construct in lamina I and II of the spinal dorsal horn (see also higher magnification image in Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Comparison of Ai27 and Ai32 mice.

A–C, Maximal intensity z-projection of laser-scanning microscopy stack through DRG (A) and spinal cord (B, inset C) of an Ai27 x VGluT3-cre mouse. TdTomato-fluorescence, and correspondingly ChR2 expression, is restricted to a subpopulation of small and large diameter DRG neurons, and the spinal dorsal horn. D, E, Maximal intensity z-projections of laser-scanning microscopy stacks through DRG (D) and spinal cord (E) of an Ai32 x VGluT3-cre mouse. EYFP fluorescence, indicating ChR2 expression, closely resembled tdTomato fluorescence of Ai27 mice. F, Stimulation of the spinal cord with blue light (1 ms, 488 nm, intensity: ~ 1.7 mW), generated with a monochromator (Poly V, TILLvisION), and delivered through the microscope objective (Leica HCX APO, 20x, N.A. 1.0) revealed larger postsynaptic responses in Ai32 x VGluT3-cre mice (black) than in Ai27 x VGluT3-cre mice (grey) mice. Figure illustrates typical examples of photo-stimulated currents. Vertical black bar indicates time point of stimulation. Scale bars in A – E correspond to 50 μm; in F, scale bars indicate 20 ms and 50 pA.

To test whether neurotransmitter release from axons of primary afferent nerve fibres can reliably be evoked by light in VGluT3-cre x Ai27 mice, we next recorded light-evoked postsynaptic responses with the whole-cell patch-clamp technique in spinal dorsal horn neurons, which themselves did not express the ChR2-tdTomato construct. Flashes of blue light (1 ms, 488 nm) delivered through the microscope objective and illuminating the entire field of view, elicited excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in 20/37 dorsal horn neurons. Mean amplitudes in responding neurons were 109 ± 48 pA (ranging from 18 to 417 pA, n = 20, Figure 1F), and light-evoked EPSCs were completely blocked by 0.5–1 μM TTX (n = 3), confirming that they were not due to direct light-evoked depolarizations. Upon repetitive stimulation every 30 seconds, a small fraction of neurons (11 %, 4/35 cells) responded reliably, i.e. without failures, and with a trial-to-trial jitter of less than 1 ms (see also Petreanu et al., 2007). Interestingly, when directly assessing light-evoked depolarizations in ChR2 expressing neurons, 0/10 tdTomato+ DRG neurons were depolarized to action potential threshold, while 3/4 tdTomato-expressing cortical neurons fired light-evoked action potentials. Because our measured light intensities (60–80 mW / mm2) were comparable to those reported in the literature [7], we concluded that Ai27 mice were not well suited to reliably evoke action potentials in axons or somata of VGluT3+ DRG neurons by light.

A similarly designed cre-dependent ChR2 mouse line, Ai32, has been shown to exhibit larger light-evoked currents than Ai27 mice [31]. We therefore tested whether these mice are better suited for activating VGluT3+ sensory neurons. Ai32 mice contain the enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP) in place of tdTomato, but are otherwise constructed identically to the Ai27. On a gross level, the distribution of eYFP fluorescence in the DRG and spinal cord of VGluT3-cre x Ai32 mice resembled that seen with the tdTomato fluorescence in the VGluT3-cre x Ai27 mice (Figure 1D and E). In VGluT3-cre x Ai32 mice, 17/19 eYFP-ChR2− spinal neurons (89 %) responded to the axonal light stimulation, which is significantly more than in VGluT3-cre x Ai27 mice, where only 54 % of cells had responded (p = 0.02). Mean amplitudes of evoked EPSCs in responding neurons amounted to 140 ± 51 pA, ranging from 27 to 353 pA, n = 17, Figure 1F). When stimulated repetitively, every 30 seconds, 7/15 neurons (47 %) responded with a trial-to-trial jitter of less than 1 ms. The proportion of neurons responding reliably to repetitive stimulations was, thus, significantly higher when making use of the Ai32 rather than the Ai27 mouse line (p = 0.017). Additional DRG neuron recordings revealed that 20/27 DRG neurons fired action potentials when directly stimulated with a flash of blue light. As controls, eYFP was not expressed in DRG neurons of cre− littermates (not shown), and electrophysiological experiments confirmed that neither DRG neuron depolarization, nor postsynaptic responses in spinal lamina I and II neurons were elicited by 470 nm light in cre− mice (n = 4 and 10, respectively; not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate that Ai32 mice crossed to VGluT3-cre mice are a suitable animal model for studying VGluT3+ primary afferents.

Pharmacological profiles of different sensory fibre populations

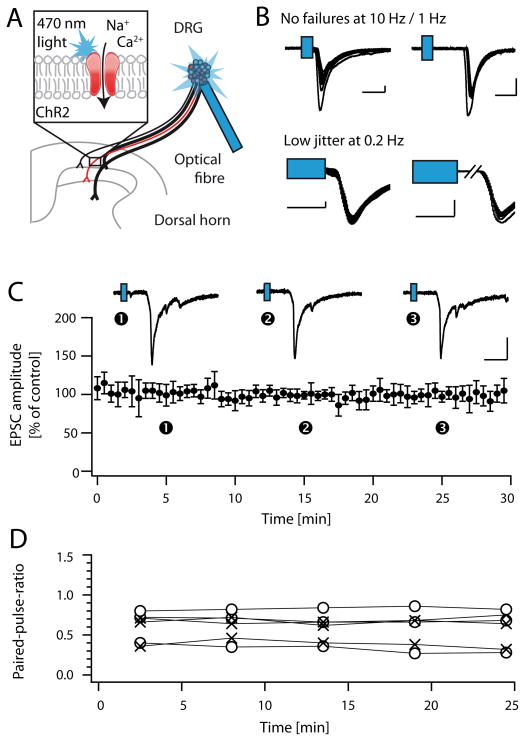

Next we studied the modulation of synaptic transmission at synapses of VGluT3+ primary afferent fibres and spinal dorsal horn neurons in spinal cord slices with dorsal roots as well as DRG attached. ChR2+ fibres were activated at the level of the DRG with a light guide coupled to a high power 470 nm light-emitting diode (LED, pulse duration 5 ms). This approach allowed us to activate VGluT3+ fibres at the level of the DRG, i.e. at a distance of at least 4 mm from the site of neurotransmitter release in the superficial spinal dorsal horn (depicted in Figure 2A). Postsynaptic neurons were classified as lamina I or II neurons, as judged from the distance of their cell bodies to the dorsal boundaries of the slice (see methods for details). We confirmed the monosynaptic origin of evoked EPSCs by means of repetitive light stimulations. To account for the increased delay and jitter of light-evoked action potentials as compared to electrical stimulations [see also 43], we first performed patch-clamp recordings in the presynaptic DRG neurons to quantitatively assess these parameters under our experimental conditions (Table 1). The observed action potential jitter in DRG neurons was about 1 ms when stimulated at 0.2 Hz, and increased with increasing stimulation frequencies. Though not all DRG neurons followed a 1 Hz or 10 Hz stimulation without failures, only spinal dorsal horn recordings of cells not exhibiting failures upon stimulation at 1 Hz (C-fibres, conduction velocity ≤ 1 m/s) or 10 Hz (A-fibres, conduction velocity ≥ 1.5 m/s) were included in the analysis. The jitter of postsynaptic responses recorded in the spinal dorsal horn was determined at a frequency of 0.2 Hz, and recordings with a high trial-to-trial jitter were discarded (Figure 2B, see Table 1 for details on classification of neurons). These stringent criteria likely resulted in the exclusion of a number of monosynaptic responses; however, they allowed us to be reasonably sure that the cells we recorded from received indeed monosynaptic input from VGluT3+ primary afferents. In all experiments, GDPβS (0.5 mM) was included in the recording pipette in order to block postsynaptic G-protein-mediated responses [2]. We additionally assessed the paired-pulse ratio as an indication for presynaptic drug effects, and further control experiments confirmed that light evoked EPSCs could reliably be evoked every 30 seconds over a period of at least 30 minutes (n = 7, Figure 2C). Average run-down was 2 % per 10 minutes, as determined by a linear fit to the mean data. Paired-pulse-ratios did not change significantly during the recording period (n = 6, Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Light-activation of VGluT3+ fibres.

A, Scheme depicting experimental approach: EPSCs were evoked with blue light (470 nm) at the level of the DRG in spinal cord slices with dorsal roots and DRGs attached. B, EPSCs were considered of monosynaptic origin, if they 1) did not exhibit failures upon repetitive stimulation (top left and right: sample traces of A- and C-fibres (distinguished by their conduction velocities), respectively), and 2) if they exhibited a low jitter upon stimulation at 0.2 Hz (bottom, see also Table 1). Scale bars indicate 200 pA, and 10 or 5 ms, for top and bottom traces, respectively. C, Control recordings revealed that light-evoked EPSCs recorded in lamina I and II were stable over the entire recording period (mean value +/− C.I.; n = 7; top: sample traces recorded at the three indicated time points). D, Paired-pulse ratios recorded at paired-pulse intervals of either 300 ms (o) or 500 ms (x) were stable over the entire recording period (n = 6).

Table 1.

Parameters for identifying light-evoked monosynaptic A- and C-fibre-mediated responses

| A) DRG recordings | Large diameter neurons | Small diameter neurons |

|---|---|---|

| Action potential delay after onset of light pulse: | 2 – 4 ms | 2 – 8 ms |

| Mean action potential jitter at 0.2 Hz | ~ 1 ms | ~ 1 ms |

| B) Postsynaptic EPSCs: | A-fibre-mediated responses | C-fibre-mediated responses |

| Conduction velocity (as determined from response delay): | ≥ 1.5 m/s | ≤ 1.0 m/s |

| Failures upon repetitive stimulation: | No failures at 10 Hz | No failures at 1 Hz |

| Jitter upon 0.2 Hz stimulation: | Jitter minus 1 ms < 10% of EPSC latency | |

A, Table illustrating action potential delay and jitter upon photo-stimulation in A- and C-fibres, as measured in large and small diameter eYFP+ DRG neurons, respectively. B, Criteria used for classifying light-evoked EPSCs as monosynaptic A- or C-fibre-mediated responses.

VGluT3+ C-fibres

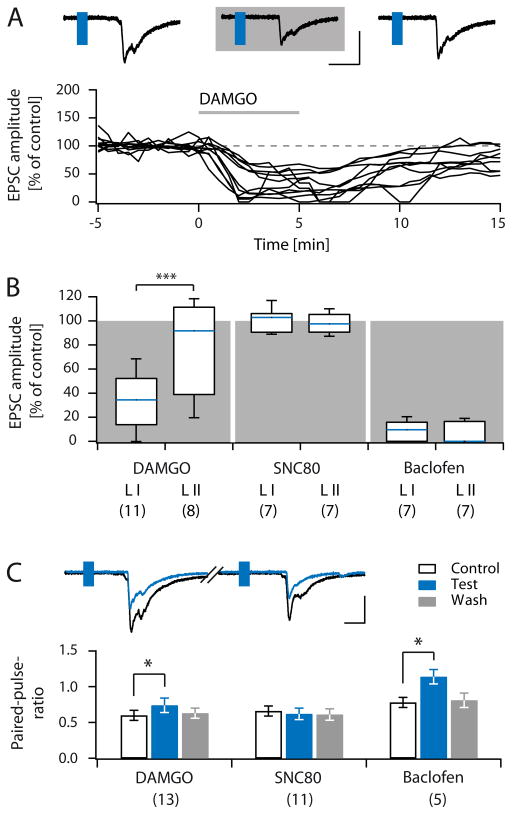

First we assessed the pharmacological profile of VGluT3+ C-fibres. The MOR agonist DAMGO ([D-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol]-enkephalin, 0.5 μM) reversibly reduced light-evoked C-fibre-mediated EPCS recorded in lamina I neurons to 32.1 ± 6.4 % (C.I.: 13.9–52.2 %) of control (n = 11, p < 0.001, Figure 3A, B). DAMGO reversibly inhibited only 2/8 lamina II neurons to less than 50 % of control. The average EPSC amplitudes in this group were, however, not significantly reduced (EPSC amplitude in DAMGO 81.3 ± 13.7 % of control (C.I.: 21.9 – 114.2 %), n = 8, p = 0.461). Taken together, the inhibition exerted by DAMGO was much stronger in lamina I neurons than in lamina II neurons (p = 0.02, Figure 3B), and was associated with an increase in the paired-pulse ratio (n = 13 lamina I and II neurons, Figure 3C). The non-peptide DOR agonist SNC80 ((+)-4-[(αR)-α-((2S,5R)-4-Allyl-2,5-di-methyl-1-piperazinyl)-3-methoxybenzyl]-N,N-diethyl-benzamide; 50 μM) did not significantly influence VGluT3+ C-fibre-mediated EPSCs in either lamina I or lamina II (mean amplitude in SNC80 (5 min) 100.3 ± 4.0 % (C.I.: 90.5 – 106.1 %) and 98.4 ± 3.0 % (C.I.: 90.7 – 105.3 %) of control for lamina I and lamina II neurons, respectively; n = 7, p = 0.938 and 0.688; Figure 3B). In line with the lack of effect on EPSC amplitudes, paired-pulse ratios remained unaffected in the presence of SNC80 (n = 11; Figure 3C). The GABABR agonist baclofen (1 μM) virtually abolished light-evoked, C-fibre-mediated EPSCs both in lamina I, and lamina II neurons (inhibition to 8.4 ± 3.2 % (C.I.: 0 – 15.8 %), and 5.9 ± 3.2 % (C.I.: 0 – 16.4 %) of control for lamina I and II neurons, respectively; n = 7, p = 0.016). In the presence of baclofen, paired-pulse ratios were significantly increased, consistent with a presynaptic inhibition (Figure 3C; calculated from 5/14 neurons, as evoked EPSCs of the remainder were completely blocked).

Figure 3. Pharmacology of VGluT3+ C-fibres in lamina I and II.

A, Sample traces of light evoked EPSCs recorded in lamina I before, during (grey shaded area) and after the application of DAMGO (top). Normalized EPSC amplitudes of 11 lamina I neurons plotted over time, grey bar indicates DAMGO application (bottom). B, Box and whisker diagram showing normalized amplitudes of light-evoked C-fibre-mediated EPSCs recorded in lamina I and II in the presence of DAMGO (0.5 μM), SNC80 (50 μM), and Baclofen (1 μM). Number of experiments is given in brackets below each group. C, Sample paired-pulse recording in control conditions and during application of DAMGO (top). Quantification of paired-pulse ratios of lamina I and II recordings during control conditions (black outline), application of test substances (blue) and wash (grey, bottom panel). Number of experiments is given in brackets below each group. Scale bars in A and C indicate 10 ms or 200 pA. Blue rectangles in sample traces indicate flash of 470 nm light.

A-fibres transiently expressing VGluT3

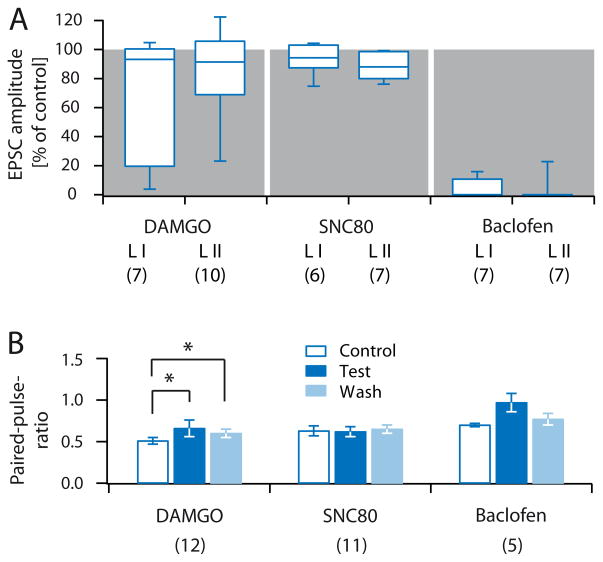

Next we assessed postsynaptic responses, evoked by A-fibres, transiently expressing VGluT3 during development. In this group of recordings, cells were only included if they followed a 10 Hz stimulation without failures. The response jitter was determined by stimulating at 0.2 Hz, as described above (see also Figure 2B, Table 1). On average, DAMGO (0.5 μM) reduced evoked EPSCs in lamina I to 63.1 ± 17.2 % of control (C.I.: 19.6 – 100.3 %, n = 7, p = 0.109, Figure 4A). Interestingly, in roughly half of the neurons (3/7 cells) DAMGO almost completely blocked A-fibre evoked EPSCs (inhibited to ~ 20 % or less), while responses in the other half of neurons remained unaffected (4/7 cells). In lamina II, responses of most neurons were only slightly affected, and in only 2/10 neurons A-fibre evoked EPSCs were inhibited to ~ 50 % or less, together resulting in a statistically non-significant group effect (normalized mean amplitude in DAMGO 84.8 ± 9.4 % (C.I.: 75.6 – 104.7 %), n = 10, p = 0.193, Figure 4A). Application of DAMGO significantly increased mean paired-pulse ratios (n = 12; Figure 4B). Mean EPSC amplitudes in the presence of the DOR agonist SNC80 (50 μM) were 93.7 ± 4.3 % of control (C.I.: 91.7 – 102.6 %) in lamina I (n = 6, p = 0.219), and 87.3 ± 3.4 % of control (C.I.: 79.9 – 98.5 %) in lamina II (n = 7; p = 0.016; Figure 4A). SNC80 did not significantly affect paired-pulse ratios (n = 11; Figure 4B). A-fibre-evoked responses were virtually abolished by baclofen (1 μM; inhibition to 5.3 ± 2.6 % (C.I.: 0 – 10.7 %), and 3.3 ± 3.2 % (C.I.: 0 – 0 %) of control in lamina I and II, respectively; n = 7 each, p = 0.016, Figure 4A). In 5/14 neurons, EPSC amplitudes remained at sufficient size to calculate paired-pulse ratios, resulting in a statistically non-significant increase, likely due to lack of statistical power (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Pharmacology of VGluT3+ A-fibres in lamina I and II.

A, Box and whisker diagram showing normalized EPSC amplitudes of light-evoked A-fibre-mediated EPSCs recorded in lamina I and II in the presence of DAMGO (0.5 μM), SNC80 (50 μM), and Baclofen (1 μM). Number of experiments is given in brackets below each group. B, Quantification of paired-pulse ratios of lamina I and II recordings during control conditions (blue outline), application of test substances (dark blue), and wash (light blue). Number of experiments is given in brackets below each group.

Putative nociceptive C-fibres

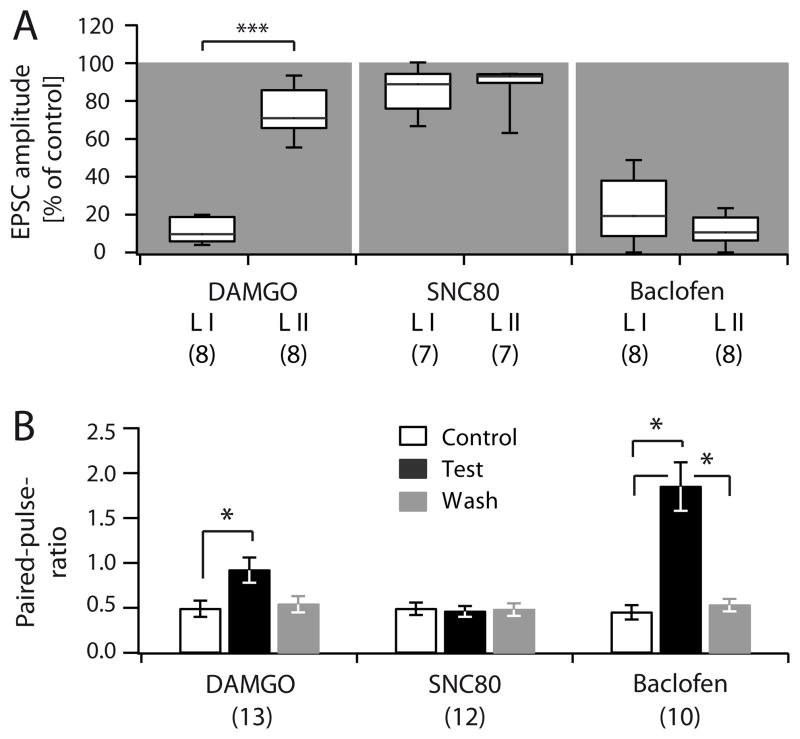

We next assessed the pharmacological profile of putative nociceptive C-fibres in VGluT3−/− mice (Figure 5). The lack of VGluT3 leads to reduced loading of glutamate into presynaptic vesicles of sensory fibres normally expressing VGluT3 (10–15 % of all C-fibres), resulting in disrupted neurotransmitter release from these fibres. Electrically-evoked C-fibre-mediated responses in VGluT3−/− mice therefore predominantly result from the activation of VGluT3− peptidergic (i.e. CGRP+) and non-peptidergic (i.e. IB-4+) C-fibres. DAMGO (0.5 μM) inhibited electrically evoked C-fibre-mediated responses in lamina I and II of VGluT3−/− mice to 11.4 ± 2.3 % (C.I.: 5.7 – 19 4%) and 73.8 ± 4.4 % (C.I.: 65.5 – 87.8 %) of control, respectively (n = 8 each, p = 0.008, Figure 5A). EPSCs of all lamina I neurons were strongly inhibited (less than 20 % of control), while in none of the lamina II neurons, EPSCs were reduced to less than 50 % of control by DAMGO. The decrease in EPSC amplitudes was associated with an increase in paired-pulse ratios (Figure 5B). Bath application of SNC80 slightly reduced EPSC amplitudes in lamina I and II to 85.3 ± 4.6% (C.I.: 75.9 – 94.3 %) and 88.5 ± 4.3 % (C.I.: 89.6 – 94.2 %) of control, respectively (n = 7 each, p = 0.031 and p = 0.016, Figure 5A). Paired-pulse ratios were not significantly altered (Figure 5B). Baclofen strongly inhibited all responses recorded in lamina I and II neurons, and increased paired-pulse ratios (EPSC amplitudes reduced to 31.6 ± 11.0 % (C.I.: 8.1 – 38 %) and 19.5 ± 6.3 % (C.I.: 5.6 – 19.3 %) of control after a 5 minute wash-in period, respectively, n = 8 each, p = 0.008, Figure 5A, B).

Figure 5. Pharmacology of putative nociceptive C-fibres in lamina I and II.

A, Box and whisker diagram showing normalized EPSC amplitudes of electrically evoked C-fibre-mediated EPSCs recorded in lamina I and II of VGluT3−/− mice in the presence of DAMGO (0.5 μM), SNC80 (50 μM), and Baclofen (1 μM). Number of experiments is given in brackets below each group. B, Quantification of paired-pulse ratios of lamina I and II recordings during control conditions (black outline), application of test substances (black), and wash (grey). Number of experiments is given in brackets below each group.

Discussion

The present study shows that Ai32 mice are better suited than Ai27 mice for subtype-specific optogenetic stimulation of sensory fibres. We demonstrate that MOR agonists inhibit all groups of C-fibres innervating lamina I neurons considerably stronger than those innervating lamina II neurons. DOR receptor agonists did not have any pronounced presynaptic effects in any fibre type studied. GABABR agonists, in contrast, strongly depressed evoked EPSCs in all fibre types tested.

The experimental approach

The expression of neurotransmitter receptors by different subclasses of primary afferent fibres has previously been probed on dissociated DRG neurons via binding studies, in-situ hybridization, or immunohistochemical stainings [33;48]. Somatic expression, however, is rather indirect evidence for the expression of functional receptors at synaptic terminals. Behavioural studies, on the other hand, are useful for probing the influence of analgesics on the different modalities of pain, but do not reveal the precise site of action. The presently used optogenetic approach allowed us to directly probe the degree of inhibition exerted by selective receptor agonists on different classes of primary afferent fibres. Our VGluT3-cre mouse expressed cre recombinase in the expected subpopulations of primary afferent fibres. In agreement with a previous study in the brain [31], we found that Ai32 mice are better suited than Ai27 mice for optogenetic stimulation of sensory fibres. The reason is unclear but might be due to interference of the tdTomato tag with the ChR2 channel [1;31]. In comparison with previous attempts to activate distinct subsets of primary afferent fibres by light [47], the present approach yielded more reliable monosynaptic responses, as judged from repetitive stimulations at 0.2 Hz.

A major concern in optogenetic studies, are the slow kinetics of ChR2, resulting in calcium-dependent after depolarisations, and increased release probabilities when directly stimulating presynaptic terminals [43;52]. We circumvented this drawback by stimulating at a distance of at least 4 mm from the site of neurotransmitter release. This not only allowed us to rule out confounding effects on neurotransmitter release [51], but also enabled us to clearly distinguish A- and C-fibre-mediated responses by their different latencies. Our experimental approach can be adapted to virtually any genetically identified type of sensory fibre, provided a mouse line, expressing cre recombinase in the desired type of neuron exists.

Presynaptic opioid receptors

Virtually all clinically used opioids target MORs. In animal models, MOR agonists have been reported to preferentially inhibit heat pain [42] or to reduce withdrawal latencies independent of pain modality [8;23;34, and others]. We found that nociceptive C-fibres innervating lamina I neurons were inhibited more strongly by the MOR agonist DAMGO than fibres innervating lamina II neurons. The strong inhibition, observed in lamina I, is in line with MOR expression on peptidergic, CGRP+ fibres, terminating in lamina I. Thus, our results are compatible with a MOR-dependent inhibition of primary afferents triggering heat pain, as suggested previously [42]. μ-Opioid-receptor expression is, however, by no means restricted to this fibre population, as significant inhibition was also observed in VGluT3+ C-fibres innervating lamina I (but not lamina II) neurons. The preferential inhibition of VGluT3+ C-fibres innervating lamina I vs. lamina II neurons could be explained by the two subpopulations of VGluT3+ C-fibres described to date. Small diameter DRG neurons co-expressing VGluT3 and TH innervate the lanceolate endings of hairy skin, and most likely function as low-threshold mechanoreceptive C-fibres [29;30;36]. The TH− subpopulation of VGluT3+ small diameter neurons is less well characterized. They seem to express the TRPM8 channel [13] and could be muscle afferents (R. P. Seal, unpublished observations) or epidermal free nerve endings [30]. Interestingly, TH+ DRG neurons have recently been shown not to express MORs [4]. Considering the lack of inhibition by DAMGO observed in most VGluT3+ C-fibres innervating lamina II neurons (present study), this suggests that the population of VGluT3+ C-fibres innervating lamina II neurons could be C-LTMRs. Provided that the termination pattern of TH+ and TH− VGluT3+ C-fibres in the spinal dorsal horn is indeed segregated, TH− neurons might be the ones innervating lamina I neurons and being inhibited by MOR activation.

In particular VGluT3+ C-fibres innervating lamina II neurons, as well as VGluT3+ A-fibres displayed a high degree of variability in their responses to DAMGO. This higher variability, as compared to nociceptive C-fibres, was unexpected, as we hypothesised that VGluT3+ fibres would be a more homogenous group than the large populations of peptidergic and non-peptidergic C-fibres that were electrically stimulated in VGluT3−/− mice. However, a recent study also reported heterogeneous responses in putative C-LTMRs upon application of hypo-osmotic solution or a TRPA1-receptor agonist [12]. The response variability observed by us and others may reflect functional heterogeneity or the existence of further not yet identified subpopulations of VGluT3+ A- and C-fibres.

Functional DORs have recently been found on mechanosensitive Aβ fibres innervating Merkel cells and terminating in lamina III/IV of the spinal dorsal horn [4], which might transiently express VGluT3 during development [30]. It is, however, still unclear whether DORs are differentially expressed in mechanical vs. heat sensitive primary afferent fibres terminating in the superficial layers I and II of the spinal dorsal horn. Depending on the experimental approach, DOR receptors have been found largely in peptidergic fibres [3;21;48], in a small subset of non-peptidergic C-fibres and myelinated A-fibres [4;42], or not at all at DRG neuron membranes of naïve animals [6;9]. Our functional approach now revealed that none of the investigated fibre types was considerably inhibited by saturating concentrations of the DOR agonist SNC80. These results indicate that, at most, a small number of DRG neurons innervating the most superficial layers of the spinal dorsal horn express functional DOR receptors in naïve animals. The minor inhibition we observed in putative nociceptive fibres might have resulted from an effect on the TRPA1- or MrgprD- positive subpopulations of primary afferent neurons [4;49]. These findings are in line with behavioural studies, in which significant anti-nociceptive effects were also not observed upon application of SNC80 in naïve mice [16].

Presynaptic GABAB receptors

The GABABR agonist baclofen has been suggested to inhibit C-fibres more efficiently than A-fibres [2;32], and to inhibit pinch-evoked EPSCs more robustly than touch-evoked EPSCs [15]. These findings point to a preferential inhibition of nociceptive versus low-mechanical threshold primary afferent fibres. On the other hand, baclofen has been found useful for the treatment of mechanical allodynia in animal models [28;40]. Our present results provide an explanation for this apparent discrepancy: Baclofen, at much lower concentrations than reported in previous studies (1 μM vs. 10 μM), strongly inhibited synaptic transmission by VGluT3+ C-LTMRs, which have been attributed an aetiology-dependent role in mechanical and cold allodynia post tissue or nerve injury [13;44]. This presynaptic inhibition by baclofen could underlie the suggested anti-allodynic effects. In addition, the high sensitivity of VGluT3+ fibres to GABABR activation suggests that these fibres, similar to nociceptive fibres, are under strong presynaptic GABAergic inhibition under physiological conditions [50].

Implications for pain therapy

It has been suggested that pain modality rather than aetiology would be the better predictor for treatment outcome in conditions of chronic pain [22;38]. Our study now suggests that the degree of MOR-dependent inhibition depends more on laminar location of the postsynaptic neuron than on the types of afferent fibres involved. In contrast to MOR activation, DOR and GABABR activation exhibited uniform effects on all fibres investigated. However, neurotransmitter receptor expression or function might be altered in conditions of chronic pain, and intrathecal DOR agonists may prove useful therapeutic agents for the treatment of pain, if chronic injury or inflammation leads to an increased functional coupling of DORs to voltage-gated calcium channels [37], or to an enhanced plasma membrane expression in distinct fibre populations [3;5;18; but see also 45]. Given that DOR activation was largely ineffective in inhibiting synaptic transmission in naïve animals, such a treatment would most likely result in reduced adverse effects as compared to pharmaceuticals acting on a large number of fibres in the naïve state.

Our finding that virtually all classes of primary afferent fibres were strongly inhibited by baclofen, including those that were unresponsive to MOR activation, suggests that the activation of presynaptic GABABR may be advantageous for the treatment of pain states that either result from the activity of a number of different fibre populations, or from activity in fibres not responsive to MOR agonists. And indeed, there is evidence from case studies in humans that intrathecal baclofen can be beneficial for relieving severe tactile allodynia or burning pain, refractory to treatment with morphine [53]. As VGluT3+ primary afferent are implied in chemotherapy (oxaliplatin)-induced pain [13], and baclofen strongly inhibited all classes of VGluT3+ primary afferents (present paper), baclofen may prove a beneficial agent for the treatment of oxaliplatin-induced mechanical and cold allodynia. Our finding that near-complete inhibition of neurotransmission can be achieved via activation of presynaptic GABABR, likely containing the GABAB1a subunit [14;39;46], lets us further speculate that the development of GABAB1a subunit-specific agonists for intrathecal injection may prove a highly beneficial therapeutic strategy for limiting the side effects of pharmacological therapy.

Acknowledgments

Support for the work was provided by OeNB project #14420 (J.S.) and NINDS NS0084191 (R.P.S.). We thank Liesbeth Forsthuber, Johannes Berger, Sonja Forss-Petter and Manuela Haberl for help with genotyping; and the Sandkühler lab for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Silke D. Honsek, Email: silke.honsek@meduniwien.ac.at.

Rebecca P. Seal, Email: rpseal@pitt.edu.

Jürgen Sandkühler, Email: juergen.sandkuehler@meduniwien.ac.at.

References

- 1.Asrican B, Augustine GJ, Berglund K, Chen S, Chow N, Deisseroth K, Feng G, Gloss B, Hira R, Hoffmann C, Kasai H, Katarya M, Kim J, Kudolo J, Lee LM, Lo SQ, Mancuso J, Matsuzaki M, Nakajima R, Qiu L, Tan G, Tang Y, Ting JT, Tsuda S, Wen L, Zhang X, Zhao S. Next-generation transgenic mice for optogenetic analysis of neural circuits. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:160. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ataka T, Kumamoto E, Shimoji K, Yoshimura M. Baclofen inhibits more effectively C-afferent than Aδ-afferent glutamatergic transmission in substantia gelatinosa neurons of adult rat spinal cord slices. Pain. 2000;86:273–282. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bao L, Jin S-X, Zhang C, Wang LH, Xu Z-Z, Zhang F-X, Wang L-C, Ning F-S, Cai H-J, Guan J-S, Xiao H-S, Xu Z-Q, He C, Hökfelt T, Zhou Z, Zhang X. Activation of delta opioid receptors induces receptor insertion and neuropeptide secretion. Neuron. 2003;37:121–133. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardoni R, Tawfik VL, Wang D, Francois A, Solorzano C, Shuster SA, Choudhury P, Betelli C, Cassidy C, Smith K, de Nooij JC, Mennicken F, O’Donnell D, Kieffer BL, Woodbury CJ, Basbaum AI, MacDermott AB, Scherrer G. Delta opioid receptors presynaptically regulate cutaneous mechanosensory neuron input to the spinal cord dorsal horn. Neuron. 2014;81:1312–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cahill CM, Holdridge SV, Morinville A. Trafficking of δ-opioid receptors and other G-protein-coupled receptors: implications for pain and analgesia. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cahill CM, McClellan KA, Morinville A, Hoffert C, Hubatsch D, O’Donnell D, Beaudet A. Immunohistochemical distribution of delta opioid receptors in the rat central nervous system: evidence for somatodendritic labeling and antigen-specific cellular compartmentalization. J Comp Neurol. 2001;440:65–84. doi: 10.1002/cne.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardin JA, Carlén M, Meletis K, Knoblich U, Zhang F, Deisseroth K, Tsai L-H, Moore CI. Targeted optogenetic stimulation and recording of neurons in vivo using cell-type-specific expression of Channelrhodopsin-2. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:247–254. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen S-R, Pan H-L. Blocking μ opioid receptors in the spinal cord prevents the analgesic action by subsequent systemic opioids. Brain Res. 2006;1081:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng PY, Svingos AL, Wang H, Clarke CL, Jenab S, Beczkowska IW, Inturrisi CE, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural immunolabeling shows prominent presynaptic vesicular localization of δ-opioid receptor within both enkephalin- and nonenkephalin-containing axon terminals in the superficial layers of the rat cervical spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5976–5988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-05976.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daou I, Tuttle AH, Longo G, Wieskopf JS, Bonin RP, Ase AR, Wood JN, De Koninck Y, Ribeiro-Da-Silva A, Mogil JS, Séguéla P. Remote optogenetic activation and sensitization of pain pathways in freely moving mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33:18631–18640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2424-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Vry J, Kuhl E, Franken-Kunkel P, Eckel G. Pharmacological characterization of the chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;491:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delfini M-C, Mantilleri A, Gaillard S, Hao J, Reynders A, Malapert P, Alonso S, Francois A, Barrere C, Seal R, Landry M, Eschallier A, Alloui A, Bourinet E, Delmas P, Le Feuvre Y, Moqrich A. TAFA4, a chemokine-like protein, modulates injury-induced mechanical and chemical pain hypersensitivity in mice. Cell Rep. 2013;5:378–388. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Draxler P, Honsek SD, Forsthuber L, Hadschieff V, Sandkühler J. VGluT3+ primary afferents play distinct roles in mechanical and cold hypersensitivity depending on pain etiology. J Neurosci. 2014;34:12015–12028. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2157-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engle MP, Gassman M, Sykes KT, Bettler B, Hammond DL. Spinal nerve ligation does not alter the expression or function of GABAB receptors in spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia of the rat. Neuroscience. 2006;138:1277–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuhara K, Katafuchi T, Yoshimura M. Effects of baclofen on mechanical noxious and innocuous transmission in the spinal dorsal horn of the adult rat: in vivo patch-clamp analysis. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;38:3398–3407. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallantine EL, Meert TF. A comparison of the antinociceptive and adverse effects of the μ-opioid agonist morphine and the δ-opioid agonist SNC80. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;97:39–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto_97107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gassner M, Ruscheweyh R, Sandkühler J. Direct excitation of spinal GABAergic interneurons by noradrenaline. Pain. 2009;145:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gendron L, Lucido AL, Mennicken F, O’Donnell D, Vincent J-P, Stroh T, Beaudet A. Morphine and pain-related stimuli enhance cell surface availability of somatic δ-opioid receptors in rat dorsal root ganglia. J Neurosci. 2006;26:953–962. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3598-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gold MS, Gebhart GF. Nociceptor sensitization in pain pathogenesis. Nat Med. 2010;16:1248–1257. doi: 10.1038/nm.2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grimes WN, Seal RP, Oesch N, Edwards RH, Diamond JS. Genetic targeting and physiological features of VGLUT3+ amacrine cells. Vis Neurosci. 2011;28:381–392. doi: 10.1017/S0952523811000290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guan J-S, Xu Z-Z, Gao H, He S-Q, Ma G-Q, Sun T, Wang L-H, Zhang Z-N, Lena I, Kitchen I, Elde R, Zimmer A, He C, Pei G, Bao L, Zhang X. Interaction with vesicle luminal protachykinin regulates surface expression of δ-opioid receptors and opioid analgesia. Cell. 2005;122:619–631. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansson PT, Dickenson AH. Pharmacological treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain conditions based on shared commonalities despite multiple etiologies. Pain. 2005;113:251–254. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harriott AM, Gold MS. Contribution of primary afferent channels to neuropathic pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13:197–207. doi: 10.1007/s11916-009-0034-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayar A, Gu C, Al-Chaer ED. An improved method for patch clamp recording and calcium imaging of neurons in the intact dorsal root ganglion in rats. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;173:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heinke B, Balzer E, Sandkühler J. Pre- and postsynaptic contributions of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels to nociceptive transmission in rat spinal lamina I neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:103–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.03083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinke B, Gingl E, Sandkühler J. Multiple targets of μ-opioid receptor mediated presynaptic inhibition at primary afferent Aδ- and C-fibers. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1313–1322. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4060-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang JH, Yaksh TL. The effect of spinal GABA receptor agonists on tactile allodynia in a surgically-induced neuropathic pain model in the rat. Pain. 1997;70:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Rutlin M, Abraira VE, Cassidy C, Kus L, Gong S, Jankowski MP, Luo W, Heintz N, Koerber HR, Woodbury CJ, Ginty DD. The functional organization of cutaneous low-threshold mechanosensory neurons. Cell. 2011;147:1615–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lou S, Duan B, Vong L, Lowell BB, Ma Q. Runx1 controls terminal morphology and mechanosensitivity of VGLUT3-expressing C-mechanoreceptors. J Neurosci. 2013;33:870–882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3942-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madisen L, Mao T, Koch H, Zhuo JM, Berenyi A, Fujisawa S, Hsu YW, Garcia AJ, III, Gu X, Zanella S, Kidney J, Gu H, Mao Y, Hooks BM, Boyden ES, Buzsáki G, Ramirez JM, Jones AR, Svoboda K, Han X, Turner EE, Zeng H. A toolbox of Cre-dependent optogenetic transgenic mice for light-induced activation and silencing. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:793–802. doi: 10.1038/nn.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melin C, Jacquot F, Dallel R, Artola A. Segmental disinhibition suppresses C-fiber inputs to the rat superficial medullary dorsal horn via the activation of GABAB receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;37:417–428. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mennicken F, Zhang J, Hoffert C, Ahmad S, Beaudet A, O’Donnell D. Phylogenetic changes in the expression of delta opioid receptors in spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:349–360. doi: 10.1002/cne.10839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan MM, Fossum EN, Stalding BM, King MM. Morphine antinociceptive potency on chemical, mechanical, and thermal nociceptive tests in the rat. J Pain. 2006;7:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okun A, Liu P, Davis P, Ren J, Remeniuk B, Brion T, Ossipov MH, Xie J, Dussor GO, King T, Porreca F. Afferent drive elicits ongoing pain in a model of advanced osteoarthritis. Pain. 2012;153:924–933. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petreanu L, Huber D, Sobczyk A, Svoboda K. Channelrhodopsin-2-assisted circuit mapping of long-range callosal projections. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:663–668. doi: 10.1038/nn1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pradhan A, Smith M, McGuire B, Evans C, Walwyn W. Chronic inflammatory injury results in increased coupling of delta opioid receptors to voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Mol Pain. 2013;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pradhan AA, Yu XH, Laird JM. Modality of hyperalgesia tested, not type of nerve damage, predicts pharmacological sensitivity in rat models of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price GW, Wilkin GP, Turnbull MJ, Bowery NG. Are baclofen-sensitive GABAB receptors present on primary afferent terminals of the spinal cord? Nature. 1984;307:71–74. doi: 10.1038/307071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reichl S, Augustin M, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. Peripheral and spinal GABAergic regulation of incisional pain in rats. Pain. 2012;153:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandkühler J. Models and mechanisms of hyperalgesia and allodynia. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:707–758. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scherrer G, Imamachi N, Cao Y-Q, Contet C, Mennicken F, O’Donnell D, Kieffer BL, Basbaum AI. Dissociation of the opioid receptor mechanisms that control mechanical and heat pain. Cell. 2009;137:1148–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoenenberger P, Schärer Y-P, Oertner TG. Channelrhodopsin as a tool to investigate synaptic transmission and plasticity. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:34–39. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.051219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seal RP, Wang X, Guan Y, Raja SN, Woodbury CJ, Basbaum AI, Edwards RH. Injury-induced mechanical hypersensitivity requires C-low threshold mechanoreceptors. Nature. 2009;462:651–655. doi: 10.1038/nature08505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stone LS, Vulchanova L, Riedl MS, Williams FG, Wilcox GL, Elde R. Effects of peripheral nerve injury on delta opioid receptor (DOR) immunoreactivity in the rat spinal cord. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361:208–211. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Towers S, Princivalle A, Billinton A, Edmunds M, Bettler B, Urban L, Castro-Lopes JM, Bowery NG. GABAB receptor protein and mRNA distribution in rat spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3201–3210. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H, Zylka MJ. Mrgprd-expressing polymodal nociceptive neurons innervate most known classes of substantia gelatinosa neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13202–13209. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3248-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang H-B, Zhao B, Zhong Y-Q, Li K-C, Li Z-Y, Wang Q, Lu Y-J, Zhang Z-N, He S-Q, Zheng H-C, Wu S-X, Hökfelt TG, Bao L, Zhang X. Coexpression of δ- and μ-opioid receptors in nociceptive sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13117–13122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008382107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wrigley PJ, Jeong H-J, Vaughan CW. Dissociation of μ- and δ-opioid inhibition of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in superficial dorsal horn. Mol Pain. 2010;6:71. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang K, Ma H. Blockade of GABAB receptors facilitates evoked neurotransmitter release at spinal dorsal horn synapse. Neuroscience. 2011;193:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Davidson TJ, Mogri M, Deisseroth K. Optogenetics in neural systems. Neuron. 2011;71:9–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y-P, Oertner TG. Optical induction of synaptic plasticity using a light-sensitive channel. Nat Methods. 2007;4:139–141. doi: 10.1038/nmeth988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuniga RE, Schlicht CR, Abram SE. Intrathecal baclofen is analgesic in patients with chronic pain. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:876–880. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200003000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]