Abstract

Surgical resection remains the cornerstone of therapy for patients with early stage solid malignancies and more than half of all cancer patients undergo surgery each year. The technical ability of the surgeon to obtain clear surgical margins at the initial resection remains crucial to improve overall survival and long-term morbidity. Current resection techniques are largely based on subjective and subtle changes associated with tissue distortion by invasive cancer. As a result, positive surgical margins occur in a significant portion of tumor resections, which is directly correlated with a poor outcome. A variety of cancer imaging techniques have been adapted or developed for intraoperative surgical guidance that have been shown to improve functional and oncologic outcomes in randomized clinical trials. There are also a large number of novel, cancer-specific contrast agents that are in early stage clinical trials and preclinical development that demonstrate significant promise to improve real-time detection of subclinical cancer in the operative setting.

Introduction

Imprecise techniques currently used in conventional surgery to assess tumor resection have lead to positive tumor margin rate of 15–60%.1-5 While the field of medical oncology has integrated recent molecular findings and targeted technology, current surgical resection techniques use palpation and subtle visual changes to judge the border between normal and cancerous tissue. A number of cancer-specific imaging modalities have recently been developed and tested in the preclinical and clinical setting to improve intraoperative identification of cancer in real-time.

Development of intraoperative oncologic imaging for the past several decades has adapted conventional imaging techniques to the operating room. These techniques, which include fluoroscopy, ultrasound, CT and MR imaging (MRI), are becoming more prevalent in advanced surgical suites. MRI to guide surgery of glioblastoma is a model of successful adaptation of cancer imaging through a series of clinical trials. Despite the costs and disruption of workflow, MRI is rapidly becoming standard of care for surgical removal of glioblastoma with over 70 centers in the US at various stages of implementation. Perhaps more suited to the intraoperative environment is the use of wide-field optical imaging techniques using a fluorescent contrast agent. This review will examine the use of conventional anatomic techniques and the recent explosion of optical agents, molecular imaging probes and fluorescent imaging devices that are being developed to fill the need for accurate intraoperative neoplasm detection. The scope of this examination will include both real-time image-guided surgical techniques that are currently in advanced stage clinical trials and promising imaging strategies that are looming on the horizon.

The implication of positive surgical margins

Surgical excision remains the mainstay of therapy for many primary and regional solid tumors. Achieving clear oncologic margins remains a critical element of any surgical approach since residual disease is associated with poor survival and the need for adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy or both.6,7 Although each tumor type presents unique challenges for pathological margin analysis, surgical excision requires three steps for detection: initial assessment prior to incision, post-resection margin analysis, and detection of regional metastasis. Traditionally, the tumor is resected followed by examination of the specimen or the wound bed by frozen section for the presence of subclinical disease at the margin. Although very sensitive, frozen sections are time consuming, are reversed in almost 10% of cases, and can at best sample only 5–10% of the wound bed. In many tumor resections the cut surface of the specimen or wound bed is too large to send more than a fraction of the tumor margin while orientation of the sampled tissue is challenging due to the size, mobility and three-dimensional nature of the specimen or wound bed (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Sampling error in oncologic surgery.

An unresected tongue cancer (upper left pane) requires circumferential mucosal margin assessment that would require almost 8 cm of healthy tissue to be sampled in order to confirm a negative margin (upper right). Once resected (lower left) the wound bed requires almost 40 samples of tissue within the three dimensional cavity (lower right). Geographic mapping of the sample location is complicated by the size and mobility of the defect.

Sampling error of the gross pathological specimen is compounded by the limited amount of tissue that can be examined histologically by a pathologist. In order to adequately assess tumor margins approximately two tissue blocks per centimeter of tissue should be assessed with at least 2 sections per block.8 Importantly, pathological examination requires excessive resection of healthy tissue. If intraoperative imaging could accurately assess tumor margins, it is possible that less healthy tissue would be removed and survival rates could be improved. When positive margins exist, there is no consensus on the amount of residual tumor that will regrow or require adjuvant treatment, but the adverse impact of positive surgical margins on patient outcome has been well documented.4,9

The range of techniques developed for intraoperative margin assessment speaks to the clinical demand for improved strategies. To fill this need, a collaborative approach between disciplines (surgeons, pathology, and radiology) will be required to successfully achieve negative margins and identify cancer with certainty in the operating room.

Conventional imaging translated into intraoperative strategies

Intraoperative diagnostics are conventional imaging techniques that have been adapted to the operating room or modified to become more time efficient (such as frozen section or rapid PTH testing). There have been several landmark studies that represent the potential benefit of imaging to guide surgical oncologists (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of landmark studies evaluating image guided surgery in randomized clinical trials completed or underway (*).

| Imaging Modality | Cancer type |

Trial type | Oncologic results (p <0.05) |

Functional results |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | Breast | Multi-site randomized controlled |

Improve margin status |

Decrease volume resected |

Krekel (Lancet Oncol 2013) |

| MRI | Glioma | Randomized controlled |

Improved complete tumor resection |

No difference in neurologic defects |

Senft (Lancet Oncol 2011) |

|

Optical;

Autofluorescence |

Oral cavity |

Randomized control trial |

Local recurrence | -- | Poh (BMC Cancer 2011)* |

|

Optical;

Fluorescence |

Glioma | Multi-site Randomized controlled |

Improved 6-month survival |

No difference in short-term morbidity |

Stummer (Lancet Oncol 2006) |

Glioblastoma is a highly infiltrative disease where tumor delineation is poorly identified and resection of normal tissues comes at great cost to functional outcomes.10 When MRI was initially utilized for tumor resection, preoperative MRI imaging was hindered by significant problems related to preoperative image registration and intraoperative anatomy.11,12 These impediments, associated with brain shift after craniotomies, initiated the need for real-time imaging modalities. At the onset of intraoperative MRI implementation to surgically assist resection of glioblastoma, the known safety of MRI technology facilitated the approval process despite the workflow impediment, which included the introduction of a large magnet in the presence of surgical instrumentation and added wait time for intermittent imaging. Implementation was possible because of the clinical need to improve outcomes in this disease type. The clinical need and familiarity of the surgeon with MRI image interpretation led to the adaptation of neurosurgery suites outfitted with magnets for repeated imaging during the procedure. Over the past 15 years, studies have shown real-time intraoperative MRI guidance improves extent of resection without increasing neurological deficits and also having a positive impact on survival.11-14 In a randomized control trial, intraoperative MRI achieved a radiographic 96% total resection compared to 68% without surgical guidance.11 Despite increased volume of brain removed when MRI guidance is used, morbidity is unchanged.15,16 However, a recent systematic review of existing data suggests that there is only mid-level (level 2) evidence that intraoperative MRI-guided resection increased extent of tumor resection, improved quality of life and prolonged survival compared to conventional neuronavigation-guided resection.17 Despite the premium on operating room real estate, the limited number of operative indications for this technique and the considerable financial investment required for developing MRI-capable operating rooms, this technology has been placed in centers throughout the country, suggesting the viability of real-time oncologic navigation. Evidence that improved surgical resections results in decrease return to operating room for repeat resection in addition to decreased hospital costs and length of stay18 has led to the implementation of approximately 60 centers in the United States with this technology.

Ultrasound has been shown to be advantageous for image-guided tissue sampling of suspicious lesions or lymph nodes, however intraoperative use for detection of disease for surgical excision has been less widely adapted. Ablation therapy for hepatocellular carcinomas is performed with guidance from conventional B-mode ultrasound.19,20 Development of harmonic imaging and microbubble contrast agents has improved diagnosis of smaller hepatic tumors.21 Microbubbles are FDA approved gas-filled lipid or protein structures that are approximately 10 microns in diameter. Microbubbles are echogenic micelles that mechanically oscillate in the presence of ultrasound pressure. Considering the blood-pool tracer properties of microbubbles, they are frequently used during contrast-enhanced ultrasound to detect and monitor cancer via visualization of hyper and hypo-vascularity. Improved image guided ablation using microbubble contrast agents reduced the need for additional, more invasive procedures since lesions could be treated in a single session.22 Compared to earlier generation ultrasound contrast agents, development of perfluorocarbon and lipid-based microbubbles provide significant vascular detail and are not associated with significant toxicities.23 In neurosurgery, tissue hardness is often used to determine normal from involved brain which is amendable to detection by ultrasound that can accurately detect subtle differences in the elastic properties of tissues.24,25 These properties have been leveraged into a variety of non-contrast based ultrasound techniques for detecting the border between normal brain and tumor. Use of ultrasound for neuronavigation has been shown to improve detection of subcortical lesions and found to be cost-effective relative to other techniques such as MRI26.

Breast conservation surgery (BCS) is standard of care for surgical treatment for early stage breast cancers. However, positive pathological margins (tumor cells present ≤ 2 mm of the surgical margin) following BCS are a significant concern, with a reported incidence of 20–60%.27,28 Of these cases, 15–60% result in need for re-excision.29,30 This exposes patients to additional cost, time, risk of anesthesia, post-operative pain, and poor cosmetic outcomes. It has been shown that patients with positive margins have higher rates of breast cancer recurrence.31,32 Current strategies for tumor identification include adaptation of conventional radiology techniques (wire-guided localization) and postoperative techniques (intraoperative specimen radiography/micro-CT and intraoperative ultrasound-guided resection), pathological confirmation of tissue samples (frozen section analysis, intraoperative touch preparation cytology, and standardized surgical cavity shaving). However, these techniques produce results that vary among treatment centers; each modality has limitations within the operative setting and none have been shown to be superior in outcomes to other techniques.32 A recent randomized clinical trial33 using intraoperative ultrasound compared to palpation-guided surgery found a significant improvement in tumor-involved margins. In this study of 134 patients, 3% of subjects in the ultrasound group had positive margins compared with 17% in the palpation group. As an added benefit, the ultrasound group also had significantly smaller resection volume with less patients requiring adjuvant therapy. Although not yet reported, ultimately the benefit of this technique will be in prolonged disease-specific survival.33

While structural-based imaging has exceptional resolution, it provides limited disease-specific information that is critical for successful ablation, especially in previously treated surgical fields. Thus far, relatively few intraoperative imaging strategies have been uniquely developed for wide field, direct tissue visualization performed in the operating room. Integration of anatomic imaging in brain and sinus surgery provides real-time information for instrument navigation during a procedure, but does not allow visualization of iatrogenic manipulations performed during the procedure. CT and MRI navigation techniques are dependent on fixed registration sites that are available for the craniofacial skeleton, but not widely applicable elsewhere in the body. Successful surgical imaging needs to provide actionable information not otherwise available to the surgeon in a disease-specific manner that would lead to an intervention-dependent improvement in outcome. Thus, despite the wide array of preoperative imaging modalities available for specific disease sites, few are broadly applicable to surgical oncologists. Ideally a technique could be introduced that would be used in multiple cancer types.

Optical imaging strategies

Optical imaging leverages the light emitted from a light source (xenon or laser most commonly) to image unique tissue properties. Optical imaging utilizes either native tissue properties or administered optically labeled targeting agents. The advantages of optical imaging over before mentioned conventional methods are numerous. For one, it allows for real-time feedback with limited disruption in workflow. In addition, optical imaging provides wide-field imaging of the surgical wound bed. When used in combination with an optical contrast agent, optical imaging permits cancer-specific detection as opposed to peripheral tissue alterations/distortions associated with solid tumors.

Autofluorescence-guided surgery

Ultraviolet (UV, 200–400 nm) and visible light (400–700 nm) can be used to excite fluorophores in tissue that results in endogenous tissue fluorescence.34 Clinical studies using autofluorescence combined with conventional white light endoscopy have been successfully applied to open-field surgical applications and endoscopic imaging. Application of UV or short wavelength light to tissue from a filtered light source (weak excitation) or laser (strong excitation) results in tissue emission of light that is dependent upon the optical properties of the tissue. Those molecules responsible for excitation and emission of light are referred to as fluorophores, whereas molecules that absorb but not return light are chromophores (Fig. 2). Endogenous fluorophores include many cancer-specific molecules, such as NADH (reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) and porphyrins (heme pathway derivative). The most prominent chromophore relevant to cancer imaging is hemoglobin. Significant changes in tissue architecture, such as vascular and metabolic composition that occur early in the transition from normal to cancerous tissues, can result in distinct fluorophore composition that can be measured by optical imaging. Although widely used for diagnosis and surveillance in minimally invasive assessment of Barrett’s esophagus, melanoma, colonic polyps, head and neck cancer and bronchogenic lesions,35-38 a limited number of studies have evaluated the application of autofluorescence for margin assessment during surgical resection. Evaluation of breast tissue specimens using optical composition maps have improved identification of positive margins in breast cancer by identifying areas with high cell density.39

Figure 2. Tissue interaction with light.

(A) Light as it enters a medium such as tissue will be reflected and succumbs to scattering that limits penetration. Light can also be absorbed by molecules within the tissue (chromophores) or excite endogenous or exogenously administered molecules to emit light at a different wavelength. (B) Penetration of light through tissue is dependent on the absorptive properties of the tissue at various wavelengths. Near infrared (NIR) light has the best penetration through soft-tissue.

For open field examination of mucosal lesions of the head and neck, a simple hand held device (VELscope, Burnaby, Canada or Indentafi, StarDental, Lancaster, PA) can demonstrate decreased autofluorescence due to destruction of collagen matrix and increased vascularity (Fig. 3). Loss of fluorescence signal correlates with the presence of inflammation or malignancy. Optical sampling has been shown to detect early stage malignant transformation based on histological and genetic endpoints. Alterations at the tumor margins using fluorescence visualization were found to extend beyond those detected by white light, with approximately 47% of margin biopsies found to have occult cancer or severe dysplasia.40 A multisite, randomized clinical trial using tissue autofluorescence is underway to determine if tumor autofluorescence can more accurately predict the actual tumor border compared to white light in oral cavity cancer. Unlike many studies assessing fluorescence imaging, this trial will use clinical endpoints rather than histological parameters.37 Although tissue autofluorescence is applicable to surveillance of previously untreated patients and can be used to direct biopsies,41 assessment of tumor margins in open field surgery is complicated by the presence of blood and limited depth of penetration of endogenous fluorophores. Initially autofluorescence demonstrated promise and posed limited safety concerns in surveillance, however the variation in optical properties has failed to generate data that confirms successful application of these techniques to improve oncological outcomes when compared to conventional techniques.

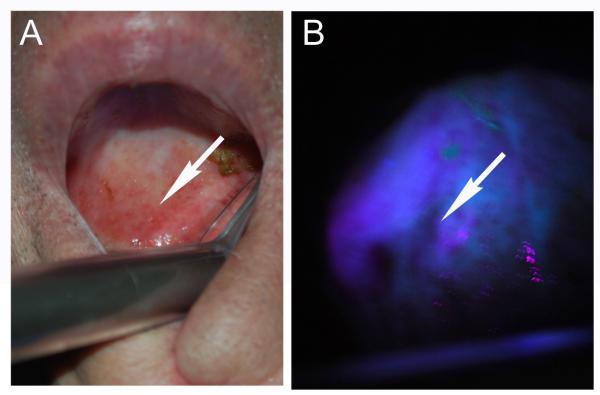

Figure 3. Autofluorescence has been adopted for screening and identification of margins in oral cavity cancer.

Blue/violet light is applied to the mucosa surfaces (A) and areas of decreased autofluorescence correlate with inflamed or neoplastic changes (B).

Clinical trials for brain tumor resections using 5-ALA

The use of 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) in malignant glioma surgery was one of the first ‘proof-of-principle’ investigations to confirm that fluorescent-guided surgery could be used to improve surgical resections. 5-ALA is a precursor in the hemoglobin synthesis pathway and when delivered in excessive dosage to patients will result in preferential accumulation of protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) within cells that possess high metabolic rates. PpIX absorbs blue light (approximately 400 nm) and emits in the red range (approximately 640 nm). Commercially available filter systems can be used to modify existing operating microscopes to incorporate fluorescence guided imaging into the surgical workflow. An example of this multi-functional adaptation is shown in Figure 4 for glioma surgery.42 In a landmark study from seventeen centers in Germany, a randomized clinical trial42 of 322 patients demonstrated that complete resection was achieved in a significantly higher percentage of 5-ALA patients compared to those resected by white-light. Furthermore, progression free survival was significantly better in patients who underwent fluorescent guided resection, albeit the study was not powered to demonstrate a difference in overall survival.43 More aggressive resections using 5-ALA imaging resulted in fewer subsequent surgical interventions and did not translate into significantly higher long-term neurologic morbidity beyond 7-days. Furthermore, patients with incomplete resection had shorter progression-free interval.44,45

Figure 4. Multi-modality imaging techniques adopted in the surgical suite.

(a) Preoperative contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images show patchy/faint CE and (g) hyperintensity on FLAIR sequences. (b) The intratumoral area outside the region of maximum positron emission tomography (PET) tracer uptake verified by the intraoperative navigation system (c) appeared as whitish glioma tissue under the surgical microscope, (d) with no detectable PpIX fluorescence. (e) The corresponding histopathology reveals low-grade glioma tissue according to the WHO criteria in the H&E stain (f) with a low proliferation rate (MIB-1: <10%). (h) In contrast, the intratumoral area inside the region of maximum PET tracer uptake (i) showed similar glioma tissue appearance in the microscopic view, (j) but revealed strong PpIX fluorescence under violet-blue excitation light. (k) The corresponding histopathology reveals high-grade glioma tissue in accordance with an anaplastic focus according to the WHO criteria in the H&E stain (l) with a high proliferation rate (MIB-1: 32%). The final histopathological diagnosis revealed a focally anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO grade III) and the patient was treated with radiochemotherapy. The width of each histopathological image (e, f, k, l) was 300 micrometers (μm). Image and legend information was taken from Widhalm et al, PLoS ONE 2013.

In addition to showing clinical benefit, correlating the presence of fluorescence with tumor pathology is critical to gather specificity and sensitivity information that allow subsequent comparisons between different imaging strategies. In one study, 95% of tumor biopsies were positive for fluorescence in patients who underwent 5-ALA guided resection yielding an overall sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 71%. However, in non-fluorescent samples, 74% were positive for tumor cells (negative predictive value 26%), which was primarily due to the absence of fluorescence in necrotic tumor areas or reactive gliosis.46 However, if this tissue is considered clinically and radiographically neoplastic by the surgeon, the impact on overall outcomes is limited. Not surprisingly, it has been shown that higher levels of fluorescence correlate with elevated PpIX levels and proliferation as measured by Ki67 immunohistochemistry.47 Larger adoption of 5-ALA fluorescence for surgical guidance has been limited by the absence of FDA approval for the drug that is commercially available in Europe (Gliolan, Medvac, Germany). Advanced stage clinical trials are currently ongoing in the United States to evaluate the effectiveness of this strategy in surgical resections (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01502280). This study is sufficiently powered to determine the overall survival and the progression free survival. Similar studies are being conducted to compare completeness of surgical resection between intraoperative MRI guided resections and fluorescence guided surgery (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01575275).

Near-infrared fluorescence (NIR)

Compared to visible light, near-infrared (NIR, 700–900 nm) imaging of fluorescent probes has significantly superior tissue penetration (5–10mm) with little interference from fluorescence emanating from endogenous fluorophores (Fig. 2B). Central to the accurate identification of cancer using real-time fluorescence is maximizing the desired signal over background fluorescence, referred to as the signal-to-noise ratio or in cancer imaging, tumor to background ratio (TBR). Tissue penetration of light in the visible range (<600 nm) is inhibited primarily because hemoglobin absorbs light within that range and is in high concentration in most peritumoral tissues. Because water or lipids absorb light above 900 nm, NIR light provides a unique window between 700 and 850 nm where there is limited interference by biological tissues. Furthermore, NIR does not generate significant autofluorescence, which subsequently improves TBR, however scattering of light in a depth-dependent manner prevents its use in conventional whole body imaging. Tissue penetration is limited to 5–10 mm and significant light scattering results in a diffuse image at depths above 5 mm (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Small fragments of tumor have tissue penetration of greater than 5 mm.

Layers of skin were used to measure the penetration of a small tumor fragment (18 mm3). A mouse bearing a head and neck tumor was injected with cetuximab conjugated to a NIR dye (emission 705 nm) and then the skin and tumor fragments harvested and imaged by stereomicroscopy as above ex vivo. Three layers of skin alone (A, D) had minimal fluorescence. Tumor was clearly visualized alone (B, E) or with layers of overlying skin (C, F). Notice significant scattering associated with overlying tissue.

While the limited tissue penetration of these probes is not well suited for whole body imaging, the excellent tissue definition in the absence of overlying tissue makes NIR probes uniquely suited for intraoperative imaging. This approach can be challenging considering NIR light cannot be visualized by the naked eye and thus requires charge coupled devices (CCD) cameras which can capture incoming photons into electron charges that convert to an image that can be viewed on a monitor. Available NIR camera systems that are FDA-approved for intraoperative use are either incorporated into existing operative hardware or are free standing devices specifically designed for NIR imaging. Operating microscopes used in ophthalmology, neurosurgery and plastic surgery (Leica Microsystems OH5 or Carl Zeiss Pentero) have incorporated a conventional white light microscopy with a NIR imaging camera systems using a band filtered xenon light source. This conveniently allows the surgeon to maintain a wide-field view with the ability to alternate between color and NIR light during the procedure. However, because NIR light is outside the visible range, the viewing of the NIR images requires operating from the screen rather than through the microscope oculars.

The use of NIR imaging is likely to become rapidly adopted in less invasive surgical approaches. Laparoscopy and robotic instrumentation in certain procedures have improved post-operative morbidity and enhanced access to tumors.48,49 However, use of these surgical techniques in cancer surgery limits the tactile feedback and three-dimensional visualization critical to obtaining information about the tumor during resections. Fortunately, minimally invasive approaches represent the ideal setting for use of NIR in oncologic surgery for the following reasons: 1) the surgeon is required to operate from a monitor rather than direct visualization; 2) absence of tactile feedback limits appreciation for subtle changes in tissue density often used to determine the presence of cancer; 3) a low ambient light environment, and; 4) fluorescence imaging systems can now be incorporated into existing operative hardware. Currently the surgical robot can be retro-fitted for fluorescence imaging (Firefly, Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA) which has been used primarily for identification of anatomic structures but not approved for oncologic surgery. Recently laparoscopic instrumentation has been introduced with similar imaging capabilities associated with the robotic instrumentation (PinPoint, Novadaq (Vancouver, Canada).

Freestanding fluorescence imaging devices (SPY, LifeCell, Branchburg, NJ) currently approved for intraoperative use have several advantages. The laser-based (as opposed to xenon light source) fluorophore excitation used in these devices provides significantly higher emission from excited fluorophore and sophisticated post-imaging software is available to analyze captured images and obtain semi-quantitative data. Although freestanding fluorescence imaging systems incur additional investment and impede traditional workflow, these systems allow separation of background autofluorescence from desired signal in real-time and tissue-photon interactions. Clinical studies have been published using a range of devices including the Fluorobeam (Fluoptics, Grenoble, France), Mini-FLARE (Frangioni Laboratory, Boston, MA), and the Photodynamic Eye (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan).50,51 Because of the intuitive need for intraoperative imaging, there has been a significant expansion of experimental devices under evaluation for this purpose. These newer camera systems use multiple camera systems operating in parallel using the same objective to acquire color, fluorescence, and light attenuation imaging to correct for light intensity fluctuations within the tissues in real time.52,53

Devices that are currently in use for surgical guidance are designed to image indocyanine green (ICG) because it remains the only available NIR imaging agent approved for clinical use in the US. ICG has been widely shown to be effective in measuring blood flow and tissue perfusion. Although these instruments are designed for ICG, they are capable of imaging fluorophores with similar excitation and emission profiles. This is highly relevant since development of new cancer-specific agents using optical dyes that can be conjugated to targeting molecules could be imaged with existing operative hardware.

Indocyanine Green (ICG)

ICG was approved for clinical use in the mid-1950s for cardiac output, hepatic function and most commonly fluorescence angiography. ICG is a negatively- charged molecule that binds to large plasma proteins such as albumin immediately after injection and as a result remains within the vascular system in non-diseased tissues. Once bound to plasma proteins, ICG has an absorption peak at 807 nm and emission at 820 nm, which is centered within the NIR imaging window and ideal for soft-tissue penetration. Within minutes after systemic injection (0.1 to 0.5 mg/kg dosing), ICG is rapidly cleared by the liver and excreted into the bile. Toxicity of ICG is very rarely reported, but is primarily associated with allergic reactions. Because it contains a small amount of iodine, contrast allergies associated with iodinated contrasts agents are a relative contraindication, but allergic reactions are associated with doses above 0.5 mg/kg.54

As previously mentioned, multiple NIR imaging platforms are currently available for intraoperative use to perform intraoperative angiography and sentinel lymph node mapping. Lymph node mapping is used to identify the sentinel lymph nodes (SLN), which are the first echelon draining nodes most likely to contain cancer. SLN identification is routinely performed in breast cancer and melanoma. Lymph node mapping methods involve a peritumoral injection of ICG with or without administration of Tc-99m or methylene blue dye. This allows surgical isolation and removal of the SLN. NIR fluorescence often cannot assist with localization until after the surgical incision has been made, and in this setting alternate methods (i.e. Tc-99m) are required to identify SLN. Furthermore, compared to blue dyes, ICG requires a larger administered dose and cannot be visualized without additional hardware. As a result, SLN will likely not become an effective use of NIR imaging in SLN biopsy.50,55

Photoacoustic imaging is another modality for detecting ICG-labeled tissues. Because the imaging technique couples laser excitation of ICG with ultrasound detection, it may circumvent many of the issues regarding sentinel lymph node biopsies.56 The scattering artifact associated with optical imaging is detrimental to acquiring high resolution at deep tissue depth. Photoacoustic imaging takes advantage of low acoustic scattering to improve deep tissue resolution.57,58 With the improved penetration, resolution, and non-ionizing characteristics of photoacoustic imaging, routine clinical applications are on the horizon with several clinical trials underway to detect cancer in breast (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01780532) and prostate tissues (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01551576).

ICG angiography has been shown to provide real-time feedback during cerebral aneurysm clipping that compares favorably to conventional digital subtraction techniques.59 Intraoperative angiography has been used in multiple fields to identify clinically silent, low tissue perfusion that can result in wound healing complications in abdominal wall repair and breast reconstruction.60,61 Although plasma-bound ICG remains intravascular in normal tissues, tumor growth volume is associated with expression of growth factors that promote vascular permeability and poorly-aligned endothelial cells with large gaps and poor lymphatic drainage. This results in the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect that promotes non-specific accumulation of protein bound ICG. While not tumor specific, the presence of administered ICG in tumors is due to passive accumulation which can be leveraged for passively-targeted tumor imaging in humans62 and for margin assessment in preclinical models.63

NIR imaging using ICG as a contrast agent is currently not FDA-approved to guide surgical resections, however it has been investigated in several tumor types. Initially used for NIR cholangiography, investigators noted that hepatocellular carcinomas demonstrated significant fluorescence that was retained over time, which was subsequently extended to include liver metastasis of colorectal origin. In fact, subsequent studies identified significant improvement in detection of clinically unidentified lesions after preoperative injection of ICG.64-66 Recently the technique was shown to be specific for metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma with a positive predictive value of 100%.64 Multimodality imaging using fluorescence and ultrasound-guided hepatic resections demonstrated improved detection of small lesions (<3 mm) leading to a more complete resection.67 Systemic administration of ICG for patients undergoing partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma has demonstrated that NIR imaging could help to differentiate normal renal tissue from tumor, although some reports are not consistent with others finding no correlation with histological presence of tumor.68-70

Breast imaging using optical tomography has shown that neoplasms have a longer retention (~10 minutes) in the breast tumor with rapid clearance in normal tissues. NIR diffuse optical tomography was shown to be comparable to conventional MRI techniques at localization and histological identification.71,72 Using ICG as the contrast agent, NIR diagnostic endoscopy has shown that fluorescence signal correlated with the presence of submucosal invasion, and the imaging approach could distinguish benign lesions from gastric cancers.73,74 This and other studies have suggested the possibility of achieving sufficient tumor-to-background ratio using ICG as a non-specific, vascular-bound contrast agent to identify tumors intraoperatively. Tumor imaging with ICG using conventional fluorescent microscopy is feasible (Fig. 6), however the transient retention of ICG in the tumor and the spillage and persistence of extracorporeal blood introduced into the surgical field during resection may limit the ability to differentiate tumor from normal tissue. Preclinical work has demonstrated improved disease detection and survival after image-guided surgery in animals using novel NIR imaging devices in combination with laboratory animal imaging systems (Pearl Impulse, LICOR, Lincoln Nebraska).63

Figure 6. Intraoperative imaging of tumors using ICG.

A) Intraoperative imaging of tongue cancer under white light using the OH5 surgical microscope (Leica). B) After systemic injection of 7 mg of indocyanine green the Leica FL800 microscope can differentiate tumor border. Untargeted indocyanine green accumulates within the tumor based on enhanced permeability and retention effect of cancer and the high blood flow in tumors, but is otherwise non-specific.

Development of cancer-specific NIR imaging contrast agents

Given that non-specific uptake is unlikely to achieve the tumor-to-background ratio required to convince surgical oncologists to consider fluorescence as a specific marker of cancer, molecular probes have been developed which target the hallmarks of cancer.75 Areas of molecular probe development have included tumor microenvironment,76,77 nanoparticles,78,79 receptor ligands,80,81 antibodies/affibodies directed against cell surface molecules,82-85 and self-quenching probes that are activated by peritumoral enzymes86 (Table 2). While preclinical data supports use of many of these agents, the translational hurdles posed by consistent manufacturing, costs associated with toxicology studies, documentation for IND submission and safety concerns have limited the translation of these agents in humans. Furthermore, industry is often reluctant to support clinical translation since revenue associated with diagnostic agents is a fraction of therapeutic agents despite similar initial investment for FDA approval.87 Because ICG cannot be covalently linked in a stable or predictable manner to other molecules, most of these experimental agents use non-FDA approved optical dyes, which add additional regulatory hurdles.

Table II.

Molecular probes currently being explored for intraoperative optical guidance.

| Probe | Molecular target | Examples | Phase of Development |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Growth factor receptors, growth factors, immunoglobulins |

Panitumumab (EGFR), Bevacizumab (VEGF), MamAb-680 (mmammaglobin-A) |

Phase I: bevacizumnab- IRDye800 (breast and colon cancer) Cetuximab- IRDye800 (head and neck cancer) |

Newman (Cancer Biol Ther 2008) |

| Peptides | Growth factor receptors, integrins (alphaVbeta3) |

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) RGD sequences, somatostatin receptor |

Preclinical | Harlaar (Gynecol Oncol 2013) |

|

Activated

probes |

Protease | Prosense 680 (Cathepsin B), Activatable cell penetrating peptides (ACPPs; instracellular proteases) |

Mostly preclinical Phase I: cathepsing B activatable probe (sarcoma) |

Savariar (Cancer Res 2013) |

| Non-specific | Tumor microenvironment, EPR (enhanced permeability and retention) effect |

Unconjugated fluorescent probes (ICG), nanoparticles (gold nanrods), Polymeric micelles |

Preclinical | Madajewski (Clin Cancer Res 2012) |

| Metabolism | Heme synthesis pathway, folate receptor |

5-aminolevulinic acid | Approved in EU: 5- ALA (brain tumors) Phase 0 and I: folate-FITC (renal and lung cancer) |

Widhalm (PLoS ONE 2013) |

Despite these hurdles, optical agents have been introduced in humans in early phase clinical trials. Folate conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (folate-FITC) was delivered intravenously in patients with ovarian cancer resulting in successful imaging of peritoneal metastases using a charge-coupled digital camera in parallel with conventional color imaging. A significantly higher number of intraperitoneal metastatic sites were detected using fluorescence imaging compared to color imaging as determined by five independent surgeons. 88 This study demonstrated important ‘proof-of-principle’ for surgical imaging but the approach may be limited in other tumor types. Additional studies using folate-FITC as an intraoperative cancer imaging agent in the United States are currently underway in lung cancer with safety as the primary endpoint (clinicaltrials.gov, trial NCT01778920). Kirsch and colleagues have developed cathepsin activated near-infrared fluorescent probes which have been shown to be highly sensitive in detection of microscopic residual sarcoma in preclinical surgical models,89,90 and are currently being evaluated in clinical trials (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01626066)

Antibody-based imaging represents an important intersection of therapeutic and diagnostic medicine. Several therapeutic antibodies have been examined in preclinical models for imaging of cancer, including cetuximab, panitumumab, and bevacizumab.91-95 While none of these biologics are currently available for intraoperative imaging in humans, human clinical trials are underway in Europe (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01508572). Use of an FDA-approved targeting molecule facilitates clinical translation since there is an established safety profile, lower manufacturing costs, and reduced time for approval. While these benefits exist, the use of a previously approved therapeutic agent is likely associated with overlapping intellectual property issues that could hinder preclinical development and translation. Although human trials have not been performed, there is the speculative risk that therapeutic antibodies used to image regional lymphatic metastatic disease may be associated with non-specific interactions between the Fc portion of the antibody and immune cells within the lymph nodes. In addition to the application of therapeutic antibodies for imaging, several antibodies have been designed for surgical guidance or PET-based imaging.96 Several of these have been assessed as dual-labeled PET/optical or MRI/optical probes.97,98 Although novel, these dual-purpose agents present additional hurdles in development and translation before their potential is fully realized.

Conclusion

Intraoperative cancer detection, with synchronous resection, is likely to significantly improve surgical outcomes over the next decade. Conventional anatomic imaging strategies adapted for the operating room, together with optical imaging techniques have been successfully tested in humans and have been demonstrated to improve oncologic and functional outcomes. A significant challenge over the next decade will be to identify a cancer-specific contrast agent that can successfully differentiate a wide range of tumors with superior sensitivity and specificity.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: Funding for this work has been provided by NIH/NCI (R21CA179171 and R21DE019232-02). Equipment loan has been provided by LI-COR biosciences (Lincoln, NE) and a grant from Novadaq (Vancouver, Canada).

References

- 1.Woolgar JA, Triantafyllou A. A histopathological appraisal of surgical margins in oral and oropharyngeal cancer resection specimens. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:1034–43. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMahon J, O’Brien CJ, Pathak I, et al. Influence of condition of surgical margins on local recurrence and disease-specific survival in oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41:224–231. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(03)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravasz LA, Slootweg PJ, Hordijk GJ, et al. The status of the resection margin as a prognostic factor in the treatment of head and neck carcinoma. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1991;19:314–318. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkins J, Al Mushawah F, Appleton CM, et al. Positive margin rates following breast-conserving surgery for stage I-III breast cancer: palpable versus nonpalpable tumors. J Surg Res. 2012;177:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iczkowski KA, Lucia MS. Frequency of positive surgical margin at prostatectomy and its effect on patient outcome. Prostate Cancer. 2011;2011:673021. doi: 10.1155/2011/673021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goto Y, Kodaira T, Furutani K, et al. Clinical Outcome and Patterns of Recurrence of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma with a Limited Field of Postoperative Radiotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43:719–725. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyt066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haloua MH, Krekel NM, Winters HA, et al. A systematic review of oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery: current weaknesses and future prospects. Ann Surg. 2013;257:609–620. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182888782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham SC, Fox K, Fraker D, et al. Sampling of grossly benign breast reexcisions: a multidisciplinary approach to assessing adequacy. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:316–322. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199903000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swindle P, Eastham JA, Ohori M, et al. Do margins matter? The prognostic significance of positive surgical margins in radical prostatectomy specimens. J Urol. 2008;179:S47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moliterno JA, Patel TR, Piepmeier JM. Neurosurgical approach. Cancer J. 2012;18:20–25. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3183243f6e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senft C, Bink A, Franz K, et al. Intraoperative MRI guidance and extent of resection in glioma surgery: a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:997–1003. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Senft C, Schoenes B, Gasser T, et al. Feasibility of intraoperative MRI guidance for craniotomy and tumor resection in the semisitting position. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2011;23:241–246. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31821bc003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong JM, Panchmatia JR, Ziewacz JE, et al. Patterns in neurosurgical adverse events: intracranial neoplasm surgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2012;33:E16. doi: 10.3171/2012.7.FOCUS12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Claus EB, Horlacher A, Hsu L, et al. Survival rates in patients with low-grade glioma after intraoperative magnetic resonance image guidance. Cancer. 2005;103:1227–1233. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhnt D, Becker A, Ganslandt O, et al. Correlation of the extent of tumor volume resection and patient survival in surgery of glioblastoma multiforme with high-field intraoperative MRI guidance. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:1339–1348. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhnt D, Ganslandt O, Schlaffer SM, et al. Quantification of glioma removal by intraoperative high-field magnetic resonance imaging: an update. Neurosurgery. 2011;69:852–862. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318225ea6b. discussion 862-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubben PL, ter Meulen KJ, Schijns OE, et al. Intraoperative MRI-guided resection of glioblastoma multiforme: a systematic review. Lancet oncol. 2011;12:1062–1070. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall WA, Kowalik K, Liu H, et al. Costs and benefits of intraoperative MR-guided brain tumor resection. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2003;85:137–142. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6043-5_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lencioni R, Cioni D, Bartolozzi C. Tissue harmonic and contrast-specific imaging: back to gray scale in ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:151–165. doi: 10.1007/s003300101022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minami Y, Kudo M. Review of dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasound guidance in ablation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4952–4959. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i45.4952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solbiati L, Tonolini M, Cova L, et al. The role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the detection of focal liver leasions. European Radiol. 2001;11(Suppl 3):E15–26. doi: 10.1007/pl00014125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aoki S, Hattori R, Yamamoto T, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound using a timeintensity curve for the diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int. 2011;108:349–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masuzaki R, Shiina S, Tateishi R, et al. Utility of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography with Sonazoid in radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:759–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selbekk T, Bang J, Unsgaard G. Strain processing of intraoperative ultrasound images of brain tumours: initial results. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selbekk T, Brekken R, Indergaard M, et al. Comparison of contrast in brightness mode and strain ultrasonography of glial brain tumours. BMC Med Imaging. 2012;12:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-12-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moiyadi A, Shetty P. Objective assessment of utility of intraoperative ultrasound in resection of central nervous system tumors: A cost-effective tool for intraoperative navigation in neurosurgery. J Neurosci Rural Rract. 2011;2:4–11. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.80077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Au GH, Shih WY, Shih WH, et al. Assessing breast cancer margins ex vivo using aqueous quantum-dot-molecular probes. Int J Surg Oncol. 2012;2012:861257. doi: 10.1155/2012/861257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruidiaz ME, Blair SL, Kummel AC, et al. Computerized decision support system for intraoperative analysis of margin status in breast conservation therapy. ISRN Surg. 2012;2012:546721. doi: 10.5402/2012/546721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung W, Kang E, Kim SM, et al. Factors Associated with Re-excision after Breast-Conserving Surgery for Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15:412–419. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2012.15.4.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu CC, Chiang KC, Kuo WL, et al. Low re-excision rate for positive margins in patients treated with ultrasound-guided breast-conserving surgery. Breast. 2013;22:698–702. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunne C, Burke JP, Morrow M, et al. Effect of margin status on local recurrence after breast conservation and radiation therapy for ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1615–1620. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pleijhuis RG, Graafland M, de Vries J, et al. Obtaining adequate surgical margins in breast-conserving therapy for patients with early-stage breast cancer: current modalities and future directions. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2717–2730. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0609-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krekel NM, Haloua MH, Lopes Cardozo AM, et al. Intraoperative ultrasound guidance for palpable breast cancer excision (COBALT trial): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:48–54. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70527-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DaCosta RS, Wilson BC, Marcon NE. Fluorescence and spectral imaging. ScientificWorldJournal. 2007;7:2046–2071. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrero LA, Weusten BL, Bergman JJ. Autofluorescence and narrow band imaging in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39:747–758. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohtani K, Lee AM, Lam S. Frontiers in bronchoscopic imaging. Respirology. 2012;17:261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poh CF, Durham JS, Brasher PM, et al. Canadian Optically-guided approach for Oral Lesions Surgical (COOLS) trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:462. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pavlova I, Williams M, El-Naggar A, et al. Understanding the biological basis of autofluorescence imaging for oral cancer detection: high-resolution fluorescence microscopy in viable tissue. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2396–2404. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilke LG, Brown JQ, Bydlon TM, et al. Rapid noninvasive optical imaging of tissue composition in breast tumor margins. Am J Surg. 2009;198:566–574. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poh CF, Zhang L, Anderson DW, et al. Fluorescence visualization detection of field alterations in tumor margins of oral cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6716–6722. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sweeny L, Dean NR, Magnuson JS, et al. Assessment of tissue autofluorescence and reflectance for oral cavity cancer screening. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:956–960. doi: 10.1177/0194599811416773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Widhalm G, Kiesel B, Woehrer A, et al. 5-aminolevulinic Acid induced fluorescence is a powerful intraoperative marker for precise histopathological grading of gliomas with non-significant contrast-enhancement. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T, et al. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:392–401. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stummer W, Tonn JC, Mehdorn HM, et al. Counterbalancing risks and gains from extended resections in malignant glioma surgery: a supplemental analysis from the randomized 5-aminolevulinic acid glioma resection study. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:613–623. doi: 10.3171/2010.3.JNS097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts DW, Valdes PA, Harris BT, et al. Glioblastoma multiforme treatment with clinical trials for surgical resection (aminolevulinic acid) Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2012;23:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts DW, Valdes PA, Harris BT, et al. Coregistered fluorescence-enhanced tumor resection of malignant glioma: relationships between delta-aminolevulinic acid-induced protoporphyrin IX fluorescence, magnetic resonance imaging enhancement, and neuropathological parameters. Clinical article. J Neurosurgery. 2011;114:595–603. doi: 10.3171/2010.2.JNS091322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valdes PA, Kim A, Brantsch M, et al. delta-aminolevulinic acid-induced protoporphyrin IX concentration correlates with histopathologic markers of malignancy in human gliomas: the need for quantitative fluorescence-guided resection to identify regions of increasing malignancy. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:846–856. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boudreaux BA, Rosenthal EL, Magnuson JS, et al. Robot-assisted surgery for upper aerodigestive tract neoplasms. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:397–401. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sohn W, Lee HJ, Ahlering TE. Robotic surgery: review of prostate and bladder cancer. Cancer J. 2013;19:133–139. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318289dbd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schaafsma BE, Mieog JS, Hutteman M, et al. The clinical use of indocyanine green as a near-infrared fluorescent contrast agent for image-guided oncologic surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:323–332. doi: 10.1002/jso.21943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schaafsma BE, van der Vorst JR, Gaarenstroom KN, et al. Randomized comparison of near-infrared fluorescence lymphatic tracers for sentinel lymph node mapping of cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncology. 2012;127:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garcia-Allende PB, Glatz J, Koch M, et al. Enriching the Interventional Vision of Cancer with Fluorescent and Optoacoustic Imaging. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:664–7. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.099796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harlaar NJ, Kelder W, Sarantopoulos A, et al. Real-time near infrared fluorescence (NIRF) intra-operative imaging in ovarian cancer using an alpha(v)beta(3-)integrin targeted agent. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128:590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Speich R, Saesseli B, Hoffmann U, et al. Anaphylactoid reactions after indocyaninegreen administration. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:345–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-4-345_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sevick-Muraca EM. Translation of near-infrared fluorescence imaging technologies: emerging clinical applications. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:217–231. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-070910-083323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu MH, Wang LHV. Photoacoustic imaging in biomedicine. Rev Sci Instrum. 2006;77:041101. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoelen CG, de Mul FF, Pongers R, et al. Three-dimensional photoacoustic imaging of blood vessels in tissue. Opt Lett. 1998;23:648–650. doi: 10.1364/ol.23.000648. 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang HF, Maslov K, Stoica G, et al. Functional photoacoustic microscopy for highresolution and noninvasive in vivo imaging. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:848–851. doi: 10.1038/nbt1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Washington CW, Zipfel GJ, Chicoine MR, et al. Comparing indocyanine green videoangiography to the gold standard of intraoperative digital subtraction angiography used in aneurysm surgery. J Neurosurgery. 2013;118:420–427. doi: 10.3171/2012.10.JNS11818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang HD, Singh DP. The use of indocyanine green angiography to prevent wound complications in ventral hernia repair with open components separation technique. Hernia. 2013;17:397–402. doi: 10.1007/s10029-012-0935-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Phillips BT, Lanier ST, Conkling N, et al. Intraoperative perfusion techniques can accurately predict mastectomy skin flap necrosis in breast reconstruction: results of a prospective trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:778e–788e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824a2ae8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van der Vorst JR, Schaafsma BE, Hutteman M, et al. Near-infrared fluorescenceguided resection of colorectal liver metastases. Cancer. 2013;119:3411–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Madajewski B, Judy BF, Mouchli A, et al. Intraoperative near-infrared imaging of surgical wounds after tumor resections can detect residual disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5741–5751. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Satou S, Ishizawa T, Masuda K, et al. Indocyanine green fluorescent imaging for detecting extrahepatic metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1136–43. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ishizawa T, Fukushima N, Shibahara J, et al. Real-time identification of liver cancers by using indocyanine green fluorescent imaging. Cancer. 2009;115:2491–2504. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ishizawa T, Tamura S, Masuda K, et al. Intraoperative fluorescent cholangiography using indocyanine green: a biliary road map for safe surgery. J Am Coll of Surg. 2009;208:e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peloso A, Franchi E, Canepa MC, et al. Combined use of intraoperative ultrasound and indocyanine green fluorescence imaging to detect liver metastases from colorectal cancer. HPB (Oxford) 2013;15:928–34. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Angell JE, Khemees TA, Abaza R. Optimization of Near-Infrared Fluorescence Tumor Localization during Robotic Partial Nephrectomy. J Urol. 2013;190:1668–73. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Manny T, Krane LS, Hemal AK. Indocyanine green cannot predict malignancy in partial nephrectomy: histopathologic correlation with fluorescence pattern in 100 patients. J Endourol. 2013;27:918–21. doi: 10.1089/end.2012.0756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krane LS, Manny TB, Hemal AK. Is near infrared fluorescence imaging using indocyanine green dye useful in robotic partial nephrectomy: a prospective comparative study of 94 patients. Urology. 2012;80:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Intes X, Ripoll J, Chen Y, et al. In vivo continuous-wave optical breast imaging enhanced with Indocyanine Green. Med Phys. 2003;30:1039–1047. doi: 10.1118/1.1573791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ntziachristos V, Yodh AG, Schnall M, et al. Concurrent MRI and diffuse optical tomography of breast after indocyanine green enhancement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2767–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040570597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mataki N, Nagao S, Kawaguchi A, et al. Clinical usefulness of a new infrared videoendoscope system for diagnosis of early stage gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:336–342. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Iseki K, Tatsuta M, Iishi H, et al. Effectiveness of the near-infrared electronic endoscope for diagnosis of the depth of involvement of gastric cancers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:755–762. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.110455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Keereweer S, Sterenborg HJ, Kerrebijn JD, et al. Image-guided surgery in head and neck cancer: current practice and future directions of optical imaging. Head Neck. 2012;34:120–126. doi: 10.1002/hed.21625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bailey KM, Wojtkowiak JW, Hashim AI, et al. Targeting the metabolic microenvironment of tumors. Adv Pharmacol. 2012;65:63–107. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397927-8.00004-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang X, Lin Y, Gillies RJ. Tumor pH and its measurement. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1167–1170. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.068981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gindy ME, Prud’homme RK. Multifunctional nanoparticles for imaging, delivery and targeting in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:865–878. doi: 10.1517/17425240902932908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jiang S, Gnanasammandhan MK, Zhang Y. Optical imaging-guided cancer therapy with fluorescent nanoparticles. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7:3–18. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Adams KE, Ke S, Kwon S, et al. Comparison of visible and near-infrared wavelengthexcitable fluorescent dyes for molecular imaging of cancer. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:024017. doi: 10.1117/1.2717137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kramer-Marek G, Longmire MR, Choyke PL, et al. Recent advances in optical cancer imaging of EGF receptors. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:4759–4766. doi: 10.2174/092986712803341584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Andrades P, Bohannon IA, Baranano CF, et al. Indications and outcomes of double free flaps in head and neck reconstruction. Microsurgery. 2009;29:171–7. doi: 10.1002/micr.20588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Newman JR, Gleysteen JP, Baranano CF, et al. Stereomicroscopic Fluorescence Imaging of Head and Neck Cancer Xenografts Targeting CD147. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1063–70. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.7.6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shah N, Zhai G, Knowles JA, et al. F-FDG PET/CT Imaging Detects Therapy Efficacy of Anti-EMMPRIN Antibody and Gemcitabine in Orthotopic Pancreatic Tumor Xenografts. Mol Imaging Biol. 2012;14:237–44. doi: 10.1007/s11307-011-0491-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Withrow KP, Newman JR, Skipper JB, et al. Assessment of bevacizumab conjugated to Cy5.5 for detection of head and neck cancer xenografts. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2008;7:61–66. doi: 10.1177/153303460800700108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weissleder R. Molecular imaging in cancer. Science. 2006;312:1168–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.1125949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Agdeppa ED, Spilker ME. A review of imaging agent development. AAPS J. 2009;11:286–299. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9104-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.van Dam GM, Themelis G, Crane LM, et al. Intraoperative tumor-specific fluorescence imaging in ovarian cancer by folate receptor-alpha targeting: first in-human results. Nat Med. 2011;17:1315–1319. doi: 10.1038/nm.2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Eward WC, Mito JK, Eward CA, et al. A novel imaging system permits real-time in vivo tumor bed assessment after resection of naturally occurring sarcomas in dogs. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:834–42. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2560-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Savariar EN, Felsen CN, Nashi N, et al. Real-time in vivo molecular detection of primary tumors and metastases with ratiometric activatable cell-penetrating peptides. Cancer Res. 2013;73:855–864. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Day KE, Sweeny L, Kulbersh B, et al. Preclinical Comparison of Near-Infrared- Labeled Cetuximab and Panitumumab for Optical Imaging of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Mol Imaging Biol. 2013;15:722–9. doi: 10.1007/s11307-013-0652-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Day KE, Beck LN, Deep NL, et al. Fluorescently labeled therapeutic antibodies for detection of microscopic melanoma. The Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2681–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.24102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Heath CH, Deep NL, Beck LN, et al. Use of Panitumumab-IRDye800 to Image Cutaneous Head and Neck Cancer in Mice. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148:982–990. doi: 10.1177/0194599813482290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Day KE, Beck LN, Heath CH, et al. Identification of the optimal therapeutic antibody for fluorescent imaging of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2013;14:271–277. doi: 10.4161/cbt.23300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Terwisscha van Scheltinga AG, van Dam GM, Nagengast WB, et al. Intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence tumor imaging with vascular endothelial growth factor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 targeting antibodies. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1778–1785. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.092833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Osborne JR, Akhtar NH, Vallabhajosula S, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigenbased imaging. Urologic Oncol. 2013;31:144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sampath L, Kwon S, Ke S, et al. Dual-labeled trastuzumab-based imaging agent for the detection of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 overexpression in breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1501–1510. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.042234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang W, Ke S, Kwon S, et al. A new optical and nuclear dual-labeled imaging agent targeting interleukin 11 receptor alpha-chain. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:397–402. doi: 10.1021/bc0602679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]