Abstract

Cardiac smooth muscle tumors are rare. Three different clinical settings for these tumors have been reported, including benign metastasizing leiomyoma from the uterus, primary cardiac leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, and intravenous cardiac extension of pelvic leiomyoma, which is the most common. We present a case of a 55-year-old woman with a benign metastasizing leiomyoma to the heart 17 years after hysterectomy and 16 years after metastasis to the lung. Immunohistochemical stains for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and estrogen and progesterone receptors were positive, indicating a smooth muscle tumor of uterine origin. To our knowledge, this is only the fourth reported case of benign metastasizing leiomyoma to the heart and the first case of long-delayed cardiac metastasis after successful treatment of pulmonary metastasis. It illustrates that benign metastasizing leiomyoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of cardiac tumors in patients with a history of uterine leiomyoma, especially when associated with pulmonary metastasis.

Keywords: heart, benign metastasizing leiomyoma, primary cardiac tumor

E. N. Consamus, M.D.

Introduction

Primary cardiac tumors are rare, and most cardiac tumors are secondary to metastatic disease.1 Overall, smooth muscle tumors of the heart are extremely rare. Three different clinical settings for cardiac smooth muscle tumors have been reported: intravenous cardiac extension of pelvic leiomyomas,2 benign metastasizing leiomyomas from the uterus,1,3,4 and primary cardiac leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas.5 Here we report a rare entity of metastasizing leiomyoma to the heart with review of the literature.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman presented at a regional hospital with shortness of breath. On imaging, she was found to have a right atrial mass initially thought to be a thrombus and was thus administered Coumadin. She was subsequently referred to Houston Methodist Hospital for further workup and management. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a bilobed, pedunculated, mobile, well-circumscribed mass attached to the intra-atrial septum (Figure 1). The clinical impression was a primary cardiac tumor. The resected tumor was sent for frozen section evaluation with a clinical diagnosis of cardiac myxoma.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging showing a bilobed, pedunculated, mobile, well-circumscribed mass attached to the intra-atrial septum.

Additional history was pursued as part of the pathologic workup, and it was determined that the patient had undergone a hysterectomy 17 years earlier at the age of 38 years. The uterus contained multiple leiomyomata with no malignant features; no necrosis, atypia, or increased mitotic activity was seen. A year after her hysterectomy, she had presented with a pelvic mass as well as a lung nodule, which were diagnosed as a recurrent smooth muscle tumor in the pelvis and “benign metastasizing leiomyoma of the lung,” respectively. Both had a similar morphologic appearance to the primary uterine leiomyomata.

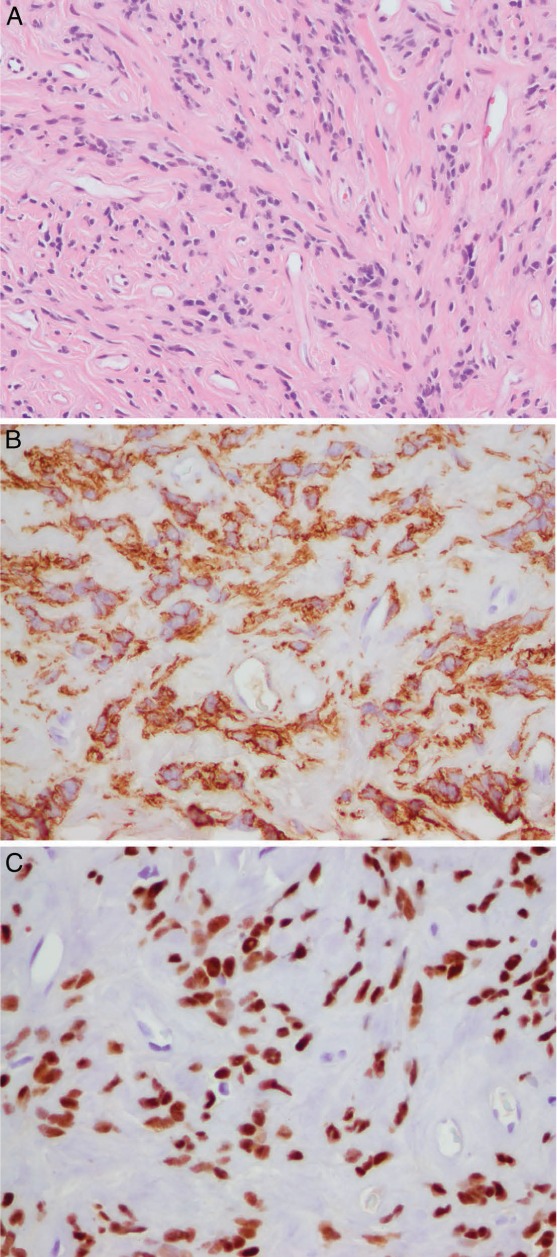

The 4.0 cm resected cardiac tumor was solid, gray-white, and homogeneous with no hemorrhage or necrosis (Figure 2). Microscopically, the tumor was composed of bundles of bland spindle cells with “cigar-shaped nuclei,” no nuclear atypia or necrosis, and only rare mitoses (less than 1/10 high-power fields) (Figure 3 A). Immunohistochemically, the spindle tumor cells expressed smooth muscle actin (Figure 3 B) and desmin and were negative for CD34 and S100 protein. MIB-1 immunohistochemical staining showed low proliferative activity, with less than 1% MIB-1-positive cells. The tumor cells were strongly positive for estrogen receptors (ER) (Figure 3 C) and, focally, weakly positive for progesterone receptors (PR), supportive of uterine origin. The patient is alive and well 16 months after resection of the cardiac tumor, with no evidence of further metastasis.

Figure 2.

The 4-cm resected cardiac tumor was solid, gray-white, and homogeneous with no hemorrhage or necrosis.

Figure 3.

(A) The tumor is composed of bundles of bland spindle cells with “cigar-shaped nuclei,” no nuclear atypia or necrosis, and only rare mitoses (less than 1/10 highpower fields: hematoxylin and eosin stain). (B) The tumor cells were diffusely strongly positive for smooth muscle actin and (C) estrogen receptor and were focally weakly positive for progesterone receptor (not illustrated), which is supportive of uterine origin.

Discussion

This case was confirmed as benign metastasizing leiomyoma to the heart based on clinical history, morphologic evaluation, and immunohistochemical workup. It is the first case of long-delayed benign metastasizing leiomyoma to the heart after successful treatment of a benign metastasizing leiomyoma to the lung 16 years earlier. In addition, we assessed ER and PR expression by immunohistochemistry to further document the uterine origin of the smooth muscle tumor. Our case indicates that a long-delayed cardiac metastasis can occur after successful control of lung metastasis. While it is well-recognized that most cardiac tumors are metastatic malignancies, the differential diagnosis of cardiac tumors in patients with a history of uterine leiomyoma, particularly in patients with a prior history of benign metastasizing leiomyoma to the lung, should include benign metastasizing leiomyoma to the heart.

Benign metastasizing leiomyoma is an extrauterine smooth muscle tumor that occurs in patients with a current or prior history of uterine leiomyoma.6–8 It has been reported in multiple locations, with the lung being the most common metastatic site,6–8 but metastases have also been reported in the skull base,9 spine,9 rib,10 vertebrae,10 lymph nodes,11 and pelvis.12 Of smooth muscle tumors found in the heart, three types of tumors have been reported: primary cardiac smooth muscle tumors (leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma),5 intravenous smooth muscle tumors with intracardiac extension,2,5 and benign metastasizing leiomyoma.1,3,4 Although all three entities are rare, intravenous extension into the heart is the most common, with more than 100 reported cases since the early 1900s,2 and the least reported type is benign metastasizing leiomyoma.

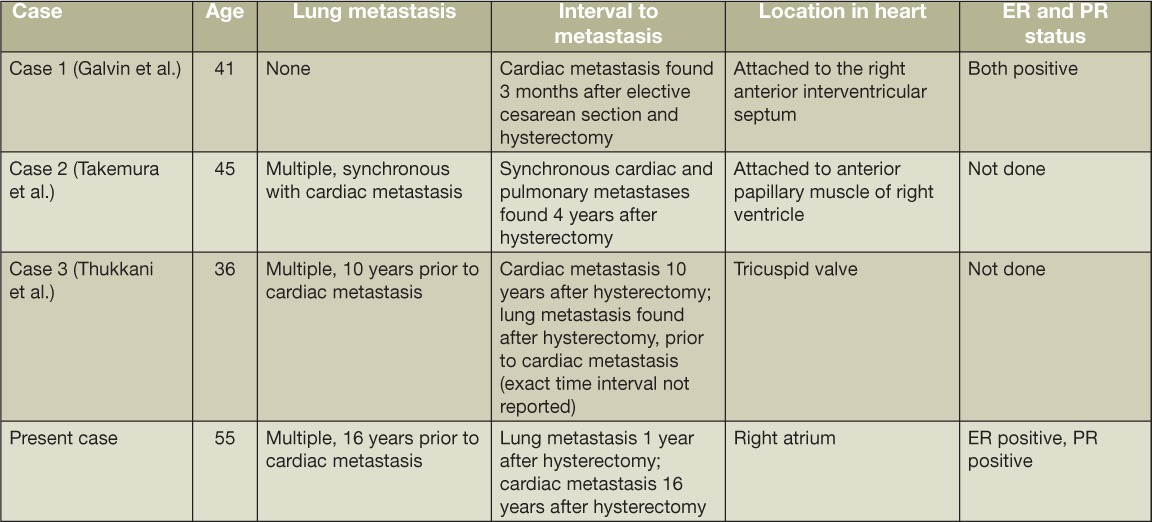

To the best of our knowledge, there are only three prior case reports of benign metastasizing leiomyoma to the heart (Table 1).1,3,4 Galvin et al. reported a case of a 41-year-old woman with an isolated right ventricular metastasis who had undergone a hysterectomy 3 months prior.1 A benign leiomyoma was found in the resected uterus, which had been present 7 years prior at cesarean section. The cardiac tumor, a pedunculated mass attached to the interventricular septum, was resected and diagnosed as a benign leiomyoma. No intravenous leiomyoma was found. The cardiac tumor was ER- and PR-positive. Takemura et al. described a case of a 44-year-old woman who presented with dyspnea and a cardiac murmur after having had a hysterectomy for a leiomyoma 4 years prior.3 A pedunculated mass attached to the anterior papillary muscle of the right ventricle was resected and diagnosed as a benign leiomyoma. Several synchronous, nearly identical-appearing pulmonary nodules were found at surgery. These were biopsied and diagnosed as leiomyomata. The tumors were consistent with benign metastasizing leiomyomata both clinically and pathologically. There was no mention of immunohistochemical evaluation for hormone receptors. Thukkani et al reported a case of a 36-year-old woman who had undergone hysterectomy and left salpingo-oophorectomy for a uterine leiomyoma.3 Postoperatively, she was found to have metastasis in her lungs and residual tumor within the pelvis. The patient underwent resection of the pelvic mass, requiring a right salpingo-oophorectomy and left nephrectomy. She was then treated with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist. Ten years after the hysterectomy, she developed bilateral pedal edema and underwent a cardiac workup. She was found to have multiple pedunculated lesions attached to the tricuspid valve that, histologically, were leiomyomata. No mention of immunohistochemical stains for hormone receptors was made.

Table 1.

Case reports of benign metastasizing leiomyoma to the heart. ER: estrogen receptor; PR: progesterone receptor.

Although there have been three previous reports of lung and cardiac involvement by benign metastasizing leiomyoma,1,3,4 our case is unique because of the 16-year interval between an initial lung metastasis and a subsequent cardiac metastasis. Our case is the longest reported delayed metastasis to the heart after lung metastasis and illustrates the need for long-term close clinical follow-up. The differential diagnosis of benign metastasizing leiomyoma includes a primary leiomyoma in that location. In addition to the clinical history of a uterine tumor, demonstration of hormone receptors in the extragenital tract tumor is helpful, as most uterine smooth muscle tumors are ER- and PR-positive. ER and PR positivity has been reported in multiple cases of benign metastasizing leiomyomata in the lung, which supports uterine origin. On the other hand, primary extrauterine leiomyomata are generally negative for hormone receptors.7,13,14 Of note, benign metastasizing leiomyomata are responsive to hormonal manipulation, with tumor regression after estrogen or combined estrogen and progesterone replacement therapy as well as after pregnancy, oophorectomy, menopause, and treatment with P450 aromatase inhibitors, selective estrogen receptor modulators, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists.7,14

In cases of apparent benign metastasizing leiomyoma, the possibility of under-interpretation of leiomyosarcoma should be considered. It is widely accepted that mitotic rate, cytologic atypia, and presence of coagulative necrosis are the most important predictors of malignant potential in uterine smooth muscle tumors. When metastasis occurs with malignant lesions, the clinical course is generally more aggressive compared to the indolent course seen in benign metastasizing leiomyomata.14 Our case illustrates the indolent course these tumors can take, even with metachronous pulmonary and cardiac metastases.

Conclusion

This case illustrates that smooth muscle tumors of the uterus may rarely metastasize to the heart, particularly in the situation associated with lung metastasis. Including our case, three of four cases had both lung and cardiac metastases. Since cardiac metastasis may be long-delayed, prolonged clinical follow-up is recommended.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have completed and submitted the Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal Conflict of Interest Statement and none were reported.

Funding/Support: The authors have no funding disclosures.

References

- 1.Galvin SD, Wademan B, Chu J, Bunton RW. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma: a rare metastatic lesion in the right ventricle. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010 Jan;89(1):279–81. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kocica MJ, Vranes MR, Kostic D, Kovacevic-Kostic N, Lackovic V, Bozic-Mihajlovic V et al. Intravenous leiomyomatosis with extension to the heart: rare or underestimated? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005 Dec;130(6):1724–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takemura G, Takatsu Y, Kaitani K, Ono M, Ando F, Tanada S et al. Metastasizing uterine leiomyoma. A case with cardiac and pulmonary metastasis. Pathol Res Pract. 1996 Jun;192(6):622–9. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(96)80116-6. discussion 630–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thukkani N, Ravichandran PS, Das A, Slater MS. Leiomyomatosis metastatic to the tricuspid valve complicated by pelvic hemorrhage. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005 Feb;79(2):707–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin C, Chen L, Xiao YB, Chen BC. Giant primary leiomyoma of the right ventricle. J Card Surg. 2010 Mar;25(2):169–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2009.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmad SZ, Anupama R, Vijaykumar DK. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma - case report and review of literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011 Nov;159(1):240–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Awonuga AO, Shavell VI, Imudia AN, Rotas M, Diamond MP, Puscheck EE. Pathogenesis of benign metastasizing leiomyoma: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2010 Mar;65(3):189–195. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181d60f93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goto T, Maeshima A, Akanabe K, Hamaguchi R, Wakaki M, Oyamada Y et al. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma of the lung. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;18(2):121–4. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.11.01688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alessi G, Lemmerling M, Vereecken L, De Waele L. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma to skull base and spine: a report of two cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2003;105(3):170–4. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(03)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang MW, Kang SK, Yu JH, Lim SP, Suh KS, Ahn JS et al. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma: metastasis to rib and vertebra. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011 Mar;91(3):924–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon G, Kim TJ, Sung CO, Choi CH, Lee JW, Lee JH et al. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma with multiple lymph node metastasis: a case report. Cancer Res Treat. 2011 Jun;43(2):131–3. doi: 10.4143/crt.2011.43.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egberts JH, Schafmayer C, Bauerschlag DO, Janig U, Tepel J. Benign abdominal and pulmonary metastasizing leiomyoma of the uterus. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2006 Aug;274(5):319–22. doi: 10.1007/s00404-006-0165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jautzke G, Muller-Ruchholtz E, Thalmann U. Immunohistological detection of estrogen and progesterone receptors in multiple and well differentiated leiomyomatous lung tumors in women with uterine leiomyomas (so-called benign metastasizing leiomyomas). A report on 5 cases. Pathol Res Pract. 1996 Mar;192(3):215–23. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(96)80224-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivera JA, Christopoulos S, Small D, Trifiro M. Hormonal manipulation of benign metastasizing leiomyomas: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Jul;89(7):3183–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]