Abstract

Background

To ensure reliable sources of energy and raw materials, the utilization of sustainable biomass has considerable advantages over petroleum-based energy sources. Photosynthetic algae have attracted attention as a third-generation feedstock for biofuel production, because algae cultivation does not directly compete with agricultural resources, including the requirement for productive land and fresh water. In particular, cyanobacteria are a promising biomass feedstock because of their high photosynthetic capability.

Results

In the present study, the expression of the flv3 gene, which encodes a flavodiiron protein involved in alternative electron flow (AEF) associated with NADPH-coupled O2 photoreduction in photosystem I, was enhanced in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Overexpression of flv3 improved cell growth with corresponding increases in O2 evolution, intracellular ATP level, and turnover of the Calvin cycle. The combination of in vivo13C-labeling of metabolites and metabolomic analysis confirmed that the photosynthetic carbon flow was enhanced in the flv3-overexpressing strain.

Conclusions

Overexpression of flv3 improved cell growth and glycogen production in the recombinant Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Direct measurement of metabolic turnover provided conclusive evidence that CO2 incorporation is enhanced by the flv3 overexpression. Increase in O2 evolution and ATP accumulation indicates enhancement of the AEF. Overexpression of flv3 improves photosynthesis in the Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 by enhancement of the AEF.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13068-014-0183-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Synechocystis sp. PCC6803, flv3, Alternative electron flow, Carbon metabolism, Photosynthesis, Metabolite profiling

Background

Environmental concerns associated with the continued depletion of oil reserves and greenhouse gas emissions have prompted governments to promote research on environmentally benign and sustainable fuels towards realizing energy independence. In particular, utilization of biomass as the starting material for fuel production has recently attracted considerable attention [1,2]. It is anticipated that the use of biofuels as an alternative to fossil fuels will help reduce CO2 accumulation through reduced emissions and recycling of the CO2 that is released when biofuel is combusted as a transport fuel.

Photosynthetic algae are of increasing interest as a renewable source of biomass for the sustainable production of biofuels [3-5], because algal feedstocks do not directly compete with agriculture, as they require no productive land. Cyanobacteria are particularly attractive, because their photosynthetic and biomass production rates are higher than those of terrestrial plants [3,6]. Several cyanobacterial species have the ability to store large amounts of energy-rich glycogen that can be utilized for the production of biofuels, including bio-ethanol [7,8]. In addition, because cyanobacteria are prokaryotes, their metabolic processes are more readily amenable to genetic modifications designed to enhance photosynthetic activity than are those of eukaryotic algae.

In the phototrophic metabolism, carbon assimilation through the Calvin cycle is coupled with consumption of ATP and NADPH. Cyanobacterial cell growth rate is dependent on the intensity of light with the exception of photoinhibition and photooxidative stress, as it drives photosynthetic electron transport and the production of ATP and NADPH. ATP is required not only for turnover of the Calvin cycle, but also for the CO2 concentrating mechanism, which serves to increase the intracellular CO2 concentration [9-11]. Furthermore, ATP is required for glycogen biosynthesis in photosynthetic cells [12], meaning that a continuous supply of ATP is necessary for a higher rate of photosynthesis in cyanobacteria.

ATP is produced by ATP synthase via a proton gradient (ΔpH) across the thylakoid membrane. ΔpH is mainly generated by the photosynthetic linear electron flow (LEF) pathway, although phototrophs, including cyanobacteria, have also developed a large arsenal of alternative electron flow (AEF) pathways, which assist in modulating the ATP/NADPH ratio in response to metabolic demand [13,14]. O2-dependent electron flow, termed the Mehler pathway or water-water cycle (WWC), is one AEF pathway that helps generate a pH gradient [15-17]. In the Mehler pathway, electrons extracted from water by photosystem II (PSII) are used to generate water by the photoreduction of O2 coupled with the oxidation of NADPH in photosystem I (PSI).

In cyanobacteria, flavodiiron (Flv) proteins possess an NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductase module [18]. The cyanobacteria Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 has four genes encoding Flv proteins (Flv1, Flv2, Flv3, and Flv4). The results of an in vitro study with an flv3 mutant provided evidence that Flv3 functions as an NAD(P)H:oxygen oxidoreductase [18]. A subsequent in vivo study with Δflv1 and Δflv3 mutants of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 confirmed that Flv1 and Flv3 are involved in the photoreduction of O2 to H2O in the Mehler reaction [19]. Under fluctuating light conditions, the growth and photosynthesis of Δflv1 and Δflv3 mutants of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 are arrested [20].

In the present study, a recombinant flv3-overexpressing Synechocystis strain (Flv3ox) was constructed to examine the effects of flv3 overexpression on the photosynthetic ability of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Enhancement in the AEF pathway through the regeneration of NADP+ improved ATP accumulation in the Flv3ox cell. Recently, we developed an analytical method to directly measure the turnover of metabolic intermediates in cyanobacteria [21]. The combination of in vivo13C-labeling of metabolites and metabolome analysis using mass spectrometry (MS) enables kinetic visualization of carbon assimilation in central metabolic pathways, such as the Calvin cycle, glycolysis, and glycogen biosynthesis. Here, the dynamic metabolic profiling approach was used to reveal the underlying mechanisms of the enhancement of the photosynthetic carbon flow in the Flv3ox strain.

Results

Construction of an flv3-overexpressing recombinant strain

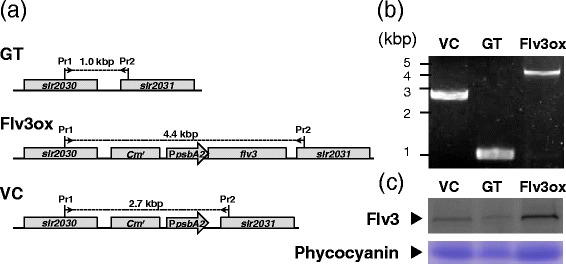

To enhance flv3 expression in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803, we constructed the transformation vector pTCP2031V-flv3, which contained flv3 linked to the psbA2 promoter between the slr2030 and slr2031 genes, which acted as anchoring regions for site-specific integration into the Synechocystis genome through homologous recombination (Figure 1a). A glucose-tolerant (GT) strain of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 was transformed with pTCP2031V-flv3 to yield strain Flv3ox. The chromosomal integration of flv3 was confirmed by genomic PCR (Figure 1b). A vector control (VC) strain, in which the chloramphenicol resistance cassette was inserted into the genome of GT, was constructed with an empty vector pTCP2031V. Immunoblot analysis showed higher levels of Flv3 protein in the Flv3ox strain compared to the parental GT and vector control strains (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Molecular characterization of the parental (GT), flv3 -overexpressing (Flv3ox), and vector control (VC) strains. (a) Genome structure around integration site in glucose-tolerant (GT), Flv3ox, and vector control (VC) strains. Pr1 and Pr2 indicate the positions of the primer used for the PCR screening. Cm r, chloramphenicol resistance cassette; PpsbA2, psbA2 promoter. (b) Genomic PCR analysis of GT, Flv3, and VC strains using Pr1 and Pr2. (c) Immunoblot analysis of Flv3 protein in GT, Flv3ox, and VC cells. Total soluble protein extracted from 1.6 mg DCW Synechocystis cells was reacted with anti-Flv3 antibody after separation on SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Phycocyanin was detected by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. The amount of protein loaded on the gel is 75 μg (GT), 63 μg (Flv3ox), and 70 μg (VC).

Cell growth and O2 evolution by Flv3ox

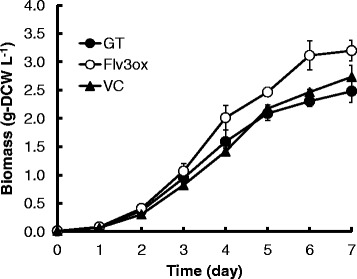

Figure 2 shows the growth of strain GT, Flv3ox, and VC cells cultivated under continuous irradiation with 120 μmol photons m-2 s-1 light intensity and 1% (v/v) CO2 at 30°C. Under these conditions, Flv3ox showed a higher growth rate than the GT and VC strains. After a 7-day cultivation, the cell concentration of Flv3ox reached 3.20 g-dry cell weight (DCW) L-1 and that of GT was 2.48 g-DCW L-1. According to statistical analysis, the biomass concentration of Flv3ox was significantly different from that of GT and VC (Additional file 1). VC demonstrated a similar cell growth ability as GT. Measurements of glycogen showed that Flv3ox had a higher glycogen content (0.117 g-glycogen g-DCW-1) than that of GT (0.091 g-glycogen g-DCW-1) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Time course of cellular biomass in GT, Flv3ox, and VC cultivated under 120 μmol photons m -2 s -1 light intensity and 1% CO 2 conditions. The values are the mean ± SD of ten different measurements.

Figure 3.

Glycogen content in GT and Flv3ox cultivated under 120 μmol photons m -2 s -1 light intensity and 1% CO 2 conditions. The values are the mean ± SD of six different measurements. Statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t-test (** P < 0.01).

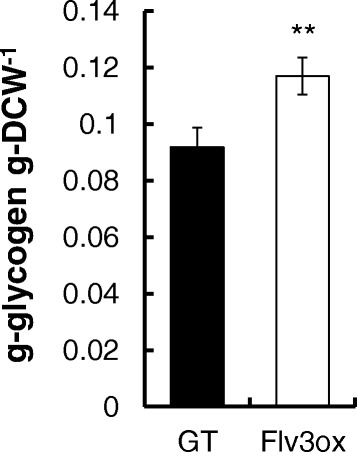

The light dependence of the O2 evolution rate by the two strains of Synechocystis cells was evaluated with an O2 electrode system (Figure 4). Flv3ox exhibited a higher O2 evolution rate than that of GT.

Figure 4.

Light response curves for O 2 evolution rate in GT and Flv3ox cells. When the OD750 reached approximately 4.5, the cells were applied for the photosynthesis analysis. The values are the mean ± SD of three measurements.

Metabolic analysis of Synechocystis cells

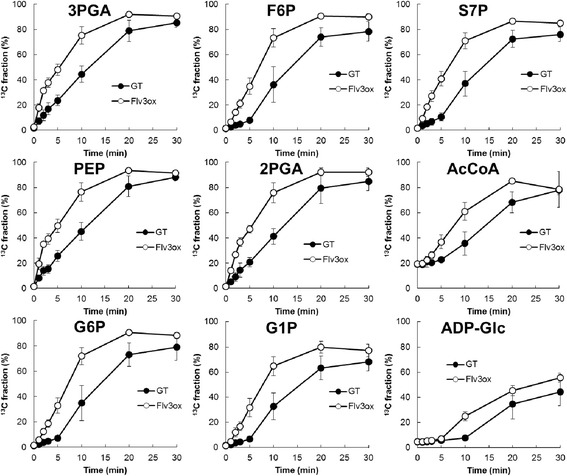

Photosynthetic electron flow generates a proton gradient across the cyanobacterial thylakoid membrane, driving the ATP synthesis necessary for carbon assimilation. Here, the effect of flv3 overexpression on intracellular carbon metabolism was investigated using a dynamic profiling technique [21] that measures the turnover of metabolic intermediates in cyanobacterial cells. The kinetic measurements were performed by the combination of an in-vivo13C-labeling technique and mass isotopomer detection with capillary electrophoresis coupled to MS (CE/MS) for the efficient separation of highly polar molecules. To assess metabolic turnover, extracted intracellular metabolites were analyzed after labeling for between 1 and 30 min (Figure 5). The 13C fraction, which was defined as the ratio of 13C to total carbon in each metabolite, was calculated from mass isotopomer distributions.

Figure 5.

Time course of the 13 C fraction for various metabolites in GT and Flv3ox cells cultivated under 120 μmol photons m -2 s -1 light intensity and 1% CO 2 conditions. The values are the mean ± SD of at least five different experiments.

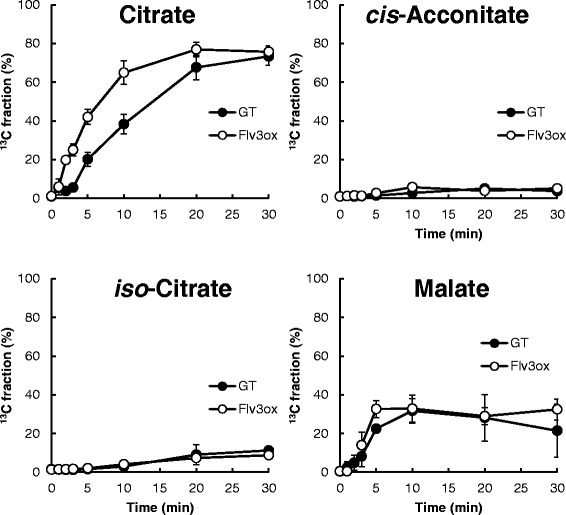

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) catalyzes the first major step of carbon fixation in the Calvin cycle to produce 3-phosphoglycerate (3PGA) from CO2 and RuBP. For Flv3ox, the 13C fraction of 3PGA reached a maximum of 92% after 20 min of labeling, whereas a maximum of 85% was observed after 30 min of labeling for GT (Figure 5). The overexpression of flv3 resulted in an increase in 13C-labeling rate of metabolites involved in the Calvin cycle, including 3PGA, fructose-6-phosphate (F6P), and sedoheptulose-7-phosphate (S7P). Flv3ox also displayed a higher turnover rate of metabolites involved in glycolysis and glycogen biosynthesis, such as phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), 2-phosphoglycerate (2PGA), acetyl-CoA (AcCoA), glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), glucose-1-phosphate (G1P), and ADP-glucose (ADP-Glc). These results clearly showed that the enhancement of flv3 expression accelerates the photosynthetic carbon assimilation rate. In addition, flv3 overexpression resulted in an increase in the turnover rate of citrate, while the 13C fraction of other metabolites involved in the citrate cycle, including cis-acconitate, isocitrate, and malate, was almost the same between Flv3ox and GT (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Time course of the 13 C fraction of metabolites involved in the citrate cycle in GT and Flv3ox cells cultivated under 120 μmol photons m -2 s -1 light intensity and 1% CO 2 conditions. The values are the mean ± SD of at least five different experiments.

Table 1 shows the pool sizes of intracellular metabolites in the two strains of cyanobacterial cells. Flv3ox accumulated 0.207 μmol g-DCW-1 ATP, while ATP level in GT was lower than the quantification limit (0.01 μmol g-DCW-1) of the CE/MS analysis. There was no significant difference in NADPH level between Flv3ox and GT. NADP+ was slightly (1.6-fold) increased by the flv3 overexpression. The levels of F6P, G6P, and S7P in Flv3ox were similar to those in GT, while an increase in 3PGA and a decrease in RuBP were caused by the flv3 overexpression. Flv3ox showed higher amounts of ADP-Glc and lower G1P than GT. 2PGA and PEP were also increased by the flv3 overexpression.

Table 1.

Metabolite pools in GT and Flv3ox cells cultivated under 120 μmol photons m -2 s -1 light intensity and 1% CO 2 conditions

| Concentration (μmol g-DCW -1 ) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metabolite | GT | Flv3ox |

| 3PGA | 2.267 ± 0.061 | 3.157 ± 0.191** |

| F6P | 0.071 ± 0.007 | 0.069 ± 0.011 |

| S7P | 0.096 ± 0.003 | 0.094 ± 0.006 |

| RuBP | 0.089 ± 0.006 | 0.026 ± 0.005** |

| G6P | 0.116 ± 0.015 | 0.138 ± 0.023 |

| G1P | 0.101 ± 0.016 | 0.020 ± 0.003** |

| ADP-Glc | 0.080 ± 0.010 | 0.115 ± 0.004** |

| PEP | 1.134 ± 0.039 | 1.562 ± 0.100** |

| 2PGA | 0.282 ± 0.008 | 0.401 ± 0.023** |

| AcCoA | 0.075 ± 0.006 | 0.075 ± 0.015 |

| ATP | < 0.01 | 0.207 ± 0.021 |

| NADPH | 0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.003 ± 0.002 |

| NADP+ | 0.495 ± 0.012 | 0.549 ± 0.021* |

Values are the mean ± SEM of nine different measurements. Statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t-test (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01).

Discussion

The overexpression of flv3 improves the cell growth of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803, as observed by the increase in the carbon assimilation rate as well as O2 evolution activity in Flv3ox cells. In Figure 5, an increase in the flux of photosynthetic carbon metabolism in Flv3ox was clearly demonstrated using a dynamic metabolic profiling approach developed by our group. So far, there has been no report that the improvement of photosynthetic CO2 incorporation was directly observed in recombinant cyanobacterial strains. When metabolism is in a dynamic steady state in vivo, metabolites are replaced with newly synthesized compounds at a constant rate, and the total amount of each metabolite remains unchanged. Thus, in order to understand metabolic flux, the turnover of metabolic intermediates should be examined directly. The measurement of metabolic turnover using this in vivo13C-labeling assay has provided conclusive evidence that CO2 incorporation is enhanced by flv3 overexpression in Synechocystis cells.

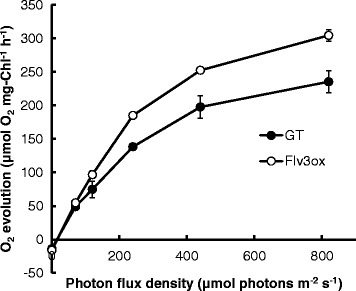

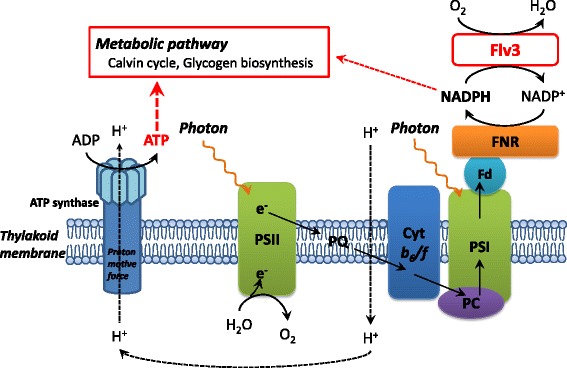

In the photosynthetic electron transport chain, electrons extracted from H2O in PSII are transferred to NADP+ to produce NADPH in PSI (Figure 7). Figure 4 demonstrated that the photosynthetic O2 evolution was improved by the enhancement of flv3 expression. Because Flv3 regenerates NADP+ with the photoreduction of O2, overexpression of flv3 in Synechocystis cells would increase photosynthetic electron transport.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the AEF and ATP synthesis in Synechocystis cells.

In general, the energy budgets of phototrophs are dependent on the ratio of protons pumped across the thylakoid membrane to electrons passed through photosynthetic electron transfer complexes, which produce ATP and NADPH used in cellular biochemical pathways [22]. CO2 fixation through the Calvin cycle is the main ATP and NADPH sink in autotrophic metabolism, requiring an ATP/NADPH ratio of 1.5, whereas the ratio generated by the LEF pathway is 1.28 [13]. AEF pathways contribute to the balancing of ATP/NADPH by supplying additional ATP [14]. For example, the Mehler reaction generates a proton gradient across the thylakoid membranes, leading to ATP generation, but the net production of reduced NADPH is not expected [16]. Although the physiological function of the Mehler reaction in cyanobacteria is not fully understood, here, increased expression of the flv3 gene in Synechocystis promoted NADP+ regeneration coupled with O2 photoreduction in the Mehler reaction, leading to a higher photosynthetic electron transport rate and increased ATP supply, as shown in Figure 4 and Table 1. Enhancement in the intracellular ATP level led to a higher ATP/NADPH ratio in the recombinant strain. The increased ATP supply would be coupled with the cell growth and improved carbon metabolic flux through the Calvin cycle, sugar phosphate pathway, and glycogen biosynthesis.

The overexpression of flv3 increased the glycogen content in Synechocystis cells (Figure 3). Glycogen, an α-1,6-branched α-1,4-glucan, is the primary storage polysaccharide in cyanobacteria and is biosynthesized from F6P via G6P, G1P, and ADP-Glc as intermediates [12]. As ADP-Glc is produced from G1P and ATP by G1P adenyltransferase, the enhanced supply of ATP by flv3 overexpression would lead to increased glycogen production. Increase in ADP-Glc and decrease in G1P by the flv3 overexpression, which are demonstrated in Table 1, would indicate enhanced conversion of G1P to ADP-Glc.

Flv1 and Flv3 are essential for photoreduction of O2 in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 [19]. Allahverdiyeva et al. reported that the growth and photosynthesis of Δflv1 and Δflv3 mutants was arrested in fluctuating light, although Flv1 and Flv3 proteins were dispensable under constant-light conditions [20]. Flv1 and Flv3 were proposed to form a heterodimer [23], while Flv3 alone is sufficient for the O2 photoreduction reaction in vitro [19]. The observed difference in the phenotypes of Δflv1 and Δflv3 mutants suggests that a homodimer of Flv3 exhibits NADPH-dependent O2 reduction in vivo under excess-light stress conditions [24]. Zhang et al. reported that flv3 transcripts were markedly higher than those of flv1 in wild-type Synechocystis under both 3% CO2 and ambient CO2 condition [25]. Our present results in an flv3-overexpressing strain of Synechocystis raise the possibility that the Flv3 protein can function alone, since overexpression of an flv3 increased the level of ATP and flux of carbon assimilation pathways.

Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 is one of the most widely used species in studies of photosynthetic bacteria because of its unicellular morphology and fully sequenced genome [26]. In addition, the natural transformability of this strain has allowed for the establishment of reliable genome manipulation techniques, which enables the easy modification of metabolic pathways. This has been followed by systems biology approaches, such as multi-omics, dynamic metabolic profiling, and flux balance analyses, for gaining insight into cellular metabolic processes [5,27]. A systems biology approach is needed to exploit cyanobacteria as cell factories for the production of fuels and commodity chemicals through metabolic engineering. Our present findings suggest that the ATP required for the synthetic pathway could potentially be supplied through an enhanced AEF pathway to further increase the efficiency of cyanobacterial cell factories.

Conclusions

Overexpression of the flv3 gene, encoding an NAD(P)H:oxygen oxidoreductase, enhanced photosynthetic electron transport and ATP supply through the regeneration of NADP+ in the recombinant Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. We also observed improvement of CO2 fixation and carbon assimilation in central metabolic pathways such as the Calvin cycle and glycogen biosynthesis in the flv3-overexpressing strain by the combination of in vivo13C-labeling of metabolites and metabolome analysis, which would be due to the enhancement in the intracellular ATP level. The flv3 overexpression improved not only the cell growth but also glycogen production in the Synechocystis, which would be a promising approach for the development of cyanobacterial biofuel production.

Methods

Strains and culture conditions

A GT strain of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 [28], an flv3-overexpressing strain (Flv3ox), and its vector control (VC) strain were grown in BG11 liquid medium [29]. Cells were pre-cultivated in 500-mL flasks containing BG11 medium in an NC350-HC plant chamber (Nippon Medical and Chemical Instruments Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) under continuous irradiation at 50 μmol white light photons m-2 s-1 and 0.04% (v/v) CO2 condition with 100-rpm agitation at 30°C. Cultivation was performed in a closed double-deck flask, which had a first stage containing 50 mL of 2 M NaHCO3/Na2CO3 buffer with the appropriate pH to obtain the desired CO2 concentration of 1% (v/v), and a second stage containing 70 mL BG11 culture medium [30,31]. Pre-cultured cells were inoculated into the fresh BG11 medium at a biomass concentration of 1.26 mg DCW L-1 (the optical density at 750 nm [OD750] was 0.04) and cultivated under continuous irradiation at 50 or 120 μmol white light photons m-2 s-1 and 1% (v/v) CO2 with 100-rpm agitation at 30°C. Light intensity was measured in the middle of the medium using an LI-250A light meter equipped with an LI-190SA quantum sensor (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). Cell density in the medium was determined as DCW, as a linear correlation was observed between DCW and optical density measured at OD750 using a UV mini spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto Japan). For plate cultures, BG-11 was solidified using 1.5% (w/v) agar (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and incubated in air at 30°C under continuous white light irradiation (50 to 70 μmol photons m-2 s-1).

Construction of recombinant strains

The flv3 (sll0550) coding region was amplified from Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 genomic DNA by PCR using the primer set 5′-GGAATTATAACCATAATGTTCACTACCCCCCTCCC-3′ and 5′-GGCATGGAGGACATATTAGTAATAATTGCCGACTT-3′. The resulting 1.7-kb fragment was integrated into NdeI-digested pTCP2031V [32] using an In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) to yield pTCP2031-flv3. The GT strain was transformed with pTCP2031V-flv3 using a previously described method [33] to yield strain Flv3ox. Also, the plasmid pTCP2031V was introduced into the GT strain to yield the VC strain. Colonies resistant to 34 μg mL-1 chloramphenicol were selected, and isolation of a single colony was repeated three times. The chromosomal integration of flv3 and plasmid-derived sequence was confirmed by PCR using the specific primers, Pr1 (5′-GGTAGTGGGCAATGCTGTAGAACAAGCGTTTGAGC-3′) and Pr2 (5′-CGGTAATTCTTGGCGCAATTGACGGTCAAAATAAC-3′). pTCP2031V was a kind gift from Professor M. Ikeuchi (University of Tokyo, Japan).

Immunoblot analysis

Cellular proteins were extracted from 1.6 mg DCW Synechocystis cells with 50 μL of 5% lithium lauryl sulfate containing 75 mM dithiothreitol by sonication in a Biorupter UCD-200 bath sonicator (Cosmo Bio, Tokyo, Japan). After centrifugation of the mixture at 15,000 g for 5 min at 4°C, 10 μL of the extracts were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 12% and 18% polyacrylamide/6 M urea gels in a Tris/MES system [34]. After electrophoresis, proteins separated on the 12% gel were blotted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane, reacted with rabbit anti-Flv3 antibody, which was kindly provided by Dr. H. Yamamoto (Kyoto University, Japan), and visualized with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium after incubation with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG antibody (Promega, Madison, WI). Proteins separated on the 18% gel were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan). Protein concentrations were determined by using the QuantiPro BCA assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Metabolite analysis

Cyanobacterial cells equivalent to 5 mg DCW were collected from the cultivation flasks and immediately filtered using 1-μm pore size polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) filter disks (Omnipore; Millipore, Billerica, MA). After washing the filter disks with 20 mM ammonium carbonate pre-chilled to 4°C, the cells retained on the filters were immediately placed into 2 mL pre-cooled (-30°C) methanol containing 37.38 μM L-methionine sulfone and 37.38 μM piperazine-1,4-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) as internal standards for mass analysis. Intracellular metabolites were extracted according to a previously reported method [21], with minor modification. The cells were suspended by vortexing, and then 0.5 mL of the cell suspension was mixed with 0.2 mL of pre-cooled (4°C) water and 0.5 mL of chloroform. After vortexing for 30 s, phase separation of aqueous and organic layers was performed by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. 500 μL of the aqueous layer was filtered with a Millipore 5 kDa cut-off membrane for the removal of solubilized proteins. After evaporation of the aqueous-layer extracts under vacuum using a FreeZone 2.5 Plus freeze dry system (Labconco, Kansas City, MO), the dried metabolites were dissolved in 20 μL of Milli-Q water. The metabolites were analyzed using a CE/MS system (CE, Agilent G7100; MS, Agilent G6224AA LC/MSD TOF; Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) controlled by MassHunter Workstation Data Acquisition software (Agilent Technologies), as described previously [21].

13C-labeling experiment

To analyze metabolic turnover in cyanobacteria, in vivo13C-labeling was performed according to a previously reported method [21]. Briefly, Synechocystis cells were cultivated in BG11 medium under 120 μmol photons m-2 s-1 light intensity and 1% (v/v) CO2 conditions at 30°C. When the OD750 reached approximately 4.5, 5 mg DCW of cells were filtered and resuspended at an OD750 of 1.0 in BG11 medium containing 25 mM NaH13CO3. After labeling for 1 to 30 min, cells were collected by filtration and processed as described for the metabolite analysis. Extracted intracellular metabolites were analyzed using CE/MS. Mass spectral peaks of biological origin were identified manually by searching for mass shifts between the 12C and 13C mass spectra.

The 13C fraction of metabolites was calculated as described previously [35]. The relative isotopomer abundance (mi) for each metabolite in which i13C atoms are incorporated is calculated by the following equation:

where Mi represents the isotopomer abundance for each metabolite in which i13C atoms are incorporated.

The 13C fraction of the metabolite possessing n carbon atoms is calculated by the following:

Glycogen measurement

When the OD750 of Synechocystis cultures reached approximately 4.5, cells were harvested using PTFE filter disks, as described above. After washing the filters with 20 mM ammonium carbonate, the cells on the filter were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then freeze-dried using a Labconco freeze dryer. After glycogen was extracted from the cells, the glycogen content was determined by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Shimadzu) using a size-exclusion HPLC column (OHpak SB-806 M HQ; Shodex, Tokyo, Japan) and reflective index detector (RID-10A; Shimadzu), as described previously [36].

Photosynthesis analysis

Oxygen exchange was monitored with an oxygen electrode (Hansatech, King’s Lynn, UK). For the measurement, a reaction mixture (2 mL) containing 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.6), 10 mM NaHCO3 and an arbitrary amount of cells (10 μg chlorophyll mL-1) was first incubated in the dark for 10 min under air-equilibrated conditions and was then illuminated with actinic light (red light of wavelength >640 nm) at the indicated light intensity at 25°C. During the measurements, the reaction mixture was mixed with a magnetically controlled micro-stirrer.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Chikako Aoki for technical assistance. We also thank Dr. Hiroshi Yamamoto (Kyoto University) for the kind gift of the anti-Flv3 antibody and Professor Masahiko Ikeuchi (University of Tokyo) for providing pTCP2031V. This work was supported by the Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology (PRESTO) program of the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

Abbreviations

- AcCoA

acetyl-CoA

- ADP-Glc

ADP-glucose

- AEF

alternative electron flow

- CE

capillary electrophoresis

- DCW

dry cell weight

- Flv

flavodiiron

- F6P

fructose-6-phosphate

- G1P

glucose-1-phosphate

- G6P

glucose-6-phosphate

- GT

glucose-tolerant

- LEF

linear electron flow

- MS

mass spectrometry

- PEP

phosphoenolpyruvate

- 2PGA

2-phosphoglycerate

- 3PGA

3-phosphoglycerate

- PTFE

polytetrafluoroethylene

- RuBP

ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate

- S7P

sedoheptulose-7-phosphate

- VC

vector control

- WWC

water-water cycle

Additional file

Concentration of cellular biomass cultivated under 120 μmol photons m -2 s -1 light intensity and 1% CO 2 conditions. Difference in biomass concentration was statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA. A post hoc Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference test was carried out on the grouped means. Values are the averages from measurements of ten different cell cultures, ±SD. Values followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P > 0.01).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TH supervised the research and drafted the manuscript. MM carried out the cultivation of recombinant strains, the metabolite analysis, the 13C-labeling experiment, and the glycogen measurement. YS participated in the strain cultivation and glycogen measurement. SA carried out the immunoblot analysis. MT constructed the recombinant strains. GS carried out the photosynthesis analysis. CM assisted in drafting the manuscript. AK supervised the research. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Tomohisa Hasunuma, Email: hasunuma@port.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Mami Matsuda, Email: matsuda_mami@harbor.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Youhei Senga, Email: y.senga@people.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Shimpei Aikawa, Email: saikawa@buffalo.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Masakazu Toyoshima, Email: toyo104@penguin.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Ginga Shimakawa, Email: 132a509a@stu.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Chikahiro Miyake, Email: cmiyake@hawk.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Akihiko Kondo, Email: akondo@kobe-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Ragauskas AJ, Williams CK, Davison BH, Britovsek G, Cairney J, Eckert CA, Frederick WJ, Jr, Hallett JP, Leak DJ, Liotta CL, Mielenz JR, Murphy R, Templer R, Tschaplinski T. The path forward for biofuels and biomaterials. Science. 2006;311:484–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1114736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kopetz H. Renewable resources: build a biomass energy market. Nature. 2013;494:29–31. doi: 10.1038/494029a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dismukes GC, Carrieri D, Bennette N, Ananyev GM, Posewitz MC. Aquatic phototrophs: efficient alternatives to land-based crops for biofuels. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mussatto SI, Dragone G, Guimarães PM, Silva JP, Carneiro LM, Roberto IC, Vicente A, Domingues L, Teixeira JA. Technological trends, global market, and challenges of bio-ethanol production. Biotechnol Adv. 2010;28:817–830. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wijffels RH, Kruse O, Hellingwerf KJ. Potential of industrial biotechnology with cyanobacteria and eukaryotic microalgae. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quintana N, van der Kooy F, van de Rhee MD, Voshol GP, Verpoorte R. Renewable energy from Cyanobacteria: energy production optimization by metabolic pathway engineering. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;91:471–490. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3394-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aikawa S, Joseph A, Yamada R, Izumi Y, Yamagishi T, Matsuda F, Kawai H, Chang JS, Hasunuma T, Kondo A. Direct conversion of Spirulina to ethanol without pretreatment or enzymatic hydrolysis process. Energy Environ Sci. 2013;6:1844–1849. doi: 10.1039/c3ee40305j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aikawa S, Nishida A, Ho S-H, Chang JS, Hasunuma T, Kondo A. Glycogen production for biofuels by the euryhaline cyanobacteria Synechococcus sp strain PCC 7002 from an oceanic environment. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2014;7:88. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-7-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price GD, Badger MR, Wodger FJ, Long BM. Advances in understanding the cyanobacterial CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM): functional components, Ci transporters, diversity, genetic regulation and prospects for engineering into plants. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:1441–1461. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price GD. Inorganic carbon transporters of the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism. Photosynth Res. 2011;109:47–57. doi: 10.1007/s11120-010-9608-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raven JA, Giordano M, Beardall J, Maberly SC. Algal evolution in relation to atmospheric CO2: carboxylases, carbon-concentrating mechanisms and carbon oxidation cycles. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367:493–507. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ball SG, Morell MK. From bacterial glycogen to starch: understanding the biogenesis of the plant starch granule. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2003;54:207–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer DM, Evans JR. The importance of energy balance in improving photosynthetic productivity. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:70–78. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.166652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nogales J, Gudmundsson S, Knight EM, Palsson BO, Thiele I. Detailing the optimality of photosynthesis in cyanobacteria through systems biology analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;109:2678–2683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117907109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehler AH. Studies on reactions of illuminated chloroplasts. I. Mechanism of the reduction of oxygen and other Hill reagents. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1951;33:65–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(51)90082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asada K. The water-water cycle in chloroplasts: scavenging of active oxygens and dissipation of excess photons. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:601–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyake C. Alternative electron flows (water-water cycle and cyclic electron flow around PSI) in photosynthesis: molecular mechanisms and physiological functions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:1951–1963. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vincente JB, Gomes CM, Wasserfallen A, Teixeira M. Module fusion in A-type flavoprotein from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis condenses a multiple-component pathway in a single polypeptide chain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:82–87. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helman Y, Tchernov D, Reinhold L, Shibata M, Ogawa T, Schwarz R, Ohad I, Kaplan A. Genes encoding A-type flavoproteins are essential for photoreduction of O2 in cyanobacteria. Curr Biol. 2003;13:230–235. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allahverdiyeva Y, Mustila H, Ermakova M, Bersanini L, Richaud P, Ajlani G, Battchikova N, Cournac L, Aro EM. Flavodiiron proteins Flv1 and Flv3 enable cyanobacterial growth and photosynthesis under fluctuating light. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4111–4116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221194110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasunuma T, Kikuyama F, Matsuda M, Aikawa S, Izumi Y, Kondo A. Dynamic metabolic profiling of cyanobacterial glycogen biosynthesis under conditions of nitrate depletion. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:2943–2954. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sacksteder CA, Kanazawa A, Jacoby ME, Kramer DM. The proton to electron stoichiometry of steady-state photosynthesis in living plants: A proton pumping Q cycle is continuously engaged. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14283–14288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allahverdiyeva Y, Ermakova M, Eisenhut M, Zhang P, Richaud P, Hagemann M, Cournac L, Aro EM. Interplay between flavodiiron proteins and photorespiration in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:24007–24014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.223289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hackenberg C, Engelhardt A, Matthijs HC, Wittink F, Bauwe H, Kaplan A, Hagemann M. Photorespiratory 2-phosphoglycolate metabolism and photoreduction of O2 cooperate in high-light acclimation of Synechocystis sp strain PCC 6803. Planta. 2009;230:625–637. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-0972-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang P, Allahverdiyeva Y, Eisenhut M, Aro EM. Flavodiiron proteins in oxygenic photosynthetic organisms: photoprotection of photosystem II by Flv2 and Flv4 in Synechocystis sp PCC6803. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding region. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Grady J, Schwender J, Shachar-Hill Y, Morgan JA. Metabolic cartography: experimental quantification of metabolic fluxes from isotopic labeling studies. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:2293–2308. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams JGK. Construction of specific mutations in photosystem II photosynthetic reaction center by genetic engineering methods in Synechocystis 6803. Methods Enzymol. 1988;167:766–778. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)67088-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury JB, Herdman M, Stanier RY. Generic assignments, strains histories and properties of pure culture of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. doi: 10.1099/00221287-111-1-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flores E, Romero JM, Guerrero MG, Losada M. Regulatory interaction of photosynthetic nitrate utilization and carbon dioxide fixation in the cyanobacterium Anacystis nidulans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;725:529–532. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(83)90193-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng Y, Ye J, Mi H. Effects of low CO2 on NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, a mediator of cyclic electron transport around photosystem I in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:534–540. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horiuchi M, Nakamura K, Kojima K, Nishiyama Y, Hatakeyama W, Hisabori T, Hihara Y. The PedR transctiptional regulator interacts with thioredoxin to connect photosynthesis with gene expression in cyanobacteria. Biochem J. 2010;431:135–140. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osanai T, Oikawa A, Azuma M, Tanaka K, Saito K, Hirai MY, Ikeuchi M. Genetic engineering of group 2 σ factor SigE widely activates expression of sugar catabolic genes in Synechocystis species PCC 6803. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30962–30971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.231183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kashino Y, Koike H, Satoh K. An improved sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis system for the analysis of membrane protein complexes. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:1004–1007. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683()22:6<1004::AID-ELPS1004>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasunuma T, Harada K, Miyazawa S, Kondo A, Fukusaki E, Miyake C. Metabolic turnover analysis by a combination of in vivo13C-labeling from 13CO2 and metabolic profiling with CE-MS/MS reveals rate-limiting steps of the C3 photosynthetic pathway in Nicotiana tabacum leaves. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:1041–1051. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Izumi Y, Aikawa S, Matsuda F, Hasunuma T, Kondo A. Aqueous size-exclusion chromatographic method for the quantification of cyanobacterial native glycogen. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2013;930:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]