Abstract

There is widespread agreement that stakeholders should be included in the problem-formulation phase of addressing environment problems and, more recently, there have been attempts to include stakeholders in other phases of environmental research. However, there are few studies that evaluate the effects of including stakeholders in all phases of research aimed at solving environmental problems. Three underground nuclear blasts were detonated on Amchitka Island from 1965 to 1971. Considerable controversy developed when the Department of Energy (DOE) decided to “close” Amchitka. Concerns were voiced by subsistence Aleuts living in the region, resource trustees, and the State of Alaska, among others. This article evaluates perceptions of residents of three Aleutian village before (2003) and after (2005) the Consortium for Risk Evaluation with Stakeholder Participation’s (CRESP) Amchitka Independent Science Assessment (AISA). The CRESP AISA provided technical information on radionuclide levels in biota to inform questions of seafood safety and food chain health. CRESP used the questions asked at public meetings in the Aleut communities of Atka, Nikolski, and Unalaska to evaluate attitudes and perceptions before and after the AISA. Major concerns before the AISA were credibility/trust of CRESP and the DOE, and information about biological methodology of the study. Following the AISA, people were most concerned about health effects and risk reduction, and trust issues with CRESP declined while those for the DOE remained stable. People’s relative concerns about radionuclides declined, while their concerns about mercury (not addressed in the AISA) increased, and interest in ecological issues (population changes of local species) and the future (continued biomonitoring) increased from 2003 to 2005. These results suggest that questions posed at public meetings can be used to evaluate changes in attitudes and perceptions following environmental research, and the results are consistent with the hypothesis that the AISA answered questions about radionuclides, and lowered overall concern about radionuclides, but left unanswered concerns about the health effects of mercury.

Keywords: Aleuts, mercury, radionuclides, stakeholder-driven research, stakeholders, subsistence

1. INTRODUCTION

Increasingly, scientists, managers, and public policymakers are faced with solving complicated environmental problems that are contentious.(1) Often, parties have relied on risk assessment as the basis for decisions. This paradigm, used for estimating the risk to both human and ecological receptors, includes problem formulation, hazard identification, dose response, exposure assessment, and risk characterization.(2,3) More recently, however, a critical component of successful public policy and management has been the involvement of stakeholders in decisions.(4,5) These organizations recommended the inclusion of stakeholders in all phases of the problem-solving and management process; stakeholders become important aspects of management or remediation.(6) However, interested and affected parties usually have had little or no input into the design or execution of studies that examine the potential human and ecological effects of facilities, remediation, or other stressors. When stakeholders have been involved, it is usually in the problem-formulation phase. Moreover, in the past, scientists and policymakers often assumed that simply understanding stakeholders’ perceptions or views is sufficient stakeholder involvement,(7) or that imparting scientific knowledge to the public should be sufficient to improve public perceptions. Darnall and Jolley(8) recently suggested that public participation is less effective when there is a shortage of technical data.

Stakeholder involvement has often been limited to the examination of public perceptions about an environmental problem, but there are many ways to organize communication with interested and affected parties, and to evaluate such interactions.(9–11) Public attitudes have frequently been solicited about the siting and storage of chemical plants, nuclear facilities, and hazardous waste sites.(12–17) In general, scientists view the risks from such facilities as less severe than does the general public.(18) Further, there is a negative correlation between perceived risks and perceived benefits,(19) suggesting that understanding the public’s concerns or fears is not enough to change perceptions. No less important is the realization that the risk assessment process has not led to “peace of mind” on the part of affected stakeholders about chemical or radiological risks.(20)

While there is a general consensus that stakeholders should be involved in the problem-formulation phase, and to some extent in other aspects of risk assessment and management, there are few studies that have evaluated the effects of science assessments, remediation/restoration, or management on stakeholder perceptions and attitudes. The question arises as to whether stakeholder involvement in the process changes perceptions and attitudes. This question can be answered only under the following conditions: (1) stakeholders are involved from the beginning of the process, and throughout the process, (2) perceptions and attitudes are recorded before and after the management or environmental process, and (3) the perceptions can be compared qualitatively or quantitatively.

In this article the attitudes and perceptions of Aleut stakeholders are compared before (2003) and after (2005) the Amchitka Independent Science Assessment (AISA) was conducted (2004). The AISA was designed and executed by the Consortium for Risk Evaluation with Stakeholder Participation (CRESP) at the request of the State of Alaska and the Department of Energy (DOE) to provide the science necessary to understand whether subsistence and commercial marine organisms from Amchitka waters were safe to eat, to understand risk to the food chain, and to provide information on radionuclide levels in biota that could serve as a basis for a long-term biomonitoring plan at Amchitka. Amchitka was the site of three underground nuclear tests from 1965 to 1971. While no one currently lives on Amchitka Island, there are subsistence Aleut communities on the nearby islands of Adak, Atka, Umnak (Nikolski), and Unalaska in the Aleutian Chain of Alaska. Aside from issues of environmental justice(21,22) that involve the potential disproportionate exposure of Aleuts to radionuclides via their subsistence foods, the Aleuts are also committed to protection of the marine ecosystem.

Particular interests for the study included: (1) whether Aleuts were concerned about radionuclides or other contaminants, (2) whether attitudes and perceptions changed from 2003 to 2005, and (3) what the nature of the changes were with respect to contaminants, trust and credibility, health effects, and risk perception. The questions raised at public meetings held in three Aleut communities (Atka, Nikolski, Unalaska) were used as the database, and comparisons were made among questions asked before and after the AISA. The content of questions was examined to determine whether the types of questions asked differed from 2003 to 2005. This method of assessing perceptions and attitudes has the advantage of being spontaneous and not requiring long and lengthy questionnaires that Aleuts might refuse to answer, while providing a direct indication of their concerns and interests. The initial premise was that while people might ask more questions in 2005 than 2003 because they had become familiar with us as visitors, the nature of the questions should remain the same unless the AISA itself had effected a change in attitudes and perceptions. Thus, the null hypothesis is tested that there would be no change in concerns and perceptions from 2003 to 2005; the evaluation was thus of outcome.(10)

Since one of the main objectives of the AISA was assessing whether the subsistence foods were safe with respect to radionuclides, one might predict that Aleuts would have fewer questions about radionuclides after the study than before. No such changes were expected for other contaminants that we did not measure (such as mercury or PCBs). We also predicted that people might be more interested in health effects in 2005 than in 2003 because we had discussed these issues with them. Particular interests explored in this study include determining whether trust and credibility remained the same in both years with respect to CRESP (conducting the assessment) and DOE (responsible for the radionuclides at Amchitka). CRESP made it clear that DOE was funding the study, but that CRESP scientists were not a part of DOE.

2. BACKGROUND ON AMCHITKA AND DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY

During and after World War II, DOE and its antecedents (Atomic Energy Commission, Energy Research and Development Administration) obtained many tracts of land for the purpose of developing, producing, and testing nuclear weapons. With the ending of the Cold War (ca 1989), the DOE redefined its mission as environmental remediation and restoration, including the protection of environmental resources and biodiversity.(23–25) Nuclear weapons production ended abruptly in 1989, and the DOE established an Office of Environmental Management (EM) to deal with the remediation tasks on their facilities.(26) Since then, characterization, cleanup, and remediation of contaminated sites have been a national priority in the United States and elsewhere, within a framework of protecting humans and the environment, now and in the future.(27) Amchitka Island was one of the DOE sites slated for “closure” (i.e., completion of environmental management) in the fall of 2006, and in 2006 it was moved to the Office of Legacy Management.

Three underground nuclear tests were detonated on Amchitka Island (51°N lat; 179°E long) from 1965 to 1971. Amchitka Island is unusual among DOE-contaminated sites because of its combination of remoteness, depth below ground surface of the contamination, and the importance of its ecological resources and seafood productivity that could be at risk if there were significant seepage of radionuclides from the underground test cavities to the marine environment. It is believed by scientists that most of the radioactive material from the Amchitka test shots is trapped in the vitrified matrix created by the intense heat of the blast, and is therefore permanently immobilized. This, however, is only an assumption, and some model results indicate that breakthrough of radionuclides into the marine environment will eventually occur.(28,29) The DOE recognized the importance of including stakeholders in its decision-making process,(23) but has still fallen short of achieving this goal.(30,31) At the start of the AISA project, considerable controversy surrounded the initial tests, potential risks from radionuclide seepage, and closure of the site.(32,33)

Amchitka Island is part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge system under the aegis of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS). It contains important ecological resources,(34,35) some of which are important subsistence food.

3. METHODS

3.1. Study Areas

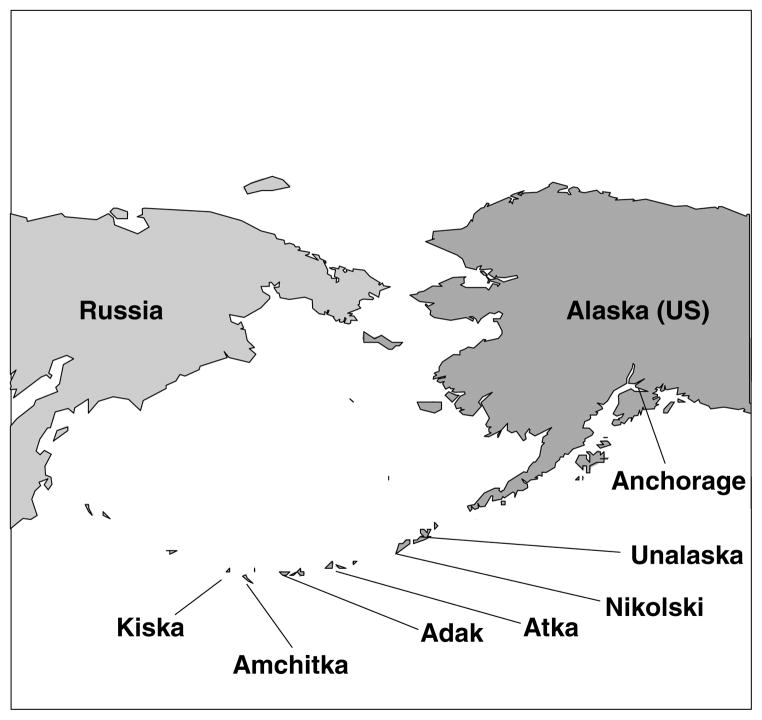

This study is based on the questions asked by Aleuts living in the Aleutian villages of Atka, Nikolski, and Unalaska at public meetings during which CRESP discussed the AISA plan (2003) and results (2005). These islands (Fig. 1) are approximately 1,280–1,800 km west of the tip of the Alaskan Peninsula. Atka (population ca 85–100) and Nikolski (population ca 30–35) are small Aleut villages without any large commercial enterprises, while Unalaska (Aleut population ca 250) and adjacent Dutch Harbor have large commercial fish and shellfish processing plants. Dutch Harbor has had the most commercial fish landings in the world for several years.(36) The full Science Plan served as the initial basis for the project.(37)

Fig. 1.

Map showing the locations of Amchitka, Adak, Atka, Kiska, Nikolski, and Unalaska in the Aleutian Chain of Alaska. Underground nuclear tests were on Amchitka.

3.2. Protocol

As part of the AISA the Aleut communities of Atka, Nikolski, and Unalaska were visited before initiation of the Amchitka expedition to collect biota for radionuclide analysis and again after the expedition to discuss the final results. Public meetings were also held at Adak before the expedition, but Adak could not be visited after and so the “before” data have not been included, although they were similar. On each visit public meetings were held with elders (all three communities) and youth (all but Unalaska) in the tribal/corporation community centers or schools. These meetings were publicly announced by the tribal/corporation officials putting out the word on their community radio waves, by fax, and by word of mouth. The meetings were advertised by more traditional means, including notices in the paper (Unalaska), over radio, and TV (Unalaska), postings at grocery stores and post offices (all three), and by personal visits to community and tribal leaders (all three). Because of the respect held for elders and adults within their communities, children and teenagers normally would not attend their meetings and certainly would not speak. Therefore, separate meetings were held with school-age youths in Atka and Nikolski. Attendance was high, up to 85% in the small communities.

In the meetings in 2003 the AISA was presented and questions and suggestions were solicited. In 2005 the radionuclide results from the biota collected on the expedition in the summer of 2004 were presented, and again people were asked if there were questions or suggestions about interpretation, impact, or further studies. The duration of all meetings was about the same (about 90 minutes) and the meeting continued as long as there were questions. All questions were recorded and, in essence, this study is a content analysis of public meetings, similar to the approach of Vining and Tyler(38) on written public comments.

The unit of analysis used for content code development was the questions asked during the public meetings. To develop a content taxonomy we combined questions that seemed to be similar. That is, questions such as “Is radiation bad for me?” and “Will radiation hurt me” were considered to be the same question; similarly, “How is radiation bad for me?” was considered similar to “What does the radiation do to me?”

All questions were independently assigned to one of nine categories by the authors, with a high degree of agreement. Categories included Contaminants (definitions of), Health Effects, Risk Reduction, Trust/Credibility of CRESP, Trust/Credibility of DOE, Biological Methods (and approaches taken for the expedition), Ecological Issues, the Future, and Geophysical Issues. The only questions where there was disagreement dealt with “Will you come back to tell us your results.” These questions were ultimately assigned to the Trust/Credibility of CRESP category, but one of us initially assigned them to the Future category. While one might combine the biological methods and ecological concerns, they were considered distinct because the biological questions dealt with the collection of biota for analysis, while the ecological questions dealt with why a given species had declined or the definition of ecological concepts (e.g., trophic level, predator/prey). A sample of Aleut questions, in their own words, is presented in Table I.

Table I.

Sample Comments of Aleuts in Public Meetings Before and After the AISA

| Before the Independent Assessment from Elders (2003) |

| What about our foods here in Nikolski? |

| How can you test subsistence foods if you don’t have our hunters with you? |

| Are you going to collect Sea Lions and Seals? |

| Are you going to collect Halibut, Salmon, Pogies, Gumboots? |

| What about mercury? I’m more interested in mercury than radiation. |

| What about lead? |

| Who actually wrote the plan? |

| Do you work for DOE? |

| Who is paying you, and how do I know you won’t just say what they want? |

| How can we trust DOE to pay for the study? The don’t really want to know. |

| How can we trust DOE to let you do the study? |

| If you find radionuclides, will DOE let you tell us? |

| What happens when your project is done? |

| Why aren’t you collecting fish from Atka or Adak, that’s what we eat? |

| Who made up the plan, we didn’t approve it? |

| Who is paying you? |

| Before the Independent Assessment from Youth (2003) |

| What is radiation? |

| Can it hurt us here? |

| What about radiation in our Halibut? What about the Sea Urchins? |

| What radiation is in birds—I shoot a lot of ducks? |

| Is it safe to eat pogie eggs, I eat them raw? |

| Can I shoot the little birds on the beach? |

| What can the government do if it is leaking? Will it hurt us here? |

| Why did they do the tests here, we didn’t do anything? |

| Is the government out to get us again? |

| After the Assessment from Elders (2005) |

| What are the levels of radionuclides that cause health effects? |

| What are the bad [health] effects of radionuclides? |

| What about mercury? I’m still interested in that. |

| What are the bad [health] effects of mercury? |

| What levels of mercury are in our fish? |

| What should I avoid to have less mercury? |

| Why have our puffins and sea otters decreased? There used to be many more, especially when I was a kid. |

| What happened to our duck numbers? There used to be plenty Mallards to shoot. |

| What would happen if there was an earthquake? We have a lot out here. |

| How will we know if something changes? |

| Will you continue with this study? |

| How can we trust DOE to continue your work? |

| What about a volcano? |

| How can we trust DOE if you don’t come back? |

| What about razor clams and soft-shell clams. There aren’t as many as there used to be? |

| Where are all the ducks? When I was a kid there used to be a lot, now there are none. Mallards used to be all over the place, good eating too. |

| We are concerned about mercury, didn’t you do mercury? |

| What about mercury? Does my pregnant grand-daughter need to worry? |

| Should I tell my daughter to avoid some fish because of mercury even though she’s not pregnant yet? |

| How can I make it so I’m not affected by mercury? |

| What were the levels in gull eggs? Of course, we don’t eat many gull eggs from Unalaska, but we have relatives that do, out in the villages. What should we tell them? |

| After the Assessment from Youth (2005) |

| Where did you live out there? Were you cold? |

| What about Dan and Ron? What did they do? |

| Did you get sea sick? |

| Did you collect kelp? I eat them sometimes. |

| What did you eat? Did you fish or kill birds? |

| Does anyone live there? |

| Why did my people leave Amchitka? |

| Can we see pictures of fishing? of the hunt? |

| Are fish bad for me? |

| What is trophic level? |

| What predators are there? |

| Are radionuclides bad for me? |

| We heard about mercury, did you do that? |

| How many fish did you catch? |

| What’s a contaminant? |

| Do we have contaminants here? |

| How did they [contaminants] get here? |

| Will you come back? Maybe next summer? |

| If you don’t come, who will make sure our foods are safe? who will? |

| What happened to all the ducks, I used to shoot ducks, now they are all gone. |

Note: Meetings were held at Nikolski, Atka, and Unalaska.

The data are presented as the questions asked by category, the percent of questions that fit into each category by year, and the percent change in a particular type of question from 2003 to 2005. Contingency table and goodness of fit X2 tests are used to test differences among categories, except for small sample sizes, where a Fisher exact test was used.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Relative Importance of Issues

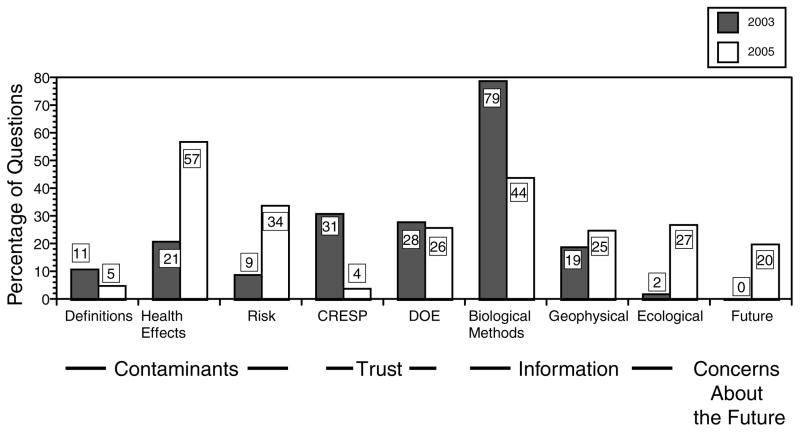

In the three Aleut villages there were 199 discrete questions asked in 2003, and 242 questions asked in 2005 (Table II). Questions mainly dealt with health effects and risks, trust and credibility, biological methods, ecological issues, geophysical issues, and the future. In 2003, questions mainly dealt with the credibility and trust of CRESP and DOE, and the biological methods for the study. In 2005, questions mainly dealt with health effects and risk, and biological methods/results (Fig. 2). There were significant differences among categories from 2003 and 2005 (contingency X2 = 105, df = 8, p < 0.0001), rejecting the null hypothesis of no relative change from 2003 to 2005. Several features are noticeable: (1) questions about health effects and health risks increased sharply from 2003 to 2005, (2) questions about CRESP trust and credibility and about biological methods decreased sharply, and (3) questions about ecological issues and the future each increased from almost zero to 10% of all questions.

Table II.

Comparison of Number of Questions Asked Before (2003) and After (2005) the Amchitka Independent Science Assessment in the Aleut Villages of Nikolski, Atka, and Unalaska

| Questions | Nikolski Elders | Nikolski Youth | Atka Elders | Atka Youth | Unalaska | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contaminants | ||||||

| What is radiation? | 2–0 | 3–1 | 5–1 | |||

| What is mercury? | 2–1 | 2–2 | 4–3 | |||

| What is a contaminant | 1 | 1–1 | 2–1 | |||

| Health Effects | ||||||

| Is mercury bad? | 1–2 | 1–2 | 2–4 | |||

| At what level is mercury bad? | 1–2 | 0–2 | 1–3 | 2–7 | ||

| How is mercury bad for us? | 1–3 | 0–1 | 1–2 | 0–2 | 1–2 | 3–10 |

| Is radiation bad? for us? | 2–1 | 2–0 | 4–1 | |||

| What levels of radiation are bad? | 0–1 | 0–2 | 1–3 | 1–6 | ||

| How is radiation bad for us? | 0–1 | 2–2 | 0–1 | 0–2 | 2–6 | |

| Is it safe to eat the village foods? | 2–3 | 1–2 | 2–3 | 1–2 | 1–3 | 7–13 |

| Is radiation high enough to hurt us? | 0–2 | 0–1 | 1–3 | 0–2 | 0–2 | 0–10 |

| Risk Reduction | ||||||

| How can I reduce the bad effects of mercury? | 1–2 | 0–1 | 1–3 | 0–2 | 2–8 | |

| How can I lower the bad effects of radiation? | 1–1 | 1–0 | 2–1 | |||

| What fish can I eat to have less mercury? | 0–3 | 0–1 | 0–2 | 1–2 | 1–8 | |

| What fish or shellfish can I eat that are best for me? Are fish bad for me? | 1–2 | 0–2 | 2–3 | 0–1 | 1–2 | 4–9 |

| Should I tell my pregnant (or to be pregnant) daughter to avoid some fish because of mercury? | 0–2 | 0–4 | 0–2 | 0–8 | ||

| Trust/Credibility: CRESP | ||||||

| Who is CRESP? Who wrote the plan? | 2–0 | 1–0 | 1–0 | 1–0 | 3–1 | 8–1 |

| Who asked you to do the plan? | 1–0 | 2–0 | 3–0 | |||

| Who paid for it? How do I know you are independent? | 4–0 | 1–0 | 2–0 | 1–1 | 4–1 | 12–2 |

| Will you come back to tell us your results? | 2–0 | 1–0 | 2–0 | 3–1 | 8–1 | |

| Trust/Credibility: Government or DOE | ||||||

| How can we be sure they will test our foods in future? | 0–2 | 0–1 | 0–1 | 0–2 | 0–6 | |

| How can we trust DOE to know if the foods are safe? | 0–2 | 0–1 | 0–1 | 2–2 | 2–4 | |

| How can we believe what DOE says? | 3–2 | 2–2 | 3–2 | 8–6 | ||

| How can we trust DOE to fund your study? | 1–1 | 1–0 | 1–0 | 3–1 | ||

| How do we know DOE will let you tell us if you find radioactivity? | 2–0 | 1–0 | 2–0 | 3–0 | 8–0 | |

| How can we trust DOE to do a monitoring plan in the future? | 0–3 | 0–2 | 0–2 | 0–7 | ||

| Why did they do the tests here? Is the government out to get us? | 1–0 | 3–0 | 1–1 | 1–0 | 1–1 | 7–2 |

| Biological Methods | ||||||

| Why not test foods from here or Adak? | 2–0 | 2–0 | 3–1 | 1–0 | 4–3 | 12–4 |

| How can you test subsistence foods without Aleuts? | 3–0 | 2–0 | 2–0 | 3–0 | 10–0 | |

| Will You/Did You Analyze for? | ||||||

| Halibut | 1–0 | 1–0 | 1–0 | 1–0 | 1–0 | 5–0 |

| Salmon & eggs | 1–1 | 1–0 | 2–1 | |||

| Pogies & eggs | 1–1 | 1–1 | 1–0 | 1–0 | 4–2 | |

| Octopus | 1–0 | 2–0 | 2–0 | 5–0 | ||

| Sea Lion & liver | 1–0 | 1–0 | 2–2 | 1–1 | 1–0 | 6–3 |

| Seal | 1–0 | 1–0 | ||||

| Kelp | 2–1 | 1–1 | 1–1 | 4–3 | ||

| Ducks | 1–0 | 1–0 | 2–0 | |||

| Chitons/Katys | 1–0 | 1–1 | 1–1 | 3–2 | ||

| Gull eggs | 1–0 | 1–0 | 1–0 | 1–0 | 4–0 | |

| Sea Urchin & eggs | 1–0 | 1–0 | 2–0 | |||

| Will/Did You Analyze for? | ||||||

| Mercury? | 2–3 | 1–2 | 3–4 | 1–2 | 3–3 | 10–14 |

| Lead? | 1–0 | 1–0 | ||||

| PCBs? | 0–1 | 0–1 | 0–2 | |||

| Where did you live? What did you eat? | 0–3 | 1–3 | 1–6 | |||

| How many of this species will/did you collect? | 0–3 | 0–2 | 0–5 | |||

| Ecological | ||||||

| Why Are These Declining? | ||||||

| Ducks | 0–2 | 0–1 | 1–2 | 0–1 | 1–6 | |

| Mallards | 0–1 | 0–1 | 0–1 | 0–3 | ||

| Sea Urchins | 0–1 | 0–2 | 0–3 | |||

| Sea Otters | 0–2 | 1–2 | 0–1 | 1–5 | ||

| Puffins | 0–2 | 0–2 | 0–1 | 0–5 | ||

| What is trophic level, predators? | 0–2 | 0–1 | 0–2 | 0–5 | ||

| The Future | ||||||

| How do we do biomonitoring? | 0–3 | 0–1 | 0–2 | 0–4 | 0–10 | |

| Will you do the monitoring for us? | 0–2 | 0–1 | 0–3 | 0–1 | 0–3 | 0–10 |

| Geophysical | ||||||

| What about earthquakes or volcanoes? | 2–2 | 1–0 | 2–3 | 0–1 | 3–3 | 8–9 |

| What can be done if it is leaking? | 1–3 | 2–2 | 1–2 | 2–2 | 3–3 | 10–12 |

| What if radiation comes out far/near in the ocean? | 0–2 | 1–0 | 0–1 | 0–1 | 1–4 | |

Note: Shown are the number of times people asked each type of question before–after the science assessment.

Fig. 2.

Percent of questions asked by Aleuts at public meetings in Atka, Nikolski, and Unalaska in the Aleutian Chain of Alaska. Data are shown by category in 2003 (=100%) and in 2005 (=100%). The number above the bars equals the number of questions asked.

Questions about whether CRESP was going to (or did) analyze for specific species shed some light on their concerns. The most questions were asked about Sea Lion muscle and liver, kelp, and Pogies (Rock Greenling) and their eggs, followed by Halibut, Octopus, and chitons (Black Katys). All of these species were analyzed, and had negligible levels of radionuclides.(39–43)

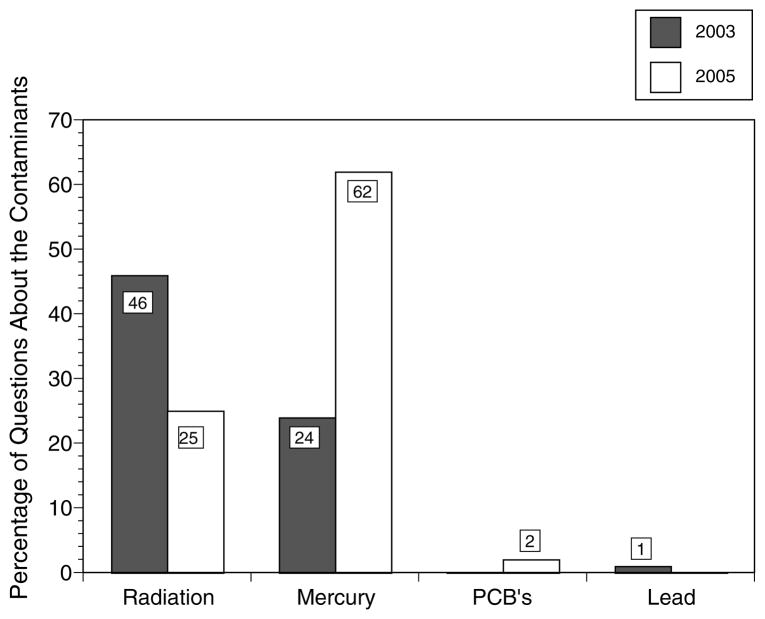

4.2. Health Effects, Risk, and Contaminant Concerns

Overall, people asked more questions about mercury than about radiation, even though the AISA was only for radionuclides (Fig. 3; contingency X2 = 3.62, df = 1, p < 0.057). They asked almost no questions about PCBs and lead, although PCBs were of interest to audiences in Anchorage. Secondly, while the number of questions about radiation and mercury both increased from 2003 to 2005, the relative percentage of questions asked decreased for radiation and increased for mercury (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Percent of all questions asked by Aleuts at public meetings in Atka, Nikolski, and Unalaska about specific contaminants by contaminant type. Includes all questions that were about the contaminant. Each year equals 100%; the number above the bar equals the number of questions asked.

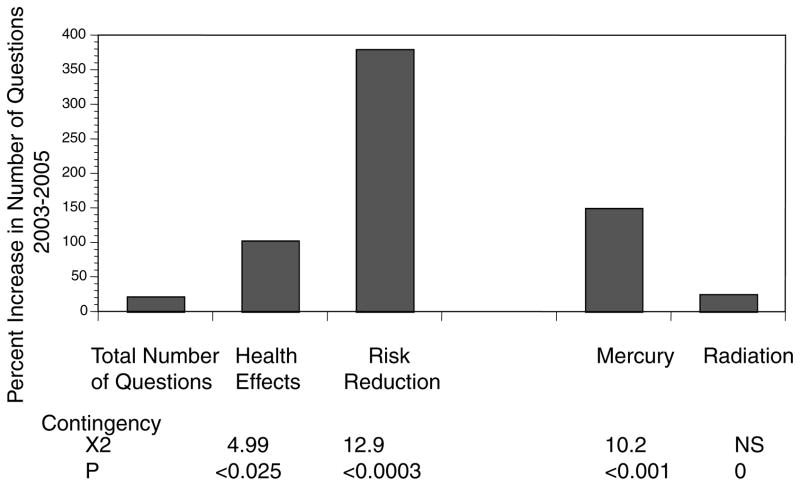

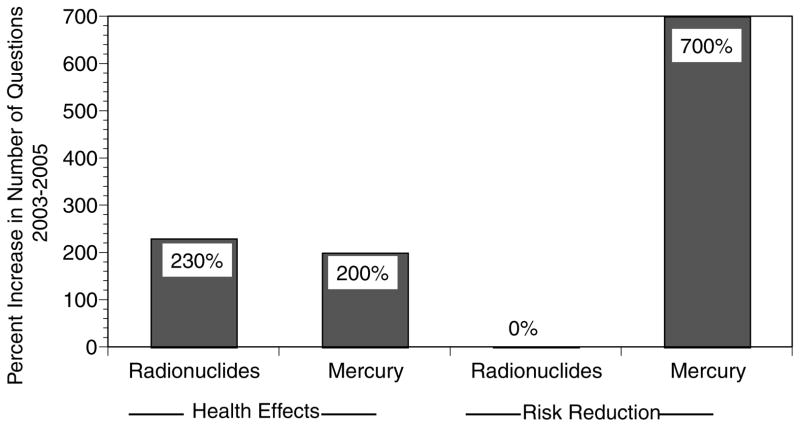

Another way to examine this question is to use the percentage increase in the number of questions from 2003 to 2005 to predict the increase in the number of questions in each category. If there were no relative changes, the percent increase in number of questions asked should be similar for the entire data set (all questions asked) and for the individual issues. This is shown graphically in Fig. 3 and tested by goodness of fit X2. The increase in questions about radiation (Fig. 4) matched the overall increase in questions; however, the percentage of questions asked about health effects, health risk, and mercury all increased significantly. The questions about mercury reflect all questions about mercury regardless of their category, including health effects, risks, and methodological questions (why can’t or didn’t you analyze for mercury?).

Fig. 4.

Percent increase in the number of questions asked about health effects, risk reduction, mercury, and radiation from 2003 to 2005, compared to the overall increase in the number of questions from 2003 to 2005.

There was no difference between mercury and radionuclides in the relative increase in questions about health effects (contingency X2 tests), although there was for risk reduction. The greatest increase in the number of question asked about health risk (and reduction of risk) was for mercury (Fisher exact test p < 0.06), largely because few questions were asked in 2003 (Figs. 2 and 5). In 2003 only three questions were asked about the risk, or reducing the risk, from mercury, while 24 questions were asked in 2005. There was no increase in the number of questions about reducing risk from radionuclides (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Percent increase in the number of questions asked about mercury and radionuclides in the categories health effects and risk reduction only.

4.3. Age Effects

Children and teenagers tended to ask more basic questions, as well as more forthright ones. For example, only youth asked for definitions of contamination, mercury, and radiation (Table II). Youth asked whether a contaminant was bad, while adults asked at what level it was bad. Similarly, only children asked why the nuclear tests were conducted at Amchitka, whether the government was out to get them, where personnel lived during the expedition, and what was eaten on the expedition (Table II). For other types of questions, such as health effects and risk, there were no significant age-related differences in the changes from 2003 to 2005 (contingency X2 tests).

4.4. Credibility and Trust

We had expected that there would be credibility issues, both with CRESP and with DOE. The kinds of questions asked in 2003 about CRESP largely dealt with who asked CRESP to write the plan, who wrote it, who CRESP scientists worked for, who paid for the plan and the study, and whether CRESP scientists were independent, and there were few trust questions in 2005 (Table I). The questions about DOE in both 2003 and 2005 involved asking whether they could trust, believe, or rely on DOE now or in the future. Although the number of questions about trust/credibility in DOE decreased slightly from 2003 to 2005, the difference was small and not significant.

5. DISCUSSION

Unalaska/Dutch Harbor is a complex community with a large fishing and commerce base, served by daily flights from Anchorage. Atka and Nikolski are more isolated and traditional communities, served by biweekly flights from Unalaska/Dutch Harbor. Despite the isolation, the villages have modern communication, Internet access, effective telephone communication, and satellite television. Thus, despite a reliance on subsistence foods, villagers were well-informed about many topics. The schools similarly were well-equipped with libraries and Internet access. Several of the elders remembered the years of nuclear testing, and a few were old enough to have experienced the refugee years when Alaskan natives were forcibly removed from the Aleutians.(44,45) The latter history, now widely popularized, contributes to a measure of distrust of the federal government.

5.1. Methodological Issues

It is exceedingly difficult to evaluate changes in perceptions following the inclusion of science into the management of a charged, controversial environmental issue.(1,10) The approach for this study was to tally all questions asked by the residents (both youth and adults) at public meetings. There are several issues with the methods used in this article: (1) comments were solicited in a public meeting, rather than in one-on-one interviews; some people are inhibited in groups, and (2) once a questions was asked, people might not ask it again, although it might be the most important question in their minds. Firstly, the public meetings were held in relatively small communities of less than 150 resident Aleut individuals, where everyone knew one another. Thus CRESP made the assumption that most people would not be afraid to ask any questions. Further, the authors spent a few days in each community before each meeting, talking to elders, youths, and other community members. Secondly, it might be argued that once a question was asked, the same question would not be asked again. However, this was not the case; when something was important, it was asked again in a different form or refined. For example, in Nikolski in 2003 (as in other communities), people asked about mercury five times.

Another methodological issue deals with what might have changed during the study that was not related to the AISA study, in terms of available information. For example, the media emphasis on mercury in fish over the last several years could have influenced their perceptions. DOE meetings or reports could have provided more information, although there were no DOE meetings during this time and no DOE reports about Amchitka were delivered to the corporation offices of these villages from August 2003 to October 2005. Community composition changed only slightly, with few deaths or departures and few new arrivals. Demographic changes were not tallied, nor was there a sign-in sheet.

Additionally, one might argue that more traditional methods (i.e., written or oral questionnaires) would have provided more detailed or different information on attitudes and perceptions. While surveys are appropriate for a number of populations,(46,47) it was deemed inappropriate for the present project for the following reasons. CRESP wanted to invite and achieve collaboration with a range of stakeholders to improve the success of the AISA before the expedition and improve the acceptance of results afterward. Approaching an isolated subsistence community and requiring them to fill out a questionnaire (or respond to a formal interview) would have been counterproductive to the overall goal of stakeholder involvement. Asking people to answer questions leads responses to some extent and, at the least, defines the limits of the attitudes and perceptions under discussion.(10) Conversely, encouraging people to ask questions allows greater spontaneity without structuring the types of responses.

The question of bias on the part of the evaluators is an important one.(10,48) The questions asked by Aleuts in 2003 were written down to make sure that any important suggestions about how to conduct the research were incorporated into the project, and the questions at the 2005 meetings were noted to make sure suggestions for improvement of the reports (including additional analysis of data) were captured. In both cases, all questions were recorded as an indication of interest, and neither Aleuts nor communicators had evaluation in mind at the time. In essence, this approach is similar to that of Vining and Tyler,(38) who evaluated public comments to forest management.

We suggest that this article provides a new and viable method of assessing concerns, attitudes and perceptions, or beliefs about specific environmental issues within subsistence communities or other communities that may resist oral or written surveys. It is a form of content analysis of meetings that can be accomplished relatively unobtrusively with permission.

Lastly, it is impossible to truly ascribe differences in attitudes and perceptions to a particular management or research program because people have been exposed to other sources of information or actions in the intervening years. However, it does not seem that such additional information influenced the results of this study because there were no additional reports or public meetings held by DOE or other agencies during this time that related to radiation or other contaminants. DOE had held a public meeting in Unalaska (but not in the other communities) in early 2003 describing its groundwater models for Amchitka. DOE did not return to any of these communities between CRESP’s two visits. Further, the category that declined are those that related directly to the study goals (i.e., assessment of radionuclides by CRESP), those that were not addressed in the follow-up meeting did not change (geophysical issues), and those that increased were health-related interests that would be stimulated by a general focus on health issues, but were unresolved by the study (i.e., mercury, changes in populations of subsistence foods, future biomonitoring). Thus the results are consistent with a change in attitudes affected by the AISA.

5.2. Differences in Attitudes and Perceptions

There were significant differences in the kinds and frequency of questions about different issues raised in 2003 and 2005. Thus, the initial prediction of no change in attitudes and perceptions as measured by questions asked was rejected. People asked more questions about health effects and risks, ecology, and the future in 2005 than in 2003, and fewer questions about CRESP and biological methods on the expedition in 2005 than 2003. The differences were neither small nor subtle. While Aleuts would naturally ask fewer questions about methodology, since the project had already been completed, if hostility remained, they might have continued to ask why we did it a certain way. The authors believe these differences were due to the AISA and the presentation of convincing technical data relating to radionuclide levels in biota at Amchitka.

This view is supported by comparing the questions about the biological aspects with the questions about geophysical issues. The AISA dealt mainly with biological information and did not address issues of either earthquakes or volcanoes; stakeholder questions about biological issues declined markedly between 2003 and 2005, while there were an equal number of question about geophysical issues in 2003 and 2005. That is, their concerns (as shown by their questions) did not decline for geophysical issues (Table II). Volcanoes and earthquakes are hot media topics in the Aleutians because this seismically active “rim of fire” region has a high percentage of the strongest earthquakes on earth. While the CRESP study dealt with some geophysical issues, it did not deal directly with either earthquakes or volcanoes and, in any case, the geophysical data were not presented to the Aleuts in their villages on the 2005 visits.

5.3. Health Effects and Risk Reduction

One of the major objectives of the AISA was to assess food safety, and the final report confirmed that radionuclide levels in the vicinity of Amchitka were low to nondetectable in all biota examined, and that all radionuclide levels were below human health standards.(39–43) While people focused on details of the biological methodology in 2003, and asked very few questions about health issues, in 2005 a substantial number of the questions (38%) dealt with health effects and risk reduction (both for radionuclides and mercury). Rather than focus on how CRESP was going to do (or did) the study, they focused on how contaminant levels could affect them, and how to reduce their risk.

Further, people’s concern and worry about radionuclides decreased from 2003 to 2005, while their concern and worry about mercury increased. This difference may be attributable to their satisfaction that a credible study had been conducted to evaluate the levels of radionuclides, and corresponding health risks, and that they were therefore less concerned. No similar study was conducted with mercury levels in their subsistence foods during this period, however, and their concern level increased. They asked why mercury had not been included. This is consistent with the AISA having a positive effect on their attitudes and perceptions. DOE had specifically precluded us from using its funds to analyze mercury. CRESP reported that the samples had been saved for mercury analysis and this would be conducted in the future if funding were obtained.

5.4. Age Effects

Many differences in the types of questions asked by youth and adults in the Aleut communities were expected. In general, young people were interested in definitions of contaminants, whether they were bad for them, whether particular organisms were analyzed, and how expedition members lived on the ship. These differences are understandable. However, there were no significant differences in the relative changes from 2003 to 2005 in the questions asked about health effects and risk, and about biological methods. The young people in these Aleut communities are aware of health concerns and able to ask good questions about the design and execution of the study.

The authors were impressed with the level of interest in the young people in the Aleut communities visited. In Nikolski, for example, every young person attended the meeting, they sat for longer than did their elders, they asked many more questions, and they were very forthright with their responses when questions were posed. At the end of the general open question session, the presenters asked some specific questions about consumption patterns to make sure that the target species collection list was appropriate. While the adults generally admitted to eating certain foods, the young people readily volunteered information on consumption of a wider range of species. They spoke of shooting and eating more different species of ducks, shorebirds, and invertebrates than did their elders. One 15-year-old young man proudly showed us his notebook listing all the birds he had killed in his young life.

Moreover, in some of the Aleut villages it is the older teenagers who are the subsistence hunters in the village. They go out for Halibut and Pacific Cod, bringing them back to distribute first to the elders, and then to the other people in the village. In a small village such as Nikolski, this confers a substantial status on the young people. Even the young girls gaffed salmon in the spawning streams to provide food for their families and villagers.

More importantly, it is the young people of the Aleut villages who will be the next pregnant mothers and who should be aware of any health hazards or risks from subsistence consumption. Empowering them to come to public meetings, ask questions about health and health risks, and provide information about their consumption patterns is important and relevant.

5.5. Trust and Credibility

We had expected that there would be credibility issues, both with CRESP and with DOE, because of the controversy surrounding the underground nuclear tests on Amchitka in the first place, and the continuing issues surrounding the closure of Amchitka and departure of the DOE.(32,33,35) While people initially asked more questions about CRESP’s credibility than about DOE’s in 2003, there were almost no questions about CRESP’s credibility in 2005 and there were about the same number of questions about DOE’s reliability. DOE has had a long history of credibility challenges.(30) Further, the nature of the questions differed (refer to Table I). In 2003 people wanted to know who asked for the study, who wrote it, who paid CRESP, and whether CRESP would return to tell them the results; all important but relatively neutral questions. In both 2003 and 2005 people asked how they could “believe,” “trust,” or “know” that DOE would do things they said they would or should do. Some even expressed the thought that DOE would not let CRESP tell them if radionuclides were found in biota (Table I). Thus even the level of distrust in 2003 differed significantly, and the CRESP study did not allay their concerns about DOE. The outcome might have been different if DOE had sent a representative to the Aleut villages with CRESP, as it did for public meetings held in Anchorage. Villagers were aware that DOE attended the CRESP public meeting in Anchorage because some Aleuts had attended as well.

The issue of a general lack of trust and credibility in DOE has been identified by others for a range of DOE sites.(30,49) Indeed, DOE’s own recognition of the trust and credibility problem it faced with the general public, as well as managers and regulators, led it to commission several National Academy of Science studies that identified public trust and stakeholder participation as one of the key issues in implementation of its waste management strategies.(30,50) The Aleut villages, as well as several other stakeholders, held strong views that the underground nuclear test shots should not have been detonated at Amchitka,(32,33) and trust and credibility have been eroded continuously since that time, partly due to the DOE’s lack of interest in the views, concerns, or information needs of a range of stakeholders. The AISA came about because stakeholders wanted information on radionuclide levels in biota, among other things, rather than relying on the DOE’s groundwater and human health risk models.(28,29) DOE’s human health risk models were based on no recent, site-specific data on either radionuclide levels in biota, including subsistence foods, or of consumption patterns. This did not sit well with Aleut people, the State of Alaska, or several other stakeholders. It is just such a disregard for the informational needs of the local people that has led to the general distrust of the DOE. The present study suggests that perceptions and attitudes can be changed with stakeholder-driven research that provides the data people feel they need, and that when completed, people have fewer questions about radionuclides.

5.6. Lessons Learned

The inclusion of stakeholders throughout the AISA project resulted in ownership of the study and its outcome by the local Aleuts and other stakeholders. The inclusion of Aleuts on the expedition itself,(43,51) a suggestion made by Aleuts in the 2003 public meetings described in this article, went a long ways toward building trust in the study and its data. It also allowed the Aleuts to express concern about cultural aspects of the sampling.(52) Meeting with Aleuts in their small villages, and allowing them to ask as many questions as possible, contributed to their overall sense of well-being with regard to the potential nuclear threat from seepage at Amchitka. Meeting with the youth in these communities allowed us to assess their concerns, and begin a dialogue about health concerns and risk that will influence the future pregnant women within the community. By meeting with Aleuts, and understanding their questions and information needs, it was possible to shape the AISA to provide data relevant to their questions. This in turn led to an increase in trust and credibility for the study and its scientists.

We suggest that using questions asked by stakeholders at public meetings, within the context of a free and unstructured dialogue, provides a method of assessing attitudes and perceptions, and changes in these perceptions following environmental research. Further, the questions can shape the research (or management) to both improve the research and make it more relevant to both the stakeholders and policymakers.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank the people of Atka, Nikolski, and Unalaska for their help and advice during the AISA; we deeply appreciate their hospitality and friendship. We gratefully acknowledge the CRESP management team that worked tirelessly throughout the 6-year process: C. W. Powers, D. Kosson, and L. Bliss. We thank D. Barnes, D. Dasher, L. Duffy, B. Friendlander, S. Jewett, J. Halverson, A. Morkill, R. Patrick, D. Rogers, G. Siekaniec, D. Volz, and V. Vyas for help and advice throughout the Amchitka Process, as well as C. Jeitner and S. Burke for technical assistance, and the entire crew of the Ocean Explorer. C. Chess and M. Greenberg have had a great influence on our thinking about stakeholder participation in environmental decisions. The project was reviewed by the Rutgers University Institutional Review Boards (ARB 01:017, IRB 96:108). This research was partly supported by the Consortium for Risk Evaluation with Stakeholder Participation (Department of Energy, # DE-FC01-95EW55084, DE-FG 26-00NT 40938, DE-FC01-06EW07053), NIEHS Center grant (P30ES0052022), and the Tiko Fund. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors, and do not reflect the funding agencies.

References

- 1.McCool SF, Guthrie K. Mapping the dimensions of successful public participation in messy natural resources management situations. Society and Natural Resources. 2001;14:309–323. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Research Council (NRC) Risk Assessment in the Federal Government: Managing the Process. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Research Council. Issues in Risk Assessment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Research Council (NRC) Understanding Risk: Informing Decisions in a Democratic Society. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.PCCRARM. Presidential/Congressional Commission on Risk Assessment and Risk Management. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1997. Risk Assessment and Management in Regulatory Decision-Making. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradbury JA. Risk communication in environmental restoration programs. Risk Analysis. 1994;14:357–363. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein TV, Anderson DH, Kelly T. Using stakeholders’ values to apply ecosystem management in an upper midwest landscape. Environmental Management. 1999;24:l399–1413. doi: 10.1007/s002679900242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darnall N, Jolley GJ. Involving the public: When are surveys and stakeholder interviews effective? Reviews of Policy Research. 2004;21:581–593. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chess C, Purcell K. Public participation and the environment: Do we know what works? Environmental Science and Technology. 1999;33:2685–2692. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chess C. Evaluating environmental public participation: Methodological questions. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 2000;43:769–784. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chess C. Organization theory and stages of communication. Risk Analysis. 2001;21:178–188. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.211100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slovic P. Perception of risk. Science. 1987;236:280–285. doi: 10.1126/science.3563507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slovic P. Perceived risk, trust, and democracy. Risk Analysis. 1993;13:675–682. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slovic P, Layman M, Flynn J. Lessons from Yucca Mountain. Environment. 1991;3:7–11. 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivimaki M, Kalimo R. Risk perception among nuclear power plant personnel: A survey. Risk Analysis. 1993;4:421–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1993.tb00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flynn J, Slovic P, Mertz C. Decidedly different: Expert and public views of risks from a radioactive waste repository. Risk Analysis. 1994;6:643–648. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell RG, Peterson D, Roush D, Brooks RW, Paulus LR, Martin DB, Lantz BS. Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory Site Environmental Report. Idaho Falls, ID: Environmental Science and Research Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barke RP, Jenkins-Smith HC. Politics and scientific expertise: Scientists, risk perception, and nuclear waste policy. Risk Analysis. 1993;13:425–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1993.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegrist M, Cvetkovich G. Perception of hazards: The role of social trust and knowledge. Risk Analysis. 2000;20:713–719. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.205064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg M, Lowrie K, Burger J, Powers CW, Gochfeld M, Mayer H. Preferences for alternative risk management policies at the United States major nuclear weapons legacy sites. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 2007;50:187–209. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folger R. Distributive and procedural justice: Multifaceted meanings and interrelations. Social Justice Research. 1996;9:395–416. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colquitt JA, Conlon DE, Wesson MJ, Porter COLH, Ng KY. Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2001;86:425–445. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Department of Energy (DOE) How to Design a Public Participation Program. Washington, DC: U.S. DOE, Office of Intergovernmental and Public Accountability (EM-22); 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Energy (DOE) Stewards of National Resources. Washington, DC: Department of Energy (DOE/FM-0002); 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lubbert RF, Chu TJ. Challenges to cleaning up formerly used defense sites in the twenty-first century. Remediation. 2001;11:19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daisey JM. A report on the workshop on improving exposure analysis for DOE sites, September,1996, San Francisco, CA. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology. 1998;8:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crowley KD, Ahearne JF. Managing the environmental legacy of U.S. nuclear-weapons production. American Scientist. 2002;90:514–523. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Department of Energy (DOE) Modeling Groundwater Flow and Transport of Radionuclides at Amchitka Island’s Underground Nuclear Tests: Milrow, Long Shot, and Cannikin. Las Vegas, NV: Nevada Operations Office; 2002. DOE/NV-11508-51. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Department of Energy (DOE) Screening Risk Assessment for Possible Radionuclides in the Amchitka Marine Environment. Las Vegas, NV: Nevada Operations Office; 2002. DOE/NV-857. [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Research Council (NRC) Building Consensus through Risk Assessment and Management of the Department of Energy’s Environmental Remediation Program. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Research Council (NRC) Long-Term Institutional Management of US Department of Energy Legacy Waste Sites. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenpeace. Nuclear Flashback: The Return to Amchitka. Greenpeace; USA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohlhoff DW. Amchitka and the Bomb: Nuclear Testing in Alaska. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merritt ML, Fuller RG, editors. The environment of Amchitka Island. Alaska, U.S. Washington, DC: Technical Information Center, Energy Research and Development Administration; 1997. Report NVO-79. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burger J, Gochfeld M, Kosson D, Powers CW, Friedlander B, Eichelberger J, Barnes D, Duffy LK, Jewett SC, Volz CD. Science, policy, and stakeholders: Developing a consensus science plan for Amchitka Island, Aleutians, Alaska. Environmental Management. 2005;35:557–568. doi: 10.1007/s00267-004-0126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Dutch Harbor—Unalaska, in Alaska, Top U.S Port for landings in 2003. [Accessed on 26 May, 2006];NOAA Report 04-096. 2004 2004 Available at: http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/docs/04-096topports.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Consortium for Risk Evaluation with Stakeholder Participation (CRESP) Amchitka Independent Assessment Science Plan. Piscataway, NJ: CRESP, CRESP; [Accessed on January 5, 2009]. Available at: http:/www.cresp.org. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vining J, Tyler E. Values, emotions and desired outcomes reflected in public responses to forest management plans. Human Ecology Reviews. 1999;6:21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powers CW, Burger J, Kosson DS, Gochfeld M, Barnes D, editors. Biological and Geophysical Aspects of Potential Radionuclide Exposure in the Amchitka Marine Environment. Piscataway, NJ: CRESP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burger J, Gochfeld M, Kosson DS, Powers CW. Biomonitoring for Ecosystem and Human Health Protection at Amchitka Island. Piscataway, NJ: CRESP; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burger J, Gochfeld M, Jewett SC. Radionuclide levels in benthic invertebrates from Amchitka and Kiska Islands in the Aleutian Chain, Alaska. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 2007;128:329–341. doi: 10.1007/s10661-006-9316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burger J, Gochfeld M, Kosson DS, Powers CW, Jewett S, Friedlander B, Chenelot H, Volz CD, Jeitner C. Radionuclides in marine macroalgae from Amchitka and Kiska Islands in the Aleutians: Establishing a baseline for future biomonitoring. Journal of Environmental Radioactivity. 2006;91:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burger J, Gochfeld M, Kosson DS, Powers CW, Friedlander B, Stabin M, Favret D, Jewett S, Snigaroff D, Snigaroff R, Stamm T, Weston J, Volz D, Jeitner C. Radionuclides in marine fishes and birds from Amchitka and Kiska Islands in the Aleutians: Establishing a baseline. Health Physics. 2007;92:265–279. doi: 10.1097/01.HP.0000248123.27888.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kohlhoff DW. When the Wind Was a River. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlung T. Umnak: The People Remember. Walnut Creek, CA: Hardscratch Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lowrie K, Greenberg M. Local impacts of US nuclear weapons facilities: A survey of planners. Environmentalist. 2000;20:157–168. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asher H. Polling and the Public: What Every Citizen Should Know. Washington, DC: CQ Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sciven M. Truth and objectivity in evaluation. In: Chelimsky E, Shadish, editors. Evaluation for the 21st Century. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams B, Brown S, Greenberg M, Kahn M. Risk perception in context: The Savannah River stakeholder study. Risk Analysis. 1999;22:1019–1035. doi: 10.1023/a:1007095808381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Research Council (NRC) Improving the Environment: An Evaluation of DOEs Environmental Management Program. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burger J, Gochfeld M, Powers CW, Kosson DS, Halverson J, Siekaniec G, Morkill A, Patrick R, Duffy LK, Barnes D. Scientific research, stakeholders, and policy: Continuing dialogue during research on radionuclides on Amchitka Island, Alaska. Journal of Environmental Management. 2007;85:232–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burger J, Gochfeld M, Pletnikoff K, Snigaroff R, Snigaroff D, Stamm T. Ecocultural Attributes: Evaluating, Ecological Degradation in Terms of Ecological Goods and Services Versus Subsistence and Tribal Values. Risk Analysis. 2008;28:1261–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]