Abstract

Fluorescent D-amino acids (FDAAs) are efficiently incorporated into the peptidoglycan of diverse bacterial species at the sites of active peptidoglycan biosynthesis, allowing specific and covalent probing of bacterial growth with minimal perturbation. Here, we provide a protocol for the synthesis of four FDAAs emitting light in blue, green or red and for their use in peptidoglycan labeling of live bacteria. Our modular synthesis protocol gives easy access to a library of different FDAAs made with commercially available fluorophores. FDAAs can be synthesized in a typical chemistry laboratory in 2–3 days. The simple labeling procedure involves addition of the FDAAs to the bacterial sample for the desired labeling duration and stopping further label incorporation by fixation or by washing away excess dye. We discuss several scenarios for the use of these labels including short or long labeling durations, and the combination of different labels in pure culture or complex environmental samples. Depending on the experiment, FDAA labeling can take as little as 30 s for a rapidly growing species such as Escherichia coli.

INTRODUCTION

The peptidoglycan (PG) cell wall of bacterial cells is a macromolecular polymer consisting of β-1,4-linked glycan strands that are cross-linked by short D-amino acid-containing peptide chains. PG is an essential structure for bacterial cells that precisely determines cell size and shape and enables them to resist lysis. The PG biosynthetic pathway is an attractive target for antibiotic intervention because the key polymerization and cross-linking reactions take place on the solvent accessible surface of the bacterial cell. Also, since animal cells did not inherit a peptidoglycan shell, the potential for toxicity to humans is minimized1. Unfortunately, the resistance of pathogenic bacteria to even the newest PG acting antibiotics has increased alarmingly, underscoring the urgent need for novel additions to our current antibiotic pharmacopeia. The development of novel PG acting agents has lagged; however, because our overall knowledge of PG biosynthesis and turnover is still very limited2,3. This is due, in part, to the lack of tools or methods to enable real-time spatiotemporal tracking of PG biosynthesis in live bacterial cells4,5. Recently, we have shown that fluorescently modified D-amino acids enable rapid and covalent detection of cell wall biosynthesis, in real time, in live cells, and in a broad range of bacterial species6. This method has already been used to study growth or PG synthesis mechanisms in various bacterial species7–10. Here we detail the fluorescent D-amino acid (FDAA) technology by describing the modular syntheses of four differently colored FDAAs (Figure 1), namely HCC-amino-D-alanine (HADA; 3, λem ~ 450 nm), NBD-amino-D-alanine (NADA; 5, λem ~ 550 nm), fluorescein-D-lysine (FDL; 8, λem ~ 525 nm) and TAMRA-D-lysine (TDL; 10, λem ~ 575 nm), in a basic organic chemistry laboratory and by discussing different applications of FDAAs. We also note that the synthesis protocol for the red FDAA, (TDL), represents a common protocol for generating custom DAAs by attaching a common D-amino acid backbone (amino-D-alanine or D-lysine) to a myriad of commercially available succinimidyl ester activated dyes or other functionally activated molecules.

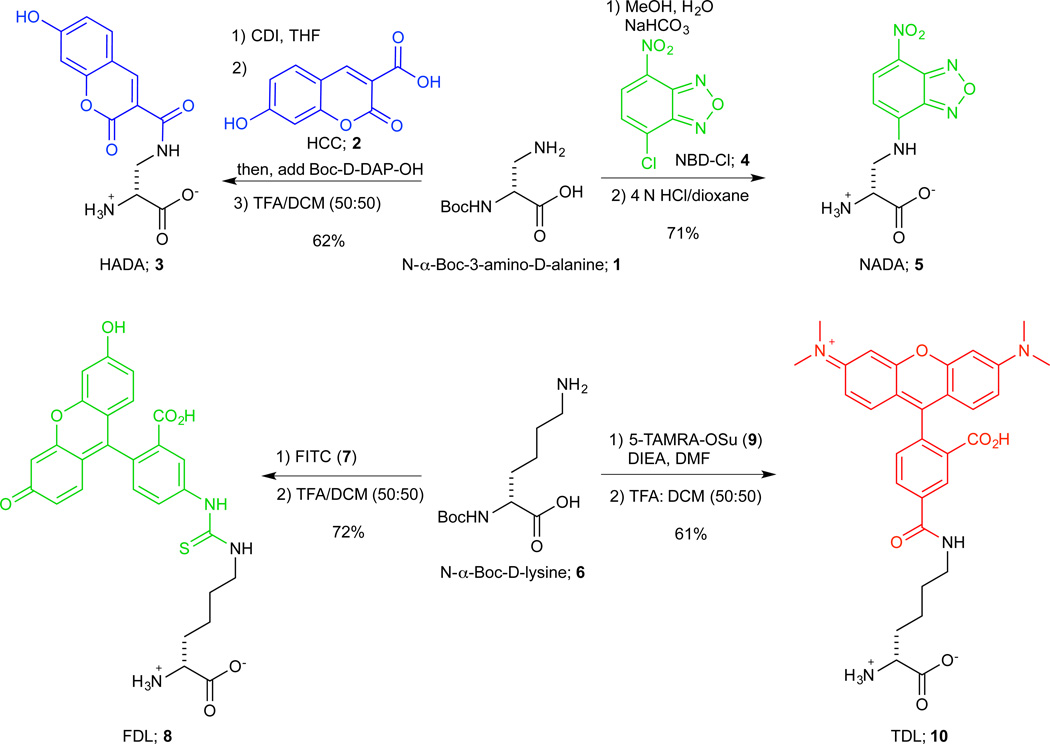

Figure 1. Modular syntheses of FDAAs.

HADA 3 and NADA 5 attaching commercially available fluorophores, 7-hydroxycoumarin-3-carboxylic acid (HCC-OH; 2) and 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan (NBD-Cl; 4) to the backbone N-Boc-D-2,3-diaminopropionic acid (i.e. N-α-Boc-3-Amino-D-Alanine; 1); and FDL 8 and TDL 10 attaching commercially available fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; 7) and 5-(and 6-) carboxytetramethylrhodamine succinimidyl ester (TAMRA-OSu; 9) to the backbone N-α-Boc-D-Lysine 6, respectively. In our experience, HADA is the FDAA probe of choice when the factors regarding ease of incorporation into the PG of diverse bacterial species, brightness, photo-stability and price of synthesis are considered. For example, despite its inexpensive synthesis, NADA suffers from low photo-stability. On the other hand, while FDL, and especially TDL, are brighter and more photo-stable than HADA, the metabolic incorporation of these larger FDAAs into cell walls is particularly limited in Gram-negative bacteria.

Limitations of existing methods

The development of tools and methods to enable real-time tracking of the progression of cell wall biosynthesis and peptidoglycan recycling is a problem of significant current interest for which there was no general solution4,5. Methods relying on fluorescently-labeled antibiotics such as vancomycin, with high affinity for nascent PG, have had a profound impact on the field, but these methods also have some inherent limitations11,12. First, antibiotic concentration and treatment duration needs to be carefully controlled in order to get acceptable labeling while avoiding extensive damage to the cell and; second, because of the substantial size of these agents, labeling is limited to the sites of active PG synthesis in bacteria with solvent-exposed cell walls (i.e., Gram-positive bacteria), or to mutants of Gram-negative bacteria with a compromised outer membrane. Other approaches have sought to covalently modify the bacterial cell wall through incorporation of synthetically modified cell wall precursors that are metabolically incorporated by the peptidoglycan biosynthetic machinery. In general, these methods have provided unsatisfactory results either due to poor substrate uptake and incorporation, and/or toxicity due to the site selected for probe incorporation13–17. A recent report has described the use of a fluorescently-modified tripeptide component of the PG stem peptide for covalent labeling of the bacterial cell wall in live Escherichia coli14. However, since the method relies upon a specific PG recycling pathway utilized by this organism, its application is limited to E. coli and it also suffers from poor substrate analog utilization. More recently, we have shown that D-alanyl-D-alanine dipeptide analogues with small bio-orthogonal handles can efficiently and stably label PG of a diverse set of bacteria through a similar cytoplasmic incorporation route. Unfortunately, the detection of the incorporated material requires fixed and permeabilized samples and therefore this method cannot be used to trace the growth of live bacteria18.

Other efforts have utilized covalent incorporation of D-cysteine into PG, either through chemoenzymatic incorporation into the Park nucleotide19, or through direct incorporation of D-cysteine into the stem peptide via a periplasmic exchange mechanism12,13,17–20. In this approach, once incorporated into the PG, the nucleophilic thiol group of D-cysteine can be used to capture an electrophilic reporter group (e.g.; pyrene, or biotin) and enable direct or indirect (via antibody capture) fluorescence detection. Although this method has been successfully used to label the bacterial cell wall and monitor PG synthesis in diverse Gram-negative bacteria13,21, it requires the laborious purification of PG sacculi away from cellular proteins, which contain reactive thiol groups. This requirement not only limits the signal detection to hollow sacculi but also precludes the application of this method for real-time detection of PG synthesis. Despite its limitations, D-cysteine labeling of PG suggested that a similar approach using fluorescent D-amino acids might be generally applicable to bacteria, since evolutionary distinct species are known to produce and incorporate various D-amino acids into their PG22,23.

Development of fluorescently-modified D-amino acids (FDAAs)

Our design strategy was built upon the tolerance of diverse bacterial species to incorporation of various D-amino acids (DAAs), including the relatively small D-cysteine and the largest natural DAA, D-tryptophan, into their peptidoglycan22–24. These observations suggested that the mechanisms for DAA incorporation should be tolerant to modifications on the side chain of a D-amino acid. Furthermore, DAAs may be incorporated into PG by at least three different mechanisms, depending on the species: through the cytoplasmic steps of PG biosynthesis and via two distinct transpeptidation reactions taking place in the periplasm24–27. Notably, two of these possible routes: namely, the cytoplasmic route for PG biosynthesis and the periplasmic route catalyzed by the essential penicillin binding proteins are directly linked to PG biosynthesis and are shared by virtually all PG-synthesizing bacterial species28–31. Thus, we hypothesized that growing cells of a wide range of bacterial taxa exposed to fluorescent reporter groups attached to a DAA backbone would result in the incorporation of these florescent D-amino acids at sites of new PG synthesis. Indeed, a wide array of fluorophores sharing a common D-amino acid carrier molecule proved to be readily and specifically incorporated into PG at the sites of active growth in diverse bacterial species, regardless of the size of the fluorescent side chain (Figure 1)6. While this approach addressed the inherent limitations of the methods described above, the availability of dyes of different colors also opened the way for novel applications such as “virtual time-lapse microscopy” in which the dynamics of cell growth is revealed by pulse-labeling cells with different colored dyes over time (Figure 2)6.

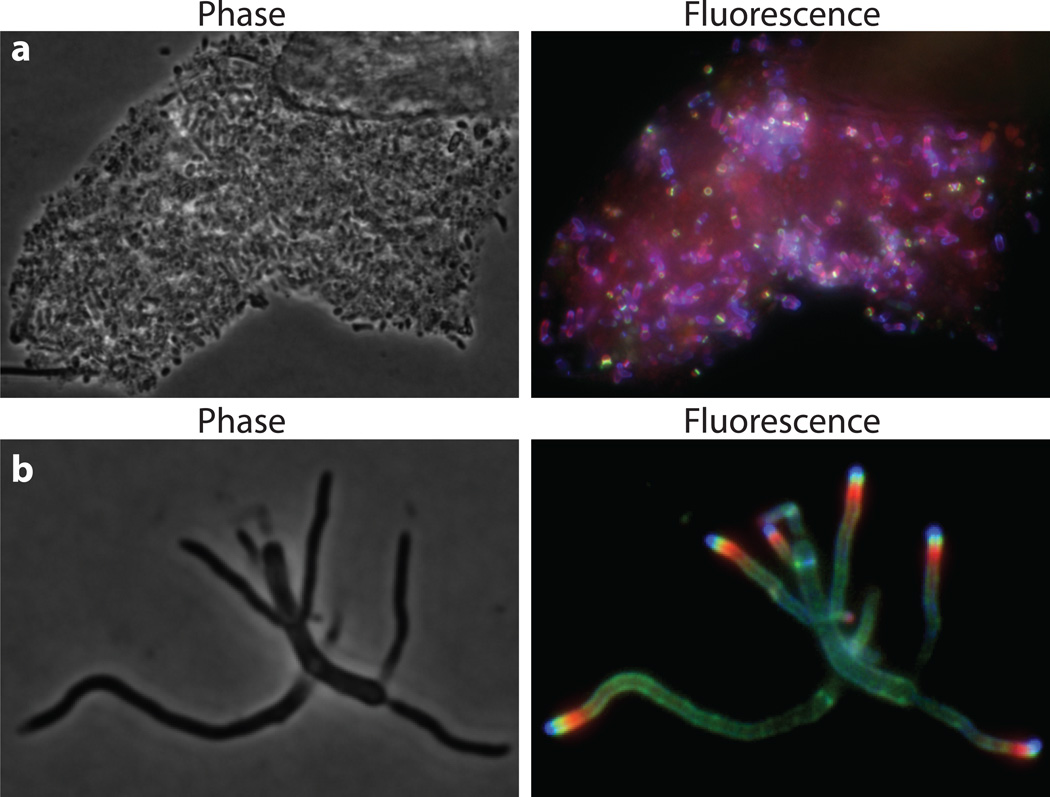

Figure 2. Virtual time-lapse microscopy with FDAAs.

(a) A saliva sample was pulse-labeled successively with TDL (red), FDL (green) and HADA (blue) for 15 min each. The labeling patterns on each cell provide chronological account of the areas of PG synthesis during each pulse labeling, with the red and green signals representing the oldest and the newest parts of the cell wall relative to the duration of the experiment, namely 3 × 15 min. (b) Virtual time-lapse microscopy on Streptomyces venezuelae pulse labeled with TDL (red), FDL (green) and HADA (blue) for 5 min each.

An alternative to FDAAs is the use of non-fluorescent but commercially available, small and “clickable” D-amino acids, which, similarly to the FDAAs, efficiently labeled PG of diverse bacteria6,26. Once incorporated, the reactive functional groups embedded in the DAA core structure can be selectively captured in a second step, through click chemistry, including by any fluorescent dye containing the complementary functional group32,33. Although this two-step bio-orthogonal approach potentially introduces complications—such as dependence of the signal strength on the efficiency of the click chemistry reactions or non-specific interaction of the probes with other cellular structures—this approach also significantly expands the utility of the DAA-mediated PG labeling method as numerous clickable fluorophores with varied excitation and emission properties are available from commercial sources.

Labeling strategies and applications

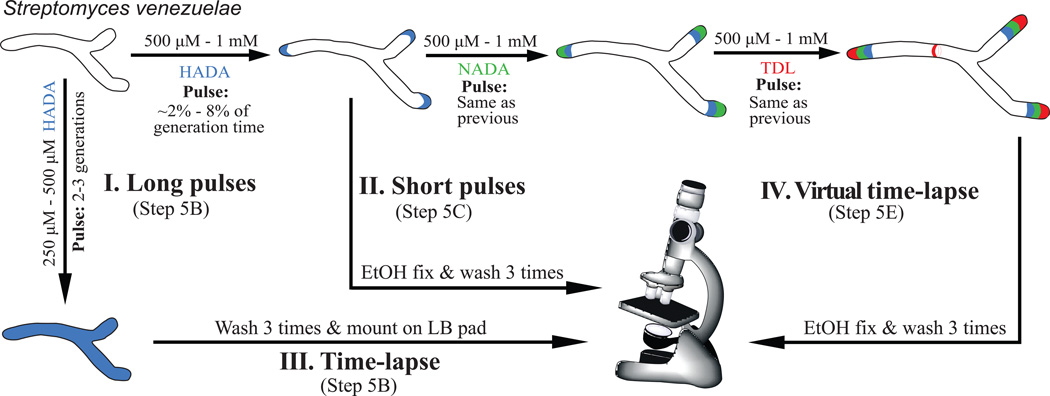

FDAAs have been used to label sites of PG synthesis in a broad range of taxonomically diverse bacteria (Table 1). In addition, they have been used to address otherwise-difficult–to-answer fundamental questions about bacterial growth and division6,7,9,10,34–39.For example, FDAAs enable visualization of distinct modes of growth by resolving sites of active growth from older cell wall6. Distinguishing between old and new PG can be done in two distinct ways; exposing cells to FDAAs either for long durations (1–2 generations, i.e. long labeling pulses, Figure 3, I) or for shorter durations (%2–5% of one generation time, i.e. short labeling pulses, Figure 3, II). The long pulses commonly result in cells that are uniformly labeled (Compare Figure 4 a–b). When the excess dye is washed and the cells are allowed to grow in the absence of additional dye (i.e. a chase), the new wall synthesis commonly manifests itself as the spatiotemporal dilution of the signal. Notably, the non-toxicity of FDAAs allows this experiment to be conducted under the microscope in real time, generating single-cell time-lapse movies of cell wall growth (Figure 3, III)6. On the other hand, the link of DAA incorporation to the PG biosynthetic enzymes enables FDAAs to resolve PG synthesis directly when they are added to actively growing cells for a brief labeling period. Indeed, we have observed a strong correlation between sites of FDAA labeling and previously inferred PG growth mechanisms of diverse bacterial species6,40, indicating that FDAAs can be used to mark the regions of active growth. Additionally, because of their DAA backbone, FDAAs can facilitate any study on the effects and mechanisms of DAA utilization, an area of active research with potential therapeutic applications22,23,25,26,34. They can also be used as substrate analogs to monitor the biochemical activity of essential PG synthetic enzymes (e.g. PBPs) in different species24,27,41, which previously depended on the use of radioactive substrates (including radioactive DAAs) and/or suicide probes such as fluorescent β-lactams.

TABLE 1.

Basic properties of the FDAAs detailed in this protocol

| MW | FW of HCl salt |

FW of TFA salt |

Ex (nm)1 |

Em (nm)1 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NADA | 267 | 303.6 | 381.2 | ~ 450 | ~ 555 |

| HADA | 292 | 358.7 | 406.3 | ~ 405 | ~ 460 |

| FDL | 536 | 572 | 649.6 | ~ 490 | ~ 540 |

| TDL | 560 | 596 | 673.7 | ~ 555 | ~ 595 |

Values are for the respective fluorophores used for the synthesis of FDAAs6.

Figure 3. Flow chart for different FDAA labeling strategies detailed in this protocol.

The polarly growing Gram-positive bacterium Streptomyces venezuelae is used as an example.

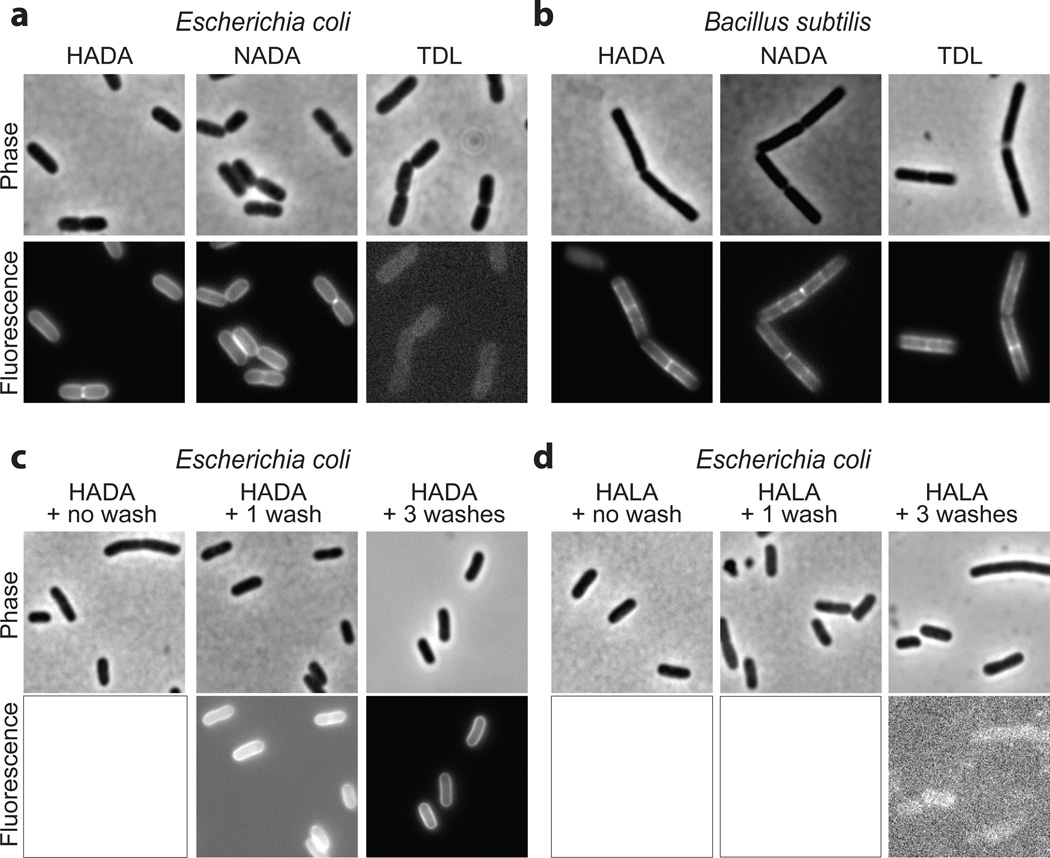

Figure 4. The quality of the FDAA labeling depends on the choice of the dye and other experimental factors.

(a–b) While cells grown with HADA, NADA, or TDL (500 µM, several generations for E. coli and 20 min for B. subtilis) show similar patterns, the labeling quality, i.e. the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), can differ significantly. Under these experimental and imaging conditions, SNRs of HADA, NADA and TDL are 6.3, 1.9, and 1.07 (i.e. the signal is 7% above background) for E. coli and 2.69, 1.55, and 2.91 for B. subtilis. In E. coli, the low SNR of TDL is due to its poor outer-membrane permeability. The lack of labeling on the poles of B. subtilis is typical in briefly pulsed rod-shape bacteria and represents the inertness of the polar cell walls. (c–d) SNR depends on other experimental factors such as effective washes. Without washes, the signal from HADA labeled E. coli cells (500 µM, several generations) is obscured by the background fluorescence and therefore SNR is 1 (c, left). Each wash improves the SNR (SNRHADA, Wash x1=1.5; SNRHADA, Washx3=3.03). After the washes, the L-isomer, HALA, treated cells (SNRHALA, Wash x3=1.02) show ~100 times less normalized signal relative to the HADA labeled cells. Display ranges within c, or d were kept constant for visual comparison.

Due to its modular design, the FDAA toolkit could easily be expanded in order to provide probes with enhanced fluorescence properties and/or emission maxima in longer wavelength regions of the visible spectrum (Table 2). Indeed, the synthesis protocol for the red FDAA, TDL, contains general guidelines for researchers to synthesize their own custom fluorescent, or other D-amino acid derivatives, with different user-defined features from an appropriately functionalized D-amino acid (e.g. amino-D-alanine or D-lysine) and any suitably activated fluorescent dye.

TABLE 2.

Different applications and conditions of FDAA labeling in different bacteria reported to date.

| Application | Bacteria | FDAAs | [FDAA] mM |

Labeling duration |

Temp (°C) |

Growth media, |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Introduces the concept that custom hapten containing D-amino acids may be used to elicit an immune response. | Bacillus subtilis | NDL | 0.25 | 4 h | 37°C | LB | 34 |

| Detection of PG localization in a mutant that loses its periplasmic integrity | Escherichia coli | HADA | 0.5 | 2.5 h | 37°C | MOPS | 35 |

| Role of various members of PG assembly complex on cell morphology | Streptococcus pneumoniae | BADA | 0.5 | 4 min | 37°C | THY | 44 |

| Validation of a new cell-growth marker | Escherichia coli | HADA | 1 | 1 h | 37°C | LB | 36 |

| Labeling active sites of PG synthesis in three gram-negative α-proteobacteria |

Caulobacter crescentus Asticcacaulis excentricus Asticcacaulis biprosthecum |

HADA | 0.25 | 5 min | 30°C 26°C 26°C |

PYE | 37 |

| Revealing the presence of a functional sacculus in environmental Chlamydiae | Acanthamoeba castellanii infected with Protochlamydia amoebophila or Simkania negevensis | HADA BADA |

1.5 | 6 h | 20°C | TSY | 7 |

| Characterization of divin, a new and specific inhibitor of bacterial cell division | Caulobacter crescentus | HADA | 0.5 | 10 min | 30°C | PYE | 38 |

| Testing the role of concerted cell elongation and division factors for proper cell division | Escherichia coli | HADA | 1.1 | 30 s | 30°C | M9 | 39 |

| Quantifying the presence of PG in wall-less spheroplasts | Escherichia coli | HADA | 0.5 | 1 h | 37°C | LB | 9 |

| Probing the active PG synthesis during spore formation. | Bacillus subtilis | FDL | 0.5 | 5 min | 37°C | SM | 10 |

| Introduction of FDAAs as a tool to label sites of PG synthesis in diverse bacteria. Conditions for short pulses with HADA is shown. As a starting point, half the shown FDAA concentration can be used for pulses longer than 1 generation. |

Bacillus subtilis Brachybacterium conglomeratum Lactococcus lactis Staphylococcus aureus Streptococcus pneumoniae Streptomyces venezuelae Agrobacterium tumefaciens Burkholderia phytofirmans Caulobacter crescentus Escherichia coli Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 Verrucomicrobium spinosum |

HADA (NADA, FDL, TDL) |

1 1 1 1 0.5 0.5 1 0.5 0.5 1 1 0.25 |

30 s 8 min 2 min 2 min 4 min 2 min 2 min 20 min 5 min 30 s 1 h 10 min |

37°C 30°C 37°C 37°C 37°C 30°C 26°C 30°C 30°C 37°C 26°C 30°C |

LB LB LB LB BHI LB LB LB PYE LB BG11 VM |

6 |

MOPS: Morpholinepropanesulfonic acid minimal medium.

THY: Todd-Hewitt Yeast broth

LB: Lysogeny Broth

PYE: Peptone Yeast Extract

TSY: Tryptic Soy medium

M9: M9 Salts minimal media

SM: Sporularion medium

BHI: Brain-Heart Infusion Broth

BG11: BlueGreen Medium

VM: Verrucomicrobia Medium

BADA BADA (first introduced in7) is a brightly green fluorescing gram-negative accessible FDAA that can be synthesized by coupling Bodipy-Fl-NHS ester to Amino-D-alanine following the principles of Step 1D.

Combined with the universality and the specificity of these probes for live bacterial cells, this modularity facilitates other applications. For example, FDAAs can be used to measure bacterial viability/activity, and to assess the diversity of growth modes of natural bacterial populations in complex microbiomes. Indeed, we have demonstrated that FDAAs can be used to reveal growth modes of bacteria in saliva and freshwater samples in situ (Figure 2 a)6. Therefore, FDAAs provide a valuable alternative to cell viability procedures that measure membrane integrity, such as Life Technologies’ LIVE/DEAD Cell Viability Assays, for probing bacterial activity. Additionally, current FDAAs and/or near-IR derivatives may be used to diagnose bacterial activity on surfaces or in infections, and therefore may find a wide use in fields ranging from environmental microbiology and medical bacteriology to biomaterial engineering.

Access to multiple color fluorophores not only simplifies any experimental design involving other fluorescent tags (e.g. fluorescently tagged proteins), but their use in concert also enables virtual time-lapse microscopy (Figure 3, IV). This application records the chronological history of PG synthesis on the cell wall itself in the form of varying colors and enables visualization of the location and extent of growth during the respective labeling periods on individual cells in situ (Figure 2). Of pharmaceutical interest, this approach can also easily be adapted to probe effects of differing conditions (e.g. antibiotics, temperature, nutrient deprivation) on growth during respective periods at a single cell level, facilitating direct characterization of effects of different antibiotics on bacterial growth and PG synthesis, as was recently demonstrated with HADA38. Furthermore, the modularity of this labeling method can allow modification of bacterial surfaces by a variety of other immunologically active molecules. For example, an immune response to a bacterial infection can be elicited by the synthetic DAA molecules coupled to haptens. Indeed, proof-of-principle has recently been demonstrated34. Finally, FDAAs directly provide a blueprint for new DAA-based antibiotics as the accumulating evidence suggests that a DAA core is sufficient to direct a molecule into the active sites of essential and high-value targets, PBPs, in vitro24,27 and in vivo22 in diverse bacteria.

Experimental design and crucial parameters

The synthetic routes for FDAA synthesis (Figure 1) are simple and the labeling protocol is straightforward. HADA (3) and NADA (5), currently the most robust DAA derivatives, can be prepared in good yields, from N-α-Boc-protected 3-amino-D-alanine (1), via nucleophilic capture of an activated ester of 7-hydroxycoumarin-3-carboxylic acid (HCC-OH; 2) or by nucleophilic aromatic substitution of 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole (NBD-Cl; 4), respectively. The D-lysine-based probes, FDL (8) and TDL (10), are readily prepared via acylation of the D-amino group of N-α-Boc-protected D-lysine with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; 7) and 5-carboxytetramethylrhodamine succinimide ester (5-TAMRA-OSu; 9), respectively. Although we did not observe significant labeling with enantiomeric fluorescent L-amino acid controls6, if necessary, these molecules can be synthesized following the same protocols for the FDAAs by using either N-α-Boc-protected 3-amino-L-alanine or N-α-Boc-protected L-lysine as the amino acid backbones. Freeze-dried FDAAs should be stored at −20°C, or below.

The probes are highly soluble in DMSO (up to 1 M). Thus, stock solutions should be made with DMSO and these solutions should be stored in a freezer at −20°C, or below. When in solution, we have observed slow decomposition of NADA. Therefore, lengthy storage times of the FDAA stock solutions, in particular at room temperature, should be avoided.

For a controlled and reproducible labeling experiment, a pure and exponentially growing bacterial culture, preferably started from a single colony or from a −80°C freezer stock, should be used. In addition, the introduction of any contaminants should be avoided by using sterilized growth media and by performing experiments using sterile techniques and procedures. Although we did not observe a clear correlation between the extent of probe incorporation and the richness of the growth medium, we recommend the use of a medium (and other conditions such as temperature and aeration) that supports the optimal growth for the given species. We recommend performing labeling experiments using exponentially growing cultures. Although the duration of a labeling experiment will depend on the growth rate of the bacterium and the type of the experiment (compare the labeling durations in Table 1). The total time required to complete a labeling experiment from an exponentially growing culture is approximately 45 minutes. For example, sample processing involves EtOH fixation (10–12 min), followed by washing (3 washes; 3–5 min each) and mounting of the sample(s) for imaging (approx. 10 min). We have found that as many as four distinct labeling conditions can be sampled simultaneously without significantly extending the sample processing time. Finally, we recommend allowing at least 10 minutes of imaging time per sample especially if quantitative comparisons between different growth conditions are intended.

Although FDAA labeling is applicable to a wide range of taxonomically diverse bacteria6, for initial experiments involving an untested strain (or for testing the quality of the synthesized FDAAs, see below), the user should label a strain that is known to incorporate FDAAs well as a positive control. More specifically, we recommend Bacillus subtilis PY79 ATCC 55567 and E. coli MG1655 ATCC 700926 as Gram-positive and Gram-negative control strains, respectively (Figure 4 a–b). Notably, we have observed a species dependence on the signal-to-noise ratio, with Gram-positive bacteria usually providing better signal-to-noise ratios. This observation could be attributable to the outer membrane permeability barrier present in Gram-negative organisms, the fact that Gram-positive organisms have a thicker PG layer, or species-specific efficiency of FDAA incorporation or turnover.

In a given strain, although the labeling patterns were similar, if not identical (Figure 4 a–b) and the labeling is D-isomer specific (Figure 4 c–d), the labeling efficiency, and the signal-to-noise ratio, showed a strong dependence on the nature of the probe, probe concentration, duration of incubation, and media. Although HADA, is dimmer and less photo-stable than FDL or TDL, it most reproducibly and robustly labeled the PG of most bacterial species, typically without the need for extensive optimization. Therefore, we recommend the use of HADA, especially for end-point applications. For time-course experiments, TDL is recommended over HADA, since TDL is the most photo-stable FDAA and its higher excitation wavelength is expected to cause the least photo-damage to the cells; however, it should also be noted that TDL is usually not accessible to Gram-negative bacteria due to poor outer-membrane permeability (Figure 4 a, and below).

FDAAs are non-toxic to cells at the typical concentrations used for labeling. Indeed, growth curves of E. coli, B. subtilis, and A. tumefaciens indicated that 500 µM of HADA had no impact on cell shape, lag phase, growth rate, and growth yield6. In general, increasing probe concentration resulted in a noticeable increase in signal to noise while remaining neutral to bacterial growth and morphology, at least until probe concentrations reached ~500 µM –1 mM6. Thus, the user should titrate the FDAA concentration until a desired signal to noise ratio is achieved, while also watching for adverse effects on growth rate or morphology. We note that cells tolerated even higher FDAA concentrations for short labeling times, presumably because of the shorter perturbation to the system, but higher concentrations resulted in reduced growth rates and cell shape changes. In addition, the overall signal-to-noise ratio increased as a function of incubation time, indicating that FDAA incorporation is strongly correlated with growth, but it appeared to plateau after 1–2 generations (1–2 % of all muropeptides are labeled at the optimal probe concentration used for long pulses)6. Accordingly, heat-killed cells6 or dormant cells (unreported data) did not incorporate FDAAs.

Limitations

In contrast to fluorescently-modified vancomycin derivatives, which bind non-covalently to newly synthesized PG with high affinity, our data suggest that FDAA probes are covalently incorporated into PG via periplasmic exchange mechanisms involving bacterial transpeptidases. Procedurally, this means that the user needs to expose cells to relatively high concentrations of the probe (250 µM−1 mM). Thus, before imaging, the overwhelming signal from the excess free-dye needs to be removed by washing (Figure 4 c–d). Depending on the time required for washing, cells may continue to grow, thereby diluting the FDAA signal, especially if a growth medium is used for washes. Therefore, the user should either perform washes in buffer (e.g.; cold 1 × PBS) or employ an appropriate fixative (such as ethanol or paraformaldehyde) before washing. Of course, washing with non-toxic buffers is essential for time-course experiments.

The close correlation between known growth modes of different bacterial species with the labeling patterns of cells that are briefly pulsed with FDAAs led to the conclusion that short pulses with FDAAs mark sites of new PG synthesis6. However, PG turnover might diminish signal intensity at sites of PG synthesis, especially with experiments conducted for longer labeling periods. A body of accumulating in vivo and in vitro evidence indicates that non-canonical D-amino acids and FDAAs are incorporated predominantly by periplasmic L,D- and/or D,D-transpeptidases in certain species (e.g.; E. coli, Vibrio cholerae, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae and B. subtilis)6,24,25,27(and unpublished data). D-cycloserine inhibition experiments have suggested that cytoplasmic pathway might play a role in the incorporation of some small non-canonical -D-amino acids (including the synthetic ones with bio-orthogonal handles, e.g. alkynes or azides) in other species such as Caulobacter crescentus and Listeria monocytogenes25,26,42,43. However, since the cytoplasmic route requires tolerance of additional 5–7 enzymatic steps in addition to the uptake of the DAAs through the negatively charged membranes, the highly tolerable periplasmic transpeptidations for the incorporation of abnormally large and charged FDAAs appear to be a more likely route. Nonetheless, the FDAA incorporation mechanism(s) will need to be established for rigorous interpretation of the labeling data in a given species. For example, in a species that incorporates FDAAs solely through periplasmic PBPs, the short pulse data will be more indicative of the spatiotemporal distribution of the active PBPs than of the nascent PG introduction into the wall by transglycosylation of the lipid II PG precursors.

The vast majority (>90%) of the bacterial strains we have studied thus far were labeled with FDAAs on the first attempt. A few strains required optimization for significant labeling (e.g. Myxococcus xanthus) or could not be labeled (e.g. Planctomyces limnophilus). In cases where a strain cannot be labeled, the user needs to consider several possibilities: 1) The strain might turn over FDAA modified muropeptides effectively (e.g.; high D,D-carboxypeptidase and D,D-transpeptidase activity has the potential to cleave the FDAAs of the modified muropeptides); 2) the strain might lack a mechanism for FDAA uptake and/or incorporation; and 3) the strain might lack a conventional D-amino acid rich cell wall. While the first two possibilities could be addressed by the use of alternative metabolic labeling strategies such as fluorescent tripeptides14 or more efficiently D-Ala-D-Ala dipeptide analogues18, the lack of a conventional peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway in a given species might evade any of the currently available PG detection methods.

D-amino acids are known to modify and strengthen the PG layer23,25. While it is clear that FDAAs modify PG, it is still not known whether their incorporation under experimental concentrations affects PG properties. Nevertheless, the user is advised to determine and use the lowest probe concentration that will result in an acceptable signal-to-noise ratio. Finally, it should be noted that the unique molecular structure of each probe presents the possibility for probe-dependent interactions with macromolecules within the cell that may result in differences in their labeling efficiencies or in labeling patterns. For example, in some bacteria, labeling with NADA required a probe concentration that was four times higher than that required of the HADA probe in order to achieve a similar signal-to-noise ratio. In addition, the size of the probe can affect its efficient uptake and incorporation. Indeed, although the patterns of labeling with HADA, NADA and TDL were similar within E. coli or B. subtilis (Figure 4 a–b), TDL does not strongly label E. coli6 (Figure 4 a) unless outer-membrane permeability is compromised (unpublished data).

MATERIALS

REAGENTS

Anhydrous dimethylformamide (EMD chemicals INC., cat. No. DX1726)

Anhydrous sodium sulfate (Macron chemicals, cat. No. SX0760E)

Argon

1 M aqueous hydrochloric acid (Macron chemicals, cat. No. 7-10108) ! CAUTION: Corrosive, irritant,

Carbonyldiimidazole (Sigma Aldrich, cat. No. 115533)

5-(and 6-) carboxytetramethylrhodamine succinimidyl ester (TAMRA-OSu) (Anaspec, cat. No. 81124)

4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan (NBD-Cl) (Sigma Aldrich, cat. No. 25455)

Dichloromethane (Macron chemicals, cat. No. 1-19590)

Diisopropylethylamine (Sigma Aldrich, cat. No. 387649)

Ethyl acetate (Macron chemicals, cat. No. 1-19950)

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (Anaspec, cat. No. 20151)

HPLC grade acetonitrile (Sigma Aldrich, cat. No. 34851)

HPLC grade water (EMD chemicals INC, cat. No. WX0008)

4 M hydrochloric acid solution in dioxane (Sigma Aldrich, cat. No. 345547) ! CAUTION: Corrosive, irritant

7-Hydroxycoumarin-3-carboxylic acid (HCC) (Anaspec, cat. No. 81205)

Methanol (Macron chemicals, cat. No. 1-12108)

(Nα-tert-butoxycarbonyl)-D-2,3-diaminopropionic acid (Boc-D-Dap-OH) (Chem-Impex, cat. No. 06293)

(Nα-tert-butoxycarbonyl)-D-Lysine (Boc-D-Lys-OH) (Chem-Impex, cat. No. 05507)

Saturated aqueous sodium chloride solution (brine)

Sodium Bicarbonate (Macron chemicals, cat. No. 1-30850)

Trifluoroacetic acid (J.T. Baker, cat. No. W729) ! CAUTION: Highly corrosive

High quality anhydrous Dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma, cat No. 276855) ! CAUTION DMSO is inflammable, irritant and a permeator: Avoid contact with skin and eyes.

Ethanol 200 Proof (100%) (Fischer Scientific, cat No. 04-355-222) ! CAUTION: Flammable

Phosphate buffered saline (Sigma Aldrich, cat. No. P4417)

Growth media appropriate for the growth of the bacteria under investigation such as Luria Broth (LB) sterilized by autoclaving (Sigma Aldrich, cat. No. L3397)

Solid growth media appropriate for the growth of the bacteria under investigation such as pre-poured LB Agar Plates (Sigma Aldrich, cat. No. L5542)

Agarose (SeaKem LE AGAROSE, LONZA, cat. No. 50000)

Vaseline (also called petrolatum)

Lanolin

Parafin wax

EQUIPMENT

Aluminum foil

Argon tank

Balloons

C18 column for high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

Cotton

Erlenmeyer flasks

Exhaust flow hood

1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectrometers

HPLC apparatus with preparatory reversed-phase C18 column

Luna C18 reverse-phase HPLC column (10 micron pore size, 30 mm internal diameter and a length of 250 cm)

Luna C18 reverse-phase HPLC column (5 micron pore size, 21.2 mm internal diameter and a length of 250 cm)

Magnetic stir bars

10 µL microsyringe

Lyophilization flasks

Lyophilizer

Propane torch

Reflux condenser

Rotary evaporator

Round-bottomed flasks

Rubber septa

Separatory funnels

Syringe needles (BD PrecisionGlide™, 21G × 1 ¼)

High vacuum pump

Eppendorf polypropylene microcentrifuge tubes, 1.5 mL, sterilized by autoclaving (Fischer Scientific, cat No. 05-402-24B), sterilized

Tubes appropriate for the growth of the bacteria under investigation such as glass culture tubes (rimless 18 mm × 150 mm, Fischer Scientific, cat No. 11587403) and Culture Tube Closures (20 mm, Fischer Scientific, cat No. 05-888-1D)

Incubator, appropriate for the optimum growth of the desired bacterial species

A temperature controlled shaker suitable for bacterial growth in microcentrifuge tubes, such as a Thermomixer (Fischer Scientific, cat No. 05-400-200).

Vortex mixer

Microcentrifuge

0.2-µm pore size Nylon Membrane, 25 mm DMSO Safe Acrodisc Syringe Filters (PALL, Part no. 4433)

0.2-µm pore size cellulose acetate filters

3 mL Sterile Luer Lock Syringes (BD, product no. 309657)

A fluorescence microscope equipped with appropriate excitation/emission filters that cover the excitation/emission maxima of FDAAs (Table 2). For example a Nikon 90i fluorescence microscope equipped with a Plan Apo 100×/1.40 Oil Ph3 DM objective and a Chroma 83700 triple filter cube.

Glass slides (25 × 75 mm, 1.0 mm thick, VWR, cat. No. 48300-025)

Glass coverslips (22 × 22 mm, No. 1.5, VWR, cat. No. 48366-227)

Spectrophotometer suitable for measuring at 600 nm or McFarland Turbidity Standards (Set of 1–10, Northeast Laboratory Services, cat. No. M1100)

Sterile Cryogenic Vials for bacterial freezer stocks (2 mL, Polypropylene, VWR, cat No. 89094-806)

Sterile inoculating loops (1 µL, VWR, cat. No. 12000-808)

Bunsen Burner

Micropipetters P2 (Fisher cat. No. F144801G Gilson Inc), P20 (cat. No. F123600G), P200 (cat. No. F123601G), P1000 (cat. No. F123602G)

Sterile pipette tips for P2 & P20 (Fisher cat. No. F171100G Gilson Inc), for P200 (cat. No. F171300G), and for P1000 (cat. No. F171500G).

Propipetters - Fisher cat. No. 03-391-250 Argos Technologies Omega Single-Channel Pipet Controller

Sterile serological pipettes 10 mL (Fisher cat. No. 13-678-12E Fisherbrand) and 50 mL (cat. No. 13-678-14C Fisherbrand)

REAGENT SETUP

Wash buffer

For washes, 1 × Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) can be used. 1 × PBS (pH 7.4) can either be made by dissolving commercially available tablets in water or from scratch. To make it from scratch, dissolve 8 g NaCl, 0.2 g KCl, 1.78 g Na2HPO4-2H2O and 0.27 g KH2PO4 in 1 L distilled water and filter sterilize using 0.2-µm pore size cellulose-acetate filters. Acidic, basic or strong red-ox buffers should be avoided as they can modify dye molecules irreversibly.

Sterile technique

For consistent labeling results, the bacterial culture under investigation should be kept free of contaminants. Toward this end, “sterile technique” must be used throughout the labeling experiments. Before starting an experiment, the relevant surfaces (the laboratory bench, the pipettes, etc.) should be wiped with 70% EtOH. Furthermore, transfer of cultures or buffers should be done close to a lit Bunsen burner, which provides an updraft of heated air that helps prevent contamination. Finally, pre-sterilized disposables, such as inoculating loops, tips, pipettes, plates tubes must be used throughout and their exposure to open air must be limited when not in immediate use. Once the labeling experiment is completed, the fixation, washing steps, and imaging can be performed under non-sterile conditions.

Preparation of sterile liquid media

For reproducible results, the labeling experiments must be done with pure cultures. This requires the use of a sterile growth medium. As a common nutrient-rich liquid medium, LB Broth supports the growth of a variety of different species. In order to prepare 1 L sterile LB Broth, add 15.5 g of LB Broth powder into 1 L distilled water and stir using a magnetic stirrer with warming until the powder dissolves. Autoclave for 30 min at 121°C in order to sterilize. For other species that may require more specialized growth media follow the media recipes available at http://www.atcc.org/.

Inoculation and growing bacteria in liquid and on solid media

A liquid culture can be started by transferring some cells from freezer stocks or from a single colony formed on a nutrient agar plate into the liquid medium. This can be done by scratching a freezer stock or touching a colony with the tip of a sterile inoculating loop. Grow the bacteria using the optimal conditions and measure the increase in optical density (see below). For example, a well-aerated E. coli inoculate in LB can show growth in the form of a visible cloudiness of the liquid medium within 3–5 hours if incubated at 37°C.

Many types of bacteria can form colonies on solid nutrient agar plates, which can be used as a short-term (1–2 weeks) strain storage method. Premade LB agar plates are commercially available. Single colonies can be obtained by the streaking technique after some cells are transferred as a small spot on the plate using a sterile inoculation loop. The large concentration of cells on this spot can be diluted by dragging a new sterile loop from this spot and by zigzagging until ~25% of the plate’s surface is covered. In order to get well isolated, single colony forming units, this should be repeated three more times each time with new sterile loops by dragging from the previous section and covering the next untouched ~25% of the plate’s surface. Once the streaking is done, the plates should be incubated lids down at under optimal growth conditions until visible colonies form. For example, E. coli can form visible colonies on LB agar within 10–12 hours if incubated at 37°C. For other species that may require more specialized growth media and conditions, follow the instructions that are available for specific species at http://www.atcc.org/.

Tracking bacterial growth

The labeling experiments should be performed with exponentially growing bacteria in order to get optimal labeling results. The exponential phase (or the log phase) follows the lag phase and precedes the stationary phase and is defined as the period where the net increase in the number of bacterial cells per unit time is proportional to the current number of cells. Generally, the optical density of liquid bacterial cultures is proportional to the concentration of bacterial cells. Thus, by following the increase of the optical density over time, one can determine if a culture is in the exponential phase. The optical density of a culture can be quantified by measuring absorbance at 600 nm, using a spectrophotometer, and following the manufacturer’s instructions. Alternatively, one can estimate optical density of a culture by comparing it to commercially available McFarland standards (roughly, the McFarland standards Numbers 1,2,3 and 4 correspond to OD600= 0.25, 0.4, 0.6 and 0.7). More specialized methods may be required for other species, such as obligate intracellular bacteria.

Making a freezer stock of bacteria

In a sterile, cryogenic, 2 mL vial, mix 900 µL of pure liquid cultures from late exponential phase with 100 µL sterile DMSO or with 100 µL sterile glycerol and mix well. Without delay, transfer the tubes to the −80°C freezer. To start a new culture, working aseptically, transfer a small volume (~1 µL) of the frozen stock into 2 – 3 mL of sterile liquid medium.

Stock solution of FDAAs

The FDAA salts are poorly soluble in water. For example, at room temperature, the water solubility (SW) of HADA is ~ 3 mM. Thus, stock solutions should be made in DMSO. Use the following formula to determine the right volume of DMSO to dissolve your pre-weighed FDAA.

where, V = Volume of DMSO to be added in µL; W= mass of the FDAA aliquot in mg; M= Molecular mass of the FDAA salt (Table 2) in g mol−1; C= desired concentration of the stock solution in mM.

The concentration of the stock solution should be determined based on the desired final DMSO concentration in the culture (usually between 0.1% – 1%). For example, in order to get 1mM FDAA and 1% DMSO final concentrations, prepare a 100 mM (100 ×) FDAA stock solution. All of the FDAAs are soluble in DMSO at least up to 1 M concentrations. Sterilization of stock solutions is not required but could be necessary for applications that require extended labeling times (> 1d). When required, the stock solutions should be filter-sterilized using 0.2-µm pore size DMSO resilient Nylon filters.

Chemical stability of FDAA stock solutions

Powdered FDAAs (in dry compartments) and stock solutions should be stored at −20°C or lower. The stock solutions should be thawed rapidly by bringing the frozen stock to room temperature. In general, excessive thawing/refreezing, or extended exposure/storage at room temperature, should be avoided. Therefore, it is recommended to divide a fresh stock solution into smaller multiple-use aliquots. No decomposition of powder FDAAs was observed over several months when kept dry and at −20°C or lower. Similarly, the potency of stock solutions remained unchanged when they were frozen and thawed ~10 times; however, significant decomposition of the material was detected when stock solutions were kept at room temperature for 30 d in the dark.

Quality control

The effective concentration of a FDAA in a stock solution can be determined in three ways: First, the stock solution can be analyzed by HPLC and the HPLC profile of the current stock solution can be compared to that of the original stock solution. This will give both the effective FDAA concentration and the distribution of any decomposition products. Preparative HPLC can be used to re-purify FDAA recovered from an old stock solution. Second, a standard curve of concentration vs. absorbance can be made from a fresh stock solution and then be used to estimate the effective FDAA concentration of an unknown stock solution. For example, HADA has a strong linear correlation of concentration and absorbance (at 400 nm) between the concentrations 1 – 50 µM in 1 × PBS (pH 7.4) and 1 % DMSO. Finally, one can compare the signal obtained with an old stock solution in parallel with a freshly prepared one, in a microscopy experiment on a model bacterium (e.g. B. subtilis). The old stock should be discarded if any decrease of signal or changes in labeling patterns are noted.

Photostability

Despite the photolability of the smaller FDAAs (NADA, and to lesser extent, HADA) during fluorescence microscopy applications, ambient light in a typical laboratory did not noticeably affect the brightness of labeled samples. Still, avoiding prolonged exposure of the samples to incident light is recommended. For experimental purposes, the photostability of a FDAA can be estimated by repeatedly exposing a field of labeled cells with typical microscopy and image acquisition set-ups. Cells that are labeled with a photo-sensitive FDAA (e.g. NADA) will exhibit a reduction of fluorescence signal with each exposure. The rate of photobleaching can be determined by calculating the % of fluorescence decrease on a cell over repeated exposures. Among the 4 FDAAs reported here, TDL is the photophysically most impressive FDAA. It is bright, extremely photostable and its red-shifted excitation helps reduce photodamage to the cells during time-lapse microscopy. While FDL and NADA are seemingly brighter than TDL, they are also prone to extensive photobleaching. HADA is moderately bright, but it is much more photostable than NADA. If constant exposure of a single cell is required (e.g. time-lapse or structured illumination microscopy), then use of TDL is recommended (followed by HADA, FDL and NADA). The choice of FDAA is more forgiving for end-point experiments (e.g. short pulses or virtual time-lapse experiments).

Fixation

In order to quench labeling reactions, we recommend the generic 70 % Ethanol (EtOH) or paraformaldehyde fixation techniques. Given its convenience and its chemical inertness toward the peptidoglycan cell wall, EtOH fixation can be followed as the starting point. One should note that EtOH fixation causes an apparent loss of the cell pellet once the fixed cells are rehydrated in an aqueous solution (e.g. 1 × PBS). Furthermore, in some Gram-positive species such as B. subtilis, EtOH fixation results in partly phase-transparent (i.e. hollow) cells, which does not appear to affect the cell wall structure. In S. pneumoniae, EtOH fixation causes complete autolysis of the cells upon rehydration, which can partly be overcome by heat-killing the cells before the EtOH fixation. Glutaraldehyde fixation should be avoided, since it causes high background signal presumably via non-specific cross-linking of free FDAAs.

EQUIPMENT SETUP

HPLC

FDAAs were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The HPLC instrument should be set up according to the manufacturer’s recommendations/specifications.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Mass spectral data are recorded on the following instruments: 1) Waters LCT Classic Electrospray time-of-flight analyzer with an Agilent capillary HPLC inlet; 2) Sciex API III electrospray quadrupole with a direct infusion inlet, or, 3) Finnigan MAT-95. Sample ionization is achieved through use of chemical ionization (CI) or electron impact (EI).

Cell culture

Cells may be cultured in any growth supporting media. The only requirement for labeling is active cell growth at the time of FDAA addition.

Washes

Although excess FDAAs can be removed by pipetting the supernatant of pelleted cells (1 min, max speed in a microcentrifuge, room temperature), we recommend removing the supernatant using a vacuum pump aspirator, since the labeling protocols involve several washes. In our hands, aspirating supernatants of multiple samples with the same pipette tip significantly reduced the dead-time between washes and did not cause a noticeable cross-contamination.

Imaging

HADA can be imaged in the DAPI channel, NADA and FDL can be imaged in the FITC channel, and TDL can be imaged in the TAMRA channel on a conventional wide-field fluorescent microscope. See also Table 2.

Evaluation of labeling

In practice, the quality of the FDAA labeling can be defined as the higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of fluorescence on imaged cells compared to the untreated or to the fluorescent L-amino acid (FLAA) treated controls (Figure 4 c–d). Such a higher SNR not only determines if the labeling is specific, but also increases the contrast (or quality) of the images (Figure 4 c). Although SNR depends on a variety of instrumental factors such as optics, camera sensitivity, filters, strength of excitation light etc., the user can still increase the specific SNR on cells following any of the following suggestions (detailed in the introduction): 1- Use the brightest FDAA possible. 2- Minimize background fluorescence by thoroughly washing away any excess and unbound FDAA. (Figure 4 c–d) 3- Use the excitation & emission filter sets that are matched to the FDAA employed. 4- Increase the strength of the excitation light or the exposure time. Because of numerous difficult-to-control experimental parameters, relating fluorescence intensity to the actual number of FDAAs on a cell is challenging. However one can still make reliable, quantitative comparisons of labeling efficiencies between different conditions or bacterial species as long as the used FDAA and all the other sample handling/imaging conditions are identical.

PROCEDURE

Synthesis of FDAAs

-

1|The FDAAs used in these studies; HADA, NADA, FDL and/or TDL, were prepared by following the protocols described in sections A-D, respectively.

- Synthesis of HADA (Steps (i–vi) • TIMING 30 min); (Steps (vii–viii) • TIMING 2h 15 min); (Step (ix) • TIMING 17 h 15 min); (Steps (x–xvii) • TIMING 1h 15 min); (Steps (xviii–xix) • TIMING 1 h) ; (Steps (xx–xxiii) • TIMING 3 h) ; (Step (xxiv) • TIMING 24 h)

- Seal a 100-mL round-bottomed flask containing a magnetic stir bar with a rubber septa.

- Pierce the septa with a syringe needle attached to a high vacuum line and place the flask under vacuum.

-

Using a propane torch, carefully heat the flask evenly across the rounded surface only for one minute.■PAUSE POINT: The round-bottomed flask may also be oven-dried.

-

Allow the flask to cool to room temperature while still under vacuum for 10–15 minutes.Fill a balloon with argon gas and affix a syringe with a two-way tap and a needle.■PAUSE POINT: Nitrogen gas may be used in place of argon

- Pierce the septa with the argon balloon needle and then remove the vacuum line.

-

Remove the septa and add 300 mg (1.455 mmol) 7-hydroxycoumarin-3-carboxylic acid to the flask, add 236 mg carbonyldiimidazole (1.455 mmol), and reseal the flask with the septa and argon balloon.Δ CRITICIAL STEP: Carbonyldiimidazole is moisture sensitive. Quickly weigh the solid and transfer to the reaction flask. Store the reagent in a dry desiccator for future use.

- Add anhydrous dimethylformamide (14.5 mL) via an oven-dried syringe and stir at room temperature for 2 h.

- Remove the septa and add 297 mg Nα-Boc-2,3-diaminopropionic acid (1.455 mmol) in one portion, reseal the flask with septa and argon balloon, and stir overnight (17 h).

- Remove the solvent on a rotary evaporator under vacuum and dilute the product with ethyl acetate (100 mL).

- Transfer the solution to a 250 mL separatory funnel.

- Wash with 1 M aqueous hydrochloric acid (50 mL).

- Wash with distilled water (100 mL).

- Wash with saturated aqueous sodium chloride (50 mL).

- Transfer the organic layer to a 200 mL Erlenmeyer flask, dry over anhydrous sodium sulfate for 15 min, and filter into a 250 mL round-bottomed flask.

- Remove the solvent on a rotary evaporator under vacuum.

-

To remove any traces ethyl acetate, redissolve the product in dichloromethane and dry on a rotary evaporator three times.■PAUSE POINT: The product can be stored in a freezer overnight at −20°C.

- Without further purification, add a magnetic stir bar to the flask and treat the product with a 1:1 solution of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) /dichloromethane (10 mL).

- Stir at room temperature for 30 minutes, remove the solvent on a rotary evaporator, and dry under high vacuum for an additional 30 minutes.

- Dissolve the product in 15 mL acetonitrile/water (1:1).

- Purify HADA by reversed-phase HPLC with a gradient of acetonitrile in water with 0.1 % TFA (10–90% MeCN for 10 min, eluting at 40 mL min−1). The product elutes at 6.0 min on a 10 micron Luna C18 column with a 30 mm internal diameter and a length of 250 cm.

- Combine the product fractions in a 500 mL round-bottomed flask.

-

Remove the majority of the acetonitrile on a rotary evaporator.! CAUTION: Mixtures of acetonitrile/water will bump easily. Slowly increase the vacuum pressure at 25°C to avoid this problem.

-

Transfer the remaining solution to a 300 mL lyophilization flask to lyophilize the final product. The powder will be the TFA salt of HADA.■PAUSE POINT: Store at −20°C. No decomposition was detected in at least 6 months.

- Synthesis of NADA (Steps (i–vii) • TIMING 30 min); (Step (viii) • TIMING 1h); (Steps (ix–xviii) • TIMING 1 h 30 min); (Steps (xix–xxi) • TIMING 3 h); (Step (xxii) • TIMING 24 h); (Step (xxiii) • TIMING 15 h)

- Add a magnetic stir bar to 25 mL round-bottomed flask.

- Add 100 mg Nα-Boc-D-2,3-diaminopropionic acid (0.49 mmol).

- Add 123 mg sodium bicarbonate (1.47 mmol).

- Add 1.8 mL water and partially dissolve the mixture in a preheated 55°C oil (or water) bath.

- In a test tube, prepare a solution of 108 mg 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan (0.539 mmol) in 8.5 mL methanol.

- Add the methanolic solution dropwise over 10 min to the reaction flask.

- Affix a reflux condenser with cold water running throughout to the reaction flask.

- Stir the reaction at 55°C for 1 h.

- Remove the solvent on a rotary evaporator under vacuum.

- Acidify the product residue with 1 M aqueous hydrochloric acid (pH 3–4).

- Transfer the mixture to a 250 mL separatory funnel and rinse the round-bottomed flask with dichloromethane to recover all remaining product.

- Extract with dichloromethane (50 mL) three times.

- Combine the organic extracts and wash with saturated aqueous sodium chloride (50 mL).

- Transfer the organic layer to a 200 mL Erlenmeyer flask, dry over anhydrous sodium sulfate for 15 min, and filter into a 250 mL round-bottomed flask.

-

Remove the solvent on a rotary evaporator under vacuum.■PAUSE POINT: The product can be stored in a freezer overnight at −20°C.

- Without further purification, add a magnetic stir bar to the flask and treat the solid with 4 M hydrochloric acid in dioxane (10 mL).

- Stir the reaction at room temperature for 30 min.

-

Remove the solvent on a rotary evaporator.Δ CRITICIAL STEP: The product is not stable at this point. Purification must be performed as soon as possible.

-

Immediately dissolve the product in 1:1 HPLC grade acetonitrile/water (10 mL).? TROUBLESHOOTING

- Purify NADA by reversed-phase HPLC with a gradient of acetonitrile in water with 0.1 % TFA (20–90% MeCN for 10 min, eluting at 40 mL min−1). The product elutes at 5.0 min on a 10 micron Luna C18 column with a 30 mm internal diameter and a length of 250 cm.

- Combine the pure fractions in a 250 mL round-bottomed flask and remove the majority of the acetonitrile.

- Transfer the remaining solution to a lyophilization flask and lyophilize overnight.

-

Redissolve the solid in a 1:3 mixture of acetonitrile/0.5 M aqueous hydrochloric acid and again lyophilize overnight. The powder will be the HCl salt of NADA.Δ CRITICIAL STEP: The TFA salt of the product is not stable. It must be converted to and stored as the HCl salt.■PAUSE POINT: Store at −20°C. No decomposition was detected in at least 6 months.

- Synthesis of FDL (Step (i) • TIMING 30 min); (Step (ii) • TIMING 15 min); (Step (iii) • TIMING 4 h); (Steps (iv–xi) • TIMING 1h 30 min); (Steps (xii–xiv) • TIMING 1 h); (Steps (xv–xviii) • TIMING 3 h) ; (Step (xix) • TIMING 24 h)

- Flame dry a 10 mL round-bottomed flask containing a magnetic stir bar and fill with argon as described in steps 1A(i)–(vi).

- Remove the septa and add Nα-Boc-D-Lys-OH (19.3 mg, 0.078 mmol), add fluorescein isothiocyanate (25 mg, 0.065 mmol), and reseal the flask with the septa and argon balloon.

- Add anhydrous dimethylformamide via an oven dried syringe and stir the reaction at room temperature for 4 h.

- Remove the solvent on a rotary evaporator.

- Dissolve the residue in ethyl acetate (10 mL).

- Transfer the solution to a 50 mL separatory funnel.

- Wash with 1 M aqueous hydrochloric acid (10 mL).

- Wash with saturated aqueous sodium chloride (10 mL).

- Collect the organic layer in a 50 mL Erlenmeyer flask.

- Dry the organic layer over anhydrous sodium sulfate for 15 min.

-

Filter the solution into a 100 mL round-bottomed flask and remove the solvent on a rotary evaporator.■PAUSE POINT: The product can be stored in a freezer overnight at −20°C.

- Without further purification, add a magnetic stir bar the flask and treat the product with 1:1 trifluoroacetic acid/dichloromethane (10 mL).

- Stir the reaction at room temperature for 30 min.

- Remove the solvent on a rotary evaporator.

- Dissolve the crude product in 2:3 HPLC grade acetonitrile/water (10 mL).

- Purify FDL by reversed-phase HPLC with a gradient of acetonitrile in water with 0.1 % TFA (30–45% MeCN for 10 min, eluting at 40 mL min−1). The product elutes at 5.1 min on a 10 micron Luna C18 column with a 30 mm internal diameter and a length of 250 cm.

- Combine the product fractions in a 250 mL round-bottomed flask.

- Remove the majority of the acetonitrile on a rotary evaporator.

-

Transfer the remaining solution to a 300 mL lyophilization flask to lyophilize the final product. The powder will be the TFA salt of FDL.■PAUSE POINT: Store at −20°C. No decomposition was detected in at least 3 months.

-

Synthesis of TDL (Step (i) • TIMING 30 min); (Steps (ii–iv) • TIMING 15 min); (Step (v) • TIMING 15 h); (Steps (vii–ix) • TIMING 1h); (Steps (x–xi) • TIMING 3 h); (Step (xii) • TIMING 12 h)For custom synthesis of novel FDAAs, one can follow these steps by simply changing the commercially available succinimidyl ester activated fluorophore and/or the Boc protected D-diamino acid linker in Step (ii) as long as the molar ratios are kept constant. The HPLC profile in Step (xi) will change depending on the product.

- Flame dry a 5 mL round-bottomed flask containing a magnetic stir bar and fill with argon as described in steps 1A(i)–(vi).

- Remove the septa and add 5 mg (0.0095 mmol) 5-(and 6-) carboxytetramethylrhodamine succinimidyl ester, add 3.3 mg Nα-Boc-D-Lys-OH (0.0134 mmol), and reseal the flask with the septa and argon balloon.

- Add 0.2 mL of anhydrous dimethylformamide via an oven dried syringe.

- Add 2.5 µL diisopropylethylamine via a 10 µL microsyringe.

- Stir the reaction at room temperature overnight (15 h).

-

Remove the solvent in a rotary evaporator.■PAUSE POINT: The product can be stored in a freezer overnight at −20°C.

- Without further purification, add a magnetic stir bar the flask and treat the product with 1:1 trifluoroacetic acid/dichloromethane (2 mL).

- Stir the reaction at room temperature for 30 min.

- Remove the solvent on a rotary evaporator.

- Dissolve the product 1:4 HPLC grade acetonitrile/water (3 mL).

- Purify TDL by reversed-phase HPLC with a gradient of acetonitrile in water with 0.1 % TFA (20–40% MeCN for 10 min, eluting at 20 mL min−1). The first product isomer elutes at 7.9 min and the second elutes at 9.1 min on a 5 micron Luna C18 column with a 21.2 mm internal diameter and a length of 250 cm.

-

Transfer the remaining solution to a 60 mL lyophilization flask to lyophilize the final product. The powder will be the TFA salt of TDL.■PAUSE POINT: Store at −20°C. No decomposition was detected in at least 3 months.

Labeling with FDAAs

-

2|

From a −80°C bacterial freezer stock, inoculate the cells into sterile liquid media and grow cells using optimal, species-specific conditions at least until exponential growth is achieved.

-

3|

Dilute the culture to OD600 = 0.05 in fresh medium and grow cells further until OD600 = ~ 0.4.

Δ CRITICIAL STEP: FDAA incorporation is best characterized in exponentially growing cultures. The three doublings in OD ensure that exponential phase growth has been achieved even in the case of a starting stationary phase culture.

-

4|

Prepare a desired stock solution(s) of FDAA in DMSO as described in the REAGENT SETUP.

Δ CRITICIAL STEP: The DMSO stock solutions of FDAAs should be stored at −20°C or lower temperatures as they are observed to decay at prolonged exposure to room temperature. The stocks can be kept at −20°C frozen for many months and thawed at least 10–15 times without decomposing.

-

5|If the species under investigation was not stained by FDAA before, follow the steps in Option A using HADA as the FDAA. Otherwise, choose any of the FDAAs and their reported optimal concentrations6, and any of the labeling options suitable for the specific application (options B–F).

- Determining species-specific optimum FDAA concentration with a long pulse (Steps (i–ii) • TIMING 30 min); (Steps (iii–iv) • TIMING 10 min); (Step (v–vi) • TIMING determined by growth rate of the species); (Steps (vi–vii) • TIMING 20 min) ; (Steps (viii) • TIMING determined by growth rate of the species)

- Serially dilute a 400 mM stock solution of HADA six times 1:2 in DMSO.

- Add 20 µL of each dilution to six sterile culture tubes; add 20 µL pure DMSO into a seventh tube as the DMSO control.

- Dilute the culture to OD600 = 0.05 in fresh LB.

-

Add 1,980 µL of the culture to each of the seven tubes and add 2 mL of the culture into the eighth tube as the growth control. This dilutes the FDAA and DMSO in each tube 100 times and gives 2-fold dilutions of FDAA final concentrations ranging from 4 mM to 125 µM, each with the final [DMSO] = 1%.? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

Incubate the culture in the desired conditions (e.g. in species-specific rich medium at optimal growth temperature). Monitor the effects of different [HADA] and DMSO (final 1 %) on growth and morphology by measuring OD600 and checking cell morphology under light microscopy after each doubling.? TROUBLESHOOTING

- When the culture reaches OD600 = 0.4 – 0.6, pellet 1 mL of the cells (1 min, max speed in a microcentrifuge, room temperature).

- Resuspend the cells in 1 mL 70% (vol/vol) ice cold EtOH and fix cells on ice for 10 – 15 min.

- In the meanwhile continue to grow the remaining culture until the cells reach stationary phase and continue to monitor for growth and morphology effects as in Step 5A(v).

-

Long pulses for end point or for time-lapse microscopy experiments (Steps (i–iii) • TIMING 15 min); (Steps (iv) • TIMING 1h)For this experiment use FDAA concentrations either already reported for long pulses6 or determined following Step 5A. In order to simplify the language of the protocol, growth and FDAA labeling conditions optimized for E. coli are described.

- To a culture tube, add 10 µL from a 50 mM FDAADMSO stock solution. (Alternatively, add 2.5 µL FDAADMSO from a 200 mM stock and 7.5 µL DMSO.)

- Dilute the culture to OD600 = 0.05 in fresh LB.

- Add 990 µL of the culture to the culture tube containing FDAA in order to get a final [FDAA] = 500 µM and [DMSO] = 1% in LB and incubate the culture shaking at 37°C.

- When the culture reaches OD600 = 0.4 – 0.6, pellet the cells (1 min, max speed in a microcentrifuge, room temperature).

-

Short pulse for detecting the site of active growth • TIMING 30 minWe define short pulse labeling as the growth of cells in the presence of FDAAs for durations that lie between 2 % to 8 % of the generation time, which we have found optimal for most species. (Figure 3, II.) Though not included in this protocol, we recommend that the user determine condition- and species-specific doubling times before the short pulses. In short pulses, the exposure to the dye is much shorter than for the long pulses. Therefore, the cells can tolerate higher FDAA and DMSO concentrations than the long pulses without showing any signs of growth defects. Thus, for a higher signal:noise during microscopy, we recommend FDAA concentrations at least 2 times higher than determined in Step 5A or used in Step 5B. In order to simplify the language of the protocol, growth and FDAA labeling conditions optimized for E. coli is followed below.

- To a culture tube, add 10 µL from a 100 mM FDAADMSO stock solution. (Alternatively, add 5 µL FDAADMSO from a 200 mM stock and complement with 5 µL DMSO.)

- Prewarm the culture tube and immediately add 990 µL of the exponentially growing culture from OD600 = ~ 0.4 in order to get a final [FDAA] = 1 mM and [DMSO] = 1% in LB.

- Incubate the culture shaking at 37°C for 15 s – 30 s.

-

Pellet the cells (1 min, max speed in a microcentrifuge, room temperature) and resuspend the cells in 1 mL 70% (vol/vol) ice cold EtOH.Δ CRITICIAL STEP: In order to increase the temporal resolution of the pulse, the user should consider fixing cells by directly adding 2.3 mL ice-cold 100% EtOH into the 1 mL culture to get a final EtOH concentration of 70 %.

- Fix cells on ice for 10 – 15 min.

-

‘FDAA-saver’ short pulse for detecting the site of active growth • TIMING 40 minAforementioned short pulses (Step 5C) has also been successfully performed on ~ 10 times concentrated cells without causing a noticeable change in labeling patterns. Following this approach significantly reduces the amount of FDAA spent per experiment. Furthermore, the volume reduction also makes handling of multiple samples easier. With this approach, sampling numerous conditions (e.g. different FDAAs) at the same time is feasible. For example, the steps described below can be conducted using multiple wells of a 48-well plate (and a plate incubator) at the same time instead of less convenient Eppendorf tubes. In order to simplify the language of this approach, growth and FDAA labeling conditions optimized for E. coli are described.

- To a 1.7 mL Eppendorf tube, add 1 µL from a 100 mM FDAADMSO stock solution.

- Pellet 1 mL of the exponential culture from OD600 = ~ 0.4 (1 min, max speed in a microcentrifuge, room temperature).

- Resuspend the pellet in 100 µL pre-warmed LB and add this concentrated culture to the prewarmed, FDAA-containing eppendorf tube in order to get a final [FDAA] = 1 mM and [DMSO] = 1% in LB.

-

Incubate the tube rocking at 37°C for 15 s – 30 s.Δ CRITICIAL STEP: Avoid using this for pulses longer than 20% of the generation time. Some species such as B. subtilis show morphological defects with longer pulses presumably because of poor aeration of the high-density cell suspension.

- Add 230 µL ice-cold 100% EtOH into the 100 µL culture to get a final EtOH concentration of 70 %.

- Add an additional 1 mL cold 70% EtOH into the tube contributing to the removal of the excess dye.

- Fix cells on ice for 10 – 15 min.

-

Virtual time-lapse using short pulses of multiple FDAAs (Steps (i–iv) • TIMING 10 min); (Steps (v–x) • TIMING 1 h)We define a virtual-time lapse microscopy experiment as the consecutive exposure of the cells to differently colored FDAAs (Figure 3, IV.), which can be used either to probe growth dynamics or as a diagnostic tool to probe effects of different conditions (e.g. antibiotics, temperature) during the respective labeling periods on growth. Here, the principle of short pulses can be used with the addition of a second (or third) round(s) of short pulse using a differently colored FDAA, followed by fixation and imaging. In such an experiment, washing cells before, between and after the each pulse with pre-warmed media normalizes effect of the multiple pulses and minimize bleed-over of the signals caused by the incorporation from the excess FDAA left from the previous round. As a proof of principle, the protocol optimized for the polarly growing, gram–positive species Streptomyces venezuelae is described below. The labeling duration and the starting OD should be adjusted for different growth rates so that the cells are kept at the exponential phase throughout a given labeling period.

- Pellet 1 mL of exponentially growing S. venezuelae culture (optimally in LB shaking at 30°C and OD600 = ~ 0.4) in an Eppendorf tube (1 min, max speed in a microcentrifuge, room temperature).

- Discard the supernatant and resuspend in 1 mL pre-warmed LB.

- Pellet the cells again (1 min, max speed), discard the supernatant and resuspend in 990 uL pre-warmed LB.

- To a culture tube, add 10 µL from a 100 mM TDLDMSO stock solution. (Alternatively, add 5 µL TDLDMSO from a 200 mM stock and complement with 5 µL DMSO.)

- Prewarm the culture tube to 30°C and immediately add the washed S. venezuelae culture in order to get a final [TDL] = 1 mM and [DMSO] = 1% in LB.

- Incubate the culture shaking at 37°C for 3 min – 6 min.

- Pellet the cells and wash the cells once with LB and resuspend in 990 uL pre-warmed LB as described in (i) – (iii).

- To a culture tube, add 10 µL from a 100 mM FDLDMSO stock solution. (Alternatively, add 5 µL FDLDMSO from a 200 mM stock and complement with 5 µL DMSO.)

- Prewarm the culture tube to 30°C and immediately add the washed S. venezuelae culture in order to get a final [FDL] = 1 mM and [DMSO] = 1% in LB.

- Incubate the culture shaking at 37°C for 3 min – 6 min.

- Pellet the cells and wash the cells once with LB and resuspend in 990 uL pre-warmed LB as described in (i) – (iii).

- To a culture tube, add 10 µL from a 100 mM HADADMSO stock solution. (Alternatively, add 5 µL HADADMSO from a 200 mM stock and complement with 5 µL DMSO.)

- Prewarm the culture tube to 30°C and immediately add the washed S. venezuelae culture in order to get a final [HADA] = 1 mM and [DMSO] = 1% in LB.

-

Incubate the culture shaking at 37°C for 3 min – 6 min.? TROUBLESHOOTING

- Pellet and, wash the cells once with pre-warmed LB (1 min, max speed in a microcentrifuge, room temperature).

-

Fix the cells by resuspending and incubating the cells in 1 mL 70% (vol/vol) cold EtOH on ice for 10 – 15 min.? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

Labeling environmental samples • TIMING 30 min – 4h 30 minFDAAs can be used to distinguish actively growing bacteria in a complex environmental sample, since almost all bacteria seem to share common mechanisms for incorporating FDAAs and since their incorporation does not require special treatment of the sample. As a proof of principle, a protocol that involves simply adding FDAAs in order to probe active bacteria in a saliva sample is described below.

- Collect ~ 1 mL saliva in a culture tube.

- To this sample, directly add 10 µL HADADMSO from a 50 mM stock solution in order to get final [HADA] = 500 µM and [DMSO] = 1%.

- Incubate the culture tube at 37°C (+ 5 % CO2, optional) for any duration between 5 minutes (for short pulses) and 4 h (for long pulses).

- Pellet the cells (1 min, max speed in a microcentrifuge, room temperature).

- Resuspend the cells in 1 mL 70% (vol/vol) ice cold EtOH and fix cells on ice for 10 – 15 min.

-

6|

Wash cells with 1 mL 1 × PBS at least 2 – 3 times until free FDAA is removed. Resuspend the cells in 20 – 100 µL PBS or LB.

! CAUTION: If this wash step follows a 70% (vol/vol) EtOH fixation step, after the first wash the pellet becomes noticeably transparent.

! CAUTION: If this wash step follows a time-lapse microscopy experiment, the suspension should be well mixed and the cell density should be adjusted to OD600 = 0.05 in order to get well separated single cells.

■PAUSE POINT: The cells can be stored at −20°C after they are resuspended in 20 – 100 µL PBS + 10%DMSO.

Microscope setup • TIMING 1h

-

7|

If the viability and continued growth of the cells is not important during the imaging follow the steps in Option A. If imaging of the cells involves time-lapse microscopy as the continuum of Step 5B, follow the steps in Option B.

Δ CRITICIAL STEP: HADA is virtually non-fluorescent in acidic pH or non-buffered water. For the maximum brightness of HADA-labeled cells, imaging in mounting media that are buffered above pH 7.0 (e.g. 1 × PBS or LB Broth) is recommended.- Preparing imaging agar pads. • TIMING 10 min

- Dissolve 0.2 g agarose in 20 mL 1 × PBS by microwaving in order to get a final 1% w/v [agarose] and bring the temperature of the solution to ~ 70°C.

- Spot ~ 200 µL of the solution on the middle of a glass microscopy slide, swiftly place a coverslip on top of this drop and gently press down before the agarose solidifies in order to make a flat, thin layer of agarose pad.

-

Once the pad is solidified, carefully remove the coverslip and air-dry the pad for no longer than 1 min.Δ CRITICIAL STEP: When the slide is not dried properly, the cells do not settle on the agarose pads, making the imaging challenging.

- Preparing nutrient agar pads for time-lapse microscopy. • TIMING 10 min

-

Dissolve 0.2 g agarose in 20 mL LB (or appropriate liquid growth medium) by microwaving in order to get a final 1% w/v [agarose] and bring the temperature of the solution to ~ 70°C.! CAUTION: Agarose solutions with nutrient media tend to boil over quickly.

- Spot ~ 200 µL of the LB – agarose solution on the middle of a glass microscopy slide, swiftly place a coverslip on top of this drop and gently press down before the agarose solidifies in order to make a flat, thin layer of agarose pad.

-

Once the pad is solidified, carefully remove the coverslip and air-dry the pad for no longer than 1 min.? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

-

8|

Spot ~ 1 µL cells on the agarose pad, gently place a new coverslip on top of the cells and seal the edges of the coverslip with 1:1:1 mixture of melted vaseline, lanolin and paraffin.

-

9|

Image cells using a fluorescence microscope and FDAA specific excitation and emission filter sets (Table 2). For the time-lapse microscopy, continue acquiring images at constant intervals up to 5–6 generations.

! CAUTION: Do not overexpose labeled cells as it may cause loss of details in labeling patterns on the acquired micrograph.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Troubleshooting advice can be found in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Troubleshooting table

| Step | Problem | Possible reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1B(xix), | Instability of NADA before purification | Cyclization of the free amino group with the NBD ring. | Decomposition of NADA is the only potential problem in any of the syntheses. Smaller scale reactions tends to give lower amounts of the decomposed product. To maximize yields, the final product must be purified immediately and converted to the corresponding HCl salt as soon as possible. |

| 5A(iv) | At certain dilutions, temperatures, and media, a precipitation of FDAAs forms | FDAA under investigation is too hydrophobic and not sufficiently water soluble. | 1- Check labeling with a dilution that does not give any precipitation. 2- Increase the final DMSO in the media. Many bacterial species will tolerate final [DMSO] up to 10%. 3- Warm the media until the precipitate dissolves. 4- Use a more hydrophilic FDAA, e.g. TDL over HADA. |

| 5A(v) | The FDAA and/or DMSO is toxic or changes cell morphology within the experimental concentration range | High levels of FDAA incorporation interferes with cell wall growth. High levels of DMSO interferes with cell growth. |

Titrate either FDAAs and/or DMSO down and determine the minimal concentrations of FDAA and/or DMSO that are innocuous to growth and morphology but that still give detectable labeling. |

| 5E(xiii) | In virtual time-lapse microscopy experiments involving multiple FDAAs: slower cell growth, i.e. lower incorporation efficiency of the most recent FDAA. | The cells will inevitably accumulate stress with every additional round of pulse labeling due to exposure to high FDAA concentrations and rigorous washing steps. | Reduce each of the FDAA concentrations and skip washes between steps. The effective concentration of the previous FDAA in the medium can still be reduced 100 – 1000 times by simply pelleting the cells, carefully discarding the supernatant and resuspending the cells in fresh medium containing the next FDAA. |

| 5E(xi) | In virtual time-lapse microscopy experiment, the signal from the first FDAA is low/absent. | In some species turnover of the PG results in a significant reduction of the signal from an incorporated FDAA during growth in the absence of that FDAA. | Utilize inherently dimmer FDAAs for the last pulses (as done with S. venezuelae example in Step 5E) and consider designing and synthesizing FDAAs using brighter organic dyes and following the principles for the synthesis of TDL (Step 1D). Such FDAAs are expected to be well tolerated especially by gram-positive or outer-membrane permeable gram-negative species. |

| 7B(iii) | The signal to noise is too low. | The nutrient agarose pad is autofluorescent. |

|