Abstract

Reward reactivity and positive emotion are key components of a theoretical, early-emerging approach motivational system, yet few studies have examined associations between positive emotion and neural reactivity to reward across development. In this multi-method prospective study, we examined the association of laboratory observations of positive emotionality (PE) at age 3 and self-reported positive affect (PA) at age 9 with an event-related potential component sensitive to the relative response to winning vs. losing money, the feedback negativity (ΔFN), at age 9 (N=381). Males had a larger ΔFN than females, and both greater observed PE at age 3 and self-reported PA at age 9 significantly, but modestly, predicted an enhanced ΔFN at age 9. Negative emotionality and behavioral inhibition did not predict ΔFN. Results contribute to understanding the neural correlates of PE and suggest that the FN and PE may be related to the same biobehavioral approach system.

Keywords: Reward, temperament, feedback negativity, positive emotionality, positive affect, event-related potentials, behavioral inhibition, negative emotionality, negative affect

A number of theorists conceptualize personality and psychopathology in terms of independent biobehavioral motivational systems (Davidson, 1992; Depue & Iacono, 1989; Gray, 1994; Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1990). Each of these models include an approach system that is hypothesized to regulate reward processing (Dillon et al., 2013) and generate positive emotions, such as exuberance and joy, which are presumed to facilitate and reinforce appetitive behavior and engagement with rewarding stimuli (Depue & Collins, 1999; Polak-Toste & Gunnar, 2006; Smillie, 2013; Watson, Wiese, Vaidya, & Tellegen, 1999; Wilt & Revelle, 2009). Consistent with this, there is evidence that reward sensitivity and positive emotionality load on the same latent factor in children and adults (Lucas, Diener, Grob, Suh, & Shao, 2000; Olino, Klein, Durbin, Hayden, & Buckley, 2005). Most theorists assume that the approach system is fundamental to human functioning and survival, and emerges early in development. In addition, individual differences in the strength of this system are thought to contribute to stable variations in reward sensitivity and dispositional positive affect (PA; also referred to as positive emotionality, extraversion, and surgency; Putnam, 2012).

The approach system is typically contrasted with the withdrawal (Davidson, 1992) or behavioral inhibition (Gray, 1994) system. This system is characterized by sensitivity to signals of threat and punishment, and dispositional negative emotionality (NE) and behavioral inhibition (BI; Fox, Henderson, Marshall, Nichols, & Ghera, 2005; Kennis, Rademaker, & Geuze, 2013; Watson et al., 1999). While NE and BI are correlated temperament traits, NE refers to the tendency to experience a broad range of negative emotions (Clark & Watson, 1999), whereas BI refers specifically to the tendency to be fearful and hesitant in novel situations (Kagan, 1984).

Despite the rich theoretical literature on the approach system, empirical studies examining links between the neural processes associated with reward sensitivity and temperamental positive emotionality (PE) are surprisingly limited (Kennis et al., 2013; Wilt & Revelle, 2009). Much of the existing work has examined resting electroencephalogram (EEG) activity, with adult studies linking greater self-reported approach system sensitivity to greater left prefrontal activation (Sutton & Davidson, 1997; Tomarken, Davidson, Wheeler, & Doss, 1992). More recently, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of adults and adolescents have suggested that self-reported approach system sensitivity and extraversion are associated with enhanced activation of the ventral striatum and medial orbitofrontal cortex in response to rewards (Cohen, Young, Baek, Kessler, & Ranganath, 2005; Forbes et al., 2010; Kennis et al., 2013; Simon et al., 2010). Given that individual differences in the approach system are presumed to emerge early in life, it is important to evaluate associations across development. However, the literature on reward reactivity and PE has typically focused on older adolescents and adults and used cross-sectional designs.

On the other hand, a number of studies have examined relationships between BI in early childhood and subsequent individual differences in neural reactivity to both threat and reward-related stimuli. For example, individuals classified as high BI in early childhood show greater right frontal EEG asymmetry, hypothesized to be a marker of withdrawal system reactivity (Fox et al., 2005), as well as enhanced electrocortical measures of error monitoring (McDermott et al., 2009). In addition, early BI has been related to greater striatal activation in response to cues indicating potential for reward and loss (Bar-Haim et al., 2009; Guyer et al., 2006) and in response to negative feedback (Helfinstein et al., 2011). These studies raise the question of whether the link between reward reactivity and temperamental emotionality is specific to approach system-related affective styles (e.g., PE).

The feedback negativity (FN) is an event-related potential (ERP) component characterized by a relative negativity in response to monetary losses compared to rewards that peaks approximately 250-300 ms over frontocentral recording sites that has been linked to activation in the ventral striatum and medial prefrontal cortex (Carlson, Foti, Mujica-Parodi, Harmon-Jones, & Hajcak, 2011; Gehring & Willoughby, 2002; Foti, Weinberg, Dien, & Hajcak, 2011; Hajcak, Moser, Holroyd, & Simons, 2006). Though the FN has previously been conceptualized as an enhanced negativity following losses, there is evidence to suggest that it may be better characterized as a relative positivity in response to rewards that is reduced or absent following losses (Foti, Weinberg, et al., 2011; Holroyd, Pakzad-Vaezi, & Krigolson, 2008). The FN is often analyzed as the loss minus gain difference score (ΔFN) in order to isolate variation in the waveform attributed to processing of outcome valence (Dunning & Hajcak, 2007; Foti, Kotov, Klein, & Hajcak, 2011; Luck, 2005), and ΔFN has previously been related to neural reward circuitry using fMRI and to behavioral and self-report measures of reward sensitivity (Bress & Hajcak, 2013; Carlson et al., 2011).

The FN may be an economical and valid measure of reward system reactivity that can be applied across development. Cross-sectional research in adults has linked an enhanced FN to greater extraversion (Smillie, Cooper, & Pickering, 2011); however, it remains unclear whether approach-related temperament systems such as PE, measured in early childhood, relate to the FN later in development. Also, research is needed to evaluate the extent to which associations between the FN in monetary reward tasks are specific to PE, rather than temperament styles linked to the withdrawal system. Recently, several adult studies have examined associations between the FN and self-reported withdrawal/behavioral inhibition system temperament constructs in adults with mixed findings. Santesso and colleagues (2012) found that greater NE predicted an enhanced FN to negative performance feedback in a monetary incentive task. On the other hand, Lange, Leue, and Beauducel (2012) found that adults high in behavioral approach system sensitivity exhibited an enhanced FN when reward feedback changed to non-reward feedback, while people higher in behavioral inhibition system sensitivity showed a reduced FN.

The primary goal of the current study was to evaluate prospective associations between the FN and PE from early to late childhood. We used laboratory observations to assess temperament in a large sample of three-year-old children. Approximately six years later, children completed a monetary reward task while ERPs were recorded and a self-report measure of temperament. We hypothesized that greater early PE would be associated with an enhanced FN. Demonstrating this effect across a six-year period spanning early to late childhood, a period of immense neural and socioemotional change (Giedd & Rapoport, 2010; Monk, 2008), provides a particularly stringent test of the relationship between PE and the FN. A secondary aim of the study was to evaluate whether self-reported PA concurrently related to the FN, and if so, whether the association between early PE and the FN remained significant when accounting for concurrent self-reported PA. Given the low correlations between laboratory and questionnaire measures of child temperament (Hayden, Klein, & Durbin, 2005; Mangelsdorf, Schoppe, & Buur, 2000), obtaining converging results across both measurement methods would provide greater support for a link between PE and the FN. Finally, a third aim was to explore the specificity of the PE-FN association by examining whether observed NE and BI at age 3 and self-reported NE at age 9 predicted the FN.

Method

Participants

Participants were part of a larger community sample (N=559) recruited through a commercial mailing list for a prospective study of early temperamental emotionality and risk for internalizing disorders (Olino, Klein, Dyson, Rose, & Durbin, 2010). Three-year-old children with no significant medical conditions or developmental disabilities and living with at least one English-speaking biological parent were eligible to participate. A subset of 428 children participated in the second assessment approximately six years later. The children who completed the EEG did not significantly differ from the rest of the sample with regard to early PE, NE, or BI. Data from 1 participant was lost due to a technical error, and data from 43 participants were excluded due to poor EEG quality and from 3 participants due to temperament data points that were significant outliers according to Grubbs Test (Grubbs, 1969, p<.05). The final sample included 381 children (45.1% female). With regard to ethnicity, 7.6% of the sample was of Hispanic or Latino background. The sample was 94.8% Caucasian, 2.9% African American, and 2.4% Asian. The mean age was 3.55 years (SD=0.26) at the first assessment and 9.20 years (SD=0.40) at the second assessment.

Procedure

Both phases of the study were approved by the Stony Brook University Institutional Review Board. Parents provided written informed consent prior to the start of each assessment. When the children were approximately three years old, families visited the laboratory for the temperament assessment described below. Families were invited back to the lab as close as possible to the child’s ninth birthday for a battery that included questionnaires and the reward task. During the second visit, EEG sensors were attached and children were told that they could win up to $5 in a guessing task. Children were instructed to press the left or right mouse button to select a door and completed five practice trials prior to beginning the reward task described below. Children also completed a questionnaire assessing trait positive and negative affect (described below).

Measures

Observational Temperament Assessment

At age three, each child and a parent visited the laboratory for an observational assessment of temperament. The assessment included a standardized set of 12 episodes: 11 episodes were from the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB; Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley, & Prescott, 1995) and one was adapted from a Lab-TAB episode. A previous study found moderate stability of laboratory ratings of temperament from ages 3 to 7 and moderate concurrent and longitudinal associations between Lab-TAB ratings and home observations (Durbin, Hayden, Klein, & Olino, 2007). Tasks were videotaped and later coded. No episodes presumed to evoke similar affective responses occurred consecutively, and each episode was followed by a brief play break to allow the child to return to baseline. The parent remained in the room with the child for all episodes except “Stranger Approach” and “Box Empty” but was instructed not to interact with the child (except in “Pop-Up Snakes”) and was seated facing at a right angle from the experimenter and child and given questionnaires to complete.

The episodes, in order of presentation, were as follows:

1. “Risk Room.” Child explored a set of novel and ambiguous stimuli, including a Halloween mask, balance beam, and black box.

2. “Tower of Patience.” Child and experimenter alternated turns in building a tower. The experimenter took increasing amounts of time before placing her block on the tower.

3. “Arc of Toys.” Child played independently with toys for 5 min before the experimenter asked the child to clean up.

4. “Stranger Approach.” Child was left alone briefly in the room before a male accomplice entered, speaking to the child while slowly walking closer.

5. “Make That Car Go.” Child and experimenter raced remote-controlled cars.

6. “Transparent Box.” Experimenter locked an attractive toy in a transparent box, leaving the child alone with a set of nonworking keys. After a few minutes, the experimenter returned and told the child that she had left the wrong set of keys. The child used the new keys to open the box and play with the toy.

7. “Exploring New Objects.” Child was given the opportunity to explore a set of novel and ambiguous stimuli, including a mechanical spider, a mechanical bird, and sticky soft gel balls.

8. “Pop-Up Snakes.” Child and experimenter surprised the parent with a can of potato chips that actually contained coiled snakes.

9. “Impossibly Perfect Green Circles.” Experimenter repeatedly asked the child to draw a circle on a large piece of paper, mildly criticizing each attempt.

10. “Popping Bubbles.” Child and experimenter played with a bubble-shooting toy.

11. “Snack Delay.” Child was instructed to wait for the experimenter to ring a bell before eating a snack. The experimenter systematically increased the delay before ringing the bell.

12. “Box Empty.” Child was given an elaborately wrapped box to open under the impression that a toy was inside. After the child discovered the box was empty, the experimenter returned with several toys for the child to keep.

Coding procedures

Coding of PE and NE was based on Durbin, Klein, Hayden, Buckley, & Moerk (2005). Each display of facial, bodily, and vocal positive affect, fear, sadness, and anger in each episode was rated on a 3-point scale (low, moderate, high). The positive affect scale was defined as the frequency and intensity of positive verbalizations, smiling and joyful body movements. Ratings were summed separately within each channel (facial, bodily, vocal) across the 12 episodes, standardized, and summed across the three channels to derive total scores for positive affect, fear, sadness, and anger. Interest was rated on a single 4-point scale (none, low, moderate, and high) for each episode based on the child’s comments about the activity and how engaged the child was in play. Interest ratings were then summed across the 12 episodes. PE consisted of the sum of the standardized positive affect and interest variables, consistent with evidence that positive affect and interest load on the same factor (Dyson, Olino, Durbin, Goldsmith, & Klein, 2012). NE was the sum of the standardized sadness, fear, and anger variables.

The coding of BI was designed to capture specific types of behaviors identified by Kagan (1984) and followed Goldsmith’s scoring system (Goldsmith et al., 1995; Pfeifer et al., 2002). BI was coded by dividing the three episodes specifically designed to assess BI (“Risk Room,” “Stranger Approach,” and “Exploring New Objects”) into 20- or 30-s epochs, and rating a series of affective and behavioral codes for each epoch (Goldsmith et al., 1995). Within each epoch, a maximum intensity rating of facial, bodily, and vocal fear was coded on a scale of 0 (absent) to 3 (highly present and salient). Based on previous studies using the Lab-TAB (Durbin et al., 2005; Pfeifer et al., 2002), BI was computed as the average standardized ratings of latency to fear (reversed); and facial, vocal, and bodily fear (“Risk Room,” “Stranger Approach,” and “Exploring New Objects”); latency to touch objects; total number of objects touched (reversed); tentative play; referencing the parent; proximity to parent; referencing the experimenter; and time spent playing (reversed; “Risk Room” and “Exploring New Objects”); startle (“Exploring New Objects”); sad facial affect (“Exploring New Objects” and “Stranger Approach”); and latency to vocalize; approach toward the stranger (reversed); avoidance of the stranger; gaze aversion; and verbal/nonverbal interaction with the stranger (reversed; “Stranger Approach”).

Most episodes were coded by different raters. PE and NE had adequate internal consistency (α = .82 and .74, respectively) and interrater reliability (intraclass correlations [ICC] = .89 and .82, respectively; N = 35). BI exhibited good internal consistency (α = .80) and interrater reliability (ICC = .88, N = 28). To reduce skewness and kurtosis, a constant was added to NE and BI scores in order to eliminate negative values and then a log transformation was applied. No transformations were made to PE. PE was not significantly correlated with NE but was negatively associated with BI. Scoring of BI and NE both include measures of fear-related behavior; thus, BI and NE were moderately correlated (Table 1). More detail regarding relationships between Lab-TAB temperament variables is available in Dyson et al. (2012).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Associations between Variables.

| T1 Age | T2 Age | Sex | Lab-TAB PE |

Lab-TAB NE |

Lab- TAB BI |

AFARS PA | AFARS NA |

ΔFN | Loss FN | Gain FN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | −.01 | .02 | - | ||||||||

| Lab-TAB PE | .19*** | .06 | −.08 | - | |||||||

| Lab-TAB NE | −.04 | .09 | −.09 | −.01 | - | ||||||

| Lab-TAB BI | −.10* | .03 | −.16** | −.23*** | .43*** | - | |||||

| AFARS PA | −.03 | −.03 | −.20*** | .00 | −.06 | −.01 | - | ||||

| AFARS NA | .03 | .05 | −.02 | −.01 | .08 | .01 | −.07 | - | |||

| ΔFN | −.07 | .02 | −.18** | −.11* | .08 | .10* | −.09 | .02 | - | ||

| Loss | FN | −.05 | .10* | −.01 | −.06 | .14* | .06 | −.02 | −.01 | .39*** | - |

| Gain FN | .01 | .09 | .14** | .03 | .08 | −.02 | .05 | −.02 | −.43*** | .67** | - |

| M(SD) | 3.55(.26) | 9.20(.40) | - | .09(1.76) | .55(.25) | .63(.20) | 24.73(3.95) | 6.23(3.43) | −4.58(7.48) | 6.59(9.12) | 11.17(9.31) |

| Range | 2.93-4.18 | 8.75- 10.92 |

- | −5.09- 6.09 |

0.00-1.39 | 0.00- 1.37 |

10.00-30.00 | 0.00-19.00 | −23.39- 15.76 |

−24.25- 37.88 |

−18.31- 41.57- |

| % Male | 54.9% |

p < .001;

p < .01;

p ≤ .05

Self-Report Measure of Positive and Negative Emotionality

At the age 9 assessment, children completed the positive and negative affect scales of the Affect and Arousal Scale (AFARS; Chorpita, Daleiden, Moffitt, Yim, & Umemoto, 2000). The AFARS is a child self-report measure designed to assess trait dimensions of the tripartite model of emotion and has demonstrated acceptable test-retest reliability, convergent and discriminant validity (Daleiden, Chorpita, & Lu, 2000). Children are asked to rate how true each item is with respect to their usual feelings from 0 (never true) to 3 (always true). The positive affect (PA) scale consists of 10 items and possible scores can range from 0 to 30. The negative affect (NA) scale consists of 8 items and scores can range from 0 to 24.

Reward Task

The reward task was administered using Presentation software (Neurobehavioral Systems) and was similar to a version used in previous studies (e.g., Dunning & Hajcak, 2007). The task consisted of 60 trials, presented in three blocks of 20 trials. At the beginning of each trial, participants were presented with an image of two doors and were instructed to choose one door by clicking the left or right mouse button. The doors remained on the screen until the participant responded. Next, a fixation mark (+) appeared for 1000 ms, and feedback was presented on the screen for 2000 ms. Participants were told that they could either win $0.50 or lose $0.25 on each trial. Wins were worth more than losses because the response to losses is thought to be stronger than the response to wins (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981, 1992), and because this allowed participants to accrue money across the task. A win was indicated by a green “↑,” and a loss was indicated by a red “↓.” Next, a fixation mark appeared for 1500 ms and was followed by the message “Click for the next round”, which remained on the screen until the participant responded and the next trial began. Across the task, 30 gain and 30 loss trials were presented in a random order.

EEG Data Acquisition & Processing

The continuous EEG was recorded using a 34-channel BioSemi system based on the 10/20 system (32 channel cap1 with Iz and FCz added). Two electrodes were placed on the left and right mastoids, and the electrooculogram (EOG) generated from eye blinks and movements was recorded from facial electrodes: two approximately one cm above and below the left eye, one approximately one cm to the left of the left eye and one approximately one cm to the right of the right eye. The ground electrode during acquisition was formed by the Common Mode Sense and the Driven Right Leg electrodes. Electrode offsets were between +/− 20 mV. The data were digitized at 24-bit resolution with a LSB value of 31.25nV and a sampling rate of 1024 Hz, using a low-pass fifth order sinc filter with -3dB cutoff points at 208 Hz. Off-line analysis was performed using Brain Vision Analyzer software (Brain Products). Data were converted to a linked mastoid reference, band-pass filtered with cutoffs of 0.1 and 30 Hz, segmented for each trial 200 ms before feedback onset and continuing for 1000 ms after onset. The EEG was corrected for eye blinks (Gratton, Coles and Donchin, 1983). Artifact rejection was completed using semi-automated procedures and the following criteria: a voltage step of more than 50 μV between sample points, a voltage difference of 300 μV within a trial, and a voltage difference of less than .50 μV within 100 ms intervals. Visual inspection was used to remove additional artifacts. On average, 28.69 (SD=2.03) loss and 28.95 (SD=1.63) gain trials remained after artifact rejection. Data were baseline corrected using the 200 ms interval prior to feedback. ERPs were averaged across gain and loss trials, and the FN was scored as the mean amplitude 275-375 ms following feedback at a pooling of Fz, FCz and Cz. For each feedback type, amplitudes across these electrodes sites were high intercorrelated, rs>.74, p<.001. The selection of sites was based on visual inspection of the scalp distribution of the loss minus gain difference (Figure 1), as well as previous FN research which examined the FN at a pooling of Fz and FCz (e.g., Bress, Foti, Kotov, Klein, & Hajcak, 2013; Foti, Kotov et al., 2011) or across Fz, FCz, and Cz (e.g., Santesso et al., 2008; Santesso, Dzyundzyak, & Segalowitz, 2011). Analyses focused on the loss minus gain difference score (ΔFN) in order to isolate variation in the waveform attributed to processing of outcome valence (Luck, 2005); more negative values for the difference score indicate greater differentiation in the ERP between gains and losses and greater reactivity to valence. Analyses were also computed to evaluate effects on loss or gain trials individually.

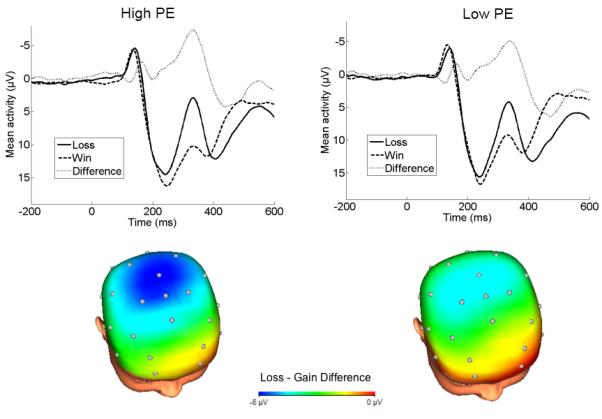

Figure 1.

ERPs (negative up) at Fz/FCz/Cz following feedback and scalp distributions depicting the loss minus gain difference 275-375 ms after feedback for children high and low in PE on the Lab-TAB at age 3. Note: A median split of PE was used for illustrative purposes. Analyses used continuous measures of temperament.

Results

Bivariate correlations between variables are presented in Table 1. On the Lab-TAB, older children showed higher PE and lower BI. Age at the time of the EEG assessment was positively related to loss FN. Males exhibited lower BI on the Lab-TAB and reported lower AFARS PA at age 9. Males had more negative ΔFN scores and a more positive FN on gain trials. In addition, Lab-TAB PE was negatively correlated with ΔFN, and BI was positively correlated with ΔFN. Lab-TAB NE was positively correlated with the FN on loss trials only.

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were computed with ΔFN, FN on loss trials only and FN on gain trials only as the criterion variables. Demographic variables, including sex, age at time 1 (T1), and age at time 2 (T2), were entered into step 1, followed by observed temperament from the Lab-TAB at the age 3 assessment (i.e., PE, NE, and BI) in step 2, and self-reported temperament from the AFARS at the age 9 assessment (i.e., PA, NA) in step 3. Entry betas for each predictor and ΔR2 and F values for each step are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses Predicting Age 9 Feedback Negativity from Observational and Self-Report Measures of Temperament Across Development.

| ΔFN | Loss FN | Gain FN | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Predictor | Δ R2 | Δ F | β | Δ R2 | Δ F | β | Δ R2 | Δ F | β |

| Step 1 – Demographics | .04 | 5.04** | .02 | 2.10 | .03* | 3.40** | |||

| Sex | −.18*** | −.01 | .14* | ||||||

| T1 age | −.08 | −.08 | −.01 | ||||||

| T2 age | .04 | .13* | .09 | ||||||

| Step 2 – Age 3 Lab-TAB | .02 | 2.08a | .02 | 2.40 | .01 | 1.19 | |||

| PE | −.11* | −.06 | .03 | ||||||

| NE | .05 | .14* | .10 | ||||||

| BI | .02 | −.02 | −.04 | ||||||

| Step 3 – Age 9 AFARS | .02 | 2.95* | .00 | .15 | .01 | 1.47 | |||

| PA | −.12* | −.02 | .08 | ||||||

| NA | .00 | −.02 | −.02 | ||||||

| Total Model | .07 | 3.50* | .04 | 1.72 | .04 | 2.10 | |||

p< .001;

p <.01;

p ≤ .05

p=.10; when NE and BI were removed from the model, ΔF for step 2 was significant, F(1, 376)=5.07, p=.03

In the ΔFN model, sex significantly predicted ΔFN, with males showing a larger (i.e., more negative) FN, t(380)=−3.58, p<.001. In addition, Lab-TAB PE at age 3 significantly predicted ΔFN at age 9, t(380)=−2.09, p=.04, such that higher PE was associated with greater differentiation between losses and gains (Figure 1). Observed NE and BI at age 3 did not significantly predict ΔFN (ps>.42).2 Additionally, AFARS PA at age 9, t(380)=−2.43, p=.02, but not AFARS NA (p>.97) significantly predicted ΔFN3. The effect of Lab-TAB PE remained significant after AFARS PA was entered into the model, β=−.11, t(380)=−2.13, p<.03. The entire model accounted for 7% of the variance in ΔFN (adjusted R2=.05).

In the loss FN model, children who were older at the EEG assessment showed less of a negativity to losses, t(380)=2.35, p=02. In addition, a significant effect of Lab-TAB NE was observed, t(380)=2.40, p=.02, with greater NE related to a less negative FN on loss trials only. Lab-TAB PE and AFARS PA did not significantly predict the FN on loss trials only, and the F values for each step and the overall model were not significant. In the gain FN model, the effect of sex was significant, t(380)=−2.69, p=.01, with males showing an enhanced positivity on gain trials compared to females. No other effects reached significance.4

Discussion

The current study evaluated whether early temperamental emotionality predicts children’s electrocortical responses to rewards and losses in later childhood. Results indicated that observed PE in preschool prospectively predicted the FN in late childhood. In addition, child self-reports of PA were concurrently related to the FN. Thus, across time and measurement approaches, children higher in PE/PA showed enhanced neural reactivity to rewards compared to losses, though the magnitudes of the effects were small.

Approach system-related temperament traits have previously been linked to resting EEG asymmetries (e.g., Sutton & Davidson, 1997) and neural processing of rewards as measured by fMRI (Cohen, et al., 2005; Forbes et al., 2010; Simon, et al., 2010); however, to our knowledge, this is the first study to use a longitudinal design to evaluate neural correlates of PE in children. The results demonstrate that individual differences in approach system-related temperament traits in early childhood predict neural reactivity to reward in late childhood, despite enormous developmental changes in both biological and socioemotional systems across this period (Giedd & Rapoport, 2010; Monk, 2008). These findings also support the validity of the FN as an index of some of the neural processes associated with PE and the approach system that may be useful in exploring a number of domains of developmental research.

Though the association between PE/PA and the FN was consistent across measures, the effect sizes for each predictor were quite small. Associations between neurophysiological and behavioral measures are typically small in magnitude owing to the substantial difference in methods (e.g., Patrick et al., 2013), and effect sizes are often smaller in larger samples compared to smaller studies, presumably because of type 1 errors and the “file drawer” problem (Contopoulos-Ioannidis et al., 2005; Ioannidis, Trikalinos, Ntzani, & Contopoulos-Ioannidis, 2003). In addition, the small associations in the current study are not surprising given the high variability characteristic of young children, the amount of time between assessments (two-thirds of the children’s lives), evidence that temperament is less stable in childhood compared to adolescence and adulthood (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000), and the fact that both temperament and FN were measured in single assessments, making it impossible to tease apart trait from state influences. Nonetheless, the effects indicate that individual differences in PE account for a small but significant proportion of the variance in the FN, and additional research is needed to examine other variables that moderate the associations between PE and neural reactivity to reward across development.

Interestingly, observational PE at age 3 and self-reported PA at age 9 were not related to each other but both had unique and comparable effects on the FN. The lack of a correlation between the measures is consistent with a large literature documenting low associations between laboratory and questionnaire measures of child temperament (Mangelsdorf et al., 2000), and may be attributed to the difference in methods and the large period of time between assessments. In addition, while Lab-TAB PE measures the expression of positive emotions within a structured, laboratory setting, AFARS PA measures the experience of positive emotions across a range of settings. Though these measures were not correlated, they each showed small associations with neural reactivity to reward and loss.

We also evaluated the effect of NE and BI on the FN in late childhood. Unlike PE, observed NE in early childhood did not predict the FN difference score in late childhood, though greater observed NE predicted a blunted FN (i.e., less negative) on loss trials only. This effect must be interpreted cautiously, as it was not apparent for the difference score measure and was not replicated cross-sectionally with child self-report. Nonetheless, this finding is consistent with recent evidence for a reduced FN among adults high in behavioral inhibition system sensitivity (Lange et al., 2012). As the FN is also modulated by violations in expectation (e.g., Hajcak, Holroyd, & Simons, 2007), it is possible that children who display higher NE expect more negative outcomes, which leads to a blunted FN to monetary losses.

In addition, we did not find an effect of BI on the FN when controlling for PE. Previous fMRI research has found that high BI is associated with increased striatal activation to cues indicating the possibility of a negative or positive outcome (Bar-Haim et al., 2009; Guyer et al., 2006). Thus, BI may be uniquely associated with reward reactivity when there is the potential to win or lose depending on the response, which is consistent with the conceptualization of the behavioral inhibition system as regulating behavior in response to a conflict between competing goals (Gray & McNaughton, 1982). To our knowledge, only one previous study has examined BI and neural reactivity to outcomes and found that high BI was associated with increased striatal activation to negative feedback (Helfinstein et al., 2011). The current study is among the first to examine multiple temperament constructs in a single study and it is possible that variability in PE may influence the results of previous studies exploring links between NE, BI, and reward-related neural activity.

Lastly, males showed greater electrocortical reactivity to monetary outcomes than females, and the effect of sex on the FN was larger than the effect of either PE measure. The association between the FN and sex is consistent with questionnaire studies of adults indicating that males report greater reward sensitivity than females (Li, Huang, Lin, & Sun, 2007; Torrubia, Avila, Moltó, & Caseras, 2001). Our findings suggest that this early-emerging gender difference is also observable on the neural level, and raise the importance of examining and controlling for sex when evaluating individual differences in reward sensitivity.

The results of the current study indicate that reward-related neural activity in late childhood is prospectively predicted by laboratory observations of temperamental PE in early childhood and concurrently associated with child self-reported PA. These findings contribute to understanding the neural processes associated with PE across development and suggest that the FN may be a useful measure of individual differences in approach-related system functioning.

Highlights.

Examined child temperament and the feedback negativity (FN) to monetary reward/loss

Greater observed PE at age 3 modestly predicted an enhanced FN at age 9

Greater self-reported PE at age 9 was independently related to the FN

Negative emotionality and behavioral inhibition did not consistently predict the FN

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grants RO1 MH069942 to Daniel N. Klein, RO3 MH094518 to Greg Hajcak Proudfit, and F31 MH09530701 to Autumn Kujawa.

Footnotes

The 32-channel BioSemi system includes the following electrodes: FP1, AF3, F7, F3, FC1, FC5, T7, C3, CP1, CP5, P7, P3, Pz, PO3, O1, Oz, O2, PO4, P4, P8, CP6, CP2, C4, T8, FC6, FC2, F4, F8, AF4, FP2, Fz, Cz

To evaluate whether multicollinearity may contribute to the lack of effects for BI and NE on ΔFN, we also computed two separate models with BI and PE in one and NE and PE in the other. The effect of PE remained significant in both models, but BI and NE did not significantly predict ΔFN in either model (ps>.29).

In order to evaluate whether effects of gender moderate the association between Lab-TAB PE or AFARS PA and the FN, we repeated the model with the addition of the gender X PE and gender X PA interactions in Step 4. The interactions were not significant (ps>.70). As age at the initial temperament assessment was significantly related to observed PE, we also computed a model with the addition of the T1 age X PE interaction in Step 4. The interaction was not significant (p>.12).

We also calculated 3 additional models with ΔFN at Fz, FCz, and Cz as the criterion variables. The effects of AFARS PA on the FN at Fz and the effect of Lab-TAB PE on the FN at Cz did not quite reach significance (p=.08 and p=.06, respectively), but no other changes in the results were observed.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bar-Haim Y, Fox NA, Benson B, Guyer AE, Williams A, Nelson EE, Ernst M. Neural correlates of reward processing in adolescents with a history of inhibited temperament. Psychological Science. 2009;20(8):1009–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02401.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Foti D, Kotov R, Klein DN, Hajcak G. Blunted neural response to rewards prospectively predicts depression in adolescent girls. Psychophysiology. 2013;50(1):74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01485.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Hajcak G. Self-report and behavioral measures of reward sensitivity predict the feedback negativity. Psychophysiology. 2013;50(7):610–616. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12053. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson JM, Foti D, Mujica-Parodi LR, Harmon-Jones E, Hajcak G. Ventral striatal and medial prefrontal BOLD activation is correlated with reward-related electrocortical activity: A combined ERP and fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2011;57(4):1608–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.037. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Moffitt C, Yim L, Umemoto LA. Assessment of tripartite factors of emotion in children and adolescents I: Structural validity and normative data of an affect and arousal scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2000;22(2):141–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1007584423617. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Temperament: A new paradigm for trait psychology. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality. 2nd ed Guilford Press; New York: 1999. pp. 399–423. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MX, Young J, Baek J-M, Kessler C, Ranganath C. Individual differences in extraversion and dopamine genetics predict neural reward responses. Cognitive Brain Research. 2005;25(3):851–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.09.018. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Gilbody SM, Trikalinos TA, Churchill R, Wahlbeck K, loannidis JPA. Comparison of large versus smaller randomized trials for mental health-related interventions. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):578–584. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.578. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daleiden E, Chorpita BF, Lu W. Assessment of tripartite factors of emotion in children and adolescents II: Concurrent validity of the affect and arousal scales for children. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2000;22(2):161–182. doi: 10.1023/A:1007536507687. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Emotion and affective style: Hemispheric substrates. Psychological Science. 1992;3(1):39–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1992.tb00254.x. [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Collins PF. Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1999;22(03):491–517. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Iacono WG. Neurobehavioral aspects of affective disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 1989;40(1):457–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.002325. doi: doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon DG, Rosso IM, Pechtel P, Killgore WDS, Rauch SL, Pizzagalli DA. Peril and pleasure: An RDOC-inspired examination of threat responses and reward processing in anxiety and depression. Depression and Anxiety. 2013 doi: 10.1002/da.22202. n/a-n/a. doi: 10.1002/da.22202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning JP, Hajcak G. Error-related negativities elicited by monetary loss and cues that predict loss. NeuroReport. 2007;18(17):1875–1878. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f0d50b. doi: 1810.1097/WNR.1870b1013e3282f1870d1850b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin CE, Hayden EP, Klein DN, Olino TM. Stability of laboratory assessed temperament traits from ages 3 to 7. Emotion. 2007;7:388–399. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.388. doi: doi:10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin CE, Klein DN, Hayden EP, Buckley ME, Moerk KC. Temperamental emotionality in preschoolers and parental mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(1):28–37. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.28. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.114.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson MW, Olino TM, Durbin CE, Goldsmith HH, Klein DN. The structure of temperament in preschoolers: A two-stage factor analytic approach. Emotion. 2012;12(1):44–57. doi: 10.1037/a0025023. doi: 10.1037/a0025023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Ryan ND, Phillips ML, Manuck SB, Worthman CM, Moyles DL, Dahl RE. Healthy adolescents’ neural response to reward: Associations with puberty, positive affect, and depressive symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(2):162–172. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201002000-00010. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201002000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Kotov R, Klein D, Hajcak G. Abnormal neural sensitivity to monetary gains versus losses among adolescents at risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(7):913–924. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9503-9. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Weinberg A, Dien J, Hajcak G. Event-related potential activity in the basal ganglia differentiates rewards from nonrewards: Temporospatial principal components analysis and source localization of the feedback negativity. Human Brain Mapping. 2011;32(12):2207–2216. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21182. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC. The three arousal model: Implications of Gray’s two-factor learning theory for heart rate, electrodermal activity, and psychopathy. Psychophysiology. 1980;17(2):87–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1980.tb00117.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1980.tb00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, Ghera MM. Behavioral inhibition: Linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:235–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ, Willoughby AR. The medial frontal cortex and the rapid processing of monetary gains and losses. Science. 2002;295(5563):2279–2282. doi: 10.1126/science.1066893. doi: 10.1126/science.1066893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Rapoport JL. Structural MRI of pediatric brain development: What have we learned and where are we going? Neuron. 2010;67(5):728–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.040. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Reilly J, Lemery K, Longley S, Prescott A. Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery: Preschool Version. 1995. Unpublished manuscript.

- Gratton G, Coles MG, Donchin E. A new method for off-line removal of ocular artifact. Electroencephalography & Clinical Neurophysiology. 1983;55(4):468–484. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90135-9. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, McNaughton N. The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Framework for a taxonomy of psychiatric disorder. In: van Goozen SHM, Van de Poll NE, Sergeant JA, editors. Emotions: Essays on emotion theory. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; Hillsdale, NJ England: 1994. pp. 29–59. [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs FE. Procedures for detecting outlying observations in samples. Technometrics. 1969;11(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, Nelson EE, Perez-Edgar K, Hardin MG, Roberson-Nay R, Monk CS, Ernst M. Striatal functional alteration in adolescents characterized by early childhood behavioral inhibition. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(24):6399–6405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0666-06.2006. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0666-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Moser JS, Holroyd CB, Simons RF. The feedback-related negativity reflects the binary evaluation of good versus bad outcomes. Biological Psychology. 2006;71(2):148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.04.001. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Moser JS, Holroyd CB, Simons RF. It’s worse than you thought: The feedback negativity and violations of reward prediction in gambling tasks. Psychophysiology. 2007;44(6):905–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00567.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden EP, Klein DN, Durbin CE. Parent reports and laboratory assessments of child temperament: A comparison of their associations with risk for depression and externalizing disorders. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2005;27(2):89–100. doi: 10.1007/s10862-005-5383-z. [Google Scholar]

- Helfinstein SM, Benson B, Perez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, Detloff A, Pine DS, Ernst M. Striatal responses to negative monetary outcomes differ between temperamentally inhibited and non-inhibited adolescents. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(3):479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.015. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd CB, Pakzad-Vaezi KL, Krigolson OE. The feedback correct-related positivity: Sensitivity of the event-related brain potential to unexpected positive feedback. Psychophysiology. 2008;45(5):688–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00668.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis JPA, Trikalinos TA, Ntzani EE, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG. Genetic associations in large versus small studies: An empirical assessment. Lancet. 2003;361(9357):567. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12516-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J. Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Development. 1984;55(6):2212–2225. doi: 10.2307/1129793. [Google Scholar]

- Kennis M, Rademaker AR, Geuze E. Neural correlates of personality: An integrative review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2013;37:73–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.10.012. doi: doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex. Psychological Review. 1990;97(3):377–395. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.3.377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange S, Leue A, Beauducel A. Behavioral approach and reward processing: Results on feedback-related negativity and P3 component. Biological Psychology. 2012;89(2):416–425. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.12.004. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.-s. R., Huang C-Y, Lin W.-y., Sun C-WV. Gender differences in punishment and reward sensitivity in a sample of Taiwanese college students. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(3):475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.12.016. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RE, Diener E, Grob A, Suh EM, Shao L. Cross-cultural evidence for the fundamental features of extraversion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79(3):452–468. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.3.452. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ. An introduction to the event-related potential technique. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf SC, Schoppe SJ, Buur H. The meaning of parental reports: A contextual approach to the study of temperament and behavior problems in childhood. In: Molfese VJ, Molfese DL, editors. Temperament and personality development across the lifespan. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 2000. pp. 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS. The development of emotion-related neural circuitry in health and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20(Special Issue 04):1231–1250. doi: 10.1017/S095457940800059X. doi: doi:10.1017/S095457940800059X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott JM, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA. A history of childhood behavioral inhibition and enhanced response monitoring in adolescence are linked to clinical anxiety. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65(5):445–448. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.043. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein D, Durbin CE, Hayden EP, Buckley ME. The structure of extraversion in preschool aged children. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39:481–492. [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Dyson MW, Rose SA, Durbin CE. Temperamental emotionality in preschool-aged children and depressive disorders in parents: Associations in a large community sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(3):468–478. doi: 10.1037/a0020112. doi: 10.1037/a0020112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Venables NC, Yancey JR, Hicks BM, Nelson LD, Kramer MD. A construct-network approach to bridging diagnostic and physiological domains: Application to assessment of externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122(3):902. doi: 10.1037/a0032807. doi: 10.1037/a0032807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer M, Goldsmith HH, Davidson RJ, Rickman M. Continuity and change in inhibited and uninhibited children. Child Development. 2002;73(5):1474–1485. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polak-Toste CP, Gunnar MR. Temperamental exuberance: Correlates and consequences. In: Mashall P, Fox NA, editors. The development of social engagement: Neurobiological perspectives. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP. Positive emotionality. In: Zentner M, Shiner RL, editors. Handbook of temperament. Guillford Press; New York: 2012. pp. 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, DelVecchio WF. The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(1):3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santesso DL, Bogdan R, Birk JL, Goetz EL, Holmes AJ, Pizzagalli DA. Neural responses to negative feedback are related to negative emotionality in healthy adults. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 2012;7(7):794–803. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr054. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santesso DL, Dzyundzyak A, Segalowitz SJ. Age, sex and individual differences in punishment sensitivity: Factors influencing the feedback related negativity. Psychophysiology. 2011;48(11):1481–1488. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01229.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santesso DL, Steele KT, Bogdan R, Holmes AJ, Deveney CM, Meites TM, Pizzagalli DA. Enhanced negative feedback responses in remitted depression. NeuroReport. 2008;19(10):1045. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283036e73. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283036e73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JJ, Walther S, Fiebach CJ, Friederich H-C, Stippich C, Weisbrod M, Kaiser S. Neural reward processing is modulated by approach- and avoidance-related personality traits. Neuroimage. 2010;49(2):1868–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smillie LD, Cooper AJ, Pickering AD. Individual differences in reward–prediction–error: extraversion and feedback-related negativity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2011;6(5):646–652. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq078. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smillie LD. Extraversion and reward processing. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22(3):167–172. doi: 10.1177/0963721412474460. doi: 10.1177/0963721412470133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton SK, Davidson RJ. Prefrontal brain asymmetry: A biological substrate of the behavioral approach and inhibition systems. Psychological Science. 1997;8(3):204–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00413.x. [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Davidson RJ, Wheeler RE, Doss RC. Individual differences in anterior brain asymmetry and fundamental dimensions of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62(4):676–687. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.62.4.676. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.62.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrubia R, Avila C, Moltó J, Caseras X. The Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray’s anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31(6):837–862. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211(4481):453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-2391-4_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of risk and uncertainty. 1992;5(4):297–323. doi: 10.1007/BF00122574. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Wiese D, Vaidya J, Tellegen A. The two general activation systems of affect: Structural findings, evolutionary considerations, and psychobiological evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:820–838. [Google Scholar]

- Wilt J, Revelle W. Extraversion. In: Leary M, Hoyle R, editors. Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. Guilford Press; New York: 2009. pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]