Abstract

Background and Aims.

There are few long-term studies of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in living liver donors. This study aimed to characterize donor HRQOL in the Adult to Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Study (A2ALL) up to 11 years post-donation.

Methods.

Between 2004-2013, HRQOL was assessed at evaluation, and 3 months and yearly post-donation in prevalent liver donors using the Short Form survey (SF-36), which provides a physical (PCS) and a mental component summary (MCS).

Results.

Of the 458 donors enrolled in A2ALL, 374 (82%) had SF-36 data. Mean age at evaluation was 38 (range 18-63), 47% were male, 93% white, and 43% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. MCS and PCS means were above the US population at all time points. However, at every time point there were some donors who reported poor scores (>1/2 standard deviation below the age and sex adjusted mean) (PCS: 5.3%-26.8%, MCS: 10.0%-25.0%). Predictors of poor PCS and MCS scores included recipient death within the two years prior to the survey and education less than a bachelor’s degree; poor PCS scores were also predicted by time since donation, Hispanic ethnicity, and at the 3-month post-donation time point.

Conclusions.

In summary, most living donors maintain above average HRQOL up to 11 years prospectively supporting the notion that living donation does not negatively affect HRQOL. However, targeted support for donors at risk for poor HRQOL may improve overall HRQOL outcomes for living liver donors.

Keywords: Patient Reported Outcomes, Quality of Life, Living Donor Liver Transplantation, Living Liver Donors, Adult to Adult Living Donor Liver Transplant Cohort Study (A2ALL)

Introduction

Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is a life-saving procedure for recipients with end-stage liver disease or unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma and helps mitigate the scarcity of deceased donor organs [1]. The nine center Adult to Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation (A2ALL) Study has demonstrated that patient and graft survival for LDLT recipients are excellent and in some cases supersede outcomes from deceased donor liver transplantation [2-5]. However, LDLT involves a healthy donor who derives no medical benefit from the surgery, while bearing a significant risk of morbidity and mortality [6, 7]. In fact, the A2ALL cohort showed that 40% of donors experience a complication, most of them minor (98% categorized as Clavien grade I or II); 95% resolve within the first postoperative year [8].

While potential LDLT donors can be informed about their short-term and long-term risks for morbidity and mortality based on longitudinal, multi-center clinical data, there is relatively little information available on the long-term effect of donation on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) outcomes [9, 10]. HRQOL is a multi-dimensional concept that refers to an individual’s physical, emotional, and social well-being as impacted by a medical condition or its treatment [11]. Published reports of living liver donors’ HRQOL have typically been single-center, cross-sectional samples with short-term follow-up periods of usually one year or less [9, 10, 12-32]. There remains a need for more information on the long-term effect of living liver donation on donor HRQOL to have a more comprehensive understanding of LDLT outcomes and to enhance informed consent for potential donors.

The most meaningful way to assess donor HRQOL is to ask patients directly. One strategy to accomplishing this is using standardized patient-reported outcomes measures. The Short-Form health survey (SF-36) is one such measure [33, 34] with normative data from the general population that has been used to assess HRQOL across many different patient populations, including LDLT [10]. While disease-specific instruments have been used to characterize the HRQOL of specific populations, such as the Liver Disease Quality of Life survey for use in patients with chronic liver disease [35, 36], to date there is no specific instrument that captures the multiple HRQOL domains of importance for LDLT donors.

In the A2ALL study, living liver donor HRQOL was assessed longitudinally using the SF-36. We provide descriptive data for short- and long-term HRQOL for living liver donors captured in the multi-center A2ALL cohort. We hypothesized that there are short-term effects, but that long-term HRQOL would not be negatively affected by living liver donation.

Methods

Procedure

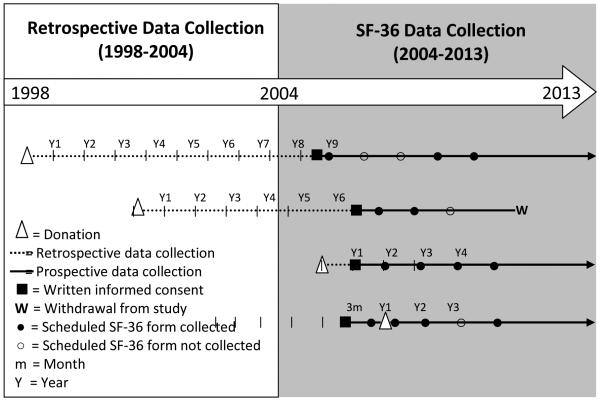

Data for this analysis were collected from living liver donors enrolled in the A2ALL study who donated between 1998 and 2010. Clinical, laboratory, hospitalization, complication and HRQOL data were collected between 2004 and 2013. The nine participating centers were: Northwestern University; Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons; University of California, San Francisco; University of North Carolina; University of California, Los Angeles; Medical College of Virginia Hospitals; University of Virginia, Charlottesville; University of Colorado; and University of Pennsylvania. Data collection ceased at University of North Carolina; University of California, Los Angeles, and University of Virginia, Charlottesville after August 31, 2010 while the remaining six centers continued data collection through 2013. HRQOL surveys, which included the SF-36, were administered to donors enrolled in A2ALL at pre-donation evaluation, 3 months post-donation, 1 year post-donation, and every year thereafter up to a maximum of 8 years. Some donors enrolled in A2ALL after their donation and were followed for a maximum of 11 years; therefore, the cohort includes those with and without HRQOL assessments prior to donation (Figure 1). To maximize response rates, the SF-36 survey was administered to A2ALL donors in several formats (on tablet computers, via paper forms by mail or at the clinical center, or by web-based forms) through 2010. From 2011-2013, HRQOL data were collected centrally via telephone by trained interviewers at Northwestern University. To determine if administration mode affected HRQOL scores, we tested it as a covariate in the models. We found no significant effects, as all p-values were greater than 0.05 (the range of p-values for modes of administration were 0.24-0.60 and 0.36-0.88 for MCS and PCS models, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Study timeline and examples of donor enrollment pre-donation versus post-donation

Measures and Outcomes

The SF-36 form (version 2) is a brief survey of health status consisting of 36 questions, with eight subscales (physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health). In addition, two summary measures, the mental component summary (MCS) and physical component summary (PCS) scores were calculated. The MCS and PCS scores calculated from the SF-36 survey are standardized on a scale from 0 to 100; the general population average is 50 with a standard deviation (SD) of 10. Most donors were above the national HRQOL average both pre- and post-donation. However, the donors who did report poor HRQOL were of interest in this analysis. Poor HRQOL was defined as a score that was more than 0.5 SD below the normative age- and sex-adjusted mean at the time of donor assessment. Half a SD is a typical minimally important difference in quality of life instruments [37].

For each donor, relevant recipient outcomes, such as re-transplantation and death, were obtained from A2ALL data, supplemented by data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) under a data use agreement. SRTR death records were only available through the end of 2012. The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the US, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), and has been described elsewhere. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards and Privacy Boards of the University of Michigan Data Coordinating Center and each of the nine participating transplant centers. The IRB approval number is HUM00045813; the protocol number is 2002-0488. All subjects provided written informed consent to this study.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons of donor characteristics between those with and without SF-36 forms were performed using chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate.

We used a repeated measures logistic regression to model the likelihood of donors having a low SF-36 composite score. These models used generalized estimating equations [38] with a compound symmetry covariance structure for repeated measures on the same subject over time. Covariates considered for inclusion in the models included donor demographics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, education), relationship to recipient (biological, non-biological, and spouse), medical information (body mass index [BMI], hypertension, clinically diagnosed depression, use of pain medications), and lifestyle data (current smoker, former smoker, or nonsmoker). Variables measured over time since donation included number of complications prior to the time of survey, recipient outcome variables (graft failure —defined as death or re-transplant — and/or death prior to the corresponding SF-36 survey), and time since donation as a continuous variable. After initial analysis we observed that mean HRQOL was lower at 3 months, deviating from the otherwise linear trajectory. Therefore, we also included an indicator variable for the 3-month time point to capture this deviation.

For donors with SF-36 information pre- and post-donation, logistic regression models were also used to test pre-donation PCS and MCS scores as predictors of post-donation HRQOL. Additionally, t-tests were used to assess changes in PCS and MCS scores pre-donation vs. scores 1 year post-donation and beyond.

Forms that were missing more than 50% of items of any SF-36 subscale were excluded from the analysis (N=16). Of the remaining 1,116 SF-36 forms, 1,086 (97%) were filled out completely. Multiple imputation using linear regression with bounds (for each ordinal item, lowest value – 0.5 to highest value + 0.5) was used to calculate the missing item responses for the 30 (3%) forms with some incomplete data. Out of 36 items, 22 forms were missing one item, six were missing two items, and two were missing three or four items. The complete and imputed responses to the 36 questions on the survey were used to calculate the PCS and MCS scores. For the figures that include boxplots, only the first imputation was used. For the models, the standard method of combining results from five imputed data sets was used (SAS MIANALYZE procedure). All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) and IVEware version 0.2 (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI).

Results

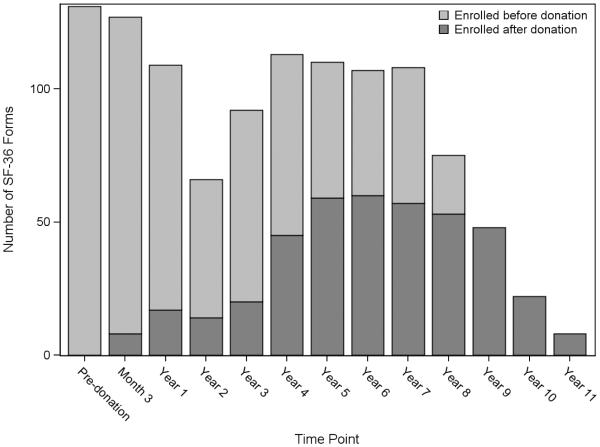

This study included HRQOL data from 374 donors, with an average of three forms per donor assessment ranging from pre-donation to 11 years post-donation. These 374 donors represent 82% of the total donor population enrolled in A2ALL at the nine centers (N=458). The mean age at evaluation for donation was 38.0 ± 10.2 (range 18.2 to 62.7) years, 47% were male, 93% white, 12% Hispanic, and BMI ranged from 16 to 42 (Table 1). Nearly half the donors (43%) had an educational level reflecting a bachelor’s degree or higher. Of the 374 donors, 354 (95%) had post-donation data. Two hundred and nineteen (59%) donors enrolled prior to donation. Of those donors, 131 (60%) had pre-donation HRQOL data and 111 (51%) had both pre- and post-donation HRQOL data (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of donors

| SF-36 Data (N=374) | No SF-36 Data (N=84) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N or Mean, SD | Percent or Range | N or Mean, SD | Percent or Range | |

| Race | ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Asian | 8 | 2.1 | 2 | 2.4 |

| Black/African American | 9 | 2.4 | 3 | 3.6 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 1.2 |

| White | 349 | 93.3 | 73 | 86.9 |

| More than One Race | 5 | 1.3 | 5 | 6.0 |

| Ethnicity § | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 46 | 12.3 | 18 | 21.4 |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 328 | 87.7 | 66 | 78.6 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 174 | 46.5 | 42 | 50.0 |

| Female | 200 | 53.5 | 42 | 50.0 |

| Age at evaluation for donation | 38.0, 10.2 | 18.2 – 62.7 | 36.6, 10.7 | 18.8 – 54.6 |

| BMI at evaluation for donation | 26.2, 4.0 | 16.4 – 42.4 | 26.6, 3.4 | 20.4 – 34.7 |

| Relationship to recipient | ||||

| Biological | 233 | 62.3 | 56 | 66.7 |

| Non-biological | 97 | 25.9 | 19 | 22.6 |

| Spouse | 44 | 11.8 | 9 | 10.7 |

| Education attainment at evaluation for donation§ | ||||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 161 | 43.0 | 22 | 26.2 |

| Less than a bachelor’s degree | 177 | 47.3 | 51 | 60.7 |

| Missing | 36 | 9.6 | 11 | 13.1 |

| Current smoker | 37 | 9.9 | 13 | 15.5 |

| Previous smoker | 59 | 15.8 | 15 | 17.9 |

| History of depression | 29 | 7.8 | 2 | 2.4 |

| Systemic hypertension | 9 | 2.4 | 2 | 2.4 |

| Patient reports pain drug use | 70 | 18.7 | 12 | 14.3 |

| Non-prescription drug use | 66 | 17.6 | 10 | 11.9 |

| Prescription drug use | 7 | 1.9 | 2 | 2.4 |

| Complication occurred before study end point* | ||||

| Any grade | 159 | 42.5 | 36 | 42.9 |

| Grade 1 α | 57 | 15.2 | 11 | 13.1 |

| Grade 2 α | 95 | 25.4 | 23 | 27.4 |

| Grade 3 α | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.2 |

| SF-36 Data (N=374) | No SF-36 Data (N=84) | |||

| N or Mean, SD | Percent or Range | N or Mean, SD | Percent or Range | |

|

Complication occurred before last SF-36 time

period |

147 | 39.3 | -- | -- |

| Grade 1 α | 51 | 13.6 | -- | -- |

| Grade 2 α | 90 | 24.1 | -- | -- |

| Grade 3 α | 2 | 0.5 | -- | -- |

| Recipient graft failure before study end point* | 109 | 29.1 | 33 | 39.3 |

| Recipient graft failure before or during last donor SF-36 time period† |

105 | 28.1 | -- | -- |

| Recipient death before study end point* | 82 | 21.9 | 22 | 26.2 |

| Recipient death before or during last donor SF-36 time period† Enrolled in A2ALL study before donation § |

57 219 |

15.2 58.6 |

-- 30 |

-- 35.7 |

P-value < 0.05. Ethnicity (Chi-square test, p=0.03), education (Chi-square test, p=0.02), consented to A2ALL study before donation (Chi-square test, p=0.0001)

Complication grade not collected after August 31, 2010

Recipient graft failure/death occurred before the end of the A2ALL Cohort study

Recipient graft failure/death occurred before the donor’s last SF-36 form was completed

Fig. 2.

Number of SF-36 forms by time point (N=374 donors; N=1116 forms)

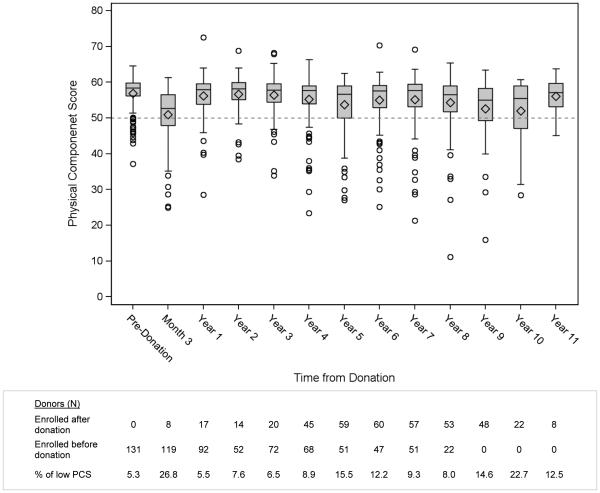

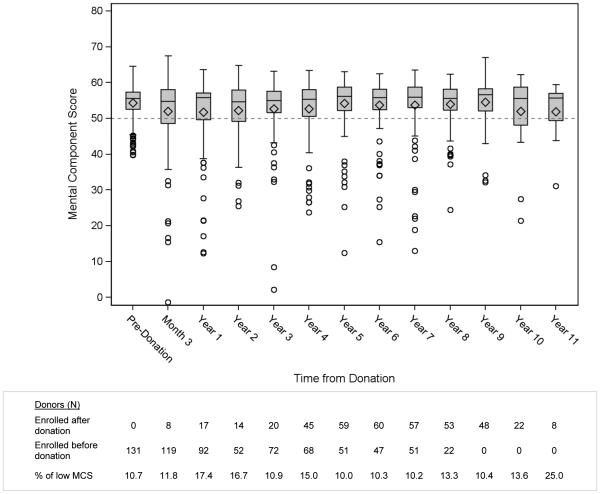

Figure 3 shows boxplot distributions of PCS at each time point. At each measured time point the average PCS score was higher than the population norm, ranging from 50.9-56.9. The pre-donation mean score was 56.9 ± 4.5 (range 37.2 – 64.5);5.3% of donors had a low PCS score, defined as more than half a SD below the mean, adjusted for age and sex. The PCS scores were the lowest at three months after donation, with 27% of donors reporting low values, but only 6% reported poor physical well-being at 1 year post-donation. The age- and sex-adjusted PCS scores appear to briefly stabilize after 1 year, with the percentage of low values increasing slightly at later time points. Figure 4 shows boxplot distributions of MCS at each time point. The average MCS scores were higher than the population mean, ranging from 51.7-54.5. The pre-donation MCS mean was 54.3 ± 5.3 (range 39.8 – 64.5). The percentage of low MCS scores (more than half a SD below the mean, adjusted for age and sex) at the 3-month time point did not increase as seen in the PCS scores. Similar boxplots for each subscale are given in the supplementary information (Figures S1-S8).

Fig. 3.

Physical Component Summary

Fig. 4.

Mental Component Summary

Predictors of poor PCS and MCS scores

A small proportion of donors reported poor PCS and MCS scores. The significant predictors of poor (>0.5 SD from age-/sex-adjusted normative values) PCS and MCS scores are reported in Table 2. Predictors of poor PCS included recipient death within two years prior to reporting HRQOL data (OR=2.1, p=0.05), the 3 month time point after donation compared to all other time points (OR=6.4, p<0.0001), Hispanic ethnicity (OR=2.5, p=0.01), education less than a bachelor’s degree (OR=1.9, p=0.02), and longer time since donation as a continuous variable (OR=1.1 per year, p=.001). Significant predictors of a poor MCS score (Table 2b) were recipient death within two years prior to reporting HRQOL data (OR=2.9, p=0.004) and education less than a bachelor’s degree (OR=1.8, p=0.02). For both MCS and PCS models, some donors may not have had their recipient’s death recorded if the recipient’s A2ALL follow-up ended prior to 2013 and could not be supplemented by SRTR death data, which ended in 2012. As a sensitivity analysis, the models were re-run after truncating follow-up at the end of 2012 and the recipient death variable results were almost identical (PCS: OR=2.4, p=0.03; MCS: OR=2.6, p=0.02).

Table 2a.

Predictors of PCS more than half a SD below the mean* (N=374 donors, N=1116 SF-36 forms)

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic/Latino (ref: not Hispanic/Latino) | 2.539 | 1.258 | 5.123 | 0.009 |

| Education: Bachelor's degree or higher (ref: less than a bachelor's degree or missing) |

0.531 | 0.308 | 0.915 | 0.023 |

| Recipient death within two years prior to corresponding SF-36 survey | 2.13 | 1.014 | 4.474 | 0.046 |

| Time period is 3 months post-donation | 6.382 | 3.599 | 11.315 | <0.0001 |

| Time since donation (years) | 1.138 | 1.053 | 1.23 | 0.001 |

Table 2b.

Predictors of MCS more than half a SD below the mean* (N=374 donors, N=1116 SF-36 forms)

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education: Bachelor's degree or higher (ref: less than a bachelor's degree or missing) |

0.563 | 0.346 | 0.915 | 0.02 |

| Recipient death within two years prior to corresponding SF-36 survey | 2.879 | 1.391 | 5.956 | 0.004 |

Paired Comparisons of Pre- and Post-donation Scores

In the pre- and post-donation comparison (N=111), low pre-donation MCS scores did not predict low post-donation MCS scores (p=0.33). Low pre-donation PCS scores slightly increased the likelihood of having a low post-donation PCS score (OR=1.1, p=0.04).

For donors with pre-donation and post-donation data 1 year or beyond (N=92), we tested for differences in MCS and PCS scores pre- and post-donation using each donor’s first and last annual post-donation time points. For MCS scores, no significant differences between pre- and post-donation scores were seen (pre-donation vs. first annual: p=0.27, vs. last annual: p=0.45). For PCS scores, consistent with the decreasing time trend seen in the previous section, significant decreases of approximately 1.7 score points were seen (pre-donation vs. first annual: p=0.03, vs. last annual: p=0.02).

Comparison to patients with no SF-36 data

Comparing donors with SF-36 data to those with no SF-36 data revealed few differences (Table 1). Among those with SF-36 data, a greater proportion were non-Hispanic/Latino (88%) and had a bachelor’s degree or higher (43%) compared to those without SF-36 data (79% non-Hispanic/Latino, 26% with bachelor’s degree or higher; p=0.03, p=0.02, respectively). Those with SF-36 data were more likely to have consented pre-donation (59% vs. 36%, p=0.0001). Other demographic characteristics, as well as the proportion of donors with recipient death or graft failure during the study, did not significantly differ.

Furthermore, among donors with some SF-36 data, only recipient death increased the likelihood of missing forms (OR=1.6, p=0.01) (Table S1), while other demographic factors did not predict missingness.

Discussion

This investigation by the nine-center A2ALL study demonstrates that living liver donors have greater mental and physical health, as reported by the SF-36, than the general population and that living donor hepatectomy does not negatively affect the long-term HRQOL of donors.

The unique contribution of this study is that it followed the HRQOL of living donors prospectively from multiple centers for up to 11 years. Donors from the A2ALL study generally maintained emotional and physical well-being (MCS and PCS) above the normative population throughout the study period. However, we observed an understandable decrement in physical well-being in the immediate post-operative period followed by a return to baseline levels. We did identify a small decline in PCS scores over time, which is most notable in later time points and can likely be attributed to the effects of aging, a phenomenon also observed in the general normative population [39]. In comparison, the donor emotional well-being remains stable on average, and above the population norm throughout the donation process and after.

Our results support published findings from single-center studies that have examined the effect of living donation up to one year prospectively and up to 50 months cross-sectionally [5, 10, 12, 16, 19, 22-24, 28, 30]. These studies reported that the baseline HRQOL of living donors is above the normative population. The A2LL cohort, which also has higher HRQOL at baseline for donors compared to the normative data, may have higher HRQOL because the donors are more educated and of higher socioeconomic status than the normative cohort. Previous studies also suggest that the physical well-being deteriorates after surgery but returns to baseline within 6-12 months, and that mental well-being does not significantly change during the donation from baseline [10]. Our multi-center study demonstrates that living liver donation does not negatively affect HRQOL prospectively up to 11 years post-donation. This is important information for transplant centers as they provide information to their potential living donors during their decision making process [2, 3, 40, 41].

Another contribution from this study is the identification of predictive factors for poor HRQOL after living donation. Despite the overall above average levels of HRQOL scores, the A2ALL cohort identified a subgroup of donors who reported low physical or mental well-being, which we defined as scores 0.5 SD or more below age- and sex-adjusted normative values. With further investigation of this subgroup a few unexpected findings were observed.

One interesting group was donors who reported low HRQOL prior to donation (Total N=18; low PCS: 7, low MCS: 14). While there were not many donors in this category, it suggests that there is some variability in scores even in this generally healthy population, which did not prevent them from being selected as living liver donors. Interestingly, donors who reported low MCS scores prior to liver donation were not more likely to have lower MCS scores after donation, but donors with lower PCS scores prior to donation were more likely to report low PCS scores after donation

Another group of donors experienced HRQOL well below normative levels after 3 months post-donation (Total N= 102, low PCS: 41, low MCS: 77). While this group represents less than a third of the donors, it does suggest that there are donors who may require heightened surveillance post-donation. The multivariable analysis demonstrated that recent recipient death predicted lower donor PCS and MCS scores. A recent study identified an intermittent dip in HRQOL for living kidney donors whose recipient died [42]. Similar to our findings, those recipients mostly recovered back to baseline. While this may be intuitive, it does highlight the possible benefit of offering these donors bereavement counseling or other supportive care. It is to be noted that despite the negative effect of recipient death on donor HRQOL, donors did not report “donation regret” even when recipient outcomes are poor. Neither low MCS nor PCS scores were predicted by postoperative complications. In other health care settings, such as orthopedics, poor mental disposition was linked with poor clinical outcomes [43]. In the A2ALL cohort, such an association was not found.

Furthermore, in the A2ALL cohort, lower educational attainment (less than a bachelor’s degree) was predictive of low PCS and MCS scores. While studies in living liver donors have been disparate about the role of education on the HRQOL of donors [9, 19], our findings are consistent with those of the recently published RELIEVE study [44], where higher education had a protective effect on HRQOL. This is consistent with other studies showing that communication, setting of expectations, and informed consent are less effective when they are directed at patients with low educational attainment, as clinicians may not be sensitive to differences in patient literacy and numeracy in their communications [45, 46]. Therefore, it may be beneficial to consider ways that transplant teams can provide pre-donation education that is more appropriate across the full range of socioeconomic backgrounds and health literacy levels [47]. Such efforts can lead to improvements in informed consent and shared decision making, which would likely have downstream impacts on clinical outcomes and HRQOL [48]. These efforts may also lead to greater equity in access to living donor transplantation for transplant candidates and potential donors who have lower educational attainment and socioeconomic status.[49]

Lastly, being Hispanic predicted poor PCS scores, but it did not predict poor MCS scores. In other clinical settings, it has been shown that the perception of physical well-being is culturally dependent and may suggest that Hispanic individuals perceive their physical well-being differently than other ethnic groups [50]. The setting of expectations prior to living donation might be important to guide the post-operative experience. Also, receiving more culturally appropriate and congruent care before and after donation may have a direct or indirect impact on their HRQOL [50, 51]. One possible solution, as has been done in a kidney transplant setting [52], is to provide education that addresses cultural barriers in Spanish, by Hispanic clinicians (e.g., surgeons, hepatologists, nurses), addressing specific cultural barriers (e.g., position of the Catholic Church, effect on fertility).

There were several limitations to this study. First, while frequently used in HRQOL studies, the SF-36 is a generic instrument that does not include open-ended questions and was not specifically designed to assess HRQOL issues specific to the donation process. Thus, there may have been areas or domains of well-being that are affected by donation but were not adequately captured by our assessments. Efforts are underway to develop living liver donor-specific HRQOL instruments, such as an instrument recently described by a Japanese group [53]. Such instruments may improve the comprehensive assessment of living donors. Also, A2ALL focuses on adult to adult living liver donation; our study did not include donation of adults to children. Finally, the data collection was incomplete; many donors did not have pre-donation HRQOL data due to the timing of their enrollment into A2ALL. Less than complete data capture occurred among enrolled donors for several reasons, including timing issues during clinic appointments, technical problems with computerized form administration, donors not returning mailed forms, and loss to follow-up. Generalizations of these findings are limited to living liver donor groups similar to those studied in this sample.

In summary, this investigation provides supportive data that HRQOL for living liver donors is generally good in the short-term and remains so in the long-term. Certain groups of donors, such as Hispanic donors, those with low educational attainment, and those whose recipients die, are at increased risk for poor perceived well-being and may benefit from additional or tailored support. This information will be valuable for counseling potential donors and for providing optimal care for those who proceed with donation.

Supplementary Material

DESCRIPTION OF SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supplementary Fig. 1. Physical Functioning Scores

Supplementary Fig. 2. Physical Role Limit Scores

Supplementary Fig. 3. Emotional Role Scores

Supplementary Fig. 4. Bodily Pain Scores

Supplementary Fig. 5. General Health Scores

Supplementary Fig. 6. Vitality Scores

Supplementary Fig. 7. Social Functioning Scores

Supplementary Fig. 8. Mental Health Scores

Acknowledgements

The data reported here have been supplied by Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation (MMRF) as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the U.S. Government.

This is publication number #25 of the Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study. This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases through cooperative agreements (grants U01-DK62444, U01-DK62467, U01-DK62483, U01-DK62484, U01-DK62494, U01-DK62496, U01-DK62498, U01-DK62505, U01-DK62531, and U01-DK62536). Additional support was provided by Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS).

Financial Support

This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases through cooperative agreements (grants U01-DK62444, U01-DK62467, U01-DK62483, U01-DK62484, U01-DK62494, U01-DK62496, U01-DK62498, U01-DK62505, U01-DK62531, and U01-DK62536). Additional support was provided by Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS).

Abbreviations

- A2ALL

Adult to Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study

- BMI

body mass index

- HRQOL

health-related quality of life

- LDLT

living donor liver transplantation

- MCS

mental component summary

- PCS

physical component summary

- SD

standard deviation

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests:

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the Journal of Hepatology.

This study was presented in part at the 61st annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Boston, MA, October 29 – November 2, 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: Transplant Data. Health Resources and Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg CL, et al. Improvement in survival associated with adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(6):1806–13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulik LM, et al. Outcomes of living and deceased donor liver transplant recipients with hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the A2ALL cohort. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(11):2997–3007. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terrault NA, et al. Outcomes in hepatitis C virus-infected recipients of living donor vs. deceased donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2007;13(1):122–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.20995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trotter JF, et al. Adult-to-adult transplantation of the right hepatic lobe from a living donor. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(14):1074–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marsh JW, et al. Complications of right lobe living donor liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2009;51(4):715–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surman OS. The ethics of partial-liver donation. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(14):1038. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200204043461402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abecassis MM, et al. Complications of living donor hepatic lobectomy--a comprehensive report. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(5):1208–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuBay DA, et al. Adult right-lobe living liver donors: quality of life, attitudes and predictors of donor outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(5):1169–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parikh ND, et al. Quality of life for donors after living donor liver transplantation: a review of the literature. Liver Transpl. 2010;16(12):1352–8. doi: 10.1002/lt.22181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) 11/1/2012 3/13/2013]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/.

- 12.Basaran O, et al. Donor safety and quality of life after left hepatic lobe donation in living-donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(7):2768–9. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.09.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beavers KL, et al. The living donor experience: donor health assessment and outcomes after living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2001;7(11):943–7. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.28443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan SC, et al. Donor quality of life before and after adult-to-adult right liver live donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(10):1529–36. doi: 10.1002/lt.20897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erim Y, Senf W, Heitfeld M. Psychosocial impact of living donation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(3):911–2. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feltrin A, et al. Experience of donation and quality of life in living kidney and liver donors. Transpl Int. 2008;21(5):466–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu HT, et al. Impact of liver donation on quality of life and physical and psychological distress. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(7):2102–5. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humar A, et al. A comparison of surgical outcomes and quality of life surveys in right lobe vs. left lateral segment liver donors. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(4):805–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00767.x. Pt 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karliova M, et al. Living-related liver transplantation from the view of the donor: a 1-year follow-up survey. Transplantation. 2002;73(11):1799–804. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200206150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim-Schluger L, et al. Quality of life after lobectomy for adult liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73(10):1593–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200205270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kousoulas L, et al. Living-donor liver transplantation: impact on donor's health-related quality of life. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(10):3584–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kusakabe T, et al. Feelings of living donors about adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2008;31(4):263–72. doi: 10.1097/01.SGA.0000334032.48629.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyagi S, et al. Risks of donation and quality of donors' life after living donor liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2005;18(1):47–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2004.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parolin MB, et al. Donor quality of life after living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2004;36(4):912–3. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.03.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pascher A, et al. Donor evaluation, donor risks, donor outcome, and donor quality of life in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8(9):829–37. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.34896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sevmis S, et al. Right hepatic lobe donation: impact on donor quality of life. Transplant Proc. 2007;39(4):826–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trotter JF, et al. Right hepatic lobe donation for living donor liver transplantation: impact on donor quality of life. Liver Transpl. 2001;7(6):485–93. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.24646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verbesey JE, et al. Living donor adult liver transplantation: a longitudinal study of the donor's quality of life. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(11):2770–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walter M, et al. Psychosocial outcome of living donors after living donor liver transplantation: a pilot study. Clin Transplant. 2002;16(5):339–44. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2002.02002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walter M, et al. Quality of life of living donors before and after living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(8):2961–3. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walter M, et al. [Living donor liver transplantation from the perspective of the donor: results of a psychosomatic investigation] Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2005;51(4):331–45. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2005.51.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamanouchi K, et al. Changes in quality of life after hepatectomy and living donor liver transplantation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59(117):1569–72. doi: 10.5754/hge10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brazier JE, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305(6846):160–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gotardo DR, et al. Liver transplantation and quality of life: relevance of a specific liver disease questionnaire. Liver Int. 2008;28(1):99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jay CL, et al. A review of quality of life instruments used in liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2009;51(5):949–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41(5):582–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal Data Analysis Using Generalized Linear Models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hopman WM, et al. The natural progression of health-related quality of life: results of a five-year prospective study of SF-36 scores in a normative population. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(3):527–36. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-2096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fisher RA, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence and death following living and deceased donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(6):1601–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01802.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olthoff KM, et al. Outcomes of 385 adult-to-adult living donor liver transplant recipients: a report from the A2ALL Consortium. Ann Surg. 2005;242(3):314–23. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179646.37145.ef. discussion 323-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watson JM, et al. Recipient graft failure or death impact on living kidney donor quality of life based on the living organ donor network database. J Endourol. 2013;27(12):1525–9. doi: 10.1089/end.2013.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng L, et al. Comorbid cognitive impairment and depression is a significant predictor of poor outcomes in hip fracture rehabilitation. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(2):246–53. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209991487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gross CR, et al. Health-related quality of life in kidney donors from the last five decades: results from the RELIVE study. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(11):2924–34. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gordon EJ, et al. Informed consent and decision-making about adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation: a systematic review of empirical research. Transplantation. 2011;92(12):1285–96. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31823817d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gordon EJ, Ladner DP, Baker T. Standardized information for living liver donors. Liver Transpl. 2012;18(10):1260–1. doi: 10.1002/lt.23477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gordon EJ. Informed Consent for Living Donation: A Review of Key Empirical Studies, Ethical Challenges and Future Research. Am J Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gordon EG, et al. Opportunities for Shared Decision Making in Kidney Transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2012 doi: 10.1111/ajt.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Axelrod DA, et al. The interplay of socioeconomic status, distance to center, and interdonor service area travel on kidney transplant access and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(12):2276–88. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04940610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Juarez G, Ferrell B, Borneman T. Perceptions of quality of life in Hispanic patients with cancer. Cancer Pract. 1998;6(6):318–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.006006318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gordon EJ, et al. Transplant center provision of education and culturally and linguistically competent care: a national study. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(12):2701–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Caicedo JC, et al. American Transplant Congress. Boston, MA: 2009. Increasing Kidney Transplantation Rates in Hispanic through a Culturally Sensitive Hispanic Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morooka Y, et al. Reliability and validity of a new living liver donor quality of life scale. Surg Today. 2013;43(7):732–40. doi: 10.1007/s00595-012-0476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

DESCRIPTION OF SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supplementary Fig. 1. Physical Functioning Scores

Supplementary Fig. 2. Physical Role Limit Scores

Supplementary Fig. 3. Emotional Role Scores

Supplementary Fig. 4. Bodily Pain Scores

Supplementary Fig. 5. General Health Scores

Supplementary Fig. 6. Vitality Scores

Supplementary Fig. 7. Social Functioning Scores

Supplementary Fig. 8. Mental Health Scores