Abstract

OBJECTIVES

There is limited evidence regarding the effects of screening mammography in older women but its benefits are generally thought to diminish as age and comorbidity reduce life expectancy. This study prospectively examined how age and comorbidity impact screening use, cancer detection and overall survival.

DESIGN

Prospective with a median follow-up of 10.2 years.

SETTING

A population based cohort of Vermont women with data in the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System.

PARTICIPANTS

Women aged ≥ 70 years with no history of breast cancer (N=20697).

MEASUREMENTS

Rates of screening, diagnostic procedure use and breast cancer diagnosis were examined by age and comorbidity. The impact of breast cancer on overall survival was assessed in relation to detection mode, tumor characteristics and treatment.

RESULTS

Screening declined 9% per year after age 70 and 18% with each unit increase in comorbidity score, with corresponding increases in clinically detected breast cancer. Invasive cancer was associated with increased overall mortality: HR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.07 – 1.40 when screen-detected and HR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.43 – 1.96 when clinically detected. The latter reflects a large increase in absolute risk of death for women with high baseline mortality. Use of breast conserving surgery as the only treatment for stage I cancer increased markedly with age and was associated with shorter overall survival compared to women receiving radiation or mastectomy (RR = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.42 – 3.47).

CONCLUSION

Lower screening mammography use by older women is accompanied by an increase in clinically detected breast cancers, which are associated with reduced survival. Treatment received for early stage cancer influences the effect of screening on survival.

Keywords: breast cancer, screening mammography, survival, elderly

INTRODUCTION

There is limited evidence regarding the effects of screening mammography in older women,1,2 but its benefits are generally thought to diminish as age and comorbidity reduce life expectancy.3–5 For example, in 2009 the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) projected that the benefits of screening would probably be smaller for women over 70 than for younger women and decrease with age.5 The USPSTF also postulated that the harm of screening mammography “increases dramatically after about age 70 or 75 years” because women are likely to be diagnosed and treated for breast cancers that would never have become clinically apparent.5

Studies to assess the effects of screening mammography in older women have primarily focused on tumor characteristics and outcomes in women diagnosed with breast cancer.6–11 Their results have generally shown that older women with early stage breast cancers do not have increased mortality, when compared to controls or population mortality rates. This might indicate that screening detects cancers that do not impact the survival of most older women, but such an interpretation assumes that similar survival would have been observed if the cancers were not detected at an early stage.

To gain insight into the utility of screening mammography for older women, we evaluated it in the context of a general population, rather than only in women diagnosed with breast cancer. This was accomplished by prospectively examining mammography use and its effects in a historical cohort of women aged 70 and older with no prior diagnosis of breast cancer. Both the potential harms (diagnostic imaging in the absence of cancer, benign biopsy and diagnosis of in situ cancer) and benefits (early diagnosis and treatment of invasive cancer, and improved survival) of screening were assessed in relation to a woman’s age and comorbidity.

METHODS

Data sources

Data from the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System (VBCSS), a statewide registry of all breast imaging and pathology performed in Vermont,12,13 were used to assemble a cohort; determine the use of screening mammography, diagnostic imaging, and breast biopsy; identify women subsequently diagnosed with breast cancer; and obtain information about the pathologic characteristics and first course of treatment for breast cancer. Pathologic characteristics included tumor size, axillary lymph node involvement and AJCC stage I, II, III, or IV (American Joint Committee on Cancer, 1992).14 VBCSS data were linked with data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to obtain comorbidity and vital status information, as well as to identify any breast imaging, biopsy, breast cancer diagnosis and treatment that occurred outside Vermont. Diagnostic imaging was considered to have occurred in the absence of cancer and a biopsy was considered benign if no breast cancer was diagnosed within the following year.

Study population

We identified a cohort of 20697 women aged 70 or older who had at least one screening or diagnostic mammogram recorded in the VBCSS between 1996 and 2001, had no history of breast cancer, and did not decline use of their data for research. The date of a woman’s first mammogram meeting these criteria was considered her entry date into the study. Apparent errors in Social Security Numbers and birth dates precluded linkage of 1330 women to CMS data. An additional 1011 women were enrolled in Health Maintenance Organizations and CMS data do not include claims for their services. These 2341 women were excluded from all analyses that included comorbidity. Women in the cohort were followed through 31 December 2009, with a median follow-up of 10.2 years. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Vermont approved the protocol for this project.

Measurement of comorbidity

To maximally control for comorbidity at the time of study entry, we adapted the Charlson Index15 by deriving weights based on our cohort. The medical conditions comprising the Charlson Index were identified by the ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure codes associated with Medicare claims using macros for SAS® software that are publicly available from the U.S. National Cancer Institute.16 Cancer diagnosis codes17,18 were added to the SAS macros, which do not include malignancy codes. We also used ICD-9 codes to identify hip or pelvic fracture, osteoporosis, and depression for potential addition to the comorbidity index,19 because these conditions are associated with mortality in the elderly.20–22 A woman was considered to have a comorbidity if it was identified on inpatient, outpatient or physicians’ claims during the three years preceding study entry. Weights were derived from a multivariate Cox survival model with all the conditions and age at study entry as independent variables. Using the approach of Charlson et al.,15 conditions with relative risks under 1.2 were excluded, but the weights for the remaining conditions were based on the relative magnitudes of the regression coefficients rather than relative risks, because they are more appropriate when computing an additive score.23 We divided each coefficient by 0.35 (half the value of the coefficient corresponding to a relative risk of 2.0), so the scale would be comparable to the Charlson Index. The resulting weight was rounded to the nearest 0.5 and a woman’s score was computed by summing the weights of all of her comorbidities (Supplemental Table S1)

Statistical Methods

A person-years approach was used to compute rates of screening mammography, diagnostic imaging in the absence of cancer and benign breast biopsy, and incidences of carcinoma in situ (CIS) and invasive cancer. To exclude the mammograms used to identify women for the study cohort and ensure that cancer rates included only incident cases, follow-up was considered to begin one year after entry into the study. The person-years reflect changes in age, but not in comorbidity because we did not have CMS data for all years of follow-up on all women. Logistic regression with person-year as the unit of analysis was used to examine the effects of screening, age, comorbidity and their interactions on the use of unneeded diagnostic procedures and breast cancer detection.

Cox regression was used to assess the effects of a breast cancer diagnosis during follow-up on all-cause mortality in the entire cohort. All analyses included age and comorbidity score at time of study entry as continuous variables, and hospitalization in the three years before study entry as an indicator variable. Breast cancer diagnosis was included as a time-varying indicator variable having a value of one on and after the date of diagnosis and zero otherwise. Interaction terms were added to the models to examine whether the effect of a cancer diagnosis varied with age and comorbidity. Similar analyses were conducted to assess how the detection mode impacted survival by including two time-varying indicator variables representing whether or not a woman had a screen-detected or clinically detected invasive breast cancer. Cancer was considered screen-detected if there was a screening mammogram in the preceding year and clinically detected otherwise. For women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, logistic regression was used to assess the effects of screening mammography on tumor size, axillary lymph node status, stage and treatment. Cox regression was used to assess the effects of cancer stage and treatment on all-cause mortality.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Most women in the cohort (97.7%) were white. At the time of entry into the study, 54.6% were aged 70–74, 25.2% were 75–79, 13.8% were 80–84 and 6.5% were 85 or older. Comorbidity scores ranged from 0 to 13.5, but 97% of women had scores of four or lower. The majority of women (60.0%) had none of the health conditions included in the comorbidity index.

Screening, diagnostic procedures and cancer detection

Screening mammography use declined steadily with increasing age and comorbidity (Table 1). Logistic regressions with age and comorbidity score as continuous variables indicated that screening declined 9% per year after age 70 (OR = 0.909, 95% CI = 0.907 – 0.911) and 18% with each unit increase in comorbidity score (OR = 0.821, 95% CI = 0.813 – 0.829). Inclusion of both variables in the same model yielded very similar results and there was no significant interaction, indicating that the age-related decline in screening was independent of comorbidity score and vice versa. The use of diagnostic imaging and breast biopsy in women not subsequently diagnosed with breast cancer generally paralleled the screening rates, except the benign biopsy rate did not decline with increasing comorbidity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Rates of Screening Mammography, Diagnostic Procedures, and Cancer by Age and Comorbidity

| Person- years |

Screens | Diagnostic imaging in the absence of cancer |

Benign biopsy | Breast cancera | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Rate per 1000 person-yrs |

N | Rate per 1000 person- yrs |

N | Rate per 1000 person- yrs |

N | Rate per 1000 person- yrs |

% detected clincally |

||

| Age group | ||||||||||

| 70–74 | 26027 | 17598 | 676 | 1919 | 73.7 | 339 | 13.0 | 139 | 5.3 | 13.7 |

| 75–79 | 52902 | 32404 | 613 | 3454 | 65.3 | 624 | 11.8 | 307 | 5.8 | 16.9 |

| 80–84 | 38335 | 21046 | 549 | 2200 | 57.4 | 388 | 10.1 | 223 | 5.8 | 29.6 |

| ≥ 85 | 23805 | 8778 | 369 | 887 | 37.3 | 171 | 7.2 | 152 | 6.4 | 44.1 |

| Comorbidity score | ||||||||||

| 0 | 82910 | 49676 | 599 | 5141 | 62.0 | 881 | 10.6 | 462 | 5.6 | 21.0 |

| 0.5 – 1.5 | 30494 | 16350 | 536 | 1812 | 59.4 | 351 | 11.5 | 188 | 6.2 | 30.3 |

| 2.0 – 3.5 | 10657 | 4969 | 466 | 568 | 53.3 | 135 | 12.7 | 70 | 6.6 | 34.3 |

| ≥ 4 | 3248 | 1221 | 376 | 157 | 48.3 | 40 | 12.3 | 21 | 6.5 | 38.1 |

Includes both in situ and invasive breast cancers.

Breast cancer incidence (CIS and invasive) in the cohort was 5.8 per 1000 person-years of follow-up and did not differ significantly with age or comorbidity, despite the declines in screening mammography associated with these variables (Table 1). As a consequence, the clinically detected cancers increased 6% per year after age 70 (OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.04 – 1.08) and 17% per unit increase in comorbidity score (OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.06 – 1.28) .

Logistic regression results confirmed that having a screening mammogram was associated with significantly higher rates of diagnostic imaging in the absence of cancer, benign biopsy, and breast cancer diagnosis. For each of these outcomes, odds ratios (screen versus no screen) were significantly higher than one in most age and comorbidity groups (Table 2) but there were some significant interactions. In particular, the odds ratios for the effect of screening on diagnostic imaging increased significantly with increasing age (p < 0.001 for trend) and comorbidity (p = 0.015). Odds ratios for the effect of screening on benign biopsy increased significantly with age (p = 0.002) but not with comorbidity (p = 0.26). Regression estimates of the yearly probability that a woman without cancer will have diagnostic imaging or a biopsy indicated that these increases in the odds ratios were attributable to larger age-related declines in their usage among unscreened than screened women (Table 3). Odds ratios for the effect of screening on CIS diagnosis increased with age but the trend was not statistically significant (p = 0.06).

Table 2.

Odds Ratios for the Effects of Screening on the Use Diagnostic Procedures and Breast Cancer Detection by Age and Comorbidity

| Diagnostic imaging in the absence of cancer |

Benign biopsy | In situ cancers | Invasive cancers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age group | ||||||||

| 70–74 | 1.04 | 0.94 – 1.15 | 1.58 | 1.21 – 2.06 | 1.72 | 0.65 – 4.55 | 1.76 | 1.09 – 2.83 |

| 75–79 | 1.66 | 1.54 – 1.79 | 1.70 | 1.42 – 2.03 | 2.98 | 1.42 – 6.27 | 1.73 | 1.31 – 2.30 |

| 80–84 | 2.13 | 1.94 – 2.34 | 2.08 | 1.67 – 2.60 | 4.75 | 2.05 – 11.0 | 1.29 | 0.96 – 1.74 |

| ≥ 85 | 3.63 | 3.15 – 4.17 | 2.69 | 1.98 – 3.66 | 6.18 | 2.54 – 15.0 | 1.71 | 1.19 – 2.45 |

| Comorbidity score | ||||||||

| 0 | 1.87 | 1.75 – 1.99 | 1.92 | 1.65 – 2.24 | 3.68 | 2.10 – 6.42 | 1.48 | 1.19 – 1.86 |

| 0.5 – 1.5 | 1.87 | 1.69 – 2.06 | 2.22 | 1.75 – 2.80 | 3.23 | 1.24 – 8.43 | 1.65 | 1.18 – 2.29 |

| 2.0 – 3.5 | 2.41 | 2.01 – 2.88 | 2.09 | 1.46 – 2.98 | 2.51 | 0.65 – 9.76 | 1.60 | 0.96 – 2.68 |

| ≥ 4 | 2.34 | 1.69 – 3.23 | 2.61 | 1.38 – 4.93 | 2.11 | 0.87 – 5.11 | ||

Odds ratio from logistic regression of person-years data with screened (yes/no) and age or comorbidity group as independent variables.

Table 3.

Yearly Probabilities of Unneeded Diagnostic Imaging, Benign Biopsy and Breast Cancer Diagnosis for a Woman with no Comorbidities by Screening and Age Group.

| Age Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70–74 | 75–80 | 80–84 | ≥ 85 | ||

| Screened | Pa | P | P | P | |

| Diagnostic imaging in the absence of cancer | No | 0.073 | 0.047 | 0.035 | 0.018 |

| Yes | 0.075 | 0.074 | 0.069 | 0.061 | |

| Benign biopsy | No | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.004 |

| Yes | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.010 | |

| In situ cancer | No | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 |

| Yes | 0.0011 | 0.0012 | 0.0016 | 0.0022 | |

| Invasive cancer | No | 0.0027 | 0.0030 | 0.0034 | 0.0033 |

| Yes | 0.0043 | 0.0053 | 0.0044 | 0.0059 | |

Yearly probability estimated from logistic regression of person-year data, with indicator variables for the 8 combinations of screening and age categories. Comorbidity score was included as a continuous covariate.

Overall survival

Survival analyses included the 18356 women with comorbidity data. There were 7725 deaths during follow-up: 65 among 190 women diagnosed with CIS and 384 among 838 women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer. After adjustment for age, comorbidity and hospitalization history at the time of entry into the study, a diagnosis of CIS was not associated with an increased risk of death from any cause (HR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.75 – 1.56), but a diagnosis of invasive breast cancer during follow-up significantly increased all-cause mortality (HR = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.22 – 2.30). The increase in all-cause mortality risk associated with a breast cancer diagnosis was smaller when it was detected by screening (HR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.07 – 1.40) than when it was clinically detected (HR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.43 – 1.96).

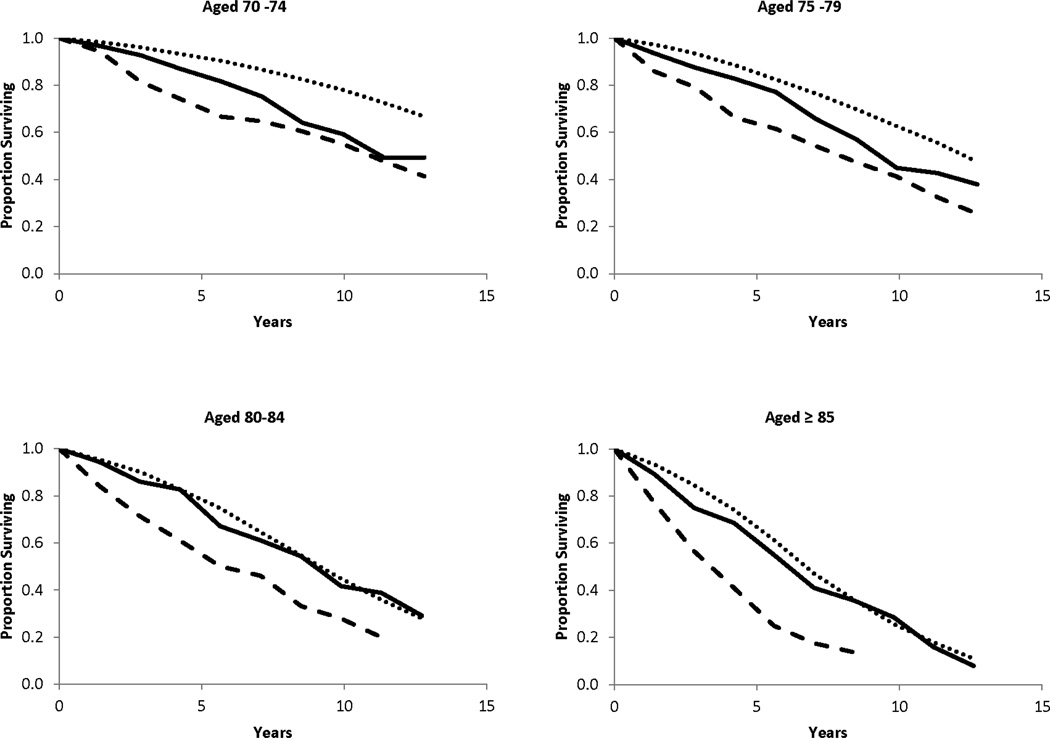

When interaction terms were included in the model, the results indicated that the hazard ratios associated with both screen-detected and clinically detected breast cancers decreased significantly with increasing comorbidity (Table 4). Increasing age at diagnosis was significantly associated with a decreased hazard ratio for screen-detected breast cancers but not for clinically detected cancers. These decreases in the hazard ratios do not reflect similar decreases in the absolute risk of death after diagnosis with invasive breast cancer because baseline mortality increases with increasing age and comorbidity. For example, in our cohort the estimated 5-year mortality risk for a 70 year-old woman with no serious comorbidity is about 3% if she does not have breast cancer and 7% if she has clinically detected invasive breast cancer (a difference of 4%). In contrast, an 85 year-old with no serious medical conditions has about a 20% chance of dying within five years if she does not have breast cancer and a 37% chance of dying if she has a clinically detected breast cancer (a difference of 17%). The absolute risk of death for women with screen-detected cancers and no serious comorbidity is 6.3% at age 70 and 23.2% at age 85, nearly the same increase over their respective baseline mortality. The relationship between detection mode, age at diagnosis and overall survival are evident in the empirical survival curves shown in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Cox Regression Models for Survival after Diagnosis with Screen-detected and Clinically Detected Invasive Breast Cancer.

| Coefficient | SE | HRa | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model without interactions | ||||

| Age at diagnosis (years-70)b | 0.100 | 0.002 | 1.11 | 1.10 – 1.11 |

| Comorbidity score | 0.314 | 0.007 | 1.37 | 1.35 – 1.39 |

| Prior hospitalization | 0.219 | 0.026 | 1.25 | 1.18 – 1.31 |

| Screen-detected cancer | 0.203 | 0.068 | 1.22 | 1.07 – 1.40 |

| Clinically detected cancer | 0.517 | 0.080 | 1.68 | 1.43 – 1.96 |

| Model with interactions | ||||

| Age at diagnosis (years-70) | 0.101 | 0.002 | 1.11 | 1.10 – 1.11 |

| Comorbidity score | 0.321 | 0.008 | 1.38 | 1.36 – 1.40 |

| Prior hospitalization | 0.218 | 0.026 | 1.24 | 1.18 – 1.31 |

| Screen-detected cancer | 0.780 | 0.149 | 2.18 | 1.63 – 2.92 |

| Age × cancer | −0.042 | 0.013 | 0.96 | 0.93 – 0.98 |

| Comorbidity × cancer | −0.138 | 0.044 | 0.87 | 0.80 – 095 |

| Clinically detected cancer | 0.886 | 0.176 | 2.43 | 1.72 – 3.42 |

| Age × cancer | −0.018 | 0.011 | 0.98 | 0.96 – 1.00 |

| Comorbidity × cancer | −0.078 | 0.033 | 0.93 | 0.87 – 0.99 |

Hazard ratio for the relative risk of mortality from any cause.

Age at diagnosis and comorbidity score were included in the model as continuous variables. Age was transformed by subtracting 70, so baseline risk corresponds to mortality for a 70 year old woman with no comorbidity or hospitalization in the previous three years

Figure 1.

Observed survival after diagnosis with screen-detected (▬▬▬) and clinically detected (▬ ▬ ▬) invasive breast cancer, and in women of comparable age who were not diagnosed with breast cancer (● ● ● ● ● ●). Cumulative proportions surviving were obtained from life table analysis and are shown for different ages at diagnosis.

Tumor characteristics

Of the 838 women with invasive breast cancer, 803 had available information for tumor size, 746 for axillary node involvement, and 626 for AJCC stage (Supplemental Table S2). Clinically detected cancers were more likely to be larger than 2 cm (OR = 3.53, 95% CI = 2.59 – 4.83), have lymph node involvement (OR = 2.62, 95% CI = 1.80 – 3.82) and be stage II or higher (OR = 3.33, 95% CI = 2.36 – 4.67) than screen-detected cancers after adjustment for age. Compared to women who did not develop breast cancer, there was no overall increase in mortality risk among women diagnosed with stage I breast cancer (HR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.81 – 1.17) after adjustment for age, comorbidity and prior hospitalization, but the hazard ratio varied with age at diagnosis and comorbidity. It was highest for women aged 70 who had no comorbidity (HR=1.71, 95% CI = 1.02 – 2.13) and decreased by 4% per year with increasing age at diagnosis and by 12% with each unit increase in comorbidity score. Mortality risk was higher for stage II cancer (HR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.49 – 2.11) and stage III or IV cancer (HR = 4.96, 95% CI = 2.96 – 8.30). There were no significant interactions with age at diagnosis for these higher stage cancers, but the hazard ratios decreased significantly with increasing comorbidity.

Breast cancer treatment

Information on both treatment and cancer stage was available for 602 of the women with invasive cancer, and it indicated that treatment was highly influenced by age at diagnosis (Supplemental Table S3). Among women aged 70–74, 7.2% of those with stage I cancer and 7.3% of those with stage II cancer received only BCS (excisional biopsy or partial mastectomy without radiation or chemotherapy), while among women aged 85 and older 61.4 % of stage I cancers and 47.2% of stage II cancer were treated only with BCS. Overall, from age 70 the odds of receiving BCS as the only treatment increased 18% per year (OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.14 – 1.23) after adjustment for the effects of tumor stage, comorbidity, and detection mode. Neither detection mode nor comorbidity was related to receiving only BCS, independent of its relationship with age. Among women with stage I cancers, those who received only BCS had significantly higher overall mortality than women who received other treatment (HR = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.42 – 3.47), independent of age and comorbidity. Among stage II cancers, overall mortality for women who received only BCS did not differ significantly from those receiving additional treatment. The effect of treatment was not examined in the 42 women with stage III and IV cancers. Because the majority (67.0%) of screen-detected cancers were stage I, those treated only with BCS had poorer overall survival than those receiving other treatments (HR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.06 – 1.97).

DISCUSSION

Our study found a substantial decline in the use of screening mammography as women age and a corresponding increase in clinically detected breast cancer. Diagnosis with invasive breast cancer was associated with increased overall mortality, regardless of detection mode, but the increase was larger for the clinically detected cancers. Clinically detected breast cancers were more likely to be larger (> 2 cm), have lymph node involvement and be stage II or higher. Among women with stage I breast cancer, overall mortality was increased in those who received breast conserving surgery without radiation or chemotherapy.

Age-related declines in screening mammography use have been observed in previous studies,24,25 but we also found that the use of diagnostic imaging and biopsy in women who do not have cancer declined markedly with age. Although recall for diagnostic imaging and breast biopsy in the absence of breast cancer is considered a harm of screening, the decline that we observed in the use of these procedures was primarily among unscreened women. This suggests that clinical detection of breast cancer may be delayed as women advance in age. In women undergoing screening, there were much smaller age-related declines in the use of diagnostic imaging and breast biopsy. The overall screening recall rate in our cohort (8.8 recalls for diagnostic imaging per 100 screens) was slightly lower than we found previously for women aged 50–69 (9.8 per 100 screens).26 For older women, diagnosis of CIS can also be considered a harm of screening and we found that detection of CIS in our cohort was similar to women aged 50–69 (1.3 versus 1.0 per 1000 screens).

The increased relative risk of mortality from any cause that we observed in women diagnosed with breast cancer was fairly modest, particularly for screen-detected cancers, but corresponds to substantial increases in absolute risk because baseline mortality risk in the elderly is high and rises sharply with age and comorbidity. In addition, although the increase in risk diminished with age and comorbidity, our survival model estimated that being diagnosed with clinically detected invasive breast cancer substantially reduces survival for all but the oldest and most infirm women (e.g. 80 year-old women with comorbidity scores ≥ 9.0 or 90 year-old women with comorbidity scores ≥ 6.5).

We examined the effects of screening mammography on survival by prospectively following a large cohort of older women with no previous breast cancer. This approach has the advantage of not requiring the use of mortality rates or control subjects from an external population, which may not accurately reflect baseline survival in the women being studied. For example, in a case-control study Schonberg et al. used SEER-Medicare data to identify breast cancer cases and matched them to female Medicare beneficiaries by age, cancer registry area, and year.10 After adjustment for comorbidity and other potential confounders, they found significantly better survival in women with DCIS and stage I breast cancer than in controls without breast cancer. The overall survival for women with CIS or stage I cancer in our cohort was nearly identical to that for women without cancer and the hazard ratio associated with stage II cancer (1.77) was substantially higher than the estimate of 1.2 obtained by Schonberg et al. However, it is interesting to note that if mortality in the control population used by Schonberg et al. was comparable to what they observed in women with DCIS, their hazard ratio for stage II cancer would be about 1.7, very similar to our estimate.

Some of the difference in survival that we observed between women with screen-detected and clinically detected cancers can be attributed to the time it would have taken the screen-detected cancer to progress enough to be detected clinically (sojourn time), as well as the fact that slower growing cancers have more opportunity to be detected by screening (length-time bias). These seem unlikely to account for the entire difference because women with stage I cancers that were treated only with breast conserving therapy had poorer survival than women of similar age and comorbidity who also received radiation or who had a mastectomy. This finding, coupled with the increase in clinically detected cancers as screening declines and the shorter survival in women with these cancers, indicates that at least some screen-detected cancers will progress enough to impact survival if they are not found and treated earlier.

Our findings regarding the effects of treatment should be interpreted with caution because the analysis included only 71% of the women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer. We had only basic information about initial surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, and no information about hormone therapy. We could only control for tumor stage because histologic grade and hormone receptivity data were missing for many women. In addition, information about functional status, treatment preferences and other factors that influence choice of therapy were unavailable. These data deficiencies make it particularly difficult to interpret the treatment results for advanced cancers. However, our results for stage I cancers are consistent with other studies that found strong age-related declines in the use of standard treatments and poorer survival in women with stage I cancer who receive only minimal treatment, independent of age and comorbidity7,10,27–29

As with all observational studies, it is difficult to assess the effects of screening on survival independent of other factors which may be associated with its use. Although we controlled for age and comorbidity, screening use may be related to socioeconomic and other factors that impact mortality, such as health behaviors, functional status and mobility. Education was examined as a potential confounder and it did not influence the relationship between screening and survival, but the women in our cohort were predominately white and few had had substantial comorbidity. Therefore, the results may not be applicable to all women, particularly those in very poor health.

Although the efficacy of screening mammography for older women can only be established by a clinical trial, our study provides evidence that reduced use of screening mammography by older women is accompanied by an increase in clinically detected breast cancer and that these cancers can substantially impact survival. These results raise questions about the advisability of terminating screening solely on the basis of age and comorbidity, and should be useful as input data for the mathematical models of screening efficacy used to inform USPSTF recommendations.30

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant KG090134 from Susan G. Komen for the Cure. Data collection for the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System was supported by Grant UO1-CA70013 from the National Cancer Institute.

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsors had no role in the conception, design, analysis, interpretation of data or in the drafting, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: Pamela Vacek: conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript. Joan Skelly: design, analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content.

REFERENCES

- 1.Humphrey LL, Helfand M, Chan BK, et al. Breast cancer screening: A summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:347–360. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-5_part_1-200209030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nystrom L, Andersson I, Bjurstam N, et al. Long-term effects of mammography screening: updated overview of the Swedish randomised trials. Lancet. 2002;359:909–919. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd CM, McNabney MK, Brandt N, et al. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: An approach for clinicians: American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:E1–E25. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society recommendations for early breast cancer detection in women without breast symptoms (online) [Accessed November 12, 2012]; Available at: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/moreinformation/breastcancerearlydetection/breast-cancer-early-detection-acs-recs. [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:716–726. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cyr A, Gillanders WE, Aft RL, et al. Breast cancer in elderly women (>/= 80 years): variation in standard of care? J Surg Oncol. 2011;103:201–206. doi: 10.1002/jso.21799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diab SG, Elledge RM, Clark GM. Tumor characteristics and clinical outcome of elderly women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:550–556. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.7.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Freund KM, et al. Mammography use, breast cancer stage at diagnosis, and survival among older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1226–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McPherson CP, Swenson KK, Lee MW. The effects of mammographic detection and comorbidity on the survival of older women with breast cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1061–1068. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schonberg MA, Marcantonio ER, Ngo L, et al. Causes of death and relative survival of older women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1570–1577. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegelmann-Danieli N, Khandelwal V, Wood GC, et al. Breast cancer in elderly women: Outcome as affected by age, tumor features, comorbidities, and treatment approach. Clin Breast Cancer. 2006;7:59–66. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2006.n.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geller BM, Worden JK, Ashley JA, et al. Multipurpose statewide breast cancer survelliance system: the Vermont experience. J Registry Manage. 1996;23:168–174. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballard-Barbash R, Taplin SH, Yankaskas BC, et al. Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: A national mammography screening and outcomes database. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1001–1008. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.4.9308451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Joint Committee on Cancer. Manual for Staging of Cancer. 4th Ed. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Cancer Institute. SEER-Medicare: Calculation of Comorbidity Weights (online) Available at: http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/program/comorbidity.html.

- 17. Accessed January 6, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: Differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chronic Conditions Warehouse categories. Buccaneer Computer Systems and Services, under contract with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (online) Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 21. https://www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories. Accessed February 3, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blazer DG, Hybels CF, Pieper CF. The association of depression and mortality in elderly persons: A case for multiple, independent pathways. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M505–M509. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.8.m505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, et al. Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA. 2009;301:513–521. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colon-Emeric CS, et al. Meta-analysis: Excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:380–390. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, et al. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison RV, Janz NK, Wolfe RA, et al. 5-Year mammography rates and associated factors for older women. Cancer. 2003;97:1147–1155. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kagay CR, Quale C, Smith-Bindman R. Screening mammography in the American elderly. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofvind S, Vacek PM, Skelly J, et al. Comparing screening mammography for early breast cancer detection in Vermont and Norway. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1082–1091. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Fioretta G, et al. Undertreatment strongly decreases prognosis of breast cancer in elderly women. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3580–3587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eaker S, Dickman PW, Bergkvist L, et al. Differences in management of older women influence breast cancer survival: Results from a population-based database in Sweden. PLoS Med. 6006;3:e25. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schonberg MA, Marcantonio ER, Li D, et al. Breast cancer among the oldest old: Tumor characteristics, treatment choices, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2038–2045. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandelblatt JS, Cronin KA, Bailey S, et al. Effects of mammography screening under different screening schedules: Model estimates of potential benefits and harms. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:738–747. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.