Abstract

Context

Patient death is common in long-term care. Yet, little attention has been paid to how direct care staff members, who provide the bulk of daily long-term care, experience patient death and to what extent they are prepared for this experience.

Objectives

To 1) determine how grief symptoms typically reported by bereaved family caregivers are experienced among direct care staff, 2) explore how prepared staff members were for the death of their patients, and 3) identify characteristics associated with their grief.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of direct care staff experiencing recent patient death. Participants were 140 certified nursing assistants and 80 homecare workers. Standardized assessments and structured questions addressed staff (e.g., preparedness for death), institutional (e.g., support availability), and patient/relational factors (e.g., relationship quality). Data analyses included bivariate group comparisons and hierarchical regression.

Results

Grief reactions of staff reflected many of the core grief symptoms reported by bereaved family caregivers in a large-scale caregiving study. Feelings of being “not at all prepared” for the death and struggling with “acceptance of death” were prevalent among staff. Grief was more intense when staff-patient relationships were closer, care was provided for longer, and staff felt emotionally unprepared for the death.

Conclusion

Grief symptoms like those experienced by family caregivers are common among direct care workers following patient death. Increasing preparedness for this experience via better training and support is likely to improve the occupational experience of direct care workers, and ultimately allow them to provide better palliative care in nursing homes and homecare.

Keywords: Grief, bereavement, preparedness, patient death, caregiving, nursing assistants, homecare workers, direct care staff

Introduction

A critical setting of palliative care is the long-term care (LTC) environment1 where the main care providers are certified nursing assistants (CNAs) in nursing homes and home health aides (HHAs) in the community. Both are referred to as direct care workers because they provide the bulk of hands-on care. Compared with other staff, CNAs and HHAs have the most daily interactions with patients. They often see themselves as family surrogates2 or as having family-like ties.3, 4 Such family-like feelings toward patients have been identified as critical to compassionate care. In a national survey, nursing home administrators even indicated “staff treating residents like family” as their best practice, second only to “keeping the resident comfortable.” 5

When direct care providers have family-like ties to a patient, however, they may experience family-like reactions when the patient dies. A few studies have provided evidence for grief among CNAs,6, 7 and one study identified grief as a contributor to burnout.8 No comparable insights exist for HHAs. However, learning about the experience of HHAs after patient death is equally important, as LTC is increasingly provided in the community9 and a HHA is often the only person the homecare client interacts with on a regular basis. Therefore, it is possible that relationships between HHAs and homecare clients are even closer than relationships between CNAs and nursing home residents, and that as a result, HHAs experience more intense grief.

Largely, the topic of death in LTC has been muted3 and grief experienced by front-line staff has been recognized as one form of “disenfranchised grief.”10 Considering this lack of attention to how patient death affects direct care staff, an important question is how well staff members can be prepared to deal with death and related grief. Preparedness for death has been identified as an important contributor to family caregiver bereavement outcomes.11-13 There is also evidence that preparedness for death is a multidimensional construct, and that caregiver preparedness can be enhanced by targeting cognitive/informational and emotional preparation.13,14 In a palliative care context, this distinction is particularly relevant because both aspects reflect the direct care worker's role and perspectives within the care team (e.g., understanding of patient's condition and an expanding focus on comfort and natural death). If preparing family caregivers for the death of their loved one is considered an integral component of good end-of-life care,14 this notion should be expanded to formal caregivers who replace or complement family caregivers. We are not aware of any study that has examined preparedness for death and its association with grief among formal caregivers.

We had three aims for this study. Our first aim was to determine how grief symptoms typically reported by family caregivers are experienced among direct care staff. Besides describing grief symptoms of the direct care staff assessed for this study, we compared their grief symptoms with those of family caregivers of a nationally representative sample. Our second aim was to determine how prepared staff members were for patient death, both in terms of information about the patient's condition and emotionally. In the context of both aims, we also evaluated to what extent CNAs differ from HHAs. Finally, we were interested in identifying staff, institutional, and patient and relationship (between caregiver and patient) factors that may be related to direct care workers’ grief levels following patient death. These factors were selected as they had been found to predict grief in previous studies.6, 7, 11-13, 15, 16

Methods

Recruitment and Eligibility

Actively employed CNAs were recruited from three large nursing homes, all part of the same care system in Greater New York, between 2010-2012. To be eligible, CNAs had to have experienced within approximately the past two months the death of a patient for whom they were a primary CNA. Patient deaths were tracked via electronic medical records. CNAs were approached on the units, informed about the study, and asked if they were interested in participating. Of the 824 CNAs meeting eligibility criteria, we approached 219; 143 agreed to participate and 76 refused; three did not complete the interview. The overall response rate was 64%. The remaining 605 CNAs could not be reached within two months of resident death, largely because of the CNAs’ schedules (sick time, vacation, or leave) and limitations in research staffing (as there were more resident deaths than we could follow within the designated two month time frame, beyond which we only interviewed when initial contact and wish to participate had already been established). Participant CNAs were representative of the organization's CNAs with regard to age, gender, race/ethnicity, and length of employment.

Procedures for HHA recruitment were modified to accommodate the homecare context. Additionally, HHAs could choose to complete the interview in Spanish. In contrast to the CNAs, English language proficiency is not a job requirement for HHAs and the pool of potential participants included individuals whose primary language was Spanish. Recruitment included HHAs who were employed by the same LTC organization that employed the enrolled CNAs, as well as HHAs employed at other agencies subcontracted by the LTC organization. The participating agencies’ administrative staff informed us when client deaths occurred and asked the primary HHA of the deceased client if it was permissible for study personnel to contact them. If the HHA agreed, study staff followed up with a phone call to explain the study and schedule an interview. We attempted to reach a total of 122 HHAs. Of those, 38 could not be reached within two months of the client's death. Of the 84 we were able to approach, 80 agreed to participate and four refused, resulting in a response rate of 95%. A comparison between enrolled HHAs and the larger pool of HHAs serving the organization's clients indicated that the HHA sample, too, was representative of the population they were drawn from in terms of age, gender, and length of employment. A comparison with respect to race/ethnicity, however, indicated a difference in the balance of Black versus Hispanic HHAs. Whereas our study sample was 67% Black and 29% Hispanic, the larger pool of HHAs was 33% Black and 64% Hispanic.

Data Collection and Measures

Participants were interviewed by trained interviewers with a Bachelor's or Master's degree. Written informed consent was obtained prior to all interviews. Participants received $30 for their time. Interviews were conducted in-person outside of work time, at a place and time of the participant's convenience, and lasted on average 80 minutes. Data analyses were based on a selection of measures from this interview pertaining to the aims which constitute the focus of this paper.

Emotional Response to Patient Death

Grief symptoms were assessed with the 13-item version of the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief,17 a validated scale to assess current symptoms associated with separation distress. Responses ranged from 1=completely false to 5=completely true. This scale has been successfully used in large national bereavement studies15, 16 and thus is suitable for comparison with the family bereavement literature. Cronbach alphas in the present study were 0.91 (CNAs) and 0.76 (HHAs).

Staff Person Factors

Sociodemographic characteristics assessed included age, gender, education, marital status, and race/ethnicity. Additional staff characteristics assessed were years in profession, number of patient deaths in past months, both tapped with single-item questions, and months since death (time from date of patient death to interview). Preparedness for deathwas addressed with two questions based on prior literature on family caregiver preparedness for death,13, 14 one assessing mental and emotional preparedness (“To what extent were you prepared for the patient's death mentally or emotionally?”), and one assessing knowledge aspects (“To what extent were you prepared for the patient's death in terms of what you knew about his/her condition?”). Responses ranged from (1) not at all to (4) very much.

Institutional/Agency Factors

Care setting was either (1) nursing home or (0) homecare setting. Support availability was measured with the questions: “To what extent do you feel you can turn to your supervisor for support?” and “To what extent do you feel you can turn to your coworkers for support?” Responses ranged from (1) not at all, to (4) very much. Higher values represented greater perceived support availability.

Patient/Relational Factors

Patient Suffering: participants were asked to rate the extent to which the patient suffered during the last weeks of life on a scale from (0) not suffering at all, to (10) suffered terribly.

Caregiving benefits were assessed with an 11-item scale that has emerged as a predictor of bereavement outcomes in previous studies.15, 16 Each item began with the stem “Providing help to (name) has ...,” followed with specific items such as “made me feel useful” and “enabled me to appreciate life more.” Responses ranged from (1) disagree a lot, to (5) agree a lot. Higher scores indicated greater caregiving benefits. Cronbach alphas were 0.80 (CNAs) and 0.78 (HHAs).

Months caring for patient was assessed with a single item asking about length of time assigned to the patient.

Relationship quality was assessed with a four-item scale successfully used in a previous large-scale caregiving study18 to measure rewarding aspects in the relationship between caregiver and care recipient. Staff members were asked how often a) they felt happy with their relationship with the resident, b) the patient made them feel good about themselves, c) they felt very emotionally close to the patient, and d) they felt bored with the patient. Responses ranged from (1) never to (4) always. Higher scores indicated closer relationships. Cronbach alphas were 0.71 (CNAs) and 0.76 (HHAs).

Comparison Sample of Family Caregivers

Grief symptoms reported by direct care staff were compared to grief in a sample of bereaved caregivers (N=217) drawn from a larger population-based sample of dementia caregivers who were part of a multisite caregiver randomized controlled trial, Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health (REACH). REACH enrolled 1222 caregiver and recipient dyads from 1996 to 2000 at six sites in the U.S. Caregivers and patients were followed for 18 months (see Wisniewski et al.19 for a detailed description of the study). The bereaved caregiver sample of the REACH study was chosen as a comparison sample because these family caregiver were involved in long-term care provision, and grief symptoms were assessed with the same measure used in the data collection with CNAs and HHAs as described above.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses included bivariate group comparisons and hierarchical regression. Chi-square and t-tests were used for all group comparisons, including comparing CNAs and HHAs on all major study variables, as well as comparing CNAs, HHAs, and family caregivers with respect to grief symptoms. To illustrate the reporting pattern of the grief symptoms and compare them across groups, dichotomized categorical variables were computed to indicate for each item whether or not 4=mostly true or 5=completely true was endorsed.

To examine factors associated with grief, the total sum score was used, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of grief. Prediction of grief levels was examined with a hierarchical regression model that included staff factors (block 1), institutional factors (block 2), and patient/relational factors (block 3). Variables were entered in these three blocks because previous bereavement research has categorized predictors of grief in terms of person, contextual, and relational characteristics.8, 10, 12, 13 Because CNAs and HHAs did not differ with respect to grief levels, this analysis was conducted for the total sample.

Results

Sample characteristics of CNAs and HHAs are displayed in Table 1. Reflective of the larger population of CNAs in Greater New York, CNAs were mostly minority women. Most were high school graduates or had at least some college. A little over half the sample was married or living as married. Similar to the CNA sample, HHAs were primarily female and of minority backgrounds. Educational levels were also similar. HHAs were significantly younger than CNAs, less likely to be currently married and more likely to be never married than CNAs. HHAs were more likely to identify as Hispanic, and CNAs were more likely to be Black. Relative to HHAs, CNAs had been in the profession longer and had cared for the patient longer.

Table 1.

Description Information for Sample Characteristics and Major Study Variables

| CNAs (N=140) | HHAs (N=80) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range | N (%) | Mean (SD) | Range | N (%) | Significance |

| Gender (Female) | 125 (89) | 77 (96) | χ2 (1, N=220) = 3.29 a | ||||

| Age, yrs | 50.5 (8.9) | 24-69 | 43.2 (12.5) | 19-66 | t(124) = 4.55 b | ||

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 16 (11) | 23 (29) | χ2 (1, N=219) = 10.31 c | ||||

| Race | χ2 (4, N=216) = 13.70 c | ||||||

| Black | 117 (86) | 52 (67) | |||||

| White | 3 (2) | 8 (10) | |||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander/Native American | 2 (1) | 3 (4) | |||||

| Other | 16 (12) | 15 (19) | |||||

| Education | χ2 (7, N=220) = 7.23 | ||||||

| Grades 7-9 | 10 (7) | 8 (10) | |||||

| Grades 10-11 | 9 (6) | 8 (10) | |||||

| GED | 13 (9) | 4 (5) | |||||

| High School graduate | 54 (39) | 25 (31) | |||||

| Some college | 42 (30) | 25 (31) | |||||

| College graduate | 10 (7) | 9 (11) | |||||

| Marital status | χ2 (4, N=219) = 19.52 c | ||||||

| Married | 67 (48) | 21 (26) | |||||

| Living as married | 7 (5) | 2 (3) | |||||

| Divorced/separated | 35 (25) | 24 (30) | |||||

| Widowed | 8 (6) | 2 (3) | |||||

| Never married | 22 (16) | 31 (39) | |||||

| Years in profession | 15.22 (7.4) | 1-35 | 6.5 (6.6) | .16-29 | t(218)=8.74 b | ||

| Months since death | 1.51 (1.2) | 0-5 | 1.08 (0.98) | 0-3 | t(188) = 2.99 c | ||

| Other patient deaths past months | 1.77 (0.89) | 1-6 | 1.15 (0.45) | 1-3 | t(218) = 5.81 b | ||

| Current grief | 31.49 (13.2) | 13-65 | 33.16 (12.5) | 13-65 | t(217) = −0.92 | ||

| Preparedness for death | |||||||

| Emotional – not at all | 39 (28) | 33 (41) | χ2 (1, N=220) = 4.15 d | ||||

| Informational – not at all | 46 (33) | 35 (44) | χ2 (1, N=220) = 2.60 | ||||

| Support availability supervisor | 2.80 (1.3) | 2.63 (1.2) | t(218) = 0.94 | ||||

| Support availability coworker | 3.33 (0.96) | 2.13 (1.2) | t(138) = 7.61 b | ||||

| Patient suffering | 4.38 (3.3) | 0-10 | 5.28 (3.5) | 0-10 | t(217) = −1.87 a | ||

| Caregiving benefits | 52.35 (4.5) | 27-55 | 52.70 (3.7) | 38-55 | t(218) = −0.59 | ||

| Months caring for patient | 38.86 (36.9) | 1-150 | 18 (29) | .03-168 | t(216) = 6.12 b | ||

| Relationship quality | 10.65 (1.8) | 4-12 | 10.45 (1.9) | 3-12 | t(218) = 0.76 | ||

GED = General Educational Development (legal equivalent of high school diploma).

P < 0.10.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.01.

P< 0.05.

Table 2 depicts grief symptom endorsement of CNAs and HHAs from our study, as well as the bereaved family caregivers from REACH. Comparing CNAs and HHAs with family caregivers, most grief symptoms were reported by both professional and family caregivers. The percentage of staff experiencing the grief symptoms was, with a few exceptions, between one-third and over 70%. Only four of 13 items showed a contrasting pattern of being reported by a minority of staff vs. half or a majority of family caregivers. However, even here, it is noted that over a third endorsed “I can't avoid thinking about [...].” Moreover, around one-third of both CNAs and HHAs endorsed the item “No one will ever take [...] place in my life,” a statement reflective of very close unique relationships such as familial ones. Even items such as “Sometimes I very much miss him/her,” which was endorsed significantly more often by family caregivers compared with staff, received majority endorsement in all groups. Endorsements of other core indicators of grief, such as “It's painful to recall memories of him/her,” were similar for all.

Table 2.

Grief Symptoms Endorsed as Mostly or Completely True (1 vs 0) by CNAs, HHAs, and Family Caregivers

| CNAs N=140 | HHA N=80 | Family Caregivers N=217 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grief Symptoms | N (%) | N (%) | χ2 (2, N=437) | |

| Clearly Less Common in Staff | ||||

| I still cry when I think of [...]. | 27 (19) | 22 (28) | 206 (51) | 48.92 |

| At times I still feel the need to cry for [...]. | 33 (24) | 18 (23) | 244 (59) | 76.29 a |

| I can't avoid thinking about [...]. | 41 (30) | 29 (37) | 233 (57) | 36.60 a |

| No one will ever take [...]'s place in my life. | 38 (27) | 28 (35) | 342 (84) | 183.74 a |

| Similarities in Endorsements Across Groups | ||||

| Sometimes I very much miss [...]. | 106 (76) | 56 (71) | 363 (89) | 24.39 a |

| Things/people around me remind me of [...]. | 80 (58) | 36 ( 46) | 286 (70) | 20.78 a |

| I still get upset when I think about [...]. | 30 (21) | 32 (41) | 189 (46) | 27.13 a |

| I am preoccupied with thoughts about [...]. | 41 (30) | 31 (39) | 175 (43) | 7.91 b |

| Even now it's painful to recall memories of [...]. | 67 (48) | 34 (43) | 206 (51) | 1.56 |

| I hide my tears when I think of [...]. | 36 (26) | 26 (33) | 143 (35) | 4.20 |

| I cannot accept [...]'s death. | 25 (18) | 11 (14) | 64 (16) | 0.59 |

| I feel it's unfair that [...] died. | 31 (22) | 17 (21) | 75 (18) | 1.11 |

| I am unable to accept [...]'s death. | 24 (17) | 10 (13) | 54 (13) | 1.46 |

P < 0.001.

P < 0.05.

AU: NOTE THIS DID NOT APPEAR IN THE TABLE: **p < .01

Reporting patterns of grief symptoms were largely similar for CNAs and HHAs, with the exception of two items on which CNAs but not HHAs differed significantly from family caregivers (“I still get upset thinking about [...]” and “I am preoccupied with thoughts about [...]”) and one item on which HHAs but not CNAs differed from families (“Things/people remind me of [...]”). Finally, it is noted that staff and family caregivers did not significantly differ on the three items pertaining to acceptance of death, and that CNAs had the most consistently high endorsements on these items.

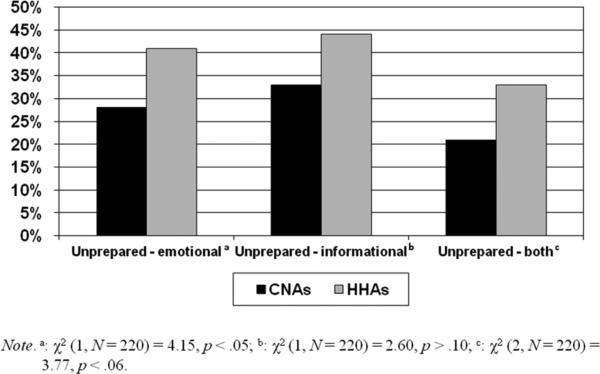

Findings with regard to preparedness for death among CNAs and HHAs showed that a significant portion of the staff were unprepared for their patient's death (Table 1, Fig. 1). About one-third of CNAs and two-fifths of HHAs reported feeling “not at all” prepared for the death both emotionally or in terms of the information they had about the patient's condition. HHAs were significantly more likely than CNAs to report feeling “not at all” emotionally prepared.

Figure 1.

CNAs (N = 140) and HHAs (N = 80) “Not at All” Prepared for Death of Patient

Findings from the hierarchical regression analysis (Table 3) showed that, independent of all other predictors, the staff factors explained 8% of individual differences in grief, which was primarily because of emotional preparedness: those who were more emotionally prepared for death reported lower levels of grief. The institutional factors yielded no unique variance explanation. Finally, the patient/relational factors explained 7% of independent variance, with positive significant effects for staff-patient relationship quality and months caring for the patient.

Table 3.

Staff, Institutional, and Patient/Relational Factors Predicting Total Grief Levels

| B | SE | β | R2 change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff factors: | 0.08 a | |||

| Age | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.03 | |

| Education | 0.60 | 0.64 | 0.06 | |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 3.95 | 3.17 | 0.12 | |

| Race (Black) | −0.09 | 2.81 | −0.00 | |

| Months since death | −1.01 | 0.81 | −0.09 | |

| Other patient deaths past months | −0.85 | 1.16 | −0.05 | |

| Emotional preparedness | −2.12 | 0.99 | −0.19 a | |

| Informational preparedness | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.09 | |

| Institutional factors: | 0.00 | |||

| Care setting (nursing home) | −3.20 | 2.46 | −0.12 | |

| Support availability supervisor | −0.13 | 0.79 | −0.01 | |

| Support availability coworkers | 1.12 | 0.86 | 0.10 | |

| Patient/relational factors: | 0.07 b | |||

| Patient suffering | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.06 | |

| Caregiving benefits | 0.53 | 0.44 | 0.09 | |

| Months caring for patient | 4.66 | 1.79 | 0.20 a | |

| Relationship quality | 1.67 | 0.70 | 0.17 a | |

| Total R2 | 0.15 b |

Note: Listwise N = 213; Care setting: CNAs in nursing home vs. HHAs in homecare.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the types of grief symptoms direct care workers experience after patient death by considering them against the background of family caregiver grief, and to examine direct care workers’ preparedness for death. Because grief among HHAs has not been examined previously, the present study also makes an important contribution by drawing attention to the experience of HHAs who increasingly play a vital role in long-term care.9 Although some symptoms were less typical among staff than family (e.g., crying), other reactions were reported by the majority of all (e.g., missing the deceased) or were similarly common (e.g., painful to recall memories). The pattern of grief symptoms was very similar for CNAs and HHAs, with a few exceptions. For example, CNAs reported that things/people remind them of the deceased more often than HHAs, likely because they remain in the environment in which they cared for the patient, whereas HHAs do not. But overall, our findings for CNAs as well as HHAs demonstrated that, consistent with previous work on grief among CNAs,6, 7 grief in response to patient death is not only a prevalent experience for direct care workers, but also bears a similar pattern to grief experienced by bereaved family caregivers. Findings further showed that grief was likely to be more intense when the relationship was closer and lasted over a longer period of time. This is important to consider, as continuity in staffing and relationships20 are critical elements of high quality LTC.

With regard to preparedness, many direct care workers felt completely unprepared for the death of their patient both emotionally and in terms of the information they had about the patient's condition. It is also striking that at least a third of the sample indicated struggling with acceptance of death, and that this pattern of item endorsement was most consistent among CNAs who work in an environment where elders are often near the end life and death is not an infrequent occurrence. Why might this be the case? One could argue the professional goal of maintaining the patient and performing daily care counteracts the ability or willingness to recognize the possibility of patient death.10 The point also has been made that distancing oneself from the reality of death is self-protective for formal caregivers.21 However, the lack of informational preparedness among the staff suggests they also had insufficient information about the patient's condition. Although having information does not automatically lead to emotional preparedness, the two were strongly interrelated (r = 0.63, P < 0.001).

We purport that, when patient death is a likely occurrence, feeling unprepared for death or struggling with acceptance of death is not an adaptive inner state for LTC direct care workers because it requires a constant effort of denying the inevitable. Whereas it is recognized that direct care staff develop close bonds with patients2-4, 22 the “flip-side” of this attachment is that they can experience grief when a patient dies, as shown by our findings. The important question thus becomes, what can be done to retain caring relationships with patients while reducing the intensity of grief? This question should be discussed alike to other professional hazards, such as suffering back pain from lifting patients. The goal cannot be to stop lifting patients in order to avoid physical repercussions. Rather, staff must be trained to lift patients in ways that do not cause injury. Similarly, the goal in the context of patient loss would not be to prevent close relationships but to find ways to help staff deal with patient death. Consistent with family bereavement research,11 lack of emotional preparedness was a significant predictor of more intense grief, suggesting that increasing direct care workers’ preparedness for death could be a pathway to mitigating the grief experience. A related recommendation is to better integrate front-line staff into the care team processes. This would have multiple advantages for quality of care, including maximizing direct care workers’ ability to monitor patients and act as their advocates by alerting other members of the care team to emerging problems, as well as creating a more empowered and more knowledgeable workforce.

Several potential limitations of our research deserve mention. First, although we offered recruitment and interviews in Spanish, we did not succeed in adequately representing the larger percentage of Hispanic HHAs in Greater New York. Future research might use an oversampling strategy to gain better representation of this group. Second, it may be useful to explore how CNAs and HHAs interpreted some of the grief items. For example, it seemed surprising that one-third of the staff endorsed the item “'No one will ever take [...]'s place in my life.” It is possible that those who did thought they were asked if they considered the patient who died to be special or unique, rather than that it would be unbearable for them to live without the resident. One could attempt to clarify such aspects with open-ended follow-up questions. Third, retrospective assessments of preparedness for death can always be biased by the person's adjustment to the loss or other current events. Thus, future prospective research would be helpful to further clarify the role of preparedness in grief among staff. Fourth, the total amount of variance in grief explained in the presented regression model suggests an important role of other factors that were not assessed. One is prior mental health, which typically explains a major portion of variance in family bereavement outcomes.15, 23 We decided against including assessments of prior mental health as this is a potentially problematic topic to touch on in the work context. However, future research exploring the role of staff mental health in adaptation to patient death and related challenges in the work place would be helpful. It is possible, for example, that mental health problems impede a staff member's ability to take advantage of training, preparation, or support options offered. Yet, the main purpose of the regression analysis presented herein was met, which was to evaluate if preparedness for death and aspects of the staff-patient relationship would have significant associations with grief after accounting for person and context factors found to contribute to predicting grief in previous relevant studies.

Study findings clearly demonstrate that the experiences of CNAs and HHAs reflect core grief symptoms reported by family caregivers, and suggest that greater acknowledgment of and preparation for this experience would enable direct care staff to better cope with patient death and their own grief. A lack of awareness for and acknowledgement of patient death and staff grief in response to such deaths in the LTC context is potentially detrimental to the core goals of palliative end-of-life care. To provide optimal palliative care at the end of life, we need a workforce that is prepared to deal with death and dying, and this is needed throughout the ranks of staffing and includes the direct care staff who have the most consistent and active relationships with patients. Future work should focus on developing training and support options that allow direct care staff to become more enabled members of palliative care teams.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (1 R03AG034076), as well as by several private donors (Kathrin Boerner, Principal Investigator).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

None of the authors had any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Meier DE, Lim B, Carlson MD. Raising the standard: palliative care in nursing homes. Health Aff. 2010;2929:1136–1140. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chichin ER, Burack OR, Olson E, Likourezos A. End-of-life ethics and the nursing assistant. Springer Publishing Company. New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moss MS, Moss SZ, Rubinstein RL, Black HK. Metaphor of “family in staff communication about dying and death. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58:S290–S296. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.5.s290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piercy KW. When it is more than a job: close relationships between home health aides and older clients. J Aging Health. 2000;12:362–387. doi: 10.1177/089826430001200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss MS, Braunschweig H, Rubinstein RL. Terminal care for nursing home residents with dementia. Alzheimers Care Q. 2002;3:233–246. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson KA, Ewen HH. Death in the nursing home: an examination of grief and well-being in nursing assistants. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2011;4:87–94. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20100702-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rickerson EM, Somers C, Allen CM, et al. How well are we caring for caregivers? Prevalence of grief-related symptoms and need for bereavement support among long-term care staff. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson KA. Grief experiences of CNAs: relationships with burnout and turnover. J Gerontol Nurse. 2008;34:42–49. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20080101-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herber OR, Johnston BM. The role of healthcare support workers in providing palliative and end-of-life care in the community: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Care Community. 2013;21:225–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss MS, Moss SZ. Nursing home staff reactions to resident deaths. In: Doka KJ, editor. Disenfranchised grief: New directions, challenges, and strategies for practice. Research Press; Champaign, IL: 2002. pp. 197–216. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hebert RS, Dang Q, Schulz R. Preparedness for the death of a loved one and mental health in bereaved caregivers of patients with dementia: Findings from the REACH study. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:683–693. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barry LC, Kasl SV, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric disorders among bereaved persons: the role of perceived circumstances of death and preparedness for death. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:447–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hebert RS, Schulz R, Copeland VC, Arnold RM. Preparing family caregivers for death and bereavement. insights from caregivers of terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hebert RS, Prigerson H, Schulz R, Arnold RM. Preparing caregivers for the death of a loved one: a theoretical framework and suggestions for future research. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1164–1171. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz R, Boerner K, Shear K, Zhang S, Gitlin LN. Predictors of complicated grief among dementia caregivers: a prospective study of bereavement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:650–658. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203178.44894.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boerner K, Schulz R, Horowitz A. Positive aspects of caregiving and adaptation to bereavement. Psychol Aging. 2004;19:668–675. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faschingbauer TR, Zisook S, DeVaul RA. The Texas Revised Inventory of Grief. In: Zisook S, editor. Biopsychosocial aspects of bereavement. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1987. pp. 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson GM, Shaffer DR. Relationship quality and potentially harmful behaviors by spousal caregivers: how we were then, how we are now. The Family Relationships in Late Life Project. Psychol Aging. 2001;16:217–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wisniewski SR, Belle SH, Coon DW, et al. The Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health (REACH): project design and baseline characteristics. Psychol Aging. 2003;18:375–384. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castle NG. The influence of consistent assignment on nursing home deficiency citations. Gerontologist. 2011;51:750–760. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carmack B. Balancing engagement and detachment in caregiving. J Nurs Scholarsh. 1997;29:139–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1997.tb01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson SA, Daley BJ. Attachment/detachment: forces influencing care of the dying in long-term care. J Palliat Med. 1998;1:21–34. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1998.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370:1960–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]