Abstract

Clinical studies have shown that metabolic syndrome (MetS) is associated with increased risk of developing periodontitis. However, the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown. Since it is known that lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–activated toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathways play a crucial role in periodontitis, we hypothesized that MetS enhances LPS-induced periodontal inflammation and alveolar bone loss. In this study, we induced MetS in C57BL/6 mice by feeding them high-fat diet (HFD), and we induced periodontitis by periodontal injection of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans LPS. We found that mice fed a HFD had significantly increased body weight, plasma lipids, insulin, and insulin resistance when compared with mice fed regular chow, indicating that the mice developed MetS. We also found that a HFD markedly increased LPS-induced alveolar bone loss, osteoclastogenesis, and inflammatory infiltration. Analysis of gene expression in periodontal tissue revealed that HFD and LPS injection cooperatively stimulated expression of cytokines that are known to be involved in periodontal tissue inflammation and osteoclastogenesis—such as interleukin 6, monocyte-chemotactic protein 1, receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor. To further understand the potential mechanisms involved in MetS-boosted tissue inflammation, our in vitro studies showed that palmitic acid—the most abundant saturated fatty acid (SFA) and the major SFA in the HFD used in our animal study—potently enhanced LPS-induced proinflammatory gene expression in macrophages. In sum, this study demonstrated that MetS was associated with increased periodontal inflammation and alveolar bone loss in an LPS-induced periodontitis animal model. This study also suggests that SFA palmitic acid may play an important role in MetS-associated periodontitis by enhancing LPS-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines in macrophages.

Keywords: lipopolysaccharide, palmitic acid, high-fat diet, osteoclast, cytokines, gene expression

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of cardiovascular risk factors, including abdominal obesity, atherogenic dyslipidemia, hypertension, insulin resistance, and proinflammatory and prothrombotic states (Grundy et al. 2004). MetS is considered prediabetes since it may not include hyperglycemia but is commonly associated with insulin resistance and highly predictive of new-onset type 2 diabetes (Grundy et al. 2004; Grundy 2012).

Periodontitis is a primarily bacterial infection of the supporting structures of teeth, characterized by tissue inflammation and destruction that eventually lead to tooth loss (Beck et al. 1996; Offenbacher 1996). It has been well established that diabetes is an independent risk factor for periodontitis (Lalla et al. 2000). In addition, recent clinical studies have provided evidence that MetS is associated with an increased risk of periodontitis (Nibali et al. 2013). Furthermore, studies have linked obesity with periodontitis (Suvan et al. 2011; Krejci and Bissada 2013), suggesting that disorders of lipid metabolism, present in both MetS and obesity, may increase the risk of developing periodontitis. However, the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown.

A few studies have shown that MetS or obesity is associated with periodontitis in animal models. Our laboratory employed Zucker fat rats—a well-established model of MetS (Fellmann et al. 2013)—and induced periodontitis by periodontal injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) isolated from Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, a periodontal pathogen (Hyvarinen et al. 2014). We demonstrated that LPS-induced alveolar bone loss in Zucker fat rats was more severe than that in control lean rats (Jin, Machado, et al. 2014). Interestingly, Mizutani et al. (2014) showed that the gingival tissue had increased activities of protein kinase C isoforms and expression of p65 subunit of nuclear factor kappa-B in Zucker fat rats without induction of periodontitis, suggesting that MetS per se is associated with a hyperinflammatory state in gingival tissue that may contribute to MetS-related periodontitis. Furthermore, Amar et al. (2007) employed a mouse model with high-fat diet (HFD)–induced obesity (DIO) and Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis)–induced periodontitis, demonstrating that DIO was associated with a higher degree of alveolar bone loss. Interestingly, this study also showed that DIO was associated with an increased level of P. gingivalis in gingival tissue and a blunted systemic inflammatory response. However, the mechanism for DIO-related alveolar bone loss remains unclear since the study did not elucidate periodontal inflammation in response to P. gingivalis.

In the current study, we hypothesized that MetS enhances LPS-induced periodontal inflammation and alveolar bone loss. To test our hypothesis, we employed a mouse model with DIO and induced periodontitis by periodontal injection of A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS. We demonstrated that mice with DIO had major features of MetS, including obesity, dyslipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance. We also showed that the mice with MetS had a markedly increased alveolar bone loss, osteoclastogenesis, and inflammatory infiltration induced by LPS injection, as compared with the control mice without MetS.

Materials and Methods

Animal Treatments

Six-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were purchased (Taconic Farms, Hudson, NY, USA) and fed regular mouse chow (D12450B; n = 14) or a HFD (D12492; n = 14; Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, USA) for 16 wk. The mice were housed with a 12-h cycle of light and dark and had free access to tap water and food. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical University of South Carolina approved all experimental protocols. During the last 4 wk of regular chow or HFD feeding, 14 mice (7 fed regular chow and 7 fed a HFD) were injected with LPS (20 µg per mouse) isolated from A. actinomycetemcomitans (strain Y4, serotype B; Yu et al. 2011) through both the left and right sides of the palatal gingiva between the maxillary first and second molars, 3 times per week as described previously (Rogers et al. 2007; Jin, Zhang, et al. 2014). For control, 14 mice (7 fed regular chow and 7 fed a HFD) were injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the vehicle for LPS.

Metabolic Measurements

See the Appendix.

Micro–computed Tomography and Bone Volume Fraction Analysis

See the Appendix.

Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase Staining and Quantification of Osteoclasts

Formalin-fixed maxillae were decalcified in a 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution for 4 wk at 4°C. The EDTA solution was changed 3 times per week. The maxillae were paraffin-embedded, and sagittal sections (7 µm) were prepared. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining was performed in tissue sections via a leukocyte acid phosphatase kit (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The tissue sections were counterstained with hematoxylin after TRAP staining. Active osteoclasts were defined as multinucleated TRAP-positive cells in contact with bone surface. TRAP-positive osteoclasts under the first and second molars on the surface of alveolar bone were counted.

Histologic Tissue Processing and Pathologic Evaluation

For pathologic evaluation, the above tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Tissue inflammation and bone resorption were evaluated according to the following criteria: 0 = within normal limits; 1 = focal some leukocyte infiltration, no significant bone resorption; 2 = moderate leukocyte infiltration with mild bone resorption; 3 = severe leukocyte infiltration with moderate bone resorption; and 4 = severe leukocyte infiltration with extensive bone resorption (Jin, Machado, et al. 2014).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

See the Appendix.

Culture of Bone Marrow–derived Macrophages

See the Appendix.

Palmitic Acid Preparation

To prepare palmitic acid (PA) for cell treatments, PA was dissolved in 0.1N NaOH and 70% ethanol at 70°C to make 50 mM. The solution was kept at 55°C for 10 min, mixed, and brought to room temperature.

ELISA

Interleukin 6 (IL-6) in medium was quantified via a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA).

Polymerase Chain Reaction Arrays

Duplicate samples of RNA used for real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were combined for PCR array analysis. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from RNA via the RT2 First Strand Kit (SuperArray Bioscience Corp., Frederick, MD, USA). Mouse toll-like receptor (TLR) pathway-focused PCR arrays (SuperArray Bioscience Corp.) were performed with the 2× SuperArray RT2 qPCR Master Mix and the first-strand cDNA by following the instructions from the manufacturer.

Statistic Analysis

GraphPad Instat 3.1a software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. For data with normal distribution, Student’s t test was used for comparison of means between 2 groups, and values were expressed as mean ± SD. For data without normal distribution, nonparametric analysis based on the Mann-Whitney test was performed to determine the statistical significance of differences between 2 experimental groups. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

HFD Induces MetS

After mice were fed a HFD for 16 wk, the metabolic parameters were determined (see Appendix Table 2). The mice fed a HFD were 61% heavier than the mice fed regular chow. The plasma fasting glucose levels in mice fed a HFD did not increase significantly versus that in the control mice. Strikingly, the fasting insulin level and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance in mice fed a HFD were increased by 7- and 8-fold, respectively, against those in the control mice, suggesting that a HFD induced a strong insulin resistance. The plasma lipids—including cholesterol, triglycerides, and free fatty acids—in mice fed a HFD were all significantly increased versus those in the control mice. Taken together, these metabolic data indicate that mice fed a HFD developed MetS, as they had obesity, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia.

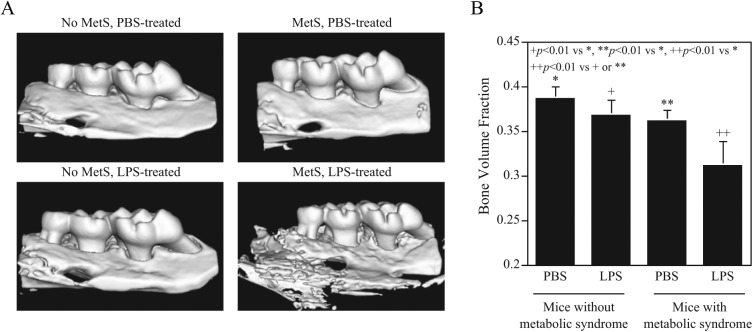

HFD Exacerbates LPS-induced Alveolar Bone Loss

After periodontal injection of LPS for 4 wk, the mouse maxillae were scanned by micro–computed tomography to reveal alveolar bone and quantify BVF. Results (Fig. 1) showed that LPS injection in mice fed regular chow induced alveolar bone loss by 4.4% (0.367 vs. 0.386, P < 0.01), while HFD feeding alone induced alveolar bone loss by 5.9% (0.361 vs. 0.386, P < 0.01). Strikingly, the combination of LPS injection and HFD feeding led to markedly increased bone loss, by 19.0% (0.311 vs. 0.386, P < 0.01), revealing a synergy between HFD feeding and LPS injection on alveolar bone loss.

Figure 1.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is associated with increased alveolar bone loss induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). C57BL/6 mice, with or without MetS, were injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or LPS in periodontal tissue to induce periodontitis as described in Methods. After the treatment, the maxillae were scanned by micro–computed tomography (A), and bone volume fractions were quantified (B). The data are presented as means ± SD (n = 7).

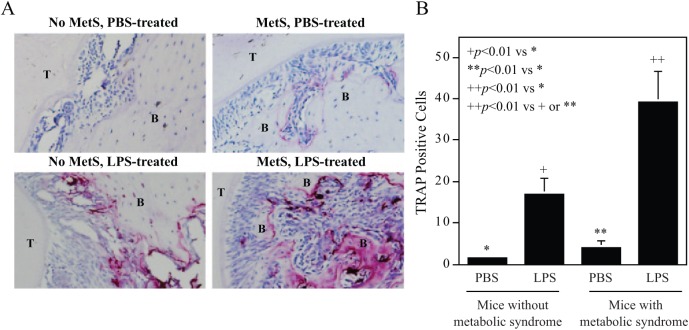

HFD Enhances LPS-induced Osteoclastogenesis

To further elucidate how a HFD exacerbates LPS-induced alveolar bone loss, we performed TRAP staining on tissue sections of the maxillae to detect osteoclasts. Results (Fig. 2) showed that LPS injection induced osteoclastogenesis in mice fed regular chow, while HFD feeding alone also slightly induced osteoclastogenesis. Impressively, the combination of LPS injection and HFD feeding exerted a strong synergy on osteoclastogenesis.

Figure 2.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is associated with increased osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). C57BL/6 mice, with or without MetS, were injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or LPS in periodontal tissue to induce periodontitis (as described in Methods). After the maxillae were examined by micro–computed tomography (as shown in Figure 1), they were decalcified and sectioned. Tartrate-resistance acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining to detect osteoclasts was performed on the tissue sections. Representative tissue sections from 4 groups were shown (A), and multinucleated TRAP-positive osteoclasts were quantified (B). The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 7). B, alveolar bone; T, tooth.

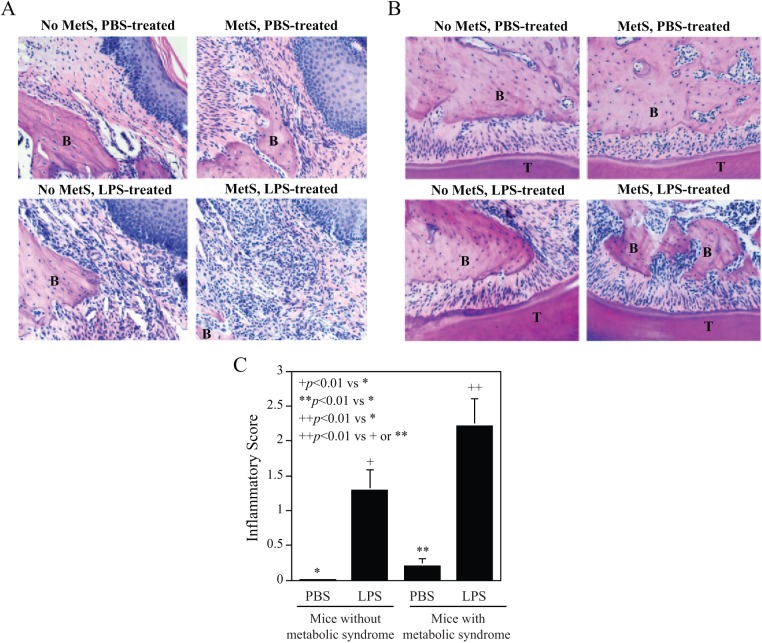

HFD Enhances LPS-induced Tissue Inflammation and Bone Resorption

Histologic analysis of maxillae was conducted to determine the effect of LPS and a HFD on periodontal inflammation and bone resorption. We focused on both the subepithelial gingival tissue (Fig. 3A) and the periodontal ligament tissue (Fig. 3B) adjacent to the sites of LPS or PBS injection. Results showed that LPS injection in mice fed regular chow led to a marked increase in leukocyte infiltration and alveolar bone resorption, while HFD feeding alone also increased leukocyte infiltration and alveolar bone resorption. Consistent with the above findings on alveolar bone loss and osteoclastogenesis, the combination of LPS injection and HFD feeding had a synergistic effect on tissue inflammation and alveolar bone resorption. Pathologic analysis of tissue inflammation intensity showed that while LPS injection or HFD feeding alone increased inflammatory scores, the combination of LPS injection and HFD feeding led to a further increase in inflammatory scores (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is associated with increased leukocyte infiltration and bone resorption induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). In addition to tartrate-resistance acid phosphatase staining, the tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Furthermore, histologic evaluation was performed of leukocyte infiltration and bone resorption in subepithelial gingival (A) and periodontal ligament (B) tissue after treatment with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or LPS in mice, with or without MetS. Photomicrographs were taken at 200× magnification. The inflammatory scores for leukocyte infiltration and bone resorption were determined (C) according to the criteria described in Methods. The data are presented as means ± SD (n = 7). B, alveolar bone; T, tooth.

HFD Enhances LPS-stimulated Cytokine Expression

Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and monocyte-chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1) play a crucial role in periodontitis (Hanazawa et al. 1993; Javed et al. 2012). In addition, receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) are key players to increase osteoclastogenesis and alveolar bone resorption (Taubman et al. 2005; Lee et al. 2009). To understand how a HFD augments LPS-induced alveolar bone resorption, we determined the effect of HFD feeding and/or LPS injection on the expression of IL-6, MCP-1, M-CSF, and RANKL in the periodontal tissue. Results (Table) showed that LPS injection in mice fed regular chow or HFD feeding alone without LPS injection stimulated the expression of the cytokines. Interestingly, the combination of LPS injection and HFD feeding stimulated the expression of the cytokines to higher levels in a cooperative manner.

Table.

Mice With Metabolic Syndrome Have Increased Periodontal Expression of Inflammatory Cytokines.

| Mice | IL-6 | M-CSF | MCP-1 | RANKL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-MetS | ||||

| With PBS | 0.18 (0.10, 1.59) | 0.69 (0.01, 1.68) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.23) | 1.38 (0.27, 3.30) |

| With LPS | 0.82 (0.10, 1.98)a | 1.15 (0.40, 1.85)a | 0.11 (0.03, 0.37)a | 2.52 (0.55, 3.66)a |

| MetS | ||||

| With PBS | 0.73 (0.26, 1.96)b | 1.59 (0.92, 2.99)b | 0.42 (0.02, 1.28)b | 2.10 (0.74, 4.74)b |

| With LPS | 1.09 (0.39, 2.61)c | 2.69 (1.57, 5.52)c | 1.20 (0.58, 4.58)c | 3.43 (1.19, 7.23)c |

Data are median (minimum, maximum) (n = 7). Mann-Whitney test was performed for statistical analysis.

IL-6, interleukin 6; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand.

P < 0.01 vs. non-MetS mice with PBS injection.

P < 0.01 vs. non-MetS mice with PBS injection.

P < 0.01 vs. non-MetS mice with PBS injection. P < 0.05 vs. non-MetS mice with LPS. P < 0.05 vs. MetS mice with PBS.

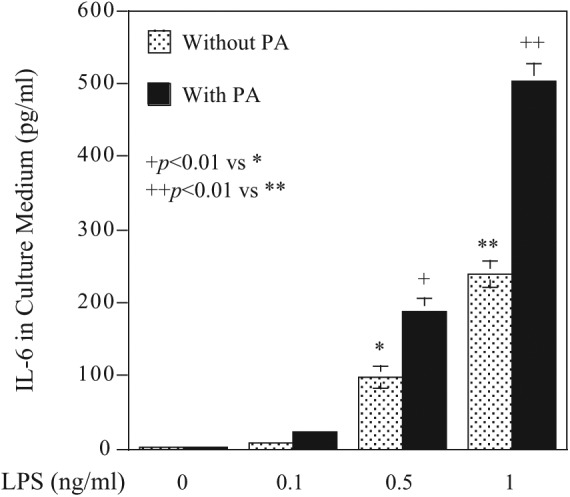

To understand how HFD feeding enhances the effect of LPS on periodontitis, we hypothesized that PA, the most abundant saturated fatty acid, may play a role in periodontitis since PA is an important factor in MetS-related insulin resistance and systemic inflammation (Maloney et al. 2009; Coll et al. 2010; Igoillo-Esteve et al. 2010) and the HFD given to mice in our study had a high content of PA. In this study, we selected macrophages because macrophage-mediated inflammatory response plays a crucial role in development of periodontal disease (Charon et al. 1981; Shapira et al. 1996; Jagannathan et al. 2014). Results showed that LPS induced IL-6 secretion from bone marrow–derived macrophages, while PA had no effect, although it did enhance the stimulatory effect of LPS by 2-fold (Fig. 4). To further assess the effect of PA on LPS-triggered inflammatory response, we employed a TLR pathway–focused gene array to quantify gene expression in bone marrow–derived macrophages. Results (Appendix Table 3) showed that while LPS stimulated a number of cytokines, PA also increased expression of some cytokines, such as IL-1α, CXCL10, and CD86. Strikingly, the combination of LPS and PA stimulated a large number of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1α, IL-1β, CXCL10, CD86, CSF2, MCP-1, TLR2, TNFα, CD14, and IL-6.

Figure 4.

Palmitic acid (PA) enhances lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–stimulated interleukin 6 (IL-6) secretion from bone marrow–derived macrophages, which were treated with different concentrations of LPS, 100 µM of PA, or both LPS and PA for 24 h. After the treatment, IL-6 in culture medium was quantified via ELISA. The data are presented as means ± SD of 1 of 3 experiments with similar results.

Discussion

The major finding from this study is that periodontal LPS injection in MetS mice led to a marked increase in alveolar bone loss, osteoclastogenesis, and bone resorption, when compared with mice without MetS. This finding is important since it demonstrated for the first time that local LPS treatment and systemic MetS had a robust cooperation to stimulate a hyperinflammatory response in periodontal tissue, leading to remarkable alveolar bone loss. This finding replicates the clinical observation on the association of MetS with periodontitis (Nibali et al. 2013) and rationalizes this model in studies of MetS-related periodontitis. To understand how HFD-induced MetS boosts alveolar bone loss, we assessed the inflammatory infiltration in periodontal tissue and expression of inflammatory cytokines. Histologic analysis (Fig. 3) and a gene expression study (Table) showed that LPS-induced inflammation and gene expression in periodontal tissue were remarkably augmented in mice with MetS as compared with mice without MetS, strongly indicating that an exaggerated local inflammation is responsible for increased alveolar bone loss. Previously, Amar et al. (2007) reported that HFD was associated with a higher degree of alveolar bone loss. However, it remains unclear how HFD affects periodontal inflammation. In the current study, our histologic and gene expression data clearly indicated that a HFD boosted periodontal inflammation.

Our metabolic data indicate that mice fed a 4-mo HFD developed MetS, as they had increased body weight, plasma lipids (including cholesterol, triglycerides and free fatty acids), serum insulin level, and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance. Gamliel-Lazarovich et al. (2013) showed that MetS induced by HFD feeding in C57BL/6 mice is associated with systemic hypertension. The most impressive changes of the metabolic abnormalities observed in our study were the remarkable increases of fast plasma insulin and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance. Clearly, a HFD induced a strong insulin resistance—a hallmark of MetS (Ruderman et al. 2013). The metabolic data also showed that the mice fed a HFD had increased free fatty acids that are known to play an important role in insulin resistance by inhibiting insulin signaling in adipocytes and skeletal muscle (Kraegen and Cooney 2008; Capurso C and Capurso A 2012). Moreover, the mice fed a HFD did not have a significant increase in fasting glucose, which is in agreement with the previous report on this mouse model (Amar et al. 2007). It is noteworthy that although the HFD induces most of the symptoms of human MetS, including insulin resistance, in our mouse model, it is unlikely that a HFD induces hyperglycemia, since diets causing MetS in human are more complex than the rodent HFD and since it may also take much longer for a HFD to induce hyperglycemia in mice. Given the absence of hyperglycemia in the mice, pathologic factors other than hyperglycemia may play important role in MetS-related periodontitis.

In this study, we employed a rodent model in which periodontitis is induced by periodontal injection of A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS (Rogers et al. 2007). This animal model allowed us to test our hypothesis that MetS enhances LPS-induced periodontal inflammation and alveolar bone loss in vivo. However, note that this model is not exactly a periodontal disease model relevant to human periodontitis, since human periodontitis is caused by multiple periodontopathogens (Tanner et al. 1998). This is the main limitation of the study, which should be considered hypothesis generating.

A. actinomycetemcomitans has been considered a periodontal pathogen involved in aggressive periodontitis. However, this notion has been challenged by a study indicating that mixed bacteria of the red and orange complexes, which do not include A. actinomycetemcomitans, were associated with aggressive periodontitis (Kononen and Muller 2014). Also, A. actinomycetemcomitans was shown to be involved in chronic periodontitis, as Cortelli et al. (2010) reported that A. actinomycetemcomitans was detected in 18.37% of Brazilians with chronic periodontitis (n = 555). Furthermore, a recent clinical study showed that systemic exposure to A. actinomycetemcomitans was associated with MetS in Finnish patients aged 45 to 74 y (odds ratio, 1.42; P < 0.009) and that MetS was associated with more than 4 missing teeth (odds ratio, 1.69; P < 0.001) (Hyvarinen et al. 2014).

Using bone volume quantification based on micro–computed tomography, we demonstrated that even in the absence of periodontal LPS treatment, MetS was associated with a significantly decreased bone volume fraction (0.361 vs 0.386, P < 0.01), suggesting that MetS per se as a comorbidity of periodontitis exerts a negative impact on alveolar bone volume. Intriguingly, our data showed that the degree of alveolar bone loss in mice with MetS and PBS injection was similar to that in control mice with LPS injection (Fig. 1), but the degrees of osteoclastogenesis and inflammatory infiltration in mice with MetS and PBS injection were much less than those in non-MetS mice with LPS injection (Figs. 2 and 3). To reconcile this discrepancy, note that the mice were injected with LPS for only 4 wk but fed a HFD for 4 mo. Although the osteoclastogenesis and inflammatory infiltration in response to HFD alone appear less robust than those in response to LPS injection, a much longer period of HFD feeding is likely to result in a substantial bone resorption.

It is surprising to find that a HFD for 4 mo led to a significant alveolar bone loss, equivalent to that induced by periodontal injection of LPS for 4 wk in mice fed normal chow. This finding suggests that C57BL/6 mice are more susceptible to metabolic disorders than humans in developing periodontitis. Actually, ligature-induced experimental periodontitis in rodents takes only weeks, but developing periodontitis in human takes years. These findings also suggest that the defense mechanisms against periodontitis in humans are much more sophisticated and advanced than those in murine models.

Interestingly, rheumatoid arthritis, another comorbidity of periodontitis, is also associated with spontaneous alveolar bone loss in a C57BL/6 mouse model for arthritis without bacterial inoculation (Queiroz-Junior et al. 2011). In that study, which explored the mechanisms of rheumatoid arthritis-associated periodontitis, it was suggested that arthritis-dependent release of proinflammatory cytokines played a critical role in arthritis-related periodontal disease. Similarly, our results (Table) showed that the mice with MetS had increased periodontal expression of IL-6, M-CSF, MCP-1, and RANKL when compared with the control mice, indicating that, like rheumatoid arthritis, MetS induces a hyperinflammatory state that may contribute to alveolar bone loss.

In our studies to elucidate the potential mechanisms involved in MetS-related periodontitis, we focused on saturated fatty acids (SFAs), since a clinical study with a large number of patients (n = 1,754) showed that high dietary saturated fat (>15.5% energy) exacerbated MetS risk (odds ratio, 2.35; P = 0.005; Phillips et al. 2012). PA, as the most abundant SFA, has been shown to play an important role in SFA-induced insulin resistance and inflammation (Maloney et al. 2009; Coll et al. 2010; Igoillo-Esteve et al. 2010). Furthermore, the HFD that we used in the current study was enriched with PA. We employed bone marrow–derived macrophages to demonstrate that PA augmented the effect of LPS on the expression of a number of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-1α, IL-1β, CXCL10, MCP-1, and CSF2. Interestingly, PA also enhanced the effect of LPS on the expression of TLR-related signaling molecules, such as CD14 and TLR2, suggesting that it amplifies TLR-mediated inflammatory signaling triggered by LPS.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated for the first time that MetS is associated with increased periodontal inflammation and alveolar bone loss induced by LPS in an animal model. It also showed that PA and LPS had a cooperative effect on the expression of inflammatory cytokines in bone marrow–derived macrophages, suggesting a potential role of PA in MetS-related periodontitis.

Author Contributions

Y. Li, Z. Lu, X. Zhang, contributed to data acquisition and analysis, drafted the manuscript; H. Yu, contributed to data acquisition and analysis, critically revised the manuscript; K.L. Kirkwood, contributed to conception, critically revised the manuscript; M.F. Lopes-Virella, contributed to data interpretation; drafted the manuscript; Y. Huang, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by grant DE016353 from the National Institutes of Health and grant 5I01BX000854 from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development (to Y.H.). This study utilized the facilities and resources of the Medical University of South Carolina Center for Oral Health Research, which is partially supported by grant P30GM103331 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

A supplemental appendix to this article is published electronically only at http://jdr.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- Amar S, Zhou Q, Shaik-Dasthagirisaheb Y, Leeman S. 2007. Diet-induced obesity in mice causes changes in immune responses and bone loss manifested by bacterial challenge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104(51):20466–20471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck J, Garcia R, Heiss G, Vokonas PS, Offenbacher S. 1996. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 67(10 Suppl):1123–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capurso C, Capurso A. 2012. From excess adiposity to insulin resistance: the role of free fatty acids. Vascul Pharmacol. 57(2–4):91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charon J, Toto PD, Gargiulo AW. 1981. Activated macrophages in human periodontitis. J Periodontol. 52(6):328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll T, Palomer X, Blanco-Vaca F, Escolà-Gil JC, Sánchez RM, Laguna JC, Vázquez-Carrera M. 2010. Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibition exacerbates palmitate-induced inflammation and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle cells. Endocrinology. 151(2):537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortelli JR, Roman-Torres CV, Aquino DR, Franco GC, Costa FO, Cortelli SC. 2010. Occurrence of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans in Brazilians with chronic periodontitis. Braz Oral Res. 24(2):217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellmann L, Nascimento AR, Tibiriça E, Bousquet P. 2013. Murine models for pharmacological studies of the metabolic syndrome. Pharmacol Ther. 137(3):331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamliel-Lazarovich A, Raz-Pasteur A, Coleman R, Keidar S. 2013. The effects of aldosterone on diet-induced fatty liver formation in male C57BL/6 mice: comparison of adrenalectomy and mineralocorticoid receptor blocker. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 25(9):1086–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy SM. 2012. Pre-diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 59(7):635–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr, Lenfant C; American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 2004. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 109(3):433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanazawa S, Kawata Y, Takeshita A, Kumada H, Okithu M, Tanaka S, Yamamoto Y, Masuda T, Umemoto T, Kitano S. 1993. Expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) in adult periodontal disease: increased monocyte chemotactic activity in crevicular fluids and induction of MCP-1 expression in gingival tissues. Infect Immun. 61(12):5219–5224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyvarinen K, Salminen A, Salomaa V, Pussinen PJ. 2014. Systemic exposure to a common periodontal pathogen and missing teeth are associated with metabolic syndrome. Acta Diabetol [Epub ahead of print 5 May 2014] in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igoillo-Esteve M, Marselli L, Cunha DA, Ladrière L, Ortis F, Grieco FA, Dotta F, Weir GC, Marchetti P, Eizirik DL, et al. 2010. Palmitate induces a pro-inflammatory response in human pancreatic islets that mimics CCL2 expression by beta cells in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 53(7):1395–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagannathan R, Lavu V, Rao SR. 2014. Comparison of the proportion of non-classic (CD14+CD16+) monocytes/macrophages in peripheral blood and gingiva of healthy individuals and patients with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 85(6):852–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javed F, Al-Askar M, Al-Hezaimi K. 2012. Cytokine profile in the gingival crevicular fluid of periodontitis patients with and without type 2 diabetes: a literature review. J Periodontol. 83(2):156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Machado ER, Yu H, Zhang X, Lu Z, Li Y, Lopes-Virella MF, Kirkwood KL, Huang Y. 2014. Simvastatin inhibits LPS-induced alveolar bone loss during metabolic syndrome. J Dent Res. 93(3):294–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Zhang X, Lu Z, Li Y, Lopes-Virella MF, Yu H, Haycraft CJ, Li Q, Kirkwood KL, Huang Y. 2014. Simvastatin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced osteoclastogenesis and reduces alveolar bone loss in experimental periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 49(4):518–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kononen E, Muller HP. 2014. Microbiology of aggressive periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 65(1):46–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraegen EW, Cooney GJ. 2008. Free fatty acids and skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Curr Opin Lipidol. 19(3):235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci CB, Bissada NF. 2013. Obesity and periodontitis: a link. Gen Dent. 61(1):60–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalla E, Lamster IB, Drury S, Fu C, Schmidt AM. 2000. Hyperglycemia, glycoxidation and receptor for advanced glycation endproducts: potential mechanisms underlying diabetic complications, including diabetes-associated periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 23:50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Kim HS, Yeon JT, Choi SW, Chun CH, Kwak HB, Oh J. 2009. GM-CSF regulates fusion of mononuclear osteoclasts into bone-resorbing osteoclasts by activating the Ras/ERK pathway. J Immunol. 183(5):3390–3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney E, Sweet IR, Hockenbery DM, Pham M, Rizzo NO, Tateya S, Handa P, Schwartz MW, Kim F. 2009. Activation of NF-kappaB by palmitate in endothelial cells: a key role for NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide in response to TLR4 activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 29(9):1370–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani K, Park K, Mima A, Katagiri S, King GL. 2014. Obesity-associated gingival vascular inflammation and insulin resistance. J Dent Res. 93(6):596–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibali L, Tatarakis N, Needleman I, Tu YK, D’Aiuto F, Rizzo M, Donos N. 2013. Clinical review: association between metabolic syndrome and periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 98(3):913–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offenbacher S. 1996. Periodontal diseases: pathogenesis. Ann Periodontol. 1(1):821–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CM, Goumidi L, Bertrais S, Field MR, McManus R, Hercberg S, Lairon D, Planells R, Roche HM. 2012. Dietary saturated fat, gender and genetic variation at the TCF7L2 locus predict the development of metabolic syndrome. J Nutr Biochem. 23(3):239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz-Junior CM, Madeira MF, Coelho FM, Costa VV, Bessoni RL, Sousa LF, Garlet GP, Souza Dda G, Teixeira MM, Silva TA. 2011. Experimental arthritis triggers periodontal disease in mice: involvement of TNF-alpha and the oral microbiota. J Immunol. 187(7):3821–3830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JE, Li F, Coatney DD, Rossa C, Bronson P, Krieder JM, Giannobile WV, Kirkwood KL. 2007. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans lipopolysaccharide-mediated experimental bone loss model for aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 78(3):550–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruderman NB, Carling D, Prentki M, Cacicedo JM. 2013. AMPK, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 123(7):2764–2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira L, Soskolne WA, Van Dyke TE. 1996. Prostaglandin E2 secretion, cell maturation, and CD14 expression by monocyte-derived macrophages from localized juvenile periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 67(3):224–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvan J, D’Aiuto F, Moles DR, Petrie A, Donos N. 2011. Association between overweight/obesity and periodontitis in adults: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 12(5):e381–e404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner A, Maiden MF, Macuch PJ, Murray LL, Kent RL., Jr. 1998. Microbiota of health, gingivitis, and initial periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 25(2):85–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubman MA, Valverde P, Han X, Kawai T. 2005. Immune response: the key to bone resorption in periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 76(11 Suppl):2033–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Li Q, Herbert B, Zinna R, Martin K, Junior CR, Kirkwood KL. 2011. Anti-inflammatory effect of MAPK phosphatase-1 local gene transfer in inflammatory bone loss. Gene Ther. 18(4):344–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.