Abstract

The prevalence of resistant genes against β-lactams in 119 Aeromonas strains was determined. A large number (99.2%) of the present fish strains were resistant to one or more β- lactams including ceftiofur, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ampicillin, piperacillin and cefpodoxime. Among antibiotic resistance phenotypes, the simultaneous resistance to all β-lactams occurred in 25.2% (n=30) of all strains, which consisted of 18 strains of A. dhakensis, 8 strains of A. caviae, 2 strains of A. hydrophila and only one strain of A. veronii. For exploring genetic background of the antibiotic resistances, multiple PCR assays were subjected to detect β-lactamase-encoding genes, blaTEM, blaOXA-B and blaCTX-M. In the results, the blaTEM-1 gene was harbored in all strains, whereas only 3 strains harbored blaOXA gene. In the case of blaCTX-M gene, the gene was detected in 21.0% (25 out of 119) of all strains, which countered with 80% (20 out of 25) of A. dhakensis, 8% (2 out of 25) of A. caviae and 12% (3 out of 25) of A. hydrophila. In addition, most of the blaCTX-M positive strains showed simultaneous resistance to all β-lactams (18 out of 30 strains). In sequence analysis for blaCTX-M genes detected, they were CTX-M group 1-encoding genes including blaCTX-M-33 from 3 eel strains of A. dhakensis. Therefore, A. dhakensis obtained from cultured fish could represent a reservoir for spreading genes encoding CTX-M group 1 enzymes and hence should be carefully monitored, especially for its potential risk to public health.

Keywords: Aeromonas aquariorum, Aeromonas dhakensis, aquaculture, β-lactams, blaCTX-M-1 group

Since Aeromonas dhakensis, formerly called A. aquariorum, was firstly detected in ornamental fish [13], the bacterium has been recognized in retrospective studies to be an important pathogenic species within the Aeromonas genus because of its high prevalence in human clinical strains [6, 15, 16, 20]. However, there is less information about the prevalence and characteristics of A. dhakensis in veterinary aquatic medicine than human medicine [11, 22].

Aeromonas spp. can produce various β-lactamases for conferring resistance to β-lactams. Amber class-B, -C and -D β-lactamases have been known to be chromosomally mediated β-lactamases in Aeromonas spp. [8, 12, 15, 20, 21]. Of these β-lactamases, cphA and its related genes encoding class-B β-lactamases have shown species-specific distributions. In the case of class-A β-lactamases, the previous studies have shown different prevalence for genes encoding TEM-type β-lactamases in Aeromonas spp. according to isolation sources [2, 3, 14, 15]. In contrast, CTX-M encoding genes have been identified in only three previous studies, which found A. caviae and/or A. hydrophila producing CTX-M-3 and CTX-M-15 β-lactamases [5, 12, 21]. In addition, another previous study did not detect blaCTX-M in a collection of human clinical A. dhakensis strains, whereas blaTEM and blaMOX genes were detected at high rates in the strains [15]. However, most previous studies aimed at detecting genetic backgrounds have employed very limited human clinical Aeromonas strains [15, 20, 21]. There is little information in the literature about the prevalence to β-lactamases-encoding genes in Aeromonas strains from aquaculture, which involves ecosystems that can include various global factors associated with selective and/or co-selective resistance to antibiotics.

The present study examined the resistance to β-lactams, amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AmC), piperacillin (PIP), ceftiofur (Tio) and cefpodoxime (Pod) in 119 strains from fish identified at the Aeromonas spp. level. To determine the prevalence to genetic determinants of resistance against β-lactams in fish clinical Aeromonas strains, a total of 119 strains of genus Aeromonas were evaluated for resistance to β-lactams. For exploring genetic background of the antibiotic resistances, multiple PCR assays were subjected to detect β-lactamase-encoding genes blaTEM, blaOXA-B and blaCTX-M.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Aeromonas strains: One hundred and nineteen strains were isolated from eel (n=70), pet fish (n=36) and koi carp (n=13). The eel strains were identified at the species level in our previous study by phylogenetic analysis using housekeeping genes (gyrB and rpoD) [11, 22]; they consisted of A. dhakensis (n=22), A. caviae (n=16), A. hydrophila (n=12), A. veronii (n=13), A. jandaei (n=4), A. media (n=2) and A. trota (n=1). The pet fish strains were identified as 5 Aeromonas spp.—A. veronii (n=31), A. allosaccharophila (n=2), A. dhakensis (n=1), A. hydrophila (n=1) and A. jandaei (n=1)—by phylogenetic analysis using gyrB gene sequences. The same identification method was applied for the koi carp strains, which consisted of A. hydrophila (n=8) and A. veronii (n=5). All strains were stored at −70°C using Cryocare Bacteria Preservers (Key Scientific Products, Stamford, TX, U.S.A.) until used for antimicrobial susceptibility tests and the detection of β-lactamase-encoding genes (blaTEM, blaOXA-B and blaCTX-M).

Antimicrobial susceptibility test: The antimicrobial susceptibility test (AST) was implemented using the VITEK 2 system with a veterinary susceptibility test card for Gram-negative bacteria (AST-GN38) (BioMérieux, Lyon, France), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The AST-GN38 card contains the following β-lactam antimicrobial agents as dehydrated substances at the indicated concentrations: ceftiofur (Tio)—1 and 2 µg/ml; amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (AmC)—4/2, 16/8 and 32/16 µg/ml; ampicillin (AM)—4, 8 and 32 µg/ml; cefpodoxime (Pod)—0.5, 1 and 4 µg/µl; and piperacillin (PIP)—4, 16, 32 and 64 µg/ml. The cutoff for resistance to each antimicrobial agent was designated as a resistance of greater than “intermediate” as defined by the criteria of the VITEK 2 system (version 04.01) based on the CLSI M100-S18 [19].

Detection of β-lactam resistance genes: The genomic DNA from strains was purified using the AccuPrep genomic extraction kit (Bioneer, Seoul, Korea). The β-lactamase-encoding genes, blaTEM, blaOXA-B and blaCTX-M, were subjected to PCR assays using the same primers and conditions as used in previous studies [8, 18]. The specificity for each PCR assay was demonstrated by direct sequencing analysis using the same primer sets for amplification on randomly selected PCR products. However, all PCR products for the blaCTX-M gene were sequenced at the Macrogen Service Center (Seoul, Korea). The generated sequences (277 to 704, based on the E. coli numbering of the blaCTX-M-3 gene; accession number AB231615) were aligned with those of well-known blaCTX-M genes (GenBank) according to CTX-M-1, −2, −8/25 and −9 groups. Genetic distances were determined using the Kimura two-parameter models, and neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees were constructed using the MEGA5 program, according to the previously reported method [22].

RESULTS

Table 1 shows proportion of resistance to five different β-lactams according to Aeromonas spp. AM and PIP showed resistance in 99.2% and 84.9% of all Aeromonas strains, respectively. Major species (A. veronii, A. hydrophila, A. caviae and A. dhakensis) revealed variable resistance levels to the other β-lactams. Of these β-lactams, the most resistant species to Pod was A. dhakensis (78.3%), followed by A. caviae (56.3%), A. hydrophila (9.5%) and A. veronii (4.1%). In addition, Pod resistant strains (27.7% of 119 strains) were simultaneously resistant to Tio. Tio resistant strains were observed in 52.9% of all strains including 21 strains of A. dhakensis (91.3%), 15 strains of A. caviae (93.8%), 10 strains of A. hydrophila (47.6%) and 12 strains of A. veronii (24.5%). In the case of AmC resistance, the prevalence was 61.3%. However, 89.0% (n=105) of AM-resistant strains (n=118) showed below intermediate resistance to AmC. When compared with Aeromonas spp., the decreased resistance was frequently observed in Aeromonas spp., except for A. caviae strains (Table 1).

Table 1. Resistance to five different β-lactams according to Aeromonas spp. used in the present study.

| Species | No. of resistant strain against | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM | AmC | PIP | Pod | Tio | |

| A. veronii (n=49) | 48 (1)* | 16 (16) | 38 (1) | 2 (2) | 12 (3) |

| A. dhakensis (n=23) | 23 (0) | 22 (20) | 22 (1) | 18 (7) | 21 (2) |

| A. hydrophila (n=21) | 21 (0) | 16 (14) | 17 (3) | 2 (2) | 10 (3) |

| A. caviae (n=16) | 16 (0) | 15 (6) | 14 (2) | 9 (4) | 15 (1) |

| A. jandaei (n=5) | 5 (0) | 2 (2) | 5 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| A. media (n=2) | 2 (0) | 2 (1) | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 2 (0) |

| A. allosaccharophila (n=2) | 2 (0) | 0 | 2 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| A. trota (n=1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Total (n=119) | 118 (2) | 73 (59) | 101 (8) | 33 (15) | 63 (10) |

* Parenthesized numbers indicate the number of strains with intermedate resistance.

Eleven different resistance patterns for β-lactams strains could be classified among all Aeromonas strains (Table 2). The predominant pattern was simultaneous resistance to all β-lactams (30 strains), followed by AM+PIP (29 strains), AM+AmC+PIP+Tio (23 strains), AM+AmC+PIP (12 strains) and only AM (9 strains). Of these patterns, simultaneous resistance to all β-lactams was the most frequently observed patterns for A. dhakensis.

Table 2. Prevalence of blaCTX-M-1 group in Aeromonas spp. according to resistance patterns of β-lactams.

| Resistance pattern | Detection of blaCTX-M-1 group in Aeromonas spp. (number of strains) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. dhakensis | A. caviae | A. hydrophila | A. veronii | A. jandaei | A. trota | A. allosaccharophila | A. media | Total | |

| None | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (1) |

| AM | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (9) |

| AM+AmC | 0 | 0 | 0 (3) | 0 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (5) |

| AM+PIP | 1 (1)* | 1 (1) | 0 (2) | 0 (20) | 0 (3) | 0 | 0 (2) | 0 | 2 (29) |

| AM+PIP+Tio | 0 | 0 | 0 (2) | 0 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (5) |

| AM+AmC+Tio | 1 (1) | 0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| AM+AmC+PIP | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 (5) | 0 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (12) |

| AM+AmC+PIP+Tio | 2 (2) | 0 (5) | 0 (6) | 0 (7) | 0 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 (1) | 2 (23) |

| AM+PIP+Pod+Tio | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (1) | 0 | 0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 (2) |

| AM+AmC+Pod+Tio | 0 | 0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (1) |

| AM+AmC+PIP+Pod+Tio | 15 #(18) | 1 (8) | 2 (2) | 0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (1) | 18 (30) |

| Total | 20 (23) | 2 (16) | 3 (21) | 0 (49) | 0 (5) | 0 (1) | 0 (2) | 0 (2) | 25 (119) |

*Nonparenthesized and parenthesized numbers indicate the number of strains carrying blaCTX-M-1 group genes and showing each grouped phenotypic antimicrobial resistance, respectively. #3 out of 15 strains harbored blaCTX-M-33 gene.

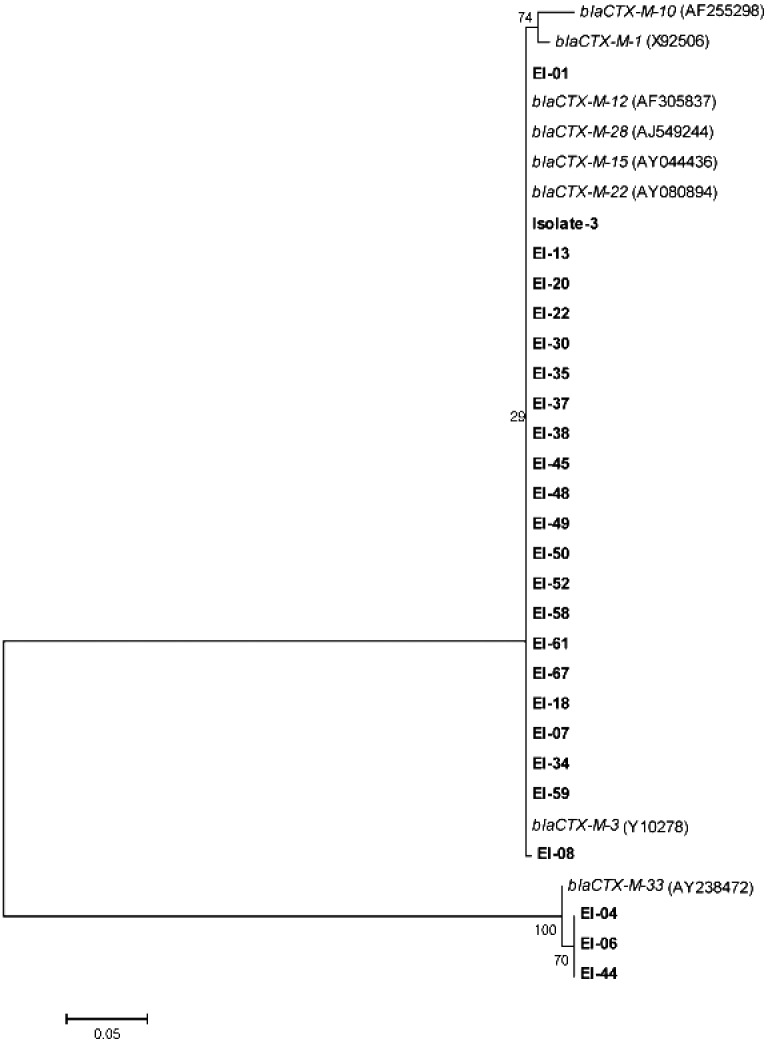

In investigation of genetic background to β-lactam resistances, all of the 119 strains harbored the blaTEM, and sequences of random PCR products had 100% identity to gene encoding TEM-1-type β-lactamase (GenBank No. KJ933392). The blaOXA gene was encountered in three strains: one A. allosaccharophila strain from pet fish and two A. caviae strains from eel. In the case of blaCTX-M gene, prevalence of the gene showed differences according to Aeromonas spp. and β-lactam resistance patterns (Table 2). The blaCTX-M genes were detected in 25 strains including 20 of A. dhakensis (19 eel strains and 1 pet fish strain), 2 eel strains of A. caviae and 3 eel strains of A. hydrophila. The PCR products were subjected to phylogenetic analysis by direct sequencing analysis using the primer set for blaCTX-M consensus [18]. The constructed phylogenetic tree showed that 25 blaCTX-M-positive strains were grouped with genes encoding CTX-M-1-group β-lactamases (Fig. 1). On the other hand, 3 eel strains of A. dhakensis were clustered with the gene encoding CTX-M-33 belonging to CTX-M-1 group. In addition, the genes were detected more among strains with resistance to all β-lactams (18/30) than among strains with other resistance patterns (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic identification of blaCTX-M-1-group gene sequences resulting from blaCTX-M-positive strains. The identification was performed by alignments with major sequences belonging to blaCTX-M-1-group genes in GenBank (accession numbers are within parentheses). The branch numbers refer to the percentage confidence as estimated by a bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replications.

DISCUSSION

The principal findings of the present study were twofold: (i)A. dhakensis could be a reservoir for genes encoding CTX-M-1-group β-lactamases in aquatic farming, and (ii) this is the first time that strains harboring blaCTX-M-33 gene—which encodes a variant of CTX-M-15 β-lactamases—have been isolated in worldwide veterinary aquatic medicine and the Korean microbiology community.

There are many doubts about the resistance of Aeromonas spp. to β-lactams in aquaculture farming [11, 14, 17]. In general, most of Aeromonas strains were resistant to aminopenicillins (e.g., amoxicillin and ampicillin), regardless of the isolation sources [9, 17]. The resistance was also shown in most strains used in the present study. Therefore, the results were agreed with the previous hypothesis, suggesting the production of naturally occurring aminopenicillinase in Aeromonas spp. [9]. In addition, all of the present strains harbored the blaTEM gene encoding TEM-type β-lactamase. When compared with the previous studies [1, 8, 17], a particularly interesting finding of the present study was the frequent occurrence of strains with resistance to ceftiofur and cefpodoxime. Neither of these antibiotics is approved for aquaculture use, but they are both approved for veterinary use. Although its occurrence is rare, a previous study found resistance to both antibiotics in Aeromonas spp. and Pseudomonas spp. from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) [1]. It is possible that the resistance to both antibiotics is a consequence of their off-label use in aquaculture and/or anthropogenic contamination from other farmed areas .

Cefpodoxime-resistant strains were found to be simultaneously resistant to ceftiofur. The prevalence of resistance to both antibiotics differed among the Aeromonas spp.: Ceftiofur resistance was more prevalent in A. caviae and A. dhakensis than in other Aeromonas spp., and A. dhakensis was the predominant species for cefpodoxime resistance. These results could be related to differences in genetic determinants related to antibiotic resistance among Aeromonas spp. Previous studies have also frequently detected genes encoding CTX-M-type cephalosporinase in ceftiofur-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from domestic animals [4, 10]. On the other hand, most of present strains were highly resistant to ampicillin, but they showed decreased resistance to combination of aminopenicillin and β-lactamase inhibitor. The behavior was observed in all Aeromonas spp. except A. caviae and was similar to extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing strain [4, 5, 7, 10]. In these aspects, the present study subjected all strains to PCR assays in order to detect blaCTX-M genes, followed by sequencing analysis of the amplicons. The CTX-M-1 group-encoding genes were frequently detected in strains with resistance to all β-lactams, with the pattern commonly observed in A. dhakensis strains of eel. This result supports our expectation of different genetic backgrounds to β-lactams antibiotic resistance in Aeromonas spp. A previous study found no blaCTX-M genes, but frequently detected blaMOX genes in 47 clinical strains of A. dhakensis with high prevalence of resistances to amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid [15]. Therefore, it is unclear whether the distribution of blaCTX-M-1-group genes is species specific, as for previous reports on cphA-related genes in Aeromonas spp. [20]. Based on differences in the isolation sources between the present and previous studies [15], A. dhakensis is regarded as having different genetic backgrounds under selective pressure according to antibiotic use. In addition, AmpC producer might be A. caviae strains with high resistance to ampicillin and ampicillin-clavulanic acid in the present study.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has investigated the prevalence of blaCTX-M genes in aquatic cultured fish species. In addition, this study is the first to isolate the strains harboring the blaCTX-M-33—a gene encoding a variant CTX-M-15 β-lactamases—from aquatic medicine after its first description in clinical E. coli isolates in Greece [7]. This study indicates that A. dhakensis could be the main carrier for spreading blaCTX-M-1-group genes in aquatic farming, hence, its risk to public health needs to be determined and to be monitored seriously.

Acknowledgments

his work was carried out with the support of “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development (Project title: Development of insect-based aquaculture feed ingredient, Project No: PJ010034)” Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea and “Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF)” Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (1101002330).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akinbowale O. L., Peng H., Grant P., Barton M. D.2007. Antibiotic and heavy metal resistance in motile aeromonads and pseudomonads from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) farms in Australia. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30: 177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balsalobre L. C., Dropa M., de Oliveira D. E., Lincopan N., Mamizuka E. M., Matté G. R., Matté M. H.2010. Presence of blaTEM-116 gene in environmental isolates of Aeromonas hydrophila and Aeromonas jandaei from Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 41: 718–719. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822010000300023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carvalho M. J., Martínez-Murcia A., Esteves A. C., Correia A., Saavedra M. J.2012. Phylogenetic diversity, antibiotic resistance and virulence traits of Aeromonas spp. from untreated waters for human consumption. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 159: 230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavaco L. M., Abatih E., Aarestrup F. M., Guardabassi L.2008. Selection and persistence of CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli in the intestinal flora of pigs treated with amoxicillin, ceftiofur, or cefquinome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52: 3612–3616. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00354-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen P. L., Ko W. C., Wu C. J.2012. Complexity of β-lactamases among clinical Aeromonas isolates and its clinical implications. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 45: 398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figueras M. J., Alperi A., Saavedra M. J., Ko W. C., Gonzalo N., Navarro M., Martínez-Murcia A. J.2009. Clinical relevance of the recently described species Aeromonas aquariorum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47: 3742–3746. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02216-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galani I., Souli M., Chryssouli Z., Giamarellou H.2007. Detection of CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-33, a novel variant of CTX-M-15, in clinical Escherichia coli isolates in Greece. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 29: 598–600. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henriques I. S., Fonseca F., Alves A., Saavedra M. J., Correia A.2006. Occurrence and diversity of integrons and β-lactamase genes among ampicillin-resistant isolates from estuarine waters. Res. Microbiol. 157: 938–947. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janda J. M., Abbott S. L.2010. The genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, pathogenicity, and infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23: 35–73. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jørgensen C. J., Cavaco L. M., Hasman H., Emborg H. D., Guardabassi L.2007. Occurrence of CTX-M-1-producing Escherichia coli in pigs treated with ceftiofur. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59: 1040–1042. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim D. C., You M. J., Kim B. S., Kim W. I., Yi S. W., Shin G. W.2014. Antibiotic and heavy-metal resistance in motile Aeromonas strains isolated from fish. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 8: 1793–1797. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maravić A., Skočibušić M., Samanić I., Fredotović Z., Cvjetan S., Jutronić M., Puizina J.2013. Aeromonas spp. simultaneously harbouring blaCTX-M-15, blaSHV-12, blaPER-1and blaFOX-2, in wild-growing Mediterranean mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) from Adriatic Sea, Croatia. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 166: 301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martínez-Murcia A. J., Saavedra M. J., Mota V. R., Maier T., Stackebrandt E., Cousin S.2008. Aeromonas aquariorum sp. nov., isolated from aquaria of ornamental fish. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58: 1169–1175. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65352-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ndi O. L., Barton M. D.2011. Incidence of class 1 integron and other antibiotic resistance determinants in Aeromonas spp. from rainbow trout farms in Australia. J. Fish Dis. 34: 589–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2011.01272.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puah S. M., Puthucheary S. D., Liew F. Y., Chua K. H.2013. Aeromonas aquariorum clinical isolates: antimicrobial profiles, plasmids and genetic determinants. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 41: 281–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puthucheary S. D., Puah S. M., Chua K. H.2012. Molecular characterization of clinical isolates of Aeromonas species from Malaysia. PLoS ONE 7: e30205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saavedra M. J., Guedes-Novais S., Alves A., Rema P., Tacão M., Correia A., Martínez-Murcia A.2004. Resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in Aeromonas hydrophila isolated from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Int. Microbiol. 7: 207–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weill F. X., Lailler R., Praud K., Kérouanton A., Fabre L., Brisabois A., Grimont P. A., Cloeckaert A.2004. Emergence of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (CTX-M-9)-producing multiresistant strains of Salmonella enterica serotype Virchow in poultry and humans in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42: 5767–5773. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5767-5773.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wikler M. A.2008. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: eighteenth informational supplement. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu C. J., Chen P. L., Wu J. J., Yan J. J., Lee C. C., Lee H. C., Lee N. Y., Chang C. M., Lin Y. T., Chiu Y. C., Ko W. C.2012. Distribution and phenotypic and genotypic detection of a metallo-β-lactamase, CphA, among bacteraemic Aeromonas isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 61: 712–719. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.038323-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye Y., Xu X. H., Li J. B.2010. Emergence of CTX-M-3, TEM-1 and a new plasmid-mediated MOX-4 AmpC in a multiresistant Aeromonas caviae isolate from a patient with pneumonia. J. Med. Microbiol. 59: 843–847. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.016337-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi S. W., You M. J., Cho H. S., Lee C. S., Kwon J. K., Shin G. W.2013. Molecular characterization of Aeromonas species isolated from farmed eels (Anguilla japonica). Vet. Microbiol. 164: 195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]