The likelihood of being bullied or victimized by one’s peers is high during middle childhood, a key time for the active construction of positive and negative self-cognitions (Hoover, Oliver, & Hazler, 1992; Ladd & Troop-Gordon, 2003; Pellegrini & Bartini, 2000; Smith, Shu, & Madsen, 2001). Such victimization may contribute to the emergence of negative schemas that, in turn, generate risk for problems such as depression (see Storch & Ledley, 2005; Roth, Coles, & Heimberg, 2002). Peer victimization researchers and theorists describe at least two broad types of victimization: overt/physical victimization and covert/relational victimization (Crick, Casas, & Ku 1999; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). Although research has focused on these constructs for over 20 years, empirical support for their discriminant and convergent validity and information about their relation to self-cognitions and depression is just beginning to emerge (Crick, Casas, & Nelson, 2002; Hoglund & Leadbeater, 2007). Three primary goals and hypotheses guided the current study. First, using a MTMM design and confirmatory factor analysis, we sought to add support for the convergent and discriminant validity of overt/physical and covert/relational victimization. Second, we hypothesized that both kinds of victimization would be positively related to negative self-cognitions and negatively related to positive self-cognitions in the victims; however, given the more insidious and psychological nature of covert/relational victimization, we expected it to be more strongly associated with self-cognitions. Third, we will examine gender differences in peer victimization and its relations to other constructs. And fourth, we will see preliminary support for the hypothesis that positive and negative self-cognitions account for the relation between victimization and depressive symptoms.

Targeted peer victimization (TPV) is defined as “the experience among children of being a target of the aggressive behaviour of other children, who are not siblings and not necessarily age-mates” (Hawker & Boulton, 2000, p. 441). Historically, studies of TPV have focused on overt/physical victimization, often highlighting the behavior of boys. Since then, studies have expanded their focus to include covert/relational victimization, perhaps more completely capturing the range of TPV experiences of both girls and boys (Crick et al., 1999). Overt/physical victimization occurs when a child is harmed or controlled by physical threats or damage (Crick & Bigbee, 1998). Covert/relational victimization consists of behavior intended to damage peer relationships, friendships, and acceptance often by excluding the victim from peer activities, withdrawing friendship, and spreading rumors (Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Grotpeter & Crick, 1996; Hawker & Boulton, 2000).

The preponderance of research on TPV and depression has relied on self-reports of both constructs. Such mono-methodism can inflate estimates of association (Cole, 1987; Cook & Campbell, 1979). Hawker and Boulton’s (2000) meta-analysis of two decades of research on TPV supports this possibility. When victimization was assessed by peer-report and depression was assessed by self-report, their correlation averaged .29 (with a range of .24 to .36). In contrast, when depression and victimization were both assessed by self-report, their correlation averaged .45 (with a range of .23 to .81). Card and Hodges (2008) noted that every source of information about victimization (e.g., self, peers, parents) has its liabilities. Self-reports are subject to both under-reporting (due to fear of negative consequences and unawareness of certain kinds of victimization) and over-reporting (due to biased perceptions; Cillessen & Bellmore, 1999; De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004). Peer nominations represent the extent to which victimization is known, not necessarily the frequency or intensity of the problem. Parent-reports may under-represent the problem, as parents may simply be unaware of many victimization events. To avoid these potential confounds in the current study, we followed advice of Card and Hodges (2008) and Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd (2002) by obtaining multiple measures (peer nominations, parent-reports, and self-reports) of both overt/physical and covert/relational TPV.

Both kinds of TPV convey poignant, negative self-relevant feedback to the victim. Such social feedback can jeopardize children’s construction of healthy self-cognitions (Harter, 2003). During middle childhood, various subtypes of self-cognition become increasingly differentiated (Harter, 1990) and integrated (LaGrange & Cole, 2008). Individual differences in self-cognition become increasingly stable (Abela & Hankin, 2008; Clark, Beck, & Alford, 1999; Cole, Martin, Peeke, Seroczynski, & Fier, 1999; Hankin, 2008; Rose & Abramson, 1992) and serve either to protect children from or predispose children for problems such as depressive symptoms (Cole & Jordan, 1995; Cole & Turner, 1993; Jacquez, Cole, & Searle, 2004). Elsewhere, we have speculated that during middle childhood and early adolescence, children internalize the feedback to which they are exposed as they construct for themselves a sense of their relative competence and incompetence in different domains (Cole, 1991). When such feedback is generally positive, children construct a sense of self as broadly competent; however, when such feedback is poignant, harsh, chronic, and targeted, children emerge with self-perceptions of incompetence, feelings of hopelessness, and a broadly pessimistic view of the future (Graham & Juvonen, 1998; Kochenderfer-Ladd & Ladd, 2001). In the current paper, we focus on overt/physical and covert/relational TPV as two broad classes of behaviors that provide children with competence-related feedback, disrupt the construction of positive self-cognitions, and foster the construction of negative self-perceptions.

More specifically, we hypothesize that children who experience high levels of overt/physical or covert/relational victimization will score low on measures of positive self-cognitions and high on measures of negative self-cognitions. Preliminary support for this hypothesis derives from studies showing that peer victimization is significantly related to global self-worth, several domains of self-perceived competence, fear of negative evaluation, as well as a depressive attributional style (e.g., Andreou, 2001; Boulton & Smith, 1994; Callaghan & Joseph, 1995; Gibb, Abramson, & Alloy, 2004; Prinstein, Cheah, & Guyer, 2005; cf. Kaukiainen et al., 2002; Salmivalli & Isaacs, 2005; Storch, Nock, Masia-Warner, & Barlas, 2003). Caldwell, Rudolph, Troop-Gordon, and Kim (2004) found a similar relation between peer stress and “relational self-view” (a combination of social self-worth, social self-competence, and perceived control).

These studies generally provide initial evidence of a link between peer victimization and self-cognitions, but they also suggest at least four important avenues for further research. First, relatively little work on the origins of depressive cognitions has distinguished between overt/physical and covert/relational victimization. Hunter and Boyle (2002) speculated that covert/relational victimization, being potentially isolating as well as harder to defend against, may be the more pernicious of the two. Others hypothesize that being subjected to both overt/physical and covert/relational victimization will result in more serious consequences than being subjected to only one form of TPV (Ladd & Ladd, 2001; Prinstein, Boergers, & Vernberg, 2001). The current study examines both of these possibilities.

Second is the linkage between TPV and depressive symptoms in young people. Hawker and Boulton’s (2000) review suggests that both overt/physical and covert/relational victimization are more strongly related to depressive symptoms than any other disorder. As consistent as this literature appears to be, many studies rely only on a single measure of victimization, typically a child self-report (for exceptions, see Hodges & Perry, 1999; Ladd, 2006; Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro, & Bukowski, 1999). In the current study, we assess TPV from multiple perspectives. We then estimate the relation of depressive symptoms to both overt/physical and covert/relational victimization using latent variable modeling.

The third issue pertains to gender differences in TPV and its relation to depressive symptoms. Although boys are more likely than girls to experience overt/physical victimization, gender differences in covert/relational victimization are less consistent (Crick, 1996; Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995; French, Jansen, & Pidada, 2002; Galen & Underwood, 1997). Several studies suggest that male and female adolescents experience similar prevalence rates of covert/relational victimization (e.g., Prinstein et al., 2001; Storch, Brassard, & Masia-Warner, 2003; Sullivan, Farrell, Kliewer, 2006). A review by Rose and Rudolph (2006) suggested that evidence of a gender difference in covert/relational TPV may depend on age or informant. Studies that have examined gender differences the strength of relation between depressive symptoms and covert/relational TPV this relationship have generated mixed results. Prinstein et al. (2001) found that relational victimization was uniquely associated with depressive symptoms for boys but not for girls. Conversely, Storch, Nock et al. (2003) reported that the same relationship was significant for girls but not for boys. In the current study, we will use three informants (self, peer, and parent) to examine two kinds of gender differences: (a) mean differences in the incidence of overt/physical and covert/relational victimization and (b) differences in the relation of victimization to depressive symptoms and related self-cognitions.

Our final goal was to provide preliminary test of whether the relation between TPV and depressive symptoms is a function of individual differences in positive and negative self-cognitions. To our knowledge, only five studies have begun to examine this question. First, in a retrospective study of young adults, Gibb, Benas, Crossett, and Uhrlass (2007) found that high levels of negative cognitions and low levels of positive cognitions explained a significant portion of the relation between reports of peer victimization and current depressive symptoms. The generalizability of these findings to children and adolescents remains unclear. Second, Hoglund, and Leadbeater (2007) found that negative cognitions about others were related to TPV but not depressive symptoms/anxiety in sixth and seventh-graders. We speculate that cognitions about oneself (not about others) will be more strongly related to both TPV and depressive symptoms. Third, Ladd and Troop-Gordon (2003) reported that social self-acceptance partially mediated the relation between victimization and internalizing problems in a sample of 5- to 10-year olds. Fourth, a similar study (Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2005) reported that change in social self-acceptance explained the relation between victimization and internalizing symptoms over the course of grades 4 through 6. Fifth, focusing on 12–17 year olds in the National Longitudinal Survey for Children and Youth, Adams and Bukowski (2008) found that self-concept mediated the relation between victimization and depressive symptoms but only for obese females (not for obese males, non-obese males or non-obese females). None of these studies distinguished between subtypes of victimization.

Method

Participants

We recruited participants from two rural/suburban elementary schools and one middle school in central Tennessee. We distributed IRB-approved consent forms to parents of 826 students grades 3 through 6. Over half the parents (N = 421) gave permission for their child to participate. Of the students for whom we had parental consent, 403 (96%) were present on the day of data collection and gave their assent to participate. One parent or guardian for each child was also invited to participate. Comparisons of participants to nonparticipants on ethnicity, sex, and grade level revealed only small, nonsignificant differences (ps > .20).

Children were in third (n = 100), fourth (n = 98), fifth (n = 101), and sixth (n = 104) grades. Ages ranged from 8 to 14 (M = 10.9, SD = 1.2). Overall, the sample evenly represented males (49%) and females (51%). The student sample included Caucasian (92.2%), African American (1.5%), Hispanic (2.8%), Asian (.5%), and other (3.0%) children. Family size (i.e., the number of children living at home) ranged from 1 to 9 (Mdn = 3).

Measures

Victimization by peers

We measured overt/physical and covert/relational TPV using self-reports, peer nominations, and parent reports. Utilization of multiple sources of information is crucial insofar as every source of information has unique strengths and weaknesses (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004).

Our self-report measure was a 6-item questionnaire designed to assess relational and physical victimization (RV-SR and PV-SR, respectively), expanding on the items used by Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd (2002), which converged with peer reports and peer nominations and correlated well with peer rejection measures in third and fourth grade. We modified items to reflect a broader range of physical and relational victimization, slightly re-worded for somewhat older children. The question stem was “Does anyone in your class ever….” The three relational items were (1) Tell others to stop being your friend, (2) Say you can’t play with them, and (3) Say mean things to other kids about you. The three physical items were (4) Kick you, (5) Hit you, and (6) Push you. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = a lot). Cronbach’s alphas were .72 for relational victimization and .81 for physical victimization. Principle axis factor analysis revealed a 2-factor structure with primary factor loadings above .58 and no cross loadings greater than .25 (see Table 1). The two factors correlated .44. We summed the items within factor to form two subscales.

Table 1.

Factor Loadings for Child Self-reported Peer Victimization Questionnaire

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Relational victimization items | ||

| Tell others to stop being your friend | .70 | −.08 |

| Say you can’t play with them | .68 | .03 |

| Say mean things to others kids about you | .65 | .09 |

| Physical victimization items | ||

| Kick you | −.03 | .79 |

| Hit you | −.06 | .87 |

| Push you | .25 | .58 |

Note. Factor correlation was .44.

Our parent report was a 9-item questionnaire designed to assess parental perceptions of the frequency with which their child was the victim of relational and physical victimization (RV-PR and PV-PR, respectively). Again, we modified the items from the Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd’s (2002) parent report to reflect a broader range of physical and relational victimization, with wording changed to make the items more appropriate for older children. The original measure showed moderate long-term stability and significant convergent validity with self- and peer-reports in grade 4. Parents rated how many days in a typical week (0 to 7) their child experienced various kinds of peer victimization. In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas were .93 for relational victimization and .71 for physical victimization. Principle axis factor analysis revealed a 2-factor structure with all primary factor loadings greater than .40 and no cross loadings above .34 (see Table 2). The two factors correlated r = .21. We summed the items within factor to form two subscales.

Table 2.

Factor Loadings for Parent-reported Peer Victimization Questionnaire

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Relational victimization items | ||

| A kid tries to get other kids to ignore your child | .92 | −.06 |

| Others try to keep your child out of their group | .86 | .04 |

| Say they won’t be friends with your child if your child doesn’t do what they say | .79 | −.09 |

| Say mean things about your child “behind his/her back” | .77 | .14 |

| Someone at school tries to get others to stop being friends with your child | .92 | .02 |

| Physical victimization items | ||

| Your child is picked on or hurt by kids at school | .34 | .57 |

| Other kids beat up your child | −.13 | .40 |

| Your child gets pushed around or bullied by other kids | .04 | .78 |

| Your child gets hit or kicked at school when the teachers aren’t looking | .14 | .69 |

Note. Factor correlation = .21.

Our peer nomination measure followed a format similar to that used in studies of children’s social status (e.g., Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982). Each child received a list of 20 names of students. Names were mostly from the respondent’s home room If there were not 20 consented participants from that roster, names were added from adjacent classrooms. Every student’s name appeared on 20 other students’ peer nomination forms. Separate forms were used to obtain peer nominations of relational and physical victimization (RV-PN and PV-PN, respectively). For example, the physical victimization item was:

Some kids get picked on or hurt by other kids at school. They might get pushed around. They might get bullied by others. They might even get beat up. Who gets treated like this? Who gets pushed or bullied by others?

Instructions ask respondents to mark all the names of classmates who fit a particular question. Scores for each student were the proportion of 20 students who indicated that the child was either physically or relationally victimized.

Self-cognition measures

Harter’s Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC; 1985) is a self-report inventory with 36 items reflecting developmentally appropriate specific domains (i.e., scholastic competence, social acceptance, behavioral conduct, physical attractiveness, and sports competence) plus a global self-worth scale. For each item, children select one of two statements to indicate whether they are more like a child who is good or a child who is not so good at a particular activity. Then they select statements indicating whether the selected statement is “sort of true” or “really true” about themselves. Responses are converted to 4-point rating scales with high scores reflecting better self-perceptions. The SPPC has a highly interpretable factor structure and all subscales have good internal consistency (Harter, 1982, 1985). In our sample, the Cronbach’s alphas for the SPPC scales ranged from .75 to .85.

The Cognitive Triad Inventory for Children (CTI-C; Kaslow, Stark, Printz, Livingston, & Tsai, 1992) is a 36-item self-report questionnaire assessing children’s views of themselves (e.g., “I am a failure”), their world (e.g., “The world is a very mean place”), and their future (e.g., “Nothing is likely to work out for me”). Children indicate having had specific thoughts using a yes/maybe/no response format, scored on 3-point scales. Scores range from 0 to 72 with higher scores indicating more negative views. Despite the word “triad” in the title, recent factor analysis of the measure reveals that a two-factor solution emerges over the course of middle childhood (LaGrange & Cole, 2008). One is a positive cognitions factor; the other is a negative cognitions factor. The measure has high internal consistency and good construct validity, correlating with measures of self-perception, self-worth, self-control, perceived contingency, and attributional style (Kaslow et al., 1992; LaGrange & Cole, 2008).

The Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale (CATS; Schniering & Rapee, 2002) is a self-report questionnaire assessing negative self-cognitions in young people. The questionnaire asks children to rate the frequency with which they have had 56 different negative thoughts in the previous week. Ratings are made on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all to 5 = all the time). The CATS yields a full scale score as well as scores on four subscales: physical threat (e.g., “I’m going to get hurt”), social threat (e.g., “I’m afraid I will make a fool of myself”), personal failure (e.g., “It’s my fault that things have gone wrong”), and hostility (e.g., “I won’t let anyone get away with picking on me”). Cronbach’s alphas range from .85 to .92 for the subscales and .95 for the full scale. Test-retest reliability is .79 at 1 month and .76 at 3 months; Schniering & Rapee, 2002).

Depressive symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985) is a 27-item self-report measure that assesses cognitive, affective, and behavioral symptoms in children. Each item consists of three statements graded in order of increasing severity, scored from 0 to 2. Children select one sentence from each group that best describes themselves for the past two weeks (e.g., “I am sad once in a while,” “I am sad many times,” or “I am sad all the time”). In nonclinic populations, the CDI has relatively high levels of internal consistency, test-retest reliability, predictive, convergent, discriminant, and construct validity (Cole & Jordan, 1995; Craighead, Smucker, Craighead, & Ilardi, 1998; Smucker, Craighead, Craighead, & Green, 1986; Timbremont, Braet, & Dreesson, 2004). The suicide item was deleted due to concerns by the public school administration.

Procedures

Prior to data collection, informed-consent statements were distributed to all children in each participating classroom. We offered a $100 donation to each classroom if 90% of children returned consent forms signed by a parent or guardian, either granting or denying permission for their child’s participation. Parent questionnaires (assessing parental perceptions of TPV) were distributed with the consents. Parents returned their consents to the university in preaddressed, stamped envelopes. Over 90% of the parents who granted consent for their child’s participation also returned the parent questionnaire. Whether or not parents returned the parent questionnaire was unrelated to any of the data collected from the child participants (ps > .20). Psychology graduate students administered the questionnaires to students during regular school hours. In keeping with the developmental level of the participants, we implemented slightly different data collection procedures at different grade levels. For third- and fourth-graders, one research assistant read the questionnaires aloud to a group of students. For students in the fifth and sixth grades, a research assistant introduced the battery questionnaires and allowed students to complete them at their own pace. At all grade levels, research assistants circulated among students to answer questions before, during, and after questionnaire administration. At the end of the administration, the students were given snacks and a decorated pencil for their participation.

Results

Preliminary Statistics

Examination of the items on our self-cognition, depressive symptoms, and victimization measures revealed a degree of content overlap. As a precaution, we constructed two sets of measures: one set consisted of full versions of the original measures; the second set consisted of the same measures after deleting selected items. From the CTI-C, we eliminated 3 items (“The things I do every day are fun,” “Bad things happen to me a lot,” and “I feel guilty for a lot of things”) because of item overlap with the CDI. After item deletion, Cronbach’s alphas were .87 for both the positive and negative cognition subscales. From the CATS, we dropped 2 items because of item overlap with the CDI (“Nobody really loves me” and “It’s my fault that things have gone wrong”) and 3 items because of item overlap with our victimization self-report (“I’m worried that I’m going to get teased,” “I’m always the one that gets picked on,” and “Other kids are making fun of me”). After item deletion, Cronbach’s alpha for was .97. From the CDI, we eliminated 5 items because of item overlap with either the CTI and CATS (“Nothing will ever work out for me,” “I do everything wrong,” “I hate myself,” “I do very badly in subjects I used to be good in,” and “I can never be as good as other kids”). After item deletion, Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

We conducted all major analyses twice: once with the original measures, and again with the reduced measures. The results were very similar. The pattern of significance and nonsignificance remained entirely unchanged. Specific parameter estimates changed only slightly. In our figures, we report both sets of estimates, putting those for the reduced measures in parentheses. As the results were so similar, we focus the text on the non-parenthetical measures. Table 3 contains means, standard deviations, and correlations for the measures without deleted items.

Table 3.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for All Measures

| Measure | Correlations | Boys | Girls | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Relational victimization (RV) | ||||||||||||||

| 1. self-report (RV-SR)*** | – | 5.36 | 2.04 | 6.38 | 2.79 | |||||||||

| 2. parent-report (RV-PR)** | .57 | – | 3.11 | 5.19 | 7.24 | 8.47 | ||||||||

| 3. peer nomination (RV-PN) | .32 | .50 | – | .05 | .11 | .06 | .11 | |||||||

| Physical victimization (PV) | ||||||||||||||

| 4. self-report (PV-SR)** | .37 | .48 | .26 | – | 4.96 | 2.35 | 4.24 | 1.93 | ||||||

| 5. parent-report (PV-PR) | .38 | .44 | .55 | .41 | – | 1.00 | 1.93 | 1.29 | 2.36 | |||||

| 6. peer nomination (PV-PN)** | .26 | .34 | .59 | .29 | .43 | – | .07 | .13 | .04 | .10 | ||||

| Self-cognition | ||||||||||||||

| 7. CTI-C (negative factor) | .50 | .42 | .31 | .34 | .27 | .31 | – | 22.83 | 5.52 | 23.48 | 6.53 | |||

| 8. CATS** | .66 | .53 | .31 | .43 | .32 | .28 | .73 | – | 84.52 | 29.31 | 94.76 | 41.73 | ||

| 9. CTI-C (positive factor)** | .51 | .41 | .26 | .28 | .24 | .32 | .75 | .66 | – | 22.84 | 4.86 | 24.19 | 6.32 | |

| 10. SPPC-global self-worth | −.43 | −.43 | −.25 | −.29 | −.19 | −.24 | −.63 | −.62 | −.59 | – | 18.72 | 3.12 | 18.06 | 3.64 |

| Depression | ||||||||||||||

| 11. CDI | .53 | .65 | .33 | .39 | .34 | .36 | .74 | .84 | .69 | −.64 | 27.17 | 6.65 | 28.16 | 7.44 |

Note. Significance of gender mean differences: ** p < .01 ** p < .001

SR = self-report, PR = parent report, PN = peer nomination, CTI-C = Cognitive Triad Inventory for Children, CATS = Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale, SPPC = Self-perception Profile for Children, CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

To test hypotheses about discriminant and convergent validity, we conducted a MTMM confirmatory factor analysis. As depicted in the upper model in Figure 1, we extracted two latent variables (overt/physical and covert/relational TPV) from six manifest variables. Three of the manifest variables loaded onto overt/physical TPV, and the other three loaded onto covert/relational TPV. All cross-loadings were fixed to zero. Following Kenny and Kashy’s (1992) recommendations, we allowed the disturbances to correlate for the two peer nominations, the two self-reports, and the two parent reports. We fit the model and estimated model parameters using full information maximum likelihood. The model provided a good fit to the data: χ2(5, N=403) = 10.58 (p > .060), normed fit index (NFI) = 0.98, incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.99, comparative fit index = 0.99, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .037 (with a 90% confidence interval of 0 to .068). Examination of the standardized path coefficients revealed three key findings.

Figure 1.

Path diagram of multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analytic model: Self-report (SR), parent report (PR), and peer nomination (PN) measures of covert/relational (C/R) and overt/physical (O/P) targeted peer victimization (TPV). Statistical significance is denoted: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

First, the correlation between the two latent variables was 0.82 (SE = .06; CI = .70 – .93). Controlling for potential shared method variance, this correlation is not subject to the inflation effects of mono-method bias (or to the deflation effects of measurement error). Although this correlation is significantly less than unity (and reveals approximately 66% shared variance between these constructs), it is still quite large, raising some concern about discriminant validity of the constructs. Consequently, we examined the nature of this relation more completely. First, we categorized all participants on overt/physical TPV. If any of our (parent, peer, and self-report) measures indicated nonzero amounts of overt/physical TPV, it was regarded as present. Otherwise overt/physical TPV was regarded as absent. Second, using analogous criteria, we categorized all participants on covert/relational TPV. Finally, we examined the bivariate distribution of these two indices (see Table 4). Overall, 34.0% of the participants evinced no history of either type of TPV, and 37.3% were categorized as experiencing both (at least to some degree). More interesting, however, 19.9% were categorized as having overt/physical TPV only, whereas only 8.8% were categorized as having covert/relational TPV only (p < .001).1 In other words, if students experienced overt/physical TPV, they had a higher probability (80.9%) of experiencing covert/relational TPV than vice versa (65.3%).

Table 4.

Joint and Conditional Probabilities for Overt/physical and Covert/relational Victimization

| Covert/relational TPV

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Total | ||

| Overt/physical TPV | Joint probabilities | |||

| No | 34.0% | 19.9% | 53.9% | |

| Yes | 8.8% | 37.3% | 46.1% | |

| Total | 42.9% | 57.1% | 100.0% | |

|

| ||||

| Conditional probabilities (overt|covert) | ||||

| No | 63.1% | 36.9% | 100.0% | |

| Yes | 19.1% | 80.9% | 100.0% | |

| Total | – | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| Conditional probabilities (covert|overt) | ||||

| No | 79.3% | 34.9% | – | |

| Yes | 20.5% | 65.3% | – | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | – | |

Second, all factor loadings were statistically significant (ps < .001), providing evidence of convergent validity. Pairwise comparisons via a series of nested model comparisons revealed that the factor loading for the parent report of covert/relational TPV (C/R-PR) was larger than that for the parent report of overt/physical TPV, Δχ2(1, N=403) = 23.74, (p < .001); however, the difference between the two loadings was relatively small (.76 vs. .81). Similar comparisons for the peer nomination and the self-report measures were not significant (ps > .10). Third, we detected significant shared method variance for the two peer nomination measures (r = .49, p < .001), but not for the other two methods.

In the context of this model, we tested the effects of sex and grade level by adding these variables as exogenous predictors of covert/relational and overt/physical TPV (see lower model in Figure 1. This model fit the data well by most criteria. The chi-square test was significant, χ2(13, N=403) = 35.12 (p < .001); however, with large sample sizes, statistically significant results do not always correspond to large effects. Examination of alternative indices revealed that the model explained the preponderance of the observed covariances and that discrepancies between the model and the data were small: NFI = 0.95, IFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.97, and RMSEA = .045 (with a 90% confidence interval of .028 to .064). Examination of the path coefficients revealed that Grade was significantly negatively related to both covert/relational TPV (β = −0.27, z = −4.08, p < .001) and overt/physical TPV (β = −0.21, z = −3.09, p < .05). Lower levels of both kinds of TPV were associated with higher grade levels. Sex was also significantly related to both kinds of TPV, but in opposite directions. Boys were more likely to experience overt/physical TPV (β = −0.25, z = −3.68, p < .001), whereas girls were more likely to experience covert/relational TPV (β = 0.24, z = 3.82, p < .001).2

Relation of TPV to Self-cognition

In order to test hypotheses about the relation of overt/physical and covert/relational TPV to positive and negative self-cognitions, we used latent variable structural equation modeling. The top panel of Figure 2 represents a model in which overt/physical and covert/relational TPV predict two new latent variables, positive and negative cognition. Positive self-cognition was represented by the global self-worth scale from the SPPC and the positive cognition subscale of the CTI-C. Negative self-cognition was represented by the CATS and the negative cognition subscale of the CTI-C. Because the two CTI-C scales derived from the same measure, we allowed their error terms to correlate. The model provided a good fit to the data by most criteria. The chi-square test was again significant, χ2(25, N=403) = 77.63 (p < .001); however, the alternative indices revealed that the discrepancies between the model and the data were quite small: NFI = 0.96, IFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.97, and RMSEA = .051 (with a 90% confidence interval of .036 to .065). Cross-group comparisons of measurement and structural path coefficients revealed no significant gender differences.

Figure 2.

Path diagrams of structural equation model. Upper panel: regressing positive and negative self-cognition onto covert/relational (C/R) and overt/physical (O/P) targeted peer victimization (TPV). Lower panel: regressing five domains of self-perceived competence onto C/R and O/P TPV.Statistical significance is denoted: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Although not indicated, all factor loadings were significant at p < .001. (Parenthesized values are estimates when overlapping items were deleted.)

Three results were noteworthy. First, the loadings of the positive and negative self-cognition measures onto their respective factors were large, significant, and in the expected direction (given the scaling of these measures). Second, covert/relational TPV was negatively related to positive self-cognitions (β = −.81) and positively related to negative self-cognitions (β = .84), even after controlling for the effects of overt/physical TPV. These effects were strong and statistically significant (ps < .001). Third, overt/physical TPV was not significantly related to either positive or negative self-cognitions after controlling for the effects of covert/relational TPV (βs = .02, ps > .50). Essentially no variance in either positive or negative self-cognition was explained by overt/physical TPV after controlling for covert/relational TPV. This finding does not imply that overt/physical victimization is uncorrelated with self-cognition. In fact, from the path diagram in Figure 2, we can calculate that the correlation of overt/physical victimization is (0.81)(0. 84) = .68 with negative cognitions and is (0.81)(−0.81) = −.66 with positive cognitions. These correlations are explained, however, by the effects of covert/relational TPV.

We also tested the relation of covert/relational and overt/physical victimization to the five content-specific domains of self-perceived competence measured by the SPPC. The model is depicted in the bottom panel of Figure 2, except that the two latent cognitive variables were replaced by five manifest variables representing the five domains. The model fit the data well. The model provided a good fit to the data by most criteria. The chi-square test was again significant, χ2(25, N=403) = 41.60 (p < .020); however, the alternative indices revealed that the discrepancies between the model and the data were quite small: NFI = 0.95, IFI = 0.98, CFI = 0.98, and RMSEA = .028 (with a 90% confidence interval of .011 to .043). Cross-group comparisons of measurement and structural path coefficients revealed no significant gender differences. As in the previous analysis, overt/physical TPV was not significantly related to any of the cognitive variables after controlling for covert/relational TPV. Covert/relational TPV, however was significantly related to physical appearance, athletic competence, and social acceptance (see Figure 2).3

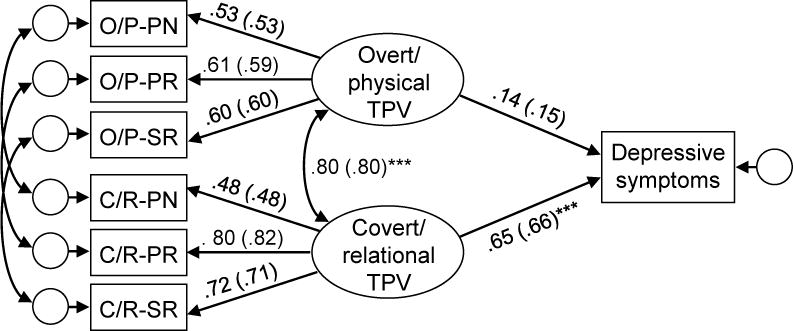

Relation of TPV to Depressive Symptoms

To examine the relation of overt/physical and covert/relational TPV to depressive symptoms, we again used latent variable structural equation modeling, but replaced the two TPV factors with a single measure of depression (see Figure 3). The model provided a good fit to the data by most criteria. The chi-square test was again significant, χ2(9, N=403) = 34.51 (p < .001); however, the alternative indices revealed that the discrepancies between the model and the data were quite small: NFI = 0.96, IFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.97, and RMSEA = .059 (with a 90% confidence interval of .039 to .080). Cross-group comparisons of the path coefficients revealed no significant gender differences. Examination of the structural path coefficients revealed two key results. First, covert/relational TPV was significantly and positively related to depressive symptoms (β = .65, p < .001), controlling for overt/physical TPV. Second, overt/physical TPV was not significantly related to depressive symptoms after controlling for the effects of covert/relational TPV (βs =.14, p > .30).

Figure 3.

Path diagram of structural equation model: Regressing depressive symptoms onto covert/relational (C/R) and overt/physical (O/P) targeted peer victimization (TPV). Statistical significance is denoted: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Although not indicated, all factor loadings were significant at p < .001. (Parenthesized values are estimates when overlapping were deleted.)

TPV, Self-cognition, and Depressive Symptoms

Finally, we examined the degree to which the relation between covert/relational TPV and depressive symptoms might be statistically explained by positive and negative self-cognitions. That is, does statistically controlling for positive and negative cognitions reduce or eliminate the relation between covert/relational TPV and depressive symptoms? We only focused on covert/relational TPV, as overt/physical explained no variance in depressive symptoms that was not explained by covert/relational TPV. First, we estimated the overall relation between covert/relational TPV and the CDI using the model depicted in the upper panel of Figure 4. This model fit the data well by all criteria: χ2(2, N=403) = .82 (p > .40), NFI = 1.00, IFI = 1.01, CFI = 1.00, and RMSEA = .00. The total effect of covert/relational TPV on the CDI was .78 (p < .001). Second, we added the two types of cognition to the model, as shown in the lower panel of Figure 4. This model also provided a good fit to the data. Although the chi-square test was significant, χ2(14, N=403) = 54.43 (p > .001), the alternative indices revealed that the discrepancies between the model and the data were small: NFI = 0.97, IFI = 0.98, CFI = 0.98, and RMSEA = .059 (with a 90% confidence interval of .026 to .081). From this model, we estimated the (a) the direct relation of covert/relational TPV to positive and negative self-cognitions, (b) the direct relation of positive and negative self-cognitions to depressive symptoms, (c) the residual relation of covert/relational TPV to depressive symptoms after statistically controlling for positive and negative self-cognitions, and (d) Sobel’s (1982) test of the indirect effects. (Note: we also conducted a two-group analysis, which revealed no significant gender differences.) Examination of the path coefficients revealed that the previously significant relation between TPV and depressive symptoms dropped from 0.78 to 0.33. Although still statistically significant at p < .05, Approximately 100 × (0.78 – 0.33)/0.78 = 58% of the effect of covert/relational TPV on depressive symptoms was explained by positive and negative self-cognitions (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007). Sobel’s test indicated that the indirect effect was significant through negative cognitions (z = 3.10, p < .002) but not through positive cognitions (z = 1.77, p > .07).

Figure 4.

Path diagram of structural equation model: Positive and negative self-cognition explain the relation between covert/relational (C/R) TPV and depressive symptoms. Statistical significance is denoted: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Although not indicated, all factor loadings were significant at p < .001. (Parenthesized values are estimates when overlapping were deleted.

Discussion

Four major findings derived from this investigation. First, multiple measures of covert/relational and overt/physical TPV yielded evidence of convergent and discriminant validity. Second, covert/relational and overt/physical TPV were both correlated with negative self-cognitions, positive self-cognitions, and depressive symptoms; however, in a multivariate context, the effects of covert/relational TPV subsumed the effects of overt/physical TPV. Third, gender and age differences emerged in covert/relational and overt/physical TPV; however, no group differences emerged in the strength of relations among the study variables. We elaborate on each of these findings and discuss how they support further investigation into the social-cognitive-developmental origins of cognitive diatheses for depression. And finally, preliminary analyses revealed that controlling for individual differences in negative self-cognitions substantially diminished the relation of covert/relational TPV to depressive symptoms.

First, the current MTMM results provided qualified support for the convergent and discriminant validity of multiple measures of two types of peer victimization. Confirmatory factor analysis revealed significant convergence of self-report, peer-nomination, and parent-report measures onto a pair of covert/relational and overt/physical TPV factors. In the context of this model, we detected significant shared method variance for the two peer-nomination measures but not for the two self-report measures or the two parent-report measures. Shared method variance on the peer-nomination measures could reflect the effects of in-group/out-group alliances, friendship patterns, or differences in the degree to which nominators were familiar with the individuals whom they were asked to nominate (Bellmore, Nishina, Witkow, Graham, & Juvonen, 2007; Jackson, Barth, Powell, & Lochman, 2006; Poulin, & Dishion, 2008). Further, the peer nomination measure had the smallest convergent validity coefficients (or factor loadings). We speculate that this could be due to a subtle difference in construct tapped by peer nominations versus parent and child inventories. Peer nominations assess the degree to which one’s victimization is public, whereas inventories assess the frequency of one’s victimization (see Poulin & Dishion, 2008, for elaboration on these differences). In general, these findings support De Los Reyes and Prinstein’s (2004) claim that monomethodism can bias the results of research on peer victimization. Our use of an MTMM design and structural equation modeling enabled us to control for such effects in the current study. Nevertheless, we urge the continued psychometric refinement of all methods for measuring peer victimization in children.

The same MTMM confirmatory factor analysis addressed the discriminant validity of the covert/relational and overt/physical TPV constructs. The two factors correlated 0.82 with each other. This correlation should be interpreted with two things in mind: (a) it represents the correlation between latent variables and is not attenuated due to the effect of random measurement error, and (b) the effects of shared method variance have been statistically controlled. A correlation of this magnitude suggests substantial, but not complete, overlap between these two constructs. They share 66% variance. More importantly, children who experienced overt/physical TPV were more likely to experience covert/relational TPV than vice versa. The non-overlap between these constructs is important in that it allows for the possibility that covert/relational and overt/physical TPV could relate to other variables in somewhat different ways, several of which we discuss below.

Second, covert/relational and overt/physical TPV were positively correlated with negative self-cognitions and negatively correlated with positive self-cognitions. When we examined the conjoint effects of both types of TPV onto self-cognitions, however, the contribution of covert/relational TPV remained strong whereas the contribution of overt/physical victimization became small and nonsignificant. Further, the interaction between the two types of TPV was not significant This pattern, which replicates and extends the results of Storch et al. (2003), appears to derive from the nature of the overlap between the two types of TPV. Overt/physical TPV without covert/relational TPV was relatively rare, whereas covert/relational TPV without overt/physical TPV was not that unusual. The current results further suggest that covert/relational TPV is the more critical ingredient, at least insofar as positive and negative self-cognitions are concerned. These findings are commensurate with the speculation that children’s self-cognitions are informed by and constructed out of social interactions with others, especially interactions that convey poignant, evaluative, and self-relevant information (Cole, 1991; Rose & Abramson, 1992; see also Cooley, 1902; Mead, 1934). Previous research has implicated peer victimization as one important kind of social interaction related to children’s global self-worth, self-perceived competence, learned helplessness, and even the emergence of a victimization self-schema (Andreou, 2001; Boulton & Smith, 1994; Callaghan & Joseph, 1995; Gibb et al., 2004; Prinstein et al., 2005; Rosen et al., 2007). The current work extends this research, suggesting that covert/relational TPV is the more insidious form of victimization, at least insofar as the construction of positive and negative self-cognitions are concerned.

Similar results emerged regarding the relation of TPV to depressive symptoms. Both forms of TPV were positively correlated with our depression measure. In models that included both types of TPV as predictors, only covert/relational TPV was a significant predictor. Overt/physical victimization accounted for essentially no variance in depressive symptoms after controlling for covert/relational TPV. On the one hand, this finding supports Hunter and Boyle’s (2002) speculation that covert/relational TPV is more detrimental. They suggested that its particularly pernicious effects may be due to the facts that relational victimization serves to isolate the victim and is difficult to counteract. On the other hand, these results do not support Ladd and Ladd’s (2001) suggestion that being subjected to both overt/physical and covert/relational victimization will result in more serious consequences than being subjected to only one or the other. Although covert/relational TPV had maladaptive effects over-and-above overt/physical victimization, the reverse was not true. Overt/physical TPV had no predictive utility over-and-above covert/relational TPV. Instead of focusing on the combined effects of two kinds of TPV, we speculate that more serious consequences should emerge as a function of increased frequency or chronicity of TPV. If TPV conveys negative self-relevant information to the victim and if each TPV episode constitutes a kind of “learning trial,” then children who are chronically victimized will have had had ample opportunity to acquire negative information about themselves. To the degree that such negative self-information augments the construction of negative self-schemas, we reason that chronically victimized youth will be at increased risk for depression.

Third, gender and age differentially related to both covert/relational and overt/physical TPV. Girls experienced more covert/relational TPV than did boys. Boys experienced more overt/physical TPV than did girls. Boys and girls experienced less overt/physical and covert/relational victimization at older grade levels. The age difference has been described elsewhere as a likely effect of age-related socialization (Rivers & Smith, 1994). The gender difference has also been previously documented although results have varied as a function of age and informant (e.g., Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005; Rose & Rudolf, 2006; Schaefer et al., 2002), and the pattern has not always emerged (e.g., Prinstein et al., 2001). Using multiple informants and controlling for method variance, the current study suggests that girls are significantly more likely to be the targets of covert/relational aggression and that boys are significantly more likely to experience overt/physical aggression. Interestingly, the current study revealed no gender differences in the structural models that we tested. In other words, the strength and pattern of relations between victimization, positive cognitions, negative cognitions, and depressive symptoms were quite similar across gender. Taken together, these findings suggest that differences exist in the kinds of victimization that boys and girls experience, but not in the degree to which victimization experiences are related to depressive cognitions or symptoms. Future research should examine the possibility that girls are placed at greater risk for depressive symptoms in part because they are more likely to experience the kinds of victimization that are especially linked to the construction of negative self-schemas and to the erosion of positive self-schemas.

Finally, we present preliminary evidence suggesting that individual differences in negative self-cognitions accounted for a substantial amount of the relation of covert/relational TPV to depressive symptoms. That is, statistically controlling for self-cognitions greatly diminished the relation between TPV and self-reported depressive symptoms. Only one previous study has described this phenomenon, reporting that low levels of positive self-cognitions and high levels of negative self-cognitions mediated the relation between peer victimization and depressive symptoms (Gibb et al., 2007). We must note, however, that Gibb et al.’s results derived from college students (not children) and relied upon on retrospective measures of victimization. The current study substantially extends Gibbs et al.’s results by focusing directly on children and utilizing multiple concurrent measures of peer victimization. Although self-cognitions no doubt continue to develop across the lifespan, middle childhood and early adolescence are particularly important times for the differentiation, integration, and development of relatively stable individual differences in self-perceived competence (Cole et al., 1999; Harter, 1990, 2003; LaGrange & Cole, 2008).

Implications for research, policy, and practice

The current study has important clinical implications. First, we found evidence that both types of TPV are linked to depressive symptoms and also that the relation of TPV to depressive symptoms was explained by self-cognitions. This suggests that victimized youth may require psychological intervention and that cognitive-behavioral therapy, with its emphasis on cognitive restructuring and problem solving techniques may be particularly valuable. Second, the finding that covert/relational TPV accounted for the effects of overt/physical TPV on depressive symptoms highlights the fact that forms of TPV that are potentially less blatant and likely harder for school personnel to detect than physical abuse still have serious consequences. Many victims may not be recognized as such by those in a position to help them. Because of this, individual-level interventions may not be possible – or at least not in a timely manner. TPV must be recognized as part of a broader social problem, requiring school-wide prevention efforts. School-based social skills training programs appear to have positive effects on both perpetrators and victims (e.g., Bradshaw, Sawyer, & O’Brennan, 2009; Card & Hodges, 2008; Hanish & Guerra, 2000; Jenson & Dieterich, 2007; Kazdin, Esveldt-Dawson, French, & Unis, 1987). Empirically supported prevention programs exist, such as the Social Skills Group Intervention (DeRosier, 2002), the Steps to Respect Program (Frey, Hirschstein, Edstrom, & Snell, 2009), and the Olweus bullying prevention program (Olweus et al. 2007). Classroom-based strategies such as the Jigsaw Classroom (see Aronson, Blaney, Rosenfield, & Sikes, 1977) can also reduce hostility faced by ostracized and victimized students (Swearer, Grills, Haye, & Cary, 2004).

Several shortcomings of the current study suggest avenues for future research. First and foremost, the current study is cross-sectional, not longitudinal. As such it cannot truly test the implied mediational model. Longitudinal research is needed so that investigators can statistically control for prior levels of the downstream variables when testing the effects of TPV on self-cognition, testing the effects of self-cognition on depressive symptoms, and testing the role of self-cognition as a mediator of the TPV-depression relation (Cole & Maxwell, 2003; Maxwell & Cole, 2007). Second, much of our interpretation of these results implies an expectation that TPV drives the construction of self-cognitions and predisposes depressive symptoms. The reverse may also be true. Hodges and Perry’s (1999) data suggest that internalizing problems may be as much a cause as an effect of TPV, both part of reciprocating vicious cycle. Third, although we obtained multiple measures of peer victimization and self-cognitions, we relied on a single self-report of depressive symptoms, the CDI. Despite the fact that the CDI is well validated and represents the most commonly used measure of depression in children, it is only one measure. As such, relations between depression and either TPV or self-cognitions could be underestimated. Even though our analyses revealed these relations to be relatively strong, future estimates would likely be stronger still, if a depression latent variable could be extracted from multiple measures of children’s depressive symptoms. Fourth, some theorists and investigators have it useful to consider the higher-order construct of emotional abuse, suggesting that all forms of abuse – be it relational or physical, or be it peer or parental – has its effect as a manifestation as a larger class of abuse (Gibbs et al., 2001; Hankin, 2005). More result on the utility of subtyping maltreatment is clearly needed. Finally, the current study focused on the content, not the function, of positive and negative self-schemas. Such schemas likely affect depression via multiple mechanisms, including selective attention, associative learning, and memory. Measuring the effects of peer victimization on the processing, not just the content, of self-relevant information would be a valuable addition to this line of future research (e.g., Rosen et al., 2007).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a gift from Patricia and Rodes Hart, by support from the Warren Family Foundation, and by a grant from NICHD (P30HD15052) to the Kennedy Center of Vanderbilt University. We thank Lynn Seifert, Judy Bell, Mickey Dyce, Julia Felton, Kirby Fitzgerald, Amy Folmer, Cindy Higginbotham, Carlos Tilghman-Osborne, and Dawn Young for their support at various stages of this project. We also thank the children, teachers, and parents who participated in the study.

Footnotes

We also tried other categorization criteria. Using more conservative criteria (naturally) diminished the overall rates of both kinds of TPV; however, the ratio of overt/physical to covert relational TPV remained very stable across a wide range of cutoffs.

We also tested a model with Sex by Grade interaction term; however, this effect was not significant for either covert/relational or overt/physical TPV (ps > .20).

For both sets of analyses (one, predicting positive and negative cognitions, and the other, predicting the five specific domains), we also tested the interaction between overt/physical and covert/relational TPV. Using Ping’s (1996) two-step method, we found no evidence of an interaction between the two types of TPV in the prediction of any outcome variable (ps > .10).

Contributor Information

David A. Cole, Email: david.cole@vanderbilt.edu, Department of Psychology and Human Development, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37203-5721; phone: 615-343-8712; fax: 615-343-9494

Melissa A. Maxwell, Department of Psychology and Human Development, Vanderbilt University

Tammy L. Dukewich, Department of Psychology and Human Development, Vanderbilt University

Rachel Yosick, Department of Psychology, Lipscomb University, Nashville, TN.

References

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL. Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children and adolescents: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 35–78. [Google Scholar]

- Adams RE, Bukowski WM. Peer victimization as a predictor of depression and body mass index in obese and non-obese adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:858–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreou E. Bully/victim problems and their association with coping behaviour in conflictual peer interactions among school-age children. Educational Psychology. 2001;21:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson E, Blaney NT, Stephan C, Rosenfield R, Sikes J. Interdependence in the classroom: A field study. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1977;69:121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bellmore AD, Nishina A, Witkow MR, Graham S, Juvonen J. The influence of classroom ethnic composition on same- and other-ethnicity peer nominations in middle school. Social Development. 2007;16:720–740. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin M, Begin G. Peer status and self-perception among early elementary school children: The case of the rejected children. Child Development. 1989;60:591–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb02740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton MJ, Smith PK. Bully/victim problems in middle-school children: Stability, self-perceived competence, peer perceptions and peer acceptance. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1994;12:315–329. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw CP, Sawyer AL, O’Brennan LM. A social disorganization perspective on bullying-related attitudes and behaviors: The influence of school context. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;43:204–220. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9240-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell MS, Rudolph KD, Troop-Gordon W, Kim D. Reciprocal influences among relational self-views, social disengagement, and peer stress during early adolescence. Child Development. 2004;75:1140–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan S, Joseph S. Self-concept and peer victimization among school children. Personality and Individual Differences. 1995;18:161–163. [Google Scholar]

- Card NA, Hodges EVE. Peer victimization among schoolchildren: Correlations, causes, consequences, and considerations in assessment and intervention. School Psychology Quarterly. 2008;23:451–461. [Google Scholar]

- Card NA, Hodges EVE. Peer victimization among schoolchildren: Correlations, causes, consequences, and considerations in assessment and intervention. School Psychology Quarterly. 2008;23:451–461. [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AHN, Bellmore AD. Accuracy of social self-perceptions and peer competence in middle childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1999;45:650–675. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DA, Beck AT, Alford BA. Scientific foundations of cognitive theory and therapy of depression. New York: Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA. The utility of confirmatory factor analysis in test validation research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;4:584–594. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA. Change in self-perceived competence as a function of peer and teacher evaluation. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:682–688. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Jordan AE. Competence and memory: integrating psychosocial and cognitive correlates of child depression. Child Development. 1995;66:459–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Myths and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Turner JE. Models of cognitive mediation and moderation in self-reported child depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:271–281. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Peeke LA, Seroczynski AD, Fier J. Children’s over-and underestimation of academic competence: A longitudinal study of gender differences, depression, and anxiety. Child Development. 1999;17:459–473. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley CH. Human nature and the social order. New York: Scribner; 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Craighead WE, Smucker MR, Craighead LW, Ilardi SS. Factor analysis of the Children’s Depression Inventory in a community sample. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. The role of relational aggression, overt aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children’s future social adjustment. Child Development. 1996;67:2317–2327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Bigbee MA. Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multi-informant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:337–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66:710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Casas JF, Ku H. Physical and relational peer victimization in preschool. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:376–385. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Casas JF, Nelson DA. Toward a more complete understanding of peer maltreatment: Studies of relational victimization. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2002;11:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cullerton-Sen C, Crick NR. Understanding the effects of physical and relational victimization: The utility of multiple perspectives in predicting social-emotional adjustment. School Psychology Review. 2005;34:147–160. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Prinstein MJ. Applying depression-distortion hypotheses to the assessment of peer victimization in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:325–335. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRosier ME. Group interventions and exercises for enhancing children’s communication, cooperation, and confidence. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Egan SK, Perry DG. Does low self-regard invite victimization? Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:299–309. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French DC, Jansen EA, Pidada S. United States and Indonesian children’s and adolescents’ reports of relational aggression by disliked peers. Child Development. 2002;73:1143–1150. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey KS, Hirschstein MK, Edstrom LV, Snell JL. Observed reductions in school bullying, nonbullying aggression, and destructive bystander behavior: A longitudinal evaluation. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2009;101:466–481. [Google Scholar]

- Galen BR, Underwood MK. A developmental investigation of social aggression among children. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:589–600. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Emotional maltreatment from parents, verbal peer victimization, and cognitive vulnerability to depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2004;28:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Rose DT, Whitehouse WG, Donovan P, Hogan ME, Cronholm J, Tiernay S. History of childhood maltreatment, depressogenic cognitive style, and episodes of depression in adulthood. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:425–446. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Benas JS, Crossett SE, Uhrlass DJ. Emotional maltreatment and verbal victimization in childhood: Relation to adults’ depressive cognitions and symptoms. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2007;7:59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Juvonen J. Self-blame and peer victimization in middle school: an attributional analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:587–599. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotpeter JK, Crick NR. Relational aggression, overt aggression, and friendship. Child Development. 1996;67:2328–2338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Guerra NG. Children who get victimized at school: What is known? What can be done? Professional School Counseling. 2000;4:113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology: Prospective tests of attachment, cognitive vulnerability, and stress as mediating processes. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2005;29:645–671. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Stability of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: A short-term prospective multiwave study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:324–333. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The Perceived Competence Scale for Children. Child Development. 1982;53:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the self-perception profile for children. Denver, CO: University of Denver; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Developmental differences in the nature of self-representations: Implications for the understanding, assessment, and treatment of maladaptive behavior. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990;14:113–142. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The development of self-representations during childhood and adolescence. In: Leary RR, Tangney JP, editors. Handbook of self and identity. New York: Guilford; 2003. pp. 610–642. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The development of self-representations. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. New York: Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hawker DSJ, Boulton MJ. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:441–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Perry DG. Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:677–685. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Bukowski WM. The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:94–101. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoglund WL, Leadbeater BJ. Managing threat: Do social-cognitive processes mediate the link between peer victimization and adjustment problems in early adolescence? The Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:525–540. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover JH, Oliver R, Hazler RJ. Bullying: Perceptions of adolescent victims in Midwestern USA. School Psychology International. 1992;13:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter SC, Boyle JME. Perceptions of control in the victims of school bullying: the importance of early intervention. Educational Research. 2002;44:323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hymel S, Rubin KH, Rowden L, LeMare L. Children’s peer relationships: Longitudinal prediction of internalizing and externalizing problems from middle to late childhood. Child Development. 1990;61:2004–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MF, Barth JM, Powell N, Lochman JE. Classroom contextual effects of race on children’s peer nominations. Child Development. 2006;77:1325–1337. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquez FM, Cole DA, Searle B. Self-perceived competence as a mediator between maternal feedback and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:355–367. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000030290.68929.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenson JM, Dieterich WA. Effects of a skills-based prevention program on bullying and bully victimization among elementary school children. Prevention Science. 2007;8:285–296. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Stark KD, Printz B, Livingston R. Cognitive Triad Inventory for Children: Development and relation to depression and anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1992;21:339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kaukiainen A, Salmivalli C, Lagerspetz K, Tamminen M, Vauras M, Mäki H, et al. Learning difficulties, social intelligence and self-concept: Connections to bully-victim problems. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2002;43:269–278. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Esveldt-Dawson K, French NH, Unis A. Problem-solving skills, training and relatianship therapy in the treatment of antisocial child behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:76–85. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe K, Berndt TJ. Relations of friendship quality to self-esteem in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1996;16:110–129. Table 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA. Analysis of the multitrait-multimethod matrix by confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer-Ladd B, Ladd GW. Variations in peer victimization: Relations to children’s maladjustment. In: Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacological Bulletin. 1985;21(4):995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd BJ, Ladd GW. Variations in peer victimization. In: Juvonen J, G S, editors. Peer Harassment in School: The Plight of the Vulnerable and Victimized. The Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Peer rejection, aggressive or withdrawn behavior, and psychological maladjustment from ages 5 to 12: An examination of four predictive models. Child Development. 2006;77:822–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer-Ladd B. Identifying victims of peer aggression from early to middle childhood: Analysis of cross-informant data for concordance, estimation of relational adjustment, prevalence of victimization, and characteristics of identified victims. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:74–96. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Troop-Gordon W. The role of chronic peer difficulties in the development of children’s psychological adjustment problems. Child Development. 2003;74:1344–1367. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Troop-Gordon W. The role of chronic peer difficulties in the development of children’s psychological adjustment problems. Child Development. 2003;74:1344–1367. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaGrange B, Cole DA. An expansion of the trait-state-occasion model: Accounting for shared method variance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2008;15:241–271. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead GH. The genesis of the self and social control. International Journal of Ethics. 1925;35:251–273. [Google Scholar]

- Mead GH. Mind, self, and society from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Neary A, Joseph S. Peer victimization and its relationship to self-concept and depression among school girls. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;16:183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:424–443. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini A, Bartini M. A longitudinal study of bullying, victimizatioin, and peer affiliation during the transistion from primary school to middle school. American Educational Research Journal. 2000;37:699–725. [Google Scholar]

- Ping RA. Latent variable interaction and quadratic effect estimation: A two-step technique using structural equation analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:166–175. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin F, Dishion TJ. Methodological issues in the use of peer sociometric nominations with middle school youth. Social Development. 2008;17:908–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological functioning of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:477–489. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Cheah CS, Guyer AE. Peer victimization, cue interpretation, and internalizing symptoms: preliminary concurrent and longitudinal findings for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:11–24. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose DT, Abramson LY. Developmental predictors of depressive cognitive style: Research and theory. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology. IV. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 323–349. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen PJ, Milich R, Harris MJ. Victims of their own cognitions: Implicit social cognitions, emotional distress, and peer victimization. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Roth DA, Coles ME, Heimberg RG. The relationship between memories for childhood teasing and anxiety and depression in adulthood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16:149–164. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(01)00096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli C, Isaacs J. Prospective relations among victimization, rejection, friendlessness, and children’s self- and peer-perceptions. Child Development. 2005;76:1161–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M, Werner NE, Crick NR. A comparison of two approaches to the study of negative peer treatment: General victimization and bully/victim problems among German school children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2002;20:281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Schniering CA, Rapee RM. Development and validation of a measure of children’s automatic thoughts: the children’s automatic thoughts scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:1091–1109. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P, Shu S, Madsen K. Characteristics of victims of school bullying: Developmental changes in coping strategies and skills. In: Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. Peer Harassment in school: The plight of the vunerable and victimized. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 332–351. [Google Scholar]

- Smucker MR, Craighead WE, Craighead LW, Green BJ. Normative and reliability data for the children’s depression inventory. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1986;14:25–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00917219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Ledley DR. Peer victimization and psychosocial adjustment in children: current knowledge and future directions. Clinical Pediatrics. 2005;44:29–38. doi: 10.1177/000992280504400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Brassard MR, Masia-Warner CI. The relationship of peer victimization to social anxiety and loneliness in adolescence. Child Study Journal. 2003;33:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Nock MK, Masia-Warner CL, Barlas ME. Peer victimization and social-psychological adjustment in Hispanic-American and African-American children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2003;12:439–452. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TN, Farrell AD, Kliewer W. Peer victimization in early adolescence: Association between physical and relational victimization and drug use, aggression, and delinquent behaviors among urban middle school students. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:119–137. doi: 10.1017/S095457940606007X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swearer SM, Grills AE, Haye KM, Cary PT. Internalizing problems in students involved in bullying and victimization: Implications for intervention. In: Espelage DL, Swearer SM, editors. Bullying in American schools. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 63–83. [Google Scholar]