Abstract

Hawai‘i Youth Services Network (HYSN) was founded in 1980 and is incorporated as a 501(c) (3) organization. HYSN plays a key role in the planning, creation, and funding of local youth services. One of HYSN's focuses is teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STI) prevention among foster youth. Foster youth are at a greater risk for teen pregnancy and STI due to a variety of complex factors including instability, trauma, and emancipation from the foster care system. This article highlights how HYSN is leveraging both federal and local funding, as well as other resources, in order to implement an evidence-based teen pregnancy and STI prevention program adapted for foster youth.

Keywords: Teen Pregnancy Prevention, Teen Sexually Transmitted Infection Prevention, Foster Youth, Adapting Evidence-Based Programs

Background

Hawai‘i Youth Services Network

Hawai‘i Youth Services Network (HYSN) was founded in 1980 and is incorporated as a 501(c) (3) organization. HYSN plays a key role in the planning, creation, and funding of local youth services through partnerships with 50 membership agencies. While HYSN programs are based on community needs and funding availability, all of HYSN's work is rooted in their Positive Youth Development Philosophy:1

The children and youth of Hawai‘i are our future. The way we treat them today, the opportunities we provide them, and the investments we make in their development will influence the kind of adults they will become.

Children and youth live and participate in our communities. We must recognize and value them as community assets. We need to include young people in decisions that affect their lives in communities, school systems, churches, and in our public policy decision-making.

We must meaningfully engage youth in all aspects of community life.

HYSN is a training and technical assistance provider for Hawai‘i and other Pacific Island nations and territories for grant writing, sustainability, collaboration, evaluation, and teen pregnancy prevention. Executive Director, Judith F. Clark, MPH (HYSN ED), is well known locally and nationally for her ability to successfully build partnerships and collaborations and develop culturally relevant and sustainable programs. In 2005 and 2010, HYSN ED received the Hawai‘i State Legislature's Award for Hawai‘i's Outstanding Advocate for Children and Youth.

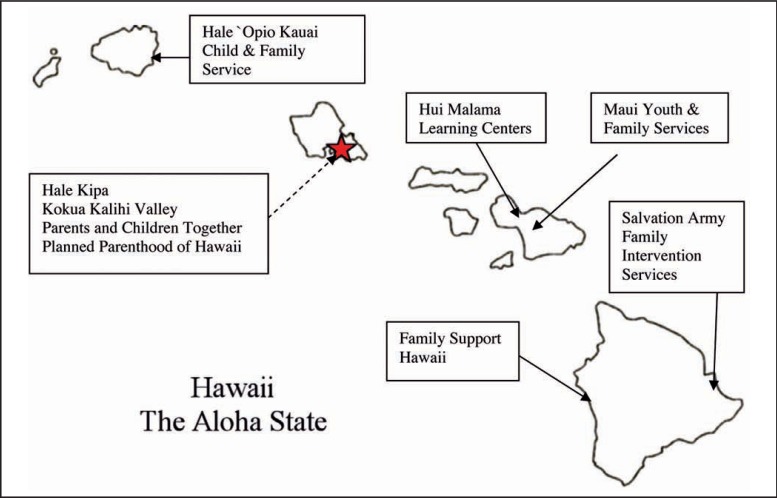

Teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention are among HYSN's primary foci. In 2010, HYSN received a 5-year, Tier 1: Teen Pregnancy Prevention - Replication of Evidence-Based Programs grant from the Federal Office of Adolescent Health (OAH).2 HYSN was awarded $999,999 annually to manage the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Partnership of the Pacific (TPPPP), which includes ten organizations throughout the Hawaiian Islands (see Figure 1).2

Figure 1.

Map of TPPPP Partners

Additionally, HYSN recognizes that foster youth have unique needs when it comes to pregnancy and STI prevention. Hawai‘i was one of five teams that participated in The Prevention of Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Foster Youth Institute (The Institute). The Institute was a partnership between The National Campaign and the American Public Human Services Association and funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.3 Hawai‘i's core team included HYSN ED, HYSN Teen Pregnancy Prevention Director, DHS - Child Welfare Service Assistant Administrator, Hale Kipa Deputy CEO, and Hale ‘Opio Kaua'i Executive Director (HYSN ED, personal communication, October 2014).

Making Proud Choices and the Importance of Teen Pregnancy and STI Prevention

Making Proud Choices (MPC) is one of two evidence-based curricula used by the TPPPP.2 MPC can be implemented in community-based or school settings as it consist of eight modules that can be conducted in two, four-hour sessions or eight, one-hour sessions.4,5 Using a randomized control trial with a pre-test and post-tests at 3, 6, and 12 months, evaluation of MPC found sexually active participants had decreased frequency of intercourse and were more likely to use condoms.5

HYSN has also had previous success with MPC, and in 2008 received the CDC's Horizon Award for Excellence in Health Education for adapting MPC to be culturally appropriate for Asian and Pacific Islander youth. HYSN post-tests at end of MPC instruction show significant increases in knowledge, attitudes, and skills that decrease the risk of unplanned pregnancy and STIs. HYSN began implementing MPC in 2007 with previous CDC funding and more than 5,417 students have participated in the program during CDC and OAH grant years. The following indicators, derived from post-test surveys administered to students who completed the program, lend support to MPC's effectiveness:

94% got the correct answers to questions on behaviors that will help prevent HIV, STDs, and pregnancy

92% report that they can say “no” to sex and unsafe sex

91% report positive attitudes/beliefs about condom use

88% report the ability to get or buy condoms and to put them on correctly

98% report that it is a good idea to use a condom every time a couple has sex

90% report intention to use condoms if they have sex

Reducing teen pregnancy rates is an important public health issues because three out of ten women in America experience pregnancy before age 20.6 In 2010, there were 57 pregnancies per 1,000 teen girls (aged 15 to 19 years) nationally and 64 pregnancies per 1,000 teen girls in Hawai‘i.7 There are also ethnic disparities among Hawai‘i teen pregnancy rates. In 2010 there were 31 pregnancies per 1,000 White teen girls, 40 pregnancies per 1,000 Asian teen girls, and 181 per 1,000 Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander teen girls.8 Additionally compared to sexually active youth nationwide, sexually active youth in Hawai‘i are less likely to use condoms.9

While not all teen pregnancies result in birth, teen childbearing is costly. In 2010, taxpayers spent $9.4 billion on teen childbearing nationwide and $32 million in Hawai‘i.6,10 Another consequence of teen childbearing is that teen mothers are less likely to receive prenatal care, which can result in low-birth weight babies, birth defects, and infant mortality.11 Moreover, teen mothers are less likely to graduate from high school or earn a GED. Research on teen fathers is limited, but according to one research brief, half of teen fathers have additional children by their early twenties, which can negatively affect education and financial stability.12

STIs (including chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, herpes, and the Human Papilloma virus) are another costly public health issue.13 The United States spends $16 billion annually on new STI cases.14 Unfortunately, teens and young adults (ages 15–24) account for half of 20 million new STI cases nationally each year.14 The Hawai‘i State Department of Health (DOH) reports rising STI since 2000.15 For example, Hawai‘i has seen increased gonorrhea rates, from 47 per 100,000 in 2008 to 50 per 100,000 in 2011.16 Similar to trends seen nationally, young people in Hawai‘i bear a disparately higher burden of STI.17 For example, 15–19 year olds account for 30% of local chlamydia cases.18

Arguably the most serious type of STI is the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), which causes Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Although HIV rates have decreased since the 1980s,19 it is important to remain vigilant about prevention because HIV can be asymptomatic for up to 10 years.13 Moreover in 2010, youth (ages 13 – 24) accounted for 26% of new HIV cases in the United States and almost 60% of youth infected with HIV were unaware of their status.19 Over the past decade, Hawai‘i has been below the national average for HIV and AIDS incidence.20 According to a 2013 DOH HIV/AIDS Surveillance Annual Report, from 1983 – 2012, 13 – 24 year olds account for 13% of all HIV and 4% of AIDS cases respectively.21

Youth in Foster Care

Foster care can be defined as “24-hour substitute care for children outside their own homes” and placements include locations such as non-relative foster care home, relative foster care home, group homes, and emergency shelters.22 On September 30, 2013, there were 402,378 children in foster care nationwide, with over 50% being at least 11 years old.23 According to the National KIDS COUNT, in 2012, Hawai‘i had 1,079 children and youth (ages 0 – 17) in foster care.24

Foster youth are more likely to be sexually active by age 13, have more sexual partners, experience sexual assault or rape, not use contraception, and experience teen pregnancy.25 The Midwest Study, a longitudinal study conducted in Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin (n=536), found that compared to the overall population, by age 26, former foster youth are more likely to have an STI, with chlamydia being the most common STI for both women and men.26 According to State of Hawai‘i Department of Human Services (DHS), 266 girls gave birth to 269 babies while in foster care from 2005–2010 (Lee Dean, Assistant Administrator, email, January 2011).

Many complex factors contribute to increased risk of teen pregnancy and STI among foster youth. Three examples—instability, trauma, and emancipation—are described below.

Instability.

In a recent article, Friedman questioned if foster youth receive adequate medical care and education regarding sexual health due to unstable living situations.27 One study found from elementary through high school, 65% of former foster youth changed schools seven or more times.28 Likewise, the average number of foster care placements is three.27 Consequences of instability include gaps in medical care, missing out on school-based teen pregnancy and STI prevention programs, and unstable relationships with adults.27,29 The absence of relationships with trusted adults can be especially detrimental as 80% of teens cite parents as a major influence in decisions about sex.30 Moreover, changes in caregivers, social workers, and physicians, coupled with lack of sound policies, result in confusion about who is responsible for educating foster youth about sexual health.27,29

Trauma.

There are many different definitions of trauma. One, provided by the Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative, notes that “three common elements characterize all forms of trauma: the event was unexpected, the individual was unprepared, and there was nothing that the person could do to prevent the event from happening.”31 Foster youth experience high rates of trauma and events can occur both before and during foster care.32 Examples of trauma foster youth may experience include direct forms of abuse and neglect, separation from family and friends, instability, and being exposed to domestic and community violence.33

Trauma has been linked to a variety of health conditions including depression, anxiety, substance abuse/dependence, self-harm, personality disorders, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).31 Some types of trauma have also been linked to an increase in sexual risk behaviors. For example, men who have sex with men with a history of childhood sexual abuse are more likely to participate in sexual risk behavior and report being HIV positive.34

Emancipation.

Around 11% of foster youth are aging out of foster care nationally and locally each year, which means 18 year olds are often left to navigate the complexities of adulthood alone.35 Lack of family or state support during this crucial transition puts former foster youth at high risk for academic struggles, financial instability, homelessness, poor mental and physical health, involvement with the criminal justice system, and pregnancy.35 In hopes of creating smoother transitions for foster youth, some states have extended care to age 21.35 Hawai‘i is one of these states and launched the Imua Kakou (http://www.imua21.org) program on July 1, 2014. While it is too early to ascertain if this change will impact teen pregnancy and STI locally, another study using the Midwest cohort found that 19 year olds who stayed in care past 18 were more likely to attend college, be financially stable, and for women, report fewer pregnancies.36

Presently no studies or reviews have been identified addressing foster youth specific teen pregnancy or STI prevention programs. Thus, the strategy needs to be informed by related evidence and best practices. Important examples include:

Trauma-Informed Practice.

Due to high rates of trauma among foster youth, it is key for service providers to be educated about trauma. The Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative states “trauma-informed practice involves understanding the impact of trauma on young people's current functioning and recognizing the ways systems are capable of adding to young people's trauma. Trauma-informed practice provides supports and opportunities to promote healthy recovery and optimal brain development throughout adolescence and emerging adulthood.”31

Inclusive Language.

When working with foster youth, it is also important to use inclusive language to ensure youth do not feel stigmatized or overlooked. For example, research has found many LGBTQ youth are forced to leave home due to rejection and/or lack of safety, thus it is believed there is high prevalence of foster youth who identify as LGBTQ.37 Examples of inclusive language include using partner instead of boyfriend or girlfriend and trusted adult instead of parent.38

Adapting MPC for Foster Youth

Starting in 2011, The Institute teams worked with an advisory committee, Dr. Loretta Sweet Jemmott (lead MPC developer), and directly with foster youth to adapt and pilot test the MPC program for foster youth.3 The adapted curriculum is titled Making Proud Choices! - For Youth In Out-Of-Home Care (MPC+), consists of ten, 75-minute modules, and includes the following modifications to address the needs of foster youth:3 Facilitator Guide: Education about the foster care system and trauma

Module Content: Increased opportunities to discuss healthy vs. unhealthy relationships, acknowledging experiences of trauma and abuse, inclusive language (eg, LGBTQ, pregnant or teen parents, talk with a trusted adult about sexual health questions)

Implementing MPC+ in Hawai‘i

While participation in The Institute did not include funding for MPC+ implementation, other valuable resources were provided. HYSN received five copies of the MPC+ curriculum, a two-day facilitator training on adaptations, and dedicated time and tools for core team members to solidify plans to implement and sustain the program (HYSN ED, personal communication, October 2014).

Additionally HYSN received approval from OAH to utilize TPPPP funds to implement MPC+ (eg, facilitator time and training). In order to obtain approval for use with OAH funds, HYSN submitted the curriculum for an extensive medical accuracy and adaptation review process conducted by OAH. The review generated multiple small changes that were incorporated into the final published version of MPC+. HYSN also worked with a University of Hawai‘i at Manoa Master of Public Health practicum student to submit applications to two local foundations and was awarded $15,000 from the Atherton Family Foundation to further support MPC+.

MPC+ is currently being implemented at four, Independent Learning Programs (ILP); one on O‘ahu, one on Kaua‘i, one on Maui, and one on the Big Island. ILP are offered through community-based organizations and focus on providing foster youth (ages 12 – 18) and former foster youth (ages 18 – 21) with support and skills to transition into adulthood.39 ILP services can be extended to age 26 if former foster youth are attending college or a full-time vocational program (HYSN ED, personal communication, October 2014).

ILP have reported that participant recruitment is a challenge due to the voluntary nature of the MPC+ program and some youth do not see the need for ILP services. Additionally, in rural areas such as Kaua‘i, physical distance between foster youth and transportation challenges have been noted (HYSN stakeholder meeting, personal communication, April 2013). HYSN has been able to utilize funding from the Atherton Family Foundation to mitigate these barriers. For example, ILP staff can offer incentives (eg, gift cards) for participation and/or successfully recruiting participants. Likewise, session refreshments are provided, which serve as a secondary incentive and ensure participants are not hungry and better able to focus. Additionally, former foster youth who are currently stable in their life situation can be hired as recruiters/co-facilitators to help increase program creditability. Kaua‘i recently hired the first group of former foster youth who are called “peer-mentors.”

To enable access to foster youth on Kaua'i, staff decided to hold day camps during school breaks. MPC+ sessions are conducted between other activities such as arts and crafts and geocaching (using GPS coordinates to locate hidden objects).40 An added benefit of the camp format is foster youth have been able to expand their network by meeting peers from the other parts of the island (HYSN stakeholder meeting, personal communication, April 2013). Finally, to help with transportation barriers, some Atherton Family Foundation funds can be used to fuel ILP vehicles or provide mileage reimbursement to caregivers to ensure foster youth attend MPC+ sessions.

As of December 2013, 43 foster youth in Hawai‘i have participated in MPC+ (HYSN ED, personal communication, October 2014). Evaluation of MPC+ includes pre-and post-tests at 3, 6, and 12 months, facilitator fidelity logs, and monitoring of sessions by HYSN's Teen Pregnancy Prevention Director. Additionally, HYSN regularly convenes stakeholders, including MPC+ facilitators, to discuss quality improvement issues (HYSN stakeholders meeting, personal communication, April 2013). Based on post-tests collected so far, foster youth demonstrate gains that are comparable to other students who have received MPC training.

HYSN is aware that implementing MPC+ is not a stand-alone solution to the complexities of teen pregnancy and STI among foster youth.41 Therefore HYSN is also dedicated to increasing community capacity to address pregnancy and STI prevention as well. For example, if MPC+ is encouraging foster youth to talk to trusted adults, then adults who work with foster youth need to be equipped to talk about sexual health. To address this need HYSN partnered with another program, It Takes an Ohana, to offer five trainings titled Helping Our Providers Educate (H.O.P.E.), which teaches adults how to be more approachable and comfortable when talking to foster youth about sexual health. Similar trainings have also been provided to caregivers and other stakeholders (HYSN ED, personal communication, October 2014). Trainings like H.O.P.E. are important as one California study found many service providers do not speak with foster youth about relationships and sexual health and 64% of social workers feel they have not received adequate training in comprehensive sex education.29

One lesson HYSN learned after completing the 2-day MPC+ facilitator training is the importance of cross-training public health and social service professionals before moving forward with MPC+ curriculum training. In other words, social service providers need to be trained in Sex Ed 101 (eg, anatomy, puberty, contraception, and STI) and on the flip side, health educators need to have a basic understanding of Hawai‘i's foster care system. The need for cross-training was recognized through participant feedback (HYSN ED, personal communication, October 2014). Constantine, et al, received similar feedback in their study as one social worker shared “it would be better support to our foster youth by first starting off with providing staff with the proper education and not just assuming that staff are aware of the issues.”29

Conclusion

While some progress has been made in reducing the overall teen pregnancy and STI rates, there is more to be done, especially among high-risk groups such as foster youth.7,42 Offering MPC+ through ILP is one way to help ensure foster youth in Hawai‘i have greater access to education about their sexual health. HYSN's ability to strategically leverage resources in order to implement MPC+, as well as attention to building community capacity through relevant trainings, are also important steps in ensuring Hawai‘i's foster youth are supported in an appropriate and healing manner by both public health and social service professionals.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Jane Chung-Do DrPH.

The project described was partially supported by Grant Number TP1AH000002 from the Office of Adolescent Health. Contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Health and Human Services or the Office of Adolescent Health.

Contributor Information

Jay Maddock, Office of Public Health Studies at John A Burns School of Medicine.

Donald Hayes, Hawai‘i Department of Health.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identify a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hawaii Youth Services Network (HYSN), author HYSN brochure. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of Adolescent Health, author. Grants: Grantees. [October 6, 2014]. http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/grants/grantees/tier1-hi-hawaii.html. Updated June 19, 2013.

- 3.The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Integrating Making Proud Choices for Youth in Out-of-Home Care into the Child Welfare System [webinar] [October 6, 2014]. https://thenationalcampaign.org/resource/child-welfare-system-webinar. Published April 2913.

- 4.The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Making Proud Choices! A Safer Sex Approach to HIV/STD and Teen Pregnancy Prevention. [October 15, 2014]. http://thenationalcampaign.org/effective-programs/making-proud-choices-safer-sex-approach-hivstd-and-teen-pregnancy-prevention.

- 5.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Abstinence and Safer Sex HIV Risk-Reduction Interventions for African American Adolescents: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 1998;279(19):1529–1536. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Counting It Up: The Public Costs of Teen Childbearing: Key Data. [October 6, 2014]. http://thenationalcampaign.org/sites/default/files/resource-primary-download/counting-it-up-key-data-2013-update.pdf. Published December 2013.

- 7.The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. National & State Data: The National Story. [October 6, 2014]. http://thenationalcampaign.org/data/landing.

- 8.Hawai‘i Health Data Warehouse, author. Hawai‘i State Department of Health, Office of Health Status Monitoring, Vital Statistics; United States Census, Pregnancy Rate in Hawai‘i (Residents Only), for Females Aged 15–19 Years, for the Years 2000–2012. [October 13, 2014]. http://www.hhdw.org/cms/uploads/Data%20Source_%20Vitals/Vital%20Statistics_Live%20Births%20in%20Hawaii_IND_Teen%20pregnancy%20rate.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. Youth Risk Behavioral Survey: Hawai‘i 2013 and United States 2013 Results. [October 6, 2014]. http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/App/Results.aspx?

- 10.The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Counting It Up: The Public Costs of Teen Childbearing in Hawai‘i in 2010. 2014a. [October 6, 2014]. http://thenationalcampaign.org/sites/default/files/resource-primary-download/fact-sheet-hawaii.pdf. Published April 2014.

- 11.Kaye K. Why It Matters: Teen Childbearing and Infant Health. The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. [October 2, 2014]. http://thenationalcampaign.org/sites/default/files/resource-primary-download/childbearing-infant-health.pdf. Published October 2012.

- 12.Scott ME, Steward-Streng NR, Manlove J, Moore J. The Characteristics and Circumstances of Teen Fathers: At the Birth of Their First Child and Beyond. [October 15, 2014]. Child Trends, Research Brief Publication #2012-19. http://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Child_Trends-2012_06_01_RB_TeenFathers.pdf. Published June 2012.

- 13.Planned Parenthood. Health Info and Resources: STDs. [October 6, 2014]. http://www.plannedparenthood.org/health-info/stds-hiv-safer-sex.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. CDC Fact Sheet: Incidence, Prevalence, and Cost of Sexually Transmitted Infections in the United States. [October 13, 2014]. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/STI-Estimates-Fact-Sheet-Feb-2013.pdf. Published February 2013.

- 15.State of Hawai‘i Department of Health, author. STD/AIDS Prevention Branch: Epidemiology - Data and Statistics. [October 13, 2014]. http://health.hawaii.gov/std-aids/sexually-transmitted-diseases-stds/epidemiology-data-and-statistics/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. 2011 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance. Table 14. Gonorrhea - Reported Cases and Rates by State/Area and Region in Alphabetical Order, United States and Outlying Areas, 2007—2011. [October 13, 2014]. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats11/tables/14.htm. Updated December 12, 2012.

- 17.Bridges, E. Hawai‘i's Youth: Focus on Sexual and Reproductive Health. [October 15, 2014]. http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/publications/publications-a-z/636-hawaiis-youth-focus-on-sexual-and-reproductive-health. Published 2008.

- 18.Young K. Hawai‘i: Sexual Disease Hot Spot. Honolulu, HI: Midweek; [October 8, 2014]. Retrieved from http://archives.midweek.com/content/columns/theyoungview_article/hawaii_sexual_disease_hot_spot/. Published February 21, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. HIV Prevention: Progress to Date. [October 13, 2014]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/HIVFactSheets/Progress-508.pdf. Published August 2013.

- 20.Health Trends in Hawai‘i. Health Status: HIV/AIDS. [October 13, 2014]. http://www.healthtrends.org/status_stds_aids.aspx.

- 21.State of Hawai‘i Department of Health, author. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Annual Report: Cases to December 31, 2012. [October 13, 2014]. http://health.hawaii.gov/std-aids/files/2013/05/2012-HIV_rep.pdf. Published August 15, 2013.

- 22.Ng AS, Kaye K. Why It Matters: Teen Childbearing, Education, and Economic Wellbeing. [October 6, 2014]. https://thenationalcampaign.org/resource/why-it-matters-teen-childbearing-education-and-economic-wellbeing. Published July 2012.

- 23.Courtney M, Dworsky A, Brown A, Cary C, Love K, Vorhies V. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: outcomes at age 26. [October 8, 2014]. http://www.chapinhall.org/sites/default/files/Midwest%20Evaluation_Report_4_10_12.pdf. Published 2011.

- 24.Child Welfare Information Gateway, author. Foster care statistics 2012. [October 6, 2014]. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/foster.pdf#page=1&view=Key%20Findings. Published November 2013.

- 25.Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System, author. The AFCARS Report: Preliminary FY 2013 Estimates as of July 2014. [October 13, 2014]. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport21.pdf.

- 26.Annie E Casey Foundation, author. KIDS COUNT Data Center: Hawai‘i Indicators. [October 8, 2014]. http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data#HI/2/0.

- 27.Friedman J. Cause for Concern: Unwanted Pregnancy and Childbirth Among Adolescents in Foster Care. [October 8, 2013]. http://www.youthlaw.org/publications/yln/2013/jan_mar_2013/cause_for_concern_unwanted_pregnancy_and_childbirth_among_adolescents_in_foster_care/. Published 2013.

- 28.Pecora PJ, Kessler RC, Williams J, et al. Improving family foster care: findings from the Northwest Foster Care Alumni Study. [October 8, 2014]. http://www.casey.org/media/AlumniStudies_NW_Report_FR.pdf. Updated March 14, 2005.

- 29.Constantine WL, Jerman P, Constantine NA. Sexual Health Needs of California's Foster and Transitioning Youth in Three California Counties. [October 15, 2014]. http://crahd.phi.org/FTYSHNA-FullReport-3-2-09.pdf. Published March 2, 2009.

- 30.Kaiser Sex Smarts: Decision Making. [October 15, 2014]. http://www.hawaii.edu/hivandaids/SexSmart%20%20%20Sexual%20Decision%20Making.pdf. Published September 2000.

- 31.Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative. Issue Brief #5: Trauma-Informed Practice with Young People in Foster Care. [October 6, 2014]. http://www.jimcaseyyouth.org/trauma-informed-practice-young-people-foster-care.

- 32.Salazar AM, Thomas EK, Gowen LK, Courtney ME. Trauma exposure and PTSD among older adolescents in foster care. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(4):545–551. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0563-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klain EJ, White AR. Implementing Trauma-Informed Practices in Child Welfare. [October 15, 2014]. http://childwelfaresparc.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Implementing-Trauma-Informed-Practices.pdf. Published November 2013.

- 34.Kalichman SC, Gore-Felton C, Benotsch E, Cage M, Rompa D. Trauma symptoms, sexual behaviors, and substance abuse: correlates of childhood sexual abuse and HIV risks among men who have sex with men. [October 6, 2014];J Child Sex Abus. 2004 13(1):1–15. doi: 10.1300/J070v13n01_01. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15353374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stern IR, Nakamura L. Hawai‘i KIDS COUNT Issue Brief: Improving Outcomes for Youth Transitioning Out of Foster Care. [October 5, 2014]. http://uhfamily.hawaii.edu/publications/brochures/12101011_COF_Foster_Youth_Report-v7.pdf. Published 2012.

- 36.Courtney M, Dworsky A. Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth: Outcomes at Age 19: Executive Summary. [October 8, 2014]. http://www.chapinhall.org/sites/default/files/ChapinHallDocument_3.pdf. Published May 2005.

- 37.Sullivan C, Sommer S, Moff J. Youth in the Margins: A Report on the Unmet Needs of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Adolescents in Foster Care. [October 8, 2014]. http://www.jimcaseyyouth.org/sites/default/files/documents/youthinthemargins_2001.pdf. Published 2001. Updated 2005.

- 38.Augustine J, Jackson K, Norman J. Transitions: Creating Inclusive Programs. [October 5, 2014]. http://advocatesforyouth.org/storage/advfy/documents/transitions1404.pdf. Published June 2002.

- 39.State of Hawai‘i Department of Human Services, author. Independent Learning Programs - ILP. [October 15, 2014]. http://humanservices.hawaii.gov/ssd/home/child-welfare-services/ilp/

- 40.Kirby D. Emerging Answers 2007: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. [October 15, 2014]. https://thenationalcampaign.org/resource/emerging-answers-2007—full-report. Published November 2007.

- 41.Goesling, Colman, Trenholm, Terzian, Moore Programs to reduce teen pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and associated sexual risk behaviors: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(5):499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.004. Epub 2014 Feb 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]