Introduction

The fruit from the palm Areca catechu (L.) commonly referred to as areca nut (AN) is botanically a drupe fruit with an outer leathery part (exocarp or skin; and mesocarp, which can be fleshy or hard) that surrounds a shell (hardened endocarp with a seed or pit) at all times during ripening (Figure 1). ANs in their variable preparations, commonly wrapped in a betel leaf therefore the widespread name “Betel nut” (BN; see below), are consumed worldwide by an estimated 600 million people among all age groups and social classes with prevalent consumption throughout the Indian subcontinent, East and Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands.1,2 In Guam, AN chewing is widely practiced among many populations (including Chamorros, Yapese, Palauans and Chuukese), and approximately 11% of Guam's population chew on a regular basis.3 In some areas of India, the frequency of AN use has been increasing among the youth and has been speculated to serve as a gateway for tobacco use.4,5

Figure 1.

Base ingredients of a Betel quid: areca nut, Piper betle L. leaf, and slaked lime (which may be powdered - as shown, or in liquid or paste form). Chewing tobacco or tobacco from cigarettes is often added according to preference in addition to other ingredients such as cloves, cardamom, alcohol, nutmeg, aniseed, ginger, and sweeteners such as coconut.

There is considerable variation in the way ANs are consumed. They can be chewed alone, wrapped in a leaf of the betel pepper (Piper betle L.) then referred to as BN, or as a “betel quid” (BQ), whose recipes, despite varying regionally and locally within countries, generally consists of a whole or portion of an AN wrapped in a leaf of the betel pepper (Piper betle L.) together with other additives such as slaked lime (calcium hydroxide) and sometimes tobacco (from chewing tobacco or cigarettes) (Figure 1) and/or spices.6–9 Lime is typically obtained from the burning of coral or shellfish or extraction from limestone and is sold in paste, liquid, or powdered forms (Figure 1).7,8 Other ingredients such as cloves, cardamom, alcohol, nutmeg, aniseed, ginger, and sweeteners such as coconut are sometimes added to the various AN preparations for extra flavoring according to preference.7,8,10 In many countries such as those in South Asia, proprietary BQ mixtures are commercially manufactured and heavily advertised towards youth.11,12 Oftentimes, the nut is conveniently sold in proximity to tobacco products as to indirectly promote its concurrent use (eg, selling of single cigarettes).13

The chewing of AN in its various preparation forms is a socially accepted habit in many countries of the Western Pacific region13 and is used as a means of promoting social relationships and community ties. This habit also has cultural and religious significance among some populations where chewing is endemic.1,7,14 Factors thought to influence chewing commencement include encouragement from family members, friends, or role models at a young age, as well as peer pressure; in addition, some users have described AN chewing as a way to pass time or avoid boredom and loneliness.1,13,15

Reported Effects of Consumption

Globally, AN is the fourth most commonly used psychoactive drug after tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine.10,16 Its consumption has been claimed to produce feelings of euphoria, well-being, palpitation, salivation, diaphoresis, heightened alertness, hunger satisfaction, and increased stamina.12,17 Arecoline, the main AN alkaloid released upon mastication, has been reported to be responsible for several of these effects through activation of the sympathetic pathway13 although many other AN alkaloids could also have psychotropic activity. For example, arecaidine, the hydrolyzed product of arecoline, has been reported to relieve anxiety through its ability to inhibit gamma-amino butyric acid reuptake, a property likely to result in potential abuse and dependence and, accordingly, its use with or without tobacco has been associated with dependency.10,18

Compelling evidence suggests strong associations between AN chewing and increased risks for developing oral cancer (particularly oral squamous cell carcinoma), leading to the classification of AN chewing both with BQ and without tobacco as carcinogenic to humans by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.9 Oral cancer mortality rates as high as 80% have been reported in some countries in the Western Pacific Region, which is in stark contrast to the average worldwide 5-year cumulative mortality rate of less than 50%.13 In Guam, the incidence of mouth cancer in some Micronesian groups who regularly chew AN is almost three times higher than it is in Caucasians, who rarely consume AN.19 In addition to oral cancer, studies have reported associations between BQ chewing and esophageal, pharynx, lung, pancreas, cervical, and, albeit limited evidence, liver cancer.13,20,21

Oral cancer has functionally and cosmetically devastating consequences22 and is often preceded by clinically visible white (leukoplakia) or red (erythroplakia) lesions of the oral mucosa and/or the insidious, chronic condition oral submucous fibrosis (OSF), which has a high propensity for malignant transformation12,23–25 with relative risks ranging from 29 to 154 attributable to AN chewing.22 OSF is an irreversible condition that persists even after cessation of chewing22 and is characterized by changes in the fibroelasticity of the oral mucosa followed by progressive stiffness and, eventually, limited mouth opening that can lead to difficulty in eating.26

Both the duration and frequency of BQ use has been reported to increase the risk of developing OSF thereby suggesting a dose-response relationship,27 which is of particular concern for individuals who begin chewing at a young age as they are more likely to develop OSF and cancer due to the cumulative years of exposure.

Furthermore, BQ chewing has been associated with the practice of other risky habits such as alcohol and tobacco consumption.21,28 Not only are BQ chewers usually also smokers but chewers who smoke generally smoke more [cigarettes per day] than smokers who do not chew.21 BQ chewers have also been noted to be less physically active and have higher blood triglycerides and lower HDL levels when compared to non-smoking, non-chewing individuals.21

Prevention Initiatives

Globally, AN consumption has become a health burden of increasing significance, warranting an ongoing and urgent need for cessation programs. The use of biomarkers to identify areca exposure is of great need for measuring the success of cessation programs as it would assist in verifying self-reports of AN cessation.

In an attempt to identify such biomarkers, we recently completed a pilot study in Guam that analyzed the chemical composition of saliva at baseline and during chewing from habitual AN chewers who consumed one usual dose of a typical AN preparation consumed in Guam; specifically, the participants were randomized to consume either the AN alone (AN group), the AN wrapped in a piper betle leaf (AL group), or a BQ consisting of one AN wrapped in betel piper leaf with slaked lime and cigarette tobacco (BQ group). The saliva obtained during chewing vs baseline showed significantly increased levels of guvacine (AN and BQ groups), arecoline (all three groups), guvacoline (AN group), arecaidine (all three groups), nicotine (BQ group), and chavibetol (AL and BQ groups).

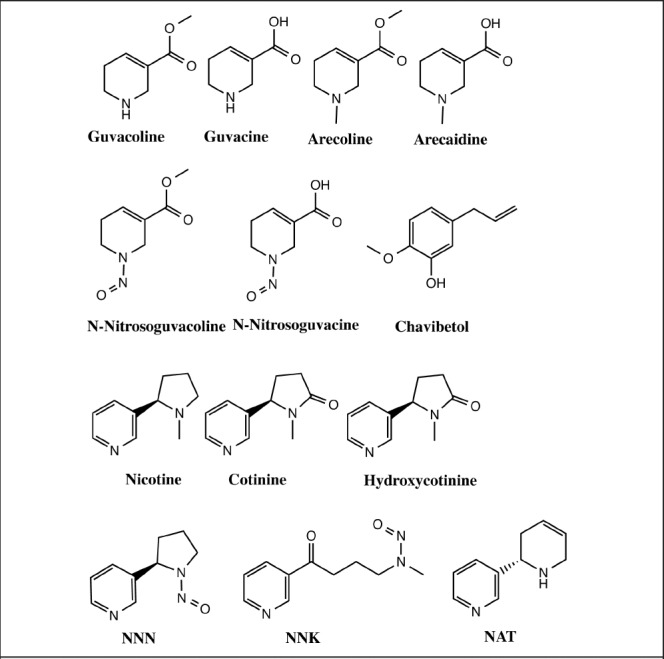

We also found significant differences between the three AN preparation groups for total areca alkaloids (guvacine, arecoline, guvacoline, and arecaidine; P = .045), total nicotine alkaloids (nicotine, cotinine, hydroxycotinine, N-nitrosoguvacoline, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), N'-nitrosonornicotine (NNN), and N-nitrosoanatabine (NAT); P < .001) and chavibetol (P = .006). Chemical structures of these compounds are shown in Figure 2. From our results, we determined the following chemical patterns in saliva during chewing to be useful for future biomarker studies aimed at identifying extent and type of AN chewing: areca alkaloids indicates when an AN is chewed (AN group), areca alkaloids in combination with chavibetol indicates when an AN with the piper betel leaf is chewed (AL group), and areca alkaloids plus chavibetol and tobacco-specific alkaloids indicates when an AN with the Piper betle L. leaf, slaked lime, and tobacco is chewed (BQ group). The quantitative difference of these markers can be used to identify chewing type and also to distinguish from tobacco smoking. Pharmacokinetic studies for these markers are ongoing in our group.

Figure 2.

Structures of alkaloids and nitroso compounds detected in areca nuts and tobacco, and chavibetol (an allyl benzene) identified in Piper betle leaves; all these compounds were also found in saliva samples during chewing of these plant parts.

Despite the global prominence of AN consumption, there is little information on how to help chewers quit. For that reason, we are currently developing AN cessation programs to be directed towards chewers in Guam and Saipan. Our new knowledge regarding AN biomarkers will allow us to test the efficacy of these programs with greater validity and precision. Ultimately, the development of successful AN cessation programs will help to reduce the incidence and overall burden of oral cancer in the Asia-Pacific region.

Disclosure Statement

Supported by NCI grants U54 CA143727 and P30 CA71789. None of the authors identify any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Paulino Y. Areca (Betel) Nut Chewing Practices in Micronesian Populations. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2011;3(1):19–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warnakulasuriya SC, Trivedy C, Peters TJ. Areca nut use: an independent risk factor for oral cancer. BMJ. 2002;324(7341):799–800. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paulino Y. Achievement Rewards for College Scientists Selection Meeting. Honolulu, HI: 2008. Betel nut chewing in Micronesian populations. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajan G, Ramesh S, Sankaralingam S. Areca nut use in: rural Tamil Nadu: a growing threat. Indian J Med Sci. 2007;61(6):332–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandra PS, Mulla U. Areca nut: the hidden Indian ‘gateway’ to future tobacco use and oral cancers among youth. Indian J Med Sci. 2007;61(6):319–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeng JH, Chang MC, Hahn LJ. Role of areca nut in betel quid-associated chemical carcinogenesis: current awareness and future perspectives. Oral Oncol. 2001;37(6):477–492. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(01)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta PC, Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of areca nut usage. Addict Biol. 2002;7(1):77–83. doi: 10.1080/13556210020091437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norton SA. Betel: consumption and consequences. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(1):81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70543-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.IARC, author. Smokeless Tobacco and Some Tobacco-specific N-Nitrosamines. Vol. 89. Lyon: World Health Organization; 2007. IARC Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benegal V, Rajkumar RP, Muralidharan K. Does areca nut use lead to dependence? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97(1–2):114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta PC, Ray CS. Epidemiology of betel quid usage. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33(4 Suppl):31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.IARC, author. Betel-quid and areca-nut chewing and some areca-nut derived nitrosamines. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2004;85:1–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO, author; WHO, editor. Review of areca (betel) nut and tobacco use in the Pacific: a technical report. Geneva: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu NS. Effects of Betel chewing on the central and autonomic nervous systems. J Biomed Sci. 2001;8(3):229–236. doi: 10.1007/BF02256596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little MA, et al. The reasons for betel-quid chewing scale: assessment of factor structure, reliability, and validity. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:62. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betel-quid and areca-nut chewing and some areca-nut derived nitrosamines. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2004;85:1–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu NS. Neurological aspects of areca and betel chewing. Addict Biol. 2002;7(1):111–114. doi: 10.1080/13556210120091473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herzog TA, et al. The Betel Quid Dependence Scale: replication and extension in a Guamanian sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haddock RL. Oral cancer incidence disparity among ethnic groups on Guam. Pac Health Dialog. 2005;12(1):153–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Secretan B, et al. A review of human carcinogens—Part E: tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, coal smoke, and salted fish. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(11):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wen CP, et al. Cancer risks from betel quid chewing beyond oral cancer: a multiple-site carcinogen when acting with smoking. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(9):1427–1435. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9570-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nair U, Bartsch H, Nair J. Alert for an epidemic of oral cancer due to use of the betel quid substitutes gutkha and pan masala: a review of agents and causative mechanisms. Mutagenesis. 2004;19(4):251–262. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geh036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas S, Kearsley J. Betel quid and oral cancer: a review. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1993;29B(4):251–255. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(93)90044-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ko YC, et al. Betel quid chewing, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption related to oral cancer in Taiwan. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24(10):450–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1995.tb01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murti PR, et al. Malignant transformation rate in oral submucous fibrosis over a 17-year period. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1985;13(6):340–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1985.tb00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pindborg JJ, Sirsat SM. Oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology. 1966;22(6):764–779. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(66)90367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee CH, et al. The precancer risk of betel quid chewing, tobacco use and alcohol consumption in oral leukoplakia and oral submucous fibrosis in southern Taiwan. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(3):366–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghani WM, et al. Factors affecting commencement and cessation of betel quid chewing behaviour in Malaysian adults. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]