ABSTRACT

BGLF4 kinase, the only Ser/Thr protein kinase encoded by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) genome, phosphorylates multiple viral and cellular substrates to optimize the cellular environment for viral DNA replication and the nuclear egress of nucleocapsids. Previously, we found that nuclear targeting of BGLF4 is through direct interaction with the FG repeat-containing nucleoporins (FG-Nups) Nup62 and Nup153 independently of cytosolic transport factors. Here, we investigated the regulatory effects of BGLF4 on the structure and biological functions of the nuclear pore complex (NPC). In EBV-positive NA cells, the distribution of FG-Nups was modified during EBV reactivation. In transfected cells, BGLF4 changed the staining pattern of Nup62 and Nup153 in a kinase activity-dependent manner. Detection with anti-phospho-Ser/Thr-Pro MPM-2 antibody demonstrated that BGLF4 induced the phosphorylation of Nup62 and Nup153. The nuclear targeting of importin β was attenuated in the presence of BGLF4, leading to inhibition of canonical nuclear localization signal (NLS)-mediated nuclear import. An in vitro nuclear import assay revealed that BGLF4 induced the nuclear import of larger molecules. Notably, we found that BGLF4 promoted the nuclear import of several non-NLS-containing EBV proteins, including the viral DNA-replicating enzymes BSLF1, BBLF2/3, and BBLF4 and the major capsid protein (VCA), in cotransfected cells. The data presented here suggest that BGLF4 interferes with the normal functions of Nup62 and Nup153 and preferentially helps the nuclear import of viral proteins for viral DNA replication and assembly. In addition, the nuclear import-promoting activity was found in cells expressing the BGLF4 homologs of another two gammaherpesviruses but not those from alpha- and betaherpesviruses.

IMPORTANCE During lytic replication, many EBV genome-encoded proteins need to be transported into the nucleus, not only for viral DNA replication but also for the assembly of nucleocapsids. Because nuclear pore complexes are effective gateways that control nucleocytoplasmic traffic, most EBV proteins without canonical NLSs are retained in the cytoplasm until they form complexes with their NLS-containing partners for nuclear targeting. In this study, we found that EBV BGLF4 protein kinase interacts with the Nup62 and Nup153 and induces the redistribution of FG-Nups. BGLF4 modulates the function of the NPC to inhibit the nuclear import of host NLS-containing proteins. Simultaneously, the nuclear import of non-NLS-containing EBV lytic proteins was enhanced, possibly through phosphorylation of Nup62 and Nup153, nuclear pore dilation, or microtubule reorganization. Overall, our data suggest that BGLF4-induced modification of nuclear pore transport may block nuclear targeting of cellular proteins and increase the import of viral proteins to promote viral lytic replication.

INTRODUCTION

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a ubiquitous gammaherpesvirus that infects most of the human population. EBV preferentially infects B cells and epithelial cells, resulting in asymptomatic mild infections or infectious mononucleosis in young adults. EBV is also highly associated with several malignant diseases, including various lymphomas and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (1). After primary infection, EBV becomes latent in the quiescent B cells of the host and can be reactivated periodically. When EBV switches from the latent state to lytic replication, the immediate early transactivators Rta and Zta are expressed first and sequentially turn on the cascade of viral gene expression to initiate lytic virus replication (2).

Like all herpesviruses, EBV genomes are replicated and packaged into nucleocapsids in the nuclei of the infected cells (3). The replication components need to be transported into the nucleus to enable viral DNA replication (4). Viral capsid proteins accumulate at the assembly site to form procapsids in the nucleus (5). However, many viral proteins with nuclear functions lack the canonical nuclear localization signal (NLS), and the mechanism of their nuclear import remains to be explored.

In eukaryotes, the nuclear envelope (NE), consisting of the outer nuclear membrane (ONM) and the inner nuclear membrane (INM), is composed of lipid bilayers and serves as the physical barrier between the nucleus and cytoplasm (6). The NE protects the genome from cytoplasmic insults and the attack of pathogens. Underlying the INM, the nuclear lamina supports the NE membrane, while the INM-integrated proteins SUN1 and SUN2 interact with the ONM protein nesprin in the perinuclear space to form a LINC (linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton) complex, which provides a direct connection between the nuclear lamina and the cytoskeleton (7). SUN1 and SUN2 also bind to lamin A and the INM protein emerin, likely to be critical in maintaining nuclear shape and integrity (8). Nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) embedded in the NE thus function as effective gates to regulate nuclear/cytoplasmic transport. Ions and molecules smaller than 39 nm are able to diffuse passively through the NPCs, but most molecules need to be actively transported through specific mechanisms (9, 10).

The NPC is an 8-fold-symmetrical structure which is composed of about 30 different proteins, known as nucleoporins (Nups) (11). Approximately one-third of the nucleoporins, collectively termed FG repeat-containing nucleoporins (FG-Nups), contain multiple copies of Phe-Gly motifs separated by hydrophilic residues (12). FG-Nups fill the central channel of the NPC, extending into the cytoplasmic and nucleoplasmic sides to interact with the nuclear transport receptors (NTRs) through their FG domains. The interaction between FG-Nups and NTRs is a critical step for the nuclear transport of macromolecules through the NPC (13). The classical NLS comprises a stretch of basic amino acids or a bipartite motif composed of two clusters of positively charged residues (14). NLS-containing proteins can bind to the nuclear transport adaptor importin α and form a complex with importin β and pass through NPCs through interaction with FG-Nups (15, 16). The nuclear transport processes is regulated by a small GTPase, Ran. RanGTP dissociates importin β from the importin α-importin β-NLS complex in the nucleus and recycles it to the cytoplasm for the next nuclear import process (14, 17).

Many viruses, including most DNA viruses and some RNA viruses, need nuclear resources for their replication. Although the NE is a strict cellular barrier and transport of molecules is tightly regulated by the NPCs, viruses must not only deliver their genomes but also transport necessary viral proteins into the nucleus for successful replication. Thus, viruses have evolved to modulate the NPCs to facilitate preferential material transport (18). For example, the well-studied RNA viruses poliovirus and rhinovirus disrupt nucleocytoplasmic trafficking control with cleavage of Nup62, Nup153, and Nup98 by the viral protease 2Apro (19–21). Cardiovirus infection results in Nup62 and Nup153 phosphorylation through hijacking of the cellular protein kinase extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38 (22–24). The modification of FG-Nups facilitates the noncanonical exchange of macromolecules between the nucleus and cytoplasm to benefit virus replication.

EBV BGLF4 is a virion-associated, proline-dependent serine/threonine protein kinase that is conserved in all herpesviruses (25, 26). BGLF4 phosphorylates several viral proteins at different stages of viral replication, including EBNA2, EBNA-LP, BMRF1, BZLF1, viral DNA replication enzyme, and viral structural components (27–31). As well as these viral proteins, BGLF4 phosphorylates a broad range of cellular proteins (32). For example, BGLF4 phosphorylates MCM4 to inhibit the MCM4-MCM6-MCM7 complex-associated DNA helicase, blocking cellular chromosomal DNA replication (33). BGLF4 also phosphorylates lamin A/C and causes the partial disassembly of the nuclear lamina to facilitate the nuclear egress of nucleocapsids (34). To counteract the host innate immune response, BGLF4 phosphorylates interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and the NF-κB coactivator UXT, to suppress the IRF3 signaling pathway, and downregulates NF-κB-mediated expression of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8 (35, 36). Moreover, BGLF4 induces retinoblastoma (RB) protein hyperphosphorylation and enhances phosphorylation of the DNA damage-responsive Ser612 on RB, indicating that BGLF4 induces a DNA damage signal that eventually interferes with host DNA synthesis and delays S-phase progression (37).

Previously, we reported that BGLF4 interacts directly with Nup62 and Nup153 for its nuclear translocation. Simultaneously, BGLF4 induces the dissociation of a portion of FG-Nups from the nuclear rim into the nucleus, revealed by confocal microscopy (38). In this study, we aimed to identify the mechanism involved in the structural and functional changes of the NPC during EBV replication. We show that BGLF4 induces the phosphorylation of Nup62 and Nup153 and dilates nuclear pores. In addition, BGLF4 promotes the nuclear import of individual components of the EBV DNA replication complex and the major capsid protein through a canonical NLS-independent pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transfection.

Akata is an EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma cell line (39) which is maintained in RPMI 1640 medium and can be reactivated for EBV replication by treatment with 0.5% anti-human IgG (ICN Pharmaceuticals). The HeLa cell line was derived from a human cervical carcinoma (ATCC-CCL-2). The NA cell line was derived from NPC-TW01 cells infected with recombinant EBV Akata (40). For EBV lytic cycle induction, NA cells were transfected with an Rta-expressing plasmid (pSG5-Rta; RTS15 is described in reference 90) for the times indicated below. VIT7 and KIT2 cells are vector control and BGLF4 kinase-inducible cells, respectively, that were derived from NPC-TW01 cells using a ViraPower T-REx lentiviral expression system (Invitrogen) to generate cells stably expressing the tetracycline (Tet) repressor in an NPC-TW01 cell background. The cells were transfected with pLenti4 or pLenti4-BGLF4 to establish tetracycline-regulated BGLF4-inducible cell lines and control cell lines (37). The selected clones were maintained in the presence of 250 μg/ml zeocin and 12.5 μg/ml blasticidin (Invitrogen). All the epithelial cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C with 5% CO2. DNA transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Plasmids.

Plasmids expressing wild-type (WT) BGLF4 kinase (pYPW17) and a kinase-dead BGLF4 mutant with a substitution of isoleucine for the catalytic lysine (K102I; pYPW20), were generated as described previously (26). The plasmid expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged BGLF4 (GFP-BGLF4) (pCPL4) was generated in a previous study (41). GFP-K102I was generated using a single-primer mutagenesis protocol with pCPL4 as the template (38). pGEX-2T-HA-PTAC97 (glutathione S-transferase [GST]-importin β) was a gift from Y. Yoneda (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). pEYFP-LacZ-NLS was kindly provided by M. Kawata (Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan). Flag-Nup62 and Flag-Nup153 expression plasmids (pCWC15 and pCWC16, respectively) were generated by cloning the PCR-amplified human Nup62 cDNA (GenBank accession number BC003663; a gift from J. Lu, Academia Sinica, Taiwan) or Nup153 cDNA (GenBank accession number BC052965; Origene) into the XhoI site of the pCMV-Tag2B vector (Stratagene). EBV replication components Myc-BSLF1 (primase; carried by plasmid pDH310), Myc-BBLF2/3 (primase-associated factor; carried by plasmid pDH318), and Myc-BBLF4 (helicase; carried by plasmid pPG14) (gifts from Diane S. Hayward, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) were generated in the background of the pSG5 vector with a Myc tag. Hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged major capsid protein VCA (HA-VCA) was a gift from S. T. Liu (Chang-Gung University, Taiwan) (42). Flag-tagged herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) UL13 (pTAG-UL13), human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) UL97 (pTAG-UL97), and murine herpesvirus 68 (MHV68) open reading frame 36 (ORF36; pTAG-ORF36) were kindly provided by S. Hwang and R. Sun (University of California, Los Angeles) (34).

Construction of BGLF4-knockout bacmid.

Construction of the BGLF4-knockout bacmid was performed on the basis of a previous protocol with slight modification (43). The 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of BGLF4 (B95.8 strain nucleotides 110037 to 111326) were amplified by PCR using primers LMRC819 (5′-CGCGGATCCATCTTTGAGGCCCTGAAAGCC-3′) and LMRC820 (5′-CGCGGATCCTACATAAACAAAACCTAAACGCT-3′). The PCR product was digested and cloned into the BglII site of pGS284 to generate pCWC15 (pGS284/BGLF4). Sequentially, the stop codon containing an SpeI site was mutated into pCWC15 between nucleotides 110049 and 110051 of the B95.8 genome by single-primer PCR mutagenesis (44) using primer LMRC818 (5′-CCGCAGCCATATTCACATCTTACTAGTTCAAATGGCTCGAGGGCCT-3′). The resulting plasmid, pCWC16 (pGS284/BGLF4stop), was electroporated into Escherichia coli strain GS111 for allelic exchange. The EBV bacmid p2089 (45) was electroporated into E. coli strain GS500 (recA+). For allelic exchange, conjugation was performed by cross-streaking strains GS500/p2089 and GS111/pCWC16 on LB agar at 37°C for 16 h, and recombinant bacmids were selected according to a previously described procedure (46). Mutagenesis of the stop codon in BGLF4 was determined by colony PCR using primers LMRC819 and LMRC820 and restriction enzyme digestion for the insertion of the SpeI site.

To select EBV bacmid-positive cell lines, NPC-TW01 cells (5 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in a 6-well culture dish and transfected with 7 μg of p2089 or p2089BGLF4stop using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 48 h posttransfection, cells were split into two 10-cm culture dishes and selected with hygromycin B (300 μg/ml) for 1 month. Four to 6 GFP-positive cell colonies were picked up to obtain pooled clones. The selected TW01/p2089 (WT) or TW01/p2089BGLF4stop (BGST 52-1-2) pooled clones were transfected with Rta and Zta to confirm successful lytic induction by Western blotting.

Immunoblotting and antibodies.

After transfection, cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche], 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4), resolved by electrophoresis in SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and transferred onto Protran nitrocellulose transfer membranes (PerkinElmer). The blots were blocked with washing buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% Tween 20) containing 5% skim milk at room temperature (RT) for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. After washing three times with washing buffer, the blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies at RT for 1 h. Finally, the blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer) and exposed to X-ray films. BGLF4 monoclonal antibody (MAb) 2616, recognizing epitopes within amino acids 327 to 429, was used for immunoblotting (26). Other primary antibodies used were poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP; F-2; Santa Cruz,), α-tubulin (Calbiochem), MAb414 (Abcam), Nup62 (BD Transduction Laboratories), Nup153 (Abcam), SUN1 (kindly provided by Ya-Hui Chi, National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan) (47), SUN2 (Gene Tax), emerin (catalog number FL-254; Santa Cruz), HA (Covance), Flag (catalog number M2; Sigma), histone H1 (Abcam), and Myc (MAb 9E10) (48) antibodies.

Immunofluorescence assay.

To detect NPC components and nuclear envelope-associated proteins in cells replicating EBV, slide-cultured NA cells were transfected with an Rta-expressing plasmid to induce virus replication. To examine the effect of BGLF4 on promoting the nuclear transport of viral proteins, HeLa cells were transfected with wild-type (WT) BGLF4 or the BGLF4 kinase-dead K102I mutant with plasmids expressing EBV lytic proteins. At 24 h posttransfection, slides were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for NPC staining at RT for 20 min, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 145 mM NaCl, 1.56 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2) at RT for 5 min, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (TNX-100) at RT for 5 min. BGLF4 was stained with monoclonal antibody 2616 or rabbit BGLF4 antiserum (26). For paclitaxel (Taxol; Bristol-Myers Squibb) treatment, EBV lytic proteins were expressed for 24 h and then the BGLF4-expressing plasmid or vector control was transfected. At 12 h posttransfection, paclitaxel (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 20 μg for another 12 h, and the calls were fixed for probing with antibodies. For NPC staining, cells were incubated with antibody specific for MAb414, Nup62, Nup153, SUN1, SUN2, emerin, or RanGAP1 (catalog number C-5; Santa Cruz). To detect HA-VCA or Myc-BSLF1, Myc-BBLF2/3, and Myc-BBLF4 expression, the cells were incubated with anti-HA (Covance) or anti-Myc antibody, respectively, at RT for 1.5 h. Anti-Flag (catalog number M2; Sigma) and anti-HA (catalog number GTX29110; GeneTex) were used for herpesviral UL kinase staining. After washing with PBS, the slides were incubated with rhodamine-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Cappel) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Cappel) for another 1 h. DNA was stained with Hoechst 33258 at RT, and the cells were covered with mounting medium (catalog number H-1000; Vector). The staining patterns were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Axioskop 40 FL; Zeiss) or by confocal microscopy (LSM 780; Zeiss).

IP kinase assay.

HeLa cell lysates were harvested and immunoprecipitated with MAb414 or Nup62 antibody, and the pulled down immunocomplexes served as the substrates for immunoprecipitation (IP) kinase assays. Purified BGLF4 linked to GST (GST-BGLF4) or the BGLF4 K102I mutant linked to GST (GST-K102I) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast (38) was incubated with the immunoprecipitated proteins in the presence of 10 μCi [γ-32P]ATP and kinase buffer (20 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 10 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM Na3VO4, 100 μM ATP) at 37°C for 1 h. To stop the reaction, 4× SDS sample buffer was added and the reaction mixtures were boiled for 5 min. After the proteins were resolved in 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, the gels were dried, subjected to autoradiography, and transferred onto Protran nitrocellulose transfer membranes (PerkinElmer), and anti-BGLF4 antibody 2616 and MAb414 antibody were detected by immunoblotting.

Nuclear envelope fractionation.

Nuclear envelope fractionation was performed as described previously with slight modifications (38, 49). To isolate nuclei, HeLa cells (3 × 106) transfected with BGLF4, the BGLF4 kinase-dead K102I mutant, or the vector control were incubated with 700 μl hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris HCl, pH 8, 60 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]) on ice for 1.5 h. After centrifugation at 200 × g for 5 min, the pellet was harvested as the nuclear fraction. The resultant pellet with intact nuclei was washed twice with hypotonic buffer and frozen rapidly at −80°C overnight.

The frozen nuclei were thawed rapidly by placing the tubes in a 30°C water bath and then centrifuged at 500 × g for 1 min at 4°C. The resultant nuclear pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of buffer A with DNase and RNase (0.1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1× protease inhibitor, 5 μg/ml DNase I, 5 μg/ml RNase A) at 37°C for 1 h to disrupt the nuclei and remove the nuclear membrane-associated DNA and RNA. The reaction mixtures were then incubated with 4 ml of buffer B (0.1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, 10% sucrose, 20 mM triethanolamine, pH 8.5, 1× protease inhibitor) at RT for 15 min and then 4 ml of buffer C (sucrose cushion solution, 0.1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, 30% sucrose, 20 mM triethanolamine, pH 7.5, 1× protease inhibitor) and centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was the nucleoplasm (NP) fraction, and the pellet was the crude nuclear envelope (NE) fraction.

Cell permeabilization and in vitro nuclear import assay.

Nuclear import assays were performed on the basis of a previously described protocol with slight modification (38, 50). For the nuclear import of GST-importin β, HeLa cells expressing BGLF4, the BGLF4 kinase-dead K102I mutant, or the vector control were grown on slides and permeabilized at RT with 40 μg/ml digitonin (Sigma) in transport buffer (TB; 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, 110 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 1× protease inhibitor) for 5 min, followed by 5 min on ice, and washed with ice-cold TB twice. Nuclear import assays were performed with 0.5 to 1 μM GST–importin β alone at RT for 1 h. After washing with TB twice to stop the reaction, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and subjected to immunofluorescence assay with rabbit BGLF4 antiserum and anti-GST antibody. For the in vitro nuclear import of dextran, slide-cultured HeLa cells were transfected with the GFP-BGLF4, GFP-K102I, or GFP control plasmid for 24 h. After digitonin permeabilization, 4.4- or 70-kDa tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate (TRITC)-dextran (Sigma) mixed with 75% (vol/vol) cytosol factors (10% rabbit reticulocyte lysate, 0.5 mM ATP, 0.5 mM GTP, 10 mM creatine phosphate, 30 U/ml creatine phosphokinase) was added onto the slides at RT for 1 h. After washing and fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, the cells were observed by confocal microscopy. For the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-LacZ-NLS import assay, VIT7 and KIT2 cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or doxycycline to induce BGLF4 expression. After 24 h treatment, YFP-LacZ-NLS was expressed for another 24 h and the cells were fixed and stained for BGLF4 antibody 2224.

Coimmunoprecipitation assay.

Cells were harvested at 24 h posttransfection and disrupted in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The cell lysates were separated by centrifugation for 10 min at 16,000 × g, and the supernatant was precleared by incubation with protein A-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) and rotation at 4°C for 1 h and then reacted with BGLF4 MAb 2224 at 4°C for 2 h. Protein A-Sepharose beads (100 μl at 20%) were added to pull down the immunocomplexes with rotation for 1 h at 4°C. Immunocomplexes were collected by centrifugation, washed extensively with NP-40 buffer, and detected by immunoblotting. The membranes were blocked, probed with various antibodies, and developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (PerkinElmer).

TEM.

HeLa cells (3 × 105) were transfected with a plasmid expressing BGLF4 or control vector pSG5 for 24 h and processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis (at the Joint Center for Instruments and Researches, College of Bioresources and Agriculture, NTU). Briefly, the cells were trypsinized, pelleted, and washed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The pellets were rinsed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 3 h at RT. The cells were washed and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h at RT. The samples were dehydrated with increasing concentrations of ethanol from 35 to 100% and then infiltrated with ethanol-resin at 3:1 for 90 min, ethanol-resin at 1:1 for 90 min, ethanol-resin at 1:3 for 120 min, and then pure resin for overnight. The samples were embedded at 70°C for 15 h prior to sectioning for TEM. The embedded samples were cut into 70-nm-thick sections, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and imaged using a JEOL JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope. The images were acquired using an AMT camera system (at the Joint Center for Instruments and Researches, College of Bioresources and Agriculture, NTU).

RESULTS

Nuclear envelope-associated proteins are irregularly distributed in NA cells during EBV reactivation.

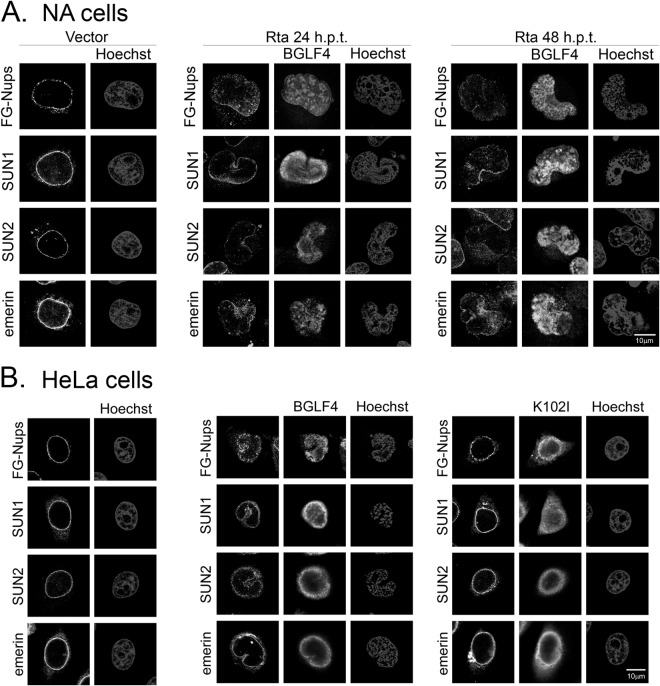

Previously, we reported that expression of BGLF4 induces partial disassembly of the nuclear lamina and the intranuclear redistribution of FG-Nups in transiently transfected HeLa cells. Similar nuclear structural changes also were observed in the Akata EBV-converted NPC-TW01 cell line NA after transfection of Rta (34, 38). Because the nuclear lamina plays an important role in the correct distribution of other nuclear envelope-associated components and NPCs are the gatekeepers for nuclear and cytoplasmic transport, we were prompted to examine how EBV lytic replication affects the nuclear architecture and the distribution of nuclear envelope-associated proteins. We transfected a plasmid expressing Rta to induce lytic EBV replication in NA cells and monitored the distribution of nuclear envelope-associated proteins, including FG-Nups, the inner nuclear membrane-associated protein emerin, and the inner nuclear membrane-associated proteins SUN1 and SUN2 that form trimers binding to KASH domain proteins to function as a nuclear membrane spacer. Compared to the findings for vector-transfected cells, FG-Nups, detected by MAb414 antibody, displayed intranuclear staining at 24 h and were distributed to the perinuclear region at 48 h after Rta transfection. Similarly, SUN1, SUN2, and emerin seemed to disassociate from the nuclear rim at 24 and 48 h posttransfection with Rta (Fig. 1A). Notably, all these nuclear envelope-associated proteins were enriched at the perinuclear concave region, which is possibly the cytoplasmic assembly compartment. Immunoblotting revealed that the amounts of individual nuclear envelope-associated proteins did not change significantly after EBV reactivation (data not shown), suggesting that EBV modulates the distribution but not the expression levels of nuclear envelope-associated proteins.

FIG 1.

EBV reactivation and BGLF4 expression induce the redistribution of nuclear envelope-associated proteins. (A) NA cells were transfected with an Rta expression plasmid to induce EBV reactivation. The cells were harvested at different time points after Rta transfection (hours posttransfection [h.p.t.]), fixed, and stained for BGLF4 (FITC), nuclear envelope-associated proteins (rhodamine), and DNA using BGLF4 MAb 2224 together with SUN1, SUN2, or emerin antibody, BGLF4 rabbit antiserum together with MAb414 (which recognize FG-Nups), and Hoechst 33258, respectively. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids expressing wild-type BGLF4, the BGLF4 kinase-dead K102I mutant, or the vector control. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were fixed and stained for BGLF4, nuclear envelope-associated proteins, and DNA as described in the legend to panel A. All the images were produced by confocal microscopy (Zeiss).

BGLF4 kinase modifies the nuclear envelope structure and induces the redistribution of nuclear envelope-associated proteins.

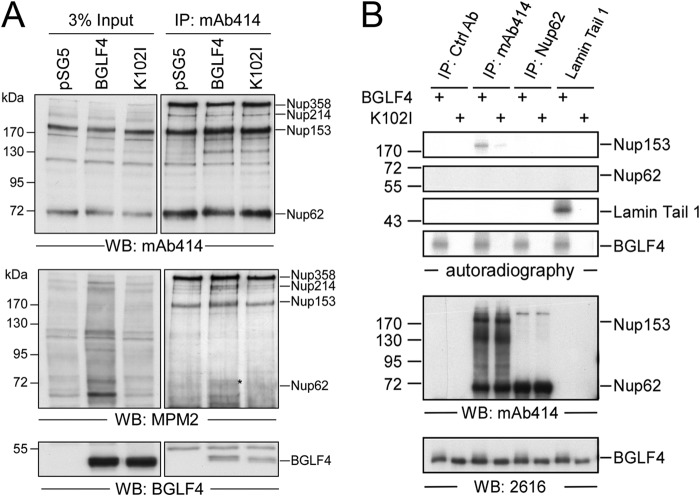

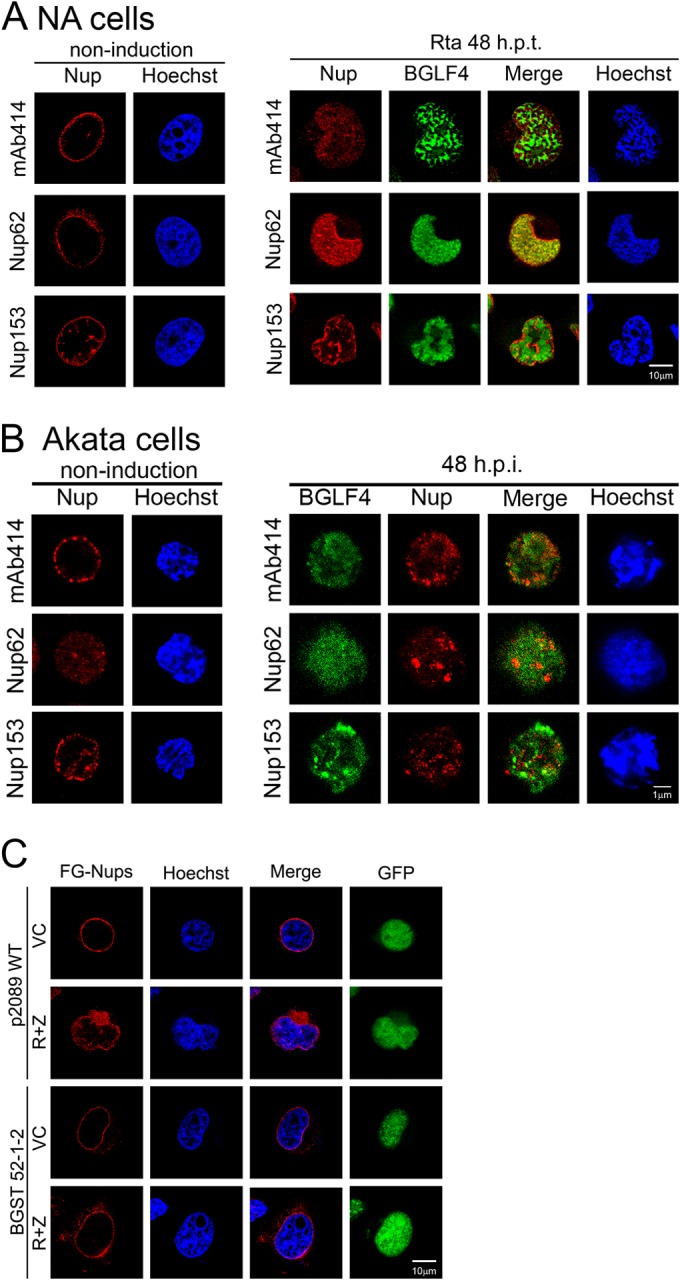

Because BGLF4 induces nuclear morphological changes and the redistribution of FG-Nups (38), we wondered whether BGLF4 contributes to the redistribution of nuclear envelope-associated proteins in cells in which EBV is replicating. To this end, HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids expressing BGLF4, the BGLF4 kinase-dead K102I mutant, or the vector control, and the expression pattern of nuclear envelope-associated proteins was examined. As expected, the protein expression levels did not change significantly (data not shown). As well as the FG-Nups, BGLF4 induced the partial disassociation of SUN1 and SUN2 from the nuclear envelope, coupled with a concave nuclear envelope structure at the perinuclear space which was not observed by immunofluorescence in the BGLF4 kinase-dead K102I mutant- or vector control-transfected cells (Fig. 1B). The staining pattern of emerin in BGLF4-expressing cells was also slightly modified (Fig. 1B, middle). It is not surprising that the BGLF4-induced patterns differed from those observed in NA cells containing replicating EBV, because other viral lytic proteins may also contribute to modulating the nuclear envelope structure. Indeed, our recent study also showed that BFRF1 alone induces nuclear envelope-derived vesicle formation (51). Because BGLF4 interacts with and may be immunoprecipitated with Nup62 and Nup153 (38), we examined how EBV replication affects the distribution of Nup62 and Nup153. Slide-cultured NA cells were induced to lytic replication by transfection of an Rta expression plasmid, harvested, and fixed at 0, 24, 36, 48, and 60 h posttransfection. As expected, FG-Nups were detected in the nucleus using MAb414 antibody. With specific antibodies in confocal microscopy, we found that Nup62 and Nup153 were redistributed from the nuclear rim, partly diffused into the nucleus, and enriched at the margin of the nuclear concave region at 48 h posttransfection (Fig. 2A). To examine whether similar phenomena can be observed in B cells in which EBV is reactivated, the EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) cell line Akata was induced by IgG cross-linking and analyzed by immunofluorescence and confocal imaging. Different from what was observed in epithelial cells, we found that small portions of Nup62 and Nup153 were distributed within the nucleus in Akata cells before induction. After induction, FG-Nups, including Nup62 and Nup153, appeared to be disorganized and form small speckles in the nucleus of Akata cells at 48 h postinduction (h.p.i.) (Fig. 2B). To examine whether BGLF4 is involved in the nuclear redistribution of FG-Nups, the p2089BGLF4stop EBV bacmid was constructed by an allelic exchange procedure (52). A second start codon (amino acid 5) of BGLF4 was mutated into stop codons, and the incorporation of the cassette in BGLF4 was confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion of the inserted HindIII site next to the stop codon (data not shown). Wild-type and p2089BGLF4stop bacmids were transfected into TW01 cells to establish TW01/p2089 (p2089 WT) and TW01/p2089BGLF4stop (BGST) stable clones. We found that the FG-Nups were redistributed into the nucleus and clustered at the juxtanuclear concave region at 48 h after Rta and Zta cotransfection in p2089 WT cells but not in BGST cells which did not express BGLF4 (Fig. 2C). To determine whether BGLF4 regulates Nup62 and Nup153 redistribution directly, HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids expressing BGLF4, the BGLF4 kinase-dead K102I mutant, or the vector control, and the distribution of FG-Nups was examined. A proportion of FG-Nups was detected in the nucleus in HeLa cells transfected with BGLF4 (Fig. 3B) but not in HeLa cells transfected with the vector (Fig. 3A) or the K102I mutant (Fig. 3C), indicating that BGLF4 induces the redistribution of the FG-Nups in a kinase activity-dependent manner. The cross-sectional confocal images show that Nup62 and Nup153 are still associated with the nuclear envelope. In addition, nuclear envelope fractionation was performed to examine the partitioning of Nup62 and Nup153 in the cytoplasmic, nucleoplasmic (NP), and nuclear envelope (NE) fractions. The immunoblotting indicated that BGLF4 induced only a small increase (1.25%) of Nup62 in the nucleoplasm (Fig. 3D, lane 7); however, this increase was very close to that seen in BGLF4 K102I mutant-expressing cells (Fig. 3D, lane 11). These data suggest that BGLF4 induced structural changes in the nuclear envelope and most of the redistributed FG-Nups detected by immunofluorescence assay may still be associated with the nuclear envelope.

FIG 2.

Redistribution of FG-Nups in cells in which EBV was reactivated. (A) Slide-cultured NA cells were transfected with an Rta-expressing plasmid to induce EBV reactivation and harvested before induction (noninduction) and at 48 h posttransfection; the cells were then fixed and stained for BGLF4, MAb414, Nup62, Nup153, and DNA. (B) Akata cells were induced to enter the lytic cycle by IgG cross-linking and harvested at 0 and 48 h postinduction (h.p.i.). Cells were fixed and stained for BGLF4, MAb414, Nup62, Nup153, and DNA, using BGLF4 rabbit antiserum; MAb414, Nup62, and Nup153 antibodies; and Hoechst 33258, respectively. (C) TW01/p2089 (WT) or TW01/p2089BGLF4stop (BGST 52-1-2) pooled clones were cotransfected with plasmids expressing Rta and Zta (R+Z) or the vector control to induce EBV lytic replication and harvested at 48 h posttransfection. Cells were fixed and stained for MAb414. The distribution of BGLF4 and nucleoporins was observed by confocal microscopy.

FIG 3.

BGLF4 but not the BGLF4 K102I mutant induces the redistribution of FG-Nups. Slide-cultured HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids expressing wild-type BGLF4 (B), the BGLF4 kinase-dead K102I mutant (C), or the vector control (A). At 24 h posttransfection, cells were fixed and stained for BGLF4, MAb414, Nup62, Nup153, and DNA. The staining patterns of BGLF4 and nucleoporins were observed by confocal microscopy. Cross-sectional images of BGLF4-expressing cells are shown next to the confocal images (B). (D) Nuclear envelope fractionation of HeLa cells expressing BGLF4, the K102I mutant, or the vector control. Histone H1 and α-tubulin serve as markers of the nucleoplasm and cytoplasm, respectively. T, total; C, cytoplasm; NP, nucleoplasm; NE, nuclear envelope; WB, Western blotting.

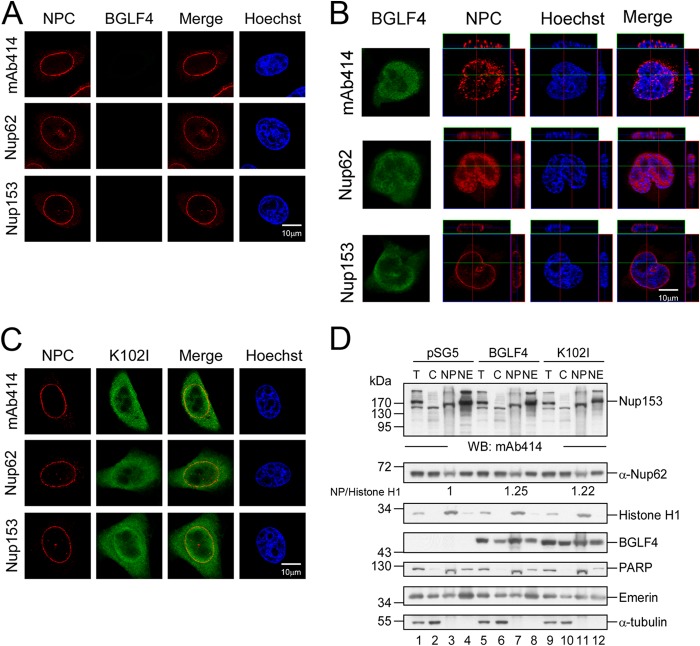

BGLF4 induces the phosphorylation of nucleoporins.

To investigate the mechanism involved in BGLF4-induced redistribution, FG-Nups from BGLF4- or BGLF4 K102I mutant-transfected HeLa cells were enriched by immunoprecipitation with MAb414 and detected with MPM2 antibody, which specifically recognizes the proline-dependent Ser/Thr phosphorylation (Ser/Thr-Pro) induced by BGLF4. We found that the phosphorylation signals on Nup153 were slightly enhanced in the presence of BGLF4 compared to those observed in cells transfected with the vector control and the K102I mutant, and a weak phosphorylation signal was observed on Nup62. An in vitro immunocomplex kinase assay was further used to determine whether BGLF4 phosphorylates FG-Nups directly. FG-Nups were immunoprecipitated from HeLa cells using MAb414 or Nup62 antibody and incubated with [γ-32P]ATP and purified yeast recombinant GST-BGLF4 kinase or GST-K102I in kinase reaction buffer, and the reaction products were detected by electrophoresis and autoradiography. Phosphorylation of Nup153 was detected in the in vitro kinase assay, suggesting that BGLF4 phosphorylates Nup153 directly. However, phosphorylation of Nup62 was not detected in the in vitro immunocomplex kinase assay (Fig. 4B), suggesting that cellular kinases may be involved in its phosphorylation or that the Nup62 in the immunocomplexes might not be a suitable substrate in the in vitro kinase assay.

FIG 4.

FG-Nups were phosphorylated by BGLF4 in vivo and in vitro. (A) Lysates harvested from HeLa cells transfected with plasmids expressing BGLF4, the K102I mutant, or the vector control were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation assay. Protein complexes were immunoprecipitated with MAb414 to pull down FG-Nups, including Nup358, Nup214, Nup62, and Nup153. The immunocomplexes were detected by immunoblotting using phosphorylated Ser/Thr-Pro-specific antibody MPM2 and BGLF4-specific MAb 2616 or MAb414. *, phosphorylated Nup62. (B) An in vitro kinase assay was performed with HeLa cell lysates immunoprecipitated with MAb414 or Nup62 antibody as the substrates. Phosphorylation was measured by incubation of yeast purified GST-BGLF4 or GST-K102I and [γ-32P]ATP in kinase reaction buffer. The phosphorylation signals were detected by autoradiography. Proteins in the kinase reaction were detected by BGLF4 MAb 2616 and MAb414 in immunoblots. Ctrl Ab, control antibody.

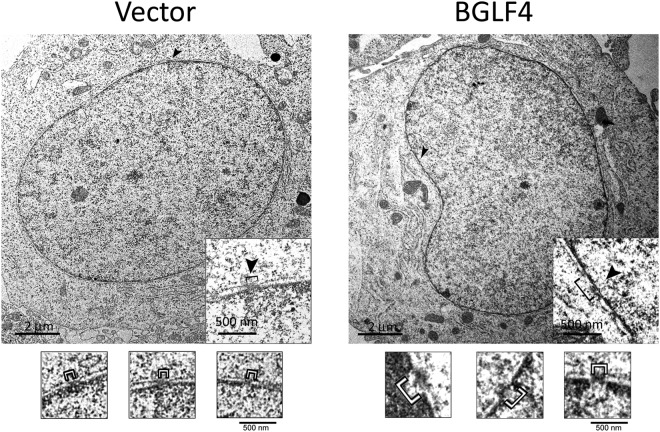

Nuclear pores are enlarged in HeLa cells expressing BGLF4.

Nup62 is located at the center of the nuclear pore, and Nup153 is located in the inner ring of the NPC. To investigate further the possible alteration of nuclear pores caused by BGLF4, nuclear envelope structures from HeLa cells expressing BGLF4 were examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Images of the nuclear envelope revealed distinct gap structures in BGLF4-expressing cells, especially at the juxtanuclear concave regions. By measuring 10 pores each in 5 transfected cells, gaps of 107.61 ± 16.04 nm were measured in vector-transfected cells, whereas gaps of 244.35 ± 54.89 nm were observed in cells expressing BGLF4 (Fig. 5). This suggests that the nuclear pores were dilated in the presence of BGLF4, possibly through a phosphorylation-mediated mechanism.

FIG 5.

TEM analysis of the BGLF4-induced redistribution of NPC. HeLa cells were transfected with the control vector or the BGLF4 expression plasmid. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were fixed and processed for TEM as described in Materials and Methods. More than 10 pores in 5 transfected cells were observed in each set, and representative nuclear and cytoplasmic regions of transfected cells are shown. Arrowheads, the pore in the nuclear envelope. Gaps near the nuclear concave regions (identified by brackets) were measured to be 244.35 ± 54.89 nm in BGLF4-transfected cells, while they were 107.61 ± 16.04 nm in vector-transfected cells. Magnifications, ×20,000.

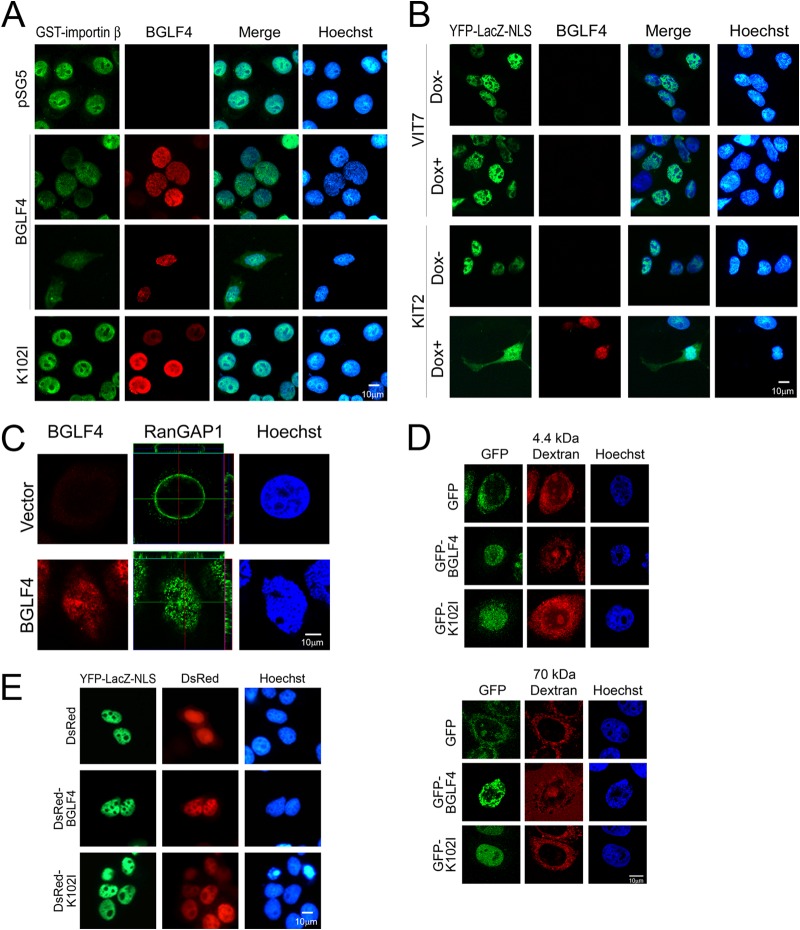

BGLF4 inhibits the nuclear import of importin β and canonical NLS-mediated nuclear transport pathways.

Located at the center of the nuclear pore, Nup62 serves as a major barrier for molecular transport between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Nup153 is important for nuclear pore complex assembly and nuclear envelope formation. An in vitro nuclear import assay was used to examine the effects of BGLF4-mediated phosphorylation of the FG-Nups on the nucleocytoplasmic transport pathways. To this end, purified recombinant bacterial GST-importin β was incubated with digitonin-permeabilized HeLa cells expressing BGLF4, the BGLF4 K102I mutant, or the vector control. Immunofluorescence staining indicated that the nuclear accumulation of GST-importin β was significantly reduced in HeLa cells expressing BGLF4, whereas the nuclear targeting of GST-importin β in cells expressing the BGLF4 K102I mutant was efficient (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, we tested the influence of BGLF4 on NLS-mediated nuclear transport in NPC-TW01 cells expressing Tet-on BGLF4 (KIT2 cells) and vector-transfected control cells (VIT7 cells). The nuclear targeting of YFP-LacZ-NLS in VIT7 cells was not affected by doxycycline treatment, whereas the induction of BGLF4 expression in KIT2 cells caused the cytoplasmic retention of a proportion of YFP-LacZ-NLS, suggesting the BGLF4-induced inhibition of the canonical NLS-mediated nuclear transport (Fig. 6B). The nuclear import of classical NLS-containing proteins depends not only on the interaction of importin αβ complexes with FG-Nups but also on the hydrolysis of GTP on the small GTP-binding protein Ran. We then detected nuclear envelope-associated RanGAP1, which plays an important role in regulating RanGTP density, by immunofluorescence staining and confocal imaging of HeLa cells expressing BGLF4. The data indicate that NE-associated RanGAP1 was partially redistributed into the nucleus of BGLF4-expressing HeLa cells (Fig. 6C). Taken together, BGLF4 not only induced the redistribution of Nup62 and Nup153 but also promoted RanGAP1 reorganization to interfere with classical NLS-dependent nuclear import.

FIG 6.

Nuclear transport of canonical NLS-containing proteins and gating of the NPC were impaired in BGLF4-expressing cells. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with vector control-, BGLF4-, or BGLF4 K102I mutant-expressing plasmids. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were permeabilized with digitonin and incubated with purified GST-importin β in the absence of other transport factors. After 1 h of incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% TNX-100. BGLF4 and the BGLF4 K102I mutant were detected using BGLF4 MAb 2224, and GST-importin β was detected with anti-GST antibodies. (B) Slide-cultured VIT7 and KIT2 cells, which are NPC-TW01 Tat-containing vector control and BGLF4 kinase-inducible cells, respectively, were treated with doxycycline (Dox) to induce BGLF4 expression. At 24 h postinduction, the cells were transfected with a YFP-LacZ-NLS-expressing plasmid. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were fixed and stained for BGLF4 and DNA with BGLF4 MAb 2224 and Hoechst 33258, respectively. (C) A BGLF4-expressing plasmid or vector control was transfected into HeLa cells. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were fixed; stained for BGLF4 and RanGAP1 with BGLF4 rabbit antiserum and RanGAP1 antibody, respectively; and observed by confocal microscopy. The cross-sectional images of RanGAP1 are shown next to the confocal images. (D) HeLa cells were transfected with a GFP-, GFP-BGLF4-, or GFP-K102I-expressing plasmid. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were permeabilized with digitonin and incubated with 4.4-kDa or 70-kDa TRITC-dextran in the presence of an energy-regenerating (reticulocyte lysate) system for 1 h. Cells were imaged by confocal microscopy. (E) Slide-cultured HeLa cells were transfected with YFP-LacZ-NLS, followed by expression for 24 h and transfection of DsRed-BGLF4, DsRed-K102I, or the DsRed vector. The cells were fixed, stained for DNA with Hoechst 33258, and detected by immunofluorescence microscopy.

The permeability barrier of the nuclear envelope is partially impaired by BGLF4.

Under normal physiological conditions, NPC restricts molecules larger than 40 kDa from passively diffusing between the nucleus and cytoplasm through its gating activity. To determine whether the permeability of the NPC was affected by BGLF4, GFP-BGLF4, GFP-K102I, or the GFP vector was expressed in HeLa cells, and the cells were permeabilized with digitonin and incubated with 4.4-kDa or 70-kDa TRITC-dextran. In the presence of GFP, 4.4-kDa dextran was distributed in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. In contrast, 70-kDa dextran was detected only in the cytoplasm of GFP- and GFP-K102I-expressing cells. Notably, 70-kDa dextran leaked into the nucleus of approximately 66% of GFP-BGLF4-expressing cells (Fig. 6D), suggesting that the permeability barrier of NPC was partially impaired by BGLF4.

We asked also whether BGLF4 causes intranuclear proteins to leak into the cytoplasm. To this end, a plasmid expressing YFP-LacZ-NLS was transfected into HeLa cells for 24 h before transfection with BGLF4 linked to DsRed (DsRed-BGLF4). At 24 h after BGLF4 transfection, the cells were harvested, fixed, and examined by immunofluorescence microscopy. Compared to the nuclear distribution of YFP-LacZ-NLS in the BGLF4 K102I mutant linked to DsRed (DsRed-K102I)- or DsRed vector-transfected cells, the nuclear distribution of YFP-LacZ-NLS was not obviously altered in BGLF4-transfected cells (Fig. 6E). The data presented here suggest that BGLF4 interferes with classical NLS-mediated nuclear import but does not induce the leakage of intranuclear proteins into the cytoplasm.

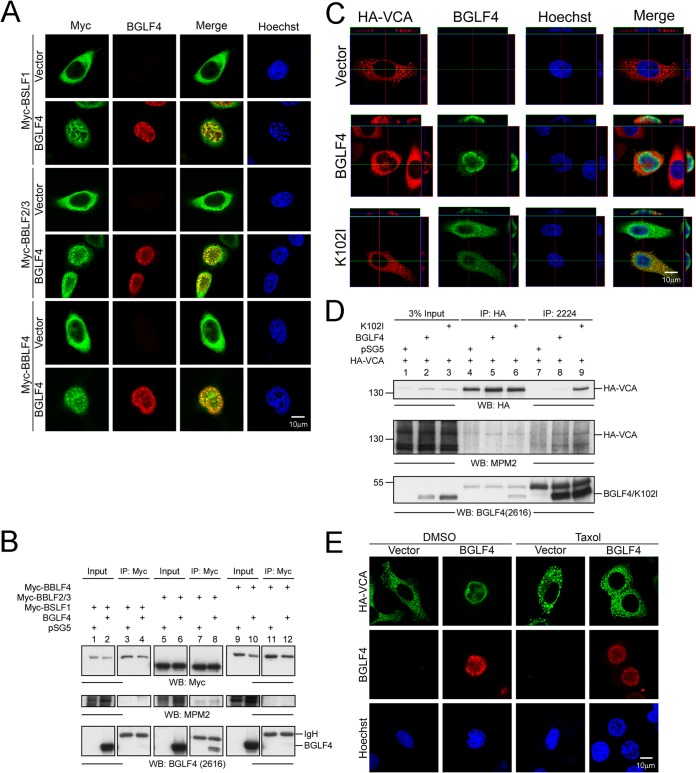

BGLF4 promotes the nuclear transport of EBV lytic proteins.

Many herpesviral proteins that function in the nucleus do not contain a canonical NLS and were suggested to be transported into the nucleus through interaction with other NLS-containing viral proteins. For example, EBV early proteins that participate in viral DNA replication, including BSLF1 primase, BBLF2/3 primase-associated factor, and BBLF4 helicase, were expressed in the cytoplasm and transported into the nucleus through interaction with EBV immediate early transactivator Zta in transiently transfected cells (53). To determine whether the BGLF4-induced NPC permeability changes may benefit the nuclear transport of these viral proteins, BSLF1, BBLF2/3, and BBLF4 were expressed together with BGLF4. When expressed alone, these EBV replication components were distributed predominantly in the cytoplasm, although complex formations of different components were found to promote nuclear transport (53, 54). Here, immunofluorescence staining and confocal images showed that approximately 54% (46/85), 73% (68/93), and 63% (67/106) of cells expressing Myc-BSLF1, Myc-BBLF2/3, and Myc-BBLF4, respectively, showed a nuclear distribution in the presence of BGLF4, whereas in the absence of BGLF4, less than 5% of cells showed nuclear staining (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, the staining patterns of these cells showed a distinct nuclear distribution without cytoplasmic retention, which is very different from the pattern seen with the in vitro transport of the 70-kDa dextran, where only a small proportion was translocated into the nucleus (Fig. 6D). This suggests that specific regulation, rather than nonspecific diffusion through dilated nuclear pores, is involved in the BGLF4-mediated nuclear transport of these proteins. To determine whether EBV replication proteins form complexes with BGLF4 to promote their nuclear import, a coimmunoprecipitation assay was performed with Myc antibody, and the immunocomplexes were detected with BGLF4 monoclonal antibody. The results showed that only Myc-BBLF2/3 pulled down BGLF4, suggesting that BBL2/3 may be translocated into the nucleus by binding to BGLF4 (Fig. 7B, lane 8). Simultaneously, the MPM2 antibody was also used to detect the Ser/Thr-Pro phosphorylation status of these proteins. BBLF4, but not BSLF1 or BBLF2/3, was identified as a substrate of BGLF4 in a protein array analysis (31). Here we also detected the Ser/Thr-Pro phosphorylation of BBLF2/3; however, its signal was not enhanced by coexpression of BGLF4 (Fig. 7B, middle, lanes 7 and 8). No phosphorylated Ser/Thr-Pro signals were detected on BSLF1 or BBLF4, suggesting that these proteins may not be imported into the nucleus through a direct, phosphorylation-dependent mechanism.

FIG 7.

BGLF4 promotes nuclear import of EBV early and late proteins. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with Myc-BSLF1-, Myc-BBLF2/3-, or Myc-BBLF4-expressing plasmids. At 24 h posttransfection, the BGLF4-expressing plasmid or vector control was retransfected. At 24 h after the second transfection, the cells were fixed and stained for BGLF4 with BGLF4 rabbit antiserum, Myc-BSLF1, Myc-BBLF2/3, and Myc-BBLF4 with anti-Myc antibody, and DNA with Hoechst 33258. (B) Lysates from HeLa cells expressing BGLF4 and EBV DNA replication components were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody. The immunocomplexes was detected by Western blotting using anti-Myc antibody, antibody MPM2, or BGLF4 MAb 2616. (C) Slide-cultured HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids expressing BGLF4, the BGLF4 K102I mutant, or the vector control and HA-VCA-expressing plasmids. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were fixed and stained for BGLF4, HA-VCA, and DNA with BGLF4 rabbit antiserum, anti-HA antibody, and Hoechst 33258, respectively. The distributions of BGLF4 and VCA were observed by confocal microscopy and the use of cross-sectional images. (D) HeLa cells were transfected with HA-VCA together with plasmids expressing BGLF4, the BGLF4 K102I mutant, or the vector. At 24 posttransfection, the cells were harvested and immunoprecipitated using anti-HA antibody or BGLF4 MAb 2224. The immunocomplexes were detected using anti-HA, MPM2, and BGLF4 2616 antibodies. (E) Slide-cultured HeLa cells were transfected with HA-VCA expression plasmids. After 24 h of incubation, the BGLF4- or vector-expressing plasmid was transfected into the cells. At 12 h posttransfection, 20 μM paclitaxel or DMSO was added and the mixture was incubated for another 12 h. Cells were fixed and stained for BGLF4, HA-VCA, and DNA with BGLF4 rabbit antiserum, anti-HA antibody, and Hoechst 33258, respectively.

Because the six EBV capsid proteins need to be accumulated at the assembly site in the nucleus to form precapsids for encapsidation of viral genomes (5), we investigated whether BGLF4 also promotes the nuclear import of VCA, which is the major capsid protein and is expressed predominantly in the cytoplasm in transfected cells. The confocal images and the cross sections showed that VCA was partially transported into the nucleus in the presence of BGLF4 but not in the presence of the BGLF4 K102I mutant (Fig. 7C), suggesting that the kinase activity of BGLF4 is required for the nuclear import of HA-VCA. Unlike the nuclear targeting staining patterns shown in Fig. 7A, HA-VCA was enriched at the perinuclear rim, and a proportion of VCA was concentrated at the concave region and appeared to leak into the nucleus, as indicated by confocal cross-section images. Notably, we found that HA-VCA interacted with the BGLF4 kinase-dead K102I mutant in coimmunoprecipitation assays and colocalized with the BGLF4 K102I mutant in the cytoplasm of transfected cells. However, no interaction between HA-VCA and wild-type BGLF4 was observed (Fig. 7C and D). In our previous study, BGLF4 was found to induce the rearrangement of the cytoskeleton (41), and HA-VCA seems to be distributed alongside α-tubulin, according to the findings obtained by confocal microscopy (data not shown). We examined whether microtubule reorganization is involved in the BGLF4-induced nuclear import of HA-VCA using paclitaxel to stabilize the microtubules. To this end, HA-VCA was expressed for 24 h in HeLa cells before transfection of the BGLF4 plasmid. At 12 h after BGLF4 transfection, the cells were treated with paclitaxel for a further 12 h. The confocal images showed that paclitaxel treatment appeared to inhibit the BGLF4-mediated nuclear import of VCA, suggesting that microtubule reorganization is involved in the BGLF4-mediated nuclear import of VCA (Fig. 7E). However, the nuclear import of Myc-BSLF1, BBLF2/3, and BBLF4 was not affected by paclitaxel treatment (data not shown), suggesting that nuclear import of these components was independent of microtubule reorganization. Taken together, these results indicate that BGLF4 inhibits host NLS-dependent nucleocytoplasmic transport and promotes the nuclear import of viral proteins, possibly through multiple pathways.

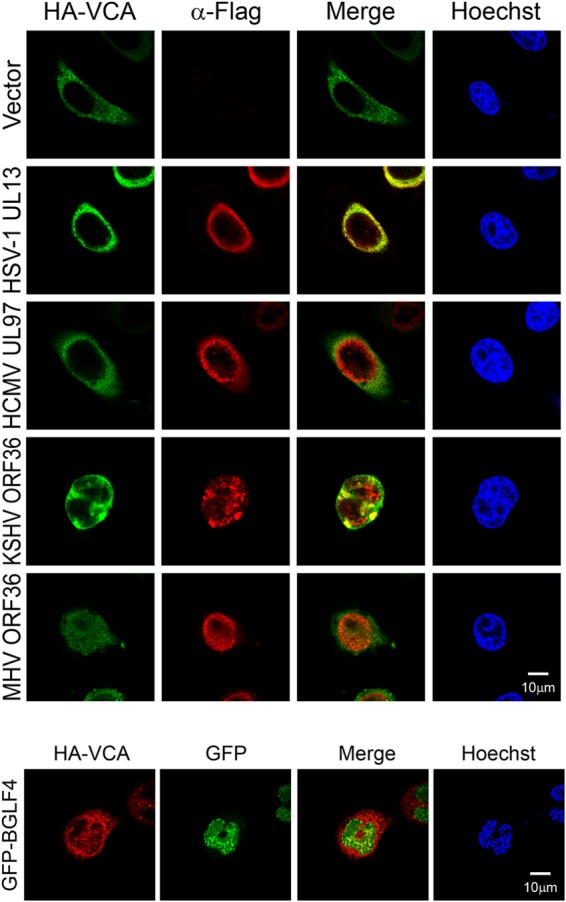

Only the conserved UL protein kinases of gammaherpesviruses and not alpha- and betaherpesviruses induce nuclear import of VCA.

Previously, we found that the BGLF4 homologue proteins HSV-1 UL13, HCMV UL97, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) ORF36, and MHV68 ORF36 induce partial nuclear lamina disassembly through a BGLF4-like mechanism (34, 55). Therefore, the abilities of herpesviral UL kinases to induce the nuclear transport of VCA were also examined. Flag-tagged UL kinases of various herpesviruses and HA-VCA were transiently coexpressed in HeLa cells (Fig. 8). Notably, the nuclear import of HA-VCA was observed only in cells expressing ORF36 of the gammaherpesviruses KSHV and MHV68, suggesting that alpha- and betaherpesviral UL kinases do not possess a BGLF4-like activity that induces the nuclear import of HA-VCA. To determine whether ORF36 can also promote the nuclear import of EBV replication components, Myc-BSLF1 or BBLF4 was expressed together with KSHV ORF36. Immunofluorescence staining showed that these three proteins were distributed in the cytoplasm of ORF36-coexpressing cells (data not shown), suggesting a difference between BGLF4 and other UL kinases.

FIG 8.

Gammaherpesviral UL kinases promote the nuclear import of VCA. HeLa cells were transfected with HA-VCA together with Flag-tagged HSV-1 UL13-, HCMV UL97-, KSHV ORF36-, MHV68 ORF36-, or vector control-expressing plasmids. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were fixed and stained for Flag-tagged protein, HA-VCA, and DNA as described in Materials and Methods. For comparison with the effect of BGLF4, GFP-BGLF4 was coexpressed with HA-VCA, stained with anti-HA antibody and Hoechst 33258, and observed by confocal microcopy.

DISCUSSION

NPCs are the only channels of material exchange between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and prevent the nuclear entry of pathogenic materials. The gating function of nucleocytoplasmic transport provides an important means of regulation of signaling pathways, cell cycle progression, and antiviral mechanisms (for reviews, see references 56 and 57). Viruses that replicate their genomes in the nucleus have evolved novel mechanisms to transport their genomes and replication-associated components in and out of the nucleus. Previously, we found that FG-Nups were partially redistributed into the nucleus in cells expressing BGLF4, but the mechanism involved was not explored (38). In this study, we investigated the morphological changes in the nuclear envelope in cells in which EBV is replicating and the BGLF4-induced NPC structural changes. During EBV reactivation, the distribution of the nuclear envelope-associated proteins, including SUN1, SUN2, and emerin, changed (Fig. 1A), suggesting that the integrity of the nuclear envelope was altered dramatically during virus replication. In addition to inducing the partial disassembly of the nuclear lamina (34), BGLF4 induced the reorganization of the nuclear envelope. BGLF4 alone induced the redistribution of SUN1 and SUN2 (Fig. 1B), even though the expression patterns were different from those observed in cells with EBV reactivation. We suspect that multiple viral proteins may contribute to the modification of the nuclear envelope. For example, the EBV nuclear envelope-associated protein BFRF1 was found to recruit the cellular endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery and induce the formation of nuclear envelope-derived vesicles containing emerin, FG-Nups, and nuclear lamina (51).

Previously, we demonstrated that BGLF4 interacts with Nup62 and Nup153 and induces the redistribution of FG-Nups, as revealed by the MAb414 antibody (38). Here we determined whether BGLF4 can modify the NPC function and regulate cytoplasmic-nuclear transport. In immunostaining and confocal analysis, BGLF4, but not a BGLF4 kinase-dead K102I mutant, induced the redistribution of Nup62 and Nup153 (Fig. 3B and C), implying that BGLF4 modifies the NPC composition in a kinase activity-dependent manner. It is noted that phosphorylation was proposed to participate in regulating the nuclear transport machinery, although the precise mechanisms are yet to be determined (58). Some Nups, including Nup62 and Nup153, have been shown to be phosphorylated in various situations (59–61). For example, mitotic disassembly of nuclear pores is associated with changes in the phosphorylation status of certain Nups, including the Nup107-Nup160 complex, Nup98, and Nup62 (60–63). In this study, BGLF4 induced a slightly increased phosphorylation of Nup62 and Nup153 in transfected cells, as detected by the MPM2 antibody for phosphorylated Ser/Thr-Pro (Fig. 4A). Although Nup62 has been reported to be a substrate of BGLF4 in a protein microarray assay (32), only the phosphorylation of Nup153 was detected by our in vitro IP kinase assay (Fig. 4B). It is possible that the protein substrates fixed on the glass of the protein array may have minor structural differences from the native immunocomplexes in our in vitro kinase assay. Nevertheless, it is still possible that BGLF4 coordinates with cellular kinases to phosphorylate Nup62 in the cells. In the TEM analysis, it was found that BGLF4 induced dramatic morphological changes in the nuclear envelope and the dilation of nuclear pores near the nuclear concave region (Fig. 5), indicating that BGLF4 potentially modifies the structure of the NPC in a position-dependent manner.

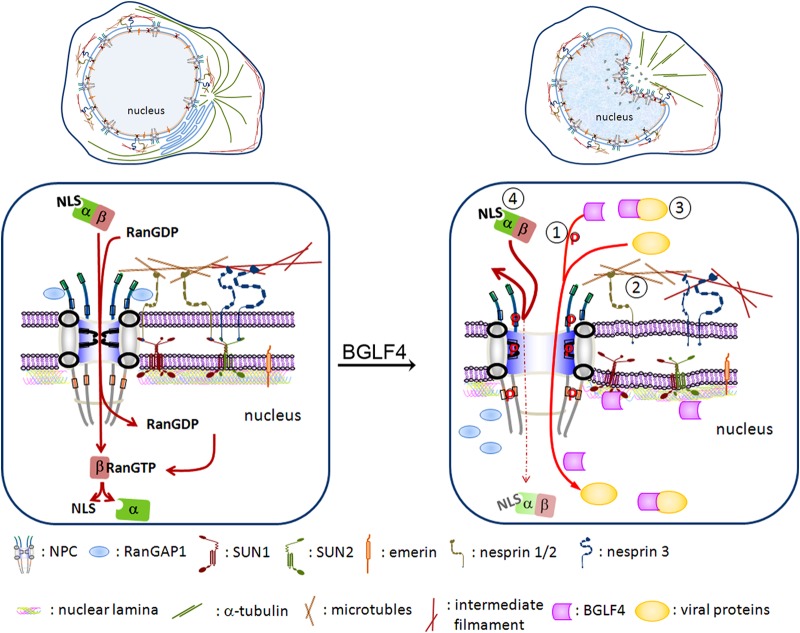

In this study, we found that the redistribution of Nup62 and Nup153 induced by BGLF4 may affect the gating function of the NPC and confer some selective transport advantages to viral proteins. BGLF4 inhibited the nuclear import of importin β and YFP-LacZ-NLS in an in vitro transport assay using digitonin-permeabilized cells (Fig. 6A and B), suggesting that BGLF4 kinase may interfere with the canonical importin-mediated NLS-dependent nuclear transport of cellular proteins. The in vitro nuclear import assay with 70-kDa dextran indicated further the BGLF4-induced leakiness of the NPC toward the nucleoplasm (Fig. 6D). However, the YFP-LacZ-NLS imported into the nucleus did not leak into the cytoplasm after BGLF4 expression, suggesting that the NPC gating function for transport from the nucleus to the cytoplasm was not lost (Fig. 6E). The most interesting finding here is that BGLF4 appeared to facilitate the nuclear transport of viral proteins through multiple specific mechanisms, rather than nonspecific leakiness (Fig. 7). Taken together, we propose that, during EBV reactivation, BGLF4 modifies not only the nuclear lamina but also nuclear envelope-associated proteins, including SUN1, SUN2, emerin, and nucleoporins, to induce the structural changes in the nuclear envelope and nuclear pores and promote the nuclear import of viral proteins for viral DNA replication and nucleocapsid packaging (Fig. 9).

FIG 9.

Hypothetical model of the EBV BGLF4-induced structural and functional changes of the nuclear pore complex. (Left) Under physiological conditions, the nuclear import of NLS-containing proteins is mediated by an importin α-importin β complex and is dependent on RanGTP hydrolysis. (Right) In the presence of BGLF4, BGLF4 is transported into the nucleus through direct interaction and phosphorylation of FG-Nups, including Nup62 and Nup153, to dilate the nuclear pores. Simultaneously, BGLF4 also induces microtubule reorganization and causes changes in the nuclear shape. The nuclear envelope becomes irregular, and the nuclear envelope-associated proteins, such as SUN1 and SUN2, are redistributed. Non-NLS-containing viral proteins can be transported into the nucleus at the same time through at least three different mechanisms: (i) dilated nuclear pores, (ii) a microtubule reorganization-dependent mechanism, or (iii) direct interaction with or phosphorylation by BGLF4. (iv) At the same time, the nuclear import of canonical NLS containing proteins is partly inhibited.

The composition and functions of the NPC are modulated by various viruses for efficient nuclear targeting and to compete for intranuclear resources for virus replication (57, 64). For example, picornaviruses induce dramatic alterations in nucleocytoplasmic trafficking. One mechanism is through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-mediated phosphorylation-dependent reduction of the interaction between FG-Nups and importin β, which attenuates the nuclear import of cellular NLS-containing proteins (59, 65, 66). RNA viruses in the Picornaviridae family, including enteroviruses and rhinoviruses, are able to permeabilize the NPC through cleavage of Nup62, Nup98, and Nup153 by the viral protease 2Apro, resulting in the receptors for many cellular cargos, such NLS and nuclear export signal (NES), being unable to be transported through NPCs, despite their directional signal sequences (19–21, 67). Without a 2Apro-like polypeptide, cardioviruses induce alterations of nucleocytoplasmic transport by the viral leader (L) protein-dependent hyperphosphorylation of Nup62, Nup153, and Nup214, which may alter their integrity and ability to bind to the transport receptor of NPC (22, 23, 65). It was also suggested that viruses may antagonize the host immune response by blocking the nuclear import of signaling molecules (for a review, see reference 57).

On the other hand, components of the NPC may be used by viruses to support their replication. For example, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) uses NPC components for both preintegration complex (PIC) import and Rev-viral RNA RNP export (68). While lamin A/C is intact in HIV-1-infected cells, Nup62 is redistributed from the nuclear envelope into the cytoplasm. Nup62 also has been identified as a component of purified HIV, and small interfering RNA depletion studies revealed an important role for Nup62 in virus gene expression and infectivity (69). Nup153 also plays an important role during HIV infection and early replication steps through interaction with HIV integrase (68, 70–72).

Infections by herpesviruses were also reported to induce changes in the NPC structure and function. During HSV-1 infection, the immediate early protein ICP27, which is important for the nuclear export of viral mRNAs, was found to inhibit the host nucleocytoplasmic transport pathway through direct interaction with Nup62 (73). Alterations in nuclear shape and size were found in HSV-1-infected cells (74). HSV-1 infection also induced morphological alterations in nuclear pores, visualized by electron microscopy, resulting in the loss of pore numbers and an increase in dilated gaps in the nuclear membrane (75). In HCMV-infected cells, a change in the shape of the nucleus and leakage of 155-kDa dextran into the nucleus were found at the nuclear concave regions, close to the cytoplasmic assembly compartment (76). Interestingly, in the cells expressing BGLF4, HA-VCA appeared to cluster at the nuclear periphery, with a proportion leaking into the nucleus through the perinuclear concave region (Fig. 7C), suggesting that similar mechanisms may be involved in the nuclear targeting of viral proteins by both viruses.

Because VCA is a major capsid protein of EBV, we suspect that BGLF4-mediated nuclear targeting of VCA may occur at two different stages. Upon infection, BGLF4 can be delivered to the cells as a tegument component and enable the viral nuclear capsid to move along microtubules until it comes close to the nuclear pore and can inject the viral DNA into nucleus. In addition, BGLF4 may promote the translocation of newly synthesized VCA into the nucleus for the assembly of procapsids and encapsidation of viral genomes. Alterations of the nuclear and cytoplasmic architecture are required for nuclear egress and cytoplasmic assembly of HCMV virions (76–78). The microtubule motor proteins dynein and kinesin are also involved in altering the nuclear morphology during HSV and HCMV infection (76, 79). We found that paclitaxel treatment prevented the BGLF4-induced changes in the nuclear shape and the nuclear import of HA-VCA (Fig. 7E). This suggests that HA-VCA was transported into nucleus through a novel pathway dependent on both BGLF4-induced NPC dilation and microtubule reorganization.

Among the conserved herpesviral kinases, we found that only gammaherpesviral kinases are able to induce the leakiness of HA-VCA from the cytoplasm into the nucleus (Fig. 8), suggesting that, although modulation of nucleocytoplasmic transport is required for all herpesviruses, minor differences may have evolved with the different viruses. Notably, the nuclear staining patterns of Myc-BSLF1, -BBLF2/3, and -BBLF4 are distinct from the nuclear staining pattern of HA-VCA. Paclitaxel treatment also showed that BGLF4 seems to use alternative pathways, independent of microtubule reorganization, to promote the nuclear import of EBV DNA replication components (data not shown). Although multiple possible BGLF4 phosphorylation sites (Ser/Thr-Pro) were found in the amino acid sequences of these three proteins, only BBLF4, and not BSLF1 or BBLF2/3, was identified to be a BGLF4 substrate in a previous protein array analysis (31). However, in our cotransfection experiments, no obvious BGLF4-induced phosphorylation was observed on all three proteins (Fig. 7B), suggesting that direct phosphorylation may not be the mechanism for BGLF4-mediated nuclear transport of these proteins. Because BBLF2/3 was coimmunoprecipitated with BGLF4 and colocalized with BGLF4 in transfected cells (Fig. 7B), it is possible that BBLF2/3 was translocated into the nucleus through its association with BGLF4. Overall, we propose that BGLF4 may promote the nuclear import of various viral proteins through multiple pathways: (i) BGLF4 phosphorylates nucleoporins to induce NPC dilation, (ii) BGLF4 induces microtubule reorganization, or (iii) BGLF4 forms complexes with viral proteins to promote their nuclear import. (iv) At the same time, BGLF4 blockage of the nuclear import of host NLS-mediated proteins may prevent the nuclear import of antiviral proteins (Fig. 9). However, it is not clear whether cellular non-NLS-dependent nuclear proteins are also regulated by BGLF4 by a similar mechanism.

In this study, we found that the FG-Nups, at least Nup62 and Nup153, were redistributed from the nuclear envelope into the nucleoplasm but did not diffuse into the cytoplasm after EBV reactivation in NA cells or in HeLa cells in which BGLF4 was expressed (Fig. 2A and 3B). Under physiological conditions, many nucleoporins are mobile and can be detected in the nucleus (80). Several studies indicated that the nucleoplasmic pool of nucleoporins may regulate transcription. Oncogenic fusion proteins of nucleoporins and various nuclear proteins are able to activate or repress target genes in the nucleoplasm, leading to human leukemia (81–83). Previously, intranuclear Nup98 and Nup62 were found to regulate subsets of gene expression in Drosophila (84). Because BGLF4 has been shown to regulate the transcriptional activities of several viral and cellular genes (35, 85), it would be interesting to determine whether FG-Nups in the nucleoplasm are involved in BGLF4-mediated transcriptional regulation.

A recent study revealed that SUMOylation of PTEN promotes its nuclear localization, implying that nuclear transport may also be mediated through protein modification (86). In a protein array phosphorylation analysis, SUMO-1 was identified as a BGLF4 substrate (32) and two SUMO binding motifs (SIMs) were identified in BGLF4 (87). Because SUMOylated RanGAP1 can form complexes with Nup358 (88), our observation that BGLF4 induced the RanGAP1 redistribution (Fig. 6C) hints that the status of SUMOylated RanGAP1 is affected by BGLF4. The precise mechanism of BGLF4-regulated SUMOylation for the nuclear transport of proteins should be explored in the future.

In addition to regulating material trafficking between the cytoplasm and the nucleus, BGLF4 may contribute to EBV-associated malignancies through affecting the architecture of the nuclear envelope. Many nuclear envelope-associated proteins also linked to multiple cellular signaling pathways, and their misregulation usually accompanies various types of pathogenesis and cancer formation (89). We suggest that the periodic abortive reactivation of EBV, with the expression of early genes but no virion production, may provide chances to accumulate insults to host genome integrity and further cancer development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Tim J. Harrison of University College London for critical reading and modification of the manuscript. We thank Mitsuhiro Kawata at the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine for the pEYFP-LacZ-NLS plasmid, Yoshihiro Yoneda at Osaka University for the GST-importin β plasmid, Jean Lu at the Academia Sinica for the Nup62 cDNA clone, and Ya-Hui Chi at the National Health Research Institutes Taiwan for the SUN1 antibody. We are also grateful to Diane S. Hayward at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine for the Myc-BSLF1, Myc-BBLF2/3, and Myc-BBLF4 plasmids, Shih-Tung Liu at Chang-Gung University, Taiwan, for the HA-VCA plasmid, and Ren Sun and Seungmin Hwang at the University of California, Los Angeles, for Flag-tagged herpesvirus kinase-expressing plasmids. We appreciate the help from Ji-Ying Huang at the National Taiwan University Hospital Image Core Lab and Hua-Man Hsu at the First Cone Laboratory, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, for technical assistance with the confocal images. We also appreciate the technical advice for TEM from Chiung-hsiang Cheng at the Joint Center for Instruments and Researches, College of Bioresources and Agriculture, NTU.

This study was supported by the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-EX103-10201BI), the National Science Council (NSC101-2320-B-002-031-MY3), and the National Taiwan University (intramural grant 103C101-A4).

REFERENCES

- 1.Young LS, Rickinson AB. 2004. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nat Rev Cancer 4:757–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mauser A, Holley-Guthrie E, Zanation A, Yarborough W, Kaufmann W, Klingelhutz A, Seaman WT, Kenney S. 2002. The Epstein-Barr virus immediate-early protein BZLF1 induces expression of E2F-1 and other proteins involved in cell cycle progression in primary keratinocytes and gastric carcinoma cells. J Virol 76:12543–12552. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12543-12552.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee CP, Chen MR. 2010. Escape of herpesviruses from the nucleus. Rev Med Virol 20:214–230. doi: 10.1002/rmv.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gualtiero A, Jans DA, Camozzi D, Avanzi S, Loregian A, Ripalti A, Palu G. 2013. Regulated transport into the nucleus of herpesviridae DNA replication core proteins. Viruses 5:2210–2234. doi: 10.3390/v5092210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henson BW, Perkins EM, Cothran JE, Desai P. 2009. Self-assembly of Epstein-Barr virus capsids. J Virol 83:3877–3890. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01733-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruenbaum Y, Wilson KL, Harel A, Goldberg M, Cohen M. 2000. Review: nuclear lamins—structural proteins with fundamental functions. J Struct Biol 129:313–323. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Razafsky D, Hodzic D. 2009. Bringing KASH under the SUN: the many faces of nucleo-cytoskeletal connections. J Cell Biol 186:461–472. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haque F, Mazzeo D, Patel JT, Smallwood DT, Ellis JA, Shanahan CM, Shackleton S. 2010. Mammalian SUN protein interaction networks at the inner nuclear membrane and their role in laminopathy disease processes. J Biol Chem 285:3487–3498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.071910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macara IG. 2001. Transport into and out of the nucleus. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 65:570–594. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.4.570-594.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wente SR. 2000. Gatekeepers of the nucleus. Science 288:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cronshaw JM, Krutchinsky AN, Zhang W, Chait BT, Matunis MJ. 2002. Proteomic analysis of the mammalian nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 158:915–927. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suntharalingam M, Wente SR. 2003. Peering through the pore: nuclear pore complex structure, assembly, and function. Dev Cell 4:775–789. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00162-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rout MP, Aitchison JD. 2001. The nuclear pore complex as a transport machine. J Biol Chem 276:16593–16596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorokin AV, Kim ER, Ovchinnikov LP. 2007. Nucleocytoplasmic transport of proteins. Biochemistry (Mosc) 72:1439–1457. doi: 10.1134/S0006297907130032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorlich D, Henklein P, Laskey RA, Hartmann E. 1996. A 41 amino acid motif in importin-alpha confers binding to importin-beta and hence transit into the nucleus. EMBO J 15:1810–1817. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weis K, Ryder U, Lamond AI. 1996. The conserved amino-terminal domain of hSRP1 alpha is essential for nuclear protein import. EMBO J 15:1818–1825. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wente SR, Rout MP. 2010. The nuclear pore complex and nuclear transport. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000562. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whittaker GR, Kann M, Helenius A. 2000. Viral entry into the nucleus. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 16:627–651. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gustin KE, Sarnow P. 2001. Effects of poliovirus infection on nucleo-cytoplasmic trafficking and nuclear pore complex composition. EMBO J 20:240–249. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gustin KE, Sarnow P. 2002. Inhibition of nuclear import and alteration of nuclear pore complex composition by rhinovirus. J Virol 76:8787–8796. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.17.8787-8796.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park N, Katikaneni P, Skern T, Gustin KE. 2008. Differential targeting of nuclear pore complex proteins in poliovirus-infected cells. J Virol 82:1647–1655. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01670-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delhaye S, van Pesch V, Michiels T. 2004. The leader protein of Theiler's virus interferes with nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of cellular proteins. J Virol 78:4357–4362. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.4357-4362.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lidsky PV, Hato S, Bardina MV, Aminev AG, Palmenberg AC, Sheval EV, Polyakov VY, van Kuppeveld FJ, Agol VI. 2006. Nucleocytoplasmic traffic disorder induced by cardioviruses. J Virol 80:2705–2717. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2705-2717.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porter FW, Brown B, Palmenberg AC. 2010. Nucleoporin phosphorylation triggered by the encephalomyocarditis virus leader protein is mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Virol 84:12538–12548. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01484-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen MR, Chang SJ, Huang H, Chen JY. 2000. A protein kinase activity associated with Epstein-Barr virus BGLF4 phosphorylates the viral early antigen EA-D in vitro. J Virol 74:3093–3104. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.7.3093-3104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang JT, Yang PW, Lee CP, Han CH, Tsai CH, Chen MR. 2005. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus BGLF4 protein kinase in virus replication compartments and virus particles. J Gen Virol 86:3215–3225. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asai R, Kato A, Kato K, Kanamori-Koyama M, Sugimoto K, Sairenji T, Nishiyama Y, Kawaguchi Y. 2006. Epstein-Barr virus protein kinase BGLF4 is a virion tegument protein that dissociates from virions in a phosphorylation-dependent process and phosphorylates the viral immediate-early protein BZLF1. J Virol 80:5125–5134. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02674-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato K, Yokoyama A, Tohya Y, Akashi H, Nishiyama Y, Kawaguchi Y. 2003. Identification of protein kinases responsible for phosphorylation of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen leader protein at serine-35, which regulates its coactivator function. J Gen Virol 84:3381–3392. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19454-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang PW, Chang SS, Tsai CH, Chao YH, Chen MR. 2008. Effect of phosphorylation on the transactivation activity of Epstein-Barr virus BMRF1, a major target of the viral BGLF4 kinase. J Gen Virol 89:884–895. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yue W, Gershburg E, Pagano JS. 2005. Hyperphosphorylation of EBNA2 by Epstein-Barr virus protein kinase suppresses transactivation of the LMP1 promoter. J Virol 79:5880–5885. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5880-5885.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu J, Liao G, Shan L, Zhang J, Chen MR, Hayward GS, Hayward SD, Desai P, Zhu H. 2009. Protein array identification of substrates of the Epstein-Barr virus protein kinase BGLF4. J Virol 83:5219–5231. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02378-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li R, Zhu J, Xie Z, Liao G, Liu J, Chen MR, Hu S, Woodard C, Lin J, Taverna SD, Desai P, Ambinder RF, Hayward GS, Qian J, Zhu H, Hayward SD. 2011. Conserved herpesvirus kinases target the DNA damage response pathway and TIP60 histone acetyltransferase to promote virus replication. Cell Host Microbe 10:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kudoh A, Daikoku T, Ishimi Y, Kawaguchi Y, Shirata N, Iwahori S, Isomura H, Tsurumi T. 2006. Phosphorylation of MCM4 at sites inactivating DNA helicase activity of the MCM4-MCM6-MCM7 complex during Epstein-Barr virus productive replication. J Virol 80:10064–10072. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00678-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee CP, Huang YH, Lin SF, Chang Y, Chang YH, Takada K, Chen MR. 2008. Epstein-Barr virus BGLF4 kinase induces disassembly of the nuclear lamina to facilitate virion production. J Virol 82:11913–11926. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01100-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang LS, Wang JT, Doong SL, Lee CP, Chang CW, Tsai CH, Yeh SW, Hsieh CY, Chen MR. 2012. Epstein-Barr virus BGLF4 kinase downregulates NF-kappaB transactivation through phosphorylation of coactivator UXT. J Virol 86:12176–12186. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01918-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang JT, Doong SL, Teng SC, Lee CP, Tsai CH, Chen MR. 2009. Epstein-Barr virus BGLF4 kinase suppresses the interferon regulatory factor 3 signaling pathway. J Virol 83:1856–1869. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01099-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang YH, Lee CP, Su MT, Wang JT, Chen JY, Lin SF, Tsai CH, Hsieh MJ, Takada K, Chen MR. 2012. Epstein-Barr virus BGLF4 kinase retards cellular S-phase progression and induces chromosomal abnormality. PLoS One 7:e39217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang CW, Lee CP, Huang YH, Yang PW, Wang JT, Chen MR. 2012. Epstein-Barr virus protein kinase BGLF4 targets the nucleus through interaction with nucleoporins. J Virol 86:8072–8085. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01058-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takada K, Horinouchi K, Ono Y, Aya T, Osato T, Takahashi M, Hayasaka S. 1991. An Epstein-Barr virus-producer line Akata: establishment of the cell line and analysis of viral DNA. Virus Genes 5:147–156. doi: 10.1007/BF00571929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang Y, Tung CH, Huang YT, Lu J, Chen JY, Tsai CH. 1999. Requirement for cell-to-cell contact in Epstein-Barr virus infection of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells and keratinocytes. J Virol 73:8857–8866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee CP, Chen JY, Wang JT, Kimura K, Takemoto A, Lu CC, Chen MR. 2007. Epstein-Barr virus BGLF4 kinase induces premature chromosome condensation through activation of condensin and topoisomerase II. J Virol 81:5166–5180. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00120-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang WH, Chang LK, Liu ST. 2011. Molecular interactions of Epstein-Barr virus capsid proteins. J Virol 85:1615–1624. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01565-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su MT, Liu IH, Wu CW, Chang SM, Tsai CH, Yang PW, Chuang YC, Lee CP, Chen MR. 2014. Uracil DNA glycosylase BKRF3 contributes to Epstein-Barr virus DNA replication through physical interactions with proteins in viral DNA replication complex. J Virol 88:8883–8899. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00950-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]