Abstract

Gold nanoparticles provide a template for preparing supported lipid layers with well-defined curvature. Here, we utilize the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) of gold nanoparticles as a sensor for monitoring the preparation of lipid layers on nanoparticles. The LSPR is very sensitive to the immediate surroundings of the nanoparticle surface and it is used to monitor the coating of lipids and subsequent conversion of a supported bilayer to a hybrid membrane with an outer lipid leaflet and an inner leaflet containing hydrophobic alkanethiol. We demonstrate that both decanethiol and propanethiol are able to form hybrid membranes and that the membrane created over the shorter thiol can be stripped from the gold along with the lipid leaflet using β-mercaptoethanol. The sensitivity of the nanoparticle LSPR to the refractive index (RI) of its surroundings is greater when the shorter thiol is used (37.8 ± 1.5 nm per RI unit) than when the longer thiol is used (27.5 ± 0.5 nm per RI unit). Finally, C-reactive protein binding to the membrane is measured using this sensor allowing observation of both protein-membrane and nanoparticle-nanoparticle interactions without chemical labeling of protein or lipids.

INTRODUCTION

The preparation of lipid layers on solid supports is a common approach for creating mimics of cellular membranes that facilitates the study of membrane properties and protein-membrane interactions.1 Recent work has demonstrated that quantum dots,2,3 silica microparticles,4 silica nanoparticles,5–7 gold nanoparticles,8,9 (GNPs) and gold nanorods10,11 all can be used as templates for supported lipid membranes providing an opportunity to control membrane curvature through nanoparticle synthesis. Both supported lipid bilayers that consist of two opposing leaflets of lipids1,4 and hybrid membranes where a surface bound hydrophobic group is combined with a single lipid leaflet12 are amenable to nanoparticle templating. While many materials have been used as membrane supports, there are unmet needs in the development of membrane mimics and it remains challenging to non-invasively analyze assembly of these molecular films.

GNPs are ideal for monitoring lipid layers because they can act as a sensing element that reports on the environment immediately surrounding the gold. When excited by electromagnetic radiation in the visible range, metal nanoparticles undergo localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR).13 The LSPR response arises from the electric field of the incident light driving surface conduction electrons collectively away from the metal nanoparticle lattice. A restoring force is provided by the coulombic attraction between the negatively charged electron cloud and the positively charged metal lattice. Those wavelengths of light that couple most strongly to this resonance are absorbed and elastically re-emitted as scattered light. Nanoparticle composition,14,15 geometry,16 proximity to other nanoparticles,17,18 and the local refractive index (RI)19 all can alter the resonance of plasmonic structures. A variety of sensors have been demonstrated that utilize plasmonic nanostructures as signal transduction elements20–22 including sensors for protein-membrane interactions based on nanohole surfaces.23

Tracking changes in the LSPR of soluble GNPs should allow for real-time observation of changes to membrane structure or membrane binding events while avoiding chemical modification of the membrane or membrane-binding proteins. The RI sensitivity of the LSPR derives from the fact that the electric field of the oscillating electrons extends into the volume beyond the surface of the nanoparticle, making this approach very sensitive to changes in RI close to the GNP surface. Changing the dielectric properties of this region alters the energy associated with the electric field oscillation. As most biological materials are non-absorbing at the LSPR wavelength, optical changes report directly on RI changes near the GNP surface with increases in RI leading to a red-shift of the LSPR.13,24 Lipid membranes on soluble GNPs should be ideal for LSPR monitoring of protein-membrane binding events and we seek to demonstrate that a compact lipid coating on GNPs still allows detection of RI changes at the membrane surface despite the small sensing volume for GNPs.13 Unlike nanohole supported membranes,23 GNPs provide precise control of curvature without planar membrane regions or regions of negative curvature. Hybrid membranes consisting of one outer leaflet of lipid and an inner leaflet of alkanethiol have been prepared on spherical GNPs with 6,25 10,26 12,27 16,27 and 1828 carbon alkanethiol chain lengths and on gold nanoshells with 1229 and 1830 carbon alkanethiol chain lengths providing many systems in which LSPR tracking could be used to understand membrane assembly and to observe protein binding. While many systems have been synthesized, LSPR tracking has not been used to monitor membrane assembly or protein binding.

In this work, we exploit the local RI sensitivity of GNPs to observe the process of lipid-coating, structural rearrangement of lipid bilayers into hybrid membranes, and finally the binding of protein to the resultant hybrid membrane. Changes in the LSPR peak provided insight into the membrane structure and mechanism of the lipid coating. Introduction of oleate then the lipid phosphatidylcholine (PC) to citrate-capped GNPs results in a rapid adsorption. By adding hydrophobic alkanethiols, propanethiol (PT) or decanethiol (DT), a hybrid membrane was formed. This results in a membrane that fully encompasses the GNPs as demonstrated by increased cyanide stability31 achieved at different thresholds for each thiol. A mathematical model was used to describe the effect of each ligand change on the LSPR. This simple model provided a weighted average RI that takes into account the exponentially decaying RI sensitivity from the GNP surface. The model and experimentally determined RI sensitivity to sucrose was higher for the PT-based hybrid membrane and lower for the thicker DT-based hybrid membrane. When C-reactive protein (CRP), a PC binding protein, was introduced to the PT based sensor, changes to the LSPR revealed protein binding to the membrane, demonstrating the utility of the soluble GNPs as a label-free sensor.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Materials

Purified human C-reactive protein in 50 mM Tris at pH 8.0 containing 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2 and 0.1% NaN3 was from Academy Biomedical (Houston, TX). 18 MΩ Ultrapure water was from a Milli-Q Integral Water Purification System by EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Sodium oleate (TCI America, Portland, OR), 95% L-α-phosphatidylcholine (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) and potassium cyanide (Mallinckrodt) were used as received. Ponceau S (Sigma) was diluted in water to an optical density (OD) of 0.8. All other reagents were from Sigma and used as received.

Coating of Nanoparticles

GNP cores, 20 ± 9 nm in diameter as measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS), were synthesized by citrate reduction of HAuCl4.32,33 Sodium oleate was prepared at 10 mM in water. DT was freshly prepared at 1 mM in ethanol, PT and BME stocks were freshly prepared at 1 mM in water. Lipid films were created by dissolving PC in chloroform, then removing the solvent by evaporation under nitrogen, exposing the films to vacuum overnight at room temperature, and storing at −20°C until use. Lipid films were reconstituted in HEPES buffer (10 mM) and subsequently sonicated (Branson Sonifier 450, Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT) for 60 min and extruded 11 times using a Mini Extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) with a 100 nm pore size polycarbonate filter. The liposome hydrodynamic diameter (202 ± 9 nm) after extrusion was measured by DLS. GNPs (1 mL of 0.9 OD) were placed in a cuvette with a stirring rod. After allowing the sample to equilibrate for 30 min, sodium oleate (5 μL) was added and stirred for 30 min. PC (10 μL of 0.01 M) was added and stirred for 60 min. Finally, various amounts of DT or PT stock were added to anchor the lipids to the GNP surface.

GNP Stability

Potassium cyanide was dissolved in water (600 mM). Thiol-anchored, lipid-coated gold nanoparticles were tested for cyanide permeability by the addition of 10 μL of the cyanide solution (6 mM final concentration) while stirring at room temperature. UV-vis spectra were taken of each sample before the addition of cyanide and at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 24 hrs after cyanide addition. For membrane displacement assays, 1 mM BME was added to GNP-PC-PT or GNP-PC-DT followed by 10 μL of the cyanide solution. The intensity was compared to the original extinction at 525 nm to determine the percent of the OD retained after the loss of signal due to cyanide oxidation.

LSPR Monitoring

Nanoparticle suspensions were illuminated by a deuterium-tungsten halogen light source (DH-2000, Ocean Optics) and extinction spectra were collected with a fiber-coupled Ocean Optics HR4000. Integration times of 22 milliseconds per spectrum and averaging 50 spectra per data set were used to optimize the signal-to-noise ratio. Data analysis was performed on each of these averaged spectra to extract three characteristic parameters describing the LSPR peak: the full width at half-max (FWHM), the resonant wavelength, and the OD. The resonant wavelength of the LSPR peak was calculated as the centroid of the peak above the FWHM. This method has been shown to track linearly with the LSPR peak while providing an improved signal to noise ratio.34 To reduce contributions from noise, the extinction intensity of the peak is described by the average of the peak intensity spanning the FWHM. The same series of additions was performed using a sample of the red dye, Ponceau S. The mean and standard deviation of changes in LSPR, FWHM, and OD are reported.

Mathematical Model

A coated sphere model based on Mie’s theory of light scattering by sub-wavelength particles was utilized where the particle is considered to be surrounded by a dielectric shell.14 The complex microenvironment surrounding the GNP core was simulated as a homogenous layer with a single effective refractive index (ηeff) that is the calculated weighted average of the constituent RIs. This value was calculated for a particular nanoparticle by spatially averaging the RIs of constituent layers weighted by a scaling factor that accounts for the gradient of the electric field because the RI sensitivity is proportional to the field energy.13,35 RI values for water (1.333), citrate (1.40),36 oleate (1.64),37 PC (1.48),38 DT (1.46),39 and PT (1.44)39 were used in these calculations. The scaling factor used to describe the impact on the LSPR as a function of the distance from the surface was 40–42

| (1) |

where m is the refractive index sensitivity, d is the thickness of the layer and l is the characteristic electromagnetic field decay length. The equation was normalized to unity at the surface of the GNP.

Dynamic Light Scattering

DLS measurements were performed on a Zetasizer Nano S90 (Malvern Instruments, Westborough, MA). Mean hydrodynamic diameter was obtained from the intensity distribution.

C-Reactive Protein Binding

CRP (final concentration of 1 μg/ml) was incubated with 1 mL of nanoparticles prepared using 50 μM oleate, 100 μM PC, and 33 μM PT (GNP-PC-PT) in the presence of 250 μM CaCl2 for 30 min followed by addition of 9.5 mM EDTA for 30 min at 25°C.

Statistical Analysis

Refractive index sensitivity for each type of nanoparticle was determined by a linear regression of the LSPR centroid at varying RI using Microsoft Excel. All R2 values were greater than 0.995. Errors for the RI sensitivity were calculated as the standard deviation about regression. A difference of means t-test was used to compare different GNP sensitivities to sucrose. A p-value of less than 0.001 was considered significant. The error for changes in LSPR were calculated as the square root of the square of the standard deviations of the starting and final GNPs.

RESULTS

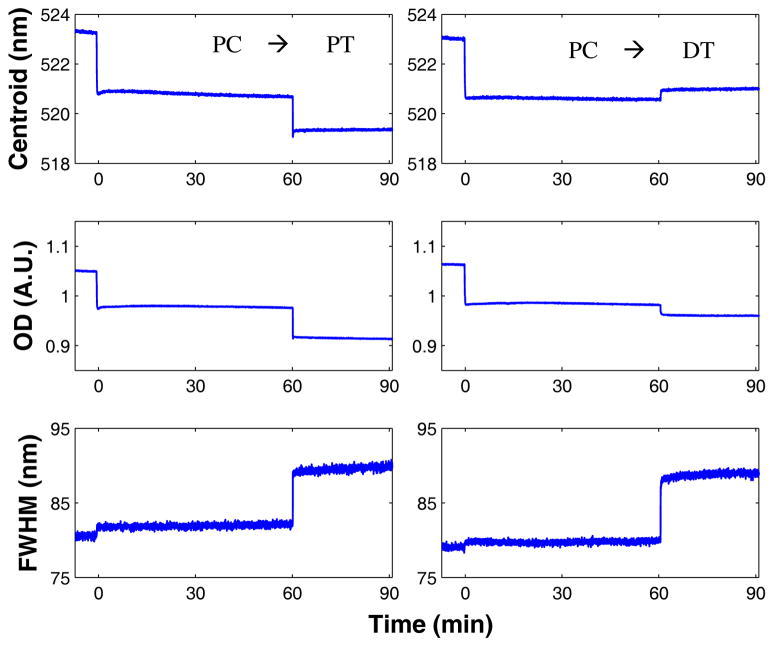

Cyanide stability confirms lipid coating

A cyanide stability assay was used to establish the protective capacity of the lipid coatings. Cyanide oxidizes GNPs and forms a dicyanogold(I) complex that has no LSPR.31 When a lipid membrane fully encompasses the GNPs, cyanide cannot access the metal surface, which is a requirement for etching to occur. The ion impermeability of thiol-stabilized PC membranes has been evaluated by this cyanide assay and it has been shown that PC / DT hybrid membranes are effective at providing cyanide stability.31 We anticipated that the shorter thiol would increase the sensitivity of the sensor to changes in RI but this change came with the risk of making the membrane permeable to ions. A DT concentration of 10 μM provided complete stability to cyanide while 33 μM PT was required to achieve stability (Figure 1). Prior to thiol addition, the PC may only partially coat the GNP surface leaving exposed regions of gold. At the threshold for cyanide stability (10 μM for DT and 33 μM for PT) there is enough hydrophobic coating on the gold that results in a partial or full hybrid membrane coating. The tail-tail interactions between the PC and the thiol results in passivation of the entire GNP. Cyanide is then unable to oxidize the gold core as observed by the persistence of the LSPR.

Figure 1.

The concentration of DT (

) and PT (

) and PT (

) used in GNP preparation compared to OD (at 525 nm) retained after 24 hrs of incubation with 6 mM cyanide. GNPs were coated with 50 μM oleate, 100 μM PC, and varying thiol concentrations. Data reported as mean ± SD, n = 3.

) used in GNP preparation compared to OD (at 525 nm) retained after 24 hrs of incubation with 6 mM cyanide. GNPs were coated with 50 μM oleate, 100 μM PC, and varying thiol concentrations. Data reported as mean ± SD, n = 3.

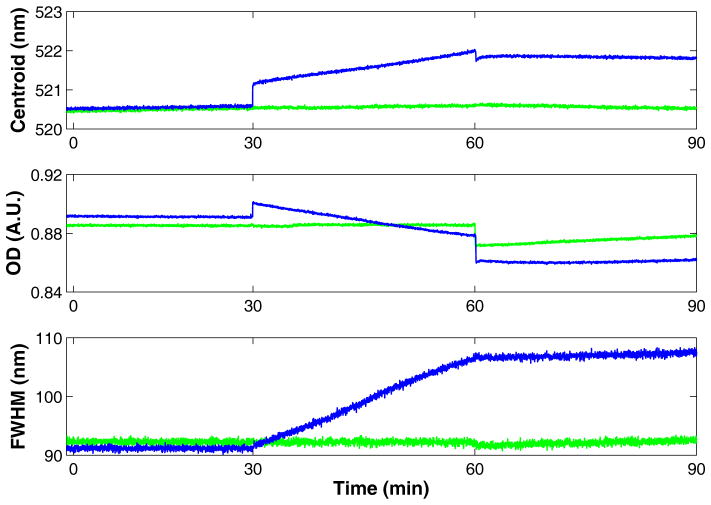

Stripping lipids off gold using a hydrophilic thiol

Previously we have shown that hydrophilic alkanethiols such as BME do not provide anchoring for lipid layers on gold31 and we anticipated that adding BME to a PC-coated GNP would destabilize the outer leaflet of PC by disrupting van der Waals interactions between PC and the alkanethiol. Here, we examined whether BME addition could convert a lipid-coated GNP to a GNP incapable of supporting a lipid layer as demonstrated by cyanide instability (Figure 2). Complete cyanide instability was demonstrated when GNP-PC-PT, prepared with 33 μM PT, was incubated with a mixture of 1 mM BME and 6 mM cyanide for 2–3 hrs. At 33 μM PT, the GNPs would be completely cyanide stable. However, the addition of 1 mM BME, the BME coats enough of the GNP surface to expose the gold to the cyanide. After 3 hrs there is no color to the solution and the residual signal is due to scattering of precipitates rather than residual LSPR. Adding concentrations of BME less than 1 mM also leads to cyanide instability, however, the decomposition takes longer. In contrast, when the longer chain thiol is used, the nanoparticles remain stable to cyanide in the presence of 1 mM BME.

Figure 2.

Stability of lipid layers to BME. GNP-PC-DT (

) prepared with 10 μM DT and GNP-PC-PT (

) prepared with 10 μM DT and GNP-PC-PT (

) prepared with 33 μM PT monitored at (525 nm) for stability to cyanide and BME. Each sample contains 6 mM cyanide and 1 mM BME. Data reported as mean ± SD, n = 10.

) prepared with 33 μM PT monitored at (525 nm) for stability to cyanide and BME. Each sample contains 6 mM cyanide and 1 mM BME. Data reported as mean ± SD, n = 10.

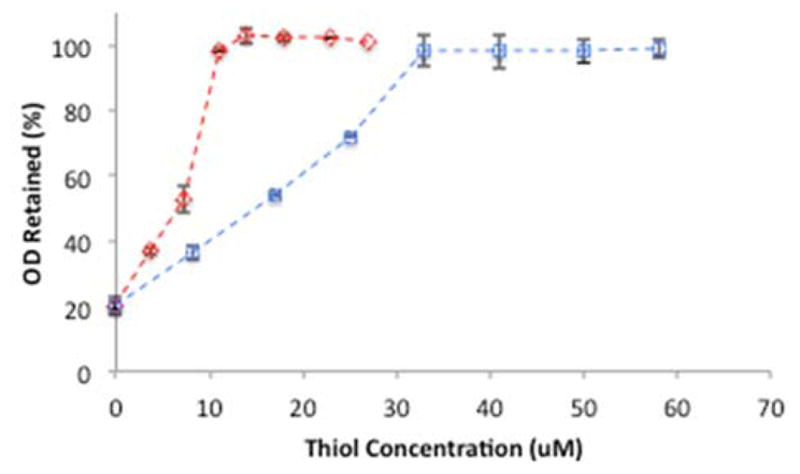

LSPR monitoring of lipid coating process

The LSPR peak centroid, OD, and FWHM were monitored during the lipid coating process (Figure 3, Table 1) and representative spectra of GNPs after each addition were obtained by averaging 1000 individual spectra (equal to 22 min of data) after each plateau was reached (Figure 3D). While the FWHM data was collected in all experiments, the changes other than for thiol were insignificant (Table 1) and therefore only shown for the thiol addition (Figure 4). In almost all addition steps the changes in centroid and OD are very rapid and occur at the same time points. The first change occurs after the GNPs are exposed to oleate. There is an initial upward spike in both the OD and centroid followed by a slow decay. We attribute the peak to micelles of oleate interacting with the surface of the gold and then breaking apart, leaving a coating of oleate on the gold.

Figure 3.

A) GNP layer composition and B-C) comparison of GNPs (blue) and Ponceau S dye (green) during a typical lipid-coating procedure. GNPs or Ponceau S were incubated with 50 μM oleate for 30 min, 100 μM PC for 60 min, and 5 μM PT for 30 min. D) Representative spectra of uncoated GNPs (black) and GNPs after addition of oleate (purple), PC (blue), and PT (green). Each spectrum is a 22 min average after the plateau.

Table 1.

LSPR response of GNPs prepared using 50 μM oleate, 100 μM PC, and 10 μM PT or 10 μM DT. Data mean ± SD reported, n = 3 for PT and DT and n = 6 for others.

| GNP | oleate | PC | PT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DT | ||||

| Centroid (nm) | 518.57 ± 0.04 | 523.22 ± 0.11 | 520.85 ± 0.40 | 519.39 ± 0.25 |

| 521.16 ± 0.56 | ||||

| OD (A.U.) | 0.91 ± 0.01 | 1.06 ± 0.01 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.01 |

| 0.97 ± 0.01 | ||||

| FWHM (nm) | 80.4 ± 0.9 | 79.9 ± 0.8 | 80.4 ± 1.4 | 88.8 ± 0.8 |

| 87.7 ± 1.8 |

Figure 4.

Thiol addition to GNP-PC as measured by LSPR centroid (top), optical density (middle) and peak FWHM (bottom) after addition of 100 μM PC at 0 min and 10 μM PT (left) at 60 min or 10 μM DT (right) at 60 min.

Control experiments with Ponceau S were helpful in distinguishing events occurring at the GNP surface from those caused by ancillary effects. The concern was that the optical properties of the solutions could be influenced by the addition of oleate, PC, or thiol, all of which can form aggregated structures in water that potentially scatter light. Therefore, the same series of additions were performed on samples of Ponceau S that absorbs at a similar wavelength to the GNPs but is not expected to respond to changes in RI. The measured centroid was insensitive to additions of oleate, PC, and thiol, as expected. In cases where dilution rather than changes in RI at the surface of the GNP caused the LSPR to change, the comparison of GNPs to Ponceau S (Figure 3) was helpful. The small changes that occur only in OD for Ponceau S results from dilution in contrast to the GNP samples which vary in centroid, OD, and FWHM. In the case of oleate addition, Ponceau S was used to rule out scattering by the micelles themselves, which would have shown up as an increase in OD and centroid for Ponceau S as well as GNPs (Figure S1). Because OD and centroid spikes after oleate addition only occurred in the GNP samples the cause must be events that changed the RI at the GNP surface not events that change the solution properties.

The addition of PC results in a decrease in the centroid, due to a decrease in the RI near the GNP surface, consistent with a mixture of water and lipid coating. Supported bilayers trap a water layer between the lipid and the substrate.1,43–45 Because water has a lower RI than oleate or PC, the observed centroid decrease (relative to oleate but increases relative to citrate) is consistent with water being trapped under a bilayer. Alternatively, a partial direct coating of a PC bilayer on the GNP combined with an uncoated and solvent-exposed region of the surface could provide a similar change in LSPR (see supporting information). Equilibrium is reached in a few minutes suggesting a rapid interaction of PC with the GNPs. Serial addition of PC reveals that 100 μM PC is close to a saturation point for the GNPs (Figure S2). A PC concentration slightly below saturation is used to minimize the possibility of lipid multi-layering. Furthermore, conversion of the supported bilayer of PC to a hybrid membrane with a single PC leaflet will occur with loss of lipid, therefore using less PC than required for saturation avoids excess PC being released.

The difference between the short chain thiol (PT) and the long chain thiol (DT) can be seen through a close comparison of the LSPR after thiol addition (Figure 4) where either an increase or decrease in centroid is observed depending on the chain length of the thiol. The centroid decrease for PT addition (−1.46 ± 0.47 nm) and the increase for DT addition (+0.31 ± 0.61 nm) can be attributed to thiol binding at the GNP surface (Table 1). Both the GNP-PC-PT (Figure S3) and GNP-PC-DT (Figure S4) centroids respond linearly with alkanethiol concentration at low concentrations. Above a threshold of 10 μM for PT and 3 μM for DT, PC rearrangement occurs to provide the hybrid membrane with a single leaflet over the thiol.28–31 For PT, saturation occurs between 10 and 33 μM PT and for DT saturation occurs between 3 and 10 μM DT. Because of this two-step process of thiol binding and PC rearrangement, it difficult to pinpoint the exact concentration at which saturation occurs. Both PT and DT addition causes a comparable FWHM increase; +8.30 ± 1.64 for PT and +7.19 ± 2.28 for DT.

Modeling RI changes and sensitivity to solvent RI

A weighted average model was used to predict centroid shifts for each step of the GNP assembly and this model was then used to calculate the anticipated centroid shifts that would result from a change in the RI of the solvent. A weighted average of the RI (ηeff) was calculated based on the RI of each component, its thickness, and its distance from the GNP surface (Figure 5) and this was used to determine the theoretical shift in the LSPR as a function of RI (Table 2). Equation 1 (shown as a black curve in Figure 5) was used to generate a distance-dependent scaling factor for each component that was then multiplied by the RI of each component. For a thin (0.5 nm) layer of citrate, ηeff (1.341) is close to the RI of water. With oleate, the highest RI component used, ηeff increases to 1.431. PC has a lower RI than oleate and also entraps water, resulting in a decrease in ηeff to 1.406. The water layer thickness used in the model was optimized to match the experimental data. The shorter thiol provides a hybrid membrane with ηeff of 1.398 and DT provides a ηeff of 1.414.

Figure 5.

Molecular components of the model used to arrive at ηeff for each GNP coating. Layers were composed of 0.5 nm citrate (orange), 1.5 nm oleate (purple), 2 nm water with a 4 nm PC bilayer (yellow), and a 2 nm PC monolayer with a 0.5 nm PT layer (dark green) or a 1.5 nm DT layer (light green).

Table 2.

Calculated and experimental changes to LSPR of GNPs prepared using 50 μM oleate, 100 μM PC, and 10 μM PT or 10 μM DT. The ηeff values were determined using the model parameters defined in Figure 5. The ΔLSPR calc values were calculated by multiplying the bare GNP sensitivity (83.8 nm/RIU) by each Δηeff. Experimental ΔLSPR data are reported as mean ± SD, n = 3 for PT and DT and n = 6 for others.

| GNP-Citrate | GNP-Oleate | GNP-PC | GNP-PC-PT (10 μM) | GNP-PC-DT (10 μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ηeff (RIU)a | 1.341 | 1.431 | 1.406 | 1.398 | 1.414 |

| Δηeff (RIU) | 0.090 | −0.025 | −0.008 | 0.008 | |

| ΔLSPR Calc (nm) | +7.542 | −2.095 | −0.670 | +0.670 | |

| ΔLSPR (nm) | +4.66 ± 0.12 | −2.38 ± 0.41 | −1.43 ± 0.47 | +0.37 ± 0.61 |

RIU = refractive index units

Each of the ηeff values were then multiplied by the sensitivity of the GNP cores to give the expected centroid shifts for each step of nanoparticle assembly (Δ LSPR Calc in Table 2). The sensitivity of the GNP cores to RI changes was determined to be 83.8 nm / RI unit (RIU) from sucrose addition to bare GNPs (Figure S6). The LSPR shifts generated by the model largely matches the data, although the magnitude of some of the calculated changes are larger than experimental values. The discrepancy for oleate is greatest, possibly because more oleate binds to the GNPs that a simple monolayer. The experimentally determined centroid changes for the GNP-PC-PT is also lower than suggested by the model. The model is half as sensitive as the experimental data. However, as discussed in the supporting information, this may be the result of incomplete conversion to a hybrid membrane at this thiol concentration.

The addition of sucrose to an LSPR sensor is a common approach to examine sensitivity to RI.46 The modeled ηeff values for GNP-PC-DT and GNP-PC-PT were re-calculated using the RI of different sucrose concentrations instead of water as the surrounding medium to give a prediction of the change in LSPR centroid at different sucrose concentrations. These values, reported as Calc LSPR in Table 3, were fit to a line to determine a calculated sensitivity for GNP-PC-PT (34 nm/RIU) and GNP-PC-DT (44 nm/RIU) to RI changes. These sensitivities reveal how the model sensors are expected to respond to changes in RI. Table 3 reports the individual shifts for the model and for experimental data at each sucrose concentration. The experimentally determined sensitivity of GNP-PC-DT (27.5 ± 0.5 nm/RIU) is calculated from a fit of the sucrose data and is lower than the GNP-PC-PT sensitivity (37.8 ± 1.5 nm/RIU). Both experimental sensitivities are somewhat lower than the sensitivities based on the models. Any increases to the actual thickness, such as through interdigitation of an adlayer of PC or a small fraction of GNPs with multi-layered lipids, could explain the slightly decreased sensitivity of the sensor compared to the model. It is noteworthy that the model predicts a 10 nm/RIU difference in sensitivity for the two GNPs which matches the experimental data well and supports the idea of using shorter thiols to increase sensitivity. Furthermore, the addition of a second bilayer to the model GNP-PT-PC drops the sensitivity to 15.8 nm/RIU, substantially lower than the experimental observation, ruling out the presence of multi-layered structures.

Table 3.

RI sensitivity of GNP-PC-DT prepared using 10 μM DT and GNP-PC-PT prepared using 33 μM PT. Observed change in LSPR (Obs LSPR) are centroid averages over 22 min (data mean ± SD reported, n = 6). Predicted changes in LSPR (Calc LSPR) were prepared using model from Figure 5 with the RI from GNP surface to infinity set to the sucrose RI.

| Solvent RI | GNP-PC-PT | GNP-PC-DT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Obs LSPR | Calc LSPR | Obs LSPR | Calc LSPR | |

| 1.3396 | 0.234 ± 0.087 | 0.2933 | 0.214 ± 0.074 | 0.2263 |

| 1.3455 | 0.445 ± 0.071 | 0.5447 | 0.366 ± 0.069 | 0.4274 |

| 1.3504 | 0.628 ±0.096 | 0.7710 | 0.498 ±0.061 | 0.5950 |

| 1.3547 | 0.817 ±0.139 | 0.9553 | 0.622 ±0.062 | 0.7374 |

| 1.3583 | 0.927 ±0.129 | 1.1145 | 0.729 ±0.060 | 0.8631 |

| Sensitivity (nm/RIU) | 37.8 ± 1.5 | 44.0 | 27.5 ± 0.5 | 34.0 |

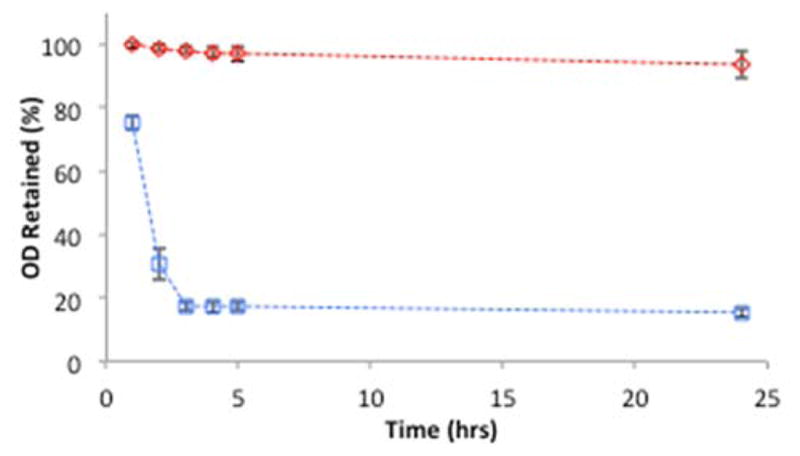

Protein binding observed by LSPR changes

The addition of a PC binding protein was used to demonstrate that the hybrid membrane sensor constructed using PT and PC (the system most sensitive to RI) is able to detect protein binding at the membrane surface. CRP is a critical protein in the innate immune response, that binds to the choline group on PC in a calcium dependent manner.47 We have previously shown that GNP-PC-DT (≤28 nm) binds to CRP when calcium is present.26 When this binding is observed by tracking the LSPR, the addition of CRP causes changes in the centroid, OD, and FWHM (Figure 6) that results from two distinct events.

Figure 6.

LSPR of GNP-PC-PT prepared with 33 μM PT as observed by centroid, OD, and FWHM upon addition of CRP (1 μg/ml) (blue) or buffer (green) at 30 min and 9.5 mM EDTA at 60 min.

The first event is a rapid, small increase in the centroid (+0.5 nm) and OD at 30 min with no change in the FWHM. This change is the result of CRP binding to the membrane surface mediated by calcium. Buffer containing calcium (green) added to GNP-PC-PT shows no LSPR response at 30 min as the lipid coated GNPs are not aggregated by calcium. The second event occurs more slowly during the CRP incubation from 30 to 60 min. As we have previously demonstrated, CRP rearranges the membrane on PC coated GNPs, causing a clustering of the gold cores that is not reversed by sequestration of the calcium using EDTA.25 This second event (core-core clustering) results in a slow and simultaneous increase in centroid, decrease in OD, and increase in FWHM. When EDTA is added (at 60 min), the ability of CRP to bind to PC is eliminated. This reverses the first set of changes, stops the progression of the clustering, but does not reverse the clustering that has occurred consistent with our prior analysis by electron microscopy.25 As a result, the centroid decreases by an amount slightly lower than the initial increase at 30 min. A fraction of the protein has likely bound irreversibly during the incubation period. The OD drops by an amount slightly larger that the initial increase, due to a convolution of changes to the LSPR and a dilution effect of the EDTA solution as can be seen in the Ponceau S data. The FWHM, which rose during the second event, stops rising when EDTA is added as no additional CRP is binding to the PC to cause clustering. The increase to centroid and FWHM and the OD decrease that occurred during this second event are not reversed as these GNP cores are now irreversibly clustered together.25 When buffer alone (green) is added to GNP-PC-PT no change to centroid, OD, and FWHM are observed other than dilution when the large volume of EDTA is added which results in an OD drop.

DISCUSSION

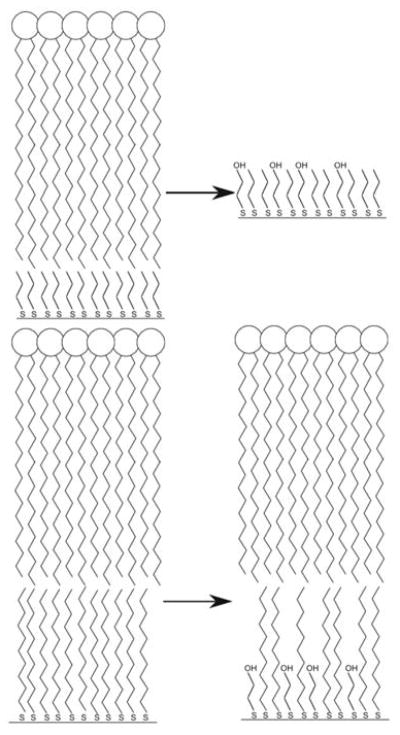

The interaction of the hydrophobic region of the anchoring thiol with PC varies depending on the alkanethiol chain length. The PT interactions with PC are weaker than the DT-PC interactions as seen in the BME assay. BME either displaces the PT but not DT or alternatively, it is possible that BME binding is associative without loss of thiol and the combined DT-BME coating is still able to support a PC leaflet due to the longer hydrophobic chain of the DT (Scheme 1, bottom right). The fact that PT supports a lipid layer confirms the importance of lipid in providing cyanide stability rather than thiol alone and this suggests that tail-tail interactions as opposed to interdigitation are sufficient to stabilize a lipid leaflet, as PT is too short for substantial interdigitation between the thiol and fatty acid regions of the lipid. This is further supported by the increased RI sensitivity of the GNP-PC-PT sensor which can be used to rule out multi-layered structures. Although not shown in Scheme 1, DT on a highly curved surface likely does allow for interdigitation of the PC tails.

Scheme 1.

Possible structural changes occurring at GNP-PC-PT (top) and GNP-PC-DT (bottom) surfaces after addition of BME.

It is reasonable to expect that BME could displace PT, causing instability of the hybrid membrane or that BME binds associatively to the gold, but being comparable in length, the BME hydroxyl groups are exposed and therefore disrupt the tail-tail interactions between PC and thiol (Scheme 1, top right). For DT, which is stable to BME, either the membrane anchored by the longer thiol is more resistant to BME binding (not shown) or BME binding does occur but a gold surface containing a mixture of DT and BME is still capable of supporting a lipid leaflet (Scheme 1, bottom right).

The thickness of the PT/PC hybrid coating is thinner than either the DT/PC coating or the PC bilayer coating, therefore the average RI near the GNP includes more of the surrounding solvent for GNP-PC-PT than for GNP-PC-DT. With water as the solvent, this lowers the average RI experienced by the GNP. This also results in a heightened sensitivity to changes in the solvent RI (vide infra). In the case of GNP-PC-DT the increased solvent proximity is offset by the larger thickness of DT, resulting in an overall increase in RI and therefore centroid. The OD drop is also inequivalent for the same concentration of PT and DT. This change is not due to dilution and instead reflects differences in the peak shapes causing an OD drop.

Lipid layer completeness was confirmed by cyanide stability tests; however, the fractional coverage of the alkanethiol inner layer is more difficult to experimentally determine. The alkanethiol concentration that provides complete cyanide stability may not contain a complete alkanethiol layer. While DT and PT showed different thresholds for cyanide stability, it is not certain that the surface coverage for PT and DT are identical for the same input thiol concentration. Based on the saturation binding experiments (Figure S3 and S4) it appears that less DT is required to achieve saturation and this difference could be due to different binding efficiencies.

While the various coated GNPs do not appear substantially different by eye, careful tracking of the centroid, OD, and FWHM during the coating process reveals changes caused by the change in RI and thickness of the coatings. The changes are consistent with a model in which a PC bilayer entraps water or a partial coating of PC leaving some GNP exposed to solvent. Partial coating is expected in cases where the adhesion energy of lipids binding to the gold are lower than the energy associated with bending the membrane around a small particle.48 Next thiol causes conversion to a hybrid membrane without entrapped water. Although other models could fit the observed LSPR changes, some alternative structures can be ruled out. In particular, multilayered structures or any thicker models, which would be much more insulated from the solvent, can be ruled out based on the sucrose sensitivity.

While many LSPR sensors are based on nanoparticles tethered to a surface,22 there are benefits to the solution approach used here. Surface tethering would minimize the sensing volume and reduce control of curvature if a conformal lipid layer over the surface was used. Precise control of curvature without the competition from regions that are planar or have negative curvature is another unique benefit of this system. GNPs do not have as strong of an LSPR response as silver,13 however, their predictable surface chemistry make them ideal for lipid coating. This is critical in designing sensors with a defined membrane curvature that is determined by the nanoparticle size. While oleate may be incorporated into the PC membrane, the thickness of the resultant membrane is determined by the chain length of the lipid, not the oleate, making this a suitable method for many different lipids.49,50

The use of CRP highlights a challenge and opportunity in using solution based LSPR sensing to detect membrane-protein interactions. CRP binding is seen through two different LSPR changes. Because the time scales of these events differ, it was possible to characterize these events separately. Other proteins that do not induce aggregation may result in changes based simply on binding and concomitant change to RI. CRP highlights the benefits of tracking centroid, OD, and FWHM which made it possible to distinguish protein binding from nanoparticle clustering. Provided the rate of protein-membrane binding is distinct from other GNP changes, this approach should be useful for many proteins. In the case of CRP, EDTA provides a convenient control that reverses membrane binding. For other proteins, the use of BME may function as a control to return the GNP to a state without lipid.

CONCLUSIONS

This versatile sensor is suitable for studying a range of binding events including membrane-substrate interactions, interactions of membranes with small molecules, and protein-membrane interactions. In contrast to membranes on solid supports,23 this approach allows for precise control of curvature in the absence of other surfaces that could complete for binding. This approach is amenable to other nanoparticle sizes and shapes, to different lipid coatings, and to other tethering strategies making is a very generalizable system well suited to answering important biological questions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge helpful discussions with Dr. Marilyn Mackiewicz and Dr. Min Wang. This work was supported by grants from the NSF (CBET-1033161) and the NIH (2R15GM088960-02). Support from NSF (DGE-0742434) is acknowledged (REM).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Serial additions of oleate to GNPs and Ponceau S. Serial additions of PC to GNP and Ponceau S. Serial additions of PT and DT to GNP-PC. Serial addition of sucrose to GNP-PC-PT and to bare GNPs. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Castellana ET, Cremer PS. Solid Supported Lipid Bilayers: From Biophysical Studies to Sensor Design. Surf Sci Reports. 2006;61:429–444. doi: 10.1016/j.surfrep.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubertret B, Skourides P, Norris DJ, Noireaux V, Brivanlou AH, Libchaber A. In Vivo Imaging of Quantum Dots Encapsulated in Phospholipid Micelles. Science. 2002;298:1759–1762. doi: 10.1126/science.1077194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan H, Leve EW, Scullin C, Gabaldon J, Tallant D, Bunge S, Boyle T, Wilson MC, Brinker CJ. Surfactant-Assisted Synthesis of Water-Soluble and Biocompatible Semiconductor Quantum Dot Micelles. Nano Lett. 2005;5:645–648. doi: 10.1021/nl050017l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayerl TM, Bloom M. Physical Properties of Single Phospholipid Bilayers Adsorbed to Micro Glass Beads. A New Vesicular Model System Studied by 2h-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Biophys J. 1990:1–6. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82382-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koole R, van Schooneveld MM, Hilhorst J, Castermans K, Cormode DP, Strijkers GJ, de Mello Donegá C, Vanmaekelbergh D, Griffioen AW, Nicolay K, Fayad ZA, Meijerink A, Mulder WJM. Paramagnetic Lipid-Coated Silica Nanoparticles with a Fluorescent Quantum Dot Core: A New Contrast Agent Platform for Multimodality Imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:2471–2479. doi: 10.1021/bc800368x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed S, Nikolov Z, Wunder SL. Effect of Curvature on Nanoparticle Supported Lipid Bilayers Investigated by Raman Spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:13181–13190. doi: 10.1021/jp205999p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piper-Feldkamp AR, Wegner M, Brzezinski P, Reed SM. Mixtures of Supported and Hybrid Lipid Membranes on Heterogeneously Modified Silica Nanoparticles. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:2113–2122. doi: 10.1021/jp308305y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackiewicz MR, Ayres BR, Reed SM. Reversible, Reagentless Solubility Changes in Phosphatidylcholine-Stabilized Gold Nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:115607. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/11/115607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tam NC, Scott BM, Voicu D, Wilson BC, Zheng G. Facile Synthesis of Raman Active Phospholipid Gold Nanoparticles. Bioconj Chem. 2010;21:2178–2182. doi: 10.1021/bc100386a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castellana ET, Gamez RC, Russell DH. Label-Free Biosensing with Lipid-Functionalized Gold Nanorods. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4182–4185. doi: 10.1021/ja109936h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orendorff CJ, Alam TM, Sasaki DY, Bunker BC, Voigt JA. Phospholipid-Gold Nanorod Composites. ACS Nano. 2009;3:971–983. doi: 10.1021/nn900037k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plant A. Supported Hybrid Bilayer Membranes as Rugged Cell Membrane Mimics. Langmuir. 1999;15:5128–5135. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer KM, Hafner JH. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors. Chem Rev. 2011;111:3828–3857. doi: 10.1021/cr100313v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bohren CF, Huffman DR. Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Link S, El-Sayed MA. Spectral Properties and Relaxation Dynamics of Surface Plasmon Electronic Oscillations in Gold and Silver Nanodots and Nanorods. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:8410–8426. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mock JJ, Barbic M, Smith DR, Schultz DA, Schultz S. Shape Effects in Plasmon Resonance of Individual Colloidal Silver Nanoparticles. J Chem Phys. 2002;116:6755–6759. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hao E, Schatz GC. Electromagnetic Fields around Silver Nanoparticles and Dimers. J Chem Phys. 2004;120:357–366. doi: 10.1063/1.1629280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao JJ, Huang JP, Yu KW. Optical Response of Strongly Coupled Metal Nanoparticles in Dimer Arrays. Phys Rev B: Condens Matter. 2005:71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreibig U, Gartz M, Hilger A. Mie Resonances: Sensors for Physical and Chemical Cluster Interface Properties. Berichte Der Bunsen-Gesellschaft-Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 1997;101:1593–1604. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart ME, Anderton CR, Thompson LB, Maria J, Gray SK, Rogers JA, Nuzzo RG. Nanostructured Plasmonic Sensors. Chem Rev. 2008;108:494–521. doi: 10.1021/cr068126n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoa XD, Kirk AG, Tabrizian M. Towards Integrated and Sensitive Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensors: A Review of Recent Progress. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;23:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anker JN, Hall WP, Lyandres O, Shah NC, Zhao J, Van Duyne RP. Biosensing with Plasmonic Nanosensors. Nat Mater. 2008;7:442–453. doi: 10.1038/nmat2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dahlin A, Zach M, Rindzevicius T, Kall M, Sutherland DS, Hook F. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensing of Lipid-Membrane-Mediated Biorecognition Events. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5043–5048. doi: 10.1021/ja043672o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bingham JM, Hall WP, Van Duyne RP. In: Nanoplasmonic Sensors. Dmitriev A, editor. Springer; New York: 2012. pp. 29–58. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackiewicz MR, Hodges HL, Reed SM. C-Reactive Protein Induced Rearrangement of Phosphatidylcholine on Nanoparticle Mimics of Lipoprotein Particles. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:5556–5562. doi: 10.1021/jp911617q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang MS, Messersmith RE, Reed SM. Membrane Curvature Recognition by C-Reactive Protein Using Lipoprotein Mimics. Soft Matter. 2012;8:7909–7918. doi: 10.1039/C2SM25779C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasch MR, Yu Y, Bosoy C, Goodfellow BW, Korgel BA. Chloroform-Enhanced Incorporation of Hydrophobic Gold Nanocrystals into Dioleoylphosphatidylcholine (Dopc) Vesicle Membranes. Langmuir. 2012;28:12971–12981. doi: 10.1021/la302740j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang JA, Murphy CJ. Evidence for Patchy Lipid Layers on Gold Nanoparticle Surfaces. Langmuir. 2012;28:5404–5416. doi: 10.1021/la300325p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levin CS, Kundu J, Janesko BG, Scuseria GE, Raphael RM, Halas NJ. Interactions of Ibuprofen with Hybrid Lipid Bilayers Probed by Complementary Surface-Enhanced Vibrational Spectroscopies. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:14168–14175. doi: 10.1021/jp804374e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kundu J, Levin CS, Halas NJ. Real-Time Monitoring of Lipid Transfer between Vesicles and Hybrid Bilayers on Au Nanoshells Using Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering (Sers) Nanoscale. 2009;1:114. doi: 10.1039/b9nr00063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sitaula S, Mackiewicz MR, Reed SM. Gold Nanoparticles Become Stable to Cyanide Etch When Coated with Hybrid Lipid Bilayers. Chem Commun. 2008:3013–3015. doi: 10.1039/b801525b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ji XH, Song XN, Li J, Bai YB, Yang WS, Peng XG. Size Control of Gold Nanocrystals in Citrate Reduction: The Third Role of Citrate. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13939–13948. doi: 10.1021/ja074447k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panigrahi S, Basu S, Praharaj S, Pande S, Jana S, Pal A, Ghosh SK, Pal T. Synthesis and Size-Selective Catalysis by Supported Gold Nanoparticles: Study on Heterogeneous and Homogeneous Catalytic Process. J Phys Chem C. 2007;111:4596–4605. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dahlin AB, Chen S, Jonsson MP, Gunnarsson L, Käll M, Höök F. High-Resolution Microspectroscopy of Plasmonic Nanostructures for Miniaturized Biosensing. Anal Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1021/ac901175k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung LS, Campbell CT, Chinowsky TM, Mar MN, Yee SS. Quantitative Interpretation of the Response of Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors to Adsorbed Films. Langmuir. 1998;14:5636–5648. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salabat A, Shamshiri L, Sahrakar F. Thermodynamic and Transport Properties of Aqueous Trisodium Citrate System at 298.15 K. J Mol Liq. 2005;118:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gopal R, Singh JR. Properties of Large Ions in Solvents of High Dielectric Constant. Iii. Refractive Index of Solutions of Some Salts Containing an Ion with a Long Alkyl Chain in Formamide, N-Methylacetamide, N,N′-Dimethylformamide, and N,N′-Dimethylacetamide. J Phys Chem. 1973;77:554–556. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ardhammar M, Lincoln P, Norden B. Invisible Liposomes: Refractive Index Matching with Sucrose Enables Flow Dichroism Assessment of Peptide Orientation in Lipid Vesicle Membrane. Proc Nat Acad Sci, USA. 2002;99:15313–15317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192583499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porter MD, Bright TB, Allara DL, Chidsey CED. Spontaneously Organized Molecular Assemblies. 4. Structural Characterization of N-Alkyl Thiol Monolayers on Gold by Optical Ellipsometry, Infrared Spectroscopy, and Electrochemistry. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:3559–3568. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haes AJ, Zou S, Schatz GC, Van Duyne RP. A Nanoscale Optical Biosensor: The Long Range Distance Dependence of the Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance of Noble Metal Nanoparticles. J Phys Chem B. 2003;108:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jain PK, Huang W, El-Sayed MA. On the Universal Scaling Behavior of the Distance Decay of Plasmon Coupling in Metal Nanoparticle Pairs: A Plasmon Ruler Equation. Nano Lett. 2007;7:2080–2088. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kedem O, Tesler AB, Vaskevich A, Rubinstein I. Sensitivity and Optimization of Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Transducers. ACS Nano. 2011;5:748–760. doi: 10.1021/nn102617d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cremer P, Boxer S. Formation and Spreading of Lipid Bilayers on Planar Glass Supports. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:2554–2559. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keller C, Kasemo B. Surface Specific Kinetics of Lipid Vesicle Adsorption Measured with a Quartz Crystal Microbalance. Biophysical J. 1998;75:1397–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74057-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reviakine I, Brisson A. Formation of Supported Phospholipid Bilayers from Unilamellar Vesicles Investigated by Atomic Force Microscopy. Langmuir. 2000;16:1806–1815. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao Y, Xu S, Zheng X, Wang Y, Xu W. Optical Fiber Lspr Biosensor Prepared by Gold Nanoparticle Assembly on Polyelectrolyte Multilayer. Sensors. 2010;10:3585–3596. doi: 10.3390/s100403585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-Reactive Protein: A Critical Update. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1805–1812. doi: 10.1172/JCI18921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deserno M, Gelbart WM. Adhesion and Wrapping in Colloid-Vesicle Complexes. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:5543–5552. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Inoue T, Yanagihara S, Misono Y, Suzuki M. Effect of Fatty Acids on Phase Behavior of Hydrated Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine Bilayer: Saturated Versus Unsaturated Fatty Acids. Chem Phys Lipids. 2001;109:117–133. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(00)00170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cerezo J, Zuniga J, Bastida A, Requena A. Atomistic Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Interactions of Oleic and 2-Hydroxyoleic Acids with Phosphatidylcholine Bilayers. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:11727–11738. doi: 10.1021/jp203498x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.