ABSTRACT

Neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs) have been widely used to control influenza virus infection, but their increased use could promote the global emergence of resistant variants. Although various mutations associated with NAI resistance have been identified, the amino acid substitutions that confer multidrug resistance with undiminished viral fitness remain poorly understood. We therefore screened a known mutation(s) that could confer multidrug resistance to the currently approved NAIs oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir by assessing recombinant viruses with mutant NA-encoding genes (catalytic residues R152K and R292K, framework residues E119A/D/G, D198N, H274Y, and N294S) in the backbones of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 (pH1N1) and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 viruses. Of the 14 single and double mutant viruses recovered in the backbone of pH1N1, four variants (E119D, E119A/D/G-H274Y) exhibited reduced inhibition by all of the NAIs and two variants (E119D and E119D-H274Y) retained the overall properties of gene stability, replicative efficiency, pathogenicity, and transmissibility in vitro and in vivo. Of the nine recombinant H5N1 viruses, four variants (E119D, E119A/D/G-H274Y) also showed reduced inhibition by all of the NAIs, though their overall viral fitness was impaired in vitro and/or in vivo. Thus, single mutations or certain combination of the established mutations could confer potential multidrug resistance on pH1N1 or HPAI H5N1 viruses. Our findings emphasize the urgency of developing alternative drugs against influenza virus infection.

IMPORTANCE There has been a widespread emergence of influenza virus strains with reduced susceptibility to neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs). We screened multidrug-resistant viruses by studying the viral fitness of neuraminidase mutants in vitro and in vivo. We found that recombinant E119D and E119A/D/G/-H274Y mutant viruses demonstrated reduced inhibition by all of the NAIs tested in both the backbone of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic (pH1N1) and highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 viruses. Furthermore, E119D and E119D-H274Y mutants in the pH1N1 background maintained overall fitness properties in vitro and in vivo. Our study highlights the importance of vigilance and continued surveillance of potential NAI multidrug-resistant influenza virus variants, as well as the development of alternative therapeutics.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza A virus is a segmented RNA virus of negative polarity (1) that causes highly infectious respiratory disease in a wide variety of species, including humans. Influenza A viruses possess two major glycoproteins, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), that protrude from the viral envelope (2). Although mutations in the backbone of influenza viruses may alter their virulence and pathogenicity, major genetic variations are prominent in these surface glycoproteins (3). HA binds to host cell receptors to facilitate viral entry, whereas NA facilitates the spread of infection by releasing newly synthesized virions into neighboring cells, thus making it a major target for anti-influenza drugs (3, 4).

Vaccination is the primary measure used to control influenza virus infections. However, antiviral therapy becomes the paradigm treatment during an outbreak or pandemic because of the lack of vaccines having antigenic compatibility with a usually novel influenza virus strain. The two classes of antiviral drugs available for influenza prophylaxis and treatment are adamantanes (amantadine and rimantadine) and NA inhibitors (NAIs; oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir) (5). Because of the global emergence of adamantane-resistant influenza viruses in recent years (6), NAIs have become the only antiviral drugs available to treat influenza virus infections (7). NAIs target the active site of NA proteins, preventing the cleavage of terminal sialic acid residues on the membrane of the infected cell and thereby inhibiting viral propagation. The analysis of active sites of influenza virus NA has revealed that all of the active residues are highly conserved among all NA subtypes, which are catalytic residues (R118, D151, R152, R224, E276, R292, R371, and Y406 in the N2 numbering, which is used throughout this paper) that interact directly with the substrate, and framework residues (E119, R156, W178, S179, D/N198, I222, E227, H274, E277, N294, and E425) that stabilize the active-site structure (8). In vitro and in vivo studies have revealed mutations in both catalytic and framework residues associated with NAI resistance (5, 9–11).

Recently, the World Health Organization recommended the use of oseltamivir to treat confirmed cases of influenza A virus infection, as well as for postexposure prophylaxis of contacts. However, oseltamivir-resistant variants with the H274Y mutation developed in almost all seasonal H1N1 influenza virus strains between the 2007 and 2009 seasons (12). In 2009, the oseltamivir-resistant seasonal influenza A virus (H1N1) was replaced by the 2009 H1N1 pandemic (pH1N1) virus, which is generally sensitive to oseltamivir, and the resistant phenotype of pH1N1 remained rare (∼1%) worldwide (13–16). However, a remarkable increase of up to 24% in the oseltamivir-resistant variant containing the H274Y mutation was reported during 2011 (17–21), indicating that pH1N1 with the NA H274Y mutation acquired improved viral fitness because of the permissive mutations (21). Furthermore, the presence of additional NA mutations (e.g., I222R/K/V, S246N, and I117V) in combination with H274Y had a synergistic effect on drug resistance, prompting the concern that these pH1N1 variants may have acquired resistance to all NAIs (22–27). In addition, the I222R mutation itself confers reduced susceptibility to multiple NAIs (28, 29). Despite several reports on multidrug-resistant pH1N1, established mutations conferring multidrug resistance to oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir have not been comprehensively screened for. Therefore, it is essential to identify multidrug-resistant influenza virus strains harboring mutations at established catalytic or framework residues. Furthermore, clinical and in vitro studies show that catalytic residues R292 and R152 and framework residues E119, D198, H274, and N294 are commonly replaced after NAI treatments (4, 27).

To profile and characterize the susceptibility of potentially emergent multidrug-resistant pH1N1 and highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 viruses (H5N1) to established mutations in NAIs, we generated various recombinant influenza viruses with mutations in catalytic residues R152K and R292K and framework residues E119A/D/G, D198N, H274Y, and N294S in the pH1N1 and H5N1 backgrounds by the reverse genetic (RG) approach. We also introduced a combination of mutations to determine whether there was a synergistic effect on drug resistance. We tested each single and double mutant virus for sensitivity to oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir; viral growth kinetics; and pathogenic potential in vitro and in vivo. We also assessed the pathogenicity and transmissibility of two multidrug-resistant pH1N1 variants (E119D and E119D-H274Y mutants) in a ferret model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were grown in minimum essential medium with Eagle salts (Lonza) containing 7% fetal bovine serum (FBS). 293T human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% FBS (Gibco). The human pandemic H1N1 virus A/California/04/2009 (CA04, pH1N1) and the RgKorea/W149/06xPR8/34 (H5N1) virus containing the HA- and NA-encoding genes of A/EM/Korea/W149/06 (H5N1) (30) were used for these studies. The multibasic cleavage site of the H5 HA-encoding gene was removed to generate the avirulent type, as described later. Rescued viruses were propagated in 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs and stored in a −80°C freezer until use.

Plasmids and generation of recombinant influenza A viruses.

All eight gene segments of the CA04 (H1N1) virus were cloned into the pHW2000 plasmid vector to generate Rg viruses as described previously (31). First, 8 single mutant and 18 double mutant NA-encoding genes of pH1N1 were generated by site-directed mutagenesis by using the GeneTailor site-directed mutagenesis system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Table 1). In addition, six single mutations and three double mutations were introduced into the NA-encoding gene of the H5N1 virus by site-directed mutagenesis (Table 2). Rescue was attempted for all recombinant viruses in the backbone of pH1N1 or H5N1 as described previously (31). Briefly, 1 μg of the respective gene segments were transfected into six-well plates of cocultured 293T HEK and MDCK cell mixtures (3:1 ratio) with TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The supernatant was harvested after 48 h and injected into 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs for virus propagation. All plasmids and HA- and NA-encoding genes of all rescued viruses were completely sequenced to ensure the absence of unwanted mutations and the presence of the desired gene combinations (Cosmo GeneTech, Seoul, South Korea).

TABLE 1.

NAI susceptibility profiles of pH1N1 mutant viruses as determined by NA inhibition assay

| Mutation(s) | Viability | Mean IC50 (nM) ± SDa (ratio)b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oseltamivir | Zanamivir | Peramivir | ||

| None (WT pH1N1) | +c | 0.7 ± 0.0 (1) | 0.9 ± 0.1 (1) | 0.3 ± 0.0 (1) |

| E119A | + | 5.4 ± 2.9 (7.7) | 52.1 ± 10.3 (57.9) | 2.1 ± 0.6 (7.1) |

| E119D | + | 16.0 ± 2.0 (22.9) | 525.0 ± 159.8 (583.4) | 31.1 ± 0.7 (103.7) |

| E119G | + | 0.7 ± 0.1 (1) | 101.9 ± 6.1 (113.2) | 24.5 ± 4.1 (81.7) |

| R152K | + | 12.5 ± 3.4 (17.9) | 4.0 ± 1.0 (4.4) | 1.1 ± 0.2 (3.7) |

| D198N | + | 2.9 ± 1.1 (4.2) | 3.7 ± 1.0 (4.1) | 0.9 ± 0.1 (3) |

| H274Y | + | 792.0 ± 25.5 (1,131.4) | 6.8 ± 1.2 (7.5) | 15.2 ± 1.6 (50.6) |

| R292K | + | 23.1 ± 5.7 (33) | 3.1 ± 0.3 (3.5) | 2.2 ± 0.1 (7.5) |

| N294S | + | 44.5 ± 2.0 (63.6) | 1.4 ± 0.3 (1.5) | 0.7 ± 0.1 (2.5) |

| E119A-R152K | − | NAe | NA | NA |

| E119D-R152K | − | NA | NA | NA |

| E119G-R152K | − | NA | NA | NA |

| D198N-R152Kd | + | NA | NA | NA |

| E119A-D198N | − | NA | NA | NA |

| E119D-D198N | − | NA | NA | NA |

| E119G-D198N | − | NA | NA | NA |

| E119A-H274Y | + | 820.9 ± 92.5 (1,172.7) | 49.9 ± 8.6 (55.5) | 4,373.7 ± 412.4 (14,578.9) |

| E119D-H274Y | + | 2,682.0 ± 436.4 (3,381.4) | 122.1 ± 59.3 (135.6) | >100,000 (>33,333) |

| E119G-H274Y | + | 157.2 ± 15.1 (224.6) | 201.9 ± 103.2 (224.3) | >100,000 (>3,333) |

| R152K-H274Yd | + | NA | NA | NA |

| D198N-H274Y | + | 590.3 ± 102.2 (843.3) | 2.9 ± 0.7 (3.2) | 50.8 ± 9.9 (169.2) |

| R292K-H274Y | − | NA | NA | NA |

| N294S-H274Y | − | NA | NA | NA |

| E119A-R292K | − | NA | NA | NA |

| E119D-R292K | − | NA | NA | NA |

| E119G-R292K | − | NA | NA | NA |

| D198N-R292K | − | NA | NA | NA |

Shown is the NAI concentration that reduced NA activity by 50% relative to that in the reaction mixture containing the virus but no inhibitor. Values were obtained from three independent experiments. The ratio was normalized to that of the WT pH1N1 virus.

The ratio was normalized to that of the parental pH1N1 virus.

A plus sign indicates that the recombinants were recovered by RG, and a minus sign indicates that the recombinants were nonviable.

These mutants were recovered, but sequence analysis revealed a mixed population; therefore, no further evaluation was performed.

NA, not applicable.

TABLE 2.

NAI susceptibility profiles of H5N1 mutant viruses as determined by NA inhibition assay

| Mutation(s) | Mean IC50 (nM) ± SDa (ratio)b |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Oseltamivir | Zanamivir | Peramivir | |

| None (RG H5N1) | 2.2 ± 0.1 (1) | 1.9 ± 0.1 (1) | 1.3 ± 0.1 (1) |

| E119A | 21.8 ± 0.5 (9.9) | 95.9 ± 3.2 (50.5) | 9.5 ± 0.5 (7.3) |

| E119D | 191.6 ± 38.1 (87.1) | 251.1 ± 77.1 (132.2) | 1,867.3 ± 192.9 (1,436.4) |

| E119G | 13.6 ± 1.3 (6.2) | 832.9 ± 68.8 (438.4) | 142.1 ± 14.6 (109.3) |

| H274Y | 97.5 ± 3.7 (44.3) | 1.4 ± 0.2 (0.7) | 30.4 ± 0.2 (23.4) |

| R292K | 0.3 ± 0.1 (0.2) | 1.1 ± 0.0 (0.6) | 0.6 ± 0.2 (0.4) |

| N294S | 24.4 ± 0.3 (11.1) | 1.6 ± 0.0 (0.8) | 1.4 ± 0.1 (1.1) |

| E119A-H274Y | 3,366.7 ± 211.1 (1,530.3) | 95.7 ± 7.6 (50.4) | 3,491.7 ± 864.6 (2,685.9) |

| E119D-H274Y | 351.4 ± 14.4 (159.7) | 123.3 ± 15.3 (64.9) | 2,117.3 ± 303.5 (1,628.7) |

| E119G-H274Y | 1,762.3 ± 76.6 (801.1) | 144.7 ± 27.7 (76.1) | >10,000 (>7,692) |

Shown is the NAI concentration that reduced NA activity by 50% relative to that in the reaction mixture containing the virus but no inhibitor. Values were obtained from three independent experiments.

The ratio was normalized to that of the parental H5N1 virus.

Virus titrations.

The infectivity of the stock viruses recovered by RG was determined in MDCK cells by calculating the number of 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) per milliliter. Briefly, serially 10-fold-diluted viruses were used to infect MDCK cells in 96-well plates prepared 24 h before infection. After 60 h of incubation, cells were observed for cytopathic effects and supernatants were tested by the hemagglutination assay with 0.5% turkey erythrocytes.

NA inhibition assays.

The drug resistance phenotype was identified by NA inhibition assays as described by Potier et al. (32), with minor modifications. Recombinant viruses were standardized to an NA activity 10-fold higher than the background and then incubated with serial 3-fold dilutions of oseltamivir carboxylate (TRC Inc., Canada), zanamivir (TRC Inc., Canada), and peramivir (kindly provided by Green Cross Inc., South Korea). The final concentrations of drugs ranged from 0 to 10 μM. The NA activity of viruses inactivated with Triton X-100 was determined in the absence or presence of NAIs by using the NA-Star influenza virus NA inhibitor resistance detection kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fifty percent inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) were calculated by using nonlinear curve fitting with GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software). Compared with the wild-type (WT) virus, a mutant virus showing a <10-fold IC50 increase was considered to have normal inhibition by the NAIs. However, a virus with a 10- to 100-fold IC50 increase was considered to have reduced inhibition by each NAI, whereas a virus with a >100-fold IC50 increase was considered to have highly reduced inhibition, as previously described (33).

In vitro replication assays.

All recombinant pH1N1 and H5N1 viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001 were used to infect MDCK cells, which were prepared in six-well plates 24 h before infection. Infected cells were incubated at 37°C in an appropriate medium containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin and tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin. Supernatants were harvested at 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h postinfection (hpi), and titers were determined by measurement of the number of TCID50/ml in MDCK cells.

NA enzyme kinetics.

Determination of NA kinetics was based on the method of Yen et al. (34) using the fluorogenic substrate 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-d-N-acetylneuraminic acid (MUNANA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; final concentrations, 0 to 4,000 μM), and all reactions were conducted at 37°C. All H1N1 and H5N1 viruses were standardized to equivalent doses of 105 and 105.5 50% egg infective doses (EID50)/ml. The fluorescence of released 4-methylumbelliferone was measured every 60 s for 1 h in a Victor X3 Multilabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) by using excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 and 460 nm, respectively (35). Enzyme kinetic data were fitted by nonlinear regression to the Michaelis-Menten equation by using GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) to determine the Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) and the maximum velocity (Vmax) of substrate conversion.

In vivo characterization.

To evaluate the pathogenicity of recombinant viruses, groups of five mice were lightly anesthetized and inoculated with 30 μl of 104.0 TCID50 of virus intranasally and their survival and weight changes were monitored for 14 days postinfection (dpi). When the infected mice lost more than 25% of their body weight, they were humanely euthanized. To assess viral growth properties, additional groups of six mice were inoculated by the same method and the lungs of three mice each were harvested at 3 and 6 dpi.

To test the transmissibility of the E119D and E119D-H274Y mutants, groups of ferrets (n = 4) were lightly anesthetized and inoculated with 1 ml of 105.0 TCID50 of virus intranasally, and WT pH1N1 virus was used as a control. At 1 dpi, groups of four naive ferrets were placed adjacent to infected ferrets in cages separated by two stainless steel grids 3.5 cm apart that were designed to allow virus transmission through respiratory droplets. Nasal wash samples were collected at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 dpi from infected ferrets and daily from contact ferrets. Body temperature and weight were checked daily. Two infected ferrets from each group were humanely euthanized to harvest their lungs and tracheas for evaluation of pathology at 5 dpi.

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with and adherence to relevant policies on animal handling as mandated in the Guidelines for Animal Use and Care of the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention (K-CDC). All in vitro and in vivo experiments using genetically modified viruses were appropriately performed in an animal biosafety level 3 facility approved by the K-CDC.

Histopathology.

The ferret lung inoculated with pH1N1 variants (WT and E119D, and E119D-H274Y mutants) were collected at 5 dpi and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Histologic analysis by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (×200 magnification) and immunohistochemistry for the detection of viral nucleoprotein (NP) expression were performed in the pathology laboratory of the Chungbuk National University Hospital, South Korea.

Genetic stability testing of recombinant viruses.

All rescued viruses, including WT pH1N1 and H5N1, were serially passaged in MDCK cells and mice to check the stability of conferred mutations. MDCK cells were prepared in six-well plates 24 h before infection and washed twice with 1× cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mutant viruses at an MOI of 0.01 were incubated and allowed to be absorbed by MDCK cells for 1 h, and then they were washed twice with PBS to remove the remaining viruses from the cell surface. After 48 h, supernatants were infected with the freshly prepared MDCK cells, and this step was repeated four times. All virus groups were passaged in triplicate. Lungs were harvested at 5 dpi and homogenized by using a TissueLyser (Qiagen). Mice were inoculated with supernatants and passaged another four times. NA-encoding genes of serially passaged mutants harvested from MDCK cells or mouse lungs were amplified and sequenced to identify any reverse mutations (Cosmo Genetech).

Statistical analyses.

Statistical data were analyzed by using the Prism 5.0 program (GraphPad Software). Student's t test (two tailed, unpaired) was used to determine the significance of the difference between two sets of values.

RESULTS

Generation of pH1N1 and H5N1 recombinant viruses and their susceptibility to NAIs in vitro.

We first investigated whether amino acid substitutions in known NA active sites (catalytic residues R152K and R292K; framework residues E119A/D/G, D198N, H274Y, and N294S) were viable in the backbone of the pH1N1 representative A/California/04/2009 by the RG method. Of the 26 combinations tested, 14 pH1N1 mutant viruses were successfully recovered by the RG method, but many of the double mutations were in the nonviable recombinant viruses (Table 1). Interestingly, five of the six double mutant viruses recovered were associated with the H274Y amino acid substitution, the most frequent mutation in pH1N1 associated with oseltamivir resistance in the N1 subtype (Table 1) (27). However, direct sequencing of the D198N-R152K and R152K-H274Y variants revealed that the K152 population was mixed with the WT R152 population. Thus, these viruses were not characterized further. These results indicate that the double mutation confers lower compatibility than single mutations in the pH1N1 background, but viability increases in combination with the H274Y mutation.

In NA inhibition assays, the H274Y mutation conferred highly reduced inhibition by oseltamivir (1,131.4-fold IC50 increase). Also, the H274Y mutation reduced inhibition by peramivir by 50.6-fold. All of the E119A/D/G mutations conferred mainly reduced to highly reduced inhibition by zanamivir, although the other viruses of the N1 subtype with single mutations (R152K, D198N, H274Y, R292K, and N294S) remained sensitive to zanamivir (<10-fold IC50 increases) (Table 1). The single mutations E119D/G and H274Y conferred reduced inhibition by more than two of the NAIs tested, whereas the D198N mutation moderately affected the susceptibility to NAIs tested in the pH1N1 background. Of note, the E119D mutation was associated with reduced susceptibility to all of the NAIs tested: reduced inhibition by oseltamivir (22.9-fold IC50 increase) and highly reduced inhibition by zanamivir and peramivir (583.4- and 103.7-fold IC50 increases, respectively) (Table 1). The R152K and R292K mutants exhibited reduced inhibition by oseltamivir (17.9-fold and 33-fold IC50 increases, respectively) but showed normal inhibition by zanamivir and peramivir (<5-fold IC50 increases). The N294S mutation also conferred reduced inhibition by oseltamivir (63.6-fold IC50 increase; Table 1).

The H274Y substitution was introduced into most of the recovered double mutant viruses with E119A/D/G or D198N mutations. Notably, the combination of E119A/D/G mutations with H274Y had synergistic effects, which allowed the retention of highly reduced inhibition by oseltamivir (1,172.7-, 3,381.4-, and 224.6-fold IC50 increases, respectively) as conferred by the H274Y single mutation, as well as to zanamivir (55.5-, 135.6-, and 224.3-fold IC50 increases, respectively), as conferred by the E119A/D/G single mutations. Further, the double mutations greatly reduced inhibition by peramivir (14,578.9-, >33,333-, and >33,333-fold IC50 increases, respectively). The D198N-H274Y double mutant and the H274Y mutant showed similarly reduced inhibition by oseltamivir, but the D198N-H274Y double mutant exhibited a >3-fold lower reduction of inhibition by peramivir than the single H274Y mutation (50.6- versus 169.2-fold, respectively). These results confirmed that multidrug resistance could be acquired through both single and combined mutations and revealed that some double mutants (e.g., E119A/D/G-H274Y) can show extremely reduced inhibition by all three NAIs.

We also assessed the effects of the sites with the potential to confer NAI resistance (E119A/D/G, H274Y, R292K, and N294S) on the H5N1 virus, whose NA subtype is similar to that of pH1N1 (Table 2). Corresponding to the IC50s in the pH1N1 background, the E119D mutation in the H5N1 backbone conferred a remarkable increase in resistance to all of the NAIs (Table 2). All of the E119A/D/G mutations also conferred reduced to highly reduced inhibition by zanamivir (50.5-, 132.2-, and 438.4-fold IC50 increases, respectively), whereas the remaining single mutations (H274Y, R292K, and N294S) did not (<1-fold IC50 increases). The E119D/G and H274Y mutations were also associated with reduced susceptibility to more than two of the NAIs tested in H5N1, as seen in pH1N1. The H274Y mutation in H5N1 conferred moderately reduced inhibition by oseltamivir (44.3-fold IC50 increase), although the mutation conferred highly reduced inhibition in the pH1N1 background. Notably, the H274Y mutation combined with the E119A/D/G mutations conferred highly reduced inhibition by all three NAIs, thus having synergistic effects similar to those seen in pH1N1 (Tables 1 and 2). The N294S mutation conferred reduced inhibition by oseltamivir (11.1-fold IC50 increase), and the R292K mutation conferred slightly increased sensitivities to all of the NAIs. These results indicate that a single E119D mutation, as well as the combination of the E119A/D/G and H274Y mutations, in both N1 subtype strains can confer reduced to highly reduced resistance to multiple NAIs.

Growth kinetics and NA enzyme activities of pH1N1 and H5N1 recombinant viruses in vitro.

To assess the effects of the induced mutations on viral fitness, we studied the growth kinetics of individual mutants in MDCK cells. The replication rate of the E119A mutant was slightly higher than that of parental pH1N1 at 48 hpi, although the peak titers of the two strains were similar at 72 hpi (Fig. 1A). However, the E119D and E119G mutants had impaired growth compared with parental pH1N1 (E119D and E119G versus parental pH1N1: 4.9, 4.7, and 6.2 log10TCID50/ml at peak, respectively). The peak viral titer of the N294S mutant was lower than that of parental pH1N1 (5.2 versus 6.2 log10TCID50/ml, respectively). However, the R152K, D198N, H274Y, and R292K mutants did not show a significant difference in viral growth from parental pH1N1 (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Replication kinetics of recombinant pH1N1 viruses in vitro. Cells were infected with 12 recombinant viruses and WT pH1N1 at an MOI of 10−3. Cell culture supernatant were collected at 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h postinfection, and titers were determined by measurement of log10TCID50/ml. (A and B) Growth curves of eight single mutants in MDCK cells. (C) Growth curves of four double mutants in MDCK cells. Error bars show the standard errors of the means obtained from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001 (compared with the value for WT pH1N1).

Among the double mutants, the E119A-H274Y and D198N-H274Y mutant viruses showed a significantly lower viral growth rate than parental pH1N1 at most of the time points (36, 48, and 72 hpi) (Fig. 1C), but the corresponding single mutant viruses did not show reduced viral growth (Fig. 1A and B). Although the E119D and E119G single mutants showed attenuated viral growth, interestingly, the E119D/G-H274Y double mutations returned viral growth to parental pH1N1 levels. These results indicate that a single or double mutation can alter viral growth, which affects viral fitness, and that a mutation-induced impairment of viral growth can be recovered from by permissive mutations.

To evaluate the viral fitness of H5N1 recombinant viruses and compare the differences in viral fitness conferred by the mutations in a distinct genetic background, the viral growth kinetics of H5N1 recombinant viruses were also studied in MDCK cells. The E119A/D/G mutants showed slightly less viral growth than parental H5N1 (0.5 to 0.9 log10 TCID50 lower at their peaks), although the E119A mutation in pH1N1 slightly increased viral growth (Fig. 1A and 2A). Although the overall viral titer of the H274Y mutant was slightly lower than that of parental H5N1, the H274Y mutant showed a peak titer similar to that of the parental virus at 48 hpi (Fig. 2B). The growth kinetics of H5N1 with the R292K and N294S mutations was different from that of pH1N1 with the same amino acid substitutions (Fig. 1B and 2B). All of the double mutants in the H5N1 backbone displayed attenuated viral replication kinetics (more than 0.5 log10TCID50/ml at their peaks; Fig. 2C), particularly the E119D/G-H274Y mutants, which replicated similarly to the parental virus in the pH1N1 backbone but showed impaired viral replication in the H5N1 backbone (Fig. 1C and 2C). These results suggest that the effects of mutations on viral growth fitness vary with the genetic background despite the same N1 subtype.

FIG 2.

Replication kinetics of recombinant H5N1 viruses in vitro. Cells were infected with nine recombinant viruses and parental H5N1 at an MOI of 10−3. Cell culture supernatants were collected at 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h postinfection, and titers were determined by measurement of log10TCID50/ml. (A and B) Growth curves of six single mutants in MDCK cells. (C) Growth curves of three double mutants in MDCK cells. Error bars show the standard errors of the means obtained from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 (compared with the value for WT pH1N1).

To evaluate the impact of the NA mutations on sialidase activities, the NA enzyme kinetics were examined for each of the recombinant viruses (Fig. 3). Results revealed that most of the pH1N1 and H5N1 NA mutants, particularly the E119D single mutants, had lower enzymatic activities than the respective WT virus strains. Interestingly, though, combination of the H274Y and E119D modifications in NA restored enzymatic activities of the E119D-H274Y double mutant viruses in the pH1N1 (from 6 to 46%) and H5N1 (from 7 to 38%) virus backbones, respectively (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

NA enzyme kinetics of the recombinant influenza viruses. Recombinant viruses in the pH1N1 (A and B) and H5N1 (C and D) backbones were standardized to equivalent doses, and the fluorogenic MUNANA substrate was used at final concentrations of 0 to 4,000 μM. Fluorescence was measured every 60 s for 1 h by using excitation and emission wavelengths of 355 and 460 nm, respectively.

Pathogenicity of pH1N1 and H5N1 recombinant viruses in mice.

Four single mutant (E119A, R152K, H274Y, and R292K) and two double mutant (E119D-H274Y and E119G-H274Y) variants in the pH1N1 backbone retained their growth properties in the lungs of infected mice at 3 and 6 dpi (within ±1 log10TCID50 compared with parental pH1N1; Table 3). The weight loss of mice infected with the R292K and E119D/G-H274Y mutants was within ±5% of the weight changes seen in mice infected with parental pH1N1 over 14 days. Despite the lower (E119D/G) or impaired (E119A-H274Y and D198N-H274Y) replication of some variants in the lungs, the weight losses of mice infected with the mutant viruses and those infected with the parental pH1N1 virus were comparable (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Pathogenicity of NAI-resistant viruses in mice

| Subtype and mutation(s) | Mean lung viral titer (log10 TCID50/ml) ±SEM |

% Weight change (dpi)a | Survival rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 dpi | 6 dpi | |||

| H1N1 | ||||

| None (WT pH1N1) | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | −16.2 (5) | 80 |

| E119A | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 0 (0) | 100 |

| E119D | 4.0 ± 0.0 | 3.8 ± 0.0 | −16.2 (8) | 100 |

| E119G | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | −13.0 (10) | 60 |

| R152K | 5.5 ± 0.0 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 0 (0) | 100 |

| D198N | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | −9.1 (8) | 100 |

| H274Y | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 0 (0) | 100 |

| R292K | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | −16.5 (10) | 60 |

| N294S | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 0 (0) | 100 |

| E119A-H274Y | 2.0 ± 0.0 | <1.3 | −16.9 (6) | 60 |

| E119D-H274Y | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | −17.9 (8) | 80 |

| E119G-H274Y | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | −12.1 (5) | 100 |

| D198N-H274Y | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | −16.6 (6) | 60 |

| H5N1 | ||||

| None (WT H5N1) | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | −14.4 (7) | 60 |

| E119A | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 0 (0) | 100 |

| E119D | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | −4.0 (3) | 100 |

| E119G | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | −14.8 (3) | 100 |

| H274Y | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | −4.0 (5) | 100 |

| R292K | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | −19.7 (6) | 100 |

| N294S | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | −19.0 (5) | 60 |

| E119A-H274Y | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | −11.9 (5) | 80 |

| E119D-H274Y | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | −21.0 (5) | 40 |

| E119G-H274Y | 2.4 ± 0.4 | <1.3 | −3.8 (3) | 100 |

Day postinoculation when the average weight loss peaked.

The E119A, H274Y, and N294S mutants of H5N1 retained the WT efficiency of replication in the lungs of infected mice (Table 3). Only mice infected with the N294S mutant had weight losses, viral titers, and survival rates comparable to those of mice infected with the parental H5N1 virus. Mice infected with the E119D-H274Y mutant showed the most impaired replication kinetics in the lungs but the highest virulence (24.2% weight loss and 40% survival) among the recombinant H5N1 viruses (Table 3). Of the recombinant pH1N1 viruses, the R292K and E119D/G-H274Y variants retained similar viral growth properties in the lungs and caused similar weight losses, representing virulence comparable to that of the parental virus, whereas only the N294S mutant of H5N1 had viral growth properties in the lungs and caused weight losses similar to those of the parental H5N1 virus.

Pathogenicity and transmissibility of multidrug-resistant pH1N1 mutants in ferrets.

Two multidrug-resistant E119D and E119D-H274Y pH1N1 variants were evaluated for their pathogenic potential and transmissibility in ferrets because their viral fitness was comprehensively retained. H&E-stained sections of virus-infected lungs at 5 dpi showed mild to severe intraepithelial infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages, which led to acute to subacute bronchointerstitial pneumonia in all infected groups (Fig. 4A). Comparable NP staining was observed in the lungs of each ferret (Fig. 4B). Thus, these results indicate that the E119D and E119D-H274Y mutants retained the pathogenic properties of the parental pH1N1 virus in ferrets even with the given mutation(s).

FIG 4.

Histopathologic lesions and immunohistochemistry in the lungs of infected ferrets. Ferrets intranasally infected with 105 TCID50 of pH1N1 virus and the E119D and E119D-H274Y mutants were euthanized at 5 dpi. (A) H&E staining of serial lung sections showing bronchointerstitial pneumonia. (B) Immunohistochemistry detecting viral NP in the lungs of ferrets infected with WT or E119D or E119D-H274Y mutant pH1N1 (original magnification, ×200).

All of the ferrets in the infected groups shed the virus in the upper respiratory tract until 5 dpi (Fig. 4). The parental pH1N1 virus was efficiently transmitted to naive contact ferrets through respiratory droplets within 3 days of exposure. Correspondingly, all of the serum samples collected from parental pH1N1-infected and contact ferrets were reactive to the homologous virus at 21 dpi (Table 4). Viruses were transmitted to three naive contact ferrets in the E119D group but none of contact ferrets in the E119D-H274Y group by 12 days postcontact (Fig. 5). Although the time frames of virus shedding were similar in the infected groups, later transmission was observed in the E119D mutant-infected group (5 to 7 dpi) than in the parental pH1N1-infected group (2 to 4 dpi). However, the hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay revealed that all of the contact ferrets in the E119D group generated antibodies against the homologous virus at 21 dpi, including the ferret from which the virus was not recovered, while 50% of the contact ferrets in the E119D-H274Y mutant group showed seroconversion (Table 4). The body temperatures of all of the virus-infected and contact ferrets in the pH1N1 group increased by 1.0 to 1.3°C, but those of contact ferrets in the E119D and E119D-H274Y mutant groups did not increase to the same extent (Fig. 6).

TABLE 4.

Homologous-antibody titers measured by the hemagglutination inhibition test in a study of transmission in ferrets

| Infecting virus, group, and individual ferret | Titer of antibody to CA/04/09 virus |

|

|---|---|---|

| −1 dpi | 21 dpi | |

| pH1N1 | ||

| Infected ferrets | ||

| a | <10 | 1,280 |

| b | <10 | 2,560 |

| c | <10 | NAa |

| d | <10 | NA |

| ACb | ||

| a | <10 | 1,280 |

| b | <10 | 640 |

| c | <10 | 1,280 |

| d | <10 | 2,560 |

| H1 E119D | ||

| Infected ferrets | ||

| a | <10 | 1,280 |

| b | <10 | 640 |

| c | <10 | NA |

| d | <10 | NA |

| AC | ||

| a | <10 | 2,560 |

| b | <10 | 2,560 |

| c | <10 | 1,280 |

| d | <10 | 320 |

| H1 E119D-H274Y | ||

| Infected ferrets | ||

| a | <10 | 1,280 |

| b | <10 | 1,280 |

| c | <10 | NA |

| d | <10 | NA |

| AC | ||

| a | <10 | 80 |

| b | <10 | 640 |

| c | <10 | <10 |

| d | <10 | <10 |

NA, not applicable because of humane euthanization for pathological evaluation of respiratory tracts at 5 dpi.

AC, aerosol contacts.

FIG 5.

Transmission of recombinant pH1N1 viruses via respiratory droplets in ferrets. Groups of four ferrets each were inoculated with 105.0 TCID50 of WT or E119D or E119D-H274Y mutant pH1N1 virus intranasally (left side), and four naive ferrets were placed in the cages adjacent to the infected ferrets but separated by two stainless steel grids 3.5 cm apart at 1 dpi (right side). Nasal wash samples were collected from infected and contact ferrets, and titers were determined by measurement of EID50/ml. Total numbers of positive exposed animals are shown. RD, respiratory droplet.

FIG 6.

Daily monitoring of body temperatures of ferrets. Median changes in the body temperatures of ferrets infected with the WT pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus (CA/04/09) or the E119D or E119D-H274Y mutant virus are shown. Naive contact animals were included and monitored daily for 12 days postinfection. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means. INF, infected; RD, respiratory droplet.

Genetic stability of mutations in pH1N1 and H5N1 viruses in vitro and in mice.

Some artificially conferred mutations cannot be retained during the course of replication in vitro and in vivo (4). Therefore, to verify the stability of the induced mutations during passages in vitro and in vivo, we used all of the viable pH1N1 and H5N1 variants and parental viruses to infect (or inoculate) MDCK cells and mice and passaged them five times. Most of the viruses retained the conferred mutations in the NA-encoding gene after five passages in vitro and in vivo (Table 5). However, full-length sequencing of passaged NA mutants revealed that the E119G, R292K, and E119G-H274Y mutations in the pH1N1 background reverted after the in vitro passages. Reverted mutations or mixed populations with parental sequences were also observed after five passages in mice with the E119G, R292K, R152K, E119G-H274Y, and D198N-H274Y mutations in the pH1N1 background and the E119G-H274Y mutation in the H5N1 background (Table 5). These findings suggest that the conferred mutations are more likely to be unstable during in vivo passages than during in vitro passages, but many of the mutant viruses can maintain their induced mutations that are associated with drug resistance. HA-encoding genes of pH1N1 and H5N1 variants that were passaged in vitro and in vivo were examined to verify whether they obtained any compensatory mutations during passage. While one or two random mutations were found among pH1N1 variants that were passaged in vitro and in vivo, a D222G (H3 numbering) mutation was noted in most of the in vivo-passaged mutant viruses. In contrast, no corresponding HA modifications were found among H5N1 variants (data not shown).

TABLE 5.

Stability of conferred mutations after serial passages in vitro and in vivo

| Subtype and mutation(s) | Amino acid at following position after passage in vitro (in vivo)a: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 119 | 152 | 198 | 274 | 292 | 294 | |

| H1 | ||||||

| None (pH1N1) | E (E) | R (R) | D (D) | H (H) | R (R) | S (S) |

| E119A | A (A) | |||||

| E119D | D (D) | |||||

| E119G | G→Eb (G→E) | |||||

| R152K | K (R, K)c | |||||

| D198N | N (N) | |||||

| H274Y | Y (Y) | |||||

| R292K | K→R (R, K) | |||||

| N294S | S (S) | |||||

| E119A-H274Y | A (A) | Y (Y) | ||||

| E119D-H274Y | D (D) | Y (Y) | ||||

| E119G-H274Y | G→E (G→E) | Y (Y) | ||||

| D198N-H274Y | N (N) | Y (Y, H) | ||||

| H5 | ||||||

| None (RG H5N1) | E (E) | R (R) | D (D) | H (H) | R (R) | S (S) |

| E119A | A (A) | |||||

| E119D | D (D) | |||||

| E119G | G (G) | |||||

| H274Y | Y (Y) | |||||

| R292K | K (K) | |||||

| N294S | S (S) | |||||

| E119A-H274Y | A (A) | Y (Y) | ||||

| E119D-H274Y | D (D) | Y (Y) | ||||

| E119G-H274Y | G (E, G) | Y (Y) | ||||

Position numbers of amino acids are based on N2 numbering.

The induced mutation was changed to the amino acid indicated.

Mixed population with the amino acids indicated.

DISCUSSION

Besides vaccination, two classes of antivirals—adamantanes (M2 ion channel inhibitors) and NAIs—have been approved for the prophylaxis and treatment of influenza virus infections. In the last 2 decades, however, the global emergence of several adamantane-resistant strains has severely compromised the effectiveness of these antivirals. This leaves NAIs as the only therapy in the early stage of an influenza outbreak or pandemic. However, because NA is one of the influenza A virus surface proteins that could evolve under strong selective pressure such as the human immune system and antiviral drugs (36, 37), the virus could develop resistance to the inhibition factors. Furthermore, the widespread use of NAIs raises a growing concern about the potential emergence of multidrug-resistant influenza virus variants. Previous studies revealed that pH1N1 viruses possessing the NA H274Y substitution were comparable to their oseltamivir-sensitive counterparts not only in in vitro NA inhibition assays but also in their pathogenicity and transmissibility in animal models (38, 39). Thus, it is essential to identify mutations that can confer pH1N1 resistance to multiple drugs with undiminished viral fitness in vitro and in vivo. This study provided a profiling of distinct levels of susceptibility to various NAIs altered by one or two mutations in the catalytic (R152 and R292) and framework (E119, D198, H274, and N294) residues in strains of the N1 subtype. It also identified four multidrug-resistant variants (>10-fold increases in the IC50s of all three NAIs) in the pH1N1 backbone, one with a single mutation (E119D) and three with double mutations (E119A/D/G-H274Y). However, the replicative fitness and genetic stability of the E119A/G-H274Y mutants were impaired in vitro (Fig. 1 and Table 4). Although the E119D mutation, which conferred resistance to all of the NAIs, led to impaired viral replicative fitness in the pH1N1 background, the E119D mutant retained its growth properties and pathogenicity in mice. Similarly, Pizzorno et al. observed that the E119V mutation confers resistance to all NAIs but leads to diminished viral fitness in MDCK cells in the pH1N1 background (10). Surprisingly, however, the impaired replicative fitness of the virus with the E119D mutation was restored in both MDCK cells and mice when it was combined with the H274Y mutation in the pH1N1 (CA04) background (Fig. 1 and Table 3), which could correlate to the improved enzymatic activity of the E119D-H274Y double mutant (Fig. 3). Furthermore, serial passages in vitro and in mice confirmed the high genetic stabilities of the E119D single mutant and the E119D-H274Y double mutant in the pH1N1 and H5N1 backgrounds (Table 4).

Although substitutions at E119 occur after drug exposure and are found mostly in the N2 subtype and influenza B viruses (40–42), a previous study (10), as well as our study, showed that inducing E119A/D/G and V mutations in the N1 subtype of influenza A viruses confers NAI resistance, mainly to zanamivir. In vitro, mutations at E119 were generally associated with impaired viral growth in the N1 subtype, which is consistent with previous findings (10). This is probably why the E119 mutation is not as commonly identified as the H274Y mutation in pH1N1. The H274Y mutation is a subtype (N1)-specific mutation that confers highly reduced inhibition by oseltamivir and preserves viral fitness in the pandemic H1N1 2009 virus (39, 43). Because the oseltamivir-resistant pH1N1 variant had permissive mutations in the NA-encoding gene (21), it is very likely that the oseltamivir-resistant pH1N1 virus can circulate continuously and become as dominant as previous seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses (12). This will lead to the alternative use of zanamivir, which is still effective against the oseltamivir-resistant pH1N1 Y274 variant (44), in preference over oseltamivir. E119 mutants have been selected mainly by zanamivir and in some cases by oseltamivir in various subtypes (40–42, 45). Moreover, our drug susceptibility profiling studies revealed that E119 mutations conferred reduced susceptibility mainly to zanamivir, suggesting that selective pressure is exerted by zanamivir in the N1 subtype. Thus, additional selective pressure by zanamivir in the pH1N1 H274Y variant could lead to the acquisition of an additional mutation, especially at the E119 residue, and confer extremely high resistance to all available NAIs without compromising viral fitness, as shown in the present findings. Several case reports found multidrug-resistant variants of pH1N1 associated with the I222R mutation in immunocompromised patients frequently treated with NAIs (28, 46, 47). Furthermore, synergistic effects of the E119D-H274Y mutation found in our study were also observed with the I222R and S246N mutations, which increased multidrug resistance in combination with the H274Y mutation (24, 26), although both the I222R-H274Y and S246N-H274Y double mutant variants had lower resistance to zanamivir than the E119-H274Y mutant did.

Most of the mutations introduced into the H5N1 virus led to a pattern of NAI susceptibility similar to that of the mutant pH1N1 virus (Table 1 and 2). The E119A/D/G mutations in H5N1 conferred resistance, particularly to zanamivir, but the H274Y mutation conferred a median resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir, although the IC50s were 25 times lower than that for the mutant pH1N1 virus. Simultaneous mutations in E119A/D/G and H274Y partially restored the resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir, as shown in the mutant pH1N1 virus, and also conferred high resistance to all of the NAIs. However, even after introducing the same mutations, we found distinct patterns of growth fitness in the pH1N1 and H5N1 backgrounds, even if the NA-encoding genes were of the same subtype. In particular, viral titers of R292K and N294S mutants were markedly different in the H5N1 and pH1N1 backgrounds (Fig. 1B and 2B). Moreover, the E119D-H274Y mutations did not reduce viral titers in the pH1N1 backbone but caused the greatest reduction in replication in the H5N1 backbone (Fig. 1C and 2C). These discrepancies have been seen in NAI-resistant influenza viruses belonging to the same NA subtype, even among pH1N1 viruses that are thus far genetically well conserved (48). R152 and R292 are catalytic residues that have important functions related to NA activity in conjunction with other catalytic and framework residues. Mutations in catalytic residues have a higher fitness cost than those in framework residues because of a considerable drop in NA activity (4). Therefore, low rescue rates in double mutants and mixed populations after recovery might be observed in vivo and in vitro. Considering the importance of balance between the HA and NA activities (34), we hypothesize that the corresponding random HA mutations (e.g., D222G) consequently compensated for the introduced modifications in NA that somehow affected the viral fitness of some NAI-resistant viruses that we generated. Although there seemed to be incoherent findings on lung viral titers relative to the virulence of the H5N1 E119D-H274Y mutant, we also speculate that there may be a distinctive immune response elicited by the mutations which somehow affected immunopathogenesis and can be the subject of further study.

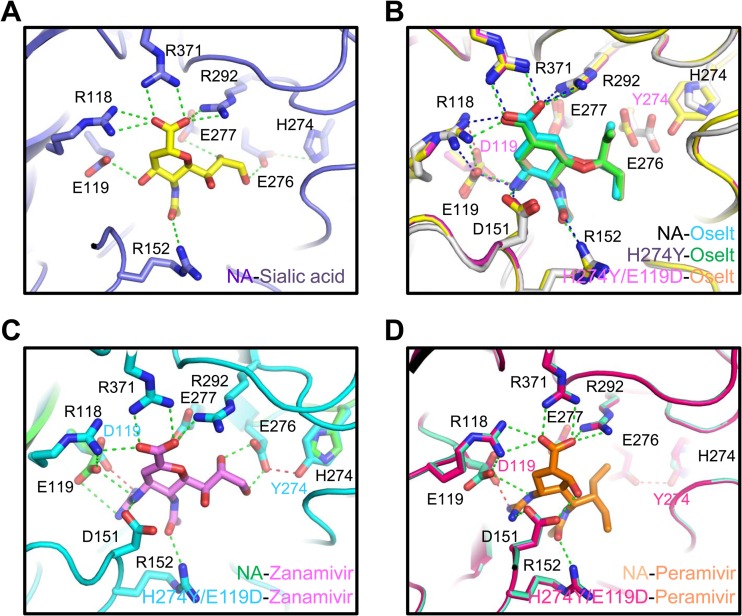

Chemical structures reveal that oseltamivir has a hydrophobic side chain at the C-6 position (Fig. 7B), whereas zanamivir has a glycerol side chain at that position (Fig. 7C). The interaction of oseltamivir with NA involves a conformational change in the carboxyl group of E276 that is oriented away from the hydrophobic group of oseltamivir, making a hydrophobic contact with the Cβ methylene of E276 (Fig. 7B) (44). On the other hand, zanamivir binds with NA by hydrogen bond formation between the carboxyl group of E276 and the hydroxyl groups of the glycerol moiety of the inhibitor, which does not lead to a conformational change (Fig. 7C) (44). The structure of the H274Y mutant and the oseltamivir complex revealed that the substituted tyrosine residue disturbs the lodging of the hydrophobic side chain of oseltamivir in the hydrophobic pocket close to the active site and causes a conformational change in the inhibitor moving from the NA-bound position (Fig. 7B) (44). The structure of the mutant and zanamivir complex showed a small shift in the side chain of E276, enabling the interaction between the inhibitor and E276 without the disruption observed in the sialic acid complexed with WT NA (Fig. 7C) (44). NAI susceptibility measurements revealed that the H274Y mutation also conferred reduced sensitivity to peramivir (Table 1). Peramivir also has a bulky hydrophobic side chain at the C-6 position, which possibly results in unfavorable binding to the side chain of E276 by the H274Y substitution, as seen in oseltamivir (Fig. 7D). On the other hand, the E119D mutation conferred resistance to all of the NAIs, mainly to zanamivir (Table 1), with slightly reduced viral fitness in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 1A and Table 3). In particular, the E119D mutation conferred a dramatically increased resistance to the inhibitor. The E119 residue is critically involved in interactions with the positively charged guanidine group, amino group, and hydroxyl group at the C-4 position of zanamivir, oseltamivir, and sialic acid, respectively (Fig. 7). The replacement of glutamic acid with aspartic acid containing a shorter side chain may cause an unfavorable interaction with the inhibitors and their natural substrate, sialic acid, which may confer a reduced sensitivity to drugs and diminished viral fitness. As mentioned above, the H274Y mutation causes a shift of E276, which may in turn affect the interaction of the mutated E119D residue with its ligands, including sialic acid. This may induce a moderately recovered interaction with the natural substrate but unfavorable interactions with the inhibitors. Therefore, the double mutated NA virus could have higher viral fitness (as much as that of WT pH1N1 in vitro and in mice) than the E119D single mutant virus (Fig. 1 and Table 3).

FIG 7.

Molecular basis of the NA interaction with sialic acid and its inhibitors. The interactions of WT NA with sialic acid (A), oseltamivir (Oselt) (B), zanamivir (C), and peramivir (D) are illustrated by using the structures of Protein Data Bank (PDB) entries 4GZX, 2HU4, 3B7E, and 2HTU, respectively. The structure of the oseltamivir-resistant H274Y mutant and oseltamivir complex is presented by using PDB entry 3CL0. The structures of E119D and H274Y double mutation complexes with zanamivir and peramivir were generated from the WT structures by using the Coot program (49). PDB entry 3CL0 was used to generate the double mutation structure with oseltamivir by using the same program. The residues critical for the interaction between NA and ligands are shown.

Of the drug-resistant viruses tested in this study, the E119D and E119D-H274Y mutants in the pH1N1 background were further evaluated for transmissibility in a ferret model. Fortunately, that E119D-H274Y mutant, which showed high resistance to all of the NAIs, was not efficiently transmitted between ferrets through aerosol contact, even though the mutant largely retained its overall fitness in vitro and in mice. The E119D-H274Y mutations were directly introduced into the virus without adaptation, and thus, a compensatory and/or permissive mutation(s) might be needed to obtain transmissibility in this host. Also, it is necessary to verify whether the mutant could gain a permissive mutation(s) to restore the loss of transmissibility with multidrug resistance. However, the risk posed by the E119D mutant virus should not be overlooked. The E119D mutation was also associated with resistance to all of the NAIs, though it was not as high as that of the E119D-H274Y mutant, which did not require any additional mutations to be transmitted as efficiently as the parental virus in ferrets. Further, pathological assessment of lung and trachea sections did not show a remarkable difference between the mutant and parent viruses. A slight delay in transmission in the E119D group compared with the pH1N1 group is consistent with results of a previous study in which the transmission of an I222R mutant virus was delayed compared with that of the parental strain (29).

Many countries use NAIs to control influenza virus spread and stockpile these drugs as part of preparedness efforts for the next pandemic. However, the potential emergence of multi-NAI-resistant variants caused by the abundant use or even misuse of drugs should not be overlooked. Furthermore, recent clinical studies reporting the emergence of multidrug-resistant variant, as well as our present study showing that mutations conferring high resistance to all of the approved NAIs with moderately diminished viral fitness in vitro and in vivo, support the need for drug resistance screening and intensive surveillance. Our results emphasize that it is not only important to rapidly develop alternative inhibitors that target molecules other than NA (e.g., polymerase inhibitors) to efficiently inhibit viral replication but also critical to establish appropriate guidelines for the use of NAIs for therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project funded by the Ministry of Health (grant A103001), by a National Agenda Project grant from the Korea Research Council of Fundamental Science & Technology, and by the KRIBB Initiative Program (KGM3111013).

We greatly appreciate Cherise Guess for carefully editing our manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Palese P, Shaw ML. 2007. Orthomyxoviridae: the viruses and their replication, p 1647–1689. In Knipe DM, Howley PM (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed, vol 2 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palese P, Schulman JL. 1976. Differences in RNA patterns of influenza A viruses. J Virol 17:876–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, Kawaoka Y. 1992. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev 56:152–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferraris O, Lina B. 2008. Mutations of neuraminidase implicated in neuraminidase inhibitors resistance. J Clin Virol 41:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yen HL, Ilyushina NA, Salomon R, Hoffmann E, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. 2007. Neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant recombinant A/Vietnam/1203/04 (H5N1) influenza viruses retain their replication efficiency and pathogenicity in vitro and in vivo. J Virol 81:12418–12426. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01067-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson MI, Simonsen L, Viboud C, Miller MA, Holmes EC. 2009. The origin and global emergence of adamantane resistant A/H3N2 influenza viruses. Virology 388:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poland GA, Jacobson RM, Ovsyannikova IG. 2009. Influenza virus resistance to antiviral agents: a plea for rational use. Clin Infect Dis 48:1254–1256. doi: 10.1086/598989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colman PM, Varghese JN, Laver WG. 1983. Structure of the catalytic and antigenic sites in influenza virus neuraminidase. Nature 303:41–44. doi: 10.1038/303041a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yen HL, Hoffmann E, Taylor G, Scholtissek C, Monto AS, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. 2006. Importance of neuraminidase active-site residues to the neuraminidase inhibitor resistance of influenza viruses. J Virol 80:8787–8795. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00477-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pizzorno A, Bouhy X, Abed Y, Boivin G. 2011. Generation and characterization of recombinant pandemic influenza A(H1N1) viruses resistant to neuraminidase inhibitors. J Infect Dis 203:25–31. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zurcher T, Yates PJ, Daly J, Sahasrabudhe A, Walters M, Dash L, Tisdale M, McKimm-Breschkin JL. 2006. Mutations conferring zanamivir resistance in human influenza virus N2 neuraminidases compromise virus fitness and are not stably maintained in vitro. J Antimicrob. Chemother 58:723–732. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moscona A. 2009. Global transmission of oseltamivir-resistant influenza. N Engl J Med 360:953–956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0900648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe C, Greenwald I, Chen L. 2010. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 and oseltamivir resistance in hematology/oncology patients. Emerg Infect Dis 16:1809–1811. doi: 10.3201/eid1611.101053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore C, Galiano M, Lackenby A, Abdelrahman T, Barnes R, Evans MR, Fegan C, Froude S, Hastings M, Knapper S, Litt E, Price N, Salmon R, Temple M, Davies E. 2011. Evidence of person-to-person transmission of oseltamivir-resistant pandemic influenza A(H1N1) 2009 virus in a hematology unit. J Infect Dis 203:18–24. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen LF, Dailey NJ, Rao AK, Fleischauer AT, Greenwald I, Deyde VM, Moore ZS, Anderson DJ, Duffy J, Gubareva LV, Sexton DJ, Fry AM, Srinivasan A, Wolfe CR. 2011. Cluster of oseltamivir-resistant 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infections on a hospital ward among immunocompromised patients–North Carolina, 2009. J Infect Dis 203:838–846. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le QM, Wertheim HF, Tran ND, van Doorn HR, Nguyen TH, Horby P. 2010. A community cluster of oseltamivir-resistant cases of 2009 H1N1 influenza. N Engl J Med 362:86–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0910448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Storms AD, Gubareva LV, Su S, Wheeling JT, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Pan CY, Reisdorf E, St George K, Myers R, Wotton JT, Robinson S, Leader B, Thompson M, Shannon M, Klimov A, Fry AM. 2012. Oseltamivir-resistant pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus infections, United States, 2010-11. Emerg Infect Dis 18:308–311. doi: 10.3201/eid1802.111466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lackenby A, Moran GJ, Pebody R, Miah S, Calatayud L, Bolotin S, Vipond I, Muir P, Guiver M, McMenamin J, Reynolds A, Moore C, Gunson R, Thompson C, Galiano M, Bermingham A, Ellis J, Zambon M. 2011. Continued emergence and changing epidemiology of oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1N1)2009 virus, United Kingdom, winter 2010/11. Euro Surveill 16(5):19784 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurt AC, Hardie K, Wilson NJ, Deng YM, Osbourn M, Gehrig N, Kelso A. 2011. Community transmission of oseltamivir-resistant A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza. N Engl J Med 365:2541–2542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1111078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurt AC, Hardie K, Wilson NJ, Deng YM, Osbourn M, Leang SK, Lee RT, Iannello P, Gehrig N, Shaw R, Wark P, Caldwell N, Givney RC, Xue L, Maurer-Stroh S, Dwyer DE, Wang B, Smith DW, Levy A, Booy R, Dixit R, Merritt T, Kelso A, Dalton C, Durrheim D, Barr IG. 2012. Characteristics of a widespread community cluster of H275Y oseltamivir-resistant A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza in Australia. J Infect Dis 206:148–157. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butler J, Hooper KA, Petrie S, Lee R, Maurer-Stroh S, Reh L, Guarnaccia T, Baas C, Xue L, Vitesnik S, Leang SK, McVernon J, Kelso A, Barr IG, McCaw JM, Bloom JD, Hurt AC. 2014. Estimating the fitness advantage conferred by permissive neuraminidase mutations in recent oseltamivir-resistant A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza viruses. PLoS Pathog 10(4):e1004065. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LeGoff J, Rousset D, Abou-Jaoude G, Scemla A, Ribaud P, Mercier-Delarue S, Caro V, Enouf V, Simon F, Molina JM, van der Werf S. 2012. I223R mutation in influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 neuraminidase confers reduced susceptibility to oseltamivir and zanamivir and enhanced resistance with H275Y. PLoS One 7(8):e37095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen HT, Trujillo AA, Sheu TG, Levine M, Mishin VP, Shaw M, Ades EW, Klimov AI, Fry AM, Gubareva LV. 2012. Analysis of influenza viruses from patients clinically suspected of infection with an oseltamivir resistant virus during the 2009 pandemic in the United States. Antiviral Res 93:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pizzorno A, Abed Y, Bouhy X, Beaulieu E, Mallett C, Russell R, Boivin G. 2012. Impact of mutations at residue I223 of the neuraminidase protein on the resistance profile, replication level, and virulence of the 2009 pandemic influenza virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1208–1214. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05994-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurt AC, Leang SK, Speers DJ, Barr IG, Maurer-Stroh S. 2012. Mutations I117V and I117M and oseltamivir sensitivity of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 viruses. Emerg Infect Dis 18:109–112. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.111079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurt AC, Lee RT, Leang SK, Cui L, Deng YM, Phuah SP, Caldwell N, Freeman K, Komadina N, Smith D, Speers D, Kelso A, Lin RT, Maurer-Stroh S, Barr IG. 2011. Increased detection in Australia and Singapore of a novel influenza A(H1N1)2009 variant with reduced oseltamivir and zanamivir sensitivity due to a S247N neuraminidase mutation. Euro Surveill 16(23):19884 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samson M, Pizzorno A, Abed Y, Boivin G. 2013. Influenza virus resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors. Antiviral Res 98:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Vries E, Stelma FF, Boucher CA. 2010. Emergence of a multidrug-resistant pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus. N Engl J Med 363:1381–1382. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1003749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Vries E, Veldhuis Kroeze EJ, Stittelaar KJ, Linster M, Van der Linden A, Schrauwen EJ, Leijten LM, van Amerongen G, Schutten M, Kuiken T, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA, Boucher CA, Herfst S. 2011. Multidrug resistant 2009 A/H1N1 influenza clinical isolate with a neuraminidase I223R mutation retains its virulence and transmissibility in ferrets. PLoS Pathog 7(9):e1002276. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song MS, Oh TK, Pascua PN, Moon HJ, Lee JH, Baek YH, Woo KJ, Yoon Y, Sung MH, Poo H, Kim CJ, Choi YK. 2009. Investigation of the biological indicator for vaccine efficacy against highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 virus challenge in mice and ferrets. Vaccine 27:3145–3152. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffmann E, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, Hobom G, Webster RG. 2000. A DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6108–6113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100133697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potier M, Mameli L, Belisle M, Dallaire L, Melancon SB. 1979. Fluorometric assay of neuraminidase with a sodium (4-methylumbelliferyl-alpha-d-N-acetylneuraminate) substrate. Anal Biochem 94:287–296. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okomo-Adhiambo M, Nguyen HT, Abd EA, Sleeman K, Fry AM, Gubareva LV. 2014. Drug susceptibility surveillance of influenza viruses circulating in the United States in 2011-2012: application of the WHO antiviral working group criteria. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 8:258–265. doi: 10.1111/irv.12215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yen HL, Liang CH, Wu CY, Forrest HL, Ferguson A, Choy KT, Jones J, Wong DD, Cheung PP, Hsu CH, Li OT, Yuen KM, Chan RW, Poon LL, Chan MC, Nicholls JM, Krauss S, Wong CH, Guan Y, Webster RG, Webby RJ, Peiris M. 2011. Hemagglutinin-neuraminidase balance confers respiratory-droplet transmissibility of the pandemic H1N1 influenza virus in ferrets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:14264–14269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marathe BM, Leveque V, Klumpp K, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. 2013. Determination of neuraminidase kinetic constants using whole influenza virus preparations and correction for spectroscopic interference by a fluorogenic substrate. PLoS One 8(8):e71401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bloom JD, Gong LI, Baltimore D. 2010. Permissive secondary mutations enable the evolution of influenza oseltamivir resistance. Science 328:1272–1275. doi: 10.1126/science.1187816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson MI, Holmes EC. 2007. The evolution of epidemic influenza. Nat Rev Genet 8:196–205. doi: 10.1038/nrg2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Memoli MJ, Davis AS, Proudfoot K, Chertow DS, Hrabal RJ, Bristol T, Taubenberger JK. 2011. Multidrug-resistant 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) viruses maintain fitness and transmissibility in ferrets. J Infect Dis 203:348–357. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiso M, Shinya K, Shimojima M, Takano R, Takahashi K, Katsura H, Kakugawa S, Le MT, Yamashita M, Furuta Y, Ozawa M, Kawaoka Y. 2010. Characterization of oseltamivir-resistant 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza A viruses. PLoS Pathog 6(8):e1001079. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baz M, Abed Y, McDonald J, Boivin G. 2006. Characterization of multidrug-resistant influenza A/H3N2 viruses shed during 1 year by an immunocompromised child. Clin Infect Dis 43:1555–1561. doi: 10.1086/508777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barnett JM, Cadman A, Burrell FM, Madar SH, Lewis AP, Tisdale M, Bethell R. 1999. In vitro selection and characterisation of influenza B/Beijing/1/87 isolates with altered susceptibility to zanamivir. Virology 265:286–295. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gubareva LV, Bethell R, Hart GJ, Murti KG, Penn CR, Webster RG. 1996. Characterization of mutants of influenza A virus selected with the neuraminidase inhibitor 4-guanidino-Neu5Ac2en. J Virol 70:1818–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baz M, Abed Y, Simon P, Hamelin ME, Boivin G. 2010. Effect of the neuraminidase mutation H274Y conferring resistance to oseltamivir on the replicative capacity and virulence of old and recent human influenza A(H1N1) viruses. J Infect Dis 201:740–745. doi: 10.1086/650464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins PJ, Haire LF, Lin YP, Liu J, Russell RJ, Walker PA, Skehel JJ, Martin SR, Hay AJ, Gamblin SJ. 2008. Crystal structures of oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus neuraminidase mutants. Nature 453:1258–1261. doi: 10.1038/nature06956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hurt AC, Holien JK, Barr IG. 2009. In vitro generation of neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in A(H5N1) influenza viruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4433–4440. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00334-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eshaghi A, Patel SN, Sarabia A, Higgins RR, Savchenko A, Stojios PJ, Li Y, Bastien N, Alexander DC, Low DE, Gubbay JB. 2011. Multidrug-resistant pandemic (H1N1) 2009 infection in immunocompetent child. Emerg Infect Dis 17:1472–1474. doi: 10.3201/eid1708.102004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nguyen HT, Fry AM, Loveless PA, Klimov AI, Gubareva LV. 2010. Recovery of a multidrug-resistant strain of pandemic influenza A 2009 (H1N1) virus carrying a dual H275Y/I223R mutation from a child after prolonged treatment with oseltamivir. Clin Infect Dis 51:983–984. doi: 10.1086/656439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nguyen HT, Fry AM, Gubareva LV. 2012. Neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in influenza viruses and laboratory testing methods. Antivir Ther 17:159–173. doi: 10.3851/IMP2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]