Abstract

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a common chronic disease with effective therapy, yet interventions to improve outcomes have met with limited success. Though problems in self-management are suspected causes for deterioration, few efforts have been made to understand how self-management could be improved to enhance the lives of affected patients. We conducted semi-structured interviews of 19 patients with CHF treated at an urban United States hospital to elucidate their knowledge and beliefs about CHF and to understand what underlies their self-care routines. A comparison of the themes generated from these interviews with the common-sense model for self-management of illness threats, clarifies how patients’ perceptions and understanding of CHF affected their behaviors. Patients had an acute model of CHF. They did not connect chronic symptoms with a chronic disease, CHF, and did not recognize that these symptoms worsened over time from their baseline of moderate, chronic distress, to a severe state that required urgent care. As a consequence, they often did not manage symptoms on a routine basis and did not, therefore, prevent or minimize exacerbations. When they worsened, many patients reported barriers to reaching their physicians and most reported seeking care primarily in an emergency room.

These in depth responses elucidate how the interplay between acute and chronic models of a chronic illness effect self-management behaviors. These factors play a previously not understood role in patient’s efforts to understand and manage the ever-present but symptomatically variable chronic illness that is CHF. These new concepts illustrate the tools that may be needed to effectively manage this serious and disabling illness, and suggest possible ways to enhance the self-management process and ultimately improve patients’ lives.

Keywords: Heart failure, Self-management, Patient beliefs

Introduction

Nearly 5 million Americans suffer from congestive heart failure (CHF) (American Heart Association, 2002). CHF is expected to double in prevalence by the year 2030 (US Department of Health, 1991), and the number of CHF-related physician visits and hospitalizations are also expected to rise in the coming decades (Stewart, MacIntyre, Capewell, & McMurray, 2002). It is the most common reason for hospitalization and emergency department, or emergency room (ER) visits by persons over 65 years of age in the US. Hospital discharges for CHF have more than doubled from 1979 to 1999 (American Heart Association, 2002). Despite the myriad studies demonstrating the effectiveness of medications in improving survival and quality of life (Packer et al., 2001; CONSENSUS, 1987; SOLVD, 1991; Hunt et al., 2002), the prognosis for individuals with CHF is grim; 75% of the men and 62% of the women die within 5 years of diagnosis (Ho, Anderson, Kannel, Grossman, & Levy, 1993). In a more recent European study, median survival of patients hospitalized for CHF increased between 1986 and 1995 (from 1.2 to 1.6 years), but CHF patients’ prognosis was still poor (MacIntyre et al., 2000). In fact, in contrast to mortality declines for most heart and blood vessel diseases, CHF deaths in the USA increased 145% from 1979 to 1999 (American Heart Association, 2002).

Recent clinical guidelines highlight the need for patients to have a solid understanding of CHF. Understanding is not confined to abstract, “book” knowledge (ACC/AHA Task Force, 1995). To avoid and/or minimize life-threatening exacerbations and maintain quality of life, persons with heart failure must receive and make regular and appropriate use of recommended treatments and adopt life style changes. US Federal health guidelines suggest that clinicians counsel CHF patients to adhere to drug regimens and a very low sodium diet to avoid fluid retention (Hunt et al., 2002). They should also teach patients to regularly monitor early markers of fluid retention that herald a deterioration, including increases in weight, swelling and shortness of breath, and appropriately respond to these markers. For example, patients should weigh themselves daily, contact their providers if their weight changes by more than 3–5 pounds, and adjust their diuretic dose based on weight changes (Konstam, Dracup, & Baker, 1994).

It is clear that many persons with CHF do not initiate and maintain the self-management strategies needed to avoid rapid deterioration of their condition and the need for emergency assistance. Without self-care, their condition typically deteriorates rapidly and patients then seek help at an ER—not the optimal place to treat patients with complex, chronic diseases—or they may require hospitalization for more intensive treatment. Researchers have begun to uncover the obstacles persons withCHF must overcome so they can manage this illness. While practice guidelines have synthesized best evidence and clinical judgment into specific recommendations for clinicians, many patients receive suboptimal care. Important physician factors that may contribute to CHF exacerbations are under-utilization of established therapy such as ACE inhibitors that can reduce morbidity and mortality, and suboptimal education, including low rates of general and dietary counseling (Smith et al., 1998; CONSENSUS, 1987; SOLVD, 1991; IPRO, 1996). Medication and dietary nonadherence (with sodium restriction), inadequate discharge planning and follow-up, lack of social support and not seeking medical attention promptly when symptoms recur also increase the risk of CHF exacerbations (Ni et al., 1999; Ghali, Kadakia, Cooper, & Ferlinz, 1988; Chin & Goldman, 1997; Vinson, Rich, Sperry, Atul, & McNamara, 1990, Tsuyuki et al., 2001; Michalsen, Konig, & Thimme, 1998).

Although these data suggest great potential to improve the care of CHF patients, a compelling need to do so, and specific areas in which efforts can be made to improve CHF-related function, programs designed to achieve these goals have met with limited success. Many of the programs which have shown improvements in patient outcomes have required substantial investments in multi-disciplinary staff time which may prove to be unsustainable and infeasible in practices withlimited resources (Naylor, Brooten, & Jones, 1994; Rich, Beckham, & Wittenberg, 1995; Foranow et al., 1997; Hunt et al., 2002). Newer, less cumbersome programs involving nurse or pharmacist management have shown decreases in hospitalizations and improved quality of life (Blue et al., 2001; Krumholz et al., 2002; Varma, McElnay, Hughes, Passmore, & Varma, 1999; West et al., 1997), but withthe exception of one study (Stewart & Horowitz, 2002), there has been no clear improvement in survival. The modest success of interventions points to the need for a fundamental reexamination of how CHF patients understand and manage their physical conditions.

Interventions conducted to date do not benefit from sufficient data on which potentially modifiable factors are responsible for suboptimal treatment, inadequate self-management and adverse CHF outcomes. Specifically, it is important to determine whether patients understanding and perception of CHF capture the features of the disease that are critical for their participation in their own care. For example, do people withCHF know why it is important to take certain medications, check their weights and avoid salt? Do they attend to and perceive the benefits of these protective procedures? Have patients been taught how to monitor the effectiveness of these strategies? Do they know what to do if the strategies do not appear to be working? Can we identify potentially correctable lacunae in their understanding and perceptions that are responsible for less than optimal self-management?

We combined two approaches to answer these questions. Initially, we conducted and analyzed a small set of patient interviews to elucidate patients’ knowledge and beliefs about CHF, the strategies they use for selfcare, the cues guiding these strategies and barriers they face in trying to maintain their health. We then examined the match between the themes we uncovered, and the factors identified as critical for self-management by the common-sense model of illness (Leventhal, Meyer, & Nerenz, 1980; Leventhal, Diefenbach, & Leventhal, 1992; Brownlee, Leventhal, & Leventhal, 2000). According to this self-regulation model of the mental processes involved in the management of illness threats, self-management reflects how patients’ conceptualize their perceptual experience with a disease.

We began with a hypothesis that three aspects of this model, depth, breadth and coherence, will prove critical for self-management of CHF as a chronic rather than an acute condition. First, chronic management should require that the chronic, low level symptoms and signs which make up the background of the illness experience, be connected to their label, CHF. The bidirectional link between abstract concepts (CHF) and perceptions (symptoms and signs) ought to give depth or meaning to the representation of CHF. In other words, chronic symptoms need to be seen as indicators of CHF if they are to elicit even the simplest, behavioral procedures (Meyer, Leventhal, & Gutmann, 1985; Leventhal & Diefenbach, 1991). Our second hypothesis is that these labeled symptoms need to have breadth, including an understanding of their timeline (symptoms worsen when untreated), consequences (untreated symptoms can be life-threatening), specific causes (buildup of fluids), and that worsening symptoms can be controlled with appropriate action. Our third hypothesis is that the chronic model or representation of CHF (label, symptoms, time-line, etc.) needs to be coherent, or tightly linked to a specific set of procedures (suchas taking medications) to manage bothchronic symptoms and symptom exacerbations. Plans should incorporate concrete cues that elicit action at specific times and places, and appropriate criteria for evaluating action efficacy (Leventhal, 1970). The examination of the qualitative data presented here is designed to provide a direct view of these processes which have been inferred from but not made visible in prior, quantitative analyses (see Brownlee et al., 2000).

The present study used interviews to focus on patient factors that may serve as barriers to effective self-management in response to the picture of fluctuating symptoms that CHF offers to a sick individual. Through comparing these responses to what is currently the most conceptually differentiated model of the cognitive processes involved in self-regulation, we clarified the nature of these barriers, and opened and expanded our view of the dynamics of the processes underlying self-regulation in response to chronic illness. We believe uncovering gaps in knowledge and skills for the self-management of CHF as a chronic condition, will provide an entry point for the development of programs designed to decrease the frequency and severity of episodes of decompensation and maximize quality of life.

Methods

Researchers used a computerized database of inpatient and ambulatory patient encounters to identify patients witha diagnosis of CHF treated at an urban, academic, tertiary care hospital in the United States. We selected a random sample of 50 patients, from those who had been admitted and/or treated for CHF in the hospital, the ED or seen in the internal medicine or cardiology clinics. We stratified the sample by the prior year’s rates of hospitalizations, ED and ambulatory visits. Individuals were excluded if they were under 18, resided in a skilled nursing facility or nursing home, lived outside the local area or were currently hospitalized. We reviewed their medical records to collect demographic information and to ensure that the diagnosis of CHF was accurate. Letters were sent to patients and followed by telephone contact. Seven patients were excluded because they did not speak English and four because they lived too far outside the area to arrange an interview. We were unable to contact 14 patients, three declined participation, one was deceased, and two repeatedly missed interview appointments. We interviewed a total of 19 patients.

Two physicians trained in qualitative research methods conducted and audiotaped semi-structured interviews withparticipants. We used a grounded theory approachto explore respondents’ beliefs and behaviors (Bernard, 1994). Participants chose whether they would be interviewed at home (n = 9) or at the medical center (n = 10). After giving written informed consent for their participation, we asked patients a series of open-ended questions designed to elicit their understanding of CHF and its care. The interviewers explored the patients’ perspectives on their illness, self-care, help-seeking behavior, their attitude toward physicians, their access to care, and their definition of and reaction to a worsening of their condition. To better understand their experiences, interviewers also elicited detailed descriptions of their most recent critical episode of CHF, if one had occurred.

Analysis

Audiotapes of the interviews were transcribed verbatim. Two investigators independently read an initial set of four transcripts making note of specific comments in order to discern themes and develop a coding scheme. Dominant themes were identified by constantly comparing interpretations withthe data to ascertain recurrent themes. All comments were categorized into a branching tree of thematic labels. The investigators then coded four additional interviews to validate these themes and to further refine the branching tree, consolidating or eliminating some themes and placing others into related areas. Finally, all interviews were coded using the modified tree. Comments could be assigned more than one theme and were tallied to assess the frequency of dominant themes and important outlying themes. The final coding scheme categorized a total of 60 themes. To assess the reliability of coding, two investigators independently coded nine interviews, witha calculated inter-rater reliability of 0.9. To assess validity, we reviewed the findings with study participants and with experts in the field and compared them to published information.

Results

The patients ranged in age from 52 to 89 years; nine participants were women, eight were African American, five Latino, and six Caucasian. Using the New York Heart Association Classification to estimate severity of illness, no patients had class I (asymptomatic) CHF; five patients had class II (mild to moderate) CHF; seven had class III (moderate to severe), and seven had class IV (the most severe) CHF (Critical Committee, 1964). Five of the patients had private or HMO physicians, 12 had clinic physicians, two did not have a regular physician and 10 of the 19 regularly saw cardiologists. Eleven patients had Medicare and/or Medicaid insurance, six had private insurance and two were uninsured. We did not collect other sociodemographic information. The mean duration of the interviews was 50 minutes.

Major themes

While we identified 60 themes, three were dominant among this sample of patients: (1) Patients had inadequate information about causes, symptoms, management and consequences of CHF. (2) Patients did not appear to have the tools to prevent, recognize, or act to address the exacerbation of their conditions before their conditions deteriorated quite significantly. (3) When symptoms worsened to the point where patients were aware of danger, they tended to have difficulty navigating systems and overcoming barriers to receiving care outside of an emergency room.

Theme 1: Inadequate knowledge of the causes, symptoms and consequences of CHF—Gaps in depth and breadth

In our sample, patients did not connect CHF or a weak heart to their symptoms, nor did they have a clear understanding of acute and chronic CHF-related symptoms. As related to the common sense model, their representations lacked depth. All but one patient suffered from classical symptoms of CHF including fatigue, dyspnea and edema (Grady et al., 1995), and the majority of participants stated they had fluid buildup. While they often used the presence of these symptoms to define their health, very few patients labeled their illness as heart failure (lack of depth). Instead, many could give no adequate explanation for what caused their condition or the symptoms for which they had recently been treated (lack of breadth). Others linked their symptoms to external influences, suchas stress. Many patients isolated symptoms and attributed them to other illnesses such as dyspnea caused by asthma, unaware they were also related to a weak heart. Interestingly, patients demonstrated a depthof understanding of other conditions. They readily connected symptoms to other illnesses, such as relating chest pain to angina and heart disease.

This group of patients also did not demonstrate a clear understanding of the timeline, causes and consequences of CHF—their representations lacked breadth. Few described CHF as incurable, or very serious. Most patients did not describe CHF as condition that is present in the intervals between acute episodes. Patient 9, a 63 year-old man said:

“They gave me medicine to keep my heart clean, so it (heart failure) shouldn’t happen no more. …as far as what the long term prognosis should be, I have no idea. … for some reason I seem to feel that this is lesser of all the heart conditions and yet, you know, it is a heart condition, plain and simple and so, looking at it like that, I uh I’m pretty much still in the dark as to just what CHF is. I have no idea, really, you know.”

Even when symptoms were severe, patients we interviewed often did not link these symptoms to the label CHF, or to specific plans for action to treat CHF. Patient 11, a 66-year-old woman said:

“When you hear about having heart problems, …you’re supposed to feel maybe a pain in your left arm, maybe a pain in your chest, or pressure. I couldn’t describe what I felt as pressure but I guess it must have been that, uh because I had to struggle in order to talk… I guess it would have been more clear to me if I had chest pain and then I would have said okay, I’ll call and say I’m having chest pain but it didn’t just seem to me like anything came together where I could call.”

Theme 2: Failure to link symptoms with procedures—Gaps in coherence

Without an understanding of the source and implication of their symptoms, it is not surprising that patients in this sample: (a) did not routinely act to prevent exacerbation, and (b) did not recognize and address escalating CHF symptoms.

Theme 2a: Inability to prevent exacerbation

Patients were not armed witha coherent model of CHF as a chronic disease caused by a weak heart. They did not recount that they could minimize fluid build-up and its symptoms through specific self-management procedures (including salt restriction and taking medications), and detect fluid build up at early stages by regularly assessing their weight and symptoms. Though nearly all patients said they needed to restrict salt in their diet, few stated this was to prevent their CHF symptoms, not just to decrease their blood pressure. For some, this dietary restriction seemed less compelling, as they were controlling an asymptomatic condition (hypertension). Patients whose representations incorporated some of the features of a chronic model stated they limited their salt intake if they were experiencing increasing edema. However, some misperceived the procedures they had adopted. They did not know their chosen actions were negatively related to their goals. Patient 2, a 63-year-old man inadvertently used a very high salt substitute. He explained, “I never do [use salt], sincey my pressure went up on me years ago … I don’t use salt like when I cook… I use like a bouillon cube…”

Most persons we interviewed believed their medications were effective and described taking their medicines regularly. Most, however, also thought their medications were to treat other conditions, and in the case of diuretics, thought they only needed to use them when their symptoms (such as leg swelling) were severe (acute model).

Theme 2b: Inability to recognize and address worsening symptoms

Because these patients did not connect their symptoms to an illness witha specific name, associated symptoms and course of action, they did not generally monitor or perceive escalating symptoms of CHF, and did not accurately interpret their meaning (lack of breadth). A deterioration in their condition (short of extreme illness) did not usually trigger a meaningful response. They did not link perceptible cues to action. They were neither encouraged, nor prepared to act to control these changes, or to monitor the efficacy of any procedure that they might perform. Clinical signs of increasing volume or fluid retention, suchas increasing weight, dyspnea or edema, went unappreciated, or were not interpreted as markers of a worsening but treatable condition. Instead, symptoms were seen as vague sensations of multiple possible, but unknown cause, and while bothersome, of unclear or low importance. The consequence was missed opportunities to short circuit the decompensation associated with potentially life-threatening episodes.

Very few patients weighed themselves regularly. One of these, patient 10, did not know this helped assess his fluid balance and he did not know what to do about weight gain—during the prior week he stated he gained 9 pounds, but took no action. The other, patient 13, received almost daily phone calls from her grandson, a cardiologist, directing her to check her weight, and telling her how much diuretic to take for weight gain. She was the only person who took supplemental diuretics to treat minor fluctuations, suchas weight gain or increasing swelling, and to prevent a more dramatic deterioration. She appeared to follow her grandson’s instructions, however, without understanding their rationale.

When participants did detect symptoms, they frequently stated the symptoms were not that severe, or that they were not as serious as symptoms of other medical conditions. These patients did not, therefore, perceive a need to seek help. This led to a balancing act of feeling sick but waiting it out to see if their symptoms would resolve on their own. Most patients had difficulty defining an intermediate zone between what they labeled their poor baseline status and a state of such severe symptomatic illness that they needed to visit an emergency room, or be admitted to a hospital. They reported that their symptoms came on suddenly without warning and that their onset was often during the night. Detailed questioning revealed, however, that many patients had symptoms in this intermediate zone (such as increased shortness of breath) that indicated an impending decompensation, but did not perceive their significance. Patient 11, under the care of a private cardiologist, was asked:

“And how do you make that decision that it’s time to go to the emergency room?”

Patient 11: “…well, all these things seem to happen in the middle of the night so I don’t call doctors.”

Interviewer: “During the week, you said you weren’t feeling that great,…”

Patient 11: “May be I was kind of tired but it just didn’t seem to be anything out of the ordinary.”

Interviewer: “Were there any warning signs earlier?”

Patient 11: “Not that I could detect. Like I said I didn’t feel that great. Oh, I guess that I could have gone to the doctor after I had that collapse on the hallway floor. It might have been a good idea.”

Very few participants believed that they could control their symptoms. Most did not detect when they were in control and when the few actions they took were effective. Controlling symptoms was thought to be their physicians’ responsibility. In fact, the only source of feedback regularly identified about their illness and its control came from powerful medical authorities—physicians at routine visits or in the emergency room. Patient 8, a 74-year-old man explained:

“If I was aware of …how this comes about, I would probably try to prevent it. But I am not aware… you know it’s like withfood, if somebody tells you, look, this thing does you harm, then I don’t eat it.”

We must stress that failure to develop, execute and evaluate preventive or therapeutic action appeared to be associated with having CHF, and was not a characteristic or deficit of the persons we interviewed. While CHF symptoms were of vague etiology and did not have concrete significance, patients’ reported that their other diseases were clearly identifiable, controllable and carried understandable courses of action. Increasing glucose signified worsening diabetes and required more medication, and increasing chest pain meant angina, which if not responsive to medication necessitated seeking medical attention. When a patient 16, in discussing his management of diabetes was asked:

“So insulin needs to be adjusted to control the diabetes… Which medicine needs to be adjusted to control the heart failure?” He responded, “The real key seems to be my diabetes… if you don’t take your medications you get sick. As far as the heart goes, I don’t really have enough knowledge about it and uh, I also do not have a sense of uneasiness.”

Indeed, failure to monitor symptoms and to connect symptoms to action was so pervasive that patients performed little better in identifying and responding more urgent symptoms. Patient 3 said:

“It had been coming on over a period of time…there were little signals, like there has been a couple of nights when I would lay down and I actually couldn’t sleep, you know, I couldn’t really breathproperly and I would have to sit up and those are the warning, the early warning signals that you kind of choose to ignore…”

Theme 3: Barriers to receiving care

When this group of patients recognized the need to seek medical assistance, they did so in the way they perceived to be most appropriate and readily available given their duress. A host of new barriers, however, arose at that point in time. These barriers either precluded development of a clear plan for action, or thwarted execution of their plan, and led to crisis based responding and inefficient use of medical care.

Participants who recognized the need for care of worsening symptoms often could not determine how to obtain it outside of an ER. A minority reported they would call for an appointment, or go to their doctors’ offices. Others would not bother their physicians by calling if they felt worse, especially during the night. Most did not know to call their physicians for help and described the ER as the most effective place to receive care, because tests, technology and treatment were immediately available. Patient 1 lamented going to the ER. “Bad business, you know… You go to jail, you know it’s five years, two years, you gonna be out. When you go to ER, you don’t know if you’re gonna come out or not.” However, he preferred the ER’s doctors. “I don’t think they gonna put any green doctors in the ER,… they wait ‘til he’s polish to put him in there.”

In contrast, several patients described calling their clinic or paging their physician and waiting hours for a response, or not being called back. Others thought they would have to wait weeks to see their physician. Patient 5’s reaction to being told to wait for an appontment was, “I’ll be dead by that time.” Patient 18 summed it up, “In the time it takes to call them, I’m in good hands in the ER.”

Other barriers to receiving timely outpatient care were: the patient should not second guess their doctor, the doctor cannot tell a patient anything by phone, and the patient’s chronic illness left them too debilitated to go to a doctor’s office. Many patients complained that there were too many doctors involved in their care, leaving them uncertain as to who of the cast of characters was in charge and what role each played. Patients became confused when medicines were stopped or started or doses were changed, which often seemed to occur during emergency visits. Several patients further delayed care, afraid that if they were not seen by their primary provider, another doctor would change their regimen for the worse. Patient 6, a 53-year-old woman explained:

“… I don’t like they give me different doctor because you know, they confuse me, they change my medication and they change this and they, I don’t like it, you know. … If I can’t see my doctor, I don’t go to see nobody. Because when I go, the doctor say ‘don’t take this medication,’ and when I see the other doctor, he say, ‘who take away your medication?’…You know, they confuse me. I don’t want them confuse me because I don’t feel better when they confuse me.”

Many patients also attributed decompensations to insurance problems that caused them to run out of medicines, or not to be able to afford to see their physician of choice. In a chronically weak state, some patients preferred to deteriorate to the point of requiring hospital admission to avoid the hassles associated with procuring ambulatory care. Patient 2 described how he lost his insurance and subsequently became ill:

“[The doctor] said well, if this don’t get straightened out, then I can’t see you anymore. I said well the heck with it. I just go on until something happens and I go back to the hospital, somebody gotta take care,…”

Patient 16 described his difficulty affording medications, which were not covered by his insurance:

“I would like to keep a little dignity, I would like to feel that uh I can make it and, unfortunately,… I just can’t afford the medication anymore… I’m getting a little fatalistic about it and just saying well, you know,… I’ve gotten a lot more time than I should have had,… Like I say, I just feel that I am stonewalled now, not by my medical condition, by my social condition,…”

Fortunately, family members or friends were often described as playing an important role in patients’ care. They helped to recognize symptoms, assess the severity of illness and need for urgent help; they interpreted medication regimens and saw to it that diets were followed; they contacted doctors and took note of explanations and instructions, especially when patients were most ill.

Discussion

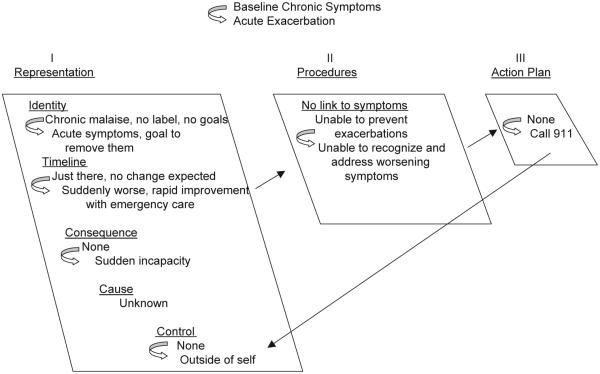

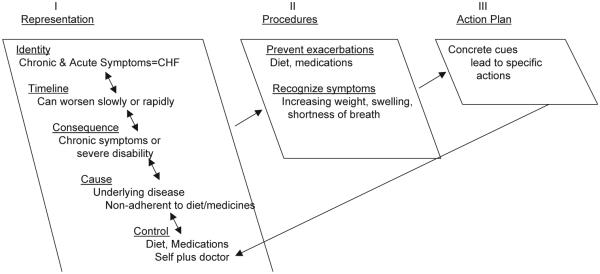

These data reveal that this sample of patients did not appear to have adequate information about CHF, were not given the tools to prevent, thwart, or recognize mild or moderate exacerbations, and had barriers to receiving non-emergent care when their conditions did worsen. The comparison of these three themes with the structure and content of the common sense model suggests that, despite considerable advances in the care of CHF, virtually all of the patients in our sample continued to have poor outcomes, in part because they represented their CHF as an acute condition and treated it as such (Fig. 1). Patients’ focuses on the rapidly changing, dramatic symptoms accompanying an acute deterioration of a health condition, led them to perceive their illness as an acute, episodic condition rather than a chronic illness that requires constant monitoring and self-management (Tulving, 2002). They identified the severe, late onset symptoms of CHF as the key indicators of a need for care, and they typically needed and sought emergency care. Seeking emergency care was consistent and made good sense from the perspective of an acute, life-threatening illness episode. There was little evidence that they had formed a chronic model, that would lead them to perceive gradual changes in their symptoms as worsening CHF and use the changes as cues for taking the specific actions needed to block or slow the deterioration of their conditions (Fig. 2). Instructions for recognizing and managing the chronic features of a disease made little sense when viewed by patients whose experience has committed them to an acute framework. Instead, the ever-present chronic symptoms of CHF formed a bothersome but untreatable background set of events unrelated to medication self-management or to help seeking.

Fig. 1.

Acute, unorganized model of CHF. In the chronic state of baseline bothersome symptoms, the identity of the representation lacks depth; it is not connected to the label, CHF. The representation lacks breadth, as patients fail to monitor change over time in anticipation of consequences with specific causes that can be controlled. It also lacks comprehensiveness, as it is not connected to a set of self-management behaviors. In the acute state, when symptoms become severe, the individual immediately seeks assistance with emergency care.

Fig. 2.

Chronic, organized model of CHF. The identity has depth; its chronic and acute symptoms are connected to the label CHF. Symptoms have a timeline, consequences, cause, and can be controlled by individual behavior. This deep and broad representation elicits self-management procedures to prevent worsening, or address a decompensation at an early stage. These are put into play with specific action plans.

The first theme, that patient’s mental representations of CHF lack depthand breadthwas apparent in reports of difficulty in capturing the meaning of their condition. Diseases differ in duration and severity, fluctuate over time and respond to interventions. Connecting low level background symptoms to a disease category brings with it an expectation that the condition is not static. Labeling symptoms as indicative of a specific illness allows the perception of continuity between mild and severe symptoms and the awareness of a time-line for symptom worsening and therefore, the expectations that specific behaviors (such as using diuretics and avoiding salt), can prevent or delay the onset of potentially catastrophic episodes. The labeling provides a framework for integrating diverse experiences and the development of breadth.

The need for such linkage is apparent from studies of hypertension and HIV. Although hypertension is generally an asymptomatic condition, 90% of patients diagnosed with hypertension falsely attribute symptoms to high blood pressure (Meyer, Leventhal, & Gutmann, 1985). Indeed, when normotensive participants in experimental studies are momentarily led to believe that their blood pressure is elevated, they report the very same symptoms as patients diagnosed with hypertension (Baumann, Cameron, Zimmerman, & Leventhal, 1989). There is symmetry to mental processes: the mind seeks labels for perceived experiences, and perceived experiences for labels (Leventhal & Diefenbach, 1991). The effect of symmetry is so powerful that patients are extremely likely to cease hypertension treatment if the connection of their symptoms (such as headaches) to hypertension is challenged by their practitioners (Meyer et al., 1985). Symptoms clearly provide important prods to medication use. Elderly HIV patients also tend to stop medications when asymptomatic, increasing life-threatening progression to AIDS (Siegel, Schrimshaw, & Dean, 1999).

Persons withCHF are often chronically symptomatic, which could facilitate the connection of symptoms to their underlying illness. A number of cognitive mechanisms, however, pose barriers to the acquisition of the depth and breadth needed for the formation of a chronic model of CHF. Unlike physicians, persons with CHF may attribute symptoms to external rather than internal causes (Jones & Nisbett, 1987). Stress and lack of sleep, for example, provide highly available, external factors as reasonable explanations for chronic symptoms such as fatigue and breathlessness that are characteristic indicators of CHF (Cameron, Leventhal, & Leventhal, 1993). In addition, the causal perceptions of individuals untrained in anatomy and physiology may encourage the attribution of symptoms to their physically most proximal and functionally related organ. Breathlessness, therefore, may be perceived as a problem with the lungs, not the heart, edema of the feet and legs a problem of the limbs (the heart is not in the legs), and fatigue a problem of the mind or brain (due to excessive worry and poor sleep). The pragmatics of everyday reasoning (Morris & Nisbett, 1993), or, the use of normal and highly available heuristics (external attributions, anatomical proximity, etc.) facilitate ignoring or separating the relatively stable background symptoms from the severe symptoms characteristic of acute episodes.

Furthermore, studies of symptom attribution among elderly persons (who most commonly have CHF), have found a strong tendency to attribute chronic, low-grade symptoms suchas swelling and fatigue to age rather than to illness (Stoller, 1994; Leventhal & Prohaska, 1986). In a study of elderly CHF patients, dyspnea began an average of 3 days before hospitalization, and edema, cough, fatigue and weight gain were present on average a week before hospitalization. This suggested to that study’s author that elderly persons evaluate their symptoms as non-acute and non-specific, and delay seeking care until more acute symptoms develop (Friedman, 1997).

In the first theme, problems with CHF management involve cognitive mechanisms, such the misattribution of symptoms to other illnesses or processes. In contrast, the second theme, absence of tools or procedures to prevent, recognize, and act on early decompensations, points to barriers to action. A likely barrier to patients having clear plans for action is that the medical system may not fully educate them. In fact, clinicians may go directly to prescribing actions without explaining to their patients how these actions connect to their underlying chronic illness. For example, physicians may prescribe an increased dose of diuretics without ensuring that their patients recognize that diuretics treat the mild shortness of breath and edema of the legs that results from the accumulation of fluids caused by the poor pumping capability of the heart. Physicians may also not inform patients that the effectiveness of diuretics can be measured by patients weighing themselves daily to monitor fluid loss through weight loss. If clinicians do not fully educate patients, patients cannot shift from an acute to a chronic framework for CHF, and successfully take actions to prevent CHF admissions, suchas such as adhering to low-sodium diets, and seeking medical attention promptly when symptoms recur (Vinson, Rich, & Sperry, 1990). A fully developed, and coherent, chronic model, provides clear, and specific goals for early and sustained actions suchas reducing salt, checking weights and symptoms, and using medications. The fact that patients report that they are performing similar activities to manage their diabetes and angina, indicates that self-care requires not only self-efficacy, but also a concrete plan for enactment.

Our third theme, that patients often cannot overcome barriers to care-seeking prior to dramatic episodes leading to seeking emergency care is consistent with the differentiation between making plans and effectively carrying them out. Effective procedures are brought into play when patients have created plans for their execution, when they have rehearsed and are prepared to take a specific action in a specific place at a specific time (Leventhal, 1970; Gollwitzer, 1999). For example, they have their doctor’s phone number next to their phone and are prepared to call for assistance as soon as they notice the presence and worsening of specific symptoms suchas weight gain in excess of 3 pounds, or increasing dyspnea. The data indicate that the patients that had such plans did not usually know how or when to carry them out. Even those patients who understood that their condition was deteriorating had problems determining whether they could and when they should take action to address the decompensation. Patients described not wanting to bother their doctor, not being sure if their condition would get worse or go away on its own, and feeling they had no choice but to suffer.

Asthmatic patients have found themselves in a similar dilemma when deciding whether to seek urgent care for acute episodes (Becker, Janson-Bjerklie, Benner, Slobin, & Ferketich, 1993). Adult asthmatics described their illness as invisible and unpredictable, responding witha “push–pull dynamic” when struggling between seeking care too soon and delaying formal medical intervention. We uncovered a similar dynamic withthe added predicament that CHF patients often could not even identify their acute state. This confusion was further compounded in our participants, because many felt they had no control over their illness and its care.

Patients with these chronic diseases characterized by fluctuating courses may benefit from efforts that destigmatize calling for help and educate about the benefits of early intervention. In the absence of specific plans for actions at early stages of deterioration, phasic strategies will be perceived as the most effective way of managing repeated, life-threatening episodes. This care-seeking process will reinforce patients’ views that they are suffering from a condition that manifests itself as a series of unexpected, acute episodes unconnected to an underlying and treatable condition that is responsible for their chronically, weakened condition. Successful phasic control by use of emergency settings will reinforce an episodic schema of CHF that will further reduce the likelihood of adopting procedures for controlling CHF during quiescent periods. Thus, confidence in ER treatment can be a barrier to more effective self-management resulting in an unending sequence of life-threatening episodes.

The third theme also highlights the fact that contextual factors, including social influences, access to medical care and information from the health care system, can disrupt or enhance adherence to effective treatment independent of the self-regulation system.

The minority of patients we interviewed who did recognize that their condition had worsened and that they should seek care had a very difficult time actually accessing care. Some were hesitant to get an inadvertent second opinion from a covering doctor for fear that this would lead to a confusing change in medications. Many perceived that they could not contact a doctor or did not have a doctor to call. If they did try to seek help, they often had to negotiate a confusing mixture of physicians and an inadequate social support and insurance system, and opted instead for care in the ED as a short-cut into the medical system. Patients with poor access to care may suffer adverse consequences, such as higher rates of hospitalization for chronic diseases (Bindman et al., 1995). Despite the difficulties in providing optimal care to uninsured persons, we can emphasize early intervention. Other barriers to care may be more amenable to simple solutions. Patients can be taught when and how to contact their providers. Patients with limited prescription coverage can be given less costly medications or enrolled in prescription assistance programs.

It is important to recognize that the gaps in our respondents’ representations about their CHF were not a consequence of indifference: these patients wanted to learn more about their condition. In fact many told us they had hoped the interview was an opportunity to be educated. In one survey of CHF inpatients, patients expressed strong interest in learning about physiology, risk factors, medications, diet and activity, rating these as more important to learn than did their providers (Hagenhoff, Feutz, Sagehorn, & Moranville-Hunziker, 1994). Despite the fact that very few patients could recognize an exacerbation before it progressed to a serious state, we are convinced that persons with CHF can become familiar withtheir disease and markers for flare-ups and use tools to manage both the chronic and acute phases of their condition. Furthermore, reports of success withbrief, educational interventions for the management of myocardial infarction, delivered in hospital and tailored to individual patient’s representation of the disease, indicates that representations are modifiable and a target for intervention by a responsive medical care systems (Petrie, Cameron, Ellis, Buick, & Weinman, 2002).

The qualitative findings reported here suggest several additions to the common-sense model of self-regulation important for the development of successful interventions. First, while confirming the importance connecting symptoms to labels (Meyer et al., 1985), they newly reveal that the disease label also serves to integrate specific symptoms and experiences over time. A person who attributes different CHF-related symptoms to different diseases and causes may not have an organized way to approach her treatment. However, once she understands that her myriad of symptoms and their fluctuating severity all are caused by CHF, she can monitor changes in her condition and adjust her treatment organized around one specific illness. Linking the CHF label to her experienced symptoms also enables her to develop of breadth, or the perception of a timeline for change and the possibility of severe consequences. Second, the data reveal that the tendency to interpret symptoms as indicators of dysfunction in the organ of origin, e.g., breathlessness is a problem with the lungs, not the heart, can be a barrier to linking symptoms to CHF. Finally, the data make clear that coherence (integrating an understanding of the illness, and plans for action) is a property of the entire self-regulation system. Pieces of the representation such the disease’s timeline and consequences make sense when they fit with procedures and action plans for self-management. Coherence should not be treated as a single construct that can be assessed by a single scale. Rather, interventions should be developed and tested that create coherence by linking labels, symptoms, timelines, consequences and concrete treatment plans.

These previously unobserved mechanisms add to our understanding of the dynamics of the self-regulatory processes and the existence of barriers to formulating of representations of CHF as a chronic condition. To rectify the misconceptions about CHF, simple interventions can be designed suchas providing scales for daily weights, ways to assess edema, medications to take for increasing fluid retention, and non-emergency markers that signify a need to seek medical attention. The key is to draw attention to and interconnect the low level, chronic background symptoms and signs of CHF to the gradually worsening of these symptoms and signs with an awareness that these change. In addition, it must be clear that unless managed (in specific actionable ways), symptoms will very likely lead to more threatening consequences in a proximal time frame. This commonsense perspective must also be sensitive to the possibility that self-management, no matter how well performed, may fail and require seeking of medical attention.

Our findings also illustrate that adequate self-management can proceed for patients lacking a coherent, chronic representation of CHF when the patient’s behavior is regulated by an external, social agent. The patient whose cardiologist grandson called daily and directed her to check her weight and then prescribed diuretic for weight gain is a prime example. In the absence of a coherent, chronic model, patients will increasingly rely on external agents. This may be compounded by the fact that patients may prefer their doctors to make decisions, as shown in a study of older cardiac patients (Kennelly & Bowling, 2001). Half the persons they studied believed that controlling symptoms was their physician’s responsibility.

In our study, the only source of feedback regularly identified about their illness and its control came from physicians. Although the good fortune of the grandmother in our sample indicates that external controls can be extremely effective, it is clear that this pathway to control will not be available for most patients. More simply, self-management may be facilitated using by providers, including nurses, pharmacists and social workers, and by family and friends. Social support is also important. Development and execution of care plans for CHF patients, including clinical and social support, help patients maintain their quality of life (Lough, 1996). In one study, changes in social support were significant predictors of changes in health-related quality of life (Bennett et al., 2001). In another, social deprivation increased the chance of a CHF patient being rehospitalized (Struthers, Anderson, Donnan, & Mac-Donald, 2000).

This study has limited generalizability because of its small size and focus on urban dwelling patients. In addition, the respondents had comorbidities whose symptoms may overlap withthose of CHF. Some themes may represent attitudes about other illnesses and may not be specific to CHF. The widespread misunderstanding we encountered may be reflective of chronic diseases in general. The cross-sectional nature of the data, and the difficulties that creates for interpreting causal direction, is another limitation. It is quite possible, for example, that the lack of action-plans to overcome actual and perceived barriers to the effective use of medical care, is responsible for the lack of coherence in patients’ self-management. That their management of other conditions showed greater coherence, and that they were eager to learn more about this ill defined condition, CHF, suggests that they could greatly benefit from educational interventions targeting eachof these deficits.

Conclusion

By soliciting patients’ in-depthperspectives, we uncovered pervasive patient misunderstandings and lack of knowledge that suggest patients need more guidance to better care for their CHF. Our respondents suffered with chronic symptoms, but could not track how their symptoms changed with time, or what caused them to change. They did not understand that symptoms such as swelling and dyspnea were closely related to their salt intake and did not know how to monitor their symptoms over time or respond to these changes.

Patients viewed the “slippery slope” leading from chronic poor function to a severe exacerbation as a rapid downhill slide without clear markers. Close examination of our patients’ reports pointed to the presence of these markers but virtually a complete lack of understanding of their significance and more importantly, of the procedures appropriate for self-management. Our findings suggest that it may be possible to teach patients how to recognize these markers (by checking their weight and edema, for example), and how to either treat themselves with changes in diet or taking medications, or to seek medical care before they develop a life-threatening emergency. By transforming the slippery slope into well-marked stairs, we have the potential of bothimproving the quality of patients’ lives and decreasing their need for hospitalizations and emergency care.

Observations from very small samples, indeed even of single cases, can provide insights into the dynamics of self-regulation processes inferred but not observed in large scale, quantitative data. We believe this qualitative foray does just that. Our 19 participants provided us withvaluable information regarding the structure of their common-sense models of CHF and how these models need to be modified for effective self-care. Patients want information about their CHF and we believe the information they need can be organized and offered in an understandable fashion. It is now important to determine the prevalence of these specific problems in a larger population. With that data in hand, we can proceed to the development of practical interventions that are that are coherent and supportive of effective patient self-management for persons with CHF.

Acknowledgements

The Mount Sinai Medical Center Auxiliary Board (0166-9581). The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (02-54-5251).

We thank the patients we interviewed for their time and ideas and Mark Chassin for his support.

References

- ACC/AHA Task Force Guidelines for the evaluation and management for heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1995;26:1377–1397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Heart Association . Heart stroke and statistical update. American Heart Association; Dallas, TX: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann L, Cameron LD, Zimmerman R, Leventhal H. Illness representations and matching labels with symptoms. Health Psychology. 1989;8:449–469. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.8.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G, Janson-Bjerklie S, Benner P, Slobin K, Ferketich S. The dilemma of seeking urgent care: Asthma episodes and emergency service use. Social Science & Medicine. 1993;17:305–313. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett SJ, Perkins SM, Lane KA, Deer M, Brater DC, Murray MD. Social support and health-related quality of life in chronic heart failure patients. Quality of Life Research. 2001;10:671–682. doi: 10.1023/a:1013815825500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, et al. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274:305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue L, Lang E, McMurray JJV, et al. Randomised controlled trial of specialist nurse intervention in heart failure. British Medical Journal. 2001;323:715–718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7315.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee S, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Regulation, self regulation and regulation of the self in maintaining physical health. In: Boekartz M, Pintrich PR, Zeidner M, editors. Handbook of self-regulation. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 369–416. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron L, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Symptom representations and affect as determinants of care seeking in a community dwelling adult sample population. Health Psychology. 1993;12:171–179. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.3.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin MH, Goldman L. Factors contributing to the hospitalizaiton of patients with congestive heart failure. American Journal Public Health. 1997;87:643–648. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONSENSUS Trial Study Group Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure: Results of the Cooperative NorthScandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS) New England Journal of Medicine. 1987;316:1429–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706043162301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Committee . Diseases of the heart and blood vessels. In: New York Heart Association, editor. Nomenclature and criteria for diagnosis. Little Brown and Co; Boston: 1964. p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Foranow GC, Stevenson LW, Walden JA, Livingston NA, Steimle AE, Hamilton MA, Moriguchi J, Tillisch JH, Woo MA. Impact of a comprehensive heart failure management program on hospital readmission and functional status of patients with advanced heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997;30:725–772. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MM. Older adults’ symptoms and their duration before hospitalization for heart failure. Heart Lung. 1997;26:169–176. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(97)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghali JK, Kadakia MD, Cooper R, Ferlinz J. Precipitating factors leading to decompensation of heart failure: Traits among urban blacks. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1988;148:2013–2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist. 1999;54:493–503. [Google Scholar]

- Grady KL, Jalowiec A, White-Williams C, Pifarre R, Kirklin JK, Bourge RC, Consanzo MR. Predictors of quality of life in patients withadvanced heart failure awaiting transplantation. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 1995;14:2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenhoff BD, Feutz C, ConnV S, Sagehorn KK, Moranville-Hunziker M. Patient education needs as reported by congestive heart failure patients and their nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1994;19:685–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho KK, Anderson KM, Kannel WB, Grossman W, Levy D. Survival after the onset of congestive heart failure in Framingham heart study subjects. Circulation. 1993;88:107–115. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt SA, Baker DW, Chin MH, Cinquegrani MP, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Goldstein S, Gregoratos G, Jessup ML, Noble RJ, Packer M, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Gibbons RJ, Antman EM, Alpert JS, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gregoratos G, Jacobs AK, Hiratzka LF, Russell RO, Smith SC. ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: Executive summary. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplant. 2002;21:189–203. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(01)00776-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPRO A quality improvement study: Congestive heart failure patient education. Feb, 1996. IPRO HCQIP No. 96-02.

- Jones EE, Nisbett RE. The actor and the observer: Divergent perceptions of the causes of behavior. In: Jones EE, Kanouse DE, editors. Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ, USA: 1987. pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kennelly C, Bowling A. Suffering in deference: A focus group sudy of older cardiac patients’ preferences for treatment and perceptions of risk. Quality in Health Care. 2001;10:i23–i28. doi: 10.1136/qhc.0100023... [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstam MA, Dracup K, Baker DW. Heart failure: Evaluation and care of patients with left-ventricular systolic dysfunction. U.S. Agency for HealthPolicy and Research; Rockville, MD: 1994. U.S. Agency for HealthPolicy and Research, Department of Health and Human Services, AHCPR Publ. No. 94-0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumholz HM, Amatruda J, Smith GL, et al. Randomized trial of an education and support intervention to prevent readmission of patients with hear failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;39:83–89. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H. Findings and theory in the study of fear communications. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1970;5:119–186. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Diefenbach M. The active side of illness cognition. In: Skelton JA, Croyle RT, editors. Mental Representation in Health and Illness. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1991. pp. 247–272. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Diefenbach M, Leventhal EA. Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1992;16:143–163. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common sense representation of illness danger. In: Rachman S, editor. Contributions to medical psychology. II. Pergamon Press; New York: 1980. pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal E, Prohaska T. Age, symptom interpretation, and health behavior. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1986;34:185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lough MA. Ongoing work of older adults at home after hospitalization. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1996;23:804–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre K, Capewell S, Stewart S, Chalmers JWT, Boyd J, Finlayson A, Redpath A, Pell JP, McMurray JJV. Evidence of improving prognosis in heart failure: Trends in case fatality in 66,547 patients hospitalized between 1986 and 1995. Circulation. 2000;102:1126–1131. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.10.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D, Leventhal H, Gutmann M. Commonsense models of illness: The example of hypertension. Health Psychology. 1985;4:115–135. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalsen A, Konig G, Thimme W. Preventable causative factors leading to hospital admission with decompensated heart failure. Heart. 1998;80:437–441. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.5.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MW, Nisbett RE. Tools of the Trade: Deductive schemas taught in psychology and philosophy. In: Nisbett RE, editor. Rules for reasoning. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1993. pp. 228–256. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1994;120:999–1006. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-12-199406150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni H, Nauman D, Burgess D, Wise K, Crispell K, Hershberger RE. Factors influencing knowledge of and adherence to self-care among patient with heart failure. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999;159:1613–1619. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.14.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer M, Coats AJ, Fowler MB, Katus HA, Kurm H, et al. Effect of Carvedolol on survival in severe chronic heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344:1651–1658. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie KJ, Cameron LD, Ellis CJ, Buick D, Weinman J. Changing illness perceptions after myocardial infarction: An early intervention randomized controlled trial. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:580–586. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, et al. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients withcongestive heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;333:1190–1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K, Schrimshaw EW, Dean L. Symptom interpretation and medication adherence among late middle-age and older HIV-infected adults. Journal of Health Psychology. 1999;4:247–257. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith NL, Psaty BM, Bertram P, Garag R, Gottdiener JS, Heckbert SR. Temporal patterns in the medical treatment of congestive heart failure with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor in older adults, 1989 through 1995. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158:1074–1080. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.10.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOLVD Investigators Effect of enalapril on survival in patients withreduced left ventricular ejection fraction and congestive heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;325:293–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S, Horowitz JD. Home-based intervention in congestive heart failure: Long-term implications on readmission and survival. Circulation. 2002;105:2861–2866. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000019067.99013.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Capewell S, McMurray JJV. Heart failure and the aging population: An increasing burden in the 21st century? Heart. 2002;89:49–53. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoller P. The impact of symptom interpretation on physician utilization. Journal of Aging and Health. 1994;6:507–534. doi: 10.1177/089826439400600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struthers AD, Anderson G, Donnan PT, MacDonald T. Social deprivation increases cardiac hospitalisations in chronic heart failure independent of disease severity and diuretic non-adherence. Heart. 2000;83:12–16. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuyuki RT, McKelvie RS, Arnold MO, Avezom A, Barretto AC, Carvalho AC, Isaac DL, Kitching AD, Leopoldo SP, Teo KK, Yusuf S. Acute precipitants of congestive heart failure exacerbations. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2001;161:2337–2342. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.19.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E. Fiske ST, Schacter DL, Zahn-Waxler C, editors. Episodic memory: From mind to brain. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health, Human Services . Aging in America: Trends and projections. US Department of Healthand Human Services; Washington, DC: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Varma S, McElnay JC, Hughes CM, Passmore AP, Varma M. Pharmaceutical care of patients with congestive heart failure: Interventions and outcomes. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:860–869. doi: 10.1592/phco.19.10.860.31565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson JM, Rich MW, Sperry JC, Atul SS, McNamara T. Early readmission of elderly patients withcongestive heart failure. Journal of American Geriatrics Society. 1990;38:1290–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JA, Miller NH, Parker KM, Senneca D, Ghandour G, Clark M, Greenwald G, Heller RS, Fowler MB, DeBusk RF. A comprehensive management system for heart failure improves clinical outcomes and reduces medical resource utilization. American Journal of Cardiology. 1997;79:58–63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00676-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]