Abstract

The genetic control of susceptibility to tuberculosis in DBA/2J and C57BL/6J mice is complex and influenced by at least 4 Tuberculosis resistance loci (Trl1-4). To further study the Trl3 and Trl4 loci, we have created congenic mouse lines D2.B6-Chr7 and D2.B6-Chr19, in which resistant B6-derived portions of chromosome 7 (Chr.7) and 19 (Chr.19) overlapping Trl3 and Trl4, respectively, were independently introgressed onto susceptible D2 background. Transfer of B6-derived Trl3 Chr.7 segment significantly increased resistance of D2 mice, as measured by reduced pulmonary microbial replication at day 70, and increased host survival following aerosol infection. However, transfer of B6-derived Chr.19 (Trl4) onto D2 mice did not increase resistance by itself and does not improve on the protective effect of Chr.7. Further study of the protective effect of Trl3 in D2.B6-Chr7 mice indicates that it does not involve modulation of timing or magnitude of Th1 response in the lung, as investigated by measuring the number of antigen-specific, IFN-γ producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Rather, Trl3 appears to affect the intrinsic ability of activated macrophages to restrict intracellular mycobacterial replication in an NOS2-independent fashion. Microarray experiments involving parental and congenic mouse lines identified a number of genes in the Trl3 interval on Chr.7 the level of expression of which prior to infection or in response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is differentially regulated in a parental haplotype dependent fashion. This gene list represents a valuable entry point for the identification and prioritization of positional candidate genes for the Trl3 effect on Chr.7.

Keywords: monocytes/macrophages, rodent, gene regulation, lung, bacterial

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, remains one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality by an infectious agent worldwide. At present, it is estimated that one-third of the world population is infected with M. tuberculosis (1), with approximately 8 million new cases of active disease per year (2) and 1–1.5 million deaths annually. On the other hand, the fact that only a small fraction of individuals infected with M. tuberculosis go on to develop active disease suggests that humans possess robust mechanisms of innate defenses against M. tuberculosis. Such mechanisms of defense can manifest themselves as genetic variants associated with increased susceptibility to TB in humans and in animal models of infection.

Although a large body of literature supports a complex genetic component of predisposition to TB in humans, this phenomenon is very difficult to study in humans, and identifying the genes involved has so far not been possible (3). On the other hand, the parallel study of inbred and mutant stocks of mice has shed light on the cell types, and physiological and biochemical pathways involved in innate defenses against TB. This has been achieved primarily by the “reverse genetics” approach where the role of individual genes is tested by infecting mice bearing loss-of-function mutations at the corresponding locus (4–7). Furthermore, inbred strains of mice vary dramatically in their degree of susceptibility to pulmonary TB, and genetic studies of such differences are starting to provide insight into mechanisms of host defense against M. tuberculosis (see reference (3) for a recent review). Inbred strains have been classified as highly susceptible (CBA, C3HeB/FeJ, DBA/2, 129SvJ, I/St) or highly resistant (C57BL/6J, BALB/c, A/Sn) to intravenous or aerosol infection with M. tuberculosis (8, 9). The extreme susceptibility of C3HeB/FeJ mice to aerosol or intravenous infection with M. tuberculosis has been mapped to a single locus on chromosome 1 designated sst1 (supersusceptibility to tuberculosis 1) (10). Studies in congenic mouse lines have established that sst1-encoded resistance is phenotypically expressed as reduced intracellular microbial replication in macrophages that is associated with increased induction of apoptosis in response to M. tuberculosis infection (11). Positional cloning experiments and studies of macrophages from transgenic mice have shown that differential expression of the Ipr1 (Intracellular pathogen resistance 1) gene, coding for the Ifi75 (Interferon-induced protein 75) protein, is responsible for this effect (11). Ifi75 is a homolog of the human protein SP110 (12, 13), an interferon regulated nuclear transcriptional regulator regulated by interferon that appears to modulate gene expression and induction of apoptosis in response to M. tuberculosis infection (11). Recently, a number of genetic modifiers of the Ipr1 effect have been characterized on chromosomes 7, 12, 15, and 17 (14), thereby further highlighting the complexity of genetic susceptibility to TB in C3HeB/FeJ. An association of SP110 alleles with TB in humans has been noted in certain populations (15), while no association could be detected in others (16). Independently, the inter-strain difference in susceptibility to M. tuberculosis of I/St (susceptible) and A/Sn (resistant) was mapped to chromosomes 9 and 3 loci, using infection-induced loss of body mass following infection as a phenotypic marker of susceptibility (17, 18). Susceptibility was associated with decreased IFN-γ production in infected lungs, increased influx of neutrophils in lung tissue, and resistance of neutrophils to M. tuberculosis-induced cell death (19). Again, differential intracellular replication of M. tuberculosis in lung macrophages in vitro was correlated with resistance/susceptibility in vivo, highlighting the role of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear phagocytes in host defenses against M. tuberculosis.

We have studied the differential susceptibility of C57BL/6J (resistant) and DBA/2 (susceptible) strains. Susceptibility in DBA/2J is detected following either intravenous or aerosol infection with M. tuberculosis H37Rv, and is associated with reduced control of pulmonary microbial replication, more rapid inflammatory response in the lungs, and reduced time of survival (20, 21). Linkage analysis by whole genome scanning of informative [B6 X D2] F2 mice using survival time (intravenous infection) and pulmonary microbial load (aerosol infection) as phenotypic markers of susceptibility (20, 21) detected 4 loci (Trl1-4, Tuberculosis resistance loci) that regulate the extent of pulmonary replication of M. tuberculosis [Trl3 (Chr.7; LOD 4.1) and Trl4 (Chr.19; LOD 5.6)] (21), and/or survival following infection [Trl1 (Chr.1; LOD 4.8); Trl2 (Chr.3; LOD 3.9); and Trl3 (Chr.7; LOD 4.7)] (20). All loci account for limited portions of the phenotypic variance, with B6 parental alleles being associated with increased resistance and inherited in a semi-dominant fashion. In one study, [B6 X D2] F2 mice homozygote for B6 alleles at both Trl3 and Trl4 were found to be as resistant as B6 parents, whereas mice homozygote for D2 alleles at both loci were as susceptible as the D2 parents (21).

Trl3 and Trl4 were herein prioritized for further investigation based on the observation that a) Trl3 affects both the rate of pulmonary M. tuberculosis replication and survival to infection, b) Trl4 has the strongest genetic effect detected in independent genome scans, c) there is strong additive effect of Trl3 and Trl4, with their combined effect explaining 38% of the phenotypic variance in [B6 X D2] F2 (20, 21). To study the individual contribution of these two loci on host resistance to M. tuberculosis, we have created congenic mouse lines where the B6 chromosomal segments corresponding to Trl3 and Trl4 were introgressed independently or together onto the genetically susceptible background of DBA/2. We have characterized these congenic mouse lines with respect to penetrance of the Trl3 and Trl4 effect on pulmonary microbial replication and host survival. The mechanistic basis of Trl3 protective effect has been studied by following histopathology, identifying the cell types, and biochemical pathways involved, including an analysis of positional candidates on Chr.7.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

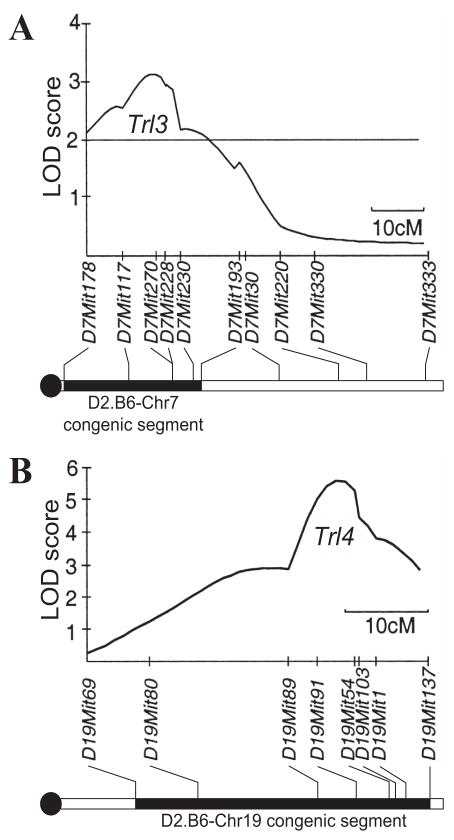

Inbred, pathogen free, C57BL/6J (B6) and DBA/2J (D2) male mice were purchased from the Trudeau Institute Animal Breeding Facility. Mice were free of common viral pathogens as determined by routine testing performed by the Research Animal Diagnostic and Investigative Laboratory, University of Missouri (Columbia, MO, USA). Trl3 (Chromosome 7; Chr.7) and Trl4 (Chromosome 19; Chr.19) congenic mouse strains were generated using a speed-congenic (marker-assisted) approach (22). In this protocol, successive F1 backcross males were genotyped to identify individuals with the least residual donor genomic DNA, and were selected for further backcrossing. In these mice, the Chr.7 (Trl3) or Chr.19 (Trl4) segments from B6 strain was introgressed onto the genetic background of the D2 strain. For Trl3, the BXD19 recombinant inbred strain was used as the initial donor for the proximal portion of Chr.7 (D7Mit178-D7Mit193) (Fig. 1A), while for Trl4 the BXD9 strain was the initial donor of the distal portion of Chr.19 (D19Mit69-D19Mit137) (Fig. 1B). Once at the N4 generation, heterozygotes were intercrossed to generate the homozygote congenic lines and also to produce the double congenic line. Genotyping was carried out as previously described (20), using tail genomic DNA and sequence-specific oligonucleotide primers listed in Table S1. All experimental procedures involving mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Trudeau Institute.

Figure 1. Physical position of the Chr.7 (Trl3) and Chr.19 (Trl4) segments from C57BL/6J strain introgressed onto the genetic background of the DBA/2J strain.

The locations of the DBA/2 (D2, empty) and C57BL/6J (B6, solid lines) segments introgressed in D2.B6-Chr7 (A) and D2.B6-Chr19 (B) are shown, as delimited by markers D7Mit178-D7Mit193 for Chr.7 and D19Mit69-D19Mit137 for Chr.19. The schematic representation of the recombinant chromosomes are positioned immediately below the LOD score traces defining the Trl3 and Trl4 loci as previously mapped by whole genome scanning in informative (B6 X D2) F2 mice (see reference (21)). The positions of informative markers, and the length of chromosomes are given in cM, and are drawn to scale.

Infection with M. tuberculosis

M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv was obtained from the Trudeau Mycobacterial Culture Collection as a frozen (−70°C) log phase stock dispersed in Proskauer and Beck medium (Difco) containing 0.01% Tween 80. For each experiment, a vial was thawed, subjected to 5-s ultrasound to break up aggregates, and diluted appropriately in PBS containing 0.01% Tween 80. Mice, 8 to 10 weeks of age, were inoculated with 102 colony-forming units (CFUs) by the aerosol route in a Middlebrook airborne infection apparatus (Tri Instruments, Jamaica, NY). Bacilli were enumerated in the lungs of infected mice at 30 and 70 days of infection by preparing lung homogenates in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 80 and by plating 10-fold serial dilutions of the homogenates on Middlebrook 7H11 enriched agar (Difco). CFU counts were performed after 3–4 weeks of incubation at 37°C, and the data are presented as log10 of total CFU count per lung.

Enumeration of CD4 T cell by Flow cytometry and Elispot

Mice were euthanized, and their lungs were perfused with PBS containing 10 U/ml of heparin to remove intravascular leukocytes. The lungs were then perfused with an enzyme cocktail consisting of 150 U/ml of collagenase, 0.2 U/ml of elastase (Roche Applied Science) and 1 mg/ml of DNase (Sigma) in RPMI. The lungs were removed, diced into small fragments, subjected to further enzyme digestion before being mechanically disrupted to form a single cell suspension (23). Total lung cells were suspended in RPMI-FCS in two 5 ml tubes at 1 × 107/ml, and incubated with Brefeldin A (10μg/ml, 5 h at 37°C; Epicenter Technologies). They were then stained for flow cytometry with FITC-anti-CD3, R-phycoerythrin-anti-CD4, and Peridinin chlorophyll protein-anti-CD8 mAbs. After fixation overnight in 0.5% paraformaldehyde they were stained for intracellular IFN-γ with allophycocyanin-anti-IFN-γ mAb, as described previously (23), and analyzed by FACS (Calibur flow cytometer; BD Biosciences) using Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences).

Changes in the total number of Ag-specific T cells in the lungs capable of making IFN-γ in response to M. tuberculosis antigens were determined using the Elispot assay (Mouse IFN-γ ELISPOT Set, BD Biosciences), according to the manufacturer’s instructions and using total lung cells from a pool of 4 mice (23, 24). The M. tuberculosis antigen preparation used to stimulate IFN-γ production was a sonicated extract of a M. tuberculosis culture (23) and an ESAT-6 (1-20) peptide (25) (New England Peptide, Fitchburg, MA) which is an early-secreted M. tuberculosis protein.

Immunocytochemistry

Lungs were fixed by an intra-tracheal infusion of 10% formalin followed by 24 hr immersion (at 20°C) in the same fixative. The lungs were then dehydrated in serial baths of 70 and 100% ethanol, embedded in paraffin and sectioned. Immunocytochemistry to detect the NOS2 (nitric oxide synthase 2) enzyme, and staining for acid-fast bacteria were performed as previously described (26). Briefly, lung sections were incubated with a) affinity-purified rabbit anti-mouse NOS2 Ig (primary antibody), b) biotinylated goat anti-rabbit Ig (secondary antibody), and c) avidin-coupled biotinylated horse radish peroxidase with diaminobenzidine as the substrate. Sections were then stained for acid-fast bacilli (27) and counterstained with methylene blue. Photomicrography was performed with a Nikon Microphot-Fx microscope fitted with a Spot RT Slider camera (Diagnostic Instruments Inc.) using Spot RT Software for image acquisition.

Transcriptional profiling with microarrays

Total lung RNA (three samples per experimental group; 36 in total) from uninfected controls and M. tuberculosis-infected (for 30 and 70 days) B6, and D2 controls as well as the Chr.7 and Chr.19 congenics (D2.B6-Chr7 and D2.B6-Chr19, respectively) were used for transcriptional profiling with Affymetrix oligonucleotides chips (Mouse Genome 430 2.0 array), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. To minimize technical variability, RNA processing steps (RNA extraction, probe labeling and microarray hybridization) were executed in parallel for all samples. The GeneSifter™ microarray data analysis system (VizX Labs, Seattle, WA, USA; www.genesifter.net) was used to analyze data generated from comparisons between control (uninfected) and M. tuberculosis-infected (day 30 and 70) groups for B6, D2, D2.B6-Chr7 and D2.B6-Chr19 mice individually. Data were normalized by the robust multi-array average (RMA) algorithm, and differential expression was tested by using either pairwise, or two-way ANOVA analysis with independent t-tests. Complete microarray data (accession no. E-MEXP-1942) has been deposited in the ArrayExpress database (www.ebi.ac.uk/microarray-as/ae/).

RESULTS

Construction of mouse lines congenic for the TB-resistance loci Trl3 and Trl4

Host resistance loci Trl3 and Trl4 were selected for investigation for the following reasons: a) Trl3 affects both pulmonary bacterial replication and host survival time following M. tuberculosis infection in independent genome scans of [B6 X D2] F2 mice (20, 21), b) Trl4 shows the strongest genetic effect in these mice (21), and c) there is strong additive interactions between Trl3 and Trl4 that explains a large fraction of the phenotypic variance in [B6 X D2] F2 mice (21). To study the independent contribution of Trl3 and Trl4 to the differential susceptibility phenotype of B6 vs. D2, and to initiate the identification of the cellular and biochemical pathways underlying both genetic effects, we have used a marker-assisted strategy to construct congenic lines in which the Chr.7 (Trl3) and Chr.19 (Trl4) segments of B6 resistant background were independently introgressed onto the D2 susceptible background. For Chr.7, the proximal segment delineated by markers D7Mit178 to D7Mit193 (Fig. 1A) was transferred to create D2.B6-Chr7, while for Chr.19 the distal chromosomal segment delineated by markers D19Mit69 to D19Mit137 was transferred to create D2.B6.Chr19 (Fig. 1B). To increase the efficiency of the breeding process, B6 chromosomal segments to be introgressed onto D2 were donated by independent BXD recombinant congenic strains (that already contain a 50:50 ratio of B6 vs. D2 genome) BXD9 (Trl4) and BXD19 (Trl3). Heterozygotes produced by serial backcrossing were then intercrossed to generate homozygotes at each locus. Independent Trl3 and Trl4 congenic lines were then intercrossed to generate the Trl3:Trl4 double congenic line.

Effect of chromosomes 7 and 19 on susceptibility to pulmonary infection with M. tuberculosis

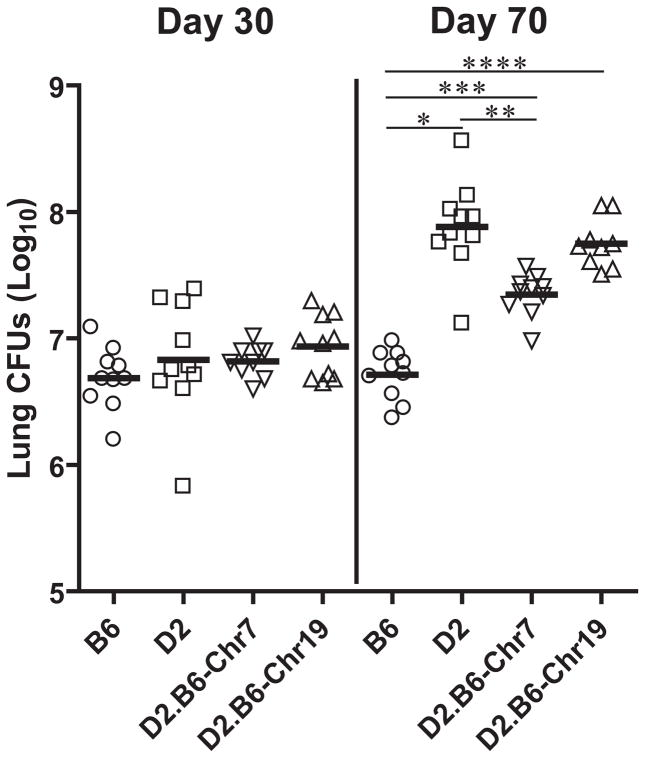

To evaluate the effect of the transferred Chr.7 (Trl3) and Chr.19 (Trl4) B6 segments on the susceptibility of D2 mice to infection with M. tubertculosis, D2.B6-Chr7 and D2.B6-Chr19 singly congenic lines together with C57BL/6 (B6) and DBA/2 (D2) controls were infected with 102 CFUs of virulent M. tuberculosis H37Rv by the aerosol route, and at day 30 and day 70 post-infection, pulmonary bacterial load was determined. Similar bacterial loads were measured in the lungs of the 4 mouse strains (Fig. 2) at day 30, a time point of the infection where the innate difference between B6 and D2 in TB susceptibility is not yet detectable. In the subsequent genetically controlled phase of infection (day 70), increased pulmonary replication of M. tuberculosis had occurred in D2 mice, resulting in a 16 fold increase in CFU from day 30 to day 70. By contrast, the infection was held stationary in lungs of B6 mice over the same period (Fig. 2), in agreement with previous reports (21). In these experiments, the D2.B6-Chr19 line showed microbial pulmonary loads (day 30 and day 70) very similar to those of D2 mice, while a significant 7–8 fold reduction in lung CFUs was measured in D2.B6-Chr7 mice compared to D2 controls (Fig. 2). D2 mice doubly congenics for the B6-derived Chrs. 7 and 19 segments were also tested in the same setting, and showed CFU counts at day 70 that were undistinguishable from those seen in D2.B6-Chr7 mice (data not shown). Therefore, although transfer of the B6-derived Trl3 containing Chr.7 segment significantly reduces pulmonary replication of M. tuberculosis in otherwise-permissive D2 mice, transfer of Chr.19 (Trl4) does not enhance resistance by itself and does not improve on the protective effect of Chr.7.

Figure 2. Replication of M. tuberculosis in the lungs of B6, D2, and D2.B6-Chr7 and D2.B6-Chr19 congenic mouse lines.

Resistant B6 and susceptible D2 mice, as well as D2.B6-Chr7 and D2.B6-Chr19 congenic lines were infected via the aerosol route with 102 M. tuberculosis H37Rv, and the number of M. tuberculosis bacilli were enumerated in the lungs (log10 CFU) 30 days and 70 days post-infection. CFU counts for individual mice are shown with means for each group (horizontal line). Asterisks indicate that differences in CFU counts detected between B6 and D2 (*), D2 and D2.B6-Chr7 (**), B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 (***), and B6 and D2.B6-Chr19 (****) are statistically significant (P<0.05, unpaired Student’s t test).

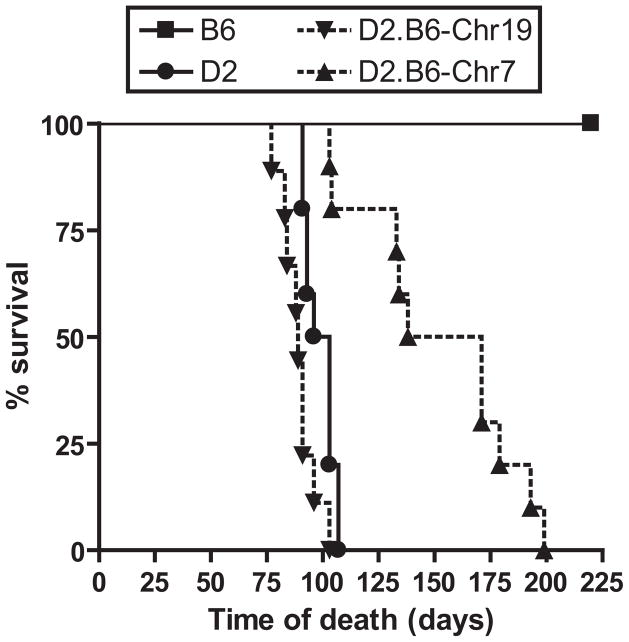

The effect of the transferred Chrs. 7 and 19 B6-derived segments on host survival from M. tuberculosis infection was next determined (Fig. 3). Following aerosol infection, susceptible D2 mice showed a mean survival time (MST) of ~100 days, with all animals succumbing to infection by day 107. On the other hand, resistant B6 mice all survived beyond the 220 days observation period. The MST of the D2.B6-Chr19 line was 89 days, a value similar to that of D2 controls. On the other hand, D2.B6-Chr7 mice displayed a significant increase in survival time over D2, revealing a MST of 155 days with animals surviving up to day 199. Therefore, the protective effect of B6-derived Chr.7 (Trl3) initially detected by the reduction in pulmonary microbial replication caused an increase in host survival time. These two phenotypes are also known to be influenced by Trl3 in informative [B6 X D2] F2 mice (20, 21). On the other hand, the protective effect of B6 alleles at Trl4 noted in the same [B6 X D2] F2 mice (21) is lost upon transfer of Chr.19 onto the D2 background.

Figure 3. Survival of B6, D2, and D2.B6-Chr7 and D2.B6-Chr19 congenic mouse lines following aerosol infection with M. tuberculosis.

B6, D2, D2.B6-Chr7 and D2.B6-Chr19 mice were infected via the aerosol route with 102 M. tuberculosis H37Rv, and survival to infection was monitored during 220 days.

Effect of Trl3 and Trl4 on T cell-mediated immune response in M. tuberculosis infected lungs

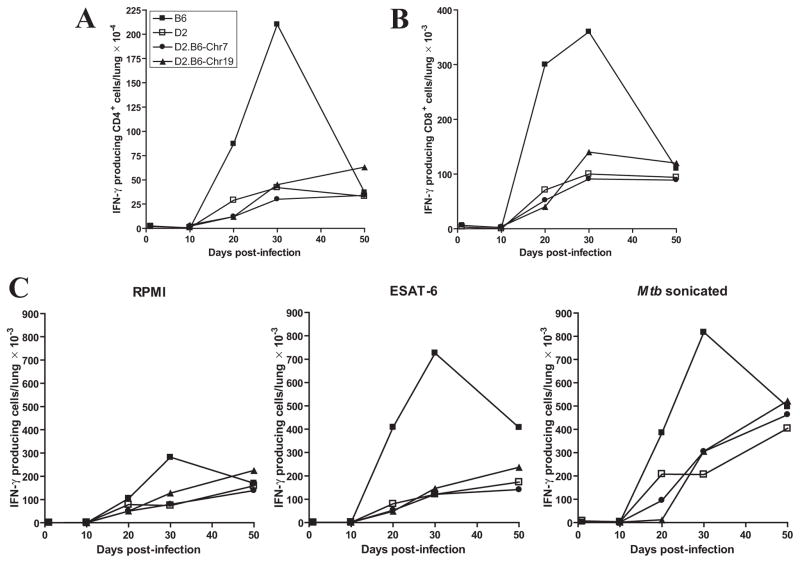

To initiate studies on the mechanistic basis of increased resistance noted in the D2.B6-Chr.7 congenics (Trl3), we investigated the effect of this locus on the type and extent of Th1 response during M. tuberculosis infection. In these studies, B6 and D2 control mice together with D2.B6-Chr7 and D2.B6-Chr19 congenics were infected with M. tuberculosis and the number of IFN-γ producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were enumerated in the lungs, 10, 20, 30 and 50 days following aerosol infection (Fig. 4). In B6 resistant controls, there was a very robust accumulation of IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4A) and to a lower extent CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4B). This T cells influx started at day 20, and peaked at day 30, a time point at which B6 mice start to restrict pulmonary bacterial replication. This cellular response subsided by day 50 in B6 mice. By contrast, no such rapid T-cell influx of IFN-γ producing T cells was seen in susceptible D2 controls. Rather, there was a slow accumulation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in D2 infected lungs that peaked at day 50 and with numbers four times lower than peak numbers observed in control B6 at day 30 post-infection. On the other hand, the D2.B6-Chr7 congenic mice displayed kinetics of IFN-γ+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells accumulation in the lung that were indistinguishable from those seen in D2 susceptible controls (Fig. 4, A and B). As expected, D2.B6-Chr19 congenics showed T cells recruitment kinetics similar to D2 controls.

Figure 4. Kinetics of T cell response in the lungs of M. tuberculosis-infected B6, D2, and D2.B6-Chr7 and D2.B6-Chr19 congenic mouse lines.

The different control and congenic lines were infected with 102 M. tuberculosis H37Rv by the aerosol route and the number of IFN-γ–producing CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (B) T cells were enumerated in the lungs at 10, 20, 30 and 50 days post-infection. In parallel, the appearance of antigen-specific, IFN-γ-secreting T cells in the lungs (total cells) was evaluated by Elispot assay (C), using either an ESAT-6 peptide or crude M. tuberculosis sonicate as antigenic stimuli, and RPMI culture medium as unstimulated control. Results are from pooled lung cells obtained from 4 mice per experimental group. Individual experimental points are representative of measurements performed in triplicate.

The effect of Trl3 on the production of antigen specific IFN-γ secreting T cells in the lung was also investigated by Elispot assay, using either a crude M. tuberculosis sonicate or an ESAT-6 (1-20) peptide (a major M. tuberculosis antigen) as antigenic stimuli (Fig. 4C). In agreement with results reported in Figs. 4A and 4B for the number of IFN-γ+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the lungs of infected mice, there was a robust response to both ESAT-6 and M. tuberculosis sonicate in the lungs of control B6 mice that peaked at day 30 and diminished by day 50. On the other hand, susceptible D2 controls lacked the day 30 peak, but instead showed a more progressive response which peaked at day 50, the last time point investigated. The response of D2 mice to the M. tuberculosis sonicate was most robust (compared to ESAT-6), and at day 50 the number of IFN-γ secreting T cells in response to the sonicated extract were similar to that measured in B6 (Fig. 4C). Again, the number of antigen-specific IFN-γ secreting T cells detected in both Chr.7 and Chr.19 congenic lines was similar to that detected in the D2 controls. Together these results suggest that transfer of B6-derived Trl3 alleles in D2.B6-Chr7 congenics increases resistance to pulmonary TB by a mechanism that is unlinked to the ability of B6 mice to rapidly recruit IFN-γ+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to the lung.

Effect of Trl3 on histopathology of M. tuberculosis infected lungs

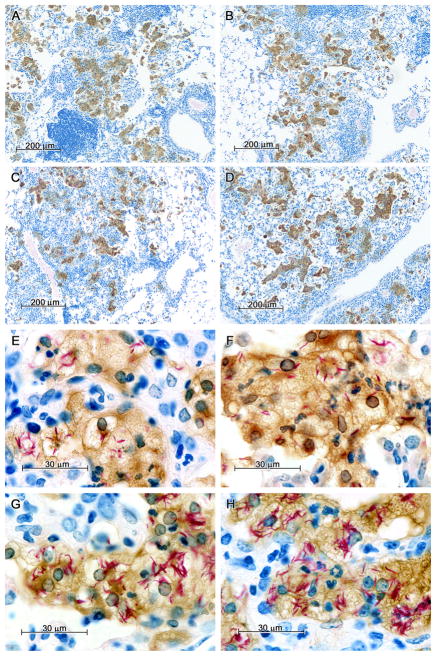

The lung histopathology of D2 and B6 mice following aerosol challenge with M. tuberculosis [at the time D2 mice begin to succumb from infection (day 90 post-infection)] has been described previously (28). In the present study, lung lesions observed at day 70 post-infection in parental and congenic strains were similar in size, number and cellular composition (Fig. 5, A–D), although in some cases the alveoli in lesions of D2 and D2.B6-Chr19 mice were beginning to show presence of neutrophils. The striking difference between the lesions of susceptible and resistant mice, however, was in the level of infection of individual macrophages (Fig. 5, E–H), with those in the lesions of D2 (Fig. 5H) and D2.B6-Chr19 (Fig. 5G) mice containing much larger numbers of acid fast bacilli. This suggests that the higher pulmonary load of M. tuberculosis detected in D2 and D2.B6-Chr19 mice may be explained by a much higher level of intracellular replication in individual macrophage, as opposed to a larger number of infected macrophages.

Figure 5. Lung histopathology of M. tuberculosis-infected mice at day 70 of infection.

B6 and D2 control mice together with the D2.B6-Chr7 and the D2.B6-Chr19 congenic lines were infected by the aerosol route with 102 CFUs of M. tuberculosis, and 70 days later lungs were harvested, and processed for immunocytochemistry as described in Materials and Methods. Briefly, tissue sections were stained for acid-fast bacilli (red), while nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) was detected by immunocytochemistry; sections were counterstained with methylene blue. In lung lesions of B6, D2.B6-Chr7, D2.B6-Chr19 and D2 mice, acid fast bacilli were confined to large foamy macrophages that stained positively for NOS2. Macrophages of D2 and D2.B6-Chr19 mice contained many more acid fast bacilli than macrophages of B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 mice. (A) Low power (50X) of B6 lungs; (B) Low power (50X) of D2.B6-Chr7 lungs; (C) Low power (50X) of D2.B6-Chr19 lungs; (D) Low power (50X) of D2 lungs; (E) High power (667X) of B6 lungs; (F) High power (667X) of D2.B6-Chr7 lungs; (G) High power (667X) of D2.B6-Chr19 lungs; (H) High power (667X) of D2 lungs.

Since expression of the bactericidal enzyme nitric oxide synthase 2 (Nos2) is a good indicator of IFN-γ-triggered macrophage activation, Nos2 protein expression was also evaluated in these M. tuberculosis-infected lungs by immunocytochemistry at day 70 post-infection (Fig. 5). Despite important inter-strain differences in pulmonary bacterial loads measured at day 70, comparable levels of Nos2 staining was seen in macrophages of B6, D2, and the two congenic strains, (Fig. 5). Additional transcriptional profiling studies also showed similar levels of IFN-γ and Nos2 mRNA expression in lungs from all strains following 30 (Fig. S1A) and 70 (Fig. S1B) days of M. tuberculosis infection. This suggests that neither the B6 vs. D2 inter-strain difference in susceptibility to M. tuberculosis, nor the enhanced resistance associated with transfer of B6 alleles at Trl3 in D2.B6-Chr7 congenics are linked to differences in activation of the nitric oxide-based anti-M. tuberculosis defense.

Effect of Trl3 on transcript profiles in the lungs of M. tuberculosis infected mice

To gain insight into the host cell types, cellular and molecular pathways possibly involved in the differential permissiveness to pulmonary replication of M. tuberculosis, we carried out transcript profiling studies on M. tuberculosis-infected lungs from congenic and parental strains. We were particularly interested in identifying groups of transcripts associated with increased resistance to M. tuberculosis infection of B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 mice. That list consists in the overlap between the lists commonly expressed in response to infection between resistant B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 but that show a significant difference in modulation when compared to infected susceptible D2.

In these experiments, B6, D2 as well as the D2.B6-Chr19, and D2.B6-Chr7 congenic lines were infected with M. tuberculosis and lungs were harvested at day 30 and day 70, and RNA was prepared. Three independent RNA samples from each group were converted to labeled cDNAs and hybridized to Affymetrix oligonucleotides arrays (Mouse Genome 430 2.0 array). Hybridization results were analyzed with the Genesifter analysis program to characterize changes in gene expression. The quality of the hybridization data for all the arrays was evaluated by examining gene expression intensity distribution (box plots) following RMA normalization (Fig. S2A). All experimental groups revealed a similar median expression value and a similar distribution of gene expression intensities, indicating homogeneity of the data set. A similar analysis of the three replicates for individual experimental group also showed homogeneity of the data within each group, with no outliers (data not shown).

In a first set of analyses, gene expression data obtained at day 30 and day 70 post-infection were compared to that of day 0 (day 30 vs. day 0; day 70 vs. day 0) for each strain to establish M. tuberculosis-induced strain-specific ratios (pairwise analysis). These ratios were then used to determine gene expression profiles similarities in all mouse strains. Statistical analysis (t test p value <0.01; fold change ≥2X) revealed that infection with M. tuberculosis had a dramatic and potent effect on the profile of gene expression of all mouse strains. Inter-strain comparison revealed that 1232 and 1876 genes were commonly regulated in all mouse strains in response to M. tuberculosis infection and this at day 30 and 70, respectively. Of those, a total of 1136 transcripts were modulated in response to infection at both time points and in all mouse strains (Fig. S2B). Additional analysis of the top 100 genes showing the greatest degree of M. tuberculosis-induced modulation, showed that 30 genes (of these 100) were commonly regulated in all mouse strains at both time points (Table S2). This gene list represents a fingerprint of the anti-TB transcriptional response following aerosol infection and includes genes such as IFN-γ, Stat1, Irg1, Iigp1 as well as chemokine ligands Cxcl9, Cxcl10, Ccl8 and chemokine receptor Cxcr6. On the other hand, 7 and 6 transcripts were specifically modulated for the day 30 and 70 time points, respectively, revealing potential stage specific aspects of host response to pulmonary TB (Table S2).

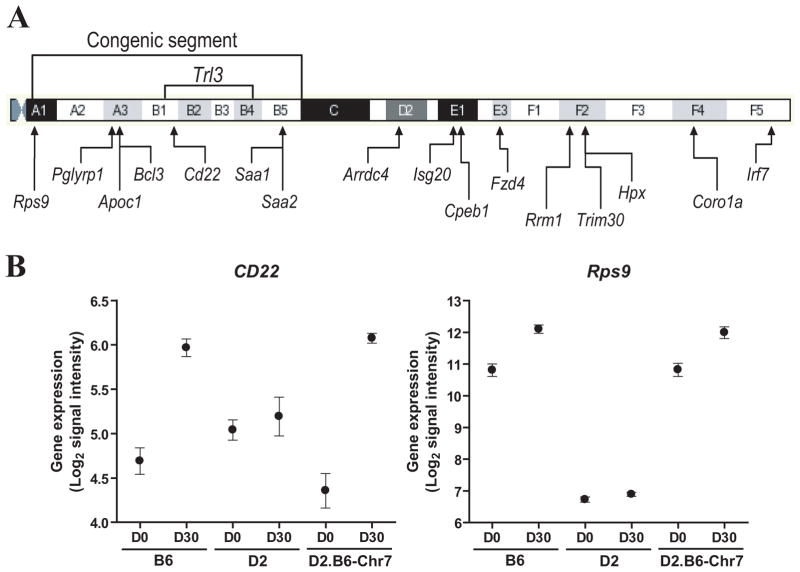

In a second stage, transcript profiles associated with differential susceptibility to M. tuberculosis in resistant B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 lines vs. susceptible D2 mice [(B6 vs D2) and (D2.B6-Chr7 vs D2)] were investigated using a two-way ANOVA analysis of the day 30 data set. We focused our analysis on day 30 since it is at this time point that resistant B6 mice start to restrict pulmonary bacterial replication, and hence are likely to express genes contributing to protection. Likewise, B6, D2 and D2.B6-Chr7 show similar pulmonary microbial loads at day 30 (as opposed to day 70; Fig. 2) thereby minimizing the effect of bacterial burden on identification of quantitative differences in expression associated with resistance to infection. Gene lists were generated by comparing M. tuberculosis-induced changes in transcript profiles (expression at day 30 post-infection vs. day 0) in both resistant strains vs. susceptible strain (either B6 or D2.B6-Chr7 compared to D2). The comparison of B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 to susceptible D2 mice revealed a total of 1109 and 1611 genes showing statistically significant differences in regulation in response to infection (t test p value <0.05; fold change ≥2X), respectively, including a subset of 284 genes commonly regulated between B6 and D2.B6-Chr7. We have selected a subset of 12 such transcripts for validation by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. S3). These experiments showed a validation success rate of ~60%. Most non-validated transcripts gave poor amplification results and were expressed at very low levels in lungs of all mouse strains tested. A gene ontology report on these 284 (221 annotated) genes, revealed that 42 (19% of annotated genes) of them were associated with the immune system, representing the most abundant group of genes. By removing genes in duplicate and genes where the expression ratios in D2.B6-Chr7 congenics did not follow the expression kinetic observed in B6 when compared to D2, 32 genes (Irf7, Pglyrp1, Bcl3, Cd22, and Coro1a are located on Chr.7) were identified (Table 1). A few chemokine ligand genes are present in this list, including Cxcl5, which differential expression in B6 and D2 mice has been previously reported (29). Moreover, 16 of the 221 annotated genes commonly regulated in B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 mice map to Chr.7 (Table 2), including 7 (Rps9, Pglyrp1, Apoc1, Bcl3, Cd22, Saa1 and Saa2) that are located within the boundaries of the Chr.7 congenic segment introgressed in D2.B6-Chr7 and that contain the Trl3 locus. These genes constitute strong positional candidates for Trl3, including the B-cell specific regulatory gene Cd22 that maps directly under the Trl3 linkage peak (Fig. 6A). The intrinsic and inducible expression profiles for the 7 genes were quantitatively similar in B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 when compared to D2 mice. More precisely, gene expression in B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 was similarly higher (Rps9, Pglyrp1, and Cd22) or lower (Apoc1, Bcl3, Saa1 and Saa2) than in D2 mice. A representative example is the case of Cd22 and Rps9, where there was robust induction expression of these genes in response to M. tuberculosis in B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 mice at day 30, while susceptible D2 mice did not show induction of expression of these two transcripts (Fig. 6B), even 70 days post-infection (data not shown). Therefore, the dramatic expression of Cd22 in response to M. tuberculosis infection in the lungs of resistant strains compared to susceptible D2 represents a candidate expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) for Trl3.

Table 1.

Genes differentially regulated in common in B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 when compared to D2 at day 30, and that are associated with the immune system process

| Gene expression ratios (Day30/Day0)

|

Gene ID | Gene Name | Chr. | LocusLink | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 | D2 | D2.B6-Chr7 | ||||

| 78.42 | 120.53 | 58.04 | Clec4e | C-type lectin domain family 4, member e | 6 | 56619 |

| 32.73 | 99.43 | 3.10 | Cxcl5 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 | 5 | 20311 |

| 21.53 | 33.79 | 23.63 | Ccl8 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 | 11 | 20307 |

| 12.89 | 94.55 | 18.62 | Cxcl11 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 | 5 | 56066 |

| 8.19 | 15.48 | 7.08 | Irf7 | Interferon regulatory factor 7 | 7 | 54123 |

| 6.76 | 13.97 | 5.23 | Mx1 | Myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 1 | 16 | 17857 |

| 6.53 | 11.12 | 6.11 | Fcgr2b | Fc receptor, IgG, low affinity IIb | 1 | 14130 |

| 6.41 | 17.59 | 9.31 | Cxcl13 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 13 | 5 | 55985 |

| 5.97 | 10.00 | 5.33 | Oasl2 | 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase-like 2 | 5 | 23962 |

| 5.90 | 18.60 | 5.51 | Il1rn | Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist | 2 | 16181 |

| 5.08 | 8.04 | 4.31 | Slc7a2 | Solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 | 8 | 11988 |

| 4.66 | 10.21 | 4.94 | Klrk1 | Killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily K, member 1 | 6 | 27007 |

| 4.46 | 7.84 | 3.85 | Dhx58 | DEXH (Asp-Glu-X-His) box polypeptide 58 | 11 | 80861 |

| 4.26 | 10.65 | 4.14 | Il1a | Interleukin 1 alpha | 2 | 16175 |

| 3.93 | 17.03 | 4.39 | Rsad2 | Radical S-adenosyl methionine domain containing 2 | 12 | 58185 |

| 3.54 | 2.30 | 3.85 | Ccr7 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 7 | 11 | 12775 |

| 3.50 | 2.45 | 4.27 | Pglyrp1 | Peptidoglycan recognition protein 1 | 7 | 21946 |

| 3.43 | 3.97 | 2.17 | Jak2 | Janus kinase 2 | 19 | 16452 |

| 3.02 | 5.24 | 4.02 | C1s | Complement component 1, s subcomponent | 6 | 50908 |

| 2.88 | 4.18 | 2.28 | Tlr7 | Toll-like receptor 7 | X | 170743 |

| 2.84 | 3.72 | 2.29 | Bcl3 | B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 3 | 7 | 12051 |

| 2.75 | 1.36 | 2.50 | Lck | Lymphocyte protein tyrosine kinase | 4 | 16818 |

| 2.42 | 1.11 | 3.29 | Cd22 | CD22 antigen | 7 | 12483 |

| 2.37 | 1.56 | 2.27 | Coro1a | Coronin, actin binding protein 1A | 7 | 12721 |

| 2.24 | 3.90 | 2.33 | Ifih1 | Interferon induced with helicase C domain 1 | 2 | 71586 |

| 1.73 | 2.48 | 1.49 | Myd88 | Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 | 9 | 17874 |

| 1.73 | 2.87 | 0.92 | Cdkn1a | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (P21) | 17 | 12575 |

| 1.70 | 2.42 | 1.92 | Jak3 | Janus kinase 3 | 8 | 16453 |

| 1.49 | 2.10 | 1.44 | Rab27a | RAB27A, member RAS oncogene family | 9 | 11891 |

| 1.43 | 4.33 | 2.77 | H2-K1 | Histocompatibility 2, K1, K region | 17 | 14972 |

| 1.26 | 2.30 | 1.24 | Mx2 | Myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 2 | 16 | 17858 |

| 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.75 | Foxp1 | Forkhead box P1 | 6 | 108655 |

Table 2.

Chromosome 7 genes differentially regulated in common in B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 when compared to D2 at day 30

| Gene expression ratios (Day30/Day0)

|

Gene ID | Gene Name | LocusLink | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 | D2 | D2.B6-Chr7 | |||

| 8.19 | 15.48 | 7.08 | Irf7 | Interferon regulatory factor 7 | 54123 |

| 3.50 | 2.45 | 4.27 | Pglyrp1a | Peptidoglycan recognition protein 1 | 21946 |

| 2.98 | 2.16 | 1.53 | Rrm1 | Ribonucleotide reductase M1 | 20133 |

| 2.84 | 3.72 | 2.29 | Bcl3a | B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 3 | 12051 |

| 2.81 | 5.61 | 3.64 | Trim30 | Tripartite motif protein 30 | 20128 |

| 2.45 | 1.12 | 2.26 | Rps9a | Ribosomal protein S9 | 76846 |

| 2.42 | 1.11 | 3.29 | Cd22a,b | CD22 antigen | 12483 |

| 2.39 | 3.71 | 2.21 | Arrdc4 | Arrestin domain containing 4 | 66412 |

| 2.37 | 1.56 | 2.27 | Coro1a | Coronin, actin binding protein 1A | 12721 |

| 2.00 | 2.80 | 1.82 | Isg20 | Interferon-stimulated protein | 57444 |

| 1.66 | 2.42 | 1.82 | Apoc1a | Apolipoprotein C-I | 11812 |

| 1.57 | 4.74 | 1.43 | Saa1a | Serum amyloid A 1 | 20208 |

| 1.32 | 4.53 | 1.35 | Saa2a | Serum amyloid A 2 | 20209 |

| 1.29 | 2.88 | 1.40 | Hpx | Hemopexin | 15458 |

| 0.79 | 0.45 | 0.72 | Cpeb1 | Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein 1 | 12877 |

| 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.59 | Fzd4 | Frizzled homolog 4 (Drosophila) | 14366 |

Gene mapping under the congenic segment and

under the Trl3 locus

Figure 6. Chromosome 7 genes differentially expressed in the lungs of B6/D2.B6-Chr7 mice compared to D2 at day 30 post-infection.

The approximate position of annotated genes on Chr.7 (Mouse Ensembl; www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus/index.html) that show differential expression in the lungs of B6/D2.B6-Chr7 mice vs. D2, 30 days (ANOVA two-by-two interaction) following aerosol infection with 102 CFUs of M. tuberculosis is shown (A). The position of cytogenetically identifiable chromosomal bands is indicated and drawn to scale. The position of the B6 Chr.7 segment (D7Mit178-D7Mit193) introgressed in D2.B6-Chr7 is shown together with the approximate boundaries of the Trl3 locus. (B) Expression levels of the CD22 and Rps9 genes measured either prior to (D0) or 30 days post-infection (D30) in the lungs of B6, D2, and D2.B6-Chr7 lines. Numerical values correspond to the mean signal intensity (Log2) obtained from three individual samples per experimental group (with standard error shown).

DISCUSSION

The complex genetic control of differential susceptibility of B6 (resistant) and D2 (susceptible) mice to pulmonary TB was investigated by genome scanning and led to the mapping of 4 quantitative trait loci (QTLs), on chromosomes 1 (Trl1), 3 (Trl2), 7 (Trl3), and 19 (Trl4) (20, 21). The Trl3 and Trl4 QTLs were selected for further study based in part on strength of genetic linkage (Trl4), and penetrance of the genetic determinant on different phenotypic measures of susceptibility (Trl3). Congenic lines were created in which the B6-derived, resistance-associated, Chr.7 (Trl3; D2.B6-Chr7) and Chr.19 (Trl4; D2.B6-Chr19) segments were independently introgressed onto susceptible D2. Phenotyping these lines for susceptibility to pulmonary TB validated the protective effect of B6-derived Chr.7 (Trl3) both on pulmonary microbial replication and host survival, while transfer of the B6-derived Trl4 region of D2.B6-Chr19 did not appreciably improve resistance of susceptible D2 mice. Furthermore, although an additive effect of homozygosity for B6-derived resistant alleles at Trl3 and Trl4 on pulmonary bacterial loads had been detected in [B6 X D2] F2 mice (21), such an additive effect was not detected in Chr.7/Chr.19 doubly congenic mice which were phenotypically indistinguishable from the D2.B6-Chr7 Trl3 congenic line. These results suggest that although the Trl3 QTL can function in an “autonomous” fashion, the Trl4 genetic effect involves additional genetic interactions with loci that remain unknown but that were not included with the transfer of Trl4 to the D2 genetic background of the D2.B6-Chr19 congenic line.

CD4+ Th1 cells with the aid of CD8+ T cells play the major role in immunity to TB (4, 30, 31). In resistant mice, an orchestrated series of innate immune pathways (including IFN-γ and IL-12 production) resulting in a Th1-dominant adaptive immune pathways are activated following phagocytosis of M. tuberculosis, and culminate in the formation of granulomas at the sites of infection. Granuloma formation is essential for restriction of bacterial replication for prevention of dissemination of the infection. Therefore, the effect of the Trl3 locus on magnitude of Th1 response was measured. After a 10-days delay, resistant B6 mice displayed robust accumulation in the lungs of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ (predominantly) and CD8+ T cells, and of T cells capable of producing IFN-γ in response to both ESAT-6 and M. tuberculosis sonicate (Elispot). The response of CD4 and CD8 T cells peaked at day 30, and was concomitant with the restriction of pulmonary bacterial replication in the lungs of these mice. On the other hand, D2 mice generated a Th1 cell response of much lower magnitude that continued until day 50 when the experiment was terminated. This suggests that a weaker response to mounting mycobacterial load may contribute importantly to the susceptibility of D2 animals. However, examination of the T cell response in D2.B6-Chr7 congenic mice showed that it was similar to that seen in D2, both with respect to kinetics of accumulation of IFN-γ-producing CD4/CD8 T cells in the lungs and total number that accumulated. These results strongly argue that the mechanism by which Trl3 improves host defense against TB does not involve major alterations in the magnitude or timing of the Th1 response as measured here.

In the murine M. tuberculosis infection model, the Th1 response leads to macrophage activation via the secretion of IFN-γ and other Th1 cytokines and, macrophages activation is evidenced by acquisition of an activation transcriptome (32) that includes induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) that enables these cells to generate nitric oxide and its metabolites that function to inhibit further bacterial growth (33). Histological examination of lung sections showed that many more acid fast bacilli were present in individual macrophages in lung lesions of susceptible D2 and D2.B6-Chr19 mice than lung lesions in B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 mice, suggesting that Trl3-mediated resistance is determined by an enhanced capacity of individual macrophages to inhibit M. tuberculosis growth. In spite of this, macrophages in susceptible mice (D2 and D2.B6-Chr19) stain as densely for NOS2 as those in the resistant B6 and intermediately resistant D2.B6-Chr7 mice. Therefore, macrophages appeared activated in all mouse strains in response to Th1 immunity, but yet varied in their ability to inhibit M. tuberculosis growth in a Trl3-dependent fashion. These results suggest that Trl3 affects the macrophage response to M. tuberculosis in a NOS2-independent fashion. These findings are reminiscent of those of Yan and coworkers (34) who studied the TB susceptibility controlled by sst1. They observed that sst1 affected neither activation of Th1 cytokine-producing T lymphocytes, nor their migration to the lungs, but controlled, instead, an inducible NO synthase-independent mechanism of innate immunity (34) linked to the ability of macrophages to undergo apoptosis in response to M. tuberculosis infection. Although both ours and Yan et al. (34) studies appear to share a parallel NOS2-independent mechanism, we failed to detect any differences in apoptosis between B6, D2, D2.B6-Chr7, and D2.B6-Chr19 mice, as evaluated by TUNEL assay on M. tuberculosis-infected lung sections (data not shown).

Infection of B6 and D2 mice with M. tuberculosis results in massive and complex changes in transcript profiles in the infected lungs. The acquisition of a subset of these transcript signatures (eQTLs) in the Trl3 congenic line, caused by the transfer of the Chr.7 segment overlapping this locus, may give clues as to the mechanisms and/or genes associated with the partial gain of resistance seen on the D2.B6-Chr7 congenic line. Such signatures (eQTLs) may be detected by pairwise comparisons of transcript profiles induced by infection in both B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 mouse lines but distinct from the parental D2 line. With the microarray platform and statistical analysis implemented in our study, we have been able to detect chromosome-specific eQTLs signatures independently transferred in either the Chr.7 or Chr.19 congenic lines. Briefly, pairwise analysis (t test p value <0.01; fold change ≥2X) comparing B6 to D2 mice at day 0 revealed 565 differentially expressed genes, including 46 (8.1%) genes on Chr.7 and 17 (3.0%) genes on Chr.19 (see Table S3). As expected from their D2 genetic background, similar comparisons of transcript profiles from uninfected lungs of D2.B6-Chr7 and D2.B6-Chr19 mice to D2 revealed lower numbers of differentially expressed genes. In D2.B6-Chr19 mice, 18 (17.3%) of the 104 regulated transcripts mapped to Chr.19, while in D2.B6-Chr7 mice, 24 (34.8%) of the 69 regulated transcripts mapped to Chr.7, representing a considerable enrichment for transcripts mapping to congenic segments introgressed in these strains (Table S3). Similar results were obtained when the analysis was conducted with RNA from infected lungs. Pairwise comparison of transcript profiles from day 30 infected lungs (D2 vs. D2.B6-Chr7 and D2 vs. D2.B6-Chr19) showed that 37.0% and 37.9% of the differentially regulated transcripts mapped to Chr.7 and Chr.19 for D2.B6-Chr7 and D2.B6-Chr19 congenics, respectively (Table S3). Of interest, 52.2% (day 0) and 53.3% (day 30) of transcripts co-regulated between B6 and D2.B6-Chr19 mapped to Chr.19, while 84.2% (day 0) and 78.6% (day 30) of those co-regulated in B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 mapped to Chr.7 (Fig. S4), again showing a dramatic enrichment for cis-regulated genes mapping to the respective congenic segment. The identity (Table S4) and physical position of the annotated Chr.7 genes showing co-regulation in B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 at day 0 (Fig. S5A) and/or day 30 (Fig. S5B) is appended in the Supplementary Materials.

Of the transcripts commonly regulated in B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 (in response to infection) when compared to D2 mice (ANOVA two-by-two interaction), several belong to the ontology class “immune system process”. Moreover, 7 of these transcripts commonly regulated in B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 map within the boundaries of the Chr.7 congenic segment transferred in D2.B6-Chr7 mice, including Cd22. Cd22 is up-regulated in response to M. tuberculosis infection at day 30 in the lungs of resistant B6 and intermediately resistant D2.B6-Chr7 but is not up-regulated in susceptible D2 (Fig. 6B). CD22 belongs to the SIGLEC family of lectins (35). CD22 functions as an inhibitory receptor for B cell receptor (BCR) signalling, and has been suggested to play a role in preventing overactivation of the immune system, acting as a molecular switch controling the fate of antigen-stimulated B cells, and whether they undergo apoptosis or proliferation (36). Although little is known about the role played by B cells in TB pathogenesis, recent studies have suggested that they may play a previously unappreciated role in local immunity (37, 38). A recent study revealed that upon aerosol infection with 100 CFU of M. tuberculosis Erdman, B cell deficient mice display increased pulmonary bacterial loads, and exacerbated immunopathology associated with elevated pulmonary recruitment of neutrophils (39), which is also the case in D2 mice following long-term exposure to the same pathogen (28). In these studies, increased susceptibility of B cell deficient mice was not linked to a diminished capacity to produce IFN-γ in the lungs (39). Additional experimentation will be required to determine whether or not CD22 and its known role in controlling B-cell hypo- or hyper-activity (40, 41) may play a role in host defense against TB in general and in the Trl3-mediated effect in particular.

Although mapping far away from the congenic segment containing the Trl3 locus, Coronin 1a (also known as TACO) is an additional excellent candidate for Trl3. It is an actin-binding protein recruited to the membrane of the maturing phagosome, including those containing mycobacteria. Its modulation has strong consequences on the maturation of bacteria-containing phagosomes in macrophages (42, 43). We believe differential expression of coronin 1a in D2 vs. B6 and D2.B6-Chr7 congenics may be caused by a trans-effect caused by gene(s) within the congenic segment. The same would apply to other differentially regulated genes mapping outside the Trl3 congenic segment on chromosome 7 (Table 2 and Fig. 6A) or mapping to other chromosomes (in Table 1). Therefore, although differential expression of coronin 1a may contribute to differential susceptibility to TB, we believe it may be an effect secondary to the primary effect which must be caused by gene(s) within the congenic segment.

Although the gene(s) responsible for the Trl3 effect remains unknown, it is interesting to note that Chr.7 has been previously detected as modifying the sst1-controlled inter-strain difference in susceptibility of C57BL/6J (resistant) and C3HeB/FeJ (hyper-susceptible) to pulmonary TB (14). In congenic lines constructed between these two strains, transfer of the sst1r or sst1s alleles on C3HeB/FeJ (C3H.B6sst1r) and B6 (B6.C3Hsst1s) genetic backgrounds, respectively, only partly confers resistance or susceptibility, suggesting that other genetic loci are responsible for the phenotype of parental strains. Such genetic modifiers were investigated by whole genome scan in [C3H.B6sst1r X B6] F2 mice infected with M. tuberculosis (105, intravenous route). Four additional loci mapping to Chrs 7 (proximal, LOD 4.8), 12 (distal, LOD 6.6), 15 (distal, LOD 4.6) and 17 (proximal, LOD 5.5) were shown to influence survival to infection. Although the relationship between Trl3 and the Chr.7 locus mapped by Yan et al (14) remains to be validated, the maximum peak of linkages defining both loci show significant overlap, suggesting that they may represent the same genetic effect acting in different strain combinations.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- eQTL

expression quantitative trait locus

- MST

mean survival time

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- QTL

quantitative trait locus

- RMA

robust multi-array average

- sst1

supersusceptibility to tuberculosis 1

- TB

tuberculosis

- Trl

tuberculosis resistance locus

Footnotes

P.G. is a James McGill Professor of Biochemistry and a Distinguished Scientist of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). J.-F.M. is supported by a fellowship from the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec. This work was supported by grant AI035237 to PG from the National Institutes of Health USA (NIAID), and grant AI069161 to RJN also from the NIAID.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.WHO. The World Health Report 2000. Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva: WHO; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Global Tuberculosis Control: Surveillance, Planning. Financing. WHO report. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortin A, Abel L, Casanova JL, Gros P. Host Genetics of Mycobacterial Diseases in Mice and Men: Forward Genetic Studies of BCG-osis and Tuberculosis. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2007;8:163–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.080706.092315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufmann SH. How can immunology contribute to the control of tuberculosis? Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:20–30. doi: 10.1038/35095558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Algood HM, Chan J, Flynn JL. Chemokines and tuberculosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:467–477. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flynn JL. Lessons from experimental Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.North RJ, Jung YJ. Immunity to tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:599–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medina E, North RJ. Evidence inconsistent with a role for the Bcg gene (Nramp1) in resistance of mice to infection with virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1045–1051. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medina E, North RJ. Resistance ranking of some common inbred mouse strains to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and relationship to major histocompatibility complex haplotype and Nramp1 genotype. Immunology. 1998;93:270–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramnik I, Dietrich WF, Demant P, Bloom BR. Genetic control of resistance to experimental infection with virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8560–8565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150227197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan H, Yan BS, Rojas M, Shebzukhov YV, Zhou H, Kobzik L, Higgins DE, Daly MJ, Bloom BR, Kramnik I. Ipr1 gene mediates innate immunity to tuberculosis. Nature. 2005;434:767–772. doi: 10.1038/nature03419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadereit S, Gewert DR, Galabru J, Hovanessian AG, Meurs EF. Molecular cloning of two new interferon-induced, highly related nuclear phosphoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24432–24441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloch DB, Nakajima A, Gulick T, Chiche JD, Orth D, de La Monte SM, Bloch KD. Sp110 localizes to the PML-Sp100 nuclear body and may function as a nuclear hormone receptor transcriptional coactivator. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6138–6146. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.16.6138-6146.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan BS, Kirby A, Shebzukhov YV, Daly MJ, Kramnik I. Genetic architecture of tuberculosis resistance in a mouse model of infection. Genes Immun. 2006;7:201–210. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tosh K, Campbell SJ, Fielding K, Sillah J, Bah B, Gustafson P, Manneh K, Lisse I, Sirugo G, Bennett S, Aaby P, McAdam KP, Bah-Sow O, Lienhardt C, Kramnik I, Hill AV. Variants in the SP110 gene are associated with genetic susceptibility to tuberculosis in West Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10364–10368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603340103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thye T, Browne EN, Chinbuah MA, Gyapong J, Osei I, Owusu-Dabo E, Niemann S, Rusch-Gerdes S, Horstmann RD, Meyer CG. No associations of human pulmonary tuberculosis with Sp110 variants. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e32. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.037960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavebratt C, Apt AS, Nikonenko BV, Schalling M, Schurr E. Severity of tuberculosis in mice is linked to distal chromosome 3 and proximal chromosome 9. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:150–155. doi: 10.1086/314843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanchez F, Radaeva TV, Nikonenko BV, Persson AS, Sengul S, Schalling M, Schurr E, Apt AS, Lavebratt C. Multigenic control of disease severity after virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2003;71:126–131. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.126-131.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majorov KB, Eruslanov EB, Rubakova EI, Kondratieva TK, Apt AS. Analysis of cellular phenotypes that mediate genetic resistance to tuberculosis using a radiation bone marrow chimera approach. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6174–6178. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.6174-6178.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitsos LM, Cardon LR, Fortin A, Ryan L, LaCourse R, North RJ, Gros P. Genetic control of susceptibility to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Genes Immun. 2000;1:467–477. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitsos LM, Cardon LR, Ryan L, LaCourse R, North RJ, Gros P. Susceptibility to tuberculosis: a locus on mouse chromosome 19 (Trl-4) regulates Mycobacterium tuberculosis replication in the lungs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6610–6615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031727100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markel P, Shu P, Ebeling C, Carlson GA, Nagle DL, Smutko JS, Moore KJ. Theoretical and empirical issues for marker-assisted breeding of congenic mouse strains. Nat Genet. 1997;17:280–284. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung YJ, Ryan L, LaCourse R, North RJ. Properties and protective value of the secondary versus primary T helper type 1 response to airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1915–1924. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogerson BJ, Jung YJ, LaCourse R, Ryan L, Enright N, North RJ. Expression levels of Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen-encoding genes versus production levels of antigen-specific T cells during stationary level lung infection in mice. Immunology. 2006;118:195–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brandt L, Oettinger T, Holm A, Andersen AB, Andersen P. Key epitopes on the ESAT-6 antigen recognized in mice during the recall of protective immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1996;157:3527–3533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mogues T, Goodrich ME, Ryan L, LaCourse R, North RJ. The relative importance of T cell subsets in immunity and immunopathology of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J Exp Med. 2001;193:271–280. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.3.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellis RC, Zabrowarny LA. Safer staining method for acid fast bacilli. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46:559–560. doi: 10.1136/jcp.46.6.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marquis JF, Nantel A, Lacourse R, Ryan L, North RJ, Gros P. Fibrotic response as a distinguishing feature of resistance and susceptibility to pulmonary infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Infect Immun. 2008;76:78–88. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00369-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller C, Hoffmann R, Lang R, Brandau S, Hermann C, Ehlers S. Genetically determined susceptibility to tuberculosis in mice causally involves accelerated and enhanced recruitment of granulocytes. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4295–4309. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00057-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boom WH. The role of T-cell subsets in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect Agents Dis. 1996;5:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flynn JL, Chan J. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:93–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehrt S, Schnappinger D, Bekiranov S, Drenkow J, Shi S, Gingeras TR, Gaasterland T, Schoolnik G, Nathan C. Reprogramming of the macrophage transcriptome in response to interferon-gamma and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: signaling roles of nitric oxide synthase-2 and phagocyte oxidase. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1123–1140. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.8.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nathan C, Shiloh MU. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in the relationship between mammalian hosts and microbial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8841–8848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan BS, Pichugin AV, Jobe O, Helming L, Eruslanov EB, Gutierrez-Pabello JA, Rojas M, Shebzukhov YV, Kobzik L, Kramnik I. Progression of pulmonary tuberculosis and efficiency of bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination are genetically controlled via a common sst1-mediated mechanism of innate immunity. J Immunol. 2007;179:6919–6932. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crocker PR, Clark EA, Filbin M, Gordon S, Jones Y, Kehrl JH, Kelm S, Le Douarin N, Powell L, Roder J, Schnaar RL, Sgroi DC, Stamenkovic K, Schauer R, Schachner M, van den Berg TK, van der Merwe PA, Watt SM, Varki A. Siglecs: a family of sialic-acid binding lectins. Glycobiology. 1998;8 doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.glycob.a018832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hokazono Y, Adachi T, Wabl M, Tada N, Amagasa T, Tsubata T. Inhibitory coreceptors activated by antigens but not by anti-Ig heavy chain antibodies install requirement of costimulation through CD40 for survival and proliferation of B cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:1835–1843. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai MC, Chakravarty S, Zhu G, Xu J, Tanaka K, Koch C, Tufariello J, Flynn J, Chan J. Characterization of the tuberculous granuloma in murine and human lungs: cellular composition and relative tissue oxygen tension. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:218–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ulrichs T, Kosmiadi GA, Trusov V, Jorg S, Pradl L, Titukhina M, Mishenko V, Gushina N, Kaufmann SH. Human tuberculous granulomas induce peripheral lymphoid follicle-like structures to orchestrate local host defence in the lung. J Pathol. 2004;204:217–228. doi: 10.1002/path.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maglione PJ, Xu J, Chan J. B cells moderate inflammatory progression and enhance bacterial containment upon pulmonary challenge with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2007;178:7222–7234. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crocker PR, Paulson JC, Varki A. Siglecs and their roles in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:255–266. doi: 10.1038/nri2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker JA, Smith KG. CD22: an inhibitory enigma. Immunology. 2008;123:314–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaul D, Anand PK, Verma I. Cholesterol-sensor initiates M. tuberculosis entry into human macrophages. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;258:219–222. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000012851.42642.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaul D. Coronin-1A epigenomics governs mycobacterial persistence in tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;278:10–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.