Abstract

Objective

To ascertain if levosimendan postconditioning can alleviate lung ischemia–reperfusion injury (LIRI) in rats.

Method

One hundred rats were divided into five groups: Sham (sham), ischemia–reperfusion group (I/R group), ischemic postconditioning (IPO group), levosimendan postconditioning (Levo group) and combination postconditioning group of levosimendan and 5-Hydroxydecanoic acid (Levo+5-HD group). The apoptotic index (AI) of lung tissue cells was determined using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay. Expression of active cysteine aspartate specific protease-3 ( active caspase-3), Bcl-2 and Bax in lung tissue was determined by immunohistochemical staining. The morphopathology of lung tissue was observed using light and electron microscopy.

Results

AI values and expression of active caspase-3, Bcl-2 and Bax of lung tissue in I/R and Levo+5-HD groups were significantly higher than those in the sham group ( P<0.05). AI values and expression of active caspase-3 and Bax were significantly lower, whereas that of Bcl-2 was higher significantly in the Levo group, compared with I/R and Levo+5-HD groups (P<0.05). Significant differences were not observed in comparisons between I/R and Levo+5-HD groups as well as IPO and Levo groups.

Conclusion

LIRI can be alleviated by levosimendan, which simulates an IPO protective function. A postulated lung-protective mechanism of action could involve opening of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels, relieving Ca2+ overload, upregulation of expression of Bcl-2, and downregulation of expression of active caspase-3 and Bax.

Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI) is caused by ischemia–reperfusion during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Despite improvements in CPB, ALI remains the main cause of increasing postoperative mortality and increased duration of hospitalization [1, 2]. Prevention and treatment of lung ischemia–reperfusion injury (LIRI) are important subjects in clinical and basic scientific research [2–6].

Recently, ischemic postconditioning (IPO) has been suggested to be a new method to protect organs from ischemia–reperfusion injury [7–9]. Recent studies [9, 10] have shown that one of the main protective mechanisms of IPO is to activate mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-sensitive potassium (mitoKATP) channels. Some studies have reported that specific openers of mitoKATP channels protect skeletal muscle and the liver from ischemia–reperfusion injury through alleviation of apoptosis [11, 12]. However, there are few reports focusing on the protective function of IPO in LIRI.

Levosimendan is a new positive inotropic drug. It increases the sensitivity between Ca2+ and myofilaments by combining with myocardial troponin C (cTnC) without increasing the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, i.e., [Ca2+]i, to strengthen myocardial contraction without increasing oxygen consumption in the myocardium. Simultaneously, levosimendan can open KATP channels to protect the myocardium by preventing calcium overload, stabilizing the structure of the cell membrane and mitochondrial membrane, and decreasing the production of oxygen free radicals [13–16]. Levosimendan also helps mitoKATP channels to decrease ischemia–reperfusion injury in the myocardium [15, 16]. We hypothesized that levosimendan postconditioning could have a protective role in LIRI because of apoptosis (an important factor causing lung-tissue injury during LIRI) [17]. We explored this mechanism using levosimendan postconditioning to tackle lung ischemia and observed its influence on apoptosis lung cells during LIRI in rats.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval of the study protocol

The study protocol was approved by Animal Ethics Committee of Anhui Medical University (Hefei, China). Experimental procedures were carried out under the supervision of the Ethics Committee to minimize the suffering of animals.

Establishment of the animal model

Experimental animals were provided by the Animal Laboratory Center of Anhui Medical University: 100 specific pathogen-free male rats (290–320 g). Rats were divided randomly into five groups. In the sham group, the hilum of the left lung was exposed after thoracotomy without blockage. In the ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) group, the hilum of the left lung was occluded by blocking forceps for 45 min. Then, the blocking forceps were removed to continue the blood supply and ventilation (lung vasomotor activity was set as the standard of reperfusion). Finally, rats were killed 120 min after reperfusion. In the IPO group, the hilum of the left lung was blocked for 45 min and temporary reperfusion permitted for 30 s, followed by ischemia for 30 s, for three cycles [12]. Finally, reperfusion was carried out for 120 min, and the remainder of the procedure was identical to that for the I/R group. In the Levo group, 2ml of levosimendan (0.1 µmol/kg; OrionPharma, Espoo, Finland) was administered slowly and infused for 10min via the femoral vein before blocking forceps were removed, and the remainder of the procedure was identical to that for the I/R group. In the Levo+5-HD group, 15 min before blocking forceps were removed, 5-HD (10 mg/kg; Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was administered via the femoral vein and then levosimendan (0.1 µmol/kg) given via the femoral vein before opening, and the remainder of the procedure was identical to that for the I/R group.

Anesthesia was induced with 10% chloral hydrate (0.3 mL/100 g body weight, i.p.). An animal respirator was connected to a tracheal cannula after tracheotomy to control respiratory rhythm: breathing rate, 70/min; inspiratory/expiratory time: 1:2; tidal volume: 12 ml/kg. The thoracic cavity was opened via the fifth intercostal of the left anterior chest. The fourth and fifth ribs were cut for exposure. Physiological (0.9%) saline was injected via the femoral vein to dilute heparin to 100 U/kg. Five minutes’ later, the hilum of the left lung was blocked from the left upper lung to the hilum of the lung at the end of expiration (no vasomotor was set as the standard of blockage). Simultaneously, the tidal volume was adjusted to 2/3 of its original level. After 45 min, the blocking forceps were removed, the tidal volume changed to its original level, and reperfusion carried out for 120 min.

Collection and handling of samples

Rats were killed by incision of the hilum of the left lung when the experiment was complete. Left-lung samples were placed in physiological saline on ice to clean-off blood stains and dried using filter paper. Upper-lung tissue was placed into 4% PARAformaldehyde solution for immobilization for 24 h. After immobilization, the pathological morphology of lung tissue was observed through routine embedding with paraffin wax, slicing, and hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining. Middle-lung tissue was used to determine the apoptosis index (AI) of lung tissue cells and expression of active caspase-3, Bax and Bcl-2. Lower-lung tissue (1 × 1 × 1 mm) was placed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution for immobilization. Observation was carried out with an electron microscope after slicing.

Determination of apoptosis in lung tissue cells using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

The TUNEL assay was employed with an Apoptosis Detection kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) according to manufacturer instructions. Apoptotic cells contained brown-yellow granules in the cytoplasm. The number of apoptotic cells in five high-power fields at random (×400 magnification) was calculated. The AI was expressed as the number of apoptotic cells/100 cells (%).

Determination of expression of active caspase-3, Bax and Bcl-2 proteins by immunohistochemical staining and western blotting

Paraffin wax slices were created and then dewaxed using dimethylbenzene. Ethanol hydration was carried out and rinsing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; twice every 5 min) completed. Incubation with 0.5% periodic acid was carried out for 15 min to inactivate endogenous enzymes. Rinsing with PBS twice every 5 min was completed. Microwave repairing of antigen lasted for 20 min. Rinsing with PBS thrice every 5 min was completed. Normal serum (50 μL), which was the same that used for the enzyme-labeled antibody, was added, and allowed to react at room temperature for 10 min. The liquid supernatant of tissue was extracted and 50 μL primary antibody added, followed by incubation at 4°C overnight. Rinsing with PBS thrice every 5 min was completed. Biotin-labeled secondary antibody (50 μl) was added followed by incubation at 37°C for 40 min. Rinsing with PBS thrice every 5 min was completed. 3,3’-Diaminobenzidine was added for 10 min. Rinsing with running water and counterstaining with hematin was done. Hyalinization and sealing with dimethylbenzene was then carried out. Observation under a light microscope (Motic, Richmond, BC, Canada) was focused on searching for brown-yellow granules in the cytoplasm. An Advanced 310 Image Processing system (Motic) was connected to the microscope and images taken.

Equal amounts of tissues lysates were separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The separated proteins were electrotransferred to the PVDF membrane. The membrane containing the proteins was used for immunoblotting with required antibodies. The protein bands were scanned and quantified as a ratio to β-actin control.

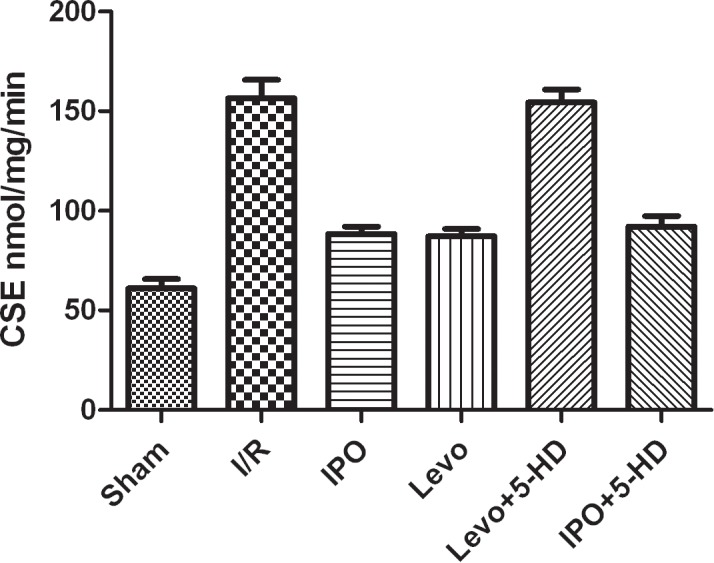

Measurement of CSE activity

The CSE activity was measured with methylene blue method. CSE can catalyze L- cysteine to produce H2S with the coenzyme pyridoxal 5 ‘- phosphate, so CSE activity can be expressed as the generation rate of H2S in unit tissue indirectly.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as ±s. One-way ANOVA was used for comparison among groups. SPSS v13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for analyses.

Results

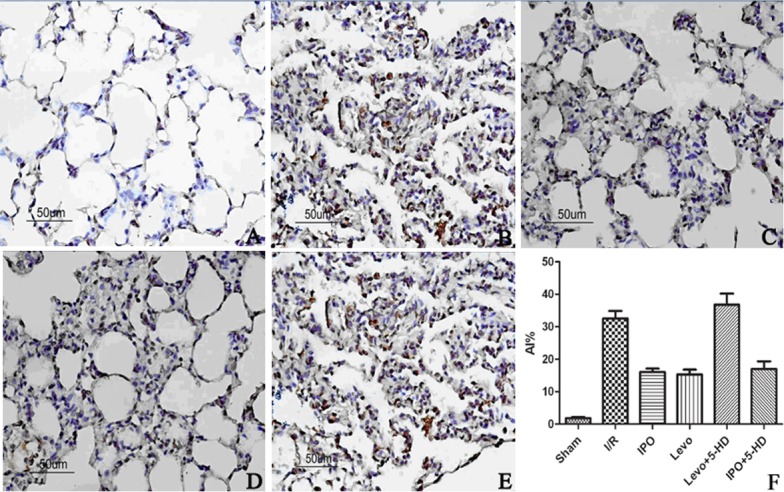

Apoptosis of lung tissue cells

Compared with the sham group, the AI in I/R and Levo+5-HD groups was significantly higher (P<0.05), but significant differences between I/R and Levo+5-HD groups were not observed. Compared with I/R and Levo+5-HD groups, the AI in IPO and Levo groups was significantly lower (P<0.05), but significant differences between IPO and Levo groups were not observed. Apoptotic cells were mainly alveolar epithelial and vascular endothelial cells (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1. TUNEL staining of apoptotic lung tissue cells in the five groups (×400 magnification).

A: Sham group; B: I/R group; C: IPO group; D: Levo group; E: Levo+5-HD group. Apoptotic cells are stained brown-yellow.

Table 1. The AI, expression of active caspase-3, Bax and Bcl-2, and comparison of the ratio between Bcl-2 and Bax in lung tissue (n = 10, ±s).

| Group | AI(%) | Active caspase-3 | Bax | Bcl-2 | Bcl-2/Bax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 1.87±0.37 | 0.44±0.04 | 0.11± 0.01 | 0.16±0.02 | 1.45±0.10 |

| I/R | 32.42±4.57* | 0.83±0.07* | 0.23± 0.02* | 0.28±0.03* | 1.20±0.16* |

| IPO | 15.43±2.32* # | 0.69±0.05* # | 0.18± 0.02* # | 0.33±0.02* # | 1.84±0.33* # |

| DE | 15.19±3.46* # | 0.65±0.04* # | 0.17± 0.03* # | 0.34±0.03* # | 1.86±0.27* # |

| DE+5-HD | 31.51±5.33* | 0.81±0.07* | 0.22± 0.03* | 0.29±0.04* | 1.22±0.15* |

Compared with Sham group: *P<0.05;

Compared with I/R group: #P<0.05

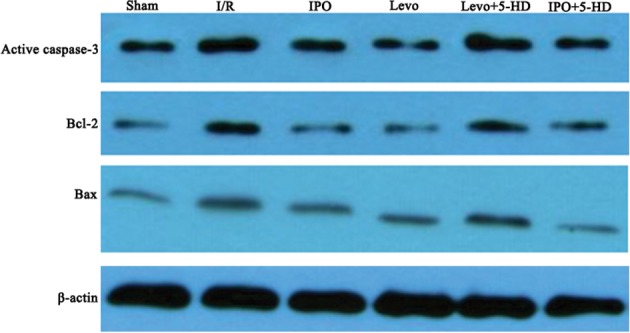

Expression of active caspase-3, Bax and Bcl-2 proteins

Compared with the sham group, expression of active caspase-3, Bax and Bcl-2 proteins in I/R and Levo+5-HD groups increased significantly (P<0.05), the ratio between expression of Bcl-2 and Bax decreased significantly (P<0.05), and there were no significant differences between I/R and Levo+5-HD groups. Compared with I/R and Levo+5-HD groups, expression of active caspase-3 and Bax proteins in IPO and Levo groups was significantly lower (P<0.05), whereas expression of Bcl-2 protein as well as the ratio between Bcl-2 and Bax were significantly higher (P<0.05), and there were no significant differences between IPO and Levo groups (Table 1). The results of Western blotting were shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Western blotting results of active caspase-3, Bax and Bcl-2 in different groups.

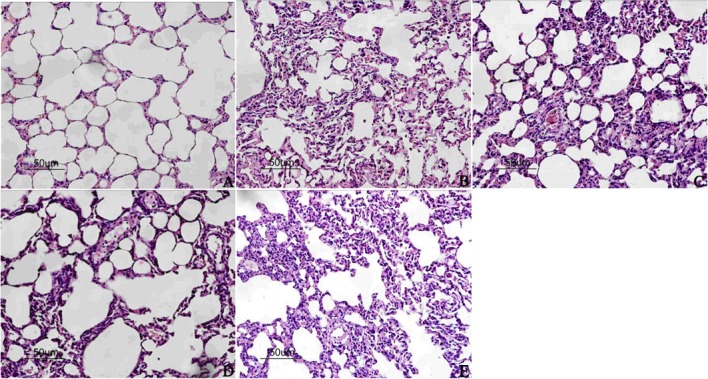

Morphology

The structure of pulmonary interstitial tissue and the alveolus in the sham group was intact and clearly visible under light microscopy without exudation into the alveolar space or infiltration of inflammatory cells. In I/R and Levo+5-HD groups, obvious pathological morphology was observed: atelectasis complicated with pulmonary emphysema; interstitial edema; infiltration of inflammatory cells; erythrocyte exudation in the alveolar space). However, in IPO and Levo groups, less interstitial edema and infiltration of inflammatory cells, as well as a significant decrease in bleeding and exudation, were noted, so the severity of tissue injury was lower than that in the I/R group (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. H&E staining of lung tissue (×200 magnification).

A: Sham group; B: I/R group; C: IPO group; D: Levo group; E: Levo+5-HD group.

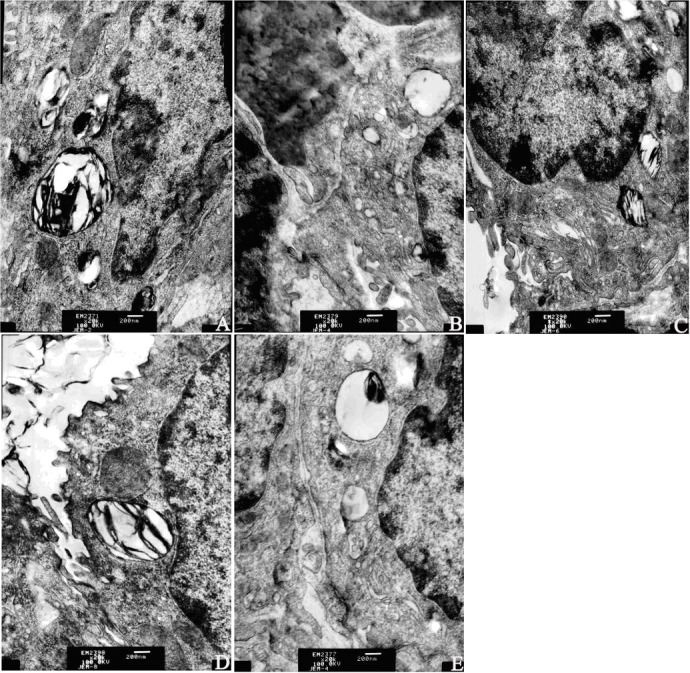

Under electron microscopy, the structure of type-II alveolar epithelial cells in the sham group was intact, and mitochondrial cristae were clear without changes in the lamellar body or loss of microvilli. The oval-shaped karyon was also visible. In I/R and Levo+5-HD groups, the mitochondria of type-II alveolar epithelial cells were swollen and increased in number. Also, the electron density of mitochondrial matrices decreased, and disordered structures of cristae, obvious evacuation of the lamellar body, and lose of microvilli were noted. Some karyons were found to be polymorphic. In IPO and Levo groups, the mitochondria of type-II alveolar epithelial cells were slightly swollen and had less disordered cristae, mild evacuation of the lamellar body and loss of microvilli also noted, and most karyons were oval (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Ultrastructure of type-II alveolar epithelial cells in lung tissue (×20,000 magnification).

A: Sham group; B: I/R group; C: IPO group; D: Levo group; E: Levo+5-HD group.

CSE activity

The results of CSE activity was shown in Fig. 5. It suggested that 5-HD blocked LEVO and did not block IPO.

Figure 5. Results of CSE activity.

Discussion

The protective function of IPO postconditioning against the injury caused by reperfusion has been confirmed in animal and humans experiments, but its clinical application is limited because of medical ethics and potential risks. Drug postconditioning is a further stage of IPO postconditioning: after ischemia, drugs are used before reperfusion (or within minutes after the beginning of reperfusion) [18] to alleviate the injury caused by reperfusion. Drug postconditioning is non-invasive and convenient.

Levosimendan is used widely to treat heart failure [19, 20]. A possible mechanism of action is enhancement of myocardial contraction by increasing the sensitivity between Ca2+ and myofilaments, leading to depletion of [Ca2+]i. Simultaneously, levosimendan can activate the KATP channels of vascular smooth muscle cells and myocardial cells and inhibit the internal flow of Ca2+. It can also meanwhile, activate sodium–calcium exchangers for external flow of Ca2+ so as to decrease [Ca2+]i, dilate vessels and relieve the preload and afterload of the heart [13–16, 21]. Furthermore, levosimendan is also an opener of the K+ channels of the plasma membrane and mitochondrial membranes. Hence, it can protect the myocardium by activating K+ channels and inhibiting mitochondrial apoptosis [22].

We observed few apoptotic cells in the sham group but more apoptotic cells in the I/R group. Obvious injury to lung tissue was observed under light and electron microscopy, which suggested that apoptosis played a part in the development of LIRI. For rats that underwent IPO and Levo postconditioning, apoptosis in lung tissue cells decreased significantly and change in the morphology of lung tissue was less significant, which suggested that IPO postconditioning can decrease the degree of LIRI. Lung protection due to Levo postconditioning was identical to that of IPO postconditioning. Interestingly, many apoptotic cells and obvious morphological injury were noted in Levo+5-HD and I/R groups. This was because 5-HD, a specific mitochondrial-sensitive K+ channel blocker, inactivated the lung-protective effect induced by Levo postconditioning. This finding demonstrated that Levo postconditioning opposes LIRI by activating the mitoKATP pathway.

Apoptosis is under the regulation of genes and also an important part of the mechanism of ischemia–reperfusion injury [17]. Bcl-2 and Bax belong to a family of Bcl-2 proteins. If Bcl-2 expression is high, homodimers or heterodimers of Bcl-2/Bcl-2 are created, and both can inhibit apoptosis. If Bax expression is high, homodimers of Bax/Bax are created, which boosts apoptosis. The change in the ratio of expression of these two factors determines if apoptosis occurs within the target location as well as the severity of apoptosis [23]. Caspases are cytokines that take part in the regulation of apoptosis, and are central actors in activation of apoptotic cascades. Active caspase-3 concentration is closely related to the rate of apoptosis [24]. We showed that expression of Bcl-2, Bax and active caspase-3 proteins in lung tissue in I/R and Levo+5-HD groups was upregulated significantly, and that the Bcl-2/Bax ratio decreased significantly. Also, expression of Bax and active caspase-3 proteins in lung tissue in IPO and Levo groups decreased significantly, whereas expression of Bcl-2 protein and the Bcl-2/Bax ratio was up-regulated significantly. These results suggested that the apoptotic mechanism of levosimendan against LIRI could include upregulation of expression of Bcl-2 protein, downregulation of expression of Bax protein, higher Bcl-2/Bax ratio, and lower dependence upon active caspase-3.

In LIRI, the main mechanism of apoptosis involves free-radical damage and Ca2+ overload. It has been confirmed that IPO postconditioning can relieve ischemia–reperfusion by opening mitoKATP channels [25]. The present study suggested that levosimendan, as a type of drug postconditioning, alleviated LIRI by activating mitoKATP channels, and that this protective effect was blocked by the specific mitoKATP channel blocker 5-HD. However, 5-HD did not block IPO. Opening mitoKATP channels depolarizes the inner membranes of mitochondria, thereby promoting internal flow of K+ and relieving Ca2+ overload within mitochondria. These actions protect the activity of mitochondrial enzymes and increase the volume of mitochondria matrices. Increasing the volume of mitochondrial matrices increases ATP synthesis and activates the mitochondrial respiratory chain to decrease production of oxygen free radicals. Activation of mitoKATP channels also inhibits release of cytochrome C from mitochondria to resist apoptosis by maintaining the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) [26].

Conclusions

Levosimendan postconditioning can protect against LIRI. This protective effect includes activation of mitoKATP channels, relief of Ca2+ overload, upregulation of the Bcl-2/Bax ratio, and reduction of active caspase-3 expression.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Gong qian, Dr Xu gonghong and Dr Lu chenghao for their technical assistance on animal model establishing and samples collecting, Dr Chang wenjiao and Dr Yu qian for experiment of molecular biology, and Dr Ruan liang for statistical analysis.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by grant number KJ2013Z108 from Anhui Provincial Natural Science Research Projects in Colleges and Universities in China. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Kim JC, Shim JK, Lee S, Yoo YC, Yang SY, et al. (2012) Effect of combined remote ischemic preconditioning and postconditioning on pulmonary function in valvularheart surgery. Chest 142(2):467–75. 10.1378/chest.11-2246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kagawa H, Morita K, Naga Hori R, Shinohara G, Kinouchi K, et al. (2010) Prevention of ischemia/reperfusion-induced pulmonary dysfunction after cardiopulmonary bypass with terminal leukocyte-depleted lung reperfusion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 139(1):174–80. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Canbaz S, Duran E, Ege T, Sunar H, Cikirikcioglu M, et al. (2003) The effects of intracoronary administration of vitamin E on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury during coronary artery surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 51(2):57–61. 10.1055/s-2003-38983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Apostolakis EE, Koletsis EN, Baikoussis NG, Siminelakis SN, Papadopoulos GS (2010) Strategies to prevent intraoperative lung injury during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Surg 5:1 10.1186/1749-8090-5-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rong J, Ye S, Liang MY, Chen GX, Chen GX, et al. (2013) Receptor for advanced glycation end products involved in lung ischemia reperfusion injury in cardiopulmonary bypass attenuated by controlled oxygen reperfusion in a canine model. ASAIO J 59(3):302–8. 10.1097/MAT.0b013e318290504e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rong J, Ye S, Wu ZK, Chen GX, Liang MY, et al. (2012) Controlled oxygen reperfusion protects the lung against early ischemia-reperfusion injury in cardiopulmonarybypasses by downregulating high mobility group box 1. Exp Lung Res 38:183–91. 10.3109/01902148.2012.662667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dezfulian C, Garrett M, Gonzalez NR (2013) Clinical application of preconditioning and postconditioning to achieve neuroprotection. Transl Stroke Res 4(1):19–24. 10.1007/s12975-012-0224-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hsiao ST, Dilley RJ, Dusting GJ, Lim SY (2014) Ischemic preconditioning for cell-based therapy and tissue engineering. Pharmacol Ther 142(2):141–53. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jin C, Wu J, Watanabe M, Okada T, Iesaki T (2012) Mitochondrial K+ channels are involved in ischemic postconditioning in rat hearts. J Physiol Sci 62(4):325–32. 10.1007/s12576-012-0206-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Robin E, Simerabet M, Hassoun SM, Adamczyk S, Tavernier B, et al. (2011) Postconditioning in focal cerebral ischemia: role of the mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channel. Brain Res February 23; 1375:137–46. 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moghtadaei M, Habibey R, Ajami M, Soleimani M, Ebrahimi SA, et al. (2012) Skeletal muscle post-conditioning by diazoxide, anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic mechanisms.Mol Biol Rep 39(12):11093–103. 10.1007/s11033-012-2015-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu Q, Tang C, Zhang YJ, Jiang Y, Li XW, et al. (2011) Diazoxide suppresses hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury after mouse liver transplantation by a BCL-2-dependent mechanism.J Surg Res 169(2):e155–66. 10.1016/j.jss.2010.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xanthos T, Bassiakou E, Koudouna E, Rokas G, Goulas S, et al. (2009) Combination pharmacotherapy in the treatment of experimental cardiac arrest. Am J Emerg 27(6):651–9. 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scheiermann P, Beiras-Fernandez A, Mutlak H, Weis F (2011) The protective effects of levosimendan on ischemia/reperfusion injury and apoptosis. Recent Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov 6(1):20–6. 10.2174/157489011794578482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Soeding PF, Crack PJ, Wright CE, Angus JA, Royse CF (2011) Levosimendan preserves the contractile responsiveness of hypoxic human myocardium via mitochondrial KATP channel and potential pERK 1/2 activation. Eur J Pharmacol 655(1–3):59–66. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yapici D, Altunkan Z, Ozeren M, Balli E, Tamer L, et al. (2008) Effects of levosimendan on myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Eur J Anaesthesiol 25:8–14. 10.1017/S0265021507002736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ng SC, Wan S, Yin AP (2005) Pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion in-jury: role of apoptosis. Eur Respir J 25(2): 356–363. 10.1183/09031936.05.00030304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oikawa M, Yaoita H, Watanabe K, Maruyama Y (2008) Attenuation of cardioprotective effect by postconditioning in coronary stenosed rat heart and its restoration by carvedilol. Circ J 72(12):2081–6. 10.1253/circj.CJ-08-0098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tasal A, Erturk M, Uyarel H, Karakurt H, Bacaksiz A, et al. (2014) Utility of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio for predicting in-hospital mortality after levosimendan infusion in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. J Cardiol 63(6):418–23. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ersoy O, Boysan E, Unal EU, Yay K, Yener U, et al. (2013) Effectiveness of prophylactic levosimendan in high-risk valve surgery patients. Cardiovasc J Afr 24(7):260–4. 10.5830/CVJA-2013-047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Soeding PF, Crack PJ, Wright CE, Angus JA, Royse CF (2011) Levosimendan preserves the contractile responsiveness of hypoxic human myocardium via mitochondrial KATP channel and potential pERK 1/2 activation. European journal of pharmacology. Eur J Pharmacol 655(1–3):59–66. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maytin M, Colucci WS (2005) Cardioprotection: a new paradigm in the management of acute heart failure syndromes. Am J Cardiol 96(6A):26G–31G. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walensky LD (2006) Bcl-2 in the crosshairs: tipping the balance of life and death. Cell Death Differ 13(8): 1339–50. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin YM, Chen YR, Lin J R, Wang WJ, Inoko A, et al. (2008) eIF3k regulates apoptosis in epithelial cells by releasing caspase 3 from keratin-containing inclusions. J Cell Sci 121(14):2382–93. 10.1242/jcs.021394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mockford K, Girn H, Vanniasinkam S (2009) Postconditioning:current controversies and clinical implications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 37(4):437–42. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mykytenko J, Reeves JG, Kin H, Wang NP, Zatta AJ, et al. (2008) Persistent beneficial effect of postconditioning against infarct size:role of mitochondrial KATP channels during reperfusion.Basic Res Cardiol 103(5):472–84. 10.1007/s00395-008-0731-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.