Abstract

Recent studies have suggested that the pineal hormone melatonin may protect against breast cancer, and the mechanisms underlying its actions are becoming clearer. Melatonin works through receptors and distinct second messenger pathways to reduce cellular proliferation and to induce cellular differentiation. In addition, independently of receptors melatonin can modulate oestrogen-dependent pathways and reduce free-radical formation, thus preventing mutation and cellular toxicity. The fact that melatonin works through a myriad of signalling cascades that are protective to cells makes this hormone a good candidate for use in the clinic for the prevention and/or treatment of cancer. This review summarises cellular mechanisms governing the action of melatonin and then considers the potential use of melatonin in breast cancer prevention and treatment, with an emphasis on improving clinical outcomes.

Melatonin is a hormone that is secreted primarily by the pineal gland in response to darkness. As such, melatonin levels rise and fall throughout the night and day, respectively. The circadian synthesis and release of melatonin is modulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus (the ‘master biological clock’) (Refs 1, 2). The functions of melatonin in the body are extensive, but its role in entraining circadian rhythms to the light–dark cycle is the most well known. People have used melatonin for many years to reset the body’s internal clock during travel and to reduce sleep-onset latency in sleep disorders.

Melatonin is a complicated hormone to study because of its chronobiotic nature and its ability to produce diverse responses in the body through both receptor-dependent and receptor-independent actions. Complicating things further is the fact that melatonin receptor density and sensitivity fluctuate throughout the 24 h cycle in both a diurnal and a circadian manner (Refs 3, 4, 5, 6). Therefore, for receptor-dependent effects, a melatonin dose given at a time when melatonin receptor expression and sensitivity are lowest may show no effect compared with this same dose given when melatonin receptor expression and sensitivity are highest, which may occur at a different time of the day.

Besides melatonin and its receptors, many other bodily functions oscillate in response to their own endogenous pacemaker and/or in response to the light–dark cycle, including gene expression (Refs 7, 8, 9). In more recent work, certain pathological states such as tumour activity have been found to be influenced by the light–dark cycle via melatonin (Ref. 10) or via the clock genes (Ref. 11).

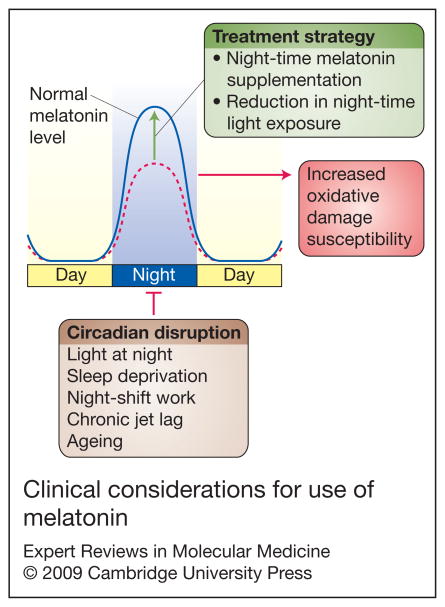

Over the past 20 years, there has been an explosion of research redefining the role of melatonin in the body, especially in the area of cancer. Melatonin ‘disruption’ by exposure to light at night has been hypothesised to play a role in breast cancer (Refs 12, 13, 14). Similar effects on the pattern and levels of melatonin production have also been observed in patients with sleep disorders, jetlag, depression, stress and immunological disorders, and it has been hypothesised that such disruption in the circadian rhythm may be associated with genomic instability and subsequent cancer susceptibility (Ref. 15). Melatonin supplementation has been successful at restoring sleep quality and circadian rhythmicity in the elderly (Refs 16, 17), suggesting that such supplementation could also ameliorate the effects of melatonin disruption, including increased cancer incidence, in younger subjects with genetic-, disease- or lifestyle-induced low levels of melatonin secretion. Melatonin may be effective as a chemopreventative agent if it inhibits the initial growth or subsequent progression of a tumour (Ref. 18).

This article does not repeat the summary of in vitro studies of melatonin as reviewed by Panzer and Viljoen (Ref. 19). Rather, this review focuses on the potential of melatonin as a chemopreventative agent or chemotherapeutic for breast cancer. In recent years, many studies have examined the mechanisms underlying the response of cells to melatonin, and many support a protective role in breast cancer. It is important to ascertain whether melatonin shows similar protection against breast cancer in the clinic, controlling for the variables that may influence melatonin’s efficacy. Thus, this review also highlights the issues or variables that one must consider when conducting melatonin research on breast cancer to assess its efficacy as a cancer-protective agent.

Implication of melatonin as an anticancer agent

Cellular and molecular actions

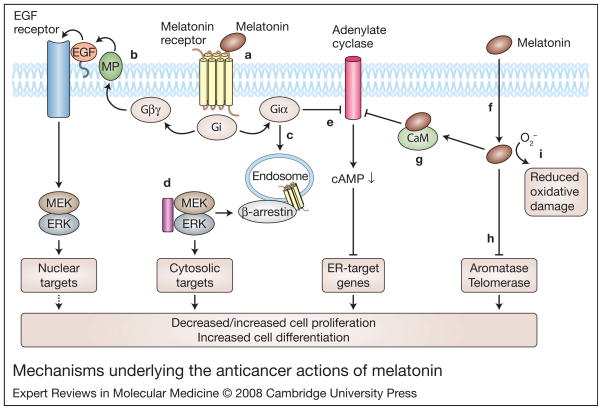

Melatonin acts to counteract tumour formation by reducing cell proliferation (Refs 20, 21, 22, 23, 24). In addition, it has antimetastatic properties in cultured MCF-7 cells (a breast-cancer-derived cell line) (Ref. 22), which may be due to a reduced chemotactic response and increased expression of cell-surface adhesion molecules (Ref. 22). Physiological levels of melatonin have been shown to reduce the invasion of MCF-7 cells, and counteract the increase in oestrogen-induced invasiveness (Ref. 25). Melatonin downregulates oestrogen (estrogen) receptor (ER) levels in breast cancer cells and blocks ER binding to DNA and transactivation functions (Refs 26, 27, 28, 29, 30). In addition, the induction of differentiation by melatonin has been demonstrated in numerous studies (Refs 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39). Highly differentiated cells have a diminished proliferative potential (Ref. 35). The myriad of intracellular mechanisms underlying the actions of melatonin are discussed in the following sections and summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mechanisms underlying the anticancer actions of melatonin.

Melatonin can act through membrane-bound G-protein-coupled receptors (MT1, MT2), or in a receptor-independent manner. (a) Melatonin binding to its cell-surface receptors can activate Gi proteins (Giαβγ) to cause dissociation into Giα-GTP and Giβγ. Increases in Giα-GTP or Giβγ can affect the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. (b) In certain cell types, Giβγ may act via matrix metalloproteinases (MPs) to liberate heparin-bound EGF to activate EGFRs in an autocrine loop (Ref. 35). Subsequent activation of the downstream effectors MEKs and ERKs may drive cell proliferation or differentiation (hence dashed arrow) through nuclear events. (c) Also, activation of Gi may result in the internalisation of melatonin receptors and binding of β-arrestin-2 (probably to phosphorylated melatonin receptors) to activate MEKs and ERKs to target cytosolic proteins leading to differentiation. (d) Microtubules (purple rectangle) can directly bind to MEK/ ERK and modulate their activity and translocation patterns in a cell. (e) Besides effects on the MAPK pathway, activated Gi leads to the inhibition of adenylate cyclase (AC) via Giα-GTP to decrease cAMP levels within the cell. Decreases in cAMP leads to decreases in the transcription of genes responsive to oestrogen receptors (ERs). Gi can also be activated directly by microtubules to increase Giα-GTP through α–β tubulin heterodimers (not shown). (f) Melatonin can also act independently of melatonin receptors to drive cellular events, as it can easily traverse membranes. (g) It can inhibit the cytosolic protein calmodulin, which, in turn, can decrease adenylate cyclases sensitive to calmodulin (types I, III and VIII). Decreases in adenylate cyclase activity reduce cAMP levels to attenuate the transcription of ER-responsive genes. (h) Melatonin can also inhibit telomerase and aromatase to reduce cellular proliferation, and (i) can scavenge free radicals, thereby reducing oxidative damage. Other abbreviations: EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (also known as MAPK1); MEK, MAPK/ ERK kinase (also known as MAP2K1).

The multiple modes of action of melatonin (antiproliferative, antimetastatic and prodifferentiation) within the cell make it an excellent candidate hormone for the prevention of cancer in those individuals at risk or for the treatment of cancer in combination with other conventional therapies.

Receptor-dependent actions of melatonin

Melatonin can act through G-protein-coupled receptors – MT1 (encoded by MTNR1A) and MT2 (encoded by MTNR1B) – located at the plasma membrane (Ref. 40). One pathway for melatonin-receptor-induced cellular differentiation may be via the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, by transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) (Ref. 35) or through the formation of β-arrestin scaffolds (Ref. 41) (Fig. 1). In addition to MAPK signalling, melatonin receptors can activate the G protein Gi, leading to inhibition of adenylate cyclase and hence the cAMP-dependent signalling pathway (Refs 42, 43, 44) (Fig. 1). Reduced cAMP leads to decreased ER binding to oestrogen-response elements of genes (Refs 27, 28, 29, 30, 40) such as cyclin D1, through its actions on JUN and ATF2 (transcription factors known to bind to minimal oestrogen-sensitive cyclin D1 promoter elements) (Ref. 45). In general, an attenuation of ER-mediated signalling in a cell should show protection against ER-positive breast cancers, similar to that occurring in response to the ER blockers tamoxifen, raloxifene and fulvestrant.

Recently, microtubules have been implicated in melatonin receptor signalling through a direct effect on Gi activation and also through receptor trafficking and sequestration of MAPK signalling components (Refs 41, 42).

Receptor-independent actions of melatonin

Melatonin can also act independently of melatonin receptors to drive cell differentiation events, reduce tumour cell proliferation and reduce invasive properties. Melatonin can easily traverse membranes, and can bind to cytosolic proteins such as calmodulin (Ref. 46), which in turn can decrease adenylate cyclases sensitive to calmodulin (AC types I, III and VIII). As indicated above, reductions in adenylate cyclase activity and cAMP levels within a cell can attenuate the transcription of ER- and AP-1-induced genes (Refs 29, 47) and thus decrease oestrogen-regulated factors (Ref. 45). The action of melatonin on such genes appears to be through ERα and not ERβ (Refs 30, 47). Besides modulating ER-responsive genes, melatonin can act to reduce oestrogen biosynthesis by decreasing the release of gonadotropins (Ref. 48) or in breast cancer cells via its inhibitory actions on aromatases (Refs 49, 50).

Melatonin also has several other cellular effects that may be protective against breast cancer. It reduces oxidative damage through its direct free-radical-scavenging properties (Ref. 51), its actions on quinone reductases (Refs 52, 53, 54), and its induction of antioxidant enzymes (Ref. 55). In addition, it modulates the immune system (Refs 56, 57, 58, 59) and is implicated in tumour surveillance (Ref. 22). Melatonin can also decrease telomerase activity in the tumours of nude mice by decreasing mRNA expression of essential telomerase subunits (Ref. 60).

Animal model studies

Multiple studies that manipulate circulating melatonin levels – through melatonin administration, changes in light–dark cycles, or pinealectomy – demonstrate that melatonin has antitumour activities. Melatonin reduces the incidence of cancer and the time of developing mammary cancer (latency) in carcinogen-induced and spontaneous mammary cancer animal models (Refs 20, 21, 22, 23, 24). Melatonin-deficient (pinealectomised) rats appear to suffer increased oxidative damage over their lifetime (Ref. 61), whereas life-long melatonin administration decreases DNA damage in the brain (Ref. 62). Long-term melatonin supplementation increases lifespan in animal model systems (mice and fruit flies) (Refs 63, 64) (although it should be borne in mind that the biology of ageing may be specific to the lifespan of each organism; Ref. 65), and reduces the spontaneous incidence of tumours in mice (Refs 63, 64) perhaps by a reduction in oxidative damage.

Light-induced effects on melatonin and breast cancer

Light exposure at night (e.g. night-shift work) may possess carcinogenic potential including that for breast cancer (Refs 14, 66, 67). Since light inhibits the synthesis and secretion of melatonin from the pineal gland (Refs 1, 2), and given the anticancer properties of melatonin discussed above, the diminished production of melatonin may explain the increase in breast cancer risk. In an elegant set of experiments, it was shown in rat hepatoma and human breast xenografts that linoleic acid uptake, tumour proliferation, cAMP levels and activity of MEKs/ERKs (downstream effectors of the MAPK pathway) are reduced when these xenografts are bathed in blood taken from human subjects at night (melatonin-rich) when compared with blood taken during the night with interrupted light exposure (low melatonin levels) (Ref. 24). Furthermore, these effects were shown to be mediated through membrane melatonin receptors.

Even though light-induced decreases in melatonin production probably play very significant roles in increasing breast cancer risk, light effects on clock genes located in the breast tissue may also be involved. Light may directly affect tumour growth through the key clock genes PER1- and PER2, which may regulate cell-cycle- and apoptosis-related genes (Refs 68, 69). PER2 inhibits the proliferation of several cancers that are epithelial in nature, including breast, prostate and lung (Ref. 69), and its expression is downregulated in several human B-ALL and lymphoma cell lines. Thus PER inactivation, perhaps via phosphorylation by casein kinase 1ε (Ref. 69) or by the methylation of PER gene promoters (Ref. 70) might induce the development of these B-cell leukaemias and lymphomas (Ref. 69) or breast cancer (Ref. 70) in humans.

Melatonin and human breast cancer

Melatonin as a biomarker of breast cancer

Risk

Biomarkers of cancer risk are usually indicative of two conditions: individuals with an inherent genetic susceptibility to a disease, and individuals who have sustained exposures associated with the initiation or promotion of the disease process. There are at least three reasons why a deficiency of melatonin could be used as a biomarker in public health screening to identify individuals who would benefit from increased surveillance and/or behavioural or chemical disease prevention strategies. First, other than the rather specific group of early-onset ‘childhood’ cancers, age is by far the most significant and biologically important risk factor in human cancer (Ref. 71); since melatonin production declines with age, constitutive or premature deficit of melatonin production could thus be indicative of a physiological ageing process that also impacts upon cancer incidence. Second, given that melatonin has been found to be a powerful antioxidant (both in vitro and in vivo) (Ref. 72) and oxidation of DNA is a known mechanism for the production of mutations that play a fundamental role in carcinogenesis (Ref. 73), lower melatonin levels could allow for a constitutive increase in radical-induced mutagenesis or render a cell hypersensitive to physiological or induced oxidative stress. Third, as indicated above, melatonin secretion can be downmodulated by sleep deprivation, nightshift work or other exposure to light at night (Ref. 74), and several types of cancer, particularly breast cancer, seem to occur at higher incidence in such populations (Ref. 75).

Several retrospective studies have demonstrated significantly reduced melatonin levels in patients with breast cancer (Refs 67, 74, 76). However, no such association was observed in a large prospective study (Ref. 77). Also, low plasma melatonin levels were not associated with breast cancer risk in high-risk individuals (Ref. 78), perhaps due to melatonin’s antioxidant properties. Circulating melatonin levels were actually increased almost two-fold in smokers relative to controls (Ref. 79), perhaps as a mechanism of detoxification.

One way to rationalise the observation of decreased melatonin production in cancer patients with no such association in high-risk patients and patients in the prospective cancer study is to hypothesise that the presence of a tumour can affect melatonin levels (Ref. 66). The regulation of the circadian rhythm of melatonin production has been reported to be affected in patients with breast, prostate, colorectal or uterine cancer, with the magnitude of the decrease in nocturnal melatonin levels correlated with the size and proliferation index of the tumour (Refs 80, 81, 82). Tumours are known to affect both local and systemic regulatory mechanisms, especially with regard to growth stimulation and immune function (Ref. 83), and this may be dependent upon tumour type (epithelial verus sarcoma) and ER status (Ref. 66). Inflammation is often associated with tumour growth (Refs 84, 85), which could stimulate the production of melatonin as an antioxidant. Therefore, size, type and grade of tumour may influence melatonin levels (increase or decrease) and, as such, caution should be used when using melatonin as a biomarker of cancer, although most studies support a role for melatonin deficiencies in increasing cancer.

Prognosis

Differences in melatonin production, particularly the magnitude of the nocturnal peak in the serum or the accumulation in breast cyst fluids (Ref. 86) in cancer patients may differentiate between different aspects of the disease, thus affecting treatment or ultimate outcome. Low levels of melatonin are associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer, based on measures of tumour aggression (proliferating cell nuclear antigen) (Ref. 81), differentiation (nuclear grade) (Ref. 87) and progression (loss of ER or progesterone receptor) (Ref. 82). Such parameters are potentially useful in staging a tumour and selecting a course of treatment, as they can provide information without the need for tumour biopsy.

Melatonin as a breast cancer chemopreventative agent

Melatonin may be effective as a chemopreventative agent if it inhibits the growth or progression of a premalignant lesion, inhibits the growth of the initial transformed cell into a palpable tumour, or inhibits the progression of the initial tumour into a more aggressive (e.g. metastatic) form (Ref. 18). Given the evidence suggesting various anticancer effects of melatonin, melatonin supplementation may thus act as a chemopreventative treatment (Ref. 88). Melatonin administration has little toxicity in vivo, so any beneficial effects come with low risk. A particular effect of melatonin that impacts on both aging and carcinogenesis is its antioxidative property (Ref. 89), which should act to reduce the mutagenesis and therefore carcinogenesis of environmental genotoxic exposures (Ref. 90). Indeed, melatonin is protective against the genotoxic effects of ionising radiation, which has been associated with almost every type of cancer (Ref. 91), as well as chemical mimics of the oxidative effects of radiation, such as those in tobacco smoke (Ref. 92). Because melatonin supplementation has been successful at restoring sleep quality and circadian rhythmicity in the elderly (Refs 16, 17), such supplementation could also ameliorate the effects of melatonin disruption (through genetics, disease or lifestyles) in younger individuals.

Melatonin as a cancer therapeutic agent

Based on its potential oncostatic effects, melatonin has also long been considered as a possible cancer chemotherapeutic agent, most often in combination with established genotoxic or immunological regimens. Human data come mainly from a large series of studies by Lissoni and colleagues (Ref. 93) that used melatonin on relatively small numbers of patients, with many different types of cancer. Based on these studies (Ref. 93), there are several grounds for invoking melatonin in cancer treatment, but most have been poorly investigated. For example, melatonin supplementation seems to promote general well-being in cancer patients (Ref. 94), which might allow them to tolerate higher doses of toxic compounds or be more likely to complete standardised regimens of such compounds. Also, melatonin seems to be effective at preventing or reducing treatment-associated hypotension (Ref. 93), thrombocytopaenia (Refs 95, 96) and cachexia (Ref. 97); however, it is not clear whether the greater tolerance for treatment elicited by melatonin administration has been exploited for greater overall treatment in any study.

In endocrine-dependent tumours, particularly breast cancer, the anti-oestrogenic effects of melatonin may interfere with hormone-induced cell proliferation, susceptibility to carcinogenesis and tumour progression (Ref. 98). Such tumour cells often overexpress hormone receptors (Ref. 99), express altered ratios of receptors (Ref. 100), overexpress receptor accessory proteins (Ref. 101) or are hormone-dependent for survival, making them hyper-responsive to modulation of exogenous hormone levels. This differentiates them from normal hormone-responsive cells and provides the basis of a therapeutic index for melatonin treatment. The need for such a therapeutic index restricts discussion of other potential mechanisms of melatonin efficacy in chemotherapy. For example, the antioxidative effect of melatonin may well protect normal cells and the entire organism from the systemic effects of chemotherapy (Ref. 102), but, since most of the in vitro work on melatonin has been performed only on cancer cells, and not concurrently on normal cells, there is no reason to believe that, in general, such protective effects will not be conferred equally on tumour cells.

Human trials of melatonin as a cancer chemotherapy agent, particularly those of Lissoni et al., have been reviewed in detail (Ref. 19). It is significant that when attempting a comprehensive review and meta-analysis of studies examining melatonin as a chemotherapeutic agent, Mills et al. (Ref. 103) were able to find only ten reports, all from the Lissoni group, that analysed melatonin definitively alone or in combination with standard therapies. All studies were performed on advanced cancer patients, were unblinded and did not include placebos. These reports included: three studies on lung cancer (one alone and two in conjunction with genotoxic chemotherapy, including cisplatin); one study each on breast cancer, renal cell cancer, glioblastoma and malignant melanoma; two studies of mixed populations of patients with either advanced or metastatic solid tumours; and one study specifically of brain metastases from assorted solid tumours. The average number of subjects in these studies was 75. The meta-analysis concludes that melatonin significantly reduced the risk of death of these patients at one year.

Expert opinion on the status of melatonin on breast cancer

Melatonin and cancer treatment

In a systematic review of randomised controlled trials of melatonin in solid-tumour cancer patients and on one-year survival, Mills et al. (Ref. 103) have shown that there is a positive benefit from the use of melatonin. These trials were all performed by the same group in the same hospital and are thus without independent confirmation from any other group; the results, although intriguing, are therefore difficult to assess. In addition, one-year survival is very short term in the context of many cancers such as breast (with a mean recurrence time of seven years) and a much longer trial would need to be conducted. The most significant finding is that no adverse outcomes were reported from the use of melatonin. There seems to be very limited toxicity of this chemical in the context of what can be very toxic exposures during chemotherapy. This characteristic would make larger clinical trials of melatonin feasible.

Although it is a proven antioxidant, it is not clear that melatonin supplementation would have a significant protective effect in disease-free individuals, or a selective protective effect in cancer patients undergoing radio- or chemotherapy (Ref. 104). Melatonin supplementation has proven efficacy in mitigating the effects of shift work or sleep deprivation. Although the connection between disruption of the circadian rhythm and carcinogenesis has not been established mechanistically, studies suggest that it is probably the result of low circulating levels of melatonin. This chronobiotic hormone needs to be given at appropriate times of the day to achieve maximum efficacy on treating or preventing breast cancer. The possibility that its connection with regulation of the circadian rhythm would result in different effects of melatonin when administered at different times during the day has generally reduced the enthusiasm to develop it as a clinical treatment, and, if true, has also probably contributed to the ambiguity in clinical data.

Probably the most important property of melatonin administration in humans, and the one that may eventually allow it to proceed to treatment, is its lack of toxicity. Thus, melatonin may be added to large clinical trials with a theoretical possibility of its improving the efficacy of treatment and with little concern that it will interfere with the action of the primary agent (genotoxic or immunological). Although recent studies by the Lissoni group have involved larger experimental populations (Ref. 105), ultimately, clinically beneficial effects of melatonin will be demonstrated only through its addition to large multicentre studies targeting specific tumour types in conjunction with specific types of therapy.

Use of MCF-7 cells as a cancer cell model

It is worth adding a comment on the widespread use of the established breast-cancer-derived cell line MCF-7. This cell line represents the product of a stage IV breast tumour metastasised to the pleural sack around the lung of a patient who eventually died of breast cancer. The cell line has also been in culture for over 20 years and has an amplification of the ERα gene of approximately 140 times the normal copy number (Ref. 106). The putative oncostatic/ antiproliferative properties of melatonin have been demonstrated primarily in these MCF-7 cells, as opposed to other cell lines from other tumour types (Refs 107, 108). The theory that melatonin may exert its effects through its effect on ER may be affected by the fact that this cell line overexpresses the ERα gene. However, there are discrepancies within the MCF-7 melatonin literature, which may be explained by the chromosomal instability of MCF-7 (Refs 109, 110).

Use of other in vivo model systems to study melatonin and cancer

Fewer studies using melatonin have utilised xenograft models or animal models of tumour growth as opposed to in vitro studies. These in vivo studies must be performed because the in vitro studies cannot deal with the possibility that tumours themselves may have circadian rhythms and may manifest peak times for treatment regimens. Tumours can also alter local and systemic regulatory systems. In addition, in vitro systems cannot simulate the complex interactions between host responses to the melatonin (natural and exogenous) and to the tumour itself.

Modification of the design of future clinical trials

If melatonin levels in urine or serum are indicative of cancer risk or prognosis, they would constitute a relatively simple and noninvasive method of population biomonitoring. However, based on the preliminary studies summarised above, it is likely that melatonin measurements would be more useful as part of a larger screening strategy that included a number of markers (Ref. 111). One way to develop such a screening panel would be through high-content, high-throughput analyses of tumours themselves (Ref. 112). For example, probes to measure the expression levels of several genes related to melatonin biosynthesis, metabolism and signal transduction are present in commercially available chips (Table 1), and the data from such experiments are required to be deposited in open on-line databases upon publication. Thus, using such modern techniques, screening experiments targeting other markers concurrently provide data on the relevance of melatonin-related genes in cancer. Even if not ‘hypothesis-driven’, analysis of such studies is usually confined to only the few genes showing the greatest differences in expression, and such markers may not prove to be the most consistent and reproducible. However, even if changes in melatonin-related gene expression are directly and causally implicated in carcinogenesis, they themselves may not provide the best biomarker of the process. Similarly, measurements of melatonin itself and its metabolites are present in proteomic screens of blood and urine from cancer patients (Ref. 113), but here it may be more difficult to identify melatonin-related fragments unless they are specifically detected immunologically or by sequencing and taken at peak times of melatonin secretion.

Table 1.

Melatonin-related probes on the Affymetrix U133 + 2 gene chipa

| Melatonin-related component | Affymetrix probe set | Reference sequence Accession Number | Gene symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melatonin receptors | |||

| Melatonin receptor 1A (MT1) | 221369_at | NM_005958 | MTNR1A |

| Melatonin receptor 1B (MT2) | 208516_at | NM_005959 | MTNR1B |

| Histone cluster 1, H2bm | 208515_at | NM_003521 | HIST1H2BM |

| Melatonin-related receptor, GPR50 | 208311_at | NM_004224 | GPR50 |

| Melatonin biosynthesis | |||

| Acetylserotonin-O-methyltransferase | 210551_s_at 206779_s_at |

BC001620 NM_004043 |

ASMT |

| Crystallin, beta B2 | 206778_s_at | NM_000496 | CRYBB2 |

| Partner of NOB1 homologue | 203622_s_at | NM_020143 | PNO1 |

| Acetylserotonin-O-methyltransferase-like | 36553_at 36554_at 209394_at |

AA669799 Y15521 BC002508 |

ASMTL |

| Melatonin metabolism | |||

| Cytochrome P450 1A2 | 207608_s_at 207609_s_at |

NM_000761 | CYP1A2 |

| Arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase | 207225_at | NM_001088 | AANAT |

| NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 2 | 203814_s_at | NM_000904 | NQO2 |

For further information on this particular chip offered by Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA, see: http://www.affymetrix.com/support/technical/datasheets/human_datasheet.pdf.

Future considerations for using melatonin as a therapy for breast cancer

More fundamental research in the area of melatonin is imperative. It still needs to be determined what constitutes a physiological dose of melatonin, as discussed in Ref. 114. Melatonin activates its membrane receptors and its lipophilic nature also allows it to traverse plasma membranes and accumulate within the cell. Even though circulating concentrations of melatonin at night range between 50 and 100 pg/ml (Ref. 1), nanomolar to micromolar concentrations of melatonin may be reached within or near the cell dependent upon the concentrating abilities of the tissue. Melatonin shows efficacy as an oncostatic agent using concentrations that range between high picomolar to low micromolar. Whether these levels are reached physiologically in tissue still needs to be ascertained, but for now these levels should be the therapeutic targets when designing future studies. More fundamental research with respect to determining the signalling mechanisms modulated by melatonin in tumours needs to be pursued, considering that the efficacy of melatonin to retard or prevent breast cancer is variable and may depend on the type of cancer (Ref. 66). Additionally, other models, both cellular and in vivo, should be used to verify the mechanisms underlying melatonin action as it relates to cellular differentiation.

More translational research is warranted seeing that the World Health Organization (WHO) and International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classify night-shift work as a potential carcinogen. Elucidating how light at night affects breast cancer risk, and whether or not melatonin supplementation at night shows any efficacy to prevent and/or treat breast cancer, should be given top priority when conducting clinical trials to direct future research. The clinical trials should be expanded to include a more heterogeneous population of individuals from around the world and be hypothesis driven. Factors like dosage and timing of dose need to be ascertained and genomic endpoints determined with respect to the use of melatonin as a treatment for breast cancer (Fig. 2; Table 1). The findings that melatonin inhibits the oestrogen-dependent signalling cascades should lead to more studies in this area (both basic and clinical) to determine if melatonin shows a synergistic interaction with mainstay therapies using tamoxifen, raloxifene or fulvestrant (Refs 29, 40, 115). The outcome(s) of these endeavours could lead to the novel use of melatonin in the clinic for the prevention and/ or treatment of breast cancer. The results of such studies could benefit many.

Figure 2. Clinical considerations for use of melatonin.

As shown in this schematic, factors that disrupt the circadian rhythm (e.g. light at night, sleep deprivation, shift work, chronic jet lag and ageing) may increase susceptibility to oxidative damage through a suppression of the nocturnal melatonin surge (dotted line). The goal of therapy, then, would be to restore one’s nocturnal melatonin levels back to normal (solid line) by supplementing with melatonin at night (dosage still needs to be determined) and by reducing night-time light exposure.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements and funding

The authors thank the peer reviewers for their thoughtful insight and expert comments and suggestions.

References

- 1.Reiter RJ. Pineal melatonin: cell biology of its synthesis and of its physiological interactions. Endocrine Reviews. 1991;12:151–180. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-2-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandi-Perumal SR, et al. Role of the melatonin system in the control of sleep: therapeutic implications. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:995–1018. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witt-Enderby PA, et al. Melatonin receptors and their regulation: biochemical and structural mechanisms. Life Sciences. 2003;72:2183–2198. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poirel VJ, et al. MT1 melatonin receptor mRNA expression exhibits a circadian variation in the rat suprachiasmatic nuclei. Brain Research. 2002;946:64–71. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02824-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gauer F, et al. Daily rhythms of melatonin binding sites in the rat pars tuberalis and suprachiasmatic nuclei; evidence for a regulation of melatonin receptors by melatonin itself. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;57:120–126. doi: 10.1159/000126350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gauer F, et al. Daily variations in melatonin receptor density of rat pars tuberalis and suprachiasmatic nuclei are distinctly regulated. Brain Research. 1994;641:92–98. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91819-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostrowska Z, et al. Influence of lighting conditions on daily rhythm of bone metabolism in rats and possible involvement of melatonin and other hormones in this process. Endocrine Regulations. 2003;37:163–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey MJ, et al. Transcriptional profiling of the chick pineal gland, a photoreceptive circadian oscillator and pacemaker. Molecular Endocrinology. 2003;17:2084–2095. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey MJ, et al. Transcriptional profiling of circadian patterns of mRNA expression in the chick retina. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:52247–52254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405679200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blask DE, Sauer LA, Dauchy RT. Melatonin as a chronobiotic/anticancer agent: cellular, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of action and their implications for circadian-based cancer therapy. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2002;2:113–132. doi: 10.2174/1568026023394407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutter J, Reick M, McKnight SL. Metabolism and the control of circadian rhythms. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2002;71:307–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.090501.142857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ravindra T, Lakshmi NK, Ahuja YR. Melatonin in pathogenesis and therapy of cancer. Indian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2006;60:523–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jasser SA, Blask DE, Brainard GC. Light during darkness and cancer: relationships in circadian photoreception and tumor biology. Cancer Causes and Control. 2006;17:515–523. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-9013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiter RJ, et al. Light at night, chronodisruption, melatonin suppression, and cancer risk: a review. Critical Reviews in Oncogenesis. 2007;13:303–328. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v13.i4.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shadan FF. Circadian tempo: a paradigm for genome stability? Medical Hypotheses. 2007;68:883–891. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valtonen M, et al. Effect of melatonin-rich night-time milk on sleep and activity in elderly institutionalized subjects. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;59:217–221. doi: 10.1080/08039480510023034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gubin DG, et al. The circadian body temperature rhythm in the elderly: effect of single daily melatonin dosing. Chronobiology International. 2006;23:639–658. doi: 10.1080/07420520600650612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks F, Furstenberger G, Muller-Decker K. Tumor promotion as a target of cancer prevention. Recent Results in Cancer Research. 2007;174:37–47. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-37696-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panzer A, Viljoen M. The validity of melatonin as an oncostatic agent. Journal of Pineal Research. 1997;22:184–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1997.tb00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vijayalaxmi, et al. Melatonin: from basic research to cancer treatment clinics. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:2575–2601. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cos S, Sanchez-Barcelo EJ. Melatonin, experimental basis for a possible application in breast cancer prevention and treatment. Histology and Histopathology. 2000;15:637–647. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cos S, Sanchez-Barcelo EJ. Melatonin and mammary pathological growth. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2000;21:133–170. doi: 10.1006/frne.1999.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenoir V, et al. Preventive and curative effect of melatonin on mammary carcinogenesis induced by dimethylbenz[a]anthracene in the female Sprague-Dawley rat. Breast Cancer Research. 2005;7:R470–476. doi: 10.1186/bcr1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blask DE, et al. Melatonin-depleted blood from premenopausal women exposed to light at night stimulates growth of human breast cancer xenografts in nude rats. Cancer Research. 2005;65:11174–11184. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cos S, Blask DE. Melatonin modulates growth factor activity in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Journal of Pineal Research. 1994;17:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1994.tb00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baturin DA, et al. The effect of light regimen and melatonin on the development of spontaneous mammary tumors in HER-2/neu transgenic mice is related to a downregulation of HER-2/neu gene expression. Neuroendocrinology Letters. 2001;22:441–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rato AG, et al. Melatonin blocks the activation of estrogen receptor for DNA binding. FASEB Journal. 1999;13:857–868. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.8.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiefer T, et al. Melatonin inhibits estrogen receptor transactivation and cAMP levels in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2002;71:37–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1013301408464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez-Barcelo EJ, et al. Melatonin-estrogen interactions in breast cancer. Journal of Pineal Research. 2005;38:217–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.del Rio B, et al. Melatonin, an endogenous-specific inhibitor of estrogen receptor alpha via calmodulin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:38294–38302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satomura K, et al. Melatonin at pharmacological doses enhances human osteoblastic differentiation in vitro and promotes mouse cortical bone formation in vivo. Journal of Pineal Research. 2007;42:231–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez-Hidalgo M, et al. Melatonin inhibits fatty acid-induced triglyceride accumulation in ROS17/2.8 cells: implications for osteoblast differentiation and osteoporosis. American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2007;292:R2208–2215. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00013.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuster C, et al. The human MT1 melatonin receptor stimulates cAMP production in the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y cells via a calcium-calmodulin signal transduction pathway. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2005;17:170–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnston JD, et al. Regulation of MT melatonin receptor expression in the foetal rat pituitary. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2006;18:50–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radio NM, Doctor JS, Witt-Enderby PA. Melatonin enhances alkaline phosphatase activity in differentiating human adult mesenchymal stem cells grown in osteogenic medium via MT2 melatonin receptors and the MEK/ERK (1/2) signaling cascade. Journal of Pineal Research. 2006;40:332–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sainz RM, et al. Melatonin reduces prostate cancer cell growth leading to neuroendocrine differentiation via a receptor and PKA independent mechanism. Prostate. 2005;63:29–43. doi: 10.1002/pros.20155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bellon A, et al. Melatonin induces neuritogenesis at early stages in N1E-115 cells through actin rearrangements via activation of protein kinase C and Rho-associated kinase. Journal of Pineal Research. 2007;42:214–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moriya T, et al. Melatonin influences the proliferative and differentiative activity of neural stem cells. Journal of Pineal Research. 2007;42:411–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jimenez-Jorge S, et al. Melatonin synthesis and melatonin-membrane receptor (MT1) expression during rat thymus development: role of the pineal gland. Journal of Pineal Research. 2005;39:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witt-Enderby PA, et al. Therapeutic treatments potentially mediated by melatonin receptors: potential clinical uses in the prevention of osteoporosis, cancer and as an adjuvant therapy. Journal of Pineal Research. 2006;41:297–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bondi CD, et al. MT1 melatonin receptor internalization underlies melatonin-induced morphologic changes in Chinese hamster ovary cells and these processes are dependent on Gi proteins, MEK 1/2 and microtubule modulation. Journal of Pineal Research. 2008;44:288–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jarzynka MJ, et al. Modulation of melatonin receptors and G-protein function by microtubules. Journal of Pineal Research. 2006;41:324–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witt-Enderby PA, Dubocovich ML. Characterization and regulation of the human ML1A melatonin receptor stably expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Molecular Pharmacology. 1996;50:166–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brydon L, et al. Dual signaling of human Mel1a melatonin receptors via G(i2), G(i3), and G(q/ 11) proteins. Molecular Endocrinology. 1999;13:2025–2038. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.12.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cini G, et al. Antiproliferative activity of melatonin by transcriptional inhibition of cyclin D1 expression: a molecular basis for melatonin-induced oncostatic effects. Journal of Pineal Research. 2005;39:12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dai J, et al. Modulation of intracellular calcium and calmodulin by melatonin in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Journal of Pineal Research. 2002;32:112–119. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2002.1844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martinez-Campa C, et al. Melatonin inhibits both ER alpha activation and breast cancer cell proliferation induced by a metalloestrogen, cadmium. Journal of Pineal Research. 2006;40:291–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roy D, et al. Cyclical regulation of GnRH gene expression in GT1–7 GnRH-secreting neurons by melatonin. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4711–4720. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cos S, et al. Melatonin modulates aromatase activity in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Journal of Pineal Research. 2005;38:136–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cos S, et al. Melatonin inhibits the growth of DMBA-induced mammary tumors by decreasing the local biosynthesis of estrogens through the modulation of aromatase activity. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;118:274–278. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reiter RJ, et al. Melatonin and its metabolites: new findings regarding their production and their radical scavenging actions. Acta Biochimica Polonica. 2007;54:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tan DX, et al. Melatonin as a naturally occurring co-substrate of quinone reductase-2, the putative MT3 melatonin membrane receptor: hypothesis and significance. Journal of Pineal Research. 2007;43:317–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nosjean O, et al. Identification of the melatonin-binding site MT3 as the quinone reductase 2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:31311–31317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005141200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nosjean O, et al. Comparative pharmacological studies of melatonin receptors: MT1, MT2 and MT3/QR2. Tissue distribution of MT3/QR2. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2001;61:1369–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dziegiel P, Podhorska-Okolow M, Zabel M. Melatonin: adjuvant therapy of malignant tumors. Medical Science Monitor. 2008;14:RA64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pawlikowski M, Winczyk K, Karasek M. Oncostatic action of melatonin: facts and question marks. Neuroendocrinolology Letters. 2002;23(Suppl 1):24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moss RW. Cancer and complementary and alternative medicine in Italy: personal observations and historical considerations. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2004;3:173–188. doi: 10.1177/1534735404265032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lissoni P, et al. Modulation of interleukin-2-induced macrophage activation in cancer patients by the pineal hormone melatonin. Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents. 1991;5:154–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carrillo-Vico A, et al. Melatonin counteracts the inhibitory effect of PGE2 on IL-2 production in human lymphocytes via its mt1 membrane receptor. FASEB Journal. 2003;17:755–757. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0501fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leon-Blanco MM, et al. Melatonin inhibits telomerase activity in the MCF-7 tumor cell line both in vivo and in vitro. Journal of Pineal Research. 2003;35:204–211. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2003.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reiter RJ, et al. Augmentation of indices of oxidative damage in life-long melatonin-deficient rats. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 1999;110:157–173. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(99)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morioka N, Okatani Y, Wakatsuki A. Melatonin protects against age-related DNA damage in the brains of female senescence-accelerated mice. Journal of Pineal Research. 1999;27:202–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1999.tb00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anisimov VN, et al. Dose-dependent effect of melatonin on life span and spontaneous tumor incidence in female SHR mice. Experimental Gerontology. 2003;38:449–461. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00240-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vinogradova IA, et al. Effect of light regimens and melatonin on the homeostasis, life span and development of spontaneous tumors in female rats. Advances in Gerontology. 2007;20:40–47. Article in Russian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Braeckman BP, Demetrius L, Vanfleteren JR. The dietary restriction effect in C. elegans and humans: is the worm a one-millimeter human? Biogerontology. 2006;7:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s10522-006-9003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bartsch C, Bartsch H. The anti-tumor activity of pineal melatonin and cancer enhancing life styles in industrialized societies. Cancer Causes and Control. 2006;17:559–571. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-9011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Davis S, Mirick DK. Circadian disruption, shift work and the risk of cancer: a summary of the evidence and studies in Seattle. Cancer Causes and Control. 2006;17:539–545. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-9010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moriya T, et al. Correlative association between circadian expression of mousePer2 gene and the proliferation of the neural stem cells. Neuroscience. 2007;146:494–498. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gery S, et al. Transcription profiling of C/EBP targets identifies Per2 as a gene implicated in myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:2827–2836. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen ST, et al. Deregulated expression of the PER1, PER2 and PER3 genes in breast cancers. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1241–1246. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Migliore L, Coppede F. Genetic and environmental factors in cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Mutation Research. 2002;512:135–153. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(02)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nogues MR, et al. Melatonin reduces oxidative stress in erythrocytes and plasma of senescence-accelerated mice. Journal of Pineal Research. 2006;41:142–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Loft S, Poulsen HE. Cancer risk and oxidative DNA damage in man. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 1996;74:297–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00207507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schernhammer ES, et al. Epidemiology of urinary melatonin in women and its relation to other hormones and night work. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2004;13:936–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Megdal SP, et al. Night work and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cancer. 2005;41:2023–2032. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schernhammer ES, Hankinson SE. Urinary melatonin levels and breast cancer risk. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97:1084–1087. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Travis RC, et al. Melatonin and breast cancer: a prospective study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004;96:475–482. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blask DE. Melatonin in oncology. In: Yu H-S, Reiter RJ, editors. Melatonin: Biosynthesis, Physiological Effects and Clinical Applications. CRC Press; Boca Raton, USA: 1993. pp. 447–476. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tarquini B, et al. Daytime circulating melatonin levels in smokers. Tumori. 1994;80:229–232. doi: 10.1177/030089169408000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bartsch C, et al. Diminished pineal function coincides with disturbed circadian endocrine rhythmicity in untreated primary cancer patients. Consequence of premature aging or of tumor growth? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1994;719:502–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb56855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bartsch C, et al. Nocturnal urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin and proliferating cell nuclear antigen-immunopositive tumor cells show strong positive correlations in patients with gastrointestinal and lung cancer. Journal of Pineal Research. 1997;23:90–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1997.tb00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Blask DE. The melatonin rhythm in cancer patients. In: Shafii M, Shafii SL, editors. Melatonin in Psychiatric and Neoplastic Disorders. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, D.C., USA: 1997. pp. 243–260. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. Effect of tumor-derived cytokines and growth factors on differentiation and immune suppressive features of myeloid cells in cancer. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2006;25:323–331. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9002-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kawanishi S, Hiraku Y. Oxidative and nitrative DNA damage as biomarker for carcinogenesis with special reference to inflammation. Antioxidants and Redox Signalling. 2006;8:1047–1058. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen R, et al. Inflammation, cancer and chemoresistance: taking advantage of the toll-like receptor signaling pathway. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2007;57:93–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2006.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Burch JB, et al. Melatonin and estrogen in breast cyst fluids. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2007;103:331–341. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9372-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maestroni GJ, Conti A. Melatonin in human breast cancer tissue: association with nuclear grade and estrogen receptor status. Laboratory Investigation. 1996;75:557–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Poeggeler B. Melatonin, aging, and age-related diseases: perspectives for prevention, intervention, and therapy. Endocrine. 2005;27:201–212. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:27:2:201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Poeggeler B, et al. Melatonin, hydroxyl radical-mediated oxidative damage, and aging: a hypothesis. Journal of Pineal Research. 1993;14:151–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1993.tb00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brozmanova J, Dudas A, Henriques JA. Repair of oxidative DNA damage–an important factor reducing cancer risk. Minireview. Neoplasma. 2001;48:85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Becr VII Phase 2. Health Risks from Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C., USA: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vesnushkin GM, et al. Dose-dependent inhibitory effect of melatonin on carcinogenesis induced by benzo[a]pyrene in mice. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;25:507–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lissoni P, et al. Prevention of cytokine-induced hypotension in cancer patients by the pineal hormone melatonin. Supportive Care in Cancer. 1996;4:313–316. doi: 10.1007/BF01358887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Norsa A, Martino V. Somatostatin, retinoids, melatonin, vitamin D, bromocriptine, and cyclophosphamide in chemotherapy-pretreated patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma and low performance status. Cancer Biotherapy and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2007;22:50–55. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2006.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lissoni P, et al. A biological study on the efficacy of low-dose subcutaneous interleukin-2 plus melatonin in the treatment of cancer-related thrombocytopenia. Oncology. 1995;52:360–362. doi: 10.1159/000227489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lissoni P, et al. The pineal hormone melatonin in hematology and its potential efficacy in the treatment of thrombocytopenia. Recenti Progressi in Medicina. 1996;87:582–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lissoni P, et al. Is there a role for melatonin in the treatment of neoplastic cachexia? European Journal of Cancer. 1996;32A:1340–1343. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cos S, et al. Estrogen-signaling pathway: a link between breast cancer and melatonin oncostatic actions. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2006;30:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Treilleux, et al. Human estrogen receptor (ER) gene promoter-P1: estradiol-independent activity and estradiol inducibility in ER+ and ER-cells. Molecular Endocrinology. 1997;11:1319–1331. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.9.9973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cunat S, Hoffmann P, Pujol P. Estrogens and epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2004;94:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Naderi A, et al. BEX2 is overexpressed in a subset of primary breast cancers and mediates nerve growth factor/nuclear factor-kappaB inhibition of apoptosis in breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Research. 2007;67:6725–6736. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tiligada E. Chemotherapy: induction of stress responses. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2006;13(Suppl 1):S115–124. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mills E, et al. Melatonin in the treatment of cancer: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis. Journal of Pineal Research. 2005;39:360–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vijayalaxmi, et al. Melatonin as a radioprotective agent: a review. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2004;59:639–653. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lissoni P. Biochemotherapy with standard chemotherapies plus the pineal hormone melatonin in the treatment of advanced solid neoplasms. Pathologie-Biologie. 2007;55:201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jonsson G, Staaf J, Olssen E, Heidenblad M, Vallon-Christersson J, Osoegawa K, de Jong P, Oredsson S, Ringr M, Hoglund M, Borg A. High-resolution genomic profiles of breast cancer cell lines assessed by tiling BAC array comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46:543–558. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Crespo D, et al. Interaction between melatonin and estradiol on morphological and morphometric features of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Journal of Pineal Research. 1994;16:215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1994.tb00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hill SM, Blask DE. Effects of the pineal hormone melatonin on the proliferation and morphological characteristics of human breast cancer cells (MCF-7) in culture. Cancer Research. 1988;48:6121–6126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wenger SL, et al. Comparison of established cell lines at different passages by karyotype and comparative genomic hybridization. Bioscience Reports. 2004;24:631–639. doi: 10.1007/s10540-005-2797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Klein A, et al. Different mechanisms of mitotic instability in cancer cell lines. International Journal of Oncology. 2006;29:1389–1396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chatterjee SK, Zetter BR. Cancer biomarkers: knowing the present and predicting the future. Future Oncology. 2005;1:37–50. doi: 10.1517/14796694.1.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang Y, et al. Gene expression profiles and prognostic markers for primary breast cancer. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2007;377:131–138. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-390-5_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Stemke-Hale K, et al. Molecular screening for breast cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment planning: combining biomarkers from DNA, RNA, and protein. Current Oncology Reports. 2006;8:484–491. doi: 10.1007/s11912-006-0078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Reiter RJ, Tan DX. What constitutes a physiological concentration of melatonin? Journal of Pineal Research. 2003;34:79–80. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2003.2e114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Aust S, et al. Biotransformation of melatonin in human breast cancer cell lines: role of sulfotransferase 1A1. Journal of Pineal Research. 2005;39:276–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]