Abstract

Earlier, we found estrogen receptor (ER) ligands having a novel three-dimensional oxabicyclo[2.2.1]heptene core scaffold and good ER binding affinity acted as partial agonists via small alkyl ester substitutions on the bicyclic core that indirectly modulate the critical switch helix in the ER ligand-binding domain, helix 12, by interactions with helix 11. This contrasts with the mechanism of action of tamoxifen, which directly pushes helix 12 out of the conformation required for gene activation. We now report that a much larger substitution can be tolerated at this position of the bicyclic core scaffold, namely a phenyl sulfonate group, which defines a novel binding epitope for the estrogen receptor. We prepared an array of 14 of these oxabicycloheptene sulfonates (OBHS), varying the phenyl sulfonate group. As with OBHS itself, these compounds showed preferential affinity for ERα, and the disposition and size of the phenyl substituents were important determinants of the binding affinity and selectivity of these compounds, with those having ortho substituents giving the highest, and para substituents the lowest affinities for ERα. A few analogs have ERα binding affinity that is comparable to or, in the case of the ortho chloro analog, higher than that of OBHS itself. In cell-based studies, we found several compounds with activity profiles comparable to tamoxifen, but acting entirely as indirect antagonists, allosterically interfering with recruitment of coactivator proteins to the receptor. Thus, the OBHS binding epitope represents a novel approach to the development of estrogen receptor antagonists via an indirect mechanism of antagonism.

Keywords: Steroids, Cycloaddition, Estrogen, Estrogen Receptor, Hormones

Introduction

Estrogens, such as the endogenous hormone estradiol (E2), are important mediators of many physiological functions related to development, growth, and maintenance of reproductive as well as non-reproductive tissues in both men and women.[1] The effects of estrogens are mediated via two estrogen receptor subtypes, ERα and ERβ,[2] which have different tissue distributions and significant differences in their ligand-binding preferences.[3] Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), compounds that show differential levels of agonistic vs. antagonistic activity in different estrogen target tissues, as well as ER subtype-selective ligands, have been investigated intensively in recent years in the search for estrogens that have improved patterns of target-tissue selectivity.[4]

Structural studies of the ligand binding pockets of both ERα and ERβ reveal substantial unoccupied space above and below the mean plane of the endogenous ligand E2, particularly near the middle of this molecule (namely, below the B ring and above the C ring),[5] as well as considerable flexibility in the shape of the ligand binding pocket.[6] While these characteristics of how different estrogens bind to the ERs have been known for several years,[5, 7] there have been only sporadic attempts to exploit this unfilled space and flexibility of the ER binding pocket as an approach to enhance ligand binding affinity, SERM behavior, or ER subtype selectivity. Nevertheless, a number of ER ligands having diverse three-dimensional chemical scaffolds have emerged: representative examples are based on ferrocene,[8] carboranes,[1a, 9] bridged polycyclics,[10] and some other cyclopentadienyl metal tricarbonyl complexes (Figure 1).[11] We have contributed to this area as well.[7a]

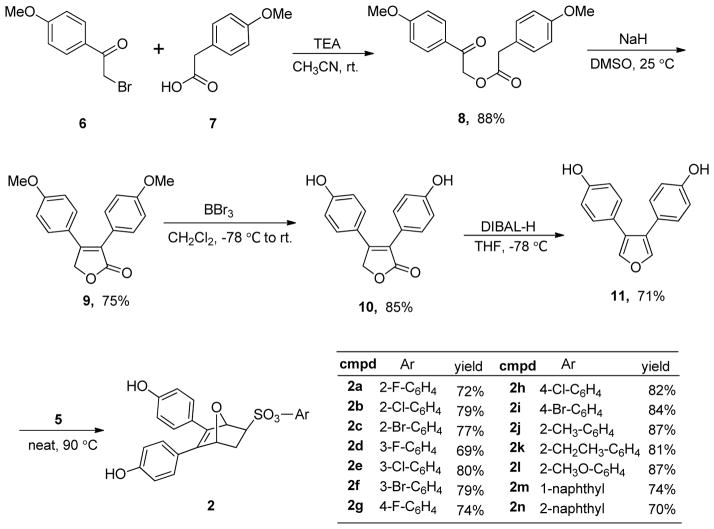

Figure 1.

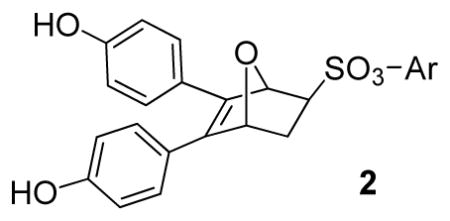

Structure of estradiol, examples of ER ligands having three-dimensional elements or core structures, OBHS (1) and title compounds (2).

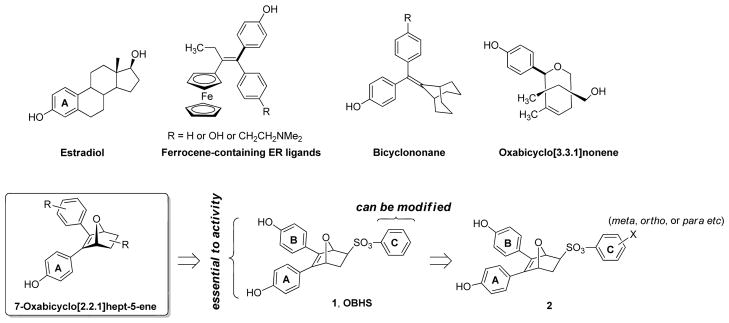

The formula for making ER antagonists is well established: Take an agonist ligand and add a bulky side chain to disrupt helix 12 (Figure 2A–B). Structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies are then done to optimize for antagonist activity and potency. We previously discovered that certain small substitutions at different sites on agonist ligands could yield partial agonists, which we called passive, or indirect antagonists because they modulate helix 12 indirectly, by inducing small shifts in helix 11.[12] These include a series of oxabicyclic bridged compounds with small alkyl ester substitutions directed towards ER helix 11; these had relatively low affinity, which suggested a limited potential for expanding SAR.[7a] Intriguingly, however, one member of this series, OBHS (1), displayed a much larger, bulky side group, a phenyl sulfonate, yet bound better than those analogs with smaller substituents.[7a] This suggested to us that there might actually be room for much more extensive perturbation of the ligand binding pocket in this region than we had envisioned.

Figure 2.

OBHS side chain binds in a new epitope between helices 8 and 11.

A) Crystal structure of the ERα LBD in complex with diethylstilbestrol (DES) (PDB ID: 3ERD). The side chains of the helix 3 and helix 11 residues, Glu353 and His524, both of which engage in hydrogen bonding with DES are shown. B) Crystal structure of the ERα LBD in complex with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT) (PDB ID: 3ERT). The SERM side chain of 4OHT (green) displaces helix 12 C) Crystal structure of the ERα LBD in complex with OBHS at 2.1 Å resolution. The position of His524 in the estradiol-bound structure is shown with faint lines. Notably, the phenylsulfonate moiety (green) of OBHS binds in a new epitope that significantly shifts helix 11.

The structure of OBHS supports this hypothesis, and led us to prepare a series of derivatives targeting this novel binding epitope. Using a series of cell-based assays in liver and breast cancer cells, we identify several compounds with higher potency than OBHS, and better activity profiles, matching the level of antagonism seen with tamoxifen. This work thus demonstrates a structure-based design approach to blocking ER activity via a novel binding epitope and an indirect mechanism of antagonism.

Results and Discussion

Structure of OBHS bound ERα

The previously reported ERα structures of complexes of the agonist diethylstilbestrol (DES) (Figure 2A) and the SERM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT) (Figure 2B)[13] illustrate how the bulky side group of tamoxifen directly relocates helix 12, thereby destroying the surface bound coactivator binding site required for gene activation. In contrast, the bulky side group of OBHS exits the receptor between helices 11 and 8, and in doing so significantly shifts helix 11 and His524 (Figure 2C). Since OBHS profiles as a partial agonist (see below), we prepared a series of modifications on the phenyl group to explore whether this novel epitope can be used to drive antagonist activity to a level comparable to that of tamoxifen.

Synthesis

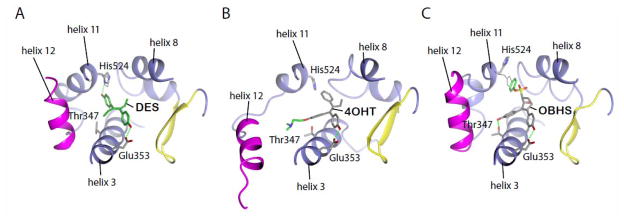

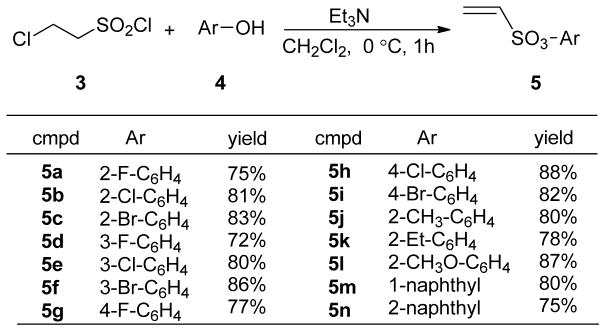

The synthesis of the oxabicyclic bridged compounds 2 was effectively accomplished, as before, by a Diels-Alder reaction of the 3,4-diarylfuran 11 with a variety of dienophiles 5. The dienophiles 5 were prepared according to a modified literature procedure by the reaction of 2-chloroethanesulfonyl chloride 3 with substituted phenols 4a–m in the presence of triethylamine, and they were obtained in generally good yields (Scheme 1).[7a, 14] The synthesis of diarylfuran 11 was accomplished using an improved procedure, as shown in Scheme 2. α-Bromo-4-methoxyacetophenone 6 reacted with arylacetic acid 7 in the presence of Et3N in CH3CN to give the condensation product 8 in 88% yield.[15] In contrast, our previous procedure to produce 8 required condensation of the potassium salts of arylacetic acids 7 with 6 using 18-crown-6 as catalyst under refluxing conditions.[7a] Treatment of ester 8 with NaH in anhydrous DMSO gave the 2(5H)-furanone 9, which was demethylated with BBr3 to afford the butenolide 10 in 85% yield,[16] avoiding our prior use of pyridinium chloride at 220 °C to get the free phenols.[7a] Diisobutylaluminum hydride reduction of 10 at −78 °C gave, after a careful, low-temperature acidic workup, the 3,4-diphenol furans 11. Finally, a Diels-Alder reaction of 11 with the dienophiles 5 produced compounds 2a–2n. It is noteworthy, similar to our previous study, that high stereoselectivity was observed in the cycloaddition reaction of the phenolic furans with the dienophiles, the exo product being obtained nearly exclusively; only traces, if any, of endo products were observed.[7a] This exo selectivity is presumed due to the high rate, and ready reversibility of the Diels-Alder reaction of furans, which allows the thermodynamically favored exo product to become dominant.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of dienophiles 5a–n.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of OBHS derivatives 2a–n using an improved procedure.

Binding Affinity and Structure-Activity Relationships

The compounds were assayed for their binding affinity to ERα and ERβ by a competitive radiometric binding assay.[17] These affinities are expressed as relative binding affinity (RBA) values; RBA values are reported as percentages (%) of that of estradiol (E2), which is set at 100%. All of the 14 newly synthesized compounds were tested, and the results were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | cmpd | Ar | ERα | ERβ | α/β ratio |

| 1 | 1 |

|

9.28 ± 0.64 | 1.71 ±0.24 | 5.47 |

| 2 | 2a |

|

7.28 ± 0.26 | 2.24 ± 0.56 | 3.25 |

| 3 | 2b |

|

19.00 ±4.6 | 1.76 ±0.13 | 10.80 |

| 4 | 2c |

|

2.29 ± 0.02 | 0.419 ±0.07 | 5.42 |

| 5 | 2d |

|

1.76 ± 0.04 | 0.39 ± 0.06 | 4.51 |

| 6 | 2e |

|

1.91 ±0.46 | 0.357 ± 0.06 | 5.46 |

| 7 | 2f |

|

5.84 ± 0.28 | 0.707 ±0.05 | 8.26 |

| 8 | 2g |

|

1.18 ±0.13 | 0.494 ±0.12 | 2.39 |

| 9 | 2h |

|

0.78 ± 0.002 | 0.284 ± 0.003 | 2.75 |

| 10 | 2i |

|

0.76 ± 0.21 | 0.404 ±0.12 | 1.87 |

| 11 | 2j |

|

3.49 ± 0.63 | 0.294 ± 0.02 | 11.87 |

| 12 | 2k |

|

1.03 ±0.16 | 0.096 ± 0.02 | 10.72 |

| 13 | 2l |

|

4.39 ± 0.48 | 0.210 ±0.01 | 20.90 |

| 14 | 2m |

|

5.03 ±1.5 | 0.478 ±0.12 | 10.52 |

| 15 | 2n |

|

0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.019 ±0.005 | 2.79 |

Relative binding affinity (RBA) values were determined by competitive radiometric binding assays and are expressed as IC50estradiol/ IC50compound×100 ± the range or standard deviation (n = 2–3, RBA, estradiol = 100%). In these assays, the Kd for estradiol is 0.2 nM on ERα and 0.5 nM on ERβ.

Ki values of each compound for each receptor can be obtained from the RBA values by the formula Ki = (100/RBA)×Kd.

It is noteworthy that the disposition and the size of the substituent on the phenyl of the sulfonates prove to be important factors in determining the binding affinity and selectivity of these new compounds. Most of the ligands show moderate to excellent binding affinity, with 2b, a compound that possesses an ortho-chlorine substituent on phenyl of sulfonate, showing the highest RBA value, of 19.0% and 1.76% for ERα and ERβ, respectively, together with an improved selectivity—now over 10-fold—in favor of ERα (Table 1, entry 3). When the chlorine was replaced with a fluorine (2a) or bromine (2c), a progressive decrease of RBA values was observed (Table 1, entries 2 and 4). For the corresponding meta substituted compounds (2d–f), the fluoro (2d) and chloro (2e) analogues showed lower binding affinities, but the bromo analogue (2f) also gave good RBA values of 5.84% and 0.707% for ERα and ERβ, respectively (Table 1, entries 5–7). At the para position, all compounds gave rather low binding affinities (Table 1, entries 8–10). Previously, we prepared the p-hydroxy and p-methoxy analogs of OBHS, and they too had lower affinity.[7a]

One can conclude that, in terms of binding affinity, ortho substitution seems beneficial, while meta substitution has a more neutral effect, and para substitution is detrimental; at the ortho position, chloride is best, but bromine is favored at the meta position. Additional SAR investigations focused on the most promising class, the ortho-substituted series. Ortho-methyl analogue 2j maintained good affinity, and while the ortho-ethyl analogue 2k showed a significant drop in binding affinity, the methoxy group (2l) was well-tolerated (Table 1, entries 11–13). Interestingly, there was a more than 100-fold binding affinity difference between the 1- and 2-naphthyl OBHSs (2m and 2n) on ERα (Table 1, entries 14 and 15). In a sense, with respect to a phenyl group, the 1-naphthyl group combines substitution at the favorable and neutral ortho and meta positions, while the 2-naphthyl group begins to invade the poorly tolerant para position.

Transcription Activation through Estrogen Receptors α and β

The ability of these compounds to regulate ERα- and ERβ-mediated transcription was compared to that of tamoxifen in liver cells, in which tamoxifen displays agonist activity on ERα, but not ERβ, due to higher activity of the amino-terminal coactivator binding region in ERα.[18] Cells were transfected with vectors for full-length human ERα or ERβ, and a widely used estrogen-responsive element (ERE)-driven luciferase reporter gene.[19] OBHS and the 14 analogues (Table 2, agonist mode) exhibited weaker potency than E2, which activated ERα with an EC50 of 1–2 nM, and also lower efficacy. It is important to note that in HepG2 cells, used in the assays reported here, SERMs show higher partial agonist activity than in HEC-1 cells used previously.[7a, 18] In fact, 4OHT has an agonist activity that is 35% that of estradiol, although fulvestrandt is still a complete antagonist.[18]

Table 2.

Estrogen Receptor-Mediated Transcriptional Activities

| Entry | Cmpd | Agonist modea | Antagonist modeb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERα EC50 (nM)c | ERα (% E2) | ERβ (% E2) | MCF-7 (% E2) | ERβ IC50 (nM)c | ERβ (% E2) | ||

| 1 | 1 (OBHS) | 95 | 60 ± 2 | 0 ± 1 | 21 ± 4 | 581 | −16 ± 2 |

| 2 | 2a | 26 | 61 ± 5 | 0 ± 3 | 26 ± 4 | - | 54 ± 4 |

| 3 | 2b | - | 29 ± 5 | 1 ± 1 | −7 ± 2 | - | 86 ± 11 |

| 4 | 2c | 44 | 53 ± 5 | 2 ± 1 | 23 ± 3 | - | 11 ± 14 |

| 5 | 2d | 140 | 54 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | n.d | 453 | −19 ± 3 |

| 6 | 2e | 210 | 34 ± 1 | 1 ± 2 | n.d | - | −2 ± 5 |

| 7 | 2f | 300 | 33 ± 2 | 0 ± 1 | n.d | 248 | −26 ± 4 |

| 8 | 2g | 200 | 43 ± 6 | 1 ± 2 | n.d | 214 | −8 ± 5 |

| 9 | 2h | 360 | 36 ± 2 | 1 ± 5 | n.d | - | −15 ± 4 |

| 10 | 2i | 160 | 31 ± 6 | 4 ± 7 | −2 ± 2 | - | 61 ± 12 |

| 11 | 2j | 220 | 52 ± 5 | 1 ± 4 | n.d | 357 | −12 ± 2 |

| 12 | 2k | 390 | 33 ± 2 | 0 ± 1 | n.d | 3208 | −4 ± 4 |

| 13 | 2l | 560 | 40 ± 1 | 0 ± 2 | n.d | 1038 | 17 ± 9 |

| 14 | 2m | 46 | 29 ± 1 | 1 ± 2 | −4 ± 1 | - | 30 ± 3 |

| 15 | 2n | - | 48 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 | n.d | - | 52 ± 19 |

| 16 | Faslodex | - | 1 ± 1 | −1 ± 1 | −4 ± 4 | 1 | −23 ± 0 |

| 17 | 4-OHT | 1.08 | 35 ± 3 | −1 ± 1 | −11 ± 1 | 1 | −20 ± 2 |

Luciferase activity was measured in HepG2 cells transfected with 3X-ERE-driven luciferase reporter and expression vectors encoding ERα or ERβ, or where indicated in ERα+ MCF-7 cells with the ERE reporter, and treated in triplicate with increasing doses (up to 10−5 M) of the compounds. EC50, and average efficacy (mean ± s.e.m.), shown as a percentage of 10−5 M 17β-estradiol (E2), were determined. None of the compounds tested activated ERβ.

Average efficacy of the compounds (10−5 M) in combination with 10−6 M E2 (E2 only = 100%).

EC50 or IC50 values of some compounds was too high to be determined, indicated by a dash (−)

In HepG2 cells, three of compounds, 2a, 2c and 2m displayed improved EC50’s compared to OBHS 1 (Table 2). Generally, the aryl halides 2a–i showed a similar activity pattern, a trend where fluorine substitution results in higher efficacy than bromo substitution. A similar pattern is evident with the methyl substitution (2j) inducing greater activity than the ethyl (2k) or methoxy (2l). It is noteworthy that the much higher affinity 1-naphthyl isomer (2m) has lower activity on ERα than the 2-naphthyl isomer (2n), which has low affinity and low potency, but higher efficacy. This highlights the fact that affinity and potency (i.e., EC50) are independent of the allosteric conformational signals between ligand and the surface transcriptional coactivator binding site, which determine the activity or efficacy (i.e., intrinsic activity) of the compounds. Unexpected, was the low potency of the o-chloro compound (2b), which had the highest affinity on ERα. Beyond the factors just noted above, cell permeability and metabolism issues might also be contributing to its low potency, as well as the general difficulty in establishing EC50 values for compounds with low intrinsic activity. In this context, it is important to note that the corresponding o-fluoro and o-bromo compounds (2a and 2c) have good potency, but only slightly lower efficacy compared to OBHS.

None of the compounds activated ERβ as agonists in the HepG2 luciferase assay; so, they were profiled only as antagonists in the presence of 1 μM E2. Most of the compounds are antagonists selectively on ERβ (Table 2). Because ERβ has considerable basal activity, especially in HepG2 cells, compounds can be found to have inverse agonist activity, that is, an intrinsic activity that is less than that of apo-ERβ; such compounds are registered as having a negative efficacy value. While the size of the substituent predicted the activity on ERα, for ERβ, compounds having meta substitution (2d–f) were more consistently antagonistic. The naphthyl compounds (2m–n) showed similar activity profiles on both ER subtypes.

As a final test, a subset of the compounds with the lowest efficacy or potency were assayed for activation of 3xERE-luciferase activity in ERα-positive MCF-7 breast cancer cells, in which tamoxifen acts as an inverse agonist. While OBHS showed limited agonist activity, we identified several compounds with inverse agonist activity. Notably, 2m shows improved profile in all assays relative to OBHS, and an antagonist efficacy profile comparable to tamoxifen. While the affinity of 2m is lower than that of 4OHT, these results establish proof-of-principle that indirect antagonists can produce an activity profile comparable to tamoxifen, through by a different structural mechanism.

Conclusions

In summary, a small library of OBHS 1 analogs, differing in the substituents on the phenyl ring of the sulfonate, have been prepared and evaluated as ligands for ERα and ERβ. The substitution on the bulky phenyl sulfonate side group of OBHS is well tolerated and can engender a good binding affinity and antagonist efficacy profile. In transcription assays performed in HepG2 cells, some analogs activated ERα only partially and had little or no activity on ERβ, and a few compounds behaved as indirect antagonists exclusively on ERβ. Notably, several of the compounds showed full antagonism (even inverse agonism) on ERβ (e.g., 2d, 2f, 2h, and 2j), and most were partial agonist/antagonists on ERα. Importantly, several compounds also act as inverse agonists in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Because the bulky side group exits the receptor between helices 8 and 11, rather than towards helix 12, compounds such as 2m represent a novel structural class of SERMs. Interestingly, more than a 100-fold difference in binding affinity was observed between the 1- and 2-naphthyl OBHSs (2m and 2n) on ERα. Thus, despite the apparent constraints of the ER ligand-binding pocket noted in crystal structures of related compounds, analogs of OBHS with larger sulfonate aryl substituents can actually be more potent and active than OBHS itself. This is, again, a testament to the flexibility of the ligand binding pocket of the ERs and its ability to adapt to bind ligands of diverse structure with good affinity.[6, 20]

Experimental Section

Synthesis Materials and Methods

A complete description of the syntheses with experimental details and spectroscopic characterization is given in the Supporting Information. All compounds assayed were >95% pure as determined by HPLC analysis.

General Procedure for the Diels-Alder Reaction

The dienophiles 5 and 3,4-bisphenol-furan 11 were synthesized according to the modified previous method (see Supporting Information for details).[7a, 14] The BBr3-demethylations were performed according to published procedures.[16] Furan 12 (0.2mmol) and dienophiles 5 (0.24 mmol) were placed in a round flask, and the mixture was stirred under a N2 atmosphere at 100 °C for 12–24 h. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography (10–50% EtOAc/petroleum ether), preparative thin-layer chromatography, or recrystallization.

5,6-Bis-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonic Acid 2-Chlorophenyl Ester (2b)

2b was purified by flash chromatography (30% EtOAc/petroleum ether) to give a light yellow oil in 89% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.56–7.36 (m, 4H), 7.26–6.92 (m, 6H), 6.87–6.64 (m, 4H), 5.79 (d, J = 0.9 Hz, 1H), 5.40 (dd, J = 12.1, 7.5 Hz, 3H), 3.78 (dd, J = 8.4, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.64 (dt, J = 12.3, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.22 (dd, J = 12.2, 8.3 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.99, 155.95, 153.65, 149.56, 144.98, 141.46, 137.03, 130.90, 129.53, 128.87, 128.18, 128.06, 126.92, 124.55, 124.15, 123.87, 116.10, 115.93, 115.84, 114.90, 84.41, 83.03, 60.76, 30.68. HRMS (EI) calcd for C24H19ClO6SNa (M + Na+), 493.04486; found 493.04831.

Estrogen Receptor Binding Affinity Assays

Relative binding affinities were determined by a competitive radiometric binding assay, as previously described,[17b] using 10 nM [3H]estradiol as tracer (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and purified full-length human ERα and ERβ (PanVera/InVitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Incubations were for 18–24 h at 0 °C. Then the receptor-ligand complexes were absorbed onto hydroxyapatite (BioRad, Hercules, CA), and unbound ligand was washed away. The binding affinities are expressed as relative binding affinity (RBA) values, with the RBA of estradiol set to 100. The values given are the average ± range or SD of two or more independent determinations. Estradiol binds to ERα with a Kd of 0.2 nM and to ERβ with a Kd of 0.5 nM.

Luciferase Assay

HepG2 cells cultured in growth media containing Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium (DMEM) (Cellgro by Mediatech, Inc. Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone by Thermo Scientific, South Logan, UT), and 1% non-essential amino acids (Cellgro), Penicillin-Streptomycin-Neomycin antibiotic mixture and Glutamax (Gibco by Invitrogen Corp. Carlsbad, CA), were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells in 10 cm dishes were transfected with 10 ug of 3XERE-luciferase reporter plus 1.6 μg of ERα or ERβ expression vector per dish using FugeneHD reagent (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis IN). The next day, the cells were re-suspended in phenol red-free growth media supplemented with 10% charcoal-dextran sulfate-stripped FBS, transferred at a density of 20,000 cells/well to 384-well plates, incubated overnight at 37 °C and 5% CO2, and treated in triplicate with the various compounds. After 24 hours, luciferase activity was measured using BriteLite reagent (PerkinElmer Inc., Shelton, CT) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the NSFC (20872116, 20972121, 81172935), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-10-0625), the National Mega Project on Major Drug Development (2009ZX09301-014-1), and the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (20100141110021) for support of this research. Research support from the National Institutes of Health (PHS 5R37 DK015556 to J.A.K. and R01 DK077085 to K.W.N.) is gratefully acknowledged. We are grateful to Teresa Martin to help in the binding assays.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: E2, estradiol; ER, estrogen receptor; ERE, estrogen response element; OBHS, oxabicycloheptene sulfonate; ODE, oxabicycloheptene diethylester; SERMs, selective estrogen receptor modulators; RBA, relative binding affinity; HepG2, human liver cancer cells; THF, tetrahydrofuran.

Supporting Information Available: Synthetic procedures and characterization of compounds 5, 8–11 and 2; Summary of HPLC results and HPLC spectra of all final compounds 2. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at ######.

References

- 1.a Endo Y, Yoshimi T, Ohta K, Suzuki T, Ohta S. J Med Chem. 2005;48(12):3941–3944. doi: 10.1021/jm050195r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gustafsson JA. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24(9):479–485. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(12):5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pettersson K, Gustafsson JA. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:165–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a De Angelis M, Stossi F, Carlson KA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. J Med Chem. 2005;48(4):1132–1144. doi: 10.1021/jm049223g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gruber C, Gruber D. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;5(10):1086–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Jordan VC. J Med Chem. 2003;46(6):883–908. doi: 10.1021/jm020449y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Minutolo F, Bertini S, Granchi C, Marchitiello T, Prota G, Rapposelli S, Tuccinardi T, Martinelli A, Gunther JR, Carlson KE, Katzenellenbogen JA, Macchia M. J Med Chem. 2009;52(3):858–867. doi: 10.1021/jm801458t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Minutolo F, Macchia M, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Med Res Rev. 2011;31(3):364–442. doi: 10.1002/med.20186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Palkowitz AD, Glasebrook AL, Thrasher KJ, Hauser KL, Short LL, Phillips DL, Muehl BS, Sato M, Shetler PK, Cullinan GJ, Pell TR, Bryant HU. J Med Chem. 1997;40(10):1407–1416. doi: 10.1021/jm970167b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Zhou H-B, Carlson KE, Stossi F, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19(1):108–110. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brzozowski AM, Pike ACW, Dauter Z, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Engstrom O, Ohman L, Greene GL, Gustafsson JA, Carlquist M. Nature. 1997;389(6652):753–758. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nettles KW, Bruning JB, Gil G, O’Neill EE, Nowak J, Guo Y, Kim Y, DeSombre ER, Dilis R, Hanson RN, Joachimiak A, Greene GL. EMBO Rep. 2007;8(6):563–568. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a Zhou HB, Comninos JS, Stossi F, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. J Med Chem. 2005;48(23):7261–7274. doi: 10.1021/jm0506773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wu YL, Yang XJ, Ren Z, McDonnell DP, Norris JD, Willson TM, Greene GL. Mol Cell. 2005;18(4):413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Pike ACW, Brzozowski AM, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Thorsell AG, Engstrom O, Ljunggren J, Gustafsson JK, Carlquist M. EMBO J. 1999;18(17):4608–4618. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Hsieh RW, Rajan SS, Sharma SK, Guo Y, DeSombre ER, Mrksich M, Greene GL. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(26):17909–17919. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Nguyen A, Top S, Pigeon P, Vessières A, Hillard EA, Plamont M-A, Huché M, Rigamonti C, Jaouen G. Chem--Eur J. 2009;15(3):684–696. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Plazuk D, Vessieres A, Hillard EA, Buriez O, Labbe E, Pigeon P, Plamont MA, Amatore C, Zakrzewski J, Jaouen G. J Med Chem. 2009;52(15):4964–4967. doi: 10.1021/jm900297x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Top S, Vessieres A, Leclercq G, Quivy J, Tang J, Vaissermann J, Huche M, Jaouen G. Chem--Eur J. 2003;9(21):5223–5236. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Gasser G, Ott I, Metzler-Nolte N. J Med Chem. 2011;54(1):3–25. doi: 10.1021/jm100020w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a Endo Y, Iijima T, Yamakoshi Y, Fukasawa H, Miyaura C, Inada M, Kubo A, Itai A. Chem Biol. 2001;8(4):341–355. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Valliant JF, Schaffer P, Stephenson KA, Britten JF. J Org Chem. 2002;67(2):383–387. doi: 10.1021/jo0158229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Beer ML, Lemon J, Valliant JF. J Med Chem. 2010;53(22):8012–8020. doi: 10.1021/jm100758j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Causey PW, Besanger TR, Valliant JF. J Med Chem. 2008;51(9):2833–2844. doi: 10.1021/jm701561e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a Muthyala RS, Sheng SB, Carlson KE, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. J Med Chem. 2003;46(9):1589–1602. doi: 10.1021/jm0204800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kieser KJ, Kim DW, Carlson KE, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. J Med Chem. 2010;53(8):3320–3329. doi: 10.1021/jm100047k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hamann LG, Meyer JH, Ruppar DA, Marschke KB, Lopez FJ, Allegretto EA, Karanewsky DS. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15(5):1463–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a Mull ES, Sattigeri VJ, Rodriguez AL, Katzenellenbogen JA. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10(5):1381–1398. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00406-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ramesh C, Bryant B, Nayak T, Revankar CM, Anderson T, Carlson KE, Katzenellenbogen JA, Sklar LA, Norenberg JP, Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(45):14476–14477. doi: 10.1021/ja066360p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Nettles KW, Bruning JB, Gil G, Nowak J, Sharma SK, Hahm JB, Kulp K, Hochberg RB, Zhou H, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Kim Y, Joachmiak A, Greene GL. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4(4):241–247. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shiau AK, Barstad D, Radek JT, Meyers MJ, Nettles KW, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA, Agard DA, Greene GL. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9(5):359–364. doi: 10.1038/nsb787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhou HB, Sheng SB, Compton DR, Kim Y, Joachimiak A, Sharma S, Carlson KE, Katzenellenbogen BS, Nettles KW, Greene GL, Katzenellenbogen JA. J Med Chem. 2007;50(2):399–403. doi: 10.1021/jm061035y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zhou H-B, Nettles KW, Bruning JB, Kim Y, Joachimiak A, Sharma S, Carlson KE, Stossi F, Katzenellenbogen BS, Greene GL. Chem Biol. 2007;14(6):659–669. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiau AK, Barstad D, Loria PM, Cheng L, Kushner PJ, Agard DA, Greene GL. Cell. 1998;95(7):927–937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu SJ, Zhou B, Yang HY, He YT, Jiang ZX, Kumar S, Wu L, Zhang ZY. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(26):8251–8260. doi: 10.1021/ja711125p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a Pirali T, Busacca S, Beltrami L, Imovilli D, Pagliai F, Miglio G, Massarotti A, Verotta L, Tron GC, Sorba G, Genazzani AA. J Med Chem. 2006;49(17):5372–5376. doi: 10.1021/jm060621o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zarghi A, Rao PNP, Knaus EE. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15(2):1056–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mortensen DS, Rodriguez AL, Carlson KE, Sun J, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. J Med Chem. 2001;44(23):3838–3848. doi: 10.1021/jm010211u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a Katzenellenbogen JA, Johnson HJ, Myers HN. Biochemistry. 1973;12(21):4085–4092. doi: 10.1021/bi00745a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Carlson KE, Choi I, Gee A, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Biochemistry. 1997;36(48):14897–14905. doi: 10.1021/bi971746l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gould JC, Leonard LS, Maness SC, Wagner BL, Conner K, Zacharewski T, Safe S, McDonnell DP, Gaido KW. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;142(1–2):203–214. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McInerney EM, Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW, Katzenellenbogen BS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(19):10069–10073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katzenellenbogen JA. J Med Chem. 2011;54(15):5271–5282. doi: 10.1021/jm200801h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.