Abstract

Aims

To test whether the relations between anxiety sensitivity (AS), a transdiagnostic risk factor, and alcohol problems are explained by chained mediation models, from AS through anxiety or depressive symptoms then drinking motives in an at-risk sample. It was hypothesized that AS would influence alcohol problems through generalized anxiety or depression symptoms and then through negatively-reinforced drinking motives (i.e., drinking to cope with negative affect and drinking to conform).

Design

Cross-sectional single- and chained-mediation models were tested.

Setting

Self-report measures were completed in clinics at Florida State University and the University of Vermont, USA.

Participants

Participants consisted of 523 adult daily cigarette smokers (M age = 37.23, SD = 13.53; 48.6% female).

Measurements

As part of a larger battery of self-report measures, participants completed self-report measures of AS, generalized anxiety, depression, drinking motives, and alcohol problems.

Findings

Chained mediation was found from AS to alcohol problems through generalized anxiety then through drinking to cope with negative affect (B = .04, 90% confidence interval [CI; .004, .10]). Chained mediation was also found from AS to alcohol problems through depression then through drinking to cope with negative affect (B = .11, 90% CI [.05, .21]) and, separately, through socially motivated drinking (B = .05, 90% CI [.003, .11]).

Conclusions

Anxiety sensitivity and alcohol problems are indirectly related through several intervening variables, such as through generalized anxiety or depression and then through drinking to cope with negative affect.

Keywords: anxiety sensitivity, alcohol, generalized anxiety, depression, drinking motives

Alcohol use across the globe is prevalent and often harmful, as evidenced by a recent World Health Organization report indicating that 16.0% of individuals 15 years or older engaged in heavy episodic drinking behavior and that 5.9% of all global deaths (roughly 3.3 million individuals) and 5.1% of the global disease and injury burden were attributable to alcohol consumption [1]. Therefore, identification of risk factors and mechanisms by which these risk factors impact problems with alcohol are imperative. Anxiety sensitivity (AS) is a cognitive risk factor that reflects the extent to which an individual evaluates autonomic arousal as potentially harmful or dangerous [2,3]. AS has been implicated in alcohol problems [4–6]. Individuals with high AS appear to be motivated to use anxiolytic substances, such as alcohol, to temporarily diminish their exaggerated sensitivity to tension and arousal [2,7]. Empirical investigations point toward greater arousal-dampening effects of alcohol for individuals with high AS when compared with low AS, providing evidence of the subjective reinforcement alcohol may provide for individuals with high AS [8–11].

Individuals with high AS report greater problems with alcohol, including increased rates of excessive alcohol consumption [6,12], drinking to legal intoxication more frequently [13], and higher rates of alcohol dependence [7]. Further, longitudinal studies have implicated AS in the development of alcohol problems. For example, Schmidt et al. [5] reported that individuals with high AS were more likely to have developed an AUD after 24 months than were individuals with low AS.

AS may impact alcohol problems through its influence on drinking motives [7,14]. Cooper [15] posited several motivations for drinking including social motives and enhancement of positive affect, referred to as positive reinforcement drinking motives, and coping with negative affect and conforming to social norms, referred to as negative reinforcement drinking motives [14–16]. Whereas the evidence regarding AS and positive reinforcement drinking motives is equivocal [12,17], negative reinforcement drinking motives have been consistently linked to AS [11,12]. Individuals with high AS are more likely to report consuming alcohol to cope with negative affect than individuals with low AS [18,19]. Furthermore, high AS individuals are more likely to report conformity-motivated consumption than are low AS individuals [12,20].

Stewart et al. [12] investigated the mediating effects of drinking motives on the relation between AS and alcohol consumption in a sample of undergraduate students. AS was positively related to increased weekly drinking frequency and yearly excessive drinking. When coping and conformity motives were added as mediators, AS no longer significantly predicted weekly drinking frequency or yearly excessive frequency, suggesting that the relation between AS and alcohol problems is through drinking motives.

Another potential pathway between alcohol problems and AS is through generalized anxiety (i.e., excessive worry) and depression. Extant literature has indicated that AS has an amplifying effect on anxiety and that this effect extends to the cognitive symptoms of depression [3,21–23]. High rates of comorbidity among alcohol use and abuse and anxiety and depression as well as significant associations between anxiety and depression and drinking motives have been well-documented in clinical and community samples [15,20,24–26]. Kushner et al. [4] examined the mediating role of generalized anxiety along with several other anxiety symptom clusters between AS and drinking motives. In this study, generalized anxiety mediated the relation between AS and drinking to cope with negative affect and anxiety.

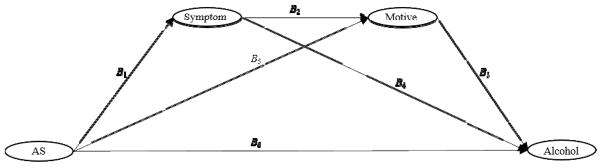

The aforementioned literature indicates the apparent complexity of the relations between AS and alcohol problems. DeMartini and Carey [14] have developed a complex theoretical model to explain these relations, involving several mediational pathways from AS to alcohol problems through anxiety and drinking motives (see Figure 1). AS may impact alcohol problems in a chained fashion through its influence on anxiety and then drinking motives given that AS impacts alcohol problems indirectly through drinking motives [12] and AS impacts drinking motives indirectly through anxiety [4,27]. Although DeMartini and Carey [14] do not address depression in their model, the role of AS as an amplifier of depressive symptoms as well as the relations between AS, depression, and alcohol suggest that depression may act in a similar manner to anxiety in their model [16,22,25].

Figure 1.

Example of chained mediation model from the Anxiety Sensitivity factor to the Alcohol Problems factor. AS = Anxiety Sensitivity. Symptom = Generalized Anxiety or Depression factor. Motive = Drinking Motive factor (Social, Enhancement, Coping, Conformity). Lower-order factors of AS and Alcohol Problems, indicators of AS, Symptoms, Motives, and Alcohol Problems, gender, and residual variances are omitted for clarity.

Most studies examining the mediating effects of AS on alcohol problems are conducted on convenience samples [12,27]. It is important to understand these relations in populations at-risk for alcohol problems. There is broad-based empirical evidence of high co-occurrence between the health behaviors of cigarette smoking and alcohol use problems [28]. Cigarette smokers drink more frequently and in higher quantities relative to non-smokers [29–31]. Notably, alcohol consumption combined with cigarette smoking increases the risk of numerous health conditions such as various types of cancer (e.g, oral, pharyngeal, laryngeal, esophageal, and lung cancer) relative to only smoking, only drinking, or neither smoking or drinking [32,33]. Therefore, addressing the impact of AS on alcohol problems in individuals who smoke cigarettes is important because of the high risk status for alcohol problems in this population.

The Current Study

In the current study, the mechanisms explicating the relations between AS and alcohol problems, as proposed by DeMartini and Carey [14], were examined. It was hypothesized that AS would influence alcohol problems through a chained mediation model [34]. In this model, AS impacts alcohol problems, first through generalized anxiety or depression symptoms, and then through negative reinforcement drinking motives (i.e., coping and conformity). Mediation models were tested for generalized anxiety and depression separately, including each drinking motive (i.e., coping, conformity, social, enhancement) independently. Based on past studies [4,12], it was expected that the chained mediation models would be significant for negative reinforcement drinking motives only. It was hypothesized that these effects would be above and beyond mediation effects from AS to alcohol problems directly through negative reinforcement drinking motives and from AS to alcohol problems through anxiety and depression symptoms.

Methods

Participants

The current study included 523 adults from the community recruited to participate in a randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of a smoking cessation program who reported drinking alcohol. Data was collected at two sites simultaneously (Florida State University [FSU], n = 361, and the University of Vermont [UVM], n = 162). All data used in the present investigation were collected prior to the intervention at the baseline assessment. Eligibility requirements included: a minimum age of 18 years, smoking daily for at least one year, smoking a minimum of 8 cigarettes per day, and reported motivation to quit smoking. The racial/ethnic breakdown of the sample was: 83.6% Caucasian, 6.4% Black/Non-Hispanic, 1.0% Black/Hispanic, 2.5% Hispanic, 1.1% Asian, and 2.5% other (e.g., bi-racial). Gender was relatively evenly distributed (48.6% Female) with ages ranging from 18 to 68 years (M = 37.23, SD = 13.53).

Procedure

Individuals who met the inclusionary criteria after a semi-structured clinical interview (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR; [35]) completed a baseline assessment prior to randomization and smoking cessation treatment. Participants had to be 18 years of age or older, a daily smoker for at least 1 year, smoke a minimum of 8 cigarettes per day, and report a motivation to quit to be eligible for inclusion in the current study. Rates of agreement, calculated using Cohen’s kappa, between clinical interviewers examined for a subset of individuals (12.5% of the sample) were 98%. During the baseline appointment participants completed various self-report measures assessing demographic, psychological, and smoking related constructs. Only the measures relevant to the current study are discussed herein. The study was approved by the university’s IRB, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

MeasuresAnxiety Sensitivity Index–3 (ASI-3)

The ASI-3 [36] is an 18-item self-report measure used to measure fear of anxiety related sensations. Adapted from the ASI [24], the ASI-3 provides a more stable assessment of the three most commonly replicated lower-order anxiety sensitivity dimensions (i.e., cognitive, social, and physical concerns). The ASI-3 demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = .93) in the present study.

Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ)

The PSWQ [37] is a 16-item scale measuring the frequency, intensity, and uncontrollability of worry commonly associated with generalized anxiety disorder. Studies have shown that the PSWQ can distinguish between individuals with and without GAD [38]. The PSWQ demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .83) in the present study.

Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms-Dysphoria scale (IDAS-Dysphoria)

The IDAS [39] is a 64-item questionnaire that measures specific symptom dimensions of mood and anxiety disorders. The IDAS includes symptom subscales as well as two broader composite scales of depression: Dysphoria and General Depression. The 10 items from the Dysphoria scale were used in the current study. Studies have shown that the Dysphoria scale can distinguish between individuals with and without major depressive disorder [40]. The Dysphoria scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = .92) in the present study.

Drinking Motives Questionnaire – Revised (DMQ-R)

The DMQ-R [15] is a 20-item questionnaire of the frequency of drinking for four distinct motivations (i.e., social, enhancement, conformity, and coping). The social (α = .93), enhancement (α = .90), coping (α = .91), and conformity (α = .86) subscales displayed excellent internal consistency in the present study.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)

The AUDIT [41] is a 10-item questionnaire, containing items measuring alcohol consumption and dependence, developed to screen for alcohol use problems in primary care settings. The AUDITd has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for identifying individuals with an Alcohol Use Disorder [42]. The AUDIT demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .83) in the present study.

Data Analytic Strategy

Descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables were first computed and reported. Following this, structural equation models (SEMs) were fit to item-level data, modeled continuously, in Mplus version 7.1 [43], using Full Information Maximum Likelihood to account for missing data. Overall model fit was assessed using the χ2 fit statistic and additional χ2-based fit indices. A nonsignificant χ2 value indicated excellent model fit to the data. Additionally, comparative fit index (CFI) values greater than .90, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values below .08, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) value below .08 indicated adequate fit. An RMSEA 90% confidence interval below .05 indicated that close fit could not be dismissed and a 90% CI containing a value greater than .10 indicated that poor fit could not be dismissed [44–46].

SEMs were first modeled to examine the relations between AS and the mediators and alcohol problems separately to examine direct effects between AS and all other variables. In these and all subsequent analyses, gender, age, and site (i.e., FSU or UVM) were included as control variables on the dependent variables. Gender and age were included as control variables given the relations between these two demographic variables and alcohol problems in prior research [47,48]. The AS factor was modeled as a second-order factor model containing Physical Concerns, Cognitive Concerns, and Social Concerns as first-order factors. The Alcohol Problems factor was also modeled as a second-order factor model, containing Alcohol Dependence and Alcohol Consumption factors as first-order factors. The Generalized Anxiety, Depression, and drinking motives factors were modeled as first-order factors. Mediation models were then examined. Three mediation pathways were examined in each model (see Figure 1). A chained mediation pathway was conducted with Generalized Anxiety and Depression included independently as the first chain of the pathway and each drinking motive (i.e., Coping, Conformity, Social, and Enhancement factors) as the second chain of the pathway (through the paths labeled B1, B2, and B3 in Figure 1; [34]). A single-mediator pathway was examined from AS to Alcohol Problems through each drinking motive factor (through B5 and B3). A single-mediator pathway was also examined from AS to Alcohol Problems through Generalized Anxiety and Depression (through B1 and B4). A direct pathway from AS to Alcohol Problems was also included (B6). Gender, age, and site were included as covariates, with paths to Generalized Anxiety and Depression, drinking motives, and Alcohol Problems.

Mediation models were conducted from a SEM framework as this method mitigates measurement error in constructs, providing unbiased mediation effects [49]. Bias-corrected bootstrapped CIs with 1,000 bootstrap samples to provide consistent and replicable results [50] were used to judge the significance of parameter estimates as this method has demonstrated an optimal balance between power and Type I error [49,50].

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics and correlations for AS, generalized anxiety, depression, drinking motives, alcohol problems, and control variables are provided in Table 1. Although latent variables were used in analyses, scale score means were reported to provide sample statistics comparable to other studies.

Table 1.

Means and Correlations for Anxiety Sensitivity, Generalized Anxiety and Depression Symptoms, Drinking Motives, and Alcohol Use Disorders Symptoms

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Mean (or %) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anxiety Sensitivity | -- | .55*** | .61*** | .27*** | .26*** | .17*** | .12** | .19*** | .10* | −.06 | 15.23 | 12.34 |

| 2. Generalized Anxiety | -- | .70*** | .23*** | .16*** | .09* | .02 | .09* | .29*** | −.10* | 43.75 | 14.34 | |

| 3. Depression | -- | .36*** | .24*** | .22*** | .15*** | .21*** | .14*** | −.14*** | 19.27 | 7.94 | ||

| 4. Cope Motive | -- | .54*** | .58*** | .64*** | .57*** | −.03 | −.17*** | 12.50 | 6.04 | |||

| 5. Conform Motive | -- | .44*** | .43*** | .28*** | −.12* | −.13** | 11.43 | 5.73 | ||||

| 6. Social Motive | -- | .79*** | .51*** | −.10* | −.39*** | 8.52 | 4.63 | |||||

| 7. Enhance Motive | -- | .59*** | −.15*** | −.36*** | 6.35 | 2.77 | ||||||

| 8. Alcohol Problems | -- | −.12** | −.31*** | 6.25 | 5.92 | |||||||

| 9. Gender (% Male) | -- | .08 | 51.4 | |||||||||

| 10. Age | -- | 37.23 | 13.53 |

Note. Ns for means/correlations range from 473 to 523. Anxiety Sensitivity measured by Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (18 items). Generalized Anxiety measured by Penn State Worry Questionnaire (16 items). Depression measured Dysphoria scale of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (10 items). Social, Enhance, Cope, and Conform Motives measured by the Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (5 items each). Alcohol Problems measured by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (10 items).

p ≤ .001,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .05.

Direct Effects of AS on Anxiety and Depression, Drinking Motives, and Alcohol Problems

An SEM examining the direct effects of AS (controlling for gender, age, and site) on Generalized Anxiety and Depression provided adequate fit to the data (see Table 2). AS was associated with Generalized Anxiety and Depression (see top panel of Table 3). Further, 37% of the variance in Generalized Anxiety and 30% of the variance in Depression were accounted for in this model. An SEM examining the direct effects of AS and on the drinking motives factors, controlling for gender, age, and site, provided adequate fit to the data. AS was associated with Coping, Conformity, and Social, but not Enhancement (see middle panel of Table 3). Further, 9–18% of the variance in the drinking motives factors were accounted for in this model. An SEM examining the direct effects of AS, controlling for gender, age, and site, on Alcohol Problems provided adequate fit to the data. AS was associated with Alcohol Problems (see bottom pane of Table 3) and this model accounted for 24% of the variance in Alcohol Problems.1

Table 2.

Model Fit Indices for Structural Equation and Chained Mediation Models of Anxiety Sensitivity on Alcohol Problems

| Anxiety Sensitivity Direct Effects Models | χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA [90% CI] | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Anxiety and Depression Model | 2375.22 | 1008 | .91 | .05 [.05, .05] | .05 |

| Drinking Motives Model | 2201.68 | 754 | .90 | .06 [.06, .06] | .07 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder Symptoms Model | 1106.47 | 424 | .91 | .06 [.05, .06] | .07 |

|

| |||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity Mediation Models | |||||

| Generalized Anxiety Factor Models | |||||

|

| |||||

| Coping Drinking Motives Factor | 2586.06 | 1243 | .92 | .05 [.04, .05] | .06 |

| Conformity Drinking Motives Factor | 2488.63 | 1243 | .93 | .04 [.04, .05] | .06 |

| Social Drinking Motives Factor | 2372.33 | 1243 | .93 | .04 [.04, .04] | .06 |

| Enhancement Drinking Motives Factor | 2613.49 | 1243 | .92 | .05 [.04, .05] | .05 |

|

| |||||

| Depression Factor Models | |||||

| Coping Drinking Motives Factor | 2236.81 | 967 | .91 | .05 [.05, .05] | .06 |

| Conformity Drinking Motives Factor | 2142.60 | 967 | .91 | .05 [.05, .05] | .07 |

| Social Drinking Motives Factor | 2014.49 | 967 | .92 | .05 [.04, .05] | .07 |

| Enhancement Drinking Motives Factor | 2263.55 | 967 | .90 | .05 [.05, .05] | .07 |

Note. CFI = Comparative fit index. RMSEA = Root mean square error of approximation. CI = Confidence Interval. SRMR = Square Root Mean Square Residual.

Table 3.

Direct Effects Models for Anxiety Sensitivity Predicting Generalized Anxiety and Depression Symptoms, Drinking Motives, and Alcohol Problems

| B | LL | UL | B | LL | UL | B | LL | UL | B | LL | UL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models | Generalized Anxiety | Depression | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity | 1.07 | .87 | 1.29 | 1.12 | .91 | 1.36 | ||||||

| Gender | .39 | .26 | .53 | .16 | .04 | .31 | ||||||

| Age | −.01 | −.01 | .001 | −.01 | −.01 | −.001 | ||||||

| Site | −.12 | −.28 | .03 | −.09 | −.25 | .09 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Coping Drinking Motives | ConformDrinking Motives | SocialDrinking Motives | Enhancement Drinking Motives | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity | .42 | .23 | .62 | .22 | .11 | .35 | .32 | .11 | .56 | .15 | −.09 | .39 |

| Gender | −.05 | −.22 | .09 | −.10 | −.19 | −.02 | −.25 | −.45 | −.04 | −.30 | −.55 | −.06 |

| Age | −.004 | −.01 | .002 | −.002 | −.01 | .001 | −.03 | −.04 | −.02 | −.03 | −.04 | −.02 |

| Site | .12 | −.08 | .30 | .04 | −.04 | .14 | .03 | −.21 | .29 | .20 | −.09 | .50 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Alcohol Problems | ||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity | .14 | .02 | .29 | |||||||||

| Gender | −.19 | −.30 | −.09 | |||||||||

| Age | −.02 | −.03 | −.01 | |||||||||

| Site | .07 | −.07 | .19 | |||||||||

Chained Mediation Models between AS and Alcohol Problems including Generalized Anxiety

Pathway estimates and CIs for the mediation models including Generalized Anxiety are provided in Table 4. All drinking motives were significantly associated with Alcohol Problems. AS was significantly associated with Alcohol Problems across all drinking motives models also, with the exception of the Social model. Across all drinking motives, with the exception of Enhancement, a single-mediator effect was found for the relation between AS and Alcohol Problems through drinking motives. There was a significant chained mediation effect from AS through Generalized Anxiety then through Coping to Alcohol Problems.

Table 4.

Chained Mediation Models of Anxiety Sensitivity, Generalized Anxiety and Depression Symptoms, and Drinking Motives Predicting Alcohol Problems

| Coping Drinking Motives | ConformDrinking Motives | SocialDrinking Motives | Enhancement Drinking Motives | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Models | B | LL | UL | B | LL | UL | B | LL | UL | B | LL | UL |

| Anxiety Models | ||||||||||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity | .13 | .03 | .29 | .14 | .004 | .33 | .13 | −.01 | .31 | .18 | .04 | .36 |

| Generalized Anxiety | −.05 | −.12 | .00 | −.04 | −.12 | .03 | −.03 | −.12 | .05 | −.02 | −.10 | .06 |

| Drinking Motive | .31 | .21 | .43 | .31 | .07 | .54 | .24 | .17 | .32 | .26 | .19 | .34 |

| Chained Med | .04 | .004 | .10 | .01 | −.01 | .03 | −.01 | −.06 | .02 | −.02 | −.08 | .03 |

| AS-DM Med | .09 | .02 | .18 | .06 | .02 | .13 | .10 | .03 | .19 | .06 | −.01 | .17 |

| AS-Anxiety Med | −.05 | −.13 | .00 | −.04 | −.14 | .04 | −.03 | −.13 | .05 | −.02 | −.11 | .06 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Depression Models | ||||||||||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity | .11 | −.01 | .30 | .09 | −.05 | .28 | .13 | −.03 | .31 | .16 | .02 | .35 |

| Depression | −.03 | −.13 | .04 | .01 | −.08 | .12 | −.02 | −.13 | .08 | −.001 | −.10 | .10 |

| Drinking Motive | .31 | .21 | .44 | .31 | .07 | .53 | .24 | .17 | .33 | .26 | .19 | .34 |

| Chained Med | .11 | .05 | .21 | .01 | −.01 | .06 | .05 | .003 | .11 | .04 | −.02 | .11 |

| AS-DM Med | .03 | −.06 | .12 | .06 | .01 | .13 | .03 | −.04 | .12 | .002 | −.09 | .10 |

| AS-Depression Med | −.04 | −.16 | .05 | .01 | −.10 | .14 | −.03 | −.15 | .10 | −.002 | −.12 | .12 |

Note. LL = Lower limit of 95% confidence interval. UL = Upper limit of 95% confidence interval. AS = Anxiety Sensitivity. DM = Drinking Motive. Chained Med = Chained Mediation pathway from AS to Alcohol Problems through Symptoms and then Drinking Motives. AS-DM Med = Mediation pathway from AS to Alcohol Problems through Drinking Motives. AS-Anxiety/Depression Med = Mediation pathway from AS to Alcohol Problems through Anxiety/Depression. Significant effects (Those whose confidence interval does not include zero) are in bold. Covariates included gender, age, and site.

Chained Mediation Models between AS and Alcohol Problems including Depression

In the mediation models containing Depression (see Table 4), all drinking motives were significantly associated with Alcohol Problems. AS remained significantly associated with Alcohol Problems only in the model containing Enhancement. There were no significant mediation effects in the model containing Enhancement. There was a significant single-mediation effect from AS to Alcohol Problems through Conformity. As hypothesized, there was a significant chained mediation effect from AS through Depression then through Coping to Alcohol Problems. Unexpectedly, there was also a significant chained mediation effect from AS through Depression then through Social to Alcohol Problems. 2

Discussion

As hypothesized, the relation between AS and alcohol problems was explained by a chained mediation process through both generalized anxiety and depression when drinking to cope with negative emotions was included. Although no previous studies have tested this full mediation model, direct effects of AS and mood and anxiety symptoms on drinking to cope and alcohol problems have been reported [4,19,26,27]. Indirect effects have also been reported from AS to coping through generalized anxiety and from AS to alcohol problems through drinking to cope [4,12,27]. Therefore, these findings provide support for the chained mediation model as proposed by DeMartini and Carey [14] as well as extend this model to include depression as a mediator between AS and coping motives.

A chained mediation effect was also found for depression when social drinking motives were included in the model. The presence of this effect for depression but not for generalized anxiety might be due to the difference in positive affect separating anxiety and depression. Whereas high negative affect is a defining feature of depression and anxiety, low positive affect is a defining feature of depression only [52,53]. Further, low positive affect has been linked to positively-reinforced drinking motives [16], suggesting that individuals with depressive symptoms might be more likely to drink because of positive reinforcement drinking motives, such as social drinking motives, associated with increasing positive affect. Social drinking motives may be especially relevant as individuals high in depressive symptoms may be using alcohol to enhance social rewards they may be missing due to the low overall social engagement that is symptomatic of depression [39]. Therefore, individuals with elevated AS and depression may adopt positively- and negatively-reinforced drinking motives leading to the development of alcohol problems.

When mediation was present in the models containing depression, the effect was primarily through the proposed chained mediation model, with the exception of the model including conformity drinking motives, which directly mediated the relation between AS and alcohol problems. For generalized anxiety, however, pathways from AS to alcohol problems were present directly through drinking motives across all drinking motives models except social drinking motives (although this effect was in the expected direction). The reason for this discrepancy is likely because of the similar relation depression and generalized anxiety share with AS and the stronger relation depression shares with alcohol problems, in the current study (as evidenced by the correlations between the scales), as well as in prior research [54]. Therefore, depression appears to better capture the relation between AS and drinking motives more fully than including generalized anxiety as a mediator.

There are several limitations to consider. Models for anxiety and depression as well as models including distinct drinking motives were examined separately to limit the potential influence of multicollinearity on the results. Therefore it is possible that the overlap among anxiety and depression or among the drinking motives may account for the current findings. However, the specificity of the findings, especially in that chained mediation for depression was found for social drinking motives whereas chained mediation for anxiety was not, limit the concern that these findings are more broadly related to the overlap among anxiety and depression or among the drinking motives. Data for this study were collected concurrently, meaning that causality cannot be determined. However, the pathways in this model have been proposed theoretically as well as detected empirically [4,12,14]. Shared method variance is a concern because self-report measures were used across all facets of the study, suggesting the need for replication including other assessment methods such as diagnostic report or physiological methods of assessing AS and anxiety. Finally, the current sample comprised daily cigarette smokers, which may influence the generalizability of the current results, especially given the complicated relations between anxiety and depression and smoking behavior [55]. Future studies should replicate these findings in other populations.

Overall, the current study provides support for the chained mediation model of AS impacting alcohol problems through anxiety, depression and coping drinking motives [14] in a sample of individuals at-risk for drinking problems because of their status as cigarette smokers. As posited by DeMartini and Carey [14], the pathway between AS and alcohol problems was a function of several intervening risk and motivational factors. The present study has potential clinical implications. Namely, given the chained mediation pathways from AS to alcohol problems, interventions targeting several intervening risk and motivational factors may prove more effective in reducing alcohol problems, especially in individuals with elevated levels of AS.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by NIH grant R01-MH076629. NIMH did not have influence over the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report or the decision to submit this article for publication.

Footnotes

Several empirically supported residual variances were allowed to covary within models to improve model fit. These included all reverse-scored items on the PSWQ (i.e., items 1, 3, 8, 10, and 11) and items 1 and 3 on the AUDIT.

Given that this sample consisted primarily of cigarette smokers, all analyses were also conducted including item 2 from the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), which assesses cigarettes smoked per day [51]. There was one difference between the reported results and the results including FTND item 2. The effect of AS was not significant in the model including AS, Depression, and Enhancement drinking motives (B = .17, 90% CI [−.001, .37]). However, 38 individuals did not have FTND data available, and were therefore not included in the analyses including FTND as a control variable. Therefore, analyses without including FTND as a covariate was presented in the manuscript.

Declaration of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health-2014. World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiss S. Expectancy model of fear, anxiety, and panic. Clinical Psychology Review. 1991;11:141–153. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiss S, McNally RJ. Expectancy model of fear. Theoretical Issues in Behavior Therapy. 1985:107–121. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kushner MG, Thuras P, Abrams K, Brekke M, Stritar L. Anxiety mediates the association between anxiety sensitivity and coping-related drinking motives in alcoholism treatment patients. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:869–885. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt NB, Buckner JD, Keough ME. Anxiety Sensitivity as a prospective predictor of alcohol Use Disorders. Behavior Modification. 2007;31:202–219. doi: 10.1177/0145445506297019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart SH, Peterson JB, Pihl RO. Anxiety sensitivity and self-reported alcohol consumption rates in university women. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1995;9:283–292. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart SH, Samoluk SB, MacDonald AB. Anxiety sensitivity and substance use and abuse. In: Taylor S, editor. Anxiety sensitivity: Theory, research, and treatment of the fear of anxiety. Malwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. pp. 287–319. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis BA, Vogeltanz-Holm ND. The effects of alcohol and anxiousness on physiological and subjective responses to a social stressor in women. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:529–545. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDonald AB, Baker JM, Stewart SH, Skinner M. Effects of alcohol on the response to hyperventilation of participants high and low in anxiety sensitivity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1656–1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacDonald AB, Stewart SH, Hutson R, Rhyno E, Loughlin HL. The roles of alcohol and alcohol expectancy in the dampening of responses to hyperventilation among high anxiety sensitive young adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:841–867. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zack M, Poulos CX, Aramakis VB, Khamba BK, MacLeod CM. Effects of drink-stress sequence and gender on alcohol stress response dampening in high and low anxiety sensitive drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:411–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH. Negative-reinforcement drinking motives mediate the relation between anxiety sensitivity and increased drinking behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:157–171. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conrod PJ, Stewart SH, Pihl RO. Validation of a measure of excessive drinking: Frequency per year that BAL exceeds 0.08% Substance Use and Misuse. 1997;32:587–607. doi: 10.3109/10826089709027314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeMartini KS, Carey KB. The role of anxiety sensitivity and drinking motives in predicting alcohol use: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawyer SR, Karg RS, Murphy JG, McGlynn FD. Heavy drinking among college students is influenced by anxiety sensitivity, gender, and contexts for alcohol use. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16:165–173. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conrod PJ, Pihl RO, Vassileva J. Differential sensitivity to alcohol reinforcement in groups of men at risk for distinct alcoholism subtypes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:585–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb04297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart SH, Karp J, Pihl RO, Peterson RA. Anxiety sensitivity and self-reported reasons for drug use. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:223–240. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart SH, Zeitlin SB. Anxiety sensitivity and alcohol use motives. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1995;9:229–240. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox BJ, Enns MW, Freeman P, Walker JR. Anxiety sensitivity and major depression: Examination of affective state dependence. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2001;39:1349–1356. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox BJ, Enns MW, Taylor S. The effect of rumination as a mediator of elevated anxiety sensitivity in major depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:525–534. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, Smit JH, van den Brink W, Veltman DJ, Beekman ATF, et al. Comorbidity and risk indicators for alcohol use disorders among persons with anxiety and/or depressive disorders: Findings from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;131:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou P, Dufour MC, Compton W, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope and alcohol use and abuse in unipolar depression: A 10-year model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH. The relations of anxiety sensitivity, experiential avoidance, and alexithymic coping to young adults’ motivations for drinking. Behavior Modification. 2002;26:274–296. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026002007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bobo JK. Nicotine dependence and alcoholism epidemiology and treatment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1989;21:323–329. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1989.10472174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anthony JC, Echeagaray-Wagner F. Epidemiologic analysis of alcohol and tobacco use. Alcohol Research and Health. 2000;24:201–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiolero A, Wietlisbach V, Ruffieux C, Paccaud F, Cornuz J. Clustering of risk behaviors with cigarette consumption: A population-based survey. Preventive Medicine. 2006;42:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kahler CW, Borland R, Hyland A, McKee SA, Thompson ME, Cummings KM. Alcohol consumption and quitting smoking in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;100:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Winn DM, Austin DF, Greenberg RS, Preston-Martin S, et al. Smoking and drinking in relation to oral and pharyngeal cancer. Cancer Research. 1988;48:3282–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sees KL, Clark HW. When to begin smoking cessation in substance-abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10:189–195. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor AB, MacKinnon DP, Tein J. Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;11:241–269. [Google Scholar]

- 35.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Research Version (SCID-I) New York, NY: Biometrics Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ, Deacon B, Heimberg RG, Ledley DR, et al. Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: Development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:176–188. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1990;28:487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown TA, Antony MM, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the Penn State Worry Questinnaire in a clinical anxiety disorders sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1992;30:33–37. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(92)90093-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watson D, O’Hara MW, Simms LJ, Kotov R, Chmielewski M, McDade-Montez EA, et al. Development and validation of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS) Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:253–268. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watson D, O’Hara MW, Chmielewski M, McDade-Montez EA, Koffel E, Naragon K, Stuart S. Further validation of the IDAS: Evidence of convergent, discriminant, criterion, and incremental validity. Psychological Assessment. 2008;20:248–289. doi: 10.1037/a0012570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): A review of recent research. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:272–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Author; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilsnack RW, Vogeltanz-Holm ND, Wilsnack SC, Harris TR. Gender differences in alcohol consumption and adverse drinking consequences: Cross-cultural patterns. Addiction. 2000;95:251–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95225112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levenson MR, Aldwin CM, Spiro A., III Age, cohort and period effects on alcohol consumption and problem drinking: Findings from the normative aging study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1998;59:712–722. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheung GW, Lau RS. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;11:296–325. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström K. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watson D, Clark LA, Carey G. Positive and negative affectivity and their relation to anxiety and depressive disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:346–353. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morrell HE, Cohen LM. Cigarette smoking, anxiety, and depression. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2006;28:281–295. [Google Scholar]