Abstract

Assembly of amyloid proteins into aggregates requires the ordering of the monomers in oligomers and especially in such highly organized structures as fibrils. This ordering is accompanied by structural transitions leading to the formation of ordered β-structural motifs in proteins and peptides lacking secondary structures. To characterize the effect of the monomers arrangements on the aggregation process at various stages, we performed comparative studies of the yeast prion protein Sup35 heptapeptide (GNNQQNY) along with its dimeric form CGNNQQNY-(d-Pro)-G-GNNQQNY. The (d-Pro)-G linker in this construct is capable of adopting a β-turn, facilitating the assembly of the dimer into the dimeric antiparallel hairpin structure (AP-hairpin). We applied Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) techniques to follow peptide-peptide interactions at the single molecule level, to visualize the morphology of aggregates formed by both constructs, thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence to follow the aggregation kinetics, and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to characterize the secondary structure of the constructs. The ThT fluorescence data showed that the AP-hairpin aggregation kinetics is insensitive to the external environment such as ionic strength and pH contrary to the monomers the kinetics of which depends dramatically on the ionic strength and pH. The AFM topographic imaging revealed that AP--hairpins primarily assemble into globular aggregates, whereas linear fibrils are primary assemblies of the monomers suggesting that both constructs follow different aggregation pathways during the self-assembly. These morphological differences are in line with the AFM force spectroscopy experiments and CD spectroscopy measurements, suggesting that the AP-hairpin is structurally rigid regardless of changes of environmental factors.

Keywords: Protein aggregation, amyloids, oligomer self-assembly, AFM, nanoimaging, force spectroscopy, neurodegenerative diseases

1. Introduction

Yeast Prion Protein, Sup35p, has been used as a model for the prion disease phenomenon, particularly for understanding of the structural aspects of such diseases [1, 2]. Sup35p misfolding and aggregation mimic those associated with mammalian prion diseases [1, 3]. Therefore, the understanding of the transient states of the misfolded Sup35p will pave the way for development of efficient diagnostics and remedies for the disease [4, 5]. The N-terminal domain of the protein plays an important role in the aggregation of the entire Sup35 prion. More specifically, a seven amino acid sequence that spans from residues 7 to 13, GNNQQNY, has a significant involvement in aggregation of the whole protein [1, 2, 6–12]. In fact, the addition of this peptide seeded aggregation of the whole protein, dramatically accelerating the aggregation process.

The solid state NMR structural studies emerged to suggest strongly the origin of polymorphic variation in amyloid fibrils [11]. Differences in the packing of these β-sheets, originating from differences in the side-chain packing, register or topology of β-sheets, may explain morphological variants of fibrillar structure. Solid-state NMR studies clearly showed the coexistence of three distinct conformations of the GNNQQNY peptide within a single fibril. Different packing arrangements of peptides within a fibril were proposed to be responsible for the observed differences in NMR chemical shifts. These coexisting conformations differ by the degree of local secondary structure (α-helical versus β-sheet) [11]. This structural variability is in line with the crystallographic studies where eight classes of so-called steric zippers have been identified [13]. Such variation involves mainly orientation of peptides and β-sheets with respect to each other.

The structure of the peptides and their arrangements within assemblies can depend on the aggregate size. In crystals, the Sup35 heptapeptide forms a steric zipper arrangement between two β-sheets with the parallel orientation of monomers within the sheets [3]. However, the monomer arrangement can be different if the aggregates are small and interact with the environment. This assumption is supported by a recent publication [14], in which molecular dynamics (MD)1 simulation of the Sup35 octapeptide was performed. The authors showed that the single β-sheet structure taken from the crystallographic structure depends on a number of factors including the aggregate size. The experiment revealed that an aggregate can disintegrate into smaller-sized oligomers or the edge peptides can dissociate sequentially. The authors also assumed that a heterogeneous mixture of oligomers of different sizes exist prior to the formation of the critical nucleus. The pH and ionic strength of the surrounding solution can also play a role which was confirmed by our recent AFM imaging and force spectroscopy studies [15].

These data suggest that assembly of monomeric unit in the aggregates and their secondary structure can define the aggregate morphology. To test this hypothesis, we performed comparative studies of heptapeptide Sup35 peptide (monomer) and its covalent dimeric form in which two monomers are covalently attached to each other in the tail-to-head orientation via the (d-Pro)G dipeptide. The latter according to NMR and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy studies [16] has the β-turn structure forcing the entire dimer to adopt antiparallel geometry (AP-hairpin). We show here that although both constructs are capable of self-assembly into amyloid aggregates, the prearrangement of the monomers into dimers changes dramatically the AP-hairpin conformational properties limiting the aggregation propensities of the AP-hairpin compared to the monomer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

The peptides NH3+-Cys-Gly-Asn-Asn-Gln-Gln-Asn-Tyr-COOH− (CGNNQQNY, Monomer) and the hairpin peptide NH3+-Cys-Gly-Asn-Asn-Gln-Gln-Asn-Tyr-DPro-Gly-Gly-Asn-Asn-Gln-Gln-Asn-Tyr-COOH− (CGNNQQNY(d-Pro)GGNNQQNY, AP dimer) were synthesized by Peptide 2.0, Inc. (Chantilly, VA). Synthesized peptides were purified by VYDAC-C18 reverse-phase HPLC, and their molecular weight was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

The aminopropyl silatrane (APS) was used at a concentration of 167 μM for 30 minutes for mica surface functionalization as described in ref. [17]. The 1.67 mM stock solution of NHS-PEG-MAL (N-hydroxysuccinimide-polyethylene glycol-maleimide, MW=3,400 g/mol), purchased from Laysan Bio, Inc. (Arab, AL), was prepared in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO) and stored at −20°C. The 10 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) hydrochloride (Hampton Research Inc.) was prepared in water, and was added to peptide solution and incubated for 10 minutes prior to deposition on the PEGylated substrates. TCEP was useful for reducing any disulfide bonds that may have formed between two peptides to make the thiol group available to the substrate.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1. Aggregation studies using ThT fluoresence

The extent of peptide aggregation was followed by characteristic changes in Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence. First, the lyophilized peptide powder was dissolved in either water or buffer in an initial volume of 100 μl. The initial concentration was measured using NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE), by detecting the absorbance of the tyrosine residue at 274 nm, and using an extinction coefficient of 1405 L·mol−1·cm−1 for tyrosine. Then, the peptide solution was diluted down to 500 μM, using either water or a buffer as a solvent [1, 2]. For the ThT fluorescence assay, 2 μL aliquots from the samples were withdrawn periodically and added to 590 μL of 5 μM ThT solution. Fluorescence intensity was measured on a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorimeter (Varian Inc. Palo Alto, CA) at 485 nm while exciting at 450 nm. Each reported value is an average of 15 values of fluorescence intensity after subtracting out the fluorescence contribution from free ThT.

Initial fluorescence readings were taken immediately after the solution was prepared. Stirring the solution at intervals was done in order to accelerate the aggregation process. Magnetic stir bars were placed into the peptide solutions, and the samples were stirred on a magnetic stirrer (Hanna Instruments, Smithfield, RI) for 20 minutes once every two hours. The ThT data were fitted with the following sigmoidal equation:

| (1) |

with T0 being a time of 0 hours, Tf being the final time, T1/2 the half-time of aggregation, T the time point being measured, and Smax being the maximum fluorescence attained in the data set.

The working buffer solutions were prepared at four different pHs: pH 2.0 (HCl/KCl), pH 3.7 (sodium acetate/acetic acid), pH 5.6 (sodium acetate/acetic acid), and pH 7 (HEPES). A fifth buffer was used occasionally at pH 9.8 (sodium carbonate/sodium bicarbonate). The ionic strength was adjusted by adding NaCl.

2.2.2. AFM topographic imaging

At the plateau levels of ThT fluorescence, 2 μl of the 500 μM aggregation mixture was deposited on the mica and allowed to sit for 2 minutes, followed by the addition of 8 μl of distilled water, which was then allowed to sit for 2 minutes. The samples were then dried by 2 minutes of spin coating at 2000 rpm using a Model WS-400BZ-6NPP/LITE spin coater (Laurell Technologies Corporation, North Wales, PA)

Images were acquired in air using a MultiMode SPM NanoScope V Multimode 8 system (Bruker Nano, Santa Barbara, CA) operating in peak force mode. Silicon nitride (Si3N4) AFM probe tips (MSNL – Bruker, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) with nominal spring constants of 0.6 N/m were used for peak force imaging. Image analysis was done using Femtoscan Online (Advanced Technologies Center, Moscow, Russia). The aggregates in were analyzed manually by counting elongated fibrils and globular oligomers after subtracting anything in the background that was less than 1 nm in height..

2.2.3. AFM Force Spectroscopy

Freshly cleaved mica (Asheville-Schoonmaker Mica Co., Newport News, VA, USA) surfaces were treated with amino-propyl-silatrane (APS) for 30 min according to previously reported protocol [17] followed by rinsing with water and drying with argon gas flow. The APS modified mica surfaces were treated with 167 μM NHS-PEG-MAL in DMSO for 3 h followed by rinsing with DMSO to remove non-bound NHS-PEG-MAL, rinsing with water, and drying with argon gas flow. Maleimide-functionalized mica was incubated for 1 h in 190 nM of peptide solution (HEPES buffer, pH 7.0). Prior to immobilization of peptide, the peptide solution was treated with 0.25 mM TCEP hydrochloride for 10 min in pH 7.0 buffer to reduce any disulfide bonds. After washing with HEPES (pH 7.0, 10 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl) buffer, unreacted maleimide was quenched with 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol for 10 min followed by rinsing with HEPES pH 7.0 buffer.

Silicon nitride (Si3N4) AFM probe tips (MLCT – Bruker, Santa Barbara, CA) were washed in ethanol by immersion for 30 min and then activated by UV treatment for 30 min. The activated probe tips were treated with APS for 30 minutes. The APS modified probe tips were then treated with 167 μM NHS-PEG-MAL for 3 h followed by rinsing with DMSO, and thorough rinsing with double distilled water. Maleimide-functionalized AFM probes were incubated for 1 h in 190 nM of peptide solution (HEPES buffer, pH 7.0). After washing with HEPES (pH 7.0, 10 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl) buffer, unreacted maleimides on the probe were quenched with 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol for 10 min followed by rinsing with HEPES pH 7.0 buffer.

Force–distance measurements were performed in pH 5.6 (Ionic Strength = 11 mM) buffer at room temperature with the Force Robot 300 (JPK Instruments, Berlin, Germany). The ramp size was 200 nm with various loading rates. An application force was kept at a low value (100 pN). Silicon nitride cantilevers with nominal values of spring constants in the range of 0.04–0.07 N/m were used. The approach velocity was kept at 500 nm/s while the retraction velocity was varied between 100 nm/s and 2,000 nm/s, and the corresponding values of apparent loading rates were between 102 and 105,000 pN/s. The most probable rupture force was obtained from the probability function fit [18] of the force distribution compiled in a statistical histogram. Data analysis in dynamic force spectroscopy was performed as described in refs. [19–22].

2.2.4. Dynamic Force Spectroscopy

The force curves were analyzed using wormlike chain (WLC) approximation describing behavior of polymer linkers under applied external force and the Igor Pro 6.04 software package provided by the manufacturer [15, 23, 24]. The contour lengths and persistence lengths of the unbinding of peptides were determined from the WLC fit of experimental force–distance curves. The unbinding events where interactions between peptides are ruptured upon tip retraction appear at a certain distance in the experimental force–distance curves defined by the length of the flexible PEG linker. The analysis of the unbinding events included fitting the part of the force-distance curve with WLC model. The fit provided contour length and persistence length of the linkers.

Each force curve was fitted using the WLC model. The approach velocity was kept at 500 nm/s while the retraction velocity was varied between 80 nm/s and 6,000 nm/s. At each retraction velocity value, 1,000 to 6,000 force curves are obtained. The cantilever-linker-molecule system possesses an apparent spring constant (kc) due to molecular coupling. The apparent loading rate (r) defined by the slope of the force curve immediately before the position of the rupture point on the force curve was determined using the following equation [7, 23]:

| (2) |

where Fp = kBT/Lp, kc is the cantilever spring constant (pN/nm), v is tip velocity (nm/s), Lc and Lp are contour length (nm) and persistence length (nm), respectively, which are parameters of WLC fitting, F is rupture force (pN), and r is loading rate (pN/s).

All of the forces at each apparent rate were put together. The apparent loading rates were between 100 and 100,000 pN/s, which correspond to pulling velocities of 80 to 6,000 nm/s. The range of loading rates were divided into seven parts, where the force was obtained using the probability function through the following equation [25]:

| (3) |

where koff(0) is the off-rate constant of the complex at zero force, xβ is the distance of the transition state to bound state, kB is Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature, r is the loading rate, that is dF/dt. The probability density of rupture force, p(F) was calculated according to equation 2 in the measured force histogram.

2.2.5 Circular Dichroism

Circular dichroism (CD) was used to characterize the secondary structure of oligomers and compare their structure with monomers and non-nuclei oligomers. In these experiments, 1 mg of peptide was dissolved in 20 μl of 0.05 M NaOH, and the solution was allowed to stand for 1 minute at room temperature. 180 μl of water was then added so that the final peptide concentration was 5 mg/ml in 5 mM NaOH. The peptide is unstable in the NaOH solution, and was used within an hour. When measurements were made at pH 7.0, 20 μl of 100 mM phosphate buffer was added in addition to 160 μl of water, which made the protein more stable in solution. The CD measurements were performed on a Jasco J-815 (Jasco Inc., Easton, MD) and each measurement was done at least in triplicate between the wavelengths of 190 to 260 nm. Path length was 0.2 mm, scan speed 20 nm/min, bandwidth 1 nm and response time 16 sec. Final peptide concentration for most measurements was 0.5 mg/ml unless indicated otherwise. Buffer concentration was 10 mM. Spectra of buffer or other additives were subtracted when necessary.

3. Results

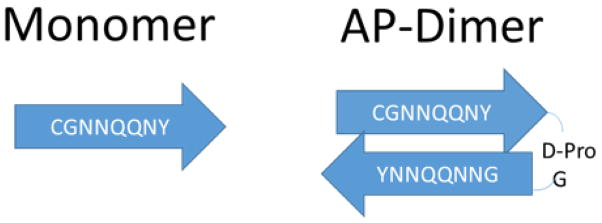

In order to evaluate the role of the orientation of the monomers in peptide self-assembly, a dimeric design in which two Sup35 monomers were connected in antiparallel orientation via the (d-Pro)G spacer was synthesized and analyzed, as shown in Figure 1. This construct was made in order to potentially have the completely antiparallel orientation of the monomers. The (d-Pro)G spacer was selected because according to refs. [16, 26] it adopts a β-turn geometry, with the results of NMR and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopies confirming the β-turn structure of this region [19]. Therefore, the oligopeptide with the sequence CGNNQQNY (d-Pro)G YNNQQNNG is, in principle, capable of forming a β-hairpin structure with antiparallel orientation of the monomers termed AP-hairpin (where AP stays for antiparallel).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the structures of sequences for both peptides: monomers and AP--hairpins. Arrows indicate the N-to-C direction of the sequences with no relation to their secondary structure.

3.1 Aggregation Kinetics

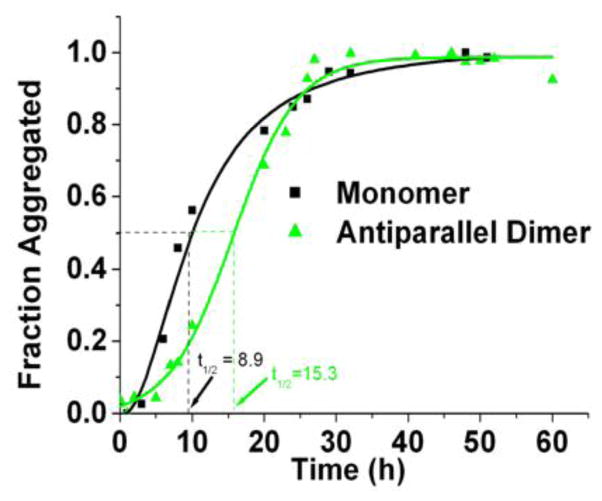

First, the aggregation kinetics were studied with the use of ThT fluorescence. The results of the aggregation analysis of the monomer and the AP-hairpin at pH 5.6, and an ionic strength of 10 mM are shown in Figure 2. This analysis revealed that the aggregation kinetics at pH 5.6 was slower for AP-hairpin (green line) compared with the monomer. The aggregation half-time values were 8.9 ± 2.6 h and 15.3 ± 1.0 h for the monomer and the AP-hairpin, respectively. Non-normalized data are shown in Fig. S2A.

Figure 2.

Normalized time-dependent thioflavin (ThT) fluorescence plots. The aggregation kinetics of the monomer (black square), pH 5.6 and AP-hairpin (green). Aggregation half-times are indicated by the dashed lines that are color-coded to match their respective peptide, as they intercept with the x-axis.

Since the pH used in this original set of experiments was close to the peptide’s isoelectric points, the next step was to examine the effects of pH and ionic strength on the aggregation kinetics. The effect of pH was tested on the AP-hairpin by performing the studies at pH 2.0 in a solution containing also potassium chloride and hydrochloric acid, with the ionic strength remaining constant at 10 mM. Previously, it was shown that pH 5.6 and pH 2.0 correspond to the conditions at which the monomers had the shortest and longest aggregation half-times, 8.9 ± 2.6 h, and 85.3 ± 11.1 h respectively [15]. The experiments for the AP-hairpin were repeated five times at each pH and the averaged results as kinetic plots are shown in Figure S1. This analysis showed the aggregation half-time of the AP-hairpin at pH 5.6 of 15.3 ± 1.0 h (red circles and fit curve), and the half-time of 18.1 ± 0.5 h for pH 2.0 (green triangles and fit curve), suggesting that the pH had only a subtle effect on the aggregation half-time of the AP-hairpin.

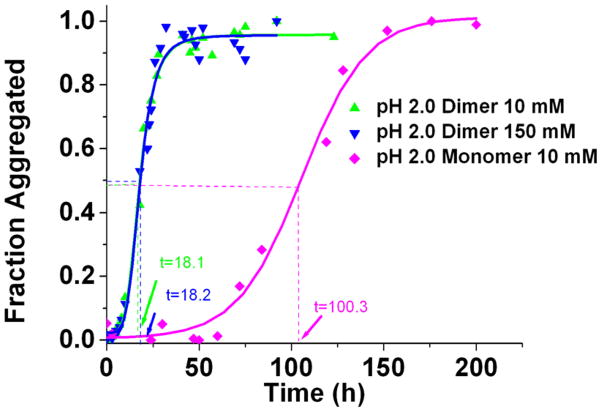

The effect of ionic strength on the AP-hairpin aggregation kinetics was evaluated. The ionic strength was tested at pH 2.0 because in the previous experiments with the monomer [15], it showed that the aggregation half-time was greatly reduced when the ionic strength was increased from 10 mM to 150 mM. The experiments for the two ionic strengths were performed in parallel and the corresponding ThT fluorescence results are shown in Figure 3 and the non-normalized points in Figure S3. According to these analyses, there is no effect of the ionic strength on the aggregation kinetics of the AP-hairpin. The differences in the plateaus values for the monomer and AP-dimers in Figure S2 suggest that there are differences in the peptides secondary structures in the aggregates formed by these two species. The half-times for the AP-hairpin at high and low ionic strengths that were essentially identical (18.2 ± 0.6 and 18.1 ± 0.5 hrs, respectively). Table 1 shows that this is in strong contrast for the monomer aggregation data, where the half-time of the aggregation process of the monomeric peptide is 85.3 ± 11.1 hrs at low ionic strength and 40.8 ± 1.7 hrs at high ionic strength.

Figure 3.

ThT fluorescence curves obtained for AP-hairpin at pH 2 and different ionic strengths. Green triangles are AP dimer in pH 2.0 10 mM, blue triangles are AP -hairpin in pH 2.0 150 mM, and magenta diamonds are monomer in pH 2.0 10 mM.

Table 1.

The effect of pH and ionic strength on linear monomer and AP antiparallel hairpin dimer half- times (hours) in ThT fluorescence experiments.

| Conditions | Half-time for the monomer (hrs) | Half-time for AP dimer (hrs) |

|---|---|---|

| pH 5.6, 10 mM | 8.9 ± 2.6 | 15.3 ± 1.0 |

| pH 2.0, 10 mM | 85.3 ± 11.1 | 18.1 ± 0.5 |

| pH 2.0, 150 mM | 40.8 ± 1.7 | 18.2 ± 0.6 |

3.2 Morphology of Resulting Aggregates Assessed by AFM

To get insight into the morphology of aggregates formed by monomeric and AP -hairpin species, AFM imaging was used to analyze the aggregate samples collected at the plateau values of the ThT kinetic curves.

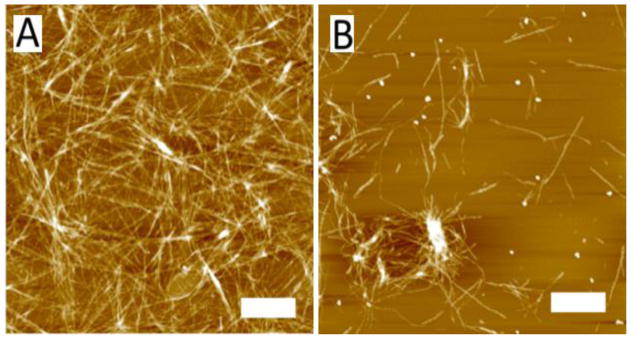

The set of images in Figure 4A shows the morphologies of aggregates assembled from the monomers that were incubated in water. Likewise, Figure 4B shows the morphologies of aggregates assembled from the AP-hairpin in water. The pH of water solutions was approximately pH 2. Two different morphologies, globular aggregates and fibrils are usually identified in the AFM images of amyloid aggregates, and these were present in these samples as well. The results show that in water, there were no major differences in morphology between the aggregates formed by monomers and AP-hairpins as fibrillar aggregates tended to form most readily under water for both peptides. This finding is in line with the ThT aggregation experiments shown in Figure S3B. Note that these are not normalized data demonstrating that both types of fibrils have similar affinity for ThT binding and pointing to a similarity of structures of fibrils.

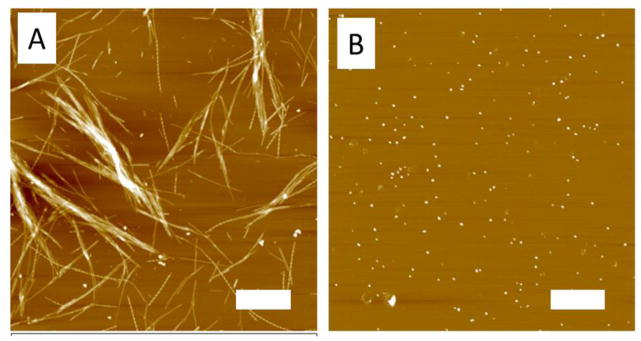

Figure 4.

AFM images of aggregates formed in water. Aggregates are formed by the monomers (A) and AP-hairpin (B). The scale bars represent 1 μm.

The morphologies of aggregates formed at pH 2.0 (10 mM NaCl) were also analyzed by AFM. The images of aggregates formed from monomers are shown in Figure 5A. These are primarily fibrils. However, the aggregates formed at pH 2.0 10 mM by the AP-hairpin were mainly globular species, as shown in Figure 5B. This plot shows that there are only a few fibrils within the field. Thus AP peptide with the hairpin design does not form fibrils at acidic pH, although it aggregates more than five times faster than the monomer samples (Figure 3). Changing the conditions to pH 5.6 dramatically drops the yield of fibrillar aggregates for both samples. The set of images in Figure S4A shows the morphologies of aggregates assembled by the monomers at pH 5.6, and the set of images in Figure S4B shows the morphologies of aggregates assembled from the AP-hairpin at pH 5.6. Globular aggregates were by far the largest group of aggregates seen on both images. These small, globular oligomers can be clearly in both of the AFM images in Figure S4 as the brighter spherical features. There were also some slightly elongated features that are seen arranged in a vertical line at the middle of Figure S4A, as well as some slightly elongated features just below the center of Figure S4B. These features can form in a relatively short time when compared to the formation of longer fibrillar assemblies.

Figure 5.

AFM images of the monomer and AP dimers. Monomers (A) and AP dimers (B) were imaged in air after incubation in pH 2.0 10 mM NaCl. The scale bars represent 1 μm.

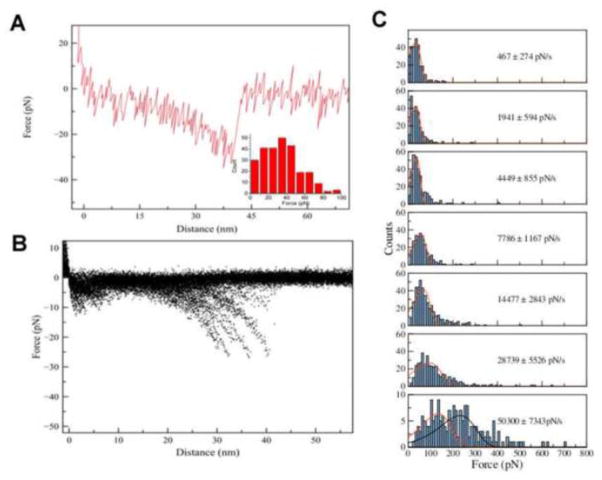

3.3 Force Spectroscopy Analysis

In order to characterize the interaction between the peptides and what role the potential dimerization has with respect to the interpeptide interactions, AFM force spectroscopy was applied. Since analogous experiments for the monomer species were performed earlier [15] at pH 5.6 in 11 mM acetate buffer, we applied the same approach to the AP species. Individual AP molecules were covalently tethered to the AFM tip and the mica surface via the flexible PEG linker and their interaction was probed upon the approach-retraction cycles of the AFM tip to the surface. The experiments were performed at pH 5.6 and a representative force curve is shown in Figure 6A. The initial smooth part of the curve corresponds to the extension of the tethers that is extrapolated by the worm-like chain (WLC) model as shown by a solid curve. This entropic process is accompanied by the complex dissociation with a rupture force value (32 pN) being the major variable of the force probing experiment. The overlay of 428 force curves is shown in Figure 6B and the distribution of the rupture forces over 428 rupture events is shown as an inset in Figure 6A.

Figure 6.

Force spectroscopy of the AP-hairpins. Representative force-distance curve (A) measured at pH 5.6 with apparent loading rate (ALR) 1941 pN/s, with the inset of forces obtained at this loading rate. The overlay of force distance curves (B) is shown here. (C) The histograms of the rupture force distribution measured at pH 5.6 at ALR 467 pN/s, 1941 pN/s, 4449 pN/s, 7786 pN/s, 14477 pN/s, 28739 pN/s, and 50300 pN/s. The most probable rupture force (F) for each loading rate was calculated by probability function fitting, resulting in forces at the histograms maxima of 32 pN, 32 pN, 37 pN, 56 pN, 65 pN, 95 pN, and 134 pN from top histogram to bottom histogram.

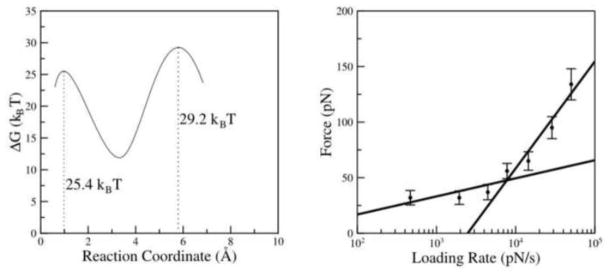

Next, we performed pulling experiments at a range of pulling rates between 100 and 2000 nm/s to characterize the complex dissociation process using dynamics force spectroscopy (DFS) methodology as described before [19–22]. The rupture forces increase with the pulling rates. This is demonstrated by Figure 6C in which the force distribution histograms obtained at the different loading rates are presented. These distributions were approximated with probability function fit [20–22] and the values corresponding to the maxima were used to generate the DFS spectra in which the rupture force values are plotted against logarithm of apparent pulling rate values. The major peaks on the force distributions were used in this plot. The second peak on the last distribution with the force value twice of that for the first peak correspond to the double rupture events appearing in these experiments at the high pulling rates. The data points on DFS plots are fit by two linear lines suggesting that the AP hairpin dissociation pathway has two barriers [27]. The DFS plots enable us to extract the barrier parameters. From the slope the positions of barriers (xβ) is obtained and the intercepts obtained after the extrapolation to the zero pulling rate produce the off-rate constant (koff). These values corresponding to both transitions are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of parameters obtained from dynamic force spectroscopy of the AP-hairpin at pH 5.6.

| System | koff (1) (s−1) (a) | xβ(1) (Å) (a) | koff (2) (s−1) (a) | xβ(2) (Å) (a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 5.6 AP-hairpin | 1.3 ± 3.7 | 5.8 ± 3.5 | 59.2 ± 15.1 | 0.98 ± 0.19 |

koff, dissociation rate constant for the peptide-peptide pair. xβ, the position of energy barrier. The indices 1 and 2 in the subscript of the parameters refer to the outer and inner barriers of the energy landscape, respectively.

Figure 7 summarizes the dynamic force spectroscopy results for the AP-dimer. Figure 7A shows the plot of Fr obtained for different pulling velocities versus the apparent loading rates on a logarithmic scale. The ΔG values and maxima locations in Table 2 obtained from the fitting the plot in Figure 7A with the Bell-Evans model (see M&M section) were used to reconstruct the energy landscape profile for the dissociation of the AP dimeric complex shown in Figure 7B. The first (inner barrier) and second (outer barrier) transient states for this process are located at 0.06 nm and 0.37 nm from the ground state of the complex. The barriers heights (ΔG values) for inner barrier (ΔG = 26 ± 0.54 kBT) and outer barrier (ΔG = 28.4 ± 0.61 kBT) were obtained from the off-rate constant (koff) values (Table 2).

Figure 7.

Dynamic force spectroscopy plot and the energy profile. Dynamic force spectroscopy of AP dimer (A) and the energy profile obtained from the parameters shown in Table 2 (B). The ΔG values for outer barrier and inner barrier are 25.4 kBT and 29.2 kBT, respectively.

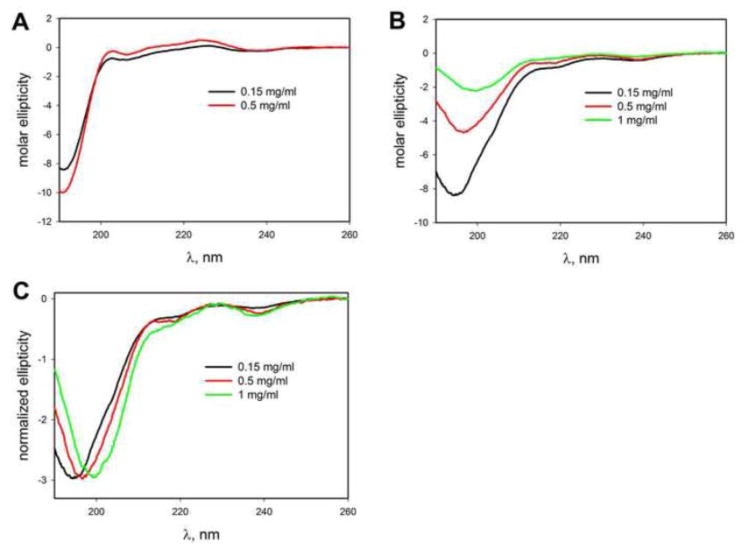

3.4 Secondary Structure Analysis of the Monomer and Dimer Assessed by CD measurements

We applied circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy [5, 12] to characterize the secondary structure of the peptides under a variety of different conditions, such as various pH values and the presence of different cosolvents and osmolytes. First, the data shown in Figure 8 (concentration 0.15 mg/mL) demonstrate that structurally both peptides are similar and a deep minimum at ~190 nm indicates a primarily unfolded conformation of both peptides. The effect of concentration was studied. To this end, the CD spectra were recorded at pH 7 at various peptide concentrations. This analysis revealed no significant concentration effect on the monomer CD spectra (Figure 8A). With the increase in the dimer concentration the peak intensity decreased with a shift from 195 to 199 nm (Figure 8B), however, the peak shape remains largely unchanged as seen from the comparison of normalized CD spectra in Figure 8C. These results are consistent with formation of oligomeric aggregates by AP dimer at higher concentrations (0.5 mg/ml and above). Formation of oligomers by amyloidogenic proteins and peptides is a common process, and they vary in their secondary and tertiary structure and stability. It appears that oligomers detected in Fig. 8B are likely to be quite unstable since all solutions for CD measurements were prepared from the same stock solution (see Materials and Methods) and whatever oligomers were present there must have dissociated upon dilution to lower concentration (e.g. 0.15 mg/ml). Investigation of these intermediates in more detail is beyond the scope of the current manuscript.

Figure 8.

Concentration dependence of CD spectra of the peptides at pH7. The concentration dependence of monomer (A) and dimer (B) is shown. (C) Normalized spectra of AP dimer to indicate lack of significant structural changes with increased concentration.

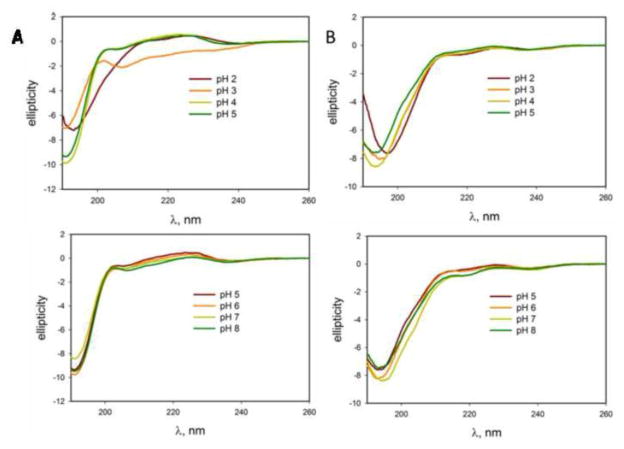

Next, the effect of pH on the peptide structures was studied at the peptide concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. The data in Figure 9A show no structural changes for the monomer in the pH range of 5–8, although structural changes do occur at acidic pH down to pH 2.0. The dimer demonstrates stronger resistance to the pH changes, as seen in Fig. 9B. Even at acidic pH, its CD spectra show very subtle changes. Both peptides generally maintain a random coil structure from pH 2.0 through pH 8.0.

Figure 9.

pH dependence for monomer and AP-hairpin. Circular dichroism spectra of the monomer pHs in column (A) and AP -hairpin in column (B).

Additionally, the effect of trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) on secondary structure of these peptides was assessed. TMAO is a naturally occurring osmolyte that stabilizes proteins against denaturation. It was shown that osmolytes increase protein stability and that the two-state folding behavior of proteins is maintained in the presence of these compounds [28]. Figure S5 shows the results obtained for both peptides in a broad range of TMAO concentrations. The increase in the TMAO concentration noticeably changed the shape of CD spectra of the monomer (Figure S5A) indicating that this osmolyte induces structural changes of the peptide. Comparatively, no such spectral changes were detected for the dimer (Figure S5B) suggesting that the dimer retains the initial unfolded conformation regardless of the TMAO presence.

In addition to TMAO, the effect of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-propan-2-ol (HFIP) was tested. HFIP is one of the strongest helix-inducing and stabilizing co-solvents [29] that is widely used for structural studies of amyloidogenic proteins. The results shown in Figure S6A demonstrate a change of the conformation of the monomeric peptide upon the increase in the HFIP concentration as evidenced by a dramatic change in the shape of far-UV CD spectra. This change corresponds to the transition from a mainly disordered structure at 0% and 10% HFIP to a primarily α-helical structure at 50% HFIP. On the other hand, Figure S6 B shows that although there are some changes in the CD spectra of the AP-hairpin, these changes are not as dramatic as those detected for the monomeric peptide.

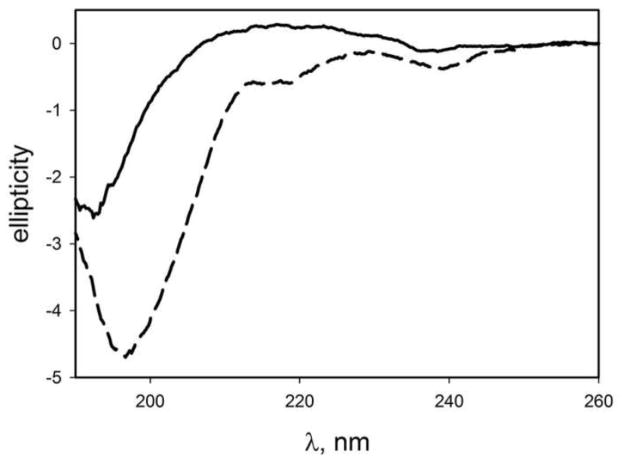

The CD measurements were performed at relatively high concentration of the peptides raising the concern of whether a spontaneous aggregation of the peptides occurred during the sample preparation for the CD measurements. To test this assumption, we performed the CD measurements of the aggregated AP-hairpin sample. The peptide was incubated at pH5.6 for 24 h corresponding to the plateau level in Figure 2. The sample was imaged with AFM (Figure S7) and these data confirm the globular morphology of the aggregates. The morphology of the sample did not change over additional two-day incubation at room temperature or multiple freezing-thawing cycles of the sample to warrant the sample stability during the sample preparation for the CD study. The CD spectra of AP aggregates are shown in Figure 10 (solid line). The CD spectrum of the AP-hairpin sample is shown as a dashed line for comparison. They show that the two spectra are distinctly different. The AP aggregates spectrum has a sharp minimum at 193 nm and a shallow maximum at 217 nm and it is different from that of AP dimer and had some resemblance to a typical spectrum of polyproline II helix [30]. Thus, the changes in the CD spectra of the dimer at higher peptide concentrations are not due to formation of stable aggregates.

Figure 10.

CD spectrum of globular aggregates of AP-hairpin (solid line). Dashed line shows the spectrum of the monomeric AP-hairpin sample. A circular dichroism spectrum of globular AP aggregates suggests a polyproline II-like structure.

Altogether, the CD analysis leads to the conclusion that the AP-dimer is characterized by very low structural plasticity compared to that of the monomer. While AP-hairpin appears to form transient oligomers at higher protein concentrations, their instability makes it unlikely that they account for apparent stability of the conformation of this peptide in a variety of conditions. This increased stability of AP-hairpin may well interfere with its aggregation to amyloid fibrils. Similar effect of the restricted conformational mobility was observed in [31] where double cysteine mutant of Aβ(21C/A30C) was unable to form fibrillar aggregates.

4. Discussion

The comparative studies of the linear monomeric and hairpin designs of Sup35 heptapeptide revealed a number of novel properties of these peptides and their interactions that could be related to differences in their aggregation kinetics. We discuss these properties in the sections below.

4.1. The Sup35 peptide aggregation kinetics probed by ThT fluorescence

Although peptides with both designs follow typical sigmoidal aggregation kinetics, they quantitatively differ from each other. The AP-hairpin design in which two monomers are connected with a short -(d-Pro)-G linker forcing the antiparallel arrangement of the monomers change the aggregation propensity of the Sup35 peptide. Although monomeric Sup35 peptide appears to aggregate slightly faster than the AP-hairpin at pH 5.6 (Figure 2), the situation is opposite at acidic pH (pH 2.0). According to Figure 3, at these conditions, the AP-dimers aggregate five times faster than the monomeric form does, and the corresponding aggregation profile does not depend on the ionic strength of solution. The similarity in the aggregation kinetics at pH 5.6 for both Sup35 designs is in line with AFM topographic studies (Figure S4). The comparison of all results suggests that kinetics of the aggregation and their morphology depends on ionic strength and pH. The lack of fibrils formation by both peptides at pH values close to the peptides pI (pH 5.6) indicates to the contribution of electrostatic interactions to the interpeptide interaction that we identified in our recent publication [15]. Note in this regard studies with Aβ(21C/A30C) peptide in which the internal hairpin was stabilized by disulfide bonds formed by Cys residues incorporated into positions 21 and 30 [31]. Such peptides form oligomeric samples, but are not capable of forming amyloid fibrils.

4.2. The structure and morphology of aggregates formed by the Sup35 samples

The antiparallel orientation of Sup35 monomers in dimers is supported by Replica exchange MD simulation described in [32]. The results show the monomer (CGNNQQNY) adopts the random coil structure. The d-Pro-G adopts a U- turn geometry keeping both monomeric units in a close proximity. Similarly, the AP-hairpin also demonstrates rather similar pattern with no clear stable secondary structure. The AP structures with antiparallel β-strands are very rare which is in line with the CD measurements.

In the Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation we modeled the assembly of monomers into dimers with the β-sheet conformation and the results are shown in Fig. S9. Replica exchange MD landscape reveals two deepest minima corresponding to two structures with the antiparallel topology differing in the length of antiparallel β-strands. Model 2 corresponds to the in-register orientation of the monomers with all amino acids involved in the hydrogen bonding, whereas in Model 1, only five residues out of seven are involved in the antiparallel β-sheet structure formation, termed out-of-register conformation. Energetically both conformations are very close, but our recent computational analysis of rupture events with the use of Monte Carlo pulling approach showed that Model 1 correspond to the majority of inter-monomer interactions observed in experiment [32]. In the AP-hairpin, d-Pro-G turn impose steric limitations for the formation of the out-of-register conformation, which explains the lack of adoption of antiparallel β-strands geometry by the AP-hairpin construct.

The antiparallel arrangements of Sup35 monomers is at odds with crystallographic data [3]. That studies reveal parallel in-register arrangement of monomers in β-sheet conformation, where it was paired up with another sheet, and the strands in one sheet are antiparallel to the other sheet [33]. However, we need to take into consideration a number of factors. First, the steric zipper structure consists of dry interfaces that have no water [3, 13]. The peptides are fully hydrated in aggregation experiments and MD simulations are involved a necessary amounts of water molecules. Second, crystallographic date correspond to the situation in which all monomers are tightly packed, so interactions with all neighbors contribute the energy minimum of the entire multi- monomer system. So isolated dimers should have different environment that should change the peptides structure and arrangement. This consideration is supported by a recent computational analysis of the hexamer of Sup35 peptide [14]. The initial crystallographic structure of the hexamer was unstable and dissociated over time. Therefore, we hypothesize that Sup35 monomers are arranged in antiparallel orientation at early stages of the aggregation process, but the formation of large aggregates can lead to conformational transition and rearrangements of monomers. The water displacement can facilitate such structural transition.

The antiparallel arrangement of monomers within dimers has a profound effect on morphologies of aggregates. Although in water fibrillar aggregates are essentially the only morphology for both species (Figure 4), the change of conditions reveal the difference between the aggregation propensities of the AP-hairpins and monomers. The most dramatic difference was observed at acidic pH (Figure 5). If monomers continue forming fibrils with rather straight morphologies, the AP-hairpins assemble into globular aggregates with fibrils being found very rarely. Similar aggregates are formed by the monomer at pH 5.6 along with fibrils that are rather minor species compared to globular aggregates. Fibrils appear in the AP samples, but still globular aggregates remain very predominant species. Some insight into the secondary structure of these aggregates can be obtained from their CD spectra (Fig. 10) that resemble those of polyproline II helix. While these spectra are not sufficient to tell us about the secondary structure of these oligomers, it is clear that they are structurally distinct from both non-aggregated AP-hairpin and amyloid fibrils. These data suggest that antiparallel arrangement of monomers within the dimers facilitates their assembly into globular aggregates. It is likely that unfolding of the hairpin structure is needed for the fibrils assembly, and pure water provides such conditions.

The structural stability of AP-dimers is supported by far-UV CD measurements (Figure 9), according to which the AP secondary structure changes very little under the various conditions, suggesting that the AP-hairpin is in a locked configuration. Structural plasticity was also a critical factor in distinguishing different modes of Aβ aggregation. It was demonstrated in ref. [34] that phosphorylation of serine 26 impairs fibrillation while stabilizing the nonfibrillar aggregates because the phosphate group at that position diminishes the propensity of a peptide to form a β-hairpin that is necessary for fibril formation. The conformational rearrangement that is needed for fibril formation is not present, much like what was observed with our hairpin dimer [34]. Although the predominant formation of oligomeric aggregates was reported in ref. [35], these aggregates did not induce changes in the ThT fluorescence suggesting that they do not form β-sheet structure. The AP-hairpin oligomers assembled at pH 2 do induce increase in the ThT fluorescence intensity. Furthermore, the level of ThT fluorescence for AP-hairpin is higher compared to the levels detected for the monomeric design (Figure S2) suggesting that the secondary structure existing in oligomeric peptides is favorable for ThT binding and enhanced fluorescence.

Previous studies confirmed that the initial dimer formation favors the antiparallel orientation 60% of the time, with the remainder of the arrangements being random in nature [36]. However, beyond the trimer there is another shift of interactions, and the majority of the interactions tend to shift from antiparallel to about 70% of the orientations having a majority of a mix between antiparallel and parallel orientations within the β-sheet [36]. The simulations show that the antiparallel arrangement is essential to the initial stages of aggregate formation, stabilizing the initial aggregated forms [37]. The X-ray data show mature fibrils having a parallel arrangement between GNNQQNY sequences. However, when the antiparallel configuration is locked with a short loop (as in the case of our study), it can then impede the creation of fibrillar aggregates.

Another possibility is that the interaction between the β-strands within the AP-hairpin peptide may be too strong because of the presence of the short loop at the center of the peptide. The short loop could also be very stiff, which can limit possibility to adopt different structures, with the notable exception of water. According to the CD spectroscopy data (Figure 9), there was some variation in the secondary structure of the linear monomer at low pH, which corresponded to changes in the half-times in the aggregation experiments. On the other hand, there was no variation in the secondary structure across all pHs tested on the antiparallel hairpin dimer, and this corresponded to little change in half-times in the aggregation experiments across all pHs tested. The CD data appear to correlate with the ThT data, as the linear monomer had changes in kinetics and subtle changes in secondary structure with change in pH. The AP-hairpin had subtle changes with respect to the aggregation kinetics, and then when tested for changes in secondary structure in solutions with different pH values, there was no discernable change in the secondary structure. The AP-hairpin had a structure that was more stable than with the linear monomer. However, the structure appears to be too stable and rigid that most changes in the external environment are possibly preventing any crucial late stage conformational transition that may be required for aggregation. This was hypothesized with the β-lactoglobulin protein [38] where a structural interruption to the hydrophobic core of the protein was necessary before the final step leading to aggregation. There were three phases of aggregation, with the earlier phases consisting of weakly associated aggregates [38].

The tendency of the hairpins to have a different morphology from the linear monomer is explained by a different tertiary structure of the hairpin which can influence how the fibril self-assembles, and ultimately the morphology of the resulting aggregates. This hypothesis agrees with the model that has been proposed based on the solid-state NMR studies of yeast prion proteins, RNQ1 and URE3 [10, 39, 40]. The sequence studied was scrambled to demonstrate that the secondary structure itself, and not the sequence, is responsible for the templating of the monomer being added to the end of the forming fibril. Along with another study involving RNQ1 [41] it was demonstrated that even adding a prion domain of a different protein can result in templating, as was demonstrated when adding the prion domain of Sup35 to the end of RNQ1 or URE3.

4.3. The hairpin assembly of Sup35 and the effect of electrostatics on the aggregation kinetics

X-ray powder diffraction of microcrystal data of GNNQQNY showed in-register and parallel arrangement of the monomers within the crystals [3]. This parallel in-register arrangement forms a β-sheet, where it was paired up with another sheet, and the strands in one sheet are antiparallel to the other sheet [33]. These experiments were performed at acidic pH conditions, with positively charged N terminus and neutrual C terminus. In the absence of electrostatic interaction from N-C terminal residues and in the presence of the interactions from the aromatic ring of tyrosine residues [42], two monomers at such conditions prefer the parallel arrangement of β-strands. In contrast, at neutral pH, both N- and C-terminal residues contain charges, the peptides prefer the antiparallel structure due to electrostatic interaction [43]. On one hand, in comparison with the parallel structure, there are more hydrogen bonds within two adjacent monomers. The antiparallel structure is much more stable than parallel structure. On the other hand, the charged C-terminus will disturb the interaction of tyrosine residues at C-terminus and further prevent formation of parallel configuration. In the AP-hairpin construct, the C-terminal end of one monomer is connected with the N-terminus of the second monomer. Therefore, there is no electrostatic contribution to their antiparallel arrangement within the dimer. As a result, the effect of the ionic strengths and pH on the aggregation of the AP-construct should be small compared to the monomer and this is in line with our experimental data.

Overall, the experiments with linear and antiparallel β-hairpin designs of Sup35 peptide led to a number of novel findings related to the peculiarities of peptide interactions and the process of its aggregation. One of the unexpected findings was a conformational stiffness of the hairpin design of the peptide. Although the AP-hairpin was able to form amyloid aggregates detectable by ThT fluorescence and AFM imaging, the range of aggregate morphologies was limited. Specifically, AP-hairpin fibrils were a very rare species compared to the aggregated form of the linear peptide for which the fibrils were the major species. This finding suggests a model, according to which oligomers with different conformations are formed at early stages and not all of them lead to the fibrils. This model suggests that there is a set of misfolded conformations for the peptide and freezing the conformational mobility of the monomer limits the range of aggregated morphologies. An alternative model in which the conformational switch can occur at the level of oligomers should be considered as well. This conformational switch within oligomers can also be dependent on the monomer conformational mobility, although intermolecular interactions should play the major role in this model. The models can be tested by making other designs such as hairpins with different loop sizes, mutlifolded peptides, and these ideas lay a foundation for the future studies with Sup35 peptide. The approaches described in this paper can be extended to longer prion-derived peptides including the full-length protein and such studies are our long-term goals.

5. Conclusions

The aggregation kinetics of the AP-hairpin has low variability, regardless of pH or ionic strength. The secondary structure for AP-hairpin remained stable when compared to the linear monomer under the same changes in the environment, as was tested with CD spectroscopy. The structure of AP-hairpin was not altered even in the presence of osmolyte HFIP, a known stabilizer of α-helices. The monomer was also more noticeably affected than AP-hairpin by changes in conditions such as low pH, high ionic strength, or osmolytes at high concentrations. The AFM data shows more globular aggregates and a lack of fibrils for AP-hairpin than for the linear monomer under comparable conditions. The AP-hairpin had a lower tendency to form fibrils than the linear monomer at pH 2.0 at low ionic strength, where the most fibrils formed by the linear monomer. The AP dimer also was able to form fibrils when incubated in pure water, which was the only condition in which the AP-hairpin could form fibrils. The implications of imaging data and the spectroscopic data, is that the antiparallel dimer has a noticeably different behavior under different conditions. This means that the AP-hairpin structure did use an alternate pathway forming aggregates mainly with a globular morphology.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The pre-assembly of the peptide monomer into a hairpin design changes its aggregation propensity.

Compared to the monomer AP dimer forms fibrils with a low efficiency.

CD measurements showed that AP-dimer is characterized by the limited conformational dynamics.

Hypothesis - the morphology of aggregates is defined by the conformational dynamics of monomers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank A. Krasnoslobodtsev, Z. Lv, L. Shlyakhtenko as well as other Lyubchenko lab members for insightful discussions. The authors would also like to thank the Uversky lab members as well for their insightful discussions.

The work was supported from grants by EPS – 1004094 (NSF) and 5R01GM096039-04 (NIH) to YLL, as well as the UNMC graduate student research fellowship to AP.

Footnotes

Abbreviations Used: AFM = Atomic Force Microscopy, AP-dimer = CGNNQQNY-(dPro)G-GNNQQNY, APS = Aminopropyl silatrane, CD = Circular Dichroism, DFS = Dynamic Force Spectroscopy, DMSO = Dimethylsulfoxide, HFIP = 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-propan-2-ol, koff = Off-rate constant, MD = Molecular Dynamics, NHS-PEG-MAL = N-hydroxysuccinimide-polyethylene glycol-maleimide, TCEP = Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, ThT = Thioflavin T, TMAO = Trimethylamine-N-oxide, WLC = Wormlike chain approximation, xβ = Distance of the ground state to the transition state.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions:

Yuri L. Lyubchenko, Alexander Portillo designed the experiments. Alexander Portillo performed the ThT fluorescence, AFM imaging, and AFM force spectroscopy experiments, as well as the data analysis resulting from these experiments. Mohtadin Hashemi made the AP-oligomer samples for CD measurements, performed their AFM characterization and analyzed DFS data. Yuliang Zhang performed the MD and MC simulations. Leonid Breydo and Vladimir Uversky performed the CD experiments, data analyses and contributed to the CD related discussion of the paper. Yuri L. Lyubchenko, Alexander Portillo and Vladimir Uversky wrote the paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Balbirnie M, Grothe R, Eisenberg DS. An amyloid-forming peptide from the yeast prion Sup35 reveals a dehydrated beta-sheet structure for amyloid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2375–2380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041617698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg An amyloid-forming peptide from the yeast prion Sup35 reveals a dehydrated b-sheet structure for amyloid. PNAS. 2001;98:2375–2380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041617698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson R, Sawaya MR, Balbirnie M, Madsen AO, Riekel C, Grothe R, Eisenberg D. Structure of the cross-beta spine of amyloid-like fibrils. Nature. 2005;435:773–778. doi: 10.1038/nature03680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wetzel R, Shivaprasad S, Williams AD. Plasticity of amyloid fibrils. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1–10. doi: 10.1021/bi0620959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tjernberg LO, Tjernberg A, Bark N, Shi Y, Ruzsicska BP, Bu Z, Thyberg J, Callaway DJ. Assembling amyloid fibrils from designed structures containing a significant amyloid beta-peptide fragment. Biochem J. 2002;366:343–351. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glover JR, Kowal AS, Schirmer EC, Patino MM, Liu JJ, Lindquist S. Self-seeded fibers formed by Sup35, the protein determinant of [PSI+], a heritable prion-like factor of S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1997;89:811–819. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narayanan S, Walter S, Reif B. Yeast prion-protein, sup35, fibril formation proceeds by addition and substraction of oligomers. Chembiochem. 2006;7:757–765. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess S, Lindquist SL, Scheibel T. Alternative assembly pathways of the amyloidogenic yeast prion determinant Sup35-NM. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:1196–1201. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krzewska J, Tanaka M, Burston SG, Melki R. Biochemical and functional analysis of the assembly of full-length Sup35p and its prion-forming domain. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1679–1686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shewmaker F, Ross ED, Tycko R, Wickner RB. Amyloids of shuffled prion domains that form prions have a parallel in-register beta-sheet structure. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4000–4007. doi: 10.1021/bi7024589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Wel PC, Lewandowski JR, Griffin RG. Solid-state NMR study of amyloid nanocrystals and fibrils formed by the peptide GNNQQNY from yeast prion protein Sup35p. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5117–5130. doi: 10.1021/ja068633m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng J, Ma B, Tsai CJ, Nussinov R. Structural stability and dynamics of an amyloid-forming peptide GNNQQNY from the yeast prion sup-35. Biophys J. 2006;91:824–833. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.083246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawaya MR, Sambashivan S, Nelson R, Ivanova MI, Sievers SA, Apostol MI, Thompson MJ, Balbirnie M, Wiltzius JJ, McFarlane HT, Madsen AO, Riekel C, Eisenberg D. Atomic structures of amyloid cross-beta spines reveal varied steric zippers. Nature. 2007;447:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature05695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srivastava A, Balaji PV. Size, orientation and organization of oligomers that nucleate amyloid fibrils: clues from MD simulations of pre-formed aggregates. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1824:963–973. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Portillo AM, Krasnoslobodtsev AV, Lyubchenko YL. Effect of electrostatics on aggregation of prion protein Sup35 peptide. J Phys Condens Matter. 2012;24:164205. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/24/16/164205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanger HE, Gellmam SH. Rules for Antiparallel β-Sheet Design: D-Pro-Gly Is Superior to L-Asn-Gly for β-Hairpin Nucleation. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:4236–4237. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shlyakhtenko LS, Gall AA, Filonov A, Cerovac Z, Lushnikov A, Lyubchenko YL. Silatrane-based surface chemistry for immobilization of DNA, protein-DNA complexes and other biological materials. Ultramicroscopy. 2003;97:279–287. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3991(03)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abid K, Soto C. The intriguing prion disorders. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2342–2351. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atarashi R, Sim VL, Nishida N, Caughey B, Katamine S. Prion strain-dependent differences in conversion of mutant prion proteins in cell culture. J Virol. 2006;80:7854–7862. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00424-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim BH, Palermo NY, Lovas S, Zaikova T, Keana JF, Lyubchenko YL. Single-Molecule Atomic Force Microscopy Force Spectroscopy Study of Abeta-40 Interactions. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5154–5162. doi: 10.1021/bi200147a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu J, Lyubchenko YL. Early Stages for Parkinson’s Development: α-Synuclein Misfolding and Aggregation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s11481-008-9115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu J, Malkova S, Lyubchenko YL. alpha-Synuclein misfolding: single molecule AFM force spectroscopy study. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:992–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ray C, Brown JR, Akhremitchev BB. Correction of systematic errors in single-molecule force spectroscopy with polymeric tethers by atomic force microscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:1963–1974. doi: 10.1021/jp065530h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain S, Udgaonkar JB. Defining the pathway of worm-like amyloid fibril formation by the mouse prion protein by delineation of the productive and unproductive oligomerization reactions. Biochemistry. 2011;50:1153–1161. doi: 10.1021/bi101757x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans E, Ritchie K. Dynamic strength of molecular adhesion bonds. Biophys J. 1997;72:1541–1555. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78802-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karle IL, Gopi HN, Balaram P. Peptide hybrids containing alpha - and beta-amino acids: structure of a decapeptide beta-hairpin with two facing beta-phenylalanine residues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3716–3719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071050198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen L, Khurana R, Coats A, Frokjaer S, Brange J, Vyas S, Uversky VN, Fink AL. Effect of environmental factors on the kinetics of insulin fibril formation: elucidation of the molecular mechanism. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6036–6046. doi: 10.1021/bi002555c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mello CC, Barrick D. Measuring the stability of partly folded proteins using TMAO. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1522–1529. doi: 10.1110/ps.0372903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirota N, Mizuno K, Goto Y. Cooperative alpha-helix formation of beta-lactoglobulin and melittin induced by hexafluoroisopropanol. Protein Sci. 1997;6:416–421. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rucker AL, Creamer TP. Polyproline II helical structure in protein unfolded states: lysine peptides revisited. Protein Sci. 2002;11:980–985. doi: 10.1110/ps.4550102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hard T. Protein engineering to stabilize soluble amyloid beta-protein aggregates for structural and functional studies. Febs J. 2011;278:3884–3892. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang YL. The Structure of Misfolded Amyloidogenic Dimers. Computational Analysis of Force Spectroscopy Data. Biophysical Journal. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.10.053. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benzinger TL, Gregory DM, Burkoth TS, Miller-Auer H, Lynn DG, Botto RE, Meredith SC. Propagating structure of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid(10-35) is parallel beta-sheet with residues in exact register. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13407–13412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rezaei-Ghaleh N, Amininasab M, Giller K, Kumar S, Stundl A, Schneider A, Becker S, Walter J, Zweckstetter M. Turn plasticity distinguishes different modes of amyloid-beta aggregation. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:4913–4919. doi: 10.1021/ja411707y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soto C, Castano EM. The conformation of Alzheimer’s beta peptide determines the rate of amyloid formation and its resistance to proteolysis. Biochem J. 1996;314(Pt 2):701–707. doi: 10.1042/bj3140701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nasica-Labouze J, Meli M, Derreumaux P, Colombo G, Mousseau N. A multiscale approach to characterize the early aggregation steps of the amyloid-forming peptide GNNQQNY from the yeast prion sup-35. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vitagliano L, Ruggiero A, Pedone C, Berisio R. Conformational states and association mechanism of Yersinia pestis Caf1 subunits. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:804–810. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giurleo JT, He X, Talaga DS. Beta-lactoglobulin assembles into amyloid through sequential aggregated intermediates. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:1332–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shewmaker F, Wickner RB, Tycko R. Amyloid of the prion domain of Sup35p has an in-register parallel beta-sheet structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19754–19759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609638103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wickner RB, Shewmaker F, Kryndushkin D, Edskes HK. Protein inheritance (prions) based on parallel in-register beta-sheet amyloid structures. Bioessays. 2008;30:955–964. doi: 10.1002/bies.20821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vitrenko YA, Gracheva EO, Richmond JE, Liebman SW. Visualization of aggregation of the Rnq1 prion domain and cross-seeding interactions with Sup35NM. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1779–1787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gsponer J, Haberthur U, Caflisch A. The role of side-chain interactions in the early steps of aggregation: Molecular dynamics simulations of an amyloid-forming peptide from the yeast prion Sup35. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5154–5159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0835307100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vitagliano L, Esposito L, Pedone C, De Simone A. Stability of single sheet GNNQQNY aggregates analyzed by replica exchange molecular dynamics: antiparallel versus parallel association. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2008;377:1036–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.