Abstract

Fine chemicals that are physiologically active, such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, nutritional supplements, flavoring agents as well as additives for foods, feed, and fertilizer are produced by enzymatically or through microbial fermentation. The identification of enzymes that catalyze the target reaction makes possible the enzymatic synthesis of the desired fine chemical. The genes encoding these enzymes are then introduced into suitable microbial hosts that are cultured with inexpensive, naturally abundant carbon sources, and other nutrients. Metabolic engineering create efficient microbial cell factories for producing chemicals at higher yields. Molecular genetic techniques are then used to optimize metabolic pathways of genetically and metabolically well-characterized hosts. Synthetic bioengineering represents a novel approach to employ a combination of computer simulation and metabolic analysis to design artificial metabolic pathways suitable for mass production of target chemicals in host strains. In the present review, we summarize recent studies on bio-based fine chemical production and assess the potential of synthetic bioengineering for further improving their productivity.

Keywords: Fine chemical, Synthetic bioengineering, Metabolic engineering, Enzymatic synthesis, Microbial fermentation, Bioinformatics

Introduction

Physiologically active fine chemicals such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, nutritional supplements, flavoring agents as well as additives for foods, feed, and fertilizer are produced enzymatically or through microbial fermentation. Although many of these compounds are present naturally, few are commercially available, because most are present in low abundance and may be difficult and expensive to purify. These disadvantages are overcome by bio-based fine chemical synthesis.

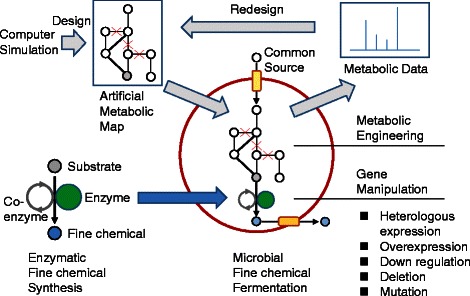

Bio-based fine chemical production is summarized in Figure 1. The enzymes are isolated from diverse organisms and are used in purified form in vitro or expressed by a suitable host cell.

Figure 1.

Bio-based fine chemical production through synthetic bioengineering. Enzymes convert substrates to the fine chemical of interest with or without a coenzyme. The enzymatic synthesis system is introduced into a microbial host strain to develop a microbial cell factory (blue arrow). The microbial system converts a common source into various fine chemicals, and they are accumulated in cells or in the medium. The productivity of a microbial cell factory is improved by genetic engineering of metabolic pathways (e.g. heterologous expression, overexpression, down-regulation, deletion, or mutation) according to an artificial metabolic map designed by computer simulation. Further, synthetic bioengineering (gray arrows) improves productivity by additional metabolic engineering according to the artificial map redesigned by the metabolic data of the microbial cell factory.

The advantage of microbial fermentation is that the supply of components required for growth of the host strain and synthesis of the product can be derived from inexpensive sources of carbon, nitrogen, trace elements, and energy [1]. In particular, coproduction of several fine chemicals from common carbon sources is more economical. The conditional requirements to fulfill the price advantages for the production of target fine chemicals are rapid cell growth to high density, and high cellular content and easy extraction of target fine chemicals. The bio-production of fine chemicals is typically performed at lower temperatures compared with those required for chemical syntheses, and important advantages of bio-based fine chemical production are cost-effectiveness and the use of processes that are not hazardous to the environment.

Synthetic bioengineering represents a recently developed novel approach to create optimized microbial cell factories for efficient production of target compounds through fermentation (Figure 1). Synthetic bioengineering is achieved using genetic engineering strategies designed according to artificial metabolic maps generated by computer simulation. Metabolomic data are critical to redesign a rational artificial metabolic map in which metabolic sources flow efficiently into the target compound. The concentrations of enzyme and substrates are readily controlled in an enzymatic reaction mixture; however, this is difficult in fermentations because precursors may be shunted through different metabolic pathways. Thus, synthetic bioengineering plays a critical role in controlling metabolic pathways to supply the optimal substrate ratios. To develop highly productive microbial fermentation systems for producing fine chemicals, the genes encoding the required enzymes are introduced into an appropriate host strain (Figure 1). Thus, the key for selecting the host strain, target metabolic pathways, or both to improve the production of fine chemicals by fermentation is the ability to genetically engineer modifications to the relevant metabolic pathways. Escherichia coli is often selected as the first candidate for producing target enzymes because of its well-developed genetic engineering system and its ability to express high levels of genes encoding target enzymes. In contrast, microorganisms such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Bacillus strains, Streptomyces strains, Corynebacterium glutamicum, and Aspergillus oryzae are selected as a host for fermentations depending on their specific metabolic pathways that are required to synthesize target products.

Here we summarize recently developed, well-characterized bio-based systems for producing the compounds as follows: γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), isoprenoids, aromatics, peptides, polyphenols, and oligosaccharides (Table 1). The developmental stages of these systems are different, and they illustrate the great potential of synthetic bioengineering approaches for producing all bio-based fine chemicals in the future.

Table 1.

Bio-based fine chemicals

| Chemical category | Example structure | Function | Production types |

|---|---|---|---|

| γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) |

GABA GABA |

Cosmetics | Microbial fermentation |

| Nutritional supplement | |||

| Food additive | |||

| Isoprenoid |

Isoprene Isoprene |

Medicine | Microbial fermentation |

| Cosmetics | |||

| Nutritional supplement | |||

| Flavoring agent | |||

| Food additive | |||

| Feed additive | |||

| Fertilizer additive | |||

| Aromatic compound |

Cinnamic acid Cinnamic acid |

Medicine | Microbial fermentation |

| Cosmetics | |||

| Nutritional supplement | |||

| Flavoring agent | |||

| Food additive | |||

| Alkaloid |

Reticuline Reticuline |

Medicine | Microbial fermentation |

| Peptide |

Glutathione Glutathione |

Medicine | Enzymatic production/Microbial fermentation |

| Cosmetics | |||

| Nutritional supplement | |||

| Food additive | |||

| Feed additive | |||

| Fertilizer additive | |||

| Polyphenol |

Resveratrol Resveratrol |

Medicine | Microbial fermentation |

| Cosmetics | |||

| Nutritional supplement | |||

| Flavoring agent | |||

| Food additive | |||

| Feed additive | |||

| Fertilizer additive | |||

| Oligosaccharide |

2’-fucosyllactose 2’-fucosyllactose |

Medicine | Enzymatic production |

| Cosmetics | |||

| Nutritional supplement | |||

| Flavoring agent | |||

| Food additive | |||

| Feed additive | |||

| Fertilizer additive |

GABA

The microbiological production of GABA serves as an excellent first example of how a system can be improved to increase yields (Table 2). GABA is an amino acid, which is not present naturally in proteins, that is synthesized by microorganisms, animals, and plants [2]. GABA functions as a neurotransmitter signals decreases blood pressure [3] and is used in functional foods and pharmaceuticals [4]. GABA, which was originally identified in traditional fermented foods such as cheese, yogurt [5] and kimchi [6], is synthesized through the alpha-decarboxylation of L-glutamate catalyzed by glutamate decarboxylase (GAD, EC 4.1.1.15) [2]. GABA is produced by lactic acid bacteria (LABs) such as Lactobacillus paracasei [7], L. buchneri [6], and L. brevis [8,9] (Table 2), and the latter produces high yields of GABA through fed-batch processes [10].

Table 2.

Microbial fermentation of GABA

| Strains | Source or engineered phenotype | Substrates | Yield (g/L) | Scale (L) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. paracasei NFRI 7415 | Isolated from fermented crucians | MSG | 31.1 | - | Komatsuzaki et al., 2005 [7] |

| L. buchneri MS | Isolated from Kimchi | MSG, Saccharides | 25.8 | - | Cho et al., 2007 [6] |

| S. salivarius subsp. thermophilus Y2 | Starter for yoghurt and cheese | MSG | 7.98 | 0.4 | Yang et al., 2008 [5] |

| L. brevis NCL912 | Isolated from Paocai | MSG | 35.6 | 0.1 | Li et al., 2010 [4] |

| L-glutamate (fed-batch fermentation) | 102.8 | 3.0 | Li et al., 2010 [10] | ||

| TCCC13007 | Isolated from pickles | MSG (2-step fermentation) | 61 | 3.0 | Zhang et al., 2012 [8] |

| E. coli | gadB (L. lactis) | MSG | 76.2 | 1.5 | Park et al., 2013 [11] |

| C. glutamicum | gadRCB2 (L. brevis) | Glucose | 2.15 | 0.02 | Shi et al., 2011 [12] |

| gadB (E. coli) | Glucose | 12.3 | 0.02 | Takahashi et al., 2012 [13] | |

| gadB1B2 (L. brevis) | Glucose, urea | 27.1 | 1.2 | Shi et al., 2013 [14] | |

| ΔpknG, gadB (E. coli) | Glucose | 31.1 | 0.02 | Okai et al., 2014 [15] |

Corynebacterium glutamicum is an important industrial microorganism because of its ability to produce high levels of L-glutamate, and recombinant strains of C. glutamicum that express GADs from L. brevis [12,14] or Escherichia coli [13] produce GABA from glucose (Table 2). Disrupting the gene that encodes protein kinase G affects the function of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase in the TCA cycle, alters metabolic flux toward glutamate [16], and enhances the yields of GABA produced by a GAD-expressing strain of C. glutamicum [15]. Because C. glutamicum is generally recognized as safe, the system for GABA fermentation can be applied to the production of GABA as a component of food additives and pharmaceuticals.

Isoprenoids

Isoprenoids represent the most diverse group of natural products comprising more than 40,000 structurally distinct compounds that are present in all classes of living organisms. These molecules play key roles in respiration and electron transport, maintenance of membrane fluidity, hormone signaling, photosynthesis, antioxidation as well as subcellular localization and regulation of protein activities [17]. Certain isoprenoids such as carotenoids are produced commercially as nutritional and medicinal additives [18].

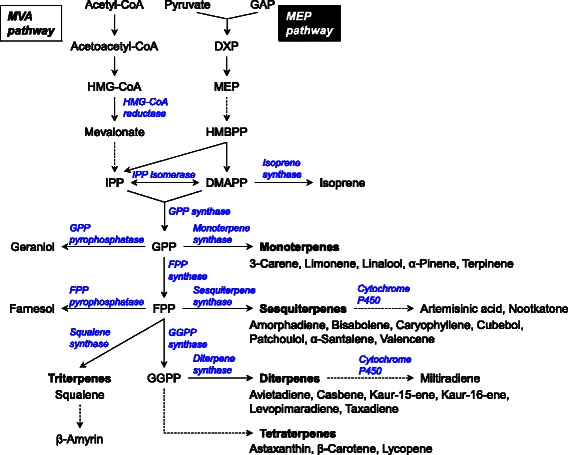

Despite their enormous structural diversity, isoprenoids are biologically synthesized through consecutive condensations of five-carbon precursors, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP), and its allyl isomer dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) (Figure 2). IPP and DMAPP are synthesized via either the mevalonate (MVA) pathway in most eukaryotes or the 2-C-methyl-D-erythrito-l,4-phosphate (MEP) pathway in prokaryotes. In higher plants, the MVA and MEP pathways function in the cytosol and plastid, respectively [19-21]. The five-carbon precursors are condensed by prenyltransferase to form prenyl pyrophosphates such as geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP), farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP), and several polyprenyl pyrophosphates [17]. The prenyl pyrophosphates are converted into monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, diterpenes, triterpenes, tetraterpenes, and polyprenyl side chains. The chemical diversity of isoprenoids is determined by specific terpene synthases and terpene-modifying enzymes, particularly cytochromes P450 [22].

Figure 2.

Biosynthetic pathway of isoprenoids produced by recombinant microorganisms. Abbreviations: DXP, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate; MEP, 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate; HMBPP, hydroxymethylbutenyl-4-diphosphate; IPP, isopentenyl diphosphate; DMAPP, dimethylallyl diphosphate; GPP, geranyl diphosphate; FPP, farnesyl diphosphate; GGPP, geranylgeranyl diphosphate; HMG-CoA, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA.

Various synthetic bioengineering approaches improve isoprenoid production by microorganisms such as E. coli and S. cerevisiae. Examples include the synthesis of triterpenoids amorpha-4,11-diene and artemisinic acid, precursors of the antimalarial agent artemisinin and the precursor of the major antineoplastic agent taxol diterpenoid taxa-4(5),11(12)-diene [23-31]. The tetraterpenoids (carotenoids) such as astaxanthin are also synthesized by synthetic bioengineering approaches [32,33].

Isoprene, the simplest isoprenoid, is used to synthesize pharmaceuticals, pesticides, fragrances, and synthetic rubber. E. coli strains engineered to express the Poplus alba gene (IspS) encoding isoprene synthase and the S. cerevisiae MVA pathway genes produce 532 mg/L of isoprene under fed-batch conditions [34]. A strain of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis, which was engineered to express IspS from kudzu, synthesizes isoprene photosynthetically [35].

Monoterpenes are used as aromatic additives in food, wine, and cosmetics. Certain monoterpenes exhibit antimicrobial, antiparasitic, and antiviral activities [36]. In S. cerevisiae, geraniol and linalool are produced from GPP by the expression of genes encoding geraniol synthase and linalool synthase (LIS), respectively [37-40]. Expression of the gene encoding Picea abies 3-carene cyclase in E. coli generates a range of monoterpenes, including α-pinene, myrcene, sabinene, 3-carene, γ-terpinene, limonene, β-phellandrene, α-terpinene, and terpinolene [41].

Sesquiterpenes exhibit anticancer, cytotoxic, and antibiotic properties as well as their characteristic flavors and aromas, making them industrially relevant compounds [17]. Valencene, cubebol, patchoulol, and α-santalene are produced by expressing heterologous sesquiterpene synthase genes in S. cerevisiae [42-47]. Coexpression of the genes encoding valencene synthase gene and a P450 mono-oxygenase in S. cerevisiae generates nootkatone that is industrially produced as a flavoring agent and fragrance [48]. The diterpenoid levopimaradiene is produced at high yield (700 mg/L) through combinatorial protein engineering of plant-derived GGPP synthase and levopimaradiene synthase expressed by an E. coli strain with enhanced carbon flux toward IPP and DMAPP [49]. Miltiradiene, the precursor of tanshinones that belongs to a group of bioactive diterpenoids present in the Chinese medicinal herb Salvia miltiorrhizha, accumulates in a S. cerevisiae strain that expresses genes encoding S. miltiorrhiza copalyl diphosphate synthase and kaurene synthases homolog [50,51]. Few attempts were made to metabolically engineer triterpene production, because the genes encoding components of its biosynthetic pathway are unknown; Kirby et al. isolated a gene encoding β-amyrin synthase from Artemisia annua and used it to produce β-amyrin in S. cerevisiae [52].

Elevating the levels of precursor pools based on improving carbon flux are efficient strategies to enhance isoprenoid production by recombinant microbial strains (Table 3). Scalcinati et al. adopted multiple metabolic engineering strategies for α-santalene production that were designed to increase precursor and cofactor supply by improving metabolic flux toward FPP and modifying the ammonium assimilation pathway, respectively [45,46]. The gene encoding 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase lacking its transmembrane region was expressed to avoid feedback regulation by sterols [45,46]. Repression of ERG9 that encodes squalene synthase and the deletion of LPP1 and DPP1 that encode enzymes that dephosphorylate FPP minimized the formation of by-products such as sterols and farnesol. Efficient provision of acetyl-CoA, the precursor of the MVA pathway, was critical to improve α-santalene synthesis [47].

Table 3.

Strategies of synthetic bioengineering for the microbial production of isoprenoids

| Compounds | Host strains | Genetic engineering a | Strategy for flux control | Titer | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoprene | E. coli | He: B. subtilis dxs, dxr and P. alba IspS | -Improvement of MEP pathway flux | 314 mg/L | Zhao et al., 2011 [30] |

| E. coli | He: P. alba IspS | -Integration of heterologous MVA pathway | 532 mg/L | Yang et al., 2012 [34] | |

| Oe: MVA pathway genes | |||||

| Monoterpene | |||||

| Carene | E. coli | He: H. pluvialis IPI isomerase and P. abies 3- carene cyclase genes | -Improvement of flux toward GPP | 3 μg/L/OD600 | Reiling et al., 2004 [41] |

| Oe: dxs, IspA variant | |||||

| Geraniol | S. cerevisiae | He: O. basiilcum geraniol synthase gene | -Repression of FPP synthesis | 5 mg/L | Fischer et al., 2011 [40] |

| Mu: ERG20 | |||||

| Linalool | S. cerevisiae | He: C. breweri LIS | -Improvement of MVA pathway flux | 132.66 μg/L | Rico et al., 2010 [39] |

| Oe: tHMG1 | |||||

| Sesquiterpene | |||||

| Artemisinic acid (Amorpha-4,11-diene) | E. coli | He: S. cerevisiae HMGS, tHMG1, ERG12, ERG8, MVD1, H. pluvialis ispA and A. annua ADS | -Integration of heterologous MVA pathway | 111.2 mg/L | Martin et al., 2003 [53] |

| -Overexpression of FPP synthase gene | |||||

| Oe: atoB and idi | |||||

| S. cerevisiae | He: A. annua ADS and CYP71AV1 | -Overexpression of tHMGR and FPP synthase genes | 153 mg/L | Ro et al., 2006 [54] | |

| Oe: tHMG1, ERG20 and Upc2-1 | |||||

| -Up regulation of global transcription activity | |||||

| Dr: ERG9 | |||||

| -Repression of squalene synthesis | |||||

| He: A. annua ADS, CYP71AV1, CPR1, CYB5, ALDH1 and ADH1 | -Integration of heterologous MVA pathway | 25 g/L | Paddon et al., 2013 [55] | ||

| -Overexpression of tHMGR and FPP synthase genes | |||||

| -Repression of | |||||

| squalene synthesis | |||||

| Oe: MVA pathway genes, tHMGR, and ERG20 | |||||

| Dr: ERG9 | |||||

| Levopi-maradiene | E. coli | He: G. biloba GGPPS and LPS | -Improvement of flux toward IPP/DMAPP | 700 mg/L | Leonard et al., 2010 [49] |

| Oe: dxs, idi, ispD and ispF | -Combinatorial mutation in GGPP synthase and LPS | ||||

| Patchoulol | S. cerevisiae | Oe: S. cerevisiae FPPS/P. cablin PTS (chimera) | -Avoidance of intermediate loss | 40.9 mg/L | Albertsen et al., 2011 [43] |

| -Repression of squalene synthesis | |||||

| Dr: ERG9 | |||||

| α-Santalene | S. cerevisiae | He: C. lansium santalene synthase | -Overexpression of tHMGR and FPP synthase | 92 mg/L | Scalcinati et al., 2012 [42] |

| Oe: tHMG1, FPPS, GDH2 and Upc2-1 | |||||

| -Increment of cofactor supply | |||||

| Dr: ERG9 | |||||

| De: GDH1, LPP1, DPP1 | -Up regulation of global transcription activity | ||||

| -Repression of squalene synthesis | |||||

| -Minimization of flux toward farnosol | |||||

| He: C. lansium santalene synthase | -Improvement of flux toward acetoacetyl-CoA from ethanol | 8.3 mg/L | Chen et al., 2013 [44] | ||

| -Avoidance of acetyl-CoA consumption | |||||

| Oe: Adh2, Ald6, ACS variant, Erg10 and tHMG1 | |||||

| De: CIT2 and MLS1 | |||||

| Valencene | S. cerevisiae | He: A. thaliana FPP synthase and C. sinensis TPS1 genes in mitochondria | -Overexpression of tHMGR | 1.5 mg/L | Farhi et al., 2011 [44] |

| -Mitochondrial expression of FPP synthase and valencene synthase genes | |||||

| Oe: tHMG1 | |||||

| Diterpene | |||||

| Casbene | E. coli | Oe: dxs, IspA variant | -Improvement of flux toward GGPP | 0.3 mg/L | Reiling et al., 2004 [41] |

| He: H. pluvialis IPI isomerase and R. communis casbene cyclase genes | |||||

| Miltiradiene | S. cerevisiae | He: S. acidocaldarium GGPPS and S. miltiorrhizha CPS and KSL | -Overexpression of tHMGR, FPP synthase and GGPP synthase genes | 8.8 mg/L | Dai et al., 2012 [47] |

| Oe: tHMG1, ERG20, BTS1 and Upc2-1 | -Up regulation of global transcription activity | ||||

| Taxadiene | E. coli | He: S. acidocaldariums GGPP synthase and T. chinensis taxadiene synthase genes | -Improvement of MEP pathway flux | 1 g/L | Ajikumar et al., 2010 [24] |

| -Overexpression of GGPP synthase | |||||

| Oe: dxs, ispC, ispF, idi, tHMG1 and Upc2-1 | |||||

| S. cerevisiae | He: S. acidocaldariums GGPP synthase and T. chinensis taxadiene synthase genes | -Overexpression of tHMGR | 8.7 mg/L | Engels et al., 2008 [31] | |

| -Up regulation of global transcription activity | |||||

| Oe: tHMG1 and Upc2-1 | |||||

| Triterpene | |||||

| β-Amyrin | S. cerevisiae | Oe: tHMG1 | -Overexpression of tHMGR | 6 mg/L | Kirby et al., 2008 [52] |

| He: A. annua β-amyrin synthase gene | |||||

| -Repression of lanosterol synthesis | |||||

| Dr: ERG7 |

aTypes of genetic engineering: He, Heterologous expression; Oe, Overexpression of self-cloning gene(s); Dr, down regulation; De, Deletion; Mu, Mutation.

Aromatics

Aromatic compounds such as vanillin, cinnamic acid, p-hydroxycinnamic acid, and caffeic acid are used as flavoring agents or food ingredients (Table 4). Vanillin, which was originally extracted from cured seed pods of the orchid Vanilla planifolia, is mainly synthesized from petroleum oil or lignin. Alternatively, vanillin is produced by bioconversion of fossil carbon, guaiacol, eugenol, or isoeugenol [56]. Vanillin was produced from glucose by fermentation using an engineered strain of barker’s yeast [57]. To decrease the cytotoxic effects of converting intercellular 3-dehydroshikiminate to vanillin, genes encoding UDP-glucose transferase and o-methyltransferase were introduced into baker’s yeast to produce vanillyl glucoside (VG) [58]. Further, the Minimization of Metabolic Adjustments (MOMA) [59] and OptGene [60] algorithms were used to improve VG production in yeast strains [58,61].

Table 4.

Microbial fermentation of aromatic compounds

| Compounds | Strains | Genetic engineering a | Substrates | Yield (g/L) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanillin | S. pombe | He: 3-dehydroshikiminate dehydratase (3DSD), Aryl carboxylic acid reductase (ACAR, Nocardia sp.), o-methyltransferase (OMT), UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGT, A. thaliana) | Glucose | 0.065 | Hansen et al., 2009 [51] |

| S. cervisiae | He: 3DSD, ACAR, OMT, UGT | ||||

| Vanillin β-D-glucoside | S. cervisiae | He: 3DSD, ACAR, phosphopantetheine transferase (PPTase), hsOMT (Homo sapiens), UGT | Glucose | 0.5 | Brochado et al., 2010 [52] |

| De: pdc1gdh1↑GDH2 | |||||

| S. cervisiae | He: ACAR, hsOMT, | Glucose | 0.38 | Brochado et al., 2013 [58] | |

| Oe: GDH2 | |||||

| De: pdc1 gdh1 yprC | |||||

| Cinnamic acid | P. putida | He: Phenylalanine ammmonia lyase (PAL, Rhodosporidium toruloides) | Glucose | 0.74 | Nijkamp et al., 2005 [62] |

| Glycerol | 0.8 | ||||

| S. lividans | He: PAL (Streptomyces maritimus) | Glucose | 0.12 | Noda et al., 2011 [60] | |

| Starch | 0.46 | ||||

| Xylose | 0.3 | ||||

| Xylan | 0.13 | ||||

| p-hydroxycinnamic acid (p-coumaric acid) | S. cervisiae | He: PAL/TAL (Rhodotorula glutinis), plant Cytochrome P450 (Cyt P450), Cyt reductase | Glucose | Vannelli et al., 2007 [62] | |

| E. coli | He: PAL/TAL (R. glutinis) | 0.10 | |||

| S. lividans | He: Tyrosine ammmonia lyase (TAL, Rhodobacter sphaeroides) | Glucose | 0.75 | Kawai et al., 2013 [63] | |

| Cellobiose | 0.74 | ||||

| He: TAL (R. sphaeroides), Endoglucanase (Thermobifida fusca) | PASC | 0.5 | |||

| P. putida | He: PAL (Rhodosporidium toruloides) | Glucose | 1.7 | Nijkamp et al., 2007 [64] | |

| Mu: phenylalanine bradytrophic | |||||

| De: fcs | |||||

| E. coli | He: TAL (Saccharothrix espanaensis) | Glucose | 0.97 | Kang et al., 2012 [65] | |

| Mu: tyrA fbr aroG fbr | |||||

| De: tyrR | |||||

| Caffeic acid | E. coli | He: Cyt P450 (Rhodopseudomonas palustris) | p-hydroxycinnamic acid | 2.8 | Furuya et al., 2012 [66] |

| He, Mu: Cyt P450 | Cinnamic acid | ||||

| He: TAL, 4-coumarate hydroxylase (Sam5, S. espanaensis), | Glucose | 0.15 | Kang et al., 2012 [65] | ||

| Mu: tyrA fbr aroG fbr | |||||

| De: tyrR | |||||

| He: TAL (R. glutinis codon-optimized), 4-coumarate: CoA ligase (4CL), 4-coumarate 3-hydroxylase (Coum3H, S. espanaensis) | Glucose | 0.10 | Zhang et al., 2013 [67] | ||

| Xylose | 0.07 | ||||

| Mu: tyrA fbr aroG fbr | |||||

| De: tyrR pheA | |||||

aTypes of genetic engineering: He, Heterologous expression; Oe, Overexpression of self-cloning gene(s); Mu, Mutation; De, Deletion.

Cinnamic acid is used as a cinnamon flavoring agent and is antibacterial. Although cinnamic acid occurs abundantly in plants as a precursor of phenylpropanoids, it is produced industrially using synthetic organic chemistry. Cinnamic acid is produced from sugar by phenylalanine-ammonia lyase (PAL, EC 4.3.1.24) expressed in a solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida strain [62] or by Streptomyces lividans, which is an ideal host, because its endogenous polyketide synthesis (PKS) pathways synthesize phenylpropanoids [64]. A phenylpropanoid, p-hydroxycinnamic acid (p-coumaric acid), a constituent of the plant cell wall, which is covalently linked to polysaccharides and lignins, acts as an antioxidant in humans [63]. E. coli and S. cerevisiae strains engineered to express PAL/tyrosine-ammonia lyase (TAL, EC 4.3.1.23) [68] or P. putida engineered to express PAL [69] produce p-hydroxycinnamic acid from glucose. Further, p-hydroxycinnamic acid can be produced from cellulose by S. lividans coexpressing TAL and endoglucanase (EG, EC 3.2.1. 4) [70].

Alkaloids

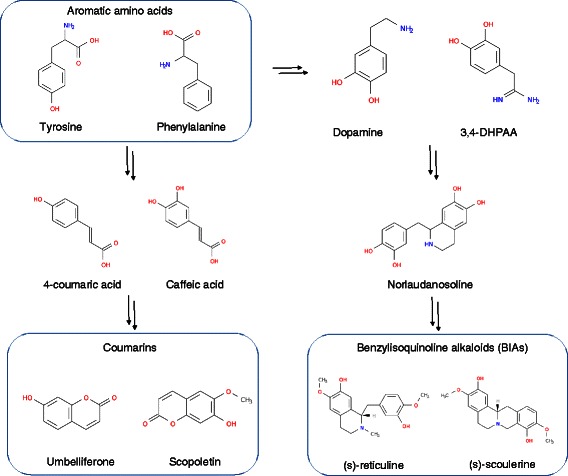

Alkaloids are nitrogen-containing compounds derived from amino acids such as histidine, lysine, ornithine, tryptophan, and tyrosine [71] that are present in plants. Most are used in biological and medicinal applications. They are mainly extracted from plants for practical use, but the yields are very low because low levels of alkaloids are produced by plants. Further, alkaloids consist of complex chemical backbones and structures with one or more chiral centers, which make it difficult to supply sufficient amounts of alkaloids for practical use through chemical synthesis. Therefore, development of alternative approaches is expected to characterize and engineer the biosynthetic pathways in microbial and plant cells. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIAs) such as (s)-reticuline and (s)-scoulerine, which are categorized into one of the major alkaloid subclasses, include the analgesics codeine and morphine, the antimicrobial berberine, and the anticancer drug noscapine (Figure 3 right). Both (s)-reticuline and (s)-scoulerine are synthesized through the production of (R, S)-norlaudanosoline from aromatic amino acids (tyrosine and phenylalanine). The increasing volume of information on the genome sequences of alkaloid-producing plants makes it possible to identify and engineer genes in biosynthetic pathways to produce BIAs in E. coli [72,73] and S. cerevisiae [74] through the production of (R, S)-norlaudanosoline from aromatic amino acids.

Figure 3.

Production of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIAs) and coumarins from aromatic amino acids. BIAs and coumarins are synthesized from aromatic amino acids (tyrosine and phenylalanine) through corresponding intermediates.

Minami et al. reconstructed the (S)-reticuline biosynthetic pathways in E. coli using monoamine oxidase (MAO) from Micrococcus luteus and four genes from Coptis japonica to produce (S)-reticuline from dopamine. They introduced the genes encoding BBE (berberine bridge enzyme) and CYP80G2 (plant cytochrome P450 enzyme) of C. japonica into S. cerevisiae, because active forms of certain plant enzymes cannot be expressed in E. coli. S. cerevisiae provides the advantage of compartmentalizing these proteins in the cytosol and endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The engineered S. cerevisiae is co-cultured with E. coli to produce BIA derivatives (S)-scoulerine and magnoflorine. Nakagawa et al. engineered the shikimate (SK) pathway in E. coli to increase the amount of L-tyrosine and produced (S)-reticuline from glucose or glycerol [73]. The BIA pathways downstream of the precursor (R, S)-norlaudanosoline were assembled in S. cerevisiae [74]. The expression levels of norcoclaurine 6-O-methyltransferase (6-OMT), coclaurine-N-methyltransferase (CNMT), and 3′-hydroxy- N-methylcoclaurine 4′-O-methyltransferase (4′-OMT), and a hydroxylation reaction catalyzed by cytochrome P450 80B1 (CYP80B1) derived from Thalictrum flavum or Papaver somniferum were optimized to produce (S)-reticuline. A human cytochrome P450 (CYP2D6) was expressed as well to produce the morphinan intermediate salutaridine [71]. Most recently, 10 genes from plant BIA pathways were introduced into S. cerevisiae to produce dihydrosanguinarine and its oxidized derivative sanguinarine from (R,S)-norlaudanosoline [75].

Coumarins are present in plants and are used as antibacterials, anticancer drugs, and anticoagulants. The biosynthetic pathways of coumarins diverge from that of phenylalanine/tyrosine as well as BIA (Figure 3 left). Recent findings that coumarin is formed by the action of two hydroxylases allowed reconstruction of its biosynthetic pathway in microbial cells. Lin et al. designed artificial biosynthetic pathways in E. coli [76] and produced scopoletin and umbelliferone from the corresponding phenylpropanoid acids, ferulic acid, caffeic acid, and 4-coumaric acid. They used TAL to produce scopoletin and umbelliferone from aromatic amino acids. Further work was extended to identify a β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III-like quinolone synthase from P. aeruginosa that contributes to the biosynthesis of high levels of 4-hydroxycoumarin by E. coli [77].

Peptides

Enzymatic hydrolysis of proteins generates mixtures of peptides. In contrast, purified carnosine (β-alanine-L-histidine) and antimicrobial peptides (e.g. gramicidin S, actinomycin, polymixin B, and vancomycin) are prepared from organisms that contain higher amounts compared with other organisms [78] (Table 5). Carnosine is synthesized from H-β-Ala-NH2 using β-aminopeptidase expressed by E. coli and Pichia pastoris [79]. Physiologically active polypeptides such as ε-poly-L-lysine (ε-PL) and poly-γ-glutamic acid (γ-PGA) are produced by microbial fermentation. ε-PL is characterized by the peptide bond between the α-carboxyl and ε-amino groups of 25–35 L-lysine residues [80] and is produced by secretory fermentation of Streptomyces strains isolated from soil [81]. The yield of ε-PL was enhanced using genome shuffling [82]. γ-PGA is an unusual anionic polypeptide comprising D/L-glutamate monomers polymerized through γ-glutamyl bonds [83]. γ-PGA is produced by Bacillus strains from glutamate or glucose [84,85]. B. subtilis was engineered to increase γ-PGA production by overexpression of γ-PGA synthetase [86] or by deletion of γ-PGA-degrading enzymes [87]. B. amyloliquefaciens was engineered to enhance γ-PGA production by heterologous expression of the Vitreoscilla gene (vgd) encoding hemoglobin to overcome the low concentration of dissolved oxygen [67,88]. In contrast, Chao et al. developed a γ-PGA-producing E. coli strain by heterologous expression of γ-PGA synthetase and glutamate racemase from B. licheniformis or B. amyloliquefaciens [89].

Table 5.

Enzymatic conversion and microbial fermentation of peptides

| Compounds | Strains | Types a | Genetic engineering b | Substrates and components | Maximum yield | Scale | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carnosine | E. coli or Pichia pastoris | E | He: Ochrobactrium anthropi β-aminopeptidase or Sphingosinicella xenopeptidilytica L-aminopeptidase- | H-β-Ala-NH2 | 4.5 g/L | 200 mL | Heyland et al., 2010 [79] |

| D-amidase | |||||||

| ε-poly-lysine (εPL) | Streptomyces strains | F | He: Genome shuffling | Glucose | 24.5 g/L | 3 L | Li et al., 2013 [82] |

| poly-gamma-glutamate (γ-PGA) | Bacillus subtilis | F | Oe: γ-PGA synthetases | Xylose | 9.0 g/L | 50 mL | Ashiuchi et al., 2006 [86] |

| Arabinose | |||||||

| Glutamate | |||||||

| F | De: γ-PGA degradation enzymes | Glutamate | 48 g/L | 20 mL | Scoffone et al., 2013 [87] | ||

| Bacillus amyrolique-haciens | F | He: Vitreoscilla hemoglobin | Sucrose | 3.5 g/L | 100 mL | Zhang et al., 2013 [67] | |

| F | He: Vitreoscilla hemoglobin | Sucrose | 5.1 g/L | 100 mL | Feng et al., 2014 [88] | ||

| De: cwlO and epsA-O cluster | |||||||

| E. coli | F | He: Β. licheniformis γ-PGA synthetases, glutamate racemase | Glutamate | 0.65 g/L | 100 mL | Cao et al., 2013 [89] | |

| F | He: Β. amyloliquefaciens γ-PGA synthetases, glutamate racemase | Glucose | 0.52 g/L | 100 mL | |||

| Glutathione | E. coli | E | De: Single genes related to ATP regenerating activity | Glucose, Glutamate, Cysteine, Glycine | 2.9 g/L | 1 mL | Hara et al., 2009 [90] |

| S. cerevisiae | E | Oe: GCS, GS | Glucose, Glutamate, Cysteine, Glycine | 0.8 g/L | 20 mL | Yoshida et al., 2011 [91] | |

| S. cerevisiae | F | Oe: GCS | Glucose | 168 nmol/OD600 | 300 mL | Suzuki et al., 2011 [92] | |

| De: pep12 | |||||||

| S. cerevisiae | F | Oe: GCS, Sulfate assimilation pathway genes | Glucose | 43.9 mg/L | 20 mL | Hara et al., 2012 [93] | |

| Alanyl-glutamine | E. coli | E | He: B. subtilis L-amino acid α-ligase | Alanine, Glutamate | 4.7 g/L | 1 mL | Tabata et al., 2005 [94] |

| E. coli | F | He: B. subtilis L-amino, α-ligase, L-alanine dehydrogenase | Glucose | 24.7 g/L | 2 L | Tabata et al., 2007 [95] | |

| De: dipeptidases, aminopeptidases | |||||||

| E. coli | E | He: Sphingobacterium siyangensis α-amino acid ester acyltransferase | L-alanine methyl ester hydrochlorid, Glutamine | 79.3 g/L | 300 mL | Hirao et al., 2013 [96] | |

| Dipeptides | E. coli | E | He: Ralstonia solanacearum RSp1486a | Amino acids, ATP, MgSO4 | 2.9 g/L (Phe-Cys) | 500 μL | Kino et al., 2008a [97] |

| E | He: B. licheniformis BL00235 | Amino acids, ATP, MgSO4 | 1.2 g/L (Met-Ala) | 1.6 mL | Kino et al., 2008b [98] | ||

| E | He: B. subtilis RizA | Amino acids, ATP, MgSO4 | 0.8 g/L (Arg-Ser) | 300 μL | Kino et al., 2009 [99] |

aProduction types: E, Enzymatic production including permeable cell conversion; F, Fermentation.

bTypes of genetic engineering: He, Heterologous expression; Oe, Overexpression of self-cloning gene(s); De, Deletion.

The tri-peptide glutathione, which is the most abundant antioxidant, thiol-containing compound among organisms [100], is produced enzymatically and by microbial fermentation. Glutathione is synthesized from glucose via glutamic acid, cysteine, and glycine through two consecutive ATP-consuming reactions catalyzed by ATP consuming two enzymes: γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (GCS) and glutathione synthetase (GS). Enzymatic conversion of these substrates to glutathione was developed using permeabilized S. cerevisiae or E. coli overexpressing GCS and GS [91,101,102]. ATP regeneration is critical for improving the yields of glutathione, and a permeable cellular ATP-regenerating system was studied to provide an economical supply of ATP [101]. However, the efficiency of ATP regeneration for glutathione production is low [101]. To address this problem, the products of genes that increase ATP regeneration were systematically identified by generating E. coli mutants each with single deletions of nlpD, miaA, hcp, tehB, nudB, glgB, yggS, pgi, fis, add, rfaB, ydhL, or ptsP [90] from a single-gene deletion mutant library using high-throughput measurements of ATP regenerating activity [103]. Certain deletion mutants synthesized increased levels of glutathione [102]. These genes were classified into the following groups: (1) glycolytic pathway-related genes, (2) genes related to degradation of ATP or adenosine, (3) global regulatory genes, and (4) genes with unknown contributions to ATP regeneration. In contrast, improving ATP generation enhanced the enzymatic synthesis of glutathione by S. cerevisiae of about 1.7-fold [91]. Industrial glutathione production mainly uses yeast fermentation, because enzymatic synthesis of glutathione requires addition of substrates. Overexpression of GCS is critical for enhancing glutathione fermentation [92,93]. Enhancement of cysteine synthesis by engineering of sulfate metabolism also improved glutathione production [93]. In contrast, the overexpression of the transcription factors YAP1 and MET4 increased glutathione production [104-106]. Kiriyama et al. developed a fermentation system to efficiently produce extracellular glutathione by overexpression of a novel glutathione export ABC protein (Adp1p, Gxa1p) in S. cerevisiae [107].

A dipeptide L-alanyl-L-glutamine was enzymatically produced by Sphingobacterium siyangensis α-amino acid ester acyltransferase from L-alanine methyl ester hydrochlorid and glutamine [96]. Α Bacillus subtilis α-dipeptide synthase processing specificity for L-amino acids was discovered by Tabata et al. through in silico screening based on its amino acids similarity with members of the carboxylate-amine/thiol ligase superfamily, such as those that catalyze the synthesis of D-alanyl-D-alanine and γ-peptides [94]. They searched for the presence of an ATP grasp motif encoded by functional unknown genes in B. subtilis, because this motif is present in all enzymes of this superfamily [108,109] and showed that YwfEp exhibited dipeptide synthesis activity [94]. A variety of dipeptide synthases were subsequently identified using in silico screening based on amino acid sequence similarities to YwfEp [97-99]. Such screening approaches are useful for identifying peptide synthases with different substrate specificities. A microbial dipeptide fermentation system was developed by introducing the gene encoding YwfEp into E. coli and achieved [95].

Polyphenols

Polyphenols such as phenolic acids, stilbenes, and flavonoids are secondary metabolites present in plants [110]. Polyphenols were traditionally extracted from plant sources using solvents or were chemically synthesized. Moreover, these methods are expensive and may be detrimental to the environment [111]. Recently, a metabolic engineering approach makes possible effective production of bio-based polyphenols. Phenolic acids are simple polyphenols. For example, ferulic acid and caffeic acid are produced by genetically engineered E. coli strains [65,112] (see “Aromatics” section). These phenolic acids, which form the skeletal structures of complex polyphenols, stilbenes, and flavonoids are biosynthesized through further genetic engineering (see [113] for an excellent review).

The biosynthetic pathway of the complex polyphenols requires coenzyme A (CoA)-esterified cinnamates and malonyl-CoA. Recently, the stilbene resveratrol was biosynthesized at high yields (2.3 g/L) by an E. coli strain [114] that was genetically engineered to enhance the production of malonyl-CoA to increase the supply of malonyl-CoA, which is used to synthesize fatty acids (see [115] for a review). Such metabolic engineering may further improve production. For example, the shikimic acid pathway, which produces phenylalanine and tyrosine as starting materials in the de novo production of polyphenols, would serve as a target. Actinomycetes may serve as useful hosts for producing aromatic amino acids. Further, Aspergilli, for which genetic engineering tools are available, may serve as promising hosts for producing antibacterial polyphenols, because Aspergillus oryzae was used to produce fine chemicals [116,117].

In general, producing high yields of polyphenols by microorganisms is difficult, because these compounds are strong antioxidants, and some are antibacterials, antifungals, or both [118]. Therefore, further improvements require using insensitive hosts and the development of an on-site recovery method for continuous fermentation. A membrane-purification process, which concentrates a target compound, would be implemented in such an on-site recovery and fermentation system. The combination of bio-based and engineering-based improvements would be required for producing high yields of polyphenols.

Oligosaccharides

Oligosaccharides and rare sugars derived from the hydrolysis of plant polysaccharides are functionally diverse. Such oligosaccharides are categorized according to their monosaccharide subunits. For example, fructo-, xylo-, and gentio-oligosaccharides consist of short chains of fructose, xylose, and glucose, respectively, and are produced by enzymatic hydrolysis of extracts of natural sources, because they are difficult to synthesize de novo using microorganisms. For example, xylo-oligosaccharides are produced from xylan by enzymatic hydrolysis [119,120]; however, the quality and quantity of products strongly depend on the source compared with de novo synthesis.

Because of this, bio-based fermentation is under study. For example, the thermophilic fungus Sporotrichum thermophile and a genetically engineered E. coli strain produce fructo-oligosaccharides [121] and inulo-oligosaccharides (derived from insulin) [122], respectively. These bioconversions are advantageous, because the host cells do not metabolize the oligosaccharide products. Moreover, the specific functional monosaccharide L-arabinose was prepared from xylose [123]. Further, the microbial fermentation of 2′-fucosyllactose from lactose by a genetically engineered E. coli strain has been reported [124]. 2′-Fucosyllactose is a functional oligosaccharide present in human milk and protects newborns against infection by enteric pathogens [125].

The production of oligosaccharides requires the decomposition of polysaccharides or the polymerization of monosaccharides. Polymer-producing microorganisms would serve as promising hosts in a strategy based on the decomposition of polysaccharides. For example, the halophilic cyanobacterium Arthrospira platensis produces spirulan, which is an inhibitor of enveloped virus replication [126]. Moreover, it produces glycogen by fixing carbon dioxide, and the glycogen content reaches 65% of dry cell weight under optimum conditions [127]. Such photosynthetic microorganisms would serve as promising hosts for the de novo production of oligosaccharides. Specifically, the genetic engineering of microorganisms that produce polysaccharide-degrading enzymes, glycosyltransferases, or both may facilitate attaining this goal. In addition to fermentation, such polysaccharide-accumulating microorganism would be useful as a sugar source for bio-based production. In the future, combinations of polysaccharide-producing microorganism and decomposing, transferase-producing microorganism, or both would improve the bio-based production of oligosaccharides.

Conclusion and future perspectives for the production of fine chemicals

Synthetic bioengineering employs molecular genetic approaches to engineer metabolic pathways to enhance the biosynthetic capabilities of well-characterized host strains to produce fine chemicals. These efforts include identifying the genes in plants and microbes encoding enzymes that catalyze the reactions of interest. Converting bio-based production of fine chemicals from enzymatic reactions to microbial fermentation reduces costs, because the latter uses less expensive substrates. Computational approaches are essential for synthetic bioengineering to increase yields, and an important aspect of designing strategies is to identify the initial key enzymatic reactions of a biosynthetic pathway (Figure 1). Using bioinformatics to mine genome and transcriptome data is the method of choice to identify novel enzymes and biosynthetic pathways to generate a wide range of compounds [128,129]. Sequence comparisons of putative and authentic genes allow the prediction of catalytic homologs and motifs with potentially new functions. Structural analyses such as active site modeling and docking simulation are alternative approaches. The availability of high-throughput sequencing technology and improved computational resources should accelerate synergy between bioinformatics and structural analyses to identify key enzymes from the vast reservoir of genetic and environmental data [130,131].

Once key enzymes are identified, one can move to pathway design and optimization for microbial production of the target compound. Several computational tools are available, such as BNICE [132], FMM [133], RetroPath [134], and DESHARKY [135] and M-path [136] for designing de novo metabolic pathways. These resources provide different views of metabolic pathways for microbial production that are generated using the enormous amount of information in metabolic pathway databases such as KEGG [137], MetaCyc [138] and BRENDA [139].

However, there are still limitations because of the computational complexity of possible combinations, and further improvements or other approaches will be required for precise and practical design of metabolic pathways. A standard method to optimize metabolic pathways is available as an alternative that is called flux balance analysis [140], which was developed to indicate how gene deletions and expression might be manipulated to distribute carbon toward chemicals of interest without inhibiting cell proliferation. Genome-scale models for some model organisms and an open-source platform (e.g. OptFlux) based on flux balance analysis allow the precise control of engineered metabolic pathways [141,142]. The extension of these tools will lead to further efficient production of fine chemicals by microbial cell factories.

Acknowledgements

This review was supported by the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology, Creation of Innovation Centers for Advanced Interdisciplinary Research Areas (Innovative Bioproduction Kobe), MEXT, Japan.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HKY wrote Abstract, Introduction, “Peptides” and “Conclusion and future perspectives for the production of fine chemicals” sections, and organized the manuscript. MA wrote “Alkaloids” and “Conclusion and future perspectives for the production of fine chemicals” sections. NO wrote “GABA” and “Aromatics” sections. SW wrote “Polyphenols” and “Oligosaccharides” sections. TH outlined the manuscript and wrote “Isoprenoids” section. AK reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Kiyotaka Y Hara, Email: kiyotaka.hara@dolphin.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Michihiro Araki, Email: araki@port.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Naoko Okai, Email: okai@port.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Satoshi Wakai, Email: wakaists@pegasus.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Tomohisa Hasunuma, Email: hasunuma@port.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Akihiko Kondo, Email: akondo@kobe-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Johnson ET, Schmidt-Dannert C. Light-energy conversion in engineered microorganisms. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:682–689. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fonda ML. L-Glutamate Decarboxylase from Bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1985;113:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(85)13005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayakawa K, Kimura M, Kasaha K, Matsumoto K, Sansawa H, Yamori Y. Effect of a gamma-aminobutyric acid-enriched dairy product on the blood pressure of spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive Wistar-Kyoto rats. Br J Nutr. 2004;92:411–417. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li HX, Cao YS. Lactic acid bacterial cell factories for gamma-aminobutyric acid. Amino Acids. 2010;39:1107–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang SY, Lu ZX, Lu FX, Bie XM, Jiao Y, Sun LJ, Yu B. Production of gamma-aminobutyric acid by Streptococcus salivarius subsp thermophilus Y2 under submerged fermentation. Amino Acids. 2008;34:473–478. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0544-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho YR, Chang JY, Chang HC. Production of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by Lactobacillus buchneri isolated from kimchi and its neuroprotective effect on neuronal cells. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;17:104–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komatsuzaki N, Kawamoto S, Momose H, Kimura T, Shima J. Production of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by Lactobacillus paracasei isolated from traditional fermented foods. Food Microbiol. 2005;22:497–504. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Song L, Gao Q, Yu SM, Li L, Gao NF. The two-step biotransformation of monosodium glutamate to GABA by Lactobacillus brevis growing and resting cells. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;94:1619–1627. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-3868-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li HX, Qiu T, Gao DD, Cao YS. Medium optimization for production of gamma-aminobutyric acid by Lactobacillus brevis NCL912. Amino Acids. 2010;38:1439–1445. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li HX, Qiu T, Huang GD, Cao YS. Production of gamma-aminobutyric acid by Lactobacillus brevis NCL912 using fed-batch fermentation. Microb Cell Factories. 2010;9:85. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park SJ, Kim EY, Noh W, Oh YH, Kim HY, Song BK, Cho KM, Hong SH, Lee SH, Jegal J. Synthesis of nylon 4 from gamma-aminobutyrate (GABA) produced by recombinant Escherichia coli. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2013;36:885–892. doi: 10.1007/s00449-012-0821-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi F, Li Y. Synthesis of gamma-aminobutyric acid by expressing Lactobacillus brevis-derived glutamate decarboxylase in the Corynebacterium glutamicum strain ATCC 13032. Biotechnol Lett. 2011;33:2469–2474. doi: 10.1007/s10529-011-0723-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi C, Shirakawa J, Tsuchidate T, Okai N, Hatada K, Nakayama H, Tateno T, Ogino C, Kondo A. Robust production of gamma-amino butyric acid using recombinant Corynebacterium glutamicum expressing glutamate decarboxylase from Escherichia coli. Enzym Microb Technol. 2012;51:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi F, Jiang J, Li Y, Xie Y. Enhancement of gamma-aminobutyric acid production in recombinant Corynebacterium glutamicum by co-expressing two glutamate decarboxylase genes from Lactobacillus brevis. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;40:1285–1296. doi: 10.1007/s10295-013-1316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okai N, Takahashi C, Hatada K, Ogino C, Kondo A. Disruption of pknG enhances production of gamma-aminobutyric acid by Corynebacterium glutamicum expressing glutamate decarboxylase. AMB Express. 2014;4:20. doi: 10.1186/s13568-014-0020-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niebisch A, Kabus A, Schultz C, Weil B, Bott M. Corynebacterial protein kinase G controls 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase activity via the phosphorylation status of the OdhI protein. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12300–12307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gershenzon J, Dudareva N. The function of terpene natural products in the natural world. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:408–414. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang MCY, Keasling JD. Production of isoprenoid pharmaceuticals by engineered microbes. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:674–681. doi: 10.1038/nchembio836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rohmer M, Knani M, Simonin P, Sutter B, Sahm H. Isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria: a novel pathway for the early steps leading to isopentenyl diphosphate. Biochem J. 1993;295:517–524. doi: 10.1042/bj2950517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuzuyama T, Seto H. Diversity of the biosynthesis of the isoprene units. Nat Prod Rep. 2003;20:171–183. doi: 10.1039/b109860h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter WN. The non-mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis. J Biol Cell. 2007;282:21573–21577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Misawa N. Pathway engineering for functional isoprenoids. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22:627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kein-Marcuschmer D, Ajikumar PK, Stephanopoulos G. Engineering microbial cell factories for biosynthesis of isoprenoid molecules: beyond lycopene. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ajikumar PK, Xiao WH, Tyo KEJ, Wang Y, Simeon F, Leonard E, Mucha O, Phon TH, Pfeifer B, Stephanopoulos G. Isoprenoid pathway optimization for taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli. Science. 2010;330:70–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1191652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keasling JD. Synthetic biology and the development of tools for metabolic engineering. Metab Eng. 2012;14:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westfall PJ, Pitera DJ, Lenihan JR, Eng D, Woolard FX, Regentin R, Horning T, Tsuruta H, Melis DJ, Owens A, Fickes S, Diola D, Benjamin KR, Keasling JD, Leavell MD, McPhee DJ, Renninger NS, Newman JD, Paddon CJ. Production of amorphadiene in yeast, and its conversion to dihydroartemisinic acid, precursor to the antimalarial agent artemisinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E111–E118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110740109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marienhagen J, Bott M. Metabolic engineering of microorganisms for the synthesis of plant natural products. J Biotechnol. 2013;163:166–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wriessnegger T, Pichler H. Yeast metabolic engineering - Targeting sterol metabolism and terpenoid formation. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52:277–293. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Pfeifer BA. Heterologous production of plant-derived isoprenoid products in microbes and the application of metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2014;19:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Y, Yang J, Qin B, Li Y, Sun Y, Su S, Xian M. Biosynthesis of isoprene in Escherichia coli via methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;90:1915–1922. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engels B, Dahm P, Jennewein S. Metabolic engineering of taxadiene biosynthesis in yeast as a first step toward Taxol (Paclitaxel) production. Metab Eng. 2008;10:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hara KY, Morita T, Endo Y, Mochizuki M, Araki M, Kondo A. Evaluation and screening of efficient promoters to improve astaxanthin production in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:6787–6793. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5727-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hara KY, Morita T, Mochizuki M, Yamamoto K, Ogino C, Araki M, Kondo A. Development of a multi-gene expression system in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Microbial Cell Factories. 2014;13:175. doi: 10.1186/s12934-014-0175-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, Zhao G, Sun Y, Zheng Y, Jiang X, Liu W, Xian M. Bio-isoprene production using exogenous MVA pathway and isoprene synthase in Escherichia coli. Bioresour Technol. 2012;104:642–647. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindberg P, Park S, Melis A. Engineering a platform for photosynthetic isoprene production in cyanobacteria, using Synechocystis as the model organism. Metab Eng. 2010;12:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bohlmann J, Keeling CI. Terpenoid biomaterials. Plant J. 2008;54:656–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herrero Ó, Ramón D, Orejas M. Engineering the Saccharomyces cerevisiae isoprenoid pathway for de novo production of aromatic monoterpens in wine. Metab Eng. 2008;10:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oswald M, Fischer M, Dirninger N, Karst F. Monoterpenoid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007;7:413–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rico J, Pardo E, Orejas M. Enhanced production of a plant monoterpene by overexpression of the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase catalytic domain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:6449–6454. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02987-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischer MJC, Meyer S, Claudel P, Bergdoll M, Karst F. Metabolic engineering of monoterpene synthesis in yeast. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:1883–1892. doi: 10.1002/bit.23129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reiling KK, Yoshikuni Y, Martin VJJ, Newman J, Bohlmann J, Keasling JD. Mono and Diterpene production in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;87:200–212. doi: 10.1002/bit.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asadollahi MA, Mauri J, Møller K, Nielsen KF, Schalk M, Clark A, Nielsen J. Production of plant sesquiterpenes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Effect of ERGp repression on sesquiterpene biosynthesis. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;99:666–677. doi: 10.1002/bit.21581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albertsen L, Chen Y, Bach LS, Rattleff S, Maury J, Brix S, Nielsen J, Mortensen UH. Diversion flus toward sesquiterpene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by fusion of host and heterologous enzymes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:1033–1040. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01361-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farhi M, Marhevka E, Masci T, Marcos E, Eyal Y, Ovadis M, Abeliovich H, Vainstein A. Harnessing yeast subcellular compartments for the production of plant terpenoids. Metab Eng. 2011;13:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scalcinati G, Knuf C, Partow S, Chen Y, Maury J, Schalk M, Daviet L, Nielsen J, Siewers V. Dynamic control of gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae engineered for the production of plant sesquiterpene α-santalene in a fed-batch mode. Metab Eng. 2012;14:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scalcinati G, Partow S, Siewers V, Schalk M, Daviet L, Nielsen J. Combined metabolic engineering of precursor and co-factor supply to increase α-santalene production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:117. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Y, Daviet L, Schalk M, Siewers V, Nielsen J. Establishing a platform cell factory through engineering of yeast acetyl-CoA metabolism. Metab Eng. 2013;15:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cankar K, van Houweligen A, Bosch D, Sonke T, Bouwmeester H, Beekwilder J. A chicory cytochrome P450 mono-oxygenase CYP71AV8 for the oxidation of (+)-valencen. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leonard E, Ajikumar PK, Thayer K, Xiao WH, Mo JD, Tidor B, Stephanopoulos G, Prather KLJ. Combining metabolic and protein engineering of a terpenoid biosynthetic pathway for overproduction and selectivity control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13654–13659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006138107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dai Z, Liu Y, Huang L, Zhang X. Production of miltradiene by metabolically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:2845–2853. doi: 10.1002/bit.24547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou YJ, Gao W, Rong Q, Jin G, Chu H, Liu W, Yang W, Zhu Z, Li G, Zhu G, Huang L, Zhao ZK. Modular pathway engineering of diterpenoid synthases and the mevalonic acid pathway for miltiradiene production. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:3234–3241. doi: 10.1021/ja2114486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirby J, Romanini DW, Paradise EM, Keasling JD. Engineering triterpene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae –β-amyrin synthase from Artemisia annua. FEBS J. 2008;275:1852–1859. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin VJ, Pitera DJ, Withers ST, Newman JD, Keasling JD. Engineering a mevalonate pathway in Escherichia coli for production of terpenoids. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:796–802. doi: 10.1038/nbt833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ro DK, Paradise EM, Ouellet M, Fisher KJ, Newman KL, Ndungu JM, Ho KA, Eachus RA, Ham TS, Kirby J, Chang MC, Withers ST, Shiba Y, Sarpong R, Keasling JD. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature. 2006;440:940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature04640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paddon CJ, Westfall PJ, Pitera DJ, Benjamin K, Fisher K, McPhee D, Leavell MD, Tai A, Main A, Eng D, Polichuk DR, Teoh KH, Reed DW, Treynor T, Lenihan J, Fleck M, Bajad S, Dang G, Dengrove D, Diola D, Dorin G, Ellens KW, Fickes S, Galazzo J, Gaucher SP, Geistlinger T, Henry R, Hepp M, Horning T, Iqbal T, et al. High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature. 2013;496:528–532. doi: 10.1038/nature12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaur B, Chakraborty D. Biotechnological and Molecular Approaches for Vanillin Production: a Review. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2013;169:1353–1372. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-0066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hansen EH, Moller BL, Kock GR, Bunner CM, Kristensen C, Jensen OR, Okkels FT, Olsen CE, Motawia MS, Hansen J. De novo biosynthesis of vanillin in fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) and baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:2765–2774. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02681-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brochado AR, Matos C, Moller BL, Hansen J, Mortensen UH, Patil KR. Improved vanillin production in baker's yeast through in silico design. Microb Cell Fact. 2010;9:84. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Segre D, Vitkup D, Church GM. Analysis of optimality in natural and perturbed metabolic networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15112–15117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232349399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patil KR, Rocha I, Forster J, Nielsen J. Evolutionary programming as a platform for in silico metabolic engineering. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:308. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brochado AR, Patil KR. Overexpression of O-methyltransferase leads to improved vanillin production in baker's yeast only when complemented with model-guided network engineering. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2013;110:656–659. doi: 10.1002/bit.24731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nijkamp K, van Luijk N, de Bont JA, Wery J. The solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida S12 as host for the production of cinnamic acid from glucose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;69:170–177. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-1973-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shahidi F, Chandrasekara A. Hydroxycinnamates and their in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities. Phytochem Rev. 2010;9:147–170. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Noda S, Miyazaki T, Miyoshi T, Miyake M, Okai N, Tanaka T, Ogino C, Kondo A. Cinnamic acid production using Streptomyces lividans expressing phenylalanine ammonia lyase. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology. 2011;38:643–648. doi: 10.1007/s10295-011-0955-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kang SY, Choi O, Lee JK, Hwang BY, Uhm TB, Hong YS. Artificial biosynthesis of phenylpropanoic acids in a tyrosine overproducing Escherichia coli strain. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:153. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Furuya T, Arai Y, Kino K. Biotechnological production of caffeic acid by bacterial cytochrome P450 CYP199A2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:6087–6094. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01103-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang W, Xie H, He Y, Feng J, Gao W, Gu Y, Wang S, Song C. Chromosome integration of the Vitreoscilla hemoglobin gene (vgb) mediated by temperature-sensitive plasmid enhances γ-PGA production in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2013;343:127–134. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vannelli T, Wei Qi W, Sweigard J, Gatenby AA, Sariaslani FS. Production of p-hydroxycinnamic acid from glucose in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli by expression of heterologous genes from plants and fungi. Metab Eng. 2007;9:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nijkamp K, Westerhof RG, Ballerstedt H, de Bont JA, Wery J. Optimization of the solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida S12 as host for the production of p-coumarate from glucose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;74:617–624. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0703-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kawai Y, Noda S, Ogino C, Takeshima Y, Okai N, Tanaka T, Kondo A. p-Hydroxycinnamic acid production directly from cellulose using endoglucanase- and tyrosine ammonia lyase-expressing Streptomyces lividans. Microb Cell Factories. 2013;12:45. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dewick PM. ALKALOIDS. In: Dewick PM, editor. Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach. 2. ᅟ: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. pp. 291–404. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Minami H, Kim JS, Ikezawa N, Takemura T, Katayama T, Kumagai H, Sato F. Microbial production of plant benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7393–7398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802981105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nakagawa A, Minami H, Kim JS, Koyanagi T, Katayama T, Sato F, Kumagai H. A bacterial platform for fermentative production of plant alkaloids. Nat Commun. 2011;2:326. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hawkins KM, Smolke CD. Production of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:564–573. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fossati E, Ekins A, Narcross L, Zhu Y, Falgueyret JP, Beaudoin GA, Facchini PJ, Martin VJ. Reconstitution of a 10-gene pathway for synthesis of the plant alkaloid dihydrosanguinarine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3283. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lin Y, Sun X, Yuan Q, Yan Y. Combinatorial biosynthesis of plant-specific coumarins in bacteria. Metab Eng. 2013;18:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lin Y, Shen X, Yuan Q, Yan Y. Microbial biosynthesis of the anticoagulant precursor 4-hydroxycoumarin. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2603. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kleinkauf H, von Döhren H. Nonribosomal biosynthesis of peptide antibiotics. Eur J Biochem. 1990;192:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Heyland J, Antweiler N, Lutz J, Heck T, Geueke B, Kohler HP, Blank LM, Schmid A. Simple enzymatic procedure for L-carnosine synthesis: whole-cell biocatalysis and efficient biocatalyst recycling. Microb Biotechnol. 2010;3:74–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2009.00143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shima S, Sakai H. Polylysine produced by Streptomyces. Agric Biol Chem. 1997;41:1807–1809. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xia J, Xu Z, Xu H, Feng X, Bo F. The regulatory effect of citric acid on the co-production of poly (ε-lysine) and poly (L-diaminopropionic acid) in Streptomyces albulus PD-1. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2014;37:2095–2103. doi: 10.1007/s00449-014-1187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li S, Chen X, Dong C, Zhao F, Tang L, Mao Z. Combining genome shuffling and interspecific hybridization among Streptomyces improved ε-poly-L-lysine production. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2013;169:338–350. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9969-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ashiuchi M, Misono H. Biochemistry and molecular genetics of poly-γ-glutamate synthesis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;59:9–14. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-0984-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ashiuchi M. Microbial production and chemical transformation of poly-γ-glutamate. Microb Biotechnol. 2013;6:664–674. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu Z, Feng X, Zhang D, Tang B, Lei P, Liang J, Xu H. Enhanced poly (γ-glutamic acid) fermentation by Bacillus subtilis NX-2 immobilized in an aerobic plant fibrous-bed bioreactor. Bioresour Technol. 2014;155:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.12.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ashiuchi M, Shimanouchi K, Horiuchi T, Kamei T, Misono H. Genetically engineered poly-gamma-glutamate producer from Bacillus subtilis ISW1214. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:1794–1797. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Scoffone V, Dondi D, Biino G, Borghese G, Pasini D, Galizzi A, Calvio C. Knockout of pgdS and ggt genes improves γ-PGA yield in B. subtilis. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2013;110:2006–2012. doi: 10.1002/bit.24846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Feng J, Gu Y, Sun Y, Han L, Yang C, Zhang W, Cao M, Song C, Gao W, Wang S. Metabolic engineering of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens for poly-gamma-glutamic acid (γ-PGA) overproduction. Microb Biotechnol. 2014;7:446–455. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cao M, Geng W, Zhang W, Sun J, Wang S, Feng J, Zheng P, Jiang A, Song C. Engineering of recombinant Escherichia coli cells co-expressing poly-γ-glutamic acid (γ-PGA) synthetase and glutamate racemase for differential yielding of γ-PGA. Microb Biotechnol. 2013;6:675–684. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hara KY, Shimodate N, Ito M, Baba T, Mori H, Mori H. Systematic genome-wide scanning for genes involved in ATP generation in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2009;11:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yoshida H, Hara KY, Kiriyama K, Nakayama H, Okazaki F, Matsuda F, Ogino C, Fukuda H, Kondo A. Enzymatic glutathione production using metabolically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a whole-cell biocatalyst. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;91:1001–1006. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Suzuki T, Yokoyama A, Tsuji T, Ikeshima E, Nakashima K, Ikushima S, Kobayashi C, Yoshida S. Identification and characterization of genes involved in glutathione production in yeast. J Biosci Bioeng. 2011;112:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hara KY, Kiriyama K, Inagaki A, Nakayama H, Kondo A. Improvement of glutathione production by metabolic engineering the sulfate assimilation pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;94:1313–1319. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3841-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tabata K, Ikeda H, Hashimoto S. ywfE in Bacillus subtilis codes for a novel enzyme, L-amino acid ligase. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5195–5202. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5195-5202.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tabata K, Hashimoto S. Fermentative production of L-alanyl-Lglutamine by a metabolically engineered Escherichia coli strain expressing L-amino acid alpha-ligase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:6378–6385. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01249-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hirao Y, Mihara Y, Kira I, Abe I, Yokozeki K. Enzymatic production of L-alanyl-L-glutamine by recombinant E. coli expressing α-amino acid ester acyltransferase from Sphingobacterium siyangensis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77:618–623. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kino K, Nakazawa Y, Yagasaki M. Dipeptide synthesis by L-amino acid ligase from Ralstonia solanacearum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:536–540. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kino K, Noguchi A, Nakazawa Y, Yagasaki M. A novel L-amino acid ligase from Bacillus licheniformis. J Biosci Bioeng. 2008;106:313–315. doi: 10.1263/jbb.106.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kino K, Kotanaka Y, Arai T, Yagasaki M. A novel L-amino acid ligase from Bacillus subtilis NBRC3134, a microorganism producing peptide-antibiotic rhizocticin. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73:901–907. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Meister A, Andersen ME. Glutathione. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983;52:711–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Murata K, Tani K, Kato J, Chibata I. Glycolytic pathway as an ATP generation system and its application to the production of glutathione and NADP. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1981;3:233–242. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hara KY, Shimodate N, Hirokawa Y, Ito M, Baba T, Mori H, Mori H. Glutathione production by efficient ATP-regenerating Escherichia coli mutants. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;297:217–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hara KY, Mori H. An efficient method for quantitative determination of cellular ATP synthetic activity. J Biomol Screen. 2006;11:310–317. doi: 10.1177/1087057105285112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wheeler GL, Trotter EW, Dawes IW, Grant CM. Coupling of the transcriptional regulation of glutathione biosynthesis to the availability of glutathione and methionine via the Met4 and Yap1 transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49920–49928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Moye-Rowley WS, Harshman KD, Parker CS. Yeast YAP1 encodes a novel form of thevjun family of transcriptional activator proteins. Genes Dev. 1989;3:283–392. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Thomas D, Jacquemin I, Surdin-Kerjan Y. MET4, a leucine zipper protein, and centromere-binding factor 1 are both required for transcriptional activation of sulfur metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1719–1727. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kiriyama K, Hara KY, Kondo A. Extracellular glutathione fermentation using engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing a novel glutathione exporter. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;96:1021–1027. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Galperin MY, Koonin EV. A diverse superfamily of enzymes with ATP-dependent carboxylate-amine/thiol ligase activity. Protein Sci. 1997;6:2639–2643. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sheng Y, Sun X, Shen Y, Bognar AL, Baker EN, Smith CA. Structural and functional similarities in the ADP-forming amide bond ligase superfamily: implications for a substrate-induced conformational change in folylpolyglutamate synthetase. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:427–440. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:727–747. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chemler JA, Koffas MA. Metabolic engineering for plant natural product biosynthesis in microbes. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang H, Stephanopoulos G. Engineering E. coli for caffeic acid biosynthesis from renewable sugars. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:3333–3341. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4544-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lin Y, Jain R, Yan Y. Microbial production of antioxidant food ingredients via metabolic engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2014;26:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lim CG, Fowler ZL, Hueller T, Schaffer S, Koffas MA. High-yield resveratrol production in engineered Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:3451–3460. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02186-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Du J, Shao Z, Zhao H. Engineering microbial factories for synthesis of value-added products. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;38:873–890. doi: 10.1007/s10295-011-0970-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yamada R, Yoshie T, Wakai S, Asai-Nakashima N, Okazaki F, Ogino C, Hisada H, Tsutsumi H, Hata Y, Kondo A. Aspergillus oryzae-based cell factory for direct kojic acid production from cellulose. Microb Cell Fact. 2014;13:71. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-13-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wakai S, Yoshie T, Asai-Nakashima N, Yamada R, Ogino C, Tsutsumi H, Hata Y, Kondo A. L-lactic acid production from starch by simultaneous saccharification and fermentation in a genetically engineered Aspergillus oryzae pure culture. Bioresour Technol. 2014;173:376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.09.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Daglia M. Polyphenols as antimicrobial agents. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2012;23:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Moure A, Gullon P, Domínguez H, Parajo JC. Advances in the manufacture, purification and applications of xylo-oligosaccharides as food additives and nutraceuticals. Process Biochem. 2006;41:1913–1923. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Okazaki F, Nakashima N, Ogino C, Tamaru Y, Kondo A. Biochemical characterization of a thermostable β-1,3-xylanase from the hyperthermophilic eubacterium, Thermotoga neapolitana strain DSM 4359. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:6749–6757. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4555-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Katapodis P, Kalogeris E, Kekos D, Macris BJ, Christakopoulus P. Biosynthesis of fructo-oligosaccharides by Sporotrichum thermophile during submerged batch cultivation in high sucrose media. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;63:378–382. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1348-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Yun JW, Choi YJ, Song CH, Song SK. Microbial production of inulo-oligosaccharides by an endoinulinase from Pseudomonas sp. expressed in Escherichia coli. J Biosci Bioeng. 1999;87:291–295. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(99)80034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]