Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the epidemiological characteristics, the etiological factors, the type and severity of injury, visual outcome, and prognostic factors of open globe injuries in children.

Materials and Methods:

This was a retrospective non-comparative case study. A chart review was performed of patients aged 16 years or younger presented at the Eye Unit of the Federal Medical Centre Makurdi, Nigeria, between January 2001 and December 2006. Data were collected on patient demographics, geographic locale of injury, type of ocular injury and vision. Statistical significance was indicated by P < 0.05.

Results:

The study sample comprised 78 children. A statistically significantly greater number of males (n = 51) sustained injury compared to females (n = 27; P < 0.05). The mean age of the study sample was 9.7 ± 2.40 years (range, 1 year 2 months to 15 years 8 months). The age-group that sustained injury most commonly was 6 years to 10 years. Left eyes were more likely to be affected, accounting for 53 (68.0%) cases. There were 54% (n = 42) of patients injured at home and 51.0% (n = 40) were injured while playing. The most common injury was corneoscleral laceration, (67.9% [n = 24] eyes). Only 30.0% (n = 23) patients presented within the first 24 hours of the injury, 38.5% (n = 30) of patients were visually impaired and 25.6% (n = 20) patients were blind on presentation. Visual acuity at last follow up indicated that 39.7% (n = 31) patients were visually impaired and 39.7% (n = 31) were blind.

Conclusion:

More public health efforts should be geared towards preventing potential causes of ocular injury at home and at playgrounds.

Keywords: Corneoscleral Laceration, Home, Play, Sharp Object

INTRODUCTION

Ocular trauma is an important cause of ocular morbidity in children. Ocular trauma is the leading cause of non-congenital unilateral blindness in childhood and has a significant impact on the patient's quality of life. Additionally, there are associated risks of amblyopia and unacceptable cosmesis which may have psychological impact. The highest incidence of ocular trauma is in children (50% of all cases).1,2,3,4,5,6,7

The World Health Organization (WHO) program for prevention of blindness estimated that 750,000 cases of eye injuries are hospitalized yearly worldwide and 200,000 cases are open globe injuries.8 Generally, children are more prone to severe ocular injuries due to their immature motor skills and their tendency to imitate adult behavior without anticipating the attendant risks.9

In Nigeria, very few studies have been done on ocular injuries in children,10,11,12 and no study has evaluated open globe injury. In the current study, we evaluate the epidemiological pattern, etiological, and prognostic factors of open globe injury in children in Benue state, Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective chart review was performed for all children of 16 years or younger with open-globe injuries who were admitted to Eye Unit of Federal Medical Centre Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria between January 2001 and December 2006. Data were collected on demographic characteristics, place of injury, object that caused the injury, activities leading to injury, type/severity of injury, initial and final visual acuities, clinical diagnosis, time interval of injury and first presentation, unilateral or bilateral injury, surgical procedure, duration of follow-up, and the main cause of visual loss and impairment. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Federal Medical Centre, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria.

Open-globe injury was defined as a full thickness wound of the eyeball according to the Birmingham Eye Trauma Terminology System (Kuhn et al.).13 The type and severity of the injuries was classified according to the Eagling's classification of open globe injury: Penetrating, perforating, and rupture.2

Children were only included if there was clear evidence of a recent full thickness ocular injury at presentation. All those who had a full thickness ocular injury either repaired or followed at other centres were excluded from the study. Visual acuity (VA) at presentation and at 16 weeks postoperatively was documented and categorized using WHO criteria.14

The data were presented as mean ± SD, frequencies, and percentages. The difference between two groups was calculated using the Chi-square test. Statistical significance was indicated by P < 0.05. Data analysis was performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

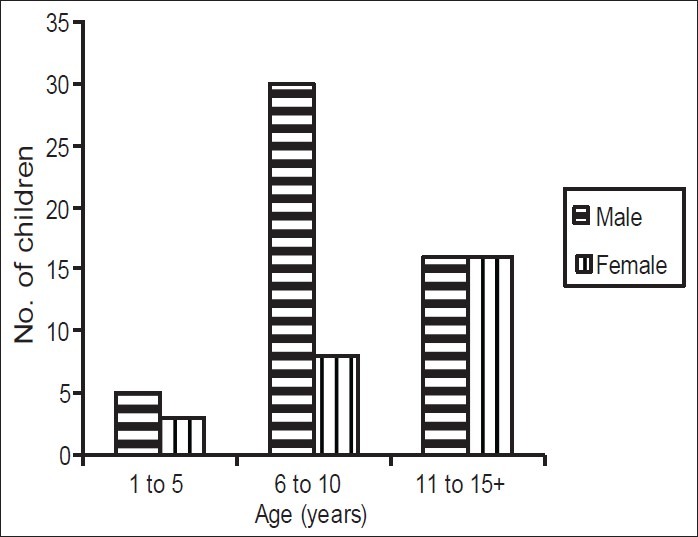

Of the 516 patients with ocular trauma, 136 (26.3%) were children. A total of 92 (67.6%) children had open-globe injuries and 78 met the inclusion criteria. The mean age was 9.7 ± 2.40 years (range, 1 year 2 months to 15 years 8 months). The demographic data are presented in Figure 1. The number of males (n = 51) was significantly higher than females (n = 27; male to female ratio of 1.9:1). (X2 > x2, P < 0.05). There was a preponderance of males in children 10 years and younger (preschool and school age) [Figure 1]. The relative ratio of males was highest (3.8:1) in the age-group 5 years to 10 years. However, in the secondary school age (11 years to 16 years), the male to female ratio was 1:1.

Figure 1.

The distribution of age and gender of 78 Nigerian children with open-globe injury

Preschool children (0 years to 5 years) were the least affected accounting for only 10.3% (n = 8) while the age-group that had the greatest number of open globe injuries was 6 years to10 years, which comprised 49.0% (n = 38) children [Figure 1].

Fifty-one (65.0%) children lived in a rural areas, and the remaining 27 (35.0%) children lived in urban areas.

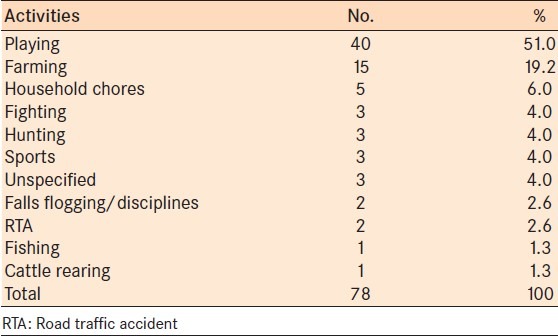

Table 1 presents the activity that led to the injury. Forty (51.0%) children were injured while playing, 15 (19.2%) children were injured while farming, 5 (6%) children were injured while performing household chores, and 3 (4%) children were injured while fighting.

Table 1.

Activities leading to open-globe injuries in Nigerian school children

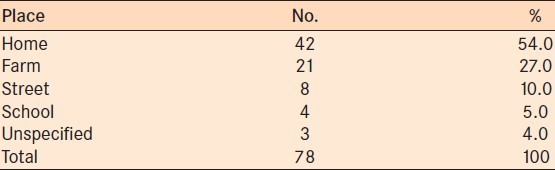

Table 2 presents the environment in which the injury took place. Forty-two (54.0%) children were injured at home, 21 (27.0%) children were injured on the farm, and 4 (5.0%) children were injured at school [Table 2].

Table 2.

Location of open-globe injuries in Nigerian school children

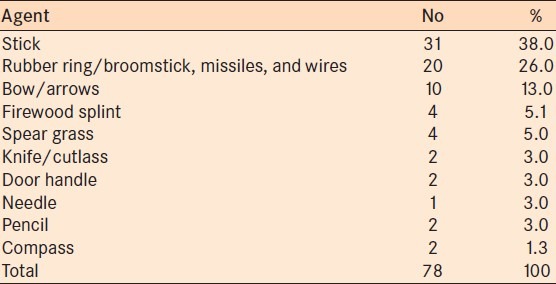

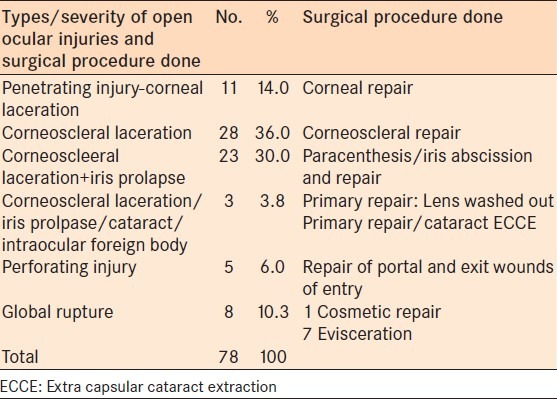

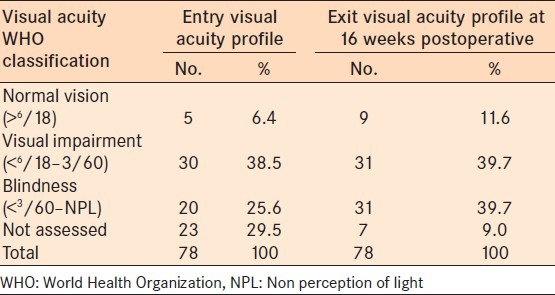

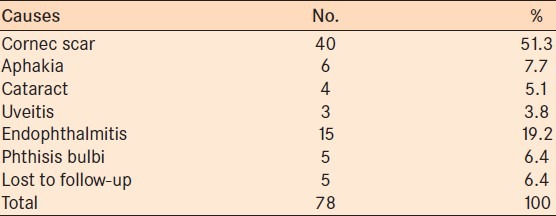

All injuries were from sharp objects [Table 3]. The most common injury was corneoscleral laceration, accounting for 83.3% (n = 65) of cases [Table 4]. Only 30.0% (n = 23) of children presented within the first 24 hours of the injury. On presentation, 6.4% (n = 5) of children had normal vision, 38.5% (n = 30) of children were visually impaired, and 26.0% (n = 20) of children present with blindness. The initial visual acuity could not be assessed in 23 children. Exit visual acuity showed that 9 children had normal vision, 31 children were visually impaired, and 31 children were blind. Seven children were lost to follow-up after discharge from the hospital [Table 5]. The most common cause of visual impairment and blindness was corneal scars, which accounted for 51.3% (n = 40) of cases [Table 6].

Table 3.

Objects that caused open-globe injury in Nigerian school children

Table 4.

Type and severity of open-globe injuries and surgical treatment in Nigerian school children

Table 5.

Visual acuity at presentation and at 16 weeks postoperatively in Nigerian school children

Table 6.

Causes of blindness from open-globe injuries in Nigerian school children

DISCUSSION

There was a preponderance of male children with open-globe injury (male:female ratio 1.9:1). However, the gender ratio did vary with the different age-groups. The highest male to female ratio was 3.8:1 which was found in the school age-group. In the older children, the occurrence of open-globe injuries were equal in both sexes. This trend may be due to the fact that there is better parental supervision in preschoolers. In Nigerian society, boys are generally allowed more liberty than girls and tend to spend more time outside with their peers, with less parental supervision.9 The boys are allowed and even encouraged to exhibit more aggressive behavior as part of their normal development. The disproportionate male preponderance tends to be even higher in developed countries ranging from 4:1-5:1 (males:females).4,5,15,16,17 This difference may be attributed to the socio-economic status, age distribution. and activities leading to the injuries. In developing countries, older boys and girls tend to play together in outdoor games. Historically, when boys were being trained on football and other more active games, girls were trained on games requiring lower activity such as handball. However, currently there are female national football teams in Nigeria which is promoting equality of participation in sports in males and females. Hence, it is not surprising that in this present study and equal number of males and females in the older age-groups sustained open-globe injuries.

The present study showed that a higher frequency of globe related trauma occurred at home. This observation concurs with a study by Juan et al.3 The second and third most frequent locales for open-globe trauma were farms and streets, respectively. The need for better parental supervision cannot be overemphasized. The child's environment also needs to be devoid of dangerous objects. Unique to the developing countries such as Nigeria is the rural setting, where toys are a luxury. Hence, children use objects in the environment to make their own toys. Prominent among these objects are sticks, rubber ring/broomstick missiles. These have resulted to open-ocular injuries. Broomstick injuries have often resulted in the complication of broomstick induced endophthalmitis, which invariably leads to evisceration of the affected eyes. The majority (65.0%) of the children in the present study were from rural settlements. This study has shown that a higher frequency of ocular trauma in children occurred at home which differs from a study by Shoja et al., who reported a higher frequency of ocular injuries occurring on road and streets.9,18 In Africa, most children are left under the care of aged grandparents who often require care themselves. The children are therefore often left on their own and are exposed to many dangerous objects such as sticks, bows and arrows, rubber ring/broomstick missiles, and wires. Hence, it is not surprising that 51.0% of the injuries occurred while playing.

Open globe injuries occurring at home, on the farm and streets accounted for 75% of all injuries in this study. Injuries that occurred at school accounted for only 5.1% (n = 4); two from corporal punishment, one from a compass, and one from a pencil. The three unspecified cases were suspicious cases of shaken baby syndrome. Even though this is not rampant in our experience, it should be suspected when the history obtained is not straight forward or contradicts the child's version when the caregivers are absent. Road traffic accident accounted for only two cases. The children were knocked down on the streets due to motorbike accidents. This low incidence could be attributed to low traffic in the rural areas.

Only 29.5% (n = 23) of cases presented within the first 24 hours of injuries. Our study showed that the younger the child and the more severe and obvious the injury to the unprotected eye, the earlier the presentation. This might be associated with the socio-economic, geographic, and cultural factors which may keep patients from receiving timely and appropriate medical assistance as reported by Grieshaber and Stegmann from South Africa.19 This delay can be attributed to use of home remedies, lack of recognition of the severity of the injury by parents, and inexperience of the staff at primary health care centers. On presentation, 25.6% (n = 20) of children were blind at presentation and only 6.4% (n = 5) of children had normal vision.

The results of the present study concur with previous studies of ocular trauma in children. Penetrating injuries due to sharp objects were more common than injuries due to rupture.7,12,18 This contrasts with ocular trauma in adults where rupture is more common.20

Delayed presentation/diagnosis, polymicrobial infections, associated lenticular damage, presence of intraocular foreign body, posterior segment involvement, and visual loss at presentation adversely affect visual prognosis. Good initial visual acuity at presentation and early primary repair are all important favorable prognostic factors affecting final visual outcome in cases with ocular trauma.15,19 The shorter the duration from the onset of injury to surgery the better the final visual acuity and vice versa.

Children under age 9 years old have worse visual outcome due to development of amblyopia.9 Open-globe injuries are the most severe cases with more than half causing blindness at initial examination at observed in this study. Hence, generally, open-globe injuries carry a poorer prognosis and are more likely to require surgery and subsequently to suffer from long-term visual impairment.3,17

In conclusion, as the majority of ocular injuries can be prevented by relatively simple measures, identified etiological factors such as playing with sticks and other pointed objects should be discouraged. Pictorial educational materials could be used to teach during health-education classes. The occurrence of open globe injury in school is quite low (5.1% of children). One initiative may be that employers should be encourage to close businesses to coincide with school pick-up time. This will enhance greater parental supervision after school.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sternberg P, Jr, de Juan E, Jr, Michels RG. Penetrating ocular injuries in young patients. Initial injuries and visual results. Retina. 1984;4:5–8. doi: 10.1097/00006982-198400410-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eagling EM. Perforating injuries of the eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976;60:732–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.60.11.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Juan E, Jr, Sternberg P, Jr, Michels RG. Penetrating ocular injuries. Types of injuries and visual results. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:1318–22. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34387-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niiranen M, Raivio I. Eye injuries in children. Br J Ophthalmol. 1981;65:436–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.65.6.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel BC. Penetrating eye injuries. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64:317–20. doi: 10.1136/adc.64.3.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiegel D, Nasemann JH, Nawrocki J, Gabel VP. Severe ocular trauma managed with primary pars plana vitrectomy and silicone oil. Retina. 1997;17:275–85. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jandeck C, Kellner U, Bornfeld N, Foerster MH. Open globe injuries in Children. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2000;238:420–6. doi: 10.1007/s004170050373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Bdour MD, Azab MA. Childhood eye injuries in North Jordan. Int Ophthalmol. 1998;22:269–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1006335522435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shoja MR, Miratashi AM. Paediatric Ocular Trauma. Acta Med Iran. 2006;44:2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onyekwe LO. Spectrum of eye injuries in children in guinness eye hospital Onitsha. Nig J Surg Res. 2001:126–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Umeh RE, Umeh OC. Causes and visual outocme of childhood injuries in Nigeria. Eye (Lond) 1997;11:489–95. doi: 10.1038/eye.1997.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kyari F, Mahmoud B, Alhassan, Abiose A. Pattern and outcome of paediatric ocular trauma, A 3-year review of national eye centre Kaduna. Nig J Ophthalmol. 2000;8:11–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhn F, Morris R, Witherspoon CD, Heimann K, Jeffers JB, Treister G. A standardized classification of ocular trauma. Ophthalmol. 1996;103:240–3. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30710-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guide for the Evaluation of Visual Impairment. Published through the Pacific Vision Foundation, San Francisco for presentation at the International Low Vision Conference. Vision-99. Vision-99. © Copyright 1999 by August Colenbrander, M.D.; p. 7. All rights reserved. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pieramici DJ, Sternberg P, Jr, Aaberg TM, Sr, Bridges WZ, Jr, Capone A, Jr, Cardillo JA, et al. A system for classifying mechanical injuries of the eye (globe). The Ocular Trauma Classification Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123:820–31. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soylu M, Demircan N, Yalaz M, Isiguzel I. Etiology of paediatric perforating eye injuries in Southern Turkey. Ophthalmic Epdemiol. 1998;5:7–12. doi: 10.1076/opep.5.1.7.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takyam JA, Midelfart A. Survey of eye injuries in Nornagian children. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1993;71:500–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1993.tb04626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoja MR, Shanavazi A. Evaluation of ocular trauma in 353 patients admitted to Ophthalmic Department Yazd. Jshahid Sadoughi Univ Med Sci Spring. 1998;4:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grieshaber MC, Stegmann R. Penetrating eye injuries in South African children: Etiology and visual outcome. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:789–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strahman E, Elman M, Daub E, Baker S. Causes of paediatric eye injuries: A population based study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:603–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070060151066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]