Abstract

Purpose:

The aim was to assess the impact of cataract surgeries in reducing visual disabilities and factors influencing it at three institutes of India.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective chart review was performed in 2013. Data of 4 years were collected on gender, age, residence, presenting a vision in each eye, eye that underwent surgery, type of surgery and the amount the patient paid out of pocket for surgery. Visual impairment was categorized as; absolute blindness (no perception of light); blind (<3/60); severe visual impairment (SVI) (<6/60-3/60); moderate visual impairment (6/18-6/60) and; normal vision (≥6/12). Statistically analysis was performed to evaluate the association between visual disabilities and demographics or other possible barriers. The trend of visual impairment over time was also evaluated. We compared the data of 2011 to data available about cataract cases from institutions between 2002 and 2009.

Results:

There were 108,238 cataract cases (50.6% were female) that underwent cataract surgery at the three institutions. In 2011, 71,615 (66.2%) cases underwent surgery. There were 45,336 (41.9%) with presenting vision < 3/60 and 75,393 (69.7%) had SVI in the fellow eye. Blindness at presentation for cataract surgery was associated to, male patients, Institution 3 (Dristi Netralaya, Dahod) surgeries after 2009, cataract surgeries without Intra ocular lens implant implantation, and patients paying <25 US $ for surgery. Predictors of SVI at time of cataract surgery were, male, Institution 3 (OM), phaco surgeries, those opting to pay 250 US $ for cataract surgeries.

Conclusion:

Patients with cataract seek eye care in late stages of visual disability. The goal of improving vision related quality of life for cataract patients during the early stages of visual impairment that is common in industrialized countries seems to be non-attainable in the rural India.

Keywords: Blind, Cataract, Severe Visual Impairment, Visual Acuity

INTRODUCTION

Cataract is an ocular morbidity of aging. It is the leading cause of blindness.1 Little progress has been noted in the field of preventing senile cataract, however, surgery allows recovery of vision lost due to cataract. Cataract surgery is the second most cost-effective health intervention after vaccination.2 The global initiative for eliminating avoidable blindness called “VISION 2020 - The right to the sight” therefore prioritized cataract and recommended the member countries of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the non-governmental organizations focus on performing more cataract surgeries.3 For monitoring progress, the cataract surgery rate (CSR) per million per year was accepted as an indicator. Evidence-based data suggested that if the CSR rate was 3500 per million per year, the backlog of operable cataracts and incidence blindness due to cataract can be addressed. However, the CSR varies widely among countries It ranged from as low as 824 in Guatemala to as high as 5100/million in Argentina 2011.4

Technologies to manage cataract have advanced dramatically in last three decades, and this has resulted in increased cataract surgeries as well as greater acceptance in the community.5,6 Currently, ophthalmologists perform cataract surgery to improve the vision related quality of life rather than to address blindness. This propensity towards quality of life means very few cataract patients present for surgery when they are blind (vision < 3/60 in a better eye) and incapacitated in terms of mobility, reading, writing, and communication. Limburg et al. had found that 40% to 50% of cataract surgeries in India are performed on patients with >6/60 vision in fellow eye and the surgery was not a sight-restoring exercise7 For appropriate public health policies in developing countries where a large backlog of operable cataract exists, there is a need to review the visual status of patients presenting with cataract and assess the role of cataract surgery in reducing visual disabilities.8 In addition, finding the underlying factors associated with the late presentation of patients with severe visual impairment (SVI) due to cataract is necessary. Late presentation is more common in rural areas. Two of our study centers are located and serve rural and tribal areas of India, and the third center has majority of cataract patients recruited from outreach camps held in rural Maharashtra. The perceived benefit to these patients and for the provider will be better compared with patients with moderate visual impairment (MVI) due to cataract.

In this study, we evaluate the role of cataract surgery in reducing visual disabilities and assess common barriers to patients presenting for cataract surgery. Based on the findings, we recommend a public health approach for reducing cataract related blindness.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The ethical and research committees of all three institutions granted consent for this study. This study was conducted from November 2012 to January 2013. The data of 2004 and 2005, as well as data of 2010 and 2011, was referred for this review.

One ophthalmologist and one administrator of each institute liaised with an ophthalmic epidemiologist to undertake this study. Institute 1 (SNC) is located in central India, and the majority of patients were from the tribal population. The cataract cases were screened at camps, clinic of vision centers and the base hospital. All surgeries are performed at the hospital. Institute 2 (H.V.D.) is located in an urban area of Maharashtra state, India. Cataract patients for this institute present from rural Maharashtra through screening camps and from city hospital clinics. Institute 3 (Dristi Netralaya, Dahod) is located in the Gujarat State of India and provides cataract services through outreach initiatives in the Gujarat, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh States.

All three institutes maintain medical information of cataract patients in computerized databases. Demographic information is collected at the time of the initial assessment by health care staff speaking local language. To confirm age, the date of birth in relation to important historical events e.g. independence of India (1947), China war (1962), last war with Pakistan (1969) etc. were queried.

An ophthalmic assistant performed measurement of visual acuity. Visual acuity in each eye was noted “as presented” with a Snellen illiterate “E” chart. The chart was placed at six meters from the patient. If the top “E” could not be correctly identified, the test was repeated at three meters. If the vision could not be tested even at three meters, the perception of light with and without projection for each eye from four directions was evaluated. The ophthalmologist examined each patient for diagnosing cataract, other ocular comorbidities and plan for cataract surgery. One eye underwent surgery at a time. A few patients underwent surgery of both eyes within 1-day of each other. Patients and relatives were informed of the different types of lens implants. The basic lens was offered without any cost to the patient if he/she was referred from an outreach camp. Other patients selected phacoemulsification surgery and more expensive intraocular lenses that were implanted by a senior ophthalmologist at a nominal price to cover the cost. The cost in rupees was converted in dollars as per the exchange rate sin January 2005 and January 2010 respectively.

Data of all three institutions were collated together, however, the year of surgery and the institution code was added later.

The Statistical Package for the Social Studies (SPSS 16; IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA) was used for data analysis. We assumed that the eye scheduled for cataract surgery would have worse vision than the fellow eye. Based on presenting vision in the fellow eye, we grouped all persons into; WHO blind (<3/60), SVI (<6/60), MVI (≤6/18-6/60) and normal sighted persons (>6/18). For determining the magnitude of visual disabilities in patients with cataract, we calculated the frequencies, percentage proportion and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Univariate analysis by the parametric method was used to test the association of visual disability to different risk factors such as age, sex, state of residence, eye operated, type of surgery and payment for cataract surgery. The odds ratio, 95% CI, Chi-square value were calculated. A P < 0.05 was statistically significant. Based on the year of surgery, we grouped participants into those underwent surgery between 2005 and 2009 and those who underwent surgery in 2010 and 2011. Subsequently, we compared the trend in visual disability when the patient presented for cataract surgery.

The results of this study were shared with the administrators at all three institution and presented at ophthalmic conferences.

RESULTS

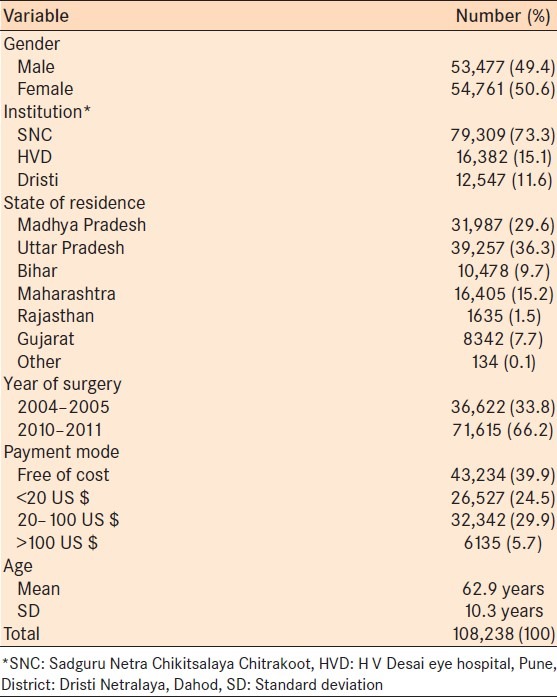

We reviewed a representative sample of 108,238 patients who underwent cataract surgery at three eye institutions in India. Patient demographics and other characteristics are presented in Table 1. Two third of cases underwent surgery in the year 2011 at Institute 1.

Table 1.

Demographics, geographic locale and other characteristics of patients who underwent cataract eye surgery at three ophthalmic institutes in India

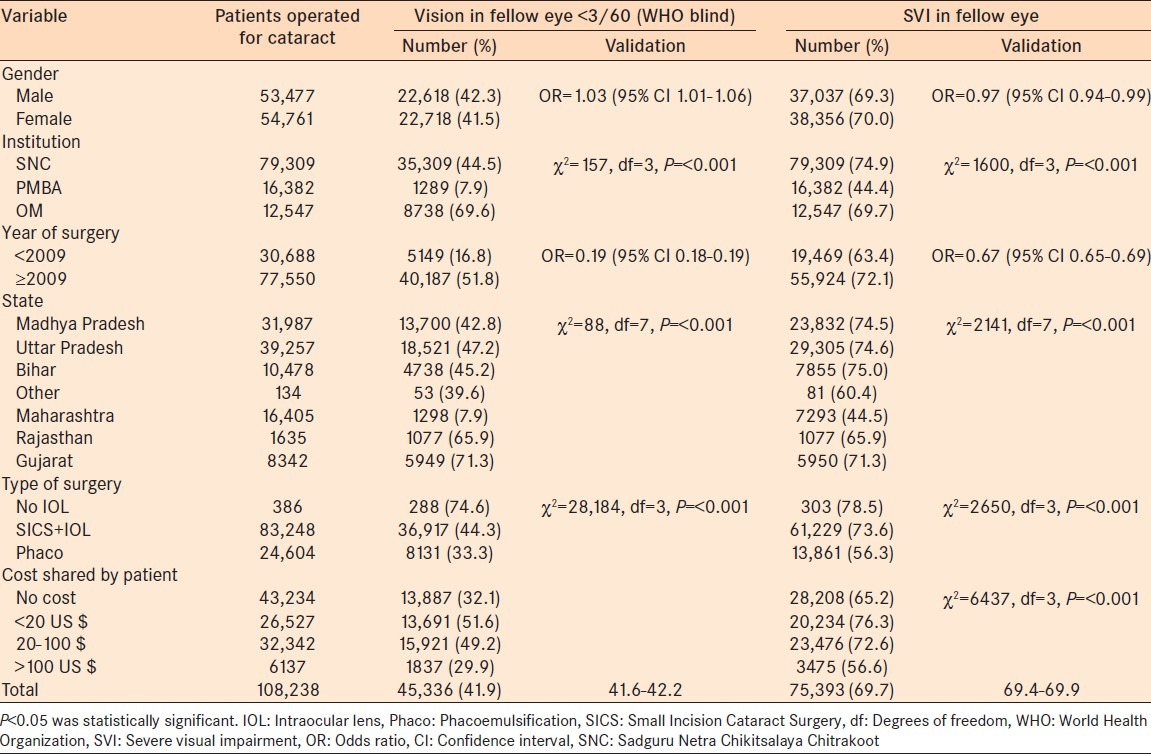

The prevalence of bilateral blindness “as presented” was 41.9% (95% CI: 41.6-42.2). The prevalence of severe visual disabilities (VA < 6/60 in the better eye as presented) was 69.7% (95% CI: 69.4-69.9). The magnitude and association of visual disabilities (blind and SVI) to different variables is presented in Table 2. Patients from Institute 2 (an urban center) had a lower incidence of blindness in the fellow eye. Patients who paid for a higher cost implant had a lower incidence of blindness at the time of cataract surgery. Approximately half of the cataract patients who underwent surgery after 2009 were blind at presentation. Only 17% of patients who underwent surgery before 2009 were blind at presentation. In contrast, the proportion of cataract cases with SVI was statistically significantly higher in patients who underwent surgery after 2009 (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Visual disability and determinants in study participants schedule for cataract surgery

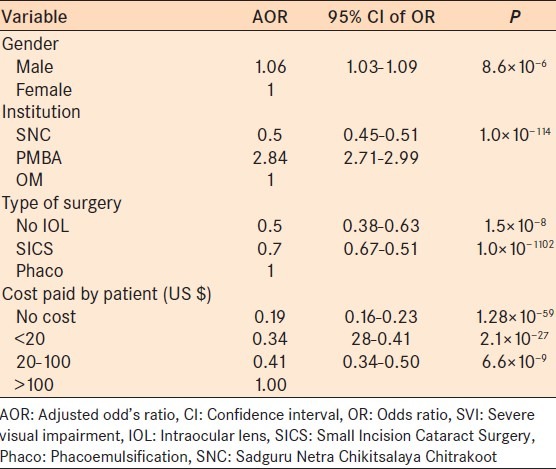

We carried out regression analysis to identify the predictors of SVI at the time of presentation for cataract surgery. The variables that were significantly associated to SVI were included in the model [Table 3]. Female gender, institutions of urban area, those selecting the option of phacoemulsification with an expensive lens implant and paying a substantial cost out of pocket for cataract surgery were independent predictors of lower visual disabilities at the time of cataract surgery.

Table 3.

Predictors of SVI in the better eye at presentation for cataract surgery

DISCUSSION

We studied a large number of cases to assess visual impairment of patients presenting with cataracts. Only 42% of cataract cases were blind, and 70% had SVI at the time of cataract surgery. Hence, by successfully operating on the cataract in the eye, one can reduce the visual disabilities of these patients. The conventional thinking that patients with cataract seek eye care in the early stages of their visual disability does not seem to be applicable to the patients we evaluated in this study. Patients who were willing to share the cost of surgery and prepared to undergo phacoemulsification and lens implantation, presented for cataract surgery in the early stages of visual disability. These patients underwent cataract surgery for improving their vision related quality of life rather than reducing their visual disability.

The gender distribution of cataract patients in our series was not statistically significantly different (P > 0.05). This is in contrast to the findings of previous studies where female gender was a barrier to access cataract surgery.9,10,11 Perhaps the outreach camp approach was able to bridge the gender gap in our study.12 Male (but not female) gender was statistically significantly associated to blindness (P < 0.05). However, the female had statistically significantly higher risk of SVI than males (P < 0.05). In the older population, retired males may have lower visual needs than females. For example, older females remain responsible for looking after household chores in the rural and tribal Indian communities.

Distance is a noted barrier for eye care and cataract surgery in developing countries.9,13,14 In Institute 2 (PMBA) which is in an urban location, with many of their patients presenting from nearby urban areas, distance was not a barrier. This has resulted in less visual disabilities in institutions located in urban areas compared to patients from the two other institutions which were in tribal areas, and access due to distances could be a major barrier. Hence, distance could result in late presentation and a high proportion of cases with blindness at the time of cataract surgery. Sending outreach screening teams and transporting cataract cases to the base hospital at low cost could improve the uptake and result in patients presenting in a timely manner for cataract assessment and surgery.

Direct and indirect costs of cataract surgery are known causes of the low uptake and late presentation for surgery in developing countries.15,16 Information on lens implantation seems to be a proxy indicator for the cost of the cataract surgery in our study. Most of the surgeries were performed with lens implantations except in a few cases with other morbidities or with advanced stages of cataract. However, advanced types of lenses were inserted in urban population through payment. Patients undergoing phacoemulsification and directly paying a higher cost for special lenses had less visual disabilities than other patients at presentation. The earlier intervention for an urban population could be due to the visual needs for better visual function in the urban setting. In addition, is it likely that surgeons could have motivated urban patients to undergo phacoemulsification in the early stages of cataract progression as phacoemulsification is difficult in mature or hyper-mature cataracts compared to operating upon immature cataract.17

The quantitative indicator of cataract surgery to monitor the progress of various countries efforts to eliminate blindness due to cataract is judiciously applied by the prevention of blindness program managers.18 However, Gujarat state had a very high CSR (5000-6000/M/Y) and had a substantial number of individuals with blindness due to cataract.19 The impact of cataract surgery in reducing blindness will vary with visual status of the eye undergoing surgery and the status of the fellow eye.20 Researchers have proposed both CSR and cataract surgery coverage (CSC) as indicators to monitor progress of cataract blindness reduction.21 However, CSC is difficult to generate more frequently as it requires community-based assessment of lens status among the elderly population in the community. Our study also found that cataract surgery had the potential of reducing visual disabilities by nearly a half as the rest did not have blinding visual impairment in fellow eyes. Thus, CSR alone seems to be of limited value in assessing the impact of the VISION 2020 initiative. Further categorization of CSR in relation to barriers (in male and females, in urban and rural areas and for those sharing cost versus no cost to the patient) will allow program managers direct their efforts more effectively towards reducing visual disabilities.

There are some limitations in our study. In this retrospective review, information of fellow eyes after cataract surgery of the first eye, was not available. Hence, we cannot judge if visual impairment in the fellow eye was due to unoperated cataract, co-morbidities or poor outcomes of previous surgery in the fellow eye. All three institutes in our study are ISO 9001 certified.22,23,24 Hence, poor surgical outcomes are less likely to cause visual disabilities in the fellow eyes as periodic audits helps improve surgical outcomes.25 The data in our study does not cover all patients underwent cataract surgery in the three institutions before 2009. Thus, changes in the outcome in relation to the time and institutions should be interpreted with caution. The cost of cataract was converted in US $ at two different years. Comparison of cost should be done with caution as fluctuation of exchange rate could have influenced the costing exercise. This being retrospective data; some important factors influencing the association of cataract and visual status were not included in the present study.

In our study, if we assume that surgery reduced visually disability and restored vision in all patients, the providers would be able to reduce blindness in only 42% of blindness due to cataract and 70% of cataract responsible for SVI. Due to increase in the aged demographic of the population, the incidence of cataract is increasing in many developing countries. Thus, the backlog of operable cataract is also increasing. Alternately, more and more non-sight threatening lens opacities are being treated while blinding cataract still exists in the underprivileged areas.26,27 Considerable progress has been made in reducing cataract blindness in India in the first half of VISION 2020.28 However, a significant effort has to be made if more cataract surgeries, especially for the underserviced population are to be performed in the coming years. The goal of improving vision related to quality of life among patients with cataract in their early stages of visual impairment that is common in industrialized countries seems to be currently unattainable for the rural population of India.29

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff of all three institutions to assist us in the collection of cataract related data. Mr. Rich Bern assisted in English editing the manuscript. Dr. Deepak Edward provided important tips to improve the manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackland P. The accomplishments of the global initiative VISION 2020: The Right to Sight and the focus for the next 8 years of the campaign. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60:380–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.100531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellwein LB, Lepkowski JM, Thulasiraj RD, Brilliant GE. The cost effectiveness of strategies to reduce barriers to cataract surgery. The Operations Research Group. Int Ophthalmol. 1991;15:175–83. doi: 10.1007/BF00153924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Cataract: Disease Control and Prevention of Visual Impairment in VISION 2020 Global Initiative for the Elimination of Avoidable Blindness Action Plan 2006-2011. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. pp. 10–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furtado JM, Lansingh VC, Nano ME, Carter M. VISION 2020 Latin America. Cataract Surgery Rates in Latin America 2005-2011. [Last accessed on 2013 Jul 09]. Available from: http://www.iapb.org/sites/iapb.org/files/Joao%20Furtado_CSR%20in%20Latin%20America%202005.2011.pptx .

- 5.Health Quality Ontario. Intraocular lenses for the treatment of age-related cataracts: An evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2009;9:1–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaidyanathan K, Limburg H, Foster A, Pandey RM. Changing trends in barriers to cataract surgery in India. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:104–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Limburg H, Foster A, Vaidyanathan K, Murthy GV. Monitoring visual outcome of cataract surgery in India. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:455–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jadoon Z, Shah SP, Bourne R, et al. Cataract prevalence, cataract surgical coverage and barriers to uptake of cataract surgical services in Pakistan: the Pakistan National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1269–73. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.106914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syed A, Polack S, Eusebio C, Mathenge W, Wadud Z, Mamunur AK, et al. Predictors of attendance and barriers to cataract surgery in Kenya, Bangladesh and the Philippines. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:1660–7. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.748843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao GN, Khanna R, Payal A. The global burden of cataract. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22:4–9. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283414fc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang M, Wu X, Li L, Huang Y, Wang G, Lam J, et al. Understanding barriers to cataract surgery among older persons in rural China through focus groups. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2011;18:179–86. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2011.580884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finger RP, Kupitz DG, Holz FG, Chandrasekhar S, Balasubramaniam B, Ramani RV, et al. Regular provision of outreach increases acceptance of cataract surgery in South India. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:1268–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Razafinimpanana N, Nkumbe H, Courtright P, Lewallen S. Uptake of cataract surgery in Sava Region, Madagascar: Role of cataract case finders in acceptance of cataract surgery. Int Ophthalmol. 2012;32:107–11. doi: 10.1007/s10792-012-9523-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gyasi M, Amoaku W, Asamany D. Barriers to cataract surgical uptake in the upper East region of ghana. Ghana Med J. 2007;41:167–70. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v41i4.55285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JG, Goode Sen V, Faal H. Barriers to the uptake of cataract surgery. Trop Doct. 1998;28:218–20. doi: 10.1177/004947559802800410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melese M, Alemayehu W, Friedlander E, Courtright P. Indirect costs associated with accessing eye care services as a barrier to service use in Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:426–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakrabarti A, Singh S. Phacoemulsification in eyes with white cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26:1041–7. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00525-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jose R, Bachani D. World Bank-assisted cataract blindness control project. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1995;43:35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khandekar R, Mohammed AJ. Cataract prevalence, cataract surgical coverage and its contribution to the reduction of visual disability in Oman. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2004;11:181–9. doi: 10.1080/09286580490514487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murthy GV, Vashist P, John N, Pokharel G, Ellwein LB. Prevelence and causes of visual impairment and blindness in older adults in an area of India with a high cataract surgical rate. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17:185–95. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2010.483751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao GN, Khanna R, Payal A. The global burden of cataract. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22:4–9. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283414fc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ISO 9001 Certification to HV Desai Eye Hospital. [Last cited on 2013 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.hvdeh.org/index.php?option=com_content and view=article and id=19 and Itemid=113 .

- 23.Drishti Netralalya, Dahod, India. [Last cited on 2013 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.drashtinetralaya.org/about-us.html .

- 24.Quality Process in Sadguru Netra Chikitsalaya, Chitrakoot, India. [Last cited on 2013 Feb 21]. p. 12. Available from: http://www.accessh.org/CaseStudies_Pdf/SadguruNetraChikitsalaya.pdf .

- 25.Gogate P, Vakil V, Khandekar R, Deshpande M, Limburg H. Monitoring and modernization to improve visual outcomes of cataract surgery in a community eyecare center in western India. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:328–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lecuona K, Cook C. South Africa's cataract surgery rates: Why are we not meeting our targets? S Afr Med J. 2011;101:510–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dandona L, Dandona R, Anand R, Srinivas M, Rajashekar V. Outcome and number of cataract surgeries in India: Policy issues for blindness control. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2003;31:23–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2003.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khanna RC, Marmamula S, Krishnaiah S, Giridhar P, Chakrabarti S, Rao GN. Changing trends in the prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in a rural district of India: Systematic observations over a decade. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60:492–7. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.100560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norregaard JC, Bernth-Petersen P, Alonso J, Dunn E, Black C, Andersen TF, et al. Variation in indications for cataract surgery in the United States, Denmark, Canada, and Spain: Results from the International Cataract Surgery Outcomes Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:1107–11. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.10.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]