Abstract

Purpose:

To assess the outcomes of congenital/developmental cataract from a tertiary eye care hospital in Northwest Nigeria.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective chart review was performed of all patients diagnosed with congenital or developmental cataract who underwent surgery from January 2008 to December 2009. Data were collected on patient demographics, preoperative characteristics, intraoperative complications, and postoperative outcomes as well as complications.

Results:

A total of 181 eyes of 102 patients underwent surgery. There were 95 (52.5%) right eyes. There were 64 (62.7%) males. The mean age of the patients was 6.88 ± 7.97 years. Fifty-four (51.3%) patients were below 3 years old. Most (62%) patients had congenital cataract with a history of onset within the first year of life [39 (62.9%) patients]. Amblyopia, nystagmus, and strabismus were the most frequent ocular comorbidities accounting for 50.3%, 36.5%, and 35.4% of eyes respectively. The majority (84.3%) of the patients had surgery within 6 months of presentation. All patients underwent manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS). Seventy-nine (77.5%) patients underwent simultaneous bilateral surgery. Intraocular lens implantation was performed in 83.4% eyes. The most common early and late postoperative complication was, posterior capsular opacity which occurred in 65 eyes of 43 children. In these cases, moderate visual acuity was predominant visual outcome.

Conclusion:

Treatment of pediatric cataract in our setting is complicated by demographic factors which results in late presentation and consequently, late treatment of children. Short-term visual outcome is fair. Data on long term postoperative outcomes could not be acquired due to poor follow-up.

Keywords: Cataract, Congenital Cataracts, Nigeria, Pediatric

INTRODUCTION

The goal of vision 2020 ‘the Right to sight’, is the worldwide reduction of childhood blindness from the current level of 0.75/1000 to 0.4/1000 children.1,2 Blindness in children remains the second leading cause of blind person years worldwide.2 The prevalence of childhood blindness in Africa is approximately 10 times higher than in industrialized nations.3 Of the 1.4 million children suffering from blindness worldwide,4 congenital cataract remains a major cause especially in middle and low income countries.2,5

The purpose of this 2-year retrospective study is to review the visual outcomes, postoperative complications and other challenges of pediatric cataract surgery at a tertiary eye hospital in Northwestern Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective chart review was performed for all patients who underwent surgery for congenital or developmental cataract. The research ethics committee of National Eye Centre, Kaduna approved this study. We defined congenital cataract as cataract that developed within the first year of life or the signs of poor fixation signifying early onset. Developmental cataract was defined as a cataract that develops after the first year of life.1,2 Data were collected on patient demographics, preoperative characteristics, intraoperative complications, and postoperative outcomes. All patients underwent manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS). Patients below 5 years of age underwent primary capsulotomy with or without anterior vitrectomy (Vitron 2020-BF Geuder, Germany). MSICS was performed in the following manner; first a 3-7 mm scleral tunnel [depending on the need for an intraocular lens (IOL)] was lifted; cortical matter was washed out/or nuclear material was extracted (older children) and at least one alternate stitch using 10.0 non-absorbable nylon suture was applied for all patients below 18-years-old. The sutures were only removed in some cases, mainly in older children due to irritation. The IOL power was calculated using the SRKII or HofferQ formulas and 20% and 10% of the calculated power was deducted in patients 2-4-years-old and 5-7-years-old, respectively. Polymethylmethacylate (PMMA) IOLs were implanted in children 2 years and older and in some patients below 2 years. Most patients underwent surgery under general anesthesia (GA). Surgeries were performed by the same pediatric ophthalmologist. Postoperatively, all patients were placed on topical steroid and chloramphenicol for at least 2 months, and 5 days course of 5-10 mg of oral prednisone. Uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) was assessed with age appropriate acuity testing techniques, such as ability to fix and follow lights/objects hundred and thousand sweet test, Kay picture, and the Snellen chart. Children who did not receive an IOL were provided aphakic glasses and occlusion therapy for amblyopia was initiated where indicated. In cases of monocluar surgery, aphakic glasses was also provided with an eye patch on the seeing eye for variable duration (depending on the age of the patient) during waking hours. Posterior capsular opacity was managed by YAG laser capsulotomy for patients older than 4 years and manual posterior capsulectomy for patients below 4-years-old. Results were analyzed with SPSS version 16 (IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

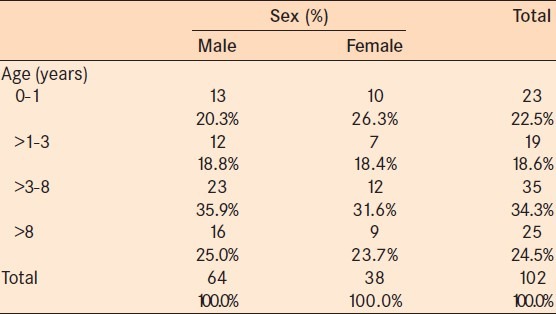

A total of 181 eyes of 102 patients underwent surgery, 95 surgeries were performed on the right eye. There were 64 (62.7%) males in the study sample. Table 1 shows the detail of the age and sex distribution of patients. The mean age of all the patients was 6.88 ± 7.97 years (range, 0-13 years). The differences in the gender proportions of the was independent age-group (P > 0.05). Seventy-two percent of the patients were from northwestern Nigeria, where the hospital is located.

Table 1.

Age and Sex distribution

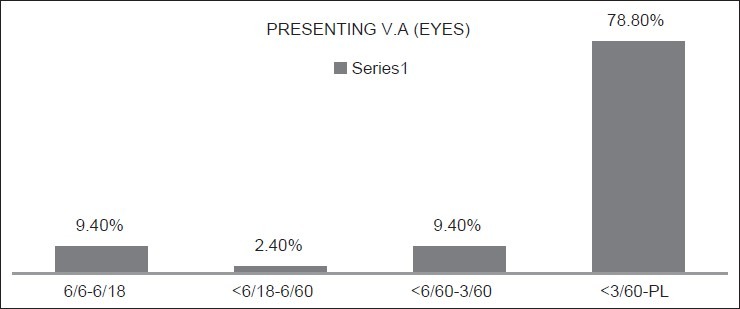

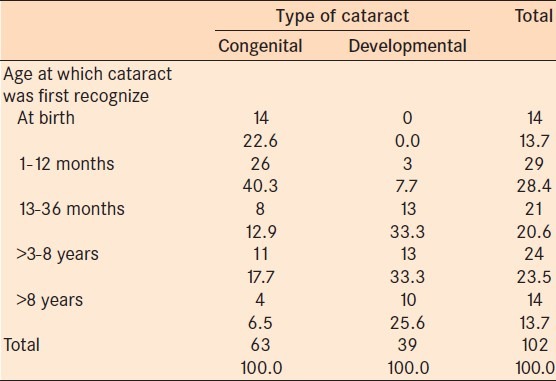

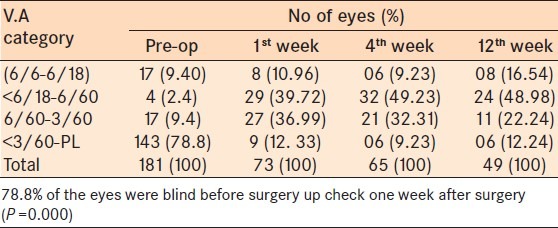

Seventy-eight percent of the eyes were blind at presentation [UCVA of light perception (LP) to <3/60, Figure 1]. Preoperatively, UCVA ranged from 6/18 to LP. Statistically significantly younger patients presented with congenital cataracts compared to developmental cataracts (P = 0.00). Twenty-two percent of the congenital cataracts were diagnosed at birth. Thirty-seven percent of the congenital cataracts were identified after the first birthday, and 66% of the developmental cataracts were noticed between the first and the eighth birthdays [Table 2]. The resulting delay in diagnosis affects the postoperative visual outcome.

Figure 1.

Pre-operataive VA of operated patients

Table 2.

Age at which cataract was noticed by pateints/care givers

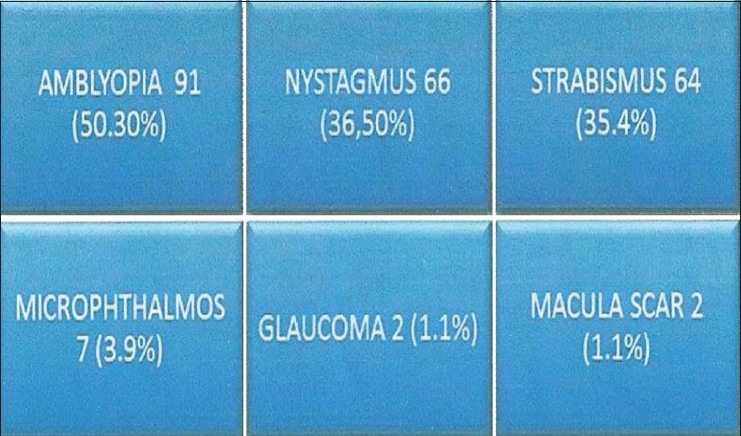

Amblyopia, nystagmus and strabismus were the most frequent ocular comorbidities accounting for 50.3%, 36.5%, and 35.4% of patients, respectively [Figure 2]. These were signs of severe vision deprivation early in life. There were 7 children with systemic associations. The associated systemic abnormalities included, hearing loss (1 child); mental retardation (1 child) and delayed developmental milestones (5 children).

Figure 2.

Showing ocular co-morbidities in eyes

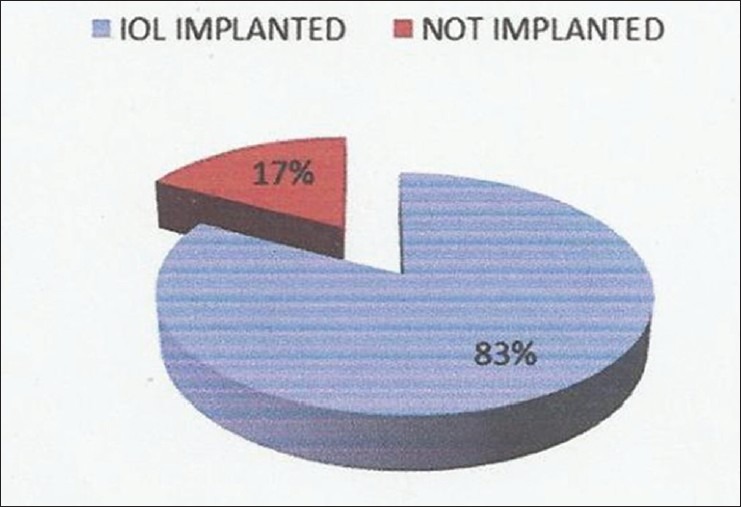

Simultaneous bilateral intraocular surgery (SBIS; bilateral surgery in one session) was performed in 77.5% of patients. These where cases with bilateral congenital cataracts. IOL was implanted in 83.4% eyes [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

IOL implantation in operated eyes

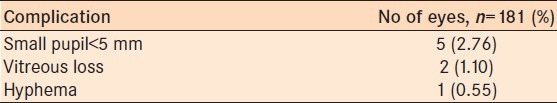

Intraoperative complications recorded include: Miosis in five eyes, posterior capsule rupture with vitreous loss in two eyes and hyphema in one eye [Table 3].

Table 3.

Intra operative complications

Approximately 87.3% of the eyes presented for postoperative evaluation at one week, 71.2% at 4 weeks postoperatively and 27.1% at 12 weeks postoperatively. Patients were more likely to present at 1 week postoperatively (P = 0.000). The follow-up rate was low which limited the ablity to refract patients and to treat patients with amblyopia or low vision.

One hundred and forty three eyes (78.8%) were blind preoperatively. At 1 week postoperatively 9/73 (12.3%) eyes remained blind and 6/65 (9.2%) remained blind at 4 weeks. About 76.7%, 81.5%. and 71.2% of the eyes had moderate vision i.e. between <6/18 and 6/60, one week, 4 weeks and 12 weeks postoperatively, respectively The proportion of eyes with this vision preoperatively was 11.8%. [Table 4].

Table 4.

Post- operative (available) visual acuity

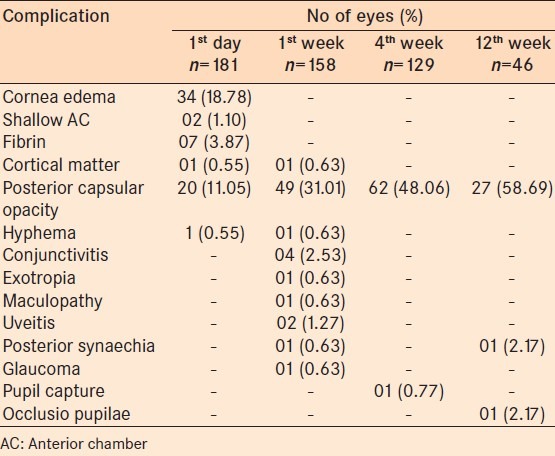

Corneal edema was the most common complication on the first postoperative day (34 eyes). Other complications included posterior capsule opacification (20 eyes), fibrinoid reaction in the anterior chamber (7 eyes) and shallow anterior chamber (2 eyes) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Post- op complications

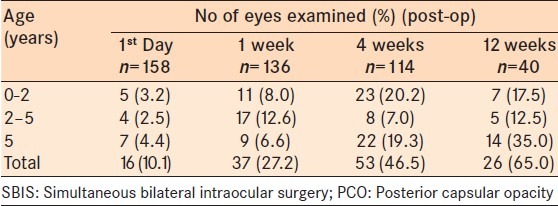

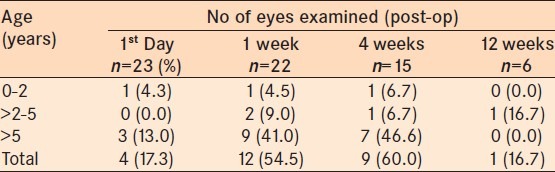

Complications at 1 week postoperatively included, posterior capsular opacification (49 eyes), conjunctivitis (4 eyes), and uveitis (2 eyes). Four and 12 weeks postoperatively, posterior capsular opacification accounted for the majority complications [Table 5]. Opacification at the visual axis was more common in younger patients and in patients who underwent SBIS [Tables 6 and 7]. Opacification at the visual axis occured in 65 eyes of 43 patients at various follow-up visits.

Table 6.

Age distribution of patients with PCO after SBIS

Table 7.

Age distribution of patients with PCO after unilateral cataract surgery

DISCUSSION

Pediatric cataract is the most common cause of childhood blindness worldwide.2,6 A review by Tablin et al., reported that up to 75% of childhood blindness is due to cataracts in developing countries.7 In children with cataract, sight can only be restored by surgery. A good childhood cataract surgery service demands a multidisciplinary approach. We performed a retrospective review of cataract surgery in children in our hospital over a 2 year period. We found that the uptake of surgery was higher in male children. This may due to the fact that male children are valued more than the female children across African communities.6

The average age of our patients at the time of surgery was 7 years. At this age, amblyopia is a significant complication depending on the laterality and morphology of the cataract. Late presentation is an important factor in the management of pediatric cataract in developing countries. Yortson et al's study from east Africa, reported a mean age at surgery of 3.5 years.3 In Nepal the average age at the time of surgery was approximately 6-years-old which is similar to our study.8 In Tanzania health treatment seeking behavior, poverty, gender, local health beliefs, and the ability of the health care team to provide the needed care determined when children are brought to hospital.6,9

Due to late presentation, the majority of the eyes (79%) were blind at presentation (>3/60 to LP). In east Africa and India, a similar proportion of the eyes were blind at presentation.3,10 Children with developmental cataract are brought to a hospital relatively late in time frame for the development of the visual system.10 This explains the high number of eyes with amblyopia, nystagmus and strabismus.

Only seven of our patients had associated systemic abnormalities such as deafness, mental retardation, and delayed developmental milestones. These factors could negatively impact on the postoperative visual outcome. The children with other severe systemic associations might have died or not been brought to the hospital for cultural reasons.

Bilateral simultaneous surgery was performed on 77% of the patients in this study. The main reason for bilateral surgery was to reduce cost, reduce the risk of anesthesia and to increase the uptake of surgery for the second eye. Previous studies have reported that bilateral simultaneous cataract surgery in children is safe.11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18

Long-term assessment of visual outcome is limited by very poor follow-up. Only a quarter of the patients were seen at 3 months postoperatively. However, follow out 1 week postoperatively was good. In Tanzania, 67% and 43% of children who underwent cataract surgery were seen at two and ten weeks postoperatively respectively.19 Comprehensive long term postoperative care of these children is precluded with this early and high rate of attrition. This care includes refraction, spectacle prescription, treatment of amblyopia and monitoring for long term complications such as glaucoma and corneal decompensation. Sex (being a male), close proximity to hospital and short delay in presentation were significantly associated with presenting for the two weeks follow up in a study from Tanzania.20 The 10 weeks postoperative visit was related to the distance from hospital and good preoperative vision in the operated eye.20 High quality counseling to parents and good tracking of patients/parents improved the follow-up after surgery at the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre in Tanzania.19

Visual outcome was generally fair, with about three quarters of the eyes regaining useful vision in the operated eye. Yortson et al., reported a visual acuity of better than 6/60 in about 91% of their patients.3,21 In Kuwait, a mean best corrected visual acuity of 6/60 and 6/12 was achieved after surgery for unilateral and bilateral cataracts in children respectively.22 Postoperative refraction needs to be enforced in our centre in order to achieve the best vision for these children. This will ensure optimal treatment of amblyopia.

Cornea edema and fibrinoid reaction were the most common immediate postoperative complications in our study. These were managed with topical and short-term systemic steroids. The most important postoperative challenge was posterior capsule opacification. The loss of the clarity of visual axis needs to be urgently treated in order achieve the aim of cataract surgery in children. Numerous surgical techniques have been described to either prevent or manage visual axis opacification, none of which are ideal.23 Techinues for treating visual axis opacification includes removing the posterior capsule (intraoperative or postoperative), removing the anterior vitreous body and membranectomy. These surgical maneuvers can increase the risk of posterior segment complication. We manage posterior capsule opacification by YAG capsulotomy or rarely manually if very thick. Very few patients underwent these procedures and low follow up was low likely due to financial constraint. Hence, the UCVA was not analyzed.

One of the major limitations was lack of data on best corrected visual acuity. The refraction is easier to perform once the wound is stable as about 10-12 weeks postoperatively. Refraction outcome is useful in determining need for amblyopia treatment and referral to the low vision service. Decentralization of follow up as suggested by cataract experts at the Kilimanjaro Centre for Community Ophthalmology (KCCO)7 may significantly enhance postoperative checkups. Follow up can be improved by telephone follow up and home visits as appropriate.

CONCLUSION

Treatment of pediatric cataract in our environment is complicated by socio-demographic factors. This results into late presentation of children for care. Short-term visual outcome is fair. Long-term monitoring of treatment is not possible due to poor follow up. The current standard of care is inclusive care that is good preoperative counseling, varying surgical techniques, good postoperative visual rehabilitation including treatment of amblyopia, low vision services and inclusive education for the children.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Helen Keller International who supported the training of the Pediatric Surgeon and SightSavers for provision of surgical consumables.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yorston D. The global initiative vision 2020: The right to sight childhood blindness. Community Eye Health. 1999;12:44–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert C, Foster A. Childhood blindness in the context of VISION 2020-The right to Sight. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:227–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yorston D, Wood M, Foster A. Results of cataract surgery in young children in east Africa. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:267–71. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown RJ. How should blindness in children be managed? Eye (Lond) 2005;19:1037–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabin G, Chen M, Espandar L. Cataract surgery for the developing world. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008;19:55–9. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3282f154bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster A, Gilbert C. Epidemiology of childhood blindness. Eye (Lond) 1992;6:173–6. doi: 10.1038/eye.1992.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronsard A, Geneau R, Shirima S, Courtright P, Mwende J. Why are children brought late for cataract surgery. Qualitative findings from Tanzania? Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:383–8. doi: 10.1080/09286580802488624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thakur J, Reddy H, Wilson ME, Jr, Paudyal G, Gurung R, Thapa S, et al. Pediatric cataract surgery in Nepal. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:1629–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2003.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mwende J, Bronsard A, Mosha M, Bowman R, Geneau R, Courtright P. Delay in presentation to hospital for surgery for congenital and developmental cataract in Tanzania. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1478–82. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.074146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gogate P, Khandekar R, Shrishrimal M, Dole K, Taras S, Kulkarni S, et al. Delayed presentation of cataracts in children: Are they worth operating upon? Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17:25–33. doi: 10.3109/09286580903450338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Totan Y, Bayramlar H, Çekiç O, Aydin E, Erten A, Daðlioðlu MC. Bilateral cataract surgery in adult and pediatric patients in a single session. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26:1008–11. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00380-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Totan Y, Bayramlar H, Yilmaz H. Bilateral paediatric cataract surgery in the same session. Eye (Lond) 2008;23:1199–205. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith GT, Liu CS. Is it time for a new attitude to “simultaneous” bilateral cataract surgery? Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1489–96. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.12.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramsay AL, Diaper CJ, Saba SN, Beirouty ZA, Fawzi HH. Simultaneous bilateral cataract extraction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25:753–62. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(99)00035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma TK, Worstmann T. Simultaneous bilateral cataract extraction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:741–4. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00741-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arshinoff SA, Strube YN, Yagev R. Simultaneous bilateral cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29:1281–91. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(03)00052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarikkola AU, Kontkanen M, Kivelä T, Laatikainen L. Simultaneous bilateral cataract surgery: A retrospective survey. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:1335–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nallasamy S, Davidson SL, Kuhn I, Mills MD, Forbes BJ, Stricker PA, et al. Simultaneous bilateral intraocular surgery in children. J AAPOS. 2010;14:15–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kishiki E, Shirima S, Lewallen S, Courtright P. Improving postoperative follow-up of children receiving surgery for congenital or developmental cataracts in Africa. J AAPOS. 2009;13:280–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eriksen JR, Bronsard A, Mosha M, Carmichael D, Hall A, Courtright P, et al. Predictors of poor follow-up in children that had cataract surgery. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2006;13:237–43. doi: 10.1080/09286580600672213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson ME, Jr, Bartholomew LR, Trivedi RH. Pediatric cataract surgery and intraocular lens implantation: Practice styles and preferences of the 2001 ASCRS and AAPOS memberships. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29:1811–20. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(03)00220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdelmoaty SM, Behbehani AH. The outcome of congenital cataract surgery in Kuwait. Saudi J Ophthalmol [Internet] 2011;25:295–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2011.01.002. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1319453411000038 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson ME, Pandey SK, Thakur J. Paediatric cataract blindness in the developing world: Surgical techniques and intraocular lenses in the new millennium. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:14–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]