Abstract

Purpose:

To compare the effectiveness of pencil push-up therapy (PPT) versus office-based vision therapy in patients with convergence insufficiency.

Materials and Methods:

In this study, 60 students from Zahedan University of Medical Sciences with convergence insufficiency were selected. After determining their refractive error (with a retinoscope), near point of convergence (by millimeter ruler), near heterophoria (by alternate prism cover test), and positive fusional vergence at near (by prism bar), subjects were divided into two groups to receive PPT (at least three times a day for 5 minutes each time) or office-based therapy (two times each week for 60 minutes each visit) without home reinforcement. Subjects were re-examined 4 and 8 weeks after initiation of treatment. Statistical analysis was performed with the independent samples t-test and the analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was indicated by P < 0.05.

Results:

The near point of convergence, phoria, and positive fusional vergence were not statistically different between the two groups before treatment (P > 0.05). After 4 and 8 weeks of therapy, only the positive fusional vergence was statistically significantly different between groups (P = 0.001). Results from ANOVA indicated a considerable difference between the two groups in general but the observed difference was related only to positive fusional vergence.

Conclusion:

PPT and office-based vision therapy are comparable for treatment of convergence insufficiency. While we do not deny the more efficacious nature of office-based therapy, it is not always practical, may be too expensive, and may not be locally available. A home-based therapy offers a cost-effective reasonable alternative.

Keywords: Convergence Insufficiency, Office-Based Therapy, Pencil Push-up Therapy, Vision Therapy

INTRODUCTION

Convergence insufficiency (CI) is a prevalent binocular visual disorder that is characterized by high exophoria at near, orthophoria or low exophoria at far, remote near point of convergence (NPC), low positive fusional vergence (PFV) and low AC/A ratio.1

CI is more prevalent than other types of non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies. The prevalence of CI has been reported about 3-5% of population. Studies have reported a higher prevalence of 5.3% in subjects 6-18 years old, 6% in children 8-12 years old, 4.2% in children of 9-12 years old, and 7.7% in university students.2,3,4 The prevalence may be higher still in the presbyopic adult population due to decompensated accommodative convergence, but it may be better treated with base-in prism at near.

In CI, patient's complaints are frequently associated with reading or near work. The common symptoms are eyestrain and headache after short periods of reading, blurred vision, diplopia, sleepiness, difficulty in concentrating, loss of comprehension over time, a pulling sensation in eyes, and movement of letters while studying or reading.5 Yet some patients with CI do not report any problems.4 This absence of complaints may be due to suppression, avoidance of near visual tasks, high discomfort threshold, or occlusion of one eye during reading.4

Many studies in both the optometric and ophthalmic literature have shown that orthoptics (also known as vision therapy or training) is the treatment of choice for CI.6,7,8 It is agreed that the objective of vision therapy is to develop better fusional control of binocular deviation via improvement of PFV.6 There are two main vision therapy approaches, office-based therapy (with or without home reinforcement), and home-based therapy. These exercises are effective for the removal of asthenopia and improvement of convergence function, even in adult patients. Office-based therapy combined with home-based therapy has been shown to be more effective than home-based therapy alone.9 Home-based therapy is a simple and cost-effective option prescribed by both optometrists and ophthalmologists, and has been considered the initial training technique with satisfactory results. Home-based therapy is successful if the patient performs the therapy correctly.5,10 However, home-based training has never been shown to be any more effective than placebo therapy in randomized clinical trials. Patwardhan et al. reported that most ophthalmic practitioners prescribed pencil push-up therapy (PPT) as the initial treatment for CI and their patients had satisfactory results.11

Some authors have suggested that PPT may not work well because patients become bored with the procedure or suppress an eye. A disadvantage of PPT technique is that patients tire of the exercises quickly3 and that there is no suppression control. Many studies have evaluated these concerns. Scheiman et al. evaluated the efficacy of office-based therapy versus PPT for CI in young adults and reported that office-based vision therapy was the most effective treatment for the improvement of NPC and PFV although there was a statistically significant decrease in symptoms in all treatment groups.12

Due to the high prevalence of CI, especially among the subjects with high near task demands, and its effect on academic behaviors,13 the purpose of this study was to compare the efficacy of office-based therapy with home-based therapy as measured by changes in both objective findings (NPC, near heterophoria and positive fusional vergence) and patient symptoms in students with CI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this semi-experimental study, participants were 60 students from Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (mean age of 21.3 ± 0.9 years). The nature, purpose, and methods of this study were clearly explained to the participants in advance, and their voluntary cooperation and informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the participants were assured that their information was kept confidential. The Research Ethics Committee at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences approved the study (Code: 752).

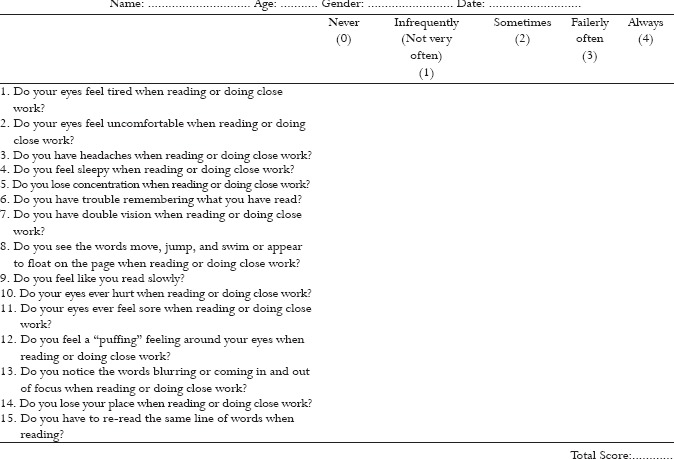

The inclusion criteria were, a survey score 21 or greater using the convergence insufficiency symptom survey (CISS) questionnaire14[see Appendix A], near exo-deviation which was at least 4 prism diopters more than distance, remote NPC (6 cm or more), insufficient near PFV (not meeting Sheard's criterion,4 or break point less than 15 prism diopters), the best corrected monocular VA of 20/25 or better at far and near.

The exclusion criteria were constant strabismus, amblyopia, history of refractive surgery, vertical phoria of 1 prism diopter or more, presence of manifest or latent nystagmus, presence of eye disease, and/or a history of strabismus surgery. Refractive errors were determined by dry retinoscopy (ί-200 retinoscope; Heine Optotechnik, Munich, Germany). Cycloplegic retinoscopy was performed with cyclopentolate 1% if required. If there were significant changes in the refractive error (≥1.50 D hyperopia, ≥0.50D myopia, ≥0.75D astigmatism, ≥0.75D anisometropia in spherical equivalent, or ≥1.50 D anisometropia in any meridian (based on cycloplegic refraction)),12 subjects were asked to wear their appropriate refractive correction (spectacle or contact lenses) for at least 2 weeks prior to entering the study.

The evaluation of near heterophoria, NPC and PFV is described below. Assessment was done three times instead of as a single measure, and the mean values were calculated. Block randomization was used to divide subjects into two groups: Home-based PPT and office-based therapy groups. Odd-numbered subjects were assigned to the home-based therapy group and, even-numbered subjects to the office-based therapy group.

The subjects were followed up 4 and 8 weeks later, and in the follow-up visits, near heterophoria, NPC and PFV were investigated. The near heterophoria was determined using the alternate prism cover test method with the best correction. Subjects fixated on an accommodative target, a small isolated letter “E” of approximately (6/9) size from the reduced Snellen chart, on a metal reading rod at eye level at 40 cm. As the alternate cover test was performed, the prism power was adjusted until there was no recovery movement in either eye. For confirmation of the neutral point, the prism power was increased until a reversal movement was seen. The prism power was reduced until no movement was seen. For determination of NPC, the previous target was moved gradually from 40 cm in the subject's midline toward the bridge of the nose of the subject at a rate of approximately 3-5 cm/sec.3 The subjects were instructed to keep the target single during the test and report when it appeared double (break point). The distance between break point to the plane of the lateral canthus was measured with a millimeter ruler. For subjects who did not report diplopia, the examiner measured the distance at which eye lost fixation on the target. For each subject, the NPC was measured only after giving adequate instructions.15 A prism bar was used for measurement of fusional reserves at near. Target used was the same as before. The subject was asked to look at the target and the prism with base-in was introduced over the habitual correction and prism power slowly increased step-by-step until the subject reported sustained break and recovery. The above procedure was repeated with base-out prism and the break and recovery points were determined and recorded in prism diopters. We observed the subject's eyes during measurement for detection of possible suppression.2,16 All testing was performed under full room illumination with best correction in place.

For home-based PPT, the subjects held a pencil at 50 cm along the midline. They were instructed to position themselves so that when they looked at the tip of the pencil, they were aware of diplopia at far. A target such a clock on the wall behind the pencil was used to control suppression with use of physiological diplopia. Next, the pencil was moved toward their eyes slowly, and the participants were instructed to try to maintain fixation so that the target appeared as a single pencil. When they perceived double vision of the target even with maximum effort, the pencil was moved back slowly until they regained fusion. If suppression occurred and one of the physiologic diplopic images disappeared, the subjects was instructed to blink or shake the pencil as an anti-suppression technique. The subjects performed this exercise at least three times a day for 5 minutes each time.

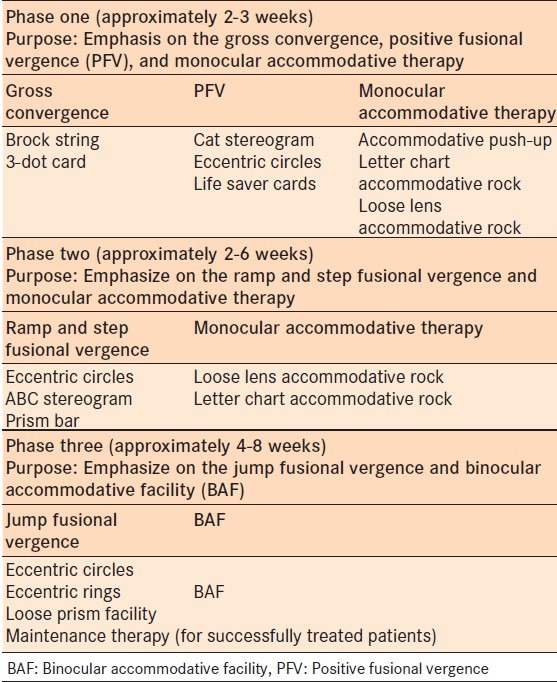

The office-based therapy group was given exercises for improvement of vergence amplitude by prism, vergence facility, accommodative amplitude, and facility [Table 1]. These exercises were performed two days per week for 60 minutes. The subjects had one minute break for each 5 minutes therapy.

Table 1.

Vision therapy techniques used for the office-based therapy group

There was no loss of subjects to follow-up during this study and all subjects completed their 4 and 8 week follow-up exams. After data collection, the normality of data were assessed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (P > 0.05). The data were normally distributed. Hence, data were analyzed using the independent-samples t-test (to compare the mean score of the CISS, age, NPC, near heterophoria and PFV between the home-based therapy group and office-based therapy group). The repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the mean of NPC, PFV, and phoria before 4 and 8 weeks after intervention in each group, separately and the Bonferroni test was used for the pairwise comparisons. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 17, IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. In all tests, the statistical significance was indicated by P < 0.05.

RESULTS

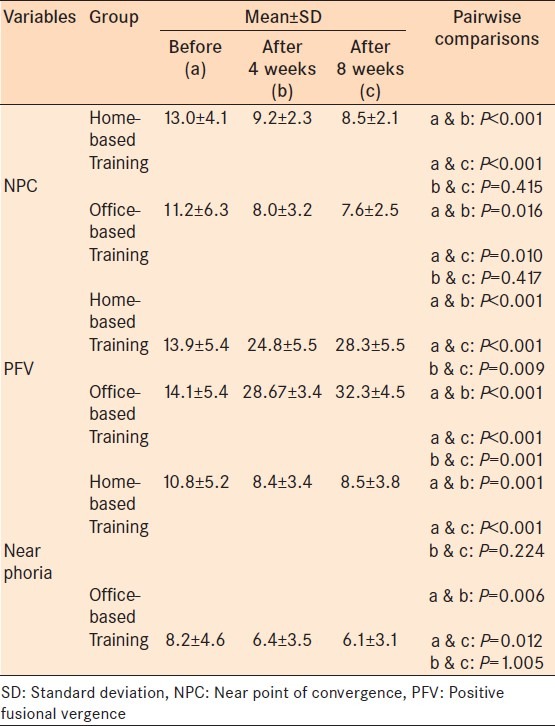

A total of 60 students participated in this study, of which 36 (60.0%) were females. The mean age in all subjects was 21.3 ± 0.9 years. The mean age was 21.4 ± 0.9 years for the PPT group and 21.2 ± 0.9 years for the office-based therapy group (P = 0.523). There were 18 females and 12 males in each therapy group. The mean score of CISS for the Home-Based Therapy group and office-based therapy group was 35.8 ± 10.2 and 36.2 ± 4.2, respectively (P = 0.308). The means and standard deviations for NPC, PFV, and the near exodeviation before, 4 and 8 weeks after intervention are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean near point of convergence, positive fusional vergence, and near heterophoria before, 4 and 8 weeks after intervention

Prior to starting therapy, the NPC (P = 0.610), near heterophoria (P = 0.821), and PFV (P = 0.580) were not statistically different between groups. After 4 and 8 weeks, only PFV was statistically significantly different between groups (P = 0.001). After 4 and 8 weeks, NPC was not statistically different between groups (P = 0.805). There was no statistical difference between groups in near heterophoria after 4 and 8 weeks (P = 0.701).

A repeated measures ANOVA was used for comparison of the mean of measured variables (NPC, PFV and phoria) before 4 and 8 weeks after intervention in each group. This test showed differences in the mean NPC, PFV, and phoria between before 4 and 8 weeks after intervention in each group, separately. The Bonferroni test was used for the pairwise comparisons.

Table 2 presents the data for NPC in both home-based therapy and in office-based therapy groups, there was significant difference in the mean of NPC between before and 4 weeks after intervention, and before with 8 weeks after (P < 0.05, all comparisons), but not between 4 and 8 weeks (P > 0.05). After therapy, the NPC became closer to the eyes, there was no statistical difference based on length of therapy. There was a significant difference in the mean PFV among the three time periods tested (before with 4 weeks after intervention, before with 8 weeks after, and 4 with 8 weeks after) in both groups (P < 0.05, all comparisons).

The difference near phoria before and 4 weeks after intervention, and before and 8 weeks after intervention was statistically significant (P < 0.05). But not between 4 and 8 weeks after intervention (P > 0.05).

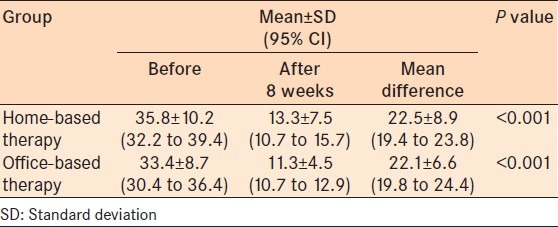

The mean and standard deviation of the CISS score in the two therapy groups before and at the end of therapy (after 8 weeks) is presented in Table 3. The mean score of CISS for the two groups was not significantly different before intervention using the independent-samples t-test (P = 0.308), but this difference was statistically significant at the end of the therapy sessions (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Mean convergence insufficiency symptom survey questionnaire score in two therapy groups before and at the end of therapy sessions

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicated that there was a statistically significant decrease in symptoms in both groups, but there was no significant difference between the efficacy of PPT versus office-based therapy for the treatment of CI. However, changes in NPC and near heterophoria in the office-based therapy group were somewhat greater than the home-based therapy group. By comparison, home-based therapy showed significantly lower improvement in positive fusional vergence.

In the convergence insufficiency treatment trial (CITT) study on 19-33 years old subjects with CI, Scheiman et al.12 reported that the office-based therapy effects on symptoms reduction and improvement of CI parameters was the same as the present study. However, Scheiman et al.12 cited that the results of PPT are low compared to the office-based therapy, which is in contrast to our results.

Another study by Scheiman et al16 on children 9-18 years old reported lower efficacy of PPT at home compared with office therapy, which is in contradiction with the results of present study. The mean changes in PFV and NPC before and at the end of the treatment phase in Scheiman et al.16 study concurs with our study. The amount of near phoria was not investigated as a parameter is Scheiman et al16 study before and after treatment, whereas we investigated this parameter and observed that there was no significant difference in the two groups. Of note, with true CI, the observed difference in amount of phoria before and after the treatment can attributed to the vergence after-effect, as the amount of deviation will not change with therapy if prolonged occlusion is used. This may not be the case in pseudo-CI, which is really accommodative insufficiency with a false apparent high exophoria.

Brautaset et al.17 showed the efficacy of PFV therapy for the reduction of asthenopia in patients with CI, which concurs with the result of present study. Arnoldi et al.7 investigated the efficacy of PPT and reported that the NPC after the treatment in 98.9% of patients was less than 10 cm, in 95.7% less than 8.5 cm and in 80.4% less than 6.5 cm. Their results were similar to our study in that the mean NPC decreased from 13.0 cm to 8.5 cm in the PPT group.

Gallaway et al.18 investigated the efficacy of the treatment of CI by using PPT and indicated that therapy was valuable in 58% of cases in normalization of NPC, and in 91.7% of cases reduced the patient's symptoms. These observations were confirmed in our study.

Birnbaum et al. (1999) compared home-based therapy combined with office-based therapy and home-based therapy alone in adults with CI and reported success rates of 61.9% and 30%, respectively.9 They cited the efficacy of home-based therapy as insignificant in comparison with office-based therapy,9 which contradicts our results except with regard to positive fusional vergence.

Cacho Martinez et al.19 performed a systematic review of the literature from 1986 to 2007 using four major medical databases and strict inclusion criteria. Reviewing 16 studies performed over 20 years, of which only three were clinical trials, the authors concluded that optical treatment of CI with prism in pre-presbyopes was no more effective than placebo, and that PPT was not as effective as other forms of vision therapy, such as office-based.19 Pencil push-ups were still modestly effective, however, which may be one reason they are still used, as reported in the current study.

By comparison, office-based vision therapy for CI uses more advanced targets with sophisticated suppression control. Whether it is with analog vectograms with polarized passive 3D filters, or computer orthoptics with active 3D flicker glasses, it is not surprising that office-based vision therapy techniques are robust and quickly effective.

Why, then, do pencil push-ups remain so popular among the eye care providers as a treatment option? The likely reasons include the simplicity, accessibility, and affordability of this treatment. With CI, the most common of the Duane-White accommodative-vergence syndromes, it is likely that the capacity of patients with this condition exceeds the number of vision therapy practitioners in many parts of the world.

Even in areas where office-based vision therapy for convergence insufficiency is readily available, there is a commitment in time and financial resources that may make patients choose home-based PPT. As long as this remains true, the very humble pencil push-up with suppression control should remain a second-choice option with which patients with CI are presented as part of informed consent.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank participants who made this study possible. We thank Prof. Mitchell Scheiman for very helpful comments on an earlier draft.

APPENDIX A

Convergence insufficiency symptom survey (CISS) questionnaire used for study, entitled the effectiveness of home-based pencil push-up therapy versus office-based therapy for the treatment of symptomatic convergence insufficiency in young adults

Footnotes

Source of Support: Zahedan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dusek WA, Pierscionek BK, McClelland JF. An evaluation of clinical treatment of convergence insufficiency for children with reading difficulties. BMC Ophthalmol. 2011;11:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans BW. Pickwell's binocular vision anomalies: Investigation and treatment. 5th ed. London: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2002. pp. 124–32. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffin JR, Grisham JD. Binocular anomalies: Diagnosis and vision therapy. 4th ed. Boston, Mass: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2002. pp. 412–27. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheiman M, Wick B. Clinical management of binocular vision: Heterophoric, accommodative and eye movement disorders. Philadaephia, Pa: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. pp. 241–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheiman M, Cooper J, Mitchell GL, de LP, Cotter S, Borsting E, et al. A survey of treatment modalities for convergence insufficiency. Optom Vis Sci. 2002;79:151–7. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200203000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavrich JB. Convergence insufficiency and its current treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21:356–60. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32833cf03a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnoldi K, Reynolds JD. A review of convergence insufficiency: What are we really accomplishing with exercises? Am Orthoptic J. 2007;57:123–30. doi: 10.3368/aoj.57.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aziz S, Cleary M, Stewart HK, Weir CR. Are orthoptics exercises an effective treatment for convergence and fusion deficiencies? Strabismus. 2006;14:183–9. doi: 10.1080/09273970601026185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birnbaum MH, Soden R, Cohen AH. Efficacy of vision therapy for convergence insufficiency in an adult male population. J Am Optom Assoc. 1999;70:225–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KM, Chun BY. Effectiveness of home-based pencil push-ups (HBPP) for patients with symptomatic convergence insufficiency. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2011;25:185–8. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2011.25.3.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patwardhan SD, Sharma P, Saxena R, Khanduja SK. Preferred clinical practice in convergence insufficiency in India: A survey. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:303–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.39661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, Kulp MT, Cooper J, Rouse M, et al. A randomized clinical trial of vision therapy/orthoptics versus pencil pushups for the treatment of convergence insufficiency in young adults. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82:583–95. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000171331.36871.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borsting E, Mitchell GL, Kulp MT, Scheiman M, Amster DM, Cotter S, et al. Improvement in academic behaviors after successful treatment of convergence insufficiency. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89:12–8. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318238ffc3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rouse MW, Borsting EJ, Mitchell GL, Scheiman M, Cotter SA, Cooper J, et al. Validity and reliability of the revised convergence insufficiency symptom survey in adults. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2004;24:384–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2004.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheiman M, Gallaway M, Frantz KA, Peters RJ, Hatch S, Cuff M, et al. Near point of convergence: Test procedure, target selection, and normative data. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80:214–25. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200303000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheiman M, Cotter S, Rouse M, Mitchell GL, Kulp M, Cooper J, et al. Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Study Group. Randomised clinical trial of the effectiveness of base-in prism reading glasses versus placebo reading glasses for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1318–23. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.068197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brautaset RL, Jennings AJ. Effects of orthoptic treatment on the CA/C and AC/A ratios in convergence insufficiency. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2876–80. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallaway M, Scheiman M, Malhotra K. The effectiveness of pencil pushups treatment for convergence in sufficiency: A pilot study. Optom Vis Sci. 2002;79:265–7. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200204000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cacho Martínez P, García Muñoz A, Ruiz-Cantero MT. Treatment of accommodative and nonstrabismic binocular dysfunctions: A systematic review. Optometry. 2009;80:702–16. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]