Abstract

Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (IPEH) (Masson's tumor) is an unusual benign vascular lesion of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, consisting of papillary formations related to a thrombus and covered by a single layer of plump endothelial cells. The lesion is often mistaken with angiosarcoma and a group of other benign and malignant vascular lesions. The clinical and radiological findings are not specific, and the diagnosis is based on the histological examination. Intracranial lesions are extremely rare with only 32 cases been reported in the literature. Only two cases of IPEH presenting as scalp swelling have been reported in the literature. We report a case of a 3-month-old boy with IPEH of scalp in the left parietal region, which was involving the skull bone and extending intracranially.

Keywords: Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia, Masson's tumor, scalp swelling

Introduction

Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (IPEH) (Masson's tumor) is a rare benign vascular lesion of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, occurring mainly in the fingers, trunk, and head-neck region.[1,2] Tumors with intracranial location or extension are extremely rare with only 32 cases been reported in the literature.[3] Only two cases of IPEH presenting as scalp swelling have been reported in the literature.[4,5] It needs to be differentiated from the malignant angiosarcoma because complete excision can lead to cure and prevent the patient from undergoing unnecessary adjuvant therapy.[1,6,7] We report a case of a 3-month-old boy with IPEH of scalp, which was involving the left parietal bone and extending intracranially.

Case Report

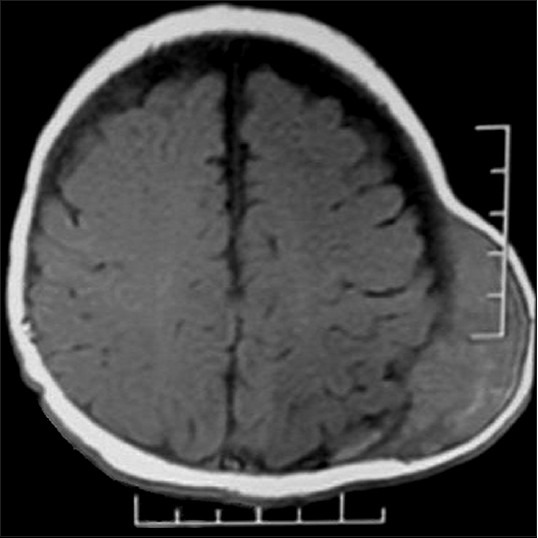

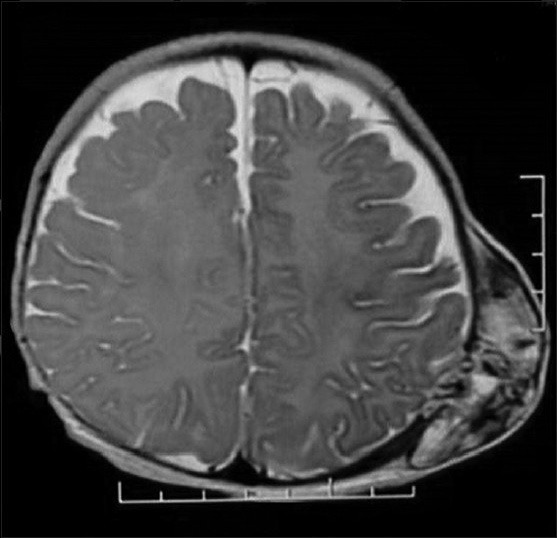

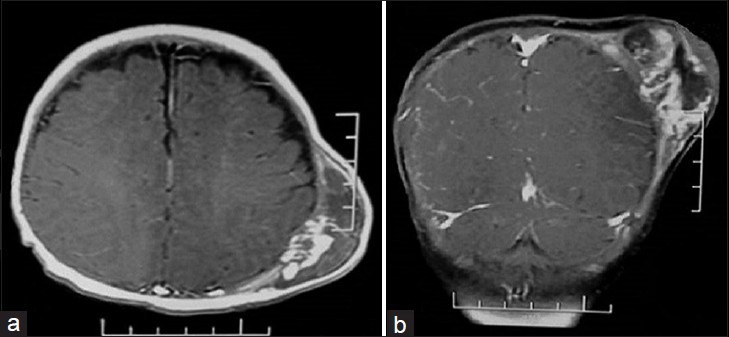

A 3-month-old male child was referred for a scalp swelling present since 2 months, which was initially small and slow growing but suddenly increased in size in last 2 days. There was no definitive history of trauma. On examination, the patient was neurologically normal. There was a firm, bluish swelling in the left parietal region. There were no abnormal pulsations. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain showed a heterogeneous altered signal intensity lesion of size 60 × 53 × 31 mm involving extra-calvarial soft tissue in left parietal region. It appeared isointense on T1-weighted images [Figure 1] and heterogeneously hyperintense on T2-weighted images. T2-weighted images showed multiple flow voids suggestive of multiple vascular channels within the lesion [Figure 2]. The lesion involved the skull vault with evidence of intracranial extension of the lesion. Intense enhancement was seen on postcontrast gadolinium study [Figure 3a and b].

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging axial T1-weighted images showing an isointense lesion with intracranial extension

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging axial T2-weighted images showing a heterogeneously hyperintense lesion with multiple flow voids

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging postcontrast images (a: Axial, b: Coronal) showing intense heterogeneous enhancement

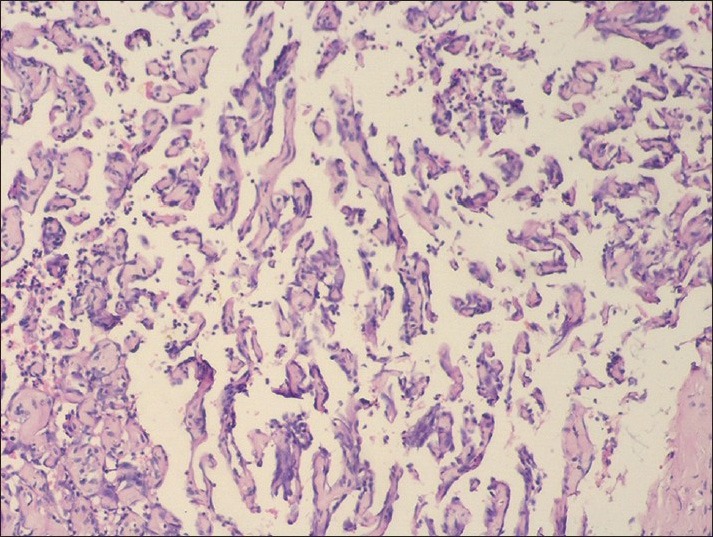

Total excision of the tumor was done along with a wide margin. The tumor was highly vascular, associated with a hematoma and eroding the left parietal bone, creating a bony defect through which it was extending in the extradural space. The dura was intact. Histopathology sections showed a well-circumscribed mass within the blood vessels with multiple small, delicate, papillary structures projecting into the lumen and were associated with thrombus formation. These papillae were lined by single layer of plump endothelial cells. There were clumping and fusion of papillae, forming an anastomosing network of blood vessels set in a loose mesh like connective tissue [Figure 4]. There were no areas of necrosis and little or no atypia. Postoperative period was uneventful. Patient's neurological evaluation was normal at the time of discharge. Patient was asymptomatic on follow-up after 1 year, and a repeat MRI showed no recurrence of tumor.

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph showing papillary projections within the vascular lumen, having a fibrin core and lined by plump endothelial cells (H and E, ×40)

Discussion

Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia was first described by Pierre Masson in 1923 by the term hémangioendothéliome végétant intravasculaire. Since then, it has also been called Masson's tumor, Masson's hemangioma, Masson's pseudoangiosarcoma, Masson's vegetant intravascular hemangioendothelioma and intravascular angiomatosis.[6,7] Clearkin and Enzinger coined the term “IPEH,” who suggested that the thrombosis takes place before the papillary proliferation and that the thrombotic material provides a matrix for its development.[8] Three types of IPEH have been described: A primary form arising within a normal blood vessel (usually a vein), a secondary form developing in a preexisting vascular malformation (usually a cavernous hemangioma or pyogenic granuloma), and an extravascular form (arising in an organizing hematoma).[2,6]

It occurs mainly in the skin and subcutaneous soft tissue of fingers, trunk, and head-neck region, however can occur in any area of the body.[1,2,9] IPEH presenting as an intracranial lesion is very rare, with only 32 cases reported in the literature.[3] Only two cases of IPEH presenting as scalp swelling have been reported in the literature. One of these cases presented with a right frontal palpable mass with skull involvement.[4] The other case was reported in an aneurysm of left superficial temporal artery.[5] Signs and symptoms of intracranial IPEH depend on the location of the tumor. The age at manifestation varies widely, and there seems to be a slight female predominance.[3]

Various skull lesions may radiologically mimic the appearance of IPEH. IPEH shows enhancement on computerized tomography imaging, but cannot be differentiated from other skull tumors such as eosinophilic granuloma, hemangioma, and metastatic tumors. Hemorrhage is commonly present. On MRI the tumor is hypointense or isointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Gadolinium-enhanced scans show enhancement thus demonstrating the extremely vascular nature of IPEH.[3,10] There are no specific radiological features that characterize IPEH, and the final diagnosis requires careful histological examination.

Microscopically, short blunted papillary projections with a hyalinized core are associated with thrombotic or clot material and are covered with a single layer of plump endothelial cells. There is no multilayering, tufting, solid areas, necrosis and little or no atypia. There is little evidence of mitoses.[8] Masson's tumor is a benign condition that must be distinguished from epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, Kaposi's sarcoma, and malignant angiosarcoma, since the lesion is, usually, curable by surgical excision alone.[6,7] Unlike angiosarcoma, Masson's tumor is, usually, confined to the blood vessel (passive extension may occur following rupture of the vessel), and there is no evidence of pleomorphism, tissue necrosis and mitoses.[1,6,7]

Treatment of IPEH is complete surgical excision.[3,4] In our case, since the tumor was easily accessible, complete resection was possible, and there was no recurrence on follow-up MRI after 1 year. However, with subtotal resection in case of intracranial tumors where complete removal is not possible, recurrence or progression may be seen.[9] Close observation with serial imaging is indicated in such patients. In cases of progression or recurrence, postoperative radiotherapy[9,10] or gamma knife radiosurgery[10] should be considered as the main adjuvant therapy. Role of chemotherapy remains unclear.[3,4] Due to the small number of reported cases, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the efficacy of adjuvant treatment.

Conclusion

Although benign IPEH is clinically important because it presents as a mass lesion that is often misdiagnosed radiologically and may be mistaken histologically for angiosarcoma. Complete surgical excision leads to cure and therefore correct diagnosis helps avoid the need for further therapy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Jayesh A. Shelat (Professor and Head, Department of Neurosurgery, B.J. Medical College and Civil Hospital, Ahmedabad) for his valuable support and instructions on this paper and Dr. Sanjay V. Dhotre (Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, B.J. Medical College and Civil Hospital, Ahmedabad) for the histopathological diagnosis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Salyer WR, Salyer DC. Intravascular angiomatosis: Development and distinction from angiosarcoma. Cancer. 1975;36:995–1001. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197509)36:3<995::aid-cncr2820360323>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hashimoto H, Daimaru Y, Enjoji M. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. A clinicopathologic study of 91 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:539–46. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong SS, Bruner J, Schellingerhout D, Puduvalli VK. Papillary endothelial hyperplasia presenting as recurrent malignant glioma. J Neurooncol. 2011;102:491–8. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0338-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park KK, Won YS, Yang JY, Choi CS, Han KY. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (Masson tumor) of the skull: Case report and literature review. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;52:52–4. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2012.52.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriyama S, Kunitomo R, Sakaguchi H, Okamoto K, Sasa T, Tanaka M, et al. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia in an aneurysm of the superficial temporal artery: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2011;41:1450–4. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4499-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoffman MR, Kim JH. Masson's vegetant hemangioendothelioma: Case report and literature review. J Neurooncol. 2003;61:17–22. doi: 10.1023/a:1021248504923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuo T, Sayers CP, Rosai J. Masson's “vegetant intravascular hemangioendothelioma:” A lesion often mistaken for angiosarcoma: Study of seventeen cases located in the skin and soft tissues. Cancer. 1976;38:1227–36. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197609)38:3<1227::aid-cncr2820380324>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clearkin KP, Enzinger FM. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1976;100:441–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avellino AM, Grant GA, Harris AB, Wallace SK, Shaw CM. Recurrent intracranial Masson's vegetant intravascular hemangioendothelioma. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:308–12. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.2.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohshima T, Ogura K, Nakayashiki N, Tachibana E. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia at the superior orbital fissure: Report of a case successfully treated with gamma knife radiosurgery. Surg Neurol. 2005;64:266–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]