Abstract

Scalp arteriovenous malformations are an exceptional group of vascular lesions with curious presentations and an elusive natural history. Their detection in the pediatric population is a rarer occurrence. We discuss our experience with five children suffering from this pathology and their surgical management carried at our institution from 2007 to 2013. The genesis in pediatric patients is, usually, spontaneous in contrast with the history of trauma seen in adults. Clinical symptoms, usually, range from an asymptomatic lesion, local discomfort, headaches to necrosis and massive hemorrhage. Selective angiography remains the cornerstone for investigation. Complete surgical excision, embolization or an approach combining the modalities is curative.

Keywords: Angiography, arteriovenous malformation, pediatric, scalp, surgical excision

Introduction

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) of the scalp are peculiar lesions with even rarer presentation in the pediatric population. A well-known fact states their origin attributable to anomalous primitive fistulous connection between feeding arteries and draining veins, with the absence of intervening capillary bed. This state of high shunt flow between the two distinct vessel types and the complex vascular anatomy makes their treatment a challenging undertaking.

Historically their unusual portly appearance led to various synonyms being coined for the entity viz., aneurysm cirsoide, aneurysm serpentinum, aneurysm racemosum, aneurysm by anastmoses, aneurysmal varix, arteriovenous fistula, plexiform angioma.[1]

We encountered five cases of pediatric AVMs with their varied presentations between 2007 and 2013 [Table 1]. Their management strategy, treatments and outcomes are also discussed. This is first case series highlighting the nuances of this pathology in pediatric age group.

Table 1.

Case summary of patients with scalp AVMs*

Case Reports

Case 1

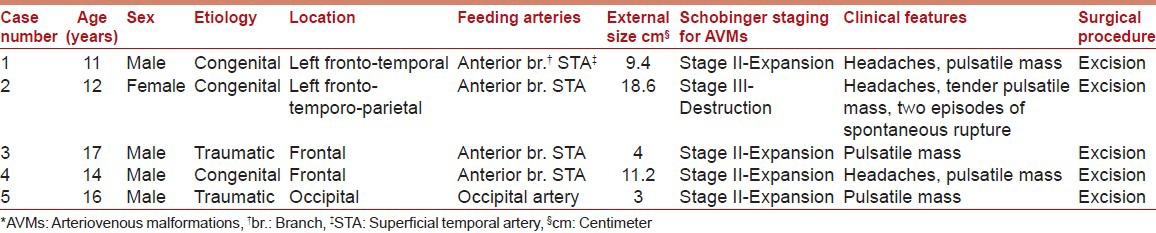

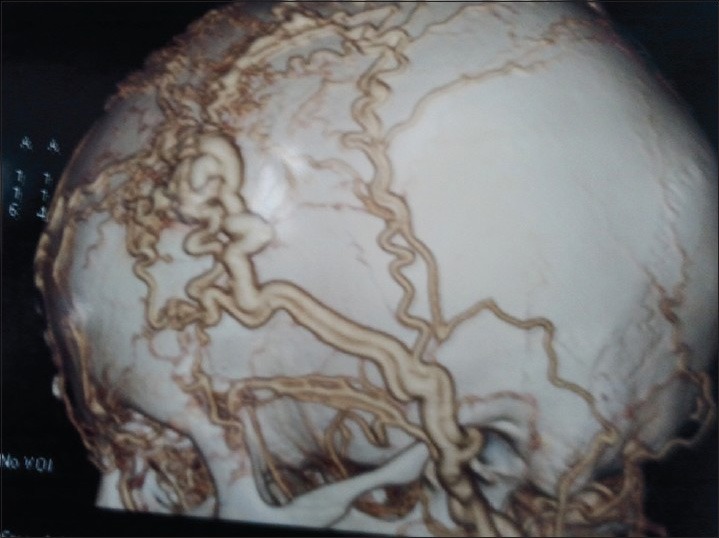

An 11-year-old male child presented with a 6 years history of a left fronto-temporal throbbing scalp swelling and occasional headaches. The swelling was initially inconspicuous and gradually progressed. There was no previous history of trauma, head injury or birthmarks. Examination revealed a pulsatile swelling, 9.4 cm in size with bluish discoloration of scalp [Figure 1]. It was mobile over the skull and demonstrated a bruit upon auscultation. Cerebral angiography showed moderate dilatation of the superficial temporal artery and its frontal branch with a serpiginous collection of vessels in the fronto-temporal region [Figure 2]. The mass was excised following ligation of feeding vessels.

Figure 1.

Left frontal scalp arteriovenous malformation in a 11-year-old (Case 1)

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of carotid angiogram showing scalp arteriovenous malformation arising from anterior branch of superficial temporal artery

Case 2

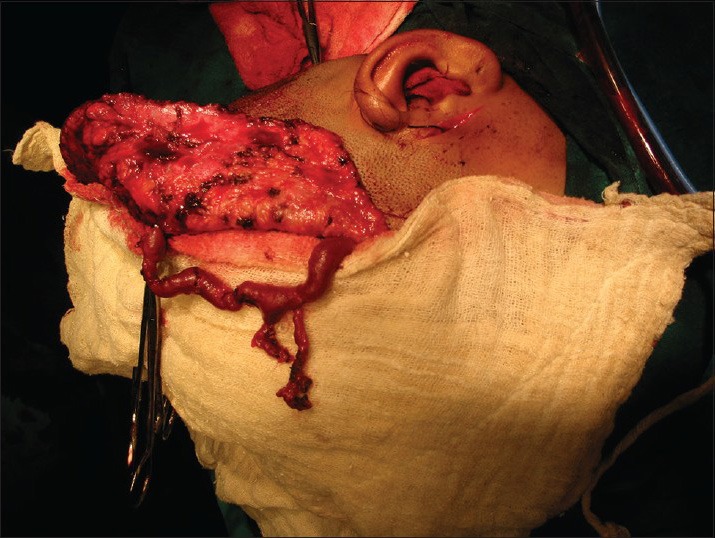

A 12-year-old girl came to our hospital with a spontaneous bleeding from a large left fronto-temporo-parietal scalp swelling which was present since birth and gradually attained its present size. She complained of infrequent headaches, and the swelling had spontaneously bled at a previous occasion 1 month back and had resulted in severe hemodynamic shock for which the patient was treated elsewhere. A large 18.6 cm fronto-temporo-parietal, pulsatile scalp swelling with a scar from previous hemorrhage was observed [Figure 3]. The angiogram revealed moderate dilatation of left superficial temporal artery (STA) with gross dilatation and tortuous course of its frontal branch along its entire length. After hemodynamic stabilization, the patient underwent resection of the lesion after attaining proximal control [Figure 4]. She remains asymptomatic till date.

Figure 3.

A large fronto-temporo-parietal pulsatile mass with history of recurrent bleeding

Figure 4.

Intra-operative image (Case 2) showing complete excision of scalp arteriovenous malformation

Case 5

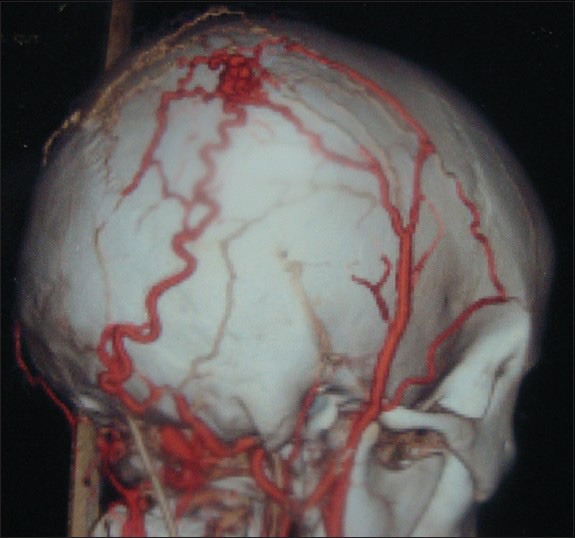

A 16-year-old male attended the outpatient department with a swelling over the occipital region since 2 years. The onset of lesion was following a trivial trauma to the occipital region by a brick. Even though the patient was asymptomatic, the swelling bothered him while combing his hair. Examination showed a small (3 cm) pulsatile mass over the occiput. Angiogram displayed an AVM over the occipital region at the region of confluence of occipital artery and parietal branch of STA [Figure 5]. Surgical resection of the lesion was done with proximal and distal vessel ligation.

Figure 5.

Carotid angiogram showing an occipital scalp arteriovenous malformation fed by occipital artery

Discussion

Arteriovenous malformations in the pediatric population are a singular occurrence. They are 20 times more common in the brain involving or supplied by intracranial vasculature than those formed by branches of external carotid arteries.[2] When occurring in scalp, AVMs are noticed in late childhood, adolescent or early adulthood, when substantial esthetic and social disturbance necessitate their treatment.[3] The pediatric lesions differ from adult AVMs in terms of their etiology, age of presentation, cosmetic impact and excellent outcome with early management.

Khodadad proposed four major etiologies causative of AVMs viz. Congenital, Traumatic, Infection and Inflammation and Familial.[1] Of these, the congenital occurrence is a predominant finding amongst young age group. Congenital and traumatic causes were the only ones our patients presented with various explanations for the formation of congenital AVMs have been proposed: persistent primitive arteriovenous communications, vascular hamartomas, fistula formation between arteries and veins. On the other hand, traumatic AVMs are attributed to fistula formation only.[1]

Traumatic AVMs can occur at any age whereas symptomatic congenital AVMs are not common until the second decade of life. This has been attributed to mechanical trauma, vasomotor disturbance, inflammation or endocrine stimulation (pregnancy or puberty) which may rupture the thin embryonic membrane between the fistulous connection or promote uncontrolled growth of vessels.[1,4] This was also noted in our cases. Cervicofacial involvement is most common in the cheeks, ears, nose, and less commonly forehead.[3] The subcutaneous tissue of the scalp is supplied by external carotid, occipital and supraorbital arteries. Of these, the region supplied by STA is most frequently affected owing to its long unprotected course.[5,6]

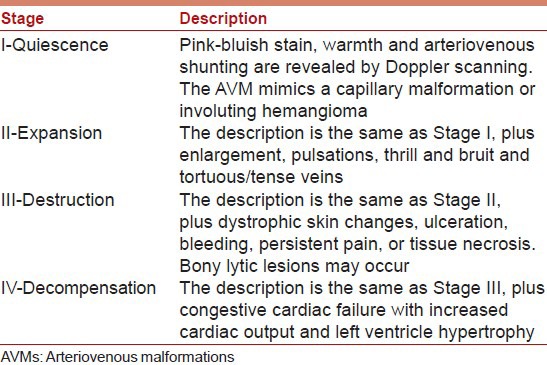

Disease progression of scalp AVMs not only renders the swelling bigger but presents with a wide array of clinical manifestations. Physical disfigurement, throbbing sensations, tinnitus and headaches are mostly associated in early stages. Persistent pain, scalp necrosis, bone erosion, life-threatening hemorrhage, cardiovascular failure, cerebral steal phenomenon and seizures are symptomatology of late destructive and decompensated lesions.[1,3] Shenoy and Raja documented two cases in their series with bleeding from the lesion as was noted in one of our case and is associated with large vascular lesions.[7] The disease advancement and presentation is appropriately taken into account in Schobinger's Classification of AVMs [Table 2].[3] In our patients, four cases belonged to Stage II that is, “Stage of Expansion” and one categorized as Stage III; “Stage of Destruction” lesion.

Table 2.

Schobinger staging for AVMs[3]

Cranial angiography is of great merit in achieving a quality diagnosis and treatment selection. This is also helpful in surgical planning. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also of significance in establishing a diagnosis.[8] MRI also aids in identifying any intracranial extension or involvement neither of which were found in our cases. Selective angiography must be done to rule out other differentials such as aneurysms, sinus pericranii, venous malformation and cavernous hemangioma.[8]

The therapeutic modalities available to manage these lesions include: Surgical excision, vessel ligation, transarterial or transvenous embolization, sclerosant injection into nidus and electrothrombosis.[9] Combined approach with preoperative embolization followed by surgical excision has been described with excellent results.[10,11] Percutaneous direct puncture coil embolization of cirsoid aneurysms is a safe and effective procedure. It can be effectively used as an alternative to surgery.[12] Barnwell et al. treated eight patients with scalp AVMs successfully using coil embolization of the main vessel, followed by injection of embolic agents to occlude the collateral supply.[5] Direct puncture embolization and transarterial embolization as an adjunct to it (in 4 patients), were used in 15 patients by Gupta et al. They achieved effective embolization with single sitting procedure in 11 patients, two patients required multiple sittings and two required surgical resection of lesions for cosmetic reasons. This study emphasizes endovascular management as a successful treatment modality and highlights the role of surgery as a definitive therapeutic option.[12]

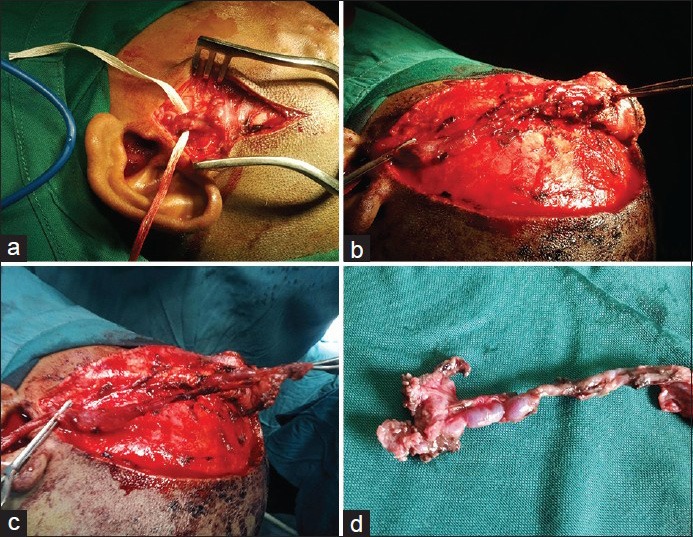

Well-planned surgery of cirsoid aneurysm of the scalp without preoperative interventions can also achieve complete excision of the lesion without any residual masses or recurrence and with a low incidence of complications.[13] However, excision of secondary scalp venous dilatation without treatment of intracranial component can be dangerous.[7] All our patients underwent complete surgical excision of the AVM nidus with ligation of proximal and distal draining vessels with excellent cosmetic results and without recurrences. The procedure involves achieving proximal control of the feeding vessel, fashioning the scalp flap depending upon the anatomy of nidus and raising it with pericranium, the feeding vessels are traced distally to nidus by incising the galea, vessels traced distally towards the nidus; ligated and divided and malformation separated from galea by incising it circumferentially [Figure 6a–d]. Endovascular therapy is a valid therapeutic option for AVMs but surgical excision remains the most successful curative modality for complex, recurrent and otherwise usual scalp AVMs. A successful outcome depends on complete removal of the AVM, secure ligation of proximal and distal vessels and preeminent prudence for cosmesis.

Figure 6.

Operative steps of arteriovenous malformation (AVM) excision: (a) Achieving proximal control of superficial temporal artery, (b) raising of scalp flap, (c) dissection of vessels from galea and ligation, (d) specimen of AVM

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Khodadad G. Arteriovenous malformations of the scalp. Ann Surg. 1973;177:79–85. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197301000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinzweig N, Chin G, Polley J, Charbel F, Shownkeen H, Debrun G. Arteriovenous malformation of the forehead, anterior scalp, and nasal dorsum. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2433–9. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200006000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schobinger MP, Hansen M, Pribaz JJ, Mulliken JB. Arteriovenous malformations of the head and neck: Natural history and management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:643–54. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199809030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher-Jeffes ND, Domingo Z, Madden M, de Villiers JC. Arteriovenous malformations of the scalp. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:656–60. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199504000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnwell SL, Halbach VV, Dowd CF, Higashida RT, Hieshima GB. Endovascular treatment of scalp arteriovenous fistulas associated with a large vari. Radiology. 1989;173:533–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.173.2.2798886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burrus TM, Miller GM, Flynn LP, Fulgham JR, Lanzino G. NeuroImages. Symptomatic left temporal arteriovenous traumatic fistula. Neurology. 2009;73:570. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b2a6f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shenoy SN, Raja A. Scalp arteriovenous malformations. Neurol India. 2004;52:478–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasturk AE, Erten F, Ayata T. Giant non-traumatic arteriovenous malformation of the scalp. Asian J Neurosurg. 2012;7:39–41. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.95698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurkanlar D, Gonul M, Solmaz I, Gonul E. Cirsoid aneurysms of the scalp. Neurosurg Rev. 2006;29:208–12. doi: 10.1007/s10143-006-0023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagasaka S, Fukushima T, Goto K, Ohjimi H, Iwabuchi S, Maehara F. Treatment of scalp arteriovenous malformation. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:671–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar R, Sharma G, Sharma BS. Management of scalp arterio-venous malformation: Case series and review of literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2012;26:371–7. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2012.654838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta AK, Purkayastha S, Bodhey NK, Kapilamoorthy TR, Krishnamoorthy T, Kesavadas C, et al. Endovascular treatment of scalp cirsoid aneurysms. Neurol India. 2008;56:167–72. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.41995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Shazly AA, Saoud KM. Results of surgical excision of cirsoid aneurysm of the scalp without preoperative interventions. Asian J Neurosurg. 2012;7:191–6. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.106651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]