Abstract

Acute muscle pain and walking difficulty are symptoms compatible with both benign and severe degenerative diseases. As a consequence, in some cases invasive tests and hospitalizations are improperly scheduled. We report the case of a 7-year-old child suffering from acute calf pain and abnormal gait following flu-like symptoms. A review of the literature will be helpful to better define differential diagnosis in cases of muscle pain in children. Daily physical examination and urine dipstick are sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of benign acute childhood myositis (BACM) during the acute phase, to promptly detect severe complications and to rule out degenerative diseases. Children with BACM do not require hospitalization, medical interventions or long-term follow-up.

Keywords: Benign acute childhood myositis, children, differential diagnosis, myositis

Introduction

Benign acute childhood myositis (BACM) is a self-limiting process characterized by sudden onset of muscle pain, more often calf pain, manifested by walking difficulty.[1,2,3,4] Since many clinicians are not familiar with BACM,[2] it is often misdiagnosed and interpreted as a more severe and complex disease.[2,5,6] We report the case of a patient suffering from BACM in absence of any previous documented viral infections. We underline how medical history and clinical examination are sufficient for a correct diagnosis of BACM, as well as to avoid unnecessary tests. Based on the previous reports, we updated etiology and clinical data of BACM, and we propose differential diagnosis of muscle pain in children.

Case Report

A 7-year-old boy with acute calf pain and progressive walking difficulty was referred to our pediatric center to rule out muscle degenerative diseases. Two days earlier the child had suffered from fever, cough, malaise and rhinorrhea, which promptly resolved. The onset of calf pain was early in the morning, and it was so sharp that he had to walk on his heels mimicking a spastic gait. Family history was not informative for neuromuscular disorders. The child had undergone all compulsory vaccinations, and his previous clinical history was not suggestive of any remarkable diseases. No travels, trauma, vigorous exercise or similar episodes of limb pain were reported before onset of symptoms.

On admission, the patient was alert and complained of fatigue and bilateral calf pain. Vital signs were normal, and he was apyretic. There was no evidence of trauma to the lower limbs. Neurological examination revealed normal muscle power and tone. Tendon reflexes and sensitivity of the upper and lower limbs were also normal. At rest, the patient kept his feet in slight plantar flexion. Gastrocnemius-soleus muscles on both sides were soft on palpation, and there were no inflammatory changes. Passive dorsiflexion of the ankles caused sharp pain as well as passive stretching and gentle palpation of his calves. Despite normal neurological examination, the patient was hospitalized in order to allow medical observation and exclude severe diseases. On admission laboratory tests showed a significant increase in blood levels of creatinine phosphokinase (2161 U/L, normal range <227 U/L), alanine transaminase (69 U/L, normal range: 0-45) and aspartate transaminase (92 U/L, normal range: 17-59). C-reactive protein (<0.20 mg/L) and white blood cell count (7400/μL) were within normal limits. Complete blood count, electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time and other routine blood parameters were also within normal limits. Urinalysis was normal and no myoglobulin, blood or proteins were detected. Throat culture was positive only for resident bacteria. Viral tests for influenza A/B and H1N1 influenza A virus was negative. Furthermore, serological tests ruled out recent viral infections by adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, cytomegalovirus, herpes virus and Epstein–Barr virus, as well as serological tests for mycoplasma pneumonia. Since the patient refused to eat and drink, he received intravenous hydration for 24 h. During the 2nd day of hospitalization pain spontaneously resolved and a normal gait was regained.

Considering that daily urine output was normal, the boy was discharged, and no long-term follow-up was required. Today the child does not present any neurological sequelae.

Discussion

Benign acute childhood myositis is a self-limiting process which frequently affects the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. In a review of 2004, 316 cases of influenza-associated myositis were analysed.[4] Other agents such as enterovirus, mycoplasma pneumonia and dengue virus have been involved in the process.[2,7] Furthermore, five cases of BACM following H1N1 influenza A virus infection[5,6] and human parainfluenza virus type 1 infection[8] have been reported. In most cases, the disease is self-limiting and when the myositis develops the patient is already in the early convalescent phase of the viral illness. Nevertheless, it is reported that 10/316 children (3%) developed severe rhabdomyolysis, and temporary dialysis was necessary in six cases.[4]

During winter 2007–2008, influenza B virus was responsible for a large number of cases of BACM in Germany, especially among male children aged from 6 to 9 years.[2] Median time between the onset of fever and the beginning of BACM symptoms was 3 days. Despite the clinical course of BACM being well described, Mall et al. showed that only 24% of 165 participating physicians were able to recognize BACM.[2] Furthermore, the exact current incidence, prevalence and pathogenesis of BACM are not known.

Although most patients are children, BACM has also been described in adolescents.[7] This could simply be explained by the increased tropism of viruses for immature muscle cells.[2] Furthermore, each virus could act as a trigger in genetically predisposed children and in few patients with undiagnosed metabolic diseases.[2,6]

Benign acute childhood myositis does not require any invasive tests or medical therapy. Nevertheless, the onset may be mistaken for very severe neurological illness such as Guillain–Barrè syndrome or chronic autoimmune diseases. As a consequence unnecessary invasive tests, such as radiography, echocardiography, electromyography and magnetic resonance are still performed.[2,7,8] On the contrary, daily medical examination and urine dipstick (with measurement of myoglobin) are sufficient to promptly detect complications and rule out more severe illnesses and creatine kinase (CK) should be measured only at diagnosis in order to early exclude degenerative diseases. Some authors highlight how CK levels do not correlate with BACM severity.[2] Viral tests for BACM-related viruses should not be routinely performed because of the time interval between infection and seroconversion. Moreover, not always etiological agents can be found, and antiviral drugs are not usually recommended. Nevertheless, influenza test may be useful since influenza viruses can affect the severity of BACM.[9,10]

Once symptoms have resolved, the patient does not require any follow-up. However, parents should be encouraged to monitor the child's urine output and the appearance of Coca-Cola colored urine and swollen legs. Hospitalization should be scheduled only when the patient's parents do not seem able to monitor the condition of their child at home.

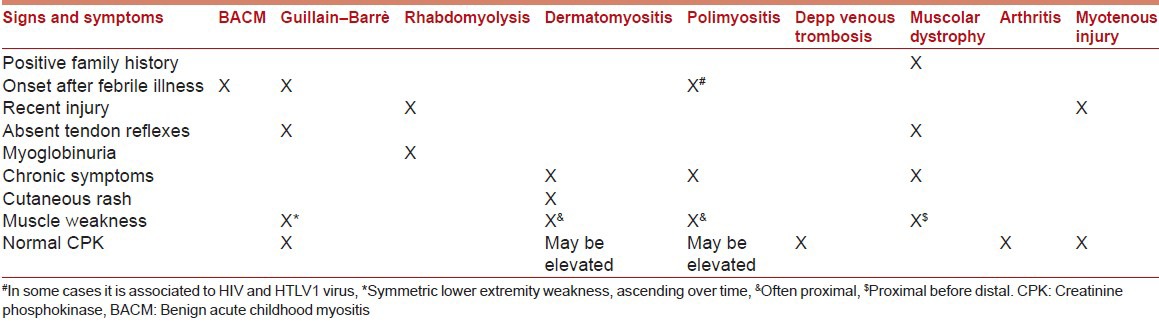

We report signs and symptoms which can help clinicians to make a correct differential diagnosis when a child suffers from acute muscle pain in Table 1. BACM typically manifests with acute myositis and increased CK level, following a viral infection. A family history of neuromuscular disorders, myoglobinuria, trauma, chronic progression, rash, edema, muscle weakness or neurological diseases are not typically associated to BACM; in these cases further investigation is required.

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of most common myositis in children

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Lundberg A. Myalgia cruris epidemica. Acta Paediatr. 1957;46:18–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1957.tb08627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mall S, Buchholz U, Tibussek D, Jurke A, An der Heiden M, Diedrich S, et al. A large outbreak of influenza B-associated benign acute childhood myositis in Germany, 2007/2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:E142–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318217e356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Middleton PJ, Alexander RM, Szymanski MT. Severe myositis during recovery from influenza. Lancet. 1970;2:533–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)91343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agyeman P, Duppenthaler A, Heininger U, Aebi C. Influenza-associated myositis in children. Infection. 2004;32:199–203. doi: 10.1007/s15010-004-4003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koliou M, Hadjiloizou S, Ourani S, Demosthenous A, Hadjidemetriou A. A case of benign acute childhood myositis associated with influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:193–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubín E, De la Rubia L, Pascual A, Domínguez J, Flores C. Benign acute myositis associated with H1N1 influenza A virus infection. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:1159–61. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dandolo A, Banerjee A. Benign acute myositis in a 17-year-old boy. Arch Pediatr. 2013;20:779–82. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tippett E, Clark R. Benign acute childhood myositis following human parainfluenza virus type-1 infection. Emerg Med Australas. 2013;25:248–51. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swaringen JC, Seiler JG, 3rd, Bruce RW., Jr Influenza A induced rhabdomyolysis resulting in extensive compartment syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000:243–9. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200006000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu JJ, Kao CL, Lee PI, Chen CM, Lee CY, Lu CY, et al. Clinical features of influenza A and B in children and association with myositis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2004;37:95–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]