Abstract

Background

Mesorhizobium alhagi CCNWXJ12-2 is a α-proteobacterium which could be able to fix nitrogen in the nodules formed with Alhagi sparsifolia in northwest of China. Desiccation and high salinity are the two major environmental problems faced by M. alhagi CCNWXJ12-2. In order to identify genes involved in salt-stress adaption, a global transcriptional analysis of M. alhagi CCNWXJ12-2 growing under salt-free and high salt conditions was carried out. The next generation sequencing technology, RNA-Seq, was used to obtain the transcription profiles.

Results

We have compared the transcriptome of M. alhagi growing in TY medium under high salt conditions (0.4 M NaCl) with salt free conditions as a control. A total of 1,849 differentially expressed genes (fold change ≧ 2) were identified and 933 genes were downregulated while 916 genes were upregulated under high salt condition. Except for the upregulation of some genes proven to be involved in salt resistance, we found that the expression levels of protein secretion systems were changed under high salt condition and the expression levels of some heat shock proteins were reduced by salt stress. Notably, a gene encoding YadA domain-containing protein (yadA), a gene encoding trimethylamine methyltransferase (mttB) and a gene encoding formate--tetrahydrofolate ligase (fhs) were highly upregulated. Growth analysis of the three gene knockout mutants under salt stress demonstrated that yadA was involved in salt resistance while the other two were not.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first report about transcriptome analysis of a rhizobia using RNA-Seq to elucidate the salt resistance mechanism. Our results showed the complex mechanism of bacterial adaption to salt stress and it was a systematic work for bacteria to cope with the high salinity environmental problems. Therefore, these results could be helpful for further investigation of the bacterial salt resistance mechanism.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12866-014-0319-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Salt stress, RNA-Seq, Secretion system, Chaperones, Mesorhizobium alhagi

Background

Mesorhizobium alhagi CCNWXJ12-2, was classified as a high salt-tolerant rhizobium, which could be able to form nitrogen-fixing symbiosis with desert plant Alhagi sparsifolia [1]. Alhagi sparsifolia has a large distribution in the southern fringe of Taklamakan Desert and it plays an important role in windbreaker and sand fixation and social-economy at that area [2]. Undoubtedly, salinity and desiccation, are severe problems facing the agricultural industry due to cases the degradation of soil quality [3]. Almost 40% of the world’s land surface are troubled by salinity [4]. These condition has detrimental effects on the Rhizobium-Legume symbiosis in different ways such as the growth and survival of rhizobia in soil colonization around the root and interaction between rhizobia and legumes or functions of the nodules [5]. In order to form efficient nitrogen-fixing symbiosis, the rhizobia should have high salt resistance to be able to survive in salty soils. Therefore, in recent years the number of studies on salt-tolerant rhizobia and the mechanism of salt resistance are increasing. In particular, most of the articles focus on the isolation of salt-tolerant rhizobia or some specific genes involved in salt resistance [6-10]. Nevertheless, the salt resistance mechanism in rhizobia is still complicated and need a lot of efforts to elucidate it.

During the last decade, DNA array technology was widely used to identify the differentially expressed genes of bacteria cultured under different condition [11-13]. In recent years, the next generation sequencing technology RNA-Seq has been wildly used in transcriptome analysis in bacteria [14]. Therefore, this kind of sequencing technology has been used to find the functional elements of the genome, the differentially expressed genes under different conditions and the new noncoding RNAs [15-17]. The objectives of the present work were to investigate the transcriptional changes in rhizobia subjected to long-term exposure to high concentration of NaCl and to make a transcriptome analysis of Mesorhizobium alhagi CCNWXJ12-2 during late exponential growth at two different concentrations of NaCl (0 and 0.4 M) by using the next generation sequencing technology RNA-Seq. The results showed a series of genes differentially expressed during long-term salt stress, among which were genes encoding an outer membrane adhesion protein (YadA), a co-methyltransferase (MttB) and a formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase (Fhs). Gene knockout and comparative growth analysis indicated that yadA was involved in salt resistance directly but the other two genes were not.

Results and discussions

Experimental design and global overview of the RNA-Seq data

The genome of Mesorhizobium alhagi strain CCNWXJ12-2 has been reported in 2012 [1] and the growth curves of Mesorhizobium alhagi under different salt concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 M of NaCl) were measured (Additional file 1). The growth of Mesorhizobium alhagi under 0.5 M of NaCl was dramatically delayed while under 0.4 M was acceptable. So we chose 0.4 M of NaCl as the high-salt condition. According to the salt tolerance research of the other mesorhizobium type strains (most sensitive to 0.26 M NaCl), Mesorhizobium alhagi possessed a relatively high salt resistance [18]. To investigate the salt resistance mechanism of M. alhagi under long-term salt stress, we have decided that to conduct a global transcriptome analysis of the strain growing under salt-free and high-salt conditions (0.4 M NaCl) at late exponential phase. Total RNA was extracted from three independent biological replicates and then mixed together for RNA sequencing. A total of 5,942,210 and 5,987,420 reads were obtained from control and salt-treatment condition, respectively. After filtration, the low quality reads 5,640,246 clean reads of control and 5,627,881 of salt-treatment were retained. The average length of the reads was 100 bp. For each of the two samples >95% of all reads was mapped to the reference genome.

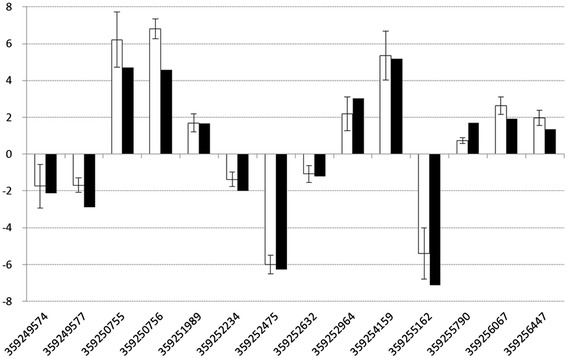

The RNA-Seq data were validated by analyzing 14 representative genes expression levels using RT-qPCR. The log2-transformed mean values for each gene of three biological replicates were in good agreement with the log2-transformed fold change of RNA-Seq (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Validation of RNA-Seq data using RT-qPCR. Fourteen representative genes were chosen to validate the RNA-Seq data by RT-qPCR. The white bars represent mean values of log2-transformed fold change obtained from three biological replicates of RT-qPCR with error bars stand for standard deviations. And the black bars represent RNA-Seq data.

Gene expression patterns under high-salt and salt-free conditions

RNA-Seq data showed that most of the predicted genes were expressed under both cultivating conditions. Among 7,407 predicted protein coding genes in the reference genome, there were 5,495 (74.19% of the total genes, RPKM > =20) and 5,459 (73.7% of the total genes, RPKM > =20) genes were detected in control and salt-treatment condition, respectively.

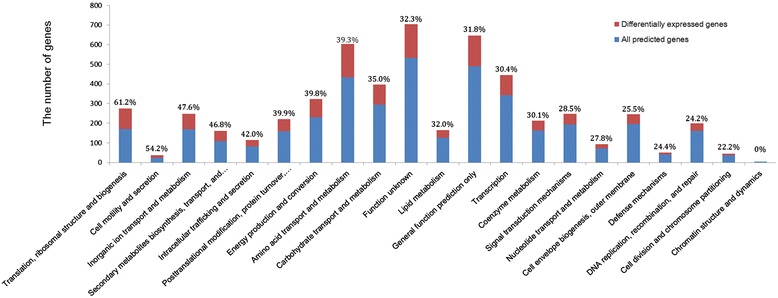

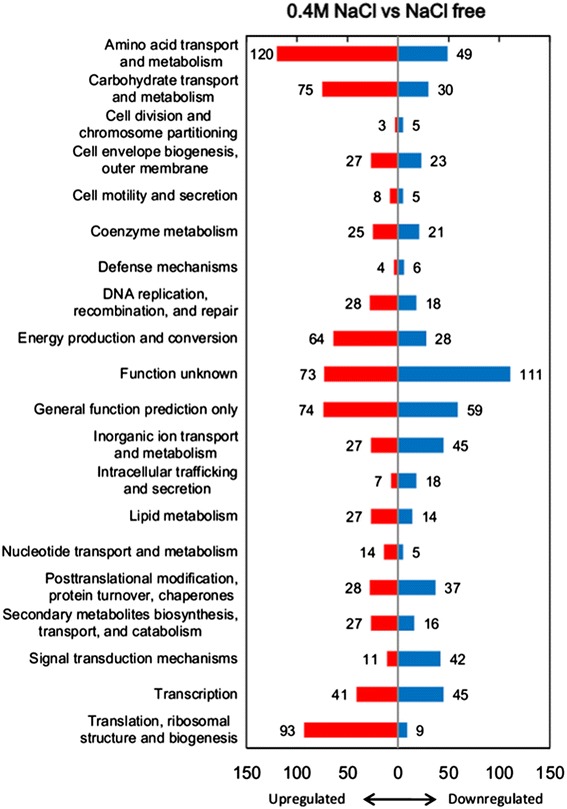

Cluster of orthologous groups (COG) is widely used to classify orthologous proteins [19]. Based on the conserved region, every protein is assumed to be evolved from an ancestor protein in COG database. Thus, this database is helpful to annotate the genes from poorly characterized genomes [20]. Aligned all of the predicted transcribed (RPKM > =20) genes against the COG database 4,022 genes obtained their COG codes. The Figure 2 presents the COG categories of all the proteins encoded by transcribed genes and the DEGs and the number of each category are shown in Additional file 2. The DEGs account for high ratios in most COG categories, which means the salt resistance mechanism in Mesorhizobium alhagi should be complex. Furthermore, among the total 1,849 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), 933 and 916 were significantly down-regulated and up-regulated response to salt stress, respectively. Consequently, this large number of DEGs suggested that not only the salt-specific stress responses but also the nonspecific responses were triggered. DEGs were then grouped by functional categories (Figure 3). Indeed, there are many genes involved in amino acid transport and metabolism, carbohydrate transport and metabolism, energy production and conversion and translation were induced by salt stress. The 184 genes of function unknown, 133 genes of general function predicted and 487 genes without COG codes indicated that Mesorhizobium alhagi XJ12-2 might have some unknown means to deal with the high salt condition.

Figure 2.

The COG categories of all predicted genes and the DEGs. Summary of COG annotations for all the predicted genes and the number of differentially expressed genes in each COG category. The percentage of the the DEGs account for the predicted genes were shown up the bars.

Figure 3.

The numbers of the DEGs grouped by functional categories. The red and blue bars represent up- and down-regulated genes, respectively, and the numeric lables represent the number of genes in the function.

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway database collects all known networks of molecular interactions in different species. The pathway analysis of the DEGs could be helping us to understand the interactions of these genes. With compared 7,407 predicted genes against the KEGG database using BBH method [21], a total of 2,568 putative proteins obtained their KO (KEGG Orthology) codes. The pathway enrichment analysis was conducted to make better understanding of how the Mesorhizobium alhagi adpat to salt stress. The threshold of FDR (false discovery rate) was setted to 0.001. The resutls showed that pathway enrichment of the downregulated genes was located in the KO term of Membrane Transport while the pathway enrichment of the upregulated genes was located in the KO terms of Transcription and Translation (Additional files 3 and 4). The results indicated that the protein synthesis enhanced during long-term salt stress.

DEGs involved in adaption to salt stress

Challenged with reduction in external water activity, the bacteria could be accumulating osmoprotectants to alleviate the inhibitory effects caused by high osmolarity [22]. The osmoprotectants include many macromolecules such as glycine betaine (GB), proline, and some other structurally related zwitterionic molecules [23]. Our RNA-Seq data showed that the expression level of genes involved in GB/proline uptaking (proVWX) was induced significantly by salt stress at 0.4 M NaCl and the proX showed a 35.9-fold up-regulated (Table 1). In Rhodobacter sphaeroides f. sp. Denitrificans IL106, trehalose is also another important osmoprotectant play an important role in salt resistance [24]. Our data showed that the gene expression level of trehalose synthase (treT) was repressed by high salt while the gene expression level of other two trehalose 6-phosphate synthases (otsA) were upregulated slightly (Table 1). The expression level of the Na+/H+ ions antiporter gene nhaA was also upregulated (Table 1). Na+/H+ ions antiporters play an important role in keeping ion homeostasis in many organisms [25]. In case of E. coli, nhaA made a great contribution to maintaining intracellular pH and Na+ homeostasis [26]. Whereas, in Vibrio cholera, nhaA was required for the bacteria to survive in a saline environment [27]. Some reports investigated the expression of exogenous nhaA in yeast and rice enhanced their salt tolerance [28,29]. Our results showed that most of the genes proven to be related to salt resistance in other organisms were also upregulated in M. alhagi growing under high salt condition (Table 1). Based on this point, we considered that the uptaking of osmoprotectant and the high expression of ion transporter genes were important means to cope with high salinity in M. alhagi.

Table 1.

DEGs involved in salt resistance

| GI number a | Log2(Fold_change) normalized | P-value | Gene | Gene discreption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 359254159 | 5.168 | 0 | proX | glycine betaine transporter periplasmic subunit |

| 359254161 | 3.539 | 1.22E-286 | proV | glycine betaine/L-proline ABC transporter ATPase subunit |

| 359254160 | 1.672 | 5.93E-16 | proW | glycine betaine/L-proline transport system permease protein |

| 359254492 | 1.665 | 7.04E-170 | proX | choline ABC transporter periplasmic protein |

| 359256447 | 1.361 | 5.51E-39 | nhaA | Na+/H+ antiporter NhaA |

| 359254494 | 1.455 | 8.30E-23 | proV | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein |

| 359254493 | 1.341 | 1.24E-11 | proW | glycine/betaine/proline ABC transporter membrane protein |

| 359251246 | −1.485 | 7.30E-64 | treT | trehalose synthase |

| 359256049 | 0.379 | 0.000108 | otsA | trehalose 6-phosphate synthase |

| 359248822 | 0.371 | 0.133699 | otsA | trehalose 6-phosphate synthase |

aGI number, GenInfo Identifier.

DEGs of other processes

Our results showed that many genes involved in cell growth, protein synthesis and energy production were upregulated under high salt condition (Additional file 5). The upregulation of these genes might suggest that the cell density of M. alhagi was higher under high salt conditions (0.4 M NaCl) at late exponential phase than that under no salt conditions (0 M NaCl). In recent years, there are some reports showed the expression of genes involved in cell growth, protein synthesis and energy production were upregulated in some microorganisms growing under high salt conditions[30,31]. In Staphylococcus sp. OJ82, isolated from high salt resistance fermented seafood, the expression level of genes involved in energy production, translation and cell membranes synthsis was induced by salt stress [30]. The expression level of fabG, a gene involved in biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids was highly upregulated by salt stress in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 [31]. Our RNA-Seq data, fabG, F, I, H and D, genes involved in unsaturated fatty acids biosynthesis, were all upregulated significantly except for fabB. According to our results we suggested that the bacteria needed to produce more energy and functional proteins to cope with the unsatisfied environmental conditions and the upregulation of these genes may also explain that the biomass of M. alhagi growing under high salt conditions was more than that growing in TY without NaCl (Additional file 5).

Besides that the genes were involved in cell growth, we still found a significant change in protein secretion systems (Additional file 6). There are two type III secretion systems (T3SSs) operons in M. alhagi CCNWXJ12-2, designated T3SS1 (359250064–359250082) and T3SS2 (359251150–359251163). So, our results showed that the expression level of T3SS1 increased under high salt conditions while T3SS2 was decreased (Additional file 6). In some bacteria, the expression levels of the T3SS genes were affected by salt. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, T3SS was upregulated at steady-state osmotic stress while it was downregulated during osmotic up-shock [32]. In Yersinia enterocolitica Biovar 1B, the Ysa T3SS was expressed when the concentration of NaCl in medium was greater than 180 mM and reached to the maximal level when the concentration of NaCl reached 290 mM [33]. In some rhizobium, the T3SS was involved in the interactions between the bacteria and the legumes plant to form the nodules [34-36]. We also found that the type VI secretion system (T6SS) and type IV secretion system (T4SS) were downregulated in the presence of 0.4 M NaCl (Additional file 6). Noteworthy, T6SS was not only involved in pathogenicity in some pathogens but also involved in keeping intracellular balance of H+ ions in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis [37-39]. Whereas, recent research papers showed that the T6SS was also involved in interbacterial interactions and competition between different bacteria genera [40,41]. In Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii, the T6SS was involved in the interaction between bacteria and legumes after the rhizobia inoculated to the plants [42,43]. In many bacteria T4SSs were involved in conjugal transfer of DNA [44]. However, in Mesorhizobium loti strain R7A, T4SS functioned as T3SSs of other rhizobium and had a role in symbiosis [45]. But in contrast to M. loti, T4SS in Sinorhizobium meliloti strain 1021 had no function in host invasion and symbiotic formation [46]. Besides the protein secretion systems, we still found two lytic transglycosylases (LTs,359253896 and 359252475) downregulated under salt stress (Additional file 6). LTs are a family of enzymes that could cleave glycosydic bonds within peptidoglycan sacculus to make space for some processes occurred within the cell envelope or assembly and anchoring of secretion systems [47,48]. The LTs also had functions in cell division and the downregulation of these enzymes might be explain the delay of the cell growing under high salt conditions and consist with the downregulation of the protein secretion systems [48]. Up to a point, the changes of the expression levels of the T3SSs, T6SS, T4SS and LTs genes under high salt condition we hypothesized that the environmental factor of high salt might be have influences on the communication between M. alhagi CCNWXJ12-2 and plants or other bacteria.

The RNA-Seq data showed that the molecular chaperones GroES, GroEL, DnaK, DnaJ and ClpB were all downregulated (Table 2). The risk of proteins unfolding was increased when organisms cultured under environmental stresses and these molecular chaperones could be help the proteins fold properly and reliably [49]. In this regard, it was very interesting of the downregulation of these genes under high salt conditons. In previous research, the heat shock proteins from E. coli and B. subtilis, DnaK or GroEL were not induced by supplement of salt in the medium [50-52]. But researchers also found that DnaK was involved in K+ ions transport at high osmolarity in E. coli [53]. In Rhizobium tropici DIAT899 the DnaJ insertion mutant was showed sensitivity to salt stress [54]. ClpB is a common molecular chaperone which could interact with DnaK and catalyze the proteins disaggregation and reactivation [55]. Transcriptome analysis of Staphylococcus sp. OJ82 growing under high salt condition showed that the expression of some molecular chaperones were downregulated, too [30]. We are confused why the expression of the molecular chaperones was downregulated when M. alhagi grown under high salt conditions. Therefore, the functions of these molecular chaperones in M. alhagi should be studied to explain this phenomenon. Because the transcriptome analysis just reflected the changes of mRNA level, so we suggested that the proteins levels of these genes should be investigated.

Table 2.

DEGs of molecular chaperones

| GI number | log2(Fold_change) normalized | P-value | Gene | Gene function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 359252555 | −1.006 | 7.17E-34 | groEL | chaperonin GroEL |

| 359252235 | −2.494 | 2.68E-103 | co-chaperonin GroES | |

| 359255864 | −1.155 | 7.59E-134 | dnaK | molecular chaperone DnaK |

| 359250220 | −1.989 | 3.11E-118 | heat shock protein DnaJ domain-containing protein | |

| 359254957 | −2.742 | 0 | ATP-dependent chaperone ClpB |

Characterization of gene knockout and complementation mutants

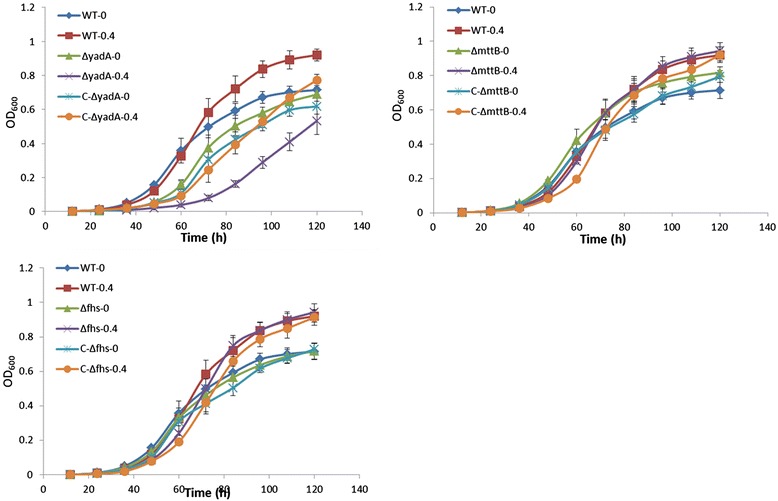

To identify the involvement in salt response, three genes highly induced by salt stress (yadA, mttB and fhs) were selected for gene mutant construction since so far no reports show that they are involved in salt resistance. The expression data of the three genes were listed in Table 3. In order to study of yadA (Yersinia adhesin A), researchers focus on the importance of the gene function on the pathogenicity of Yersinia and this gene was found to be a major virulence factor of Yersinia enterocolitica [56-58]. YadA is a trimeric autotransporter produced by Yersinia enterocolitica and it has manifold functions such as helping bacteria adhesion to host cells, promoting autoaggregation and protection of the bacteria from complement-mediated killing [59]. Gene mttB was encoding a co-methyltransferase which involved in the methane metabolism in Methanosarcina and its function in Mesorhizobium is still unknown [60,61]. Gene fhs was encoding a formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase involved in the biosynthesis of purine, Met-tRNA, methionine, serine and some other amino acids in Streptococcus sp [62]. The upregulation of the fhs consisted with the upregulation of genes involved in protein synthesis. The growth curves of the mutants in TY broth medium under salt stress showed that the growth rate of mutant ΔyadA was delayed under high salt condition while the growth of the other two mutants were almost the same with the wild type (Figure 4). The growth curve of ΔyadA complementation mutant showed a restored salt tolerance, although it cannot reach the wild type level (Figure 4). This may be caused by the activity of the plasmid promoter was not strong in Mesorhizobium alhagi. In Figure 4, the delay of the growth under high salt condition was caused by the different culture conditions. Thus, we considered that gene yadA was involved in salt resistance while the other two genes were not.

Table 3.

Gene expression of genes yadA , mttB and fhs

| Gene | log2(Fold_change) normalized | P-value | Gene function |

|---|---|---|---|

| yadA | 4.567258 | 0 | YadA domain-containing protein |

| mttB | 3.771452 | 2.38E-213 | Trimethylamine methyltransferase |

| fhs | 3.758628 | 0 | Formate--tetrahydrofolate ligase |

Figure 4.

Growth curves of the wild type and mutants. Optical density at 600 nm(OD600) was used to monitor the bacteria growth. Three independent biological experiments were conducted to measure the growth of the wild type M. alhagi and the mutants. The error bars stand for standard deviations. A yadA mutant and the complementation mutant; B mttB mutant and the complementation mutant; C fhs mutant and the complementation mutant.

Conclusion

In our study, we have used RNA-Seq to obtain the transcriptome profiles of M. alhagi CCNWXJ12-2 growing under high salt and salt-free conditions and compared them to try to elucidate the mechanism of salt resistance. Our results showed that the expression of many validated genes involved in salt resistance in other bacteria was also induced by high salt in M. alhagi, such as proV, proW, proX and nhaA. Moreover, there are many genes involved in cell growth, energy production and translation were also upregulated by salt stress. Based on our results, we consider that the osmoprotectants uptaking and the ion transporters are the two important ways to cope with the salt stress in M. alhagi. The enhanced energy production and protein synthesis as well as the decreased protein secretion systems and other unimportant processes could also improve the ability of the bacteria to survive under high salt condition. To our knowledge, this is the first report about transcriptome analysis of a rhizobia using RNA-Seq to elucidate the salt resistance mechanism and we believe that our results could be consider as a reference work for the further salt resistance researches.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Mesorhizobium alhagi CCNWXJ12-2 was used for all the experiments. The genome of this strain was sequenced and published in 2012 [1]. Single colonies were selected and checked for purity by repeated streaking and microscopic examination. All isolates were incubated at 28°C and maintained on TY agar plate (5 g tryptone, 3 g yeast extract, and 0.7 g CaCl2 · 2H2O per liter). Strain CCNWXJ12-2 was pre-cultured in 10 ml TY broth medium. The cultures were incubated at 28°C and agitated at 180 rpm for 3 days. The growth values of the strains were determined by absorbance at 600 nm (OD600). One milliliter of the CCNWXJ12-2 suspension was pre-cultured into 100 ml TY broth medium supplemented with 0.4 M NaCl also at the same time a control experiment was conducted. At the end of the exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 1.5 for control group and 2.0 for stressed group), cells were harvested in order to isolate RNA.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted by following protocol of Rivas and Vizcaino [63]. Three independent biological repeats were conducted for each treatment and the extracted RNA samples were mixed together for each treatment. Total RNA was treated with RNase-free DNaseI according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Ambion, USA) and incubated in 37°C for 1 hour. The purified RNA was checked by amplifying 16 s rDNA using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (35 cycles). Then, rRNA was removed using Ribo-ZeroTM rRNA Removal Kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Epicentre, USA). The quantity and purity of the purified RNA was assessed using NanoDrop ND-1000 and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. The A260/A280 ratio of the two samples was ≥2.0.

To generate a cDNA library, the total RNA removed 16S and 23S rRNA was fragmented into small pieces at a specific temperature and then the random premier with biotin and illumina primer (Oligonucleotide sequences © 2006–2010 Illumina, Inc) was used to anneal with the fragmented mRNA. The first strand of cDNA was then synthesized using reverse transcriptase. Finally, the double strand cDNA was synthesized by PCR with illumina primer.

Illumina sequencing and data analysis

The cDNA between 300 and 500 bp was obtained by gel extraction. The extracted cDNA was amplified using TruSeq PE Cluster Kit (Illumina,USA) and then sequenced on Illumina Hiseq2000 to generate 100-bp single-end reads.

The clean reads were got by removing the low quality sequences and then mapped to the reference genome using short oligonucleotide alignment program (SOAP) [64]. RPKM (number of reads per kilobase of exon region per million mapped reads) was used to normalize the expression level of genes [65]. The difference of gene expression between two samples were counted using MA-plot-based method with Random sampling model (MARS) in DEGseq software package [66]. The differentially expressed genes were considered to be induced or repressed if the normalized fold change (log2(fold change)) >1 and the false discovery rate (FDR) <0.001[67].

Reverse Position Specific BLAST (RPS-BLAST) program was used to obtain the COG items (clusters of orthologous groups) of the genes [19]. The KO (KEGG Orthology) codes of genes were obtained using bidirectional best hit method (BBH) aligned with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database (KEGG) [21]. The pathway enrichment analysis was conducted using hypergeometric distribution method. The results of the RNA sequencing experiments have been submitted to GEO database with an accession number of GSE57306.

Validation of RNA-Seq data by RT-qPCR

The expression levels of 14 representative genes were examined by RT-qPCR to validate the RNA-Seq data (Table 4). The primers for RT-qPCR were designed using Primer 3 (Additional file 7) [68]. These primers were pruned against the genome of M. alhagi to ensure their specificity. The sizes of PCR products were confirmed by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel. The RNA extraction was conducted the same as in RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis. Moreover, the cDNA synthesis was conducted using PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara Japan). Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted on BioRad CFX96 Real-Time System using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq (Takara Japan). For each gene/sample combination, three replicate reactions were carried out. In addition, the 16 s rDNA gene was chosen as a reference gene.

Table 4.

Genes used to validate the RNA-Seq data

| GI number | Expression state | Gene annotation |

|---|---|---|

| 359249574 | DOWN | ClpA/B-type protease |

| 359249577 | DOWN | type VI secretion protein, evpb/vc_a0108 family |

| 359250755 | UP | hypothetical protein MAXJ12_26333 |

| 359250756 | UP | YadA domain-containing protein |

| 359251989 | UP | Na+/solute symporter (Ssf family) protein |

| 359252234 | DOWN | chaperonin GroEL |

| 359252475 | DOWN | lytic transglycosylase |

| 359252632 | DOWN | PrkA family serine protein kinase |

| 359252964 | UP | AraC type helix-turn-helix- domain containing protein |

| 359254159 | UP | glycine betaine transporter periplasmic subunit |

| 359255162 | DOWN | hypothetical protein MAXJ12_06665 |

| 359255790 | UP | NodF |

| 359256067 | UP | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase |

| 359256447 | UP | Na+/H+ antiporter NhaA |

Gene knockout mutant construction and complementation tests

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in gene knockout mutant construction and complementation tests are listed in (Additional file 8). Primers used in this part are listed in (Additional file 9). For gene knockout construction, we firstly designed four primers to amplify the upward and downward fragments of each target gene. Secondly, we digested the fragments and pk18mobsacB plasmid with proper restriction enzymes using standard protocols. Thirdly, we conducted that the prepared plasmids and fragments ligation reaction using T4 ligase and transformed the ligation products into Escherichia coli DH5α component cells. Finally, triparental mating procedure was conducted to transforme the plasmids from E. coli to M. alhagi as described previously [69]. Briefly, the DH5α strains containing the plasmids constructed, the MM249 strains containing helper plasmid pRK2013 and wild type M. alhagi mixed together and cultured on TY plate for three days. Then, SM plates containing kanamycin (50 ug/ml) were used to isolate the single exchange of M. alhagi mutants. The TY plates containing sucrose (5 g/100 ml) were used to isolate the double exchange mutants. The obtained geneknock mutants were verified by PCR. For complementation mutant strain construction, we designed primers to amplify the entire open reading frame of each gene. The folloing producers were similar to the gene knockout mutant construction. The difference of the complementation mutant construction was that the plasmid used was pBBR1MCS-5 and the antibiotic uesd was gentamicin. The strains containing the complementation plasmids were selected on SM plates containing gentamicin (50 ug/ml) and validated by colony PCR.

Growth analysis under salt stress

Wild type of M. alhagi and the gene knockout mutants were cultured to OD ≈ 0.5 in TY broth medium. 5 ul suspensions of the fourstrains was inoculated into 24 well culture plate (Cyagen Biosciences Inc. USA) containing 1 ml TY broth medium with and without 0.4 M NaCl. For the complementation tests, the TY borth medium with and without 0.4 M NaCl containing gentamicin (50 ug/ml) was used to obtain the growth curve. The OD600 of the plates were detected every 12 hours using Epoch (Bioteck, USA). For measuring the growth curves of M. alhagi under different salt concentrations, the inoculum was cultured to OD ≈ 0.1 and then 1 ml of the inoculum was inoculated into 100 ml TY broth medium with different salt concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4 and 0.5 M NaCl). The flasks were incubated in a shaker at 28°C and agitated at 120 rpm. The OD600 of the cultures were detected every 12 hours using Lambda 35 UV/VIS Spectrometer (PerkinElmer, USA).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by projects from the 863 project of China (2012AA100402) and the National Science Foundation of China (31125007 and 31370142).

Additional file

Growth curve of XJ12-2 in TY medium under different salt stress. Optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was used to monitor the bacteria growth. The mean values of three independent experiments are shown and the error bars represent the standard deviation. The arrows point out the sample collection time.

The number of genes in each COG categories.

Overrepresented functional KO terms of down-regulated genes.

Overrepresented functional KO terms of up-regulated genes.

Representative DEGs involved in cell growth, protein synthesis and energy production.

DEGs involved in protein secretion systems and lytic transglycosylases.

Primers used in RT-qPCR.

Bacteria strains and plasmids used in this study.

Primers used in mutant construction.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

XL, YL and GH make conception and design of the study. XL, YL and DL conduct the laboratory work. XL and OAM carry out the data analysis and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xiaodong Liu, Email: lxd19861216@126.com.

Yantao Luo, Email: yantao.luo@163.com.

Osama Abdalla Mohamed, Email: dr.osamaabusaud@hotmail.com.

Dongying Liu, Email: louise-wintermelon@163.com.

Gehong Wei, Email: weigehong@nwsuaf.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Zhou ML, Chen WM, Chen HY, Wei GH. Draft Genome Sequence of Mesorhizobium alhagi CCNWXJ12-2(Tau), a Novel Salt-Resistant Species Isolated from the Desert of Northwestern China. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(5):1261–1262. doi: 10.1128/JB.06635-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng FJ, Zhang XM, Foetzki A, Li XY, Li XM, Runge M. Water relation characteristics of Alhagi sparsifolia and consequences for a sustainable management. Sci China Ser D. 2002;45:125–131. doi: 10.1007/BF02878398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vriezen JAC, de Bruijn FJ, Nusslein K. Responses of rhizobia to desiccation in relation to osmotic stress, oxygen, and temperature. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(11):3451–3459. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02991-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zahran HH: Rhizobium-legume symbiosis and nitrogen fixation under severe conditions and in an arid climate.Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 1999, 63(4):968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Kulkarni S, Surange S, Nautiyal CS. Crossing the limits of Rhizobium existence in extreme conditions. Curr Microbiol. 2000;41(6):402–409. doi: 10.1007/s002840010158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen W, Lee T, Lan C, Cheng C. Characterization of halotolerant rhizobia isolated from root nodules of Canavalia rosea from seaside areas. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2000;34(1):9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2000.tb00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan AM, Wang ET, Kan FL, Tan ZY, Sui XH, Reinhold-Hurek B, Chen WX. Sinorhizobium meliloti associated with Medicago sativa and Melilotus spp. in arid saline soils in Xinjiang, China. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:1887–1891. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-5-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen WM, Zhu WF, Bontemps C, Young JPW, Wei GH. Mesorhizobium alhagi sp nov., isolated from wild Alhagi sparsifolia in north-western China. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:958–962. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.014043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller-Williams M, Loewen PC, Oresnik IJ. Isolation of salt-sensitive mutants of Sinorhizobium meliloti strain Rm1021. Microbiology-Sgm. 2006;152:2049–2059. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28937-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang JQ, Wei W, Du BH, Li XH, Wang L, Yang SS. Salt-tolerance genes involved in cation efflux and osmoregulation of Sinorhizobium fredii RT19 detected by isolation and characterization of Tn5 mutants. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;239(1):139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber A, Jung K. Profiling early osmostress-dependent gene expression in Escherichia coli using DNA macroarrays. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(19):5502–5507. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.19.5502-5507.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunasekera TS, Csonka LN, Paliy O. Genome-wide transcriptional responses of Escherichia coli k-12 to continuous osmotic and heat stresses. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(10):3712–3720. doi: 10.1128/JB.01990-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.den Besten HM, Mols M, Moezelaar R, Zwietering MH, Abee T. Phenotypic and transcriptomic analyses of mildly and severely salt-stressed Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579 cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(12):4111–4119. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02891-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Vliet AHM. Next generation sequencing of microbial transcriptomes: challenges and opportunities. Fems Microbiol Lett. 2010;302(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma CM, Hoffmann S, Darfeuille F, Reignier J, Findeiss S, Sittka A, Chabas S, Reiche K, Hackermuller J, Reinhardt R, Stadler PF, Vogel J. The primary transcriptome of the major human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 2010;464(7286):250–255. doi: 10.1038/nature08756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnvig KB, Comas I, Thomson NR, Houghton J, Boshoff HI, Croucher NJ, Rose G, Perkins TT, Parkhill J, Dougan G, Young DB: Sequence-Based Analysis Uncovers an Abundance of Non-Coding RNA in the Total Transcriptome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.PloS Pathogens 2011, 7(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Yuan TZ, Ren Y, Meng K, Feng Y, Yang PL, Wang SJ, Shi PJ, Wang L, Xie DX, Yao B. RNA-Seq of the xylose-fermenting yeast Scheffersomyces stipitis cultivated in glucose or xylose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;92(6):1237–1249. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3607-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laranjo M, Oliveira S. Tolerance of Mesorhizobium type strains to different environmental stresses. Anton Leeuw Int J G. 2011;99(3):651–662. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9539-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchler-Bauer A, Panchenko AR, Shoemaker BA, Thiessen PA, Geer LY, Bryant SH. CDD: a database of conserved domain alignments with links to domain three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):281–283. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278(5338):631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Hirakawa M. KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D355–D360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood JM, Bremer E, Csonka LN, Kraemer R, Poolman B, van der Heide T, Smith LT. Osmosensing and osmoregulatory compatible solute accumulation by bacteria. Comp Biochem Physioly Mol Integr Physiol. 2001;130(3):437–460. doi: 10.1016/S1095-6433(01)00442-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neidhardt FC (1987) Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Am Soc Microbiol

- 24.Xu X, Abo M, Okubo A, Yamazaki S (1998) Trehalose as osmoprotectant in Rhodobacter sphaeroides f. sp. denitrificans IL106. Vol. 62 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Padan E, Venturi M, Gerchman Y, Dover N. Na(+)/H(+) Antiporters. Bba-Bioenerg. 2001;1505(1):144–157. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00284-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volkmar KM, Hu Y, Steppuhn H. Physiological responses of plants to salinity: A review. Can J Plant Sci. 1998;78(1):19–27. doi: 10.4141/P97-020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herz K, Vimont S, Padan E, Berche P. Roles of NhaA, NhaB, and NhaD Na+/H+ antiporters in survival of Vibrio cholerae in a saline environment. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(4):1236–1244. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.4.1236-1244.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ros R, Montesinos C, Rimon A, Padan E, Serrano R. Altered Na + and Li + homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells expressing the bacterial cation antiporter NhaA. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(12):3131–3136. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3131-3136.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu LQ, Fan ZM, Guo L, Li YQ, Chen ZL, Qu LJ. Over-expression of the bacterial nhaA gene in rice enhances salt and drought tolerance. Plant Sci. 2005;168(2):297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.05.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi S, Jung J, Jeon CO, Park W. Comparative genomic and transcriptomic analyses of NaCl-tolerant Staphylococcus sp OJ82 isolated from fermented seafood. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(2):807–822. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5436-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiao JJ, Huang SQ, Te RG, Wang JX, Chen L, Zhang WW. Integrated proteomic and transcriptomic analysis reveals novel genes and regulatory mechanisms involved in salt stress responses in Synechocystis sp PCC 6803. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(18):8253–8264. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aspedon A, Palmer K, Whiteley M. Microarray analysis of the osmotic stress response in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(7):2721–2725. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2721-2725.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venecia K, Young GM. Environmental regulation and virulence attributes of the Ysa type III secretion system of Yersinia enterocolitica biovar 1B. Infect Immun. 2005;73(9):5961–5977. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5961-5977.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dai WJ, Zeng Y, Xie ZP, Staehelin C. Symbiosis-promoting and deleterious effects of NopT, a novel type 3 effector of Rhizobium sp strain NGR234. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(14):5101–5110. doi: 10.1128/JB.00306-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okazaki S, Okabe S, Higashi M, Shimoda Y, Sato S, Tabata S, Hashiguchi M, Akashi R, Gottfert M, Saeki K. Identification and Functional Analysis of Type III Effector Proteins in Mesorhizobium loti. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2010;23(2):223–234. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-2-0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okazaki S, Kaneko T, Sato S, Saeki K. Hijacking of leguminous nodulation signaling by the rhizobial type III secretion system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(42):17131–17136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302360110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang WP, Wang Y, Song YH, Wang TT, Xu SJ, Peng Z, Lin XL, Zhang L, Shen XH. A type VI secretion system regulated by OmpR in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis functions to maintain intracellular pH homeostasis. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15(2):557–569. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burtnick MN, Brett PJ, Harding SV, Ngugi SA, Ribot WJ, Chantratita N, Scorpio A, Milne TS, Dean RE, Fritz DL, Peacock SJ, Prior JL, Atkins TP, DeShazer D. The Cluster 1 Type VI Secretion System Is a Major Virulence Determinant in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect Immun. 2011;79(4):1512–1525. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01218-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suarez G, Sierra JC, Sha J, Wang S, Erova TE, Fadl AA, Foltz SM, Horneman AJ, Chopra AK. Molecular characterization of a functional type VI secretion system from a clinical isolate of Aeromonas hydrophila. Microb Pathog. 2008;44(4):344–361. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basler M, Ho BT, Mekalanos JJ. Tit-for-Tat: Type VI Secretion System Counterattack during Bacterial Cell-Cell Interactions. Cell. 2013;152(4):884–894. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basler M, Mekalanos JJ: Type 6 Secretion Dynamics Within and Between Bacterial Cells.Science 2012, 337(6096):815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Roest HP, Mulders IH, Spaink HP, Wijffelman CA, Lugtenberg BJ. A Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii locus not localized on the sym plasmid hinders effective nodulation on plants of the pea cross-inoculation group. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact : MPMI. 1997;10(7):938–941. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.7.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bladergroen MR, Badelt K, Spaink HP. Infection-blocking genes of a symbiotic Rhizobium leguminosarum strain that are involved in temperature-dependent protein secretion. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact: MPMI. 2003;16(1):53–64. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christie PJ. Type IV secretion: the Agrobacterium VirB/D4 and related conjugation systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1694(1–3):219–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hubber A, Vergunst AC, Sullivan JT, Hooykaas PJJ, Ronson CW. Symbiotic phenotypes and translocated effector proteins of the Mesorhizobium loti strain R7A VirB/D4 type IV secretion system. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54(2):561–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones KM, Lloret J, Daniele JR, Walker GC. The type IV secretion system of Sinorhizobium meliloti strain 1021 is required for conjugation but not for intracellular symbiosis. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(5):2133–2138. doi: 10.1128/JB.00116-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koraimann G. Lytic transglycosylases in macromolecular transport systems of Gram-negative bacteria. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60(11):2371–2388. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3056-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheurwater E, Reid CW, Clarke AJ. Lytic transglycosylases: Bacterial space-making autolysins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(4):586–591. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brigido C, Alexandre A, Oliveira S. Transcriptional analysis of major chaperone genes in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive mesorhizobia. Microbiol Res. 2012;167(10):623–629. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hecker M, Völker U. General stress proteins in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;74(2–3):197–213. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hecker M, Heim C, Volker U, Wolfel L. Induction of stress proteins by sodium chloride treatment in Bacillus subtilis. Arch Microbiol. 1988;150(6):564–566. doi: 10.1007/BF00408250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark D, Parker J. Proteins induced by high osmotic pressure in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1984;25(1):81–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1984.tb01380.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meury J, Kohiyama M. Role of heat shock protein DnaK in osmotic adaptation of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173(14):4404–4410. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4404-4410.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nogales J, Campos R, BenAbdelkhalek H, Olivares J, Lluch C, Sanjuan J. Rhizobium tropici genes involved in free-living salt tolerance are required for the establishment of efficient nitrogen-fixing symbiosis with Phaseolus vulgaris. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact : MPMI. 2002;15(3):225–232. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Motohashi K, Watanabe Y, Yohda M, Yoshida M. Heat-inactivated proteins are rescued by the DnaK.J-GrpE set and ClpB chaperones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(13):7184–7189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karataev GI, Markov AR, Sinyashina LN, Miller GG, Klitsunova NV, Titova IV, Semin EG, Goncharova NI, Pokrovskaya MS, Amelina IP, Amoako K, Smirnov GB. Comparative investigation of the role of the YadA, InvA, and PsaA genes in the pathogenicity of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Mol Genet Microbiol Virol. 2008;23(4):168–177. doi: 10.3103/S0891416808040034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schindler MKH, Schutz MS, Muhlenkamp MC, Rooijakkers SHM, Hallstrom T, Zipfel PF, Autenrieth IB. Yersinia enterocolitica YadA Mediates Complement Evasion by Recruitment and Inactivation of C3 Products. J Immunol. 2012;189(10):4900–4908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schutz M, Weiss EM, Schindler M, Hallstrom T, Zipfel PF, Linke D, Autenrieth IB. Trimer Stability of YadA Is Critical for Virulence of Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect Immun. 2010;78(6):2677–2690. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01350-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.El Tahir Y, Skurnik M. YadA, the multifaceted Yersinia adhesin. Int J Med Microbiol. 2001;291(3):209–218. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kratzer C, Carini P, Hovey R, Deppenmeier U. Transcriptional Profiling of Methyltransferase Genes during Growth of Methanosarcina mazei on Trimethylamine. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(16):5108–5115. doi: 10.1128/JB.00420-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paul L, Ferguson DJ, Krzycki JA. The trimethylamine methyltransferase gene and multiple dimethylamine methyltransferase genes of Methanosarcina barkeri contain in-frame and read-through amber codons. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(9):2520–2529. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.9.2520-2529.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crowley PJ, Gutierrez JA, Hillman JD, Bleiweis AS. Genetic and physiologic analysis of a formyl-tetrahydrofolate synthetase mutant of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 1997;179(5):1563–1572. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1563-1572.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rivas R, Vizcaino N, Buey RM, Mateos PF, Martinez-Molina E, Velazquez E. An effective, rapid and simple method for total RNA extraction from bacteria and yeast. J Microbiol Methods. 2001;47(1):59–63. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(01)00292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li RQ, Li YR, Kristiansen K, Wang J. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(5):713–714. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, Mccue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5(7):621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang LK, Feng ZX, Wang X, Wang XW, Zhang XG. DEGseq: an R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):136–138. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dhooghe I, Michiels J, Vlassak K, Verreth C, Waelkens F, Vanderleyden J. Structural and Functional-Analysis of the Fixlj Genes of Rhizobium-Leguminosarum Biovar Phaseoli Cnpaf512. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;249(1):117–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00290243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]