Abstract

Background

During wheat senescence, leaf components are degraded in a coordinated manner, releasing amino acids and micronutrients which are subsequently transported to the developing grain. We have previously shown that the simultaneous downregulation of Grain Protein Content (GPC) transcription factors, GPC1 and GPC2, greatly delays senescence and disrupts nutrient remobilization, and therefore provide a valuable entry point to identify genes involved in micronutrient transport to the wheat grain.

Results

We generated loss-of-function mutations for GPC1 and GPC2 in tetraploid wheat and showed in field trials that gpc1 mutants exhibit significant delays in senescence and reductions in grain Zn and Fe content, but that mutations in GPC2 had no significant effect on these traits. An RNA-seq study of these mutants at different time points showed a larger proportion of senescence-regulated genes among the GPC1 (64%) than among the GPC2 (37%) regulated genes. Combined, the two GPC genes regulate a subset (21.2%) of the senescence-regulated genes, 76.1% of which are upregulated at 12 days after anthesis, before the appearance of any visible signs of senescence. Taken together, these results demonstrate that GPC1 is a key regulator of nutrient remobilization which acts predominantly during the early stages of senescence. Genes upregulated at this stage include transporters from the ZIP and YSL gene families, which facilitate Zn and Fe export from the cytoplasm to the phloem, and genes involved in the biosynthesis of chelators that facilitate the phloem-based transport of these nutrients to the grains.

Conclusions

This study provides an overview of the transport mechanisms activated in the wheat flag leaf during monocarpic senescence. It also identifies promising targets to improve nutrient remobilization to the wheat grain, which can help mitigate Zn and Fe deficiencies that afflict many regions of the developing world.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12870-014-0368-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Wheat, Senescence, GPC, Zinc transport, Iron transport, ZIP

Background

In annual grasses, monocarpic senescence is the final stage of a plant’s development during which vegetative tissues are degraded and their cellular nutrients and amino acids are transported to the developing grain. The regulation of this process is crucial for the plant’s reproductive success and determines to a large extent the nutritional quality of the harvested grain. Among wild diploid relatives of wheat, there exists large variation in Zn and Fe grain content, whereas modern wheat germplasm collections exhibit comparatively lower and less variable Zn and Fe concentrations [1,2], demonstrating that improvements in these traits are possible. Zn and Fe deficiency afflict many parts of the developing world where wheat constitutes a major part of the diet, making the development of nutritionally-enhanced wheat varieties an important target for breeders tackling this problem [3].

The main source of protein and micronutrients in the wheat grain is the flag leaf and, to a lesser extent, the lower leaves [4,5]. When applied to the leaf tip, radioactively-labelled Zn is efficiently translocated to the developing wheat grain [6]. The close correlation between Zn and Fe content in the grain suggests some level of redundancy in the regulatory mechanisms used by the plant to transport these micronutrients [1]. However, the regulation of gene expression associated with nutrient transport from leaves to grain during wheat monocarpic senescence is poorly understood. A detailed understanding of these mechanisms will be required in order to engineer wheat varieties with improved nutritional quality through biofortification [7].

Several studies in other species, including barley, rice and Arabidopsis have revealed distinct mechanisms regulating micronutrient transport in vegetative tissues, which are described below according to their sub-cellular location.

Transport between chloroplast and cytoplasm

Because of its importance to photosynthesis, Fe is particularly abundant within the chloroplasts, which harbor ~90% of all Fe in the leaf during vegetative development [8]. Therefore, the remobilization of Fe from the chloroplast is an important process during monocarpic senescence. In Arabidopsis a member of the ferric chelate reductase (FRO) gene family is highly expressed in photosynthetic tissues and localizes to the chloroplast membrane, suggestive of a role in the reduction-based import of Fe into the chloroplasts [9]. In rice, certain FRO genes are preferentially expressed in the leaf vasculature rather than the roots, suggesting that this may be a conserved transport mechanism [10]. Certain members of the Heavy Metal ATPase (HMA) family of transporters have been implicated in the reverse process; nutrient export from the chloroplast to the cytoplasm. In Arabidopsis, AtHMA1 localizes to the chloroplast membrane and facilitates Zn export from the chloroplast [11] and in barley, HvHMA1 facilitates both Zn and Fe export from the chloroplast [12].

Transport between vacuole and cytoplasm

Additional mechanisms within the leaf exist to facilitate Fe and Zn transport between the vacuole and cytoplasm as part of a sequestration strategy, since high concentrations of either nutrient can be toxic for the plant cell. In rice, two VACUOLAR IRON TRANSPORTER genes, OsVIT1 and OsVIT2, encode proteins which are localized to the vacuolar membrane (tonoplast) and facilitate Zn2+ and Fe2+ import to the vacuole [13]. Likewise, the ZINC-INDUCED FACILITATOR-LIKE (ZIFL) genes encode Zn-transporters which are implicated in vacuole transport. In Arabidopsis, ZIF1 localizes to the tonoplast and zif1 mutants accumulate Zn in the cytosol, suggesting that these transporters promote vacuolar sequestration of Zn by facilitating its import into the vacuole [14]. However, several of the thirteen ZIFL genes recently described in rice are induced in the flag leaves during senescence [15]. This suggests that in monocots, certain ZIFL genes may also play a role in promoting nutrient remobilization during senescence. The NRAMP family of transporters appears to regulate nutrient export from the vacuole. In Arabidopsis, NRAMP3 and NRAMP4 are induced in Fe-deficient conditions and plants combining mutations in both these genes fail to mobilize vacuolar reserves of Fe [16].

Transport from cytoplasm to phloem

For their transport to the grain, micronutrients must be transported from the cytoplasm across the plasma membrane to be loaded into the phloem. This process is facilitated by members of the Yellow stripe like (YSL) and ZRT, IRT like protein (ZIP) families of membrane-bound transporters, which transport metal-chelate complexes across the plasma membrane in the leaves of several plant species [17-19]. In Arabidopsis, two Fe-transporting members of the YSL gene family were shown to be essential for normal seed development [20] and in barley, HvZIP7 knockout mutant plants exhibit significantly reduced Zn levels in the grain, suggesting that this family may also be important for nutrient loading into the phloem [21].

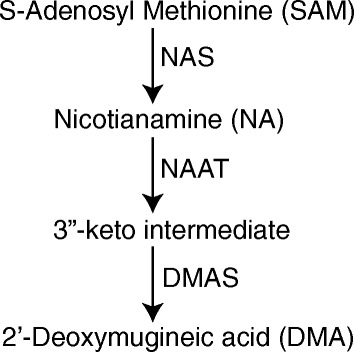

Because Zn and Fe ions exhibit limited solubility in the alkaline environment of the phloem, they are transported in association with a chelator [19]. Nicotianamine (NA) is one such important chelator and is a member of the mugineic acid family phytosiderophores [22]. NA biosynthesis is regulated by the enzyme nicotianamine synthase (NAS) by combining three molecules of S-Adenosyl Methionine [23], and can be further catalyzed to 2’-deoxymugineic acid (DMA) by the sequential activity of nicotianamine aminotransferase (NAAT) [24,25], which generates a 3”-keto intermediate and DMA synthase (DMAS, Figure 1) [26]. Although Zn has been shown to associate with DMA in the rice phloem [27], a recent study suggests that it is more commonly associated with NA [28]. In contrast, the principal chelator of Fe in the rice phloem is DMA [29]. It has been hypothesized that phloem transport represents the major limiting factor determining Zn and Fe content of cereal grains [30] and this is supported by several studies which demonstrate that altering NAS expression can have significant impacts on Zn and Fe grain and seed content. In Arabidopsis, plants carrying non-functional mutations in all NAS genes exhibit low Fe levels in sink tissues, while maintaining high levels in ageing leaves [31]. Conversely, NAS overexpression results in the accumulation of higher concentrations of Zn and Fe in Arabidopsis seed [32], rice grains [33,34] and barley grains [35].

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis of mugienic acid phytosiderophores. The combination of three molecules of SAM to form one molecule of NA is catalyzed by NAS. NA is converted to DMA through the action of NAAT to form a 3”-keto intermediate and then by DMAS to form DMA. Adapted from Bashir et al. [26].

Regulation of senescence and nutrient translocation

Monocarpic senescence and nutrient translocation to the grain occur simultaneously, requiring a precise coordination of these two processes. This is reflected in the large-scale transcriptional changes in the plant’s vegetative tissues during the onset of senescence, as documented in recent expression studies in Arabidopsis [36,37], barley [38] and wheat [39,40]. These studies consistently identify increased expression levels of a number of transcription factors of different classes. Particularly important roles have been identified for members of the NAC family [38,41-44]. In wheat, one such NAC-domain transcription factor, Grain Protein Content 1 (GPC1, also known as NAM1), has been shown to play a critical role in the regulation of both the rate of senescence and the levels of protein, Zn and Fe in the mature grain [44].

Originally identified as a QTL which enhances grain protein content in wild emmer (Triticum turgidum spp. dicoccoides) [45], the genomic region of chromosome arm 6BS including GPC1 was later shown to also accelerate senescence in tetraploid and hexaploid wheat [44,46,47]. A paralogous gene, GPC2 (also known as NAM2), was identified on chromosome arm 2BS, which shares 91% similarity with GPC1 at the DNA level [44]. Transcripts of GPC1 and GPC2 are first detected in flag leaves shortly before anthesis and increase rapidly during the early stages of senescence. In hexaploid wheat, plants transformed with a GPC-RNAi construct targeting all homologous GPC genes and plants carrying loss-of-function mutations in all GPC1 homoeologs, both exhibit a three-week delay in the onset of senescence as well as significant reductions in the transport of amino acids (N), Zn and Fe to the grain [5,44,46]. Therefore, GPC mutants represent an excellent tool to dissect the mechanisms underlying Zn and Fe transport from leaves to grains during monocarpic senescence.

In the current study, we used RNA-seq to identify genes differentially regulated in the flag leaves during three early stages of monocarpic senescence in tetraploid wheat. We also identified genes that were differentially expressed within each of these stages between tetraploid WT and gpc mutants, which exhibited reduced Zn and Fe grain concentrations. We identified members of different transporter families, which were differentially regulated both during the early stages of senescence and between genotypes with different GPC alleles. Results from this study define more precisely the role of individual GPC genes in the regulation of transporter gene families in senescing leaves and identify new differentially regulated targets for Fe and Zn biofortification strategies in wheat.

Results

GPC1 and GPC2 mutations and their effect on senescence and nutrient translocation

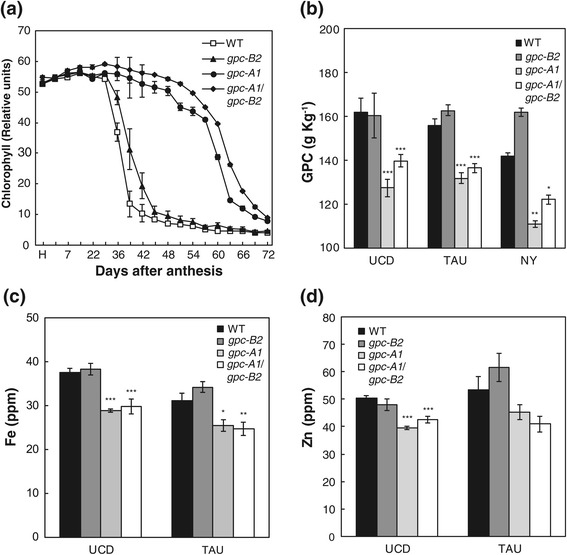

Field experiments comparing wild type (WT), single (gpc-A1 and gpc-B2), and double (gpc-A1/gpc-B2) mutants showed consistent results across the four tested environments (UCD-2012, TAU-2012, NY-2012 and NY-2013, Figure 2, Additional file 1: Figure S1 and S2). None of the gpc mutants showed significant differences in heading time relative to the WT, which is consistent with the known upregulation of the GPC genes after anthesis [44]. Both the gpc-A1 and gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutants were associated with a significant delay in senescence relative to the WT and the gpc-B2 mutant. In the Davis field experiment (UCD-2012), these two mutants showed a 27-day delay in the onset of senescence in comparison to WT plants (Figure 2a), and consistent results were observed in field experiments carried out in Tel Aviv and Newe Ya’ar (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The differences in senescence observed between WT and gpc-B2 or between gpc-A1 and gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutants were comparatively much smaller (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

GPC mutations in tetraploid wheat result in significant delays in senescence and reductions in protein, Zn and Fe content in the grain. (a) Relative chlorophyll content of flag leaves taken from the UCD-2012 field experiment (b) GPC content of mature grains harvested from three experiments, (UCD n = 10, TAU and NY n = 4) (c) Fe and (d) Zn content of mature grains harvested from UCD-2012 and TAU-2012 experiments (n = 5). * = P < 0.5, ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001, difference when compared to WT control sample from Dunnett’s test. UCD = UC Davis 2012 experiment, TAU = Tel Aviv University 2012 experiment, NY = Newe Ya’ar research center 2012 experiment.

To test the effects of the GPC mutations on yield components in a tetraploid background, we measured thousand kernel weight (TKW) in three field environments and dry spike weight in the Davis field experiment. We detected a marginally significant reduction in TKW associated with the gpc-A1 and gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutant genotypes (P =0.02, Additional file 1: Figure S2a). These mutant genotypes were also associated with significant reductions in dry spike weight in the Davis field experiment which was lower in both gpc-A1 and gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutants at 35 DAA (P <0.001) and in the gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutant at 42 and 49 DAA (P <0.001, Additional file 1: Figure S2b).

The delays in the onset of senescence in the gpc-A1 and gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutants relative to WT plants were associated with reductions in protein, Zn and Fe levels in the mature grain (Figure 2, b-d). Similarly, the marginal differences in senescence between WT and gpc-B2 or between gpc-A1 and gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutants (Figure 2a) were paralleled by the absence of significant differences in protein, Zn and Fe levels in the grain in the different field experiments (Figure 2, b-d). Similar reductions in GPC were observed across the different field experiments (Figure 2b), which ranged between 19.5% (WT vs. gpc-A1) and 13.4% (WT vs. gpc-A1/gpc-B2). Micronutrient concentrations in the mature grain for each genotype in UCD-2012 and TAU-2012 experiments are presented in Additional file 1: Table S1. Fe concentrations in the grain were significantly lower in both the gpc-A1 (20.9% mean reduction) and gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutants (20.8% mean reduction) when compared to WT samples in both locations (Figure 2c). Zn grain concentrations were also lower for the same mutant genotypes in both locations, but the differences were significant only in the UCD-2012 experiment (Figure 2d). Interestingly, gpc-A1 and gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutants also exhibited significantly higher grain K concentrations than in WT plants, with increases ranging between 18 and 33% (Additional file 1: Table S1). All GPC and micronutrient values are reported as the concentration within the grain, so are unaffected by the variation in TKW detected between genotypes.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that a knockout mutation of the GPC1 gene alone is sufficient to delay the onset of senescence and to perturb the translocation of protein, Zn and Fe to the developing grain in tetraploid durum wheat under field conditions. The gpc-B2 mutation had no significant effect on any of these traits, even in a genetic background with no functional GPC1 genes.

Evaluation of the mapping reference used for RNA-seq and overall characterization of loci expressed in each sample

To identify GPC-mediated transcriptional changes associated with the onset of senescence, we carried out an RNA-seq study focusing on three genotypes; WT and the two mutants that showed the largest differences in senescence in the previous field experiments, gpc-A1 and gpc-A1/gpc-B2. None of the plants sampled at heading date (HD), 12 days after anthesis (DAA) or 22 DAA, showed signs of chlorophyll degradation in the flag leaves or yellowing of the peduncles (Additional file 1: Figure S3, a-c), confirming that the selected time points represent relatively early stages of the senescence process. Clear differences between genotypes were apparent five weeks later (60 DAA), when the WT plants showed more advanced symptoms of senescence than either of the two gpc mutants (Additional file 1: Figure S3, d-f). This result indicates that in this greenhouse experiment, the effects of the GPC genes were consistent with those observed in the field experiments described above (Figure 1a).

On average, 35 million trimmed RNA-seq reads were generated for each of the four replicates of each of the nine genotype/time point combinations included in this study (Additional file 1: Table S2, total 1.3 billion reads). Most of the reads (average 99.0%) were mapped to the reference genomic contigs generated by the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC) using flow-sorted chromosomes arms of T. aestivum cv. Chinese Spring [48]. Since we were mapping transcripts of a tetraploid wheat cultivar, only the sequences from the A and B genome chromosome arms were used as a reference.

A large proportion of the trimmed reads (average 93.4%, Additional file 1: Table S2) mapped within the 139,828 previously defined transcribed genomic loci within this reference (see Methods), suggesting that these loci provide a good representation of the transcribed portion of the wheat genome. However, only 58.5% of these reads mapped to unique locations (Additional file 1: Table S2), most likely due to a combination of the high level of similarity shared by the coding regions of A and B homoeologs (average identity = 97.3%, standard deviation = 1.2%, [49]), and the short length of the reads used in this study (50 bp). Ambiguously mapped reads were excluded from the statistical analyses described below, resulting in an average of 20.4 M uniquely mapped reads per sample.

After excluding ambiguously mapped reads, only 80,168 of the genomic loci showed transcript coverage above the selected threshold for the statistical analyses (>3 reads for at least two biological replicates, within at least one genotype/time point pair, see Methods). The complete list of statistical analyses performed for these 80,168 loci is summarized in Additional file 2. Probability values for all four statistical tests are presented in this table so researchers can reanalyze the data using different statistical analyses and levels of stringency for specific sets of genes. Where available, this table also describes the high-confidence protein coding gene corresponding to each genomic locus, derived from the recent annotation of these wheat genomic contigs [48].

Principal component analysis (PCA) of the uniquely mapped reads at each time point showed limited clustering of the samples according to their genotype at HD (Additional file 1: Figure S4a), very clear groupings at 12 DAA (Additional file 1: Figure S4b), and intermediate clustering at 22 DAA (Additional file 1: Figure S4c). The reciprocal analysis, to distinguish samples according to time point within each genotype, showed that in all three genotypes, the HD samples were more clearly separated than the two later time points (Additional file 1: Figure S4, d-f). The clearer separation of both gpc mutants from the WT, and of gpc-A1 from gpc-A1/gpc-B2 at 12 DAA than at either HD or 22 DAA, suggests that both GPC1 and GPC2 genes have a major regulatory role at this early stage of senescence (12 DAA).

Following mapping, we confirmed the genotype of each sample by analyzing pileups of reads which mapped to the genomic loci corresponding to the GPC-A1 and GPC-B2 genes. The expected TILLING mutations (G561A = W114* for gpc-A1 and G516A = W109* for gpc-B2) were confirmed in the expected mutant genotypes and were absent in all WT samples. All GPC genes showed a low number of mapped reads at HD, with significant increases at 12 DAA and 22 DAA (Additional file 1: figure S5). Approximately 3-4-fold more reads mapped to GPC1 homoeologous genes than to the GPC2 genes, a pattern which was consistent across all genotypes (Additional file 1: Figure S5).

We detected no significant differences in the expression profiles of GPC-A1 and GPC-B2 between WT and gpc mutant genotypes suggesting that the mutations in these genes did not affect the stability of the transcribed mRNAs, and that neither GPC-A1 nor GPC-B2 functional proteins exhibit a feedback regulatory mechanism on their own transcription (Additional file 1: Figure S5). However, at 22 DAA, GPC-A2 expression was significantly lower in WT plants than in either gpc-A1 (P = 0.024) or gpc-A1/gpc-B2 (P = 0.004) mutants, suggesting that there may exist some GPC-mediated feedback mechanism on the regulation of GPC-A2 transcript levels (Additional file 1: Figure S5).

Identification of loci differentially expressed during monocarpic senescence in WT plants

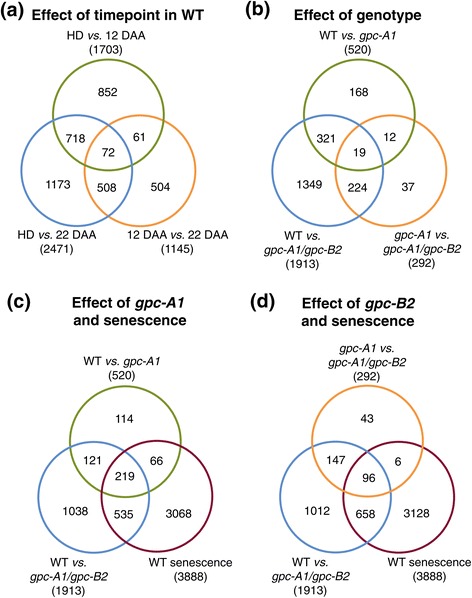

Applying stringent selection criteria (significant according to four different statistical tests, see Methods), we identified 3,888 contigs which were differentially expressed (DE) in at least one pairwise comparison among sampling times in the WT genotype (Figure 3a). As expected, the comparison between HD and 22 DAA showed the largest number of DE loci (2,471), followed by the comparison between HD and 12 DAA (1703). The comparison between 12 DAA and 22 DAA showed the lowest number of DE loci (1,145, Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Overlap of DE genes (a) Between time points in WT samples, (b) Between different GPC genotype comparisons, (c) Between GPC-A1- regulated loci and senescence regulated loci and (d) Between GPC-B2- regulated loci and senescence regulated loci.

Of the loci which were significantly DE in the WT plants between HD and 12 DAA, a larger proportion were upregulated (76.2%) than were downregulated (23.8%). The reverse was true for loci DE between 12 DAA and 22 DAA, when 30.2% of loci were upregulated and 69.8% were downregulated. This suggests that during the first 12 DAA different mechanisms required to actively prepare the plant for the upcoming senescence are upregulated, which is followed by the shutdown of many biological processes and the downregulation of a large number of genes.

We next determined whether any previously characterized senescence associated genes were also differentially expressed in our dataset. In a wheat microarray study, 165 annotated genes were identified which were differentially expressed during eight stages of senescence, ranging from anthesis to yellowing leaves [40]. We identified the corresponding genes within our dataset using BLAST (P ≤ 1e−5) and found that 26 (15.8%) were also significantly differentially expressed during senescence in the current study (Additional file 1: Table S3). This relatively low percent is not unexpected since our study covers only the early stages of senescence whereas the previous study covered a more extended period. A second microarray experiment in barley identified a set of genes differentially expressed between NILs divergent for a high-GPC genomic segment at 14 DAA and at 21 DAA [38]. In the leaves, 2,276 genes were upregulated in at least one of these time-points and 1,193 were downregulated. Among the upregulated genes, we identified 100 which were also significantly up-regulated during senescence, and of the down-regulated genes, 96 were also significantly down-regulated within our dataset, which used different statistical stringency criteria. The use of different technologies (microarray vs RNA-seq) and different species may also contribute to the different sets of differentially expressed genes detected in these studies. The genes regulated by senescence in both experiments are listed in Additional file 1: Table S4.

This study in tetraploid wheat supersedes our previous RNA-seq analysis in hexaploid wheat comparing the transcriptomes of WT and transgenic GPC-RNAi lines with reduced transcript levels of GPC1 and GPC2 at 12 DAA [39]. In the current study, we generated a greater number of reads, studied additional time-points, used targeted knockouts of individual GPC genes and had access to a more comprehensive wheat genome mapping reference. Among the differentially expressed genes common to both studies were three genes of biological interest selected for validation in the previous study [39].

Identification of loci differentially expressed among GPC genotypes

We next identified loci which were DE between genotypes. The largest number of DE loci was detected between the WT and the double gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutants (1,913 loci), an expected result given that this comparison includes genes regulated by both GPC-A1 and GPC-B2 (Figure 3b). The comparison between the WT and the single gpc-A1 mutant, expected to detect mainly GPC-A1-regulated genes, showed a much lower number of DE genes (520 loci) than the previous comparison. A total of 321 of these loci (62%, Figure 3b) were DE in both these comparisons and are designated hereafter as high-confidence GPC-A1-regulated genes. The third comparison, between the gpc-A1 and gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutant genotypes, expected to detect mainly genes regulated by GPC-B2, yielded a lower number of DE loci (292). Most of these loci (224 = 77%, Figure 3b) were also DE in the comparison between the WT and the gpc-A1/gpc-B2 double mutant and are designated hereafter as high-confidence GPC-B2-regulated genes. There were 19 loci which were DE in all three comparisons between genotypes, and these likely represent genes redundantly regulated by both GPC-A1 and GPC-B2 genes (Figure 3b). Similarly, the 1,349 loci DE only between the WT and double gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutants but not in the other two classes (Figure 3b), likely include loci that are redundantly regulated by both genes, but that show significant differences in expression only when mutations in both GPC paralogs are combined.

To determine how these differences between genotypes were distributed in time, we made pairwise comparisons between genotypes within each of the three time points. Since both GPC1 and GPC2 expression is relatively low at HD (Additional file 1 : Figure S5), we expected to find a small number of DE loci among GPC genotypes at this time point. Indeed, only ten genes were DE between WT and the gpc-A1 single mutant, only six between WT and the gpc-A1/gpc-B2 double mutant and 19 between the gpc-A1 and gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutants at HD. Two loci were shared between the WT vs. gpc-A1/gpc-B2 and gpc-A1 vs. gpc-A1/gpc-B2 comparisons, suggesting they may potentially be regulated by GPC-B2 and one gene was common to the WT vs. gpc-A1 and WT vs. gpc-A1/gpc-B2 comparisons, suggesting it may be regulated by GPC-A1. These results confirm that GPC genes have only a marginal effect on the wheat transcriptome at this developmental stage.

By contrast, the number of DE loci between genotypes was much greater at 12 DAA. Of the 520 loci DE between WT and the gpc-A1 single mutant, 504 (96.9%) were DE at 12 DAA and only six (1.1%) at 22 DAA. Similarly, of the 1,913 loci DE between WT and the gpc-A1/gpc-B2 double mutant 1,525 (79.7%) were DE at 12 DAA, whereas only 385 (20.1%) were DE at 22 DAA. Of the 292 DE genes in the comparison between the gpc-A1 single mutant and the gpc-A1/gpc-B2 double mutant, 239 were DE at 12 DAA, whereas only 38 genes were DE at 22 DAA. These results suggest that even though GPC1 and GPC2 expression continues to rise between 12 DAA and 22 DAA (Additional file 1 Figure S5), the major effect of both these genes on the regulation of downstream genes occurs at 12 DAA.

We next compared the two sets of high-confidence GPC-regulated loci with the senescence-regulated loci. A broad overlap was detected between GPC-A1-regulated and senescence-regulated loci, with 206 of the 321 (64.2%) high-confidence GPC-A1-regulated loci also DE during senescence (Figure 3c). By contrast, of the 224 high-confidence GPC-B2-regulated loci only 83 (37.1%) were also DE during senescence (Figure 3d). Surprisingly, 81% of the genes upregulated during the first 12 DAA in WT plants (1,054 genes) were no longer significant in the gpc-A1 mutant. This observation highlights the critical role of GPC1 in the activation of a large number of genes during the early stages of monocarpic senescence, possibly to prepare the plant for the upcoming senescence.

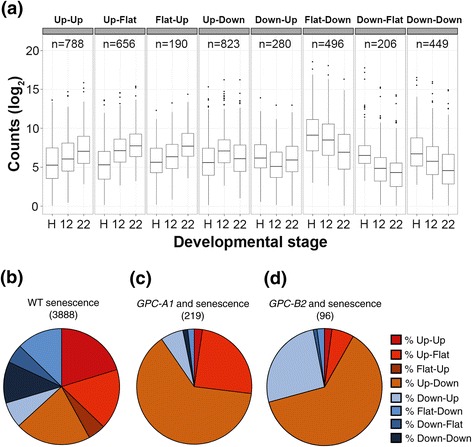

Distribution of expression profiles among different genotypic classes

To further analyze the loci DE during senescence, we classified them into eight classes based on their upregulation (Up), downregulation (Down) or absence of significant differences (Flat) between HD and 12 DAA, and between 12 DAA to 22 DAA (Figure 4a). Loci which were not significantly DE in either of these comparisons, but were significantly up or downregulated between HD and 22 DAA were included in the ‘Up-Up’ and ‘Down-Down’ classes, respectively. When all 3,888 loci DE during senescence in WT plants were considered (Figure 4, a-b) all eight classes were well represented with slightly higher proportions in the three classes that include loci upregulated between HD and 12 DAA (‘Up-Down’: 21.2%, ‘Up-Up’: 20.3% and ‘Up-Flat’: 16.9%). A different picture emerged when, among the loci DE during senescence, we considered only the high-confidence GPC-A1 (219) and GPC-B2 (96) regulated genes. In both cases the ‘Up-Down’ class was dominant, representing 63.5% and 62.5% of the DE loci, respectively (Figure 4, c and d). However, a difference between these two groups was evident in the second most abundant class; ‘Up-Flat’ in the high-confidence GPC-A1-regulated genes (24.7%), and ‘Down-Up’ in the high-confidence GPC-B2-regulated genes (26.0%, Figure 4, c and d). In both groups, the remaining six classes represented less than 12% of the DE loci. These data indicate that while both genes have their greatest effect at 12 DAA, a partial differentiation exists of the loci and processes regulated by the GPC-A1 and GPC-B2 genes.

Figure 4.

Expression profiles during senescence. (a) Boxplot of log2 normalized counts for WT samples over three time points during senescence, separated according to their expression profiles in 8 classes. Classes were defined based on the existence of significant (‘Up’ and ‘Down’) or non-significant differences (‘Flat’) between time point comparisons. (b-d) Proportion of expression classes among loci DE during senescence in (b) WT (3888 loci), (c) high-confidence GPC-A1-regulated loci (219 loci) and (d) high-confidence GPC-B2-regulated loci (96 loci). Loci included in C and D are based on the intersections of the three classes shown in Figure 3, c and d. H = Heading Date, 12 = 12 days after anthesis, 22 = 22 days after anthesis.

Gene ontology analysis

We next used BLAST2GO to generate ‘Biological Process’ Gene Ontology (GO) terms for each locus to compare the proportions of different functional categories between loci up- and downregulated during senescence in WT and between high-confidence GPC-A1- and GPC-B2-regulated loci (Table 1). To simplify the description of these functional analyses, we first combined the eight functional categories from Figure 4a into four: upregulated loci (combining ‘Up-Up’, ‘Up-Flat’ and ‘Flat-Up’ categories), downregulated loci (combining ‘Down-Down’, ‘Down-Flat’ and ‘Flat-Down’ categories), ‘Up-Down’, and ‘Down-Up’.

Table 1.

Top significantly enriched ‘Biological Process’ GO terms among upregulated and downregulated genes during monocarpic senescence in wheat and in the 316 high-confidence GPC-A1- and 224 GPC-B2- regulated genes

| Accession | Ontology | Annotated | Significant | Expected | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | GO:0055114 | Oxidation-reduction process | 3168 | 171 | 87.5 | 2.60E-18 |

| GO:0055085 | Transmembrane transport | 1622 | 90 | 44.8 | 2.20E-10 | |

| GO:0071577 | Zinc ion transmembrane transport | 20 | 8 | 0.55 | 3.10E-08 | |

| GO:0034220 | Ion transmembrane transport | 369 | 31 | 10.19 | 4.90E-08 | |

| GO:0006829 | Zinc ion transport | 24 | 8 | 0.66 | 1.60E-07 | |

| GO:0043562 | Cellular response to nitrogen levels | 14 | 6 | 0.39 | 1.10E-06 | |

| GO:0009064 | Glutamine family amino acid metabolic process | 65 | 11 | 1.8 | 1.50E-06 | |

| GO:0006787 | Porphyrin-containing compound catabolic process | 76 | 11 | 2.1 | 7.40E-06 | |

| GO:0033015 | Tetrapyrrole catabolic process | 76 | 11 | 2.1 | 7.40E-06 | |

| GO:0051187 | Cofactor catabolic process | 76 | 11 | 2.1 | 7.40E-06 | |

| Downregulated | GO:0015979 | Photosynthesis | 502 | 123 | 11.06 | <1e-30 |

| GO:0009765 | Photosynthesis, light harvesting | 76 | 47 | 1.67 | <1e-30 | |

| GO:0019684 | Photosynthesis, light reaction | 340 | 69 | 7.49 | <1e-30 | |

| GO:0006091 | Generation of precursor metabolites and energy | 774 | 78 | 17.06 | 1.70E-29 | |

| GO:0033014 | Tetrapyrrole biosynthetic process | 183 | 30 | 4.03 | 9.60E-18 | |

| GO:0015977 | Carbon fixation | 45 | 17 | 0.99 | 3.40E-17 | |

| GO:0006779 | Porphyrin-containing compound biosynthetic process | 161 | 27 | 3.55 | 2.30E-16 | |

| GO:0015995 | Chlorophyll biosynthetic process | 122 | 23 | 2.69 | 2.80E-15 | |

| GO:0033013 | Tetrapyrrole metabolic process | 262 | 31 | 5.77 | 3.20E-14 | |

| GO:0055114 | Oxidation-reduction process | 3168 | 134 | 69.81 | 5.50E-14 | |

| GPC1- regulated | GO:0005385 | Zinc ion transmembrane transporter activity | 29 | 13 | 0.14 | 2.00E-23 |

| GO:0046915 | Transition metal ion transmembrane transmembrane activity | 68 | 13 | 0.32 | 7.80E-18 | |

| GO:0072509 | Divalent inorganic cation transmembrane activity | 95 | 13 | 0.44 | 7.80E-16 | |

| GO:0046873 | Metal ion transmembrane transporter activity | 317 | 15 | 1.48 | 3.00E-11 | |

| GO:0022890 | Inorganic cation transmembrane transport activity | 472 | 15 | 2.21 | 7.20E-09 | |

| GO:0022891 | Substrate-specific transmembrane transport | 1016 | 20 | 4.76 | 6.60E-08 | |

| GO:0015075 | Ion transmembrane transporter activity | 911 | 18 | 4.26 | 3.00E-07 | |

| GO:0022892 | Substrate-specific transporter activity | 1132 | 20 | 5.3 | 3.70E-07 | |

| GO:0008324 | Cation transmembrane transporter activity | 647 | 15 | 3.03 | 4.30E-07 | |

| GO:0005215 | Transporter activity | 1989 | 26 | 9.31 | 1.90E-06 | |

| GPC2- regulated | GO:0009834 | Secondary cell wall biogenesis | 17 | 2 | 0.03 | 0.00041 |

| GO:0009832 | Plant-type cell wall biogenesis | 52 | 2 | 0.09 | 0.00382 | |

| GO:0007017 | Microtubule-based process | 379 | 4 | 0.67 | 0.00446 | |

| GO:0006812 | Cation transport | 948 | 6 | 1.67 | 0.00623 | |

| GO:0071669 | Plant-type cell wall organization or biogenesis | 69 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.00664 | |

| GO:0006811 | Ion transport | 1285 | 7 | 2.27 | 0.00701 | |

| GO:0007029 | Endoplasmic reticulum organization | 5 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.00879 | |

| GO:0015801 | Aromatic amino acid transport | 5 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.00879 |

Among loci upregulated during senescence, we observed enrichment in transport functions and catabolism of photosynthetic proteins. Four of the top five most significantly enriched GO terms included those related to transmembrane transporter function (Table 1). By contrast, loci downregulated during senescence were enriched in functions related to biosynthetic processes, especially photosynthesis (Table 1). These results, together with the previous observation that upregulated loci were more abundant between WT and 12 DAA (76.2%) and downregulated loci were more abundant between 12 and 22 DAA (69.8%), are indicative of the early activation of catabolic enzymes and transport systems followed by the downregulation of growth promoting processes in the leaves during these two early stages of senescence.

GO term analysis among the 321 high-confidence GPC-A1-regulated genes showed a significant enrichment of categories similar to the patterns observed for loci upregulated during senescence, with the ten most significantly enriched terms all relating to transporter activity (Table 1). Although transporter functions were also enriched among the 224 high-confidence GPC-B2-regulated genes, several unrelated terms were also enriched in this class but not in the GPC-A1-regulated class, including genes with putative roles in cell wall biogenesis and microtubule organization.

The closer similarity in GO term enrichment between senescence-regulated loci and GPC-A1-regulated genes than with GPC-B2-regulated genes is consistent with the greater overlap between senescence-regulated and GPC-regulated loci (64.2% overlap for GPC-A1 vs. 37.1% overlap for GPC-B2, Figure 3, c and d) and with the relatively stronger effect of the gpc-A1 mutation on senescence and nutrient transport relative to the gpc-B2 mutation (Figure 1, a-d). Taken together, these results suggest that GPC-A1 plays a more important role than GPC-B2 in the regulation of genes controlling the early stages of monocarpic senescence in wheat.

Identification and expression analysis of wheat transporter genes

To categorize the wheat transporters upregulated during senescence and to determine the role of GPC1 in their regulation, we identified specific wheat homologues of Fe and Zn transporters previously characterized in other plant species and determined their expression profiles both among different time points during senescence and between GPC genotypes.

Chloroplastic transporters

Among genes previously known to be involved in the reduction-based import of Fe into the chloroplasts, we identified two FRO genes in Triticum aestivum (Ta), one of which, TaFRO1, was highly expressed at HD and significantly downregulated during senescence in WT plants (Table 2). By comparison, TaFRO2 expression was lower, and although its expression also fell during senescence, differences between time points were not significant. Neither gene was significantly DE among genotypes.

Table 2.

Wheat transporters and their expression during senescence

| Transporter | WT counts* | Differential expression** | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | Wheat | Chromosome | IWGSC ID | HD | 12D | 22D | Senescence | gpc-A1 | gpc-A1/B2 |

| Chloroplastic transporters | |||||||||

| OsFRO1 | TaFRO1 | 2AL | Traes_2AL_2A274FDB8 | 40,148 | 22,892 | 16,515 | |||

| 2BL | Traes_2BL_C7CDCB39A | 48,913 | 30,272 | 13,838 | ⬇ | ||||

| OsFRO2 | TaFRO2 | 2AL | Traes_2AL_7E818894E | 3 | 1 | 6 | |||

| 2BL | Traes_2BL_E11AA2D03 | 49 | 8 | 9 | |||||

| OsHMA1 | TaHMA1 | 7AL | Traes_7AL_84D5BAE85 | 1,143 | 1,256 | 1,249 | |||

| 7BL | Traes_7BL_041308E74 | 674 | 614 | 600 | |||||

| TaHMA1-like | 5AL | Traes_5AL_C89EEBE50 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| 5BL‡ | Traes_5BL_F83C809F0 | 74 | 78 | 116 | |||||

| OsHMA2 | TaHMA2 | 7AL | Traes_7AL_8304348B7 | 125 | 328 | 1,079 | ⬆ | ||

| 7BL | Traes_7BL_C46BC291C/ Traes_7BL_8C24C1025 | 185 | 356 | 1,205 | ⬆ | ||||

| TaHMA2-like | 7AL | Traes_7AL_6AE850114 | 13 | 75 | 188 | ⬆ | ⬆ | ⬆ | |

| 7BL | Traes_7BL_0CF58CF4E | 2 | 13 | 17 | ⬆ | ||||

| OsHMA3 | TaHMA3 | 5BL | Traes_5BL_D6C3DC326 | - | - | - | |||

| Vacuolar transporters | |||||||||

| OsVIT1 | TaVIT1 | 2AL | Traes_2AL_A3A25F40E | 59 | 44 | 36 | |||

| 2BL | Traes_2BL_54954138A | 74 | 61 | 54 | |||||

| OsVIT2 | TaVIT2 | 5BL | Traes_5BL_7CE3EDE29 | 1,938 | 566 | 450 | |||

| OsNRAMP1 | TaNRAMP1 | 7AL | Traes_7AL_76159C6DA | - | - | - | |||

| 7BL | Traes_7BL_03741F576 | 3 | 6 | 1 | |||||

| OsNRAMP2 | TaNRAMP2 | 4AS | Traes_4AS_BBF51CA2E | 437 | 927 | 3,607 | ⬆ | ||

| 4BL | Traes_4BL_C6A3F5C8A | 637 | 743 | 2,252 | |||||

| OsNRAMP3 | TaNRAMP3 | 7AL | Traes_7AL_08B2A7BB2 | 640 | 704 | 469 | |||

| 7BL | Traes_7BL_CA6B7C9E6 | 551 | 571 | 352 | |||||

| OsNRAMP4 | TaNRAMP4 | 6AS | Traes_6AS_B9B4AD633 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 6BS | N/A | 3 | 5 | 5 | |||||

| OsNRAMP5 | TaNRAMP5 | 4AS | Traes_4AS_5D4904831 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 4BL | Traes_4BL_04B01EA0C/ Traes_4BL_CFD804098 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| None | TaNRAMP6 | 3AS | Traes_3AS_538630B00 | - | - | - | |||

| 3B | Traes_3B_73F0469A5 | 10 | 9 | 19 | |||||

| OsNRAMP7 | TaNRAMP7 | 5AS | Traes_5AS_213BE4D84 | 215 | 176 | 151 | |||

| 5BS | Traes_5BS_DE1CD2DA4 | 127 | 88 | 103 | |||||

| None | TaNRAMP8 | 4AL | Traes_4AL_2E796609C | - | - | - | |||

| 4BS | Traes_4BS_9337E9B2F | - | - | - | |||||

| OsZIFL1 | TaZIFL1 | 3AS | Traes_3AS_C25151458 | 378 | 73 | 19 | ⬇ | ||

| 3B | Traes_3B_BD45F6269/ Traes_3B_45F864939 | 249 | 45 | 5 | ⬇ | ||||

| OsZIFL1 | TaZIFL1-like1 | 3AS | Traes_3AS_02DE247DA | 125 | 136 | 84 | |||

| 3B | Traes_3B_92383792E/ Traes_3B_B76607C0E | 70 | 76 | 59 | |||||

| OsZIFL2 | TaZIFL2 | 5BL | Traes_5BL_A0B9DE62E | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| OsZIFL2 | TaZIFL2-like1 | 3AS | Traes_3AS_E59FB52EC | 8 | 31 | 32 | ⬆ | ||

| 3B | Traes_3B_EDFDD5A12 | 167 | 305 | 383 | |||||

| None | TaZIFL3 | 4AL | Traes_4AL_4231650FC/ Traes_4AL_470869233 | 183 | 218 | 171 | |||

| 4BS | Traes_4BS_1DCF82CB7 | 525 | 1,019 | 743 | ⬆ | ||||

| None | TaZIFL7 | 5AL | Traes_5AL_37BFFFD9E | 397 | 392 | 249 | ⬆ | ⬆ | |

| 5BL | Traes_5BL_6E4AE0146 | 130 | 108 | 48 | |||||

| None | TaZIFL8 | 4AL | Traes_4AL_5C7A4DA54 | 21 | 19 | 13 | |||

| 4BS | Traes_4BS_44732F50F | 141 | 112 | 160 | |||||

| None | TaZIFL9 | 5AL | Traes_5AL_0599F7BC5 | - | - | - | |||

| 5BL | N/A | - | - | - | |||||

| Plasma membrane transporters | |||||||||

| OsYSL1 | TaYSL1 | 3AS | Traes_3AS_FB4110335 | 10 | 7 | 8 | |||

| 3B | Traes_3B_17BC3E1E2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| OsYSL2 | TaYSL2 | 6AL | Traes_6AL_850660AC3 | 56 | 35 | 53 | |||

| 6BL | Traes_6BL_3DD0BA741 | 51 | 61 | 62 | |||||

| OsYSL6 | TaYSL6 | 2AL | Traes_2AL_7B0F93F84 | 364 | 526 | 986 | ⬆ | ||

| 2BL | Traes_2BL_0CBCC13AD | 68 | 101 | 203 | |||||

| OsYSL9 | TaYSL9 | 2AL | Traes_2AL_CFCA01C76 | 725 | 995 | 1,517 | ⬆ | ||

| 2BL | N/A | 15 | 18 | 28 | |||||

| OsYSL10 | TaYSL10 | 6AL | Traes_6AL_5642D5B44 | 42 | 46 | 35 | |||

| OsYSL11 | TaYSL11 | 2AL | Traes_2AL_377C8CDEA | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 2BL | Traes_2BL_68E0CA743 | 3 | 5 | 3 | |||||

| OsYSL12 | TaYSL12 | 2AL‡ | Traes_2AL_CC6133527 | 554 | 701 | 1,389 | |||

| 2BL | Traes_2BL_2BE05F104 | 437 | 563 | 454 | ⬇ | ||||

| OsYSL13 | TaYSL13 | 2AL | Traes_2AL_F707FF2C3.3 | 14 | 20 | 75 | |||

| 2BL | Traes_2BL_A14EA5AE4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| TaYSL13-like | 2BL | Traes_2BL_A14EA5AE4 | 7 | 19 | 85 | ||||

| OsYSL14 | TaYSL14 | 6AL | Traes_6AL_7FB45D4DE | 814 | 894 | 733 | |||

| 6BL | Traes_6BL_7FFC46B84 | 500 | 628 | 493 | |||||

| OsYSL15 | TaYSL15 | 6AL | Traes_6AL_E36FCEF64 | 523 | 486 | 969 | |||

| 6BL | Traes_6BL_D65EC1432 | 88 | 95 | 199 | |||||

| TaYSL15-like | 1AL | Traes_1AL_C6A0E255E | 4 | 7 | 9 | ||||

| 1BL | Traes_1BL_CA93E6359 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| OsYSL16 | TaYSL16 | 2BL | Traes_2BL_4A1181B731 | 2,736 | 2,361 | 2,011 | |||

| None | TaYSL18 | 2AL | Traes_2AL_2F91AF932 | 225 | 144 | 84 | ⬇ | ||

| 2BL | Traes_2BL_6C5206B6D | 531 | 499 | 510 | |||||

| OsIRT1 | TaIRT-like1 | 4AL | Traes_4AL_9D79BE8FB | 5 | 7 | 10 | |||

| 4BS | Traes_4BS_6527BBD54 | 8 | 6 | 7 | |||||

| OsIRT2 | TaIRT-like 2 | 4AL | Traes_4AL_9F6B106F3 | 9 | 21 | 30 | ⬆ | ||

| OsZIP10 | TaZIP10 | 7AL | Traes_7AL_A13A246B4 | 333 | 596 | 531 | ⬆ | ⬆ | |

| 7BL | Traes_7BL_E5CFC3DCE/ Traes_7BL_5C965DB64 | 267 | 531 | 482 | ⬆ | ⬆ | |||

| OsZIP10 | TaZIP10-like1 | 7AL | Traes_7AL_F1D611563/ Traes_7AL_893DEB3EB | 7 | 229 | 279 | ⬆ | ⬆ | ⬆ |

| 7BL | Traes_7BL_12C63350C | 5 | 654 | 647 | ⬆ | ⬆ | ⬆ | ||

| OsZIP8 | TaZIP13-like1 | 6BS | Traes_6BS_7D630200B | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| TaZIP13-like2 | 2AS | Traes_2AS_4CA7607E5 | 277 | 4,469 | 3,207 | ⬆ | ⬆ | ⬆ | |

| 2BS | Traes_2BS_9D8F265EC | 79 | 916 | 787 | ⬆ | ⬆ | ⬆ | ||

| TaZIP13-like3 | 2AL | Traes_2AL_BE05B34FF | 125 | 129 | 135 | ||||

| 2BL | Traes_2BL_A1BCBD2BE | 102 | 1,613 | 1,466 | ⬆ | ⬆ | ⬆ | ||

| OsZIP1 | TaZIP1† | 3AL | Traes_3AL_DC3D5F65E | 2 | 1 | 4 | |||

| 3B | Traes_3B_3C18D89F8 | 3 | 4 | 8 | |||||

| OsZIP2 | TaZIP2† | 5BL | N/A | 17 | 9 | 9 | |||

| OsZIP2 | TaZIP2-like | 6AS | Traes_6AS_75C6428051 | - | - | - | |||

| 6BS | N/A | 73 | 65 | 34 | |||||

| OsZIP3 | TaZIP3† | 2AL | Traes_2AL_3983FD077 | 21 | 115 | 138 | ⬆ | ⬆ | ⬆ |

| 2BL | Traes_2BL_23F1C8743 | 61 | 130 | 291 | ⬆ | ⬆ | |||

| OsZIP5 | TaZIP5 | 4AS | Traes_4AS_F5F7D2A8D | 0 | 1 | 3 | |||

| 4BL | Traes_4BL_68691F1FC | 10 | 76 | 176 | ⬆ | ⬆ | |||

| OsZIP6 | TaZIP6† | 1AS | Traes_1AS_A6EF18CC1 | 527 | 488 | 439 | |||

| 1BS | Traes_1BS_B734EDEA7 | 413 | 532 | 478 | |||||

| OsZIP7 | TaZIP7† | 1AS | Traes_1AS_EC8891094/ Traes_1AS_50323685E | 216 | 606 | 880 | ⬆ | ⬆ | ⬆ |

| 1BS | Traes_1BS_D68F0BED6 | 317 | 1,194 | 1,566 | ⬆ | ⬆ | ⬆ | ||

| OsZIP11 | TaZIP11 | 1AS | Traes_1AS_7DC2CB902 | 378 | 357 | 519 | |||

| 1BS | N/A | 193 | 186 | 281 | |||||

| OsZIP13 | TaZIP15 | 6AS | Traes_6AS_4E1D574BC | 322 | 354 | 332 | |||

| 6BS | Traes_6BS_147BF2D07 | 726 | 678 | 513 | |||||

| OsZIP14 | TaZIP14† | 3AS | Traes_3AS_F46E02204/ Traes_3AS_15A221AD0 | 97 | 77 | 103 | |||

| 3B | Traes_3B_B7D3B69FD | 229 | 192 | 213 | |||||

| OsZIP16 | TaZIP16 | 7AL | Traes_7AL_DFE86911E | 15 | 14 | 9 | |||

| 7BL | Traes_7BL_2637B2942/ Traes_7BL_EB231D8FF | 12 | 13 | 6 | |||||

| PS biosynthesis genes | |||||||||

| OsNAS1 | TaNAS1 | 2AS | Traes_2AS_D50EEDA84 | 2 | 5 | 4 | |||

| 2BS | N/A | 121 | 117 | 117 | |||||

| OsNAS3 | TaNAS3 | 2AS | Traes_2AS_DEDC612AE/ Traes_2AS_452FED53F | 2,056 | 2,694 | 4,495 | ⬆ | ||

| 2BS | Traes_2BS_CB79BAFB1 | 5,362 | 5,109 | 7,789 | ⬆ | ||||

| OsNAAT1 | TaNAAT1 | 1AL | Traes_1AL_9D6B86169 | 47 | 88 | 102 | ⬆ | ⬆ | |

| OsNAAT1 | TaNAAT2 | 1AL | Traes_1AL_BCD7C5B8B | 127 | 280 | 269 | ⬆ | ⬆ | ⬆ |

| 1BL | Traes_1BL_D8276D3DB | 188 | 453 | 602 | ⬆ | ⬆ | |||

| OsDMAS1 | TaDMAS1 | 4AS | Traes_4AS_887399584 | 27 | 26 | 17 | |||

| 4BL | N/A | 1222 | 883 | 1134 | |||||

† Source: Tiong et al. [21]. All NRAMP genes from Borrill et al. [7]. TaDMAS from Bashir et al. [26]. ‡ Predicted non-functional protein.

*Counts are normalized values of reads uniquely mapped to the genomic loci corresponding to each wheat transporter gene. **Arrows indicate whether the gene was significantly upregulated (⬆) or downregulated (⬇) during senescence in WT plants or in WT vs. gpc-A1 or WT vs. gpc-A1/gpc-B2 comparisons (⬆ = significantly higher in WT).

Among genes previously known to promote the export of nutrients from the chloroplast to the cytoplasm, we identified five T. aestivum members of the Zn/Co/Cd/Pb-transporting class of HMA genes (see phylogeny in Additional file 1: Figure S6). Two of these genes, TaHMA2 and TaHMA2-like, which showed the highest similarity to OsHMA2 (Additional file 1: Figure S6), were significantly upregulated during senescence, both showing >6-fold increases in expression between HD and 22 DAA (Table 2). Furthermore, TaHMA2-like expression was significantly reduced in both gpc mutants, implicating a role for GPC in its regulation. Two other genes, TaHMA1 and TaHMA-like1 which are both similar to OsHMA1 (Additional file 1: Figure S6), were not DE during senescence and a third, TaHMA3, was not detected at any time point in this study.

Vacuolar transporters

Two VIT transporters, which promote Fe and Zn import in to the vacuole, were previously characterized in rice [13]. Both of the corresponding wheat homologues of these genes were downregulated ~4-fold during senescence, but these differences were not significant according to our stringent differential expression criteria (Table 2). Furthermore, neither gene was DE in either of the gpc mutant genotypes (Table 2).

Eight wheat ZIFL genes, thought to promote vacuolar sequestration of Zn [14], were identified and annotated in this study (see phylogeny in Additional file 1: Figure S7). Two TaZIFL genes (TaZIFL2 and TaZIFL9) were expressed at negligible levels in all time points included in this study and were excluded from further analyses (Table 2). Among the six TaZIFL genes which showed higher levels of expression during senescence, TaZIFL2-like1 and TaZIFL3 were significantly upregulated during senescence while TaZIFL1 was significantly downregulated. Interestingly, although it was not upregulated during senescence, TaZIFL7 expression was significantly higher in WT plants than in both gpc mutants (Table 2).

Among the genes known to promote Fe export from the vacuole to the cytoplasm, eight NRAMP genes were recently described in wheat [7]. Five of these genes showed very low levels of expression in flag leaves during the time points included in our study, suggesting that they may play more important roles during other developmental stages or in other tissues. Of the three NRAMP genes with higher expression levels during senescence, TaNRAMP3 and TaNRAMP7 both exhibited stable expression, but TaNRAMP2 was significantly upregulated, showing a ~5-fold increase in expression between HD and 22 DAA (Table 2). No significant differences among genotypes were detected for any of the NRAMP genes.

Plasma-membrane transporters

After being transported into the cytoplasm, Zn and Fe must be loaded into the phloem for their transport to different sink tissues, including the grain. In rice and barley, the YSL and ZIP gene families appear to play a prominent role in this process.

We identified a total of 14 YSL genes within available wheat databases (see phylogeny in Fig S8), but one of these genes is likely a pseudogene (Table 2). Among the functional YSL genes, TaYSL6 and TaYSL9 were significantly upregulated during senescence and TaYSL18 was significantly downregulated (Table 2). Although not DE during senescence, TaYSL12 expression was significantly reduced in the gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutant compared to the WT.

The largest transporter gene family described in this study is the ZIP family, with a total of 19 wheat genes identified (see phylogeny in Additional file 1: Figure S9), including seven which had been described previously [21]. This family also includes the Iron Regulated Transporter (IRT) genes, which share high similarity to the ZIPs. One gene (TaZIP13) was absent from the genomic reference so was excluded from the analysis, but five of the remaining 18 TaZIP genes were significantly upregulated during senescence (Table 2). Some of these genes showed very large increases in expression between time points. For example, TaZIP3 was upregulated 5-fold and TaZIP5 8-fold between HD and 12 DAA (Table 2). Strikingly, the expression of all five of these upregulated genes, as well as TaZIP10 and TaZIP5, was significantly higher in WT plants than in either gpc mutant genotype. Additionally, TaIRT2 expression was significantly lower in the gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutant than in the WT. These results strongly implicate a role for GPC1 in the regulation of the ZIP family of transporters during senescence (Table 2).

Phytosiderophore biosynthesis genes

Since the association of Zn and Fe with PS chelating ligands facilitates their transport through the phloem, we searched for wheat homologs of genes encoding enzymes acting in the PS biosynthetic pathway (Figure 1). Searches of available wheat genomic databases yielded two TaNAS, two TaNAAT and one TaDMAS genes.

Expression of TaNAS3 more than doubled between 12 DAA and 22 DAA, (although this difference was not significant according to our criteria) and was significantly reduced in gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutant compared to the WT (Table 2). In contrast, TaNAS1 was expressed at much lower levels and did not vary during senescence or among genotypes (Table 2).

Both of the identified wheat NAAT genes were upregulated during senescence, although only for TaNAAT2 was this significant (Table 2). Interestingly, TaNAAT2 was upregulated at an earlier stage than TaNAS3, since its expression doubled between HD and 12 DAA and remained stable thereafter (Table 2). The expression of both TaNAAT genes was significantly lower in both gpc mutant genotypes, suggesting a role for GPC in the regulation of this class of gene. The third PS biosynthesis gene, TaDMAS was not DE at any stage of senescence or in any of the genotype comparisons (Table 2).

As a technical control, we developed qRT-PCR assays for six transporter genes which were significantly DE between WT and gpc mutants. For all six genes, we obtained results that were consistent with the expression profiles determined by RNA-seq. Results from both analyses are presented side by side in Additional file 1: Figure S10.

To look for additional transporters, we further explored the group of 1,054 genes that were significantly upregulated between HD and 12 DAA in the WT plants but not in the gpc-A1 mutants. This dataset included 33 genes with annotated transporter function which were also significantly different among genotypes (P < 0.05), 11 of which were members of the characterized transporter families described above (Additional file 1: Table S5). The remaining 22 genes included members of other transporter families, including one potassium transporter (AKT2), two sulfate transporters, one ABC transporter and a gene encoding a ferritin protein, involved in Fe storage (Additional file 1: Table S5). The differential regulation of the potassium and sulfate transporters is particularly interesting given the significant differences in K and S concentrations in the grain detected between WT and both gpc-A1 and gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutants (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Taken together, our results suggest that the onset of monocarpic senescence in wheat is associated with broad transcriptional changes involved in nutrient remobilization. These processes included the export of Zn and Fe from chloroplasts and vacuoles (upregulation of NRAMP and HMA and downregulation of FRO, VIT and one ZIFL gene), upregulation of trans-membrane transporter genes responsible for loading nutrients into the phloem (ZIP and YSL), and upregulation of PS biosynthesis genes (NAS, NAAT) to facilitate transport of these nutrients through the phloem. Among these changes, the GPC genes seem to play a limited role in the regulation of vacuolar and chloroplastic transporter genes, but have a clear role in the upregulation of both PS biosynthesis genes and transmembrane transporters, with a particularly prominent role in regulating members of the ZIP gene family.

Discussion

In annual grasses, senescing leaves are an important source of Zn and Fe for the developing grain. When the transport mechanisms between these tissues are disrupted, as in the gpc mutants and GPC-RNAi transgenic plants described in this and previous studies [5,44,46], concentrations of Zn and Fe in the grain are significantly reduced. We used RNA-seq to characterize the overall transcriptional changes in senescing flag leaves in WT and gpc mutant plants. We identified several Zn and Fe transporter genes activated during these early stages of senescence and describe their regulation by the GPC genes.

Applying RNA-seq to polyploidy wheat

One challenge for genomic studies in polyploid species is the difficulty in distinguishing highly similar homoeologous genomes (~97% identical between A and B wheat genomes within protein-coding regions). Although different approaches to separate homoeologous sequences have been applied (e.g. Krasileva et al. [49]), it remains difficult to fully resolve chimeric assemblies. We overcame this problem in the current study by using the recently-released genomic draft sequence of wheat chromosome arms from the IWGSC as our RNA-seq mapping reference [48]. To generate the genomic draft sequence, wheat chromosome arms were first separated by flow cytometry, so each arm was sequenced and assembled separately, resulting in homoeolog-specific reference sequences.

At the time of our analysis, this genomic reference lacked any gene annotation so we first identified genomic ranges, which are defined by one or more overlapping transcripts (described in Methods). A large proportion of our reads mapped to these expressed loci (>93%), indicating that they include a good representation of the expressed portion of the wheat genome. Recently, the IWGSC annotated 65,776 high-confidence protein-coding genes in the A and B chromosome arms [48], 48,657 (74.0%) of which overlapped with loci identified in our study. The corresponding IWGSC loci and gene names for each matching locus are provided in Additional File 1. A small number of sequencing reads (average 209,660 reads per sample) mapped within genomic ranges defined by the 17,119 IWGSC loci not identified in our annotation, and were not included in the current study.

The use of a homoeolog-specific genomic reference instead of a transcriptome reduced mapping ambiguity in two ways; firstly by eliminating chimeric assemblies of similar homoeologous sequences, and secondly by collapsing multiple transcribed variant sequences into a single genomic locus in the reference, thus eliminating redundancy and increasing mapping specificity. This approach combines the expression of alternative splicing forms, which we consider appropriate for this initial study. A relatively high proportion of these reads were mapped uniquely (58.5%), and only these reads were used for our differential expression analyses, thus maximizing the accuracy of these analyses.

The role of GPC1 and GPC2 during monocarpic senescence

Previous studies have demonstrated that transgenic plants expressing an RNAi construct targeting all copies of GPC1 and GPC2 exhibit a significant delay in senescence and reduced levels of Zn, Fe and protein in the grain, due to a disruption in their transport [5,44]. In the current study, we also detected a marginally significant reduction in TKW and in dry spike weight during grain filling associated with the gpc1 mutant genotype. Interestingly, these differences were evident even from the early stages of senescence (35 DAA, Additional File 1: Figure S2b) suggesting that the GPC genes may also affect the rate of grain filling. Although the differences in spike weight between genotypes decreased with time, they were still significant at the end of the grain filling period (Additional file 1: Figure S2a). The high spring temperatures characteristic of the Mediterranean environments used in our studies, may have contributed to the lower kernel weight of the gpc mutant lines that matured during periods of higher temperature than the WT lines.

It was previously unknown whether GPC genes regulated the induction of the overall senescence process, or whether they regulated just a subset of the genes differentially regulated during this developmental stage. Also unclear was the time within the senescence process when the GPC genes have their strongest effect, or the extent of functional overlap between GPC1 and GPC2 paralogs. Results from our study provide insights into all three of these questions.

Comparing senescence- and GPC-regulated genes

To answer the first question, we investigated the overlap between senescence and GPC regulated genes. Of the 3,888 loci DE during senescence in WT plants, only 21.2% also showed significant differences in expression between GPC genotypes (Figure 3, c and d). In addition, within the senescence-regulated genes the subset regulated by the GPC genes showed different proportions of expression categories compared to the complete senescence set (Figure 4, b-d). Whereas more than 60% of GPC-regulated genes in this set exhibited an ‘Up-Down’ expression profile, the proportion in all senescence-regulated genes was 20%. Conversely, the proportion of genes exhibiting an ‘Up-Up’ expression profile and those falling into any of the downregulated classes were 9–10 fold more abundant among senescence-regulated genes than the subset regulated by GPC genes (Figure 4, b-d).

These results support the hypothesis that the GPC genes regulate a specific subset of genes during monocarpic senescence rather than triggering the overall transcriptional regulatory cascade associated with this developmental stage. The disruption of the regulation of this subset of senescence-regulated genes in the gpc mutants is likely sufficient to generate bottlenecks in the senescence process, as demonstrated by the overall delay in senescence observed in these mutant genotypes (Figure 2).

GPC-regulated genes at different time points

In a PCA analysis based on the expression of all genes, the differences between WT and gpc mutant genotypes were much clearer at 12 DAA than at either HD or 22 DAA (Additional file 1: Figure S4, a-c). This is consistent with our finding that the majority of GPC-regulated genes (76.1%) were detected at 12 DAA. These results suggest that, despite the continued increase in GPC expression between 12 DAA and 22 DAA (Additional file 1: Figure S5), most of the regulatory effects of the GPC genes on the DE of downstream genes occur within the first 12 DAA.

Comparison between GPC1 and GPC2 regulated genes

The paralogous genes GPC1 and GPC2 share 91% similarity at the DNA level and have almost identical expression profiles during the early stages of senescence (Additional file 1: Figure S5). Therefore, some functional overlap between these genes was expected. Among the three pairwise comparisons among genotypes (Figure 3b), the largest category includes the 1,349 DE genes detected between the WT and the gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutant, that were not among the GPC-A1-specific (WT vs. gpc-A1) or GPC-B2-specific (gpc-A1/gpc-B2 vs. gpc-A1) DE genes. This category most likely includes genes that are redundantly regulated by GPC-A1 and GPC-B2, but that are significant only when both genes are absent. Combining these 1,349 genes with the 31 which are DE in both GPC-A1-specific and GPC-B2-specific comparisons (Figure 3b), we conclude that approximately two-thirds of the GPC-regulated genes (64.8%) showed some level of redundancy in their regulation by GPC-A1 and GPC-B2. This result parallels the similar proportion of ‘Up-Down’ regulated genes among the high confidence GPC-A1- and GPC-B2-regulated genes (63.5% and 62.5%, respectively, Figure 4, c and d).

However, the remaining one-third of the loci DE among genotypes were regulated either by GPC-A1 (489) or by GPC-B2 (261), suggestive of some level of functional divergence. This was apparent in the differences between classes in expression profiles during senescence. Both sets of genes showed a strong enrichment for ‘Up-Down’ regulated genes, but the second most abundant category was ‘Up-Flat’ in the GPC-A1-regulated genes (24.7%) and ‘Down-Up’ in the GPC-B2-regulated genes (26.0%, Figure 4, c and d). These results suggest that GPC-A1 acts principally to upregulate genes during the early stage of senescence (WT to 12 DAA), whereas GPC-B2, in addition to its role in the upregulation of a number of genes, also targets a subset of genes for downregulation during the same period.

Distinctions between GPC-A1- and GPC-B2-regulated genes were also apparent in their putative functions identified in the GO analysis and in their respective overlap with senescence-regulated genes. The proportion of GPC-A1-regulated genes that were also regulated by senescence (64.2%) was almost double the corresponding proportion of GPC-B2-regulated genes (37.1%, Figure 3, c and d). Moreover, putative functions of the senescence regulated genes were more similar to the functions of GPC-A1-regulated genes than to those regulated by GPC-B2. Whereas both senescence-regulated and GPC-A1-regulated genes were significantly enriched for transporter function (see section below), such enrichment was less evident among the GPC-B2-regulated genes. Instead, this class was enriched for genes with putative roles in plant cell wall biogenesis, microtubule organization and other processes distinct from those found in the senescence-regulated genes.

These results are consistent with the stronger effect of gpc-A1 knockout mutants on senescence and nutrient translocation profiles in the current study (Figure 1, a-d) and with the strong effect seen on these phenotypes in gpc1-null mutants in hexaploid wheat [46]. One caveat of this comparison is that while the gpc-A1 mutation in the tetraploid variety ‘Kronos’ represents a true gpc1-null allele (because of the natural non-functional mutation in GPC-B1 in this variety), the gpc-B2 mutant likely alters the dosage of GPC2 but does not result in a gpc2-null mutant (because of the presence of an intact and expressed copy of GPC-A2). No gpc-A2 truncation mutant was found in our current tetraploid TILLING population, but we are currently transferring a gpc-A2 premature stop codon mutant found in our hexaploid wheat TILLING population [50] into Kronos. The lack of a gpc-A2 truncation mutant in this study does not affect the interpretation of the GPC-B2 regulated genes, but may have resulted in an underestimation of the number of genes regulated by GPC2.

Despite the high sequence similarity of GPC1 and GPC2 and their common expression profiles in the wheat flag leaf during monocarpic senescence, these genes appear to have diverged to regulate different sets of downstream targets. The closest rice ortholog to the wheat GPC genes is Os07g37920 which maps to a region of the genome collinear to GPC2 [51]. This suggests that GPC2 is the ancestral gene and that GPC1 originated from a duplication event specific to the wheat lineage [51]. However, the downregulation of Os07g37920 by RNAi, or its overexpression in transgenic rice plants, did not affect the rate of senescence. The only difference observed in Os07g37920-RNAi rice plants was male sterility caused by the inability of the anther to dehisce and release pollen [51]. These results suggest that the specialization of GPC1 on the regulation of transporters during senescence, and its stronger effect on the rate of senescence, are likely derived characteristics acquired by GPC1 after its duplication to its non-orthologous location on the short arm of homoeologous group 6 chromosomes.

A recent study showed that the rice gene OsNAP, a close paralogue of Os07g37920 and of wheat GPC1, has a strong effect on senescence ([52], PNAS 111: 10013–10018).

In summary, the results described in this section indicate that the GPC genes regulate a subset of senescence-regulated genes that are mainly upregulated during the early stages of monocarpic senescence (first 12 DAA). Although most GPC-regulated genes are affected by both paralogs, GPC1 seems to play a stronger role than GPC2 in the regulation of a subset of genes involved in senescence that includes enrichment for transporter gene function. However, in the absence of a complete knockout of GPC2, we cannot fully determine the role of GPC2 in monocarpic senescence. The importance of GPC1 in the regulation of senescence is highlighted by the finding that among the 1,298 genes upregulated in the WT between HD and 12 DAA 1,054 were not upregulated in the gpc-A1 mutant.

Effect of GPC genes on previously characterized genes involved in transport

To complement the top-down analyses discussed above, we also characterized the effect of GPC and senescence on the expression of nine gene families previously shown to play important roles in nutrient remobilization in other plant species. The discussion of these genes is organized according to their involvement in different transport processes.

Chloroplast to cytoplasm

Our results demonstrate that the early stages of monocarpic senescence in the flag leaf are associated with a large-scale downregulation of genes involved in photosynthetic processes (Table 1). Therefore, the downregulation of TaFRO1, which is likely involved in the import of Fe into the chloroplast is not surprising. Studies in model species have demonstrated that some members of the FRO family localize to the chloroplast membrane and act in the reduction-based import of nutrients into the chloroplast [9,10]. In rice, OsFRO1 transcript levels are negatively correlated with Zn and Fe levels in the rice grain [53].

By contrast, we observed a significant upregulation of two wheat members of the HMA transporter family during senescence which have been implicated in Zn and Fe export from the chloroplast to the cytoplasm [12]. The expression of one of these genes, TaHMA2-like, was also significantly higher in WT plants than either gpc-A1 or gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutants, which may contribute to the reduced efficiency in Zn and Fe remobilization observed in these mutants. The rice ortholog of this gene, OsHMA2, was shown to play an important role in facilitating Zn transport to the rice panicle [54]. These results suggest that nutrient remobilization from the chloroplasts to the cytoplasm for future export to the grain is an early step in wheat monocarpic senescence.

Vacuole to cytoplasm transport

Another sink for Zn and Fe during vegetative development is the vacuole, which is utilized as a storage body to prevent plant cell toxicity associated with excess concentrations of these nutrients. In other plant species, VIT and ZIFL transporters have been shown to facilitate nutrient import into the vacuole, while NRAMP transporters have been implicated in Fe export from the vacuole to the cytoplasm. In our study, the expression of both identified wheat VIT genes fell during monocarpic senescence, with TaVIT2 showing a ~4-fold reduction between HD and 22 DAA. However, these differences were not significant for all four statistical tests and were excluded from our DE list. In rice, both OsVIT1 and OsVIT2 proteins localize to the tonoplast and can transport Zn2+ and Fe2+ across this membrane as part of a vacuolar sequestration strategy [13]. Mutants with reduced or abolished function of both these genes exhibit reduced Zn and Fe concentrations in the leaves coupled with increased levels in the grains, suggesting that a downregulation of these genes during senescence contributes to increased rates of Zn and Fe translocation [13,55].

The ZIFL family of transporters is also thought to function in the vacuole. One such transporter in Arabidopsis was implicated in Zn sequestration to the vacuole in vegetative tissues [14], while in barley, a ZIFL-like gene is expressed in the aleurone layer of seeds and is induced in the embryo upon foliar Zn application and has been implicated in the regulation of Zn transport to the grain [56]. These potentially distinct roles of the different ZIFL genes may explain the differences in transcription profiles observed in this study. TaZIFL1 was significantly downregulated during senescence, whereas TaZIFL2-like1 and TaZIFL7 were significantly upregulated. The rice orthologs of these genes (OsZIFL2 and OsZIFL7) are both upregulated in flag leaves during senescence suggesting that they may promote Zn remobilization during senescence [15]. OsZIFL1 expression was not detected in rice flag leaves at any stage of development. Further studies will be required to better characterize the function of ZIFL transporters in wheat.

None of the eight NRAMP genes identified in wheat were DE between WT and gpc mutants and only one (TaNRAMP2) was significantly upregulated during senescence (Table 2). This upregulation during senescence is consistent with the known function of this class of transporters, which are thought to facilitate Fe export from the vacuole when remobilization is required during development [57]. However, our finding that most of the wheat NRAMP genes were not DE during wheat senescence suggests that these transporters may act in other tissues or stages of developmental stages.

In summary, among the genes involved in the transport for Fe and Zn to and from the vacuole only TaZIFL7 was DE in both gpc mutant genotypes, suggesting a limited effect of the GPC genes in the regulation of this group of genes. However, it will still be interesting to investigate the role of TaZIFL7 and of the other three genes from this group which are DE during senescence.

Cytoplasm to phloem transport

For their transport to the grain, nutrients must cross the plasma membrane into the phloem. Members of the YSL and ZIP families are known to play important roles in the transport of metal-chelate complexes across the plasma membrane in several plant species (Curie et al. 2009) [19]. In wheat, we identified and characterized 14 and 19 members of the YSL (Additional file 1: Figure S8) and ZIP (Additional file 1: Figure S9) families, respectively. Two of the wheat YSL genes were upregulated during senescence and one was downregulated, suggesting that they performed different functions (Table 2). However, there is still little evidence from the literature regarding YSL function in vegetative Zn and Fe transport, so further experiments will be required to define their role in wheat.

A much clearer link between GPC1 and Zn and Fe transport during monocarpic senescence was observed for members of the ZIP gene family. A total of five TaZIP genes were upregulated during senescence and the expression of all five plus TaZIP5 and TaZIP10 was significantly higher in WT plants than in either gpc-A1 or gpc-A1/gpc-B2 mutant genotypes. TaIRT-like2 was also DE, but only between WT and the gpc-A1/gpc-B2 double mutant (Table 2). In some cases, the effect was very large; for example, the expression of both TaZIP3 and TaZIP5 were more than 15-fold higher in WT plants than either of the gpc mutant genotypes at 22 DAA. These results demonstrate that GPC plays a critical role in the regulation of multiple members of this family and that ZIP expression is likely to be associated with the remobilization of Zn and Fe from leaves to grain in wheat. A recent study in barley demonstrated that the over-expression of HvZIP7 resulted in increased Zn accumulation in the grain [21]. The corresponding wheat homologue, TaZIP7, was also significantly upregulated by GPC during senescence in the current study, suggesting a conserved role for this transporter. For future biotechnological applications, it will be important to determine which of these ZIP transporters represents a limiting step in the remobilization of Zn and Fe from leaves to the grain.

PS biosynthesis

It has been hypothesized that a critical limiting factor for nutrient transport to the grain is their solubility in the alkaline environment of the phloem [30]. To prevent precipitation, Fe and Zn ions are transported as a complex with organic ligands or chelators, one critical class of which is the mugineic acid family of PS (Figure 1). We show in this study that several wheat genes encoding key biosynthetic enzymes of this pathway are upregulated during senescence and are differentially regulated by the GPC genes. A significant upregulation in TaNAAT2 expression between HD and 12 DAA and an increase in TaNAS3 between 12 DAA and 22 DAA suggest an active and possibly coordinated role of these genes during wheat monocarpic senescence. Both TaNAAT genes were DE in at least one gpc mutant genotype (Table 2) suggesting that they might contribute to the reduced concentrations of Fe and Zn observed in the grains of the gpc mutant plants. No significant differences were detected for TaDMAS1.

In the rice phloem, Fe and Zn can associate with both NA and DMA, although Zn-NA and Fe-DMA complexes have been shown to be more common [28,29]. NAS overexpression has been shown to result in dramatic increases in both Zn and Fe grain content in rice [33,34], making the orthologous genes in wheat interesting targets for biofortification strategies. Multiple transgenic strategies have been successfully applied in rice to increase micronutrient levels in the grain [58], although to date, such strategies have not been described in wheat. The characterization of the different transporter gene families during wheat monocarpic senescence provides the basic information required to select targets for similar biotechnological approaches in this economically important crop species.

In addition to these well-characterized transporter families, we also identified 22 other transporter-related genes which were upregulated between HD and 12 DAA in WT plants, but not in gpc-A1 mutants (Additional file 1: Table S5). Among these genes, we found one differentially regulated potassium transporter and two sulfate transporters, which are potentially related to the differences identified in K and S concentrations in the grain between genotypes (Additional file 1: Table S1). A similar increase in K and decrease in S, Zn and Fe concentration was also observed in the grains of GPC-RNAi transgenic plants with reduced transcriptional levels of all GPC genes [5,59]. It will be interesting to investigate whether there is a functional connection between the DE of Fe, Zn, S and K transporters and the effect of the GPC genes on their concentration, in the wheat grain.

Conclusions

In summary, this study confirms that GPC1 plays a strong role in the regulation of wheat monocarpic senescence, and that it is involved in the upregulation of a large number of genes during the early stages of wheat monocarpic senescence. These genes are likely involved in the plant’s active preparation for the upcoming senescence. Supporting this hypothesis, we found several transporters and genes involved in the biosynthesis of chelators that facilitate Zn and Fe transport through the phloem that were differentially regulated by the GPC genes. Among these transporters, members of the large ZIP gene family appear to be interesting targets for biotechnological applications and for screening of different natural alleles to improve nutrient remobilization.

Methods

Plant material

We previously identified individuals in our tetraploid Kronos TILLING population which carry mutations introducing premature stop codons in GPC-A1 (W114*, henceforth gpc-A1) and GPC-B2 (W109*, henceforth gpc-B2) [51]. Since WT Kronos carries a single nucleotide insertion in the coding region of GPC-B1 that results in a non-functional protein [44], the gpc-A1 mutant carries no functional GPC1 genes.