Abstract

As part of the Choosing Wisely Campaign, the Society of Hospital Medicine identified reducing inappropriate use of acid-suppressive medication for stress ulcer prophylaxis as one of 5 key opportunities to improve the value of care for hospitalized patients. We designed a computerized clinical decision support intervention to reduce use of acid-suppressive medication for stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients outside of the intensive care unit at an academic medical center. Using quasi-experimental interrupted time series analysis, we found that the decision support intervention resulted in a significant reduction in use of acid-suppressive medication with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication, a non-significant reduction in overall use, and no change in use on discharge. We found low rates of use of acid-suppressive medication for the purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis even before the intervention, and continuing preadmission medication was the most commonly selected indication throughout the study. Our results suggest that attention should be focused on both the inpatient and outpatient settings when designing future initiatives to improve the appropriateness of acid-suppressive medication use.

Keywords: Acid-suppressive medication, computerized decision support, quasi-experimental study design

Introduction

Prior studies have found that up to 70% of acid-suppressive medication (ASM) use in the hospital is not indicated, most commonly for stress ulcer prophylaxis in patients outside of the intensive care unit (ICU).1–7 Accordingly, reducing inappropriate use of ASM for stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients is one of the 5 opportunities for improved healthcare value identified by the Society of Hospital Medicine as part of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely campaign.8

We designed and tested a computerized clinical decision support (CDS) intervention with the goal of reducing use of ASM for stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients outside the intensive care unit at an academic medical center.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a quasi-experimental study using an interrupted time series to analyze data collected prospectively during clinical care before and after implementation of our intervention. The study was deemed a quality improvement initiative by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations/Institutional Review Board.

Patients and Setting

All admissions > 18 years of age to a 649 bed academic medical center in Boston, MA from 9/12/2011 through 7/3/2012 were included. The medical center consists of an East and West Campus, located across the street from one another. Care for both critically ill and non-critically ill medical and surgical patients occurs on both campuses. Differences include greater proportions of patients with gastrointestinal and oncologic conditions on the East Campus, and renal and cardiac conditions on the West Campus. Additionally, labor and delivery occurs exclusively on the East Campus, and the density of ICU beds is greater on the West Campus. Both campuses utilize a computer-based Provider Order Entry (POE) system.

Intervention

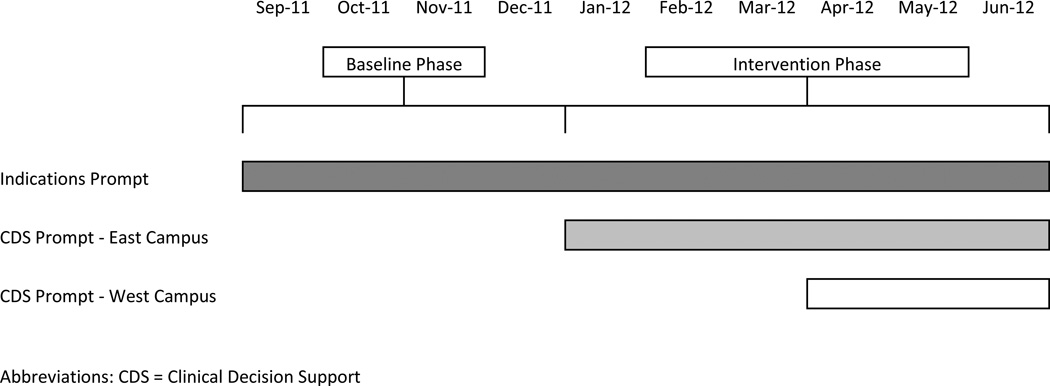

Our study was implemented in 2 phases (Figure1):

Baseline phase: The purpose of the first phase was to obtain baseline data on ASM use prior to implementing our CDS tool designed to influence prescribing. During this baseline phase, a computerized prompt was activated through our POE system whenever a clinician initiated an order for ASM (histamine-2 receptor antagonists or proton-pump inhibitors), asking the clinician to select the reason/reasons for the order based on the following predefined response options: 1) Active/recent upper gastrointestinal bleed, 2) Continuing preadmission medication, 3) H. Pylori treatment, 4) Prophylaxis in patient on medications that increase bleeding risk, 5) Stress ulcer prophylaxis, 6) Suspected/known peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, esophagitis, GERD, and 7) Other, with a free text box to input the indication. This “indications prompt” was rolled out to the entire medical center on 9/12/2011 and remained active for the duration of the study period.

Intervention phase: In the second phase of the study, if a clinician selected “stress ulcer prophylaxis” as the only indication for ordering ASM, a CDS prompt alerted the clinician that “Stress ulcer prophylaxis is not recommended for patients outside of the intensive care unit (ASHP Therapeutic Guidelines on Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1999, 56:347-79).” The clinician could then select either, “For use in ICU – Order Medication,” “Choose Other Indication,” or “Cancel Order.” This CDS prompt was rolled out in a staggered manner to the East Campus on 1/3/12, followed by the West Campus on 4/3/12.

Figure 1.

Study Timeline

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the rate of ASM use with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication in a patient located outside of the ICU. We confirmed patient location in the 24 hours after the order was placed. Secondary outcomes were rates of overall ASM use, defined via pharmacy charges, and rates of use on discharge.

Statistical Analysis

To assure stable measurement of trends, we studied at least 3 months before and after the intervention on each campus. We used Fisher’s Exact test to compare the rates of our primary and secondary outcomes before and after the intervention, stratified by campus. For our primary outcome – at least one ASM order with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication during hospitalization – we developed a logistic regression model with a generalized estimating equation and exchangeable working correlation structure to control for admission characteristics (Table 1) and repeated admissions. Using a term for the interaction between time and the intervention, this model allowed us to assess changes in level and trend for the odds of a patient receiving at least one ASM order with stress ulcer prophylaxis as the only indication before, compared to after the intervention, stratified by campus. We used a 2-sided type-I error of < 0.05 to indicate statistical significance.

Table 1.

Admission Characteristics (n = 26,400 admissions)

| Campus | East | West | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Phase | Baseline | Intervention | Baseline | Intervention |

| (n=3,747) | (n=6,191) | (n=11,177) | (n=5,285) | |

| Age – Mean (s.d.) | 48.1 (18.5) | 47.7 (18.2) | 61.0 (18.0) | 60.3 (18.1) |

| Gender – n (%) | ||||

| Female | 2744 (73.2%) | 4542 (73.4%) | 5551 (49.7%) | 2653 (50.2%) |

| Male | 1003 (26.8%) | 1649 (26.6%) | 5626 (50.3%) | 2632 (49.8%) |

| Race – n (%) | ||||

| Asian | 281 (7.5%) | 516 (8.3%) | 302 (2.7%) | 156 (3%) |

| Black | 424 (11.3%) | 667 (10.8%) | 1426 (12.8%) | 685 (13%) |

| Hispanic | 224 (6%) | 380 (6.1%) | 619 (5.5%) | 282 (5.3%) |

| Other | 378 (10.1%) | 738 (11.9%) | 776 (6.9%) | 396 (7.5%) |

| White | 2440 (65.1%) | 3890 (62.8%) | 8054 (72%) | 3766 (71.3%) |

| Charlson Score – Mean (s.d.) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.7 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.4) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding* | 49 (1.3%) | 99 (1.6%) | 385 (3.4%) | 149 (2.8%) |

| Other Medication Exposures† | ||||

| Therapeutic Anticoagulant | 218(5.8%) | 409(6.6%) | 2242(20.1%) | 1022(19.3%) |

| Prophylactic Anticoagulant | 1081 (28.8%) | 1682 (27.2%) | 5999 (53.7%) | 2892 (54.7%) |

| NSAID | 1899 (50.7%) | 3141 (50.7%) | 1248 (11.2%) | 575 (10.9%) |

| Antiplatelet | 313 (8.4%) | 585 (9.4%) | 4543 (40.6%) | 2071 (39.2%) |

| Admitting Department | ||||

| Surgery‡ | 2507 (66.9%) | 4146 (67%) | 3255 (29.1%) | 1578 (29.9%) |

| Non-Surgery | 1240 (33.1%) | 2045 (33%) | 7922 (70.9%) | 3707 (70.1%) |

| Any ICU Stay | 217 (5.8%) | 383 (6.2%) | 2786 (24.9%) | 1252 (23.7%) |

Abbreviations: s.d. = standard deviation; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; ICU = intensive care unit.

Defined as any discharge diagnosis code for gastrointestinal bleeding using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Clinical Classifications Software.12

Therapeutic Anticoagulants defined as coumarin derivatives or direct factor XA inhibitors or direct thrombin inhibitors or thrombolytic agents or enoxaparin > 40 mg per day or heparin > 15,000 units per day. Prophylactic anticoagulation defined as enoxaparin ≤ 40 mg per day or heparin ≤ 15,000 units per day. NSAIDS defined as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents or cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors. Antiplatelet agents defined as platelet-aggregation inhibitors or salicylates.

Surgery includes labor and delivery.

Results

There were 26,400 adult admissions during the study period, and 22,330 discrete orders for ASM. Overall, 12,056 (46%) admissions had at least 1 charge for ASM. Admission characteristics were similar before and after the intervention on each campus (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the indications chosen each time ASM was ordered, stratified by campus and study phase. While selection of “stress ulcer prophylaxis” decreased on both campuses during the intervention phase, selection of “continuing preadmission medication” increased.

Table 2.

Indications Chosen at the Time of Acid-Suppressive Medication Order Entry (n = 22,330 orders).

| Campus | East | West | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Phase | Baseline n=2,062 |

Intervention n=3,243 |

Baseline n=12,038 |

Intervention n=4,987 |

| Indication* | ||||

| Continuing Preadmission Medication | 910 (44.1%) | 1695 (52.3%) | 5597 (46.5%) | 2802 (56.2%) |

| PUD, Gastritis, Esophagitis, GERD | 440 (21.3%) | 797 (24.6%) | 1303 (10.8%) | 582 (11.7%) |

| Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis | 298 (14.4%) | 100 (3.1%) | 2659 (22.1%) | 681 (13.7%) |

| Prophylaxis in Patient on Medications that Increase Bleeding Risk | 226 (11.0%) | 259 (8.0%) | 965 (8.0%) | 411 (8.2%) |

| Active/Recent Gastrointestinal Bleed | 154 (7.5%) | 321 (9.9%) | 1450 (12.0%) | 515 (10.3) |

| H. Pylori Treatment | 6 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) | 43 (0.4%) | 21 (0.4%) |

| Other | 111 (5.4%) | 156 (4.8%) | 384 (3.2%) | 186 (3.7%) |

Abbreviations: PUD = peptic ulcer disease; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Indications may sum to greater than 100% since more than 1 indication could be selected for each order.

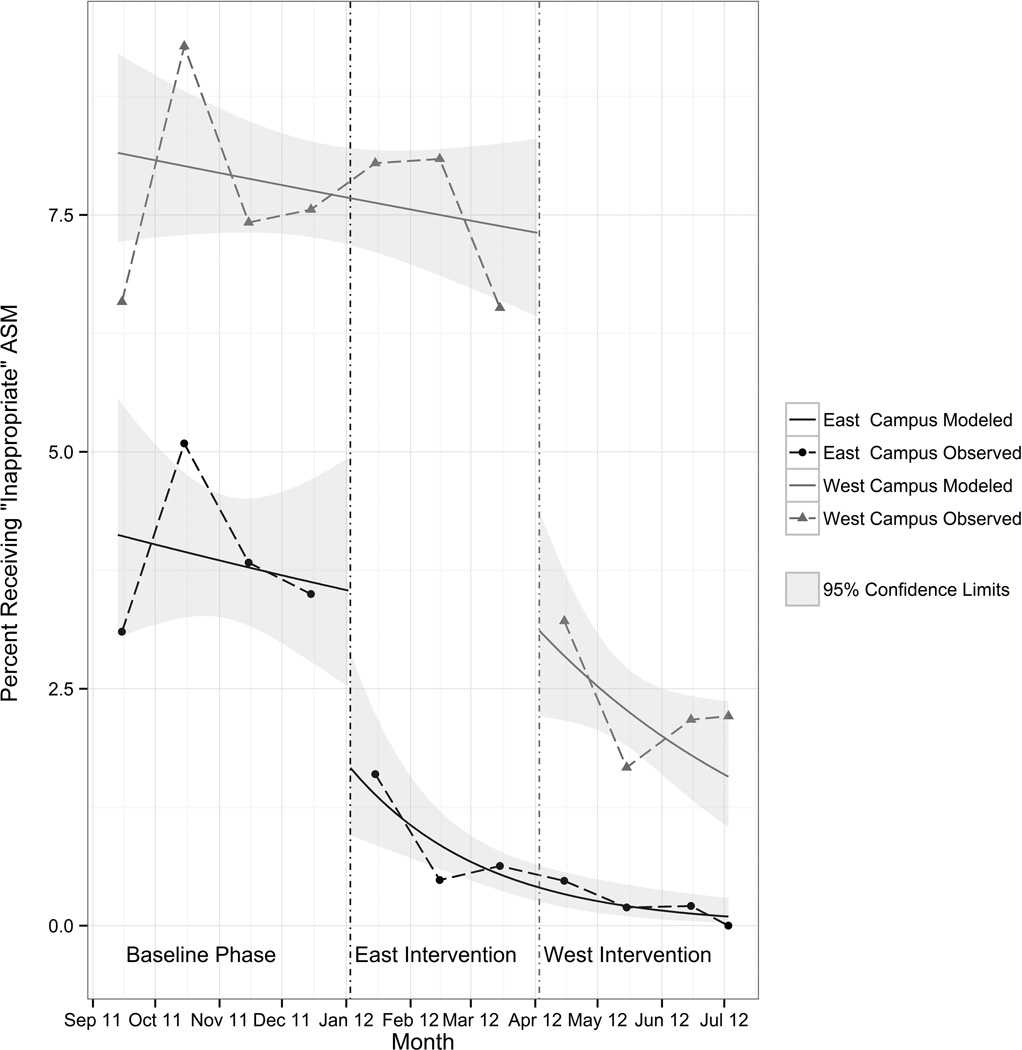

Table 3 shows the unadjusted comparison of outcomes between baseline and intervention phases on each campus. Use of ASM with stress ulcer prophylaxis as the only indication decreased during the intervention phase on both campuses. There was a non-significant reduction in overall rates of use on both campuses, and use on discharge was unchanged. Figure 2 demonstrates the unadjusted and modeled monthly rates of admissions with at least one ASM order with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication, stratified by campus. After adjusting for the admission characteristics in Table 1, during the intervention phase on both campuses there was a significant immediate reduction in the odds of receiving an ASM with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication (East Campus OR 0.36, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.18 – 0.71; West Campus OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.28-0.60), and a significant change in trend compared to the baseline phase (East Campus 1.5% daily decrease in odds of receiving ASM solely for stress ulcer prophylaxis, p = 0.002; West Campus 0.9% daily decrease in odds of receiving ASM solely for stress ulcer prophylaxis, p = 0.02).

Table 3.

Unadjusted rates of primary and secondary outcomes

| Campus | East | West | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Phase | Baseline (n=3,747) |

Intervention (n=6,191) |

p-value* | Baseline (n=11,177) |

Intervention (n=5,285) |

p-value* |

| Outcome | ||||||

| Any “inappropriate” acid-suppressive exposure† | 4.0% | 0.6% | <0.001 | 7.7% | 2.2% | <0.001 |

| Any acid-suppressive exposure | 33.1% | 31.8% | 0.16 | 54.5% | 52.9% | 0.05 |

| Discharged on acid-suppressive medication | 18.9% | 19.6% | 0.40 | 34.7% | 34.7% | 0.95 |

Fisher’s Exact test

Defined as an admission with at least 1order for acid-suppressive medication with stress ulcer prophylaxis as the only recorded indication in a patient located outside of the ICU.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted and modeled monthly rates of “inappropriate” ASM orders, stratified by campus. We used a logistic regression model with a generalized estimating equation to control for admission characteristics (Table 1) and repeated admissions, including a term for the interaction between time and the intervention. We defined “inappropriate” ASM orders as any order for ASM with stress ulcer prophylaxis as the only recorded indication in a patient located outside of the ICU. ASM = acid-suppressive medication.

Discussion

In this single-center study we found that a computerized CDS intervention resulted in a significant reduction in use of ASM for the sole purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis in patients outside the ICU, a non-significant reduction in overall use, and no change in use on discharge. We found low rates of use for the isolated purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis even before the intervention, and continuing preadmission medication was the most commonly selected indication throughout the study.

Although overall rates of ASM use declined after the intervention, the change was not statistically significant, and was not of the same magnitude as the decline in rates of use for the purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis. This suggests that our intervention, in part, led to substitution of one indication for another. The indication that increased the most after rollout on both campuses was “continuing preadmission medication.” There are at least 2 possibilities for this finding: 1) the intervention prompted physicians to more accurately record the indication, or 2) physicians falsified the indication in order to execute the order. To explore these possibilities, we reviewed the charts of a random sample of 100 admissions during each of the baseline and intervention phases where “continuing preadmission medication” was selected as an indication for an ASM order. We found that 6/100 orders in the baseline phase and 7/100 orders in the intervention phase incorrectly indicated that the patient was on ASM prior to admission (p=0.77). This suggests that scenario 1 above is the more likely explanation for the increased use of this indication, and that the intervention, in part, simply unmasked the true rate of use at our medical center for the isolated purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis.

These findings have implications for others attempting to use computerized CDS to better understand physician prescribing. They suggest that information collected through computer-based interaction with clinicians at the point of care may not always be accurate or complete. As institutions increasingly use similar interventions to drive behavior, information obtained from such interaction should be validated, and, when possible, patient outcomes should be measured.

Our findings suggest that rates of ASM use for the purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis in the hospital may have declined over the last decade. Studies demonstrating that up to 70% of inpatient use of ASM was inappropriate were conducted 5–10 years ago.1–5 Since then, studies have demonstrated risk of nosocomial infections in patients on ASM.9–11 It is possible that the low rate of use for stress ulcer prophylaxis in our study is attributable to awareness of the risks of these medications, and limited our ability to detect differences in overall use. It is also possible, however, that a portion of the admissions with continuation of preadmission medication as the indication were started on these medications during a prior hospitalization. Thus, some portion of preadmission use is likely to represent failed medication reconciliation during a prior discharge. In this context, hospitalization may serve as an opportunity to evaluate the indication for ASM use even when these medications show up as preadmission medications.

There are additional limitations. First, the single center nature limits generalizability. Second, the first phase of our study, designed to obtain baseline data on ASM use, may have led to changes in prescribing prior to implementation of our CDS tool. Additionally, we did not validate the accuracy of each of the chosen indications, or the site of initial prescription in the case of preadmission exposure. Lastly, our study was not powered to investigate changes in rates of nosocomial gastrointestinal bleeding or nosocomial pneumonia owing to the infrequent nature of these complications.

In conclusion, we designed a simple computerized CDS intervention which was associated with a reduction in ASM use for stress ulcer prophylaxis in patients outside the ICU, a non-significant reduction in overall use, and no change in use on discharge. The majority of inpatient use represented continuation of preadmission medication, suggesting that interventions to improve the appropriateness of ASM prescribing should span the continuum of care. Future studies should investigate whether it is worthwhile and appropriate to re-evaluate continued use of preadmission ASM during an inpatient stay.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Joshua Guthermann, M.B.A. and Jane Hui Chen Lim, M.B.A. for their assistance in the early phases of data analysis, and Long H. Ngo, Ph.D., for his statistical consultation.

Financial support: Dr. Herzig was funded by a Young Clinician Research Award from the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology, a non-profit consortium of Boston teaching hospitals and universities, and grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Marcantonio was funded by grant number K24AG035075 from the National Institute on Aging. The funding organizations had no involvement in any aspect of the study, including design, conduct, and reporting of the study.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions: Dr. Herzig had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Herzig, Marcantonio.

Acquisition of data: Herzig, Feinbloom, Adra, Afonso, Howell.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Herzig, Guess, Howell, Marcantonio.

Drafting of the manuscript: Herzig.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Herzig, Guess, Feinbloom, Adra, Afonso, Howell, Marcantonio.

Study Supervision: Herzig, Marcantonio.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grube RR, May DB. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients not in intensive care units. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007 Jul 1;64(13):1396–1400. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidelbaugh JJ, Inadomi JM. Magnitude and economic impact of inappropriate use of stress ulcer prophylaxis in non-ICU hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 Oct;101(10):2200–2205. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janicki T, Stewart S. Stress-ulcer prophylaxis for general medical patients: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2007 Mar;2(2):86–92. doi: 10.1002/jhm.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parente F, Cucino C, Gallus S, et al. Hospital use of acid-suppressive medications and its fall-out on prescribing in general practice: a 1-month survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003 Jun 15;17(12):1503–1506. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scagliarini R, Magnani E, Pratico A, Bocchini R, Sambo P, Pazzi P. Inadequate use of acid-suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients and its implications for general practice. Dig Dis Sci. 2005 Dec;50(12):2307–2311. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-3052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liberman JD, Whelan CT. Brief report: Reducing inappropriate usage of stress ulcer prophylaxis among internal medicine residents. A practice-based educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 May;21(5):498–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wohlt PD, Hansen LA, Fish JT. Inappropriate continuation of stress ulcer prophylactic therapy after discharge. Ann Pharmacother. 2007 Oct;41(10):1611–1616. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013 Sep;8(9):486–492. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dial S, Alrasadi K, Manoukian C, Huang A, Menzies D. Risk of Clostridium difficile diarrhea among hospital inpatients prescribed proton pump inhibitors: cohort and case-control studies. Cmaj. 2004 Jul 6;171(1):33–38. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howell MD, Novack V, Grgurich P, et al. Iatrogenic gastric acid suppression and the risk of nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection. Arch Intern Med. May 10;170(9):784–790. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herzig SJ, Howell MD, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia. Jama. 2009 May 27;301(20):2120–2128. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project: Clinical Classification Software. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2009. Dec, [Accessed June 18, 2014]. Available at: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. [Google Scholar]