Abstract

The transcription factor p63 (Trp63) plays a key role in homeostasis and regeneration of the skin. The p63 gene is transcribed from dual promoters, generating TAp63 isoforms with growth suppressive functions and dominant-negative ΔNp63 isoforms with opposing properties. p63 also encodes multiple carboxy (C)-terminal variants. Although mutations of C-terminal variants have been linked to the pathogenesis of p63-associated ectodermal disorders, the physiological role of the p63 C-terminus is poorly understood. We report here that deletion of the p63 C-terminus in mice leads to ectodermal malformation and hypoplasia, accompanied by a reduced proliferative capacity of epidermal progenitor cells. Notably, unlike the p63-null condition, we find that p63 C-terminus deficiency promotes expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21Waf1/Cip1 (Cdkn1a), a factor associated with reduced proliferative capacity of both hematopoietic and neuronal stem cells. These data suggest that the p63 C-terminus plays a key role in the cell cycle progression required to maintain the proliferative potential of stem cells of many different lineages. Mechanistically, we show that loss of Cα, the predominant C-terminal p63 variant in epithelia, promotes the transcriptional activity of TAp63 and also impairs the dominant-negative activity of ΔNp63, thereby controlling p21Waf1/Cip1 expression. We propose that the p63 C-terminus links cell cycle control and the proliferative potential of epidermal progenitor cells via mechanisms that equilibrate TAp63 and ΔNp63 isoform function.

Keywords: Cell cycle, Epithelia, Mouse, p21, p63, Proliferation, Stem cells

Summary: In the mouse skin, the C-terminus of p63 regulates the expression of p21Waf1/Cip, a cylin independent kinase inhibitor, to maintain stem cell proliferation.

INTRODUCTION

Adult stem cells are capable of long-term self-renewal and differentiation, enabling their use as an important therapeutic approach in regenerative medicine (Green, 2008; Pellegrini et al., 2009; Rama et al., 2010). Epidermal stem cells are essential for maintaining homeostasis and regeneration of the skin, but the specific mechanisms that control their fate are not well understood (Bickenbach et al., 2006; Blanpain and Fuchs, 2009; Ghadially, 2012; Kaur, 2006; Watt and Jensen, 2009). We previously identified p63 (Trp63), a homolog of the tumor suppressor p53 (Trp53) (Osada et al., 1998; Schmale and Bamberger, 1997; Senoo et al., 1998; Trink et al., 1998; Yang et al., 1998), and showed that p63 deficiency leads to a loss of proliferative potential of epidermal stem cells (Senoo et al., 2007). Indeed, p63-null mice display severe defects in epithelial development (Mills et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999). Genetic studies suggest that mutations in p63 contribute to the pathogenesis of a wide range of ectodermal dysplasias (EDs), characterized by ectodermal malformations and hypoplasias (Celli et al., 1999; Koster, 2010; Rinne et al., 2007; van Bokhoven and McKeon, 2002), and we have recently noted decreased p63 expression in chronic equine laminitis in which the proliferative epidermal layers appear dysplastic (Carter et al., 2011). Thus, it is clear that p63 plays a key role in both the normal physiology and pathophysiology of the epidermis.

The p63 gene is transcribed from dual promoters, generating TAp63 isoforms that contain a transactivation domain with growth suppressive functions (Guo et al., 2009) and dominant-negative ΔNp63 isoforms that lack this domain and exhibit opposing oncogenic properties (Keyes et al., 2011). Studies on isoform-specific knockout (KO) mice revealed that loss of ΔNp63 leads to the identical epidermal hypoplasia observed in p63-null mice (Romano et al., 2012). As ΔNp63 is the predominant isoform expressed in epidermal progenitor cells, including stem cells and transit-amplifying cells, ΔNp63 appears to play the major role in maintaining the proliferative potential of epidermal progenitors (Senoo, 2013). However, ΔNp63-specific KO mice also show an early onset of terminal differentiation (Romano et al., 2012) that is not observed in p63-null mice, suggesting that ΔNp63 normally counterbalances TAp63-driven differentiation and the consequent reduction in proliferative potential of epidermal stem cells. Notably, although TAp63-specific KO mice show grossly normal epidermal development, their isolated epidermal progenitor cells show reduced proliferative capacity in vitro (Su et al., 2009). These results suggest that TAp63 opposes ΔNp63 function, thereby preventing a premature reduction in proliferative potential. Thus, it is likely that p63 function reflects a cooperative effect between TAp63 and ΔNp63 isoforms (Candi et al., 2006; Truong et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2014).

Whereas the amino (N)-terminal functions of p63 are relatively well studied, carboxy (C)-terminal functions in vivo are poorly understood. By alternative splicing, the p63 gene generates at least three C-terminus variants, termed Cα, Cβ and Cγ, for both the TAp63 and ΔNp63 isoforms (Yang et al., 1998). Notably, Cα uniquely harbors the sterile α-motif (SAM) domain (p63SAM), which is a protein-protein interaction domain (Qiao and Bowie, 2005; Thanos and Bowie, 1999), and the transcription inhibitory (TI) domain (p63TI) (Serber et al., 2002). The significance of Cα is evident from genetic studies of p63-associated EDs, showing that mutations in either the p63SAM or p63TI domain or a complete absence of Cα/β but not Cγ cause ankyloblepharon-ectodermal defects-cleft lip/palate (AEC) syndrome, ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-clefting (EEC) syndrome and limb-mammary syndrome (LMS) (Barrow et al., 2002; Celli et al., 1999; Rinne et al., 2009; van Bokhoven et al., 2001). A recent study has shown that a point mutation in the p63SAM domain reduces the number of epidermal progenitor cells (Ferone et al., 2012), highlighting the significance of Cα in regulating stem cell properties. However, how Cα exerts its function and the relative contribution of Cα in TAp63 and ΔNp63 isoform functions remain largely unknown.

A precise coupling between cell proliferation and differentiation is required during embryonic development and self-renewal of adult tissues. The cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21Waf1/Cip1 (Cdkn1a) belongs to the Cip/Kip family of CDK inhibitors and was originally identified as a mediator of p53-induced growth arrest (El-Deiry et al., 1993; Harper et al., 1993). However, induction of p21Waf1/Cip1 in epidermal progenitor cells is independent of p53 function (Missero et al., 1995), indicating that alternative regulatory mechanisms are involved in this cell type. Indeed, accumulating evidence suggests that p63 can control p21Waf1/Cip1 expression (Guo et al., 2009; Su et al., 2013; Truong et al., 2006; Westfall et al., 2003) and, notably, p21Waf1/Cip1 itself acts as a negative regulator of the proliferative potential of epidermal progenitor cells (Topley et al., 1999). However, whether p63 regulates p21Waf1/Cip1 expression in vivo to influence the proliferative potential of epidermal progenitor cells remains unknown.

To further investigate the global function of the p63SAM and p63TI domains, we have generated mutant mice lacking Cα/β by gene targeting and found that homozygous mutant (referred to here as p63C−/−) mice show multiple phenotypes including ectodermal hypoplasia, limb malformation and orofacial clefting. We further demonstrate that mice with p63 C-terminus deficiency show reduced cell cycle progression and enhanced p21Waf1/Cip1 expression in epidermal progenitor cells, leading to their decreased proliferative capacity. Although the function of p63 is complex owing to the existence of multiple isoforms as well as inter- and intramolecular interactions, our present study shows that loss of Cα both promotes transcriptional activity of TAp63 and reduces the dominant-negative activity of ΔNp63 in the control of p21Waf1/Cip1 expression. Based on these data, we propose that p63 links cell cycle control and proliferative potential of epidermal progenitor cells through C-terminus-dependent mechanisms that balance TAp63 and ΔNp63 isoform functions.

RESULTS

Generation of mice lacking the C-terminus of p63

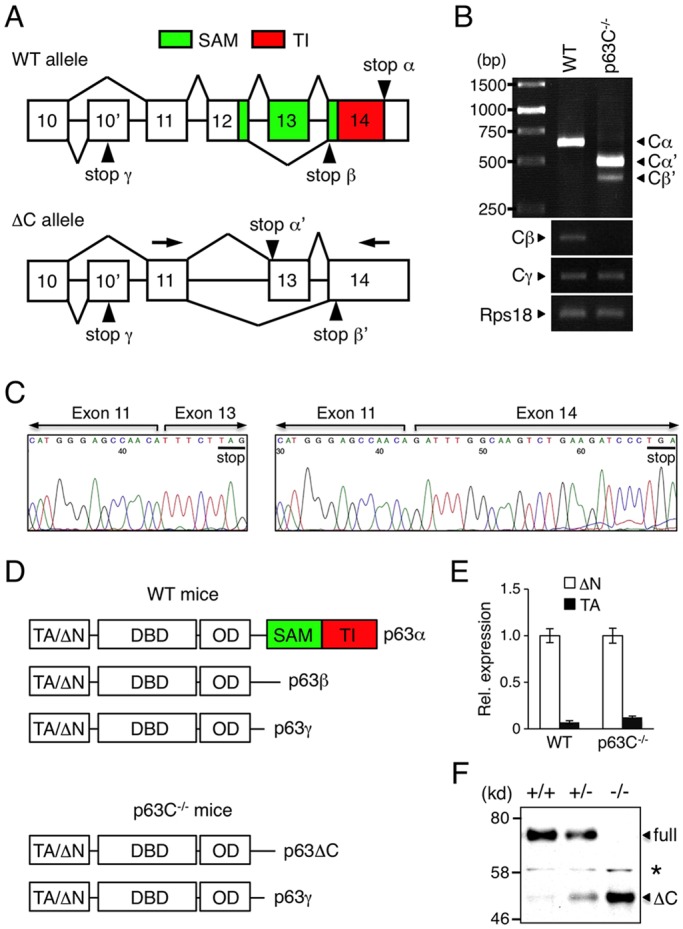

The SAM and TI domains of p63 are encoded by exons 12-14 of the p63 gene (Fig. 1A). To generate mice lacking these two domains, we deleted exon 12 of p63 by gene targeting (supplementary material Fig. S1). This strategy allowed us to delete both p63SAM and p63TI from Cα while leaving the Cγ isoform intact, as it is encoded by alternative exon 10ʹ (Fig. 1A). As Cα and Cβ share exon 12, these mice also lack full-length p63β isoforms. We confirmed that expression of both full-length Cα and Cβ was absent in homozygous mutant (p63C−/−) mice, whereas expression of Cγ was similar between p63C−/− mice and the wild-type (WT) control (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Alterative splicing at the p63 C-terminus in p63C−/− mice. (A) Structure and splicing of the p63 C-terminus in WT and ΔC p63 alleles. Arrowheads indicate stop codons in each isoform. The p63SAM and p63TI domains are illustrated. Exons are numbered. (B) Expression of p63 C-terminus variants in WT and p63C−/− epidermis as assessed by PCR. p63C−/− epidermal cells predominantly express Cα′, which lacks both the p63SAM and p63TI domains, whereas WT cells express full-length Cα. (C) Sequencing of Cα′ and Cβ′ expressed in p63C−/− mice. Stop codons are underlined. Arrows in A indicate the primer pair used to amplify the Cα′ and Cβ′ splicing variants. (D) Structure of p63 isoforms expressed in WT and p63C−/− mice. p63Cα′ and p63Cβ′ isoforms are collectively referred to as p63ΔC. DBD, DNA-binding domain; OD, oligomerization domain. (E) qPCR analysis of the N-terminus of the p63 gene in WT and p63C−/− epidermal cells. Shown is expression of TAp63 relative to ΔNp63, with the ΔNp63 level in WT being set to 1.0. Error bars indicate s.d. (F) Western blot with anti-p63 antibody of E14.5 whole epidermal cell extracts from WT, p63C−/− and p63C+/− mice. Asterisk indicates non-specific signal. Full, full-length ΔNp63α; ΔC, ΔNp63ΔC.

To analyze alternative splicing at the C-terminus resulting from the deletion of exon 12, we sequenced the fragments amplified from p63C−/− epidermal cell cDNA (Fig. 1B,C). Our data show that the major transcript was encoded by exon 11 spliced to exon 13 (termed Cαʹ), while a minor transcript resulted from splicing of exon 11 to exon 14 (termed Cβʹ). In both transcripts, stop codons appear shortly after the splicing sites by frameshift, resulting in the addition of only one and eight amino acids after exon 11, respectively (Fig. 1C; supplementary material Fig. S2). These Cαʹ and Cβʹ isoforms in p63C−/− mice were collectively referred to as the ΔC isoform (Fig. 1D).

To determine whether targeting of exon 12 influences p63 gene promoter activities, we performed qPCR using TAp63- and ΔNp63-specific primers (Fig. 1E). Our data show that relative expression of TAp63 and ΔNp63 was unchanged in p63C−/− mice compared with WT littermates, indicating that the manipulation of the p63 locus at the distal region does not affect p63 gene promoter activities.

We next investigated p63 protein expression in p63C−/− mice by western blot (Fig. 1F). As ΔNp63α is the predominant p63 isoform expressed in WT epidermal cells, the major p63 isoform detected in p63C−/− keratinocytes likely represents the ΔNp63 isoform lacking Cα (hereafter refered to as ΔNp63ΔC). Together, these data demonstrate that p63C−/− mice lack both p63SAM and p63TI domains from Cα without significant changes to either p63 gene promoter activity or p63γ isoform expression. Thus, p63C−/− mice are useful for elucidating the function of Cα/β in the context of both the TAp63 and ΔNp63 isoforms.

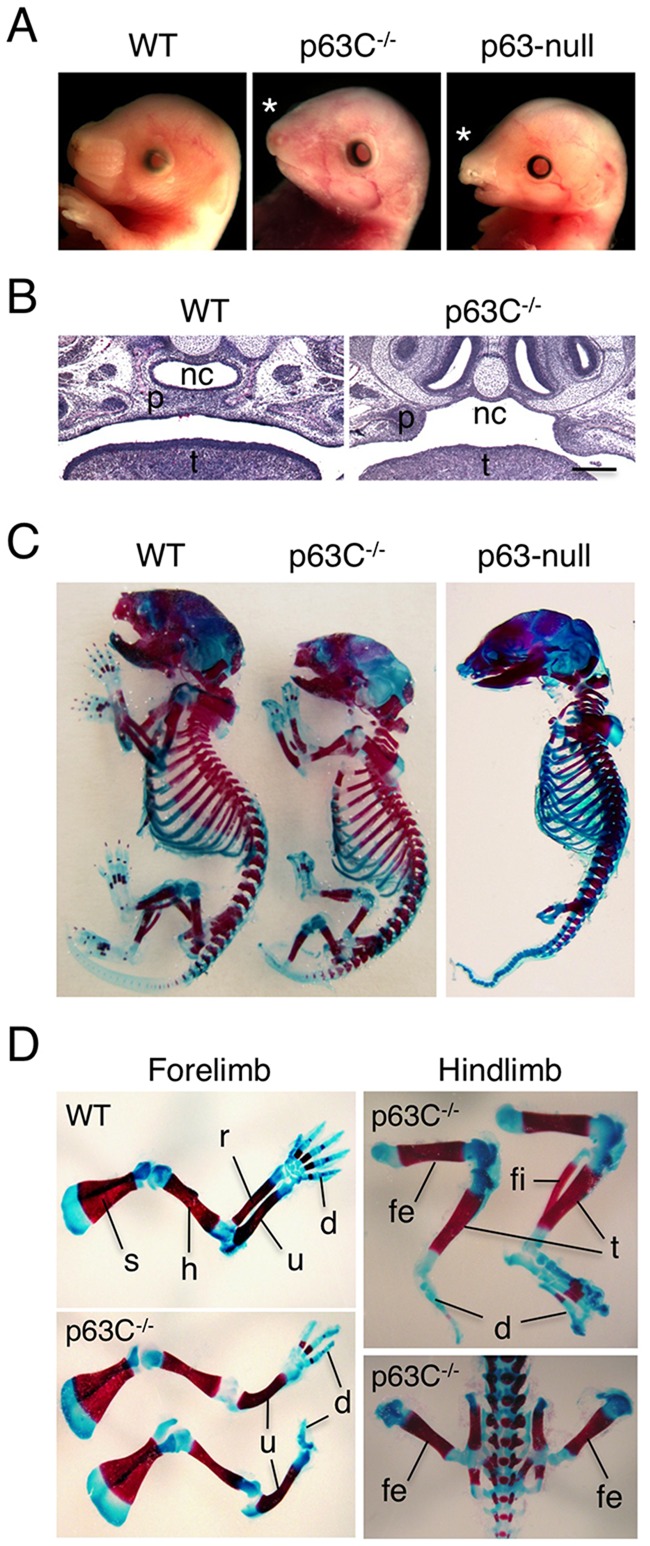

Craniofacial and skeletal phenotypes in p63C−/− mice

Heterozygous mutant (p63C+/−) mice were grossly normal and fertile. Although homozygotes were born at near Mendelian ratios (p63C+/+:p63C+/−:p63C−/−=27.9%:43.7%:28.4%, n=197) they died shortly after birth due to a significant loss of the skin, resulting in dehydration and neglect by mothers. Although this neonatal lethality is similar to that observed in p63-null mice (Mills et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999), we noted that craniofacial defects in p63C−/− embryos were less significant than those in p63-null mice (Fig. 2A). Whereas all p63-null mice show both cleft lip and cleft palate, some p63C−/− embryos (35%, n=23) lack cleft lip although cleft palate is still evident (Fig. 2B). As p63-null mice used in this study were generated in parallel with p63C−/− mice in the same genetic background (supplementary material Fig. S3), these data indicate that p63C−/− and p63-null mice are phenotypically different and highlight the functional significance of the p63 C-terminus during embryonic development.

Fig. 2.

Craniofacial and skeletal abnormalities in p63C−/− mice. (A) Gross appearance of the head of E17.5 WT, p63C−/− and p63-null mice. Whereas p63-null mice show cleft lip, p63C−/− mice frequently lack this characteristic as indicated by asterisks. (B) H&E staining of coronal sections of E17.5 WT and p63C−/− mouse heads showing the absence and presence, respectively, of cleft of the secondary palate. nc, nasal cavity; p, palatal shelf; t, tongue. Scale bar: 250 µm. (C) Skeletal staining of E17.5 WT, p63C−/− and p63-null mice showing relatively well developed forelimbs and hindlimbs in p63C−/− mice compared with those in p63-null mice. (D) Enlarged views of forelimbs and hindlimbs of WT and p63C−/− mice. s, scapula; h, humerus; r, radius; u, ulna; d, digits; fe, femur; fi, fibula; t, tibia.

Skeletal analysis of whole embryos revealed further differences between p63-null and p63C−/− mice. Consistent with previous studies (Mills et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999), p63-null embryos exhibit severely impaired forelimb development and a complete absence of hindlimbs (Fig. 2C). By contrast, both fore- and hindlimbs in p63C−/− embryos were more developed (Fig. 2C,D). For example, the majority of forelimbs in p63C−/− mice (81%, n=42) show grossly normal development of the humerus and ulna, although the radius is lacking, with either syndactyly or ectrodactyly (Fig. 2D). Strikingly, in 75% of p63C−/− mice (n=52), hindlimbs show normal femur development (Fig. 2D). The frequency of mice showing development of further hindlimb structure was lower; however, 23% and 8% of p63C−/− embryos showed relatively normal development of tibia and fibula, respectively (Fig. 2D). Approximately 14% of p63C−/− embryos developed digits with either syndactyly or ectrodactyly (Fig. 2D). Together, these data indicate that, in contrast to the p63-null condition, p63ΔC proteins support the initial development of limbs but that alterations in p63 C-terminus function restrict further progression of limb development.

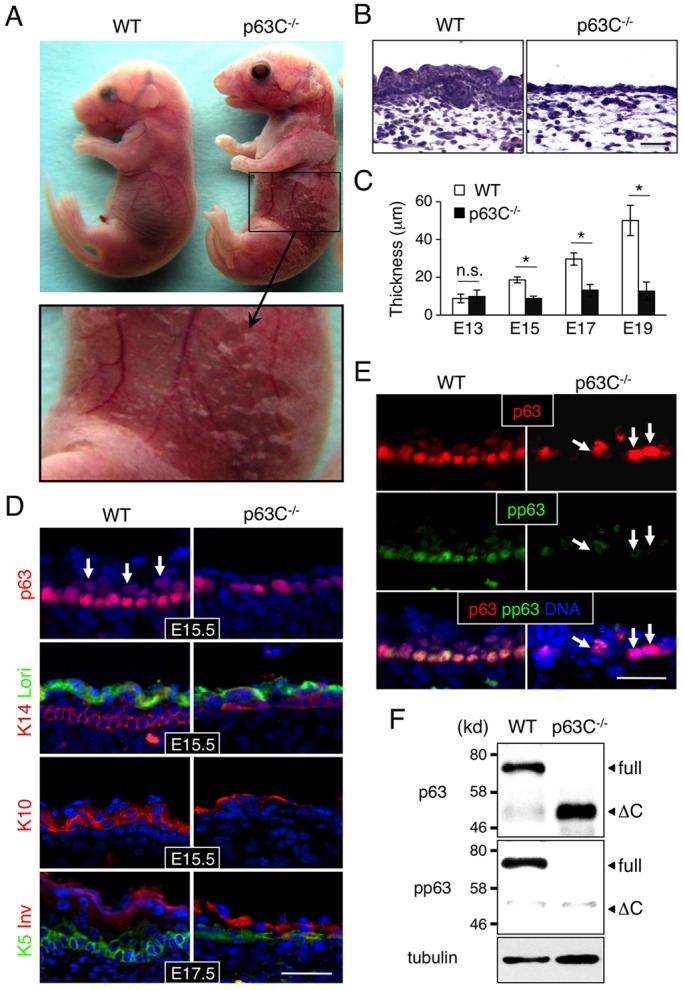

Epidermal phenotypes in p63C−/− mice

Normal development of limbs requires a close interplay between the ectoderm and underlying mesenchyme (Johnson and Tabin, 1997). As described above, p63C−/− embryos show more advanced limb development than p63-null mice, suggesting that epidermal cells in p63C−/− embryos are still capable of supporting epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. Indeed, macroscopic examination revealed that, whereas p63-null embryos are translucent and devoid of epidermis by embryonic day (E) 17.5 (supplementary material Fig. S3C,D), skin covered 60-80% of the body of p63C−/− embryos at the same developmental stage, although it was severely eroded (Fig. 3A). Microscopic analysis using Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining showed that p63C−/− mouse epidermis is hypoplastic and significantly thinner than that of WT littermates and lacks hair follicle development (Fig. 3B,C).

Fig. 3.

Epidermal hypoplasia in p63C−/− mice. (A) Representative E17.5 WT and p63C−/− mouse embryos (top) and an enlarged view of the p63C−/− mouse abdomen showing severe skin erosion (bottom). (B) H&E staining of E17.5 WT and p63C−/− mouse epidermis. Note that p63C−/− mouse epidermis is significantly thinner than that of WT and lacks hair follicle development. (C) Changes in epidermal thickness during development (mean±s.d.). *P<0.01; n.s., not significant. (D) Immunofluorescence of WT and p63C−/− mouse epidermis with the indicated antibodies, counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (DNA, blue). Arrows indicate p63-positive cells expanding into the suprabasal layers in WT epidermis. Lori, loricrin; Inv, involucrin. (E) Immunofluorescence of E15.5 WT and p63C−/− mouse epidermis with anti-p63 and anti-phosphorylated p63 (pp63) antibodies, counterstained with Hoechst 33342. Arrows indicate high p63-positive cells with low phosphorylation in the basal layer of the p63C−/− mouse epidermis. (F) Western blot of whole epidermal cell extracts from E15.5 WT and p63C−/− mice. The membrane was probed first with anti-pp63 antibody, stripped and then reprobed with anti-pan-p63 antibody. Full, full-length ΔNp63α; ΔC, ΔNp63ΔC. Scale bars: 50 µm.

To characterize epidermal cell differentiation in p63C−/− embryos, we stained sections of the epidermis with markers of basal cells [cytokeratin 14 (K14; also known as keratin 14, Krt14) and K5], a marker of the spinous layer (K10) and markers of terminally differentiated epithelium (loricrin and involucrin) (Eckert and Green, 1986; Freedberg et al., 2001; Hohl et al., 1991; Ivanyi et al., 1989). Our data show that marker expression was comparable in p63C−/− and WT epidermis (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the hypoplastic epidermis in p63C−/− mice is not due to a block in differentiation. Notably, however, staining of E15.5 epidermis with anti-p63 antibody showed that, whereas a large number of p63-positive cells were found in the suprabasal layer of WT epidermis, the majority of p63-positive cells in p63C−/− mice remained in the basal layer (Fig. 3D, top). This hypoplastic characteristic of progenitor cells was also seen in other epithelial tissues in p63C−/− mice (supplementary material Fig. S4). For instance, developing eyelids remained thinner and unfused in p63C−/− mice, whereas the eyelids of WT littermates are densely populated by p63-positive epithelial progenitor cells and are completely fused at the midline. Likewise, dental epithelial progenitors expand and develop into a large number of outer and inner enamel epithelia of the molar in WT embryos, but they remain in only a few cell layers in p63C−/− mice. Together, these data indicate that epithelia remain hypoplastic in many tissues of p63C−/− mice due to reduced expansion of epithelial progenitor cells.

We have shown previously that phosphorylation of serine residues at position 66/68 of ΔNp63 is associated with expansion of epidermal progenitor cells (Suzuki and Senoo, 2012, 2013). To determine whether S66/68 phosphorylation of ΔNp63 is reduced in p63C−/− epidermal cells, we co-stained E15.5 epidermis with anti-pan-p63 and anti-S66/68 antibodies (Fig. 3E). Our data show that, whereas virtually all basal cells in WT epidermis exhibit relatively high levels of S66/68 phosphorylation, the majority of p63-positive cells in p63C−/− mice were low to negative for this marker (Fig. 3E,F), suggesting that epidermal progenitor cells in p63C−/− mice are less proliferative than those in the WT control. We extended our analysis of S66/68 phosphorylation to tongue epithelium, another epithelial tissue showing hypoplasia in p63C−/− mice, and obtained similar results (supplementary material Fig. S5A).

To determine whether increased apoptosis promotes the hypoplastic epidermis observed in p63C−/− mice, we stained sections prepared from p63C−/− and WT embryos with anti-cleaved caspase 3 antibody. However, no evidence of enhanced apoptosis in p63C−/− mouse epidermis was detected at E15.5 (supplementary material Fig. S6), indicating that increased apoptosis does not account for the hypoplastic epidermis of p63C−/− mice. Collectively, these data demonstrate that the C-terminus of p63 plays a crucial role in regulating the expansion of epidermal progenitor cells but is dispensable for their differentiation and survival.

Decreased proliferative capacity of epidermal progenitor cells in p63C−/− mice

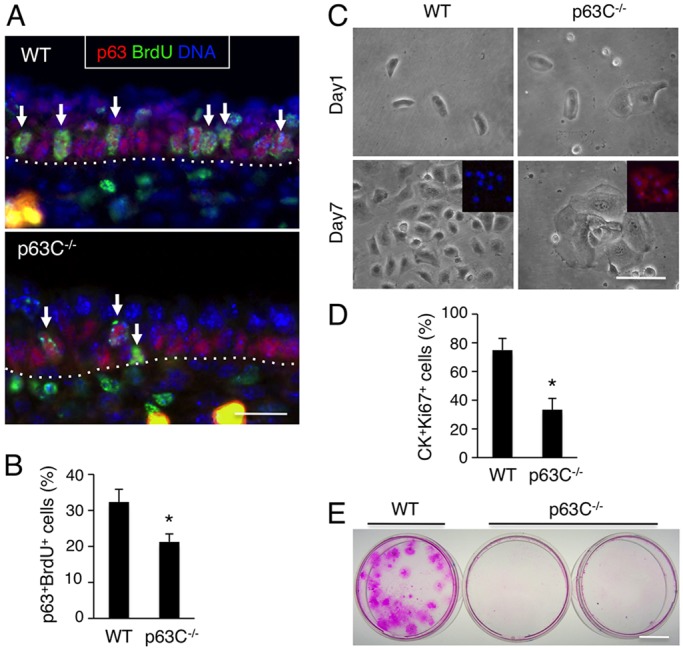

Having excluded obvious alterations in differentiation and apoptosis, we next investigated whether hypoplastic epidermis in p63C−/− embryos is accompanied by decreased proliferation of epidermal progenitor cells. We first investigated the proliferation of p63C−/− epidermal progenitor cells in vivo by injecting BrdU into pregnant mice of p63C+/− intercrosses 2 h prior to sacrifice, followed by sectioning and staining of WT and p63C−/− mouse epidermis with anti-p63 and anti-BrdU antibodies (Fig. 4A). Notably, our data show that the relative frequency of p63+ BrdU+ epidermal progenitor cells was significantly lower in p63C−/− mice than in WT littermates at E15.5 (Fig. 4B), indicating that the C-terminus of p63 is crucial for the proliferation of epidermal progenitors.

Fig. 4.

Reduced proliferative capacity of p63C−/− epidermal cells. (A) Immunofluorescence of E15.5 WT and p63C−/− mouse epidermis with anti-BrdU and anti-p63 antibodies, counterstained with Hoechst 33342. Arrows indicate representative p63+ BrdU+ epidermal progenitor cells. Dotted lines indicate the epidermal-dermal border. (B) Quantification of A (mean±s.e.m.). *P<0.01. (C) Epidermal cells were isolated from E14.0 WT and p63C−/− mouse embryos, seeded at clonal density in Matrigel-coated dishes and cultivated for 7 days. Inset shows high expression of involucrin (red) in p63C−/− epidermal cells, which is absent in the WT counterpart. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342. (D) Proliferation of WT and p63C−/− mouse epidermal cells at day 5 of cultivation. Shown are percentages of CK+ Ki67+ epidermal cells (mean±s.e.m.). *P<0.01. CK refers to pan-cytokeratin. (E) Staining of WT and p63C−/− mouse epidermal cells with Rhodamine B at 3 weeks of culture. No macroscopically visible clones were detected in p63C−/− cell cultures. Scale bars: 25 µm in A,C; 1 cm in E.

Next, to determine the long-term consequence of loss of the p63 C-terminus for the proliferative capacity of epidermal progenitor cells, we isolated epidermal cells from E14.0 WT and p63C−/− embryos and cultured them at clonal density in a defined keratinocyte medium. Our data show that, in contrast to the densely packed and highly proliferative WT keratinocytes, p63C−/− keratinocytes became large and flattened within the first few days, with reduced growth as determined by Ki67 staining and high expression of involucrin (Fig. 4C,D). These data are consistent with our in vivo observation that p63C−/− epidermal cells undergo premature differentiation with a reduced ability to propagate into suprabasal cell populations (Fig. 3D,E). Accordingly, extended cultivation of these keratinocytes showed that, whereas WT cells grew into large clones, p63C−/− cells did not yield any macroscopically visible clones at 3 weeks of culture as determined by Rhodamine B staining (Fig. 4E). Together, these data indicate that p63C−/− epidermal progenitor cells have a reduced proliferative capacity compared with their WT counterparts.

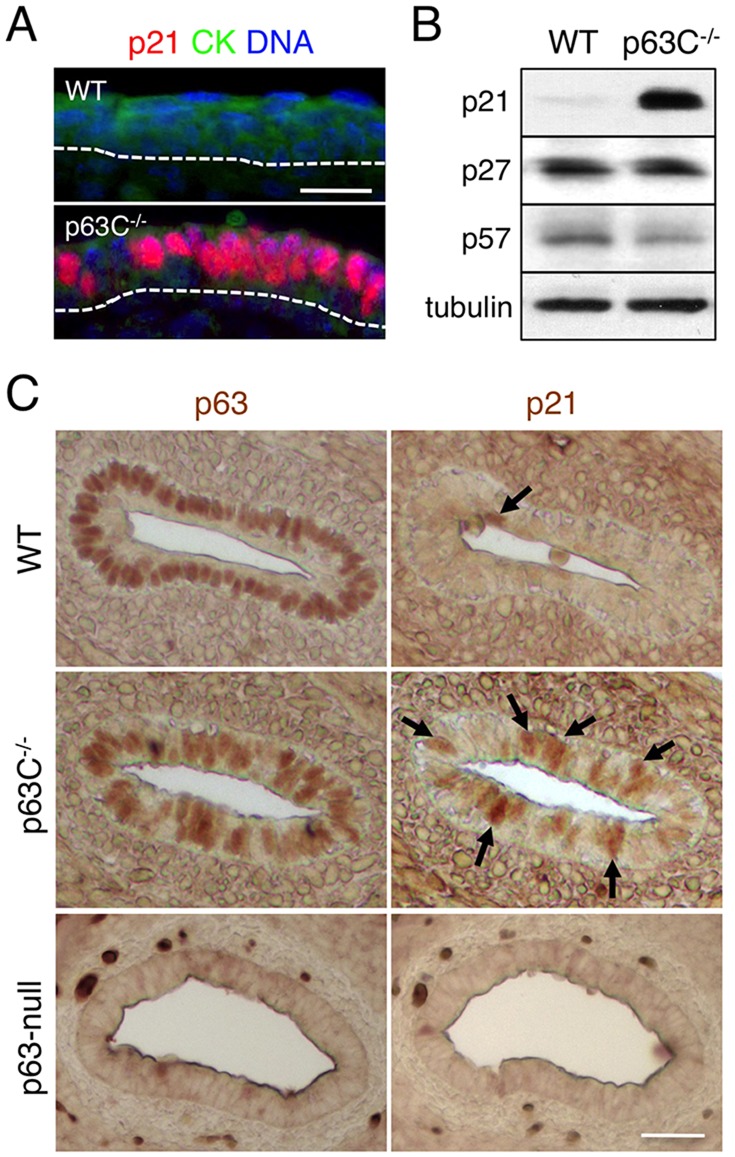

Increased expression of p21Waf1/Cip1 in epidermal progenitor cells of p63C−/− mice

As epidermal progenitor cells in p63C−/− mice showed reduced cell cycle progression (Fig. 4), we next investigated expression of the CDK inhibitor p21Waf1/Cip1, a well characterized downstream target of p63 (Su et al., 2013) with growth suppressive function in keratinocytes (Di Cunto et al., 1998; Missero et al., 1996). We first stained sections of E15.5 WT and p63C−/− epidermis with anti-p21Waf1/Cip1 antibody and found that, unlike the WT control, p63C−/− epidermis had a high frequency of epidermal cells with high p21Waf1/Cip1 expression (Fig. 5A). We confirmed that expression of p21Waf1/Cip1 was significantly higher in p63C−/− mice than in WT littermates by western blot using whole epidermal cell extracts (Fig. 5B). Expression of p53, a strong activator of p21Waf1/Cip1 expression, was undetectable in epidermal cells from either p63C−/− or WT mice (supplementary material Fig. S7), indicating that increased expression of p21Waf1/Cip1 in p63C−/− mice is not due to dysregulated p53 expression. We also showed that expression of two other closely related CDK inhibitors, p27Kip1 (Cdkn1b) and p57Kip2 (Cdkn1c), was similar in p63C−/− and WT mice (Fig. 5B). As p57Kip2 is a known p63 target gene (Beretta et al., 2005; Su et al., 2009), these data indicate that alterations to p63 C-terminus function selectively influence a subset of p63 target genes.

Fig. 5.

Upregulation of p21Waf1/Cip1 expression in p63C−/− mouse epithelia. (A) Immunofluorescence of E15.5 WT and p63C−/− mouse epidermis with anti-p21Waf1/Cip1 and anti-pan-cytokeratin (CK) antibodies, counterstained with Hoechst 33342. Dotted lines indicate epidermal-dermal border. (B) Western blot of whole epidermal cell extracts from E15.5 WT and p63C−/− mice with the antibodies to p21Waf1/Cip1, p27Kip1 and p57Kip2. Anti-Tubulin α antibody was used as a loading control. (C) Immunohistochemistry of mouse esophagus with anti-p63 (left) and anti-p21Waf1/Cip1 (right) antibodies. Data shown are representative of WT and p63C−/− mice at E15.5 and p63-null mice at E17.5. Arrows indicate epidermal cells with high p21Waf1/Cip1 expression. Scale bars: 25 µm in A; 50 µm in C.

To determine whether the increase in p21Waf1/Cip1 expression in p63C−/− mice is specific to the skin epidermis or is common to other epithelia, we performed additional staining of sections of WT and p63C−/− mouse esophagus, a tissue that expresses high levels of p63. Like epidermis, the esophageal epithelium in p63C−/− mice exhibited high p21Waf1/Cip1 expression, whereas cells with detectable p21Waf1/Cip1 levels in WT mice were rare (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that an increase in p21Waf1/Cip1 expression in p63C−/− mice is common among different epithelial cell types that normally express p63.

Finally, our data further show that esophageal epithelial cells in p63-null mice had no detectable p21Waf1/Cip1 expression (Fig. 5C), indicating that increased expression of p21Waf1/Cip1 in p63C−/− mice does not result from the loss of function of p63 but is instead likely to reflect altered functions of p63ΔC isoforms. Collectively, these data suggest that p63ΔC proteins, in the context of either the TAp63 or ΔNp63 isoform or a combination of both, promote p21Waf1/Cip1 expression in p63C−/− epithelia.

Cα balances TAp63 and ΔNp63 functions in the control of p21Waf1/Cip1 expression

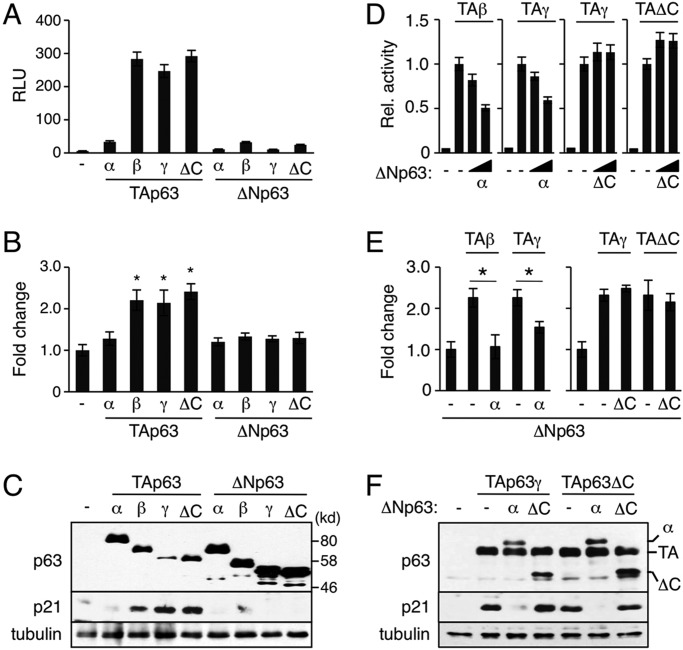

To gain insight into how deletion of the p63 C-terminus promotes p21Waf1/Cip1 expression, we first compared the transcriptional activity of TAp63ΔC with that of other TAp63 isoforms in the non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line H1299 using a minimal p21Waf1/Cip-luciferase reporter construct that harbors the p63/p53 binding site (Suzuki et al., 2012). H1299 cells are ideal for our study as they have a homozygous deletion of the p53 gene with no detectable endogenous p63 expression and thus induce p21Waf1/Cip1 gene expression in response to ectopic p63 (Zeng et al., 2002).

Unlike TAp63α, our data show that TAp63ΔC upregulates p21Waf1/Cip1 reporter activity to a similar extent as transcriptionally active TAp63β and TAp63γ isoforms (Fig. 6A). We also show that the stimulation of the p21Waf1/Cip1 reporter reflects endogenous p21Waf1/Cip1 expression at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 6B,C). This raises the possibility that the loss of the p63 C-terminus enhances the total activity of TAp63 in stimulating p21Waf1/Cip1 gene expression in p63C−/− mice as compared with the WT control. However, as ΔNp63α normally counterbalances TAp63-dependent transcriptional activity in a WT setting (Yang et al., 1998), we next determined whether ΔNp63ΔC has an impaired dominant-negative activity against TAp63γ and TAp63ΔC, two transcriptionally active TAp63 isoforms expressed in p63C−/− mice. Indeed, our data show that, whereas ΔNp63α inhibited both TAp63β- and TAp63γ-dependent transcriptional activation of the p21Waf1/Cip1 reporter in a dose-dependent manner, ΔNp63ΔC lacked such ability against both the TAp63γ and TAp63ΔC isoforms (Fig. 6D). We confirmed that changes in p21Waf1/Cip1 reporter activity correlated with those of endogenous p21Waf1/Cip1 expression at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 6E,F). We conclude that Cα balances TAp63 and ΔNp63 isoform functions in the control of p21Waf1/Cip1 expression.

Fig. 6.

Altered p63ΔC functions in control of p21Waf1/Cip1 expression. (A-C) Stimulation of p21Waf1/Cip1 expression by TAp63ΔC. H1299 cells were transfected with 1.0 µg plasmid expressing each p63 isoform. Samples were prepared 24 h after transfection. (A) Reporter assays using the minimal p21Waf1/Cip1 reporter (mean±s.d.). RLU, relative light unit. (B) qPCR analysis of endogenous p21Waf1/Cip1 gene expression. Values are mean±s.d. with the basal level set to 1.0. *P<0.05. (C) Western blot with anti-p63 and anti-p21Waf1/Cip1 antibodies. (D-F) Loss of dominant-negative activity of ΔNp63ΔC against TAp63-dependent transactivation of p21Waf1/Cip1. (D) Reporter assays using the minimal p21Waf1/Cip1 reporter. H1299 cells were transfected with 0.3 µg TAp63 plasmid alone or together with an increasing amount of ΔNp63 plasmid at ratios of 100:1 or 30:1 and cells were lysed 24 h after transfection. Data shown are mean±s.d. Transactivation by TAp63 alone was set to 1.0. (E) qPCR analysis of endogenous p21Waf1/Cip1 gene expression. H1299 cells were transfected with 1.0 µg TAp63 plasmid alone or together with ΔNp63 plasmid at a 50:1 ratio and RNA was extracted 24 h after transfection. Values are mean±s.d. with the basal level set to 1.0. *P<0.05. (F) Western blot analysis of p21Waf1/Cip1 expression. H1299 cells were transfected with 1.0 µg TAp63 plasmid alone or together with ΔNp63 plasmid at a 20:1 ratio and cells were lysed 36 h after transfection. The same cell extracts were used to verify expression of each p63 isoform (top). (C,F) Anti-tubulin α antibody was used as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

Studies of mice deficient for p63 have shown that it is a key regulator of ectodermal development (Mills et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999). In humans, mutations in the p63 gene (TP63) cause at least seven syndromic and non-syndromic disorders, each with different combinations of ectodermal dysplasia, split hand/foot malformation and orofacial clefting (Rinne et al., 2007). Our data show that p63C−/− mice exhibit all of these characteristics (Figs 2 and 3), indicating that the C-terminus is central to p63 function during embryonic development. Cα is frequently mutated or deleted in AEC patients and indeed p63C−/− mice show AEC-like severe skin erosion and fragility (Fig. 3A). However, the presence of abnormalities in orofacial and limb development in p63C−/− mice indicates that they will also be useful for assessment of additional p63-associated disorders. Specifically, relatively rare mutations that lead to the generation of p63ΔC-like proteins are found in patients with EEC syndrome and LMS, both of which exhibit the three p63-associated characteristics mentioned above (Celli et al., 1999; van Bokhoven et al., 2001). Our studies reveal that loss of Cα leads to the dysregulation of both TAp63 and ΔNp63 isoform functions (Fig. 6). Although these changes can be explained by the loss of function of the TI domain, the SAM domain also plays a key role in regulating p63 function in vivo (Ferone et al., 2012). Thus, it will be important to determine the specific roles of the p63SAM and p63TI domains and whether a mutation in one domain affects the function(s) of the other during development. Answering these questions will contribute to our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying p63-associated EDs.

As a member of the p53 family of transcription factors, p63 is likely to carry out its function through controlling the expression of genes that are crucial for stem cell properties (Yang et al., 2006). p21Waf1/Cip1 is one of the best-characterized downstream targets of p63, and the growth-suppressing function of this CDK inhibitor is well established. However, how p21Waf1/Cip1 expression is regulated in epidermal progenitor cells in vivo remains an open question (Ohtani et al., 2007). In the present study, we found that p63 can regulate p21Waf1/Cip1 gene expression through a mechanism that is dependent on the function of the p63 C-terminus. Our data suggest that the p63 C-terminus regulates the functional equilibrium between TAp63 and ΔNp63 isoforms in controlling target gene expression (Fig. 6). However, as p63C−/− epidermal cells show significantly elevated levels of p21Waf1/Cip1 but not of the closely related p63 target p57Kip2 (Beretta et al., 2005; Su et al., 2009), our studies indicate that the p63 C-terminus influences only a subset of downstream target genes. Further investigation of the mechanistic basis for this effect will provide significant insight into stem cell regulatory pathways governed by p63.

Notably, p21Waf1/Cip1 KO mice have an increased number of epidermal progenitor cells with high proliferative potential compared with WT mice (Topley et al., 1999), indicating that p21Waf1/Cip1 plays a key role in restricting the proliferative capacity of epidermal progenitors. The function of p21Waf1/Cip1 in stem cell maintenance is operative in other cell types, including hematopoietic and neuronal progenitor cells (Cheng et al., 2000; Kippin et al., 2005). However, as these cells do not express p63, it would be interesting to investigate whether cell type-specific regulators of stem cell maintenance (Lessard and Sauvageau, 2003; Molofsky et al., 2003; Park et al., 2003) are involved in the regulation of p21Waf1/Cip1 expression. We show in the present study that epidermal progenitor cells derived from p63C−/− mice have reduced proliferative capacity with enhanced p21Waf1/Cip1 expression (Figs 4 and 5). Thus, a connection has been established between p63 C-terminus functions and cell cycle progression in control of the proliferative potential of epidermal progenitor cells. However, as we have reported previously, a complete absence of all p63 isoforms also reduces the proliferative capacity of epidermal progenitor cells (Senoo et al., 2007). Thus, it is likely that alternative pathways exist by which p63 regulates the proliferative potential of epidermal progenitor cells independently of p21Waf1/Cip1 function. Deciphering gene programs altered by p63 C-terminus deficiency versus total loss of p63 function will provide further insight into the molecular mechanisms that regulate proliferative potential.

Finally, cell proliferation and differentiation are coupled during embryonic development and in self-renewing tissues of the adult, including the skin. Skewing this balance toward proliferation can cause tumorigenesis (Owens and Watt, 2003; Perez-Losada and Balmain, 2003). In this regard, p63 and p21Waf1/Cip1 might share common tumor-suppressive machineries. For instance, loss of p21Waf1/Cip1 cooperates with Ras oncogene (Hras) in the induction of aggressive and relatively undifferentiated tumors in vivo (Missero et al., 1996). Conversely, Ras-driven transformation of p53-deficient cells is counteracted by ectopic expression of TAp63 in a p21Waf1/Cip1-dependent manner (Guo et al., 2009), whereas the ΔNp63 isoform cooperates with Ras to promote tumor-initiating stem-like proliferation (Keyes et al., 2011). It will be important to determine the molecular mechanisms by which p63 and loss of p21Waf1/Cip1 cooperate in the regulation of genes required for the proliferative potential of epidermal progenitor cells versus those favoring malignant transformation. Thus, an exciting area of future study is the close interplay between the classical cell cycle and stem cell pathways in the control of self-renewal and tumorigenesis of epithelia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All procedures were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pennsylvania. For staged embryos, the day of the vaginal plug was designated E0.5.

Generation of p63C−/− mice

Genomic p63 DNA was isolated from BAC clones (Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute, Oakland, CA, USA). The targeting vector consists of a 3.2 kb HindIII/HincII homologous fragment containing exon 11 followed by a PGK-NeoR cassette flanked by loxP sites and a 2.3 kb homologous fragment containing exon 13, and a PGK-TK cassette at the 3′-end. Gene targeting was performed in V6.5 (129×B6 F1 hybrid) embryonic stem cells (ESCs) (Eggan et al., 2001). Two correctly targeted ESC clones were microinjected into C57BL/6 blastocysts to obtain chimeric mice. Male chimeras were mated to female C57BL/6 mice to achieve germline transmission of the targeted (Neo) allele and heterozygous mutant mice were crossed with Actβ-Cre transgenic mice in a FVB/N background (Jackson Labs) to remove the Neo cassette (ΔNeo allele). Genotyping of progeny was performed by PCR using tail DNA and the Neo and ΔNeo allele and Cre transgene primers listed in supplementary material Table S1. Mutant mouse colony was maintained by intercrossing heterozygous mice in the absence of the Actβ-Cre transgene

Generation of p63-null mice

Mice deficient for all p63 isoforms were generated and maintained in the same genetic background as described above. The 5′ homologous arm included a 5.0 kb fragment extending to the end of the coding sequences of p63 exon 5, ligated in frame to a start codon (ATG)-depleted EGFP expression cassette derived from pEGFP-N1 (BD Biosciences). A 4.2 kb SphI fragment harboring p63 exons 8 and 9 was used as the 3′ homologous arm. Mutant p63 alleles were identified by PCR using tail DNA and the primer pairs listed in supplementary material Table S1.

Southern blot

Genomic DNA was digested with restriction enzymes, separated in 0.8% agarose gels and transferred to nylon membranes (Sigma-Aldrich). To confirm homologous recombination at the C-terminus of p63, 1.4 kb and a 560 bp genomic fragments outside the targeting vector were radiolabeled with [32P]dCTP (GE Healthcare) using the Rediprime II DNA Labeling System (GE Healthcare) and used as probes. To confirm homologous recombination at the p63 DNA-binding domain, 600 bp and 350 bp genomic DNA fragments outside the targeting vector were radiolabeled and used as probes.

Skeletal staining

Skeletal staining was performed as previously described (Wallin et al., 1994) with some modifications. Briefly, embryos were eviscerated and the skin removed, then fixed in 95% ethanol for 5 days and then in 100% acetone for an additional 2 days at room temperature. Specimens were incubated in staining solution (0.015% Alcian Blue and 0.005% Alizarin Red S in 90% ethanol and 5% acetic acid) for 3 days at 37°C. Subsequently, specimens were rinsed in water and kept in 1% KOH for 2 days at room temperature, followed by clearing in a series of 0.8% KOH/20% glycerol, 0.5% KOH/50% glycerol and 0.2% KOH/80% glycerol for 3-5 days each. After complete clearing, specimens were stored in 100% glycerol.

Antibodies

The primary antibodies used in this study were mouse anti-p63 (4A4, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:250), rabbit anti-phosphorylated p63 (#4981, corresponding to S66/68 of ΔNp63α, Cell Signaling Technology; 1:100), mouse anti-p21Waf1/Cip1 (F-5, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:50 for immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence, and 1:300 for western blotting), mouse anti-p27Kip1 (p27/Kip1, BD Biosciences; 1:2000), rabbit anti-p57Kip2 (NBP1-61640, Novus Biologicals; 1:2000), mouse anti-p53 (PAb421, EMD Millipore; 1:2000), rabbit anti-mouse Ki67 (NB600-1209, Novus Biologicals; 1:50), rat anti-BrdU (ICR1, Abcam; 1:100), rabbit anti-cleaved caspase 3 (5A1E, Cell Signaling Technology; 1:200), rabbit anti-cytokeratin 5 (EP1601Y, Abcam; 1:4000), mouse anti-cytokeratin 14 (LL001, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:300), mouse anti-cytokeratin 10 (RSKE60, Abcam; 1:400), rabbit anti-loricrin (PRB-145, Covance; 1:1000), mouse anti-involucrin (SY5, NeoMarkers; 1:1000), mouse anti-pan-cytokeratin (AE1/AE3, Thermo Fisher Scientific; 1:200), rabbit anti-pan-cytokeratin (PA521985, Thermo Fisher Scientific; 1:100) and mouse anti-tubulin α (12G10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; 1:500). Secondary antibodies used for immunofluorescence were Alexa 488-goat anti-mouse IgG, Alexa 488-goat anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa 594-goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa 594-goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes). When a combination of mouse and rat primary antibodies was used, pre-adsorbed DyLight 594-goat anti-mouse IgG and pre-adsorbed DyLight 488-goat anti-rat IgG antibodies (Abcam) were used to avoid cross-reactivity. For DAB staining and western blot, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (KPL) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology) were used.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin overnight at 4°C. Paraffin-embedded sections were cut into 6 µm sections and antigen retrieval was performed by incubating the slides in 0.01 M citric acid buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 20 min. Sections were then blocked with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals) at room temperature for 30 min. Cultured epidermal cells were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 10 min and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min, followed by blocking at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, samples were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After three washes in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, samples were incubated with either fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature followed by counterstaining with Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes), or HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies followed by detection of the antigens using a DAB reagent kit (KPL).

BrdU labeling and detection

Pregnant mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg body weight 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (BD Biosciences). Two hours after injection, embryos were collected, fixed, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin blocks. Sections were treated with 2 N HCl for 10 min at 37°C and washed three times in PBS, followed by treatment with 0.025% trypsin for 15 min at 37°C. Staining was then performed as described (Suzuki and Senoo, 2013).

Western blot

Cells were lysed in a protein lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10% glycerol, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. After boiling for 5 min, whole cell extracts were subjected to 8-12% SDS-PAGE followed by western blot.

Cell culture

Human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells and human lung carcinoma H1299 cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 10 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in a humidified chamber at 37°C with 5% CO2. Primary epidermal cells were isolated from E14.0 mouse embryos. Briefly, embryos were collected into 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes and incubated in 0.25% trypsin at 37°C for 20 min with gentle agitation every 5 min without disrupting embryo structures. Cell suspensions were transferred into new tubes, neutralized and centrifuged at 1000 rpm (180 g) for 5 min. Cells were then suspended in CnT-57 basal keratinocyte medium supplemented with growth supplements (Cellntec) and 1×105 cells were seeded onto 35 mm dishes coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 3 weeks of culture, epidermal cell clones were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and visualized by staining with 1% Rhodamine B (Sigma-Aldrich).

qPCR and RT-PCR

Total RNA was purified using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies) and 1 µg was reverse transcribed using the ProtoScript M-MuLV First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (New England BioLabs). Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (Life Technologies) in an ABI 7900 HT machine. Relative expression of each gene to the housekeeping gene Rps18 or GAPDH was determined by the ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences used for qPCR are listed in supplementary material Table S1.

To analyze alternative splicing at the p63 C-terminus in p63C−/− mice, epidermal cell cDNAs were amplified with a primer pair Exon 11-forward and Exon 14-reverse. PCR products were separated in 1.2% agarose gels and DNA fragments corresponding to Cα′ (494 bp) and Cβ′ (400 bp) were purified and directly sequenced with primer 5′-GTGAGCCAGCTTATCAACCC-3′. Note that although the Exon 11-forward/Exon 14-reverse primer pair is also able to detect Cβ transcripts, they were below detection level in WT mice, probably owing to low expression and competition with Cα transcripts. Therefore, a second primer pair was used to detect Cβ transcripts: Exon 6-forward and Exon 12/14-reverse (852 bp). Cγ transcripts were amplified using Exon 6-forward and Exon 10′-reverse (648 bp). Primers are listed in supplementary material Table S1.

Construction of p63 plasmids

All p63 cDNAs used in this study were of human origin. ΔNp63 isoforms (α, β and γ) were myc-tagged at the N-terminus and subcloned into the pcDNA3 vector (Life Technologies), while TAp63 isoforms (α, β and γ) were 2×HA-tagged at the N-terminus and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Life Technologies). To generate p63ΔC isoforms, site-directed mutagenesis was performed using ΔNp63α in pUK21 as template with primer pair 5′-TTTCTTAGCGAGGTTGGGCTGTTC-3′ and 5′-TGTT-GGCTCCCATGCCATCAGGAA-3′, followed by self-ligation and direct sequencing to verify correct amplification. Mutant C-terminus was excised as a BsrGI/XhoI fragment and replaced with that in TAp63α and ΔNp63α.

Transient transfection and reporter assay

H1299 and HEK293T cells were seeded into 12-well plates at 1×105 cells/well the day before transfection. Transfections were performed using SuperFect transfection reagent (Qiagen). Twenty-four to 36 h later, cells were harvested and whole cell extracts and total RNA were prepared for western blot and qPCR, respectively. For reporter assays, H1299 cells were transiently transfected with p63-expressing plasmids along with 0.5 µg minimal p21Waf1/Cip1 reporter and 0.3 µg Renilla luciferase vector pRL-TK (Promega). The minimal p21Waf1/Cip1 reporter was constructed by inserting the 72 bp HindIII-SacI fragment harboring the p63/p53 binding site (Suzuki et al., 2012) of WWP-luc (El-Deiry et al., 1993) into the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega). Luciferase activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Firefly luciferase activities were normalized to Renilla luciferase control activities. In co-transfection experiments, pcDNA3 was used as carrier so that all wells received the same total amount of DNA.

Statistical analysis

Student's t-tests were performed and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Leslie King for critical reading of the manuscript, and Hirokuni Kobayashi and Malavika Bhattacharya for help in the initial development of this study.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

D.S. designed and performed the majority of the experiments and analyzed data. N.A.L., R.S., D.S. and M.S. generated mutant mice. M.S. conceived the project, performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript with input from coauthors.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Skin Disease Research Center [P30AR057217] and National Institutes of Health [R01AR066755] to M.S. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.118307/-/DC1

References

- Ali-Khan S. E. and Hales B. F. (2003). Caspase-3 mediates retinoid-induced apoptosis in the organogenesis-stage mouse limb. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 67, 848-860 10.1002/bdra.10090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow L. L., van Bokhoven H., Daack-Hirsch S., Andersen T., van Beersum S. E. C., Gorlin R. and Murray J. C. (2002). Analysis of the p63 gene in classical EEC syndrome, related syndromes, and non-syndromic orofacial clefts. J. Med. Genet. 39, 559-566 10.1136/jmg.39.8.559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta C., Chiarelli A., Testoni B., Mantovani R. and Guerrini L. (2005). Regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p57Kip2 expression by p63. Cell Cycle 4, 1625-1631 10.4161/cc.4.11.2135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickenbach J. R., Stern M. M., Grinnell K. L., Manuel A. and Chinnathambi S. (2006). Epidermal stem cells have the potential to assist in healing damaged tissues. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 11, 118-123 10.1038/sj.jidsymp.5650009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C. and Fuchs E. (2009). Epidermal homeostasis: a balancing act of stem cells in the skin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 207-217 10.1038/nrm2636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candi E., Rufini A., Terrinoni A., Dinsdale D., Ranalli M., Paradisi A., De Laurenzi V., Spagnoli L. G., Catani M. V., Ramadan S. et al. (2006). Differential roles of p63 isoforms in epidermal development: selective genetic complementation in p63 null mice. Cell Death Differ. 13, 1037-1047 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. A., Engiles J. B., Megee S. O., Senoo M. and Galantino-Homer H. L. (2011). Decreased expression of p63, a regulator of epidermal stem cells, in the chronic laminitic equine hoof. Equine Vet. J. 43, 543-551 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli J., Duijf P., Hamel B. C. J., Bamshad M., Kramer B., Smits A. P. T., Newbury-Ecob R., Hennekam R. C. M., Van Buggenhout G., van Haeringen A. et al. (1999). Heterozygous germline mutations in the p53 homolog p63 are the cause of EEC syndrome. Cell 99, 143-153 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81646-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T., Rodrigues N., Shen H., Yang Y.-g., Dombkowski D., Sykes M. and Scadden D. T. (2000). Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science 287, 1804-1808 10.1126/science.287.5459.1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cunto F., Topley G., Calautti E., Hsiao J., Ong L., Seth P. K. and Dotto G. P. (1998). Inhibitory function of p21Cip1/WAF1 in differentiation of primary mouse keratinocytes independent of cell cycle control. Science 280, 1069-1072 10.1126/science.280.5366.1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert R. L. and Green H. (1986). Structure and evolution of the human involucrin gene. Cell 46, 583-589 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90884-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggan K., Akutsu H., Loring J., Jackson-Grusby L., Klemm M., Rideout W. M. III, Yanagimachi R. and Jaenisch R. (2001). Hybrid vigor, fetal overgrowth, and viability of mice derived by nuclear cloning and tetraploid embryo complementation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 6209-6214 10.1073/pnas.101118898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Deiry W. S., Tokino T., Velculescu V. E., Levy D. B., Parsons R., Trent J. M., Lin D., Mercer W. E., Kinzler K. W. and Vogelstein B. (1993). WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75, 817-825 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferone G., Thomason H. A., Antonini D., De Rosa L., Hu B., Gemei M., Zhou H., Ambrosio R., Rice D. P., Acampora D. et al. (2012). Mutant p63 causes defective expansion of ectodermal progenitor cells and impaired FGF signalling in AEC syndrome. EMBO Mol. Med. 4, 192-205 10.1002/emmm.201100199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg I. M., Tomic-Canic M., Komine M. and Blumenberg M. (2001). Keratins and the keratinocyte activation cycle. J. Invest. Dermatol. 116, 633-640 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01327.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghadially R. (2012). 25 years of epidermal stem cell research. J. Invest. Dermatol. 132, 797-810 10.1038/jid.2011.434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green H. (2008). The birth of therapy with cultured cells. Bioessays 30, 897-903 10.1002/bies.20797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Keyes W. M., Papazoglu C., Zuber J., Li W., Lowe S. W., Vogel H. and Mills A. A. (2009). TAp63 induces senescence and suppresses tumorigenesis in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1451-1457 10.1038/ncb1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper J. W., Adami G. R., Wei N., Keyomarsi K. and Elledge S. J. (1993). The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell 75, 805-816 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohl D., Mehrel T., Lichti U., Turner M. L., Roop D. R. and Steinert P. M. (1991). Characterization of human loricrin. Structure and function of a new class of epidermal cell envelope proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 6626-6636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanyi D., Ansink A., Groeneveld E., Hageman P. C., Mooi W. J. and Heintz A. P. M. (1989). New monoclonal antibodies recognizing epidermal differentiation-associated keratins in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Keratin 10 expression in carcinoma of the vulva. J. Pathol. 159, 7-12 10.1002/path.1711590105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. L. and Tabin C. J. (1997). Molecular models for vertebrate limb development. Cell 90, 979-990 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80364-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur P. (2006). Interfollicular epidermal stem cells: identification, challenges, potential. J. Invest. Dermatol. 126, 1450-1458 10.1038/sj.jid.5700184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes W. M., Pecoraro M., Aranda V., Vernersson-Lindahl E., Li W., Vogel H., Guo X., Garcia E. L., Michurina T. V., Enikolopov G. et al. (2011). ΔNp63α is an oncogene that targets chromatin remodeler Lsh to drive skin stem cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Cell Stem Cell 8, 164-176 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippin T. E., Martens D. J. and van der Kooy D. (2005). p21 loss compromises the relative quiescence of forebrain stem cell proliferation leading to exhaustion of their proliferation capacity. Genes Dev. 19, 756-767 10.1101/gad.1272305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster M. I. (2010). p63 in skin development and ectodermal dysplasias. J. Invest. Dermatol. 130, 2352-2358 10.1038/jid.2010.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard J. and Sauvageau G. (2003). Bmi-1 determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem cells. Nature 423, 255-260 10.1038/nature01572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills A. A., Zheng B., Wang X.-J., Vogel H., Roop D. R. and Bradley A. (1999). p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature 398, 708-713 10.1038/19531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missero C., Calautti E., Eckner R., Chin J., Tsai L. H., Livingston D. M. and Dotto G. P. (1995). Involvement of the cell-cycle inhibitor Cip1/WAF1 and the E1A-associated p300 protein in terminal differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 5451-5455 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missero C., Di Cunto F., Kiyokawa H., Koff A. and Dotto G. P. (1996). The absence of p21Cip1/WAF1 alters keratinocyte growth and differentiation and promotes ras-tumor progression. Genes Dev. 10, 3065-3075 10.1101/gad.10.23.3065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molofsky A. V., Pardal R., Iwashita T., Park I.-K., Clarke M. F. and Morrison S. J. (2003). Bmi-1 dependence distinguishes neural stem cell self-renewal from progenitor proliferation. Nature 425, 962-967 10.1038/nature02060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani N., Imamura Y., Yamakoshi K., Hirota F., Nakayama R., Kubo Y., Ishimaru N., Takahashi A., Hirao A., Shimizu T. et al. (2007). Visualizing the dynamics of p21(Waf1/Cip1) cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor expression in living animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 15034-15039 10.1073/pnas.0706949104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada M., Ohba M., Kawahara C., Ishioka C., Kanamaru R., Katoh I., Ikawa Y., Nimura Y., Nakagawara A., Obinata M. et al. (1998). Cloning and functional analysis of human p51, which structurally and functionally resembles p53. Nat. Med. 4, 839-843 10.1038/nm0798-839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens D. M. and Watt F. M. (2003). Contribution of stem cells and differentiated cells to epidermal tumours. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 444-451 10.1038/nrc1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park I.-K., Qian D., Kiel M., Becker M. W., Pihalja M., Weissman I. L., Morrison S. J. and Clarke M. F. (2003). Bmi-1 is required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 423, 302-305 10.1038/nature01587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini G., Rama P., Mavilio F. and De Luca M. (2009). Epithelial stem cells in corneal regeneration and epidermal gene therapy. J. Pathol. 217, 217-228 10.1002/path.2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Losada J. and Balmain A. (2003). Stem-cell hierarchy in skin cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 434-443 10.1038/nrc1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao F. and Bowie J. U. (2005). The many faces of SAM. Sci. STKE. 286, pre7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rama P., Matuska S., Paganoni G., Spenelli A., De Luca M. and Pellegrini G. (2010). Limbal stem-cell therapy and long-term corneal regeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 147-155 10.1056/NEJMoa0905955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinne T., Brunner H. G. and van Bokhoven H. (2007). p63-associated disorders. Cell Cycle 6, 262-268 10.4161/cc.6.3.3796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinne T., Bolat E., Meijer R., Scheffer H. and van Bokhoven H. (2009). Spectrum of p63 mutations in a selected patient cohort affected with ankyloblepharon-ectodermal defects-cleft lip/palate syndrome (AEC). Am. J. Med. Genet. A 149A, 1948-1951 10.1002/ajmg.a.32793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano R.-A., Smalley K., Magraw C., Serna V. A., Kurita T., Raghavan S. and Sinha S. (2012). ΔNp63 knockout mice reveal its indispensable role as a master regulator of epithelial development and differentiation. Development 139, 772-782 10.1242/dev.071191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmale H. and Bamberger C. (1997). A novel protein with strong homology to the tumor suppressor p53. Oncogene 15, 1363-1367 10.1038/sj.onc.1201500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senoo M. (2013). Epidermal stem cells in homeostasis and wound repair of the skin. Adv. Wound Care 2, 273-282 10.1089/wound.2012.0372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senoo M., Seki N., Ohira M., Sugano S., Watanabe M., Tachibana M., Tanaka T., Shinkai Y. and Kato H. (1998). A second p53-related protein, p73L, with high homology to p73. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 248, 603-607 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senoo M., Pinto F., Crum C. P. and McKeon F. (2007). p63 is essential for the proliferative potential of stem cells in stratified epithelia. Cell 129, 523-536 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serber Z., Lai H. C., Yang A., Ou H. D., Sigal M. S., Kelly A. E., Darimont B. D., Duijf P. H. G., van Bokhoven H., McKeon F. et al. (2002). A C-terminal inhibitory domain controls the activity of p63 by an intramolecular mechanism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 8601-8611 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8601-8611.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X., Paris M., Gi Y. J., Tsai K. Y., Cho M. S., Lin Y.-L., Biernaskie J. A., Sinha S., Prives C., Pevny L. H. et al. (2009). TAp63 prevents premature aging by promoting adult stem cell maintenance. Cell Stem Cell 5, 64-75 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X., Chakravarti D. and Flores E. R. (2013). p63 steps into the limelight: crucial roles in the suppression of tumorigenesis and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 136-143 10.1038/nrc3446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki D. and Senoo M. (2012). Increased p63 phosphorylation marks early transition of epidermal stem cells to progenitors. J. Invest. Dermatol. 132, 2461-2464 10.1038/jid.2012.165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki D. and Senoo M. (2013). Expansion of epidermal progenitors with high p63 phosphorylation during wound healing of mouse epidermis. Exp. Dermatol. 22, 374-376 10.1111/exd.12139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H., Ito R., Ikeda K. and Tamura T.-a. (2012). TATA-binding protein (TBP)-like protein is required for p53-dependent transcriptional activation of upstream promoter of p21Waf1/Cip1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 19792-19803 10.1074/jbc.M112.369629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos C. D. and Bowie J. U. (1999). p53 Family members p63 and p73 are SAM domain-containing proteins. Protein Sci. 8, 1708-1710 10.1110/ps.8.8.1708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topley G. I., Okuyama R., Gonzales J. G., Conti C. and Dotto G. P. (1999). p21(WAF1/Cip1) functions as a suppressor of malignant skin tumor formation and a determinant of keratinocyte stem-cell potential. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9089-9094 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trink B., Okami K., Wu L., Sriuranpong V., Jen J. and Sidransky D. (1998). A new human p53 homologue. Nat. Med. 4, 747-748 10.1038/nm0798-747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong A. B., Kretz M., Ridky T. W., Kimmel R. and Khavari P. A. (2006). p63 regulates proliferation and differentiation of developmentally mature keratinocytes. Genes Dev. 20, 3185-3197 10.1101/gad.1463206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bokhoven H. and McKeon F. (2002). Mutations in the p53 homolog p63: allele-specific developmental syndromes in humans. Trends Mol. Med. 8, 133-139 10.1016/S1471-4914(01)02260-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bokhoven H., Hamel B. C. J., Bamshad M., Sangiorgi E., Gurrieri F., Duijf P. H. G., Vanmolkot K. R. J., van Beusekom E., van Beersum S. E. C., Celli J. et al. (2001). p63 Gene mutations in EEC syndrome, limb-mammary syndrome, and isolated split hand-split foot malformation suggest a genotype-phenotype correlation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 481-492 10.1086/323123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin J., Wilting J., Koseki H., Fritsch R., Christ B. and Balling R. (1994). The role of Pax-1 in axial skeleton development. Development 120, 1109-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt F. M. and Jensen K. B. (2009). Epidermal stem cell diversity and quiescence. EMBO Mol. Med. 1, 260-267 10.1002/emmm.200900033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall M. D., Mays D. J., Sniezek J. C. and Pietenpol J. A. (2003). The Delta Np63 alpha phosphoprotein binds the p21 and 14-3-3 sigma promoters in vivo and has transcriptional repressor activity that is reduced by Hay-Wells syndrome-derived mutations. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 2264-2276 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2264-2276.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A., Kaghad M., Wang Y., Gillett E., Fleming M. D., Dötsch V., Andrews N. C., Caput D. and McKeon F. (1998). p63, a p53 homolog at 3q27-29, encodes multiple products with transactivating, death-inducing, and dominant-negative activities. Mol. Cell 2, 305-316 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80275-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A., Schweitzer R., Sun D., Kaghad M., Walker N., Bronson R. T., Tabin C., Sharpe A., Caput D., Crum C. et al. (1999). p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature 398, 714-718 10.1038/19539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A., Zhu Z., Kapranov P., McKeon F., Church G. M., Gingeras T. R. and Struhl K. (2006). Relationships between p63 binding, DNA sequence, transcription activity, and biological function in human cells. Mol. Cell 24, 593-602 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng S. X., Dai M.-S., Keller D. M. and Lu H. (2002). SSRP1 functions as a co-activator of the transcriptional activator p63. EMBO J. 21, 5487-5497 10.1093/emboj/cdf540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Yan W. and Chen X. (2014). P63 regulates tubular formation via epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene 33, 1548-1557 10.1038/onc.2013.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.