Abstract

The neural crest is a stem/progenitor cell population that contributes to a wide variety of derivatives, including sensory and autonomic ganglia, cartilage and bone of the face and pigment cells of the skin. Unique to vertebrate embryos, it has served as an excellent model system for the study of cell behavior and identity owing to its multipotency, motility and ability to form a broad array of cell types. Neural crest development is thought to be controlled by a suite of transcriptional and epigenetic inputs arranged hierarchically in a gene regulatory network. Here, we examine neural crest development from a gene regulatory perspective and discuss how the underlying genetic circuitry results in the features that define this unique cell population.

Keywords: Gene regulation, Migration, Neural crest, Neural plate border, Signaling, Transcription factors

Summary: The current status of the neural crest gene regulatory network is reviewed, emphasizing the connections between transcription factors, signalling molecules and epigenetic modifiers.

Introduction

The neural crest is a remarkable cell type, notable for its ability to migrate extensively and differentiate into numerous derivatives (Fig. 1A-E). An evolutionary innovation, the neural crest is thought to have been crucial for the origin and diversification of vertebrates (Gans and Northcutt, 1983). It has been a subject of great interest to embryologists due to its far-reaching migratory ability and developmental plasticity, and is sometimes referred to as the ‘fourth germ layer’ (Hall, 2000). Discovery of the neural crest challenged important concepts pertaining to the development and evolution of the vertebrate body plan, especially when it was revealed that this ectodermal cell type could give rise to mesenchymal derivatives (Hall, 1999). Furthermore, identification of the neural crest demonstrated that the establishment of progenitor fields during body part formation could include contributions from cells incoming from distant locations.

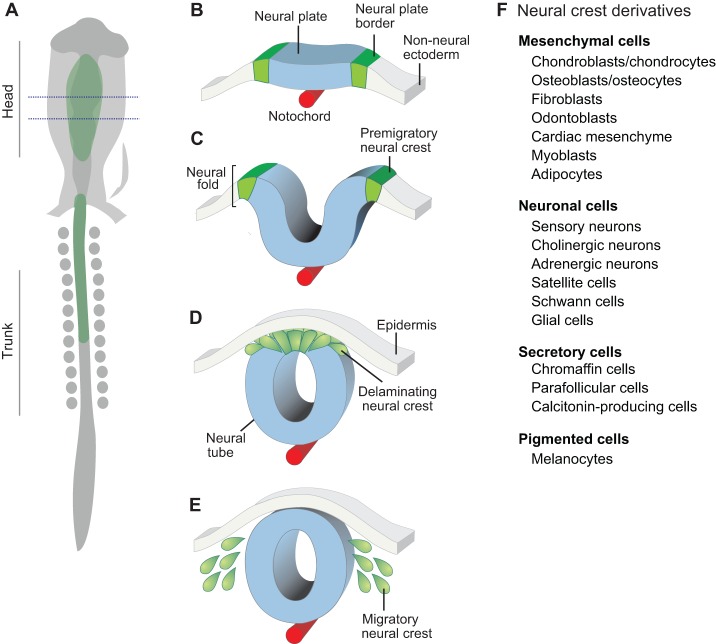

Fig. 1.

The neural crest is a multipotent cell population. (A) Schematic dorsal view of a ten-somite stage chicken embryo, showing the neural crest (green) in the vicinity of the midline. The dotted lines delimit the embryonic region represented in cross-section (B-E). (B) Development of the neural crest begins at the gastrula stage, with the specification of the neural plate border at the edges of the neural plate. (C) As the neural plate closes to form the neural tube, the neural crest progenitors are specified in the dorsal part of the neural folds. (D) After specification, the neural crest cells undergo EMT and delaminate from the neural tube. (E) Migratory neural crest cells follow stereotypical pathways to diverse destinations, where they will give rise to distinct derivatives. (F) The neural crest is multipotent and has the capacity to give rise to diverse cell types, including cells of mesenchymal, neuronal, secretory and pigmented identity.

Over the past century, much has been learned through experimental embryology about neural crest cell plasticity and its contribution to various derivatives (Le Douarin and Kalcheim, 1999). Transplantation experiments, first in amphibian embryos (Horstadius, 1950) and later in birds using the now classic quail-chick chimeras pioneered by Le Douarin (1973), have established the pathways followed by neural crest cells and the extensive array of derivatives to which they contribute (Fig. 1F). These studies have made the neural crest one of the best-studied progenitor cell populations of vertebrate embryos.

In this Review, we first provide a brief overview of neural crest development (for further details, see Le Douarin, 1982; Sauka-Spengler and Bronner-Fraser, 2008). We then describe the current state of knowledge regarding connections within the neural crest gene regulatory network (GRN), elaborating upon novel regulatory interactions that have been characterized in the last few years. We compile information obtained from several studies and model organisms to sketch regulatory circuits controlling the different steps of neural crest development using the BioTapestry platform (Longabaugh et al., 2005, 2009) and discuss the importance of epigenetic regulation in neural crest formation. Most interactions presented in this version of the GRN were characterized in the cranial neural crest, although we have also included information from other axial levels when it is consistent with network topology. In particular, we emphasize the data regarding direct interactions obtained from cis-regulatory analysis, which allow in-depth characterization of the circuitry within the network.

A brief overview of neural crest development

Neural crest cells are induced in the ectodermal germ layer during gastrulation and initially reside in the neural plate border territory, which is positioned at the lateral edges of the central nervous system (Fig. 1B). During neurulation, this border territory elevates as the neural plate closes to form the neural tube (Fig. 1C,D). As a consequence, nascent neural crest cells come to reside within the dorsal aspect of the apposing neural folds, initiating the expression of neural crest genes, such as FoxD3 (Labosky and Kaestner, 1998) and Sox10 (Southard-Smith et al., 1998), that reflect their specification as bona fide neural crest cells. After neural tube closure/cavitation, they subsequently leave the central nervous system via an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Fig. 1D), resulting in their transformation into a migratory and multipotent progenitor cell population (Fig. 1E) that undergoes some of the most far-reaching migrations of any embryonic cell type, often moving long distances along highly stereotypic pathways.

Following migration, neural crest cells progressively differentiate into distinct cell types according to environmental influences encountered during their journey and at their final sites, where they cooperate with other cell populations to form appropriate tissues and organs (Bronner and LeDouarin, 2012). They generate a multitude of derivatives as diverse as elements of the craniofacial skeleton, sensory and autonomic ganglia of the peripheral nervous system, and pigment cells of the skin (Le Douarin, 1982) (Fig. 1F). Thus, vertebrate neural crest cells are defined by their origin at the neural plate border, their ability to leave the neural tube via EMT and their multipotency.

Cell lineage-tracing experiments have identified the derivatives and pathways of migration of various neural crest populations (Le Douarin, 1982). The regionalization of the body axis from anterior to posterior is reflected by neural crest subpopulations that contribute to some overlapping as well as axial level-specific derivatives. For example, cranial neural crest cells form the facial skeleton, including the upper and lower jaw and bones of the neck, as well as the glia and some neurons of the cranial sensory ganglia (Couly et al., 1998). Just below the head, vagal neural crest cells populate the outflow tract of the heart and enteric ganglia of the gut (Le Douarin and Teillet, 1973; Creazzo et al., 1998). The trunk neural crest contributes to the dorsal root and sympathetic ganglia of the peripheral nervous system (Le Douarin and Smith, 1988), migrating in a segmental pattern through the somites. However, trunk crest normally lacks the ability to form cartilage/bone or contribute to the cardiovascular system – as possessed by more anterior populations (Le Lievre and Le Douarin, 1975; Le Lievre et al., 1980). Pigment cells of the skin and peripheral glia arise from neural crest cells at all axial levels (Le Douarin, 1982).

The neural crest gene regulatory network

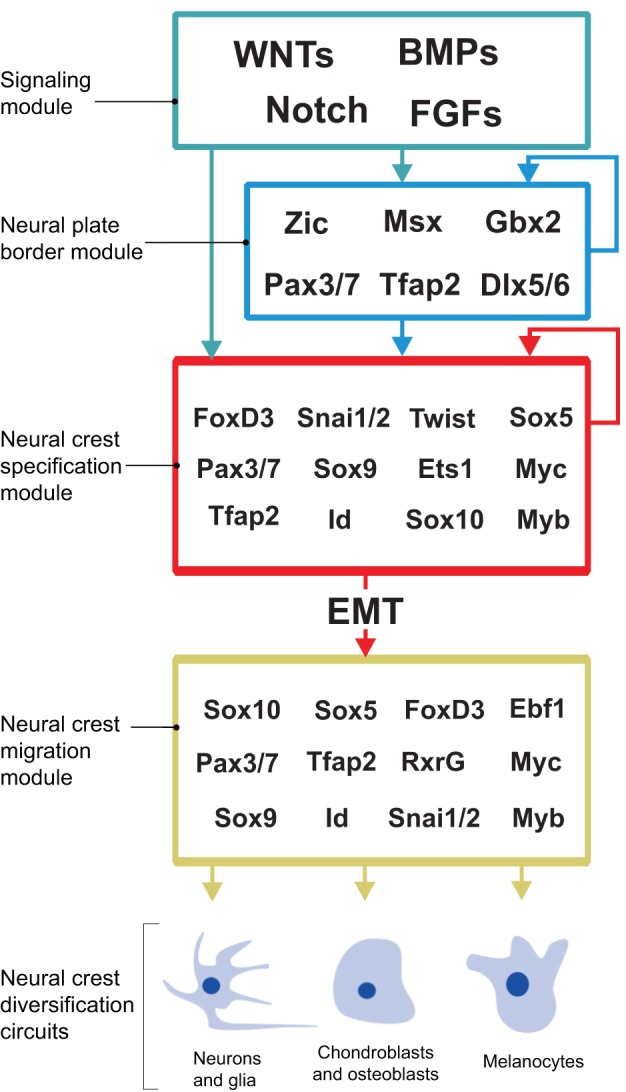

Advances in molecular biology in the last two decades have greatly elaborated our knowledge of the genetic control of different events in neural crest development (Simoes-Costa and Bronner, 2013). Numerous studies have resulted in the identification of many transcription factors important for neural crest formation, as well as some of the regulatory links between these regulators. The regulatory information obtained from different vertebrate model organisms has led to the concept of a neural crest GRN that underlies the process of neural crest formation (Meulemans and Bronner-Fraser, 2002; Betancur et al., 2010b) (Fig. 2). According to this model, the neural plate border is established by the combined action of distinct signaling pathways. The output of these signaling pathways, together with transcription factors expressed at the neural plate border, then establishes a novel regulatory state that sets apart presumptive neural crest cells from the other ectodermal domains. This process, which is known as neural crest specification, culminates in the expression of bona fide neural crest markers such as FoxD3, Snai1/2 and Sox8/9/10. Once the neural crest is specified, it undergoes radical gene regulatory changes that enable these cells to engage in EMT and initiate migratory behavior and diversification. In the following sections, we discuss the GRN at each stage of neural crest development, from the earliest specification through to the final differentiation of neural crest derivatives.

Fig. 2.

A GRN controls neural crest formation. Outline of the GRN controlling neural crest development. Different inductive signals pattern the embryonic ectoderm and induce the expression of neural plate border specifier genes, which define the neural plate border territory. These genes engage in mutual positive regulation and also drive neural crest specification by activating the neural crest specifier genes. The neural crest specification program results in the activation of the EMT machinery that allows the neural crest cells to become migratory. The migratory neural crest cells express a set of regulators that endow them with motility and the ability to initiate different differentiation programs.

Induction and formation of the neural plate border

Initiation of neural crest development occurs during gastrulation and results in establishment of the neural plate border, which is a broad territory between the future neural and epidermal domains. The neural plate border contains a multi-progenitor cell population that is capable of giving rise to neural crest cells (Meulemans and Bronner-Fraser, 2002; Sauka-Spengler and Bronner-Fraser, 2008) (Fig. 3A) as well as ectodermal placodes, epidermal cells, roof plate cells and sensory neurons of the central nervous system (Groves and LaBonne, 2014). Formation of the neural plate border is closely linked to neural induction, presumably relying upon the same signals. Although there are some differences between species in the details of the neural crest induction process, a general model has emerged from observations of frog, chick and zebrafish that appears to hold true, at least broadly, across vertebrates.

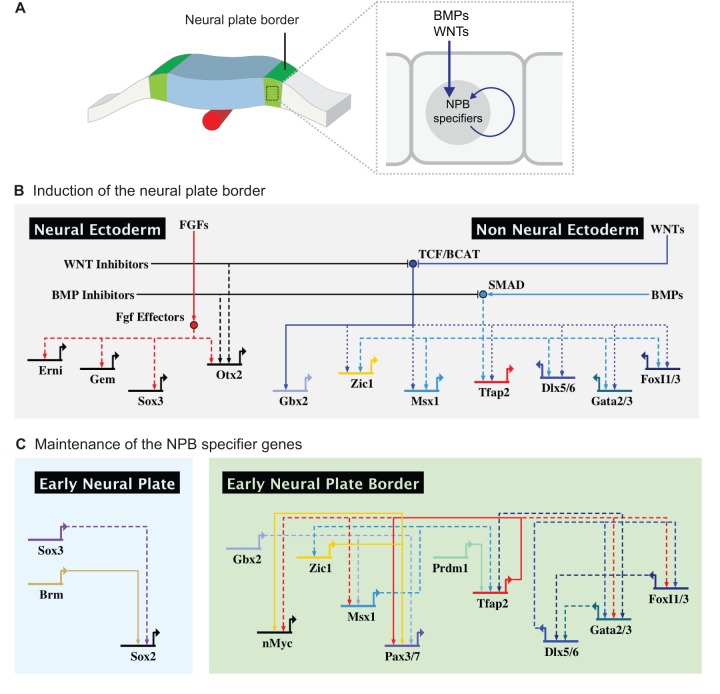

Fig. 3.

GRN module controlling the formation of the neural plate border. (A) The action of signaling systems such the BMP and WNT signaling pathways results in activation of the neural plate border (NPB) genes in the margins of the neural plate. (B) In the neural ectoderm, FGF signaling drives neural induction by activating proneural genes. In an intermediary territory located between the neural and non-neural ectoderm, WNTs and BMPs activate a number of transcription factors dubbed neural plate border specifiers. Activity of WNTs and BMPs is hampered in the neural ectoderm by a number of inhibitory molecules produced by these cells. (C) While SoxB1 genes (Sox2 and Sox3) are expressed in the early neural plate, the neural plate specifier transcription factors engage in mutual positive regulation, which stabilizes the neural plate border regulatory state. Direct interactions are indicated with solid lines, whereas dashed lines show possible direct interactions inferred from gain- and loss-of-function studies.

Three important steps, as discussed in detail below, are involved. First, signaling pathways are thought to drive the expression of a set of genes known as neural plate border specifier genes. These genes are initially expressed in broad domains that include portions of the neural plate or prospective epidermis. Subsequently, a series of positive regulatory interactions results in the establishment of a robust domain comprising the overlapping expression of neural plate border specifier genes (Fig. 3B). Finally, further refinement is accomplished by inhibitory interactions between neural and non-neural transcription factors, which sharpen the boundaries between these territories and result in the emergence of a progenitor domain endowed with a regulatory state that is distinct from those in either the neural plate or non-neural ectoderm.

The first of these regulatory steps occurs during the process of neural induction, when FGFs work in concert with BMP and WNT inhibitors to activate the expression of neural genes such as Erni, Otx2 and Sox1/3 (Fig. 3B) (Streit et al., 2000). WNT and BMP signals originate in lateral regions of the embryo, while inhibitors of these pathways are secreted from medial regions such as the neural plate domain. A balance between these activating and inhibitory signals generates a mediolateral gradient of WNT and BMP activity (Fig. 3B), such that the future neural plate border cells originate within a zone exposed to intermediate levels of WNT and BMP activity (reviewed by Groves and LaBonne, 2014). FGFs – secreted by the underlying hypoblast in chick, mesoderm in frog, or lateral plate in zebrafish – and Notch signaling may also participate in defining the neural plate border (Endo et al., 2002; Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003; Yardley and Garcia-Castro, 2012). Although the exact sources of these signals and inhibitors varies somewhat between species, the overall picture is that the combined action of these signaling events results in induction of the neural plate border domain.

Although cis-regulatory studies of early neural plate border genes are scarce, some of these interactions have been shown to be direct. For instance, X. laevis Gbx2 is directly activated by β-catenin through a proximal enhancer 500 bp upstream of the transcription start site (Li et al., 2009). Recent work by Garnett and colleagues (Garnett et al., 2012) in zebrafish has shed light on how such signals are interpreted by the cis-regulatory apparatus of neural plate border genes. The authors show that expression of zic3 and pax3a (one of the zebrafish Pax3/7 orthologs) depends on multiple enhancers that respond differentially to BMP, WNT and FGFs. The concerted activation of such regulatory elements results in robust endogenous expression in a domain between the neural and non-neural ectoderm (Garnett et al., 2012). It is important to highlight that expression of the neural plate border genes is not uniform, as some of the specifier genes are expressed in more medial domains, whereas others are expressed more laterally. For instance, Zic1 is also expressed in the neural plate and plays a role in neural induction (Marchal et al., 2009; Aruga, 2004), whereas Tfap2a remains active in the prospective epidermis (Luo et al., 2002, 2003; Li and Cornell, 2007). Such asymmetries are likely to have important implications at subsequent stages, when the neural plate border becomes segregated into the premigratory neural crest and preplacodal domains. Consistent with this, the relative expression levels of neural plate border specifier genes influence the cell fates adopted by this progenitor population (Hong and Saint-Jeannet, 2007).

Following reception of these intersecting signaling events, the neural plate border cells turn on expression of a distinct new set of transcription factors, while maintaining others originally characteristic of either neural plate or non-neural ectoderm. These genes, which are termed neural plate border specifiers, are initially transcribed in the early gastrula and include Tfap2, Msx1, Zic1, Gbx2, Pax3/7, Dlx5/6, Gata2/3, Foxi1/2 and Hairy2 (Meulemans and Bronner-Fraser, 2004; Nichane et al., 2008; Khudyakov and Bronner-Fraser, 2009) (Fig. 3B). Studies in multiple vertebrates have shown that, once their expression commences in the neural plate border region, these transcription factors engage in a series of mutual cross-regulatory interactions that lead to the stabilization of this regulatory state (Fig. 3C) and ensure their continued expression (Monsoro-Burq et al., 2005; Sato et al., 2005; Nikitina et al., 2008; Bhat et al., 2013).

Owing to its slow development, the lamprey embryo has proven to be a useful model for the identification of interactions between these early genes at the neural plate border, and such studies also suggest that this is an ancient circuit that is functionally conserved across vertebrates. For instance, Nikitina and colleagues showed that Tfap2a and Msx1 activate not only each other, but also Zic1 and Pax3/7 (Nikitina et al., 2008). Tfap2a seems to be a key activator of neural plate border specifiers, also being required for the expression of Foxi genes and gata2/3 in zebrafish (Bhat et al., 2013). The more lateral neural plate border genes (Dlx5/6, Gata2/3 and Foxi1/3) also positively regulate each other in multiple positive regulatory loops (McLarren et al., 2003; Matsuo-Takasaki et al., 2005; Kwon et al., 2010; reviewed by Grocott et al., 2012). Such interactions lock down the regulatory state and allow for the maintenance of expression of neural plate border specifiers, which are often retained in the developing progenitors through later stages of development.

Finally, the boundary between the neural plate and the neural plate border is sharpened by inhibitory interactions between neural and non-neural transcription factors (Fig. 3B). For example, misexpression of several of the neural plate border genes (Tfap2a, Dlx5/6, Msx1, Foxi1/3) in the neural plate results in loss of the neural specifiers Sox2/3, while knockdown of the same genes causes expansion of the neural domain (Feledy et al., 1999; Luo et al., 2001; Matsuo-Takasaki et al., 2005; Pieper et al., 2012). Moreover, overexpression of Sox2/3 results in loss of neural crest and epidermal markers, suggesting that neural factors can also repress neural plate border specifiers (Wakamatsu et al., 2004; Rogers et al., 2009). Thus, the cis-regulatory interactions between neural genes and neural plate border specifiers result in a sharp boundary that will separate neural crest from central nervous system progenitors (Fig. 3C).

Establishing neural crest identity: the neural crest specifier genes

The emergence of the neural crest from the neural plate border is marked by the expression of a suite of genes dubbed neural crest specifiers. Their expression is driven by the concerted action of more medial neural plate border specifiers and signaling pathways that are active during the time of specification (Fig. 4). The neural crest specifiers have key functions. They activate the EMT effector program, which will allow the neural crest to delaminate from the ectoderm and become a migratory cell type (as discussed further below). Moreover, they also regulate each other positively to stabilize this regulatory state, which results in the maintenance of a number of specifier genes in the delaminating and migratory neural crest. This is important, as the combination of these transcription factors is thought to maintain the neural crest in an undifferentiated state (Sauka-Spengler and Bronner-Fraser, 2008). In fact, the plasticity and developmental potential of the neural crest is likely to be encoded in the gene regulatory circuits that characterize this population.

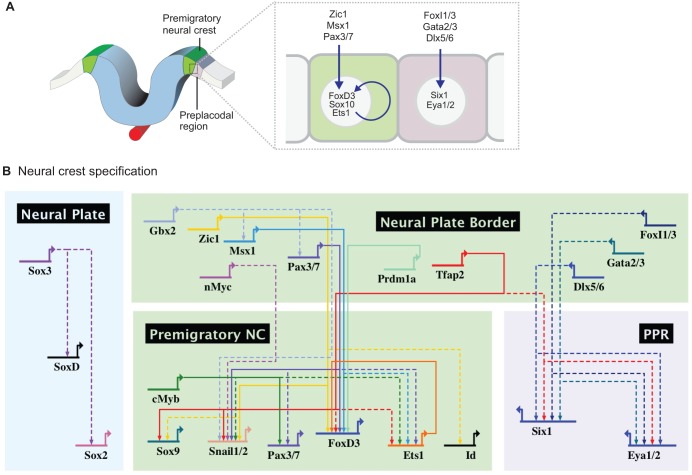

Fig. 4.

Gene regulatory interactions controlling specification of the neural crest. (A) As the neural plate folds, the neural plate border specifier genes Zic1, Msx1 and Pax3/7 activate the expression of neural crest specifier genes FoxD3, Sox10 and Ets1. Lateral to the neural crest cells, preplacodal cells express a distinct set of transcription factors. (B) Expression of neural crest specifiers in the premigratory neural crest (NC) territory is mediated by regulators in the medial regions of the neural plate border. The neighboring preplacodal region (PPR) is defined by expression of Six1 and Eye1/2, which identify the progenitor field that will give rise to cranial placodes. SoxD and SoxB1 genes are expressed in the neural plate.

The first neural crest specifiers to be expressed in the nascent neural crest in the chick are FoxD3, Ets1 and Snai1/2 (Khudyakov and Bronner-Fraser, 2009). Neural crest expression of FoxD3 is regulated by the neural plate border specifiers Pax3/7 and Msx1, which directly bind to two regulatory regions that drive differential expression in the cranial and trunk neural crest cells of the chick embryo (Simoes-Costa et al., 2012). Moreover, Pax3/7 and Msx1 are also required for the expression of Ets1 (Barembaum and Bronner, 2013), highlighting their importance during the early steps of neural crest specification. Similarly, Pax3/7 has also been shown to cooperate with Zic1 to drive neural crest specification in frog embryos (Bae et al., 2014; Plouhinec et al., 2014). In X. laevis, for example, Zic1 together with Pax3/7 (Milet et al., 2013) bind directly to the Snai1 and Snai2 promoters (Plouhinec et al., 2014). They also directly regulate FoxD3 expression in the chick trunk neural crest (Simoes-Costa et al., 2014). Furthermore, experiments in the lamprey suggest that the requirement of Pax3/7, Msx1 and Zic1 in neural crest specification is evolutionarily conserved, as the knockdown of these three neural plate border specifiers results in loss of both FoxD and SoxE1 expression (Sauka-Spengler et al., 2007). Taken together, these results suggest that Pax3/7, Msx1 and Zic1 are crucial genes for the acquisition of neural crest identity, and directly activate a number of neural crest specifier genes in multiple species (Fig. 4B).

Recently, genome-wide profiling of active enhancers in neural crest cells obtained from human embryonic stem cells indicated that TFAP2A acts as a general regulator of neural crest specifier genes, in conjunction with the nuclear receptors NR2F1 and NR2F2 (Rada-Iglesias et al., 2012). According to this study, occupation of neural crest enhancers by these three regulators leads to the establishment of permissive chromatin states, which are necessary for activating gene expression. This is consistent with functional studies showing that Tfap2a is required for neural crest specification in zebrafish, frog and chick (Schorle et al., 1996; de Croze et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011b), as well as data demonstrating a role for Tfap2a during neural crest specification that is independent from its earlier function in the establishment of the neural plate border (de Croze et al., 2011). Thus, it is possible that Tfap2a acts as a pioneer transcription factor in the process of neural specification, reorganizing chromatin conformation to provide access of other transcriptional regulators to cis-regulatory elements. According to this hypothesis, Tfap2a may allow other neural plate border specifiers, such as Msx1, Pax3/7 and Zic1, to access the enhancers that control the expression of the neural crest specifier genes.

Concomitantly, the preplacodal region is established lateral to the neural crest domain by the expression of the key placodal regulators Six1, Eya1/2 and Irx1. These genes are activated by lateral neural plate border specifiers (Foxi1/3, Gata2/3 and Dlx5/6) (Fig. 4), which in turn regulate a number of transcription factors resulting in specification of the ectodermal placodes (Grocott et al., 2012; Sato et al., 2010). Similar to events observed at the neural/non-neural border, neural crest and preplacodal genes engage in a number of inhibitory interactions, which operate to molecularly segregate these two populations. For instance, in X. laevis Pax3/7 and Msx1 repress the transcription of Six1 (Sato et al., 2010), while Six1 and Eya1/2 repress Msx1, Pax3/7 and FoxD3 (McLarren et al., 2003; Brugmann et al., 2004; Christophorou et al., 2009) in both chicken and frog. Interestingly, although molecular markers suggest a clear division between the neural crest and preplacodal domains, fate-mapping experiments indicate that these two progenitor cell types are still largely intermingled. Labeling of individual cells in the late neural plate border reveals that individual progenitor cells can give rise to both neural crest and ectodermal cells (Selleck and Bronner-Fraser, 1995), showing that, despite their expression of specifier genes, the fate of these cells is not yet fixed.

Nevertheless, it is clear that the regulatory program of the neural plate border cells operates to distinguish these cell types from its onset: from the earliest stages, the key neural crest regulators are more medially located relative to the placodal regulators, and interactions between them might already be delineating the segregation of neural crest and preplacodal domains. According to this view, the mediolateral compartmentalization of the vertebrate ectoderm would operate in a manner similar to the Drosophila gap gene GRN (Jaeger, 2011): morphogens polarize and divide the ectoderm into broad territories, activating genes that will engage in multiple cross-regulatory interactions, resulting in the progressive restriction and delimitation of territories of cells sharing similar regulatory states.

The importance of Msx1, Pax7 and Zic1 in neural crest formation is clear, but other genes expressed in the neural plate border, such as Myb, Myc and Prdm1a (Bellmeyer et al., 2003; Betancur et al., 2010b; Powell et al., 2013), have also been implicated in neural crest specification. Furthermore, signaling input seems to be important for the expression of neural crest specifier genes. Inhibition of WNT signaling after neural plate border specification results in loss of expression of Snai2 and FoxD3 (Garcia-Castro et al., 2002) in chick embryos, while WNTs have been shown to act in concert with Zic1 and Pax3 to drive neural crest specification in the frog (Sato et al., 2005). This raises the interesting possibility that WNTs could act as permissive factors in neural crest specification. However, cis-regulatory analysis has failed to uncover many direct TCF/LEF binding sites that are crucial for neural crest specifier expression (Betancur et al., 2010b; Barembaum and Bronner, 2013; Simoes-Costa and Bronner, 2013). The exception seems to be Snai2, which has a proximal enhancer that is directly activated by TCF/LEF and β-catenin (Vallin et al., 2001). Thus, although WNTs are thought to play an important role in neural crest specification, the direct underlying mechanism of how this is mediated remains unclear. An intriguing possibility is that factors downstream of signaling systems cooperate with transcription factors at the neural plate border to mediate neural crest specification.

Much like the neural plate border specifier genes, the neural crest specifier genes positively cross-regulate each other. Such interactions are difficult to parse out given that they take place in a short period of time as the cells quickly transition to the next regulatory state (Nikitina et al., 2008). A few examples of direct regulatory interactions between neural crest specifier genes include the cranial-specific control of FoxD3 by Ets1 (Simoes-Costa et al., 2012). Nevertheless, it is clear that positive regulatory loops result in the consolidation of the neural crest specifier regulatory state. For instance, in the frog, Snai1/2 seems to positively regulate Twist, FoxD3 and Sox9 (Aybar et al., 2003), while Foxd3 promotes Sox10 expression in mouse (Dottori et al., 2001). Sox10, on the other hand, has been shown to activate Snai2 and itself (Honoré et al., 2003), while Sox8 is important for the expression of other SoxE genes in the same model in the frog (O'Donnell et al., 2006). Characterization of more direct interactions in multiple species will be necessary to delineate the hierarchy and logic controlling the expression of these transcription factors.

The process of neural crest specification results in a discrete cell population, located between the neural plate and the preplacodal region, that shares a common regulatory state. At these stages, the premigratory neural crest expresses the full suite of specifier genes (including FoxD3, Snai2, Ets1, Sox8/9/10 and Pax3/7) as well as some of the border genes whose expression is maintained (Tfap2, Msx1, Zic1). This new regulatory state initiates drastic structural changes at a cellular level that result in delamination from the neural tube via EMT.

Transcriptional control of the neural crest EMT program

After the neural crest cells are specified, they delaminate from the neural tube to commence migration (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the same transcriptional regulators that establish neural crest identity are also part of the molecular machinery that drives EMT, indicating that neural crest cell identity and behavior are, at least in part, interlinked. EMT is a complicated process, as the structural remodeling that takes place in the premigratory neural crest involves the precise control of hundreds of effector genes. Furthermore, signaling pathways such as WNT signaling are also thought to be involved in EMT, especially through transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of Snai1/2 (Vallin et al., 2001; Yook et al., 2006). Most of the work on neural crest EMT has focused on the adhesive changes that enable cells to delaminate. These studies indicate that a major driver of EMT is the direct repression by neural crest specifier genes of structural genes involved in maintenance of the epithelial state (Fig. 5B).

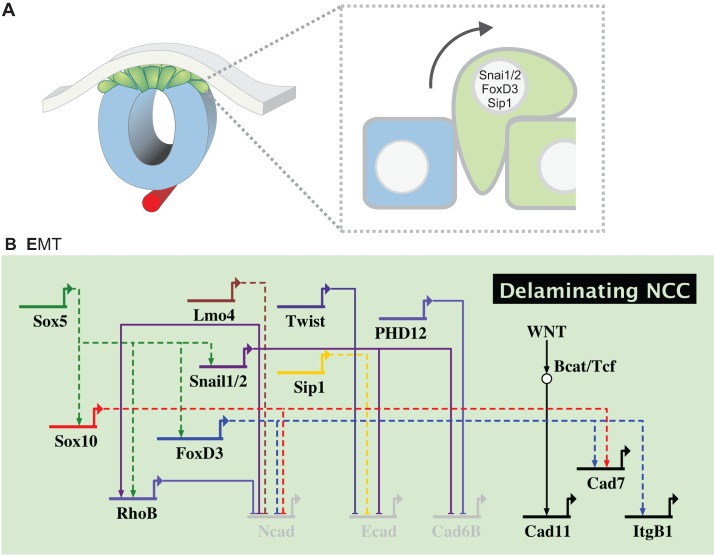

Fig. 5.

Regulatory module responsible for neural crest EMT. Activity of Snai1/2, FoxD3, Twist and Zeb2 (Sip1) mediate changes in cell-cell interaction that allow for delamination and dispersion of neural crest cells (NCC). Repression of the epithelial cadherins Ncad, Ecad and Cad6b and activation of the type 2 cadherins Cad11 and Cad7 allow for changes in cell adhesion and EMT.

The process of EMT involves cell surface changes that result in the dissolution of adherens junctions, allowing the segregation of the premigratory neural crest into individual cells. Transcriptional regulation of cadherins is thought to be central to this process. Studies in chick have shown that delamination of the cranial neural crest requires a switch between type 1 cadherins [such as cadherin 1 (Ecad) and cadherin 2 (Ncad)] and type 2 cadherins (Cad7 and Cad11). Since type 1 cadherins mediate stronger cell-cell interactions and thus are important for epithelial stabilization, they must be downregulated and replaced by type 2 cadherins in migratory cells. Although cadherins are modulated upon EMT in all model organisms, there are important species-specific differences in terms of which cadherins are used. For instance, Ncad remains essential for cranial neural crest delamination and migration in the frog (Vallin et al., 1998; Kashef et al., 2009). A number of neural crest specifier genes are thought to participate in regulating cadherins during EMT. For example, Sox10 seems to repress Ncad in chick migratory cells (Cheung et al., 2005). Furthermore, overexpression of FoxD3 results in downregulation of Ncad and upregulation of Cad7 (Dottori et al., 2001; Cheung et al., 2005) in chicken embryos, although it is not yet clear if these interactions are direct. FoxD3 is also involved in the repression of Tspan18, a transmembrane protein that promotes cadherin-dependent cell adhesion and prevents neural crest delamination (Fairchild and Gammill, 2013). Control of cadherin availability also relies on other means of regulation. For instance, the levels of Ncad associated with the neural crest cell membrane are tightly regulated by protein internalization mediated by lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) receptor 2. Activation of the LPA pathway reduces membrane Ncad, increasing tissue fluidity and allowing cells to engage in collective cell migration (Kuriyama et al., 2014).

Since its discovery, Snai1/2 has been linked to EMT in many systems, from cancer cell lines to gastrulating embryos (Nieto et al., 1994; Blanco et al., 2007). In the neural crest, Snai1/2 functions as a transcriptional repressor and plays an important role in the downregulation of the type 1 cadherins during EMT. It has an important role in Ncad repression, where it cooperates with Lmo4 to inhibit transcription in both the neural crest and in cancer cells (Ferronha et al., 2013). Importantly, Snai1/2 also represses Cad6b (Taneyhill et al., 2007), a classical type 2 cadherin that needs to be downregulated for neural crest delamination to occur (Coles et al., 2007). This is accomplished through direct interaction with a pair of E-box sites located in the vicinity of the Kozak consensus sequence. An important partner of Snai1/2 during the process of EMT is the transcription factor Sox9, which when phosphorylated physically interacts with Snai1/2 to drive EMT (Cheung and Briscoe, 2003; Liu et al., 2013b).

The two steps of EMT, namely delamination and cell dispersion, seem to be partially uncoupled in neural crest development. In X. laevis, cranial crest cells detach from the neural tube as a group and will only become truly mesenchymal at later stages when they commence migration (Theveneau et al., 2010). The dissociation of neural crest cells is mediated in part by Twist, which represses Ecad in the delaminating cells. Knockdown of Twist and its regulator Hif1α result in upregulation of Ecad and inhibition of cell dispersion (Barriga et al., 2013). In contrast to the frog, Twist is not expressed in the neural crest of amniotes during premigratory or migratory stages, and effects of Twist knockout on early neural crest development appear to be secondary to mesodermal effects (Chen and Behringer, 1995). This suggests that other transcriptional regulators may exist in amniotes to help mediate EMT.

One such factor appears to be the transcriptional regulator Zeb2 (also known as Sip1), which like Snai1/2 appears to act as a repressor. In chick, knockdown of Zeb2 results in maintenance of Ecad, which is normally repressed in migratory neural crest cells. This misregulation of Ecad does not prevent delamination from the neural tube but rather results in aggregates of adherent neural crest cells in the vicinity of the neural tube (Rogers et al., 2013). Thus, while repression of Cad6b is required for loss of adhesion between the neural crest population and the neural tube, Ecad mediates cell-cell adhesion between the neural crest cells themselves, and its repression, driven by Twist and/or Zeb2, is necessary for neural crest dissociation. Taken together, these findings suggest that neural crest EMT is a two-step process, with the first resulting in neural crest delamination from the neural tube, and the second involving their acquisition of mesenchymal properties and migratory morphology. The delamination process appears to involve repression of Cad6b by Snai2, which allows neural crest cells to leave the neural tube. The cell dispersion step involves repression of Ecad by Zeb2 and/or Twist, which allows separation of the neural crest into individual migratory cells.

In addition to the modulation of adhesion, other structural changes are necessary to allow for delamination and dispersion of the migratory cells. These include degradation of the basement membrane by metalloproteases, favoring cell invasion (Theveneau and Mayor, 2011). Evidence for the transcriptional control of these events is scarce, although Zeb2 and Snai1/2 are likely regulators of ADAM proteins and matrix metalloproteinases in the neural crest, given their well-established roles in basement membrane degradation in other contexts (Joseph et al., 2009). Furthermore, changes in cytoskeletal organization, which involve the polymerization of actin into microfilaments and their attachment to the cell membrane, are fundamental to cell dispersion (Yilmaz and Christofori, 2009). These events might be mediated partly by RhoGTPases, which have an important role in controlling actin dynamics (Liu and Jessell, 1998; Sit and Manser, 2011) and thus are likely to be involved in the cell shape changes necessary for EMT. RhoB is strongly expressed in the neural crest in chick, and it seems to be transcriptionally activated by Sox5, a member of the SoxD family that is also required for expression of the neural crest specifiers Snai1/2, FoxD3 and Sox10 (Perez-Alcala et al., 2004). Although there has been some controversy as to the role of RhoGTPases in EMT (Fort and Theveneau, 2014), they seem to be essential for neural crest cell detachment (Clay and Halloran, 2013) and might also impact neural crest specification by modulating the expression of neural crest genes (Guemar et al., 2007). Additional studies are necessary to elucidate how the regulatory machinery involved in specification orchestrates cytoskeletal reorganization as neural crest cells leave the neural tube and acquire migratory behavior.

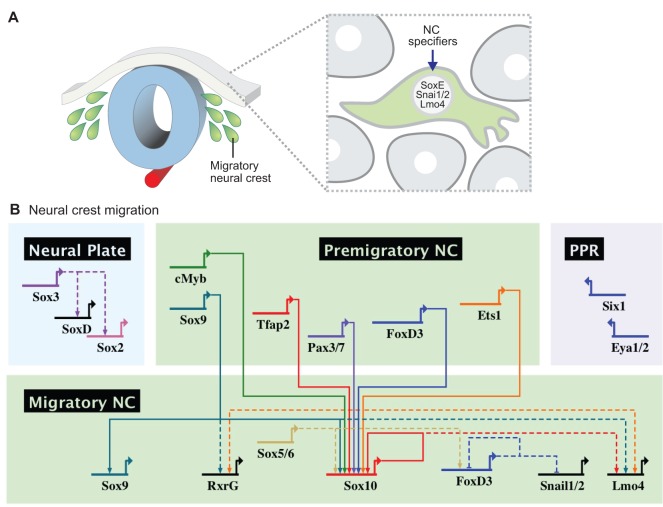

Regulatory interactions in the migratory neural crest

After delamination, migrating neural crest cells assume a novel regulatory state, expressing a number of transcription factors important for cell migration and for initiating the differentiation programs that will lead to distinct derivatives (Fig. 6A). The expression of several neural crest specifier genes, such as FoxD3, Ets1 and Sox8/9/10, is retained in some or all migratory cells (Khudyakov and Bronner-Fraser, 2009; Betancur et al., 2010a). However, cis-regulatory analysis reveals important differences between the GRNs of the premigratory and migratory states. For instance, FoxD3 expression in the premigratory cranial neural crest is controlled by an early enhancer, NC1, which initiates FoxD3 expression in the newly closed cranial neural tube but quickly shuts down as cells delaminate (Simoes-Costa et al., 2012). Maintenance of FoxD3 expression in migratory cells is accomplished by the activation of a different enhancer (NC2) (Simoes-Costa et al., 2012) that requires distinct regulatory inputs. Thus, even though premigratory and migratory cells share a number of transcription factors, the programs underlying the expression of the same regulator can vary greatly as a function of time.

Fig. 6.

Neural crest specifiers drive the transition to the migratory neural crest regulatory state. (A) Action of neural crest specifiers transforms the identity of the neural crest as it becomes a migratory cell population. (B) Neural crest specifiers (including Sox9, cMyb and Ets1) cooperate to drive the expression of genes that are strongly upregulated in the migratory neural crest, such as Sox10. This transcription factor positively regulates itself, which results in maintenance of Sox10 expression as the neural crest cells migrate throughout the embryo to give rise to different derivatives.

Migratory neural crest cells are complex from a regulatory viewpoint, as they are constantly exposed to different environmental signals and are also starting to differentiate into diverse derivatives. Surprisingly, only a few transcriptional regulators had been identified within the migratory neural crest regulatory hub, largely due to the fact that these cells intermingle with other cell types, making them difficult to isolate and characterize as a pure cell population. Recent transcriptome analysis of pure populations of Sox10+ migratory neural crest cells from chick (Simoes-Costa et al., 2014) has greatly expanded this dataset. This study identified ∼50 transcriptional regulators that are enriched in the migratory cranial neural crest when compared with the whole embryo (Simoes-Costa et al., 2014). This dataset provides a valuable resource, although the role of individual genes and how they fit in the neural crest GRN remains to be established.

Cis-regulatory analysis of genes within the neural crest migratory regulatory module suggests that the expression of these transcription factors is regulated by the neural crest specifier genes (Fig. 6B). For example, detailed analysis of the Sox10 genomic locus in chick revealed that its expression in the migratory neural crest is mediated by one of two enhancers, Sox10E2 and Sox10E1, which are active in the cranial and trunk crest, respectively. The cranial Sox10E2 enhancer is directly regulated by the neural crest specifier genes Myb, Ets1 and Sox9, which are sufficient to drive enhancer activity in naive ectoderm (Betancur et al., 2010b). These results are consistent with recent results that place Ets1 and Sox9 as crucial regulators of the migratory module of the cranial neural crest GRN. Knockdown of these transcription factors in chick embryos results in loss of several genes that are normally expressed by the cranial migratory crest, including Lmo4, RxrG and Ltk (Simoes-Costa et al., 2014). Remarkably, Ets1 seems to be a crucial regulator in the establishment of neural crest cephalic identity by mediating en masse delamination from the neural tube, resulting in the wave-like migration pattern observed in the cranial neural crest (Theveneau et al., 2007).

Cis-regulatory analysis of Sox10 in the mouse revealed that multiple enhancers, with semi-overlapping activity domains, seem to mediate the expression of this gene. These regulatory regions are controlled by Pax3/7, Tfap2a, Sox and LEF/TCF transcription factors (Werner et al., 2007). Furthermore, Sox10 was shown to directly regulate itself, consistent with its continuous expression in the migratory neural crest. This positive self-regulatory loop relies on synergistic activity with Tfap2a and FoxD3 (Wahlbuhl et al., 2012). That FoxD3 acts as a direct regulator of Sox10 in migratory cells is supported by another study that identified an intronic enhancer in the zebrafish sox10 locus, which contains FoxD3, Sox and LEF/TCF binding sites (Dutton et al., 2008). Sox9, another SoxE gene that is maintained throughout neural crest migration, has also been shown to directly activate its own transcription through a distant upstream enhancer in the mouse (Mead et al., 2013). Thus, positive self-regulation is a common feature of genes that are continuously expressed by the migratory neural crest. Extensive cis-regulatory studies of other migratory neural crest regulators will be necessary to clarify how the regulatory state of the neural crest cells evolves during migration and how it is influenced by external cues.

As expected, a number of signaling systems are involved in the guidance of neural crest migration and the establishment of the correct migratory pathways (Takahashi et al., 2013). There is scarce information on how these signaling molecules and receptors are controlled by the migratory neural crest GRN. Nevertheless, Sox10 seems to play a crucial role and has, for example, been shown to regulate the expression of neuregulin receptor Erbb3 (Britsch et al., 2001) through an intronic enhancer that is active in migratory neural crest cells (Prasad et al., 2011). Sox transcription factors have also been shown to regulate Robo receptors in other contexts (Samant et al., 2011). However, it is not yet clear how these signaling systems implicated in neural crest migration are controlled at the transcriptional level.

From a multipotent neural crest cell to distinct derivatives

As neural crest cells migrate and colonize different parts of the embryo, they transition from migratory streams to aggregates of cells within complex structures, often undergoing a process that is the reciprocal of EMT, termed mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET). They then contribute to neurons and glia of peripheral ganglia, cartilage condensations and many organs. This process is mediated by a gene regulatory program that compartmentalizes the neural crest progenitors into territories with distinct regulatory states. This has been beautifully illustrated by the profiling of craniofacial enhancers as performed by Attanasio and colleagues (Attanasio et al., 2013). In this study the authors identified more than 100 enhancers that are active in the neural crest-derived craniofacial skeleton, in remarkably diverse activity domains. Functional analysis through enhancer manipulation indicates that variation in craniofacial morphology, as well as craniofacial malformations, depend upon combined enhancer activity (Attanasio et al., 2013). Understanding how such regulatory complexity unfolds from the programs of neural crest specification and migration is a major challenge confronting neural crest biologists in years to come.

The process of neural crest diversification initiates with the activation of differentiation circuits in subpopulations of migratory cells. These circuits are centered around transcription factors expressed by the neural crest that activate lineage-specific gene batteries. Diversification into different derivatives depends upon the interplay between the regulatory state of the migratory neural crest cells and environmental cues, often conveyed by various signaling systems. Such environmental signals, particularly interactions with other tissues, are key players in determining the fate of the migratory cells (Takahashi et al., 2013). Here, we describe a subset of conserved regulatory circuits involved in neural crest cell differentiation, focusing on chondrocytes, melanocytes and neuronal cell types as examples (Fig. 7).

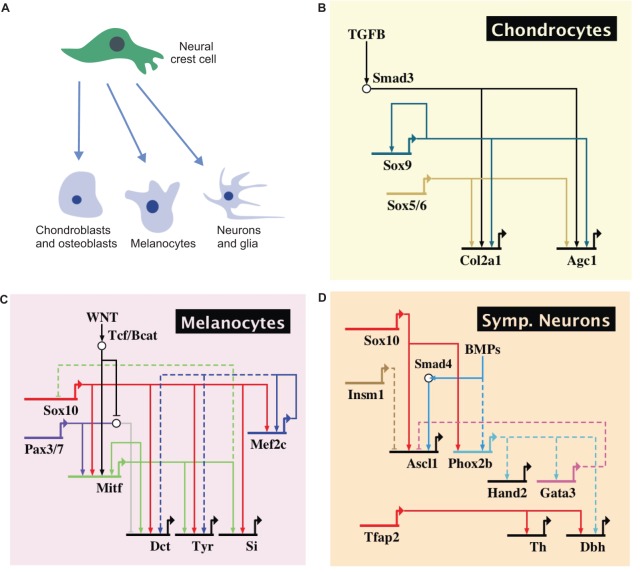

Fig. 7.

Subcircuits controlling neural crest diversification. (A) Neural crest cells give rise to distinct derivatives depending on their migratory pathways and external cues. (B) Differentiation of neural crest to chondrocytes depends on the activity of Sox9 and Sox5/6, which cooperate with TGFβ signaling to directly activate the cartilage differentiation genes Col2a1 and Agc1. (C) Differentiation to melanocytes is centered on a Sox10-Mitf feed-forward loop. These transcription factors cooperate to directly activate Dct, Tyr and Si, which encode melanogenic enzymes. (D) BMP signaling drives the differentiation of neural crest cells to sympathetic neurons through activation of Ascl1 and Phox2b, which in turn activate a circuit controlling differentiation genes such as tyrosine hydroxylase (Th) and dopamine β-hydroxylase (Dbh).

Chondrocytes

The cranial neural crest has a crucial role in establishment of the craniofacial skeleton, giving rise to the quadrate, Meckel's cartilage and surrounding membrane bones, cartilage of the tongue, and the membrane bones of the jaw and skull (Noden, 1983; Couly et al., 1996, 1998). As a consequence, this cell population is of exceptional medical importance, being affected in a large percentage of birth defects (Hall, 1999). Development of the craniofacial skeleton is a complicated process that involves multiple cell types and different kinds of ossification (Wilkie and Morriss-Kay, 2001). An important genetic circuit that mediates the differentiation of neural crest cells into chondrocytes revolves around the transcription factor Sox9, which is a direct regulator of several genes that are crucial for chondrocytic differentiation. Inactivation of Sox9 in the neural crest lineage results in severe craniofacial defects in mice (Mori-Akiyama et al., 2003). Sox9 is thought to cooperate with SoxD genes to activate downstream targets such as Col2a1 and Agc1 (also known as Acan). In the migratory cranial neural crest, Sox9 is regulated by WNT signaling and also has strong autoregulatory activity (Bagheri-Fam et al., 2006; Mead et al., 2013) (Fig. 7B).

Transcriptional control of Agc1, a marker for cartilage differentiation, illustrates how cartilage genes are regulated. In mice, an enhancer located 10 kb upstream of the transcription start site mediates reporter expression that recapitulates endogenous Agc1 expression. Sox9 binds to a critical site in this enhancer, but only in the presence of Sox5/6. These SoxC factors interact with three accessory binding sites that enhance expression of the reporter (Han and Lefebvre, 2008). A similar mode of regulation, relying on direct activation by Sox9 and SoxD genes, was observed for Col2a1 in mice (Bell et al., 1997; Lefebvre et al., 1998). Sox9-dependent activation of chondrogenic genes relies on recruitment of the histone acetyltransferase CBP/p300 (Tsuda et al., 2003), which is mediated by Smad3; this illustrates how the TGFβ pathway may function as a permissive signal during cartilage formation (Furumatsu et al., 2005). Both Sox9 and SoxD genes are also crucial for the survival of neural crest derivatives, as their loss causes massive apoptosis of these cells in chicken and mice (Cheung et al., 2005; Bhattaram et al., 2010). In soft tissues of the face, such as the tongue, Sox9 must be shut down in order to prevent cartilage formation. The transcription factor Osr1 mediates this repression by directly binding to the Sox9 promoter (Liu et al., 2013a), and its loss results in the formation of ectopic cartilage in the mouse tongue. Whereas Osr1 is expressed in the mouse tongue, it is absent from bird tongues; interestingly, the latter contain cartilaginous tissue. This illustrates how changes in the regulatory inputs of a gene could result in morphological changes during evolution (Liu et al., 2013a).

Melanocytes

Neural crest differentiation into melanocytes relies upon the action of transcription factors Sox10 and Pax3/7 as well as signaling systems such as WNTs, endothelins and Kit signaling. The process of melanogenesis is centered around the transcription factor Mitf, a specification marker of the melanocytic lineage (Hou and Pavan, 2008) (Fig. 7C). Sox10 drives melanocyte specification by directly activating Mitf (Lee et al., 2000; Potterf et al., 2000; Verastegui et al., 2000) in mouse and human cell lines. Mitf in turn acts as a driver of terminal differentiation factors, activating several enzymes responsible for melanin synthesis in pigmented cells, such as those encoded by Dct, Tyr and Si (also known as Pmel) in the mouse (Murisier et al., 2007), as well as factors important for melanocyte survival and proliferation. In this context, Sox10 and Mitf operate in a feed-forward circuit. First, Sox10 directly activates Mitf, and then both genes cooperate to drive expression of melanogenic enzymes (Ludwig et al., 2004). Mitf regulation involves other transcriptional inputs, including the transcription factor Pax3/7, which cooperates with SOX10 to promote gene expression (Watanabe et al., 1998) in human cell lines. β-catenin/TCF is also important for MITF self-activation through a feedback loop in human cell lines, highlighting the role of WNT signaling during this process (Saito et al., 2002). Interestingly, FoxD3 inhibits Mitf expression, acting as a transcriptional switch to veer progenitors towards other cell fates (Curran et al., 2010). An interesting topic for future study will be the analysis of how activation of the melanocytic differentiation networks is restricted to particular subsets of neural crest cells.

Another example of a feed-forward loop involves Sox10 and Mef2c. Mef2c knockout mice exhibit pigmentation defects at birth, with drastic reductions in the number of melanocytes in the skin. These animals also show loss of expression of Mitf and Dct. Mef2c is directly activated by Sox10, and subsequently cooperates with the latter to activate itself and possibly other targets (Agarwal et al., 2011). Data from amniotes suggest that melanocyte specification and differentiation mostly rely upon feed-forward transcriptional circuits involving Sox10 and other transcription factors expressed in precursor cells, resulting in the robust activation of melanogenic enzymes. However, recent analysis of this circuit in zebrafish suggests an alternative possibility, in which sox10 instead negatively influences the expression of melanogenic enzymes. According to this study, Mitf represses sox10 by cooperating with HDACs, allowing for melanocytic differentiation (Greenhill et al., 2011). Such discrepancies in results obtained from mouse versus zebrafish studies might reflect species-specific mechanisms underlying the regulation of melanogenesis in these organisms (Hou et al., 2006).

Neuronal lineages

Similar to melanocytes, differentiation of the neural crest into neuronal and glial lineages relies upon Sox10 control of gene expression. Signaling pathways influence progenitor cells with respect to the cell type to which they contribute. For instance, neuregulin signaling biases neural crest progenitors to adopt a peripheral glial fate, whereas BMPs promote neuronal differentiation (Stemple and Anderson, 1993). Sympathetic neurons are specified by BMP signaling secreted by the dorsal aorta (Saito et al., 2012), which cooperates with Sox10 to activate expression of the sympathetic neuron specifier genes Phox2b and Ascl1 (Morikawa et al., 2009) (Fig. 7D and Fig. 8). These transcription factors activate downstream targets, such as Gata3, Insm1 and Hand2, which mediate cell cycle control, maintenance of survival and differentiation in sympathetic neurons (Rohrer, 2011). Most of these data derive from genetic analyses of knockout mice, and little is known about molecular mechanisms in this context. However, Tfap2a has been shown to directly regulate tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine β-hydroxylase and is thus a likely player in the differentiation of these cells (Kim et al., 2001). Further diversification of sympathetic neurons relies on the transcription factor Hmx1, which drives differentiation towards a noradrenergic sympathetic fate. This regulator is repressed in cholinergic neurons by Trkc (also known as Ntrk3) and Ret (Furlan et al., 2013).

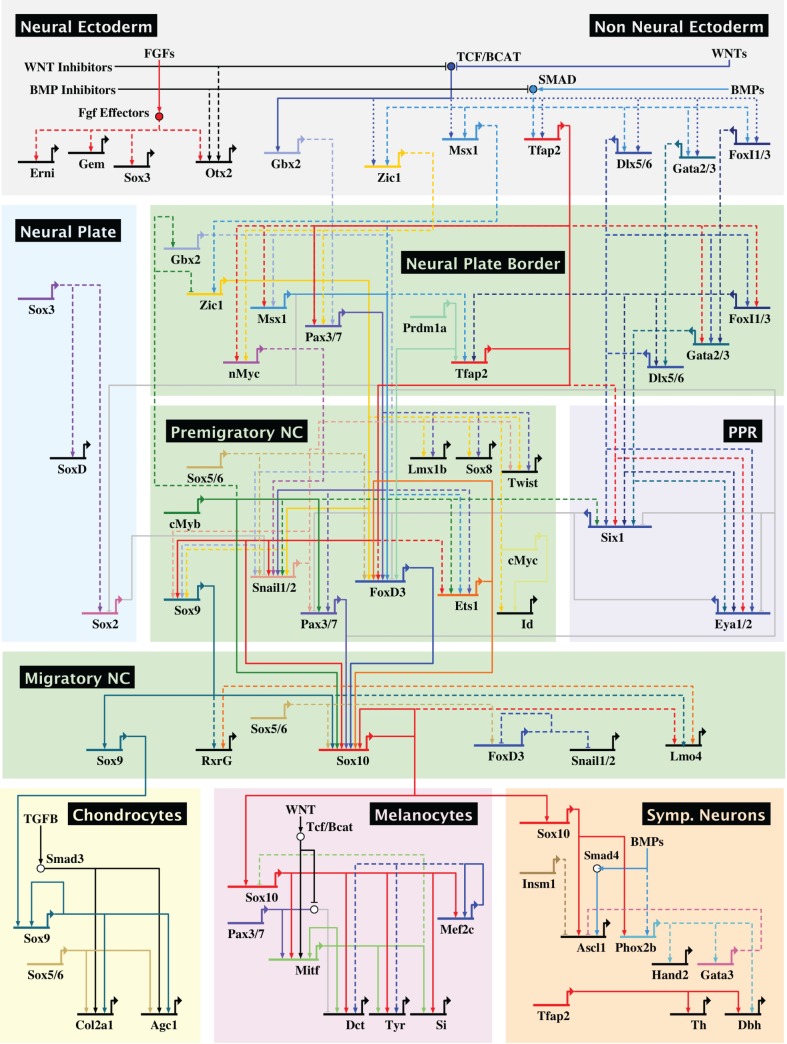

Fig. 8.

The GRN controlling neural crest development. Regulatory information obtained from different vertebrate model organisms has been assembled to produce a GRN that controls the formation and diversification of the neural crest. Direct interactions, supported by cis-regulatory analysis, are represented by solid lines, whereas dashed lines indicate interactions inferred from gene perturbation analysis.

The above examples of diversification circuits by no means represent an exhaustive survey. In addition to melanocytes, cartilage and sympathetic ganglia, neural crest cells form many other derivatives, including sensory neurons, Schwann cells, adipocytes and smooth muscle cells. Generally, neural crest diversification depends upon the interplay of the cell-intrinsic transcriptional machinery and its interpretation of environmental cues conveyed by distinct signaling pathways. In this regard, SoxE genes play a crucial role upstream of many neural crest cell lineages, either by directly driving differentiation (e.g. as in the case of Sox9 in chondrocyte differentiation) or by regulating the drivers that activate differentiation gene batteries. Furthermore, other early neural crest GRN components (Tfap2, Pax3/7 and Sox5/6) also participate later in the process of neural crest diversification, highlighting that the neural crest transcriptional machinery can be repurposed, such that factors that act in the maintenance of pluripotency can be subsequently deployed in differentiation programs.

Epigenetic regulation in neural crest formation

Although we have focused on the role of transcription factors in the program underlying neural crest development, it has become increasingly clear that this process contains additional layers of regulatory complexity. For example, transcription factors often work in conjunction with chromatin modifiers to activate or repress gene expression (Wang et al., 2011a; Strobl-Mazzulla and Bronner, 2012). Similarly, gene expression can be modulated by post-transcriptional regulation mediated by RNA-binding proteins and small regulatory RNAs, as well as post-translational modifications of transcription factors themselves by phosphorylation, sumoylation, and other changes that modify binding efficacy and stability (Taylor and LaBonne, 2007). As discussed below, DNA and histone modifications have been shown to play particularly important roles in both neural crest specification and EMT.

DNA methylation marks, which are conferred upon the promoter regions of genes by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), play an important role in silencing genes and thus operate to restrict fate choices during development (Okano et al., 1999; Smith and Meissner, 2013). In the neural crest, DNMTs have been shown to be important in the segregation of the neural crest from neural lineages. Dnmt3a, which is expressed in the neural plate border, directly represses expression of the neural genes Sox2/3 by methylating CpG islands in the neural crest progenitor territory. Knockdown of Dnmt3a results in the expansion of the neural plate and loss of neural crest specification (Hu et al., 2012). Although it is not clear how Dnmt3a is recruited to the promoter region of Sox2/3 in the dorsal neural tube, an intriguing possibility is that it may be recruited by transcription factors expressed in the neural crest progenitor region. The role of its paralog Dnmt3b is less clear. Mutations in DNMT3B seem to be linked to human craniofacial defects present in carriers of the ICF syndrome (Jin et al., 2008), and there is evidence for a role of this regulator in craniofacial development in zebrafish (Rai et al., 2010). However, conditional knockout of Dnmt3b in the mouse neural crest does not cause an obvious neural crest-related phenotype (Jacques-Fricke et al., 2012). Thus, there might be species-specific differences in the function of the enzyme.

Histone methylation affects gene regulation by defining repressive or active transcriptional states. Methylation marks are attached to the histones of the nucleosomes by methyltransferases and are removed by demethylases (Dambacher et al., 2010). Interestingly, removal of repressive methylation marks is necessary for the neural crest specification program. This is accomplished by the histone demethylase Kdm4a (Jmjd2a), which clears these marks from the Sox10 and Snai2 promoters (Strobl-Mazzulla and Bronner, 2012). At later stages of neural crest development, the histone demethylase Phf8 acts in a similar manner, and demethylates promoters of genes important for craniofacial development (Qi et al., 2010).

A different type of histone modification results from lysine acetylation, which is associated with active transcriptional states (Haberland et al., 2009b), and has been useful for investigating gene regulation in the neural crest (Rada-Iglesias et al., 2012). During EMT, it is well known that Snail proteins directly repress cadherins. In neural crest cells, the target of Snai2 is Cad6b, whose repression is mediated by recruitment of the histone deacetylase (HDAC) repressive complex to the Cad6b promoter, which occurs via interactions between Snai2, Sin3a and the adaptor protein Phd12 (also known as Phf12 or Pf1) (Strobl-Mazzulla and Bronner, 2012). HDACs are also expressed in the migratory neural crest (Simoes-Costa et al., 2014) and are involved in the diversification of derivatives. For example, HDACs act in the repression of foxd3 during melanophore specification in zebrafish (Ignatius et al., 2008) and have been shown to play important roles in the development of peripheral glia (Jacob et al., 2014) and ectomesenchymal derivatives (Haberland et al., 2009a) in the mouse.

These examples demonstrate that epigenetic modifications are an integral part of the gene regulatory machinery, playing a crucial role in modulating gene expression. Like other progenitor cell populations, the neural crest is likely to undergo global chromatin remodeling as it is specified and differentiates to different derivatives (Chen and Dent, 2014). However, the enzymes that catalyze either addition or removal of epigenetic marks are, for the most part, unable to interpret the genomic code. As a consequence, the epigenetic machinery depends upon the transcription factors of the GRN to find their destination in the genome and correctly mark their target sequences. Indeed, studies have shown that epigenetic repressive complexes are recruited to cis-regulatory regions and promoters by transcription factors (Ropero and Esteller, 2007; Wang et al., 2011a; Tam and Weinberg, 2013). Thus, rather than acting independently, these additional layers of regulation are intrinsically linked to the neural crest GRN.

Conclusions

The data presented here knit together our current knowledge of the neural crest program, from early establishment of the neural plate border to diversification into varied derivatives. The neural crest GRN is a feed-forward self-assembly ‘machine’ that combines positive transcriptional inputs with repressive interactions that establish firm borders between adjacent tissues, such as non-neural ectoderm, ectodermal placode, presumptive neural crest and future neural plate territories. Although these regulatory principles are shared among all developing neural crest cells, it is important to keep in mind that the neural crest is not a homogenous population and that differences in GRN structure underlie the regional properties observed in cranial, vagal, trunk and sacral neural crest. Thus, comparative gene regulatory analysis will be crucial to uncover the molecular mechanisms that are responsible for the differences in potential and behavior observed between neural crest subpopulations at different axial levels.

Our current view of this GRN is summarized in the BioTapestry visualization in Fig. 8, which focuses on the cranial neural crest. This is, by definition, overly simplified since many inputs have yet to be placed within the network and there are important differences between organisms that have been largely collapsed here into a pan-vertebrate model. Furthermore, although we have emphasized the role of transcription factors in the GRN, these regulators often function in large complexes in concert with epigenetic modifiers and non-coding RNAs including lncRNAs and microRNAs. Future experiments will need to further refine this GRN and focus on identifying direct interactions therein, as best accomplished by detailed cis-regulatory analysis. New technologies for identifying neural crest enhancers and performing genome editing will greatly facilitate elaboration of the neural crest GRN. This, in turn, will facilitate expansion of this network to other axial levels and provide increasingly detailed resolution of the events that underlie the formation of this fascinating cell type – the neural crest.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Funding

Work in the laboratory of M.E.B. is supported by the National Institutes of Health. M.S.-C. was funded by the Pew fellows Program in the Biomedical Sciences and by a grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Agarwal P., Verzi M. P., Nguyen T., Hu J., Ehlers M. L., McCulley D. J., Xu S.-M., Dodou E., Anderson J. P., Wei M. L. et al. (2011). The MADS box transcription factor MEF2C regulates melanocyte development and is a direct transcriptional target and partner of SOX10. Development 138, 2555-2565 10.1242/dev.056804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruga J. (2004). The role of Zic genes in neural development. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 26, 205-221 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attanasio C., Nord A. S., Zhu Y., Blow M. J., Li Z., Liberton D. K., Morrison H., Plajzer-Frick I., Holt A., Hosseini R. et al. (2013). Fine tuning of craniofacial morphology by distant-acting enhancers. Science 342, 1241006 10.1126/science.1241006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aybar M. J., Nieto M. A. and Mayor R. (2003). Snail precedes slug in the genetic cascade required for the specification and migration of the Xenopus neural crest. Development 130, 483-494 10.1242/dev.00238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae C.-J., Park B.-Y., Lee Y.-H., Tobias J. W., Hong C.-S. and Saint-Jeannet J.-P. (2014). Identification of Pax3 and Zic1 targets in the developing neural crest. Dev. Biol. 386, 473-483 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri-Fam S., Barrionuevo F., Dohrmann U., Günther T., Schüle R., Kemler R., Mallo M., Kanzler B. and Scherer G. (2006). Long-range upstream and downstream enhancers control distinct subsets of the complex spatiotemporal Sox9 expression pattern. Dev. Biol. 291, 382-397 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barembaum M. and Bronner M. E. (2013). Identification and dissection of a key enhancer mediating cranial neural crest specific expression of transcription factor, Ets-1. Dev. Biol. 382, 567-575 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriga E. H., Maxwell P. H., Reyes A. E. and Mayor R. (2013). The hypoxia factor Hif-1alpha controls neural crest chemotaxis and epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J. Cell Biol. 201, 759-776 10.1083/jcb.201212100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell D. M., Leung K. K. H., Wheatley S. C., Ng L. J., Zhou S., Ling K. W., Sham M. H., Koopman P., Tam P. P. L. and Cheah K. S. E. (1997). SOX9 directly regulates the type-II collagen gene. Nat. Genet. 16, 174-178 10.1038/ng0697-174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellmeyer A., Krase J., Lindgren J. and LaBonne C. (2003). The protooncogene c-Myc is an essential regulator of neural crest formation in Xenopus. Dev. Cell 4, 827-839 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00160-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancur P., Bronner-Fraser M. and Sauka-Spengler T. (2010a). Assembling neural crest regulatory circuits into a gene regulatory network. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 26, 581-603 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancur P., Bronner-Fraser M. and Sauka-Spengler T. (2010b). Genomic code for Sox10 activation reveals a key regulatory enhancer for cranial neural crest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 3570-3575 10.1073/pnas.0906596107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat N., Kwon H.-J. and Riley B. B. (2013). A gene network that coordinates preplacodal competence and neural crest specification in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 373, 107-117 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattaram P., Penzo-Méndez A., Sock E., Colmenares C., Kaneko K. J., Vassilev A., DePamphilis M. L., Wegner M. and Lefebvre V. (2010). Organogenesis relies on SoxC transcription factors for the survival of neural and mesenchymal progenitors. Nat. Commun. 1, 9 10.1038/ncomms1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M. J., Barrallo-Gimeno A., Acloque H., Reyes A. E., Tada M., Allende M. L., Mayor R. and Nieto M. A. (2007). Snail1a and Snail1b cooperate in the anterior migration of the axial mesendoderm in the zebrafish embryo. Development 134, 4073-4081 10.1242/dev.006858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britsch S., Goerich D. E., Riethmacher D., Peirano R. I., Rossner M., Nave K.-A., Birchmeier C. and Wegner M. (2001). The transcription factor Sox10 is a key regulator of peripheral glial development. Genes Dev. 15, 66-78 10.1101/gad.186601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner M. E. and LeDouarin N. M. (2012). Development and evolution of the neural crest: an overview. Dev. Biol. 366, 2-9 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugmann S. A., Pandur P. D., Kenyon K. L., Pignoni F. and Moody S. A. (2004). Six1 promotes a placodal fate within the lateral neurogenic ectoderm by functioning as both a transcriptional activator and repressor. Development 131, 5871-5881 10.1242/dev.01516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. F. and Behringer R. R. (1995). Twist is required in head mesenchyme for cranial neural tube morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 9, 686-699 10.1101/gad.9.6.686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T. and Dent S. Y. R. (2014). Chromatin modifiers and remodellers: regulators of cellular differentiation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 93-106 10.1038/nrg3607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung M. and Briscoe J. (2003). Neural crest development is regulated by the transcription factor Sox9. Development 130, 5681-5693 10.1242/dev.00808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung M., Chaboissier M.-C., Mynett A., Hirst E., Schedl A. and Briscoe J. (2005). The transcriptional control of trunk neural crest induction, survival, and delamination. Dev. Cell 8, 179-192 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophorou N. A. D., Bailey A. P., Hanson S. and Streit A. (2009). Activation of Six1 target genes is required for sensory placode formation. Dev. Biol. 336, 327-336 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay M. R. and Halloran M. C. (2013). Rho activation is apically restricted by Arhgap1 in neural crest cells and drives epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Development 140, 3198-3209 10.1242/dev.095448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles E. G., Taneyhill L. A. and Bronner-Fraser M. (2007). A critical role for Cadherin6B in regulating avian neural crest emigration. Dev. Biol. 312, 533-544 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couly G. F., Grapin-Bottom A., Coltey P. and Le Douarin N. M. (1996). The regeneration of the cephalic neural crest, a problem revisited: the regenerating cells originate from the contralateral or from the anterior and posterior neural folds. Development 122, 3393-3407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couly G., Grapin-Botton A., Coltey P., Ruhin B. and Le Douarin N. M. (1998). Determination of the identity of the derivatives of the cephalic neural crest: incompatibility between Hox gene expression and lower jaw development. Development 128, 3445-3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creazzo T. L., Godt R. E., Leatherbury L., Conway S. J. and Kirby M. L. (1998). Role of cardiac neural crest cells in cardiovascular development. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 60, 267-286 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran K., Lister J. A., Kunkel G. R., Prendergast A., Parichy D. M. and Raible D. W. (2010). Interplay between Foxd3 and Mitf regulates cell fate plasticity in the zebrafish neural crest. Dev. Biol. 344, 107-118 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambacher S., Hahn M. and Schotta G. (2010). Epigenetic regulation of development by histone lysine methylation. Heredity 105, 24-37 10.1038/hdy.2010.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Croze N., Maczkowiak F. and Monsoro-Burq A. H. (2011). Reiterative AP2a activity controls sequential steps in the neural crest gene regulatory network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 155-160 10.1073/pnas.1010740107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dottori M., Gross M. K., Labosky P. and Goulding M. (2001). The winged-helix transcription factor Foxd3 suppresses interneuron differentiation and promotes neural crest cell fate. Development 128, 4127-4138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton J. R., Antonellis A., Carney T. J., Rodrigues F. S. L. M., Pavan W. J., Ward A. and Kelsh R. N. (2008). An evolutionarily conserved intronic region controls the spatiotemporal expression of the transcription factor Sox10. BMC Dev. Biol. 8, 105 10.1186/1471-213X-8-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo Y., Osumi N. and Wakamatsu Y. (2002). Bimodal functions of Notch-mediated signaling are involved in neural crest formation during avian ectoderm development. Development 129, 863-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild C. L. and Gammill L. S. (2013). Tetraspanin18 is a FoxD3-responsive antagonist of cranial neural crest epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition that maintains cadherin-6B protein. J. Cell Sci. 126, 1464-1476 10.1242/jcs.120915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feledy J. A., Beanan M. J., Sandoval J. J., Goodrich J. S., Lim J. H., Matsuo-Takasaki M., Sato S. M. and Sargent T. D. (1999). Inhibitory patterning of the anterior neural plate in Xenopus by homeodomain factors Dlx3 and Msx1. Dev. Biol. 212, 455-464 10.1006/dbio.1999.9374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferronha T., Rabadan M. A., Gil-Guinon E., Le Dreau G., de Torres C. and Marti E. (2013). LMO4 is an essential cofactor in the Snail2-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of neuroblastoma and neural crest cells. J. Neurosci. 33, 2773-2783 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4511-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort P. and Théveneau E. (2014). PleiotRHOpic: rho pathways are essential for all stages of Neural Crest development. Small GTPases 5, e27975 10.4161/sgtp.27975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlan A., Lübke M., Adameyko I., Lallemend F. and Ernfors P. (2013). The transcription factor Hmx1 and growth factor receptor activities control sympathetic neurons diversification. EMBO J. 32, 1613-1625 10.1038/emboj.2013.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furumatsu T., Tsuda M., Taniguchi N., Tajima Y. and Asahara H. (2005). Smad3 induces chondrogenesis through the activation of SOX9 via CREB-binding protein/p300 recruitment. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8343-8350 10.1074/jbc.M413913200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans C. and Northcutt R. G. (1983). Neural crest and the origin of vertebrates: a new head. Science 220, 268-273 10.1126/science.220.4594.268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Castro M. I., Marcelle C. and Bronner-Fraser M. (2002). Ectodermal Wnt function as a neural crest inducer. Science 13, 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett A. T., Square T. A. and Medeiros D. M. (2012). BMP, Wnt and FGF signals are integrated through evolutionarily conserved enhancers to achieve robust expression of Pax3 and Zic genes at the zebrafish neural plate border. Development 139, 4220-4231 10.1242/dev.081497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill E. R., Rocco A., Vibert L., Nikaido M. and Kelsh R. N. (2011). An iterative genetic and dynamical modelling approach identifies novel features of the gene regulatory network underlying melanocyte development. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002265 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grocott T., Tambalo M. and Streit A. (2012). The peripheral sensory nervous system in the vertebrate head: a gene regulatory perspective. Dev. Biol. 370, 3-23 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves A. K. and LaBonne C. (2014). Setting appropriate boundaries: fate, patterning and competence at the neural plate border. Dev. Biol. 389, 2-12 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guémar L., de Santa Barbara P., Vignal E., Maurel B., Fort P. and Faure S. (2007). The small GTPase RhoV is an essential regulator of neural crest induction in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 310, 113-128 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberland M., Mokalled M. H., Montgomery R. L. and Olson E. N. (2009a). Epigenetic control of skull morphogenesis by histone deacetylase 8. Genes Dev. 23, 1625-1630 10.1101/gad.1809209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberland M., Montgomery R. L. and Olson E. N. (2009b). The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: implications for disease and therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 32-42 10.1038/nrg2485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall B. K. (1999). The Neural Crest in Development and Evolution. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hall B. K. (2000). The neural crest as a fourth germ layer and vertebrates as quadroblastic not triploblastic. Evol. Dev. 2, 3-5 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2000.00032.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y. and Lefebvre V. (2008). L-Sox5 and Sox6 drive expression of the aggrecan gene in cartilage by securing binding of Sox9 to a far-upstream enhancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 4999-5013 10.1128/MCB.00695-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong C.-S. and Saint-Jeannet J.-P. (2007). The activity of Pax3 and Zic1 regulates three distinct cell fates at the neural plate border. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 2192-2202 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honoré S. M., Aybar M. J. and Mayor R. (2003). Sox10 is required for the early development of the prospective neural crest in Xenopus embryos. Dev. Biol. 260, 79-96 10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00247-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horstadius S. (1950). The Neural Crest. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hou L. and Pavan W. J. (2008). Transcriptional and signaling regulation in neural crest stem cell-derived melanocyte development: do all roads lead to Mitf? Cell Res. 18, 1163-1176 10.1038/cr.2008.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L., Arnheiter H. and Pavan W. J. (2006). Interspecies difference in the regulation of melanocyte development by SOX10 and MITF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 9081-9085 10.1073/pnas.0603114103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu N., Strobl-Mazzulla P., Sauka-Spengler T. and Bronner M. E. (2012). DNA methyltransferase3A as a molecular switch mediating the neural tube-to-neural crest fate transition. Genes Dev. 26, 2380-2385 10.1101/gad.198747.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatius M. S., Moose H. E., El-Hodiri H. M. and Henion P. D. (2008). colgate/hdac1 repression of foxd3 expression is required to permit mitfa-dependent melanogenesis. Dev. Biol. 313, 568-583 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob C., Lotscher P., Engler S., Baggiolini A., Tavares S. V., Brugger V., John N., Buchmann-Moller S., Snider P. L., Conway S. J. et al. (2014). HDAC1 and HDAC2 control the specification of neural crest cells into peripheral glia. J. Neurosci. 34, 6112-6122 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5212-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacques-Fricke B. T., Roffers-Agarwal J. and Gammill L. S. (2012). DNA methyltransferase 3b is dispensable for mouse neural crest development. PLoS ONE 7, e47794 10.1371/journal.pone.0047794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger J. (2011). The gap gene network. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68, 243-274 10.1007/s00018-010-0536-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]