Abstract

We performed a detailed analysis of both single-nucleotide and large insertion/deletion events based on large-scale comparison of 10.6 Mb of genomic sequence from lemur, baboon, and chimpanzee to human. Using a human genomic reference, optimal global alignments were constructed from large (>50-kb) genomic sequence clones. These alignments were examined for the pattern, frequency, and nature of mutational events. Whereas rates of single-nucleotide substitution remain relatively constant (1–2 × 10−9 substitutions/site/year), rates of retrotransposition vary radically among different primate lineages. These differences have lead to a 15%–20% expansion of human genome size over the last 50 million years of primate evolution, 90% of it due to new retroposon insertions. Orthologous comparisons with the chimpanzee suggest that the human genome continues to significantly expand due to shifts in retrotransposition activity. Assuming that the primate genome sequence we have sampled is representative, we estimate that human euchromatin has expanded 30 Mb and 550 Mb compared to the primate genomes of chimpanzee and lemur, respectively.

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org.]

Initial studies of primate genome variation were based largely on indirect evidence obtained from DNA hybridization kinetics (Sibley and Ahlquist 1984; Powell and Caccone 1990; Sibley et al. 1990). Molecular studies have been limited mainly by the lack of large-scale DNA sequence data (Bailey et al. 1991; Smith 1992; Horai et al. 1995; Kaessmann et al. 1999; Bohossian et al. 2000; Chen and Li 2001). In the past, such large-scale comparisons were dependent upon PCR cross-amplification among diverse primate taxa and, therefore, were biased to either conserved regions or limited to closely related species. With the anticipated completion of the human genome sequence (International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium 2001; Venter et al. 2001) and the development of primate BAC library resources (Eichler and DeJong 2002), it is now possible to initiate large-scale genomic comparisons (Thomas et al. 2002) in an unbiased fashion to assess the nature and pattern of primate genomic variation. Direct comparison of high-quality finished sequence from BAC clones of orthologous loci will not only elucidate mechanisms of genome evolution, but also shed light into the historical events that have shaped our species.

A variety of mutational forces are thought to have molded the human genome. These include both small-scale (single-base pair changes, microsatellite slippage, insertion/deletions) as well as large-scale events (retrotransposition, genomic rearrangements, segmental duplication). To date, most evolution studies have focused on either single-base pair changes or microsatellite evolution (Chen et al. 2001; Ebersberger et al. 2002; Smith et al. 2002; Webster et al. 2002). Estimating rates of retrotransposition has been difficult in part due to the paucity of such de novo events over short stretches of DNA sequence as well as biases in repeat classification and genomic insertion sites (Chiaromonte et al. 2001; Batzer and Deininger 2002). Over the last 60 million years of evolution, the human genome has been bombarded by a variety of repeat elements through successive waves of retrotransposition (Smit 1999; Deininger and Batzer 2002). Among these, L1 (long interspersed repeat element 1) and Alu (a short interspersed repeat) elements are most prevalent (Moran et al. 1999; Batzer and Deininger 2002). Combined, they account for an estimated 26%–27% of the human genome (International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium 2001; Venter et al. 2001).

In this study, we analyzed genomic sequence from three species (chimpanzee, baboon, and lemur) and compared it to the human genome. These three species are estimated to have diverged from human at three very different time points, approximately 5.5, 25, and 55 million years ago (Goodman 1999). This analysis therefore provides a snapshot of genomic change representative of the evolutionary depth of the primate order. Most of the sequence was generated by the NIH Intramural Sequencing Center (http://www.nisc.nih.gov/) and represents orthologous regions to human chromosome 7. As part of this study, we generated large-scale alignments (ranging in length from 50–150 kb), providing a baseline for our analysis of genomic variation. The objective was to assess patterns of not only single-nucleotide variation but also larger-scale events as a function of evolutionary time.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Alignment Validation

One of the most significant challenges to large-scale genomic analyses is the generation of biologically meaningful global alignments (Chen et al. 2001). A total of 10.6 Mb of aligned sequence between human and nonhuman primates were analyzed which included human orthologous comparisons with 51 chimpanzee, 42 baboon, and 9 lemur BAC clones or subclones. For each species, we chose a subset of gap opening and gap extension penalties which minimized the frequency of both single-nucleotide and insertion/deletion events. An assessment of both types of variation simultaneously, we reasoned, should provide the most biologically meaningful optimal global alignment (Methods). In order to validate the reliability of our alignment parameters, a number of tests were performed. First, we analyzed the nature of the sequence underlying insertion/deletions within each alignment (Methods). A variety of biological events are known to create insertion/deletions, including lineage-specific amplification of tandem repeats, homology-mediated genomic deletions, and retrotransposition events. Alignment parameters were favored where such large-scale insertion/deletions were effectively treated as a single event. All individual alignments and patterns of single-nucleotide variation were manually inspected and are available online (http://eichlerlab.cwru.edu/primategenome/).

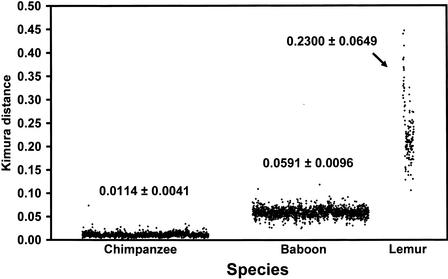

As a second test, we compared overall estimates of sequence divergence (Table 1) with previous reports in the literature (Li 1997; Chen and Li 2001; Chen et al. 2001; Ebersberger et al. 2002; Fujiyama et al. 2002). These studies are particularly relevant for human–chimpanzee alignments where similar sequence comparison studies using different alignment parameters have been performed. Although our results for human and chimpanzee divergence (K = 1.14%) are comparable to those of previous studies (1.18%–1.24%; Chen and Li 2001; Chen et al. 2001; Fujiyama et al. 2002; Smith et al. 2002), our estimate is lower. In our study, we excluded regions that harbored large, low-copy repeat sequences, as the orthologous relationship of these could not be unambiguously determined. Such segmental duplicated regions may significantly inflate estimates of divergence due to nonorthologous sequence relationships (Chen et al. 2001; Bailey et al. 2002) or gene conversion (Hurles 2001). Because comparable sets of data do not exist for other nonhuman primates, we generated 1000 randomly selected end sequences from existing BAC libraries (Eichler and DeJong 2002) for each species. Comparing high-quality alignments of BAC end sequence with these optimal global alignments, we observed similar estimates of sequence divergence between human–lemur (20%–21%), human–baboon (5%–6%), and human–chimpanzee (1%–1.2%). The variation distribution pattern of these short alignments (400–500 bp; data not shown) was remarkably similar to the distribution observed for nonoverlapping 500-bp windows generated from chromosome 7 optimal global alignments (Fig. 1, Suppl. Fig. S4).

Table 1.

Primate Single-Nucleotide Variation versus Sequence Class

| # loci | Alignment length (bp) | Aligned bases (bp) | Matches (bp) | Mismatches (bp) | Transitions (s) | Transversions (v) | s/v | Identity (%) | Kimura Distance (%) | Ra ×10−9 | |

| Human–Chimpanzee | |||||||||||

| Overall | 51 | 4968069 | 4853708 | 4798947 | 54761 | 36914 | 17847 | 2.07 | 98.87 ± 0.00 | 1.14 ± 0.00b | 1.034 ± 0.004 |

| Overall-CG | 51 | 4968069 | 4764283 | 4723249 | 41034 | 15414 | 25620 | 1.66 | 99.14 ± 0.00 | 0.87 ± 0.00 | 0.788 ± 0.004 |

| Exon | 24 | 69051 | 68957 | 68543 | 414 | 296 | 118 | 2.51 | 99.40 ± 0.03 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 0.548 ± 0.027 |

| Unique noncoding | 51 | 2749584 | 2720023 | 2692593 | 27430 | 8913 | 18517 | 2.08 | 98.99 ± 0.01 | 1.02 ± 0.01 | 0.924 ± 0.006 |

| Repetitive | 51 | 2201336 | 2098297 | 2070750 | 26547 | 8393 | 18154 | 2.16 | 98.73 ± 0.01 | 1.28 ± 0.01 | 1.162 ± 0.007 |

| Alu | 51 | 446212 | 419379 | 412882 | 6497 | 4577 | 1920 | 2.38 | 98.45 ± 0.02 | 1.57 ± 0.02 | 1.425 ± 0.018 |

| Alu-CG | 51 | 446212 | 399048 | 395013 | 4035 | 1567 | 2468 | 1.57 | 98.99 ± 0.02 | 1.02 ± 0.02 | 0.926 ± 0.015 |

| L1 | 51 | 837035 | 767774 | 758213 | 9561 | 6322 | 3239 | 1.95 | 98.75 ± 0.01 | 1.26 ± 0.01 | 1.143 ± 0.012 |

| Human–Baboon | |||||||||||

| Overall | 42 | 4984965 | 4456507 | 4204745 | 251762 | 167380 | 84382 | 1.98 | 94.35 ± 0.01 | 5.90 ± 0.01b | 1.181 ± 0.002 |

| Overall-CG | 42 | 4984965 | 4351198 | 4140103 | 211095 | 75237 | 135858 | 1.81 | 95.15 ± 0.01 | 5.03 ± 0.01 | 1.007 ± 0.002 |

| Exon | 24 | 48578 | 48098 | 46627 | 1471 | 1042 | 429 | 2.43 | 96.94 ± 0.08 | 3.13 ± 0.08 | 0.627 ± 0.016 |

| Unique noncoding | 42 | 3148255 | 3022715 | 2862848 | 159867 | 106002 | 53865 | 1.97 | 94.71 ± 0.01 | 5.51 ± 0.01 | 1.102 ± 0.003 |

| Repetitive | 42 | 1973097 | 1555295 | 1456755 | 98540 | 66258 | 32282 | 2.05 | 93.66 ± 0.02 | 6.66 ± 0.02 | 1.332 ± 0.004 |

| Alu | 42 | 404917 | 292641 | 267869 | 24772 | 17219 | 7553 | 2.28 | 91.54 ± 0.05 | 9.07 ± 0.06 | 1.814 ± 0.012 |

| Alu-CG | 42 | 404917 | 275514 | 256962 | 18552 | 6506 | 12046 | 1.85 | 93.27 ± 0.05 | 7.10 ± 0.05 | 1.419 ± 0.011 |

| L1 | 42 | 778575 | 538863 | 507237 | 31626 | 20465 | 11161 | 1.83 | 94.13 ± 0.03 | 6.14 ± 0.04 | 1.228 ± 0.007 |

| Human–Lemur | |||||||||||

| Overall | 9 | 623139 | 423139 | 341061 | 82078 | 47053 | 35025 | 1.34 | 80.60 ± 0.06 | 22.73 ± 0.08b | 2.066 ± 0.008 |

| Overall-CG | 9 | 623139 | 406011 | 332321 | 73690 | 31863 | 41827 | 1.31 | 81.85 ± 0.06 | 21.01 ± 0.08 | 1.910 ± 0.007 |

| Unique | 9 | 370337 | 313512 | 255977 | 57535 | 33526 | 24009 | 1.40 | 81.65 ± 0.07 | 21.31 ± 0.09 | 1.938 ± 0.009 |

| Repetitive | 9 | 244728 | 103787 | 80333 | 23454 | 12909 | 10545 | 1.22 | 77.40 ± 0.13 | 27.25 ± 0.19 | 2.477 ± 0.017 |

Orthologous sequences were globally aligned with ALIGN (Methods). A suboptimal alignment was defined as any alignment which exceeded two standard deviations of the mean genetic distance (window size 2 kb, slide 100 bp). These regions were not included in the analysis. The mean and standard deviation of alignment lengths are 106, 107 ± 41,659, 95,171 ± 38,751, and 47,015 ± 34,144 bp for human–chimpanzee, human–baboon, and human–lemur comparisons. Exon sequence was restricted only to well-annotated human genes (NCBI RefSeq database). Repetitive sequences were detected using RepeatMasker (version 3.0). Unique noncoding regions excluded both exonic and repetitive regions. For human–baboon and human–chimpanzee comparisons, Alu and L1 were calculated separately. Relatively few L1 and Alu repeats were orthologous between human and lemur genomic alignments and were therefore not partitioned. Due to the enrichment of CpG dinucleotides with Alu repeats, we considered substitutions without CpG dinucleotides (Alu-CG) as well as the overall content minus CpG dinucleotides in each species (Overall-CpG).

Substitution rate calculations assume divergence times of the human lineage from chimpanzee, baboon and lemur of 5.5, 25 and 55 Mya (Goodman 1999).

If suboptimal alignments were included in the analysis, the overall genetic distance increases to 1.14 ± 0.00%, 6.05 ± 0.01% and 25.69 ± 0.07%, respectively (Methods).

Figure 1.

Single-nucleotide variation. A scatter plot of genetic distances (changes/bp) determined from nonoverlapping 3-kb sliding windows for human–chimpanzee (51 loci, 5.0 Mb, 9684 windows), human–baboon (42 loci, 5.0 Mb, 8893 windows), and human–lemur (9 loci, 0.62 Mb, 841 windows) sequence alignments. These were plotted against human divergence times of 5.5, 25, and 55 Mya for chimpanzee, baboon, and lemur alignments, respectively. Suboptimal alignments were excluded. The means and their standard deviations are shown.

Single-Nucleotide Variation

Based on estimated divergence times from the human lineage (Goodman 1999), we calculated the substitution rate for each species comparison (Table 1). Estimates of overall single-base pair substitution rate ranged from 1.0 × 10−9 mutations/site/year for human–chimpanzee comparisons to 2.1 × 10–9 mutations/site/year for human–lemur comparisons (Table 1). It has been suggested that the rate of substitution has slowed by as much as 50% among hominoids (humans and apes) after their separation from the Old World monkey lineage (Goodman et al. 1971; Koop et al. 1986; Li and Tanimura 1987). Indeed, a noticeably higher substitution rate was calculated based on human–baboon sequence alignments compared to estimates from human–chimpanzee alignments (Table 1). This effect becomes more dramatic when CpG dinucleotide sites are excluded. Human–lemur sequence comparisons indicated that the most dramatic change in the rate of substitution occurred early in primate evolution (25–55 million years ago), possibly owing to generation-time differences among prosimian and simian lineages (Ruvolo 1997). Although significant differences in the mean genetic distance were observed between human and nonhuman primates, the variance of these estimates was not constant. When we analyzed nonoverlapping 3-kb blocks of aligned genomic sequence, a considerable increase in genomic variance in sequence identity was observed as a function of evolutionary divergence (Fig. 1).

We performed a substitution relative rate test for all instances where three or more homologous sequences were available. We constructed 19 multiple alignments for human, chimpanzee, and baboon (2.5 Mb) and five multiple alignments for all four species (0.51 Mb). Relative rate tests were performed using Tajima's test (Kumar et al. 2001). Seventeen of the 19 rate tests supported the molecular clock hypothesis for human, chimpanzee, and baboon alignments. Similarly, when lemur was used as an outgroup, human and chimpanzee were found to have nearly identical substitution rates. In contrast, when using lemur as an outgroup, both human and chimpanzee had slower rates of substitution compared to baboon. Therefore, a local molecular clock seems to hold well between human and chimpanzee (Zuckerkandl and Pauling 1965). It is worth noting that the data used in these studies were limited to four species, and rate calculations may be confounded by incorrect estimates of species divergence times. However, even if more distant divergence times are used, the data clearly indicate that substitution rate has at least doubled among prosimians compared to the haplorhime species.

Retrotransposition

Retrotransposition typically creates large sequence insertions ranging in size from a few 100 bp to ∼10 kb in length. Three major classes of retroelements have shaped the primate genome in recent evolutionary history: L1 (LINE), Alu (SINE), and LTR (long terminal repeat elements of endogenous retroviruses; International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium 2001). We examined all insertion/deletion (indel) events in excess of 100 bp within baboon and chimpanzee/human alignments in order to identify new insertions that had occurred over the last 25 million years of evolution. An indel was classified as a retrotransposition event if at least 80% of the indel contained one predominant repeat. We considered the known interspersed repeat phylogeny based on the established repeat subclasses as reported (Smit 1999). All insertions were considered, including the ancient repeat subclasses that passed our test. Further, in the case of L1 and Alu repeats, insertion sequences were examined for the presence of target-site duplications and a polyadenylation tail at the site of integration (Methods). The determination of new insertion elements was based exclusively on the analysis of pairwise sequence alignments. Because the vast majority of retroelement events are irreversible genetic character states (Perna et al. 1992; Deininger and Batzer 1999), unlike other insertion/deletion events, the directionality of the event could be unambiguously assigned to a specific lineage (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primate Retrotransposition Events

| Human–Chimpanzee | ||||||||||

| Repeats | Chimpanzee | Human | ||||||||

| Insertions | Rate (/Mb/My) | Insertions | Rate (/Mb/My) | |||||||

| Events | Length (bp) | Mean length (bp) | Count | Base | Events | Length (bp) | Mean length (bp) | Count | Base | |

| LINE/L1 | 5 | 4404 | 881 | 0.18 | 162 | 9 | 32393 | 3599 | 0.33 | 1195 |

| SINE/Alu | 11 | 3311 | 301 | 0.41 | 122 | 23 | 7036 | 306 | 0.85 | 259 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | — | 0.00 | 0 | 2 | 2040 | 1020 | 0.07 | 75 |

| Subtotal | 16 | 7715 | 482 | 0.59 | 69 | 34 | 41469 | 1220 | 1.25 | 369 |

| Human–Baboon | ||||||||||

| Repeats | Baboon | Human | ||||||||

| Insertions | Rate (/Mb/My) | Insertions | Rate (/Mb/My) | |||||||

| Events | Length (bp) | Mean length (bp) | Count | Base | Events | Length (bp) | Mean length (bp) | Count | Base | |

| LINE/L1 | 26 | 48882 | 1880 | 0.23 | 435 | 36 | 58670 | 1630 | 0.32 | 523 |

| LTR | 2 | 1407 | 704 | 0.02 | 13 | 11 | 31297 | 2845 | 0.08 | 279 |

| SINE/Alu | 153 | 45538 | 298 | 1.36 | 406 | 96 | 29000 | 302 | 0.86 | 258 |

| Other | 1 | 130 | 130 | 0.01 | 1 | 2 | 2836 | 1418 | 0.02 | 25 |

| Subtotal | 182 | 95957 | 527 | 1.62 | 855 | 145 | 121803 | 840 | 1.29 | 1085 |

| Human–Lemur | ||||||||||

| Lemur | Human | |||||||||

| Insertions | Rate (/Mb/My) | Insertions | Rate (/Mb/My) | |||||||

| Events | Length (bp) | Mean length (bp) | Count | Base | Events | Length (bp) | Mean length (bp) | Count | Base | |

| DNA | 8 | 4903 | 613 | 0.19 | 119 | 5 | 1223 | 245 | 0.10 | 24 |

| LINE/L1*** | 3 | 3223 | 1074 | 0.07 | 78 | 53 | 40635 | 767 | 1.04 | 799 |

| LTR*** | 5 | 2131 | 426 | 0.12 | 52 | 16 | 8416 | 526 | 0.31 | 165 |

| SINE/Alu*** | 40 | 10659 | 266 | 0.97 | 259 | 234 | 64991 | 278 | 4.60 | 1278 |

| Other | 2 | 281 | 141 | 0.05 | 7 | 2 | 750 | 375 | 0.04 | 15 |

| Subtotal*** | 50 | 16294 | 326 | 1.21 | 395 | 305 | 114792 | 376 | 6.00 | 2257 |

We examined all insertion deletion events in excess of 100 bp from global alignments. An indel was classified as a retrotransposition event if at least 80% of the indel contained one predominant repeat. We considered the known interspersed repeat phylogeny based on the established repeat subclasses as reported previously (Smit 1999). All insertions were considered including the ancient repeat subclasses that passed our test. Further, in the case of L1 and Alu repeats, insertion sequences were examined for the presence of target-site duplications and a polyadenylation signal at the site of integration. The rate calculation assumed divergence times of the human lineage from chimpanzee, baboon, and lemur of 5.5, 25, and 55 Mya. Pairwise alignment lengths were 5.0, 5.0, and 0.62 Mb for human–chimpanzee, human–baboon, and human–lemur sequence alignment, respectively.

P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 by χ2 test.

Analysis of the chimpanzee data shows a general decline in the level of L1, SINE, and LTR activity compared to the human. A significant decrease (P < 0.05, χ2 = 5.90) was observed in the number of new elements in chimpanzee (n = 16) compared to human (n = 34). To test whether this difference in the frequency of new retrotransposition events could be observed in an independent data set, we assessed the occurrence of “young” Alu elements in a random sample of 148,102 chimpanzee and 743,245 human BAC-end sequence clones (Zhao et al. 2000; Fujiyama et al. 2002). Lineage-specific Alu elements were identified based on new Alu insertions within human–chimpanzee orthologous genomic sequences (5.0 Mb) that had been identified in the present study. A similar analysis was performed with consensus sequences from Alu subfamilies (Ya5, Yb8, etc). After normalizing for sequence content, we observed a significant decrease (P < 0.001, χ2 = 25.01) in the number of Alu elements within chimpanzee BAC end sequences compared to human (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of “Young” Alu Elements Within BAC End Sequences

| Lineage-specific Query Sequences | Database | |

| Human BES | Chimpanzee BES | |

| Human Alus | 15.92* | 6.00 |

| Chimpanzee Alus | 19.49** | 6.00 |

Lineage-specific Alu retrotransposition events were identified by analysis of human–chimpanzee orthologous genomic sequence. Extracted representative events (query sequences) were searched against a database of BAC end sequences (BES) which included 743,245 human BES (354,136,231 bp; Zhao et al. 2000) and 148,102 chimpanzee BES (115,468,024 bp; Fujiyama et al. 2002). Only full-length Alu elements were considered. When query sequence and BAC end-sequences were from the same species, a sequence similarity cutoff of 98.5% was used to account for sequencing errors within the single-pass BES database. When query sequence and BAC end sequences were from different species, sequence similarities greater or equal to 96.5% were counted (to account for sequencing error and species divergence). Human counts were further normalized by the size ratio of human and chimpanzee BAC end sequence library. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 by χ2 test assuming equal distribution. In both cases, the human BES database shows a significant increase in the number of young Alu elements.

In contrast to the chimpanzee, the baboon showed a highly significant increase (P = 0.0003; χ2 = 13.05) in the number of retroelement insertions compared to human orthologous genomic sequence. This overall increase was almost exclusively due to the 1.6-fold increase in the number of Alu insertions observed in the baboon lineage (96 Alu insertions in human compared to 153 insertions in baboon; Table 2). Interestingly, humans showed a significant increase in the number of retroviral LTR insertions (P = 0.0126, χ2 = 6.23) compared to baboon. Due to the hypermutability of retroviral sequences and their problematic annotation, more detailed analysis of this apparent LTR increase is warranted. Genomic comparison with lemur sequence demonstrates the most dramatic difference in new retroelement insertions. Compared to orthologous human genome sequence, significant decreases in the amount of retroelement sequence are observed overall (P < 0.0001, χ2 = 183.17) for most classes of retroposons (Table 2). The most pronounced effect once again is found among Alu elements. In our analysis of 623 kb of aligned orthologous sequence, we identified a total of 96 Alu elements in lemur sequences, compared to 519 Alu elements in human sequences overall. The majority of these events appeared to be specific to each lineage (Table 2). Similar decreases were obtained based on baboon–lemur genomic comparisons, indicating that a major burst in retrotransposition activity occurred 25–50 million years ago, consistent with a previous analysis based on Alu subfamily diversity (Shen et al. 1991).

These data predict extreme variability in rates of fixation and/or retrotransposition in different primate lineages. Within the human lineage, the rates of Alu and L1 insertions have remained relatively constant over the last 25 million years. Assuming that our 5.0-Mb subsample is representative of the human genome, we estimate the fixation of 990 and 960 new insertions of L1 elements per genome per million years (chimpanzee/human and baboon/human comparisons, respectively). Similarly for Alu elements, we calculate a remarkably constant rate of new insertion; between 2450 and 2580 new insertions per million years (based on chimpanzee/human and baboon/human alignments, respectively). Changes in new insertion frequencies, therefore, appear to have occurred within nonhuman primate lineages as opposed to human (Table 2), although additional sequence data from New World and other prosimian lineages will be required before any general trends can be firmly established. Several factors have been proposed to account for lineage-specific changes in retrotransposition activity, including changes in insertion site availability, competence of active progenitor elements, and efficiency of reverse transcription (Deininger and Batzer 1999). The fact that the frequency of both L1 and Alu new insertions is decreased within the chimpanzee genome may point to a reduction in reverse transcriptase activity, since both elements are dependent on the same enzymatic machinery for propagation. In this regard, it is interesting that the average length of new L1 insertions appears to be much smaller in chimpanzee (880 bp) than in human (3500 bp)—a possible indicator of lowered processivity and also a source of a reduced amount of enzyme.

Human Genome Expansion

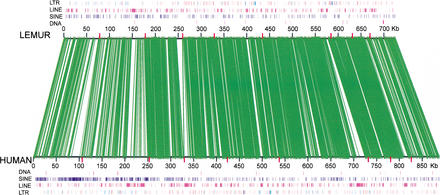

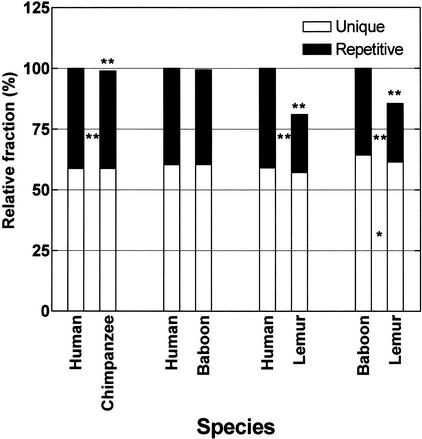

During our analysis of orthologous genomic sequence, we noticed that the human genome sequence was consistently longer (Table 4) for each primate species comparison overall. The average human sequence expansion ranged from 0.6% for human–baboon comparisons to as much as 19% for human–lemur comparisons (Figs. 2,3). The expansion in human sequence compared to baboon is particularly striking, considering that an additional 16.5 kb of sequence has been introduced by the apparent increase in baboon Alu retroposon activity (Table 2). A permutation test of the difference was performed at the level of the alignment as well as at the level of individual insertion/deletion events (see Methods; Table 4) for each species comparison. With the exception of the baboon, a significant increase (P < 0.05) in genome size was observed for the human genome in each case (Table 4). We divided the genome into two fractions, repetitive and unique DNA, to assess the source of this expansion. Most of the significant increase (80%–100%) could be assigned to an increase in retroposon content within the orthologous human sequence (Table 4).

Table 4.

Primate Genome Size Variation

| All | Repeats | Unique | ||||

| Length (bp) | % | Length (bp) | % | Length (bp) | % | |

| Human | 5410556 | 100.00 | 2204532 | 40.75 | 3206024 | 59.25 |

| Chimpanzee | 5351536 | 98.91 | 2148580 | 39.71 | 3202956 | 59.20 |

| Difference | 59020 | 1.09** | 55952 | 1.03** | 3068 | 0.06 |

| Human | 5560707 | 100.00 | 2181276 | 39.23 | 3379431 | 60.77 |

| Baboon | 5527115 | 99.40 | 2143997 | 38.56 | 3383118 | 60.84 |

| Difference | 33592 | 0.60 | 37279 | 0.67a | −3687 | −0.07 |

| Human | 924753 | 100.00 | 374742 | 40.52 | 550011 | 59.48 |

| Lemur | 749135 | 81.01 | 216540 | 23.42 | 532595 | 57.59 |

| Difference | 175618 | 18.99** | 158202 | 17.11** | 17416 | 1.88 |

| Baboon | 790055 | 100.00 | 278145 | 35.21 | 511910 | 64.79 |

| Lemur | 675780 | 85.54 | 187084 | 23.68 | 488696 | 61.86 |

| Difference | 114275 | 14.46** | 91061 | 11.53** | 23214 | 2.94 |

For orthologous genomic comparisons, the length of aligned sequence and difference were considered for each species comparison. Repetitive and unique portions were identified using RepeatMasker (version 3.0) from human–chimpanzee (51 loci), human–baboon (42 loci), human– lemur (nine loci), and baboon–lemur (eight loci) comparisons. In the event that lemur common repeats were not efficiently masked, intraspecific sequence similarity searches (BLAST) were performed to identify potentially missing repeats. Relative percentages were calculated assuming the length of larger primate genome (human or baboon) as 100%. Significance of the difference in genome size was tested by a permutation test (10,000 replicates). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. aThe difference in repeat composition is greater than the total due to an expansion of LTR content and deletion of 3687 bp of unique sequence. Table S8 shows a more detailed breakdown by repeat class for both human–lemur and baboon–lemur alignments.

Figure 2.

Human vs. lemur genome comparison. Nine orthologous genomic regions between human and lemur were concatenated for each species (lemur: top, human: bottom), and regions of conservation were visualized (parasight). Red bars demarcate the extent of each orthologous alignment. Repeat content for each region is depicted as a colored track: SINE, blue; LINE, pink; DNA transposon, salmon; LTR, cyan; low complexity and simple repeat, red. The human genomic sequence is ∼19% larger.

Figure 3.

Primate genome size variation. Repetitive and unique portions of aligned orthologous sequences were identified by RepeatMasker (version 3.0, slow option). Relative fractions were based on the larger primate genome. Significance of the difference in genome size was determined by a permutation test (10,000 replicates, see Methods). Asterisks over species bars indicate significant differences in overall lengths, and those between species bars indicate significant differences in either repetitive or unique lengths between two species. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Large-scale comparative sequencing of vertebrate genomes has shown that syntenic regions in other species are shorter and contain fewer repeats compared to human (Dehal et al. 2001; Aparicio et al. 2002; Mural et al. 2002). Our analysis extends this property of the human genome to at least two other primate species. One possible explanation for these differences is a change in the deletion rate of repetitive elements within different lineages (Dehal et al. 2001; Aparicio et al. 2002; Mural et al. 2002). The human lineage, for example, may retain more retroposon elements because its inherent mutational mechanisms are less efficient at deleting such events.

To determine whether an increase in the deletion rate in other primate lineages might account for this difference, we performed two tests. First, we analyzed all large insertion/deletion events (>100 bp in length) for both baboon and chimpanzee comparisons. Three classes were distinguished: indels that were characteristic of a retrotransposition event (see above), those that were associated with a repetitive sequence at their junctions and were likely the result of a deletion event (Gilbert et al. 2002), and those that were not associated with repeats (nonrepeat-associated insertion/deletions, termed NRAIDs; Suppl. Table S5, Suppl. Fig. S7). No significant difference (P = 0.2–0.5, χ2 = 0.2–1.71; Suppl. Table S5) was observed in the number of indels in the latter two categories. In contrast, estimates in the number of new insertion events that arose as a result of retrotransposition were significantly different for each species comparison.

As a second test, we compared the mean genetic distance for lineage-specific Alus within both the human and lemur lineages. If a higher deletion rate were responsible for the depletion of repeats within the lemur lineage, we would expect the mean genetic distance for Alu repeats within lemur to be lower as the longevity of Alu insertions would be reduced—older Alu elements would be more likely to be deleted or truncated within a background of increased deletion. A comparison of lineage-specific full-length Alus in lemur (K = 0.258 ± 0.015, n = 30) and human (K = 0.284 ± 0.014, n = 239) reveals comparable levels of Alu diversity. Similarly, analysis of older repetitive elements (L2, L3, MIR, and DNA transposons) that are believed to have inserted before the separation of the two lineages shows virtually no difference in either count or the relative proportion in the human and lemur genomes (Suppl. Table S9A). Combined, these data strongly suggest that recent (<50 Mya) changes in the rates of retrotransposition as opposed to deletion are responsible for the expansion of the hominoid genome.

Our comparison of human and baboon genomic sequence to lemur shows the most dramatic expansion (15%–19%) in genome size (Fig. 2). In a previous study based on a sampling of DNA content from 15 stepsirhines and 48 haplorhines species, it was reported that the genomes of prosimian species were significantly smaller (9% decrease; 7.1 ± 0.2 pg vs. 7.8 ± 0.2 pg; Pellicciari et al. 1982). It was unknown, however, whether such differences were attributable to centric chromatin, which is known to be cytogenetically reduced in size among prosimians (Martin 1990). Our analysis of lemur and human data indicates that the difference is in fact euchromatic in nature and that it is almost exclusively repeat-derived (Fig. 3). All classes of younger retrotransposons (Alus, L1s, and LTR) contribute to this increase, whereas more ancient elements such as L2, L3, and DNA transposons do not contribute to this increase by differential deletion. Interestingly, although the number of Alu elements appears to be significantly increased, among the LTR and L1 elements, the average length of the insertion has increased whereas the number of such events has not. This effect is seen in both human and baboon compared to lemur. Assuming a divergence of human and baboon approximately 25 million years ago, the data would support a major increase in genome size due to an increase in retrotransposition fixation.

Summary

The analysis here provides a large-scale and unbiased assessment of primate genome variation. As such, it is expected that these data will serve as a valuable baseline for future studies of primate molecular evolution both at the level of single-nucleotide variation as well as that of retrotransposition. The human genome is particularly enriched in both number and length of retrotransposons. It has grown as a result of a major burst in Alu activity 25–55 million years ago and has subsequently continued to expand compared to more closely related primates, due to lineage-specific shifts in retroposon activity within the last 25 million years of evolution. Compared to every animal genome sequenced to date, the human genome is larger and harbors more repeats within its euchromatin. Since the rate of substitution is fundamentally lower and our generation time is longer compared to those species, such changes may have contributed to this repeat-enrichment. In this context, the finding that the human genome is significantly larger than that of the chimpanzee is unexpected. The mutation rate and generation time among the ancestors of these large-bodied hominoids are believed to have remained relatively constant (Ruvolo 1997; Webster et al. 2002), although the population history is believed to be radically different among these species. The repeat-associated reduction in the chimpanzee genome, however, is slight and must await further validation before being declared a general property. We cannot, for example, exclude the possibility that other rare and very large repetitive sequences (i.e., segmental duplications) may compensate for this difference. Nevertheless, it is interesting that similar expansions of smaller tandem microsatellites, such as dinucleotide and trinucelotide repeat sequences, have been reported (Cooper et al. 1998; Webster et al. 2002) in human compared to chimpanzee. Although the molecular basis for these differences is not well understood, combined the data support a repeat-driven expansion of our genome. Since such sequences have been shown to be potent mutagens at the structural as well as the genic level, it follows that their contribution to phenotypic change and evolution might be more significant than previously anticipated.

METHODS

Orthologous Sequences

Large genomic sequences (>50 kb in length) from chimpanzee (RP43), baboon (RP41), and lemur (LB2) were retrieved from GenBank. To provide high-quality large-scale genomic alignments, we limited our analysis to genomic sequences that were completely finished or where the sequence contigs were ordered and oriented. Sequence accessions were considered where there were fewer than three contigs and no internal ambiguous bases. Finished sequence was generated to the standards established for sequencing the human genome (see http://www.genome.wustl.edu/Overview/finrulesname.php?G16=1), which includes closure of all sequence gaps and achieving an estimated error rate of <1 in 10,000 bp (Felsenfeld et al. 1999). Among the working draft sequences, an analysis of the assembly quality revealed an ∼10–11-fold redundancy of high-quality bases (Phred Q> = 20). To search for orthologous sequences, we extracted segments longer than 50 kb in length and masked the sequences for common repeat elements (Smit 1999, http://repeatmasker.genome.washington.edu/cgi-bin/RepeatMasker). Because duplicated regions of the genome complicate identification of orthologous segments and confound genetic distance estimates (Chen et al. 2001), we excluded any accession if it was located within a known duplicated region of the human genome (Bailey et al. 2002, http://humanparalogy.gene.cwru.edu/SDD/index.htm).A total of 102 nonhuman primate accessions met these criteria, corresponding to nine lemur, 42 baboon, and 51 chimpanzee genomic clones. Nonhuman primate genomic sequence was generated almost exclusively by the U.S. National Institutes of Health Intramural Sequencing Center (http://www.nisc.nih.gov/open_page.html?staff.html). Ninety-nine of 102 of the sequences mapped to phylogenetic group chromosome 7 and were part of a targeted comparative sequencing effort to three gene-containing regions on chromosome 7 (Thomas et al. 2002). Five of the lemur genomic loci mapped to a gene-rich region near the CFTR locus on human 7q31. 2. The majority of nonhuman primate clones mapped primarily to two regions within 7p14.3 and 7q22.1 (positions 30,000,000–35,000,000 and 95,000,000–103,000,000 within build30, June 2002 assembly). A complete list of all accessions, their map location with respect to the human genome, and their sequence attributes are provided (http://eichlerlab.cwru.edu/primategenome/ and Suppl. Fig. S2, Suppl. Table S3). Orthologous human sequence was identified by sequence similarity searches (BLAST) of nonhuman primate sequence queried against a formatted version of the assembled human genome (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). Human genomic sequence underlying the assembly was obtained from GenBank accessions. Overlapping sequences within a species were excluded based on human genome assembly coordinates. Although only nine genomic regions are compared between human and lemur, each of these regions represents ∼70 kb of orthologous sequence. Our genomic analysis (Fig. 1, Suppl. Fig. S4), therefore, involves the analysis of more than 841 nonoverlapping blocks of 3 kb of genomic sequence. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that these datasets are sufficiently representative and robust enough to draw sound conclusions regarding rates and properties of primate genomic mutation. As a control for selection bias and rate variation among these genomic regions, we analyzed 1000 BAC-end sequences randomly selected from chimpanzee, baboon, and lemur BAC libraries. A comparison of these alignments to these large-scale genomic alignments showed comparable results (Results and Discussion).

Genomic Sequence Alignment

Orthologous sequence relationships between human and nonhuman primate genomic sequences were initially delineated using Miropeats (Parsons 1995, http://genome.wustl.edu/gsc/index.shtml), and the sequences were subsequently extracted using two_way_mirror (J. Bailey, unpubl.). We used the Myers-Miller algorithm (Myers and Miller 1988) to construct all optimal global alignments. One of the most significant challenges of large-scale genomic analyses is the generation of biologically meaningful global alignments (Chen et al. 2001). As sequence becomes increasingly divergent, the reliable treatment of insertion/deletions becomes particularly problematic. Ineffective treatment of insertion/deletions (indels) may lead to the formation of suboptimal global alignments providing erroneously higher estimates of sequence divergence. To establish the optimal parameters for global alignment, we initially analyzed a subset of large-scale sequence alignments between human, baboon, and lemur. Using the software ALIGN (Myers and Miller 1988), we tested a series of gap opening and extension penalties and their impact on the frequency of single-nucleotide and insertion/deletion events (Suppl. Fig. S1). For each species we selected parameters that minimized sequence divergence and the number of indels. For equally parsimonious gap parameters, we selected parameters (−f 50 −g 1) where known “young” retrotransposition events were treated as a single insertion/deletion event. All alignments were manually inspected for extreme fluctuations in genetic distance using align_slider_viewer (J. Bailey, unpubl.). A suboptimal alignment was defined as any alignment which exceeded two standard deviations of the mean genetic distance (window size 2 kb, slide 100 bp). These regions were considered separately in the analysis (Table 1). A total of six (16 kb), 23 (43 kb), and 17 (26 kb) such subalignments were classified as suboptimal for chimpanzee, baboon, and lemur comparisons to human, respectively. Altering gap parameters recovered approximately 50% of these suboptimal alignments for human–chimpanzee alignments but not for the other primate comparisons. Only a small fraction (<5%) of all aligned bases was classified as suboptimal. A total of 5.0, 5.0, and 0.62 Mb of genomic sequence was successfully aligned between human and chimpanzee, baboon, and lemur, respectively. We further constructed 19 multiple alignments for human, chimpanzee, and baboon (alignment length 2.5 Mb) and five multiple alignments for all four species (alignment length 0.51 Mb) using ClustalW. Tajima's relative rate tests were performed on these multiple alignments using MEGA. All alignments, including graphical assessments, are available online (http://eichlerlab.cwru.edu/primategenome/).

Genetic Distance Estimates

For all estimates of genetic distance (K; Table 1), we used Kimura's two-parameter method, which corrects for multiple events and transversion/transition mutational biases (Table 1; Kimura 1980). Insertion/deletion events were not factored into these calculations (Britten 2002). Repetitive, unique noncoding and exonic portions from the sequence alignments were extracted using MaM (Multiple Alignment Manipulator; Alkan et al. 2002, http://genomics.cwru.edu/MAM.html). Repeat coordinates were identified using the slow option of RepeatMasker v3.0. Five major classes of repeats were considered in this analysis (LINES, SINES, DNA Transposons, LTR, and simple repeats). To eliminate the possibility that more divergent or novel common repeats (particularly for the lemur) may not have been effectively masked by RepeatMasker, intraspecific sequence-similarity searches were performed. Exon definition was limited to well annoted human genes (NCBI RefSeq: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/LocusLink/refseq.html). Among these, a total of 460 coding exons corresponding to 52 genes were analyzed. Sliding window analyses (Fig. 1) were performed using align_slider (J. Bailey, unpubl.). Rates of substitution were calculated using K/2T, where human divergence times of 5.5, 25, and 55 million years ago were used for chimpanzee, baboon, and lemur alignments, respectively (Kumar and Hedges 1998; Goodman 1999). All alignment attributes were maintained within a mySQL database, which facilitated cross-referencing with various properties of the genomic sequence. DNA sequences corresponding to recent retroelements (Alu and L1) were extracted from the aligned sequences. Multiple sequence alignments were generated (ClustalW) and within-group and between-group estimates of genetic distance were calculated (MEGA2; Kumar et al. 2001).

Insertion/Deletion Analysis

Insertion/deletion (indel) events within the pairwise alignments were initially separated by length into two groups (<100 bp and ≥100 bp). This classification was based on the rationale that most retrotransposition events are greater than 100 bp in length, whereas the vast majority of the smaller events result from other mutational events (microsatellite variation, replication slippage, small local deletion events). More than 80% of all indels are equal to or less than 15 bp in length but contribute to less than 3.6% of the overall length differences within an alignment. This is in agreement with a recently published analysis (Britten 2002). A complete count of the total number of indels and their length distribution are available (Suppl. Table S5, Suppl. Fig. S6).

Large gaps (>100 bp) within a genomic pairwise alignment may occur as a result of a deletion in one species or an insertion in the other. Such events cannot, usually, be assigned. It is expected that, many such large events will be associated with a common repeat sequence due to homology-based deletion of repeat sequences (Gilbert et al. 2002) and retrotransposition-based insertion events. We therefore further subdivided indels (>100 bp) into one of two categories based on their association with a repeat sequence. We classified an indel as a retrotransposition if at least 80% of the indel contained one predominant repeat (LINE, SINE, LTR). We considered the known interspersed repeat phylogeny based on the established repeat subclasses as reported previously (Smit 1999). All insertions were considered including the ancient repeat subclasses that passed our test. Further, in the case of L1 and Alu repeats, insertion sequences were examined for the presence of target-site duplications and a polyadenylation tail at the site of integration. The vast majority of retroelements events are irreversible genetic character states (Perna et al. 1992; Deininger and Batzer 1999), and it is therefore highly unlikely that a deletion event would occur to precisely remove a retroelement during evolution. Unlike other insertion deletion events, then, the directionality of the event could be unambiguously assigned to a specific lineage (Table 2). Large indels in which one end or both ends were placed within a repetitive sequence were categorized separately (Suppl. Table S8).

Two basic statistical tests were performed during the analysis of indels. Differences in counts were assessed using the χ2 test based on the assumption that alignment parameters would not show a species preference for insertions. Differences in genomic length (insertion/deletions) were examined using a permutation test of the difference for both orthologous loci and for individual indels (>100 bp). Briefly, for each alignment, the greater length was randomly assigned between the two species of interest. P-values were defined as the fraction of replicates out of 10,000 which surpassed or equaled the observed length differences. These permutations were also done on an indel by indel basis by effectively assigning any given insertion or deletion to a species randomly. The sum was then compared to the observed length differences to determine the P-value. Permutation tests, therefore, were performed at the level of the total alignment as well as at the level of the individual insertion/deletion events.

WEB SITE REFERENCES

http://www.nisc.nih.gov/; NIH intramural sequencing center.

http://eichlerlab.cwru.edu/primategenome/; supplemental material: pairwise and multiple alignments.

http://www.genome.wustl.edu/Overview/finrulesname.php?G16=1; finishing standards for the human genome project.

http://repeatmasker.genome.washington.edu/cgi-bin/RepeatMasker; Repeatmasker Web server.

http://humanparalogy.gene.cwru.edu/SDD/index.htm; segmental duplication database at CWRU.

http://www.nisc.nih.gov/open_page.html?staff.html; NIH intramural sequencing center staff page.

http://genome.ucsc.edu/; UCSC genome bioinformatics site.

http://genome.wustl.edu/gsc/index.shtml; Genome sequencing center at Washington University.

http://genomics.cwru.edu/MAM.html; MaM download page at Center for Computational Genomics, CWRU.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/LocusLink/refseq.html; NCBI reference sequences.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Moran, M. Batzer, and A. Chakravarti for critical reading and helpful comments in the preparation of this manuscript. The following individuals were key contributors within the NISC Comparative Vertebrate Sequencing Program: Jim Thomas (BAC isolation and mapping), Jeff Touchman and Bob Blakesley (BAC sequencing), Gerry Bouffard, Steve Beckstrom-Sternberg, Jenny McDowell, and Baishali Maskeri (computational analyses), and Pam Thomas (sequence annotation). This work was supported in part by NIH grants GM58815 and HG002318 and U.S. Department of Energy grant ER62862 to E.E.E., a Human Genetics Training Grant (HD-07518-05), an NIH Career Development Program in Genomic Epidemiology of Cancer (CA094816), the W.M. Keck Foundation, and the Charles B. Wang Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

E-MAIL eee@po.cwru.edu, FAX (216) 368-3432.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.923303.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkan C., Tuzun, E., Eicher, E.E., Bailey, J.A., and Sahinalp, S.C., 2002. MaM: Multiple alignment manipulator. In Currents in computational molecular biology 2002., pp. 3–4. Celera Genomics, Rockville, MD.

- 2.Aparicio S., Chapman, J., Stupka, E., Putnam, N., Chia, J.M., Dehal, P., Christoffels, A., Rash, S., Hoon, S., Smit, A., et al. 2002. Whole-genome shotgun assembly and analysis of the genome of Fugu rubripes. Science 297: 1301-1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey J.A., Gu, Z., Clark, R.A., Reinert, K., Samonte, R.V., Schwartz, S., Adams, M.D., Myers, E.W., Li, P.W., and Eichler, E.E. 2002. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science 297: 1003-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey W.J., Fitch, D.H., Tagle, D.A., Czelusniak, J., Slightom, J.L., and Goodman, M. 1991. Molecular evolution of the ψ η-globin gene locus: Gibbon phylogeny and the hominoid slowdown. Mol. Biol. Evol. 8: 155-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batzer M.A. and Deininger, P.L. 2002. Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3: 370-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohossian H.B., Skaletsky, H., and Page, D.C. 2000. Unexpectedly similar rates of nucleotide substitution found in male and female hominids. Nature 406: 622-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Britten R.J. 2002. Divergence between samples of chimpanzee and human DNA sequences is 5%, counting indels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 13633-13635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen F.C. and Li, W.H. 2001. Genomic divergences between humans and other hominoids and the effective population size of the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68: 444-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen F.C., Vallender, E.J., Wang, H., Tzeng, C.S., and Li, W.H. 2001. Genomic divergence between human and chimpanzee estimated from large-scale alignments of genomic sequences. J. Hered. 92: 481-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiaromonte F., Yang, S., Elnitski, L., Yap, V.B., Miller, W., and Hardison, R.C. 2001. Association between divergence and interspersed repeats in mammalian noncoding genomic DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 14503-14508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper G., Rubinsztein, D.C., and Amos, W. 1998. Ascertainment bias cannot entirely account for human microsatellites being longer than their chimpanzee homologues. Hum. Mol. Genet. 7: 1425-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehal P., Predki, P., Olsen, A.S., Kobayashi, A., Folta, P., Lucas, S., Land, M., Terry, A., Ecale Zhou, C.L., Rash, S., et al. 2001. Human chromosome 19 and related regions in mouse: Conservative and lineage-specific evolution. Science 293: 104-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deininger P.L. and Batzer, M.A. 1999. Alu repeats and human disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 67: 183-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deininger P.L. and Batzer, M.A. 2002. Mammalian retroelements. Genome Res. 12: 1445-1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebersberger I., Metzler, D., Schwarz, C., and Paabo, S. 2002. Genomewide comparison of DNA sequences between humans and chimpanzees. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70: 1490-1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eichler E.E. and DeJong, P.J. 2002. Biomedical applications and studies of molecular evolution: A proposal for a primate genomic library resource. Genome Res. 12: 673-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felsenfeld A., Peterson, J., Schloss, J., and Guyer, M. 1999. Assessing the quality of the DNA sequence from the Human Genome Project. Genome Res. 9: 1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujiyama A., Watanabe, H., Toyoda, A., Taylor, T.D., Itoh, T., Tsai, S.F., Park, H.S., Yaspo, M.L., Lehrach, H., Chen, Z., et al. 2002. Construction and analysis of a human-chimpanzee comparative clone map. Science 295: 131-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert N., Lutz-Prigge, S., and Moran, J.V. 2002. Genomic deletions created upon LINE-1 retrotransposition. Cell 110: 315-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodman M. 1999. The genomic record of humankind's evolutionary roots. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 64: 31-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodman M., Barnabas, J., Matsuda, G., and Moore, G.W. 1971. Molecular evolution in the descent of man. Nature 233: 604-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horai S., Hayasaka, K., Kondo, R., Tsugane, K., and Takahata, N. 1995. Recent African origin of modern humans revealed by complete sequences of hominoid mitochondrial DNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92: 532-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurles M.E. 2001. Gene conversion homogenizes the CMT1A paralogous repeats. BMC Genomics 2: 11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium 2001. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409: 860-920. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaessmann H., Wiebe, V., and Paabo, S. 1999. Extensive nuclear DNA sequence diversity among chimpanzees. Science 286: 1159-1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16: 111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koop B.F., Miyamoto, M.M., Embury, J.E., Goodman, M., Czelusniak, J., and Slightom, J.L. 1986. Nucleotide sequence and evolution of the orangutan ε globin gene region and surrounding Alu repeats. J. Mol. Evol. 24: 94-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar S. and Hedges, S.B. 1998. A molecular timescale for vertebrate evolution. Nature 392: 917-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar S., Tamura, K., Jakobsen, I.B., and Nei, M. 2001. MEGA2: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics 17: 1244-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li W., 1997. Molecular evolution., pp. 177–213. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- 31.Li W.H. and Tanimura, M. 1987. The molecular clock runs more slowly in man than in apes and monkeys. Nature 326: 93-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin R.D., 1990. Primate origins and evolution: A phylogenetic reconstruction., pp. 558–559. University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- 33.Moran J.V., DeBerardinis, R.J., and Kazazian, H.H., Jr. 1999. Exon shuffling by L1 retrotransposition. Science 283: 1530-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mural R.J., Adams, M.D., Myers, E.W., Smith, H.O., Miklos, G.L., Wides, R., Halpern, A., Li, P.W., Sutton, G.G., Nadeau, J., et al. 2002. A comparison of whole-genome shotgun-derived mouse chromosome 16 and the human genome. Science 296: 1661-1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myers E.W. and Miller, W. 1988. Optimal alignments in linear space. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 4: 11-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parsons J. 1995. Miropeats: Graphical DNA sequence comparisons. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 11: 615-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pellicciari C., Formenti, D., Redi, C.A., and M.R., M.G. 1982. DNA content variability in primates. J. Hum. Evol. 11: 131-141. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perna N.T., Batzer, M.A., Deininger, P.L., and Stoneking, M. 1992. Alu insertion polymorphism: A new type of marker for human population studies. Hum. Biol. 64: 641-648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powell J.R. and Caccone, A. 1990. The TEACL method of DNA-DNA hybridization: Technical considerations. J. Mol. Evol. 30: 267-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruvolo M. 1997. Molecular phylogeny of the hominoids: Inferences from multiple independent DNA sequence data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 14: 248-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen M.-R., Batzer, M., and Deininger, P. 1991. Evolution of the master Alu gene(s). J. Mol. Evol. 33: 311-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sibley C.G. and Ahlquist, J.E. 1984. The phylogeny of the hominoid primates, as indicated by DNA-DNA hybridization. J. Mol. Evol. 20: 2-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sibley C.G., Comstock, J.A., and Ahlquist, J.E. 1990. DNA hybridization evidence of hominoid phylogeny: A reanalysis of the data. J. Mol. Evol. 30: 202-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smit A.F. 1999. Interspersed repeats and other mementos of transposable elements in mammalian genomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9: 657-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith J. 1992. Evolutionary biology. Byte-sized evolution. Nature 355: 772-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith N.G., Webster, M.T., and Ellegren, H. 2002. Deterministic mutation rate variation in the human genome. Genome Res. 12: 1350-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas J.W., Prasad, A.B., Summers, T.J., Lee-Lin, S.Q., Maduro, V.V., Idol, J.R., Ryan, J.F., Thomas, P.J., McDowell, J.C., and Green, E.D. 2002. Parallel construction of orthologous sequence-ready clone contig maps in multiple species. Genome Res. 12: 1277-1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Venter J.C., Adams, M.D., Myers, E.W., Li, P.W., Mural, R.J., Sutton, G.G., Smith, H.O., Yandell, M., Evans, C.A., Holt, R.A., et al. 2001. The sequence of the human genome. Science 291: 1304-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Webster M.T., Smith, N.G., and Ellegren, H. 2002. Microsatellite evolution inferred from human-chimpanzee genomic sequence alignments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 8748-8753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao S., Malek, J., Mahairas, G., Fu, L., Nierman, W., Venter, J.C., and Adams, M.D. 2000. Human BAC ends quality assessment and sequence analyses. Genomics 63: 321-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zuckerkandl E. and Pauling, L. 1965. Molecules as documents of evolutionary history. J. Theor. Biol. 8: 357-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]