Abstract

The Institute of Medicine, United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), and national healthcare organizations recommend screening and counseling for intimate partner violence (IPV) within the US healthcare setting. The Affordable Care Act includes screening and brief counseling for IPV as part of required free preventive services for women. Thus, IPV screening and counseling must be implemented safely and effectively throughout the healthcare delivery system. Health professional education is one strategy for increasing screening and counseling in healthcare settings, but studies on improving screening and counseling for other health conditions highlight the critical role of making changes within the healthcare delivery system to drive desired improvements in clinician screening practices and health outcomes.

This article outlines a systems approach to the implementation of IPV screening and counseling, with a focus on integrated health and advocacy service delivery to support identification and interventions, use of electronic health record (EHR) tools, and cross-sector partnerships. Practice and policy recommendations include (1) ensuring staff and clinician training in effective, client-centered IPV assessment that connects patients to support and services regardless of disclosure; (2) supporting enhancement of EHRs to prompt appropriate clinical care for IPV and facilitate capturing more detailed and standardized IPV data; and (3) integrating IPV care into quality and meaningful use measures. Research directions include studies across various health settings and populations, development of quality measures and patient-centered outcomes, and tests of multilevel approaches to improve the uptake and consistent implementation of evidence-informed IPV screening and counseling guidelines.

Introduction

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) highlighted the prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) and its devastating impact on women's health and recommended “screening and counseling for all women and adolescent girls for interpersonal and domestic violence in a culturally sensitive and supportive manner” in a report on clinical preventive services for women.1,2 The United States (US) Department of Health and Human Services followed with inclusion of screening and counseling for domestic violence in the “Women's Preventive Services Guidelines.”3 In 2013, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPTF) recommended health screening for IPV for all women of child-bearing age and provision of, or referral to, intervention services for women who screen positive.4 The Affordable Care Act includes IPV screening and brief counseling as part of required free preventive services for women; thus, such screening and counseling must be implemented safely and effectively throughout the health care delivery system.

The recommendation to include IPV screening in healthcare as routine practice is not new.5–10 Research indicates that screening and counseling for IPV can identify survivors and, in some cases, increase safety, reduce abuse, and improve clinical and social outcomes.11–19 Possible harms or unintended consequences of clinical assessment have been raised and considered in research trials, but thus far no evidence of such harm has emerged.19–21 Barriers for implementation of IPV screening and counseling are myriad, including clinician concerns about time; limited incentives for screening22; either nonexistent or poorly implemented policies to guide clinicians and practices in conducting screening; lack of knowledge and confidence about how to support a patient who discloses IPV,23–27 which may reflect lack of reliable intervention services28; and inadequate cross-sector collaborations with victim service advocates.29,30 Addressing barriers and improving screening, counseling, and referral practices require attention to multiple levels within the healthcare delivery system to create a safe, trusting environment for patients.31 Strategies include provider education,29,32–34 patient support and engagement, policies and protocols for clinical settings,34–37 collaboration with IPV advocates, as well as environmental cues, reminders within the electronic health record (EHR), and quality incentives integrated into clinic flow.34,38 Studies are needed on how to implement clinical guidelines for IPV screening and assessment, with attention to barriers and strategies to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of screening, counseling, and referral processes.

Although health professional education is one core strategy for increasing IPV screening and counseling in the clinical setting,39–42 studies on screening and counseling for other health conditions highlight the critical role of changes at the healthcare system level to drive desired improvements in clinician screening practices.43–46 This article outlines a systems approach to the implementation of IPV screening and counseling, with a focus on integrated health and advocacy service delivery, use of EHR tools and cross-sector partnerships, and identifies areas for research on approaches to improve the uptake and consistent implementation of these IPV screening and counseling guidelines in the United States.47–49

IPV Screening and Interventions

“Screening” in public health refers to the use of a test, examination, or other procedure rapidly applied in an asymptomatic population to identify individuals with early disease. Although the intention is to identify “asymptomatic” and “early” IPV to prevent morbidity and mortality, IPV is such a stigmatized social problem that many victims may not be truly “asymptomatic” when screened, simply hidden. In fact, the health impact may be quite advanced. Thus, “screening” in the traditional sense is not consistent with what happens in the clinical encounter; the screening procedure refers more to empathic inquiry and may or may not include a standardized question. When risk or exposure to past or current IPV is assessed through such inquiry, the impact of the encounter can be primary prevention for patients with no history of exposure, secondary prevention for patients with past exposure, or tertiary prevention (i.e., early intervention) for patients with current or acute exposure.11,50–52

The health professional and patient interface

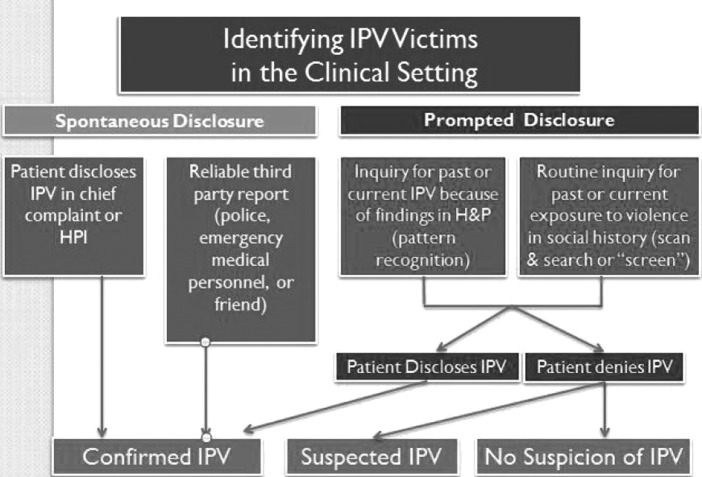

IPV may be identified in the clinical setting because either the patient or a third party, such as police or emergency medical services (EMS) personnel, discloses IPV or because the health professional inquires about past or current exposure (Fig. 1). Assessment for past or current IPV can occur through direct questioning as part of a routine health survey (patient or provider-delivered) or through pattern recognition when signs and symptoms in the history and physical exam alert the clinician to explore the possibility of IPV. Even when IPV is clinically suspected, patients may not disclose IPV for myriad reasons. In addition to the usual dichotomy of positive IPV and negative IPV cases, there is a third category of no disclosure but suspected IPV patients who could benefit from connections to support and services. Routine inquiry with provision of information about IPV-related resources for all patients, regardless of disclosure, may be particularly meaningful for this category of patients and has been associated with an increase in patient satisfaction with healthcare services.31,48,53

FIG. 1.

Identifying intimate partner violence victims in the clinical setting. H&P, history and physical; HPI, history of present illness; IPV, intimate partner violence.

Each patient group should have tailored interventions with different objectives, guided by the patient's desires and context. Factors such as patient safety, privacy, and legal issues must be considered, and the duality of perpetrator and victim (and often children) means that interventions are not isolated just to the victim. Additionally, IPV can be of one type or mixed, meaning that patients may be experiencing physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological abuse, and/or unspecified maltreatment. These are just some of the reasons that research about screening and interventions for IPV is complex and challenging.18 The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) supports more detailed diagnostic codes for IPV exposure and suspected or confirmed IPV, and robust EHRs (with careful attention to confidentiality) should promote the capture of more specific IPV diagnostic and treatment data.

Many research questions remain unanswered regarding the range of optimal approaches to IPV screening.54 These questions include comparisons of methods of inquiry (verbal, written, online); the effectiveness of and clients' satisfaction with standard questions compared to conversational inquiry; differences in approaches needed across clinical settings and with different populations, such as with male victims, adolescents, sexual minority individuals, or elders; and validity of screening strategies in various languages and cultures.

Systems considerations

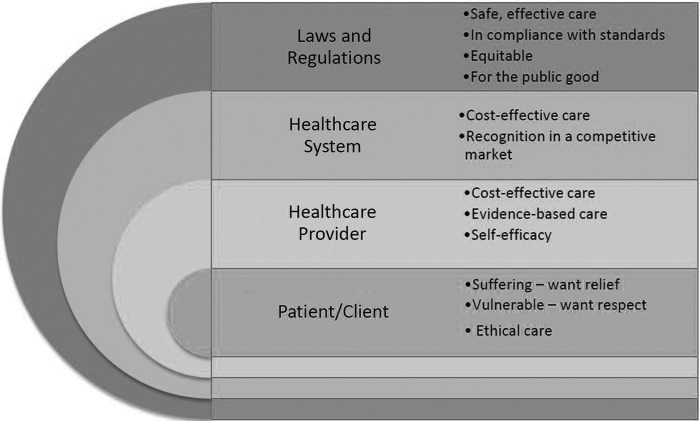

Within the healthcare delivery system, then, what are the best practices for addressing IPV to provide effective intervention and help prevent further harm? Figure 2 highlights the multiple levels to consider when implementing IPV screening and counseling interventions, as provider, healthcare system, and regulatory goals and constraints need to align with one another and with patients' needs and desires. What is at stake varies at each level for different stakeholders. Implementation of IPV screening and counseling requires an integrated response within a healthcare delivery system with buy-in from clients and health professionals to health system leaders and policy makers. Individuals exposed to IPV may seek care in multiple healthcare settings; each setting needs to have the capacity and motivation to identify, support, and connect patients to services. Such a systems-based approach emphasizes not only health provider education but also policies, protocols, and institutional supports within the healthcare delivery system to facilitate implementation of routine IPV screening and counseling and connection to advocacy services.

FIG. 2.

Systems considerations in IPV screening.

Simultaneously, a systems-based approach highlights the need for cross-sector collaboration and community partnerships. Staff and clinicians within the healthcare delivery system can be connected to community and victim advocacy service providers who can support patients exposed to IPV, and those relationships can be incentivized and encouraged. Practice-based evidence and research on systems-based interventions underscore the extent to which integration of IPV assessment into routine care can be accelerated with various tools. Monitoring and tracking improvements for patients and healthcare providers should be part of systems-based practice changes, such that continuous quality improvement and ongoing performance evaluation among staff are expected.37,49,55

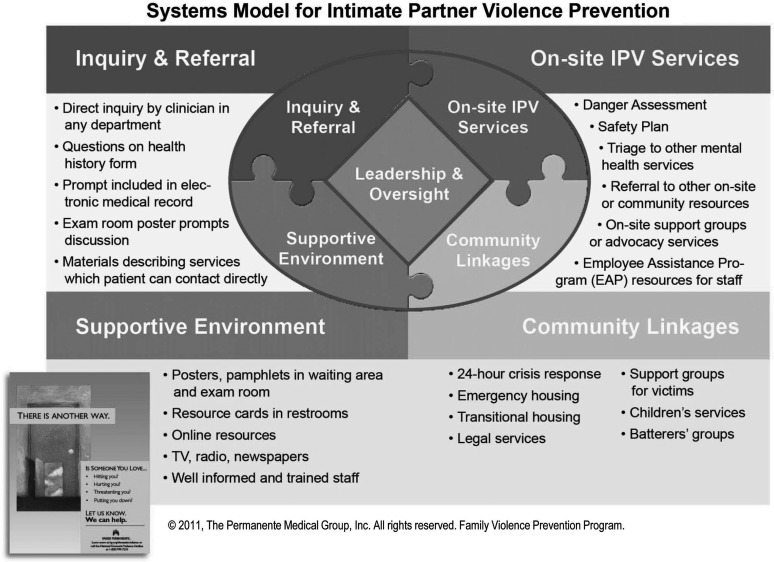

The Kaiser Permanente Systems Model

An example of systems-based implementation is Kaiser Permanente (KP), the largest nonprofit health plan in the United States, with 9.2 million members, 18,000 physicians, and an integrated system of care that includes ambulatory and hospital services and a fully implemented EHR. The KP Systems Model approach,53,55 which makes use of the entire healthcare environment (see Fig. 3) for improving IPV services, has been associated with an eightfold increase in IPV identification between 2000 and 2013 in KP's Northern California Region.49,53 Steps for implementing this approach have been described,48,49,53,55–57 and this model is currently being adopted in other health settings. Frequent, brief, focused IPV training; a clear care path for identification and response; and a reliable referral process for on-site behavioral health and to community advocacy services have increased clinician confidence and competence in IPV inquiry and intervention. Tools linked to the EHR facilitate IPV inquiry and response, give clinicians convenient access to best practices at the point of care,58 and have facilitated dissemination of the Systems Model across clinical departments and KP medical centers.53 KP members also report satisfaction with seeing IPV-related brochures and posters in clinics and having clinicians routinely ask about family relationships and IPV.

FIG. 3.

Systems model for intimate partner violence prevention. (Previous version of this diagram was published in Decker MR, Frattaroli S, McCaw B, et al. Transforming the healthcare response to intimate partner violence and taking best practices to scale. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012; 21:1222–1229.)

EHR tools to support clinicians

EHR tools that facilitate screening for IPV include Best Practice Alerts (BPA), which are visible when the clinician opens a patient's electronic chart. BPAs can provide simple reminders to screen, offer specific questions to ask, and contain links to practice guidelines. Logic functions can be used to trigger BPA based on gender, age, type of visit (e.g., annual checkup), pattern of utilization, or chief complaint (e.g., injury).

Progress Note templates with prepopulated elements help integrate IPV assessment into routine visits and facilitate consistency in assessment. For example, the KP Gynecology Progress Note embeds a reminder to ask about current IPV, past IPV, and reproductive coercion. The KP Prenatal Evaluation Progress Note prompts specific questions on IPV, which facilitates routine inquiry and consistent documentation. When a clinician is with a patient and IPV is identified, EHR “Smart Links” offer easy-to-access practice recommendations, the danger-assessment questionnaire, safety plan tips, and IPV community resources. This system, embedded in clinical practice, also facilitates accurate coding, documentation, and follow-up.58 The KP integrated health delivery system protects confidentiality of documentation related to IPV by including IPV among other “sensitive” diagnoses that are not visible on after-visit summaries, billing statements, or online patient portals.59

EHR as a tool for continuous quality improvement

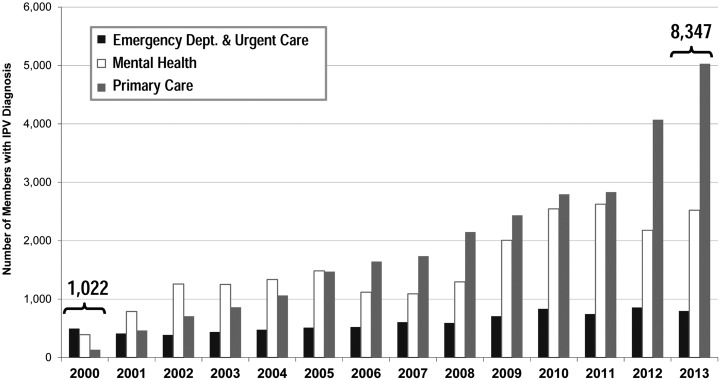

Another example of EHR functionality applied to IPV assessment is the use of automated, deidentified diagnostic databases for continuous quality improvement (CQI). Most healthcare settings already do this for such conditions as asthma, hypertension, and diabetes. For example, by using ICD codes for IPV and existing automated data systems, KP has been able to track progress over time in identification of IPV (Fig. 4). More granular data comparing departments, clinics, and medical centers demonstrate the impact of new approaches to screening and help identify best practices.60 Aggregated data using elements routinely documented in the EHR (such as gender, age, ethnicity, smoking status, and body mass index [BMI]) provide descriptive statistics of the population of patients identified with IPV and can guide enhancement of clinical services.

FIG. 4.

Members diagnosed with intimate partner violence, 2000–2013. (Previous version of this diagram was published in Decker MR, Frattaroli S, McCaw B, et al. Transforming the healthcare response to intimate partner violence and taking best practices to scale. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012; 21:1222–1229.)

EHR as a tool for research networks

Exciting opportunities exist for US research networks to use deidentified data from the EHR to facilitate multicenter research while protecting patient privacy in the area of IPV. This kind of collaboration has already shown success in many areas: vaccination safety, chemotherapy protocols for cancer treatment, and management of chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease. For IPV, research questions could include risk stratification, comparative effectiveness of clinical interventions, long-term clinical outcomes, and effective implementation strategies. EHRs and standard instruments to generate appropriate codes for IPV counseling and diagnoses (i.e., with ICD-10-CM codes) based on clinician and patient input may improve the data available for CQI, institutional-practice tracking, research, or public health surveillance.

Health Information Technology and IPV Screening and Counseling

As the KP experience illustrates, the combination of clinician training, a robust EHR system, and an integrated system of care supports effective IPV screening, prevention, and intervention in the course of routine healthcare delivery. Current US federal government initiatives related to health information technology (IT) and healthcare delivery (e.g., broader health insurance coverage, accountable care organizations, and patient-centered research networks) should increase the percentage of patients treated in environments with these propitious factors.

Use of certified EHRs within US hospitals and clinics has substantially increased since enactment of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) provisions of the American Recovery and Revitalization Act in 2009. Under HITECH, Medicare- and Medicaid-eligible hospitals and health professionals may receive incentive payments (and later avoid penalties) if they use certified EHR products and required standards (e.g., terminology and record exchange) to meet specific EHR use criteria, thereby demonstrating “meaningful use” of EHRs. As more hospitals and health practices implement EHRs with certain standard capabilities and as requirements for interoperability escalate, more standardized electronic data will become available as a by-product of routine care. Certified EHRs will support increasingly robust standard data import and export mechanisms, standard interfaces to clinical decision-support tools, and methods for enabling special structured data capture60,61 (e.g., for screening instruments, research protocols, and patient-reported outcomes). Ability to analyze EHR data across time and care settings may provide another tool for improving IPV interventions.62

While progress is made toward widespread implementation of more capable and standardized EHRs, work should proceed on ensuring that validated IPV assessment strategies and decision-support algorithms are ready for implementation in such systems. Steps include verifying that intellectual property restrictions will not prevent broad implementation within EHR systems, ensuring that concepts in key instruments and decision-support algorithms are represented in required terminology standards, and promoting community consensus on a smaller number of preferred approaches for IPV screening and counseling to increase data comparability across sites. Paramount to these discussions is the value of coordination of care, as well as attention to survivors' privacy, confidentiality, and safety. These steps may facilitate the inclusion of an IPV assessment measure in a future edition of meaningful-use requirements.59

Healthcare Community Partnerships with Victim Advocacy and Services

As noted, assessment for IPV should become routinized through prompts in the EHR or other quality-improvement methods. Clinical staff can offer patients information about IPV-related services, regardless of any disclosure, in addition to conducting assessment for IPV during the clinical encounter. As the goal for IPV screening and counseling shifts from a sole focus on identification to creating safer spaces for patients within the healthcare delivery system, the clinical space transforms into a place to build connections to supports, services, and protection. Evidence suggests that when healthcare providers facilitate the connection for their patients to an advocate (e.g., assist with making a phone call or connecting to an advocate)—called a warm referral in practice—patients are more likely to use an intervention.16,63,64 Health providers report, however, that they often are unfamiliar with resources and do not know what to do if a patient discloses IPV to them.12,28,51,65–68 Unfortunately, little guidance exists on how to build these connections with victim-advocacy services, how to strengthen local connections, and how to nurture a collaborative relationship.

One example, a universal education and brief counseling intervention for female clients seeking care in family planning (FP) clinics, incorporates an introduction to local advocates as part of the clinician and staff training at each clinical site. The intervention provides universal assessment for all female FP clients about IPV and reproductive coercion, which provides both screening and education, discussion of harm-reduction strategies to reduce risk for unintended pregnancy and IPV, and lets women know that the clinic can help make referrals to IPV-support services (supported referrals). All women are offered a safety card (or several to share with their friends) with information about harm-reduction strategies and national hotline numbers. An evaluation of this program followed women for 4 months and identified a 71% reduction in pregnancy pressure (a key element of reproductive coercion) among women experiencing recent IPV. Moreover, women receiving the intervention were also 60% more likely to end a relationship because it felt unhealthy or unsafe.17 During training to deliver this intervention, providers meet with designated advocates from local support services to enhance the referral system. Finally, the emphasis on harm reduction and connection of FP clinics with IPV services underscores that the FP clinic is a safe place for all women to seek care for unhealthy relationships. As in the KP model, patients who disclose abuse can receive immediate support. Further study is needed to identify best practices to scale these kinds of cross-sector partnerships.

Policy, Practice, and Research Recommendations

Based on current evidence supporting systems-based approaches to IPV in US clinical settings to improve health outcomes, policy recommendations to advance healthcare interventions for victims of IPV include the following:

• Ensure staff and clinician training in effective, client-centered, confidential IPV assessment that connects patients to support and services regardless of disclosure.

• Support development and implementation of EHR prompts, such as Best Practice Alerts and Progress Notes Templates, for IPV to prompt and guide clinical care.

• Eliminate barriers to EHR use for IPV assessment, such as intellectual property restrictions and lack of standardized terminology, and increase opportunities for coordination of care with attention to privacy, confidentiality, and safety for IPV victims.

• Include an IPV assessment measure in a future edition of meaningful-use requirements.

• Use EHRs to facilitate capture of detailed IPV data, at least at the level of appropriate ICD-10-CM codes.

Practice recommendations, also specific to the US healthcare setting, are centered on three areas:

• Provide clinicians with best-practice guidelines, decision-support tools, and resources to guide them when IPV is disclosed.

• Foster intentional collaborations with victim-service advocates with shared protocols for making “warm referrals.”

• Integrate IPV identification and intervention into quality-improvement efforts with data tracking (such as frequency of screening and brief counseling) and feedback on performance (such as patient satisfaction with the clinical encounter and connections made to victim advocacy services).

As IPV screening and interventions are further integrated into the US healthcare delivery system, several broad research questions emerge.

• Are current strategies for IPV assessment and interventions effective across diverse clinical settings; among various populations, such as with male victims, adolescents, sexual-minority individuals, or elders, or in various languages and cultures? How might a systems-based approach be adapted in resource-limited settings?

• How should quality of IPV assessment and care be measured? What are the most relevant patient-centered outcomes that should be incorporated into evaluation of health care interventions for IPV (i.e., outcomes that are most meaningful for survivors of IPV)? What is the role for educational and clinician decision aids?

• What role can the EHR have in improving the healthcare response to IPV, including facilitating quality improvement and spread of best practices? What health systems–level implementation approaches are associated with increased identification and improved outcomes?

With current attention to preventive services that include IPV screening and counseling for women, researchers and advocates in the United States have an unprecedented opportunity to work together to build the evidence base to ensure that women receive the highest quality care no matter where they access health services.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported in part by funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD064407, Miller). This work was supported in part by the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Library of Medicine (NLM).

We wish to thank Samia Noursi, MD, and Lisa Begg, MD, for their input and critical review of this manuscript. We also thank Claire Raible for her assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Clinical preventive services for women: Closing the gaps. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gee RE, Brindis CD, Diaz A, et al. Recommendations of the IOM clinical preventive services for women committee: Implications for obstetricians and gynecologists. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2011;23:471–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coverage of certain preventive services under the Affordable Care Act. Final rules. Fed Regist 2013;78:39869–39899 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moyer VA. Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:478–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Screening tools—Domestic violence. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2013. Available at: http://www.acog.org/About%20ACOG/ACOG%20Departments/Violence%20Against%20Women/Screening%20Tools%20%20Domestic%20Violence.aspx (accessed on October20, 2014)

- 6.Lee D, James L, Sawires P. Preventing domestic violence: Clinical guidelines on routine screening. San Francisco, CA: The Family Violence Prevention Fund, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark OW, Glasson J, August AM, et al. Physicians and domestic violence. Ethical considerations. JAMA 1992;267:3190–3193 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Position statement on physical violence against women. The American Nurse 1992;24:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anglin D. Diagnosis through disclosure and pattern recognition. In: Mitchell C, Anglin D, eds. Intimate partner violence: A health-based perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009:87–104 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taft A, O'Doherty L, Hegarty K, Ramsay J, Davidson L, Feder G. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;4:CD007007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez M, Quiroga S, Bauer H. Breaking the silence: Battered women's perspectives on medical care. Arch Family Med 1996;5:153–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez MA, Bauer HM, McLoughlin E, Grumbach K. Screening and intervention for intimate partner abuse: Practices and attitudes of primary care physicians. JAMA 1999;282:468–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang JC, Decker M, Moracco KE, Martin SL, Petersen R, Frasier PY. What happens when health care providers ask about intimate partner violence? A description of consequences from the perspectives of female survivors. J Am Med Womens Assoc 2003;58:76–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhodes KV, Levinson W. Interventions for intimate partner violence against women: Clinical applications. JAMA 2003;289:601–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFarlane J, Soeken K, Wiist W. An evaluation of interventions to decrease intimate partner violence to pregnant women. Public Health Nurs 2000;17:443–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCloskey LA, Lichter E, Williams C, Gerber M, Wittenberg E, Ganz M. Assessing intimate partner violence in health care settings leads to women's receipt of interventions and improved health. Public Health Rep 2006;121:435–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. A family planning clinic partner violence intervention to reduce risk associated with reproductive coercion. Contraception 2011;83:274–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bair-Merritt MH, Lewis-O'Connor A, Goel S, et al. Primary care-based interventions for intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2014;46:188–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hegarty K, O'Doherty L, Taft A, et al. Screening and counselling in the primary care setting for women who have experienced intimate partner violence (WEAVE): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;382:249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houry D, Kaslow NJ, Kemball RS, et al. Does screening in the emergency department hurt or help victims of intimate partner violence? Ann Emerg Med 2008;51:433–442, 42.e1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Jamieson E, et al. Approaches to screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: A randomized trial. JAMA 2006;296:530–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colarossi LG, Breitbart V, Betancourt GS. Screening for intimate partner violence in reproductive health centers: An evaluation study. Women Health 2010;50:313–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaffee KD, Epling JW, Grant W, Ghandour RM, Callendar E. Physician-identified barriers to intimate partner violence screening. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005;14:713–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yonaka L, Yoder MK, Darrow JB, Sherck JP. Barriers to screening for domestic violence in the emergency department. J Contin Educ Nurs 2007;38:37–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cha S, Masho SW. Intimate partner violence and utilization of prenatal care in the United States. J Interpers Violence 2014;29:911–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tower M, McMurray A, Rowe J, Wallis M. Domestic violence, health & health care: Women's accounts of their experiences. Contemp Nurse 2006;21:186–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weeks EK, Ellis SD, Lichstein PR, Bonds DE. Does health care provider screening for domestic violence vary by race and income? Violence Against Women 2008;14:844–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minsky-Kelly D, Hamberger LK, Pape DA, Wolff M. We've had training, now what? Qualitative analysis of barriers to domestic violence screening and referral in a health care setting. J Interpers Violence 2005;20:1288–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Campo P, Kirst M, Tsamis C, Chambers C, Ahmad F. Implementing successful intimate partner violence screening programs in health care settings: Evidence generated from a realist-informed systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:855–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhodes KV, Frankel RM, Levinthal N, Prenoveau E, Bailey J, Levinson W. “You're not a victim of domestic violence, are you?” Provider patient communication about domestic violence. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:620–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCaw B, Berman WH, Syme SL, Hunkeler EF. Beyond screening for domestic violence: A systems model approach in a managed care setting. Am J Prev Med 2001;21:170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNulty A, Andrews P, Bonner M. Can screening for domestic violence be introduced successfully in a sexual health clinic? Sex Health 2006;3:179–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamberger KL, Guse C, Boerger J, Minsky D, Pape D, Folsom C. Evaluation of a health care provider training program to identify and help partner violence victims. Journal of Family Violence 2004;19:1–11 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamberger KL, Phelan MB. Domestic violence screening in medical and mental health care settings: Overcoming barriers to screening, identifying and helping partner violence victims. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 2006;13:61–99 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coker AL, Flerx VC, Smith PH, Whitaker DJ, Fadden MK, Williams M. Intimate partner violence incidence and continuation in a primary care screening program. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:821–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scholle SH, Buranosky R, Hanusa BH, Ranieri L, Dowd K, Valappil B. Routine screening for intimate partner violence in an obstetrics and gynecology clinic. Am J Public Health 2003;93:1070–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thurston WE, Tutty LM, Eisener AE, Lalonde L, Belenky C, Osborne B. Domestic violence screening rates in a community health center urgent care clinic. Res Nursing Health 2007;30:611–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sprague S, Swinton M, Madden K, et al. Barriers to and facilitators for screening women for intimate partner violence in surgical fracture clinics: A qualitative descriptive approach. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cornuz J, Humair JP, Seematter L, et al. Efficacy of resident training in smoking cessation: A randomized, controlled trial of a program based on application of behavioral theory and practice with standardized patients. Ann Internal Med 2002;136:429–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A review. Addiction 1993;88:315–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: A systematic review. Addiction 2001;96:1725–1742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steptoe A, Kerry S, Rink E, Hilton S. The impact of behavioral counseling on stage of change in fat intake, physical activity, and cigarette smoking in adults at increased risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Public Health 2001;91:265–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: A systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ 2005;330:765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Briss P, Rimer B, Reilley B, et al. Promoting informed decisions about cancer screening in communities and healthcare systems. Am J Prev Med 2004;26:67–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salber PR, McCaw B. Barriers to screening for intimate partner violence: Time to reframe the question. Am J Prev Med 2000;19:276–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson RS, Taplin SH, McAfee TA, Mandelson MT, Smith AE. Primary and secondary prevention services in clinical practice. Twenty years' experience in development, implementation, and evaluation. JAMA 1995;273:1130–1135 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson RS, Rivara FP, Thompson DC, et al. Identification and management of domestic violence: A randomized trial. Am J Prev Med 2000;19:253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCaw B, Kotz K. Family violence prevention program: Another way to save a life. Perm J 2005;9:65–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCaw B, Kotz K. Developing a health system response to intimate partner violence. In: Mitchell CM, Anglin D, eds. Intimate partner violence: A health-based perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009:419–428 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gerbert B, Johnston K, Caspers N, Bleecker T, Woods A, Rosenbaum A. Experiences of battered women in health care settings: A qualitative study. Women Health 1996;24:1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCauley J, Yurk RA, Jenckes MW, Ford DE. Inside “Pandora's box”: Abused women's experiences with clinicians and health services. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:549–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Caralis P, Musialowski R. Women's experiences with domestic violence and their attitudes and expectations regarding medical care of abuse victims. South Med J 1997;90:1075–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCaw B. Using a systems-model approach to improving IPV services in a large health care organization. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feder G, Ramsay J, Dunne D, et al. How far does screening women for domestic (partner) violence in different health-care settings meet criteria for a screening programme? Systematic reviews of nine UK National Screening Committee criteria. Health Technol Assess 2009;13:iii–iv, xi–xiii, 1–113, 137–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Decker MR, Frattaroli S, McCaw B, et al. Transforming the healthcare response to intimate partner violence and taking best practices to scale. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:1222–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCaw B. Family Violence Prevention Program significantly improves ability to identify and facilitate treatment for patients affected by domestic violence. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ): Service Delivery Innovation Profile 2014. Available at: https://innovations.ahrq.gov/profiles/family-violence-prevention-program-significantly-improves-ability-identify-and-facilitate (accessed on October20, 2014)

- 57.Kaiser Permanente Policy Story. Transforming the health care response to domestic violence 2012;1:1–2. Available at: http://www.kpihp.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/KP-Story-1.10-DomesticViolenceUPDATED-10-142.pdf (accessed on October20, 2014)

- 58.Ahmed AT, McCaw BR. Mental health services utilization among women experiencing intimate partner violence. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:731–738 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Institute of Medicine. Capturing social and behavioral domains in electronic health records: Phase 1 report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bhargava R, Temkin TL, Fireman BH, et al. A predictive model to help identify intimate partner violence based on diagnoses and phone calls. Am J Prev Med 2011;41:129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Standards and Interoperability (S&I) Framework. Structured Data Captured Charter and Members. Available at: http://wiki.siframework.org/Structured+Data+Capture+Charter+and+Members (accessed on October20, 2014)

- 62.Reis BY, Kohane IS, Mandl KD. Longitudinal histories as predictors of future diagnoses of domestic abuse: Modelling study. BMJ 2009;339:b3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hathaway JE, Willis G, Zimmer B. Listening to survivors' voices: Addressing partner abuse in the health care setting. Violence Against Women 2002;8:687–719 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feder G, Davies RA, Baird K, et al. Identification and Referral to Improve Safety (IRIS) of women experiencing domestic violence with a primary care training and support programme: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;378:1788–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sugg NK, Inui T. Primary care physicians' response to domestic violence. Opening Pandora's box. JAMA 1992;267:3157–3160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Siegel RM, Hill TD, Henderson VA, Ernst HM, Boat BW. Screening for domestic violence in the community pediatric setting. Pediatrics 1999;104:874–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Friedman LS, Samet JH, Roberts MS, Hudlin M, Hans P. Inquiry about victimization experiences. A survey of patient preferences and physician practices. Arch Intern Med 1992;152:1186–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Erickson MJ, Hill TD, Siegel RM. Barriers to domestic violence screening in the pediatric setting. Pediatrics 2001;108:98–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]