Abstract

Objectives.

This paper introduces scales on shared activity and relationship quality for married and partnered older adults using multiple indicators from the second wave of National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project.

Method.

We assessed the reliability of the scales using Cronbach’s alpha and the item-total correlation. We conducted exploratory factor analysis to explore the structure of the items and compared the distribution of each scale means by age group and gender.

Results.

We found that the relational quality scale has a 2-factor structure, including a positive and negative dimension. The shared activity scale has a 1-factor structure. We found that partnered men show both higher positive and higher negative relationship quality than do partnered women, suggesting that more older men than women experience ambivalent feelings toward their spouse or partner and more women than men have relationships of indifferent quality, with relatively low costs and relatively low benefits.

Discussion.

The separate conceptualization of shared activity and relationship quality provides one way to examine the dynamic nature of marital quality in later life such as the extent to which shared activities among couples promote or detract from relationships’ quality. Analyses for individuals and for dyads are discussed.

Key Words: Dyads, Relationship quality, Shared activity.

Being married or living with a partner in late life has been widely documented to protect health. Married men and women tend to face lower risks of mortality and report better physical and mental health and greater overall happiness than those otherwise like them who are not married or partnered (Waite & Gallagher, 2001). However, the benefits of marriage depend on the quality of the relationship. Indeed, lower quality relationships generally are no more beneficial than being single (Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, 2006; Williams, 2003). More recently, studies have begun to focus on multiple dimensions of marital or partnered relationships, incorporating positive and negative experiences (Umberson et al., 2006; Warner & Kelley-Moore, 2012). However, information on the relationship from the perspective of both members of the couple has generally been available only for small, nonrepresentative samples (Gottman, Coan, Carrere, & Swanson, 1998; Karney & Bradbury, 1997; Wallerstein & Blakeslee, 1995). For this reason, scholars typically have assessed relationship quality from the perspective of only one member of the couple. In addition, we know little about the shared activities that characterize older couples, how these change with age, and how they differ for older men and older women.

This paper introduces measures of shared activity and relationship quality for older adults in married or partnered relationships in Wave 2 (W2) of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP). The measures are taken from multiple sections of the NSHAP interview, including the reported history of the partnership, as well as questions on social networks, social support, and sexual relationships. We provide descriptive statistics on each measure and develop and evaluate scales as appropriate. We focus here on measures available for couples who were married or living together in NSHAP W2.

Previous studies on marital quality have emphasized the importance of distinguishing different dimensions of marital relationships (Bookwala & Franks, 2005; Fincham & Linfield, 1997; Glenn, 1990; Johnson, White, Edwards, & Booth, 1986). These studies have relied on a two-dimensional approach: a positive dimension, which captures features such as happiness with the relationship and emotional closeness, and a negative dimension, which includes conflict, criticism, and distance. The theoretical and empirical importance of distinguishing positive and negative dimensions is well documented (Bradbury, Frank, & Beach, 2000) because it allows us to identify ambivalent relationships (i.e., those who score high on both positive and negative dimensions) or indifferent relationships (i.e., those who score low on both positive and negative dimensions) (Fincham & Linfield, 1997). In addition, some studies distinguishing positive and negative dimensions show that, in general, men are more sensitive to positive aspects of relationships, whereas women are more responsive to negative features (Fincham & Linfield, 1997).

Although this focus on identifying and measuring both positive and negative dimensions of relationship quality and functioning is theoretically and empirically valuable, it may fail to capture important characteristics of marital and cohabitating relationships. Studies on broader social relationships have emphasized the importance of distinguishing the structural properties of relationships from their content (Haines & Hurlbert, 1992; House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988). These studies argue that these are distinct concepts independently associated with many aspects of individuals’ lives, including health outcomes, because the structure of relationships can be conducive to positive as well as negative outcomes (Haines, Beggs, & Hurlbert, 2008). However, the vast majority of studies of relationship functioning rely primarily or solely on evaluations by individuals (Bookwala, 2011; Kamp Dush & Taylor, 2012; Umberson et al., 2006; Warner & Kelley-Moore, 2012). A separate but small research literature assesses relationship functioning in controlled settings by videotaping couples engaged in a task such as discussing an issue on which they disagree. The exchange is rated by trained coders on various dimensions to evaluate couple functioning (Gottman et al., 1998; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Some previous studies incorporated items on activities, but these items were usually a part of the broader items assessing the quality of relationships in particular, as part of the positive dimension (Johnson et al., 1986). As a result, it is unclear whether and to what extent activities shared by members of a couple constitute a dimension of relationship functioning and quality (Lee & Waite, 2010).

A “structural property” of social networks is defined as the relationships between the focal person and two or more other members who participate in the network. These include network size, density, and the frequency of contact between network members (House et al., 1988). We argue that the notion of structural property can be extended to marital and cohabiting couples by focusing on the activities shared by husbands and wives (or partners). In this conceptualization, the structural properties of couple relationships are distinct from relationship quality. In contrast to the established approach which shows that marital interaction is a part of the positive dimension of marital/relationships quality (Johnson et al., 1986), we argue that the shared activity is a distinct dimension that could be conducive to both positive and negative dimension of marital/relationship quality.

Method

Partnered Relationships in NSHAP

Partnered relationships can take various forms, including marriage, cohabitation, dating, and more casual or transient relationships. In NSHAP, respondents are asked about their marital status at the beginning of the interview. In W2, all respondents (including those interviewed in W1) were asked about their current marital/cohabitational/partnership status (Waite, L. J., Cagney, K., Dale, W., Huang, E., Laumann, E. O., McClintock, M., O’Muircheartaigh, C. A., Schumm, L. P., and Cornwell, B. National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP): Wave 2 and Partner Data Collection. ICPSR34921-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2014-04-29. doi: 10.3886/ICPSR34921.v1). Those who were married at the time of W1 were asked: “You mentioned during our first interview that you were married to (name of W1 partner). Are you still married to (name of W1 partner)?” Those who in W1 reported living with a partner were asked: “You mentioned during our first interview that you were living with (name of W1 partner). Are you still living with (name of W1 partner)?” In both cases, if the respondent reported no longer being married to or living with the W1 partner, he or she was asked a series of questions about how the relationship ended (widowhood or divorce in the first case and separation or death in the second). Those who in W1 reported a nonresidential romantic, intimate, or sexual partner were asked: “You mentioned during our first interview in that you were in a romantic, intimate, or sexual relationship with (name of W1 partner). Are you still in a romantic, intimate, or sexual relationship with (name of W1 partner)?” These respondents were asked if they had married their partner or were living with him or her, or if the partner had died. The respondents provided the month and year for all the events and transitions. All respondents who were married or living with someone at W1, but no longer doing so in W2, were asked if they were still in a romantic, intimate, or sexual relationship with that person.

If the respondent reported his or her current status as something other than “married” or “living with a partner,” then the next question was: “do you currently have a romantic, intimate, or sexual partner?” Thus, any current partner was identified and the relationship characterized as spouse, cohabiting partner, or noncohabiting partner.

The second wave of NSHAP reinterviewed a nationally representative sample of older adults born between 1920 and 1947, who were between ages 62 and 91 at the time of the W2 interview (n = 2,422) and, when possible, their spouse or cohabiting partner interviewed regardless of NSHAP age eligibility (n = 955). Of the total sample (N = 3,377), 73.7% (n = 2,487) had a spouse or romantic partner (“all partnered”). Among 2,487 respondents, 2,260 are in marital cohabiting relationship, six are in marital part-time cohabiting relationship, 93 are in nonmarital cohabiting relationship, and 128 in nonmarital noncohabiting relationships. We replicated all of our results including/excluding nonmarital relationships (including nonmarital cohabiting relationships), but Cronbach’s alphas and factor structures for the scales did not show huge differences (e.g., differences in 2 scores are in the thousandth). Therefore, “all partnered” includes all of these four categories above. Of the all partnered sample (n = 2,487), both partners in 955 married or cohabiting couples were interviewed when possible (n = 1,910) (see Jaszczak et al., 2014). We define as dyads the couples in which both partners completed interviews (“all dyads”). It should be noted that 5 respondents identified their marital status as “married” while their partner reported being either widowed, separated, or divorced and was no longer living in the same household. These cases were possible because NSHAP interviewed the main respondent first and in some cases a long time (e.g., 6 months) elapsed before the partner was interviewed. We excluded these 5 couples (or 10 cases) in the present analysis, resulting 950 dyads (n = 1,900). Among these dyads, 95.9% (n = 1,822) are married dyads and 4.1% (n = 78) are cohabiting dyads.

Measures

NSHAP includes questions on a wide variety of social relationships, including marital and partner relationships, social networks (Cornwell et al., this issue), social support, sexual relationships, and social participation. We assess marital or cohabiting relationships in NSHAP using 13 indicators (Table 1). We draw on eight indicators identified in prior research as generally corresponding to the positive and the negative aspects of relationship quality (Bookwala & Franks, 2005; Fincham & Linfield, 1997; Warner & Kelley-Moore, 2012). We add five indicators of activities shared by couples. These items are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary Statistics for Indicators of Relationships Quality and Shared Activity in NSHAP.

| All Partnered (n = 2,487) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Husband (n = 1,307) | Wife (n = 1,180) | ||||||||||

| Mean | SD | n | Meana | SD | n | Meana | SD | n | |||

| Relationships quality | |||||||||||

| 1 | How would you describe your (marriage/relationship) with [current/recent partner]? (range from 1 = very unhappy to 7 = very happy) | 6.33 | 1.29 | 2,479 | 6.44 | 1.21 | 1,302 | 6.24*** | 1.36 | 1,177 | |

| 2 | In general, how often do you think that things between you and your partner are going well? (range from 1 = never to 6 = all the time) | 5.01 | 0.89 | 2,027 | 5.08 | 0.91 | 1,056 | 4.94*** | 0.98 | 971 | |

| 3 | How close do you feel is your relationships with [NAME]? (1 = "not very close," 2 = "somewhat close," 3 = "very close," and 4 = "extremely close") | 3.59 | 0.62 | 2,484 | 3.60 | 0.04 | 1,304 | 3.57 | 0.02 | 1,180 | |

| How often can you … (0 = "never," 1 = "hardly ever or rarely," 2 = "some of the time," and 4 = "often") | |||||||||||

| 4 | Open up to your spouse or partner? | 2.68 | 0.62 | 2,482 | 2.69 | 0.61 | 1,302 | 2.67 | 0.62 | 1,180 | |

| 5 | Rely on your spouse or partner? | 2.82 | 0.52 | 2,483 | 2.86 | 0.45 | 1,304 | 2.77*** | 0.58 | 1,179 | |

| How often does spouse or partner … (0 = never, 1 = hardly ever or rarely, 2 = some of the time, and 3 = often) | |||||||||||

| 6 | Make too many demands on you? | 1.15 | 0.97 | 2,482 | 1.23 | 0.94 | 1,304 | 1.05*** | 0.99 | 1,178 | |

| 7 | Criticize you? | 1.25 | 0.91 | 2,480 | 1.40 | 0.86 | 1,301 | 1.08*** | 0.93 | 1,179 | |

| 8 | Get on your nerves? | 1.42 | 0.76 | 2,016 | 1.34 | 0.76 | 1,049 | 1.52*** | 0.79 | 967 | |

| Shared activity | |||||||||||

| 9 | Some couples like to spend their free time doing things together, whereas others like to do different things in their free time. Do you like to spend free time doing things together, or doing things separately? (1 = different/separate things, 2 = some together, some different, and 3 = together) | 2.34 | 0.69 | 2,480 | 2.37 | 0.66 | 1,303 | 2.31 | 0.71 | 1,177 | |

| 10 | How often have you and your partner shared caring touch, such as a hug, sitting or lying cuddled up, a neck rub or holding hands? (from 1 = never to 7 = many times a day) | 4.66 | 1.76 | 1,995 | 4.64 | 1.67 | 1,041 | 4.69 | 1.85 | 954 | |

| 11 | In the last month, how often did you sleep in the same bed with your spouse or romantic partner? (from 1 = never to 6 = all the time) | 4.09 | 1.53 | 1,946 | 4.08 | 1.54 | 1,020 | 4.11 | 1.52 | 926 | |

| 12 | During the last 12 month, about how often did you have sex with current spouse or partner? (1 = none at all, 2 = once a month or less, 3 = 2–3 times a month, 4 = once or twice a week, 5 = 3–6 times a week, 6 = once a day or more) | 2.29 | 1.29 | 2,252 | 2.35 | 1.28 | 1,176 | 2.22 | 1.31 | 1,076 | |

| 13 | When your partner wants to have sex with you, how often do you agree? (from 1 = never to 5 = always, 0 = if volunteered: my partner has not wanted to have sex with me in the past 12 months) | 4.49 | 2.04 | 2,316 | 4.67 | 2.05 | 1,208 | 4.29*** | 2.02 | 1,108 | |

| All dyads (n = 1,900) | |||||||||||

| Husband | Wife | ||||||||||

| Meana | SD | n | Meana | SD | n | Meana | SD | n | |||

| Relationships quality | |||||||||||

| 1 | How would you describe your (marriage/relationship) with [current/recent partner]? (range from 1 = very unhappy to 7 = very happy) | 6.35 | 1.33 | 1,896 | 6.45 | 1.25 | 948 | 6.24*** | 1.39 | 948 | |

| 2 | In general, how often do you think that things between you and your partner are going well? (range from 1 = never to 6 = all the time) | 5.01 | 0.96 | 1,645 | 5.08 | 0.91 | 827 | 4.94*** | 0.98 | 818 | |

| 3 | How close do you feel is your relationships with [NAME]? (1 = not very close, 2 = somewhat close, 3 = very close, and 4 = extremely close) | 3.62 | 0.61 | 1,898 | 3.65 | 0.57 | 948 | 3.60 | 0.64 | 950 | |

| How often can you… (0 = never, 1 = hardly ever or rarely, 2 = some of the time, and 4= often) | |||||||||||

| 4 | Open up to your spouse or partner? | 2.70 | 0.61 | 1,897 | 2.70 | 0.63 | 947 | 2.69 | 0.6 | 950 | |

| 5 | Rely on your spouse or partner? | 2.86 | 0.44 | 1,898 | 2.91 | 0.35 | 948 | 2.81*** | 0.51 | 950 | |

| How often does spouse or partner … (0 = never, 1 = hardly ever or rarely, 2 = some of the time, and 3 = often) | |||||||||||

| 6 | Make too many demands on you? | 1.17 | 0.98 | 1,896 | 1.24 | 0.95 | 947 | 1.11* | 1 | 949 | |

| 7 | Criticize you? | 1.31 | 0.94 | 1,895 | 1.46 | 0.89 | 946 | 1.15*** | 0.95 | 949 | |

| 8 | Get on your nerves? | 1.43 | 0.78 | 1,636 | 1.34 | 0.76 | 820 | 1.52 | 0.79 | 816 | |

| Shared activity | |||||||||||

| 9 | Some couples like to spend their free time doing things together, whereas others like to do different things in their free time. Do you like to spend free time doing things together, or doing things separately? (1 = different/separate things, 2 = some together, some different, and 3 = together) | 2.35 | 0.70 | 1,897 | 2.39 | 0.68 | 949 | 2.32 | 0.72 | 948 | |

| 10 | How often have you and your partner shared caring touch, such as a hug, sitting or lying cuddled up, a neck rub or holding hands? (from 1 = never to 7 = many times a day) | 4.71 | 1.87 | 1,627 | 4.68 | 1.81 | 820 | 4.75 | 1.92 | 807 | |

| 11 | In the last month, how often did you sleep in the same bed with your spouse or romantic partner? (from 1 = never to 6 = all the time) | 4.12 | 1.56 | 1,587 | 4.13 | 1.56 | 806 | 4.11 | 1.56 | 781 | |

| 12 | During the last 12 months, about how often did you have sex with current spouse or partner? (1 = none at all, 2 = once a month or less, 3 = 2–3 times a month, 4 = once or twice a week, 5 = 3–6 times a week, and 6 = once a day or more) | 2.27 | 1.35 | 1,725 | 2.29 | 1.33 | 851 | 2.24 | 1.37 | 874 | |

| 13 | When your partner wants to have sex with you, how often do you agree? (from 1 = never to 5 = always, 0 = if volunteered: my partner has not wanted to have sex with me in the past 12 months) | 4.52 | 2.10 | 1,770 | 4.67 | 2.17 | 873 | 4.38** | 2.01 | 897 | |

Notes. aSurvey-adjusted and weighted to account for the probability of selection, with poststratification adjustments for nonresponse.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001 (Wald tests using design-based SE).

Relationship Quality

Questions regarding the quality of marital, cohabitational, and romantic partnerships in the in-person interview were preceded by the following statement: “For this next set of questions I would like you to think about your relationship with (current partner).” Item 1 in Table 1 asks: “Taking all things together, how would you describe your (marriage/relationship) with (current/recent partner) on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 being very unhappy and 7 being very happy?” In the Leave-Behind (LB) Questionnaire, respondents were asked (Item 2): “In general, how often do you think that things between you and your partner are going well? All the time, most of the time, more often than not, occasionally, rarely, or never?” Note that this question was new in W2. Emotional closeness (Item 3) to spouse or partner comes from the social network roster, which asks how close the respondent feels his/her relationship with each network alter to be. It ranges from 1 = not very close to 4 = extremely close. We included this item as an indicator of relationship quality if the identified network member corresponds to a spouse/partner. For detailed information on the network roster and roster for spouse (roster B), refer to Cornwell, Schumm, Laumann, and Graber (2009) and Cornwell and coworkers (this issue). A series of questions about support and demands from spouse/partner asks (Items 4–8) “How often can you open up to (current partner) if you need to talk about your worries? Would you say never, hardly ever or rarely, some of the time, or often?” The following questions had the same format and offered the same response categories: “How often can you rely on (current partner) if you have a problem?” “How often does (current partner) make too many demands on you?” “How often does (current partner) criticize you?” The LB Questionnaire included the following questions (Item 8): “How often does your partner get on your nerves?” with the response categories above. This question is new in W2.

Shared Activities

Following the prompt above to think about their relationship with their current partner, those with a partner were asked (Item 9): “Some couples like to spend their free time doing things together, while others like to do different things in their free time. What about you and (current partner)? Do you like to spend free time doing things together, or doing things separately?” In the LB Questionnaire, those with partners were asked how often in the last 12 months they had engaged in the following activities (Item 10): “How often have you and your partner shared caring touch, such as a hug, sitting or lying cuddled up, a neck rub or holding hands? Many times a day, a few times a day, about once a day, several times a week, about once a week, about once a month or less, or never?” “In the last month, how often did you sleep in the same bed with your spouse or partner? All the time, most of the time, some of the time, rarely, or never?” (Item 11).

One of the foci of NSHAP is sexuality, including sexual behavior. In the in-person interview, those with a current or recent partner were asked (Item 12): During the last 12 months (IF NOT CURRENT PARTNER: During your relationship), about how often did you have sex with (current/recent partner)? Was it once a day or more, 3–6 times a week, once or twice a week, 2–3 times a month, once a month or less, or none at all.” They were also asked (Item 13): “When your partner wants to have sex with you, how often do you agree? Always, usually, sometimes, rarely, or never?” If the respondent volunteered that his or her partner had not wanted to have sex with him or her in the past 12 months, this answer was recorded.

To construct scales of relationship quality and shared activity, we began by selecting indicators for each scale based on previous research on positive and negative marital quality and the shared activity of social relationships. Items were selected based on the correlation between each item and the rest of items included in the scale. Scales were constructed based on the internal consistency of the scale measure using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Then each scale was constructed by standardizing each items (M = 0 and SD = 1) and dividing the sum of standardized item scores by the total number of nonmissing items. This method allows calculating scale scores if at least one item has a valid response. This method allows maximizing the number of cases, retaining all cases for “all partnered” (n =2,487) and “all dyads” (n = 1,900). We conducted a sensitivity analysis comparing the complete cases (listwise deletion), all of the available cases, and the imputed cases, but the results show no differences. Missing cases were mainly due to the items in the LB Questionnaire (e.g., Items 2, 8, 10, and 11 in Table 1). The complete cases out of “all partnered” (n =2,487) is 1,982 for relationships quality, and 1,721 for shared activity. We used multiple imputations via the Stata 11.2 ice command for predicting missing values in the items using age, gender, race, and ethnicity and the other items in the scale. Five data sets were imputed. Then, we conducted sensitivity analysis comparing the mean scale scores across age and gender among the complete cases, all of the available cases, and the imputed cases (coefficients and standard errors from 5 data sets were adjusted for the variability between imputations according to Rubin’s rule). None of the results was significantly different (the t tests). We conducted exploratory factor analysis using the principal component factor method to explore the structure of the items separately for relationship quality (Items 1–8) and shared activity (Items 9–13). We compared the distribution of each scale by age group and gender.

Results

Distribution of Measures

Table 1 shows the distribution of the indicators of relationship quality and shared activity. It presents the mean, standard deviation, number of observations for each measure, and Wald-test results for gender differences. The top panel of Table 1 presents values for all partnered respondents (Columns 1–3), male-partnered respondents (Columns 4–6), and all female-partnered respondents (Columns 7–9). The bottom panel follows the same format but includes only those partnered respondents whose spouse or cohabiting partner also completed the interview (all dyads), in Columns 1–3 for both sexes combined, and in Columns 4–6 for males and in Columns 7–9 for females. Note that Table 1 presents means with all measures treated as linear although responses are ordinal. For some measures, the assumption of linearity in response categories is reasonable and for others less so. And for some analytic purposes, measures might be dichotomized. Analysts might choose to group categories of, say, shared activity into 2 rather than 3 categories or to distinguish those who say they never agree to sex to all others. Table 1 shows that husbands generally rated their relationships as happier than did wives (6.44 vs. 6.24 in all partnered, 6.45 vs. 6.24 in dyads on a scale of 1 [very unhappy] to 7 [very happy]) and said they thought things were going well more often than women did (5.08 vs. 4.94 on a scale of 1 [never] to 6 [all the time]). Men were more likely to say that they can rely on their spouse/partner when they have a problem than were women (2.86 vs. 2.77 in all partnered, 2.91 vs. 2.81 in dyads on a scale of 0 [never] to 4 [often]). However, husbands and male partners also were more likely to report negative features of their relationships; men more often said that their spouse/partner makes too many demands on them (1.23 vs. 1.05 in all partnered, 1.24 vs. 1.11 in dyads on the 0–4 scale above) and more often agreed that their spouse criticizes them (1.40 vs. 1.08 in all partnered, 1.46 vs. 1.15 in all dyads). Women said that their husbands get on their nerves (1.52 vs. 1.34 in both all partnered and all dyads) more often than men said their wives get on theirs. Note that only one of the measures of shared activities differs between husbands and wives in dyads: men reported more often that when their partner wanted to have sex, they agreed, in comparison with wives who said that they acquiesced when their husbands wanted to have sex (4.67 vs. 4.29 in all partnered, 4.67 vs. 4.38 in all dyads on a scale of 1 [never] to 5 [always]), although both genders said they almost always agreed. This supports Hakim’s (2010) argument that men generally desire sex more often than women do.

Relationship Quality Scale

To construct a scale of relationship quality, we considered eight indicators of this. Consistent with previous studies on marital quality, we proposed that these eight indicators reflect two dimensions of relationships quality: positive and negative (Bookwala & Franks, 2005; Fincham & Linfield, 1997; Warner & Kelley-Moore, 2012). Five of eight items were drawn from the respondent’s report on social support received from the spouse/partner (Items 4 and 5) and strains from the spouse/partner (Items 6–8). The items were modeled on the format used by an experimental module in the 2002 Health and Retirement Study to assess supportive (positive) and costly (negative) dimensions of relationships. Thus, the items explicitly instructed respondents to evaluate each dimension (either positive or negative) independently. We also included indicators for the quality of the relationship (Items 1–3): happiness, assessment of how well the relationship is going, and emotional closeness.

We initially considered including three additional measures regarding one’s current spouse/partner: feeling threatened or frightened by a spouse/partner, experiencing physical pleasure, and having emotional satisfaction with current spouse/partner (“How often have you felt threatened or frightened by your partner?” Two questions on relationship quality were included following these directions to the interviewer: “Ask this section if the respondent has current partner. If R does not have a current partner, ask the section in regards to most recent partner. A recent partner is defined as a partnership that occurred in the past 5 years.” “How physically pleasurable did/do you find your relationship with (current/recent partner) to be?” “How emotionally satisfying did/do you find your relationship with (him/her) to be? Extremely satisfying, very satisfying, very satisfying, moderately satisfying, slightly satisfying, or not at all satisfying?”). We expected that feeling threatened or frightened would indicate negative experiences in relationships. However, this item had a low item-rest correlation with other three items for negative dimensions of relationships (.27) and its removal increased the scale’s overall internal consistency (negative relationships quality [NRQ] from .63 to .66). We also examined whether an assessment of physical pleasure and emotional satisfaction with current spouse/partner captured relationship quality in the same way as the other items. These two indicators were drawn from the questionnaire on sex and partnership. Both indicators increased the scale’s overall internal consistency (physical pleasure: item-rest correlation = .45, α = .77; emotional satisfaction: item-rest correlation = .57, α = .76; overall scale α = .79). However, exploratory factor analysis including these two indicators generated a three-factor solution that could be interpreted as an assessment of sexual relationships in addition to positive and negative experiences. This suggests that an assessment of marital quality is conceptually distinct from an assessment of the sexual relationship. We therefore removed these three indicators from the scale.

Scale reliability and factor analysis.

Results from the exploratory factor analysis indicated that eight items loaded on two factors (only two factors had eigenvalues >1.0). For the all partnered cases, the first factor accounted for 37% of the variance (eigenvalue = 2.94) and the second factor accounted for 15% (eigenvalue = 1.21). For dyads, the first factor accounted for 36% of the variance (eigenvalue = 2.91) and the second factor accounted for 15% (eigenvalue = 1.19). Five items expected to assess positive dimension of relationships quality loaded heavily on one factor (all partnered, α = .72; dyads, α = .69) and three items expected to assess negative dimension of quality loaded heavily on the second factor (all partnered, α =.66; dyads, α =.65). The correlation between positive dimension and negative dimension was −.36 for the all partnered sample and −.41 for dyads.

Shared (Marital) Activity

We initially proposed that a measure of shared activities with a spouse/partner in NSHAP could be assessed using seven indicators. The internal consistency of the scale was maximized by removing two items: the frequency of talking with the spouse/partner and the frequency of making an effort to look attractive to the spouse/partner. We initially included the frequency of talking with a spouse/partner drawn from social network roster. However, the item-rest correlation was too low (.04) and removal of the items increased the internal consistency (from .53 to .60). About 97.3% of all respondent who identified their spouse as a member of their network spoke every day with their spouse/partner, and 99.1% of all dyads spokes every day with their spouse, so that differences in contact could not be used as a measure of shared activity. We also examined the possibility of including the frequency of making an effort to look attractive to his or her spouse/partner. We drop this item because the item-rest correlation was low (.23) and the addition of this item did not improve the scale’s overall internal consistency (.601 vs. .604). A factor analysis also confirms that adding this item resulted in a 2-factor solution with the second factor consisting of only this item. This suggests that making an effort to look oneself attractive to a spouse/partner is conceptually distinct from sharing activities. The final scale retained five items capturing one overall factor.

The first three items of the shared activity scale (Items 9–11 in Table 1) assessed the general preference for spending free time doing things with one’s spouse or for doing things separately; the frequency of sharing touching such as a hug, sitting or lying cuddled up, a neck rub or holding hands; and the frequency with which respondents and their spouse/partner slept in the same bed in the last month. The fourth and fifth item of shared activity (Items 12 and 13) asked about the frequency of having sex with one’s current spouse/partner and the frequency of agreeing with their spouse/partner when their partner wants to have sex. Responses to these five items were recoded if necessary so that higher scores on each item reflected more shared activities.

Scale reliability and factor analysis.

The shared activity scale had a Cronbach’s α of .61. The shared activity scale had acceptable reliability across gender and age groups for both all partnered cases and dyads (Cronbach’s αs between .60 and .64). Exploratory factor analysis confirmed that all five items load on one factor (eigenvalue = 1.97) accounting for 40% of the variance. Exploratory factor analysis indicated a 2-factor structure with an eigenvalue of the second factor slightly exceeding 1.0 (eigenvalue = 1.04 for all partnered, 1.02 for dyads). However, only 2 items (Item 12 and 13) loaded to the second factor and the first factor explained about 40% of the variance (for both all partnered and dyad cases). We decided to retain a 1-factor structure.

Distribution of Relationship Quality and Shared Activity Scale

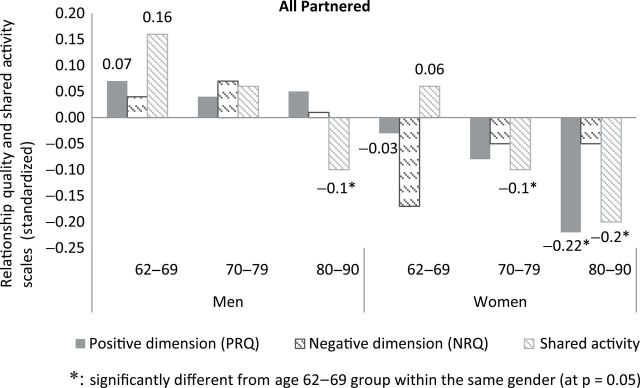

Previous studies on relationship quality suggested that high scores on both positive relationship quality (PRQ) and negative relationship quality (NRQ) indicated ambivalent feelings toward the spouse or partner (Fincham & Linfield, 1997). Table 2 showed that husbands and male cohabitors scored higher on both PRQ and NRQ than do wives and cohabiting women. They also scored higher on both PRQ and NRQ than the mean score of the all partnered (PRQ = 0.003, NRQ = −0.02) or of the all dyads (PRQ = 0.02, NRQ = 0.01). This suggested that a greater share of older men experience ambivalent feelings toward their spouse or partner than do women. Women reported significantly lower scores than men, on average, on both PRQ and NRQ and lower than the mean of the all partnered or the mean of the all dyads, which suggested that at least on the dimensions of the relationship measured here, more women than men have relationships of indifferent quality, with relatively low costs and relatively low benefits. Furthermore, gender differences in the positive dimension were consistent regardless of age groups. Even the youngest age group (62–69) showed marginal difference between men and women (all partnered: F = 3.98, p = .051; all dyads: F = 3.24, p = .078). Although our results showed no difference in age group (the PRQ score of the oldest age group of all partnered respondents was marginally lower), the trends of coefficients showed that women’s PRQ scores declined and NRQ scores increased with age, whereas men’s PRQ and NRQ scores fluctuated with age; older women had worse relationships than younger women, and older men in the middle age group (70–79) had worse relationships than younger or older men.

Table 2.

Mean and Standard Deviation for Relationship Quality and Shared Activity Scale, by Age Groups and Gendera

| All partnered | All dyads | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Husband | Wife | Husband | Wife | |||||

| M a | SD | M a | SD | M a | SD | M a | SD | |

| Relationship quality | ||||||||

| Positive dimension (all partnered, α = .72; dyads, α = .76) | ||||||||

| Overall | 0.06 | 0.67 | −0.07** | 0.81 | 0.07 | 0.64 | −0.05** | 0.77 |

| Age groupb | ||||||||

| 62–69 | 0.07 | 0.59 | −0.03 | 0.74 | 0.09 | 0.55 | −0.01 | 0.72 |

| 70–79 | 0.04 | 0.74 | −0.08* | 0.83 | 0.06 | 0.66 | −0.09** | 0.78 |

| 80–90 | 0.05 | 0.77 | −0.22** | 1.06 | 0.09 | 0.72 | −0.14** | 0.85 |

| Negative dimension (all partnered, α =.66; dyads, α =.65) | ||||||||

| Overall | 0.05 | 0.78 | −0.12** | 0.86 | 0.07 | 0.80 | −0.06* | 0.88 |

| Age groupb | ||||||||

| 62–69 | 0.04 | 0.69 | −0.17** | 0.79 | 0.03 | 0.69 | −0.10* | 0.82 |

| 70–79 | 0.07 | 0.85 | −0.05 | 0.93 | 0.12 | 0.86 | −0.02 | 0.93 |

| 80–90 | 0.01 | 0.91 | −0.05 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.03 | 0.94 |

| Shared activity (all partnered, α =.66; dyads, α =.65) | ||||||||

| Overall | 0.08 | 0.64 | −0.02** | 0.67 | 0.08 | 0.66 | −0.01** | 0.68 |

| Age groupb | ||||||||

| 62–69 | 0.16 | 0.56 | 0.06 | 0.60 | 0.17 | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.63 |

| 70–79 | 0.06 | 0.69 | −0.10*,c | 0.74 | 0.04c | 0.71 | −0.12**,c | 0.73 |

| 80–90 | −0.10c | 0.75 | −0.20**,c | 0.72 | −0.09c | 0.78 | −0.10c | 0.73 |

Note. aSurvey-adjusted and weighted to account for the probability of selection, with poststratification adjustments for nonresponse.

bA total of 126 women and 11 men were aged 61 and younger, and 4 men were aged 91 and older. These cases were excluded in age group comparisons.

cSignificantly different from the group aged 62–69 years (p < .01).

Significant difference between men and women: *p < .05, **p < .01.

On the shared activity scale, women had significantly lower scores than men, as shown in Table 2. This was unexpected as the shared activity scale is a measure of joint activities that cannot be achieved without both partners. We speculated that these differences might be specific to sexual activity (Items 12 and 13 in Table 1) rather than general activities (Item 9 and 10), because partnered sexual activity overall tends to be lower for older adults (Lindau et al., 2007). This gender difference in sexual activity was due, in part, to the fact that men tend to agree more often than women when their partner wants to have sex (Item 13 in Table 1) and to the fact that men tend to have younger spouses, whereas women tend to have correspondingly older spouses. In a supplementary analysis, we divided shared activity scale into general activities and sexual activities and tested age and gender differences. As expected, there were no significant difference in general activities between men and women or among age groups, but the frequency of sexual activity was significantly higher for the youngest age group than for the two older age groups. There were no significant gender differences in sexual activity among the oldest old. In addition, the trends of coefficients showed that both men and women tend to share fewer activities as they get older, again reflecting age differences in frequency of sexual activity. Figure 1 showed the average relationships quality and shared activity scales of all partnered men and women by age groups from Table 2.

Figure 1.

Relationships quality and shared activity by age groups and gender. *Significantly different from the group aged 62–69 within the same gender (at p = .05).

The positive dimension of quality was positively correlated with shared activity (r = .39, p < .000), whereas negative dimension of quality was negatively correlated (r = −.23, p < .000). This suggests that couples who often did things together were more likely to feel close, to be happy, to be able to open up to their spouse about worries, to be able to rely on their spouse if they had a serious problems, and to evaluate their relationships as going well. Those who shared fewer activities with their spouse were more likely to report that the spouse was demanding, got on their nerves, and/or criticized them, which was, perhaps, why they shared few activities. However, the evaluative Relationship Quality Scale was empirically and conceptually distinct from the more objective Shared Activities Scale. We conducted exploratory factor analysis on all of the relationships items in Table 1 to examine whether the shared activity items (9–13) and the positive quality items (1–5) loaded on one factor (Johnson et al., 1986). The result indicated a three-factor structure loading the positive quality items (1–5) to the first, the negative quality items (6–8) to the second, and the shared activity items (9–13) to the third factor.

Discussion

The second wave of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging survey provides rich and detailed information on a key dimension of social life, the married or cohabitational couple and those in such relationships. One important feature of the second wave of NSHAP is the addition to the sample of many of the spouses or cohabiting partners of W1 respondents, which generates data on 1,900 members of 950 dyads in which both people completed the entire W2 interview.

In this paper, we discussed measures of relationship characteristics and quality and presented a series of scales on relationship quality and shared activities that can be constructed from them. We note that two questions on relationship quality were new in W2, how often one’s spouse or partner gets on one’s nerves and how often the respondent feels that things with the partner are going well. However, these measures discussed here can be assessed separately for individuals, compared for members of dyads, examined for change between waves, and combined into scales. All these uses have benefits and costs. Analyses of relationship quality as assessed by individuals about their marriage or partnership have available large numbers of partnered individuals, almost 2,500 in W2. This sample may be used for analyses of the associations between health, life satisfaction, financial well-being, medical care, chronic diseases, emotional well-being, social networks, or many other characteristics of the lives of older adults. Many of these individuals were interviewed 5 years earlier in W1, so that relationship quality at the first wave can be used as a predictor of a later outcome, including later relationship quality, physical or mental health, morbidity, or mortality. For example, one could test the hypothesis that men whose wives had poor mental or physical health were less happy than others with their marriages, especially if their own health was poor, or especially if they shared few activities.

When using the shared activities scale as a predictor of some outcome such as health, given the estimated reliability of 0.61 for this scale, a regression model using this as a covariate will underestimate the true association between shared activities and the outcome. This problem could be addressed through errors-in-variables regression or structural equation modeling. More importantly, W2 data could be used to estimate the relationships between any of these scales and various health outcomes separately for men and women, with the paired sample provided additional power for detecting male/female differences. Another example would be determining whether the partner’s description of the relationship adds any additional predictive power, over the respondent’s description, in models, say, of health outcomes. This analysis could also be done in parallel for male and female respondents.

The availability of this second wave of data allows researchers to look at change over a 5-year period in relationships or to examine the effect of relationship characteristics at W1 on some later outcome. For example, one could test the hypothesis that those with higher quality relationships or more shared activities would be less likely to develop diabetes or some other chronic condition than those with poorer quality relationships or fewer shared activities, or that the unpartnered would do worse later in life than those with a partner, or that an individual’s welfare might depend on the characteristics of the partner or might differ by race or ethnicity.

We point out one feature of the data set that affects the possible uses of NSHAP data: the first wave, in 2005–06, included only one person per household, for reasons of cost. Those with a spouse or partner were asked detailed questions about that person but that person was not interviewed. In the second wave, most cohabiting spouses and romantic partners (but not roommates or others living in the household and not romantic partners living elsewhere) were eligible for inclusion in the sample. In advance of data collection, a small share of Wave 1 respondents were randomly selected to not have a partner interview generated for their cohabiting spouse or romantic partner, as part of an experiment to assess the effect of interviewing one’s spouse or partner on the answers to questions about sexuality and about the partnership. Thus, the W2 sample includes a sizable number of married or cohabiting men and women who were not interviewed in the first wave. For this reason, the W2 sample includes some individuals completing their second interview and some completing their first, and almost all those being interviewed for the first time are married or living with a W1 respondent, for whom we do have information from W1. Thus, the data set through W2 is not generally suitable for analyzing changes in dyads, although this will be possible when data from a third wave are added.

Key Points

This paper introduces scales on shared activity and relationship quality for married and partnered older adults.

NSHAP W2 provides detailed information about partnered men and women and their relationships, which can be assessed either for individuals or for dyads.

This yields 2,487 respondents with spouses or romantic partners and 1,900 members of 950 cohabiting dyads in which both partners were interviewed.

A focus on individuals provides information over time on the partnership as seen by that individual, available for a large number of people. A focus on dyads allows the comparison of men to their wives or partners and women to their husbands or partners. This gives a uniquely useful perspective on social life, health and aging.

Partnered men show both high PRQ and NRQ than do partnered women, suggesting that more older men than women experience ambivalent feelings toward their spouse or partner and more women than men have relationships of indifferent quality, with relatively low costs and relatively low benefits.

Funding

The National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project is supported by the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute on Aging (R37AG030481; R01AG033903), the Office of Women’s Health Research, the Office of AIDS Research, and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (R01AG021487), and by NORC which was responsible for the data collection.

Acknowledgments

J. Kim and L. J. Waite planned and conceptualized the study. J. Kim planned and conducted the statistical analysis, wrote the main text, and addressed the revision. L. J. Waite contributed to plan analyses and revising the paper.

References

- Bookwala J. (2011). Marital quality as a moderator of the effects of poor vision on quality of life among older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66B, 605–616. 10.1093/geronb/gbr091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J., Franks M. M. (2005). Moderating role of marital quality in older adults’ depressed affect: Beyond the main-effects model. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, P338–P341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury T. N., Frank D., Beach S. R. H. (2000). Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 964–980. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00964 [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell B., Schumm L. P., Laumann E.O., Kim J., Kim Y.-J. (2014). Assessment of social network change in a National Longitudinal Survey. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, S51–S63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell B., Schumm L. P., Laumann E. O., Graber J. (2009). Social networks in the NSHAP study: Rationale, measurement, and preliminary findings. Journal of Gerontology: Social Science, 64, i47–i55. 10.1093/geronb/gbp042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham F. D., Linfield K. J. (1997). A new look at marital quality: Can spouses feel positive and negative about their marriage? Journal of Family Psychology, 11, 489–502. 10.1037//0893-3200.11.4.489-502 [Google Scholar]

- Glenn N. D. (1990). Quantitative research on marital quality in the 1980s: A critical review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 818–831. 10.2307/353304 [Google Scholar]

- Gottman J. M., Coan J., Carrere S., Swanson C. (1998). Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 5–22. 10.2307/353438 [Google Scholar]

- Haines V. A., Beggs J. J., Hurlbert J. S. (2008). Contextualizing health outcomes: Do effects of network structure differ for women and men? Sex Roles, 59, 164–175. 10.1007/s11199-008-9441-3 [Google Scholar]

- Haines V. A., Hurlbert J. S. (1992). Network range and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33, 254–266. 10.2307/2137355 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakim C. (2010). Erotic capital. European Sociological Review, 26, 499–518. 10.1093/esr/jcq014 [Google Scholar]

- House J. S., Umberson D., Landis K. R. (1988). Structures and processes of social support. Annual Review of Sociology, 14, 293–318. [Google Scholar]

- Jaszczak A., O’Doherty K., Colicchia M., Satorius M., McPhillips J., Czaplewski M. … Smith S. (2014). Continuity and innovation in the data collection protocols of the second wave of the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, S4–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johnson D. R., White L. K., Edwards J. N., Booth A. (1986). Dimensions of marital quality: Toward methodological and conceptual refinement. Journal of Family Issues, 7, 31–49. 10.1177/019251386007001003 [Google Scholar]

- Kamp Dush C. M., Taylor M. G. (2012). Trajectories of marital conflict across the life course: Predictors and interactions with marital happiness trajectories. Journal of Family Issues, 33, 341–368. 10.1177/0192513X11409684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney B. R., Bradbury T. N. (1997). Neuroticism, marital interaction, and the trajectory of marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1075–1092. 10.1037/0022-3514.72.5.1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D. A., Kashy D. A. K., Cook W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. S., Waite L. J. (2010). How appreciated do wives feel for the housework they do? Social Science Quarterly, 91, 476–492. [Google Scholar]

- Lindau S. T., Schumm L. P., Laumann E. O., Levinson W., O’Muircheartaigh C. A., Waite L. J. (2007). A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 762–774. 10.1056/NEJMoa067423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D., Williams K., Powers D. A., Liu H., Needham B. (2006). You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite L. J., Gallagher M. (2001). Case for marriage: Why married people are happier, healthier and better off financially. Westminster, MD: Broadway Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein J. S., Blakeslee S. (1995). The good marriage: How and why love lasts. New York: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Warner D. F., Kelley-Moore J. (2012). The social context of disablement among older adults: Does marital quality matter for loneliness? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53, 50–66. 10.1177/0022146512439540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R. (2003). The health of men: Structured inequalities and opportunities. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 724–731. 10.2105/ajph.93.5.724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]