Abstract

Objectives.

Sensory function, a critical component of quality of life, generally declines with age and influences health, physical activity, and social function. Sensory measures collected in Wave 2 of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) survey focused on the personal impact of sensory function in the home environment and included: subjective assessment of vision, hearing, and touch, information on relevant home conditions and social sequelae as well as an improved objective assessment of odor detection.

Method.

Summary data were generated for each sensory category, stratified by age (62–90 years of age) and gender, with a focus on function in the home setting and the social consequences of sensory decrements in each modality.

Results.

Among both men and women, older age was associated with self-reported impairment of vision, hearing, and pleasantness of light touch. Compared with women, men reported significantly worse hearing and found light touch less appealing. There were no gender differences for vision. Overall, hearing loss seemed to have a greater impact on social function than did visual impairment.

Discussion.

Sensory function declines across age groups, with notable gender differences for hearing and light touch. Further analysis of sensory measures from NSHAP Wave 2 may provide important information on how sensory declines are related to health, social function, quality of life, morbidity, and mortality in this nationally representative sample of older adults.

Key Words: Aging, Demography, Geriatrics, Hearing, Older adults, Olfaction, Sensation, Sensory function, Social consequences, Vision.

Sensory function in older adults plays a critical role in health (Kiely, Gopinath, Mitchell, Luszcz, & Anstey, 2012), disease (Babizhayev, Deyev, & Yegorov, 2011; Lafreniere & Mann, 2009), and quality of life (Ciorba, Bianchini, Pelucchi, & Pastore, 2012; Lam et al., 2013; Viljanen et al., 2012). Though clinicians see the sequelae of both aging and disease on sensory function in their patients over time, these changes are typically gradual. Nonetheless, they impose important and heavy burdens for older people and may significantly affect public health, with consequences for a range of geriatric problems, from falls (Babizhayev et al., 2011) and injuries (Whiteside, Wallhagen, & Pettengill, 2006) to nutrition (Murphy, 1993). Importantly, compromise of sensory function is directly related to an older person’s ability to carry out routine daily activities (Hochberg et al., 2012) and to participate in important physiologic and social functions such as personal interaction (hearing and vision), nutrition (smell and taste), and mobility (vision, touch, and balance) (Albertsen, Temprado, & Berton, 2012). Major human functions such as sexuality, physical exercise, and intellectual stimulation are also affected. Thus, understanding the decline of sensory abilities is likely to help understand their role in social life, and, assuming they can be treated or mitigated, relieve these major burdens, thereby improving health and quality of life in older adults.

Although other studies have included sensory measures (e.g., the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES]), Wave 1 of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) focused exclusively on older adults with an emphasis on social function and in-home assessment of these modalities (Schumm et al., 2009). Analysis of the Wave 1 data improved our understanding of factors associated with decreased olfaction and taste (Boesveldt, Lindau, McClintock, Hummel, & Lundstrom, 2011) and vision (Bookwala, 2011; Bookwala & Lawson, 2011), along with information on health disparities in sensation (Pinto, Schumm, Wroblewski, Kern, & McClintock, 2014).

The purpose of NSHAP is to examine the effects of health burden on social function. With respect to sensory function, NSHAP focuses not only on objective measures, but also on subjective measures that help capture self-perception of impairment. In addition, NSHAP captures external ratings of function and the relevant characteristics of the home environment via interviewer ratings.

Ratings of sensory function can be a more broadly integrated assessment of a complex system than a single objective test targeted at only one component, for example, distance vision. Although cultural differences or personality (degree of stoicism) may skew these ratings, they also are referential to the respondent’s functioning when they were younger. By their nature, objective measures are restricted to the domains tested and do not necessarily reflect all perceived aspects of sensory loss, especially on an integrated framework of overall function in the real life environment of older adults. For example, clinically measured sensory function (e.g., distance vision using a Snellen chart under optimal high-contrast lighting) may not reflect conditions in the home (where lighting is often dimmer than in the clinic) and therefore underestimate the burden felt by older adults. Nor does it measure the impairment of near or peripheral vision, which may contribute to an overall sense of vision impairment. However, objective measures are by definition carefully defined and can be compared across studies; thus, objective and subjective measures provide different and complementary perspectives on sensory function in field research.

Representative data on longitudinal changes in sensory function are sparse. Other studies have included older adults (Lam et al., 2013) in addition to younger individuals (Kiely et al., 2012; Pedroso et al., 2012; Schubert, Cruickshanks, Klein, Klein, & Nondahl, 2011). Wave 2 of NSHAP provides an opportunity to study self-reported (and for olfaction objective) sensory decline with aging in an older cohort after a 5-year interval in a social context. Wave 2 is focused on respondents’ global self-assessments of their sensory experience and how those assessments are associated with their physical health, mental health, and social function in the home environment.

We summarize the available information on sensory measures in Wave 2 of NSHAP for potential researchers. We also provide an analysis comparing subjective and objective assessment of vision from Wave 1 as an example of the types of analyses possible in this data set. Our goals are to illustrate the differences in measures collected in Waves 1 and 2 and to describe the range of sensory measures included in Wave 2 in an effort to provide a roadmap toward utilizing this data set for research on sensory decline in older adults.

Method

Brief Description of the NSHAP Cohort

In 2005–2006 interviewers from the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) conducted in-home interviews with 3,005 community-dwelling older adults (1,454 men and 1,551 women), a representative sample of the U.S. community-dwelling population 57–85 years of age (NSHAP Wave 1) (O’Muircheartaigh, Eckman, & Smith, 2009; Suzman, 2009). Five years later, data were collected again (2010–2011, Wave 2) in the same respondents and their cohabiting partners, plus a few Wave 1 respondents who had refused the Wave 1 interview but completed Wave 2. Interviews collected demographic, social, psychological, and biological measures, including sensory function, which are detailed subsequently. Further details regarding design, data collection, and baseline characteristics of NSHAP respondents are available elsewhere (Lindau et al., 2007; O’Muircheartaigh et al., 2009; Suzman, 2009) [Jaszczak et al. and O’Doherty et al., in this special issue]. The Institutional Review Boards of The University of Chicago and NORC approved the study; all respondents provided written, informed consent.

Sensory Measures: Differences Between Waves 1 and 2

In constructing the sensory items in Wave 2, the NSHAP investigator team reviewed data generated from Wave 1 with a goal of streamlining the survey protocol. It was decided to remove the objective measures of gustation, vision, and touch due to time constraints to improve the objective measure of olfactory function (Kern et al., in this issue), and to focus in this wave on respondents’ perceptions of sensory losses and their social consequences. Gustation, vision, hearing, and touch may be (re)measured objectively in the next wave of data collection (Wave 3), potentially providing interval follow-up. Notably, interviewer ratings of vision and hearing were included in Wave 2 as external measures of the respondent’s sensory function during a social interaction (objective perspective) in addition to the respondent’s own rating (subjective perspective).

The same subjective questions from Wave 1 on vision and hearing were included in Wave 2, with some minor modifications (see Table 1). Overall vision and hearing were self-rated from “poor” to “excellent” as well as degree of specific difficulty driving during the day or night. Modified questions included the use of hearing aids (or not), a common treatment for sensorineural hearing loss (Laplante-Levesque, Hickson, & Worrall, 2010), and specific social consequences of difficulty with hearing (e.g., frustration with communication, difficulty hearing whispers, and compromise to personal or social life) (reviewed in Vesterager & Salomon, 1990). In Wave 2, perceived sensation of touch was measured by ranking the appeal or pleasantness of a light touch (not at all to very appealing), a stimulus associated both with allodynia and social interaction (see Galisky et al., in this issue). Because self-rated olfactory function does not correlate with objective measures (20), this question was dropped from the subjective items on olfaction, but assessment of factors that may influence assessment of olfactory function was enhanced in Wave 2 (e.g., presence of a cold, history of facial trauma, or nasal surgery; see Kern et al., in this issue).

Table 1.

A Summary of Subjective Sensory Function Measures Collected in NSHAP Waves 1 and 2. *Prompted in Wave 1— “If you wear a hearing aid, please answer this based on your hearing when you are wearing your hearing aid”

| Senses | Self-reported sensory measures | |

|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | |

| Olfaction | • “How is your sense of smell? Is it… EXCELLENT, VERY GOOD, GOOD, FAIR, POOR” Randomized subset (50%) • “Have you ever had surgery on your nose? YES, NO” Full sample |

• “Today, do you have a head cold or chest cold? YES, NO” • “Broken nose in the past 5 years? YES, NO” • “Have you ever had surgery on your nose? YES, NO” Full sample |

| Gustation | • “How is your sense of taste? Is it… EXCELLENT, VERY GOOD, GOOD, FAIR, POOR” Randomized subset (50%) |

• None |

| Vision | • “With your glasses or contact lenses if you wear them, is your eyesight EXCELLENT, VERY GOOD, GOOD, FAIR, OR POOR?” • “Driving a car during the day? NO DIFFICULTY, SOME DIFFICULTY, MUCH DIFFICULTY, UNABLE TO DO, HAVE NEVER DONE (if volunteered), DOES NOT DRIVE ANYMORE (if volunteered)” • “Driving a car during the night? NO DIFFICULTY, SOME DIFFICULTY, MUCH DIFFICULTY, UNABLE TO DO, HAVE NEVER DONE (if volunteered), DOES NOT DRIVE ANYMORE (if volunteered)” Full sample |

• “With your glasses or contact lenses if you wear them, is your eyesight” EXCELLENT, VERY GOOD, GOOD, FAIR, OR POOR? • “Driving a car during the day?” NO DIFFICULTY, SOME DIFFICULTY, MUCH DIFFICULTY, UNABLE TO DO, HAVE NEVER DONE (if volunteered) • “Driving a car during the night?” NO DIFFICULTY, SOME DIFFICULTY, MUCH DIFFICULTY, UNABLE TO DO, HAVE NEVER DONE (if volunteered) Full sample |

| Hearing | • “Have you ever had a severe head injury requiring hospitalization overnight? Do not include an overnight stay in the emergency room. YES, NO” • “How old were you when you had this injury?” • “Is your hearing EXCELLENT, VERY GOOD, GOOD, FAIR, OR POOR?”* • “Do you feel you have a hearing loss? YES, NO” Full sample |

• “Is your hearing, with a hearing aid if you wear one,” EXCELLENT, VERY GOOD, GOOD, FAIR, OR POOR? • “How often do you wear a hearing aid?” NEVER/DON’T HAVE ONE, SOMETIMES, MOST OF THE TIME, ALWAYS • “Does a hearing problem cause you to feel frustrated when talking to members of your family?” YES, NO • “Do you have difficulty hearing when someone speaks in a whisper?” YES, NO • “Does a hearing problem cause you difficulty when visiting friends, relatives, or neighbors?” YES, NO • “Do you feel that any difficulty with your hearing limits or hampers your personal or social life?” YES, NO Full sample |

| Touch | • “How is your sense of touch? Is it, EXCELLENT, VERY GOOD, GOOD, FAIR, POOR” Randomized subset (50%) |

• “Some people like being physically touched by people they are close to, whereas others do not. How appealing or pleasant do you find the following ways of being touched? 1. Being touched lightly, such as someone putting a hand on your arm? 2. Hugging? 3. Cuddling? 4. Sexual Touching? VERY APPEALING, SOMEWHAT APPEALING, NOT APPEALING, NOT AT ALL APPEALING” Full sample |

As in Wave 1, field interviewers in Wave 2 provided an external (albeit their own subjective) assessment of respondents’ vision and hearing as well as relevant characteristics of the home environment (Table 2). These measures included metrics of room lighting for vision, assessment of room noise for auditory function, and the odor of the respondent’s home (Table 2). A reference table of objective measures is provided in Table 3.

Table 2.

Field Interviewer Ratings of the Respondents’ Sensory Perception of the Environment in Waves 1 and 2 of NSHAP

| Sensory measure | Waves 1 and 2 field interviewer ratings |

|---|---|

| Olfaction | • Room smell intensity using a 5-point scale ranging from “NO SMELL” to “STRONG SMELL”• Room smell hedonics using a 5-point scale ranging from “PLEASANT SMELL” to “UNPLEASANT SMELL” Full sample |

| Gustation | • None |

| Vision | • Respondent vision using a 5-point scale ranging from “PRACTICALLY BLIND” to “NORMAL VISION”Room lighting using a 5-point scale ranging from “DARK” to “LIGHT” Full sample |

| Hearing | • Respondent hearing using a 5-point scale ranging from “PRACTICALLY DEAF” to “NORMAL HEARING”• Room sound using a 5-point scale ranging from “QUIET” to “NOISY” Full sample |

| Touch | • None |

Table 3.

Objective Evaluation of Sensory Function Collected in NSHAP Waves 1 and 2

| Senses | Objective sensory tests | |

|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | |

| Olfaction | • Olfactory Identification Test (Five-Item Sniffin’-Sticks Test) • Sensitivity: n-butanol Sniffin’-Sticks (with Visual Analog Scale (VAS)) Full sample |

• Olfactory Identification Test (Five-Item Sniffin’-Sticks Test) • Detection: n-butanol and androstadienone Sniffin’-Sticks triads Randomized subset (66%) |

| Gustation | • Four taste strips (sour, bitter, sweet, salty) • R’s were asked to rate their certainty of each response using a 10-point scale Full sample |

• None |

| Vision | • Binocular distance acuity at 3 m using a Sloan letters chart (with glasses if aided) Randomized subset (50%) |

• None |

| Hearing | • None | • None |

| Touch | • Two-point discrimination at the tip of the index finger on the dominant hand at 12mm, 8mm, and 4mm Randomized subset (50%) |

• None |

We performed linear regression to determine the effects of gender and age (62–69, 70–79, and 80–90 years of age, including two participants who were 91 as an artifact of interview scheduling) on self-rating of audition and vision. Similarly, we examined the effects of age group and gender on the 5-year change in self-rating of these two senses between Waves 1 and 2. We used ordinal logistic regression to assess the effects of gender and age on ratings of the appeal of being lightly touched. Correlations between Wave 1 and Wave 2 responses were assessed by the method of Spearman. For comparison of factors associated with subjective versus objective vision, multivariate ordinal logistic regression was employed to determine the effects of age, sex, race, education level, social, and health factors. A p value ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results/Analysis

Here we highlight the Wave 2 estimates of sensory decrements in the U.S. population, 62–90 years of age, and report differences between age groups and gender. The distributions for each sensory modality are available in the Supplementary Tables A–G.

Vision

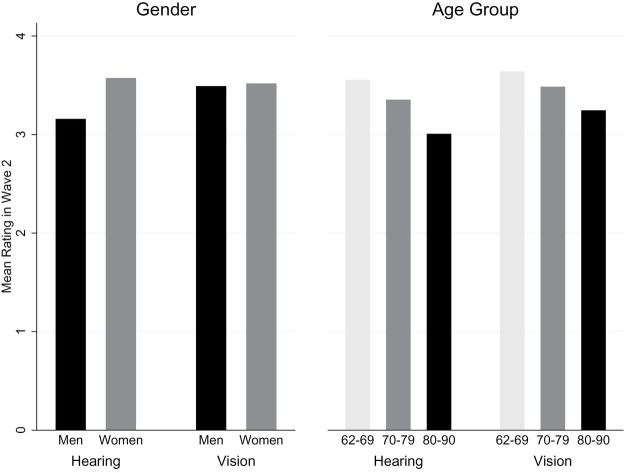

Sixteen percent of home-dwelling older adults rated their current vision as poor or fair (Supplementary Table A). Likewise, of all respondents, 14% reported some difficulty driving during the day, although 40% had difficulty at night; 8% were unable to drive during the day. Severity of impaired vision was greater in the middle and oldest age groups than the youngest age group (p = .001 and p < .001, respectively) but similar for men and women (p = .64; Figure 1). Comparable results were found using ordinal logistic regression. The same effects of age and gender were detected 5 years earlier in Wave 1 (data not shown here). Thus, preliminary analysis of Wave 2 data confirmed that vision impairment in community-dwelling older adults is prevalent in both men and women and increases across age groups.

Figure 1.

Effects of gender and age on self-rated hearing and vision. Y axis: Self-rated scores (1 = poor, 5 = excellent).

Among respondents assessed 5-years apart in Waves 1 and 2 (n = 2,254), the degree of impairment was significantly correlated (r = 0.40), indicating stable individual differences in visual function within the population. Of these respondents, approximately 40% reported no change in vision, 23.6% reported a decline of one functional category, 7.6% a decline of two functional categories, and only 1.4% a decline of three functional categories. Although the remaining 27% reported an improvement by at least one functional category, significantly more respondents showed a decline versus improvement (p < .001). These data suggest that a large number of older adults have stable vision, perhaps related to the healthier condition of NSHAP respondents who live at home compared with their counterparts who reside in nursing or retirement homes or hospitals. Nevertheless, ~30% of respondents reported declines in vision.

Men and women reported a similar decline in vision between Waves 1 and 2 (average drop ± SEM: 0.06±0.04 in men versus 0.11±0.04 in women, p = .21). This 5-year decline in vision was greater for the oldest and second oldest age groups compared with the youngest respondents (average drop: 0.19±0.05, 0.12±0.05, and 0.01±0.05, in the oldest, middle, and youngest age groups, respectively; p = .04). This is consistent with the cross-sectional analysis described earlier and may support the hypothesis that aging of the visual system does not appear to be affected by hormonal or other physiologic differences or by differential environmental exposures between genders.

Interviewers rated 55% of respondents as having normal vision (Supplementary Table B). However, only 23% of homes were rated as well lit, reflecting a major environmental challenge in the home that might compromise the function of the other 45% with decreased vision. Increasing light levels might be a simple way to mitigate poor vision.

Vision as an Example of Concordance Between Subjective Experience and Objective Assessment

Prevalence of Vision Impairment in Wave 1.

Of the 1,506 Wave 1 respondents randomized to receive the vision assessment, 93.9% (n = 1,414) completed the Sloan chart test for distance visual acuity and rated the quality of their vision overall. Reasons for exclusion included (n = 92): refusal to participate (n = 64), glasses were not worn (n = 20), incomplete interview or equipment problems (n = 5), and self-reported vision was not reported (n = 3).

Almost a quarter of older adults in Wave 1 (23%) had an objectively-measured vision impairment (defined as less than 20/40 best-corrected bilateral visual acuity, the minimum acuity required for obtaining a driver’s license). This included respondents who were unable to read the largest line on the chart and categorized as having worse than 20/200 vision (n = 23).

Similarly, 18% of respondents had self-reported vision impairment (poor or fair vs. good, very good, or excellent). Fully 75% of respondents were concordant for objective visual acuity and overall subjective assessment. Rooms rated as more brightly lit were associated with better objective (p < .001), but not subjective, vision.

Covariates of Subjectively and Objectively Assessed Vision in Wave 1.

Increased age, more medications, and more depressive symptoms were associated with decrements in both subjective and objective vision (Table 4; n = 1,377 respondents with relevant covariates and both subjective and objective vision). We also found that social, demographic, and health factors have different effects on objective and subjective vision, indicating that each may have an impact on perception of sensory function in the home environment. Interestingly, gender (women) and decreases in cognition were associated with worse objective visual acuity, but not self-reported subjective vision. In contrast, impaired subjective vision was more prevalent among non-whites, those with less education, and those with increased problems with activities of daily living, whereas decreased objectively-measured visual acuity was not. Additionally, brighter home lighting was strongly associated with better objective visual acuity.

Table 4.

Multivariate Ordinal Logistic Regression of Objectively Assessed and Subjectively Assessed Vision in NSHAP Wave 1

| Objective (n = 1,377) | Subjective (n = 1,377) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

| Age (year) | 0.93*** | 0.92, 0.95 | 0.98* | 0.97, 0.99 |

| Gender (Women vs. Men) | 0.77** | 0.64, 0.93 | 1.11 | 0.91, 1.35 |

| Race/ethnicity (vs. White) | ||||

| Black | 0.83 | 0.63, 1.10 | 0.57*** | 0.43, 0.76 |

| Hispanic | 0.99 | 0.70, 1.40 | 0.45*** | 0.32, 0.65 |

| Other | 1.46 | 0.79, 2.69 | 0.69 | 0.37, 1.27 |

| Education (vs. <High School) | ||||

| High School or equivalent | 1.17 | 0.88, 1.56 | 1.66*** | 1.23, 2.23 |

| Some college | 1.63*** | 1.22, 2.17 | 1.93*** | 1.43, 2.59 |

| ≥Bachelor’s | 1.24 | 0.91, 1.69 | 2.31*** | 1.67, 3.20 |

| Depression (vs. not depressed–CES-Da <9) |

0.75* | 0.59, 0.97 | 0.39*** | 0.30, 0.51 |

| Cognitionb | 1.23*** | 1.12, 1.35 | 1.04 | 0.95, 1.14 |

| Comorbidityc | 0.95 | 0.89, 1.01 | 1.01 | 0.94, 1.08 |

| Medicationsd | 0.97* | 0.94, 0.99 | 0.97* | 0.94, 0.99 |

| ADL probleme | 1.00 | 0.92, 1.08 | 0.85*** | 0.78, 0.92 |

| Brightness of room lightingf | 1.35*** | 1.22, 1.50 | 1.03 | 0.93, 1.15 |

Notes. Objectively assessed vision was categorized such that higher categories indicated better vision based on Sloan chart test performance. Subjectively assessed vision was rated on a 5-point scale from poor to excellent.

aCenter for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

bCognition based on performance on Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (range 0–10).

cModified Charlson comorbidity index (range 0–10).

dNumber of medications (range 0–20).

eNumber of Activities of Daily Living problems (range 0–6).

fInterviewer rated brightness of room lighting (range 1 = dark to 5 = light).

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Most respondents’ visual assessments were concordant (objective and subjective vision measures). Assessing factors that predict vision concordance would improve future survey studies of sensory function and provide insight into how older people view their sensory health. Indeed, Chen and colleagues employed Wave 1 data to examine concordance of objective vision assessment and self-report of vision to determine pessimism and optimism about this sensory function (Chen, McClintock, Kern, Pinto, & Dale, 2013).

Hearing

Among NSHAP respondents, 22% reported poor or fair corrected hearing (Table C; 13% used a hearing aid). Interestingly, although only 12% of respondents reported that hearing difficulties limited personal or social life, fully 42% had trouble hearing whispered words and a significant number experienced frustration when talking with family members (20%) or when visiting with friends, relatives, and neighbors (18%). These results support the fact that hearing loss is a major sensory burden in older adults, but hint that perception of this burden is context specific, affecting concrete problems of everyday living rather than broad concepts of burden in the mind of respondents.

Men reported more hearing loss than did women (p < .001; Figure 1). As with vision, hearing loss was more severe in the middle and oldest age groups compared with the youngest age group for both genders (p = .001, p < .001, respectively). Similar gender differences and age effects were found using data collected 5 years earlier in Wave 1 and by using ordinal logistic regression (data not shown here). Thus, hearing impairment in community-dwelling older adults is a frequent outcome and prevalence increases in older age groups. These gender differences in cross sectional analyses of self-reported hearing are consistent with well-known gender differences in age-related hearing loss. Hearing loss was also more severe in older respondents as is typical of this generation where work-related noise exposure (e.g., in factories, industrial settings) was much higher for men.

The correlation between self-reported auditory function in Wave 1 and Wave 2 was r = 0.57, higher than that found for vision. More respondents experienced a decline in best hearing (i.e., potentially corrected with hearing aids) rather than an improvement (n = 2,248, p < .001). A quarter (23%) reported a decline of one functional category, 5.1% a drop of two functional categories and only 0.89% a drop of three or four functional categories. Almost half (46%) did not report a change and the remaining 25% reported an improvement by at least one functional category. Age groups did not differ in magnitude of the decline (average drop ± SEM: 0.01±0.05, 0.11±0.04, and 0.05±0.06 in youngest, middle, and oldest age groups, respectively; p = .25). This may reflect that the aging of the auditory system may begin earlier in life, prior to the age of 57 years. Men and women had similar declines between Waves 1 and 2 (average drop of 0.07±0.04 for men and 0.04±0.04 for women, p = .66). Interestingly, this lack of a significant difference in hearing across waves between the genders may indicate that once the injury to auditory function has occurred, both groups decline at the same rate. We speculate that there may be a window of time earlier in life where people are most sensitive to this environmental insult. Indeed, noise exposure is a known risk factor for hearing loss, but its role in affecting hearing specifically in older adults is not well known nor is it known when in life the auditory system is most susceptible to injury. Hobbies such as gun use or prior history of gun use (e.g., in veterans) may affect hearing loss.

Those using hearing aids (either sometimes, most of the time, or always) nonetheless reported significantly lower corrected hearing function (2.78±0.08, n = 397) compared with those who did not (3.45±0.03, n = 2,978; p < .001). This is an important internal control, as hearing aid use would be expected to be associated with worse audition.

Interviewers rated 54% of respondents as having normal hearing, and a large majority of homes were rated as quiet during the interview (75%; Supplementary Table D).

Touch

A majority of respondents reported that being touched lightly was somewhat or very appealing/pleasant (87%; Supplementary Table E). Men found it less appealing than did women (p = .011; for example, 36% of men vs. 41% of women rated it very appealing). The appeal of light touch was lowest in the oldest age group (p < .001; for example, 41% (62–69), 40% (70–79), and 30% (80–90) considered it very appealing). These results indicate that there are gender differences in the perception of touch, a finding that may affect the relationships between partners including both sexual and non-sexual activity as well as interpersonal communication. Furthermore, such differences could have health implications on activities such as exercise, physical or occupational therapy, or delivery of social services. Further information on pleasure derived from light and intimate touch is provided in this issue (Galinsky et al., in this special issue). We note that this measure is different than traditional objective physiological measures of touch (e.g., as included in Wave 1 [two-point discrimination] or assessment of sensitivity to vibration or pressure; Bruce, 1980; Thornbury & Mistretta, 1981; Gescheider, Bolanowski, Hall, Hoffman, & Verrillo, 1994; Goble, Collins, Cholewiak, 1996; Verrillo, Bolanowski, & Gescheider, 2002).

Olfaction

On the day of the survey, few respondents reported having a cold (8%), which might have altered objective olfactory assessment (Supplementary Table F). There was also a low prevalence of a history of nasal surgery or of trauma (8% and <1%, respectively), other factors that affect olfaction. Thus, these potential confounds should not greatly affect estimates of objective olfactory function (reported by Kern et al., in this issue), although some researchers may wish to consider not including these respondents in certain analyses. In this way, relevant parameters present at the time of olfactory assessment can be used as internal controls in analyses, for example by comparing those with colds or surgery to those without.

Interviewers rated the strength and pleasantness of odors present in the home, which might affect olfactory function. Fully 76% of homes were rated as having no smell, whereas 3% had a strong odor (Supplementary Table G). Of homes with odors, 65% were rated somewhat unpleasant (a rating of 3–4 out of 5) and an additional 14% smelled the most unpleasant (5 on a 5-point scale; Supplementary Table G). Conversely, environmental odors in the home may reflect inability to detect malodors and also yield insights into other aspects of health (social disorganization, poor cognition, lack of social supports, etc.).

Discussion

These data provide nationally representative information on sensory function in older adults who live at home in the United States. Preliminary analysis revealed that vision and hearing impairments in these older adults are prevalent in both men and women and are greater in older age groups. We found expected gender differences in cross-sectional analysis of self-reported hearing, consistent with well-known gender differences in age-related hearing loss. These data demonstrate the kind of questions that can be addressed in NSHAP that can be used to complement and contrast with other major studies that contain information on sensory function (e.g., the National Health and Nutrition Examination, among others). We note that NSHAP’s sampling design (though similar to the Health and Retirement Study from which it is derived) is distinctive and its focus on social context and function remains a relative strength.

The sensory impairments shown here have important functional consequences in terms of personal interactions with both friends and family, but also on critical activities such as driving (Ramulu, West, Munoz, Jampel, & Friedman, 2009). For example, these deficits could affect access to health care, healthy foods, personal safety, with major impacts on health, quality of life, and social function. Inability to communicate (e.g., hearing other people or reading correspondence) could affect pleasure in daily life and lead to social isolation, with concomitant depression, anxiety, or stress. With the rich data available in NSHAP Wave 2, these questions can be directly addressed. For each modality, important questions of the relationship to disease, medication use, co-morbidity, and social function can be answered with this data set.

A number of types of additional analyses are possible with these data. Vision is the most straightforward as the subjective assessments of overall vision are exactly the same in Waves 1 and 2 and thus interval change with time can be addressed in the same individuals, or cohort effects can be assessed in analyses adjusted for birth year. Similarly, because self-rated hearing was measured in both waves, longitudinal analyses are possible here.

Distinction between subjective and objective evaluation of sensory function receives much attention in studies with a clinical perspective. However, for analysis of personal impact of sensory function on social functions, it is illustrative to consider which factors are associated with each assessment and how they differ. This is possible for vision, touch, olfaction, and gustation in Wave 1, where both objective and subjective measures were collected. Similarly, assessment of the home environment as provided by field interviewer rating of relevant parameters for these senses (as well as their ratings of subject sensory function) is available in both Wave 1 and Wave 2, allowing for analyses that account for home context, for example in our examination of vision concordance. Lastly, one might use subjective measures and/or field interviewer ratings to impute missing data.

Field interviewer ratings of respondent sensory function and the home environment can be incorporated into such analyses and enable users of this data set to assess if the self-reported information is consistent with the trained interviewer’s determination. We acknowledge the limitations of such ratings, but they can provide important information in studies of the social setting of older adults and their health. For example, ratings of the noise present in the home could be used as covariates when analyzing respondent hearing. Nevertheless, these ratings compromise a small subset of interviewer provided ratings across a large standard battery of items common in these types of surveys. As with all survey items, such data come with some degree of associated error. Interviewers (n = 124) were highly trained professionals with longstanding experience in survey studies, and the study was designed to increase inter-rater reliability across all measures. Lastly, we did not measure interviewer sensory function, though they were largely young and mostly women with likely normal sensory function allowing reasonable estimates for these ratings. We are not aware of assessments of interviewer sensory function in survey studies for use as a scale anchor or covariate in analyses; such assessment was not feasible in NSHAP.

The variables concerning subjective assessment of home environment and relevant history similarly provide useful context. For hearing and smell, the environmental information can be used as a check or control when analyzing other aspects of the data (self-report or objective function, respectively) and provide important contexts. For example, use of hearing aids is an indicator of worse hearing and respondents with colds may show worse olfaction.

Analyses of these data are limited by the granularity of available health information; for example, without detailed data on prior treatments, earlier life history, or environmental exposures on sensory function, such studies are not possible. Other limitations would include specific details related to the sensory measures. For example, we did not include assessment of near vision, presence of cataracts or history of cataract surgery, laterality of hearing, vision, or olfactory loss, nor variability in the assessment of touch at multiple anatomic sites. Objective measures are limited to interviewer observations without audiometry, which constrains conclusions that can be drawn regarding experienced and objective hearing loss. These limitations were necessary for logistical reasons related to survey length and cost (e.g., portable audiometers, need for trained technicians, etc.).

A potential limitation to the subjective measures is variation in temperament and standardization of self-rating scales. Though open to challenge, it is our opinion that inclusion of such measures provides for a more personal reflection of disease burden in the case of respondents and provides a more holistic assessment of health by allowing analysis of how respondents perceive their sensory function and contrast their actual level of function for measures where that is available. These data may also be used as an external check on perception of these burdens and environmental contexts in the case of interviewers. Our example of vision concordance supports this argument. However, we acknowledge that other confounders not measured in NSHAP could lead to reporting better or worse function via self-report than by objective measurement (e.g., known generational and cultural differences in stoicism, personality or psychological or religious proclivities). In this context, one may consider the subjective measures in Wave 2 as perceived sensory function. One critical finding in this study, which is generalizable to other studies of sensory function that employ NSHAP data, is that as assessments were made in the home, they reflect these perceived conditions in the home environment and thus are directly translational in terms of personal and societal impact, as has been suggested by others (Ball, 2003). In summary, despite these limitations, NSHAP provides an excellent opportunity to examine the relationship between sensory loss, aging, and health in a social context.

Most importantly, the relationship between sensory function and other health measures can be addressed using these data. For example, what is the association between sensory function and comorbidities, mental health, social networks? Does this vary by race, gender, age, or modality? Data from NSHAP show a substantial prevalence of olfactory loss in older adults and significant health disparities, with African Americans showing worse olfactory function compared with whites despite adjustment for relevant confounders (Pinto et al., 2014) (see also Kern et al., in this issue). Are some senses more “frail” than others? Is there a concept of sensory frailty that incorporates these measures? In summary, a host of studies are possible with these data that will inform the factors that affect sensory loss and also consequences that these losses have on health and social function.

Key Points .

Sensory measures collected in Wave 2 of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) included information on olfaction, vision, hearing, and touch.

Significant differences between men and women existed for hearing and touch, and age was associated with decreased sensory function across modalities.

These deficits were associated with detrimental impact on social function.

These data, along with associated measures related to social and physical function and health may prove useful for the investigation of sensory function in older people.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material can be found at: http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

NSHAP was funded by the National Institute on Aging (grant numbers AG033903-01, AG030481-37, AG021487-01), and by NORC which was responsible for the data collection. These awards also supported the work of KEW, LPS, DWK, and MKM. DWK was also supported by The Center on Aging Specialized Training Program in the Demography and Economics of Aging (NIA T32000243). JMP was supported by the McHugh Otolaryngology Research Fund, an American Geriatrics Society/Dennis W. Jahnigen Scholar Award, the National Institute of Aging (AG12857, K23 AG036762), the Institute for Translational Medicine (KL2RR025000, UL1RR024999), and the National Institute on Aging (K23 AG036762) at The University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Data from NSHAP Wave 1 (Waite, Linda J., Edward O. Laumann, Wendy Levinson, Stacy Tessler Lindau, and Colm A. O’Muircheartaigh. National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP): Wave 1. ICPSR20541-v6. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2014-04-30. doi:10.3886/ICPSR20541.v6) and Wave 2 (Waite, Linda J., Kathleen Cagney, William Dale, Elbert Huang, Edward O. Laumann, Martha McClintock, Colm A. O’Muircheartaigh, L. Phillip Schumm, and Benjamin Cornwell. National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP): Wave 2 and Partner Data Collection. ICPSR34921-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2014-04-29. doi:10.3886/ICPSR34921.v1) are available for public use at http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/landing.jsp

References

- Albertsen I. M., Temprado J. J., Berton E. (2012). Effect of haptic supplementation provided by a fixed or mobile stick on postural stabilization in elderly people. Gerontology, 58, 419–429. 10.1159/000337495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babizhayev M. A., Deyev A. I., Yegorov Y. E. (2011). Olfactory dysfunction and cognitive impairment in age-related neurodegeneration: Prevalence related to patient selection, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic treatment of aged clients receiving clinical neurology and community-based care. Current Clinical Pharmacology, 6, 236–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K. K. (2003). Real-world evaluation of visual function. Ophthalmology Clinics of North America, 16 , 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesveldt S., Lindau S. T., McClintock M. K., Hummel T., Lundstrom J. N. (2011). Gustatory and olfactory dysfunction in older adults: A national probability study. Rhinology, 49 , 324–330. 10.4193/Rhino10.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J. (2011). Marital quality as a moderator of the effects of poor vision on quality of life among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66 , 605–616. 10.1093/geronb/gbr091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J., Lawson B. (2011). Poor vision, functioning, and depressive symptoms: A test of the activity restriction model. Gerontologist, 51 , 798–808. 10.1093/geront/gnr051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M. F. (1980). The relation of tactile thresholds to histology in the fingers of elderly people. The Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 43 , 730–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R. C., McClintock M. K., Kern D. K., Pinto J. M., Dale W. (2013). National prevalence of vision impairment in the home and vision “pessimism” in older adults. Grapevine, TX: American Geriatrics Society. [Google Scholar]

- Ciorba A., Bianchini C., Pelucchi S., Pastore A. (2012). The impact of hearing loss on the quality of life of elderly adults. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 7, 159–163. 10.2147/CIA.S26059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gescheider G. A., Bolanowski S. J., Hall K. L., Hoffman K. E., Verrillo R. T. (1994). The effects of aging on information-processing channels in the sense of touch: I. Absolute sensitivity. Somatosensory and Motor Research, 11 , 345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goble A. K., Collins A. A., Cholewiak R. W. (1996). Vibrotactile threshold in young and old observers: The effects of spatial summation and the presence of a rigid surround. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 99(4 Pt. 1), 2256–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg C., Maul E., Chan E. S., Van Landingham S., Ferrucci L., Friedman D. S., Ramulu P. Y. (2012). Association of vision loss in glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration with IADL disability. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 53 , 3201–3206. 10.1167/iovs.12-9469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely K. M., Gopinath B., Mitchell P., Luszcz M., Anstey K. J. (2012). Cognitive, health, and sociodemographic predictors of longitudinal decline in hearing acuity among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 67 , 997–1003. 10.1093/gerona/gls066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafreniere D., Mann N. (2009). Anosmia: Loss of smell in the elderly. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 42, 123–131, x. 10.1016/j.otc.2008.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam B. L., Christ S. L., Zheng D. D., West S. K., Munoz B. E., Swenor B. K., Lee D. J. (2013). Longitudinal relationships among visual acuity and tasks of everyday life: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation study. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 54, 193–200. 10.1167/iovs.12-10542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante-Levesque A., Hickson L., Worrall L. (2010). Rehabilitation of older adults with hearing impairment: A critical review. Journal of Aging and Health, 22, 143–153. 10.1177/ 0898264309352731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau S. T., Schumm L. P., Laumann E. O., Levinson W., O’Muircheartaigh C. A., &, Waite L. J. (2007). A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357 , 762–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C. (1993). Nutrition and chemosensory perception in the elderly. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 33, 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Muircheartaigh C., Eckman S., Smith S. (2009). Statistical design and estimation for the national social life, health, and aging project. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64(Suppl. 1, i12–i19. 10.1093/geronb/gbp045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedroso R. V., Coelho F. G., Santos-Galduroz R. F., Costa J. L., Gobbi S., Stella F. (2012). Balance, executive functions and falls in elderly with Alzheimer’s disease (AD): A longitudinal study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 54, 348–351. 10.1016/j.archger.2011.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto J. M., Schumm L.P., Wroblewski K., Kern D.W., McClintock M. K. (2004). Racial disparities in olfactory loss among older adults in the United States. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 69, 323–329. 10.1093/gerona/glt063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ramulu P. Y., West S. K., Munoz B., Jampel H. D., Friedman D. S. (2009). Driving cessation and driving limitation in glaucoma: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation Project. Ophthalmology, 116, 1846–1853. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert C. R., Cruickshanks K. J., Klein B. E., Klein R., Nondahl D. M. (2011). Olfactory impairment in older adults: Five-year incidence and risk factors. Laryngoscope, 121, 873–878. 10.1002/lary.21416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm L. P., McClintock M., Williams S., Leitsch S., Lundstrom J., Hummel T., Lindau S. T. (2009). Assessment of sensory function in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64(Suppl. 1, i76–i85. 10.1093/geronb/gbp048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzman R. (2009). The National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project: An introduction. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64(Suppl. 1, i5–i11. 10.1093/geronb/gbp078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornbury J. M., Mistretta C. M. (1981). Tactile sensitivity as a function of age. The Journals of Gerontology, 36, 34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrillo R. T., Bolanowski S. J., Gescheider G. A. (2002). Effect of aging on the subjective magnitude of vibration. Somatosensory and Motor Research, 19, 238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesterager V., Salomon G. (1990). Psychosocial aspects of hearing impairment in the elderly. Acta Oto-laryngologica. Supplementum, 476, 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viljanen A., Kulmala J., Rantakokko M., Koskenvuo M., Kaprio J., Rantanen T. (2012). Fear of falling and coexisting sensory difficulties as predictors of mobility decline in older women. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 67, 1230–1237. 10.1093/gerona/gls134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside M. M., Wallhagen M. I., Pettengill E. (2006). Sensory impairment in older adults: Part 2: Vision loss. The American Journal of Nursing, 106, 52–61; quiz 61–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.