Abstract

Introduction

The Rac-GEF P-REX1 is a key mediator of ErbB signaling in breast cancer recently implicated in mammary tumorigenesis and metastatic dissemination. Although P-REX1 is essentially undetectable in normal human mammary epithelial tissue, this Rac-GEF is markedly upregulated in human breast carcinomas, particularly of the luminal subtype. The mechanisms underlying P-REX1 upregulation in breast cancer are unknown. Toward the goal of dissecting the mechanistic basis of P-REX1 overexpression in breast cancer, in this study we focused on the analysis of methylation of the PREX1 gene promoter.

Methods

To determine the methylation status of the PREX1 promoter region, we used bisulfite genomic sequencing and pyrosequencing approaches. Re-expression studies in cell lines were carried out by treatment of breast cancer cells with the demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycitidine. PREX1 gene methylation in different human breast cancer subtypes was analyzed from the TCGA database.

Results

We found that the human PREX1 gene promoter has a CpG island located between -1.2 kb and +1.4 kb, and that DNA methylation in this region inversely correlates with P-REX1 expression in human breast cancer cell lines. A comprehensive analysis of human breast cancer cell lines and tumors revealed significant hypomethylation of the PREX1 promoter in ER-positive, luminal subtype, whereas hypermethylation occurs in basal-like breast cancer. Treatment of normal MCF-10A or basal-like cancer cells, MDA-MB-231 with the demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycitidine in combination with the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A restores P-REX1 levels to those observed in luminal breast cancer cell lines, suggesting that aberrant expression of P-REX1 in luminal breast cancer is a consequence of PREX1 promoter demethylation. Unlike PREX1, the pro-metastatic Rho/Rac-GEF, VAV3, is not regulated by methylation. Notably, PREX1 gene promoter hypomethylation is a prognostic marker of poor patient survival.

Conclusions

Our study identified for the first time gene promoter hypomethylation as a distinctive subtype-specific mechanism for controlling the expression of a key regulator of Rac-mediated motility and metastasis in breast cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13058-014-0441-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Rho/Rac GTPases are effectors of cell surface receptors that control fundamental cellular functions, including actin cytoskeleton dynamics, cell morphology, motility, and the progression through the cell cycle [1]. Like most GTPases, Rac cycles between a GDP-bound inactive state and a GTP-bound active state responsible for the activation of downstream effectors. This switch is tightly regulated by Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factors (Rac-GEFs) that promote GTP loading onto Rac, and Rac GTPase activating proteins (Rac-GAPs) that inactivate Rac by accelerating GTP hydrolysis [1]-[3]. Extensive evidence supports a role for Rac in tumorigenesis as well as in the acquisition of a highly motile phenotype required for metastatic dissemination of cancer cells [4]-[6]. Alterations of Rac signaling are common in human cancer and can involve upregulation of Rac itself, expression of an active spliced variant (Rac1b), or very rarely Rac gain-of-function mutations and Rac-GAP downregulation [7]-[13]. However, the most common mechanism that accounts for Rac hyperactivation in human cancer is the dysregulation of Rac-GEF function [14]-[16]. A number of studies have indeed reported overexpression and activating mutations of Rac-GEFs in cancer, as described for Tiam1, Trio, and others [14]-[21]. Exacerbated inputs from pathways required for the activation of Rac-GEFs, such as PI3K or receptors that are coupled to PI3K activation (for example HER2/ErbB2 or PDGF receptors), also confer Rac hyperactivation [3],[6],[22],[23].

Using a PCR-based array screening approach, our laboratory previously reported that the PI3K- and Gβγ-dependent Rac-GEF P-REX1 is highly expressed in breast cancer [24]. P-REX1 was found to be an essential mediator of HER2-driven activation of Rac and motility in breast cancer cells by integrating signals emanating from tyrosine-kinases and G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [24],[25]. RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated silencing of P-REX1 essentially impairs the ability of breast cancer cells to form tumors in nude mice as well as their migratory capacity, suggesting its potential involvement in breast tumorigenesis and metastasis [24]. P-REX1 is essentially undetectable by immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis in human normal mammary epithelial tissue, whereas its expression can be readily detected in approximately 60% of breast tumors [24]. Elevated P-REX1 expression in breast tumors has been associated with poor outcome and development of metastasis in patients [24],[25]. Analysis of P-REX1 expression using the Netherlands Cancer Institute (NKI) microarray data and more recently through metagenomic analysis of Rho/Rac GEFs established that P-REX1 upregulation occurs in a subset of tumors, specifically those of the luminal subtype. On the other hand, P-REX1 levels are low in basal-like breast cancer, a subtype with high abundance of triple-negative (estrogen receptor (ER)-, progesterone receptor (PR)-, and human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER2)-negative) tumors [21],[24]. In addition to P-REX1, luminal tumors express high levels of VAV3, a Rho/Rac GEF that was found to drive a lung-specific metastatic transcriptional program in breast cancer cells [21]. Consistent with data observed in breast cancer, P-REX1 has been implicated in metastasis in prostate cancer and melanoma [26],[27].

As luminal breast cancer is the most common subtype and responsible for the largest number of breast cancer deaths [28],[29], understanding the regulation and function of these Rac-GEFs is highly relevant. Deciphering the mechanisms leading to overexpression of tumorigenic and metastatic proteins is key to identify novel approaches to counterbalance dysregulated oncogenic stimuli in cancer. In this regard, the molecular mechanisms underlying P-REX1 upregulation in luminal breast cancer remain unknown. Extensive evidence suggests that epigenetic events including DNA methylation and histone modifications play important roles in the transcriptional regulation of oncogenic/metastatic genes in many cancer types, including breast cancer [30]-[32]. DNA methylation of promoter CpG islands results in transcriptional silencing, and dysregulation of this epigenetic mechanism plays an important role in oncogenesis and cancer progression [31]. Towards the goal of dissecting the mechanistic basis of P-REX1 overexpression in breast cancer, in this study we focused on the analysis of methylation of the PREX1 gene promoter. We found that derepression of P-REX1 expression in luminal breast cancer involves the demethylation of its promoter. A comprehensive analysis of human mammary cell lines and patient-derived tumors revealed marked differences in PREX1 promoter methylation in distinct breast cancer subtypes that inversely correlate with P-REX1 expression levels. The dissection of the mechanisms leading to P-REX1 upregulation in breast cancer may have significant prognostic and therapeutic value.

Methods

Cell lines

Human breast cell lines (BT-474, BT-549, HCC1419, HMEC, MCF-10A, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-361, MDA-MB-453, MDA-MB-468 and T-47D) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA), except for HMEC cells that were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD, USA). Cells were grown in the medium recommended by the providers.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was carried out essentially as described previously [33]. Briefly, cells growing in monolayer at a confluence of 80% were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxychloride, and protease/phosphatase inhibitors). Ten μg of total protein lysate were loaded onto 8% acrylamide gels, transferred into PVDF membranes, and incubated with anti-human P-REX1 antibody (1:1,000, Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO, USA) or anti-ER-alpha antibody (1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Dallas, TX, USA). For loading normalization we used anti-β-actin antibody (1:10,000, Sigma-Aldrich). Anti-rabbit (1:1,000, Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, USA) and anti-mouse (1:5,000, Bio-Rad) antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase were used as secondary antibodies. Bands were visualized using the ECL Western blotting detection system. Images were captured with a Fuji LAS-3000 Imaging System, as previously described [34].

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA from cells was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen; Valencia, CA, USA). One μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA with the TaqMan Reverse Transcription Kit (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA, USA). Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed in triplicate in a total volume of 25 μl containing 10 to 100 ng cDNA, TaqMan universal PCR MasterMix (Applied Biosystems; Branchburg, NJ, USA), target primers (45 nM), and fluorescent probe (12.5 nM), using an ABI PRISM 7700 detection system. TaqMan probes specific for PREX1, VAV3, ESR1 and the housekeeping genes B2M and UBC (used for normalization) were obtained from Applied Biosystems. PCR product formation was continuously monitored using the Sequence Detection System software version 1.7 (Applied Biosystems).

Analysis of CpG islands in the PREX1 and VAV3 gene promoters

The presence of CpG islands in the human PREX1 (NM_020820) and VAV3 (NM_006113) gene promoters was determined using the Methyl Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems).

Bisulfite sequencing and pyrosequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from cell lines in culture using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). For bisulfite sequencing, 1 μg of genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite and hydroquinone [35] and purified using the Wizard DNA Clean-up system (Promega; Madison, WI, USA). Bisulfite treated-genomic DNA was used as a template to amplify specific promoter regions of PREX1 and VAV3, using the Go-Taq Hot Start Polymerase (Promega). Primer pairs in bisulfite-sequencing PCRs were as follows: 5′-GGAGGATTTTGGAGTTAGGTAT (PREX1-BSP1-Forward), 5′-AACAAATACCCTACCTACTCCC (PREX1-BSP1-Reverse), 5′-TTAGGGGGTAAAGAAGTTTAGA (PREX1-BSP2-Forward), 5′-AACCAAATAAACACCA/GAACT (PREX1-BSP2-Reverse), 5′-GTTAGAATGGAGGC/TGTTTAG (PREX1-BSP3-Forward), 5′-AAAACTATCCCCAAACTCC (PREX1-BSP3-Reverse), 5′-GGGATTC/TGAGTTTTTTTAGA (PREX1-BSP4-Forward), 5′-ACTCCAACAAAAACCTATACAT (PREX1-BSP4-Reverse), 5′-TTTAAGTAGGTTTTTGTGGGGT (VAV3-BSP-Forward) and 5′-CAAACTCCCCAAAACAATAAA (VAV3-BSP-Reverse). The thermal cycle conditions consisted of 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 57°C for 30 sec, and elongation at 72°C for 1 min, and then an incubation at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were cloned into the TopoTA vector (Invitrogen). Eight clones for each PCR reaction were randomly selected and sequenced.

For pyrosequencing, bisulfite treated-genomic DNA obtained from cell lines in culture was amplified using the Hs_PREX1_04_PM PyroMark CpG assay (Qiagen) specific for the human PREX1 promoter, and the PyroMark PCR Kit (Qiagen), using the conditions described by the manufacturer. Pyrosequencing was performed in the Genetic Resources Core Facility at Johns Hopkins University.

5-aza-2′-deoxycitidine and trichostatin A treatment

Cells growing in complete media were treated with 10 μΜ 5-aza-2′-deoxycitidine (AZA) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 96 h and/or 100 ng/ml trichostatin A (TSA) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h. At the end of treatment, P-REX1 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR as described above.

Microarray analysis

For PREX1 expression and methylation profiles, processed cell line expression data was downloaded from ArrayExpress under the accession number E-TAMB-157 [36]. Processed cell line methylation data was obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the accession number GSE42944 [37]. Gene expression and Illumina 450 k Human Methylation array data for The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) breast cancer samples were obtained from the TCGA data portal. Expression data from MCF-7 cells with ER-alpha depletion was obtained from the GEO database under the accession number GSE27473 [37]. Statistical analyses for microarrays were performed using the R Biostatistical Program [38] with annotation packages installed from Bioconductor [39].

Clinical annotations for the TCGA datasets were obtained from the TCGA data portal. Samples in which ER status was indeterminate were excluded from the ER analysis. HER2 amplification status was given as two variables: FISH and IHC. Equivocal and indeterminate calls were excluded and when discordance occurred between both calls, priority was given to the FISH assay.

Transfections and luciferase reporter gene assays

For luciferase reporter assays, cells in 12-well plates were co-transfected with 1 μg of pGL3-PREX1 promoter constructs [40] or empty vector, and 0.1 ng of the Renilla reporter vector pRL-TK (Promega), using the transfection reagent X-tremeGENE HP (Roche; Indianapolis, IN, USA). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed with passive lysis buffer (Promega), and luciferase activity determined in cell extracts using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

For transient depletion of ER-alpha, we used ESR1 ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool, (Catalog # L-003401-00-0005), from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA). ON-TARGETplus Non-Targeting pool (Catalog # D-001810-0-05) was used as a control. RNAi was transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen) following instructions from the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni corrections was applied, with P <0.05 considered as statistically significant. Statistical significance for gene expression and probe methylation from cell line and TCGA datasets were assessed using the Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni correction across groups. Bonferroni correction was also applied when a given gene was analyzed with more than one probe. For these tests, P <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Pairwise correlations were calculated using the Spearman’s ranked correlation test, with P <0.05 considered as statistically significant. For the Kaplan-Meier curves, groups of low and high methylation were defined via bifurcation using the median beta value of the specific probe. Statistical difference between survival curves was calculated using the log-rank test.

Results

Differential methylation of the PREXgene in breast cancer subtypes

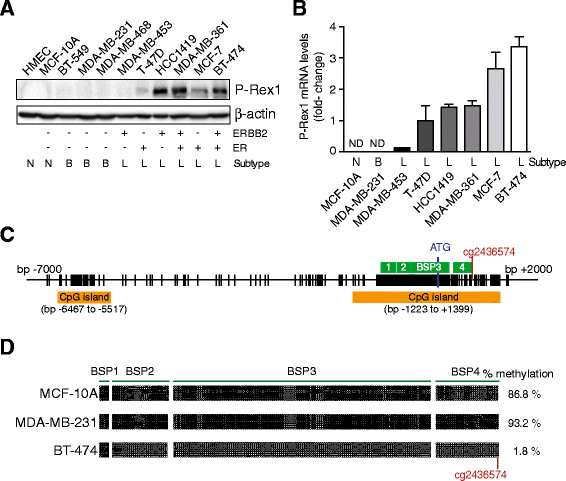

We have previously established that the Rac-GEF P-REX1 is overexpressed in breast cancer relative to normal breast tissue, and a positive correlation was found with ER-positive breast tumors [24]. Analysis of databases from human breast specimens revealed elevated P-REX1 mRNA levels mainly in luminal A and luminal B subtypes, whereas expression in the basal-like breast cancer subtype was very low [21],[24]. To extend these results to cellular models, we analyzed P-REX1 expression in a number of human breast cancer cell lines. Western blot analysis showed elevated P-REX1 protein levels in most luminal breast cancer cell lines examined (T-47D, HCC1419, MDA-MB-361, MCF-7, BT-474). On the other hand, P-REX1 was essentially undetectable in basal-like cell lines (BT-549, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468) or in normal mammary epithelial cells (HMEC, MCF-10A) (Figure 1A). This distinctive pattern of expression could also be detected at the mRNA level, as determined by qPCR (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Differential P-REX1 expression and methylation of the PREX1 gene promoter in mammary cell lines. Panel A. P-REX1 levels in human breast cell lines were determined by Western blot. β-actin was used as loading control. N, normal; B, basal-like; L, luminal. Panel B. Quantitative PCR determination of P-REX1 mRNA levels in human breast cancer cell lines, normalized to those in T-47D cells. B2M and UBC were used as housekeeping genes. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples. A second additional experiment gave similar results. As P-REX1 mRNA levels in MCF-10A are non detectable (ND), statistical analysis is not provided. Panel C. Schematic representation of the PREX1 gene promoter. The location of the two CpG islands, the four regions amplified by BSPs, and the ATG codon are indicated. Panel D. DNA methylation of the PREX1 promoter was determined by bisulfite sequencing PCR. Each dot represents the methylation status of a CpG dinucleotide in one sequenced BSP clone. Black dot, methylated CpG; white dot, unmethylated CpG.

To dissect the mechanisms behind the differential expression of P-REX1 in breast cancer, we turned our attention to gene promoter methylation. DNA methylation of CpG dinucleotides is an epigenetic alteration that induces transcriptional silencing, and its dysregulation has profound roles on the expression of genes linked to oncogenesis and tumor progression [31]. Analysis of the PREX1 gene promoter sequence using the Methyl Primer Express software revealed two major CpG islands, defined as sequences covering more than 200 bp with a C + G content over 50% and an observed-to-expected CpG ratio >0.6 [41]. The first CpG island is located 6.5 to 5.5 kb upstream from the ATG start codon. The second (and largest) CpG island is located between -1.2 kb and +1.4 kb, and it includes the first exon of the PREX1 gene. This proximal CpG island is particularly rich in C + G bases and has an observed-to-expected CpG ratio >0.75 (Figure 1C).

In order to determine the methylation status of the PREX1 promoter region, we utilized a bisulfite genomic sequencing approach, using three representative breast cell lines for normal (MCF-10A), basal-like (MDA-MB-231), and luminal (BT-474) subtypes. Four different bisulfite sequencing PCRs (BSPs) were designed in order to cover most of the proximal CpG island. This analysis revealed prominent hypermethylation of the PREX1 promoter in MCF-10A cells (86.8% CpG dinucleotides methylated) and MDA-MB-231 cells (93.2%). On the other hand, this CpG island was essentially unmethylated in BT-474 cells (1.8%) (Figure 1D). Thus, the methylation status of the PREX1 promoter inversely correlates with P-REX1 mRNA and protein levels in MCF-10A, MDA-MB-231 and BT-474 cells.

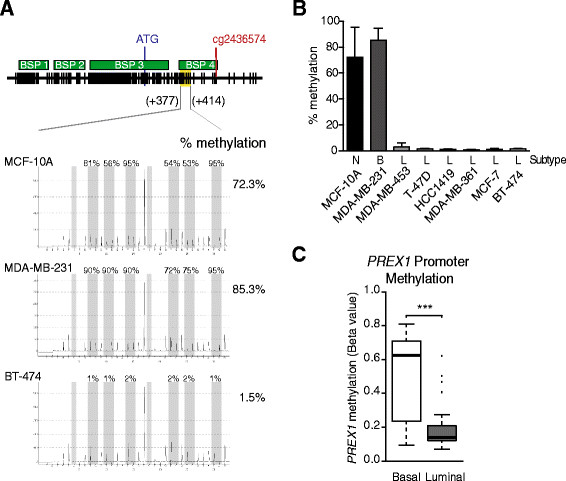

To further establish a relationship between PREX1 gene methylation and P-REX1 expression in cell lines, we determined DNA methylation levels by pyrosequencing, a fully quantitative methylation assessment. Methylation was determined using a PyroMark CpG assay in a region between +377 bp and +414 bp in the PREX1 promoter that includes six CpG dinucleotides. In agreement with results from the BSP analysis, pyrosequencing revealed high methylation in normal MCF-10A and basal-like MDA-MB-231 cells (72.3% and 85.3% methylation, respectively). On the other hand, methylation was essentially undetectable in luminal cell lines (<3% in all cell lines examined) (Figure 2A and 2B), which in all cases display high P-REX1 mRNA levels by qPCR (see Figure 1B).

Figure 2.

DNA methylation status of the PREX1 promoter in human mammary cell lines. Panel A. Schematic representation of the PREX1 promoter region studied with the Hs_PREX1_04_PM PyroMark CpG assay (Qiagen), and representative pyrosequencing experiments for MCF-10A, MDA-MB-231, and BT-474 cell lines. Panel B. Pyrosequencing results of the PREX1 methylation in breast cancer cell lines. Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. of the percentage of methylation for the six CpG dinucleotides measured by the pyrosequencing assay. Panel C . The PREX1 promoter methylation levels for probe cg24364574 across 51 cancer cell lines from the Infinium HumanMethylation27 BeadChip array (GEO accession number: GSE42944). (***, P <0.0001).

Next, we analyzed the methylation status of PREX1 in 51 breast cancer cell lines obtained from the Infinium HumanMethylation27 BeadChip array (Illumina; San Diego, CA, USA); GSE42944 [37]). This array contains data on cg24364574, a CpG dinucleotide located at bp +703 in the PREX1 gene promoter. Again, this analysis revealed major differences between basal-like cell lines that display high methylation on cg24364574 and luminal-derived cell lines (Figure 2C; P <0.001). Taken together, analysis of human mammary cell lines argue for a major role of methylation in repressing the expression of P-REX1 in normal breast tissue and basal-like breast tumors. It is conceivable that derepression of P-REX1 expression in luminal breast cancer is associated with demethylation of the PREX1 promoter.

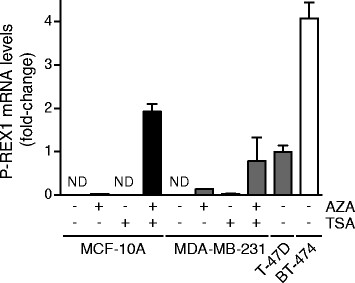

Rescue of P-REX1 expression in normal mammary and basal-like breast cancer cells by 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine

To determine if P-REX1 expression is regulated by methylation, we used the demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (AZA). As histone deacetylation usually works together with DNA methylation in the silencing of genes [42],[43], AZA treatment was done either in the presence or absence of the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA). As shown in Figure 3, combined AZA/TSA treatment rescued P-REX1 expression in MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cells to levels in the range of those observed in T-47D or BT-474 cells. P-REX1 expression could not be rescued by treatment with AZA or TSA alone. These results suggest that the PREX1 promoter is inactivated by DNA methylation in non-expressing cell lines, and that demethylation in combination with acetylation of associated histones is sufficient to rescue P-REX1 expression.

Figure 3.

AZA restores the expression of P-REX1 in MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were treated with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (AZA) (10 μM, 96 h) and/or trichostatin A (TSA) (24 h, 100 ng/ml). Total RNA was isolated, reverse transcribed, and used for the determination of P-REX1 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR. T-47D and BT-474 breast cancer cell lines were used as positive controls for P-REX1 expression in luminal breast cancer cell lines. P-REX1 mRNA levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene B2M and expressed as relative to those in T-47D cells. Similar results were observed in two additional experiments. As P-REX1 mRNA levels in non-treated MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cells are non detectable (ND), statistical analysis is not provided.

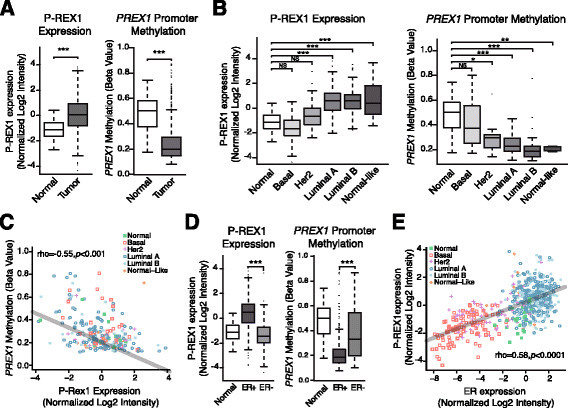

Analysis of PREXmRNA expression and promoter methylation in human breast specimens from the TCGA database revealed presence of major differences in breast cancer subtypes

Following the studies in mammary cell lines, we next examined PREX1 gene methylation in human breast cancer specimens using the TCGA public database. In agreement with IHC data [24], this database also showed significant P-REX1 mRNA upregulation in primary breast carcinomas vs. normal breast tissue samples (Figure 4A, left panel, P <0.001). Analysis of cg24364574 methylation status in the TCGA database revealed significantly lower methylation in primary breast tumors relative to normal breast tissue (Figure 4A, right panel, P <0.001).

Figure 4.

Analysis of PREX1 methylation and mRNA expression in the TCGA dataset. Panel A . P-REX1 mRNA expression (left) and promoter methylation (right) in breast tumors and normal breast tissue (*** = P <0.0001). Panel B . P-REX1 mRNA expression (left) and promoter methylation (right) across different breast cancer subtypes (*, P <0.05; **, P <0.01; ***, P <0.001). Panel C . Inverse correlation between P-REX1 mRNA levels and PREX1 methylation in different subtypes of breast tumors and normal breast tissue (Spearman rho = -0.55, P <0.0001). Panel D . P-REX1 mRNA expression (left) and promoter methylation (right) in normal tissue, estrogen receptor (ER)-positive and ER-negative breast tumors (***, P <0.0001). Panel E . Correlation analysis between P-REX1 and ER-alpha expression in different subtypes of human breast tumors and normal breast samples (Spearman rho =0.85, P <0.0001). TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

The TCGA database showed significantly higher levels of P-REX1 in luminal A and B breast cancer relative to other cancer subtypes and normal tissues (Figure 4B, P <0.001). Analysis of cg24364574 methylation status in the TCGA database revealed remarkable differences among the different breast cancer subtypes. Specifically, high methylation was observed in both basal-like tumors and normal breast tissue, whereas a profound hypomethylation in PREX1 was detected in those subtypes with high P-REX1 expression, namely luminal A/B and normal-like subclasses (Figure 4B, P <0.01). The HER2/ErbB2 subtype displays slightly higher levels of methylation compared to those of luminal subtype. Figure 4C shows a clear inverse correlation between P-REX1 expression levels and PREX1 gene promoter methylation status in human breast cancer and normal breast specimens (rho = -0.55; P <0.001).

Further analysis using the TCGA database revealed PREX1 hypomethylation in ER-positive tumors relative to ER-negative breast tumors (Figure 4D, left panel, P <0.001), which inversely correlates with P-REX1 mRNA expression (Figure 4D, right panel, P <0.001). In fact, P-REX1 levels in breast tumors positively correlates with the expression of the ER-alpha gene, ESR1 (Figure 4E, rho =0.58; P <0.0001). Interestingly, analysis from the GSE27473 database revealed significant reduction in P-REX1 mRNA expression in MCF-7 cells upon ER-alpha short hairpin (sh)RNA depletion. We validated these results experimentally both in MCF-7 and T-47D cells (Figure S1 in Additional file 1). Our analysis did not reveal statistically significant changes in PREX1 methylation when we compared HER2/ErbB2-positive and HER2/ErbB2-negative tumors (Figure S2 in Additional file 2).

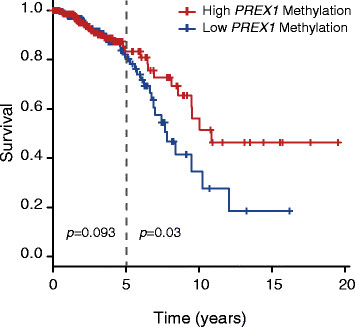

Demethylation of the PREXpromoter gene is associated with reduced breast cancer survival

Montero et al. reported a correlation between P-REX1 expression and poor patient outcome in breast cancer [25]. In addition, we previously observed that expression of P-REX1 in primary breast tumors is statistically significantly associated with the development of metastasis [24]. We therefore asked if methylation of the PREX1 promoter is linked to survival in patients with breast cancer. As shown in Figure 5, low PREX1 methylation associates with elevated risk of breast cancer mortality. This association becomes statistically significant when we compare patient survival five years after initial diagnosis (P =0.03), suggesting a notable trend of poor long-term survival in patients with lower PREX1 methylation.

Figure 5.

PREX1 methylation predicts poor survival of breast cancer patients. Kaplan-Meier curve and log-rank test for the survival of breast cancer patients with low or high PREX1 methylation levels was obtained from the TCGA database. Two P values were calculated, one for the comparison of the two groups since time 0 (P =0.093), and a second one after year 5 (P =0.03). TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

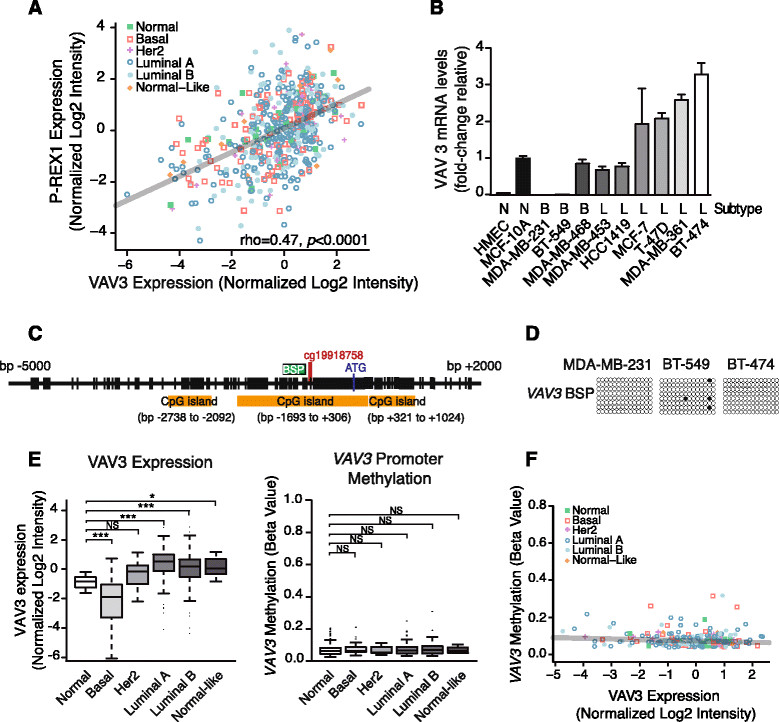

VAVexpression in breast cancer is not regulated by methylation

Citterio et al. recently reported that other Rac-GEFs in addition to P-REX1 are upregulated in luminal breast cancer. Specifically, VAV3 is overexpressed in luminal breast cancer cells, and this drives a transcriptional program for metastatic dissemination to the lungs. Moreover, VAV3 upregulation correlates with ER and PR expression in breast cancer cells [21]. Concordant with these data, we found a strong correlation between P-REX1 and VAV3 expression in human breast samples (Figure 6A; rho =0.47; P <0.0001). VAV3 mRNA levels tend to be higher in luminal-derived breast cancer cell lines than in basal-like cancer cell lines or normal mammary cells (Figure 6B). We then asked if VAV3 expression is regulated by methylation. The Methyl Primer Express software identified three CpG islands in the VAV3 gene promoter (Figure 6C). For the analysis of the methylation status of the VAV3 promoter we used bisulfite sequencing. Cell lines with low VAV3 expression (MDA-MB-231 and BT-549, basal-like) and high VAV3 expression (BT-474, luminal) were selected. As shown in Figure 6D, sequencing of the BSP region comprising bp -989 to -643 revealed essentially no CpG island methylation in these cell lines. Using the TCGA database, we analyzed the methylation status of the CpG dinucleotide cg19918758 located at bp -623 in the VAV3 promoter. We found low methylation across all samples and no significant differences in the pattern of methylation between the different breast cancer subtypes (Figure 6E). Additionally, there is no statistically significant correlation between VAV3 promoter methylation and VAV3 mRNA expression (Figure 6F; rho = -0.10; P =0.13). Therefore, methylation plays a major role in controlling P-REX1 expression in breast cancer; however, it does not seem to be a primary mechanism for the control of VAV3 expression.

Figure 6.

VAV3 expression is not regulated by promoter methylation. Panel A . Correlation analysis for P-REX1 and VAV3 expression in breast tumors and normal breast tissue was obtained from the TCGA database (Spearman rho =0.47, P <0.0001). Panel B . Quantitative PCR determination of VAV3 mRNA levels in human breast cancer cell lines, normalized to those in immortalized normal breast epithelial cells, MCF-10A cells. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples. B2M and UBC were used as housekeeping genes. A second additional experiment gave similar results. Panel C . Schematic representation of the VAV3 gene promoter. The location of the three CpG islands, the region amplified by BSP, and the ATG codon are indicated. Panel D . DNA methylation of the VAV3 promoter was determined by bisulfite sequencing PCR. Each dot represents the methylation status of a CpG dinucleotide in one sequenced BSP clone. Black dot, methylated CpG; white dot, unmethylated CpG. Panel E . VAV3 mRNA expression (left) and promoter methylation (right) across different breast cancer subtypes and normal mammary tissue were obtained from the TCGA database (*, P <0.05; ***, P <0.001). Panel F . Correlation analysis for VAV3 mRNA expression and VAV3 promoter methylation. No significant correlation was observed (Spearman rho = -0.10, P =0.14). TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

Discussion

Rac plays important roles in breast cancer cell migration and invasiveness and is upregulated in invasive human breast cancer [7]-[9],[11]-[13]. Previous studies identified the Rac-GEF P-REX1 as a mediator of Rac1 activation and motility of breast cancer cells in response to growth factors and chemokines [24],[25],[44]. P-REX1 is predominantly upregulated in luminal A and B breast cancer, and its expression is higher in primary breast tumors from patients that ultimately develop metastasis. P-REX1-positive cells can be readily detected in the lymph nodes of patients with breast cancer, strongly arguing for the involvement of this Rac-GEF in the local metastatic dissemination of breast cancer cells [24]. In addition to its involvement in breast cancer, P-REX1 also confers an invasive phenotype to prostate cancer and melanoma cells [26],[27]. The main goal of this study was to decipher the mechanisms behind P-REX1 upregulation in luminal breast cancer, which remained unexplored to date. Our results identified methylation of the PREX1 gene promoter as a key mechanism implicated in the differential expression of P-REX1 in breast cancer. On the other hand, methylation does not seem to be involved in the upregulation of VAV3, a Rho/Rac-GEF also implicated in breast cancer metastasis [21], despite the presence of CpG islands in the VAV3 gene promoter. VAV3 is basally expressed in all different breast cancer subtypes despite a preferential overexpression in luminal breast cancer, thus suggesting that mechanisms other than promoter methylation regulate its differential expression.

The PREX1 promoter has two CpG islands, one of them very rich in C + G bases located between -1.2 kb and +1.4 kb. Our results indicate a differential methylation pattern of this CpG island between different breast cancer subtypes. A systematic analysis of human breast cancer cell lines and tumors revealed that this promoter region is highly methylated in the normal breast epithelium and basal-like breast cancer, and hypomethylated in luminal breast cancer. The inverse correlation found between PREX1 promoter methylation and P-REX1 expression strongly indicates a role for this epigenetic mechanism in regulating the P-REX1-Rac signaling pathway in breast cancer cells through the control of P-REX1 expression. Additionally, P-REX1 expression can be induced by treatment with the demethylating agent AZA in combination with the HDAC inhibitor TSA in breast cell lines with PREX1 promoter hypermethylation. Regardless of few studies suggesting indirect effects of these agents [45],[46], our results argue for a distinctive demethylation of the PREX1 promoter that contributes to its upregulation in the luminal subtype. Interestingly, an association between PREX1 promoter hypomethylation and reduced overall survival in patients was observed, which reaches statistical significance when considering patients five years after diagnosis. It should be noted that a previous reported analysis of clinical data indicates that patients with elevated P-REX1 levels in breast tumors had a shorter disease-free survival, and a multivariate analysis for known prognostic markers in breast cancer showed that P-REX1 is an independent marker [25]. Taken together, these findings support the concept that the methylation status of the PREX1 promoter is causally linked to P-REX1 upregulation and associates with poor outcome of breast cancer patients, thus implying PREX1 methylation as a prognostic factor. Although basal-like tumors have the worse prognosis particularly within the first five years after diagnosis [47], most breast cancers belong to the luminal type. Therefore, survival correlations with P-REX1 expression most likely include luminal breast cancer patients as the largest population, thus arguing the possibility that PREX1 promoter methylation has prognostic value to predict outcome in this subset of patients. It is important to note that studies using three-dimensional organotypic cultures showed that Rac activity is important for tumor invasion regardless of subtype [13]. This suggests that Rac-GEFs other than P-REX1 are implicated in Rac activation in basal-like tumors.

DNA methylation is a primary epigenetic mechanism for the silencing of genes that has been widely associated with all stages of cancer development, and specific methylation events have been used as biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis [48],[49]. One well-established alteration linked to cancer development is the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes by DNA methylation. For example, epigenetic silencing by methylation of PTEN and BRCA1 genes is a hallmark of breast cancer [50],[51]. Predictably, inhibition of DNA methylation has been extensively considered as a therapeutic approach, and DNA methylation inhibitors have been approved for cancer therapy [52]. Notwithstanding, fewer studies have addressed a role for abnormal demethylation in cancer, although hypomethylation of the genome has been increasingly recognized as a cancer-linked trait, including in breast cancer [53],[54]. For example, early studies found that hypomethylation of cancer-linked satellite 2 (Sat2) in chromosome 1 is significantly associated with ovarian and breast cancer [53],[55]. Subsequent studies showed that the expression of oncogenic proteins could be activated by abnormal hypomethylation, as shown for MYC, H-RAS, R-RAS, BCL2 and PIK3CA[56]-[61]. Landscapes of promoter demethylation and common hypomethylation signatures have also been established for various cancers [62]-[65]. In addition, DNA demethylation occurs during the process of malignant cell transformation by oncogenes and carcinogenic agents [66]-[68], and reduced methylation in normal tissue was shown to predict predisposition to multiple cancers [69]. Most remarkably, global expression analysis identified hypomethylation of pathways critical for growth and metastasis in cancer [62],[70],[71]. Indeed, hypomethylation of gene promoters for invasive/metastatic proteins such as uPA and MMP2 has been reported [72]-[74]. There is so far little evidence that components of the Rac pathway, a cascade that plays fundamental roles in motility and invasiveness, could be regulated at the epigenetic level. One study showed that expression of the metastatic exchange factor Tiam1 in colon cancer is inversely related to the methylation status of its promoter; however, TIAM1 gene hypermethylation also occurs in many tumors, and a clear relationship with metastasis could not be observed [75]. Wong et al. showed that P-REX1 expression in prostate epithelial cells could be stimulated by a HDAC inhibitor, and suggested that disassociation of HDACs from the transcription factor Sp1 on the PREX1 promoter may contribute to aberrant P-REX1 upregulation in metastatic prostate cancer [40]. We found similar results in MCF-7, BT-474, and HCC1419 breast cancer cells (a representative experiment in MCF-7 cells is shown in Figure S3 in Additional file 3). It has been reported that methylation of adjacent CpG sites in the Sp1 DNA consensus sequence can affect Sp1 binding [76]. However, we found that in breast cancer cells the luciferase activity of a PREX1 promoter reporter that includes the Sp1 sites (located in the proximal CpG island, positions -201/-192 and -170/-161) does not change after methylation (data not shown), suggesting that methylation of the Sp1 sites is not relevant for controlling the expression of the gene. At the present time, we do not know if demethylation of the PREX1 promoter is a consequence of global aberrant hypomethylation as reported in breast cancer [53] or whether it is dictated by a specific signal. We also found that P-REX1 and ER-alpha expression correlates in breast cancer and that depletion of ER-alpha in ER-positive cells reduces P-REX1 mRNA levels. As ER-alpha RNAi does not seem to significantly change the methylation status of PREX1 promoter (data not shown), it is possible that ER-alpha controls P-REX1 expression by alternative mechanisms.

Conclusions

In summary, our study established methylation as a major mechanism that dictates the differential expression of P-REX1 in breast cancer subtypes. Increased expression of P-REX1 in luminal breast cancer is associated with demethylation of CpG islands in the PREX1 promoter. The P-REX1/Rac pathway plays an important role in ErbB receptor-driven breast cancer cell motility and invasiveness, and consequently the methylation status of the PREX1 promoter could be a determinant in the progression of subsets of breast cancer patients. In addition to the prognostic implications of our findings, our results may have significant impact for cancer therapy. Indeed, the use of demethylating agents is emerging as a novel approach to cancer therapy due to their ability to reactivate the expression of tumor suppressor genes that are silenced by DNA methylation, and studies have proposed the use of AZA or related agents as anti-cancer agents for patients with solid tumors [77]-[82]. Specifically for breast cancer, demethylating agents have been shown to overcome resistance to other agents such as tamoxifen [83]-[85]. Thus, the fact that tumor-promoting and metastatic genes such as PREX1 can be reactivated by demethylating agents poses a serious therapeutic challenge, specially taking into account that PREX1 demethylation is correlated with poor prognosis.

Authors' contributions

LB-R participated in the study design, performed most of the experimental work, contributed to data analysis and interpretation, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised it. LGB participated in the study design, carried out part of the experimental work, and contributed to data analysis and interpretation. SC made substantial contribution to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, and helped to draft the manuscript. NE, SS and YT participated in the study design, contributed to data analysis and interpretation, helped to draft the manuscript, and revised it critically for intellectual content. MGK conceived and designed the study, interpreted the data, co-drafted, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: Figure S1.: ER-alpha RNAi depletion reduces P-REX1 expression. Panel A. P-REX1 mRNA expression in MCF-7 cells subject to estrogen receptor (ER)-alpha depletion, from dataset GSE27473 (***, P <0.001). Panels B. P-REX1 mRNA levels in MCF-7 (left panel) and T-47D cells (right panel) were determined after transfection with either ER-alpha or non-target control (NTC) RNAi. P-REX1 mRNA levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene B2M and expressed as relative to those in NTC-transfected cells. Similar results were observed in an additional experiment. ***, P <0.001. Inset, ER-alpha expression was determined by Western blot. (PDF 325 KB)

Additional file 2: Figure S2.: Similar PREX1 expression and methylation across HER2 subtypes. PREX1 mRNA expression (left) and promoter methylation (right) in normal tissue, HER2/ErbB2-positive and HER2/ErbB2-negative breast cancers values were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. No statistically significant differences were observed between HER2/ErbB2-positive and -negative tumors. NS, not significant. (PDF 341 KB)

Additional file 3: Figure S3.: Sp1 sites are required for transcriptional activity of the PREX1 promoter. Panel A. Luciferase activity of truncated deletions of the PREX1 promoter (cloned in a pGL3 vector) was measured in MCF-7 cells. Luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection. Data are expressed as mean ± S. D. relative to construct comprising bp -599 to bp -20. Panel B. Luciferase assay was performed upon transfection of PREX1 luciferase constructs comprising bp -204 to bp -20, either wild-type or with both Sp1 sites mutated [40]. Cells were treated either with trichostatin A (TSA) (100 ng/ml, 24 h) or vehicle. Data are expressed as mean ± S. D. relative to wild-type. Experiments were done in triplicate, and similar results were observed in three separate experiments. *** = P <0.001. (PDF 335 KB)

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH Grants CA139120 (MGK), GM093066 (NE), CA140311 (SC) and SKCCC Core Grant P30 CA006973 and DOD W81XWH-04-1-0595 (SS).

Abbreviations

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- AZA

5-aza-2-deoxycytidine

- B2M

beta-2 microglobulin

- BSP

bisulfite sequencing PCR

- ER-alpha

estrogen receptor-alpha

- GAP

GTPase-activating protein

- GEF

guanine-nucleotide exchange factor

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- ND

non detectable

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- P-REX1

phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent Rac exchanger 1

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- Rac1

Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1

- RNAi

RNA interference

- TSA

trichostatin A

- UBC

ubiquitin C

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Laura Barrio-Real, Email: lauraba@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Lorena G Benedetti, Email: lorebenedetti1@gmail.com.

Nora Engel, Email: nengel@temple.edu.

Yaping Tu, Email: YapingTu@creighton.edu.

Soonweng Cho, Email: sean.cho@jhmi.edu.

Saraswati Sukumar, Email: saras@jhmi.edu.

Marcelo G Kazanietz, Email: marcelog@upenn.edu.

References

- 1.Jaffe AB, Hall A. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossman KL, Der CJ, Sondek J. GEF means go: turning on RHO GTPases with guanine nucleotide-exchange factors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:167–180. doi: 10.1038/nrm1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wertheimer E, Gutierrez-Uzquiza A, Rosemblit C, Lopez-Haber C, Sosa MS, Kazanietz MG. Rac signaling in breast cancer: a tale of GEFs and GAPs. Cell Signal. 2012;24:353–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang SE, Shin I, Wu FY, Friedman DB, Arteaga CL. HER2/Neu (ErbB2) signaling to Rac1-Pak1 is temporally and spatially modulated by transforming growth factor beta. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9591–9600. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bustelo XR. Intratumoral stages of metastatic cells: a synthesis of ontogeny, Rho/Rac GTPases, epithelial-mesenchymal transitions, and more. Bioessays. 2012;34:748–759. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang C, Liu Y, Lemmon MA, Kazanietz MG. Essential role for Rac in heregulin beta1 mitogenic signaling: a mechanism that involves epidermal growth factor receptor and is independent of ErbB4. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:831–842. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.831-842.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schnelzer A, Prechtel D, Knaus U, Dehne K, Gerhard M, Graeff H, Harbeck N, Schmitt M, Lengyel E. Rac1 in human breast cancer: overexpression, mutation analysis, and characterization of a new isoform, Rac1b. Oncogene. 2000;19:3013–3020. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh A, Karnoub AE, Palmby TR, Lengyel E, Sondek J, Der CJ. Rac1b, a tumor associated, constitutively active Rac1 splice variant, promotes cellular transformation. Oncogene. 2004;23:9369–9380. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang SL, Lieu AS, Chang JH, Cheng TS, Cheng CY, Lee KS, Lin CL, Howng SL, Hong YR. Rac2 expression and mutation in human brain tumors. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005;147:551–554. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang C, Liu Y, Leskow FC, Weaver VM, Kazanietz MG. Rac-GAP-dependent inhibition of breast cancer cell proliferation by {beta}2-chimerin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24363–24370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411629200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krauthammer M, Kong Y, Ha BH, Evans P, Bacchiocchi A, McCusker JP, Cheng E, Davis MJ, Goh G, Choi M, Ariyan S, Narayan D, Dutton-Regester K, Capatana A, Holman EC, Bosenberg M, Sznol M, Kluger HM, Brash DE, Stern DF, Materin MA, Lo RS, Mane S, Ma S, Kidd KK, Hayward NK, Lifton RP, Schlessinger J, Boggon TJ, Halaban R. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic RAC1 mutations in melanoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1006–1014. doi: 10.1038/ng.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawazu M, Ueno T, Kontani K, Ogita Y, Ando M, Fukumura K, Yamato A, Soda M, Takeuchi K, Miki Y, Yamaguchi H, Yasuda T, Naoe T, Yamashita Y, Katada T, Choi YL, Mano H. Transforming mutations of RAC guanosine triphosphatases in human cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3029–3034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216141110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz E, Sims AH, Sproul D, Caldwell H, Dixon MJ, Meehan RR, Harrison DJ. Targeting of Rac GTPases blocks the spread of intact human breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2012;3:608–619. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minard ME, Kim LS, Price JE, Gallick GE. The role of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Tiam1 in cellular migration, invasion, adhesion and tumor progression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;84:21–32. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000018421.31632.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Zapico ME, Gonzalez-Paz NC, Weiss E, Savoy DN, Molina JR, Fonseca R, Smyrk TC, Chari ST, Urrutia R, Billadeau DD. Ectopic expression of VAV1 reveals an unexpected role in pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lane J, Martin TA, Mansel RE, Jiang WG. The expression and prognostic value of the guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) Trio, Vav1 and TIAM-1 in human breast cancer. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2008;5:23. doi: 10.1186/1477-7800-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrio-Real L, Kazanietz MG. Rho GEFs and cancer: linking gene expression and metastatic dissemination. Sci Signal. 2012;5:e43. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodis E, Watson IR, Kryukov GV, Arold ST, Imielinski M, Theurillat JP, Nickerson E, Auclair D, Li L, Place C, Dicara D, Ramos AH, Lawrence MS, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Voet D, Saksena G, Stransky N, Onofrio RC, Winckler W, Ardlie K, Wagle N, Wargo J, Chong K, Morton DL, Stemke-Hale K, Chen G, Noble M, Meyerson M, Ladbury JE, et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell. 2012;150:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook DR, Rossman KL, Der CJ. Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors: regulators of Rho GTPase activity in development and disease. Oncogene. 2013;33:4021–4035. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng M, Simon R, Mirlacher M, Maurer R, Gasser T, Forster T, Diener PA, Mihatsch MJ, Sauter G, Schraml P. TRIO amplification and abundant mRNA expression is associated with invasive tumor growth and rapid tumor cell proliferation in urinary bladder cancer. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:63–69. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63275-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Citterio C, Menacho-Marquez M, Garcia-Escudero R, Larive RM, Barreiro O, Sanchez-Madrid F, Paramio JM, Bustelo XR. The rho exchange factors vav2 and vav3 control a lung metastasis-specific transcriptional program in breast cancer cells. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra71. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenmuller T, Rydh K, Nanberg E. Role of phosphoinositide 3OH-kinase in autocrine transformation by PDGF-BB. J Cell Physiol. 2001;188:369–382. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebi H, Costa C, Faber AC, Nishtala M, Kotani H, Juric D, Della Pelle P, Song Y, Yano S, Mino-Kenudson M, Benes CH, Engelman JA. PI3K regulates MEK/ERK signaling in breast cancer via the Rac-GEF, P-Rex1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:21124–21129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314124110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sosa MS, Lopez-Haber C, Yang C, Wang H, Lemmon MA, Busillo JM, Luo J, Benovic JL, Klein-Szanto A, Yagi H, Gutkind JS, Parsons RE, Kazanietz MG. Identification of the Rac-GEF P-Rex1 as an essential mediator of ErbB signaling in breast cancer. Mol Cell. 2010;40:877–892. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montero JC, Seoane S, Ocana A, Pandiella A. P-Rex1 participates in Neuregulin-ErbB signal transduction and its expression correlates with patient outcome in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:1059–1071. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin J, Xie Y, Wang B, Hoshino M, Wolff DW, Zhao J, Scofield MA, Dowd FJ, Lin MF, Tu Y. Upregulation of PIP3-dependent Rac exchanger 1 (P-Rex1) promotes prostate cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2009;28:1853–1863. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindsay CR, Lawn S, Campbell AD, Faller WJ, Rambow F, Mort RL, Timpson P, Li A, Cammareri P, Ridgway RA, Morton JP, Doyle B, Hegarty S, Rafferty M, Murphy IG, McDermott EW, Sheahan K, Pedone K, Finn AJ, Groben PA, Thomas NE, Hao H, Carson C, Norman JC, Machesky LM, Gallagher WM, Jackson IJ, Van Kempen L, Beermann F, Der C, et al. P-Rex1 is required for efficient melanoblast migration and melanoma metastasis. Nat Commun. 2011;2:555. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ignatiadis M, Sotiriou C. Luminal breast cancer: from biology to treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:494–506. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haque R, Ahmed SA, Inzhakova G, Shi J, Avila C, Polikoff J, Bernstein L, Enger SM, Press MF. Impact of breast cancer subtypes and treatment on survival: an analysis spanning two decades. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1848–1855. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bloushtain-Qimron N, Yao J, Snyder EL, Shipitsin M, Campbell LL, Mani SA, Hu M, Chen H, Ustyansky V, Antosiewicz JE, Argani P, Halushka MK, Thomson JA, Pharoah P, Porgador A, Sukumar S, Parsons R, Richardson AL, Stampfer MR, Gelman RS, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Polyak K. Cell type-specific DNA methylation patterns in the human breast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14076–14081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805206105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baylin SB, Herman JG. DNA hypermethylation in tumorigenesis: epigenetics joins genetics. Trends Genet. 2000;16:168–174. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01971-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lo PK, Sukumar S. Epigenomics and breast cancer. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:1879–1902. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.12.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Burstin VA, Xiao L, Kazanietz MG. Bryostatin 1 inhibits phorbol ester-induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells by differentially modulating protein kinase C (PKC) delta translocation and preventing PKCdelta-mediated release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:325–332. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.064741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garg R, Blando J, Perez CJ, Wang H, Benavides FJ, Kazanietz MG. Activation of nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) in prostate cancer is mediated by protein kinase C epsilon (PKCepsilon) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:37570–37582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.398925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frommer M, McDonald LE, Millar DS, Collis CM, Watt F, Grigg GW, Molloy PL, Paul CL. A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1827–1831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neve RM, Chin K, Fridlyand J, Yeh J, Baehner FL, Fevr T, Clark L, Bayani N, Coppe JP, Tong F, Speed T, Spellman PT, DeVries S, Lapuk A, Wang NJ, Kuo WL, Stilwell JL, Pinkel D, Albertson DG, Waldman FM, McCormick F, Dickson RB, Johnson MD, Lippman M, Ethier S, Gazdar A, Gray JW. A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daemen A, Griffith OL, Heiser LM, Wang NJ, Enache OM, Sanborn Z, Pepin F, Durinck S, Korkola JE, Griffith M, Hur JS, Huh N, Chung J, Cope L, Fackler MJ, Umbricht C, Sukumar S, Seth P, Sukhatme VP, Jakkula LR, Lu Y, Mills GB, Cho RJ, Collisson EA, van't Veer LJ, Spellman PT, Gray JW. Modeling precision treatment of breast cancer. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R110. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2008, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

- 39.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong CY, Wuriyanghan H, Xie Y, Lin MF, Abel PW, Tu Y. Epigenetic regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate-dependent Rac exchanger 1 gene expression in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25813–25822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.211292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardiner-Garden M, Frommer M. CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:261–282. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;16:6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cameron EE, Bachman KE, Myohanen S, Herman JG, Baylin SB. Synergy of demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition in the re-expression of genes silenced in cancer. Nat Genet. 1999;21:103–107. doi: 10.1038/5047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campbell AD, Lawn S, McGarry LC, Welch HC, Ozanne BW, Norman JC. P-Rex1 cooperates with PDGFRbeta to drive cellular migration in 3D microenvironments. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim HW, Iwatani M, Hattori N, Tanaka S, Yagi S, Shiota K. Resistance to 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine in genic regions compared to non-genic repetitive sequences. J Reprod Dev. 2010;56:86–93. doi: 10.1262/jrd.20247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mossman D, Kim KT, Scott RJ. Demethylation by 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine in colorectal cancer cells targets genomic DNA whilst promoter CpG island methylation persists. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:366. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caan BJ, Sweeney C, Habel LA, Kwan ML, Kroenke CH, Weltzien EK, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Castillo A, Factor RE, Kushi LH, Bernard PS. Intrinsic subtypes from the PAM50 gene expression assay in a population-based breast cancer survivor cohort: Prognostication of short and long term outcomes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:725–734. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fackler MJ, Malone K, Zhang Z, Schilling E, Garrett-Mayer E, Swift-Scanlan T, Lange J, Nayar R, Davidson NE, Khan SA, Sukumar S. Quantitative multiplex methylation-specific PCR analysis doubles detection of tumor cells in breast ductal fluid. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3306–3310. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Evron E, Dooley WC, Umbricht CB, Rosenthal D, Sacchi N, Gabrielson E, Soito AB, Hung DT, Ljung B, Davidson NE, Sukumar S. Detection of breast cancer cells in ductal lavage fluid by methylation-specific PCR. Lancet. 2001;357:1335–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04501-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Esteller M, Silva JM, Dominguez G, Bonilla F, Matias-Guiu X, Lerma E, Bussaglia E, Prat J, Harkes IC, Repasky EA, Gabrielson E, Schutte M, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Promoter hypermethylation and BRCA1 inactivation in sporadic breast and ovarian tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:564–569. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.7.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garcia JM, Silva J, Pena C, Garcia V, Rodriguez R, Cruz MA, Cantos B, Provencio M, Espana P, Bonilla F. Promoter methylation of the PTEN gene is a common molecular change in breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;41:117–124. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hellebrekers DM, Griffioen AW, van Engeland M. Dual targeting of epigenetic therapy in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1775:76–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jackson K, Yu MC, Arakawa K, Fiala E, Youn B, Fiegl H, Muller-Holzner E, Widschwendter M, Ehrlich M. DNA hypomethylation is prevalent even in low-grade breast cancers. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:1225–1231. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.12.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Szyf M. DNA demethylation and cancer metastasis: therapeutic implications. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2008;3:519–531. doi: 10.1517/17460441.3.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Widschwendter M, Jiang G, Woods C, Müller HM, Fiegl H, Goebel G, Marth C, Müller-Holzner E, Zeimet AG, Laird PW, Ehrlich M. DNA hypomethylation and ovarian cancer biology. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4472–4480. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Souza CR, Leal MF, Calcagno DQ, Costa Sozinho EK, Borges Bdo N, Montenegro RC, Dos Santos AK, Dos Santos SE, Ribeiro HF, Assumpção PP, de Arruda Cardoso Smith M, Burbano RR. MYC deregulation in gastric cancer and its clinicopathological implications. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fang JY, Zhu SS, Xiao SD, Jiang SJ, Shi Y, Chen XY, Zhou XM, Qian LF. Studies on the hypomethylation of c-myc, c-Ha-ras oncogenes and histopathological changes in human gastric carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:1079–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1996.tb00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nishigaki M, Aoyagi K, Danjoh I, Fukaya M, Yanagihara K, Sakamoto H, Yoshida T, Sasaki H. Discovery of aberrant expression of R-RAS by cancer-linked DNA hypomethylation in gastric cancer using microarrays. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2115–2124. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang WF, Xie Y, Zhou ZH, Qin ZH, Wu JC, He JK. PIK3CA hypomethylation plays a key role in activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in esophageal cancer in Chinese patients. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34:1560–1567. doi: 10.1038/aps.2013.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hanada M, Delia D, Aiello A, Stadtmauer E, Reed JC. bcl-2 gene hypomethylation and high-level expression in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1993;82:1820–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duenas-Gonzalez A, Abad-Hernandez MM, Cruz-Hernandez JJ, Gonzalez-Sarmiento R. Analysis of bcl-2 in sporadic breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;80:2100–2108. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19971201)80:11<2100::AID-CNCR9>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stefanska B, Huang J, Bhattacharyya B, Suderman M, Hallett M, Han ZG, Szyf M. Definition of the landscape of promoter DNA hypomethylation in liver cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5891–5903. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marzese DM, Scolyer RA, Huynh JL, Huang SK, Hirose H, Chong KK, Kiyohara E, Wang J, Kawas NP, Donovan NC, Hata K, Wilmott JS, Murali R, Buckland ME, Shivalingam B, Thompson JF, Morton DL, Kelly DF, Hoon DS. Epigenome-wide DNA methylation landscape of melanoma progression to brain metastasis reveals aberrations on homeobox D cluster associated with prognosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:226–238. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zouridis H, Deng N, Ivanova T, Zhu Y, Wong B, Huang D, Wu YH, Wu Y, Tan IB, Liem N, Gopalakrishnan V, Luo Q, Wu J, Lee M, Yong WP, Goh LK, Teh BT, Rozen S, Tan P. Methylation subtypes and large-scale epigenetic alterations in gastric cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:156ra140. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ehrlich M, Lacey M. DNA hypomethylation and hemimethylation in cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;754:31–56. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9967-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wild L, Flanagan JM. Genome-wide hypomethylation in cancer may be a passive consequence of transformation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1806:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hou P, Liu D, Dong J, Xing M. The BRAF(V600E) causes widespread alterations in gene methylation in the genome of melanoma cells. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:286–295. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.2.18707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang YJ, Wu HC, Yazici H, Yu MW, Lee PH, Santella RM. Global hypomethylation in hepatocellular carcinoma and its relationship to aflatoxin B(1) exposure. World J Hepatol. 2012;4:169–175. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i5.169.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kamiyama H, Suzuki K, Maeda T, Koizumi K, Miyaki Y, Okada S, Kawamura YJ, Samuelsson JK, Alonso S, Konishi F, Perucho M. DNA demethylation in normal colon tissue predicts predisposition to multiple cancers. Oncogene. 2012;31:5029–5037. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rodríguez-Rodero S, Fernández AF, Fernández-Morera JL, Castro-Santos P, Bayon GF, Ferrero C, Urdinguio RG, Gonzalez-Marquez R, Suarez C, Fernández-Vega I, Fresno Forcelledo MF, Martínez-Camblor P, Mancikova V, Castelblanco E, Perez M, Marrón PI, Mendiola M, Hardisson D, Santisteban P, Riesco-Eizaguirre G, Matías-Guiu X, Carnero A, Robledo M, Delgado-Álvarez E, Menéndez-Torre E, Fraga MF. DNA methylation signatures identify biologically distinct thyroid cancer subtypes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2811–2821. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salhia B, Kiefer J, Ross JT, Metapally R, Martinez RA, Johnson KN, Diperna DM, Paquette KM, Jung S, Nasser S, Wallstrom G, Tembe W, Baker A, Carpten J, Resau J, Ryken T, Sibenaller Z, Petricoin EF, Liotta LA, Ramanathan RK, Berens ME, Tran NL. Integrated genomic and epigenomic analysis of breast cancer brain metastasis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo Y, Pakneshan P, Gladu J, Slack A, Szyf M, Rabbani SA. Regulation of DNA methylation in human breast cancer. Effect on the urokinase-type plasminogen activator gene production and tumor invasion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41571–41579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pakneshan P, Xing RH, Rabbani SA. Methylation status of uPA promoter as a molecular mechanism regulating prostate cancer invasion and growth in vitro and in vivo. FASEB J. 2003;17:1081–1088. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0973com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shukeir N, Pakneshan P, Chen G, Szyf M, Rabbani SA. Alteration of the methylation status of tumor-promoting genes decreases prostate cancer cell invasiveness and tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9202–9210. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jin H, Li T, Ding Y, Deng Y, Zhang W, Yang H, Zhou J, Liu C, Lin J. Methylation status of T-lymphoma invasion and metastasis 1 promoter and its overexpression in colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:541–551. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhu WG, Srinivasan K, Dai Z, Duan W, Druhan LJ, Ding H, Yee L, Villalona-Calero MA, Plass C, Otterson GA. Methylation of adjacent CpG sites affects Sp1/Sp3 binding and activity in the p21(Cip1) promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4056–4065. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4056-4065.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sigalotti L, Fratta E, Coral S, Maio M. Epigenetic drugs as immunomodulators for combination therapies in solid tumors. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;142:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Candelaria M, Gallardo-Rincón D, Arce C, Cetina L, Aguilar-Ponce JL, Arrieta O, González-Fierro A, Chávez-Blanco A, de la Cruz-Hernández E, Camargo MF, Trejo-Becerril C, Pérez-Cárdenas E, Pérez-Plasencia C, Taja-Chayeb L, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Revilla-Vazquez A, Dueñas-González A. A phase II study of epigenetic therapy with hydralazine and magnesium valproate to overcome chemotherapy resistance in refractory solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1529–1538. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Appleton K, Mackay HJ, Judson I, Plumb JA, McCormick C, Strathdee G, Lee C, Barrett S, Reade S, Jadayel D, Tang A, Bellenger K, Mackay L, Setanoians A, Schätzlein A, Twelves C, Kaye SB, Brown R. Phase I and pharmacodynamic trial of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor decitabine and carboplatin in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4603–4609. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stathis A, Hotte SJ, Chen EX, Hirte HW, Oza AM, Moretto P, Webster S, Laughlin A, Stayner LA, McGill S, Wang L, Zhang WJ, Espinoza-Delgado I, Holleran JL, Egorin MJ, Siu LL. Phase I study of decitabine in combination with vorinostat in patients with advanced solid tumors and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1582–1590. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.George RE, Lahti JM, Adamson PC, Zhu K, Finkelstein D, Ingle AM, Reid JM, Krailo M, Neuberg D, Blaney SM, Diller L. Phase I study of decitabine with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide in children with neuroblastoma and other solid tumors: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55:629–638. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Plummer R, Vidal L, Griffin M, Lesley M, de Bono J, Coulthard S, Sludden J, Siu LL, Chen EX, Oza AM, Reid GK, McLeod AR, Besterman JM, Lee C, Judson I, Calvert H, Boddy AV. Phase I study of MG98, an oligonucleotide antisense inhibitor of human DNA methyltransferase 1, given as a 7-day infusion in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3177–3183. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sharma D, Saxena NK, Davidson NE, Vertino PM. Restoration of tamoxifen sensitivity in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer cells: tamoxifen-bound reactivated ER recruits distinctive corepressor complexes. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6370–6378. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pitta CA, Papageorgis P, Charalambous C, Constantinou AI. Reversal of ER-beta silencing by chromatin modifying agents overrides acquired tamoxifen resistance. Cancer Lett. 2013;337:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Altundag O, Altundag K, Gunduz M. DNA methylation inhibitor, procainamide, may decrease the tamoxifen resistance by inducing overexpression of the estrogen receptor beta in breast cancer patients. Med Hypotheses. 2004;63:684–687. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1.: ER-alpha RNAi depletion reduces P-REX1 expression. Panel A. P-REX1 mRNA expression in MCF-7 cells subject to estrogen receptor (ER)-alpha depletion, from dataset GSE27473 (***, P <0.001). Panels B. P-REX1 mRNA levels in MCF-7 (left panel) and T-47D cells (right panel) were determined after transfection with either ER-alpha or non-target control (NTC) RNAi. P-REX1 mRNA levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene B2M and expressed as relative to those in NTC-transfected cells. Similar results were observed in an additional experiment. ***, P <0.001. Inset, ER-alpha expression was determined by Western blot. (PDF 325 KB)

Additional file 2: Figure S2.: Similar PREX1 expression and methylation across HER2 subtypes. PREX1 mRNA expression (left) and promoter methylation (right) in normal tissue, HER2/ErbB2-positive and HER2/ErbB2-negative breast cancers values were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. No statistically significant differences were observed between HER2/ErbB2-positive and -negative tumors. NS, not significant. (PDF 341 KB)

Additional file 3: Figure S3.: Sp1 sites are required for transcriptional activity of the PREX1 promoter. Panel A. Luciferase activity of truncated deletions of the PREX1 promoter (cloned in a pGL3 vector) was measured in MCF-7 cells. Luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection. Data are expressed as mean ± S. D. relative to construct comprising bp -599 to bp -20. Panel B. Luciferase assay was performed upon transfection of PREX1 luciferase constructs comprising bp -204 to bp -20, either wild-type or with both Sp1 sites mutated [40]. Cells were treated either with trichostatin A (TSA) (100 ng/ml, 24 h) or vehicle. Data are expressed as mean ± S. D. relative to wild-type. Experiments were done in triplicate, and similar results were observed in three separate experiments. *** = P <0.001. (PDF 335 KB)