Abstract

Are individuals bounding work and family the way they would like? Much of the work-family boundary literature focuses on whether employees are segmenting or integrating work with family, but does not explore the boundaries workers would like to have, nor does it examine the fit between desired and enacted boundaries, or assess boundary stability. In this study, 23 respondents employed at a large Fortune 500 company were interviewed about their work-family boundaries before and after their teams underwent a cultural change initiative that sought to loosen workplace norms and allow employees more autonomy to decide when and where they performed their job tasks. Four distinct boundary strategies emerged from the data, with men and parents of young children having better alignment between preferred and enacted boundaries than women and those without these caregiving duties. Implications for boundary theory and research are discussed.

Keywords: Boundary management, Boundary Theory, Work and family, Work-family interface

Introduction

Over the last several decades in the United States, work and family domains have undergone significant change. Separate spheres ideology that was put firmly in place during the Industrial revolution (Gutman 1988), where employment took place outside the home, and home was a “safe haven” from the demands of work, has been eroding at a fast pace. Globalization, declines in manufacturing and rising service sector employment, growth of nonstandard schedules, and technological developments (such as cell phones, wireless internet, and laptops) have made it easier for work to intrude on family and home life. Likewise, women, especially mothers of young children, are in the labor market in increasing numbers (Cohany & Sok, 2007), and while men are gradually doing more, women still do the majority of childcare and homemaking tasks (Bianchi, Milkie, Sayer & Robinson, 2000). As such, work and home domains can become increasingly blurred.

Investigating how work, family, and personal life1 come together is a thriving area of study. Scholars commonly examine how work and family realms conflict or enhance one another, or whether or not individuals feel balanced between their multiple roles (see Bellavia & Frone, 2005; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Although useful for understanding how individuals feel about their work-family intersection, these concepts do not reveal how people interpret the expectations and responsibilities in each domain. For example, when assessing conflict or spillover, scholars assume that any intrusion from one domain to another is grounds for potential problems. However, individuals may not agree on what constitutes an intrusion or could feel that some intrusions are more problematic than others: the same set of objective work-family demands and responsibilities may be viewed differently and result in different appraisals. To understand how individuals subjectively perceive family, work and personal domains, the boundary work or “boundary management” literature fits best. According to this scholarship, individuals set boundaries between work and home that fall along a continuum ranging from segmentation (where work and family are kept firmly segregated) to integration (where work and family are entirely blended) (Nippert-Eng, 1996). While there is a growing body of research that fleshes out the boundary strategies or styles that individuals have (Bulger, Mathews & Hoffman, 2007; Kossek & Lautsch, 2008; Kossek, Ruderman & Hannum, 2012), less is known about the degree of alignment between preferred boundaries and actual boundaries, and whether or not boundaries are stable over time. This study begins to address these gaps. Specifically, I use data from two teams of workers employed within a large Fortune 500 company that was undergoing an internal cultural change initiative. I tracked the work-family boundaries that workers desired and created before and after the change in workplace norms, whether or not desired and actual boundaries aligned, and if boundaries and boundary fit altered when workplace norms changed.

Literature Review

Nippert-Eng's (1996) Home and Work: Negotiating Boundaries in Everyday Life is considered a foundational conceptual work in understanding how work and life are cognitively bounded using external and internal markers. She found that work-family boundaries come in four different forms (cognitive, physical, temporal, and behavioral) that combine to create “personal realm configurations” (6) that can be arranged along the segmentation to integration continuum (Nippert-Eng 1996). In its purest form segmentation is the complete physical, behavioral, mental and temporal separation of home and work roles (i.e. never the two shall meet), such that home and work are not only physically separate but all objects, people, and thoughts associated with one domain do not carry over into another. At the opposite end of the continuum is integration, which is the complete blurring of home and work roles and domains. While it is theoretically possible for individuals to fall at either extreme end of the continuum, in actuality most men and women fall someone in-between due to structural constraints and expectations associated with each domain (Nippert-Eng 1996: 6). Although boundary theorists argue that boundaries are constantly being formed and shaped by respodents and their social environment (Ashforth, Kreiner & Fugate, 2000; Nippert-Eng, 1996), there is some evidence that work-family boundaries are relatively durable and not subject to much change. In their longitudinal study of Canadian employees, Hecht and Allen (2009) found that enacted boundaries were relatively stable at two time points measured over the course of a year.

Recently, scholars have begun to theoretically and empirically unpack the continuum, with many different labels attached to the configurations in the middle are a mix of segmentation and integration (Bulger, et al, 2007; Kossek & Lautsch, 2008; Kossek, et al., 2012). Much like the work-family conflict literature, where it is common to assess directionality (Bellavia & Frone, 2005), boundary scholars have grown increasingly sensitivity to whether or not individuals integrate or segment from work-to-family and family-to-work (Ashforth et al., 2000; Kossek & Lautsch, 2008; Kossek, et al., 2012).

Boundary scholars (Ashforth et al., 2000; Kossek, Lautsch & Eaton, 2005; Kreiner, 2006; Kossek, Noe & DeMarr, 1999; Nippert-Eng 1996) are also careful to conceptually distinguish between desired and actual boundaries. While cognitive, physical, behavioral and temporal elements meld together to comprise both forms of boundaries, “enacted boundaries” are the actual demarcations that individuals create or have between core life domains, while “boundary preferences” are the boundaries they desire. However, little empirical attention has been devoted to separating preferences from enactments.2 Some researchers (Kossek et al., 2005; Kossek & Lautsch, 2008) argue for an intertwined approach where preferred boundaries form an integral component of enacted boundaries. Ammons (2008) urges a slightly different perspective, and proposes that boundary preferences and enactments are distinct and inter-related concepts and that it is their intersection, alignment, or “boundary fit” that drives outcomes such as work-family conflict and work-family balance.

As social constructions, boundaries are shaped by individual needs and desires, but they occur within a constantly changing society and are shaped by cultural and institutional arrangements and practices (Mills, 1959; Moen & Chermack, 2005). Thus, they may or may not be consciously created by individuals. Structural conditions and norms present in the home and workplace influence both enacted and preferred boundaries by offering possibilities, constraints and/or resources; as such, these conditions can either enhance or exacerbate perceptions of boundary alignment. Likewise, when surrounding influences are altered, it can cause individuals to reassess work-family boundaries and boundary possibilities. As Nippert-Eng (1996) wrote: “Changes invoke new, modified understandings of what home and work mean. They may also change the available ways in which we carry out these understandings” (p. 15).

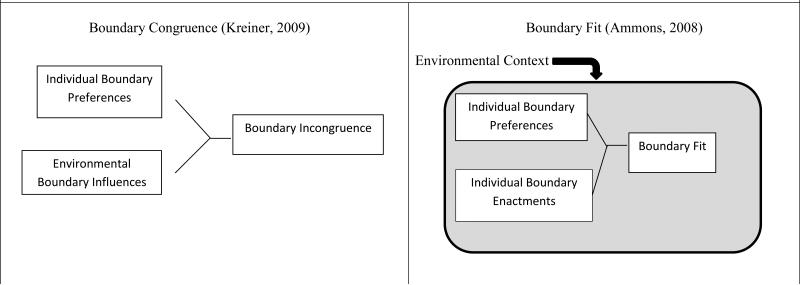

A boundary fit approach diverges from the growing body of boundary research which adopts a person-environment fit perspective and examines alignment between individual boundary preferences and the boundaries supported in the external environment or workplace context (see Figure 1). In the person-environment approach, scholars find that when available environmental conditions, or workplace policies and practices, align with boundary preferences, it results in “boundary congruence” (Kreiner, 2009) which bolsters mental health (Edwards & Rothbard, 1999), reduces work-family conflict (Chen, Powell & Greenhaus, 2009) and results in higher levels of job satisfaction and commitment (Rothbard, Phillips & Dumas, 2005).

Figure 1.

Boundary Fit versus Boundary Congruence

Boundary work remains a promising and relatively unchartered area of study. There are several theoretical works that examine boundary preferences, enactments, environmental conditions, and how they are intertwined (Kossek et al., 2005; Kossek & Lautsch, 2012) but few empirical pieces test these models. Also lacking, are studies that examine the stability of boundary preferences and enactments (for exception, see Hecht & Allen, 2009). What is thriving are studies that examine outcomes associated with boundaries (Bulger et al, 2007; Chen, et al., 2009; Kossek et al., 2012; Kreiner, 2006; Park, Fritz & Jex, 2011; Rothbard et al., 2005). However, additional work remains to be done in each of these areas.

This paper adds two contributions to the boundary work literature. First, it treats boundary preferences and boundary enactments as distinct concepts and assesses boundary fit. Second, it evaluates the durability of boundaries when the norms around a core domain, work, are altered, and individuals are given more control over their work-related boundaries. Studying the longitudinal stability of enacted and preferred boundaries in a time of flux allows us to see how stable boundaries are, and provides insight into how easy it is to change them. My results indicate that boundary work scholars should continue to move beyond discussions of whether or not an individual is a “segmenter” an “integrator” and should instead focus on what patterns of boundary work mean in the context of respondents’ lives. I found that some individuals craft boundaries to protect family, others create boundaries to privilege employment, and that only a few had fluidity between work and family or personal realms. Preferences were also distinct from enactments. And, while boundaries may appear stable, they were always works in progress, and some individuals had less fluctuation than others. Men and respondents with young children living in the household had the most stable boundaries and the best boundary fit.

Method

To understand work-family boundary strategies and their stability, longitudinal data were gathered from two teams of workers (N=23) employed at the Midwestern headquarters of a large Fortune 500 company called Streamline (pseudonym). At this location, a unique organizational initiative was unfolding internally that was well-suited to investigating work-family boundaries. The “focus on results for an effective (work) environment” or “FREE” initiative (also a pseudonym) was a voluntary program developed in-house that encouraged employees to work “whenever, wherever, as long as their work got done.” The data reported here comes from the Flexible Work and Well-being Project, which is a multi-method study of how FREE influences the work-family interface, turnover and health outcomes of Streamline workers.

Between November 2005 and August 2006, 23 individuals from two teams were observed for nine months as they were shifting to a FREE work environment. Interviews lasted one to two hours and were conducted before FREE and 2-3 months after the workers had transitioned. The interview material used for this study references questions about workers’ family, hobbies, job demands, preferred and enacted boundaries, and the salience of work, and personal/family life. Photographs of work cubicles and home work spaces were also gathered and respondents were asked to explain the photographic content during the second interview.

All respondents were white and either professionals or white collar workers, and most had college degrees. Eight respondents had supervisory responsibilities. There were roughly equal numbers of men and women, but age and life stage varied (nine respondents were single; eight were married with at least one child under age 6, and six were married or cohabiting and had either no children, school-aged children, or grown children living outside their home). No respondents were divorced or single parents, and no one openly identified as LGBT.

To understand respondents preferred and enacted boundaries, I used a grounded theoretical approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). I entered interview transcripts into Atlas.ti (a qualitative computer software program) and read all documents several times. Since all interviews were semi-structured, I open coded them using a mixture of line-by-line, in-vivo, and structured coding techniques.3 Next, I used axial coding to help me discern relationships between and amongst the conceptual categories that had emerged during initial coding. This phase of coding led me to consider directionality of boundaries and the purpose of certain boundary configurations. At each stage of the coding, I used a constant comparative process to discern what strategies were occurring amongst respondents, and how boundary elements were intersecting within a respondent at a particular time period and between time points. Through this process, reoccurring categories emerged and were woven together to generate the findings.

Results

Most respondents’ enacted and preferred boundaries fell between the polar ends of segmentation and integration. Their physical, temporal, cognitive, and behavioral boundaries revealed a mishmash of segmentation and integration, however, no respondent bounded or desired to bound work from life in the same exact manner. The binary terms “integrator” and “segmenter” were ill-fitting labels that did not help me sort out nuances in the vast middle of the continuum. Instead, cognitive frameworks for managing work and life rose to importance, as did directionality. This lead to a shift away from who segments, who integrates, how much of each they do, and how much of each they would like to do, and instead focused the analysis on the purpose and meaning of boundaries. What emerged were four ideal types which represent ways of thinking about the work-life intersection and reflect segmentation and integration tendencies, directionality, and the reason for this strategy (see Table 1): 1) protecting family, 2) above and beyond, 3) enhancing family, and 4) holistic. Although some strategies were more widely desired and enacted than others and there were demarcations by gender and parental status, there were surprisingly few misalignments between preferred and enacted boundaries at either time point.

Table 1.

Boundary Strategies

| Family-to-Work Integration | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Work-to-Family Integration | Yes | Holistic | Above & Beyond |

| No | Enhance Family | Protect family | |

A “protecting family” strategy keeps work and family domains separated, and is located closest to the segmentation end of the continuum (Nippert-Eng, 1996). The second and third work-family boundary strategies fall in the middle of the continuum. “Above and beyond” allows work in life domains but keeps family/personal contained, while an “enhance family” strategy lets family/personal into the work domain but keeps work contained. Lastly, a “holistic” boundary strategy has fluid work and life domains and few, if any, boundaries separating them. This would be closest to integration. After briefly discussing each boundary strategy, I discuss stability and alignments between preferred and enacted boundaries.

Never the Two Shall Meet : Protecting Family

The most prevalent boundary strategy was “protecting family,” with 14 respondents enacting this strategy and 15 desiring it. This strategy comes closest to “segmentation:” respondents largely kept work and family apart. It was most commonly found amongst single respondents. Respondents with the protecting family boundary strategy either equally valued their family/personal lives and job but felt they were incompatible to some extent (requiring different presentation of self, role demands, or that domains were fundamentally at odds in terms of time or location), or they valued their personal and home life more than work and did not feel comfortable bringing it (in the form of items, thoughts, or actions) into the office.

As with the other strategies, there was within-category variation, but overall protecting family entailed working at the office, taking few personal breaks, and leaving all work-related thoughts and items firmly within the bounds of the company at the end of each workday and workweek. By approaching their work in this way, they did not dwell on work after hours or physically take it home with them. As Denise explained, “I like to be here and do my work and when I leave I feel like I can leave it here and not have it hang over my head all the time.”

Above and Beyond

The second most common strategy was integrating work into family/personal with little to no integration of life into the work domain. I termed this boundary strategy “above and beyond.” Twelve respondents enacted above and beyond at some point, and eight desired these boundaries. All had diverse work demands; there were some supervisors, direct reports, workers with daily and weekly deadlines to meet, as well as project-based workers. It was how respondents reacted to these demands and thought about their work though, that set them apart from other respondents. Above and beyond manifested in two ways, eager and reluctant.

Eager Above and Beyonders

Respondents with an eager above and beyond boundary style were heavily invested in work, thoroughly enjoyed it and did not resent or have mixed feelings that it crept into their personal life. But, they had very little integration of personal or family into their workdays. The respondents that pursued or wished to pursue this strategy come closest to what Williams (2000) terms “the ideal worker” (c.f. Bailyn, 1993). They either had few family or personal responsibilities, or if they did then other people in their lives attend to them (such as spouses, significant others, or other family members). And, they prioritized work ahead of all other involvements, putting in long workdays and workweeks. In alignment with gendered ideal worker expectations, more men than women either pursued or desired this boundary strategy.

The passion eager above and beyonders had for their work drove their temporal, physical, cognitive and behavioral boundaries. All worked long days with few breaks, physically took work home nights and weekends, and continued to think about work long after the official workday and workweek had ended. They thought they were the same person at work and at home, but varied on how much of their personal life they typically shared with coworkers, how much they socialized after hours with coworkers, and in cubicle personalization.

Eager above and beyonders were so focused on work that they tended to forget about other personal commitments, personal needs or that life existed outside of work. When asked if they thought about family or personal matters during the workday or if they fit in personal errands or tasks, I received the following illustrative replies from Oliver, Darren, and Belinda (all were married with young children):

I've never been late on bills before, but now I'm late on bills because I don't get to things like that. You know, I'm just so focused on this job. (Oliver).

Um, for the most part I am very much work focused. So, I have the personal tendency to probably get more lost in it. I can lose track of the outside world in general through a workweek, which probably isn't the best thing to say but that's what happens.... The best way of describing it is I have very little understanding of what's happening in the world aside from what's happening within our specific business and our vendors. So, I can tell you [mentions names of specific vendors] or whatnot, but if you ask me what's happening like politically or whatnot, I don't know. I may grab the sports stuff if I have time and then I try to keep track on the TV shows that I'm interested in, but if you actually, talk about the connection with what's actually going on in the world, it's just not there. (Darren).

Honestly, I need to figure out... I've never been so late before. I need to figure out when I'm going to get to Target to get my kids something for their Easter basket. It's bad... I should probably break more, but I just don't like getting out of that rhythm. (Belinda).

While the nature of their job encouraged this level of embeddedness (they had workdays filled with meetings, customers in different time zones, and urgent business situations that sometimes needed resolution outside standard hours), eager above and beyonders recognized that although the job prompted them to be readily available and work around the clock, they knew that if they wanted to they could work differently. As Darren explained to me:

Um, I definitely do insert the job into my life a little bit more than... other people may want to, or consider healthy. So, it's just a kind of more of a personal thing. But, I don't think it's anything that the job necessarily, absolutely requires.

Respondents are aware that there is a cost they incur and that they might not be able to sustain this strategy for very long. Some discussed the toll it exacted on themselves, telling me that they wished they took more time for themselves and worked out more. Others related the strain it put on their family relationships. No eager above and beyonder respondent wanted to work that way indefinitely.

Reluctantly Going Above and Beyond

In contrast to those who eagerly sought to integrate work into their family/personal lives,reluctant above and beyonders were ambivalent, resentful and/or wary about integrating. One set of traits often shared by this group was mastery over their jobs, a desire for more challenging work, and concern about job stability. Going “above and beyond” a little had its benefits. By “sticking around” the office or working additional hours at home, these respondents had the outward appearance of being “ideal” employees and it made them stand out from their coworkers, gave them greater recognition that could lead to a promotion and safeguarded them from fears that they would be let-go if a round of layoffs rippled through the company.

Unlike eager above and beyonders, those with this boundary strategy regarded work as a default option. Five respondents had this boundary strategy at some point during the study, but only two respondents preferred this strategy. All were married/partnered, or spent a great deal of time with other family members and wished they could spend more time with them, but were unable to due to scheduling conflicts or distance. To fill some of the downtime in their evenings and weekends, respondents worked. Dwight and Dale (each married with no children) are great examples of this strategy. Dwight's wife worked every Saturday and often returned home late in the evening, leaving him home alone for several hours. When asked if he ever took work home, he replied “No, not really. Maybe I'll check email just because I'll be bored at home and I'll be like ‘yeah, I'll check some email!’” Likewise, Dale linked his reluctance to take time off to his undemanding family and personal life. When I asked him why he preferred this, he told me:

Might as well come to work (laughs). With people that have kids, I'm sure it'd be a totally different answer. You know, they'd be able to spend time with their kids on those days off. But, for us, everyone we know is at work. So, I can have a day off, but... if I don't have anything to do at home or any projects or anything like that...Might as well come to work.

With reluctant above and beyonders, it was clear that they adored their loved ones and wished they could spend more time with them. Since they could not, they opted instead to spend their time around close coworkers and reluctantly stayed later, worked additional hours, did not use vacation time, or thought about work more than they otherwise would have.

Enhancing Family

Other respondents had the reverse boundary pattern of above and beyonders. They kept work from infringing into their personal lives, and integrated family/personal into their workday. By fitting in errands and other “low value” routine family or personal tasks during the workday, they had more time, and better quality time, for rewarding tasks and loved ones. The enhancing family strategy was prevalent among women with young children, with four respondents enacting it and four desiring it. All had demanding home or personal lives and viewed work as less important than loved ones or hobbies. As one respondent told me “I'm a very dedicated worker, but my family comes first” (Amber, married with young children).

There was a slight variation in how women used the particular boundary strategy. Amber, Emily and Denise often worked from home several days a week. During these days, they fit in personal and family activities, and floated between work-related tasks and family/personal tasks. The remaining days, they came into Streamline to work, were very focused on their job, and did not integrate family/personal much at all. Gail, by contrast, did the vast majority of her work at Streamline Monday through Friday and adhered to more traditional start and end times. She integrated personal errands and tasks throughout her workdays at the company (going to the hair salon, running to Target to buy a birthday cake, getting a manicure, buying tickets or otherwise arranging weekend family outings, etc.), and often thought about her family while she was working. For her, work was a way to have “Gail time.” When I asked her ideal work schedule would be, she told me:

I like this [my current way] because I do like being in the office and because that's my time away from the kids. And I can get a LOT of work done but it's my social time. And, now [with FREE] it's my free time. I can actually feel like I can take care of myself. I can balance everything.

Integrating family was critical to Gail because she had very little time when she arrived home:

We don't get home until like 6:30 to 7:00pm. So, it is dinner, [my children] play or take baths and I try and get them to bed. So, that's pretty much 9:30 to 10pm and then I'm tired and I'm lucky if I wash my face (laughs). And, I've got a dog. I have to feed her, and the bird. So, I've got to feed her and give her time. Yeah, so there's no time to do anything else.

Occasionally, Gail also worked from home. On these days, she would fit in work while attending to her children's needs, much like Amber.

Whether they worked at home or at the company, all of the respondents with this strategy found ways to integrate family and personal into the standard workday and they said that this made a huge difference in their lives. The danger of enhancing family is that it blatantly conflicts with the ideal worker norm (Williams, 2000; Bailyn 1993). All of the women were conscious of this, and tried very hard to make sure their coworkers knew they were doing their jobs well.

Holistic Boundaries

In the holistic strategy, work and life domains are experienced as one synergistic whole in terms of thoughts, use of space, behavior and use of time. Among respondents, this was the rarest boundary strategies. Two respondents desired it, and only one respondent, Juliet (single with no children), had holistic enacted boundaries. Respondents who desired or enacted this strategy had obligations that were more within their control. They had active personal lives, but not extensive family responsibilities (single with no children). And, they also had a strong desire to advance at work and wanted to move upward into positions that they found intrinsically rewarding. Holistic respondents sought to lead a balanced life where work and family constantly intermingled, but were also carefully orchestrated so that they did not conflict.

While there was definite structure to Juliet's workday, there was also a great deal of fluidity. She talked with family and friends during the day, took breaks, fit in work-outs at the company gym, and had some leeway in deciding when to start and end her workday at the office. She also brought family and friends to the office to visit occasionally, and took work home in the evenings and on weekends. Whether or not she actually did the work was left for her to decide. She integrated life into her time at the company, and felt it is only fair that work was integrated into her personal time. In her interactions with coworkers, Juliet was very open and often talked about her personal life with others. When asked if she felt like two people at home and work, she replied: “I'm pretty against that.... I think that you should just be yourself and authentic.” Juliet's strategy of having work and family/personal inter-mingle was readily apparent in her physical boundaries. Her cubical at Streamline had personal objects scattered amongst work-related items4 and her tendency to blend physical boundaries was also apparent in her at-home work locations which varied between her patio, dining room table, living room couch, and the small home office area located in the basement near her washer and dryer.

In some ways, the holistic strategy of managing work and family boundaries is a highly desired state for both employers and employees. The respondent who exhibited this strategy was invested in her job and carried work home with her (either physically or in her thoughts) at the end of the day and workweek. Her time spent “working” was potentially never-ending but since her personal life was intermingled, she attended to it throughout the day as well, and did not feel that her work was monopolizing her time.

Boundary Stability & Alignment between Preferred and Enacted Boundaries

Prior to FREE, squeezing in family or personal activities during the day was discouraged and workers were often recognized and praised for working long hours (see Kelly, Ammons, Chermack & Moen, 2010); thus, segmentation or work-to-family integration were favored at Streamline. When respondents were given more control to decide when and where to do their work though, all boundary strategies became acceptable as long as workers got their job done. Once under FREE, only one respondent's boundaries did not change at all. But, instead of large scale shifts, what often occurred were subtle changes among one or more boundary components, particularly temporal and physical boundaries.

There was remarkable stability in boundary preferences and enactments during the study. Most respondents had a good boundary fit at either time point (see Table 2). Less than half either desired or made a boundary strategy change. However, some groups exhibited more stability than others. Women and those without young children in their household were each more likely to make a boundary strategy change or desire to make a switch than were men or respondents with young children living in the household. At time 1, women had worse boundary fit than men, as did those without young children, but the fit of both groups improved at time 2. Preferences were not very stable from time 1 to time 2 (30% had a change) and neither were enacted boundaries (35% made a switch); but, men had more stable preferences and enacted boundaries than women, as did those with young children. Thus, loosening the normative boundaries around work did not lead to change across the board.

Table 2.

Boundary Stability and Fit by Gender and Parental Status

| Desired or Made a Change | Time 1 Boundary Fit | Time 2 Boundary Fit | Preferred Boundary Stability | Enacted Boundary Stability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All respondents (N=23) | 9 (39%) | 20 (87%) | 21 (91%) | 16 (70%) | 15 (65%) |

| Men (n=12) | 3 (25%) | 11 (92%) | 11 (92%) | 9 (75%) | 10 (83%) |

| Women (n=11) | 6 (55%) | 9 (82%) | 10 (91%) | 7 (54%) | 5 (45%) |

| No young children in household (n=15) | 8 (53%) | 12 (80%) | 13 (87%) | 9 (60%) | 8 (53%) |

| Young children in household (n=8) | 1 (13%) | 8 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 7 (88%) | 7 (88%) |

Moreover, the nature and timing of boundary changes was quite messy. When normative constraints in the workplace were eased, four respondents bounded work from encroaching on family/personal life, but they still kept family out of work; two integrated family/personal into work but continued to segment work away; and three wanted and/or allowed work to encroach but still kept family out of the work realm.

Likewise, the timing of boundary changes was also not straightforward. Of the nine respondents who made a change, only two corrected a poor boundary fit at time 1 and were able to realize their preferences. Lucy and Charity were both reluctant above and beyonders but wished to have less encroachment of work into their personal lives. Under FREE, they both adopted a protect family strategy. For the rest of those who changed, FREE led to unexpected new strategies. Two respondents had a good boundary fit at time 1, but by time 2 the new workplace norms caused their enacted boundaries to morph into something they did not desire, or they began to question their boundary preferences under FREE but had not taken steps to enact their new desires. Thus, FREE actually lead to boundary misalignments. For example, Carl had a preferred an eager above and beyonder strategy at time 1, but at time 2 desired to have a protect family strategy. Others (n=4) had alignment between their preferred and enacted strategies at time 1 and time 2, but along the way they completely switched boundary styles. For example, Denise both desired and had a protect family strategy at time 1, but at time 2 she altered her desired and enacted boundaries to enhance family. Perhaps the best example though, of how convoluted boundary change can be was Doug. At time 1, he had a protect family strategy and desired to be holistic. By the end of the study he was an eager above and beyonder and was happy with that strategy.

Although less than half of the sample altered their boundary strategies, there were slight fluctuations in preferred and enacted boundary components from respondent to respondent during the course of the study. While they were not large or significant enough to warrant a new boundary classification, these modifications indicate that boundaries were always a work in progress. Before FREE, respondents had already had some control over their behavioral boundaries (e.g. they decided how much of their personal lives they shared with coworkers and whether or not they wanted to be the same person at home as they were at work)5, so I found little to no change among my respondents along this dimension. Instead, alterations in boundaries usually happened either temporally and/or physically, and these changes cascaded and affected cognitive boundaries as well.

The most common component change was temporal. Roughly half of the respondents regularly altered when they started and/or ended their workday, and an additional three respondents did so occasionally.6 However, physical boundaries also frequently changed. One third of the respondents regularly worked from home a full or partial day at least once every other week, while another fourth worked from home on an inconsistent basis.7 And, since the workday was no longer rigidly bound by cultural norms that dictated where and when people should work and so many respondents made temporal and/or physical changes, the cognitive markers and cues that signaled where work began and ended had to be reconsidered or revised. At time 2, all respondents either said that they had become more focused when they were working at Streamline, or that they had always been focused. For three respondents, this cognitive change was unsettling and they found themselves dwelling more on work-related matters long after their workday officially ended. But, two respondents also reported that under FREE they were able to bind work-related thoughts better; they preferred cognitive segmentation and were able to create cognitive boundaries that better suited them.

By the end of the study, almost all respondents had gradually incorporated family/personal into workday to some degree, whether it was leaving work “early” on occasion, working from home, or fitting in working out or a personal errand during the standard workday. Ron (married with young children) is a good illustration of respondents who made a temporal change to their work and family boundaries but maintained the same overall strategy for managing work and family/personal.

In the following passage, Ron speaks about the temporal change he made to his work routine. At the beginning of the study, he had an enacted boundary strategy of protecting family. He regularly worked from 8 to 5:30-6pm Monday through Friday and he wanted to take a couple afternoons off during the week to do personal activities/hobbies (golf), and make-up the hours on the weekend at home. During our second interview, he left work “early” some afternoons but not every week. Although his temporal boundaries had not shifted as much as he desired, the change Ron made was important to his family and made him feel better adjusted at work:

I used to come home at 6pm and my kids would go to bed at 8pm. So, I'd have two hours, you know? It's so much better. It's just made it better.

[Interviewer] And you have time for yourself now?

Yeah well, the thing is that (pause) my wife she (pause) you know, I (exhales air), raising kids is a difficult job. And, when I walk in the door she is ready to pass the baton or she wants me to help out right away, which of course anyone would. So, what I do... I don't tell her when I'm leaving work early, so [it's] my time. When I need time to myself, I'll leave work at like 2. I'll usually go to a guitar shop and just pick up an acoustic and just hang out for an hour or go shopping for an hour and the things is that I don't... I don't call my wife and tell her what I'm doing that. I just do that and then I come home and I say “Hey, I went guitar shopping this afternoon.” And, she'll usually go “(R sucks in his breath) so, that's where you've been for the last two hours!” But she's totally fine with that too. I mean, I usually get home 4:30 or 5 o'clock which is earlier than when I used to come home at 6. So, she's happy. I'm happy because, the job here [in this department] is REALLY demanding. So, I have a HUGE demand at work, and then of course I have two kids in diapers and of course, they are demanding, you know? So, it's hard to find time for yourself and I need to have that ‘cause I'm kind of an ambiovert. So, like I'm extroverted and introverted at times. So, I get energy out of other people but I need a break. And, I need my own time to recharge a little bit.

When asked at time 2 if he would make any additional changes to his boundaries, he said that ideally he would like to regularly leave work early every Tuesday and schedule (and keep) tee times. Otherwise, he would continue to keep coming into work Monday through Friday at 8ish and leave when he felt like he had reached a stopping point for the day.

Several told me that they saw themselves making large changes once their family or work demands altered (especially once they started families). Hank (single with no children) and Dwight (married with no children) are two such examples. When I asked Hank if he worked at home, he told me no:

[But] that might change, you know, as I get higher in the organization, you know? And, I have a little bit more responsibilities and stuff like that, which I wouldn't mind. But at the same point in time, I like getting here and getting my stuff done. After work is done, work is done. Either workout, [and] be active, or I just watch TV or read.

Dwight thought he might change his work-family boundaries and priorities if his household grew to include a dog. He envisioned working from home more so that he could train the puppy. Until then, he remained a reluctant above and beyonder and came into work Monday through Friday.

Since this study only examined how (and whether) normative changes in the work domain, lead to changes in work-family boundaries, it makes sense that I found evidence of limited alterations, especially among those with family responsibilities. They were still constrained by family members’ schedules and routines. Although a few respondents added some additional family responsibilities during the course of the study (more extensive eldercare responsibilities, another baby, or had a boyfriend move in) most respondents were still bound to the same family norms and obligations at the start and end of the study. If work and family normative constraints had been altered, larger changes might have occurred. But, nevertheless, there is good reason to believe that the small and slow changes respondents made during my observations might snowball over time and result in larger changes. At the end of data collection, respondents in this study had been working under FREE conditions for less than six months. Many described how difficult it had been for them to alter their routines. Overcoming the inertia of their old boundary routines was challenging. Once the process of altering boundaries had begun though, most were keen to slowly incorporate additional changes. Over time, more boundary changes may occur.

Discussion

This study examined the work-family boundaries of 23 respondents employed at the headquarters of a large Fortune 500 company. At this site, a cultural change initiative was beginning that loosened the norms surrounding when and where work could be done. This research contributes to boundary literature by empirically separating preferred boundaries from enacted boundaries and examines how aligned and stable these boundaries are when respondents are given more control over their work-related boundaries. I found that while enacted and preferred boundaries constantly shifted, the broad strategies that individuals employed were relatively durable. Although all respondents were encouraged to work differently under FREE, small changes were common but only a few fundamentally changed their boundary strategy.

More specifically, this study adds to our understanding of the boundaries workers have and desire, and the importance of directionality when assessing segmentation and integration tendencies. While technology and New Economy may encourage greater integration of work into the family/personal domain, scholars should not assume that all workers regard this type of integration as problematic or idyllic. Much like pebbles, individual boundaries are diverse and unique.

I found four broad types of strategies, some of which were more prevalent than others. Although the tendency to desire or enact a strategy that kept work from encroaching on other domains was common amongst the respondents at either time point, this may reflect the nature of the work that these respondents did: they all had white-collar jobs at the corporate headquarters of a large Fortune 500 company with stores in all US time zone. Their jobs were deadline and meeting heavy, fast-paced, and came with excellent benefits and pay, opportunities for advancement. Moreover, the corporate setting offered many amenities that could entice Streamline workers to never leave the building (such as an on-site gym, daycare, pharmacy, dry cleaning drop-off, and cafeteria). Many, but not all, respondents felt the need to guard against work, and did so by keeping it firmly on company property during standard business hours.

In several ways, the four strategies presented in this paper and the approach of examining enacted versus preferred boundaries compliments Kossek and Lautsch's (2008) study of work-family boundary strategies. They found that individuals with high boundary control were able to enact the boundaries they desired, while those with low control were forced into a boundary arrangement that they felt did not suit them (Kossek & Lautsch, 2008). Thus, both studies argue for a closer examination of how enactments and preferences come together. While there is some disagreement over specific types of work-family boundary strategies,8 some of my findings do support Kossek and Lautsch's (2008) research. For example, respondents who were reluctant above and beyonders had low control over their family boundaries (they were not able to be around their family members or friends, or engage in hobbies as much as they wanted) and they often had a poor work-family boundary fit. Similarly, when all respondents at time 2 were given greater control over their work boundaries under FREE, overall boundary fit improved. Thus, this study adds to the growing body of research that examines the role of contextual factors in boundary work.

A second contribution of the study is that it urges scholars who are interested in the relationship between boundaries and the work-family intersection to consider a boundary fit approach rather than a person-environment approach (see Kreiner, 2009; Rothbard, et al., 2005). Instead of focusing on the degree of congruence between environmental conditions and boundary preferences, researchers could investigate how environmental conditions undergird preferences and enactments, the alignment between these boundary forms, and whether or not misalignments between boundary enactments effect the work-family intersection. Boundary fit may directly or indirectly influence outcomes such as work-family conflict, work-family balance, and may yield greater insight into turnover intentions, work satisfaction, as well as mental and physical health. Although scholars are already pursing links between boundaries and these outcomes (Bulger et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2009; Kossek, et al., 2012; Kreiner, 2006; Park et al., 2011; Rothbard et al., 2005), they have concentrated solely on enacted boundaries, conflated boundary preferences and enactments, or examined alignment between workplace context and preferences: the degree of fit between desired and actual boundaries may yield more explanatory power.

Third, this study enriches our knowledge of boundary durability and change. When exposed to FREE, all respondents made some changes to their enacted and preferred boundaries but these change were often small and did result in a boundary strategy shift. Moreover, when dramatic change did occur, few deliberately sought it out. Instead, alterations to boundaries were unexpected, incremental, and sometimes even resulted in poorer boundary fits. So, why did most not shift strategies when the environmental conditions changed? One possibility is that respondents were happy with their current and desired boundaries and even though the norms in the workplace were altered, they did not feel the urge to make a boundary strategy change. Another, more likely possibility is that FREE was not perceived similarly across respondents. A study of FREE training sessions found that FREE challenged ideal worker norms, and men were more hesitant about deviating from this way of working than were women (Kelly et al., 2010). Thus, in the short term, loosening the norms around where and when work can be done does not affect all equally. Boundary changes may speed up as workers grow more comfortable in a FREE environment, but without an accompanying cultural change in family norms, individuals with heavy family demands will still limited the desired and enacted boundaries of some individuals. Nevertheless, the findings show that boundaries are not durable structures and that individuals do not regard them as such.

Care must be taken when generalizing these findings, however, which are bound to a particular context and group of workers. The data presented in this paper speak to the enacted and preferred work-family boundaries of white-collar workers in a corporate setting who underwent a specific cultural change initiative. Organizations adopting an initiative similar to FREE may find that employees make small, rather than drastic changes to their work-family boundaries and that many of the workers make unanticipated boundary alterations. But, they may also encounter other results due to differing organizational and occupational contexts.

Although the findings from this study improve our understanding of the nature and changeability of work-family boundaries, much work remains to be done. Continuing to empirically separate boundary preferences from boundary enactments and whether or not they fit are fruitful areas of study for scholars. Scholarship is also needed that explores how boundary fit ties to work-family conflict and enrichment perceptions, and how particular environmental conditions may encourage individuals to adopt and prefer specific boundary configurations.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This research was conducted as part of the Work, Family and Health Network (www.WorkFamilyHealthNetwork.org), funded by a cooperative agreement through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant # U01HD051217, U01HD051218, U01HD051256, U01HD051276), National Institute on Aging (Grant # U01AG027669), Office of Behavioral and Science Sciences Research, and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (Grant # U010H008788). Additional support was provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (#2002-6-8). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of these institutes and offices. Special acknowledgement goes to Extramural Staff Science Collaborator, Rosalind Berkowitz King, Ph.D. and Lynne Casper, Ph.D. for design of the original Workplace, Family, Health and Well-Being Network Initiative. I wish to express my gratitude to the employer and employees who participated in this research and made this publication possible, and to my advisors, Erin L. Kelly and Phyllis Moen, who provided moral support and guidance along the way.

Footnotes

Throughout the paper, family and personal life are used interchangeably to describe the non-work domain.

In their discussion of boundary transitions, Ashforth and colleagues (2000) treat desired boundaries as an underlying assumption, and while Nippert-Eng (1996) does extensively discuss the social constraints of work and family that inhibit personal discretion and narrow the range of boundary options, she does not ask her interviewees what boundaries they would ideally like to have. In their recent work, Kossek et al (2005) do differentiate between desired and actual boundaries but do not theorize about their interconnectedness, or empirically investigate boundary preferences. More recently, Kossek and Lautsch (2007) meld enacted and preferred boundaries together and do not treat each as separate entities.

For example, respondents were asked “what kinds of things do you usually think about when you are at home?” I coded this question and response as “cognitive boundaries” but I also found instances of it as I coded line-by-line. Other codes were emergent, such as “personality,” “values” and “SBO” (strength based organizational trait).

For example, there was a monthly calendar of a country she wants to visit that was given to her by her mother, a framed photo of her and her best friend taken at their favorite vacation spot, photographs of her pets, a homemade pottery dish that she recently made, and a rolled up yoga mat in the corner. Alongside these objects were the company's fiscal calendar, several recognition certificates and certificates of completed trainings, a row of binders filled with work materials, file folders, and the statement of company's strategic goals for the year.

When I asked respondent if they felt like two different people when they were at home and at work, most said that they were not the same, but a few said that they were more private or subdued at work and did not share their personal lives much with their coworkers, but they were usually very open with people. Two respondents thought their behavior was markedly different though. One cursed all the time at home and could not do that at work because of the corporate office culture. The other was said he felt more authoritarian at home because of his fatherhood responsibilities.

Other small temporal changes included cutting back on weekend work, or taking a weeklong vacation without checking their email.

Two respondents underwent subtle transitions as well. One respondent changed her at-home work location from her kitchen counter to a designated office nook once FREE took effect, while another respondent occasionally worked in a meeting room at Streamline rather than at her cubical.

Kossek and Lautsch (2008) found three broad boundary strategies: 1) “integrators,” who completely integrated work and family domains, 2) “separators,” who completely separated work and family domains, and 3) “volleyers,” who switched back and forth between an integration and segmentation strategy over the course of a week, month, season or year. Each strategies was further divided into those with high boundary control who are happy (“fusion lovers,” “firsters,” and “quality timers”) and those with low boundary control who are unhappy (“reactors,” “captives,” and “job warriors”). Thus, Kossek and Lautsch (2008) discuss an overarching boundary strategy that I do not (volleyers), but I include directional nuances in segmentation and integration from work-to-family and/or family-to-work which does not appear in their work, and I separate preferences from enactments.

Bibliography

- Ammons SK. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Minnesota; Minneapolis, MN.: 2008. Boundaries at work: A study of work-family boundary stability within a large organization. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth B, Kreiner G, Fugate M. All in a day's work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review. 2000;25:472–491. [Google Scholar]

- Bailyn L. Breaking the mold: Women, men, and time in the new corporate world. Free Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bellavia GM, Frone MR. Work-family conflict. In: Barling J, Kelloway K, Frone's MR, editors. Handbook of work stress. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 2005. pp. 113–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Milkie MA, Sayer LC, Robinson JP. Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces. 2000;79:191–228. [Google Scholar]

- Bulger CA, Mathews RA, Hoffman ME. Work and personal life boundary management: Boundary strength, work/personal life balance, and the segmentation-integration continuum. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2007;12:365–375. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.4.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Powell GN, Greenhaus JH. Work-to-family conflict, positive spillover, and boundary management: A person-environment fit approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009;74:82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cohany SR, Sok E. Trends in labor force participation of married mothers of infants. Monthly Labor Review. 2007;130:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Rothbard N. Work and family stress and well-being: An examination of person-environment fit in the work and family domains. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1999;77:85–129. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1998.2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter; New York: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus JH, Powell GN. When work and family are allies: A theory of work- family enrichment. Academy of Management Review. 2006;31:72–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman RE. Work, Culture and Society in America. In: Pahl's RE, editor. On work: Historical, comparative and theoretical approaches. Blackwell; New York: 1988. pp. 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht TD, Allen NJ. A longitudinal examination of the work-nonwork boundary strength construct. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2009;30:839–862. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL, Ammons SK, Chermack K, Moen P. Gendered challenge, gendered response: Confronting the ideal worker norm in a white collar organization. Gender & Society. 2010;24:281–303. doi: 10.1177/0891243210372073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Lautsch BA. CEO of me: Creating a life that works in the flexible job age. Pearson; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Lautsch BA. Work-family boundary management styles in organizations: A cross-level model. Organizational Psychology Review. 2012;2:152–171. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Noe RA, DeMarr BJ. Work-family role synthesis: Individual and organizational determinants. The International Journal of Conflict Management. 1999;10:102–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Ruderman MN, Braddy PW, Hannum KM. Work-nonwork boundary management profiles: A person-centered approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2012;81:112–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Lautsch B, Eaton S. Family flexibility theory: Implications of flexibility type, control, and boundary management for work-family effectiveness. In: Kossek EE, Lambert's S, editors. Work and life integration: Organizational, cultural and individual perspectives. Erlbaum; London: 2005. pp. 243–262. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner GE. Consequences of work-home segmentation or integration: A person- environment fit perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2006;27:485–507. [Google Scholar]

- Mills CW. The sociological imagination. Oxford University Press; New York: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, Chermack K. Gender disparities in health: Strategic selection, careers, and cycles of control.”. The Gerontologist. 2005;60:99–108. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nippert-Eng C. Home and work: Negotiating boundaries in everyday life. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Fritz C, Jex SM. Relationships between work-home segmentation and psychological detachment from work: The role of communication technology use at home. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2011;16:457–467. doi: 10.1037/a0023594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbard NP, Phillips KW, Dumas TL. Managing multiple roles: Work-family policies and individual's desires for segmentation. Organization Science. 2005;16:243–258. [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. Unbending gender: Why work and family conflict and what to do about it. University Press; Oxford: 2000. [Google Scholar]