Abstract

The X-ray crystal structure of an arginase-like protein from the parasitic protozoan Trypanosoma brucei, designated TbARG, is reported at 1.80 and 2.38 Å resolution in its reduced and oxidized forms, respectively. The oxidized form of TbARG is a disulfide-linked hexamer that retains the overall architecture of a dimer of trimers in the reduced form. Intriguingly, TbARG does not contain metal ions in its putative active site, and amino acid sequence comparisons indicate that all but one of the residues required for coordination to the catalytically obligatory binuclear manganese cluster in other arginases are substituted here with residues incapable of metal ion coordination. Therefore, the structure of TbARG is the first of a member of the arginase/deacetylase superfamily that is not a metalloprotein. Although we show that metal binding activity is easily reconstituted in TbARG by site-directed mutagenesis and confirmed in X-ray crystal structures, it is curious that this protein and its parasitic orthologues evolved away from metal binding function. Knockout of the TbARG gene from the genome demonstrated that its function is not essential to cultured bloodstream-form T. brucei, and metabolomics analysis confirmed that the enzyme has no role in the conversion of l-arginine to l-ornithine in these cells. While the molecular function of TbARG remains enigmatic, the fact that the T. brucei genome encodes only this protein and not a functional arginase indicates that the parasite must import l-ornithine from its host to provide a source of substrate for ornithine decarboxylase in the polyamine biosynthetic pathway, an active target for the development of antiparasitic drugs.

Human African trypanosomiasis is a neglected tropical disease caused by Trypanosoma brucei, parasitic protozoa transmitted by the tsetse fly.1,2 In humans, this disease is more commonly known as sleeping sickness, and in livestock, it is known as nagana.2,3 Early-stage infection involves parasitic infestation of the hemolymphatic system and in humans presents with nonlethal symptoms, such as chronic intermittent fever and headache. Late-stage infection begins as the parasite crosses the blood–brain barrier, giving rise to neurological and psychiatric dysfunction, including sleep disorders.2 If left untreated, late-stage infection is almost always lethal.

The incidence of human trypanosomiasis has diminished in recent years, and the World Health Organization has set a target date of 2030 to eliminate the disease as caused by the subspecies Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. However, there is a dearth of effective drugs for the treatment of early- and late-stage infections.4,5 Current first-line treatment depends on eflornithine (d,l-α-difluoromethylornithine) therapy, particularly in combination with nifurtimox.5,6 Eflornithine is a mechanism-based inhibitor of ornithine decarboxylase, which catalyzes a key step in the biosynthesis of polyamines that facilitate growth and proliferation of the parasite.7−10 Possibly, other enzymes of polyamine biosynthesis could also serve as drug targets for the treatment of parasitic infections.11,12 For example, the manganese metalloenzyme arginase catalyzes the hydrolysis of l-arginine to form l-ornithine and urea.13−15 In the related parasite Leishmania mexicana, knockout mutants confirm that arginase is required for parasite viability,16 so the inhibition of arginase is a validated strategy in the search for new antiparasitic agents.

Interestingly, T. brucei contains a single gene, Tb927.8.2020, that encodes an arginase-like protein, henceforth designated TbARG; this gene is syntenic with a gene in Leishmania that is present in addition to the verified arginase.16 The amino acid sequence of TbARG is only 24% identical with that of rat arginase I, and even less identical to those of arginases from other organisms, but this minimal level of sequence identity is sufficiently high to suggest a homologous three-dimensional structure. Strikingly, however, analysis of the amino acid sequence suggests that TbARG lacks all but one of the ligands that coordinate to the catalytically obligatory Mn2+ ions found in the arginases. Accordingly, TbARG may not be a metalloprotein. There is precedent for the evolution of alternative metal binding function in the arginase fold; this fold is also adopted by metal-dependent deacetylases such as polyamine deacetylase or the histone deacetylases, which utilize a single Zn2+ ion for catalysis.17 However, there is no precedent for the complete loss of metal binding function in the arginase fold.

Here, we report the X-ray crystal structure determination of TbARG, conclusively demonstrating that this protein adopts the arginase fold. We also show that TbARG is the first arginase-like protein that lacks the capacity for binding metal ions in its active site. However, we can restore metal ion binding by reintroducing metal ligands into the active site through site-directed mutagenesis. Removal of the protein from bloodstream-form trypanosomes by gene knockout reveals it to be nonessential, and no changes in l-arginine or l-ornithine levels are detected in knockout cells. Finally, we have screened wild-type TbARG for ligand binding activity against a library of small molecules, and we find a slight preference for the binding of cationic amino acids such as lysine. Even so, the molecular function of this protein remains an enigma.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (98%, TCEP) was purchased from Gold Biotechnology. A 50% (w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 solution, 50% Jeffamine ED-2001, and a 100% Tacsimate solution (pH 7.0) were purchased from Hampton Research. All the peptides used in this study were purchased from Bachem. All other chemicals were purchased from either Fisher Scientific or Sigma-Aldrich.

Expression and Purification of TbARG

The pET-28a plasmid encoding wild-type TbARG (UniprotKB entry Q581Y0, gene name Tb927.8.2020) with a 20-residue N-terminal His6 tag and a thrombin cleavage site was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) and B834(DE3) cells (Novagen Inc.). Native TbARG was overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) grown in lysogeny broth (LB) media supplemented with 50 mg/L kanamycin. Expression was induced by 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (Carbosynth) for 16 h at 22 °C until the OD600 reached 0.6–0.7. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000g for 10 min. The cell pellet was suspended in 50 mL of buffer A [50 mM K2HPO4 (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, and 10% (v/v) glycerol]. Cells were lysed by sonication on ice using a Sonifer 450 (Branson), and the cell lysate was further incubated with 5 μg/mL DNase I (Sigma) and 6 μg/mL RNase A (Roche Applied Science) at 4 °C for 30 min. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 15000 rpm for 1 h. The clarified supernatant was applied to a Talon column (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA) pre-equilibrated with buffer A. TbARG was purified with a 200 mL gradient from 10 to 300 mM imidazole. Pooled fractions were dialyzed into buffer B [15 mM K2HPO4 (pH 7.5), 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME), and 100 μM MnCl2] and subsequently loaded onto a 10 mL Q-HP anion exchange column (GE Healthcare). Protein was eluted with a 500 mL gradient from 0 to 800 mM NaCl. The estimated purity of protein samples was greater than 95% based on sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Fractions containing TbARG were combined and concentrated using Amicon ultra filter units (Millipore) with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff followed by exchange into buffer C [50 mM bicine (pH 8.5), 100 μM MnCl2, and 1 mM TCEP] using a Superdex 200 preparative grade 26/60 size exclusion column (GE Healthcare). Mutants were expressed and purified using a procedure similar to that employed for wild-type TbARG, except that minimal medium [1× M9 salts, 0.5% casamino acids, 20 mM d-(+)-glucose, 2 mM MgSO4, and 100 μM CaCl2] supplemented with 200 μM MnCl2 was used to prevent metal contamination, and the induction temperature was lowered to 16 °C.

Selenomethionine-derivatized (Se-Met) TbARG was overexpressed in E. coli B834(DE3) cells grown in Seleno-Met Medium Base (AthenaES) supplemented with SelenoMet Nutrient Mix (AthenaES) and 40 mg L–1 seleno-l-methionine (Acros). The expression and purification of Se-Met TbARG were performed using a procedure essentially identical to that used for wild-type TbARG, except that 2 mM TCEP was included in buffer A and buffer C and 5 mM BME was included in buffer B.

Mutagenesis

To re-engineer metal binding sites in TbARG, selected active site residues were mutated to reintroduce the Mn2+A site and the Mn2+B site separately, as well as both sites simultaneously. Five mutants were generated using the QuikChange method (Stratagene) and verified by DNA sequencing. Primers are listed in Table S1 of the Supporting Information. Briefly, mutants MA1 (S149D/S153D) and MA2 (S149D/S153D/G124H/Y267A) were prepared to reintroduce the Mn2+A site; mutant MB (S149D/R151H/S226D) was prepared to reintroduce the Mn2+B site, and mutants MA1B (S149D/S153D/R151H/S226D) and MA2B (S149D/S153D/G124H/Y267A/R151H/S226D) were prepared to mimic both sites simultaneously.

Crystallography

Crystals of TbARG and its mutants were prepared by the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method at 21 °C. For wild-type TbARG in its oxidized form (space group H32), a 0.4 μL drop of protein solution [20 mg/mL TbARG, 50 mM bicine (pH 8.5), 100 μM MnCl2, and 1 mM TCEP] was mixed with a 0.4 μL drop of precipitant solution [2% (v/v) tacsimate (pH 7.0), 5% (v/v) 2-propanol, 0.1 M imidazole (pH 7.0), and 8% PEG 3350] and equilibrated against a 80 μL reservoir of precipitant solution. For wild-type TbARG in its reduced form (space group P3), a 0.4 μL drop of protein solution [20 mg/mL TbARG, 50 mM bicine (pH 8.5), 100 μM MnCl2, and 10 mM TCEP] was mixed with a 0.4 μL drop of precipitant solution [0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5) and 18% PEG 3350]. For TbARG mutant MB, a 0.4 μL drop of protein solution [20 mg/mL TbARG mutant MB, 50 mM bicine (pH 8.5), 100 μM MnCl2, and 1 mM TCEP] was mixed with a 0.4 μL drop of precipitant solution [20% (v/v) Jeffamine ED-2001 and 0.1 M imidazole (pH 7.0)]. For TbARG mutant MA1, a 0.4 μL drop of protein solution [20 mg/mL TbARG mutant MA1, 50 mM bicine (pH 8.5), 200 μM NiCl2, and 1 mM TCEP] was mixed with a 0.4 μL drop of precipitant solution [0.2 M KF and 20% (v/v) PEG 3350]. For TbARG mutant MA1B, a 0.4 μL drop of protein solution [20 mg/mL TbARG mutant MA1B, 50 mM bicine (pH 8.5), 200 μM NiCl2, 100 μM MnCl2, and 1 mM TCEP] was mixed with a 0.4 μL drop of precipitant solution [0.2 M KNO3 and 20% (v/v) PEG 3350]. For Se-Met TbARG, a 5 μL drop of protein solution [20 mg/mL protein, 50 mM bicine (pH 8.5), 100 μM MnCl2, and 1 mM TCEP] was mixed with a 5 μL drop of precipitant solution [0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.0), 5% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol, and 10% PEG 3350] and equilibrated against a 500 μL reservoir of precipitant solution.

Crystals appeared after 2–3 days and were flash-cooled after being transferred to a cryoprotectant solution consisting of the reservoir solution and 20% (v/v) glycerol, with the exception that the crystal of wild-type TbARG in space group P3 was cryoprotected with reservoir solution, 25% (v/v) 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol, and 25% PEG 400. Diffraction data were collected on beamline X29 at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY). Crystals of native TbARG diffracted X-rays to 2.4 Å resolution and belonged to space group H32 with one monomer per asymmetric unit (Matthews coefficient VM = 2.49 Å3/Da; solvent content = 51%). Attempts to phase the initial electron density map by molecular replacement using known structures of arginase/deacetylase family proteins were unsuccessful. For experimental phasing, single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) data were collected from a single crystal of Se-Met TbARG at the peak wavelength of 0.9788 Å (as determined by an X-ray fluorescence scan). The Se-Met TbARG crystal diffracted X-rays to 2.6 Å resolution and belonged to space group P321. With two monomers in the asymmetric unit, the Matthews coefficient VM = 3.22 Å3/Da, corresponding to a solvent content of 62%. Diffraction data were integrated and scaled with HKL2000.18 Data collection and reduction statistics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Data Collection and Refinement Statistics.

| Se-Met (reduced) | wild type (reduced) | wild type (oxidized) | mutant MA1 (reduced) | mutant MB (oxidized) | mutant MA1B (reduced) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collectiona | ||||||

| wavelength (Å) | 0.9788 (Se peak) | 1.075 | 1.075 | 1.075 | 1.075 | 1.075 |

| space group | P321 | P3 | H32 | C2 | P321 | C2 |

| unit cell dimensions | ||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 139.0, 139.0, 90.5 | 139.2, 139.2, 90.2 | 153.2, 153.2, 85.4 | 83.2, 138.1, 90.9 | 135.6, 135.6, 86.7 | 82.1, 173.4, 87.8 |

| α, β, γ (deg) | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 | 90.0, 102.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 | 90.0, 102.3, 90.0 |

| resolution (Å) | 42.36–2.55 (2.64–2.55) | 42.23–1.80 (2.64–1.80) | 40.66–2.38 (2.47–2.38) | 44.49–2.18 (2.26–2.18) | 48.61–3.10 (3.21–3.10) | 42.90–1.95 (2.02–1.95) |

| total no. of reflections | 727053 (70959) | 1614161 (143386) | 280023 (23240) | 314490 (27545) | 341313 (32185) | 385476 (22261) |

| no. of unique reflections | 33080 (3262) | 181427 (18150) | 15479 (1527) | 51646 (5101) | 16959 (1673) | 64646 (4543) |

| completeness (%) | 99.9 (98.8) | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.9 (99.8) | 99.9 (99.3) | 100.0 (100.0) | 94.3 (73.4) |

| I/σI | 30.2 (4.5) | 24.5 (2.1) | 31.4 (2.0) | 13.2 (2.0) | 14.0 (2.0) | 17.1 (2.0) |

| redundancy | 22.0 (21.8) | 8.9 (7.9) | 18.1 (15.2) | 6.1 (5.4) | 20.1 (18.7) | 6.0 (4.9) |

| Rmergeb | 0.152 (1.01) | 0.084 (1.095) | 0.107 (1.40) | 0.127 (0.76) | 0.194 (1.13) | 0.091 (0.54) |

| Rpimc | 0.033 (0.22) | 0.032 (0.41) | 0.026 (0.35) | 0.056 (0.35) | 0.056 (0.38) | 0.039 (0.64) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 37 | 20 | 63 | 26 | 57 | 30 |

| Se-SAD phasing | ||||||

| no. of Se atoms | 23 (of a possible 26) | |||||

| figure of merit (FOM) | 0.404 | |||||

| FOM after density modification (DM) | 0.672 | |||||

| Refinementa | ||||||

| Rwork (%)d | 22.1 (26.2) | 19.6 (29.4) | 22.7 (40.5) | 20.5 (29.7) | 21.5 (28.1) | 20.1 (31.6) |

| Rfree (%) | 26.1 (33.4) | 23.4 (32.7) | 25.6 (40.6) | 23.8 (36.1) | 27.4 (34.7) | 23.7 (34.7) |

| twinning fraction | 0 | 0.45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| twin law | N/A | h, −h–k, −l | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| no. of moleculese | 2 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| no. of atoms | ||||||

| protein | 4833 | 13320 | 2405 | 7101 | 4651 | 7081 |

| water | 161 | 308 | 96 | 163 | 31 | 129 |

| ligand | 12 | 16 | 6 | 32 | 12 | 48 |

| metal ions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| average B factor (Å2) | ||||||

| protein | 43 | 25 | 84 | 40 | 51 | 52 |

| solvent | 38 | 21 | 74 | 34 | 39 | 47 |

| ligand | 68 | 24 | 74 | 55 | 48 | 67 |

| metal ions | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 42 | 33 |

| root-mean-square deviation for bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| root-mean-square deviation for bond angles (deg) | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||||||

| allowed | 90.2 | 88.7 | 91.9 | 92.9 | 88.1 | 91.1 |

| additional allowed | 9.6 | 11.2 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 10.5 | 8.5 |

| generously allowed | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.4 |

| disallowed | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Numbers in parentheses refer to values for the highest-resolution shell.

Rmerge = ∑|I – ⟨I⟩|/∑I, where I is the observed intensity and ⟨I⟩ is the average intensity from calculated from replicate data. Rmerge values can be anomalously high for highly redundant data, in which case Rpim is a better indicator of data quality.

Rpim = ∑(1/n – 1)1/2|I - ⟨I⟩|/∑I, where n is the number of observations (redundancy) and ⟨I⟩ is the average intensity calculated from replicate data.

Rwork = ∑||Fo| – |Fc||/∑|Fo| for reflections contained in the working set. Rfree = ∑||Fo| – |Fc||/∑|Fo| for reflections contained in the test set held aside during refinement. |Fo| and |Fc| are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

Per asymmetric unit.

The structure of Se-Met TbARG was determined by SAD with data truncated to 3.2 Å resolution. Initially, 21 selenium sites in the asymmetric unit were located using HKL2MAP.19 Two additional sites were located by using PHENIX AutoSol.20 A Bijvoet difference Fourier map showing the positions of selenium atoms in monomer A is found in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information. Initial experimental phases were improved by noncrystallographic symmetry averaging and solvent flattening using RESOLVE (PHENIX),20 and phases were extended to 2.7 Å resolution. Automatic model building performed by phenix.autobuild successfully fit 70% of the protein residues. Iterative cycles of refinement and manual model building against 2.55 Å resolution data were performed using phenix.refine20 and Coot.21

The structures of wild-type TbARG were determined by molecular replacement using the coordinates of Se-Met TbARG as a search probe for rotation and translation function calculations with PHASER22 implemented in the CCP4 suite.23 The structures of mutant MA1, mutant MA1B, and mutant B were similarly determined by molecular replacement using the coordinates of wild-type TbARG as a search probe. Solvent molecules and ligands were added in the final stages of refinement for each structure. The degree of crystal twinning was assessed using routines implemented in PHENIX (phenix.xtriage);24,25 only wild-type TbARG in the P3 crystal form exhibited nearly perfect twinning. Structure factor amplitudes were detwinned computationally using the structure-based algorithm of Redinbo and Yeates26,27 for the calculation of electron density maps, and twinned structure factor amplitudes were utilized for refinement after the twin law was applied, similar to our approach first outlined for inhibitor complexes with rat and human arginases.28,29

Disordered segments not included in the final models are as follows: Se-Met TbARG, M316–H331 in monomer A and E307–H331 in monomer B; wild-type TbARG (H32 crystal form), E71, T72, and E312–H331; wild-type TbARG (P3 crystal form), H200–R211 and A299–H331; mutant MB, H305–H331 in monomer A and E71–V73, A88, A89, and H305–H331 in monomer B; mutant MA1, T306–H331 in monomer A, E71, T72, and E307–H331 in monomer B, and E307–H331 in monomer C; mutant MA1B, E307–H331 in monomer A, E71, T72, and E307–H331 in monomer B, and E87–G90 and H305–H331 in monomer C. The quality of each final model was verified with PROCHECK.30 Surface area calculations were performed with PISA.31 Refinement statistics are listed in Table 1.

Thermal Stability Shift Assay

To evaluate potential ligands capable of binding to TbARG, a thermal stability shift assay was performed by screening a small library of ligands (listed in Table S2 of the Supporting Information) based on the protocol described by Niesen and colleagues32 with minor modification. Protein/ligand mixtures [20 μL of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5× SYPRO Orange (Invitrogen), 3 μM TbARG, and 1–5 mM ligand] were dispensed into MicroAmp Fast 96-well Reaction Plates (Applied Biosystems). Thermal melting experiments were performed with the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The melt curve was programmed with a ramp rate of 1 °C/s from 25 to 95 °C. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and data analysis was performed using StepOnePlus.

Activity Assays

To evaluate possible biological functions of TbARG, several enzyme activity assays were performed. Ureohydrolase activity was assessed using the colorimetric assay developed by Archibald.33 The following compounds were used as potential substrates for the ureohydrolase activity assay: l-arginine, agmatine, Nα-acetyl-l-arginine, l-homoarginine, α-guanidinoglutaric acid, 3-guanidinopropionic acid, 4-guanidinobutyric acid, and l-2-amino-3-guanidinopropionic acid. Lysine deacetylase activity was assessed using the Fluor-de-Lys deacetylase substrate (BML-KI104 ENZO Life Sciences) and the Fluor-de-Lys-HDAC8 deacetylase substrate (BML-KI178, ENZO Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Arginine deiminase activity was assessed using a colorimetric assay to detect the formation of l-citrulline from l-arginine.34 Formiminoglutamase activity was measured colorimetrically with the substrate l-formiminoglutamic acid (Dalton Pharma Services, Toronto, ON).35 The binding of NADPH and that of NADH were investigated by monitoring the fluorescence emission change of NAD(P)H upon titration of NAD(P)H into TbARG solutions. Fluorescence emission spectra (from 400 to 600 nm) were recorded with a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer with an excitation wavelength of 340 nm.

Metal Content Analysis

To analyze TbARG and its site-specific mutants for bound metal ions, inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) was employed. Prior to analysis, samples were extensively dialyzed against 10 mM bicine (pH 8.5) to remove free trace metal ions. Samples were sent to the Center for Applied Isotope Studies of the University of Georgia (Athens, GA) for analysis.

Parasite Culturing and Δarg Construction

Bloodstream-form T. brucei parasites were cultured in cardiac myocyte media36 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The TbARG gene was knocked out in the Lister 427 strain to obtain strain Δarg. The 5′ and 3′ UTRs of the TbARG gene were amplified from T. brucei genomic DNA [primers 5UTR_F, 5UTR_R, 3UTR_F, and 3UTR_R (Table S1 of the Supporting Information)] and cloned flanking a hygromycin or puromycin resistance cassette into vector pTBT.37 Parasites were transformed in two rounds with a NotI-linearized construct as described previously,38 to replace both allelic copies with the hygromycin and puromycin resistance cassette, respectively. Positive clones were selected using 2.5 μg mL–1 hygromycin and 0.2 μg mL–1 puromycin, and correct integration of the resistance cassettes was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Figure S2 of the Supporting Information). Sensitivity to oxidative stress was assessed by alamarBlue assay,39 where oxidative stress was induced by methylene blue.

Metabolomics Analysis

Metabolites were extracted from Lister 427 and Δarg strains as described previously40 and analyzed on an Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) coupled to a U3000 RSLC high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) instrument (Dionex) with a ZIC-HILIC or ZIC-pHILIC column (Sequant), as described previously.41,42 Data analysis was performed using mzMatch43 and IDEOM.44 Metabolite identifications are generally at level 2 according to the Metabolomics Standards Initiative, i.e., putative and based on exact mass measurement translated to the elemental formula, although identification of l-arginine, l-ornithine, and putrescine was corroborated using authentic standards and matched retention times using HPLC.45 Significantly changed metabolites were selected using a nonparametrical statistical method, rank products,46 and 10000 random permutations of the data sets were used to calculate false discovery rates (FDRs). An FDR of <5% was designated as significantly changed.

Results and Discussion

Structure of Wild-Type TbARG

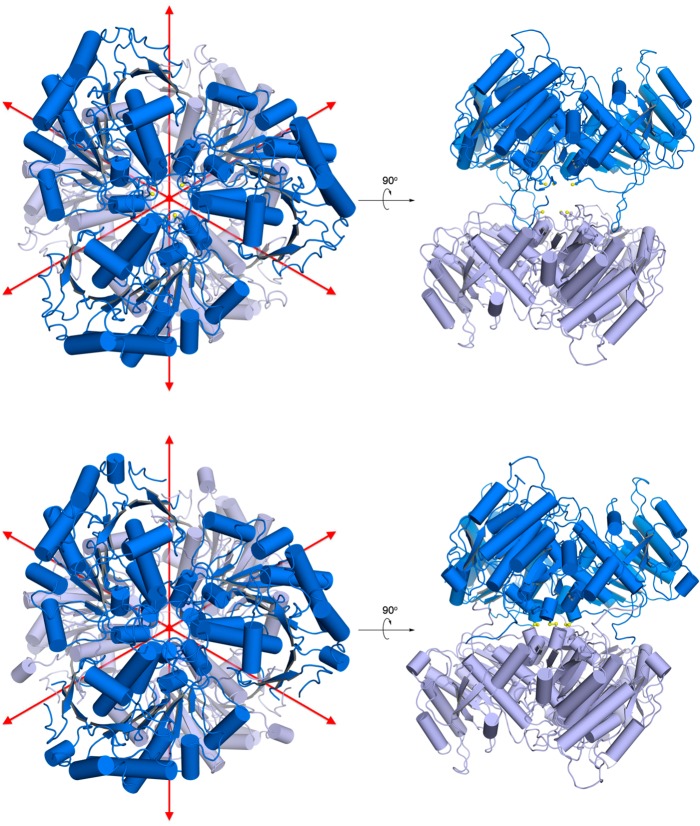

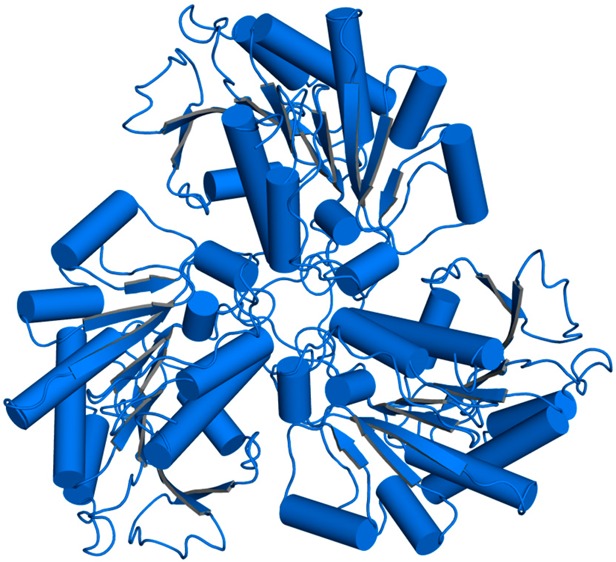

TbARG crystallizes as a hexamer in both H32 and P321 space groups (Figure 1), but as a trimer in space group P3 (data not shown). The hexamer consists of a dimer of trimers assembled with D3 (H32 crystal form) or pseudo-D3 (P321 crystal form) point group symmetry, burying ∼5000 Å2 of surface area between two trimers and ∼7100 Å2 of surface area within each trimer. Notably, three intermolecular C209–C209 disulfide linkages form between monomers related by 2-fold crystallographic symmetry in the H32 crystal form, but not in the P321 crystal form. Disulfide linkage formation brings the two trimers closer together and is accompanied by significant conformational changes in the C-termini that allow closer contact. The tertiary structures of TbARG in all crystal forms are essentially identical [root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) of 0.23 Å for 252 Cα atoms between the P321 and H32 crystal forms; rmsd of 0.38 Å for 254 Cα atoms between the P3 and H32 crystal forms], apart from conformational changes of the C-terminus and loop L6 (G206–P218), which contains C209.

Figure 1.

Hexameric structures of TbARG in the P321 (top) and H32 (bottom) space groups. In the P321 crystal form, the top trimer (dark blue) and the bottom trimer (light blue) result from crystal symmetry operations with two separate monomers in the asymmetric unit. Red arrows indicate 2-fold symmetry axes. In the H32 crystal form, the entire hexamer results from crystal symmetry operations with one monomer in the asymmetric unit. C209 is shown in ball-and-stick representation and forms intermolecular disulfide linkages in the H32 crystal form. Note that in the P321 crystal form, the C-termini of the bottom trimer (light blue) are disordered and are not shown.

The hexameric architecture of TbARG resembles that of prokaryotic arginase and arginase-like enzymes,47−51 as well as that of eukaryotic Plasmodium falciparum arginase.52 However, the TbARG hexamer assembles in an orientation such that the central parallel β-sheet of each trimer points away from the dimer interface. In contrast, the central parallel β-sheet of each trimer is oriented toward the dimer interface in previously reported hexameric arginase structures, such that the active sites are buried between two trimers.47−52 It seems that the close association of one TbARG trimer with another in the crystal can be mediated by either face of the trimer as one compares hexameric quaternary structures, perhaps suggesting that the dimerization of trimers is artifactual. Under reducing conditions, TbARG is determined to be a trimer in solution by size exclusion chromatography (Figure S3a of the Supporting Information). Thus, the trimer is most likely to be the physiologically significant species, and the disulfide linkage observed in the crystal structure of the reduced form of the hexamer is probably artifactual. A comparison of TbARG quaternary structure with that of P. falciparum arginase is found in Figure S3b of the Supporting Information.

Despite a very low level of amino acid sequence identity (∼20%) shared with other ureohydrolase family proteins and the loss of ligands to the catalytically essential binuclear manganese cluster indicated by amino acid sequence alignments, the TbARG monomer adopts the classical α/β arginase/deacetylase fold first observed in the crystal structure of rat arginase I (Figure 2a).53 The overall topology of TbARG is characteristic of the arginase/deacetylase family with a 2–1–3–8–7–4–5–6 strand order, with an additional β-strand inserted between strands 1 and 2 (β1a) and an additional α-helix (αA0) at the N-terminus (Figure 2b). Structural analysis using the DALI server54 shows that ureohydrolase family proteins are the most closely related structural homologues of TbARG, followed by zinc-dependent deacetylases. The closest structural homologue is proclavaminate amidino hydrolase from Streptomyces clavuligerus,49 with an rmsd of 2.2 Å for 254 Cα atoms.

Figure 2.

(a) Stereoview of the TbARG monomer. Secondary structure elements are defined by the DSSP algorithm.67 (b) Topology diagram of TbARG. Two inserted secondary structural elements relative to the classic arginase-deacetylase fold are highlighted in red: α-helix A0 and β-strand 1a.

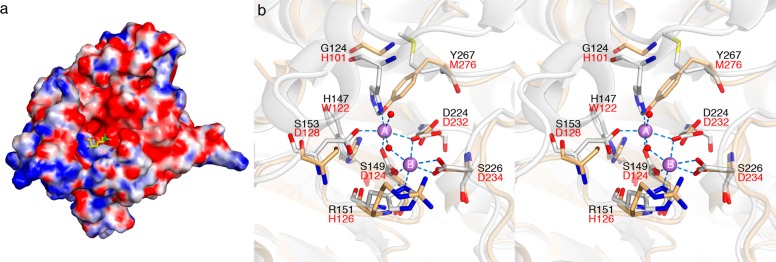

The active site of an enzyme belonging to the arginase/deacetylase family is located at the edge of β-strands 8, 7, and 4;55 loops L1, L4, and L5 flank the active site and largely define the active site contour and substrate specificity.56 Although loop L5 is structurally similar between TbARG and human arginase I, loops L1 and L4 exhibit significant differences when the two structures are superimposed. In particular, loops L1 and L4 and their connecting helices shift back away from the mouth of the active site, resulting in a broader cleft in TbARG. Even so, the putative active site cleft of TbARG is ∼9 Å deep and is characterized by negative electrostatic surface potential (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

(a) Electrostatic surface potential of TbARG calculated by the APBS server68 at pH 8.0 ranges from −10 kT (red) to 10 kT (blue). The ABH ligand from the HAI–ABH complex (PDB entry 2AEB) is superimposed onto TbARG and shown as stick model to indicate the position and orientation of arginase active site. (b) Active site superposition of TbARG (white) and human arginase I (blue, PDB entry 2PHA). Mn2+ ions from human arginase I are shown as salmon spheres.

The crystal structure of TbARG confirms the lack of any bound metal ions in the putative active site. Therefore, the structure of TbARG is the first of an arginase/deacetylase family member lacking a metal binding site. Active site comparisons reveal that only the μ–η1,η1 bridging aspartate ligand of human arginase I (D232) is conserved in TbARG as D224. The remaining aspartate and histidine ligands are substituted with serine, glycine, and arginine residues, as shown in Figure 3b. Interestingly, the side chain of Y267 occupies the steric void caused by the substitution of H101 in human arginase I with G124 in TbARG.

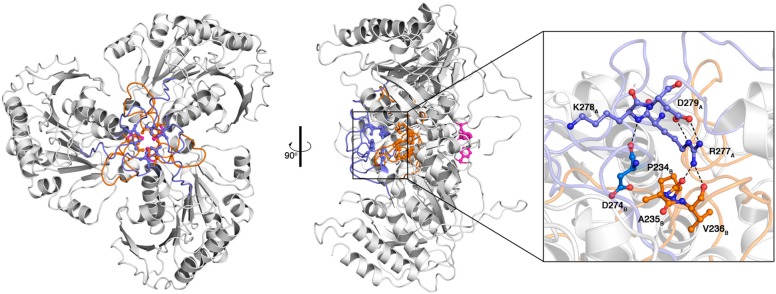

Assembly of the TbARG trimer is generally similar overall to the assembly of arginase trimers from other species, particularly with regard to the orientation of each monomer with respect to the 3-fold symmetry axis. However, oligomerization motifs in TbARG differ from those observed in other arginases. In mammalian arginases, the S-shaped tail at the C-terminus mediates significant intermonomer contacts, and two salt-linked networks stabilize trimer assembly: D204A–R255B–E256A and D204A–R308B–E262B (human arginase I numbering convention).53,57 These networks are not conserved in TbARG. Instead, loops L6–L8 predominantly mediate the trimerization of TbARG. A cluster of hydrophobic residues, including F208 (L6), A231 and F232 (L7), and V275 and L283 (L8), is buried along the 3-fold symmetry axis. Additionally, several inter- and intrasubunit hydrogen bonds that involve loops L7 and L8 are observed (Figure 4). The backbone NH group of K278A (L8A) donates a hydrogen bond to the backbone carbonyl of D274B (L8B). The side chain of R277A (L8A) donates two hydrogen bonds to the backbone carbonyls of P234B and V236B (L7B) and also forms an intramonomer salt link with D279A. These interactions may be important for maintaining loop conformations that support trimer assembly. Parenthetically, we note that the nine-residue insertion in loop L8 of TbARG relative to human arginase I is reminiscent of the 11-residue insertion in loop L8 of protozoan P. falciparum arginase, which is also involved in trimer assembly.52

Figure 4.

Top and side views of the TbARG trimer. Loops L7 and L8 are colored orange and blue, respectively; F208 from loop L6 is colored magenta. Selected side chains of hydrophobic residues from loops L7 and L8 are also indicated. Inter- and intramonomer interactions involving loops L8A, L8B, and L7B are illustrated on the right; green dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds.

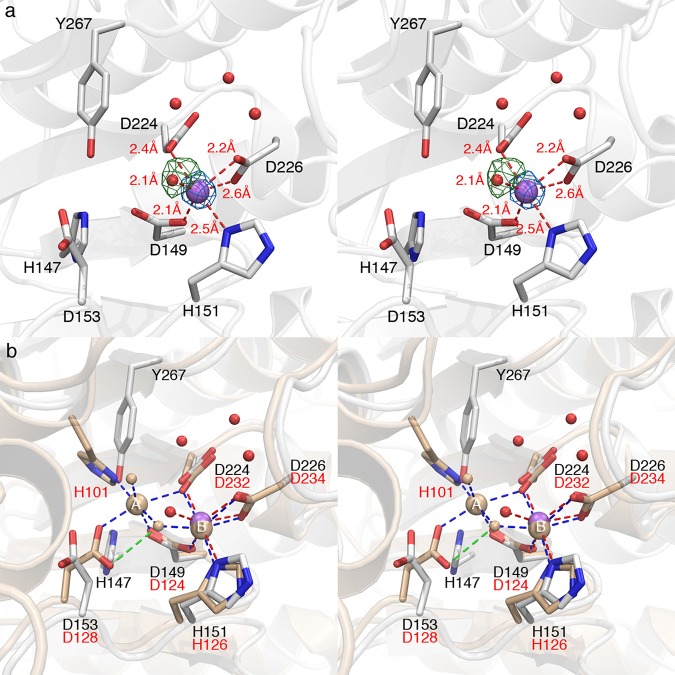

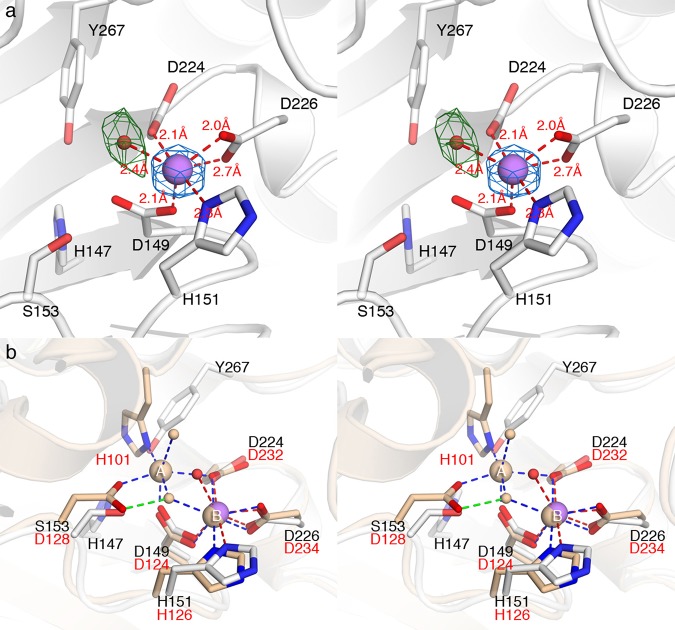

Structure and Metal Binding Activity of TbARG Mutants

Although most of the active site metal ligands are absent in TbARG, the backbone atoms of corresponding residues superimpose well with those of human arginase I,29 indicating that the overall protein scaffold is relatively unchanged in TbARG. Accordingly, we hypothesized that arginase-like metal binding sites could be reintroduced in TbARG through site-directed mutagenesis. As outlined in Materials and Methods, mutants MA2, MB, and MA2B were designed to fully reintroduce the Mn2+A, Mn2+B, and binuclear Mn2+A–Mn2+B sites, respectively, into TbARG. Our rationale in this work was that if we could successfully reintroduce a binuclear manganese cluster in TbARG, we might be able to confer a new chemical function in the putative active site. However, mutants MA2 and MA2B were not robustly expressed and exhibited poor behavior in solution; i.e., they formed aggregates that eluted with the void volume via size exclusion chromatography. Accordingly, mutants MA1, MB, and MA1B were used for further study. Recall that mutant MA1 contains S149D and S153D mutations to partially reintroduce the Mn2+A site; however, this mutant lacks a histidine metal ligand that would ordinarily complete the Mn2+A coordination polyhedron in arginase. Mutant MB contains S149D, R151H, and S226D mutations to reintroduce the Mn2+B site, and mutant MA1B contains S149D, S153D, R151H, and S226D mutations to partially reintroduce the Mn2+A site along with the fully reintroduced Mn2+B site.

Metal content analysis by ICP-AES indicates that the engineered mutants are capable of binding metal ions, in contrast with wild-type TbARG (Table 2). Mutant MB contains Mn2+, whereas mutant MA1 preferentially binds to Ni2+ and is also capable of binding Co2+ and Zn2+, but not Mn2+. To confirm the incorporation of metal ions at the designed metal binding site, we determined the crystal structures of mutant MB in its oxidized form at 3.1 Å resolution and mutants MA1 and MA1B in their reduced forms at 2.2 and 2.0 Å resolution, respectively. The overall structures of all mutants are quite similar to the structure of wild-type TbARG with rmsds of 0.31 Å for 270 Cα atoms in mutant MB, 0.38 Å for 303 Cα atoms in mutant MA1, and 0.38 Å for 304 Cα atoms in mutant MA1B.

Table 2. Metal Content As Determined by ICP-AES.

| metal:protein

molar ratio |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| protein | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn |

| expressed from minimal medium supplemented with 200 μM MnCl2 | ||||||

| mutant MA1 (S149D/S153D) | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| mutant MB (S149D/R151H/S226D) | 0.89 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| mutant MA1B (S149D/R151H/S153D/S226D) | 0.92 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| expressed from LB medium | ||||||

| wild type | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| mutant MA1 (S149D/S153D) | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.40 |

| mutant MB (S149D/R151H/S226D) | 0.74 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.20 |

| mutant MA1 (S149D/S153D)a | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

Prior to sample preparation (dialysis) for ICP-AES analysis, the sample was incubated with 0.5 mM CoCl2 and 0.5 mM NiCl2 for 30 min on ice.

The binding of Mn2+ to the engineered metal B site in mutants MB and MA1B is confirmed by the appearance of strong peaks in simulated annealing omit maps. In mutant MA1B, the Mn2+ ion is coordinated by H151 Nδ, D149 Oδ1, D224 Oδ1, D226 Oδ1, and a solvent molecule with distorted octahedral geometry (Figure 5). For mutant MB, the Mn2+ ion adopts similar coordination geometry except that the metal-bound solvent molecule is observed only in monomer A in the asymmetric unit (Figure 6); in monomer B, the corresponding solvent molecule is too far from Mn2+ to be considered an inner-sphere coordination interaction, so the metal coordination geometry is classified as square pyramidal (Figure S4 of the Supporting Information).

Figure 5.

(a) Simulated annealing omit maps of the Mn2+ ion in mutant MA1B (blue mesh, contoured at 14σ) and its nonprotein ligand (green mesh, contoured at 4σ). The Mn2+ ion is shown as a purple sphere, and water molecules are shown as small red spheres. Red dashed lines indicate metal coordination interactions. (b) Superposition of human arginase I (light yellow, PDB entry 2ZAV) with mutant MA1B. Green dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds. Metal coordination interactions in human arginase I are shown as blue dashed lines.

Figure 6.

(a) Simulated annealing omit maps of the Mn2+ ion from monomer B (blue mesh, contoured at 14σ) and its nonprotein ligand (green mesh, contoured at 3σ) in mutant MB. The Mn2+ ion is shown as a purple sphere, and water molecules are shown as small red spheres. Red dashed lines indicate metal coordination interactions. (b) Superposition of human arginase I (light yellow, PDB entry 2ZAV) with mutant MB. Green dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds. Metal coordination interactions in human arginase I are shown as blue dashed lines.

In mutants MA1B and MB, the D226 Oδ2···Mn2+ distance (2.6–2.7 Å) is too long for an inner-sphere coordination interaction. Even so, structural comparisons of TbARG mutants MA1B and MB with human arginase I show that the metal coordination geometries of the engineered metal B sites in TbARG mutants are very similar to those of the natural Mn2+B site in human arginase I (Figures 5b and 6b). However, there are differences in the position of the nonprotein metal ligand: metal-bound solvent molecules in mutants MA1B and MB deviate from the position of the metal-bridging hydroxide ion in human arginase I by 1.0 and 1.3 Å, respectively.

In contrast to the ICP-AES data, no bound Ni2+ ions are observed in the electron density maps of mutants MA1 or mutant MA1B. Inspection of the crystal structure of each mutant reveals that the side chain of D153 is not ideally oriented for metal coordination and would require conformational change to incorporate metal ions at the engineered A site; the superposition of human arginase I with mutant MA1B in Figure 5b illustrates this feature. The unfavorable orientation of D153, as well as the lack of the histidine side chain ordinarily conserved in site A, is likely responsible for the lack of a bound metal ion at the Mn2+A site. The partial metal binding behavior detected in ICP-AES measurements may very well arise from nonspecific binding to the hexahistidine tag installed at the N-terminus to allow facile protein purification. We hypothesize that the Mn2+A site must be fully reconstituted with an additional histidine ligand to reintroduce significant metal binding activity, as designed in mutant MA2. Unfortunately, this mutant was poorly behaved in solution and was not amenable to biophysical measurements.

Ligand Binding and Activity Assays

Although the putative active site of wild-type TbARG lacks the characteristic binuclear manganese cluster of an arginase-like enzyme or a single metal ion binding site like that of a histone deacetylase or polyamine deacetylase,13−15,17 it is characterized by a ∼9 Å deep cleft with negative electrostatic surface potential that could conceivably accommodate the binding of cationic amino acid ligands such as l-arginine and l-lysine (Figure 3a). Using the thermal stability shift assay described by Niesen and colleagues,32 which is based on the principle that protein thermostability increases in a protein–ligand complex, we studied the binding of 58 different ligands, including cationic amino acids such as l-arginine, l-lysine, and l-ornithine, and six different divalent metal ions (a complete list is found in Table S2 of the Supporting Information). None of the ligands tested significantly increased the melting temperature (Tm) of the protein; the largest increase was observed for d-lysine, with a ΔTm of 1.4 ± 0.2 °C; for l-lysine, ΔTm = 1.3 ± 0.2 °C, and for l-arginine, ΔTm = 0.4 ± 0.1 °C. As a point of calibration for the significance of such relatively small shifts in thermal stability, ΔTm values of ≥2 °C can generally be regarded as significant,57,58 although there can be occasional exceptions to this empirically derived threshold.59 Thus, we used X-ray crystallography as a secondary screen for binding in crystal soaking experiments with millimolar concentrations of l-lysine and l-arginine: no evidence of binding was observed. Accordingly, it is unlikely that any of the compounds listed in Table S2 of the Supporting Information are biologically relevant ligands for TbARG. We also evaluated the binding of NADPH and NADH using fluorescence spectroscopy. No changes were observed in fluorescence emission spectra upon titration of NAD(P)H into TbARG solutions, thereby ruling out any possible functional role for this cofactor.

Reasoning that a substrate might not bind tightly enough to an enzyme to yield a significantly high ΔTm value in a thermal shift assay, and hypothesizing that TbARG might have divergently evolved with a metal-independent mechanism for ureohydrolase activity, we additionally tested TbARG for arginase-like hydrolytic activity with eight guanidinium derivatives, including l-arginine, agmatine, and 3-guanidinopropionic acid. We also tested for arginine deiminase activity, formiminoglutamase activity, and lysine deacetylase activity as outlined in Materials and Methods. TbARG exhibited no catalytic activity in any of these assays. Therefore, the potential ligand binding and/or catalytic function of TbARG remains unknown.

Implications for the Loss of Metal Binding Function

While the biological function of TbARG remains undetermined, the crystal structure provides definitive confirmation that TbARG adopts the tertiary structure and quaternary structure of an arginase despite only weak similarity at the level of primary structure (amino acid sequence that is 24 and 22% identical with those of rat and human arginases I, respectively). The crystal structure clearly shows that wild-type TbARG lacks metal ligands and metal ions normally characteristic of an arginase-like enzyme. However, we demonstrate that metal binding activity can be reintroduced into the putative active site by mutagenesis. However, the question of what chemical or biological function wild-type TbARG serves in the life cycle of T. brucei remains.

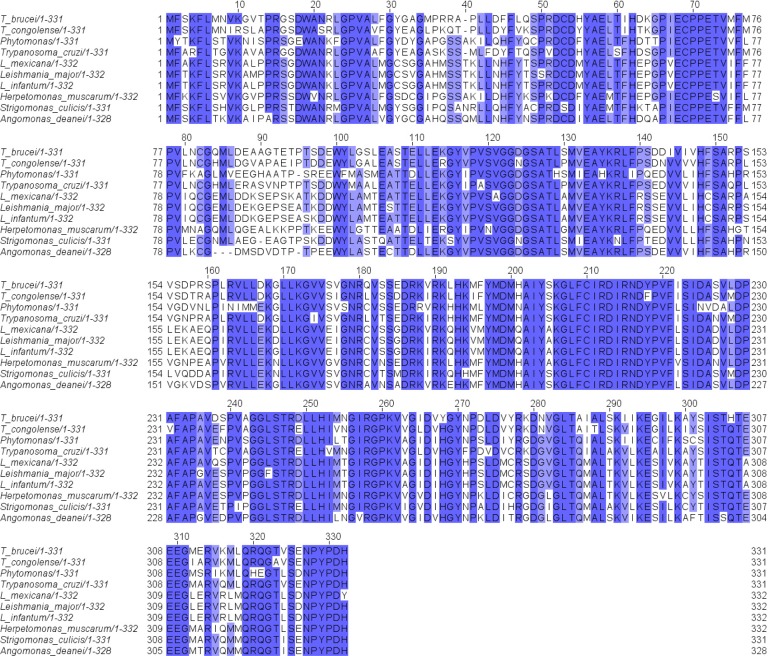

The genome of T. brucei is unique in that it encodes no arginase-like protein except for TbARG;60 in comparison, the genome of another parasite, L. mexicana,61 encodes a TbARG-like protein (related by a 68% identical amino acid sequence) as well as a functional arginase.16 The TbARG is not syntenic to the functional Leishmania arginase. Interestingly, a TbARG-like protein with similarly high levels of amino acid sequence identity is found in other parasites that infect animals, insects, and plants (Figure 7). Like TbARG, none of these proteins contain an arginase-like metal binding site, yet residues in the putative active site are largely conserved.

Figure 7.

Alignment of the amino acid sequence of TbARG (T_brucei/1–331) with those of similar proteins from other parasites.

On the basis of the amino acid sequence alignment in Figure 7, potential functional residues in the putative active site of TbARG would be highly conserved and include H147, D224, and Y267. The conservation of such polar residues could support a variety of chemical functions in catalysis. For example, the carboxylate side chain of D224 might serve as general base (although this residue appears as N224 in Phytomonas, where the asparagine side chain would be less effective as a general base), and the imidazole side chain of H147 might serve as a general acid. It is interesting to note that Y267 appears as a histidine in all other homologues shown in Figure 7, perhaps implying that this residue, too, might be capable of serving in some catalytic function as a general acid. However, the identity of a substrate for any catalytic function remains elusive. Analysis of TbARG using structural bioinformatics approaches has not provided any additional clues regarding a potential biological function. For example, the COFACTOR server62 returns only arginases and arginase-like enzymes, all of which contain intact binuclear manganese clusters.

While it is perhaps unsatisfying that a catalytic function cannot be assigned to TbARG, the fact that T. brucei contains this protein instead of a functional arginase is nonetheless informative. Functional arginase enzymes in other parasites generate a cellular pool of l-ornithine that is subsequently converted into putrescine by ornithine decarboxylase, a key step in polyamine biosynthesis.8 The fact that T. brucei contains a functional ornithine decarboxylase,63,64 but not a functional arginase, indicates that the l-ornithine utilized by T. brucei for polyamine biosynthesis must derive from an alternative pathway. For example, l-ornithine could derive from acetyl-l-ornithine, given that the T. brucei genome60 encodes a putative acetylornithine deacetylase (ArgE; gene Tb927.1.3000 on chromosome 1). However, the T. brucei genome lacks ArgA–ArgD enzymes, which in other organisms function with ArgE to generate l-ornithine from l-glutamate (ArgE also functions in prokaryotic l-arginine biosynthesis).65,66 Thus, lacking any other source of l-ornithine for polyamine biosynthesis, T. brucei must import l-ornithine from its host to maintain viability. This is corroborated by transport assays42 showing that T. brucei is capable of importing l-ornithine with a Km of 310 μM and a Vmax of 15.9 pmol (107 cells)−1 min–1. With l-ornithine levels in human blood and cerebrospinal fluid at 54–100 and 5 μM, respectively, T. brucei is able to directly transport l-ornithine from its environment to fulfill its requirements, signaling that T. brucei does not require a functional arginase.

The TbARG Gene Is Nonessential to Bloodstream-Form T. brucei and Appears To Have No Role in l-Arginine Metabolism

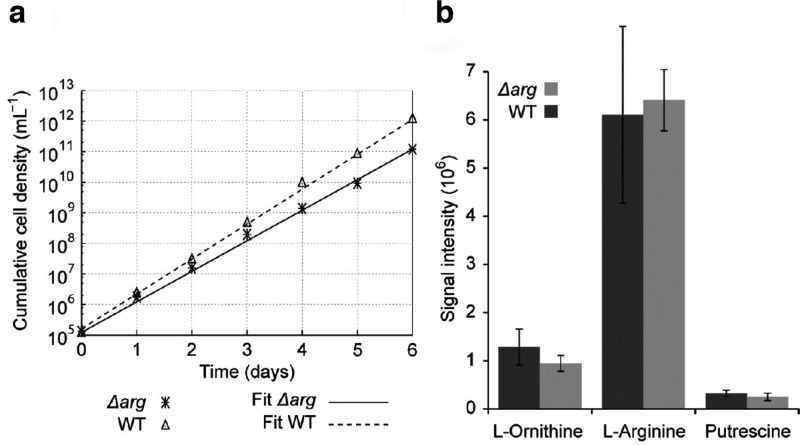

Both alleles of the TbARG gene were removed using gene replacement. PCR analysis revealed that both alleles were successfully removed from the genome. The Δarg cells grew at a rate only marginally slower than that of the wild type (Figure 8a), indicating that the gene is not essential to these parasites, in contrast with Leishmania, in which a Δarg strain required supplementation with l-ornithine.16 Using an untargeted metabolomics approach (i.e., a comprehensive analysis of all small molecule metabolites) to compare T. brucei Δarg and the wild type, no difference in the abundance of l-arginine, l-ornithine, or any of the polyamines such as putrescine was noted (Figure 8b), confirming the fact that TbARG is not an arginase. A combined total of 127 putatively identified metabolites were significantly changed (FDR < 0.05) in the Δarg strain (Table S3 of the Supporting Information); however, these differences did not provide a clear suggestion about the in vivo role of TbARG.

Figure 8.

(a) Growth of the Δarg strain compared to wild-type T. brucei. Cultures were daily diluted to 105 cells mL–1, and the resulting cumulative cell densities were plotted. An exponential fit is shown, yielding doubling times of 6.2 h for the wild type and 7.4 h for Δarg. (b) Signal intensities of l-arginine, l-ornithine, and putrescine as measured by liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. No significant difference is detected between the wild type and Δarg.

Concluding Remarks

This work demonstrates that T. brucei cannot generate its own source of l-ornithine through the activity of a functional arginase enzyme, even though the TbARG protein adopts the characteristic α/β arginase fold. Nevertheless, site-directed mutagenesis experiments demonstrate that metal binding behavior can be easily reintroduced into the TbARG protein, so the α/β scaffold appears to be readily evolved by nature or by design. Amino acid residues in the putative active site of TbARG are highly conserved in similar proteins from other parasites (Figure 7), so a common active site architecture presumably evolved to serve a common, cryptic function. We are continuing our search for this function through chemical and biological approaches and will report our results in due course.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Edward D’Antonio for many helpful discussions. We are grateful to Brunda Nijagal for assistance with metabolomics analysis and Kate Beckham for cloning the TbARG gene. Additionally, we thank the Molecular Biology Core Facility (National Institutes of Health Grant P30-DK050306) at the Center of Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases (Department of Gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania) for access to the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system. Finally, we thank the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory (beamline X29) for access to X-ray crystallographic data collection facilities.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BME

β-mercaptoethanol

- FDR

false discovery rate

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- ICP-AES

inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry

- LB

lysogeny broth

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- SAD

single-wavelength anomalous dispersion

- Se-Met

selenomethionine

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride.

Supporting Information Available

Primers used for PCR mutagenesis and the generation of the Δarg mutant, significantly changed metabolites in the Δarg strain, thermal stability shift assay results, Bijvoet difference Fourier map illustrating Se-Met residues, comparison of TbARG trimer assembly with that of P. falciparum arginase, and simulated annealing omit map of monomer B in TbARG mutant MB. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Accession Codes

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank as the following entries: wild-type TbARG (oxidized), 4RHK; wild-type TbARG (reduced), 4RHJ; Se-Met TbARG (reduced), 4RHI; S149D/S153D TbARG (mutant MA1, reduced), 4RHQ; S149D/R151H/S226D TbARG (mutant MB, oxidized), 4RHL; S149D/R151H/S153D/S226D TbARG (mutant MA1B, reduced), 4RHM.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM49758.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Barrett M. P.; Burchmore R. J. S.; Stich A.; Lazzari J. O.; Frasch A. C.; Cazzulo J. J.; Krishna S. (2003) The trypanosomiases. Lancet 362, 1469–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun R.; Blum J.; Chappuis F.; Burri C. (2010) Human African trypanosomiasis. Lancet 375, 148–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett M. P. (2006) The rise and fall of sleeping sickness. Lancet 367, 1377–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlamb A. H. (2003) Chemotherapy of human African trypanosomiasis: Current and future prospects. Trends Parasitol. 19, 488–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun R.; Don R.; Jacobs R. T.; Wang M. Z.; Barrett M. P. (2011) Development of novel drugs for human African trypanosomiasis. Future Microbiol. 6, 677–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simarro P. P.; Franco J.; Diarra A.; Ruiz Postigo J. A.; Jannin J. (2012) Update on field use of the available drugs for the chemotherapy of human African trypanosomiasis. Parasitology 139, 842–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Hua S.-b.; Wang C. C.; Gottesdiener K. M. (1998) Trypanosoma brucei brucei: Characterization of an ODC null bloodstream form mutant and the action of α-difluoromethylornithine. Exp. Parasitol. 88, 255–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heby O.; Roberts S. C.; Ullman B. (2003) Polyamine biosynthetic enzymes as drug targets in parasitic protozoa. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31, 415–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishin N. V.; Osterman A. L.; Brooks H. B.; Phillips M. A.; Goldsmith E. J. (1999) X-ray structure of ornithine decarboxylase from Trypanosoma brucei: The native structure and the structure in complex with α-difluoromethylornithine. Biochemistry 38, 15174–15184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi C. J.; Nathan H. C.; Hunter S. H.; McCann P. P.; Sjoerdsma A. (1980) Polyamine metabolism: A potential therapeutic target in trypanosomes. Science 210, 332–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casero R. A.; Marton L. J. (2007) Targeting polyamine metabolism and function in cancer and other hyperproliferative diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 6, 373–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris S. M. Jr. (2007) Arginine metabolism: Boundaries of our knowledge. J. Nutr. 137, 1602S–1609S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson D. W.; Cox J. D. (1999) Catalysis by metal-activated hydroxide in zinc and manganese metalloenzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 33–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash D. E., Cox J. D., and Christianson D. W. (1999) Arginase: A binuclear manganese metalloenzyme. In Manganese and Its Role in Biological Processes (Sigel A., and Sigel H., Eds.) Volume 37 of Metal Ions in Biological Systems, pp 407–428, Marcel Dekker, New York. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson D. W. (2005) Arginase: Structure, mechanism, and physiological role in male and female sexual arousal. Acc. Chem. Res. 38, 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. C.; Tancer M. J.; Polinsky M. R.; Gibson K. M.; Heby O.; Ullman B. (2004) Arginase plays a pivotal role in polyamine precursor metabolism in Leishmania: Characterization of gene deletion mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23668–23678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi P. M.; Cole K. A.; Dowling D. P.; Christianson D. W. (2011) Structure, mechanism, and inhibition of histone deacetylases and related metalloenzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21, 735–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z.; Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape T.; Schneider T. R. (2004) HKL2MAP: A graphical user interface for phasing with SHELX programs. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 37, 843–844. [Google Scholar]

- Adams P. D.; Afonine P. V.; Bunkóczi G.; Chen V. B.; Davis I. W.; Echols N.; Headd J. J.; Hung L.-W.; Kapral G. J.; Grosse-Kunstleve R. W.; McCoy A. J.; Moriarty N. W.; Oeffner R.; Read R. J.; Richardson D. C.; Richardson J. S.; Terwilliger T. C.; Zwart P. H. (2010) PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P.; Lohkamp B.; Scott W. G.; Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy A. J.; Grosse-Kunstleve R. W.; Storoni L. C.; Read R. J. (2005) Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr. D61, 458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn M. D.; Ballard C. C.; Cowtan K. D.; Dodson E. J.; Emsley P.; Evans P. R.; Keegan R. M.; Krissinel E. B.; Leslie A. G. W.; McCoy A.; McNicholas S. J.; Murshudov G. N.; Pannu N. S.; Potterton E. A.; Powell H. R.; Read R. J.; Vagin A.; Wilson K. S. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D67, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla J. E.; Yeates T. O. (2003) A statistic for local intensity differences: robustness to anisotropy and pseudo-centering and utility for detecting twinning. Acta Crystallogr. D59, 1124–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeates T. O. (1988) Simple statistics for intensity data from twinned specimens. Acta Crystallogr. A44, 142–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redinbo M. R.; Yeates T. O. (1993) Structure determination of plastocyanin from a specimen with a hemihedral twinning fraction of one-half. Acta Crystallogr. D49, 375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeates T. O. (1997) Detecting and overcoming crystal twinning. Methods Enzymol. 276, 344–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. D.; Kim N. N.; Traish A. M.; Christianson D. W. (1999) Arginase-boronic acid complex highlights a physiological role in erectile function. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 1043–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Costanzo L.; Sabio G.; Mora A.; Rodriguez P. C.; Ochoa A. C.; Centeno F.; Christianson D. W. (2005) Crystal structure of human arginase I at 1.29-Å resolution and exploration of inhibition in the immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 13058–13063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A.; MacArthur M. W.; Moss D. S.; Thornton J. M. (1993) PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E.; Henrick K. (2007) Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesen F. H.; Berglund H.; Vedadi M. (2007) The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2212–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald R. M. (1945) Colorimetric determination of urea. J. Biol. Chem. 157, 507–508. [Google Scholar]

- Knipp M.; Vašák M. (2000) A colorimetric 96-well microtiter plate assay for the determination of enzymatically formed citrulline. Anal. Biochem. 286, 257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai Y.; Dugery R. J.; Healy D.; Christianson D. W. (2013) Formiminoglutamase from Trypanosoma cruzi is an arginase-like manganese metalloenzyme. Biochemistry 52, 9294–9309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creek D. J.; Nijagal B.; Kim D.-H.; Rojas F.; Matthews K. R.; Barrett M. P. (2013) Metabolomics guides rational development of a simplified cell culture medium for drug screening against Trypanosoma brucei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 2768–2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross M.; Kieft R.; Sabatini R.; Dirks-Mulder A.; Chaves I.; Borst P. (2002) J-binding protein increases the level and retention of the unusual base J in trypanosome DNA. Mol. Microbiol. 46, 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann Burkard G.; Jutzi P.; Roditi I. (2011) Genome-wide RNAi screens in bloodstream form trypanosomes identify drug transporters. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 175, 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C. P.; Wong P. E.; Burchmore R. J.; de Koning H. P.; Barrett M. P. (2011) Trypanocidal furamidine analogues: Influence of pyridine nitrogens on trypanocidal activity, transport kinetics, and resistance patterns. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 2352–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- t’Kindt R.; Jankevics A.; Scheltema R. A.; Zheng L.; Watson D. G.; Dujardin J.-C.; Breitling R.; Coombs G. H.; Decuypere S. (2010) Towards an unbiased metabolic profiling of protozoan parasites: Optimization of a Leishmania sampling protocol for HILIC-Orbitrap analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 398, 2059–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess K.; Creek D.; Dewsbury P.; Cook K.; Barrett M. P. (2011) Semi-targeted analysis of metabolites using capillary-flow ion chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 25, 3447–3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent I. M.; Creek D. J.; Burgess K.; Woods D. J.; Burchmore R. J. S.; Barrett M. P. (2012) Untargeted metabolomics reveals a lack of synergy between Nifurtimox and Eflornithine against Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 6(5), e1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheltema R. A.; Jankevics A.; Jansen R. C.; Swertz M. A.; Breitling R. (2011) PeakML/mzMatch: A file format, Java library, R library, and tool-chain for mass spectrometry data analysis. Anal. Chem. 83, 2786–2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creek D. J.; Jankevics A.; Burgess K. E. V.; Breitling R.; Barrett M. P. (2012) IDEOM: An Excel interface for analysis of LC-MS-based metabolomics data. Bioinformatics 28, 1048–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner L. W.; Amberg A.; Barrett D.; Beale M. H.; Beger R.; Daykin C. A.; Fan T. W.-M.; Fiehn O.; Goodacre R.; Griffin J. L.; Hankemeier T.; Hardy N.; Harnly J.; Higashi R.; Kopka J.; Lane A. N.; Lindon J. C.; Marriott P.; Nicholls A. W.; Reily M. D.; Thaden J. J.; Viant M. R. (2007) Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis. Metabolomics 3, 211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitling R.; Armengaud P.; Amtmann A.; Herzyk P. (2004) Rank products: A simple, yet powerful, new method to detect differentially regulated genes in replicated microarray experiments. FEBS Lett. 573, 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewley M. C.; Jeffrey P. D.; Patchett M. L.; Kanyo Z. F.; Baker E. N. (1999) Crystal structures of Bacillus caldovelox arginase in complex with substrate and inhibitors reveal new insights into activation, inhibition and catalysis in the arginase superfamily. Structure 7, 435–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumarevel T. S., Karthe P., Kuramitsu S., and Yokoyama S. (2009) Crystal structure of the arginase from Thermus thermophilus. PDB entry 2EF4, 10.2210/pdb2ef4/pdb. [DOI]

- Elkins J. M.; Clifton I. J.; Hernandez H.; Doan L. X.; Robinson C. V.; Schofield C. J.; Hewitson K. S. (2002) Oligomeric structure of proclavaminic acid amidino hydrolase: Evolution of a hydrolytic enzyme in clavulanic acid biosynthesis. Biochem. J. 366, 423–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn H. J.; Kim K. H.; Lee J.; Ha J.-Y.; Lee H. H.; Kim D.; Yoon H.-J.; Kwon A.-R.; Suh S. W. (2004) Crystal structure of agmatinase reveals structural conservation and inhibition mechanism of the ureohydrolase superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 50505–50513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. J.; Kim D. J.; Kim H. S.; Lee B. I.; Yoon H.-J.; Yoon J. Y.; Kim K. H.; Jang J. Y.; Im H. N.; An D. R.; Song J.-S.; Kim H.-J.; Suh S. W. (2011) Crystal structures of Pseudomonas aeruginosa guanidinobutyrase and guanidinopropionase, members of the ureohydrolase superfamily. J. Struct. Biol. 175, 329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling D. P.; Ilies M.; Olszewski K. L.; Portugal S.; Mota M. M.; Llinás M.; Christianson D. W. (2010) Crystal structure of arginase from Plasmodium falciparum and implications for l-arginine depletion in malarial infection. Biochemistry 49, 5600–5608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanyo Z. F.; Scolnick L. R.; Ash D. E.; Christianson D. W. (1996) Structure of a unique binuclear manganese cluster in arginase. Nature 383, 554–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L.; Rosenström P. (2010) Dali server: Conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling D. P.; Costanzo L.; Gennadios H. A.; Christianson D. W. (2008) Evolution of the arginase fold and functional diversity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2039–2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishova E. Y.; Di Costanzo L.; Emig F. A.; Ash D. E.; Christianson D. W. (2009) Probing the specificity determinants of amino acid recognition by arginase. Biochemistry 48, 121–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson U. B.; Hallberg B. M.; DeTitta G. T.; Dekker N.; Nordlund P. (2006) Thermofluor-based high-throughput stability optimization of proteins for structural studies. Anal. Biochem. 357, 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani S. E.; Frank A. M.; Collart F. R. (2008) Functional assignment of solute-binding proteins of ABC transporters using a fluorescence-based thermal shift assay. Biochemistry 47, 13974–13984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre H. L.; Blundell T. L.; Abell C.; Ciulli A. (2013) Integrated biophysical approach to fragment screening and validation for fragment-based lead discovery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 12984–12989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berriman M.; Ghedin E.; Hertz-Fowler C.; Blandin G.; Renauld H.; Bartholomeu D. C.; Lennard N. J.; Caler E.; Hamlin N. E.; Haas B.; Böhme U.; Hannick L.; Aslett M. A.; Shallom J.; Marcello L.; Hou L.; Wickstead B.; Alsmark U. C.; Arrowsmith C.; Atkin R. J.; Barron A. J.; Bringaud F.; Brooks K.; Carrington M.; Cherevach I.; Chillingworth T. J.; Churcher C.; Clark L. N.; Corton C. H.; Cronin A.; Davies R. M.; Doggett J.; Djikeng A.; Feldblyum T.; Field M. C.; Fraser A.; Goodhead I.; Hance Z.; Harper D.; Harris B. R.; Hauser H.; Hostetler J.; Ivens A.; Jagels K.; Johnson D.; Johnson J.; Jones K.; Kerhornou A. X.; Koo H.; Larke N.; Landfear S.; Larkin C.; Leech V.; Line A.; Lord A.; Macleod A.; Mooney P. J.; Moule S.; Martin D. M.; Morgan G. W.; Mungall K.; Norbertczak H.; Ormond D.; Pai G.; Peacock C. S.; Peterson J.; Quail M. A.; Rabbinowitsch E.; Rajandream M. A.; Reitter C.; Salzberg S. L.; Sanders M.; Schobel S.; Sharp S.; Simmonds M.; Simpson A. J.; Tallon L.; Turner C. M.; Tait A.; Tivey A. R.; Van Aken S.; Walker D.; Wanless D.; Wang S.; White B.; White O.; Whitehead S.; Woodward J.; Wortman J.; Adams M. D.; Embley T. M.; Gull K.; Ullu E.; Barry J. D.; Fairlamb A. H.; Opperdoes F.; Barrell B. G.; Donelson J. E.; Hall N.; Fraser C. M.; Melville S. E.; El-Sayed N. M. (2005) The genome of the African trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei. Science 309, 416–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslett M.; Aurrecoechea C.; Berriman M.; Brestelli J.; Brunk B. P.; Carrington M.; Depledge D. P.; Fischer S.; Gajria B.; Gao X.; Gardner M. J.; Gingle A.; Grant G.; Harb O. S.; Heiges M.; Hertz-Fowler C.; Houston R.; Innamorato F.; Iodice J.; Kissinger J. C.; Kraemer E.; Li W.; Logan F. J.; Miller J. A.; Mitra S.; Myler P. J.; Nayak V.; Pennington C.; Phan I.; Pinney D. F.; Ramasamy G.; Rogers M. B.; Roos D. S.; Ross C.; Sivam D.; Smith D. F.; Srinivasamoorthy G.; Stoeckert C. J. Jr.; Subramanian S.; Thibodeau R.; Tivey A.; Treatman C.; Velarde G.; Wang H. (2010) TriTrypDB: A functional genomic resource for the Trypanosomatidae. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D457–D462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A.; Zhang Y. (2012) Recognizing protein-ligand binding sites by global structural alignment and local geometry refinement. Structure 20, 987–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M. A.; Coffino P.; Wang C. C. (1987) Cloning and sequencing of the ornithine decarboxylase gene from Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 8721–8727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M. A.; Coffino P.; Wang C. C. (1988) Trypanosoma brucei ornithine decarboxylase: Enzyme purification, characterization, and expression in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 17933–17941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. E. (1985) Conversion of glutamate to ornithine and proline: Pyrroline-5-carboxylate, a possible modulator of arginine requirements. J. Nutr. 115, 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor W. C.; Swierczek S. I.; Bennett B.; Holz R. C. (2005) argE-Encoded N-acetyl-l-ornithine deacetylase from Escherichia coli contains a dinuclear metalloactive site. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14100–14107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W.; Sander C. (1983) Dictionary of protein secondary structure: Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22, 2577–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker N. A.; Sept D.; Joseph S.; Holst M. J.; McCammon J. A. (2001) Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 10037–10041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.