Abstract

HIV drug resistance continues to emerge; consequently, there is an urgent need to develop next generation antiretroviral therapeutics.1 Here we report on the structural and kinetic effects of an HIV protease drug resistant variant with the double mutations Gly48Thr and Leu89Met (PRG48T/L89M), without the stabilizing mutations Gln7Lys, Leu33Ile, and Leu63Ile. Kinetic analyses reveal that PRG48T/L89M and PRWT share nearly identical Michaelis–Menten parameters; however, PRG48T/L89M exhibits weaker binding for IDV (41-fold), SQV (18-fold), APV (15-fold), and NFV (9-fold) relative to PRWT. A 1.9 Å resolution crystal structure was solved for PRG48T/L89M bound with saquinavir (PRG48T/L89M-SQV) and compared to the crystal structure of PRWT bound with saquinavir (PRWT-SQV). PRG48T/L89M-SQV has an enlarged active site resulting in the loss of a hydrogen bond in the S3 subsite from Gly48 to P3 of SQV, as well as less favorable hydrophobic packing interactions between P1 Phe of SQV and the S1 subsite. PRG48T/L89M-SQV assumes a more open conformation relative to PRWT-SQV, as illustrated by the downward displacement of the fulcrum and elbows and weaker interatomic flap interactions. We also show that the Leu89Met mutation disrupts the hydrophobic sliding mechanism by causing a redistribution of van der Waals interactions in the hydrophobic core in PRG48T/L89M-SQV. Our mechanism for PRG48T/L89M-SQV drug resistance proposes that a defective hydrophobic sliding mechanism results in modified conformational dynamics of the protease. As a consequence, the protease is unable to achieve a fully closed conformation that results in an expanded active site and weaker inhibitor binding.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) remains a serious global health concern. In 2012, 35.3 million people were living with HIV/AIDS worldwide and 1.6 million people died from the disease.2 The use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) that involves combinations of reverse transcriptase and protease inhibitors can lead to a reduction in viral load to nearly undetectable levels in infected individuals.3,4 However, the major challenge limiting current therapy is the rapid evolution of drug resistance resulting from the high mutation rate caused by the absence of a proofreading function in HIV reverse transcriptase.5 Consequently, there is a continuing need for next generation PIs with efficacy against drug resistant strains of HIV. This work will add to the growing amount of information on resistance mechanisms with an aim toward new drug development.

This study examines the effect of drug resistant mutations on HIV-1 protease, which is involved in the processing of the Gag and Gag-Pol viral polyproteins. These processing events allow the virus to efficiently form new virion particles and infect new host cells.6 Consequently, PR is a valuable drug target since inhibition of PR activity results in immature noninfectious virions.7,8 We utilized the Stanford University HIV Drug Resistance Database to determine novel drug resistant mutations that may develop in PR in response to ritonavir boosted protease inhibitor therapy. An analysis of the database facilitated the determination of a previously uncharacterized, SQV/RTV resistant variant, Gly48Thr/Leu89Met (PRG48T/L89M). Residue Gly48 is located in the flaps of the protease and contributes to the formation of the S2/S2′ and S3/S3′ binding pockets of the enzyme;9 however, residue Leu89 does not make contact with the inhibitor directly. Instead, residue Leu89 is located in the hydrophobic core of PR which is distal to the active site.

While the effect of primary mutations on inhibitor binding can be more easily rationalized because those amino acids make direct contact with the inhibitor, many PR mutations are secondary and are found outside of the active site. How these mutations transmit their deleterious effect on inhibitor binding in the active site is less clear.10 Several studies suggest that secondary mutations interfere with the conformational equilibrium between the open and closed forms of PR.10−12 Since PIs are rigid and are designed to bind the closed conformation, mutations that shift the conformational equilibrium of PR to the open form may result in weaker PI binding.10

Mutations of both Gly48 and Leu89 result in PR drug resistance. Gly48Val, a primary mutation, occurs in response to SQV treatment and less often from IDV and LPV treatment13−16 and confers high-level resistance to SQV, intermediate-level resistance to ATV, and low-level resistance to NFV, IDV, and LPV.17−19 Gly48Met occurs in patients who have received multiple PIs and results in a similar resistance profile as Gly48Val.17,20−22 Gly48Ala/Ser/Thr/Gln/Leu are extremely rare PR mutations23 that occur primarily in viruses containing multiple PI-resistance mutations and appear to have similar but weaker effects on PI susceptibility than do Gly48Val and Gly48Met.18 Leu89Val, a secondary mutation, is an accessory mutation and is located outside the active site in the hydrophobic core of PR and occurs in response to treatment with IDV, NFV, FPV, and DRV. It reduces susceptibility to these inhibitors.

Several groups have investigated the conformational changes of PR through the use of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.11,24 A general mechanism for flap opening and closing has been proposed by Hornak et al. in which flap opening occurs through a concerted downward motion of the cantilever (residues 58–75), fulcrum (residues 11–22), and flap region (residues 39–57) that results in the upward motion of the flaps and domain rotation around the region near the dimer interface (Figure 1A).24 Specifically, the flap elbows and exposed ends of the fulcrum and cantilever move down and toward the terminal β-sheet dimer interface. Additionally, residues in the hydrophobic core region have been proposed to initiate conformational changes in the protease that facilitates flap opening and closing.

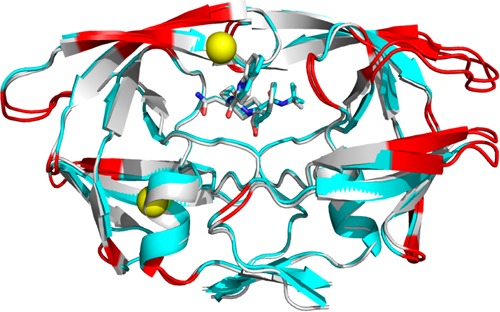

Figure 1.

(A) Superposition of the crystal structures for the closed (1HVR) and open (2PC0) forms of HIV PR. The ligand for the closed form has been omitted for clarity. The different mobile regions of PR are color coded with the open form in lighter shades: elbow flaps (39–57; blue), cantilever (58–75; orange), and fulcrum (11–22; red). Black arrows indicate proposed directions of movements of these regions during flap opening. (B) 90° rotation of PR shown in (A). Only monomer B is shown for simplicity. Green arrows represent regions of hydrophobic sliding during flap opening and closing. (C) Crystal structure of PRG48T/L89M-SQV (cyan) superposed with PRWT-SQV (1HXB) (silver). Red indicates regions where the r.m.s.d. of Cα carbons is >0.75 Å. Yellow spheres indicate the locations of the mutations Gly48Thre and Leu89Met. Mutations are show in only one monomer for clarity.

Based upon molecular dynamics simulations, 19 residues have been defined by Foulkes-Murzycki et al. to potentially facilitate the opening of the active site cavity to allow for substrate binding.11 This mechanism is referred to as the “hydrophobic sliding” mechanism and proposes that one surface of PR slides across another surface via the exchange of van der Waals (vdw) contacts between hydrophobic side chains such that the hydrogen bonding network within the core is conserved11,12 (Figure 1B). Importantly, many residues within the hydrophobic core are associated with drug resistance, and mutations in the core likely affect the dynamic properties of HIV PR and potentially affect the ability of PR to bind inhibitors and substrates.11 Notably, the hydrophobic sliding mechanism is supported experimentally by Mittal et al. by showing that disulfide cross-links (Gly16Cys/Leu38Cys) that exert a conformational restraint on the hydrophobic core compromise protease activity, and that activity can be largely restored through reduction of the cross-links.12

Here we report on the cocrystal structure of HIV-1 PR with the double mutation Gly48Thr/Leu89Met bound with saquinavir (SQV) (PRG48T/L89M-SQV) in the active site cavity. The side chains of 7 of the 19 residues in the hydrophobic core of PRG48T/L89M-SQV as defined by Foulkes-Murzycki et al.11 undergo rotation. This results in the loss and redistribution of vdw interactions relative to the previously determined cocrystal structure of wild-type HIV-1 PR bound with SQV (PRWT-SQV) by Krohn et al.25 We propose that the modified vdw interactions result in a defective hydrophobic sliding mechanism, leading to the inability of PRG48T/L89M-SQV to achieve a fully closed conformation, thus resulting in an expanded active site and weaker flap interactions. This enhances the deleterious effects of the primary mutation, Gly48Thr, on inhibitor binding.

Materials and Methods

Variant Selection

To determine mutations that result in drug resistance, the Stanford University HIV Drug Resistance Database was utilized. Using the Detailed Protease Inhibitor Query function, two protease inhibitors (ritonavir + saquinavir) were selected as being received by patients with HIV-1 subtype B. This populates PR sequences containing mutations in all patient isolates deposited in the database that have been treated with only ritonavir + saquinavir. Next, to rule out mutations arising from each single inhibitor, the same exercise was performed with each single inhibitor. Mutations resulting from each single inhibitor treatment were deleted from the list of mutations from double inhibitor treatment. The remaining mutations were deduced to have arisen from the double drug selection pressure.

Mutagenesis and Expression of Protease

A complete description of the cloning, expression, and purification procedures can be found in Ido et al. and Goodenow et al.19,26 In brief, the HIV-1 protease gene for HIV B was subcloned into the pET23a expression vector (Novagen). For the HIV B Gly48Thr/Leu89Met variant the codon optimized DNA containing the desired mutations was synthesized (DNA 2.0), subcloned in the expression vector, pJExpress, and sequenced by DNA 2.0. HIV B and HIV B Gly48Thr/Leu89Met protease constructs were transformed into the E. coli strain BL21 Star DE3 plysS and E. coli strain BL21 cells (Invitrogen), respectively. Protease expression in bacteria was initiated when the OD600 reached 0.6 by addition of 1 mM IPTG to a culture grown at 37 °C in M9Media (6.8 g Na2HPO4, 3 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g NaCl, 1 g (NH4)2SO4, and 5 g casamino acids were autoclaved together in 987 mL of H2O, then 1 mL of 0.1 M CaCl2, 2 mL of 1.0 M MgSO4, 10 mL of 20% glucose were added). For HIV B protease, 50 μg/L of ampicillin and chloramphenicol were added. For HIV B Gly48Thr/Leu89Met, 50 μg/L of kanamycin was added. After 3 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 16 000 × g for 5 min and resuspended in TN buffer (0.05 M Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.001 M MgCl2, pH 7.4). Inclusion bodies containing the protease were isolated by centrifugation through a 27% sucrose cushion, following cell disruption by French Pressure Cell treatment. The inclusion bodies were solubilized in 8 M urea and the protease was refolded by dialysis against 0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer (0.05 M Na2HPO4, 0.005 M EDTA, 0.3 M NaCl, and 0.001 M DTT, pH 7.3). The protease was purified through ammonium sulfate precipitation and gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex 75 16/60 column (Amersham Pharmacia) attached to a FPLC LCC 500 Plus (Pharmacia). The protease was eluted using potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM K2HPO4, 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, pH 7.3).

Protease Activity and Inhibition Constants

The Michaelis–Menten constants kcat, Km, and kcat/Km, as well as the inhibition constant, Ki, were determined for PRWT and PRG48T/L89M, as previously described.10 The chromogenic substrate Lys-Ala-Arg-Val-Leu*Nph-Glu-Ala-NLe-Gly was used to determine the catalytic activity of each variant at 37 °C in sodium acetate buffer (0.05 M NaOAc, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.002 M EDTA, 0.001 M DTT, pH 4.7).10,27Ki values for all inhibitors were measured under the same conditions. Cleavage of the substrate was monitored using a Cary 50 Bio UV–vis spectrophotometer equipped with a 18-cell sample handling system. The inhibition constant, Ki, was determined by monitoring the inhibition of hydrolysis of the chromogenic substrate as described by Bhatt et al.28

Crystallization of Protein–Inhibitor Complex

The PRG48T/L89M buffer was exchanged to 50 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT, pH 4.7 during concentration to 3.5 mg/mL. SQV (obtained from the NIH Research and Reference Reagent Resources Program) was dissolved at a concentration of 150 mM in 100% DMSO and mixed with protease in a molar ratio of 10:1 with a 1% final DMSO concentration. The inhibitor and enzyme were allowed to equilibrate for 18 h at 4 °C after which precipitated material was removed by centrifugation at 10 000 × g at 4 °C. Crystallization trials were conducted using the hanging drop vapor-diffusion method, screening various conditions from Crystal Screen Kit 1 (Hampton Research). Crystal drops were prepared by mixing 2 μL enzyme–inhibitor solution with 2 μL reservoir solution and were equilibrated against 1 mL reservoir solution at 293 K. The enzyme–inhibitor complex mixed with reservoir solution containing Hampton Research HR2–110 #40 (0.1 M sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate, pH 5.6, 20% v/v 2-propanol, 20% w/v PEG 4000) resulted in diffraction quality crystals within 2 weeks.

Data Collection, Structure Determination, and Refinement

Data was collected using an RU-H3R rotating Cu anode (λ = 1.5148 Å) operating at 50 kV and 22 mA utilizing an R-Axis IV+2 image plate detector (Rigaku, USA). Data was processed using HKL2000(29) and indexed to the othrorhombic space group, P212121 with 96.5% completeness for all reflections. Initial phases were determined using Molecular Replacement with PDB 1HXB as a search model. Calculations for Molecular Replacement and final refinements were performed using the Phenix(30) suite of programs. The final structure was refined to a maximum resolution of 1.9 Å and Rcryst and Rfree of 0.187 and 0.242, respectively (Table 1). Phenix was also used to generate ligand restraint files for SQV. Electron density maps and molecular models including coordinate files for ligands were viewed and constructed using Coot.31,32 The quality of the structure was validated with PROCHECK.33 The structure conforms to standard ψ φ geometry. Crystal structures of PRG48T/L89M bound with saquinavir (PRG48T/L89M-SQV) (PDB ID code 4QGI) and HIV PR bound with saquinavir (PRWT-SQV) (PDB code 1HXB) were superimposed on all Cα atoms using the LSQAB34 alignment program in the CCP4 software package.35 The volumes of the active sites of both PR’s were calculated using CASTp.36 The inhibitor and water molecules were removed before calculating the volume of the active site. Hydrogen bonds were assigned using HBPLUS.37 Van der Waals interactions were assigned when two nonpolar atoms were within 4.2 Å of each other. Only vdw distance changes of ≥1 Å were considered significant for the structural analysis. Figures were made using PyMOL.38

Table 1. Data Collection and Statistics.

| PRG48T/L89M-SQVa | |

|---|---|

| Space Group | P212121 (a = 28.9 Å, b = 67.2 Å, c = 93.5 Å) |

| Resolution (Å) | 28.3–1.90 |

| Total Number of measure Reflections | 14599 |

| Rsymb (%) | 13.0 (50.2) |

| I/Iσ | 9.95 (2.60) |

| Completeness (%) | 96.5 (94.8) |

| Redundancy | 3.2 (3.1) |

| Rcrystc (%) | 18.7 (22.0) |

| Rfreed (%) | 24.6 (32.3) |

| Num. of Prot. Atoms | 1557 |

| Num. of Water Molecules | 169 |

| Num. of SQV Atoms | 49 |

| r.m.s.d.: Bond Lengths (Å), angles (deg) | 0.008, 1.159 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%): Most favored, Allowed, Outliers | 95, 5, 0 |

| Avg. B factors (Å2): Main-chain, Side-chain, Solvent, SQV. | 16.9, 21.2, 29.0, 19.1 |

Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shell.

Rsym = (Σ|I – ⟨I⟩|/Σ⟨I⟩) × 100.

Rcryst = (Σ|Fo – Fc|/Σ|Fo|) × 100.

Rfree is calculated in the same way as Rcryst except it is for data omitted from refinement (5% of reflections for all data sets).

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

The initial coordinates and sequence for PRWT-SQV and PRG48T/L89M-SQV were obtained from the X-ray crystal structures PDB ID code 1HXB(25) and PDB ID code 4QGI, respectively. The missing atoms from the X-ray structures were added using the LEaP module in AmberTools13. The AMBER ff12SB39 force field was used for the protein, and the parameters for saquinavir were generated using the antechamber module and GAFF40 force field with AM1-BCC41 charges. Only one of the catalytic aspartates was protonated.

The explicit solvent was modeled using a 15 Å TIP3P42 solvent buffer encapsulating the protein in a truncated octahedron box and chloride ions were added to force neutrality. The long-range electrostatics were treated with the particle-mesh Ewald method (PME),43 using direct space and a van der Waals cutoff of 9 Å. The temperature was maintained at 310 K using Langevin Dynamics with a collision frequency of 1.0 ps–1. The SHAKE44 algorithm was employed so that a 2 fs time step could be utilized. An equilibration procedure was invoked prior to performing the MD simulations. First, the hydrogen atoms were minimized followed by the entire system. Each minimization process consisted of 500 steps of steepest descent followed by 10 000 steps of conjugate gradient. The systems were heated, at constant volume, linearly from 100 to 310 K over a 1 ns MD simulation, where a 5 kcal/mol·Å2 positional restraint was placed on the solute. Following heating, the density was equilibrated for 500 ps at constant pressure and temperature, with a 2 ps–1 coupling constant for the Berendsen barostat. Next, five simulations were performed where the positional restraint was reduced from 5 to 0.1 kcal/mol·Å2. In the last step of equilibration, all restraints were removed and 5 ns of unrestrained MD was performed.

The production phase consisted of running 20 × 51 ns simulations, but only the last 50 ns were used for analysis. Snapshots of the MD trajectory were saved every 30 ps. Analyses of the trajectories were performed using the cpptraj(45) module of AmberTools13 and VMD.46 All MD simulations were performed using pmemd.cuda(47) in AMBER 12.48

Results

Effect of Gly48Thr/Leu89Met on Substrate and Inhibitor Binding

Nine FDA approved clinical PR inhibitors were evaluated for their binding potency for PRWT and PRG48T/L89M (Table 2). IDV exhibited the greatest loss of binding potency for PRG48T/L89M with a 41-fold increase in Ki relative to PRWT, followed by SQV (18-fold) (Figure 2), APV (15-fold), and NFV (9-fold). Assessment of the steady-state binding kinetics and catalytic turnover of the chromogenic decapeptide substrate, Lys-Ala-Arg-Val-Leu*Nph-Glu-Ala-NLe-Gly,10,49 reveals that the Gly48Thr/Leu89Met mutations and the natural polymorphism, Val3Ile, do not affect the kinetic parameters Km, kcat, or the overall catalytic efficiency of the enzyme, kcat/Km, compared to PRWT (Table 3).

Table 2. Ki Values for FDA Approved Protease Inhibitors with HIV-1 Subtype B (PRWT) and PRG48T/L89Ma.

| inhibitor | PRWT | PRG48T/L89M | fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDV | 0.9 (0.01) | 37 (4.3) | 41 |

| SQV | 6.9 (0.13) | 125 (15) | 18 |

| APV | 0.17 (0.01) | 2.5 (0.9) | 15 |

| NFV | 1.2 (0.2) | 11 (1.4) | 9 |

| LPV | 0.6 (0.13) | 1.9 (0.3) | 4 |

| RTV | 0.7 (0.1) | 2.1 (0.3) | 3 |

| ATZ | 0.48 (0.06) | 1.3 (0.08) | 3 |

| DRV | 0.12 (0.03) | 0.29 (0.09) | 2.4 |

| TPV | 0.23 (0.04) | 0.23 (0.03) | 1 |

The data are the average of three independent experiments.

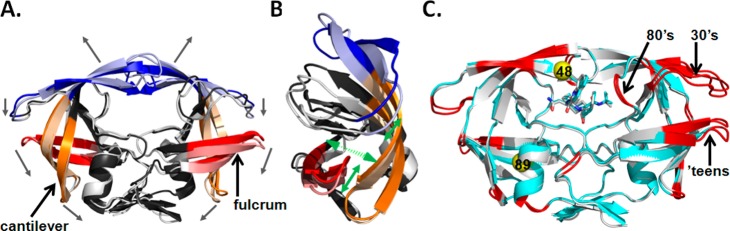

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of the FDA approved protease inhibitor, saquinavir.

Table 3. Steady-State Kinetic Parameters for HIV-1 Subtype B (PRWT) and PRG48T/L89Ma.

| Michaelis–Menten constants | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| subtype mutant | Km (μM) | kcat (s–1) | kcat/Km (s–1/μM–1) |

| B-PRWT | 17 ± 3.9 | 3.8 ± 0.08 | 0.2 ± 0.02 |

| B-PRG48T/L89M | 14 ± 1.6 | 3.0 ± 0.72 | 0.2 ± 0.07 |

The data are the average of three independent experiments.

Crystal Structure

The crystal structure of PRG48T/L89M complexed with SQV has been determined to a resolution of 1.9 Å (PDB ID code 4QGI) (Figure 1C). The crystallographic statistics are summarized in Table 1. The PRG48T/L89M-SQV structure was determined in the space group P212121 and compared to the previously determined structure of PR bound with SQV (resolution: 2.3 Å; space group P61; PDB code 1HXB) (PRWT-SQV).25 The only differences in the amino acid sequences of PRG48T/L89M-SQV compared to PRWT-SQV are that the former contains the natural polymorphism Val3Ile in addition to the mutations. Neither structure contains stabilizing mutations Gln7Lys, Leu33Ile, or Leu63Ile. Comparison of the active site volumes of PRG48T/L89M-SQV (1250 Å3) and PRWT-SQV (1100 Å3) indicates that the active site of PRG48T/L89M-SQV has increased 13% relative to PRWT-SQV. Glu35 and Arg8 are the only residues that show partial occupancy in PRG48T/L89M-SQV.

Structural Effects of Gly48Thr/Leu89Met Mutations

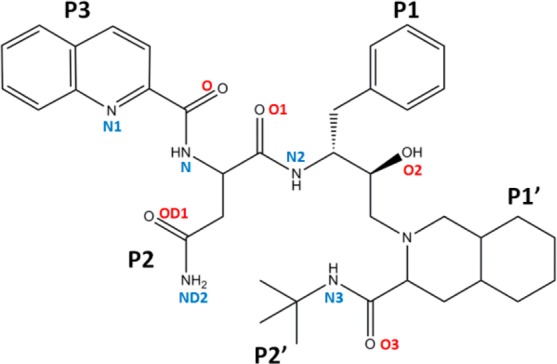

Analysis of the conformational differences in the two structures reveals considerable changes in the ‘teens (fulcrum) and 30’s strands (Figure 1C). This is signified by the downward displacement of the fulcrum and elbows in both monomers, although the displacement is asymmetric. In monomer A, the main chain is shifted approximately 1.6 and 1.9 Å in the ‘teens and 30’s strands, respectively. This is reversed in monomer B where there is a greater displacement in the ‘teens strand (2.5 Å) and smaller displacement in the 30’s strand (1.7 Å). In monomer A of PRG48T/L89M-SQV, the downward displacement of the elbow composed of residues 16–19 is a result of the approximate 180° repositioning of Gln18 (Figure 3A). This results in the loss of a 3.0 Å hydrogen bond between Nε-H of Gln18 and O of Ser37, as well as the loss of a 3.5 Å hydrogen bond between the O of Gly16 and the Nε-H of Gln18. Additionally, due to a 1.0 Å movement of the side chain of Leu38, the upper elbow composed of residues 35–40 is displaced downward as a result of the acquisition of new vdw interactions between the side chain of Leu38 and neighboring residues, Tyr59 and Ile15, in PRG48T/L89M-SQV. The approximate 1.75 Å downward displacement of the 30’s strand in monomer B is a result of the loss of three vdw contacts between Ile13′ and Ile15′ with Leu33′ (Figure 5A,B). Although one contact is retained between Ile15′ and Leu33′ in PRG48T/L89M-SQV, the net loss of two vdw contacts between Ile13′/15′ and Leu33′ results in a destabilized 30’s and ‘teens strands. Additionally, the repositioned elbow is stabilized by a new hydrogen bonding interaction between the carbonyl oxygen of Ser37′ and the Nε-H of Gln18′ (3.0 Å) (Figure 3B). The displaced 30’s strand is further stabilized by a new hydrogen bond between the Oε of Gln18′ and the Nζ-H of Lys20′ (3.0 Å). Interestingly, mutations at both Lys2023,50,51 and Leu3313,17,20,50,52,53 are associated with PI resistance.

Figure 3.

(A) Superposition of PRG48T/L89M-SQV (cyan) with PRWT-SQV (1HXB) (silver). In monomer A of PRG48T/L89M-SQV, hydrogen bonds between Gln18 and Gly16, as well as between Gln18 and Ser37 are lost resulting in approximately 1.5 and 2 Å displacement of the ‘teens and 30’s strand, respectively. The displaced regions are stabilized by new vdw interactions between Leu38, Ile15, and Tyr59. Hydrogen bonds are indicated as dashed lines (black). Vdw interactions are shown as dashed lines for PRG48T/L89M-SQV (red) and PRWT-SQV (gray). (B) Superposition of PRG48T/L89M-SQV (cyan) with PRWT-SQV (silver). Monomer B of PRG48T/L89M-SQV exhibits a greater displacement in the ‘teens region (2.5 Å) and smaller displacement in the 30’s strand (1.25 Å) compared to monomer A. Black dashes indicate hydrogen bonds. In PRG48T/L89M-SQV, there is a new hydrogen bonding interaction between the carbonyl oxygen of Ser37′ and the Nε of Gln18′. The displaced 30’s strand is further stabilized by a new hydrogen bonding interaction between Oε of Gln18′ and the Nζ of Lys20′.

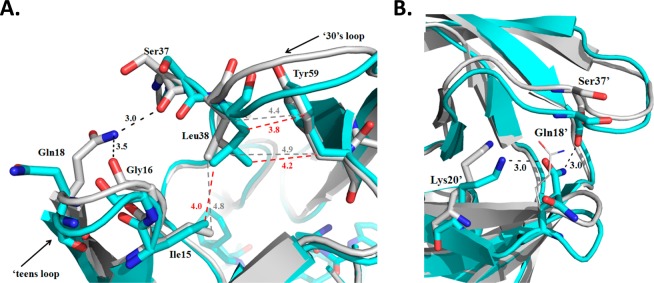

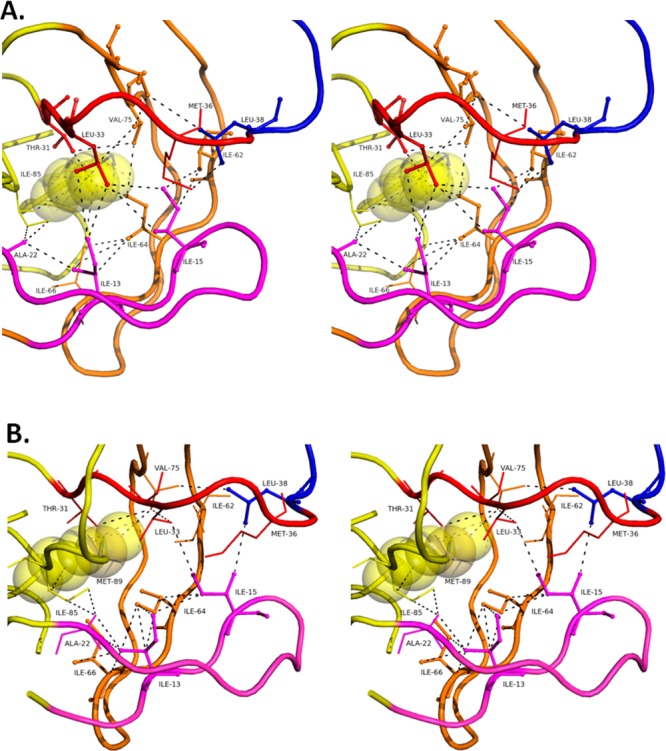

Figure 5.

Stereo images of hydrophobic core residues in monomer B of (A) PRWT-SQV and (B) PRG48T/L89M-SQV. PR is color coded to represent the fulcrum (magenta: 11–22), cantilever (orange: 58–78), elbow flap (blue: 39–57), and 30’s strand (red). Vdw interactions are shown as black dashed lines. In PRWT-SQV, vdw interactions are amenable for hydrophobic sliding; however, in PRG48T/L89M-SQV a redistribution of vdw forces results in altered strand interactions and modified hydrophobic sliding.

Dimerization Regions

The two subunits of PR form a dimer interface composed of the catalytic aspartates, the two flaps, and interdomain interactions involving Arg8, Asp29, Arg87, and the four N- and C- termini.54 The dimerization region called the terminal domain is composed of an extended antiparallel β-sheet formed by the interdigitation of N-terminal (residues 1–4) and C-terminal (residues 96–99) β-strands of each monomer. The interaction between the four termini accounts for close to 75% of the stabilizing force in the dimer.55 Inspection of this region (Supporting Information Figure S1) reveals rotations of the side chains of Gln2 and Asn98′ in PRG48T/L89M-SQV that results in an angle suitable for a new hydrogen bond (2.9 Å) between the Oε of Gln2 and the δN–H of Asn98′. As for Gln2′, its 45° rotation in PRG48T/L89M-SQV results in a new hydrogen bond (3.2 Å) between the Oε of Gln2′ and the Oγ-H of Thr96. Also, PRG48T/L89M-SQV contains the natural polymorphism, Val3Ile. Although several intradomain vdw contacts are gained due to the longer Ile3 side chain in the mutant (Cδ of Ile3 and Cδ of Leu24; Cδ of Ile3′ and Pro1′, Val11′, and Leu24′), only three interdomain vdw contacts are gained (Ile3-Phe99′, 4 Å; Ile3′-Phe99, 4 Å). In summation of the interactions in the terminal domain, two new interdomain hydrogen bonds and three new vdw contacts are gained in this region of the dimerization domain in PRG48T/L89M-SQV, thus contributing to a more stable dimer relative to PRWT-SQV.

Examination of other contacts important for dimerization reveals an 86° rotation of the side chain of Arg8 in PRG48T/L89M-SQV resulting in two new hydrogen bonds between Arg8 and Asp29′. The same acquisition of two hydrogen bonds between the two dimers is observed between Arg8′ and Asp29 in PRG48T/L89M-SQV, due to a 117° rotation of Arg8′. The interdomain hydrogen bonding interactions between Arg87 and the carbonyl oxygen of Leu5 are conserved from PRWT-SQV to PRG48T/L89M-SQV. Like the terminal region of the dimerization domain, additional hydrogen bonding interactions are detected in this region of PRG48T/L89M-SQV indicating increased dimer stability.

Each subunit of the active PR homodimer has a glycine-rich region called the “flap” composed of residues Lys45-Met-Ile-Gly-Gly-Ile-Gly-Gly-Phe-Ile-Lys55 which holds two antiparallel β-strands. The flexible flaps play an important role in the binding of a substrate or an inhibitor in the active site of the PR.9,56,57 Mutagenesis studies have characterized the importance of residues in the flap for ligand binding in the active site.58,59 The residues Met46, Phe53, and Lys55 are the most tolerant of substitutions; Ile47, Ile50, Ile54, and Val56 tolerate a few conservative substitutions only; and Gly48, Gly49, Gly51, and Gly52 are the most sensitive to mutations. Mutations in flap residues 46, 47, 48, 50, 53, and 54 are often observed in drug-resistant mutants of HIV and show various levels of reduced drug susceptibility to different PR inhibitors.27,60

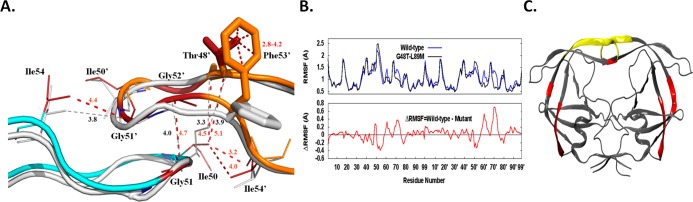

Analysis of both structures reveals that there are some significant changes in the interatomic distances between flaps (Figure 4A). The flap of monomer B is repositioned and is stabilized by new vdw interactions between Phe53′ and Thre48′. Also, there is an increase in distance between the side chains of Ile54 and Gly51′ in PRG48T/L89M-SQV (4.4 Å) compared to PRWT-SQV (3.8 Å) resulting in the former in a loss of a vdw interaction between the flaps of monomer A and B. Additionally, PRG48T/L89M-SQV exhibits an increase in distance between Gly51 and Gly52′ from 4.0 to 4.7 Å, resulting in the loss of a vdw contact between these residues. Another two vdw contacts are lost in PRG48T/L89M-SQV between Ile50 and Thr48′ where the distance between these residues has changed from 3.3 and 3.9 Å in PRWT-SQV to 4.5 and 5.1 Å, respectively, in PRG48T/L89M-SQV. It should be noted that two vdw contacts are gained in PRG48T/L89M-SQV between Ile54′ and Ile50. However, in three tandem locations within the flaps of PRG48T/L89M-SQV vdw contacts are lost. The overall consequence of the Gly48Thr/Leu89Met mutations is a loss of vdw interactions that results in weaker interatomic flap interactions. This favors a more open flap conformation. In support of this, our molecular dynamics simulations also indicate that the flaps of PRG48T/L89M-SQV are more flexible than PRWT-SQV (Figure 4B and C) and assume a more open conformation compared to PRWT-SQV (Supporting Information Figure S2).

Figure 4.

(A) Superposition of the “flap” region of PRG48T/L89M-SQV (cyan/orange) and PRWT-SQV (silver). Monomer A is indicated by cyan/silver and Monomer B colored in orange/silver. PRG48T/L89M-SQV residues are rendered as dark red sticks and PRWT-SQV as silver sticks. Vdw interactions and distances are shown in red for PRG48T/L89M-SQV and gray for PRWT-SQV. Repositioning of the flap of monomer B of PRG48T/L89M-SQV is stabilized by new vdw interactions between Phe53′ and Thre48′. There is an increase in distance between the side chains of Ile54 and Gly51′ in PRG48T/L89M-SQV compared to PRWT-SQV resulting in a loss of a vdw interaction between the flaps of monomer A and B in PRG48T/L89M-SQV. Vdw contacts are also lost between Gly51 and Gly52′ and between between Ile50 and Thre48′ in PRG48T/L89M-SQV. (B) The root mean squared fluctuations of the Cα atoms of PRWT-SQV and PRG48T/L89M-SQV. The average structure of the ensemble was used as the reference. The differences between the RMSF values of the PRWT-SQV and PRG48T/L89M-SQV were calculated. A positive number indicates that a particular residue of PRWT-SQV fluctuates more than PRG48T/L89M-SQV and vice versa. (C) ΔRMSF values in (B) mapped onto PR illustrating where the largest differences between PRWT-SQV and PRG48T/L89M-SQV occur. (Red signifies residues that are less flexible in PRG48T/L89M-SQV compared to PRWT-SQV. Yellow signifies residues that are more flexible in the PRG48T/L89M-SQV relative to PRWT-SQV.

Effect of Substitution Leu89Met on the Hydrophobic Core

The “hydrophobic sliding” mechanism proposes that one surface of PR slides across another surface via the exchange of vdw contacts between hydrophobic side chains.11,12 Specifically, molecular dynamics simulations by Foulkes-Murzycki et al. show the importance of Ile15 (monomer A) or Ile13 (monomer B) in the fulcrum “horizontally” sliding over Leu33 and Leu38 in the 30’s strand (Figure 5A). Simultaneously, the cantilever slides downward, “vertically”, as Ile15 exchanges contacts from Ile64/Val75 to Ile62/Val77 in the cantilever. Since the sliding strands are attached to either end of the flap region, as the ‘teens and 30’s strands slide horizontally and the cantilever slides vertically, they facilitate the movement of the flap region. In monomer B, contacts made by Ile15 with the cantilever are split between Ile13 and Ile15. Ile13 gains the contacts lost by Ile15 with Val75 as the cantilever moves downward while Ile15 maintains contact with Ile62 and Ile6411 in order to facilitate flap opening in this monomer (Figure 5A). It should be noted that these simulations were done with unliganded PR, so a direct comparison with PRWT-SQV and PRG48T/L89M-SQV is not possible. However, when exploring the vdw interactions involving these residues in PRWT-SQV and PRG48T/L89M-SQV we do uncover interesting similarities and differences that provide illuminating insights on the sliding mechanism of these constructs.

For example, the Leu89Met mutation is at 1 of the 19 amino acid positions that comprises the hydrophobic core of the protease. Alterations in the arrangement of vdw interactions are observed between PRWT-SQV and PRG48T/L89M-SQV, and we speculate that this may interfere with the hydrophobic sliding mechanism resulting in the inability of PRG48T/L89M-SQV to achieve a fully closed conformation. Consequently, this would provide an explanation for the weaker inhibitor binding observed with several of the FDA approved inhibitors tested with PRG48T/L89M.

At first glance there are noticeable differences between the 19 hydrophobic core residues in monomer A compared to monomer B of PRG48T/L89M-SQV. In monomer B, 7 (Ile15′, Leu33′, Met36′, Leu38′, Ile64′, Val75′, and Met89′) of the 19 residues have side chains that are rotated >45° compared to PRWT-SQV. In stark contrast, in monomer A, only 1 (Ile64) of the 19 residues of the hydrophobic core has rotated 33°. The Leu89Met substitution in monomer B appears to have perturbed the hydrophobic sliding mechanism as a result of two effects. First, there is a loss of important vdw interactions in PRG48T/L89M-SQV compared to PRWT-SQV. These interactions in PRWT-SQV appear requisite for optimal strand sliding between the fulcrum and the cantilever. Second, there is the formation of new interactions between alternate strands of the sliding mechanism in PRG48T/L89M-SQV. Our molecular dynamics simulations indicate increased rigidity in the cantilever and a more flexible flap region, in agreement with our crystallographic data showing an expanded active site and a defective sliding mechanism (Figure 4B,C). This will be discussed in the context of the vdw forces between the fulcrum (‘teens and 20’s strand; colored magenta) and 30’s strand (colored red), cantilever (colored orange), and flap elbows (colored blue) (Figure 5A and B).

Hydrophobic Sliding in PRWT-SQV: Monomer B

In monomer B of PRWT-SQV, Leu89′ makes a vdw contact with Thre31′ in the 30’s strand which then makes a vdw contact with Val75′ in the cantilever (Figure 5A). From Val75′ in the cantilever, a series of consecutive vdw forces link it to neighboring cantilever residues Ile64′ and Ile66′, thereby completing the circuit of vdw interactions since both Ile64′ and Ile66′ interact with Leu89′. This route links Leu89′ to the 30’s strand and to the cantilever. Interestingly, at Ile64′, two alternative routes of vdw forces lead back to Leu89′ linking the fulcrum to the rest of the mechanism. One route is achieved by Ile64′ making a vdw interaction with Ile13′ which then makes a vdw contact with Ala22′. Ala22′ then makes two vdw contacts with Ile85′. Then Ile85′ makes a vdw contact back with Leu89′. The other route involves Ile64′ interacting with Ile66′ before interacting with Ile13′. Then this path has a common vdw route back to Leu89′ as the first path described. So, the intersection of Ile64′, Ile13′, and Ile66′ appears critical for the Leu89′ dependent functioning of the sliding mechanism, as it appears to link the fulcrum and cantilever to Leu89′ of PRWT-SQV. Importantly, in PRWT-SQV Ile13′ and Ile15′ both make two vdw interactions with Leu33′ permitting the horizontal sliding of the fulcrum against the 30’s strand as proposed by Foulkes-Murzycki et al.11 Additionally, Ile13′ makes one vdw contact with Ile64′ and one with Ile66′, and Ile15′ makes two vdw contacts with Ile62′, thus providing hydrophobic surfaces for the vertical sliding of the cantilever against the fulcrum in PRWT-SQV. These vdw forces are significantly altered in PRG48T/L89M-SQV and may account for a defective hydrophobic sliding mechanism.

Defective Vertical Hydrophobic Sliding in PRG48T/L89M-SQV: Monomer B

Exploration of the role of Met89′ in monomer B of PRG48T/L89M-SQV (Figure 5B) reveals quite interesting differences compared to PRWT-SQV, described previously. In regard to the vertical sliding of the cantilever against the fulcrum in PRG48T/L89M-SQV, Met89′ owing to its longer side chain bypasses Thr31′ and makes a vdw contact with Val75′ in the cantilever. The linkage of vdw forces in the cantilever from Val75′ to Ile64′, then to Ile66′, and then back to Met89′ is notably different in PRG48T/L89M-SQV compared to PRWT-SQV. In PRG48T/L89M-SQV, Val75′ does not make a vdw contact with Ile64′ (5.8 Å). This represents a short circuit in the vdw contacts linking Val75′ and Ile64′ in the cantilever back to Met89′. The loss of the Val75′-Ile64′ vdw contact decreases the hydrophobic surface area in the cantilever available for vertical sliding against the fulcrum, which likely contributes to a defective hydrophobic sliding mechanism.

Defective Horizontal Hydrophobic Sliding in PRG48T/L89M-SQV: Monomer B

From observations of residues important for the horizontal hydrophobic sliding of the fulcrum against the 30’s strand in PRWT-SQV, Leu33′ makes two vdw interactions with both Ile13′ (4.2 Å, 3.8 Å) and Ile15′ (4.4 Å) facilitating the 30’s strand to slide over the ‘teens strand. However, this is not the case in PRG48T/L89M-SQV where Leu33′ has lost all vdw contacts with Ile13′ (4.8 Å) and only has one remaining vdw contact with Ile15′ (3.8 Å). Consequently, the horizontally sliding of the fulcrum over the 30’s strand may be impaired in PRG48T/L89M-SQV, thus preventing complete flap closure. Instead, in PRG48T/L89M-SQV Ile13′ and Ile15′ make nine vdw contacts between Ile64′ and Ile66′ which are located in the cantilever. In other words, PRG48T/L89M-SQV has lost important vdw interactions that facilitate the horizontal hydrophobic sliding of the fulcrum and 30’s strand and has acquired many new vdw forces linking the ‘teens strand of the fulcrum to the cantilever. This is very different than observed in PRWT-SQV. The increased number of vdw forces between the fulcrum and the cantilever (3 vdw contacts in PRWT-SQV vs 9 vdw contacts in PRG48T/L89M-SQV) may result in the inability of the cantilever to slide properly, thus preventing complete flap closure. This is supported by molecular dynamics simulations that indicate that the cantilever of PRG48T/L89M-SQV is more rigid compared to PRWT-SQV (Figure 4B,C). As for the elbow flaps, in PRWT-SQV a vdw interaction between Leu38′ in the elbow flap and Met36′ is lost (6.2 Å) in PRG48T/L89M-SQV. Also, there is a new vdw intereaction between Leu38′ and Val75′ (3.5 Å) in the cantilever that is not present in PRWT-SQV. These alterations in vdw interactions likely play a role in the repositioning of the elbow flap downward, thus favoring a more open conformation of PRG48T/L89M-SQV.

Hydrophobic Sliding in Monomer A: PRWT-SQV

In monomer A of PRWT-SQV, similar interactions important for the hydrophobic sliding of the cantilever and fulcrum are observed (Supporting Information Figure S3A). Importantly, Leu89 is still integrally linked by vdw forces to Thr31 and to Val75 and Val77 in the cantilever and then linked to Leu38 in the elbow flap. Also, monomer A exhibits the same two alternative routes of vdw forces that lead back to Leu89 that link the fulcrum to the rest of the mechanism, as previously discussed. Also like monomer B, Ile13 and Ile15 make vdw interactions with Leu33 that may facilitate the horizontal sliding of the fulcrum. Additionally, Ile13 and Ile15 make vdw contacts with Ile64/Ile66 and Ile62, respectively, allowing for the vertical sliding of the cantilever against the fulcrum. Additionally, the vdw interaction between Leu38 and Met36 that connects the elbow flap to the thirties strand is preserved in monomer A of PRWT-SQV.

Modified Hydrophobic Sliding in Monomer A: PRG48T/L89M-SQV

The effect of the Leu89Met substitution on hydrophobic sliding is less noticeable in monomer A which is consistent with its less severe structural perturbations (Supporting Information Figure S3B). Like PRWT-SQV, Met89 interacts with Val75; however, it bypasses Thr31, like in monomer B of PRG48T/L89M-SQV. Val75 then makes a vdw contact with Val77 which interacts with Leu38 to connect the elbow flap to the cantilever. It appears that the horizontal hydrophobic sliding mechanism in monomer A of PRG48T/L89M-SQV is similar to that of monomer A of PRWT-SQV, since vdw contacts between Leu33 and Ile13/Ile15 are conserved between the two structures. However, the vertical sliding of the cantilever against the fulcrum appears modified since two vdw contacts between Ile13 and Ile66, and one vdw contact between Ile13 and Ile64 are lost. Another difference in PRG48T/L89M-SQV, is that one of the two alternative routes of vdw forces that lead back to Leu89 that link the fulcrum to the rest of the mechanism is missing due to the lost vdw interaction between Ile13 and Ile66.

Superposition of the crystal structures for PRG48T/L89M-SQV and PRWT-SQV shows the consequences of the defective sliding mechanism of PRG48T/L89M-SQV (Figure 1C). PRG48T/L89M-SQV exhibits a downward displaced fulcrum relative to the more ”closed” form of PRWT-SQV. Also, in PRG48T/L89M-SQV, active site expansion is apparent in the 80’s loop relative to PRWT-SQV. This is supported by molecular dynamics simulations showing increased mobility of SQV in the active site of PRG48T/L89M-SQV relative to PRWT-SQV. (Supporting Information Figure S4).

PR Interactions with Saquinavir

Saquinavir is a peptidomimetic inhibitor containing the main chain amides and carbonyl oxygen atoms of a peptide and a number of groups corresponding to the side chains at positions P3–P2′ of a peptide substrate (Figure 2).61 The large hydrophobic groups at positions P3, P1, and P1′ of SQV occupy the hydrophobic pockets S3, S1, and S1′ formed by PR. In the P2′ position, there is a smaller t-butyl group and the polar side chain of asparagine at P2 of SQV.

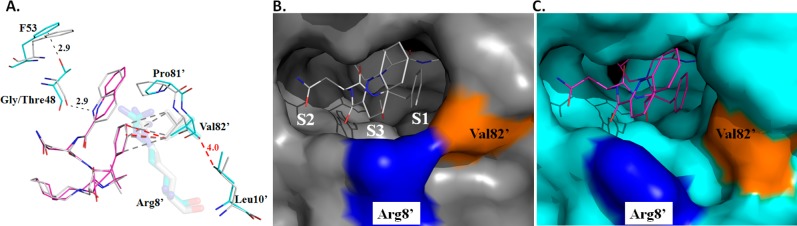

Four potential hydrogen bonds are formed between the hydroxyl group of SQV and the side chain carboxylate oxygen atoms of the catalytic Asp25/25′ (Supporting Information Figure S5). Additionally, hydrogen bonds are formed from the N2 of SQV to the main chain carbonyl of Gly27, amide nitrogen of Asp29 to O of SQV, from the amide nitrogen of Asp30 to OD1 of SQV, from ND2 of SQV to Oγ of Asp30, N of SQV to the main chain carbonyl of Gly48, and N1 of SQV to the main chain carbonyl of Gly48. The conserved water linking the PR flaps and SQV are present between the amide nitrogens of Ile50/50′ and O1 and O3 of SQV are present. In the PRG48T/L89M-SQV complex, the hydrogen bond from the carbonyl of Gly48 to N1–H of the quinolone ring is missing and accounts for the torqueing of the quinolone ring system (Figure 6A and Supporting Information Figure S5). Also, the solvent-mediated interaction between ND2 of SQV and N1–H of SQV is not present in the PRG48T/L89M-SQV complex. In addition, a new solvent-mediated interaction is observed in the PRG48T/L89M-SQV complex between the amide N of Asp29′ and N3 of SQV.

Figure 6.

(A) PRWT-SQV is shown in silver and PRG48T/L89M-SQV is shown in cyan and magenta. In PRG48T/L89M-SQV, the side chain of Val82′ is relocated 156° away from the P1 Phe of saquinavir and the guinidinium group of Arg8′ is rotated 117° away from the active site. The repositioning of Val82′ and Arg8′ results in the opening of the base of the S1/S3 subsite in the PRG48T/L89M-SQV structure and results in the loss of three vdw contacts between the P1 Phe of SQV and S1 of PRG48T/L89M-SQV. In the S3 subsite, introduction of the threonine side chain at position 48 creates new 2.9 Å noncononical O–H---π interactions between the Thr48 OH and the C3 and C4 of Phe53 resulting in the loss of a hydrogen bond between N1 of SQV and the main chain carbonyl of Gly48. Only one O–H---π interaction is shown for clarity. (B) Surface representation of PRWT-SQV (gray). Arg8′ is colored blue andVal82′ is colored orange. (C) Surface representation of PRG48T/L89M-SQV.

S1/S3 Subsite

The S1/S3 subsites are next to each other in the active site of the protease. In PRWT-SQV, Pro81′, Val82′, Arg8′, and Asp29 form the mouth of the cavity. However, in PRG48T/L89M-SQV the side chain of Val82′ is relocated 156° away from the P1 Phe of SQV and the guinidinium group of Arg8′ is rotated 117° away from the active site. As a result, a new vdw interaction between the side chain of Val82′ and the side chain of Leu10′ (4.0 Å) is gained which stabilizes the repositioned side chain of Val82′. The repositioning of Val82′ results in the opening of the base of the S1/S3 subsite in the PRG48T/L89M-SQV structure (Figure 6 A,B,C). In the PRWT-SQV structure, the Cγ1 and Cγ2 of Val82′ make five vdw contacts with the P1 Phe of SQV. However, in the PRG48T/L89M-SQV structure the Cγ1 of Val82′ makes only two vdw contacts with the P1 Phe, thus resulting in the loss of three vdw contacts between the P1 Phe of SQV and S1 of PRG48T/L89M-SQV. This contributes to the weaker binding of SQV observed with PRG48T/L89M-SQV and importantly an enlarged active site.

The S3 subsite is directly impacted by the Gly48Thr substitution in monomer A. Introduction of the threonine side chain at position 48 creates new 2.9 Å noncanonical O–H---π interactions between the Thr48 OH and the C3 and C4 of Phe53 (Figure 6A).62 This results in the repositioning of the main chain carbonyl of Thr48 away from the N1 of SQV. As a result, a 2.9 Å hydrogen bond between N1–H of SQV and the main chain carbonyl of Gly48 is lost, resulting in the torqueing of the quinolone ring of 19° toward Pro81′.

S1′/S2′ and S2 Subsites

Only subtle changes in the hydrophobic packing of the DIQ ring system is observed in the S1′ subsite. In the S2′ pocket, one vdw interaction between the tert-butyl of SQV and Ala28′ is lost (4.1 Å vs 4.9 Å) in PRG48T/L89M-SQV which may account for its 33° rotation (data not shown) and further enlargement of the active site. Our molecular dynamics simulations indicate that saquinavir is more mobile in the active site of PRG48T/L89M-SQV (Supporting Information Figure S4) compared to PRWT-SQV and that SQV makes less favorable vdw interactions with the active site residues Ile50, Phe53, Val82, Ile84, and Ala28′ of PRG48T/L89M-SQV compared to PRWT-SQV (Supporting Information Figure S6). These data agree with our crystallographic observations of an expanded active site that results in the loss of important interactions between SQV and the S1, S3, and S2′ subsites of PRG48T/L89M-SQV.

The P2 Asn exhibits more favorable interactions with PRG48T/L89M-SQV compared to its binding motif in PRWT-SQV. Ala28 and Ile84 make stronger vdw interactions with the Cβ of the P2 Asn compared to PRWT-SQV. Additionally, the hydrogen bond between Asp30 and ND2 of the P2 Asn is stronger in PRG48T/L89M-SQV (3.0 Å) compared to PRWT-SQV (3.8 Å). These effects are primarily due to the rotation of the side chain of Ile84 and slight displacement of the side chain of Asp30.

Discussion

We have described the structural analysis of a previously uncharacterized drug resistant variant PRG48T/L89M in complex with SQV. A detailed analysis of the X-ray crystal structure in addition to molecular dynamics simulations provides explanations for how the mutations Gly48Thr and Leu89Met confer SQV resistance. The most obvious explanations for PR drug resistance are derived from the analysis of primary mutations, defined as mutations of residues that comprise the ligand binding site.

The S3 subsite is directly influenced by the Gly48Thr substitution that results in the loss of a hydrogen bond between N1–H of the quinolone of SQV and the main chain carbonyl of Gly48. It is not difficult to conceive that PRG48T/L89M exhibits decreased susceptibility to SQV given that HIV-1 PR mutants containing Gly48Val or Gly48Val/Leu90Met demonstrate 13.5- and 419-fold reductions of susceptibility to SQV, respectively.63 In Gly48Val, loss of SQV binding is attributed to the loss of a hydrogen bond between the carbonyl oxygen of 48 and the amide of SQV.64 Interestingly, we observe a similar effect in PRG48T/L89M-SQV.

Examination of the S1 pocket of PRWT-SQV indicates that there is a high degree of packing between the vdw surfaces of the P1 Phe of SQV and Val82′, and this is consistent with other cocrystal structures of PR-SQV.65 Notably, Val82 is an important residue contributing to inhibitor binding in the active site. Mutation of Val82 individually, or in combination with a secondary mutation, is associated with decreased susceptibility to many PIs, including IDV, LPV, ATV, NFV, TPV, and FPV.13−22,66−68 Previous work by Prabu-Jeyabalan et al.65 shows that resistance to SQV is partially a result of the loss of vdw contacts between Val82′ and P1 Phe of SQV. Although in this study of PRG48T/L89M-SQV Val82 has not been substituted with the shorter alanine, its side chain has rotated 156°, effectively resulting in the loss of three vdw interactions with P1 Phe of SQV. These data are consistent with the findings of Prabu-Jeyabalan et al. that indicate the critical importance of vdw contacts between the P1 Phe of SQV and Val82′ for effective inhibitor binding. In the S2′ subsite of PRG48T/L89M-SQV, the P2′ tert-butyl group is less tightly packed in the binding pocket of PRG48T/L89M-SQV, as indicated by the loss of one vdw contact. It appears that the 13% increase in active site volume calculated by CastP36 most likely reflects the expansion of subsites S1, S3, and S2′, since it is in these cavities that losses of vdw contacts and a H-bond between SQV and PR are observed in PRG48T/L89M-SQV.

Less intuitive is how the secondary mutation, Leu89Met, confers inhibitor resistance. Diverse and subtle structural changes have been observed for PR variants with resistance mutations that alter residues outside the active site cavity. Mutations in flap and other regions including the hydrophobic core are included in this category.66 The Leu89Met mutation is located within the hydrophobic core of PR and plays an important role in the hydrophobic sliding mechanism.11 Our data indicate that the loss and redistribution of vdw forces resulting from the Leu89Met substitution, relative to PRWT-SQV, perturbs the hydrophobic sliding mechanism resulting in the inability of PRG48T/L89M-SQV to fully attain a closed conformation. This is supported by our crystallographic data showing the downward displacement of the fulcrum and elbow flaps, an expanded active site, and weaker interdomain flap interactions. In addition, our molecular dynamics simulations that indicate increased flexibility in the flap region, increased rigidity in the cantilever, and increased mobility of SQV in the active site are in agreement with the crystallographic data. Since PIs are designed to bind optimally to the closed conformation of PR, this results in decreased susceptibility to several PIs.

Curiously, PRG48T/L89M-SQV exhibits increases in stabilizing interactions in various regions of the dimerization domain. However, the variant still exhibits decreased susceptibility to a number of PIs. This suggests that even in light of a more stable dimeric PR, PRG48T/L89M still exhibits considerable resistance to several PIs due to its structural anomalies. The simultaneous acquisition of stabilizing interdomain interactions while acquiring PI resistant mutations may represent a mechanism by which PR maintains the ability to process substrate while evading PIs. Future work on the development of allosteric inhibitors that work in conjunction with FDA approved PIs to push the conformational equilibrium of a drug resistance protease to the closed form may provide an alternative approach to addressing the problem of HIV drug resistance.69 Alternatively, another approach to overcome drug resistance may be the design of drugs that bind the open conformation such as compounds like metallacarboranes and pyrrolidine-based inhibitors.70

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- SQV

saquinavir

- APV

amprenavir

- ATZ

atazanavir

- LPV

lopinavir

- DRV

darunavir

- RTV

ritonavir

- TPV

tipranavir

- IDV

indinavir

- NFV

nelfinavir

- FPV

fosamprenavir

- PR

protease

- PRWT

HIV-1 protease without stabilizing mutations

- PRWT-SQV

WT HIV-1 protease without stabilizing mutations bound with saquinavir PDB code 1HXB

- PRG48T/L89M

apo HIV-1 protease Gly48Thr/Leu89Met

- PRG48T/L89M-SQV

HIV-1 protease Gly48Thr/Leu89Met bound with saquinavir

- PI

protease inhibitor

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus type-1

- HAART

highly antiretroviral therapy

- vdw

van der Waal

- DIQ

decahydroisoquinoline

- MD

molecular dynamics

- RMSF

root-mean-square fluctuation

- Sn

subsites of the PR active site

- Pn

Positions of a ligand bound in the active site of PR

- fulcrum

(amino acids 11–22)

- elbows

(amino acids 39–57)

- cantilever

(amino acids 58–78)

Supporting Information Available

Additional structural and molecular dynamic simulation data. These data support that the Gly48Thr and Leu89Met mutations result in a PR with enhanced stability resulting from the acquisition of new interdomain hydrogen bonding interactions. Also, these mutations result in a PR with an expanded active site. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This work was funded by a National Institute of Health grant, R37 A128571, to Ben M. Dunn.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- World Health Organization, UNAIDS (March 2014) Surveilllance of HIV Drug Resistance in Adults Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy (Pretreatment HIV Drug Resistance), http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/drugresistance/pretreatment_drugresistance/en/.

- World Health Organization (2013) Number of deaths due to HIV/AIDS; http://www.who.int/gho/hiv/epidemic_status/deaths_text/en/.

- Tozser J. (2001) HIV Inhibitors: Problems and Reality. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 946, 145–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer S. M.; Squires K. E.; Hughes M. D.; Grimes J. M.; Demeter L. M.; Currier J. S.; Eron J. J. Jr.; Feinberg J. E.; Balfour H. H. Jr.; Deyton L. R.; Chodakewitz J. A.; Fischl M. A. (1997) A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 320 Study Team. N. Engl. J. Med. 337, 725–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condra J. H.; Schleif W. A.; Blahy O. M.; Gabryelski L. J.; Graham D. J.; Quintero J. C.; Rhodes A.; Robbins H. L.; Roth E.; Shivaprakash M. (1995) In vivo emergence of HIV-1 variants resistant to multiple protease inhibitors. Nature 374, 569–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debouck C. (1992) The HIV-1 protease as a therapeutic target for AIDS. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 8, 153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlinger H. G.; Sodroski J. G.; Haseltine W. A. (1989) Role of capsid precursor processing and myristoylation in morphogenesis and infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86, 5781–5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis J. M.; Ishima R.; Torchia D. A.; Weber I. T. (2007) HIV-1 protease: structure, dynamics, and inhibition. Adv. Pharmacol. 55, 261–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodawer A.; Erickson J. W. (1993) Structure-based inhibitors of HIV-1 protease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62, 543–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente J. C.; Hemrajani R.; Blum L. E.; Goodenow M. M.; Dunn B. M. (2003) Secondary mutations M36I and A71V in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease can provide an advantage for the emergence of the primary mutation D30N. Biochemistry 42, 15029–15035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes-Murzycki J. E.; Scott W. R.; Schiffer C. A. (2007) Hydrophobic sliding: a possible mechanism for drug resistance in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease. Structure 15, 225–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal S.; Cai Y.; Nalam M. N.; Bolon D. N.; Schiffer C. A. (2012) Hydrophobic core flexibility modulates enzyme activity in HIV-1 protease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 4163–4168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S. Y.; Gonzales M. J.; Kantor R.; Betts B. J.; Ravela J.; Shafer R. W. (2003) Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase and protease sequence database. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 298–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapiro J. M.; Winters M. A.; Stewart F.; Efron B.; Norris J.; Kozal M. J.; Merigan T. C. (1996) The effect of high-dose saquinavir on viral load and CD4+ T-cell counts in HIV-infected patients. Ann. Int. Med. 124, 1039–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevin A. D.; DeGruttola V.; Nijhuis M.; Schapiro J. M.; Foulkes A. S.; Para M. F.; Boucher C. A. (2000) Methods for investigation of the relationship between drug-susceptibility phenotype and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genotype with applications to AIDS clinical trials group 333. J. Infect. Dis. 182, 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor R.; Fessel W. J.; Zolopa A. R.; Israelski D.; Shulman N.; Montoya J. G.; Harbour M.; Schapiro J. M.; Shafer R. W. (2002) Evolution of primary protease inhibitor resistance mutations during protease inhibitor salvage therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 1086–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S. Y.; Taylor J.; Fessel W. J.; Kaufman D.; Towner W.; Troia P.; Ruane P.; Hellinger J.; Shirvani V.; Zolopa A.; Shafer R. W. (2010) HIV-1 protease mutations and protease inhibitor cross-resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4253–4261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Westen G. J.; Hendriks A.; Wegner J. K.; Ijzerman A. P.; van Vlijmen H. W.; Bender A. (2013) Significantly improved HIV inhibitor efficacy prediction employing proteochemometric models generated from antivirogram data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1002899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente J. C.; Coman R. M.; Thiaville M. M.; Janka L. K.; Jeung J. A.; Nukoolkarn S.; Govindasamy L.; Agbandje-McKenna M.; McKenna R.; Leelamanit W.; Goodenow M. M.; Dunn B. M. (2006) Analysis of HIV-1 CRF_01 A/E protease inhibitor resistance: structural determinants for maintaining sensitivity and developing resistance to atazanavir. Biochemistry 45, 5468–5477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeiren H., Van Craenenbroeck E., Alen P., Bacheler L., Picchio G., Lecocq P., and The Virco Clinical Response Collaborative (2007) Prediction of HIV-1 drug susceptibility phenotype from the viral genotype using linear regression modeling, J. Virol. Methods 145, 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S. Y.; Liu T. F.; Holmes S. P.; Shafer R. W. (2007) HIV-1 subtype B protease and reverse transcriptase amino acid covariation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3, e87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin N. T.; Chappey C.; Petropoulos C. J. (2003) Improving lopinavir genotype algorithm through phenotype correlations: novel mutation patterns and amprenavir cross-resistance. AIDS 17, 955–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahriar R.; Rhee S. Y.; Liu T. F.; Fessel W. J.; Scarsella A.; Towner W.; Holmes S. P.; Zolopa A. R.; Shafer R. W. (2009) Nonpolymorphic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease and reverse transcriptase treatment-selected mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 4869–4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornak V.; Okur A.; Rizzo R. C.; Simmerling C. (2006) HIV-1 protease flaps spontaneously open and reclose in molecular dynamics simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 915–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn A.; Redshaw S.; Ritchie J. C.; Graves B. J.; Hatada M. H. (1991) Novel binding mode of highly potent HIV-proteinase inhibitors incorporating the (R)-hydroxyethylamine isostere. J. Med. Chem. 34, 3340–3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow M. M.; Bloom G.; Rose S. L.; Pomeroy S. M.; O’Brien P. O.; Perez E. E.; Sleasman J. W.; Dunn B. M. (2002) Naturally occurring amino acid polymorphisms in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Gag p7(NC) and the C-cleavage site impact Gag-Pol processing by HIV-1 protease. Virology 292, 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente J. C.; Moose R. E.; Hemrajani R.; Whitford L. R.; Govindasamy L.; Reutzel R.; McKenna R.; Agbandje-McKenna M.; Goodenow M. M.; Dunn B. M. (2004) Comparing the accumulation of active- and nonactive-site mutations in the HIV-1 protease. Biochemistry 43, 12141–12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt D.; Dunn B. M. (2000) Chimeric aspartic proteinases and active site binding. Bioorg. Chem. 28, 374–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. a.; M W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams P. D.; Afonine P. V.; Bunkoczi G.; Chen V. B.; Davis I. W.; Echols N.; Headd J. J.; Hung L. W.; Kapral G. J.; Grosse-Kunstleve R. W.; McCoy A. J.; Moriarty N. W.; Oeffner R.; Read R. J.; Richardson D. C.; Richardson J. S.; Terwilliger T. C.; Zwart P. H. (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debreczeni J. E.; Emsley P. (2012) Handling ligands with Coot. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 68, 425–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P.; Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A.; MacArthur M. W.; Moss D. S.; Thornton J. M. (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. (1976) Acta Crystallogr. A32, 922–923. [Google Scholar]

- Winn M. D.; Ballard C. C.; Cowtan K. D.; Dodson E. J.; Emsley P.; Evans P. R.; Keegan R. M.; Krissinel E. B.; Leslie A. G.; McCoy A.; McNicholas S. J.; Murshudov G. N.; Pannu N. S.; Potterton E. A.; Powell H. R.; Read R. J.; Vagin A.; Wilson K. S. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundas J.; Ouyang Z.; Tseng J.; Binkowski A.; Turpaz Y.; Liang J. (2006) CASTp: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins with structural and topographical mapping of functionally annotated residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W116–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald I. K.; Thornton J. M. (1994) Satisfying hydrogen bonding potential in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 238, 777–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, V. S., LLC.

- Hornak V.; Abel R.; Okur A.; Strockbine B.; Roitberg A.; Simmerling C. (2006) Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins 65, 712–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Wolf R. M.; Caldwell J. W.; Kollman P. A.; Case D. A. (2004) Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1157–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakalian A.; Jack D. B.; Bayly C. I. (2002) Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC model: II. Parameterization and validation. J. Comput. Chem. 23, 1623–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L.; Chandrasekhar J.; Madura J. D.; Impey R. W.; Klein M. L. . (1983) Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926. [Google Scholar]

- Darden T.; York D.; Pedersen L. . (1993) Particle mesh Ewald: An N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089. [Google Scholar]

- Ryckaert J.-P.; Ciccotti G.; Berendsen H. J. C. . (1977) Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23, 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Roe D. R.; Cheatham T. E. (2013) PRTAJ and CPPTRAJ: software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 3084–3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W.; Dalke A.; Schulten K. (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–3827–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce L. C.; Salomon-Ferrer R.; Augusto F. d. O. C.; McCammon J. A.; Walker R. C. (2012) Routine access to millisecond time scale events with accelerated molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 2997–3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case D. A., Darden T. A., Cheatham T. E. I., Simmerling C. L., Wang J., Duke R. E., Luo R., Walker R. C., Zhang W., Merz K. M., Roberts B. P., Wang B., Hayik S., Roitberg A. E., Seabra G., Kolossváry I., Wong K. F., Paesani F., Vanicek J., Wu X., Brozell S. R., Steinbrecher T., Gohlke H., Cai Q., Ye X., Wang J., Hsieh M.-J., Cui G., Roe D. R., Mathews D. H., Seetin M. G., Sagui C., Babin V., Luchko T., Gusarov S., Kovalenko A., and Kollman P. A. (2012) AMBER 12, University of California, San Francisco.

- Dunn B. M.; Gustchina A.; Wlodawer A.; Kay J. (1994) Subsite preferences of retroviral proteinases. Methods Enzymol. 241, 254–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garriga C., Perez-Elias M. J., Delgado R., Ruiz L., Najera R., Pumarola T., Alonso-Socas Mdel M., Garcia-Bujalance S., Menendez-Arias L., and Spanish Group for the Study of Antiretroviral Drug (2007) Mutational patterns and correlated amino acid substitutions in the HIV-1 protease after virological failure to nelfinavir- and lopinavir/ritonavir-based treatments, J. Med. Virol. 79, 1617–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svicher V.; Ceccherini-Silberstein F.; Erba F.; Santoro M.; Gori C.; Bellocchi M. C.; Giannella S.; Trotta M. P.; Monforte A.; Antinori A.; Perno C. F. (2005) Novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease mutations potentially involved in resistance to protease inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 2015–2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaugerre C.; Pavie J.; Palmer P.; Ghosn J.; Blanche S.; Roudiere L.; Dominguez S.; Mortier E.; Molina J. M.; de Truchis P. (2008) Pattern and impact of emerging resistance mutations in treatment experienced patients failing darunavir-containing regimen. AIDS 22, 1809–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterrantino G.; Zaccarelli M.; Colao G.; Baldanti F.; Di Giambenedetto S.; Carli T.; Maggiolo F.; Zazzi M. (2012) Genotypic resistance profiles associated with virological failure to darunavir-containing regimens: a cross-sectional analysis. Infection 40, 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber I. T., and Wang Y. F. (2010) HIV-1 protease: role in viral replication, protein-ligand X-ray crystal structures and inhibitor design. In Aspartic Acid Proteases as Therapeutic Targets (Ghosh A. K., Mannhold R., Kubinyi H., and Folkers G., Eds.) pp 109–137, Vol 45, Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Frutos S.; Rodriguez-Mias R. A.; Madurga S.; Collinet B.; Reboud-Ravaux M.; Ludevid D.; Giralt E. (2007) Disruption of the HIV-1 protease dimer with interface peptides: structural studies using NMR spectroscopy combined with [2-(13)C]-Trp selective labeling. Biopolymers 88, 164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T. D.; Schiffer C. A.; Gonzales M. J.; Taylor J.; Kantor R.; Chou S.; Israelski D.; Zolopa A. R.; Fessel W. J.; Shafer R. W. (2003) Mutation patterns and structural correlates in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease following different protease inhibitor treatments. J. Virol. 77, 4836–4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson V. A.; Brun-Vezinet F.; Clotet B.; Gunthard H. F.; Kuritzkes D. R.; Pillay D.; Schapiro J. M.; Richman D. D. (2008) Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Top HIV Med. 16, 138–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody M. D.; Pettit S. C.; Shao W.; Everitt L.; Loeb D. D.; Hutchison C. A. 3rd; Swanstrom R. (1995) A side chain at position 48 of the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 protease flap provides an additional specificity determinant. Virology 207, 475–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb D. D.; S R.; Everitt L.; Manchester M.; Stamper S. E.; Hutchison C. A. (1989) Complete mutagenesis of the HIV-1 protease. Nature 340, 397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtaka H.; Schon A.; Freire E. (2003) Multidrug resistance to HIV-1 protease inhibition requires cooperative coupling between distal mutations. Biochemistry 42, 13659–13666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tie Y.; Kovalevsky A. Y.; Boross P.; Wang Y. F.; Ghosh A. K.; Tozser J.; Harrison R. W.; Weber I. T. (2007) Atomic resolution crystal structures of HIV-1 protease and mutants V82A and I84V with saquinavir. Proteins 67, 232–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan N.; Vijayalakshmi K. P.; Koga N.; Suresh C. H. (2010) Comparison of aromatic NH···pi, OH···pi, and CH···pi interactions of alanine using MP2, CCSD, and DFT methods. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 2874–2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saen-oon S.; Aruksakunwong O.; Wittayanarakul K.; Sompornpisut P.; Hannongbua S. (2007) Insight into analysis of interactions of saquinavir with HIV-1 protease in comparison between the wild-type and G48V and G48V/L90M mutants based on QM and QM/MM calculations. J. Mol. Graph. Modeling 26, 720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L.; Zhang X. C.; Hartsuck J. A.; Tang J. (2000) Crystal structure of an in vivo HIV-1 protease mutant in complex with saquinavir: insights into the mechanisms of drug resistance. Protein Sci. 9, 1898–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabu-Jeyabalan M.; Nalivaika E. A.; King N. M.; Schiffer C. A. (2003) Viability of a drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease variant: structural insights for better antiviral therapy. J. Virol. 77, 1306–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber I. T.; Agniswamy J. (2009) HIV-1 protease: structural perspectives on drug resistance. Viruses 1, 1110–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klabe R. M.; Bacheler L. T.; Ala P. J.; Erickson-Viitanen S.; Meek J. L. (1998) Resistance to HIV protease inhibitors: a comparison of enzyme inhibition and antiviral potency. Biochemistry 37, 8735–8742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulnik S. V.; Suvorov L. I.; Liu B.; Yu B.; Anderson B.; Mitsuya H.; Erickson J. W. (1995) Kinetic characterization and cross-resistance patterns of HIV-1 protease mutants selected under drug pressure. Biochemistry 34, 9282–9287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perryman A. L.; Zhang Q.; Soutter H. H.; Rosenfeld R.; McRee D. E.; Olson A. J.; Elder J. E.; Stout C. D. (2010) Fragment-based screen against HIV protease. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 75, 257–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozisek M.; Cigler P.; Lepsik M.; Fanfrlik J.; Rezacova P.; Brynda J.; Pokorna J.; Plesek J.; Gruner B.; Grantz Saskova K.; Vaclavikova J.; Kral V.; Konvalinka J. (2008) Inorganic polyhedral metallacarborane inhibitors of HIV protease: a new approach to overcoming antiviral resistance. J. Med. Chem. 51, 4839–4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.